Introduction

Constitutional courts are political as much as judicial institutions. As such, public trust, perception of legitimacy and diffuse support matters for their long-term viability. In his famous conceptualization, Easton (Reference Easton1975: 444) defined ‘diffuse support’ as a ‘reservoir of favourable attitudes or good will that helps members to accept or tolerate outputs to which they are opposed or the effects of which they see as damaging to their wants’. Following this definition, diffuse support should facilitate the acceptance by citizens of constitutional court decisions running counter to their preferences.

For Easton, diffuse support had two main dimensions: political trust and legitimacy (Easton, Reference Easton1975). The legitimacy of political objects is the conviction ‘that is right and proper… to accept and obey the authorities and to abide by the requirements of the regime’ (Easton, Reference Easton1975: 451). In turn, political trust has been defined as a ‘global affective orientation toward government’ (Rudolph and Evans, Reference Rudolph and Evans2005: 661), and as a ‘form of diffuse support that political system receives from its environment’ (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marien and Hooghe2011: 267). Easton, however, gave a more straightforward definition of trust as the feeling by members of a community that ‘their own interests would be attended to even if the authorities were exposed to little supervision or scrutiny’ (Easton, Reference Easton1975: 447). Subsequent literature has showed the importance of trust for the stability of democracies (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington1998: 792; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marien and Hooghe2011: 267).

According to these definitions, constitutional courts should have high levels of diffuse support if citizens feel that it is right to accept their decisions – legitimacy – and when they believe that constitutional court decisions will take into account their preferences – trust. More specifically, we understand that diffuse support means, in the case of these institutions, that citizens approve of the existence of a constitutional court and its authority even when the institution makes decisions that run counter to their preferences. Trust, in turn, means for these courts that citizens perceive constitutional judges as taking into account their interests, for instance when they decide on the constitutionality of legislation. However, to what extent citizens trust constitutional courts and why is a largely unresolved empirical question.

The case of constitutional courts contrasts with that of other political institutions. There is an extensive body of evidence-based literature about support, trust and legitimacy of the government or of institutions such as parliaments (Magistro et al., Reference Magistro, Dotti Sani and Magistro2016; Inter alia Miller, Reference Miller1974; Rose et al., Reference Rose, Mishler and Rose2001). When it comes to trust in judicial institutions, there has been significant research about the US Supreme Court. Research by Gibson (Reference Gibson2007) showed that support for this institution is embedded as part of stable democratic values and did not historically depend on policy agreement or partisanship. Gibson and Nelson (Reference Gibson and Nelson2014) concluded that individual rulings have little impact on support for the institution. Against this background, however, more recent research has found evidence of affective polarization in the US having an impact on support for the Supreme Court (Armaly and Enders, Reference Armaly and Enders2022).

In the case of Kelsenian constitutional courts, empirical research on these aspects is much scarcer. This is striking, given the political importance of constitutional courts. Modelled on the ideas of the Austrian jurist Hans Kelsen (see Kelsen, Reference Kelsen1942), constitutional courts monopolize in the countries where they exist the capacity to declare the unconstitutionality of legislation. After the Second World War, they also are the ultimate guarantee for the enforcement of constitutional fundamental rights in many countries (Stone Sweet, Reference Stone Sweet2002).

As a central institution in many democracies, the construction of diffuse support for constitutional courts is essential for the stability of the system. Literature on these institutions has referred to at least three factors with the potential to affect the way citizens perceive them. The first one is the political-democratic aspects of constitutional courts, and particularly the appointment of constitutional judges by democratically legitimized actors (see Gamper, Reference Gamper2015: 436). The second factor refers to judicial-technocratic aspects, which are maximized when the court is deemed to be as neutrally, efficiently and impartially applying the constitutional framework to the cases (Castillo-Ortiz, Reference Castillo-Ortiz2020). Finally, output-related construction of support depends on the decisions of the constitutional court: given that courts act in the context of a triadic mode of dispute resolution (Stone Sweet, Reference Stone Sweet1999), citizens whose policy preferences are antagonized by the decisions of the constitutional court might lose trust in the institution.

Literature about constitutional courts and their role in democracies is overwhelming, although most work on this topic is so far theoretical and doctrinal (inter alia Bellamy, Reference Bellamy2007; Ferrajoli, Reference Ferrajoli2020; Waldron, Reference Waldron2006). This article aims at contributing to debates about constitutional review with empirical evidence about how constitutional courts actually construct one of the two core elements of diffuse support: political trust. In particular, the article will inquire to what extent these three aspects of constitutional courts – democratic aspects, technocratic elements and outcomes of decision-making - matter when it comes to fostering citizens’ trust in the constitutional court.

