The domestication of cattle began in the 9th millennium BC in Southwest Asia (Scheu et al., Reference Scheu, Powell, Bollongino, Vigne, Tresset, Çakırlar, Benecke and Burger2015). Initially, cattle were bred as multipurpose animals and were used for both food production (milk and meat) and labour, such as draught work. Thanks to their polygastric digestive systems, ruminants including cattle are able to process fibrous, cellulose-rich plant material, thus avoiding direct competition with humans for food resources. This has supported a successful and enduring coexistence between cattle and humans, particularly in grassland and alpine areas where challenging climates and topography limit crop cultivation. Specialized breeding schemes have notably improved animal performance over the years, especially for production traits like milk production and composition and meat yield as well as fertility traits (e.g. Miglior et al., Reference Miglior, Fleming, Malchiodi, Brito, Martin and Baes2017). However, intensive selection for milk yield has transformed many modern dairy breeds, such as Holstein Friesian, Jersey and Brown Swiss, from originally multipurpose animals into specialized dairy breeds (Berry, Reference Berry2021; Hulsegge et al., Reference Hulsegge, Oldenbroek, Bouwman, Veerkamp and Windig2022; Zanon et al., Reference Zanon, Costa, De Marchi, Penasa, Koenig and Gauly2020a, Reference Zanon, Koenig and Gauly2020b). Furthermore, this intense focus on milk production has created an economic and ethical dilemma: surplus calves, especially bull calves and additional female calves not needed for restocking, have low market demand due to their poor fattening performance relative to dual-purpose or beef breeds (Geuder et al., Reference Geuder, Pickl, Scheidler, Schuster and Götz2012; Zanon et al., Reference Zanon, Degano, Gauly, Sartor and Cozzi2023). As a result, many of these calves are either euthanized shortly after birth or briefly reared and then sold at low prices to abattoirs, where they are used for secondary products, such as hides, pet food or rennet (Haskell, Reference Haskell2020). In addition, the low economic value often correlates with suboptimal animal welfare practices, particularly during transport (Roadknight et al., Reference Roadknight, Mansell, Jongman, Courtman and Fisher2021). To overcome these ethical and economic problems in dairy production, various strategies are currently in practice. One approach is to use sexed semen to avoid surplus male calves (Balzani et al., Reference Balzani, Aparacida Vaz Do Amaral and Hanlon2021). However, female calves also often exceed replacement needs, with an estimated 40% surplus (de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Overton, Fetrow, Leslie, Elcker and Rogers2008), which necessitates the development of a viable market demand for their use in beef production. An alternative strategy is crossbreeding dairy cows with beef bulls to produce F1 calves that exhibit good fattening performance, thereby increasing their market value and demand (Berry, Reference Berry2021; Basiel and Felix, Reference Basiel and Felix2022). This crossbreeding trend has been observed in several countries (e.g. Fouz et al., Reference Fouz, Gandoy, Sanjuan, Yus and Dieguez2013; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Fikse, Carlen, Poso and Aamand2019; Zanon et al., Reference Zanon, Degano, Gauly, Sartor and Cozzi2023) and holds the potential to improve the overall sustainability of dairy and beef farming (Faverdin et al., Reference Faverdin, Guyomard, Puillet and Forslund2022). However, crossbreeding with beef bulls could result in dystocia, especially in primiparous cows, and may lead to higher calf mortality, reduced milk yield and fertility and compromised health in dairy cows (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Cassell, McAllister and Washburn2009; Fouz et al., Reference Fouz, Gandoy, Sanjuan, Yus and Dieguez2013). In this regard, it is important to mention that genetic indices for beef sires for crossbred calves are available to counter this problem (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Amer, Evans, Byrne, Cromie and Hely2019). Consequently, dystocia might be responsible for a subsequent poor fattening performance and consequently hamper production efficiency because calves as well as cows require more time to recover from such an event (Barrier et al., Reference Barrier, Haskell, Birch, Bagnall, Bell, Dickinson, Macrae and Dwyer2013). To the best of our knowledge, no previous study investigated the effect of calving ease in combination with parity and breeding strategy (beef × dairy vs. purebred dairy) on fattening performance and carcass conformation and quality parameters. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess the effect of crossbreeding with Belgian Blue bulls besides pure breeding in large Holstein-Friesian dairy herds on calving ease and subsequent fattening performance, carcass conformation and quality considering a substantial sample size of breeding and fattening animals as well as the season of calving. We hypothesized that crossbreeding depending on the sire breed (purebred Holstein Friesian vs. Belgian Blue) might have a negative impact on calving ease and subsequent growth performance and carcass traits.

