Introduction

‘Women's rights are under threat from a ‘backlash’ of conservatism and fundamentalism around the world’. (United Nation's forum 2018)Footnote 1

‘Every single migrant poses a public security and terror risk’. (Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban, 2016)Footnote 2

Throughout Western democracies, social conservatives are fuelling backlash to social liberalism with claims of increasing cultural ‘threats’ to the social order (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Social conservatism in contemporary societies can generally be understood as ‘traditional, authoritarian and nationalist’ (TAN) values (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). Backlash, describes a resistance to change in the status quo, aiming to preserve existing or revert to previous power structures in society, and comes at the cost of minorities’ power struggles (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016). Much of the backlash research has focused on social conservatives’ backlash to the cultural ‘threat’ of immigration (Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2015; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2005, Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Oosterwaal & Torenvlied, Reference Oosterwaal and Torenvlied2010; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008), while a smaller body of more recent work focuses on social conservatives’ opposition to the liberalization of gender and sexuality values (Akkerman, Reference Akkerman2015; Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016; Corredor, Reference Corredor2019; de Abreu Maia et al., Reference de Abreu Maia, Chiu and Desposato2020; Kao et al., Reference Kao, Lust, Shalaby and Weiss2023; Kováts, Reference Kováts, Köttig, Bitzan and Petö2017; Kuhar & Paternotte, Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2018). Overall, as the above quotes imply, gender equality and immigration are often framed as cultural ‘threats’ in efforts central to social conservatives’ mobilization of cultural backlash.

However, there is a lack of research on the triggers of cultural backlash (Alter & Zürn, Reference Alter and Zürn2019), which also remains undertheorized in cultural backlash theory (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), calling for experimental studies on backlash. Contrasting observational studies on cultural backlash, existing experimental studies find no evidence of backlash against issues including gay rights and immigration in the United States (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016, Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2021), LGBT rights in Latin America (de Abreu Maia et al., Reference de Abreu Maia, Chiu and Desposato2020) or women in politics in the MENA region (Kao et al., Reference Kao, Lust, Shalaby and Weiss2023). So far, there is little causal evidence on triggers of cultural backlash, and little experimental work on backlash in European contexts. This study addresses these lacunae by theorizing and operationalizing two potential triggers of backlash, as well as a measure of people's predisposition to react to these triggers, in a cross‐country survey experiment in Europe.

Further, research suggests that while the recent conservative backlash to cultural threats occurs among social conservatives in particular, this, in turn, drives polarization between social liberals and social conservatives over cultural issues (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Polarization is here understood as the increasing divergence in political attitudes between two groups, in this case social liberals and social conservatives. Accordingly, while some degree of polarization of political attitudes is healthy for any democratic society (Dahl, Reference Dahl1989), too much polarization diminishes social trust and weakens respect for democratic norms and compromise, aggravates intolerance toward opposing groups and increases the likelihood for abuses of power and even political violence (Carothers & O'Donohue, Reference Carothers and O'Donohue2019; Somer & McCoy, Reference Somer and McCoy2018). The study of polarization over cultural issues between social liberals and social conservatives is thus important for understanding ongoing changes in political systems with potential consequences for democratic governance. However, research has mostly studied polarization in single‐country contexts, often focusing on the United States, given the difficulty of assessing polarization across different political party landscapes (Traber et al., Reference Traber, Stoetzer and Burri2022). We address this shortcoming by proposing a measure of polarization across various European countries.

Our study asks to what extent the presence of cultural threats affects backlash among social conservatives and ultimately issue polarization between social liberals and social conservatives. Building on experimental research on the salience of cultural threats as a trigger of backlash (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016, Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2021), our study employs a novel survey experiment. We randomize the presence of two issues often framed as cultural threats, women's rights and refugee immigration, to test and compare their effects on social conservatism, which we conceive of, and operationalize as, support for traditional values. Furthermore, we anticipate that those with a priori conservative values are more likely to counter‐react to the threats (Feldman & Stenner, Reference Feldman and Stenner1997), which we test by constructing a measure for respondents’ latent social liberal and conservative value predispositions. The survey experiment is embedded in the 2021 European Quality of Government Index (EQI) survey (Charron et al., Reference Charron, Lapuente, Bauhr and Annoni2022), with 129,000 respondents nested in 27 European Union (EU) member states and 208 NUTS2‐level regions. The data allows for large‐n, cross‐country multilevel analyses of the survey experiment and observational survey data.

We find that the women's rights trigger leads to overall lower, rather than higher, support for traditional values. The refugee immigration trigger does not have an overall effect. Thus, we observe no overall backlash to these cultural threats. Second, the threats of women's rights and refugee immigration both provoke polarization between socially liberal and conservative respondents. Liberals and conservatives equally drive polarization in reaction to the refugee immigration threat. However, against our expectations, it is exclusively liberals that drive polarization in reaction to the threat of women's rights.

These findings carry several contributions and implications for future research. First, in line with recent studies (Guess & Coppock, Reference Guess and Coppock2020), future research on backlash should distinguish individuals by their predisposition to backlash, rather than studying the population as a whole. Further, while much previous research focuses on social conservatism, there is a lack of research on social liberalism. Our findings suggest that social conservatives’ backlash should be studied conjointly with social liberals’ counter‐reactions to backlash, which can contribute to polarization and potentially fuel further conservative backlash. The absence of social conservative backlash does not necessarily imply the absence of liberal‐conservative polarization, given that social liberals may shift towards increased liberalism. Finally, rather than assuming that different cultural threats evoke similar reactions, future research may investigate why different cultural threats provoke different reactions at the individual level.

