Men form half the world's population, and far more than half the world's politicians. Despite men's descriptive over-representation within politics, their substantive representation is given very little attention. Both scholarly and public debate has focused almost exclusively on the substantive representation of women. Why has women's representation been painstakingly analysed while men's substantive representation has received no attention? The answer is that concern about the representation of women's interests arose in a context of women's severe descriptive under-representation. If women were not themselves present within politics, was it possible to ensure that their interests were represented? Debates about substantive representation, the intersection between identities and interests, presence and power, have all been driven by the dilemma posed by absence.

It is easily assumed that no such dilemma exists for men. Men enjoy numerical over-representation in almost every legislature in the world, so they have ample opportunity to defend their interests. The large numbers of men in politics should allow for diversity among male representatives, thus avoiding the scenario faced by under-represented groups whereby a small handful of people are tasked with representing their entire group. Men also enjoy privileged status in society as a whole. For all these reasons, there has been almost no research on the substantive representation of men (SRM).

In this article, I argue that the assumptions outlined above are flawed, and that men's substantive representation is an important and legitimate area of study that should not be overlooked. The assumption that all men are present in politics is false; politics is dominated by a subset of men drawn disproportionately from the most socially privileged groups. These men (referred to hereafter as ‘dominant’ men) typically perform and embody hegemonic masculinity. Many men belonging to marginalized and/or subordinated masculinities remain under-represented, including ethnic minority men, queerFootnote 1 men, disabled men, and men from less privileged social backgrounds (collectively referred to hereafter as ‘disadvantaged’ men) (Bjarnegård & Murray, Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018; Connell, Reference Connell2005).

Just as the assumption of men's descriptive representation does not stand up to scrutiny, nor does the assumption that men enjoy satisfactory substantive representation. The over-representation of dominant men disrupts SRM in at least four ways. First, the descriptive under-representation of disadvantaged men means that, like women, these men experience the dilemma posed by absence: they do not have sufficient representatives to defend and articulate their interests. Second, the assumption that disadvantaged men are represented as men by their more privileged male counterparts belies the fact that men's experience of genderFootnote 2 varies intersectionally, just as is the case for women. For example, gendered norms, roles, performances and power hierarchies vary according to race, social class and so on (Hooks, Reference Hooks2004). If we recognize that men, like women, are gendered subjects, and that gender intersects with other identities to create complex combinations of privilege and disadvantage, then we see that the gendered interests of the most privileged men are not always the same as those of disadvantaged men. Hence, disadvantaged men have gendered interests that are not represented substantively. This is compounded by the third problem: the dominance of hegemonic masculinity within legislatures creates cultures that are exclusionary not only of women but also of many men, and dominant men maintain their hegemonic status by silencing the voices of others, including women and disadvantaged men (Dovi, Reference Dovi2020). Finally, the numerical over-representation of men, and the status of men as the ‘norm’, leads to complacency regarding SRM; the gendered interests of disadvantaged men remain largely overlooked both by scholars and politicians.

This article makes the normative case for studying SRM, and then outlines how to develop this research agenda. It addresses a significant gap in studies of representation, demonstrating how the elite male dominance of politics is problematic not only for women but also for many men. The article brings interdisciplinary insights to the study of representation, situating gender within a broader context of privilege and marginalization. In particular, it draws on studies of masculinities to extend feminist scholarship on representation. As such, it makes an important contribution to scholarship within and beyond political science.

Expanding the study of substantive representation to include men does not undermine the important focus on women; indeed, it provides a useful, arguably necessary, complement to such work. Knuttila (Reference Knuttila2016) argues that the ‘patriarchal dividend’ comes at a cost for women and men, while the benefits are very unevenly distributed. The perception that all men are equally advantaged by their gender and the failure to recognize men as gendered subjects can reinforce the marginalization of disadvantaged men. Challenging the dominance of the most privileged men offers a more inclusive model of men's representation while also breaking down some of the barriers that women face. This approach is compatible with Celis and Childs’ (Reference Celis and Childs2020) work on feminist democratic representation, which argues that all voices and perspectives need to be heard within the democratic process, including those of the most marginalized.

This article begins by illuminating deficiencies in men's descriptive representation and demonstrating how dominant men are heavily over-represented at the expense of disadvantaged men, using the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK) as illustrations.Footnote 3 I then explain how power structures among men also undermine SRM, with some men enjoying decidedly more privilege than others. I explore the importance and relevance of intersectionality to the study of men, and draw on Connell's work on masculinities to demonstrate how intersectionality contributes to male gender hierarchies. Not only are some men less present than others, but those who are present are not motivated to speak on behalf of their less privileged counterparts; indeed, dominant men maintain their status by marginalizing and subordinating other groups, including women and disadvantaged men. Cultures of hegemonic masculinity within politics exacerbate the problem and stifle discussion of male vulnerability.

Having argued that men have distinct representational needs, I then consider how we might measure them. I begin by engaging with existing scholarship on substantive representation, building on insights from this literature and suggesting how to expand this work to be more inclusive of men. I then develop a framework for studying men's interests, drawing on both objectivist and constructionist approaches to capture the intersectional nature of men's interests and the ways in which the needs of dominant men prevail over those of disadvantaged men. I illustrate the argument with several examples, including an extended example looking at male educational under-attainment in the UK. I conclude by considering the broad scope for future research in this area, given the wide gap in our knowledge on men's gendered representation; this article is an important first step towards filling that gap.