Materials and methods

All procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Research Centre for Agriculture and Fisheries, the Free University of Bolzano. The procedures for the care and handling of the animals used in the study were in accordance with the European Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.

Study farms

Calving data of the bulls originate from the test herd program of RinderAllianz and Rinderproduktion Berlin Brandenburg. The test herd program consists of 90 farms that record precise information on calving, the development of the animals in calf and rearing cattle, and the performance and health data of the dairy cows. The farms had an average of 806 cows, with farms from 116 to 3,246 cows participating in the project. In 2024, the audited herdbook cows had a weighted average 305-d yield of 10,973 kg of milk with 3.9% fat and 3.4% protein.

Data collection and editing

Analyses were based on 101,226 births of male calves from the test herds from 2019 to 2021 (Fig 1). For each calving, calving ease, sex, birth weight and the breed of the dam and sire were recorded. These data were compared with the slaughter data from the Danish Crown slaughterhouse in Teterow (Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany). About 5,162 of 101,226 bulls were slaughtered at this abattoir and accordingly data on carcass weight, age at slaughter, average daily weight gain, carcass confirmation and fat classification were available. Carcass confirmation was rated with the EUROP grid, where E indicates a convex and well-defined carcass morphology, R corresponds to a median or rectilinear profile, while P is characterized by a more simplified carcass structure with a concave contour (Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine, Ireland, 2020). Carcass fat cover is classified on a 1–5 basis, with 1 being very lean and 5 being very fat (Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine, Ireland, 2020). Only bulls in category A (young bull meat), i.e. bulls aged between 12 and 24 months, were included in the analysis. From the 5,162 uncastrated bulls considered in the study, 555 were crossbred animals (Belgian Blue × Holstein Friesian), 4,216 (Holstein Friesian × Holstein Friesian) and 391 (Red Holstein × Holstein Friesian – considered together with the progeny of Holstein-Friesian sires) (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the selection process and investigated parameters of the study.

Calving ease was classified according to a 5-point scale, where 0 = not specified indicates not observed calving or no information available, 1 = easy indicates without help or help not necessary, night calving, 2 = medium indicates an assistant or light use of mechanical traction aid, 3 = difficult indicates several helpers, mechanical pulling aid and/or vet and 4 = surgery indicates caesarean section, foetotomy. All parity numbers > 4 were summarized in category 4. Female calves (n = 4 animals) were excluded from the analysis. The final dataset used for statistical analysis contained information on calving ease, sire and mother animals, fattening farm, farm of origin as well as fattening performance and carcass quality parameters from 5,162 bulls.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS-software v. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normal distribution was applied. Data were analysed using a mixed linear model (‘proc glimmix’) with fixed effects of breed of the calves (purebred Holstein Friesian vs. crossbred with beef sire F1 calf), number of parities of the cow, calving ease and season of calving (Spring [March–May], Summer [June–August], Autumn [September–November], Winter [December–February]) on animal-based measures as the main effects. The farm of origin was considered as a random effect in the model. Post hoc Tukey–Kramer test was used for testing significant difference between least square means. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. The statistical model was as follows:

Y = Calf breed + Parity + Calving ease + Calving Season + Farm + ε

where Y is the animal-based measures (birth weight, age at slaughter, average daily weight gain, carcass weight, EUROP carcass confirmation and carcass fat cover) and ε is the random residual.

Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics

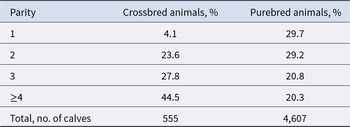

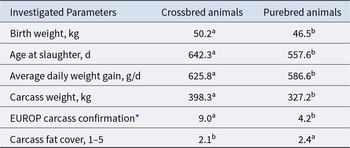

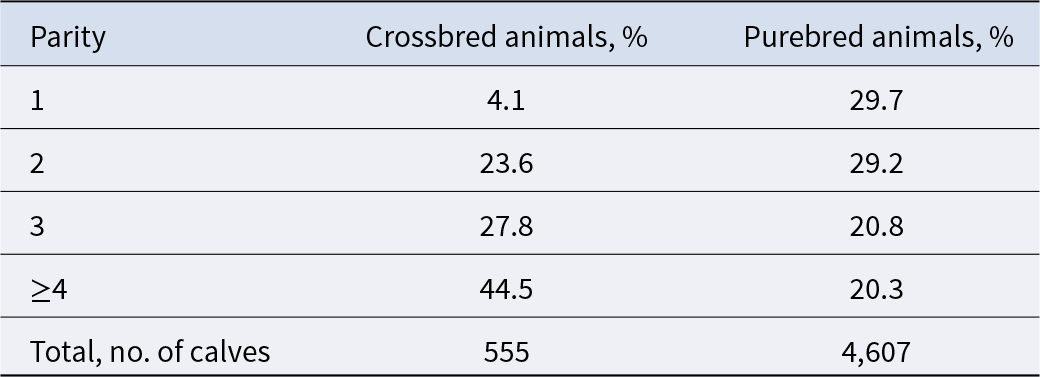

The birth weights of calves in our study population ranged between 20.0 and 74.0 kg with an average value of 44.7 kg (Table 1). Age of slaughter averaged 558.9 ± 87.4 d and the average daily weight gain (birth to slaughter) over all animals was low, at only 596.1 ± 78.7 g/d. The relatively low average daily weight gain could be related to the low amount of maize silage and the high proportion of grass silage in the feed ratio, as well as the use of feed leftovers from dairy cattle feeding observed in participating farms. The average carcass weight was 333.1 ± 66.2 kg with a minimum of 61.5 kg and a maximum of 529.5 kg. Regarding carcass quality parameters, the average EUROP carcass conformation varied from P to R−, with O being most frequent (Table 1). Carcass fat cover averaged at 2.4 ± 0.6 (Table 1). The average parity number of investigated cows was 2.6. Most sires used in the test herds were specialized purebred dairy breeds, with 82% being Holstein Friesian and 8% Red Holstein (Table 2). The remaining 10% of sires were Belgian Blue. While dairy bulls were equally used over all lactations, crossbreeding with beef bulls was more frequent in higher lactations (Table 2).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for investigated parameters

a E = 13, U + = 12, U = 11, U− = 10, R+ = 9, R = 8, R− = 7, O+ = 6, O = 5, O− = 4, P+ = 3, P = 2, P− = 1.

b 0 = not specified, 1 = easy calving, 2 = middle, 3 = difficult calving, 4 = surgery.

Table 2. Cattle breeds used in investigated test herds and frequency of crossbreeding and pure breeding used over different parities

