1. Introduction

The establishment of pilot free trade zones (PFTZs) is not only a calculated strategic decision aligned with new trends in the development of international free trade zones (FTZs) but also a place-based approach to deepening reform in China through pilot and demonstrative institutional innovations (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Sun and Yuan2023). The PFTZ policy plays an important role in improving the governance quality of local governments. PFTZs have the potential to stimulate institutional innovation, promote innovative development in government management modes, push local government to transform from approval to regulatory service-oriented function, and strengthen local government regulatory capabilities, further enhancing the governance quality of local governments (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Shen, Zhang and Cai2024). Additionally, PFTZs may stimulate the inventiveness of local governments through the competition and innovation brought about by expanding openness (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Leng and Qiu2023). Furthermore, PFTZs may force domestic factor market reforms, accelerate the free flow of factors across regions and industries, and optimize factor allocation, further attracting high-end factors to gather in zones (Ge et al., Reference Ge, Liu, Zhang and Liu2023), thereby improving the governance quality of local governments.

Many studies on the policy effects of FTZs have mainly investigated their economic consequences, particularly the impact on outward-oriented economic development (Wang et al., Reference Wang and Shao2022; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Cao and Zhao2023; Jing et al., Reference Jing, Zheng and Shen2024; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Zhang and Li2024). A large body of literature has demonstrated that the PFTZ policy plays a significant role in promoting regional economic growth (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hu, Liu, Wang and Zheng2022), trade development (Wang and Shao, Reference Wang and Shao2022), capital flow (Bao et al., Reference Bao, Dai, Feng, Liu and Wang2023), and foreign investment (Lei, Reference Lei and Xie2023). Some studies have enriched empirical research on the policy effects of PFTZs from the perspective of economic quality. Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Leng and Qiu2023) found that PFTZs can improve the effectiveness of regional innovation by attracting FDI. Li et al. (Reference Li, Liu and Kong2021) discovered that enterprises can increase labor productivity and management efficiency by utilizing the high-quality resources in PFTZs. Guan et al. (Reference Guan, Huang, Jiang and Xu2023) revealed that the Guangdong PFTZ can promote the modernization of the structure of the service industry through encouraging innovation and business agglomeration. Yan et al. (Reference Yan, He, Qian and Liu2024) found that PFTZs can significantly promote green economic efficiency through technological progress and industrial structure upgrading. Li et al. (Reference Li, Pang and Zhu2024) demonstrated the benefits of PFTZs for regional entrepreneurship due to the increased openness of trade and foreign investment, as well as financial development. Zeng et al. (Reference Zeng, Zhang and Li2024) found that PFTZs can promote the ESG performance of local enterprises.

The existing literature has demonstrated the economic effects of PFTZs from different perspectives, providing valuable references for this study. However, several aspects need to be improved. First, existing studies mainly empirically examine the policy effects of PFTZs from an economic development perspective, while new institutional economics believe that economic development stems from institutional innovation. The original purpose for which PFTZs were designed is to comply with sophisticated and high-standard trade and investment regulations, replicate and foster institutional innovation, encourage the modernization of governmental operations, and improve LGQ. Examining the policy effects of PFTZs from the standpoint of local government governance and its mechanisms provides a valuable supplement to existing empirical studies on PFTZ. Second, discussions about the impact of PFTZs on LGQ are mostly conducted at the theoretical level, with a lack of corresponding empirical research. Objectively and accurately evaluating the policy effects of PFTZs on LGQ contributes to a deep understanding of the functional positioning of PFTZs. Third, the available studies have demonstrated the policy effects of PFTZs, mainly focusing on the impact on outward-oriented economic development. Few studies have discussed how PFTZs affect LGQ under the background of expanding openness, and the policy effects of PFTZs may change under the economic growth target management system. Therefore, research on the impact of PFTZs on LGQ should consider the moderating effects of continuously increasing openness and the management of economic growth targets in China.

Compared to the existing literature, this study mainly focuses on three aspects. First, in terms of empirical contributions, the existing studies evaluate the policy effects of PFTZs mainly from the perspective of economic development, while this paper evaluates the policy effects of the PFTZ from the perspective of LGQ, expanding the research boundaries of the policy effects of the PFTZ. Second, in terms of theoretical contributions, this study explores the mechanism of how PFTZs promote LGQ via the institutional spillover effect, factor allocation effect, and talent agglomeration effect, expanding the research boundary of the ‘theoretical black box’ of LGQ. Third, in terms of implications for further research, this study examines the effect of PFTZs on LGQ influenced by FDI spillover and economic growth pressure. While this study has confirmed that PFTZs can improve LGQ, it has also confirmed that the impact of FTZs on LGQ under the influence of FDI spillover and economic growth pressure exhibits unique characteristics. This provides empirical evidence for future research on PFTZs in China’s current administrative system.

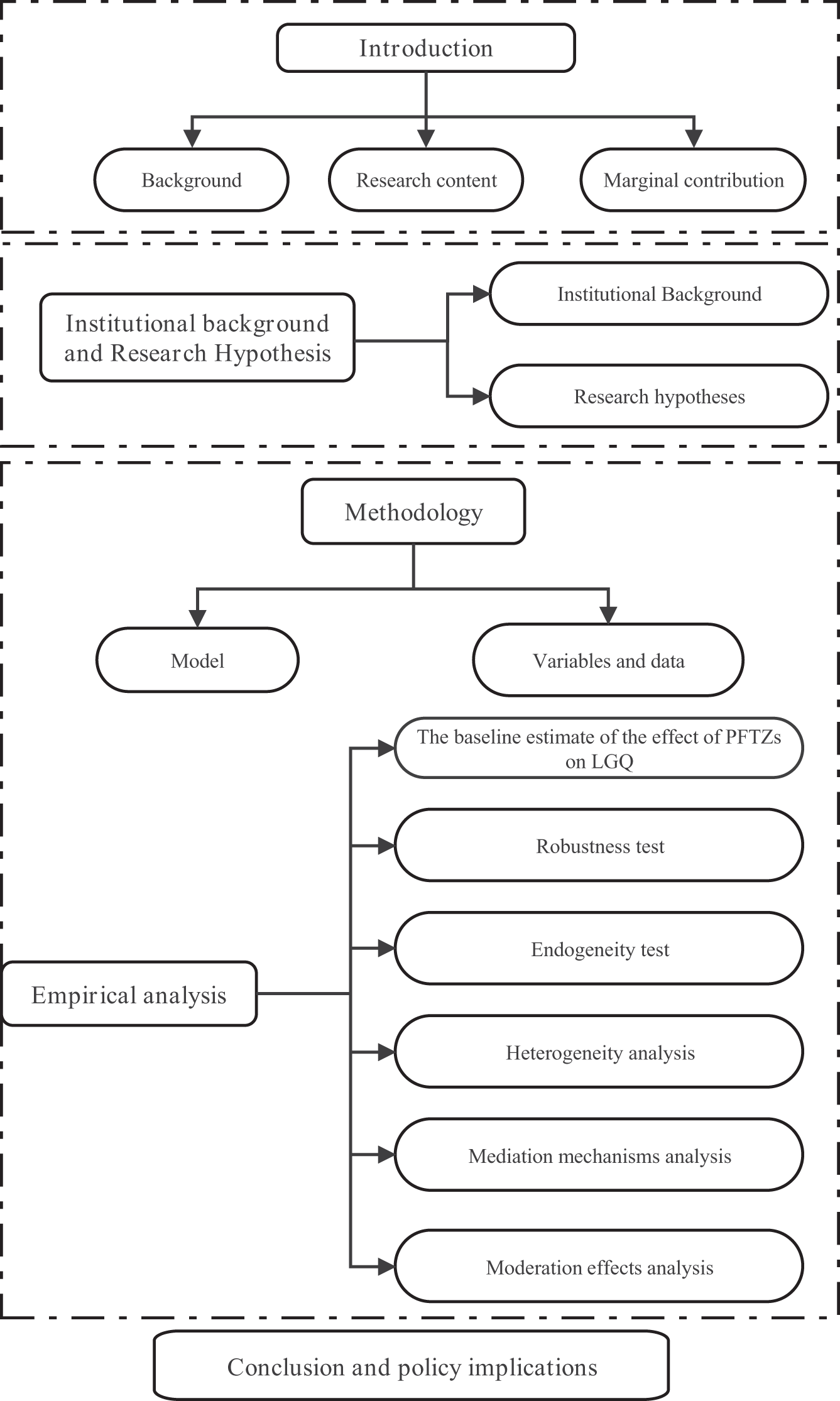

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the institutional background of PFTZ and explains the impact of PFTZs on LGQ. Section 3 focuses on the description of the model, variables, and data. Section 4 focuses on the empirical results and analysis. Section 5 presents the study’s conclusions. Figure 1 shows the structure of this paper.