To answer this research question, the article uses the case of the Spanish Constitutional Court in the aftermath of its decision on the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia (2010-2011). We believe the study of this institution is interesting because of the similarities of the Spanish Constitutional Court with its Kelsenian counter-parts in other European countries. With caveats related to the specificity of each case, this allows the findings of this paper to feed back to general literature in the field for this world region. Indeed, European democracies share many common features with the Spanish case when it comes to its constitutional court: they generally rely on the centralized Kelsenian model; they often implemented this model in processes of transition to democracy; and constitutional courts in the region require their judges to have some technical legal expertise; yet, they are appointed by political actors.

The article shows that a perceived lack of court independence has strong detrimental effects on public trust in the institution. This reinforces the idea that judicial-technocratic elements matter for constitutional courts. Evidence about political-democratic aspects of the design of the court and their impact on public trust is however weak at best. This empirical evidence runs counter to an important narrative about constitutional courts, which emphasizes the need for democratic legitimacy of these institutions, often materialized in the political-democratic input into the procedures of appointment of constitutional judges (Kumm, Reference Kumm2017: 60–61; see Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2007: 32). Contrary to this idea, the findings suggest that in order to construct trust – and thus diffuse support- in constitutional courts, increasing the independence of these institutions would be a right move. This matters particularly in the European context, in which examples of Kelsenian courts with non-political mechanisms of appointment of judges are, to the best of our knowledge, non-existent.

This article is structured as follows. After this introduction, we give some background information about the Spanish Constitutional Court and its 2010 ruling on the Catalan Statute of Autonomy. This background information is necessary to understand the rest of the article. Then, we move on to explain the theoretical framework of the research and the main hypotheses. Next, the article discusses the data used for the research. The following section presents the empirical findings. As explained above, we find evidence supporting the idea that citizens’ trust in the constitutional court is associated to their view of the institutional independence of the court and to judicial outcomes, but not so much to the idea of a democratic input into the appointment of judges. The following section discusses the findings, and the last section concludes.

The background: the Spanish Constitutional Court and the ruling on the Catalan Statute of autonomy

The politics of institutional design of the Spanish Constitutional Court

The current Spanish Constitutional Court was created by the Spanish Constitution of 1978 following the Kelsenian model. Such a model is dominant in Europe (Comella, Reference Comella2004; Stone Sweet, Reference Stone Sweet2003), and is present in many other parts of the world. Following the ideas of the Austrian jurist Hans Kelsen, in this model the powers of constitutional review are monopolized by a single institution, the Constitutional Court, that is formally separate from the judicial branch (Kelsen, Reference Kelsen1942).

In Spain, the Constitutional Court is regulated in Part IX of the Constitution. Art.159 of the Spanish Constitution is the most relevant to the purposes of this research, because its two first paragraphs contain, respectively, the political-democratic and judicial-technocratic elements of the court whose impact on citizens’ trust we scrutinize in this article. According to Art.159.1:

‘The Constitutional Court shall consist of twelve members appointed by the King. Of these, four shall be nominated by the Congress by a majority of three-fifths of its members, four shall be nominated by the Senate with the same majority, two shall be nominated by the Government, and two by the General Council of the Judicial Power’.

As can be seen, Spanish constitutional judges are appointed by political actors. In principle, there is an exception to this general rule in the appointment of two judges by the judicial council. But because the latter is since the mid-80s also appointed by political actors (Hernández González, Reference Hernández González2022; Torres Pérez, Reference Torres Pérez2018), it can be said that political elements permeate the appointment of all constitutional judges.

Political appointment of constitutional judges takes places not only in Spain: it is in fact the rule in many other Kelsenian-style courts, and it is often defended with the argument that it provides them with democratic legitimacy (Kumm, Reference Kumm2017). What is interesting in the Spanish case is the variety of political actors that participate in the appointment (the government, the two chambers of the Parliament, and the judicial council) and the supermajorities required to appoint the judges. Theoretically, this complex mechanism is aimed at avoiding the capture of the court by any specific political actor. The outcome of this model of appointment, however, is generally considered to be the creation of a quota system, in which the largest political parties appoint like-minded constitutional judges to the court (Garoupa et al., Reference Garoupa, Gomez-Pomar and Grembi2011). These parties have traditionally been the conservative Partido Popular (PP) and the progressive Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE). Furthermore, the best evidence in the field points at a certain association between decisions of constitutional judges and ideological factors or the preferences of the political parties that sponsor them (Garoupa et al., Reference Garoupa, Gomez-Pomar and Grembi2011; López-Laborda et al., Reference López-Laborda, Rodrigo and Sanz-Arcega2019).