Why numerical over-representation is not sufficient: gaps in descriptive representation

Gender and politics scholars note that women's presence in politics is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition of representation: it also matters which women (Celis & Childs, Reference Celis and Childs2020; Smooth, Reference Smooth2011). While it should be obvious that it also matters which men, this question remains overlooked (Childs & Hughes, Reference Childs and Hughes2018). Men enjoy numerical dominance in most legislatures; the global average is 73.4 per cent men (IPU, 2023). When we look at which men, however, we find that privileged men are even more disproportionately over-represented, while some men remain largely absent from politics.

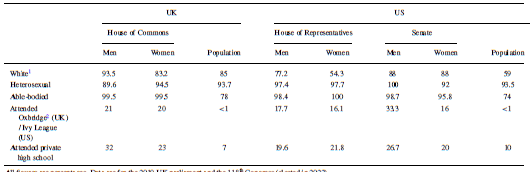

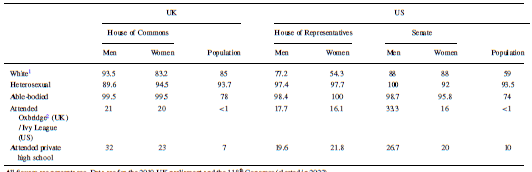

Men dominate the legislatures in both illustrative examples, comprising 66 per cent of the House of CommonsFootnote 4 (UK), 70.7 per cent of the House of Representatives (US), and 75 per cent of the US Senate. Recent increases in the proportion of women have led to expectations of renewal and broader descriptive representation; elsewhere, gender quotas have promoted wider diversity, albeit more for women than men (Barnes & Holman, Reference Barnes and Holman2020; Celis et al., Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damsta2014b). This is reflected in Table 1, where we see that the racial composition of female legislators is broadly commensurate with the population they serve. In striking contrast, the representatives who are male are also overwhelmingly pale; there is a ten-percentage point gap in the proportion of white men and women legislators in the UK, and in the US, which is more racially diverse, the gap is 23 percentage points in the House. (The Senate is predominantly white for both sexes.) While men outnumber women in the House of Commons 2:1, the majority (56.9 per cent) of British MPs of colour are women (Uberoi & Lees, Reference Uberoi and Lees2020).

Table 1. How members of the UK Parliament and US Congress compare to the population

All figures are percentages. Data are for the 2019 UK parliament and the 118th Congress (elected in 2022).

1 White British (UK); white Caucasian/ non-Hispanic white (US).

2 Oxford/ Cambridge University

Sources: CDC, 2020; Congress, 2023; Congressional Research Service, 2023; Cracknell & Tunnicliffe, Reference Cracknell and Tunnicliffe2022; Department for Work & Pensions, 2021; ONS, 2021a; Schaeffer, Reference Schaeffer2023; Sutton Trust, 2019

Lesbian, gay and bisexual people are currently well represented in the House of Commons, although this is a recent development (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2013), and they are under-represented in Congress. Many LGBT MPs come out after election; their initial success may be conditional on adhering to gender norms and performing heterosexuality (Golebiowska, Reference Golebiowska2003). There are very few disabled parliamentarians of either sex, even though about a quarter of the population has some form of disability. Social class is notoriously hard to measure, although Carnes (Reference Carnes2018) and O'Grady (Reference O'Grady2019) note the severe under-representation of working-class people in politics. Politicians are far more highly educated than the wider population (the vast majority of US and UK politicians have degrees – mostly postgraduate for members of Congress), although Erikson and Josefsson (Reference Erikson and Josefsson2019) find this does not increase legislators’ efficacy. Attending fee-paying schools and elite universities demonstrate particular class privilege; Table 1 shows the gulf between politicians and the wider population. In the UK and US Senate, a higher proportion of men come from these privileged backgrounds.

Table 1 demonstrates clearly that numerical dominance does not guarantee descriptive representation; the men in politics are disproportionately white, able-bodied and socially privileged, and less diverse than their female counterparts. Hence, while men as a group are heavily over-represented, this advantage does not carry through to all men; many disadvantaged men also get left behind.

Intersectionality and masculinities: gaps in substantive representation

As with women, men's gender intersects with multiple identities, with power and privilege being unevenly distributed on the basis of other factors such as race and class. Scholars have scrutinized the impact of intersectionality on women who face multiple forms of structural discrimination (Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1991; Smooth, Reference Smooth and Wilson2013; Yuval-Davis, Reference Yuval‐Davis2006). This scholarship deepens our understanding of how gender intersects with other identities to create particular forms of oppression. Work in this area highlights how the women's movement has been dominated by privileged (for example, white, middle-class, heterosexual) women, while other liberation movements have been dominated by men (Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1989). Women belonging to more than one disadvantaged group become lost in the intersection and are multiply marginalized.

It is difficult to conceive of intersectionality in the same sense for men. When gender is understood in binary terms as a social construct that privileges men over women, men do not face marginalization on the basis of their gender. Male dominance in the representation of other identities means that claims made on behalf of (for example) ethnic minority or working-class groups are often based on the needs and interests of ethnic minority or working-class men (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Beall and Holman2021; Collins, Reference Collins2000). Consequently, scholarship on intersectionality within political representation has largely excluded men, even though scholarship on masculinities has emphasized the importance of intersectionality (Childs & Hughes, Reference Childs and Hughes2018; Christensen & Jensen, Reference Christensen and Jensen2014).