Figure 1. Research structure.

2. Institutional Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1 Institutional Background

During the process of steady trade development in China, the implementation of the PFTZ policy has made significant contributions. Since 2012, the State Council has begun to integrate customs special supervision zones (CSSZs), and the ‘Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Scientific Development of Customs Special Supervision Zones’ has consolidated various forms of CSSZs into comprehensive bonded zones. The State Council has authorized the creation of 22 PFTZs since the establishment of the Shanghai PFTZ in 2013. Subsequently, the policies of China’s PFTZs gradually unfolded. A preliminary three-dimensional layout of ‘1+3+7+1+6+3+1’ was formed, demonstrating a development trend of coordinated progress from east to west, south to north, and central regions, as well as land–sea linkage.

The PFTZ policy has a significant impact on the reform of government operations and the enhancement of governance standards. By the end of 2022, all PFTZs had implemented more than 3,400 reform measures, with over 200 institutional innovation achievements successfully replicated and promoted nationwide and in specific areas, such as financial services for the real economy, trade and investment facilitation, and the transformation of government functions. These achievements fully manifest the results of China’s reforms and opening up as well as demonstrate and guide the reform process of other fields.

The existing literature has reached a certain consensus on the positive impact of PFTZs in the economic field (Li et al., Reference Li, Liu and Kong2021; Guan et al., Reference Guan, Huang, Jiang and Xu2023; Yan et al., Reference Yan, He, Qian and Liu2024), but studies on the policy effects of PFTZs in non-economic fields are relatively scarce. From the perspective of functional positioning, the establishment of PFTZs is not just an economic development policy. Its original intention was to align with high standards and advanced investment and trade rules and to replicate and promote institutional innovation. This functional positioning implies that discussing the policy effects of PFTZs should not be limited to the economic field. Exploring its impact on non-economic fields, especially the governance quality of local government, is of great practical significance (Chang and Lai, 2023).

Therefore, to fill the gap in existing research on the effects of the PFTZ policy in non-economic fields, this study employs the DID method of empirical analysis for the impact of PFTZs on LGQ and location and batch heterogeneity of PFTZs. Furthermore, the study comprehensively explores the policy effect of PFTZs through the analysis of mechanisms: institutional spillover effect, factor allocation effect, and talent aggregation effect. Finally, this study discusses and observes how the impact of PFTZs on LGQ changes under FDI spillover and economic growth pressures.

2.2 Research Hypotheses

2.2.1 The Impact of PFTZs on LGQ

According to the resource-based view theory, the improvement of LGQ stems from its unique resources and capabilities, and the PFTZs are unique policy resources given to local governments by the central government. PFTZs undertake the task of exploring the establishment of new systems beyond the existing one and are crucial in deepening China’s institutional reforms, with a profound impact on LGQ. First, the transformation of the governance model of local governments is a key factor in regulating international business practices and expanding foreign trade (Nam et al., Reference Nam, Bang and Ryu2023). This involves eliminating and reducing approvals, implementing a ‘negative list’ system, and transforming from pre-approval reform to in-process and post-event supervision, thereby promoting the transformation of the government’s regulatory and service functions. Second, PFTZs can enhance the dynamic capacity of local governments by providing institutional resources for local governments, encouraging innovation and reform, simplifying administrative approval and business processes, providing one-stop services, reducing cumbersome procedures and links, and enhancing local government service efficiency. Third, PFTZs can expand openness, strengthen information sharing, reduce information asymmetry, and attract external resources, which are beneficial for improving LGQ. Expanding openness may also promote innovation and competitiveness, which will boost the viability and inventiveness of local governments. Consequently, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1: The establishment of PFTZs can improve LGQ.

2.2.2 The Mechanism of the Impact of PFTZs on LGQ

The original purpose of the construction of PFTZs is institutional innovation. A series of explorations have been carried out in investment management systems, trade supervision systems, financial regulatory systems, and in-process and after-the-fact supervision. PFTZs are agglomeration zones of innovative institutional resources. According to the cluster theory, the institutional resources in PFTZs often attract widespread attention and provide a model for local governments to learn from, leading to institutional spillover effects and promoting LGQ. In addition, PFTZs usually enjoy policy preferences and market advantages, which can attract many enterprises. The neighboring governments face competitive pressure from local PFTZs; and to attract investment and resources, they may adopt more efficient and market-oriented governance measures. Ultimately, the institutional innovation of PFTZs will build a favorable business environment, enhancing information transparency and reducing transaction costs (Bao et al., Reference Bao, Dai, Feng, Liu and Wang2023). Consequently, governments can reduce the governance costs incurred due to market distortions, thereby improving the governance quality of local governments.

PFTZs serve as spatial carriers for industrial clusters. According to Porter’s cluster theory, industrial clusters in PFTZs can potentially lessen the misallocation of labor and capital, enhance resource usage efficiency, and promote the rational upgrading of industries (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Sun and Yuan2023). The enterprises in PFTZs can use policy advantages to form efficient production industrial chains by encouraging company aggregation, introducing new technologies, and improving industrial structure and resource allocation efficiency (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Huang, Jiang and Xu2023; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Zhang and Li2024). In addition to fostering the application of science and professionalization of government decision-making and effectively mitigating the problem of information asymmetry between business and government, increased factor allocation efficiency can also lessen frictions resulting from shifts in factor mismatch, largely preventing resource waste and needless intervention and enhancing resource allocation to local governments.

PFTZs can attract the inflow of high-end factors and produce combined effects through institutional innovation and preferential policies. According to the principle of combined effect, PFTZs bring together enterprises in specific regions, promoting the gathering of diversified talents and the exchange of knowledge (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Shen, Zhang and Cai2024). Furthermore, relying on an excellent business environment, PFTZs can attract more high-tech and high-value-added enterprises. These businesses are frequently at the top of the global industrial chain, and can stimulate the growth of other industries in the host country and produce high-value jobs to attract more affluent workers (Li et al., Reference Li, Pang and Zhu2024). These high-end talents usually possess advanced management concepts and methods. Talent exchange can foster innovative thinking and cross-border cooperation, assisting local governments in establishing more efficient and transparent governance systems and in improving the quality of local government services. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2: PFTZs can improve LGQ through the institutional spillover effect, factor allocation effect, and talent agglomeration effect.

2.2.3 The Moderating Effect of FDI Spillover

One significant aspect influencing LGQ is their openness. The ‘efficiency hypothesis’ holds that governments will be pressured by market competition and international standards, compelling them to improve their efficiency. However, openness can introduce more external resources and technology, stimulate economic growth, and promote LGQ (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liu, Wang, Zhao and An2021). The ‘compensation hypothesis’ proposes that pressure from the international market would weaken the government’s ability to control the domestic market, leading to regulatory and supervisory difficulties. Therefore, governments must allocate resources to meet the demands of openness, thereby decreasing LGQ (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Hao and Ren2020).

The introduction of FDI can accelerate the flow of factors among different sectors and improve the efficiency of openness-related departments. Additionally, the entry of FDI can lead to local governments being subject to increasing external influences, including learning from practices in other regions, which can effectively enhance LGQ. Moreover, intense international competition will lead to resource allocation that is more rational in domestic production sectors, reducing government intervention in local enterprises and improving governance efficiency. PFTZs, with the liberalization of investment, implement a more open investment policy and expand market opening and international cooperation, which helps drive the institutional reform of local governments, especially for regions with low FDI openness.

Hypothesis 3: PFTZs can negatively moderate FDI spillover on LGQ

2.2.4 The Moderating Effect of Economic Growth Pressure

When local governments face the pressure of economic growth, unhealthy governance patterns may emerge in the pursuit of maximizing benefits (Ji, 2022). LGQ is significantly influenced by path dependence, potentially leading to lower LGQ (Senshaw and Twinomurinzi, Reference Senshaw and Twinomurinzi2024). According to contingency theory, under the pressure of economic growth, PFTZs may emerge as a new instrument to promote local economic growth. PFTZs can draw on additional external resources and high-quality businesses, leading to an optimized distribution of local resources. This, in turn, can help alleviate the economic growth pressures often placed on local government entities. This could potentially encourage local governments to focus the core functions of PFTZs on invigorating the local economy. However, there might be a lack of sufficient and effective incentives for institutional innovation, which could be detrimental to stimulating the innovative vitality of local governments and to improving their governance practices. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 4: Economic growth pressure can distort the impact of PFTZs on LGQ.