Nevertheless, politics is not everything when it comes to the design of the Spanish Constitutional Court. Art.159.2 of the Spanish Constitution, in turn, contains the main judicial-technocratic aspect of the design of the Constitutional Court:

‘Members of the Constitutional Court shall be appointed among magistrates and prosecutors, university professors, public officials and lawyers, all of whom must have a recognized standing with at least fifteen years’ practice in their profession’.

This provision has to be read in conjunction with the rest of the Art.159, which regulates aspects such as the tenure of the constitutional judges, incompatibilities, and fixity of tenure. All of these, in turn, seem to emphasize judicial-technocratic aspects, including Art.159.5 which states that the constitutional judges ‘shall be independent’.

The question is whether ideas such as judicial independence and technical qualities of the judges are in tension with the political system of appointment of Art.159.1. Political debate in Spain seems to suggest so. It is not infrequent for political parties to include in their electoral manifestos calls to ‘de-politicize’ the court (Unidas Podemos, 2019), or to increase technocratic aspects such as the request for longer services as lawyers before being a constitutional judge (Ciudadanos, 2019). It is also not rare for politicians to exploit the political system of appointment of judges to discredit the court (Junts per Catalunya, 2019: 95), especially when it makes decisions that run counter to their preferences (Europapress, 2016; ABC, 2017).

The constitutional ruling on the Catalan statute of autonomy

As it is widely known, Spain is a decentralized state. According to Art.2 and to the whole Part VIII of the Spanish Constitution, Spanish ‘nationalities and regions’ can become Autonomous Communities, enjoying self-government. As part of this, they can have their own Governments and Parliaments. The apex rules of the legal systems of the Autonomous Communities are called Statutes of Autonomy, yet these are subject to the Spanish Constitution. For this reason, the constitutionality of Statutes of Autonomy can be assessed by the Spanish Constitutional Court.

In 2006, Catalonia passed a new Statute of Autonomy. The text of the new Statute was approved in the Catalan Parliament, amended and approved in the Spanish Parliament and finally submitted and approved by a referendum of Catalan citizens (Comella, Reference Comella2014: 574).

In 2010, the Spanish Constitutional Court gave a ruling on the constitutionality of this new Statute at the request of the opposition Partido Popular, the Omboudsman and seven other Autonomous Communities. The case was complex from a judicial politics perspective, not only for the implications of the ruling but also because of the way that the proceedings took place: some political actors asked for the exclusion of certain constitutional judges from the case on the grounds of political links to the object of the controversy (Delledonne, Reference Delledonne2011: 5).

The outcome of the case was very impactful in the constitutional and political life of Spain. As explained by Harguindéguy and others (Reference Harguindéguy, Rodríguez and Cruz Díaz2020: 230) ‘the constitutional justices accepted most of the original proposal, but 14 articles were declared unconstitutional and 23 articles and four provisions were reinterpreted. Those articles dealt with the concept of the Catalan nation, the fiscal relationship between Catalonia and Spain, the status of the Catalan language, and the nature of Spanish quasi-federalism’. For Delledonne (2011: 11), ‘Sentencia no. 31/2010 is clearly the result of a compromise between very different states of mind within the Tribunal Constitucional. Whereas some judges aimed at declaring the full illegitimacy of the Estatut, others were reluctant to be too aggressive towards it, fearing a dangerous overinvolvement of the Constitutional Court in political questions’.

Despite this, the ruling triggered a backlash among many Catalan political parties and citizens, with a reaction based ‘primarily on the idea that no court should have been empowered to invalidate what the Catalan people had ratified in referendum’ (Comella, Reference Comella2014: 575). Negative political framings of the court ruling became widespread amongst Catalan nationalist politicians (Castillo-Ortiz, Reference Castillo-Ortiz2015), who accused the institution of being biased and politicized.