Feminist work on intersectionality demonstrates how someone can be privileged by one identity while simultaneously marginalized by another; for example, white women enjoy racial privilege while experiencing gender disadvantage (Severs et al., Reference Severs, Celis and Erzeel2016; Smooth, Reference Smooth2011). This creates inequalities among women, as women may be subordinated relative to men within their ethnic or class group, but still enjoy privilege relative to women who experience multiple forms of disadvantage. Consequently, the experiences and voices of more privileged women cannot suffice for achieving women's representation; understanding gender inequality requires the inclusion of the full diversity of women's experiences.

However, there is less recognition that men, too, are gendered subjects (Cheng, Reference Cheng1999). While men may be privileged relative to women, they may be marginalized by other identities in ways that are gendered; the intersection of male gender with other identities shapes power hierarchies among men as well as between men and women (Celis & Mügge, Reference Celis and Mügge2018). Understanding these intersections is crucial for illustrating how, for men too, the experiences and voices of the more privileged cannot suffice for achieving men's representation; diversity of men, as of women, is essential.

The significance of intersectionality for men is best illustrated using Connell's theories of masculinity. Connell distinguishes between four types of masculinity: hegemonic, complicit, subordinated and marginalized (Connell, Reference Connell2005; see also Messerschmidt, Reference Messerschmidt2018, Reference Messerschmidt2019). Connell argues that masculinities are relational; hegemonic masculinity is not defined by universal, absolute qualities, but by its position relative to others. Masculinity is hegemonic when in a position of dominance, both over women and over other forms of masculinity. As Purvis argues, ‘a fuller understanding of the different aspects of masculinities thus illuminates not just the oppression of other genders by men but also the oppression of some groups of men by other men’ (Reference Purvis2019, p. 430).

Within politics, hegemonic masculinity is asserted through cultural and intellectual dominance, favouring the soft power exerted by social elites. Economic privilege, powerful connections, confidence and the ability to influence others are all important markers of status. Masculinities scholarship illuminates how the same privilege that helps certain men to access power also shapes how they wield that power, not only over women but also other men. Men who cannot achieve hegemonic status are subordinated and/or marginalized. This undermines both their descriptive and substantive representation. Even when they are present, disadvantaged men may be less empowered than their dominant peers.

Subordinated masculinities are those that do not conform to social expectations of masculinity. Any man whose gender performance is deemed too feminine will occupy a position of subordination relative to those conforming to dominant norms of masculinity (Connell, Reference Connell2005). (This illustrates how patriarchy and homophobia are both used to uphold the valorisation of the masculine over the feminine.) Within gender hierarchies, being an effeminate man can be at least as disempowering as being a woman, with such men being punished both for their femininity and their lack of gender conformity. While Connell focuses primarily on homosexuality, there are other ways in which men may struggle to conform to ideal types of masculinity, including when their physical strength is limited due to age, illness and/or disability. While physical frailty is distinct from an effeminate presentation, it can still be emasculating (King et al., Reference King, Shields, Shakespeare, Millner and Kavanagh2019).

Unlike subordinated masculinities, which are associated with behaviour, physique and presentation, marginalized masculinities are related to broader social structures. Connell recognizes that race and class are gendered and contribute to the structuring of gender hierarchies. Ethnic majority and wealthy men enjoy elevated status over other men. Men within marginalized groups may conform in their gender presentation to hegemonic ideals of masculinity, such as physical strength, toughness and assertive behaviour. It is not their gender performance as individual men, but rather their reduced social status as members of disadvantaged social groups, that leads to their categorization as marginalized masculinities. Indeed, some working-class and ethnic minority men may adopt ‘protest’ or compensatory masculinities whereby they place greater emphasis on their masculine traits in order to assert themselves within a position of relative inferiority (Messerschmidt, Reference Messerschmidt2019). These men's emasculated status relative to dominant men can reinforce their desire to gain patriarchal privilege over female members of their group in order to assert some form of power (Cheng, Reference Cheng1999). A similar logic applies to white women who support (chauvinist) white nationalist movements in order to maintain their status advantage over women of colour (Collins, Reference Collins2000). This demonstrates the complexity of power relations within a group that is simultaneously privileged and marginalized, and illuminates the additional disadvantage experienced by multiply marginalized groups.

Members of dominant groups who are neither marginalized nor subordinated might still not achieve hegemonic status. Indeed, most men cannot fully exert hegemonic masculinity, but nonetheless benefit from their status as men, especially when they also belong to other privileged groups. Connell identifies these men as complicit – benefiting from and thus accepting the status quo even if they do not reach the top of the social hierarchy. Such men might have little motivation to act on behalf of subordinated or marginalized men, given that excluding others gives complicit men a status advantage.

Within a political context, certain masculinities might be marginalized without being subordinated. For example, some political parties, especially populist parties and parties on the left, publicly venerate the working classes, yet their politicians come primarily from affluent backgrounds (Carnes, Reference Carnes2018; Heath, Reference Heath2015). This raises important questions about the role of partisanship and ideology, and whether wealthy men can be effective and authentic representatives of working-class men. Meanwhile, other masculinities might be subordinated without being marginalized. For example, older age is definitely not marginalized within a political context – 70 per cent of Senators and 46 per cent of Representatives are aged over 60 (Magan, Reference Magan2021; the UK figure is more proportionate at 19 per cent [Cracknell & Tunnicliffe, Reference Cracknell and Tunnicliffe2022]). However, certain aspects of aging are associated with weakness and vulnerability, which runs counter to masculine norms of strength and power. Older male politicians may not be well placed to represent the interests of older male citizens (specifically those interests pertaining to weakness and aging), despite being numerically well represented, as doing so would draw attention to their own aging bodies and move them squarely from hegemonic to subordinated status. Hence, even when a group is over-represented descriptively, the interests of that group are not necessarily represented substantively.