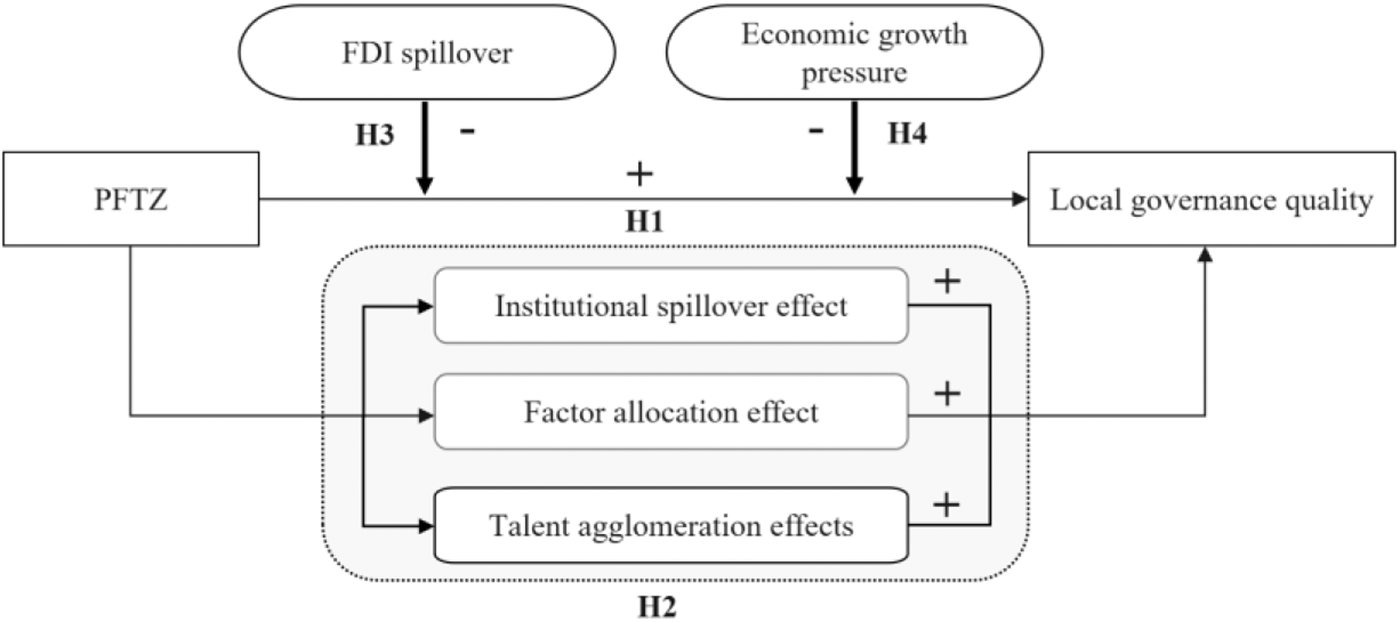

A summary diagram of the research hypothesis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Research hypothesis.

3. Methodology

3.1 Model Building

The PFTZ is a strategic measure for building a new platform for a comprehensive opening up. From September 2013 to the present, 22 PFTZs have been established in batches to encourage China to construct a new phase of comprehensive opening patterns. PFTZs are important measures for responding actively to international economic and trade rule transformations. Establishing PFTZs can be regarded as a policy experiment in multiple batches by the central government, providing an ideal ‘quasi-natural experiment’ to use the multi-period DID method. In this study, 18 provinces that have established PFTZs are taken as the experimental group, while provinces that have not established PFTZs are taken as the control group. The model is set as follows:

where the subscripts i and t represent the province and year, respectively; LGQ represents the local governance quality (LGQ); PFTZ represents the dummy variable of the PFTZ; and X is a set of control variables, including foreign trade dependence, urbanization rate, industrial structure, economic density, and digitalization level. Since the impact on LGQ has a certain lag, we lag the establishment of the PFTZ variable and control variables by one year. εi and φt represent unobservant provincial and year-fixed effects, and μit represents the residual term.

The previous model has not yet studied internal mechanisms. This study selects the three channels of institutional spillover, factor allocation, and talent agglomeration effects to verify the pathways through which PFTZs promote LGQ. It sets the following models regarding Wu et al.’s (Reference Wu, Tian, Liu and Huang2024) analysis approach:

\begin{align*}&{M_{it}} = \alpha + \eta PFT{Z_{it}} + \theta {X_{it}} + {\varepsilon _i} + {\varphi _t} + {\mu _{it}}\\

&LG{Q_{it + 1}} = \alpha + \beta PFT{Z_{it}} + \lambda {M_{it}} + \theta {X_{it}} + {\varepsilon _i} + {\varphi _t} + {\mu _{it}}\end{align*}

\begin{align*}&{M_{it}} = \alpha + \eta PFT{Z_{it}} + \theta {X_{it}} + {\varepsilon _i} + {\varphi _t} + {\mu _{it}}\\

&LG{Q_{it + 1}} = \alpha + \beta PFT{Z_{it}} + \lambda {M_{it}} + \theta {X_{it}} + {\varepsilon _i} + {\varphi _t} + {\mu _{it}}\end{align*}where M is a mediating variable, including the institutional spillover effect (MKT), factor allocation effect (RTL), and talent agglomeration effect (TAL).

3.2 Data Sources

Considering data availability, the empirical research sample in this study consists of 30 provinces on the Chinese mainland, excluding Tibet, from 2004 to 2020. A total of 30 provinces and 510 observations (30*17 = 510) are included in the sample. The original data for the variables are from the China Statistical Yearbook (2005–2021) and Provincial Statistical Yearbook (2005–2021). The employment data comes from the China Population and Employment Statistics Yearbook (2005–2021). Lawyer data come from the China Social Statistics Yearbook (2005–2021), Provincial Statistics Yearbooks, provincial bar associations, and the Ministry of Justice. The China Statistical Yearbook (2005–2021) provides various non-specific data, whereas the China Industrial Statistics Yearbook (2005–2021) provides the total assets of private industrial enterprises. Interpolation is used to supplement missing data.