After the ruling, the support for secessionism significantly increased in Catalonia. According to Muñoz and Tormos (Reference Muñoz and Tormos2015: 323), ‘The Court ruling was followed by a massive demonstration in Barcelona asking for self-determination, and contributed to an intense mobilization cycle of the pro-independence movement’.

In this article, we test to what extent this backlash had implications in terms of public trust in the Spanish constitutional court.

Theory. Explaining trust in constitutional courts

As mentioned above, Easton (Reference Easton1975) considered that diffuse support had two main components: legitimacy and trust. Literature on constitutional courts has advanced a number of theories about the legitimacy and construction of trust on these institutions. This section reviews such theories and the theoretical debates to which they have given rise. It also explains to what extent they can be applied to the case of the Spanish Constitutional Court, and formulates hypotheses that will be empirically tested later in this article.

Political-democratic appointment of constitutional judges and trust

As explained earlier, in Spain, political actors have an important role in the process of appointment of constitutional judges. In this, the Spanish Constitutional Court is not an exception. Many other courts with powers of constitutional review also rely on heavily political procedures of judicial appointment. In the US, Supreme Court judges are nominated by the President and appointed by the Senate. In Germany, the judges of the Federal Constitutional Court are appointed by super-majorities by both chambers of the Parliament. In South-Africa, the Judicial Service Commission prepares a list of candidates, and then the President in consultation with the National Assembly, chooses the judges from this list. While a great diversity exists across countries when it comes to the design of the procedure of appointment of constitutional judges, political input into such systems of appointment seems to be widespread.

This aspect of institutional design, and its implications, has been widely discussed by theoretical and doctrinal literature about these institutions. The original Kelsenian design of constitutional courts already famously gave the parliament a prominent role in the appointment of constitutional judges (Vinx, Reference Vinx2015: 48). Political-democratic appointment of judges has been justified as necessary for constitutional courts as these organs have the capacity to invalidate laws passed by a democratically elected parliament in the context of a democratic system (see Comella, Reference Comella2004: 468). From this perspective, it could be argued that constitutional courts should have a certain level of democratic legitimacy, and that this is to be achieved through the appointment of constitutional judges by democratically elected politicians.

The question, thus, is whether this form of appointment of constitutional judges also fosters trust in the institution. It could be thought that political-democratic appointment of judges should help citizens feel that they have an input into the composition of the court. However, as said earlier, not all political parties have the same level of control over the procedure of appointment of constitutional judges: generally, only the major parties do. For that reason, if this mode of appointment of constitutional judges is to foster trust in the constitutional court, it should be so especially among voters of the parties that have leverage over the appointment of constitutional judges. For that reason, it can be hypothesized that:

H1. Voters of parties that control the appointment of constitutional judges will have a higher level of trust in the constitutional court

Judicial-technocratic elements of design and trust

The second approach to the design of constitutional courts is somewhat the contrary to the former, and focuses on the technical nature of constitutional interpretation. Constitutional courts are very sui generis institutions that combine a double political and judicial nature, and that are often outside the formal structure of the judicial branch. In this respect, citizens may trust courts that align with the political values of their appointing authorities, even when such alignment may indicate a lack of institutional independence (Mazepus and Toshkov, Reference Mazepus and Toshkov2021). In these cases, trust is maintained not because of procedural impartiality, but because the court produces outcomes consistent with citizens’ political expectations (Magalhães and Garoupa, Reference Magalhães and Garoupa2023). However, constitutional courts are still judicial-type organs, that are supposed to perform their functions in the same way as any other court would do. As put by Volcansek (Reference Volcansek2019: 170–171) ‘triadic dispute settlement succeeds only when all parties to the litigation believe that the judge acts impartially, and is wholly dispassionate about who wins and loses and what is won or lost’. Courts are expected to base their decision-making process not on the personal policy preferences of judges, but rather on the juridical framework that they have to apply to the cases (Volcansek, Reference Volcansek2019: 170–171). As constitutional courts are judicial-type organs too, we can expect them to benefit from technocratic aspects, such as the legal expertise of neutral constitutional judges.

Most constitutional courts introduce technocratic elements in their design. For instance, in the case of the Spanish Constitutional Court, constitutional judges must be lawyers of a solid reputation. However, it has been argued that the political system of appointment of constitutional judges increases the political-democratic elements in the design of these courts at the expense of judicial-technocratic ones (Castillo-Ortiz, Reference Castillo-Ortiz2020). At the end of the day, the political appointment of constitutional judges might undermine the independence of the institution. Even Kelsen suggested at some point the idea of giving a prominent role in the appointment of constitutional judges to non-political actors, such as legal experts or law academics, with the argument that albeit difficult it would be desirable to avoid ‘party-political influences’ over the constitutional court (Vinx, Reference Vinx2015: 48).