The paper is organized as follows. The literature review is two‐pronged. The review focuses, first, on polarization and perceptions of the threats of refugee immigration and women's rights as sources of cultural backlash and, thus, liberal‐conservative polarization. Second, it introduces literature relevant to theorizing the individual profiles of those triggered towards more conservatism when faced with threat statements. The review is followed by our theory of the salience of cultural threats as a trigger of cultural backlash and liberal‐conservative polarization. We then turn to the description of the data and our analytic strategy, and the presentation of our results. We conclude with a discussion of the findings.

Polarization between social liberals and social conservatives

In the past decades, Western democracies have witnessed increasing political polarization between social liberals and social conservatives over cultural issues such as immigration, LGBTQI+ rights and abortion (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2010). Herein, social conservatism can be defined as individuals’ ‘traditional, authoritarian and nationalist’ (TAN) values (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). Social liberalism can in turn be defined as individuals’ ‘green, alternative and libertarian’ (GAL) values (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002) This liberal‐conservative polarization emerged through the ‘silent revolution’ of the New Left since the 1960s (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1971) and the subsequent counter‐reaction of the populist radical right (Ignazi, Reference Ignazi1992). With cultural issues becoming increasingly salient in the political debate, weights shifted from socio‐economic to (cultural) value‐based dimensions of political conflict (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2010). The recent rise of populist radical right parties (hereafter: PRRPs) has been explained by cultural backlash, defined as social conservatives’ counter‐reaction to the increasing dispersion of social liberal values including multiculturalism, feminism and environmentalism (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). As social liberalism and conservatism are both rising, and this dimension of political conflict becomes increasingly important, the study of polarization between social liberals and conservatives is increasingly relevant.

Political polarization can be defined as the grouping of individuals according to some characteristics into a small number of significantly‐sized political ‘clusters’, where members of one cluster are increasingly similar to each other in their political attitudes, and different to the members of other clusters (Esteban & Ray, Reference Esteban and Ray1994). Much research on increasing liberal–conservative polarization focuses on partisan polarization (Abramowitz & Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Bischof & Wagner, Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2015; Fiorina & Abrams, Reference Fiorina and Abrams2008; Iyengar & Westwood, Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Mason, Reference Mason2015; Silva, Reference Silva2018). However, the study of partisan polarization is difficult to apply to comparative cross‐national analyses of different party systems (Traber et al., Reference Traber, Stoetzer and Burri2022), as parties align themselves on varying ideological continuums and the degree of party identification varies considerably (Michelitch & Utych, Reference Michelitch and Utych2018), which is why most previous research focuses on single national contexts. Recent research that systematically compares polarization across various democracies shifts focus from partisan polarization to polarization among more broad‐based ideological groups, typically assessed via the left‐right scale due to data limitations (Dalton, Reference Dalton2021; Torcal & Magalhães, Reference Torcal and Magalhães2022). However, since the left–right scale conflates socio‐economic and cultural understandings of left and right, it is unclear to what extent these studies capture polarization between social liberals and social conservatives.

Given our study's comparative approach and focus on cultural issues, we concentrate on polarization between social conservatives and social liberals instead, defining them by their latent social liberal and conservative predispositions based on their socio‐economic, demographic and political characteristics rather than their partisanship or left–right identification only. Building on Dalton (Reference Dalton2008), we assume a spatial model of parties and voters aligning along one ideological continuum, in this case the social liberal—conservative continuum, where polarization increases as population groups move towards the extremes of this continuum. We thus understand polarization as group divergence (Bramson et al., Reference Bramson, Grim, Singer, Fisher, Berger, Sack and Flocken2016). In line with this definition, Hetherington (Reference Hetherington2009) defines polarization as increasing differences in mean preferences between two population groups, which most likely emerge over political issues, revealing strongly diverging understandings of right and wrong. These include cultural issues such as immigration, LGBTQI+ rights and abortion, which in turn are crucial to social liberals’ and conservatives’ disagreements and therefore serve as exemplary issues to assess societal polarization between them. The understanding of liberal–conservative polarization as divergence between social liberals’ and social conservatives’ values and attitudes on the liberal–conservative ideological continuum, enables us to study and compare this phenomenon across various national contexts and different party systems, thereby addressing the lack of comparative cross‐national studies of polarization along the cultural dimension.

The perceived threats of refugee immigration and women's rights

Regarding polarization along the cultural dimension, research on the US context explores polarization over various cultural issues, including race, gender equality, abortion and gay rights (Abramowitz & Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Fiorina & Abrams, Reference Fiorina and Abrams2008; Garner & Palmer, Reference Garner and Palmer2011; Mason, Reference Mason2015). In contrast, research on polarization in Europe often exclusively focuses on the issues of immigration and European integration (Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2015; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Oosterwaal & Torenvlied, Reference Oosterwaal and Torenvlied2010) and neglects polarization over gender and sexuality issues. However, the ‘(re)politicization’ of gender and sexuality issues over the past decade in European countries (Abou‐Chadi et al., Reference Abou‐Chadi, Breyer and Gessler2021) calls for such research. We address this gap by comparing liberal‐conservative polarization in Europe over refugee immigration and women's rights.

Cultural backlash theory (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019) and the antifeminism literature (Kuhar & Paternotte, Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2018) suggest that both types of cultural issues, refugee immigration and women's rights, can be perceived as cultural threats to the status quo and predominant power structures and thus provoke conservative backlash (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016). In contrast, social liberals are known to advocate in favour of these issues and may do so even more strongly when facing conservative backlash, leading to what Dalton (Reference Dalton2008, 903) describes as ‘centrifugal forces’ pushing both groups towards their respective value extremes on the liberal–conservative continuum. These dynamics may result in liberal–conservative polarization triggered by the perceived cultural threats of refugee immigration and women's rights.