The performance of certain types of masculinity – including aggression, dominance and emotional suppression – can create distinctive policy problems for men in areas ranging from mental health to criminality or educational outcomes. Yet cultures of hegemonic masculinity can also hinder the substantive representation of men's interests (Murray, Reference Murray2014). Masculinity dominates formal displays of political power, as well as informal practices such as drinking cultures, in many countries around the world (Bjarnegård, Reference Bjarnegård2013; Childs, Reference Childs2004; Grey, Reference Grey2002; LeBlanc, Reference LeBlanc2009). Heckling, jeering and harassment are common practices in many parliaments. These cultures of masculinity are so deeply engrained that they are easily mistaken for the cultures of political institutions themselves. They set the norms of conduct within politics, and voters may expect politicians to adhere to these norms. This can make it very difficult for anyone, male or female, to deviate from masculine norms. Those who cannot conform to hegemonic masculinity risk being sidelined, ridiculed and overruled.

These norms determine both the conduct of politicians and the parameters of political discussion. Hegemonic masculinities subordinate displays of vulnerability or weakness. Within a culture of aggression and heckling, it can be difficult to raise sensitive or embarrassing subjects, and this can hinder SRM in these areas. Ruxton and van der Gaag (Reference Ruxton and van der Gaag2013, p. 16) found this in their research:

[The] former chairperson of the Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality of the European Parliament … argued that: “The expression of feelings is not allowed in this masculine model (‘Men don't cry’). Men are scorned if they are interested in gender equality issues[…].” Interviewees said that traditional masculine attitudes can also make it hard for men to recognize any problems which suggest vulnerability.

LeBlanc illustrates how models of masculinity can hinder the representation of men: ‘if men, because they are men, find it difficult to practice certain kinds of important politics, then … gender expectations repress men's ability to speak for the full diversity of political needs men have’ (Reference LeBlanc2009, p. 43, original emphasis). Those who cannot perform hegemonic masculinity, including women and disadvantaged men, may offer a more inclusive approach (Cooper, Reference Cooper2009; Lindgren et al., Reference Lindgren, Inkinen and Widmalm2009). Hence, greater diversity both within and between the sexes is essential for breaking down dominant cultures of masculinity and opening up the agenda. If these cultures hinder the full representation of men, the paradoxical conclusion is that men may need fewer men representing them in parliament in order to have their interests better met. Cross-national and cross-temporal studies would help to reveal whether more diverse parliaments are better able to acknowledge male vulnerability.

We thus see that disadvantaged men are excluded from politics in two critical ways. They are under-represented descriptively. Their identities and interests are also subordinated and marginalized within the representative process, further hindering their substantive representation. This leaves power concentrated in the hands of multiply privileged men, thus excluding not only women but also most men. On this basis, I have claimed that SRM merits further investigation. The remainder of this article proposes different avenues for exploring men's representation, both theoretically and empirically. It is beyond the scope of this article to offer the answers; rather, I identify the questions we need to be asking.

Revisiting substantive representation

Any attempt to study SRM must start by drawing on insights from existing literature on substantive representation, much of which focuses on women (although the substantive representation of other groups is also studied, including people of colour (Kroeber, Reference Kroeber2018; Lowande et al., Reference Lowande, Ritchie and Lauterbach2019; Sobolewska et al., Reference Sobolewska, McKee and Campbell2018), older people (Chaney, Reference Chaney2013), people with disabilities (Evans, Reference Evans2022) and LGBT people (Bönisch, Reference Bönisch2021; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2013; Saraceno et al., Reference Saraceno, Hansen and Treul2021)). Although very little literature exists on the substantive representation of men's interestsFootnote 5, the insights provided by existing scholarship offer a valuable starting point. Many of the lessons from this literature have application for an intersectional analysis of men's representation, even if no explicit connection is made in the original writings.

One important lesson is that we cannot make universal claims about a single group (Sapiro, Reference Sapiro1981). Assuming that all members of one sex share the same common interest in a way that is distinct from members of the other sex is essentialist and reductionist (Celis et al., Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2014a; Harder, Reference Harder2023; Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999). This is because gender is only one cleavage out of many that define us politically. Our needs, priorities, preferences and experiences of gender all vary according to the intersection of our gender with other traits (Smooth, Reference Smooth2011). While this argument has been made in reference to women, it also holds for men. It then follows that there is no single set of interests that affects all men in the same way; just as definitions of ‘women's interests’ have struggled to acknowledge diversity and avoid essentialism, so any analysis of ‘men's interests’ must acknowledge the heterogeneity of men. If men do not share common interests as men but rather as sub-categories of men, based on the intersection of their gender with other traits, then a large body of homogenous men will not suffice for the full representation of men's interests. The gendered interests of disadvantaged men will be neglected wherever those men are under-represented, no matter how many dominant men hold power.