Judicial-technocratic aspects, thus, should be linked to the perception of independence of constitutional judges. If constitutional judges are deemed to be agents of their appointers, their neutrality will be questioned, and so will be the legitimacy of their decisions. Judicial independence is not the only dimension of the technocratic legitimacy of courts: in addition to it, courts are expected to meet other requirements such as legal expertise, the legal quality of the decisions or neutrality. But judicial independence seems to be a pre-requisite for many of those other requirements. Moreover, there is evidence according to which the independence and accountability of judicial systems are positively associated with public trust (Garoupa and Magalhães, Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021), thus we could expect that a similar mechanism linking perceptions of independence and trust would affect the way citizens assess their Constitutional Court. All of these point at the following hypothesis:

H2. A higher perception of institutional independence is associated to a higher level of trust in the Constitutional Court

Outcome-related satisfaction and trust

Finally, there is a third potential source of trust which is output-related. This refers to the results that constitutional court action delivers. Of course, in the long run, constitutional courts are expected to deliver important political goods, such as the preservation and stability of democracy. A constitutional court unable to protect democracy and human rights is an institution deprived of its raison d’être.

In the short run, however, output-related satisfaction with the court focuses on the results of specific rulings. Like with any other judicial-type actor, in deciding cases constitutional courts create winners and losers (Stone Sweet, Reference Stone Sweet1999). This means that with every decision the constitutional court runs the risk of alienating a part of the public. To continue with Easton’s (Reference Easton1975) conceptualization, when constitutional courts have a high level of diffuse support, citizens will accept specific decisions even when these run counter to their preferences. However, at the same time, it could be argued that certain rulings that affect negatively vital interests or policy views of some citizens will in turn undermine diffuse support for the constitutional court.

The case of the Spanish Constitutional Court at the time of this analysis is particularly relevant in this regard. As explained above, the survey that we use to test our hypothesis was conducted soon after the constitutional ruling on the Catalan Statute of Autonomy. This episode can be seen as a perfect fit for the theory that a constitutional court ruling running against core policy preferences of certain citizens will undermine the trust of such citizens in the institution. For that reason, it can be hypothesized that:

H3a: Citizens living in the Autonomous Community of Catalonia will exhibit a lower level of trust in the Constitutional Court in the aftermath of the 2010 ruling on the Statute of Autonomy

The interplay between the democratic appointment of judges, technocratic qualities of the institution, and output-related trust in the court is, however, likely to be more complex. The second hypothesis (H2) of this research posed that technocratic aspects are vital for trust in the constitutional court. Following this hypothesis, it can be argued that if citizens perceive the constitutional court to be a politicized institution their tolerance for decisions contradicting their preferences will be lower. However, other citizens will perceive the constitutional court as an independent institution, one that decides cases following a neutral application of the constitutional framework to the case. For those citizens, the perception of legitimacy of the constitutional court will be higher, and so will be their tolerance to decisions contradicting their core policy preferences. For that reason:

H3b: Living in the Autonomous Community of Catalonia will have a lower negative impact on trust in the Constitutional Court for those citizens that perceive the institution as being independent.

Data

This article focuses on the case of the Spanish Constitutional Court. To test our research hypotheses, we rely on Study 2861 from the Centre for Sociological Studies (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, CIS).Footnote 1 This survey was selected for several reasons. First, it was conducted in February 2011, shortly after the 2010 Constitutional Court ruling on the Catalan Statute of Autonomy. This timing allows us to test hypotheses 3a and 3b regarding outcome-related trust in the Constitutional Court. Second, surveys that include questions about political preferences and perceptions of Constitutional Courts are extremely rare, and to our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive study available to test our theoretical expectations.

Finally, the poll included questions about trust and perception of independence in the Constitutional Court – as well as a number of other variables such as party vote-, hence we can use these data to test the rest of our hypotheses. On this latter point, however, note that the way citizens understand ‘trust’ when asked about it can, but does not need to, completely correspond with academic definitions of the concept. Thus, when it comes to feeding back into academic literature about trust the findings of this article must be taken with this caveat in mind.