Research on the cultural threat of immigration in particular suggests that social conservatives counter‐react to the perceived threat of immigration and appeal to immigrants as a cultural outgroup and threat to the traditional cultural values they aim to preserve (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). This resonates with studies finding that cultural threat perceptions are key to understanding anti‐immigration attitudes (Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2005; Schneider, Reference Schneider2008). However, challenging the consensus in cultural backlash research, Bishin et al. (Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2021) do not find causal evidence for a backlash against immigration in the United States.

Similarly, social conservatives can perceive a threat of gender equality and sexual freedoms that may fuel backlash to liberal views on these issues. Research shows that social conservatives tend to oppose the liberalization of gender values (Klasen, Reference Klasen2020). Feminists and members of the LGBTQI+ community are frequently mentioned as outgroups which social conservatives seek to exclude in their quest to preserve predominant power structures (Alter & Zürn, Reference Alter and Zürn2019; Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016; Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Furthermore, burgeoning research identifies a transnational anti‐gender movement opposing advances in gender equality and sexual freedom (Chappell, Reference Chappell2006; Corredor, Reference Corredor2019; Kováts, Reference Kováts, Köttig, Bitzan and Petö2017; Kuhar & Paternotte, Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2018; Towns, Reference Towns, Phillips and Reus‐Smit2020). Conservatives may thus perceive advances in women's rights as a threat to traditional values and power structures in society, and counter‐react to this threat by adapting more extreme conservative views than they would in the absence of such a perceived threat. However, contrasting this hypothesis, existing experimental studies do not find causal evidence for gender and sexuality issues triggering backlash in the United States, Latin America and the MENA region (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016; de Abreu Maia et al., Reference de Abreu Maia, Chiu and Desposato2020; Kao et al., Reference Kao, Lust, Shalaby and Weiss2023).

While the above literature shows that (refugee) immigration and women's rights may both be perceived as cultural threats, recent research suggests that they represent different types of cultural threats. Pless et al. (Reference Pless, Tromp and Houtman2020, Reference Pless, Tromp and Houtman2021) distinguish between religious and secular cultural value divides, distinguishing between traditionalist and authoritarian conservatives. In this distinction, traditionalist conservatives advocate traditional gender, sexuality and family values based on religious motivations, and authoritarian conservatives favour law and order and oppose immigration based on a secular understanding of conservatism. As de Koster and van der Waal (Reference de Koster and van der Waal2007) argue, these two dimensions of social conservatism are often merged because of their common opponent of social liberalism. However, the authors argue that even though social liberals oppose both traditional and authoritarian conservatives, the two types of conservatism are distinct. Depending on whether social conservatives adapt a religious or secular understanding of conservatism, they may therefore differently perceive the cultural threats of refugee immigration and women's rights. By studying both cultural threats in a way that allows for a direct comparison between their effects of polarization, we contribute to this debate.

Who is triggered by these cultural threats?

Most studies on cultural backlash focus on the overall population or only on conservatives’ reactions to cultural threats (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016), with most of the attention related to arguments on either the threat of status loss or the notion of feeling left‐behind. While the former suggests that those who are threatened by status loss, and therefore have an interest in preserving the status quo, are most likely to conservatively counter‐react (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016; Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017), the latter argument forwards the idea that those who feel economically or socially left‐behind in societal changes, such as globalization and modernization, aim to reverse to a previous status quo and are therefore most likely to conservatively backlash (Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow2018). In contrast, there is a lack of research explaining how social liberals react to conservative portrayals of liberal social value change as threatening.

Regarding demographic factors, cultural backlash theory predicts that older generations are most likely to feel left‐behind and thus develop social conservative values, because their realities conflict the most with present society (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). It is moreover expected that men are more likely to be conservatively triggered than women. Given their historically dominant position in societal power structures, they may fear to lose due to societal changes. Indeed, men may feel more conservatively triggered by cultural threats than women, particularly by those related to progress in gender equality, if they entail constraints on men's social status (Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Klasen, Reference Klasen2020). Finally, cultural backlash theory considers urbanization an important driver of liberal value changes because urban areas tend to have more diverse populations leading to more social liberalism and rural residents may increasingly feel left‐behind in the process of urbanization (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow2018), thus resulting in political polarization between rural and urban populations (Scala & Johnson, Reference Scala and Johnson2017).

With respect to socio‐economic factors, Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019) theorize that individuals with university education are less likely to be conservatively triggered, as universities are usually located in rather diverse, urban areas, and university education goes hand in hand with higher incomes, job security and a higher socioeconomic status. These in turn decrease the threat of loss of social status and therefore the likelihood of being conservatively triggered by societal changes towards more immigration and gender equality (Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Golder, Reference Golder2016). Further, Surridge (Reference Surridge2016) finds that a socialization effect explains the positive relationship between education and social liberalism.

Taken as a whole, the literature offers robust insights into the nexus of demographic and socio‐economic factors that predispose individuals to social conservatism or social liberalism. In our empirical analysis, we draw on these insights in our conceptualization and measurement of individuals’ socially liberal and conservative value predispositions.

Theory and hypotheses

Salience of cultural threats as a trigger of polarization

We theorize that the salience of cultural threats leads to backlash and, in turn, triggers polarization. According to Bishin et al. (Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016, p. 627), ‘any actor or action that is sufficiently salient and challenges the status quo may cause backlash’ and issue salience ‘serves to galvanize negative predispositions into negative opinion by heightening the sense of threat, loss, or change to the status quo among social groups’. A potential change to the status quo can thus constitute a threat to supporters of the status quo, triggering conservative backlash, particularly among those who hold a priori conservative values (Feldman & Stenner, Reference Feldman and Stenner1997). Conversely, liberals may anticipate a conservative backlash and counter‐react to the conservative portrayal of cultural value change as a threat, leading to the above‐explained ‘centrifugal forces’ pushing conservatives and liberals towards their respective value extremes (Dalton, Reference Dalton2008, p. 903). Bischof and Wagner (Reference Bischof and Wagner2019) show that social liberals counter‐react against the legitimization of radical views and take more extreme liberal stances in reaction to radical positions they disapprove of. As a result, an increased salience of cultural threats may trigger both social conservatives to the cultural right and social liberals to the cultural left, resulting in increased polarization between them. Otteni and Weisskircher's (Reference Otteni and Weisskircher2022) findings support this theory: the authors show that, by raising the salience of environmentalism, the construction of wind turbines in Germany fuels support for both the radical right and the Green party.