3.3 Definition of Variables

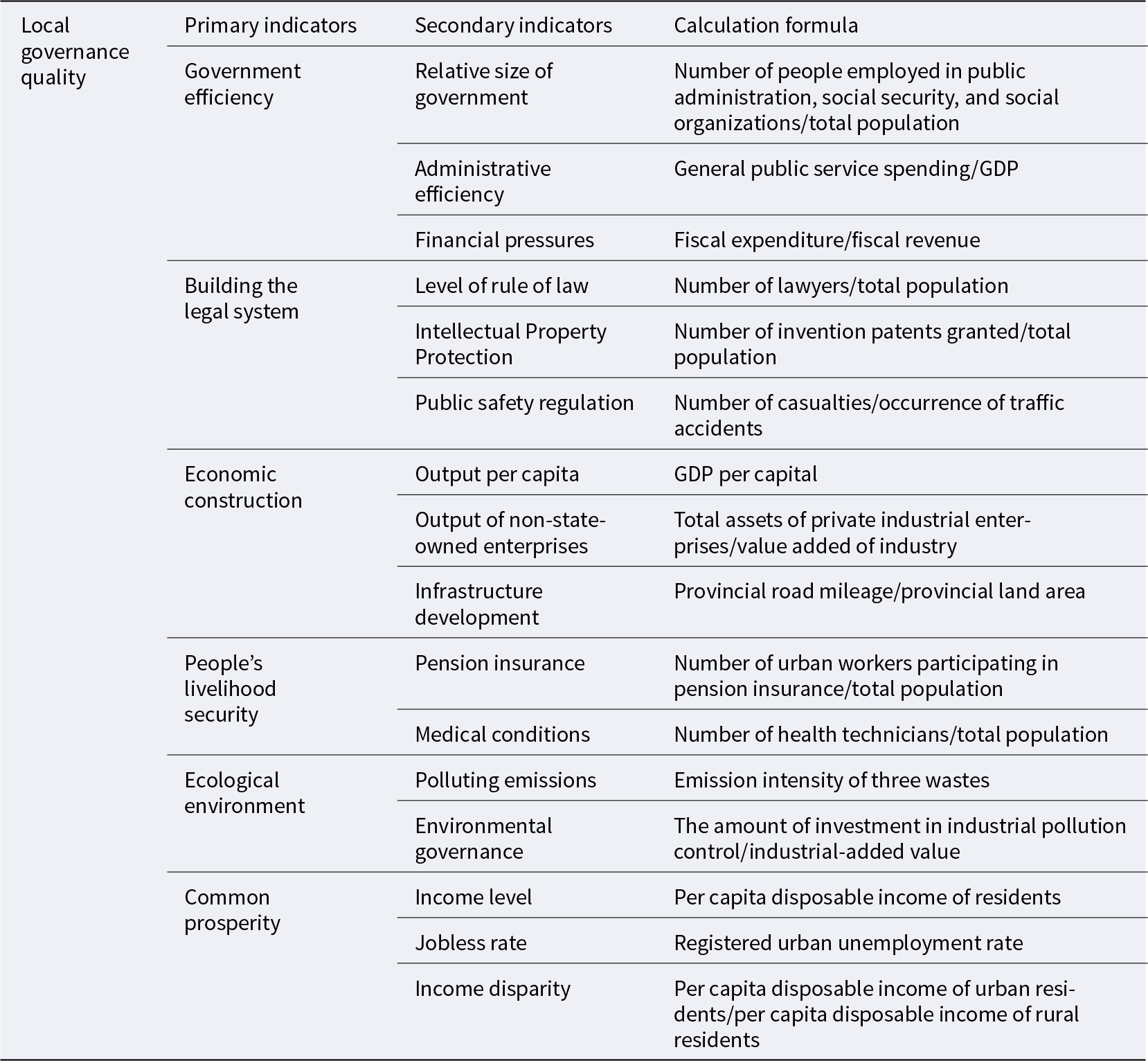

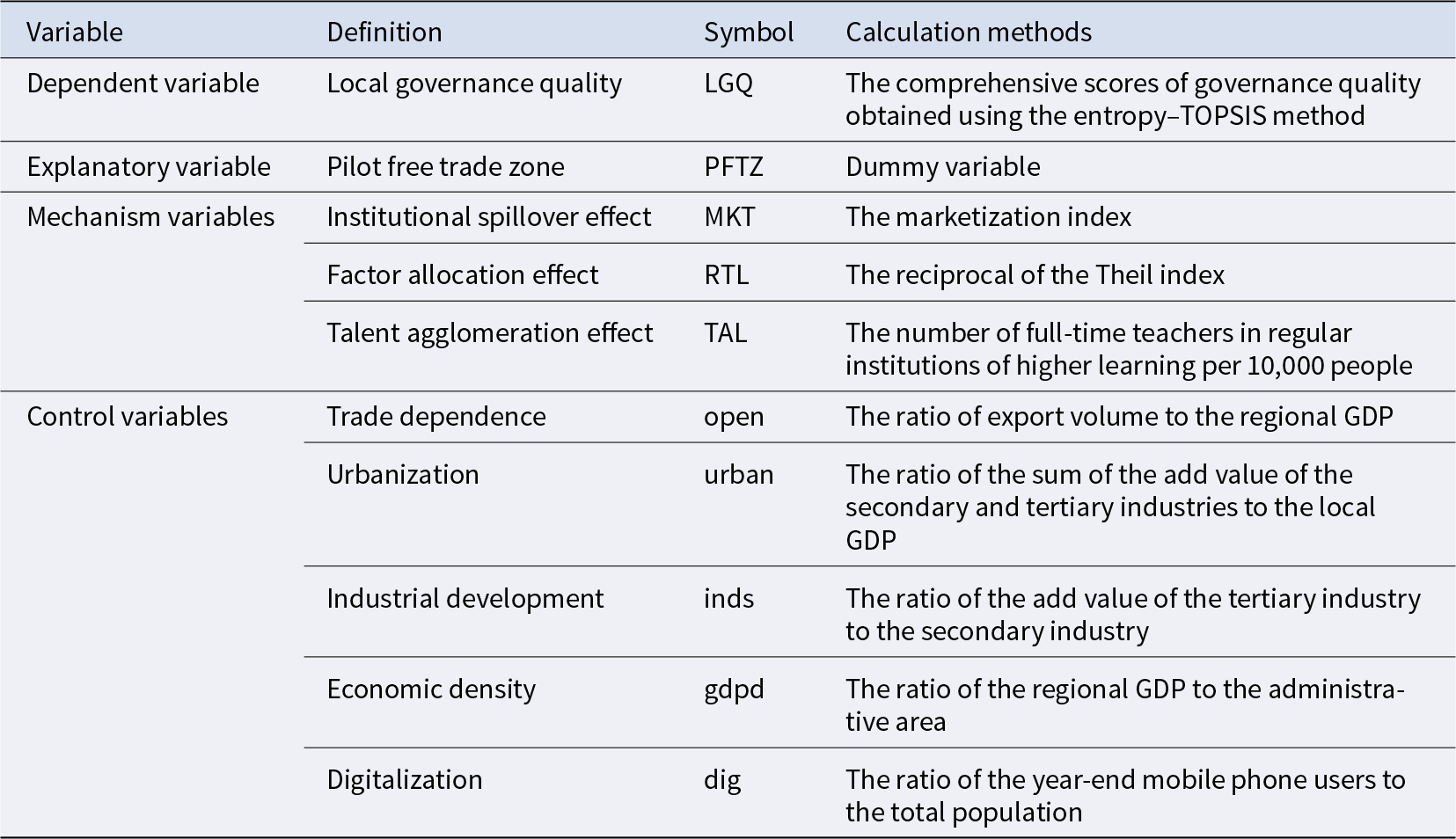

Dependent variable: Local Governance Quality. Considering the overall influence of the government on society and the whole influence of the present and future, the single index has obvious limitations; therefore, scholars draw lessons from the World Bank’s governance index ideas to build LGQ indicators. Zehra et al. (Reference Zehra, Majeed and Ali2021) measured the comprehensive index in the ICRG index, including democratic accountability, government stability, bureaucratic quality, corruption, and legal order. Tang et al. (Reference Tang, Liu, Wang, Lin and Su2018) proposed an index system for provincial governance quality in China, including rule of law, marketization, and government capacity. Based on the above studies, this study expands the dimension of LGQ to include six primary and 16 secondary indicators covering government efficiency, legal construction, economic development, livelihood security of people, ecological environment, and common prosperity. Based on these, the LGQ index for the mainland provinces of China, excluding Tibet, is constructed, and the comprehensive scores of governance quality are obtained using the entropy–TOPSIS method. Considering the differences in the sizes and units of the data for different indicators, all data need to be standardized. Among them, government relative scale, administrative efficiency, fiscal pressure, public safety supervision, pollution emissions, unemployment rate, and income gap are negatively correlated indicators of LGQ. In constant 2000 prices, the actual value is given as the GDP and disposable income per capita. Table 1 displays the indicator system.

Table 1. Indicator system of local governance quality

Independent variables: The establishment of PFTZs (PFTZ). Based on the list of PFTZs published by the China Development Zone Network (www.cadz.org.cn), the official establishment times of PFTZs are confirmed one by one, and values are assigned to different provinces in different years. For instance, if a PFTZ is initially established or has been established in province i during year t, then PFTZit=1; otherwise, PFTZit=0.

Mediating variables: The institutional spillover effect (MKT) is represented by the marketization index. We calculate the average growth rate of the marketization index over the years and extend it to 2020. The factor allocation effect (RTL) is measured by industrial rationalization. Following Xiong et al. (Reference Xiong, Zhang, Zhang and Wang2023), the degree of industrial rationalization is gauged using the Theil index, with the specific calculation formula being  $TL = \sum\nolimits_{n = 1}^3 {\frac{{{Y_n}}}{Y}} \ln \left( {{{\frac{{{Y_n}}}{{{L_n}}}} \mathord{\left/

{\vphantom {{\frac{{{Y_n}}}{{{L_n}}}} {\frac{Y}{L}}}} \right.

} {\frac{Y}{L}}}} \right)$, where Y and L are the total output value and the number of employed people, n is the number of industrial sectors, and the Theil index is calculated based on the division of the three major industries. Considering that the Theil index is an inverse evaluation index of industrial rationalization, for convenience, this study uses the reciprocal of the Theil index (RTL) to measure the factor allocation effect. The talent agglomeration effect (TAL) is represented by the number of full-time teachers in regular institutions of higher learning per 10,000 people.