We acknowledge certain limitations in using a single cross-sectional survey, as an ideal design would have been a longitudinal study spanning before and after the Constitutional Court ruling, or additional surveys across varied contexts for a more comprehensive understanding. However, in the absence of such data, this dataset captures an important moment of heightened public attention, allowing valuable insights into public trust in the court during a period of significant institutional focus.

Regarding our dependent variable, this is individual trust in the Constitutional Court and it is measured with a 11-point scale running from “no trust at all” (0) to “complete trust”Footnote 2 . Given that we have three main hypotheses, we have three main independent variables.

The first one refers to a vote to one of the parties that control the appointment of constitutional judges, hence, we included dummy variables for a vote for PP or for PSOE parties.

Our second theoretical expectation refers to perceptions of independence of the Constitutional Court and for that we included a categorical variable distinguishing whether respondents think independence of the Constitutional Court is very low, low, high or very high.

Finally, to test our outcome-oriented hypothesis we included a dummy variable that identifies citizens living in Catalonia. As control variable, we included sex, age, tertiary education and trust in national government.

Results

To test our research hypotheses, we employed two linear regression models due to the continuous nature of the dependent variable. The first model includes all variables of interest except for Catalonia, while the second model incorporates a dummy variable identifying citizens from this region. We made the decision to include all main independent variables in the same model to prevent masked effects or estimation biases. However, bivariate analyses have already yielded useful insights into the associations between the main independent variables.

As illustrated in Figure 1, perceptions of the independence of the Constitutional Court in Spain do not correlate with votes for the PP. However, this is not the case for votes cast for the PSOE, the party in government at the time of the survey. In February 2011, approximately 50 percent of Spaniards perceived the Constitutional Court to be highly or very highly independent. Notably, voters of the PSOE had a much more positive assessment of the Spanish Constitutional Court, with 56 percent of these citizens considering the Constitutional Court’s independence to be high or very high.

Figure 1. Perceived independence of the constitutional court by vote and region. Note: The y-axis presents the share of individuals by their perception of the independence of the Constitutional Court.

Conversely, a different scenario emerges for citizens of Catalonia. Following the ruling on their Statute of Autonomy, over 60 percent of individuals residing in this region perceived the Constitutional Court to be very low or low in terms of independence.

Moving to the multivariate analysis, the results of the two regression models are shown in Figure 2. As seen, the main difference between the models is that Model 1 does not include the variable of Catalonia while this is present in Model 2.

Figure 2. Regression models. Note: Dependent variable is Trust in the Constitutional Court (0–10). Note 2: Models in Table A.2 in the Appendix.

As shown, in both models the most relevant factor associated with trust in the Constitutional Court is whether individuals perceive it to be very lowly independent. This is relevant not only because it does not allow the rejection of Hypothesis 2, also because its effects overshadow those of any other variable. When citizens think the Constitutional Court as non-independent, they will also have a lower trust of it even when they vote for one of the parties responsible for appointing its members and live in the region of Catalonia.

Regarding Hypothesis 1 we find only partial support because only the voters of the PP would have significantly higher trust in the Constitutional Court. Nevertheless, the lack of statistical significance for the variable identifying voters of the PSOE could be just the result of having included trust in the government among the control variables. Thus, it is expected that voters of the PSOE would have a higher trust in the government because it is the one they chose (the Socialist José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero was the Prime Minister at the time of the survey) and, consequently, there is a high correlation between these two variables. Nevertheless, we decided to include it because trust in the national executive could also vary between voters of other parties and, in this case, we could also state that voters of the PP would have a higher trust in the Constitutional Court than non-voters of this party. Their trust also increases the higher the confidence they have in the PSOE’s government thoughFootnote 3 . Hypothesis 1 can be however rejected when we include in our models individual left-right self-placement and trust in the government, although this could be due to the high correlation between these two variables and vote for any of the two partiesFootnote 4 . The explanation is that at the time when the data for this study was collected the political system in Spain was mostly bipartisan. Hence, there was high correlation between left-right leanings and vote for one or the other mainstream party.

We also theorized citizens living in Catalonia will exhibit a lower level of trust in the Constitutional Court and we provide empirical evidence from Model 2 that fails to reject Hypothesis 3a because we see there is a negative effect of living in Catalonia in our dependent variable. This way, ceteris paribus¸ individuals living in Catalonia will answer on average that they have 0.76 points less of trust in the Constitutional Court in a scale from 0 to 10.