As we consider both refugee immigration and advances in women's rights as potential cultural threats to the status quo, we expect liberal–conservative polarization in response to these threats. When primed with these cultural threats, social conservatives are expected to show stronger support for traditional values, while social liberals should indicate weaker support for traditional values. Individuals exposed to these threats are thus expected to polarize based on their value predispositions, compared to individuals with comparable value predispositions who are not exposed to these threats. To be more specific, individuals who differ in latent social liberal versus social conservative value predispositions based on their socio‐economic, demographic and political characteristics, will polarize in showing more or less support for traditional values when exposed to cultural threat descriptions.

H1: Presenting the threat of increased refugee immigration triggers polarization in support for traditional values between individuals with social conservative and social liberal predispositions.

H2: Presenting the threat of advances in women's rights triggers polarization in support for traditional values between individuals with social conservative and social liberal predispositions.

The survey experiment

To investigate these hypotheses, we use 2021 survey data from the European Quality of Government Index (EQI) survey (see Charron et al., Reference Charron, Dijkstra and Lapuente2014) with a sample of 129,000 respondents across 27 European Union member states (Charron et al., Reference Charron, Lapuente, Bauhr and Annoni2022). The data was collected during autumn and winter 2020/21 at the NUTS2 regional level, comprising 208 regions.Footnote 3 Thus, the survey was fielded during the Covid‐19 pandemic while most countries were on lockdown and neither refugee immigration nor women's rights were particularly salient in the public debate, providing a context that allows for activating increases in individual‐level salience of cultural threats. More on the sample, survey and administration can be found in the Supporting Information Appendix 1.Footnote 4

To test the two hypotheses, we manipulate cultural threat salience. To do so, we elect to take an experimental approach in this study, which prompts our respondents to think of women's rights and refugee immigration as cultural threats. In our experimental set up, we randomly divide our sample into several mutually exclusive treatment groups and one control group. Our treatments consist of statements on the cultural threats of (1) increased refugee immigration and (2) advances in women's rights, whereby the respondents in the different treatment groups are asked to what extent they agree with one of the statements of threat. The control group receives no question.

Respondents of the first treatment group are asked to express (dis)agreement on a 0–10 scale with the following statement: [Country] should not take in any more refugees, because this threatens our way of life. We base the construction of an alleged threat of refugees on the fact that, at the time of survey fielding, refugee populations were by majority culturally different from European societies and may thus be perceived as a cultural threat more than other immigrant groups. A second treatment group receives a statement regarding the threat that women's rights may pose to men: Advancing women's and girls’ rights has gone too far, because it threatens men's and boys’ opportunities.Footnote 5 We base the alleged threat of constraints on men's and boys’ opportunities on antifeminism research (Kuhar & Paternotte, Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2018), as well as research on the role of status loss in cultural backlash (Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2020). By applying the same sentence structure and using the word ‘threat’ in both treatments, we aim at enhancing the comparability of the treatments.Footnote 6 Finally, the pool of respondents in the control group does not receive either statement, and thus serves as our baseline of comparison for both treatments.Footnote 7

Our experimental design has two benefits. First, we randomize the presence to a given issue (testing the theoretical mechanism of ‘salience’). Balance tests via analysis of variance (ANOVA) show that the treatment and control groups are indistinguishable in terms of demographic factors, such as gender, age, income, education, occupation, population of residence and survey administration. Second, we can capture individuals’ attitudes toward the issue in question via their response to the threat statement. We thus know who finds these issues threatening by the degree to which they agree with these statements rather than just assuming that certain groups (i.e. social conservatives or liberals) will be more or less likely to agree with a given treatment statement.

We anticipate that more socially conservative respondents in the treatment groups express stronger agreement with both treatment questions. To test this, we regress the treatment questions on a battery of covariates from the survey which proxy socio‐economic, demographic and political indicators of a conservative profile. We find strong evidence that several proxies which are known correlates of conservatism, such as gender, urban residence, education, partisanship and political values significantly explain variation in threat response in the anticipated direction (see Supporting Information Appendix section 4)Footnote 8. Respondents’ level of agreement with the treatment questions thus allows us to derive their social liberal/ conservative value predispositions (see section ‘Identifying a valid control group for social liberals and conservatives’).

The dependent variable: Preferences for traditional values

Rather than assessing backlash in attitudes towards a specific issue, our main outcome variable is a broader measure that attempts to capture cultural backlash in an equivalent way across multiple countries. In addition to capturing conservatism across multiple countries, we attempt to design a measure of conservatism that is general enough to capture conservative responses to both refugee immigration and women's rights. As our experimental design relies on a priming technique to induce issue salience, we take a parsimonious approach and measure our outcome via a single‐item measure rather than a battery of questions, which would risk diluting the priming treatment effects. With this aim in mind, we created a question that measures ‘preferences for traditional values’ (what we label heretofore as social conservatism). In line with our definition of social conservatism, respondents are asked to answer to the same outcome question, which asks for (dis)agreement on a 0–10 scale with the following statement: We would be better off if we went back to living according to [Country]’s traditional values. The question directly follows the treatment items on the survey. Thus, our experiment relies on a post‐test only design.Footnote 9 We equate disagreement with the statement with social liberal values and agreement with social conservative values.Footnote 10 Although no question exists in this wording on another cross‐national survey (to our knowledge), we find that the country level means on our dependent variable are significantly related with mean levels of left–right self‐placement on the latest European Social Survey (2018, see Supporting Information Appendix 3).