Impact of crossbreeding with Belgian Blue sires on investigated parameters

Crossbreeding had a significant effect on all parameters studied (Table 3). Birth weight was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in crossbred animals (50.2 kg vs. 46.5 kg in purebred calves), which might be related to more muscular calves produced by Belgian Blue sires (Table 4). Similarly, Arens et al. (Reference Arens, Sharpe, Schutz and Heins2023) observed higher birth weights in crossbred calves where the sire was a beef bull. Batra and Touchberry (Reference Batra and Touchberry1973) observed higher birth weights in crossbred animals as well. However, authors only considered dairy breeds in the crossbreeding scheme (Holstein Friesian and Guernsey). Therefore, there might be some additional positive heterosis effect on increased birth weight due to crossbreeding as described previously by Gregory et al. (Reference Gregory, Cundiff and Koch1991) and Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Aguilar, Rekaya and Bertrand2010). For carcass conformation, crossbred animals (approx. R+) received a significantly higher EUROP rating than purebred animals (approx. O−) (p < 0.05, Table 4). Carcasses from purebred animals were predominantly rated O (67.5%) or P (19.9%), whereas those from crossbred animals were more frequently rated R (49.0%) and U (31.0%) (Table 4). The higher EUROP rating in crossbred animals is in line with previously published studies (e.g. Keane, Reference Keane2010; Huuskonen et al., Reference Huuskonen, Pesonen, Kämäräinen and Kauppinen2013; Vestergaard et al., Reference Vestergaard, Jorgensen, Cakmakci, Kargo, Therkildsen, Munk and Kristensen2019; Eriksson et al., Reference Eriksson, Aks-Gullstrand, Fikse, Jonsson, Jå, Stålhammar, Wallenbeck and Hessle2020) who observed significantly (p < 0.05) higher carcass conformation in crossbred Holstein × Beef cattle animals than in purebred Holstein-Friesian. Conversely, carcass fat cover was significantly higher in purebred Holstein animals (p < 0.05), with 46.1% and 48.2% of carcasses rated 2 and 3, respectively. For crossbred animals, 87.4% of carcasses were rated 2, and 11.9% were rated 3 (Table 4). Similarly, Keane and Drennan (Reference Keane and Drennan2008) and Keane (Reference Keane2010) described a higher fat score in purebred Holstein steers than in crossbred Belgian Blue × Holstein animals. In contrast, Huuskonen et al. (Reference Huuskonen, Pesonen, Kämäräinen and Kauppinen2013) and Eriksson et al. (Reference Eriksson, Aks-Gullstrand, Fikse, Jonsson, Jå, Stålhammar, Wallenbeck and Hessle2020) observed a better fat cover in crossbred animal, especially when early maturing beef breeds were used. This can be beneficial or detrimental depending on the category of animal and the management approach, as excessively lean or overly fat carcasses tend to have lower market value (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Drennan, McGee, Kenny, Evans and Berry2009). Late-maturing breeds generally begin accumulating fat at a higher body weight than dairy breeds (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Drennan, McGee, Kenny, Evans and Berry2009). Thus, crossbred animals with sires from late-maturing beef breeds are expected to produce leaner carcasses compared to purebred dairy animals when slaughtered at the same weight, as shown in our results. Moreover, average daily weight gain and carcass weight were significantly higher in crossbred animals (625.8 g/d vs. 586.6 g/d in purebred calves), which might be partly explained by breed effect as specialized beef breeds exhibit a better fattening performance than specialized dairy breeds (e.g. Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Drennan, McGee, Kenny, Evans and Berry2009; Geuder et al., Reference Geuder, Pickl, Scheidler, Schuster and Götz2012). In addition, the higher average daily weight gain in crossbred animals might be partly related to heterosis effect (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Aguilar, Rekaya and Bertrand2010; Wetlesen et al., Reference Wetlesen, Åby, Vangen and Aass2020). However, age at slaughter was also significant (p < 0.05) higher in crossbred animals which might be explained using mostly late mature beef sires like Belgian Blue in our case which take more time to achieve a satisfying carcass fat cover than purebred dairy breeds (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Drennan, McGee, Kenny, Evans and Berry2009). In addition, farmers tended to slaughter purebred bulls earlier which might be related to an earlier fat deposition and resulting in high fat content and in the carcass in Holstein fattening bulls than in dual purpose or beef cattle breeds (Velik et al., Reference Velik, Terler, Berger, Kitzer, Häusler, Eingang, Kaufmann, Royer, Adelwöhrer and Gruber2023). Besides fattening performance, feed intake and efficiency are becoming more and more crucial parameters, especially in the sustainability debate for beef production (Sabia et al., Reference Sabia, Zanon, Braghieri, Pacelli, Angerer and Gauly2024). In this regard, Pfuhl et al. (Reference Pfuhl, Bellmann, Kühn, Teuscher, Ender and Wegner2007) showed in their experiment where they compared the fattening performance and feed efficiency of Charolais and Holstein bulls, that the former were more efficient in terms of carcass yield and energy expense per kg body weight. In contrast, Holstein bulls had a better marbling score which the authors attribute to the capacity of dairy breeds to store fat as an energy source for milk production, while the specialized beef breed shows a higher capability for extended protein accretion (Pfuhl et al., Reference Pfuhl, Bellmann, Kühn, Teuscher, Ender and Wegner2007). In addition, several candidate genes associated with improved feed efficiency in beef cattle have been identified (e.g. Seabury et al., Reference Seabury, Oldeschulte, Saatchi, Beever, Decker and Taylor2017; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Beever, Decker, Freetly, Garrick and Weaber2017; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Huang, Pan and Wang2023). Notwithstanding, a review by Kenny et al. (Reference Kenny, Fitzsimons, Waters and McGee2018) indicated that the accuracy of genomic predictions for feed efficiency is currently too low to allow for the selection of breeding candidates solely based on genomic data, without phenotypic measurements. Obtaining such phenotypic data is both complex and costly (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, MacNeil Dekkers, Crews, Rathje, Enns and Weaber2013). Furthermore, calculating genomic estimated breeding values necessitates a reference population where animals have been both genotyped for specific markers and phenotyped for the target trait, like feed efficiency (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Fitzsimons, Waters and McGee2018). Advancements in breeding for improved feed efficiency in beef cattle will ultimately depend on the integration of genomic data into robust, multi-trait genomic selection programs at national and international scales. Besides feed efficiency, also food–feed competition is becoming increasingly relevant, especially for ruminant livestock production systems. In this regard, the focus should be put on roughage-based fattening systems to enhance net protein production and reduce the human edible fraction in the feed ratio (Zanon et al., Reference Zanon, Degano, Gauly, Sartor and Cozzi2023, Reference Zanon, Hoertenhuber, Fichter, Peratoner, Zollitsch, Gatterer and Gauly2024; Sabia et al., Reference Sabia, Zanon, Braghieri, Pacelli, Angerer and Gauly2024). The high proportion of grass silage in the feed ratio observed in participating farms reflects a roughage-based fattening systems which, as mentioned earlier, has the drawback of relatively low average daily weight gain. In relation to our study, feed intake data were not collected, and thus, we cannot provide insights into feed efficiency and sustainability for the animal groups under investigation. However, the complex biological interactions between genotype and environment regarding feed efficiency is crucial and should be considered in future research to better understand its effect on our analysed parameters.