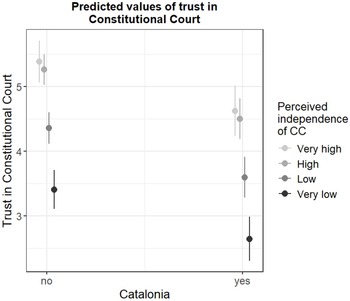

Finally, for Hypothesis 3b we included an interaction term between living in Catalonia and perceived independence of the Constitutional CourtFootnote 5 . The interaction is not statistically significant, but following the plotted predictions shown in Figure 3 we can say that citizens in Catalonia who perceive the Constitutional Court to have low independence will trust in this court similarly to those in the rest of Spain that assess the Constitutional Court to have very low independence. Even more, we can see that based on our models, citizens in Catalonia perceiving the Constitutional Court as very lowly independent will score the lowest levels of trust in this institution. Thus, again there is some support for our hypothesis.

Figure 3. Predicted values of trust in constitutional court by living in catalonia. Note: Estimates calculated from Model 1 in Table A.4 in the Appendix.

To conclude, we have to take our results for Catalonia with a grain of salt. The evidence provided here is just a fixed picture of a moment so we cannot prove there are any causal relations between the ruling on the Statute of Autonomy and the lower trust in the Constitutional Court because we have no previous data to test it. However, this same strategy would have served to reject these hypotheses if our results were non-significant or if the effects were in a different direction, and so this is positive. Thus, while more research and data should contribute to disentangle whether there is causality between outputs and trust in the court, our results do not prove any against it.

Discussion

Literature on judicial politics has discussed the impact of partisanship in support of courts, although the angle often had to do with whether partisanship or polarization are detrimental for support to higher judicial institutions (inter alia Gibson, Reference Gibson2007; Armaly and Enders, Reference Armaly and Enders2022). For the Spanish Constitutional Court, we took a different approach and seek evidence on whether partisanship could have a positive impact on trust in the institution. The idea was that voters of parties that had leverage over the appointment of constitutional judges would exhibit more trust in the court. However, we did not find significant support for this. This contrasts with judicial-technocratic aspects, for which more conclusive evidence was found. Outcome-related effects seemed to be also relevant for public trust in the Constitutional Court.

These findings matter at a practical level, as democratic and technocratic aspects of design of the constitutional court are in tension at least with regards to the procedure of appointment of constitutional judges. Appointment of constitutional judges by political actors might be undermining their independence, or at least citizens’ belief in it. Given the lower impact of political-democratic aspects in trust on the institution, it can be argued that a move towards institutional designs that favour constitutional court independence should be desirable. Institutional designs that de-politicize the appointment of (at least some) judges can include a range of options. Albeit in the European context examples of de-politicized Kelsenian constitutional courts are hard to find, inspiration can be found in other type of institutions. In the UK, ‘Senior judges in the UK’s three jurisdictions – England and Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland – are appointed without the active involvement of elected politicians. Vacancies are advertised, and independent committees – which include judges – recommend the best qualified candidates to ministers. There is some room for ministerial veto, but very little’ (Wyatt, Reference Wyatt2023). In their discussion of judicial councils as fourth-branch institutions (Kosař et al., Reference Kosař, Šipulová and Kadlec2024: 28) point at some ideas that could be applied to constitutional court judges, as they suggest that council members could be ‘chosen by the Bar, professional organizations, the ombudsperson, law schools, other independent agencies or other fourth-branch institutions such as the audit offices, anti-corruption bodies or central banks’.

At the same time, output-related construction of trust in the constitutional court is not totally unrelated to the debate between political-democratic and judicial-technocratic elements of the design of the institution. On the one hand, we have shown that constitutional courts are distrusted by citizens that feel that the decisions of the court run counter to their core political preferences. On the other hand, a constitutional court whose judges were not politically appointed should increase its judicial technocratic reputation as an independent court. The combination between these aspects is however paradoxical. In making use of its independence, it would be easier for the court to make counter-majoritarian decisions, running against the preferences of political majorities, and thus alienating a higher proportion of the public. On the other hand, being independent, the technocratic-legitimacy of the constitutional court would make these decisions easier to accept even by citizens whose preferences the court disregards. More independence probably means that the court will disappoint more citizens more frequently, but to a lesser extent or with less intensity each time.