$TL = \sum\nolimits_{n = 1}^3 {\frac{{{Y_n}}}{Y}} \ln \left( {{{\frac{{{Y_n}}}{{{L_n}}}} \mathord{\left/

{\vphantom {{\frac{{{Y_n}}}{{{L_n}}}} {\frac{Y}{L}}}} \right.

} {\frac{Y}{L}}}} \right)$, where Y and L are the total output value and the number of employed people, n is the number of industrial sectors, and the Theil index is calculated based on the division of the three major industries. Considering that the Theil index is an inverse evaluation index of industrial rationalization, for convenience, this study uses the reciprocal of the Theil index (RTL) to measure the factor allocation effect. The talent agglomeration effect (TAL) is represented by the number of full-time teachers in regular institutions of higher learning per 10,000 people.

Control variables: trade dependence (open), represented by the ratio of export volume to the regional GDP; urbanization (urban), represented by the proportion of the sum of the value added by the secondary and tertiary industries to regional GDP; industrial development (inds), represented by the ratio of the value added by the tertiary industry to secondary industry; economic density (gdpd), represented by the ratio of regional GDP to the administrative area; digitalization (dig), represented by the ratio of the year-end mobile phone users to the total population. Table 2 reports the definitions of the main variables.

Table 2. Definitions of the main variables

3.4 Descriptive Statistics

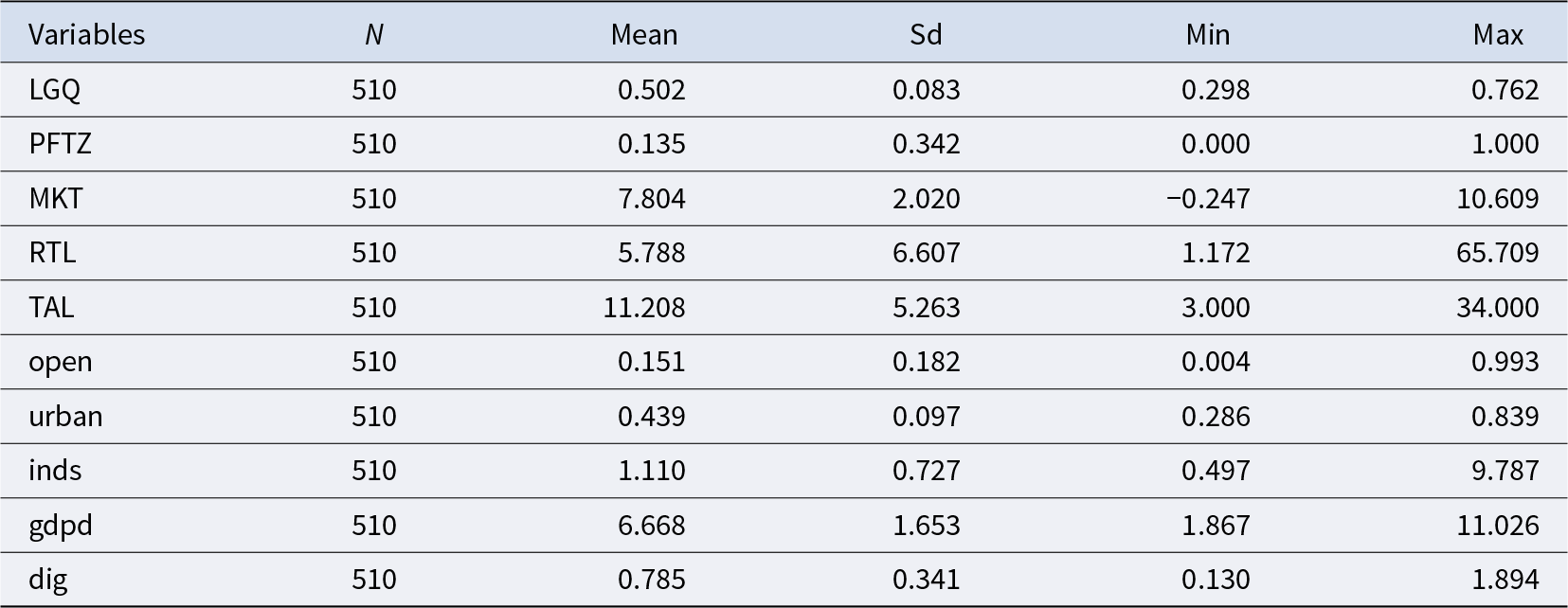

Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics of the main variables. The mean value of LGQ is 0.502, and the standard deviation is 0.083, which indicates that there are some differences in the quality of local government governance in different provinces, showing the reasonableness of using the fixed-effects model. The mean value of PFTZ is 0.135, indicating that 13.5% of the observations in the sample are in the treatment group and that the small sample incidental has less influence on the empirical results, which makes it suitable for estimation using the DID method.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the main variables