Table 3. F- and p-values of considered effects on investigated parameters

Note: Letters in bold indicate significance (p < 0.05).

Table 4. The effect of cattle breed on birth weight, fattening performance and carcass quality parameters in investigated animals

Note: Different superscript letters within the same row indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

* E = 13, U+ = 12, U = 11, U− = 10, R+ = 9, R = 8, R−= 7, O+ = 6, O = 5, O- = 4, P+ = 3, P = 2, P− = 1.

Role of parity and calving ease on investigated parameters

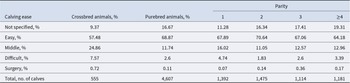

Parity order in evaluated dairy cows showed a significant effect only on birth weight, with no significant impact on the other investigated parameters (Table 3). The significantly higher birth weight observed in multiparous cows (p < 0.05) may partly be attributed to the increased use of beef sires (Table 2), as well as to the larger body structure compared to primiparous cows (Condon et al., Reference Condon, Murphy, Sleator, Ring and Berry2024). A higher incidence of dystocia was noted among crossbred calves and in primiparous cows (Table 5), aligning with findings from Fouz et al. (Reference Fouz, Gandoy, Sanjuan, Yus and Dieguez2013) and Eriksson et al. (Reference Eriksson, Aks-Gullstrand, Fikse, Jonsson, Jå, Stålhammar, Wallenbeck and Hessle2020). Studies indicate that primiparous cows are more susceptible to dystocia than multiparous cows, primarily due to a higher occurrence of fetopelvic disproportion and vulval stenosis (De Amicis et al., Reference De Amicis, Veronesi, Robbe, Gloria and Carluccio2018; Tsaousioti et al., Reference Tsaousioti, Praxitelous, Kok, Kiossis, Boscos and Tsousis2023). Additionally, crossbreeding with beef sires has also been associated with increased dystocia risk (Berry et al., Reference Berry2021). However, Basiel and Felix (Reference Basiel and Felix2022) reported no increase in dystocia risk when using beef semen for dairy herds. Calving ease significantly affected birth weight, age at slaughter and carcass weight, while it had no effect on average daily weight gain or carcass quality parameters (EUROP conformation and fat cover) (Table 3). Calves experiencing more challenging births (moderate difficulty, difficult or requiring surgical intervention) had significantly higher birth weights (p < 0.05) than those born through easy calving (Table 6). Bigger and heavier calves can result in a foetal–maternal size mismatch, raising the likelihood of dystocia, particularly in primiparous cows as previously mentioned. Calves that survive dystocia often face reduced passive immunity transfer, higher mortality rates and increased physiological stress markers, resulting in compromised welfare during the neonatal period and potentially beyond (Barrier et al., Reference Barrier, Haskell, Birch, Bagnall, Bell, Dickinson, Macrae and Dwyer2013).