Another lesson from existing literature is that the interests of some group members may be privileged at the expense of others. Not only are group interests not universal but they may be competing; advancing some interests may hinder the interests of others (Dovi, Reference Dovi2007). This is particularly the case when privileged members of under-represented groups – such as those who are wealthy and/or ethnic majority – are able to define the interests of their group to the exclusion of disadvantaged members of that group (Celis & Mügge, Reference Celis and Mügge2018; Young, Reference Young2000). Those who experience intersectional disadvantage may suffer from ‘secondary marginalization’ (Cohen, Reference Cohen1999, p. 70) due to the appearance of representation of their interests when this is not in fact the case. When applied to men, we see that dominant men are best placed to define men's interests and promote their own preferences as those of their sex (Squires, Reference Squires2008).Footnote 6 Just as men may overlook women's interests (Phillips, Reference Phillips and Phillips1998), so dominant men may disregard disadvantaged men's interests. Or, where the interests of dominant and disadvantaged men are competing, dominant men will prioritize their own preferences at the expense of disadvantaged men. Not only are the needs of disadvantaged men neglected, but this phenomenon remains invisible. Disadvantaged men appear to be represented by other members of their sex, thus obscuring their political marginalization.

The third lesson is that substantive representation bears, at best, an imperfect relationship to descriptive representation. Numerical representation may be less important than the presence of critical actors who are able and willing to advance a cause (Childs & Krook, Reference Childs and Krook2008). Men can be critical actors advancing women's interests (Childs & Krook, Reference Childs and Krook2009), yet there has been no consideration of critical actors (male or female) for men. Male over-representation may reduce the perceived need for, and legitimacy of, mobilisation on behalf of men (see Baxter, Reference Baxter2015; Phillips, Reference Phillips2015), creating a barrier to defending disadvantaged men's interests. Men in power are not expected to demonstrate gender consciousness (Höhmann & Nugent, Reference Höhmann and Nugent2022), enabling privileged men to defend their interests implicitly by presenting them as universal (Bjarnegård & Murray, Reference Bjarnegård and Murray2018). Where men do show gender consciousness, this may consist of backlash against women's empowerment (Krook, Reference Krook2015). Conversely, where cultures of hegemonic masculinity inhibit men from discussing certain issues, women may more easily emerge as critical actors to raise these issues.

Given the lessons above, scholars have developed innovative new approaches. Beckwith (Reference Beckwith2011) distinguishes between ‘interests’ (fundamental to life chances), ‘issues’ (areas on which groups mobilize), and ‘perspectives’ (distinctive approaches to a policy area). Harder (Reference Harder2023) emphasizes the role of ideology over identities and suggests shifting our thinking towards ‘gender equality interests’. Constructivist scholars emphasize the importance of studying representative claims (Saward, Reference Saward2010; Disch, Reference Disch2015). They reject the notion that interests are pre-defined by their group and transmitted unidirectionally to representatives, arguing instead that representatives actively define those they represent ‘as this or that, as requiring this or that, as having this or that set of interests’ (Saward, Reference Saward2010, p. 71). This approach also looks beyond elected representatives and recognizes other actors who make claims (and thus help define interests) on behalf of groups (Squires, Reference Squires2008). Constructivist scholars avoid pre-imposing a definition of interests, and instead listen to the claims actually being made. This approach also enables researchers to capture competing and contradictory claims. One notable critique, however, is that a claims-making approach risks discounting legitimate interests for which claims have not been made – an omission of particular importance when studying disadvantaged groups whose interests may be ignored or suppressed by privileged groups with more resources to make claims (Celis & Mügge, Reference Celis and Mügge2018). Hence, an intersectional approach must assess critically which groups and interests are omitted from these claims and why this matters. I develop these insights below.

Researching men's interests

Researching ‘men's interests’ poses specific challenges alongside those noted above. Most analyses of substantive representation focus on groups who are, collectively, disadvantaged relative to the dominant group. Conversely, studying men requires studying a dominant group, albeit one where levels of privilege vary and are nested within complex hierarchies of domination, subordination and marginalization. Hence, while substantive representation for most groups requires advancing interests that were previously neglected, this is true only for some men, while others’ interests might best be advanced through defending and upholding the status quo. To address these challenges, I advance a new framework for researching and analyzing men's interests, drawing both on objectivist and constructivist approaches.Footnote 7

An objectivist approach involves measuring gender gaps in policy outcomes to identify areas where men have distinctive needs relative to women. Following Beckwith's typology (Reference Beckwith2011), there are numerous policy areas that directly (negatively) affect men's life chances and can thus be defined as men's interests.Footnote 8 These include mental health, crime, life expectancy, homelessness, military service, and educational outcomes. Areas where, due to biology or gendered socialization, men's interests are clearly distinct from, and potentially competing with, women's interests include physical health, paternity, and workplace equality. An intersectional lens is essential; in most (if not all) policy areas, we can expect to see greater advantages for some men and disadvantages for others. A policy area that advantages dominant men while producing unfavourable outcomes for other men illustrates how imbalances in men's descriptive representation can lead to inadequate substantive representation of disadvantaged men's interests. It also illuminates how dominant men have a greater interest than disadvantaged men in upholding the status quo.

The objectivist approach has several merits. First, it can cover the full range of policy areas, recognizing that gaps within and between genders can exist almost anywhere and should not be restricted in scope by the priorities of policymakers or pre-conceptions of scholars. Second, it can consider all groups affected by a policy area, and thus identify the ‘silences’ where claims are not made by or for a group. Third, it can build on the rich resources offered by scholars of men and masculinities. While they are mostly located in other disciplines and do not study political representation, their work sheds crucial light on inequalities, power hierarchies, gender norms and policy outcomes that have much to offer scholars of men's interests.

Complementing this approach, a constructivist approach can focus on the claims made on behalf of men to understand how men's interests are defined, politicized and advanced. This is vital for understanding which men are represented, and to what end. Building on Celis et al. (Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2014a) and Disch (Reference Disch2015), I elaborate four axes that are critical for understanding how men's interests are constituted. First, who is making claims on behalf of men? Second, what ideology shapes these claims? Third, which men are represented by these claims? Fourth, what are the goals of the claims? I unpack each axis below.