4. Empirical Analysis

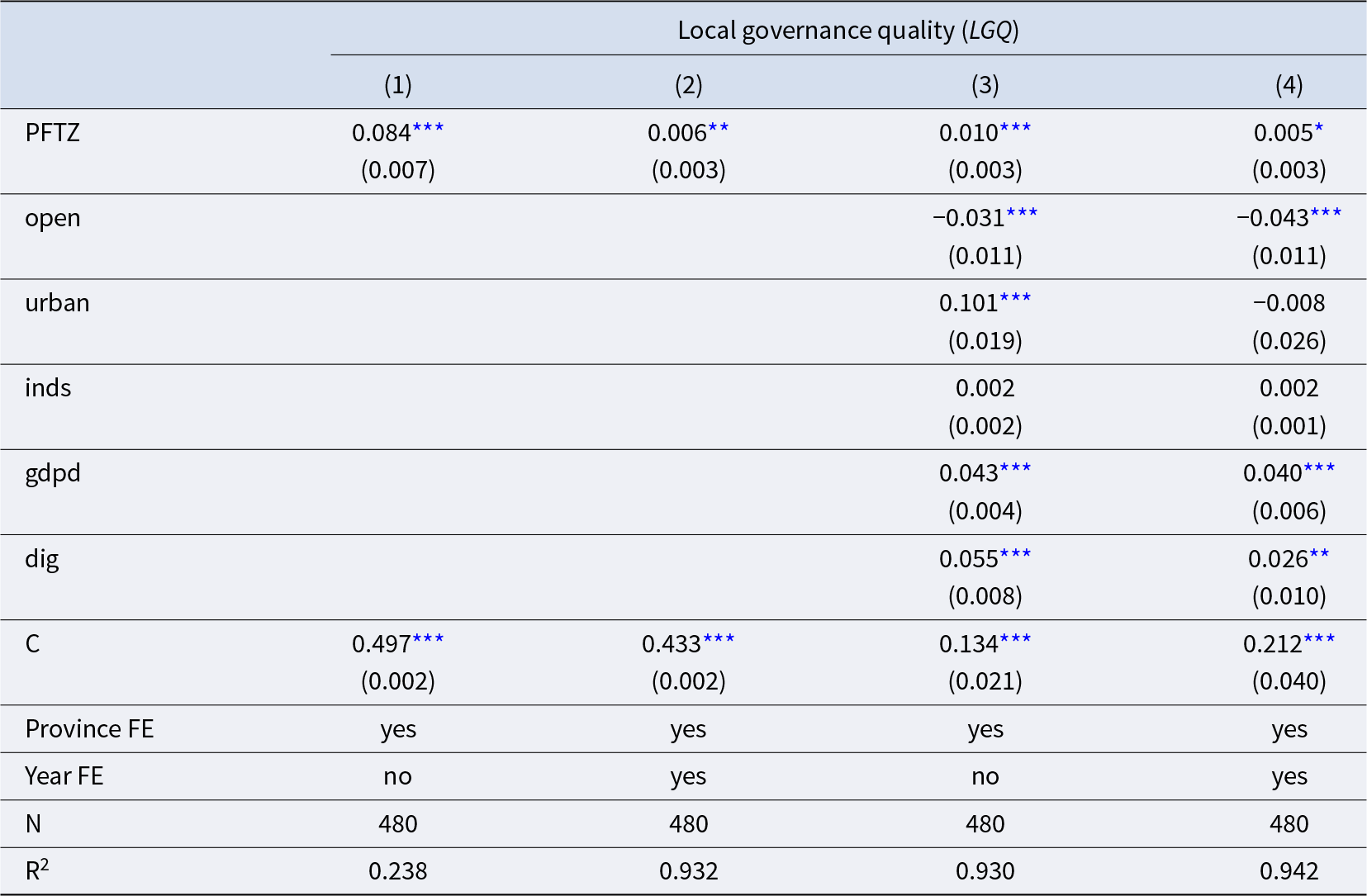

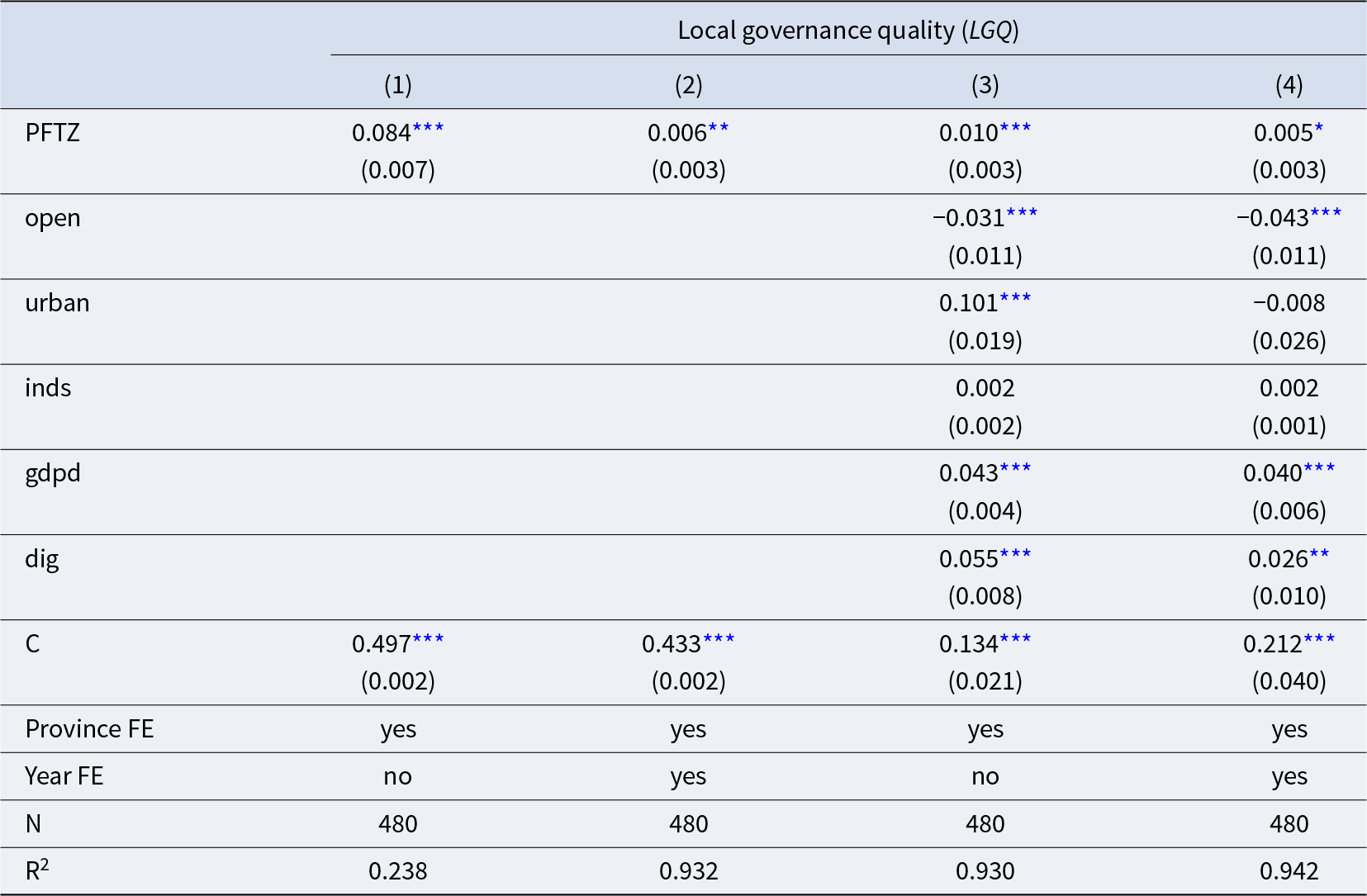

4.1 Baseline Estimates

The regression results of the impact of PFTZs on LGQ are shown in Table 3. Columns 1 and 2 show the results without the control variables. Whether or not the year-fixed effect is added, the coefficient of PFTZ remains significantly positive. After incorporating control variables, the results are reported in columns 3 and 4. After considering the year, province-fixed effects, and control variables, the coefficient of PFTZ is significantly positive. This indicates that the establishment of PFTZs can improve LGQ.

In the control variables, trade dependency (open) has a negative impact on LGQ. Expanding foreign trade openness can lead to unpredictable external risks, prompting local governments to expand the scale of fiscal expenditures. The coefficient of urbanization (urban) is not significant, indicating that urbanization is not the primary factor affecting LGQ. The promotional effect of industrial development (inds) on LGQ is not significant. Industrial development and upgrading require public infrastructure, which will compel local governments to enhance governance quality and increase the financial burden on the government. Economic density (gdpd) has a significant positive influence on LGQ. Economic density reflects a comprehensive level of regional economic development. With the development of the economy, public sector expenditure will shift toward education, medical care, and welfare services, to some extent contributing to the enhancement of LGQ. Digitalization (dig) has a significant positive effect on LGQ. Digital technology can significantly reduce various transaction costs of governance and promote digital collaborative governance, thereby improving LGQ.

4.2 Robustness Test

The previous section revealed that establishing PFTZs has a significant promoting effect on LGQ. To ensure the reliability of this result, this study has further conducted robustness tests, and the specific operations and results are as follows:

4.2.1 Parallel Trend Test

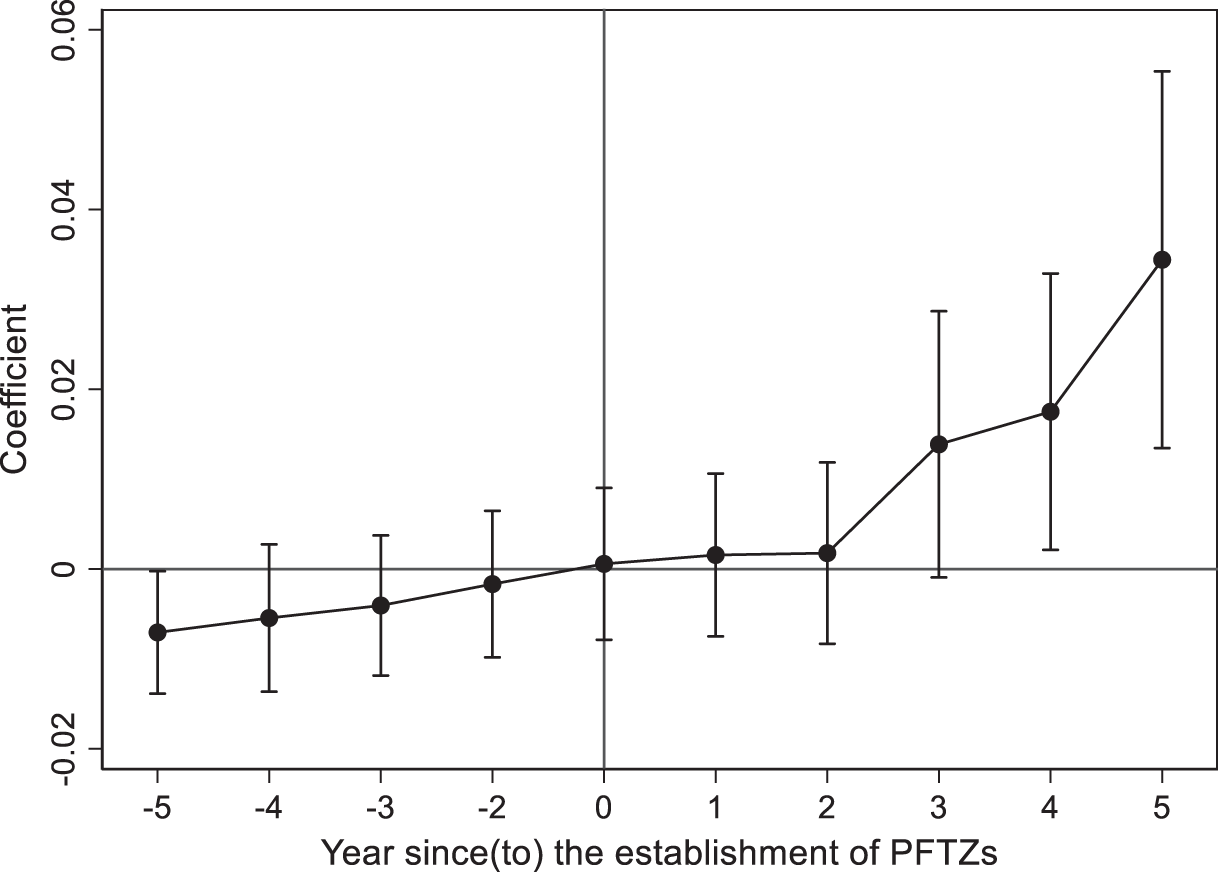

The premise of the DID model is that, before the establishment of PFTZs, the change in LGQ of the provinces with and without PFTZs should satisfy the assumption of parallel trends (Lai and Chang, Reference Lai and Chang2023). The event research method was adopted to examine whether the parallel trend assumption holds, and the model was developed:

\begin{equation*}LG{Q_{it + 1}} = \alpha + \mathop \sum \limits_{n = - 5,\,n \ne - 1}^5 {\delta ^n} \times D_{it}^n \times PFT{Z_{it}} + \theta {X_{it}} + {\varepsilon _i} + {\varphi _t} + {\mu _{it}}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}LG{Q_{it + 1}} = \alpha + \mathop \sum \limits_{n = - 5,\,n \ne - 1}^5 {\delta ^n} \times D_{it}^n \times PFT{Z_{it}} + \theta {X_{it}} + {\varepsilon _i} + {\varphi _t} + {\mu _{it}}\end{equation*} where, when ![]() $t - PFTZ\_yea{r_i} = n$,

$t - PFTZ\_yea{r_i} = n$, ![]() $D_{it}^n = 1$; otherwise

$D_{it}^n = 1$; otherwise ![]() $D_{it}^n = 0$;

$D_{it}^n = 0$; ![]() $PFTZ\_yea{r_i}$ indicates the year of establishment of PFTZ; the range of n is –5、–4、–3, –2, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and the samples after five years are unified into five years. Figure 3 presents the results of the parallel trend test. The parallel trend hypothesis was satisfied because there was no discernible difference in the trend of change, and the difference in governance quality between the experimental and control groups could not reject the null hypothesis of 0.

$PFTZ\_yea{r_i}$ indicates the year of establishment of PFTZ; the range of n is –5、–4、–3, –2, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and the samples after five years are unified into five years. Figure 3 presents the results of the parallel trend test. The parallel trend hypothesis was satisfied because there was no discernible difference in the trend of change, and the difference in governance quality between the experimental and control groups could not reject the null hypothesis of 0.

Figure 3. Results of parallel trend test.