As previous experimental studies on the effect of cultural threats on backlash or polarization use single country samples (e.g., Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016), the literature does not have an established precedent for testing our hypotheses across multiple countries. Thus, to provide a comparable link between the two treatments and the outcome question, and to cover the diverse contexts of countries in our sample in which social conservatism may imply different attitudes on specific issues, we adapt a rather general interpretation of social conservatism. We approximate social conservatism through a backward orientation towards traditional values without specifying what exactly these values entail. The phrase ‘went back’ in the question serves as a proxy for ‘backlash’. While we leave room for context‐specific interpretations of our measurement, it should capture a key element of social conservatism across all contexts, which is the backward orientation towards traditional values (e.g., prior to changes in women's rights and refugee immigration).Footnote 11 Disagreement with the statement that ‘we would be better off if we went back to living according to [Country's] traditional values’ should in turn capture a key element of social liberalism across all contexts, which is the rejection of traditional values in favour of alternative values.

A potential drawback of this design is that we cannot assess the effects of cultural threats over time. Our inferences on the effects of cultural threats on liberal‐conservative polarization thus rely on comparing support for traditional values between people with liberal and conservative predispositions in the treatment and control groups. As our experiment is conducted across 208 regions in 27 EU member states, we elect to estimate the effects via hierarchical models with random intercepts at the regional level.Footnote 12

Identifying a valid control group for social liberals and conservatives

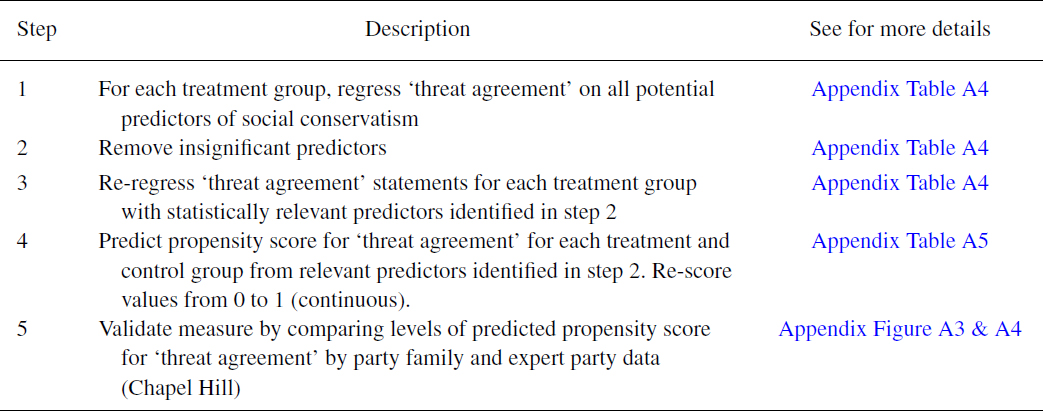

While partisanship is generally used as a proxy of latent liberalism/conservatism in single country studies with which to compare treatment effects (e.g., see Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016), our multicountry context does not allow for this approach due to clear ideological differences across countries in party systems. Moreover, this limits the study to comparing partisans only. Thus, our next challenge is to identify a suitable counterfactual in the control group of respondents with the same latent value predispositions in the treatment groups. We aim to compare the support in traditional values of respondents with the same value predispositions in the treatment and control groups to test H1 and H2.Footnote 13 To do so, we take advantage of the information received from each of the treatment group respondents’ answers to the threat questions. We use this information to generate a proxy for latent social liberalism/conservatism on each issue, women's rights and refugees. Table 1 highlights a summary of the steps taken to calculate our measure.

Table 1. Steps to generate measure of latent liberalism/ conservatism

Our approach to calculating latent social liberal/conservative value predispositions for the control cases is akin to that of calculating a propensity score in matching designs.Footnote 14 Essentially, we regress the treatment groups’ responses on the threat questions on a host of socio‐economic and demographic factors and political values that are related to social conservatism, motivated by the social conservatism literature. We then arrive at a final model for each treatment via the data‐driven Lasso method of model selection to avoid extraneous predictors.Footnote 15 From these models on agreement with statements describing women's rights and refugee immigration as threats, we calculate the predicted level of agreeing with the threat statements on a single dimension from each regression model with all recommended covariates (i.e., resulting in two propensity scores of conservatism, one for each treatment) (see Table A4 in Supporting Information Appendix 4 for full results).Footnote 16 We then extrapolate the predicted level of agreeing with the threat statements of respondents in the treatment groups to respondents in the control group with the same profile based on the above‐used covariates, that is, the same latent social liberal/conservative value predispositions.Footnote 17 The resulting variable of agreeing with the threat statements codes everyone in the sample from 0 to 1 and allows us to compare treatment and control cases across the continuum of latent social liberal/conservative value predispositions.Footnote 18 As we anticipate that these two distinct issues might trigger different types of conservative poles (Pless et al., Reference Pless, Tromp and Houtman2020; Stenner, Reference Stenner2009), our approach allows our measure of conservative propensity to vary by treatment group more precisely.Footnote 19 We validate these measures of ‘predicted threat agreement’ by comparing their levels across political party families and the UNC Chapel Hill expert party data (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022) for the GAL‐TAN measure and find strong evidence that our measures capture latent social liberal/conservative value predispositions (Supporting Information Appendix 4, Figures A3 and A4).