We should consider both male and female claimsmakers, within and beyond the parliamentary arena (Childs & Krook, Reference Childs and Krook2009; Saward, Reference Saward2010; Squires, Reference Squires2008). This is particularly useful given that claims by elected politicians may be constrained for the reasons considered above. It is helpful to know how much of the agenda on men's interests is driven by external actors, such as bureaucrats, civil society organizations, academics and public intellectuals, celebrities and NGOs.

The ideology underpinning these claims is key. While classic left-right dimensions are useful, Celis and Childs’ (Reference Celis and Childs2012) critique suggests that a more pertinent measure is the degree of alignment with feminist goals. Claims could be categorized as pro-feminist, non-feminist or anti-feminist. A pro-feminist ideology would frame men's interests within a broader discussion of challenging traditional gender roles and promoting a more egalitarian society. Pro-feminist claims might advance men's interests that are complementary to women's interests, such as support for men as caregivers, or reducing gender-based violence. A non-feminist ideology does not engage with notions of gender equality and focuses exclusively on specific needs for men, viewed as distinct from women's interests. Examples might include claims regarding men's health, or male veterans. Finally, an anti-feminist ideology would reject feminist goals, framing men's interests as competing with women's interests in a zero-sum game where gains for women are at the expense of men (and vice versa). Examples might include redirecting resources from women to men, or requesting parity of treatment for men and women in areas where women experience greater structural disadvantage.

Recognizing which men are targeted by claims is essential for an intersectional understanding of SRM. Inclusive claims consider the needs of a variety of men, including those from less privileged groups, and recognize the need to think intersectionally both when diagnosing a policy problem and proposing a solution. Generic claims consider men as a homogenous group. They do not explicitly favour one group of men, nor recognize differences between men. Narrow claims focus explicitly or implicitly on a subgroup of men.

Finally, the goals of the claims may be to transform or uphold the status quo. Transformative claims can be both pro- or anti-feminist if they seek to change the current levels of male dominance or challenge the existing gender order. Claims seeking to uphold the status quo may be a defensive response to, or act of resistance against, claims made on behalf of women or minoritized men. More rarely, they may be an attempt to protect progressive measures against backlash.

Illustrative examples

While the core contributions of this article are to demonstrate why and how we should study SRM, it is helpful to illuminate the concepts outlined above. To this end, I offer here some (necessarily brief) examples. I use an objectivist approach to demonstrate intersectional differences among men in three policy areas (mental health, criminality and workplace equality). I then combine objectivist and constructivist approaches in an extended example looking at education.

Mental health

In the US 3.7 times more men than women die by suicide, and 3.2 times in the UK (Elflein, Reference Elflein2021; Statista, 2021). Masculinity plays an important role, from the taboo for men of expressing emotions to the trauma of ‘failed masculinity’ caused by divorce or unemployment (Ruxton & van der Gaag, Reference Ruxton and van der Gaag2013). Marginalization contributes to poor mental health in various ways. Deprivation is positively correlated with suicide rates. Black men's mental health needs are distinct to those of black women and other men, triggered by gendered and racialized experiences of discrimination and marginalization, and these men are often unaware of support services or unwilling to acknowledge their needs (COMAB, 2009; Lambeth Council, 2014; Watkins et al., Reference Watkins, Walker and Griffith2010). Young queer men are disproportionately more likely to die by suicide triggered by homophobic bullying (COMAB, 2009). Men with disabilities can also experience poor mental health, fuelled partly by inability to conform to societal expectations of masculinity and the stigma of needing help from others (King et al., Reference King, Shields, Shakespeare, Millner and Kavanagh2019). Hence, mental health highlights the distinct needs of disadvantaged men, especially within a context of stigmatized vulnerability. Within the UK parliament, the specific mental health needs of LGBT men and men of colour were raised by women, demonstrating how women may be more effective at representing the interests of vulnerable men (Hansard HC Deb., November 19, 2020; November 25, 2021; November 17, 2022).

Criminality

Men are both the perpetrators and victims of most violent crime, and the vast majority of prisoners are male. Disabled men and queer men are more likely to be victims of violence, especially when they are additionally marginalized by their race and/or class (Meyer, Reference Meyer2015; ONS, 2021b). Men of colour experience significant bias within the judicial system. In the UK, ethnic minority men are more likely to be stopped and searched by police, and prosecuted and sentenced for violent crime, even though white people are more likely to self-report having committed a crime (COMAB, 2009; Ministry of Justice, 2019). In the US, ‘a black person is five times more likely to be stopped without just cause than a white person’, and ‘a black man is twice as likely to be stopped without just cause than a black woman’ (NAACP, 2021). African Americans are incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of Whites, and African Americans and Hispanics together comprise 56 per cent of prisoners but only 25 per cent of the population. There is a stark gendered dimension; one in a hundred black women has been incarcerated, compared to one in six black men (ibid). Black men are also at disproportionately high risk of being killed by police in the US; men are 20 times more likely than women to be killed by police, and black men are 2.5 times more likely to be killed than white men (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Lee and Esposito2019).