All of above point at trade-offs in the design of Kelsenian courts that are hard to circumvent. Literature suggests that judges often anticipate the majority preferences of citizens and avoid decisions that run counter to them (McGuire and Stimson, Reference McGuire and Stimson2004). This behaviour, however, depends in turn on factors such as the capacity of the court to obtain – often imperfect- information on social preferences, and on its willingness – and incentives – to adapt its behaviour to them. These two factors will not always concur to cases.

Alternatively, accommodating these conflicting demands could be carried out through changes in the different dimensions of the institutional design of the constitutional courts. The changes could involve procedures of appointment of constitutional judges that are less political combined with a more strict focus of constitutional court activity on essential aspects of democracy and human rights (Castillo-Ortiz, Reference Castillo-Ortiz2020). Variations of institutional design of this type might have the potential to increase the judicial-technocratic aspects of design of the constitutional court and to minimize the creation of policy losers in the outcome-related dimension of trust.

Conclusion

Theoretical literature has suggested that democracies need a separation between the functions of creation – by democratically legitimized actors- and application – by courts – of the law (Sandro, Reference Sandro2022). With that background, it could be argued that a political-democratic appointment of constitutional judges becomes less necessary and, instead, constitutional courts would benefit from maximized technocratic qualities: independence, expertise and neutrality of constitutional judges. This is because the main function of constitutional courts is one of application of (constitutional) law, and thus the qualities that constitutional judges should have relate to their technical expertise and independence.

This article has found empirical evidence suggesting that citizens might share this view of constitutional courts, and in particular it has underlined the importance of the perception of independence for trust in these institutions. Technocratic aspects might even temper the –unsolvable- problem of judicial decision-making creating, by definition, a victor party and a defeated party when they make their decisions (Stone Sweet, Reference Stone Sweet1999). Because of the similarities of the Spanish Constitutional Court with other Kelsenian institutions in similar democratic settings, the findings of this article have a potential for generalizability.

At the practical level, the evidence provided by this article points at a weakness in the design of most European constitutional courts, that relies on political actors to appoint constitutional judges instead of focusing on maximizing judicial independence. This adds to concerns about the political appointment of judges being instrumental to their takeover by illiberal actors in certain polities (Bugarič and Ginsburg, Reference Bugarič and Ginsburg2016; Scheppele, Reference Scheppele2013). Based on this, we suggest that it is time to rethink the design of constitutional courts, moving towards less partisan procedures of appointment of constitutional judges. These could range from consensual appointments -as opposed to majoritarian or those based on party quotas- to the inclusion of legal professions, law academics or ordinary judges in the procedures of appointment. The lack of empirical instances of this, at least in the European continent, is a real obstacle for such a type of transformation of constitutional courts. But countries that are experiencing reputational crises in these important institutions should consider reforms along those lines. In so doing, the goal should be the maximization of institutional independence, and thus of citizens’ trust in these courts.

This study has provided valuable insights into public trust in the Spanish Constitutional Court following the pivotal 2010 ruling on the Catalan Statute of Autonomy, although there are limitations and challenges to acknowledge. We have had to rely on a single survey conducted in the immediate aftermath of this ruling, so we cannot measure changes in trust over time or draw overwhelming causal conclusions. Although an ideal design would include longitudinal data from before and after the ruling, such pivotal judicial decisions are relatively rare, making comparable datasets difficult to obtain even in future research. Consequently, we emphasize that our findings capture trust dynamics at a unique historical moment, with the limitations discussed suggesting avenues for further research using longitudinal or even experimental approaches.

We still believe, however, that our findings will make a significant contribution to a debate that has thus far been conducted mostly at the theoretical level. While the questions associated to constitutional review have a conceptual dimension that theoretical debates are well placed to address, it also has an empirical dimension. Despite the limitations inherent in all empirical research like ours, we hope that the evidence-based input that we provide in this article will be helpful to our understanding of how to design more resilient constitutional courts, that are well equipped to protect constitutional democracy.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773925100180.

Data availability statement

The data used to carry out this research is freely available at the website of the Spanish Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS), study 2861, and can be downloaded here: https://www.cis.es/es/web/cis/detalle-ficha-estudio?origen=estudio&idEstudio=10804&idPregunta=508103&idVariable=441586

Ethics approval

This research received ethics approval by the research services of the University of Sheffield, where one of the authors of the paper is based (Application 058987). The research uses data from an anonymous survey of the Spanish ‘Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas’ (CIS). The data available was collected by CIS according to the Spanish legislation, anonymized and made publicly available for purposes of secondary research.

Competing interests

None of the authors has any competing interests to disclose