Empirical results

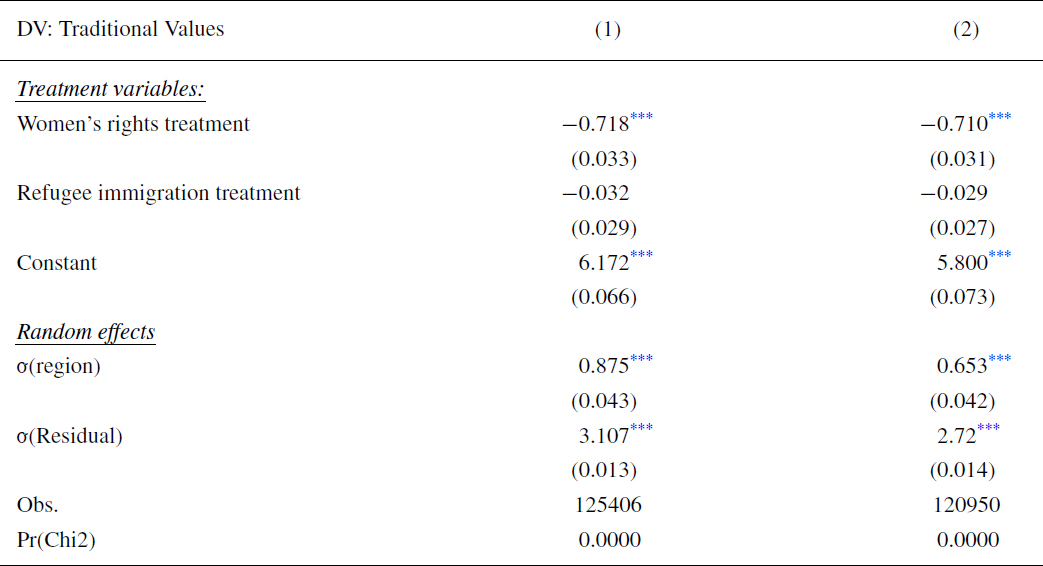

We begin by presenting the overall treatment effects of our survey experiment, comparing the support for traditional values of the two treatment groups and the control group. In model 1 (Table 2), we report the average treatment effects (ATE's) of our two treatments.Footnote 20 On whole, there is a clear effect of the women's rights treatment. When primed to think about women's rights as a threat, respondents indicate systematically lower support for traditional values compared to the control group. Receiving the women's rights treatment results in a 0.71‐point decrease in support for traditional values, equal to roughly 0.22 standard deviations. In more practical terms, this is slightly greater than the mean distance on the dependent variable between centre‐left, SDP (4.60) and centre‐right CDU (5.21) supporters in Germany, or Social Democrats (4.87) and centre‐right Venstre supporters (5.44) in Denmark. In comparison, raising the issue of increased refugee immigration has no significant overall effect on social conservatism compared to the control group. In sum, we observe a decline in social conservatism in response to our women's rights treatment and no change in social conservatism in response to our refugee immigration treatment.

Table 2. Average treatment effect of treatments and observational covariates on social conservatism

Note: coefficients estimated from hierarchical estimation with regional‐level random intercepts and clustered standard errors (in parentheses). Post‐stratification (gender, age, education and partisan affiliation) and design weights included. Controls included in model 2 (see Appendix 5 for full results).

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1

In model 2 (Table 2) we add observational correlates to demonstrate validity for the dependent variable and to test their relative impact on social conservatism. Our findings are comprehensively in line with our expectations (see Supporting Information Appendix Table A8 for full results). Older people tend to express more conservativism, as do lower educated, lower income and more rural residents, other things being equal. In terms of political attitudes and partisanship, the results provide strong validity for our measure. Those opposing immigration and supporting gay marriage express more (less) conservatism respectively, while the partisan leanings are in line with our expectations.

Testing heterogeneous treatment effects among sub‐samples: Experimental results

Moving to hypotheses 1 and 2 on liberal–conservative polarization over support for traditional values, we anticipate that people with different value predispositions respond to the treatments differently, which is well‐established in the literature (Guess & Coppock, Reference Guess and Coppock2020). The essence of the hypotheses is that some are more supportive of the treatment statement (i.e., agree that the issue is in fact a threat), while others disagree, which we argue will be the catalyst for more polarized responses to our dependent variable.

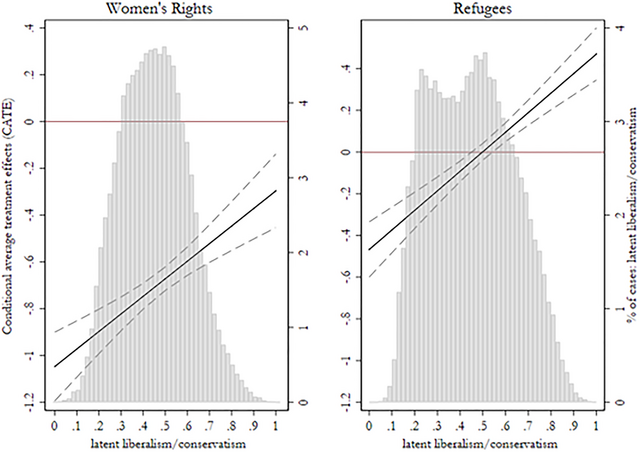

Using our measure of social liberal–conservative value predispositions from the treatment questions (see Supporting Information Appendix section 4 for more details), we proceed to estimate the conditional average treatment effects (CATE), with treatment effects being conditional on a respondent's value predisposition, that is, a respondent's probability to agree with the threat statement.