Workplace equality

Dominant men mostly benefit from gender inequality within the workplace, while disadvantaged men face some distinctive gendered challenges, highlighting how gender shapes interests both between men and women and between different groups of men. The construction of masculinities within working environments can be damaging, especially for working-class men (Collinson & Hearn, Reference Collinson, Hearn, Kimmel, Hearn and Connell2005; Hearn & Collinson, Reference Hearn and Collinson2006). The pay gap between disabled and able-bodied employees is significantly wider for men than women, indicating that men pay a heavy price for not conforming to hegemonic masculinity (COMAB, 2009). Occupational segregation occurs along both gender and race lines, and men of colour face distinct challenges; for example, Holder (Reference Holder2017) found that African American men were the worst affected by unemployment following the 2008 recession. Men's interests regarding workplace equality may compete with women's interests; for example, measures to promote women's access to male-dominated professions and positions of power face resistance from men seeking to preserve their privilege. However, measures to support men's greater access to female-dominated professions could benefit both sexes and thus be an example of complementary interests (Allison et al., Reference Allison, Beggan and Clements2004).

Extended example: education

There exists a stark and growing gender gap whereby boys obtain lower educational outcomes than girls within Western nationsFootnote 9 (Stoet & Geary, Reference Stoet and Geary2020). Boys are more likely to leave school without qualifications and less likely to go to university (Belkin, Reference Belkin2021; Hillman & Robinson, Reference Hillman and Robinson2016). However, there is disagreement on the causes of the gender gap, and a lack of successful interventions to erase the gap. Using a constructivist approach, I examine claims made on this issue, then use an objectivist approach to highlight the omissions in these claims.

Claimsmakers regarding male educational under-attainment include the media, think tanks, NGOs and professional bodies. Given space constraints, the focus here is on claims made within parliament, which have arisen primarily from white, male, anti-progressive Conservative MPsFootnote 10. Their claims have focused on under-attainment by white, working-class boys. They claim that these boys are held back by deprivation, and by the refusal to acknowledge gender and racial inequality when white men are not the beneficiaries. The claims highlight the complex intersection of vectors of privilege and oppression, given that white males are typically privileged by their race and gender, even when disadvantaged by their socio-economic status. The claims are also indicative of how dominant men have framed the policy problem in a way that emphasizes certain interests while marginalizing others. I argue these claims are anti-feminist, as they are used instrumentally as backlash against measures promoting gender and racial equality, and narrow, as they focus on a specific subset of men.

Male educational under-attainment has been debated multiple times in parliament. The Education Committee produced a report on the subject in 2014. The report notes advice from experts cautioning against a focus on white working-class children: ‘it ignores huge inequalities in other parts of the system by focusing on this very particular area’ (HoC Education Committee, 2014, p. 12). The Committee were further advised that ‘we should stop talking about “white working-class boys” as if they are the only challenge’ (ibid, p. 21). Yet these emphases persisted in subsequent debates on the issue. A debate on the ‘Educational Performance of Boys’ included contributions from (non-white-male) MPs reiterating the need to broaden the focus of the debate (Hansard HC Deb., September 6, 2016). A subsequent debate on the ‘Education and Attainment of White Working-Class Boys’ in 2020 maintained the narrow focus on this specific group. Only one participant in this debate (Labour MP Seema Malhotra) was not a white man; she was the only participant to encourage a broader scope (Hansard HC Deb., February 12, 2020). In a later debate, the issue was again brought up repeatedly, with Philip Davies lamenting that ‘the politically correct lobby has brushed [this] under the carpet for too long’ (Hansard HC Deb., November 19, 2020).

While an exhaustive examination of political debate on the issue is beyond the scope of this article, there is some indication that narrow representational claims are being advanced by dominant men, and challenged by other politicians who call for a more inclusive approach. The claims also lack consideration of other groups, and understanding of how social constructions of gender have hindered male educational outcomes. I use an objectivist approach to illuminate both problems further below. Each speaks to the difficulties dominant men have in recognizing the needs of disadvantaged men, and accepting the damaging consequences of patriarchal gender roles for men as well as women. This suggests that, while the claims appear to seek change, they serve primarily to uphold the existing gender order.

The emphasis on white male under-attainment neglects other ethnic groups who also face significant and distinctive sources of disadvantage. Recent UK data reveal that the gender gap in educational outcomes is widest amongst black pupils, with black boys performing lowest of the main ethnic groups while black girls obtained similar scores to white girls (UK Government, 2021). Odih (Reference Odih2002) reveals that black boys are four times more likely than their white peers to be permanently excluded from school. Hillman and Robinson (Reference Hillman and Robinson2016) note significant disparities between ethnic groups; lumping non-white groups together can be misleading, with success among certain ethnic groups masking difficulties for others that may equal or exceed the challenges faced by white pupils.

Meanwhile, wealthy white males have no problem obtaining favourable educational outcomes. In the UK, more men than women study at the most elite universities, and wealthy white males are five times more likely to attend university than their working-class counterparts (Hillman & Robinson, Reference Hillman and Robinson2016). Yet the needs of non-white and non-male children from working-class backgrounds were sidelined within the debates, while the privilege enjoyed by many white males was entirely absent from the discussion.

The second major omission within the claims relates to gendered socialization and the significant negative impact of certain types of masculinity on academic success. An OECD study found numerous explanations for male underachievement, including stigmatization of boys who are studious, and more negative attitudes towards school among boys. The internalization of norms of masculinity results in greater disdain for authority and feigned indifference towards study, which is seen as ‘uncool’ (OECD, 2015, p.51). Being studious and accepting authority are seen as feminized traits, and as hegemonic masculinity is premised on the subordination of behaviours deemed feminine, boys reject certain behaviours necessary for academic success (Jackson, Reference Jackson2003; Swain, Reference Swain, Kimmel, Hearn and Connell2005).