Table 5. Frequency distribution of calving ease over cattle breed and parities

Table 6. The effect of calving ease on birth weight, fattening performance and carcass quality parameters in investigated animals

Note: Different superscript letters within the same row indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

** E = 13, U+ = 12, U = 11, U− = 10, R+ = 9, R = 8, R− = 7, O+ = 6, O = 5, O− = 4, P+ = 3, P = 2, P− = 1.

Seasonal influences on investigated parameters

Calvings were equally distributed throughout the year (25.5% Spring, 27.9% Summer, 26.2% Autumn, 20.4% Winter) showing no clear seasonal prevalence. Of the investigated parameters, only the fattening performance parameters carcass weight and average daily weight gain were significantly (p < 0.05) effected by the calving season (Table 3). Spring and summer calves displayed a significantly (p < 0.05) higher weight gain than calves born in autumn and winter (Table 7). Similarly, carcass weight was significantly (p < 0.05) highest for spring calves. The enhanced fattening performance (average daily weight gain and carcass weight) could be related to warmer temperatures as well as to the access of the best forages in those seasons in investigated region, which in combination promotes a fast development and lower probability of disease outbreak or mortality (Rinella et al., Reference Rinella, Bellows, Geary, Waterman, Vermeire, Reinhart, Van Emon and Cook2022). Therefore, in our case a seasonal calving practice could be beneficial to enhance farm productivity. However, market demand as well as farming structures and management are crucial in evaluating if seasonal calving practice is practically suitable or not for respective farm.

Table 7. The effect of calving season on birth weight, fattening performance and carcass quality parameters in assessed animals

Note: Different superscript letters within the same row indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

* Spring (March–May), Summer (June–August), Autumn (September–November), Winter (December-February).

** E = 13, U+ = 12, U = 11, U− = 10, R+ = 9, R = 8, R− = 7, O+ = 6, O = 5, O− = 4, P+ = 3, P = 2, P− = 1.

Conclusions

To provide a holistic overview on the beef-on-dairy strategy, besides assessing fattening and carcass quality parameters, for the first time the effect of calving ease, calving season and parity of the cow on the subsequent fattening performance were considered. Crossbreeding with Belgian Blue sires was shown to have an advantageous effect on fattening performance and carcass conformation and therefore allowing to produce valuable fattening animals from dairy production for possibly solving the ethical dilemma of not rentable bull calves of specialized dairy breeds. However, crossbred calves showed a higher frequency of having had a difficult birth. The latter could be shown to result in poor fattening performance besides the already known harmful effect on calf health. Bulls from spring and summer calving performed better for some investigated parameters. However, whether a seasonal calving is feasible or not is dependent on the available farm structures and management as well as the market demand. Future studies should consider feed efficiency as well for deepen the knowledge in the sustainability debate of the beef sector.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the test herd farmers, who voluntarily participated in the study and the RinderAllianz and Rinderproduktion Berlin-Brandenburg for providing the test herd data as well as Danish Crown Teterow for the carcass parameters. Furthermore, Dr. Thomas Zanon would like to thank the Free University of Bolzano and the Institute of Livestock Farming at the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Research Centre for Agriculture and Fisheries for the possibility to have spent the visiting researcher period in Rostock.

Funding statement

The authors would like to thank the Open Access Publishing Fund of Free University of Bolzano for funding the publication.

Competing interests

The authors have not stated any conflicts of interest.

Animal and human care and use approval

All procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Research Centre for Agriculture and Fisheries and the Free University of Bolzano. The procedures for the care and handling of the animals used in the study were in accordance with the European Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.