To estimate the CATE for each treatment group, we run separate models with an interaction between our measure of liberal/conservative value predispositions and the respective treatment dummy. We take each treatment group along with the control group one at a time to isolate the conditional treatment effects of each treatment (women's rights and refugee immigration). Thus, each estimated sample contains roughly 62,000 respondents, with an equal number in the control and each respective treatment groups. We run baseline random effects regional‐intercept, hierarchical models with the main variables only as well as additional models that include all demographic control variables and test models with and without country‐level fixed effects to account for possible endogeneity resulting from omitted variable bias.Footnote 21

Figure 1 highlights the main findings for both treatments. The line represents the CATE across the proxy for liberal/conservative value predispositions (i.e., the moderating variable). On the left side, we see the CATE of the women's rights treatment across the liberal/conservative moderator. In this case, we find that the women's rights treatment has a uniform negative effect on support for traditional values across the range of liberal/conservative value predispositions. However, the average treatment effect is nearly three times larger among respondents with the most liberal predispositions (−1.05), compared to those with the most conservative predispositions (−0.31). Thus, presenting women's rights as a threat moves all respondents to lower support for traditional values, which demonstrates evidence against a conservative backlash, consistent with findings on LGTBQ rights in other contexts (de Abreu Maia et al., Reference de Abreu Maia, Chiu and Desposato2020). Yet, the difference of the treatment effect between those with the most liberal and the most conservative predispositions is significant (p < 0.001). This provides mixed support for H2 in that social liberals react even more strongly than conservatives.

Figure 1. Average treatment effects conditioned by liberal/conservative value predispositions. Note: CATE reported in lines with 95 per cent confidence intervals. The zero line represents respondents in the control group, set to zero to facilitate the comparison. The x‐axis represents a scale of probability to agree with the threat statement (0–1), which proxies liberal/conservative value predispositions. Each model controls for survey administration type and is estimated via hierarchical random regional‐level slopes. Histograms show the distribution of the value predisposition variables for the women's rights and refugee immigration treatments respectively. Post‐stratification and design weights are used, and standard errors are robust. Full results can be found in the Supporting Information Appendix 5.

With respect to the refugee immigration treatment (right side), we find that the treatment effects are highly conditional on respondents’ value predispositions. On the one hand, among those with the most liberal value predisposition, we observe that the treatment has a negative effect on support for traditional values (−0.49). On the other hand, the CATE is positive and significant among those with the most conservative value predisposition (0.48). The gap in the dependent variable between extreme liberals and conservatives is 0.84 greater for the treatment cases compared to the control group; or equivalent to the distance between a typical centre‐left Social Democratic supporter and centre‐right People's Party supporter, such as in Austria (SPÖ = 5.20 versus ÖVP = 6.29). Thus, the refugee immigration treatment produces clear value polarization between individuals with liberal and conservative value predispositions, which lends support to H1.Footnote 22

How robust are the findings across contexts and alternative measures of latent conservatism?

Although Figure 1 provides evidence for the main hypotheses, our sample contains respondents from a diverse group of countries and regions across Europe that have different experiences and histories with gender equality and refugee immigration. To mitigate concerns that our findings are not generalizable but driven by a select group of regions/countries, we provide several checks in Supporting Information Appendix 6. First, we check whether our hypotheses hold across varying levels of socio‐economic development, as proxied by the latest data from the Human Development Index (HDI)Footnote 23 at the regional level. Second, we re‐run the results dividing the sample by geographic region – North/Western Europe, Southern Europe and Eastern/Central Europe. Both broad contextual factors are expected to account for potentially different cultural understandings and reactions to the threats introduced to the respondents. If the treatment effects and/or interactions differ significantly across these various groups, then this would lead to concerns about heterogeneity of the effects’ context dependence of our findings.

In sum, these analyses show that while preferences for traditional values are higher in regions with lower levels of socio‐economic development and Eastern/Central Europe broadly, the treatment effects and interactions found in the main analyses are strikingly consistent across levels of socio‐economic development and geographic areas of the EU (see Supporting Information Tables A10‐A12). Only in one case – the polarization effect of the women's rights threat in North/Western EU versus Eastern/Central EU do we find that the interaction differs at the 90 per cent level of confidence (p = 0.09). Yet, the interaction of the treatment and latent liberalism/conservatism variables is in the same direction and significant in both groups (albeit larger in the Eastern/Central EU group). We infer from these analyses that our main findings are generalizable across the European regions, and not subject to country/regional dependence.

Finally, we provide a replication of the tests of H2 with alternative measures of latent conservatism. In lieu of our propensity measure, we take single items from the EQI survey to proxy for latent conservatism (attitudes toward same‐sex marriage and immigration more broadly). We find the results to be substantively similar, leading to comparable patterns of polarization as those reported in the main results.

Discussion and conclusion

To what extent does the salience of cultural threats affect backlash and polarization between social liberals and social conservatives? We investigate this question using a unique experimental research design, where we compare the effects of two primed cultural threats (women's rights and refugee immigration) on support for traditional values in ca. 129,000 individuals with different predispositions (social liberals and social conservatives) nested in 208 regions in 27 EU member states.

Our main findings can be summarized as follows. First, on average, the women's rights treatment leads to significantly lower support for traditional values among treated respondents, compared to the control group. There is no significant average effect of the refugee immigration treatment. There is thus no evidence for an overall backlash in response to these cultural threats as measured by preferences to ‘go back’ to more traditional values.

Second, we find evidence of increased value polarization between predisposed socially liberal and conservative respondents when those respondents are primed with the salience of the women's rights and refugee threats. In the case of the refugee immigration treatment, those with a social conservative predisposition support higher levels of traditional values when prompted with the refugee immigration treatment. Conversely, those with a social liberal predisposition indicate less support for traditional values after being prompted with the refugee immigration treatment, which together results in greater polarization between social conservatives and liberals. This supports our first hypothesis. With respect to conditional effects of the women's rights treatment, we find that treated social liberals express significantly lower support for traditional values, while treated social conservatives do so to a much lesser extent. However, among both liberals and conservatives, we find that priming the presence of women's rights as a cultural threat leads to less support for traditional values, which contradicts our expectations based on cultural backlash theory. Thus, while we do find support for our second hypothesis that the women's rights treatment provokes polarization between social liberals and social conservatives, this polarization is solely driven by liberals.