One way to avoid the stigma of being too studious is to attribute all success to talent rather than effort (Jackson & Dempster, Reference Jackson and Dempster2009). The culture of ‘effortless achievement’ reinforces hegemonic masculinity and perpetuates the stereotype that working hard is for girls, while boys are naturally brilliant (Jackson, Reference Jackson2003). However, this (unattainable) culture can produce a fear of failure among boys that prompts them to disengage. Rather than risk trying hard without succeeding, they ‘self-sabotage’ by ensuring academic failure through conspicuous lack of effort, thus preserving their masculinity at the expense of their education (Pinkett & Roberts, Reference Pinkett and Roberts2019).

Research on masculinities also illuminates the gendered role of social class (Legewie & DiPrete, Reference Legewie and DiPrete2012). Affluent boys more easily attain status through academic success and see schoolwork as instrumental towards achieving their goals. Socially disadvantaged boys more rarely see school as a strategic resource and more often use constructions of masculinity that show hostility to learning (Swain, Reference Swain, Kimmel, Hearn and Connell2005). Distrust of authority, especially for marginalized males, contributes to higher rates of exclusion and lower educational outcomes. Working-class boys also face more pressure to exit education and commence breadwinning, thus hindering social mobility, while affluent families encourage boys to study for longer to target higher-status careers (Marcus, Reference Marcus2021). Boys who cannot perform hegemonic masculinity also face distinctive challenges; those who are queer, ‘geeky’ or physically different than their peers are easily subordinated and bullied (Swain, Reference Swain, Kimmel, Hearn and Connell2005).

All the above insights are difficult to appreciate for dominant men, whose lives and careers have not been damaged by performing hegemonic masculinity. Yet, even in high office, the equation of effortless success with masculinity holds sway. This was exemplified when Prime Minister Boris Johnson mockingly described his predecessor, David Cameron, as a ‘girly swot’Footnote 11, implying that being studious is neither manly nor desirable. These norms are being reproduced in parliament even while their consequences for educational outcomes are lamented.

This extended example highlights clearly several of the arguments made in this article. This issue has a distinct impact on men; its gendered impact varies according to intersections with other identities; an understanding of masculinities is crucial; and the dominant men in power, even if aware of the problem, are unable to provide effective representation on this issue. The inaccurate framing of the problem and lack of viable solutions stem from the two core deficiencies of the over-representation of dominant men: they lack an understanding of the specific issues facing disadvantaged men, and they uphold the hegemonic masculinity that underpins the problem they are trying to solve.

Conclusion

This article has argued that SRM is an important facet of representation that has not received the attention it deserves. The numerical over-representation of men has led to complacency regarding SRM. I argue that this is problematic, for several reasons. First, while men form a majority of nearly all parliaments, the men in parliament are not descriptively representative of men in society. Dominant men are massively over-represented, while disadvantaged men are under-represented. If we ignore intersectionality and look only at male sex, we obscure the differences between men and the specific, gendered representational needs of disadvantaged men. Second, cultures of masculinity subordinate and marginalize disadvantaged men as well as women, meaning that dominant men maintain their status by neglecting the interests of others. Third, existing studies of substantive representation have taught us important lessons about under-represented groups that illustrate why the substantive representation of disadvantaged men merits attention. We cannot make generalizations about men as a group; the needs of dominant men may be privileged over those of disadvantaged men, and falsely presented as the needs of all men; and substantive representation requires group mobilization that is hindered by men's perceived majority status. I have illustrated that men have distinct gendered needs; that these are intersectional; and that these are not adequately represented by dominant men. I conclude that more descriptively representative parliaments, with more diversity between and within the sexes, would favour better substantive representation for men as well as women.

I also propose a new framework for studying SRM and advancing this research agenda. I advocate using an intersectional lens and a combination of objectivist and constructivist approaches to understand what different men's interests are, and how these interests are represented politically. An objectivist analysis can consider the full range of policies and consider their intersectional impacts on men, drawing on the rich insights from scholarship on masculinities. A constructivist analysis can identify who is making claims on behalf of men, their ideological approach, which men they are representing and whether their underlying goals are to transform or uphold the status quo.

While I have illustrated my argument with particular focus on the UK and the US, there is huge potential for future research to expand this agenda outwards, looking at a wider range of case studies from both advanced and developing democracies and considering the actors, agendas, processes and outcomes involved in SRM. Doing so could enhance both the study and practice of politics. Recognizing men as diverse gendered subjects with distinct representational needs will deepen our understanding of representation and democracy, and promote a more inclusive approach to decision-making.

Acknowledgements

This paper has developed over a long time and benefited immensely from feedback along the way. Earlier drafts of this paper were presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions workshops in 2015 and 2021, the European Conference on Politics and Gender 2015, and the London Gender and Politics seminar 2021; many thanks to those participants who gave helpful comments on this paper. The paper also benefited from invaluable feedback from Sarah Childs; Silvia Erzeel; Florence Faucher; Ana Gilling; Jeff Hearn; Daniel Höhmann; Mette Marie Harder; Ragnhild Muriaas; Haley Norris; Diana O'Brien; Ekaterina Rashkova; Jack Sheldon; and Christina Wolbrecht. I would particularly like to thank Tim Bale, Elin Bjarnegård, Cas Mudde and Robin Pettitt for their continued support, encouragement and feedback. Last but not least, my thanks to the editors and anonymous reviewers at EJPR for their valuable input.