Our findings contribute to ongoing academic debates in at least three ways. First, previous experimental studies do not show evidence for a backlash in response to a salient cultural threat (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016). Our study supports their findings for a much wider scope of countries and for additional cultural threats. However, in line with the work of Feldman and Stenner (Reference Feldman and Stenner1997), our interaction term demonstrates a backlash among those respondents with a conservative predisposition when primed with the cultural threat of refugee immigration. The lack of overall backlash in response to the cultural threat perception of refugee immigration is explained by the simultaneous counter‐reaction of social liberals who express less conservatism in response to the treatment. Our findings thus underline that the study of backlash should distinguish individuals by their predisposition to backlash, rather than studying the population as a whole. Failing to distinguish between social liberals and conservatives may conceal polarization and lead to wrong conclusions about the absence of backlash.

Second, previous research on backlash focuses on increased conservatism in response to cultural threats. However, our finding that social liberals drive polarization implies that polarization may occur even in absence of conservative backlash. Based on this finding, we propose that social conservatives’ backlash should not only be investigated in isolation but also be studied conjointly with social liberals’ counter‐reactions to backlash for a more complete picture of value polarization along the social liberal‐conservative ideological continuum. While there is some previous research on liberals’ conservatism in reaction to existential threats (e.g. Nail et al., Reference Nail, McGregor, Drinkwater, Steele and Thompson2009), to our knowledge, liberals’ counter‐mobilization to conservative perceptions of cultural threats remains understudied. Future research on polarization and cultural backlash may consider social liberals’ and conservatives’ dynamic counter‐reactions to each other to better understand these phenomena. Further, the finding that liberals react more strongly to the women's rights treatment than to the refugee immigration treatment deserves further attention. This finding may be explained by the more reactionary framing of the women's rights threat; however, it may as well hint at differences in the nature of the two portrayed cultural threats.

Third, previous research mostly studies single cultural threats in isolation and cannot compare different cultural threats. Our innovative research design incorporates the cultural threats of women's rights and refugee immigration and presents a novel methodological approach to measuring value predispositions across diverse polities, where using partisanship is more problematic. While our findings reveal no overall evidence for backlash against women's rights at the individual level, we do find evidence for backlash against refugee immigration. The fact that we do not find a backlash, even among conservatives, to women's rights is in line with previous research finding that both liberals and conservatives are becoming more progressive in their attitudes towards gender and sexuality across Europe, albeit at different paces (Baldassarri & Park, Reference Baldassarri and Park2020).

In line with Pless et al. (Reference Pless, Tromp and Houtman2020), we thus propose that cultural threat perceptions may comprise religious and secular dimensions that provoke different reactions at the individual level. Conservative backlash against refugee immigration is motivated by a secular understanding of conservatism based on nationalism and authoritarianism. In contrast, opposition to women's rights may stem from a religiously‐motivated conservatism, as suggested by the strong involvement of the Catholic Church in the transnational antifeminist movement (Kuhar & Paternotte, Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2018). Based on this distinction, our findings may suggest that the current social conservative backlash in Europe is based on a rather secular understanding of conservatism. Then again, as suggested by de Koster and van der Waal (Reference de Koster and van der Waal2007), social liberals counter‐react to both secular and religious expressions of social conservatism. Future research should thus distinguish between secular and religious cultural threats, and investigate the influence of religiosity at the individual and contextual levels on how these threats are perceived by social conservatives and social liberals. However, while the finding that individuals react differently to refugee immigration and women's rights may be explained by the above‐outlined explanations in the literature, it may as well hint at potential problems stemming from the identification of two different groups of social conservatives, or the comparison of two threats that are differently salient in the public debate.

Finally, our study is subject to some limitations. Our cross‐sectional research design relies on a snap‐shot of threat‐salience, as expressed in one sentence only. It does not capture the long‐standing more specific types of cultural threats that might play out in a country's media over a sustained period of time (for example, the #MeToo campaign), which in turn gets politicized by partisan elites, who serve as cultural cues to the public. A previous study has, for instance, used a vignette experiment to address this limitation in the portrayal of threats posed by immigrants (Sirin et al., Reference Sirin, Villalobos and Valentino2016). Further, our dependent variable relies on a single item measure and thus likely misses certain aspects of the underlying concept of traditional conservatism. Finally, while we theoretically explain our findings by the increased salience of cultural threats, further research is needed to test the effect of politicization of cultural threats over time, independent of their salience, on polarization between liberals and conservatives.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank participants of the 10th Laboratory for Comparative Social Research International Workshop, members of the GEPOP research group at Gothenburg University, participants of the 2021 IPSA and NOPSA conferences, Olle Folke, Hanspeter Kriesi, Violetta Korsunova and the three anonymous reviewers along with the EJPR editors for valuable comments. Charron acknowledges partial funding by RJ sabbatical (SAB20‐0064), Wenner‐Grenstiftelserna (SSv2020‐0004), Vetenskapsrådet (no. 2019‐02636).

Data Availability Statement

Data and replication materials can be found at: https://zenodo.org/records/10555724.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix 2: Summary statistics and further details on survey questions

Appendix 3: Further details of the experiment and main questions

Appendix 4: Covariates of agreement with the threat statements and creating the liberal/ conservative predisposition variable

Appendix 5: Full Results of H1 and H2

Appendix 6: Robustness checks

Additional sources