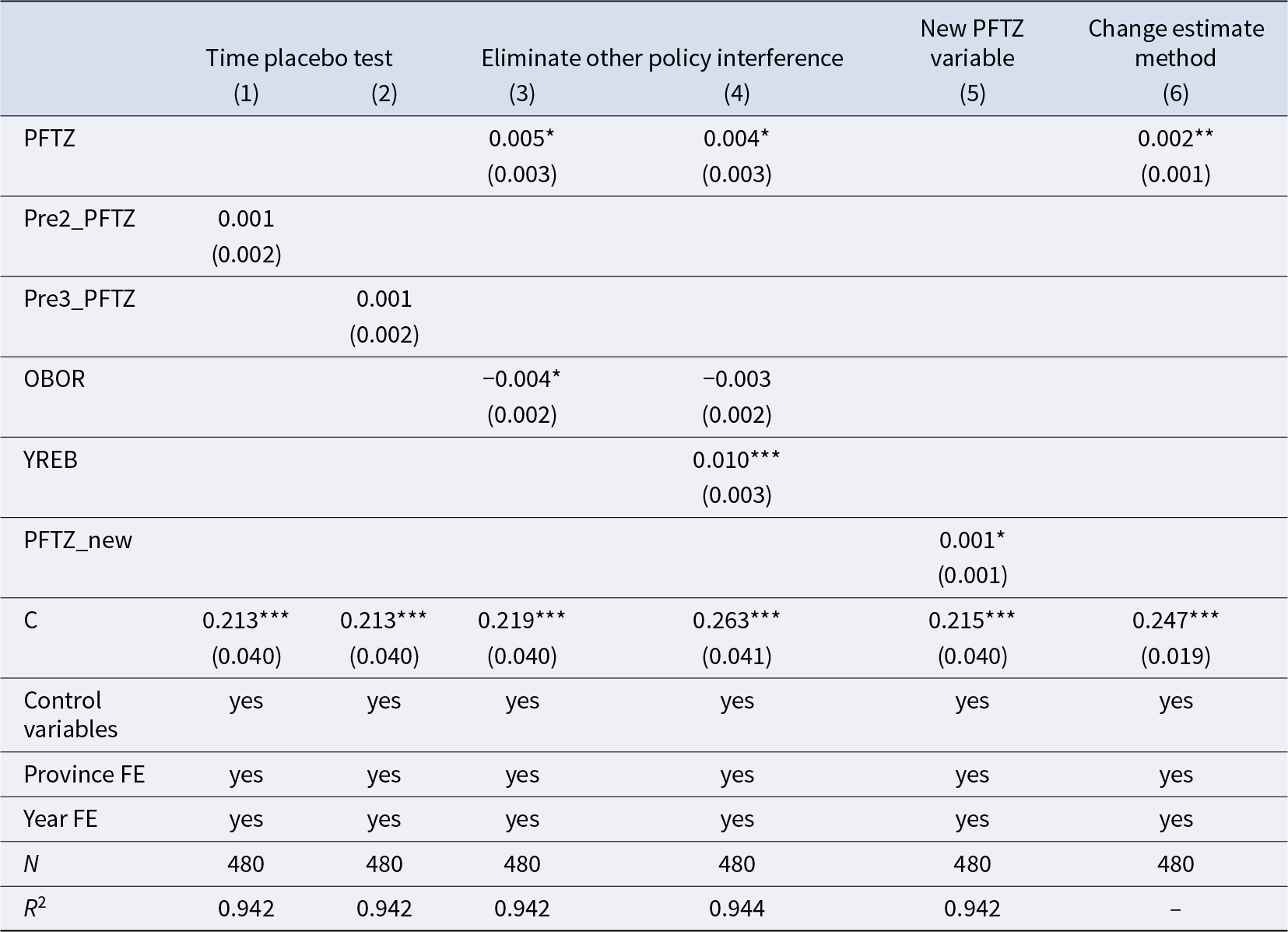

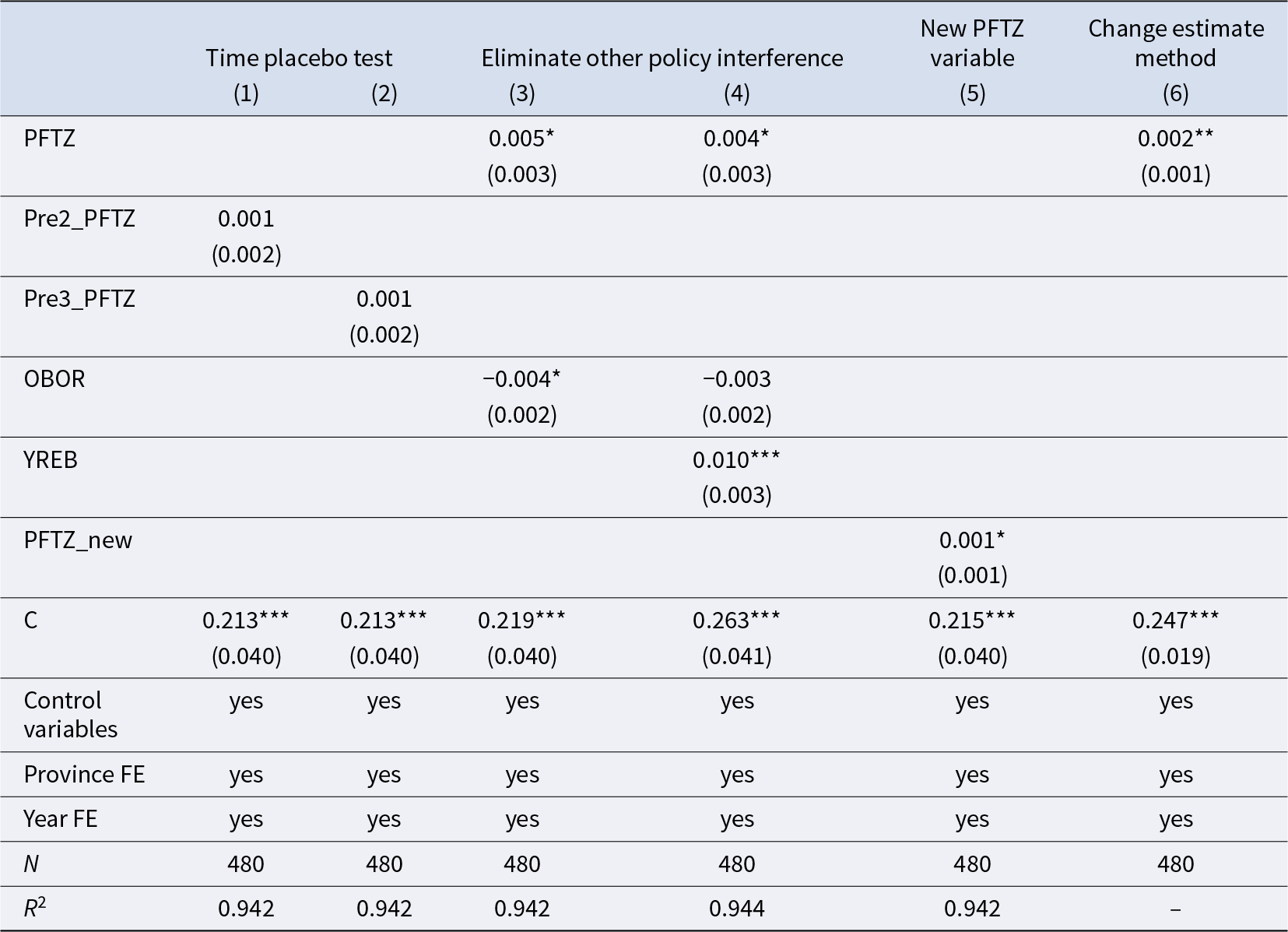

4.2.2 Placebo Test

Apart from establishing PFTZ, other policies or random factors could also affect LGQ, resulting in the conclusion not holding true. To eliminate the influence of these factors, it is assumed that the year of establishment of PFTZs is advanced by two or three years, and a time placebo test is conducted. As shown in columns 1 and 2 of Table 4, advancing the year of the establishment of PFTZs has no significant impact on LGQ, indicating that the improvement in LGQ comes from PFTZs.

Table 4. Results of the baseline estimates

*** Notes: ***, **, and * represent that the difference is significant at 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The same as below.

Table 5. Results of robustness test

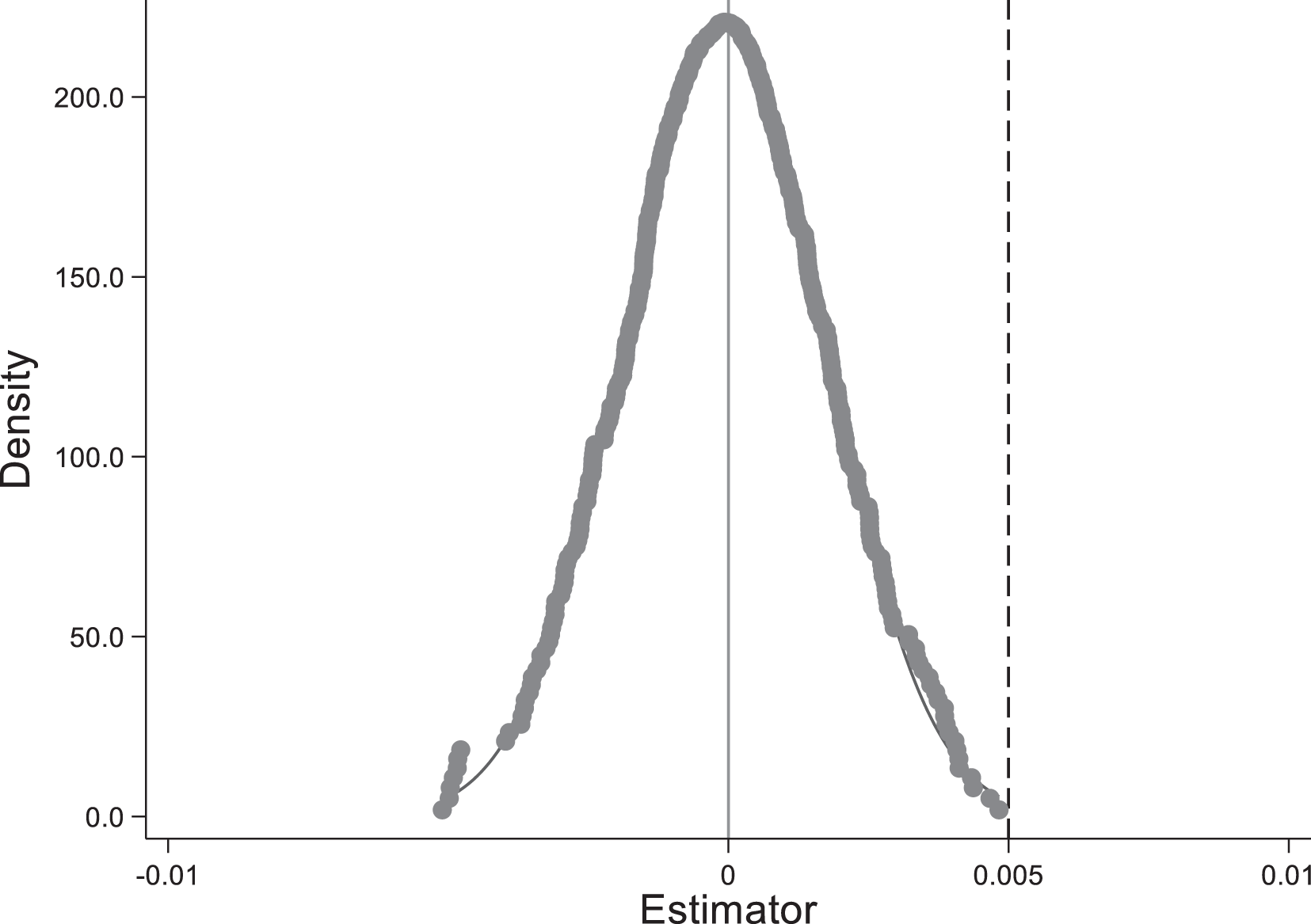

To further verify whether the effect of PFTZs on LGQ is affected by other unobserved random factors and other policies, we conduct a counterfactual event by randomly selecting experimental provinces and obtain a virtual coefficient, and this process of random sampling and estimation was repeated 500 times. The distribution of the virtual coefficients is reported in Figure 4. The coefficients are mainly clustered around the value of 0 and are normally distributed. The actual coefficient (0.005) significantly differs from the estimate obtained from the placebo test, indicating that the previous conclusions are unlikely to be driven by chance.

Figure 4. Results of placebo test.

4.2.3 Eliminate other Policy Interference

The time span of the data in this study is from 2004 to 2020. The Shanghai PFTZ was first established in 2013, coinciding with the proposal of the One Belt One Road (OBOR). In 2016, the strategy of the Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB) was put forward. These regional strategies will affect the LGQ, thereby causing interference with the empirical results. To control for this impact, dummy variables for the OBOR and the strategy of the YREB are introduced into the baseline model. The results are presented in columns 3 and 4 of Table 4, and the coefficients of PFTZ are consistent with the previous. It can be seen that the impact of PFTZs on LGQ does not suffer from interference from other policies.

4.2.4 Change in PFTZ Variable Construction

The previous section utilizes the PFTZ dummy variable. Here, we select the PFTZ area (PFTZ_new) as a new PFTZ variable for reestimation. As shown in column 5 of Table 4, the coefficient of PFTZ_new is significantly positive, which shows that the estimation results do not change due to the change in the construction of the core variable.

4.2.5 Change Estimate Model

Considering the possible problem of spatial correlation among provinces, we use feasible generalized least squares estimation (FGLS) to conduct robustness tests. The results are reported in column 6 of Table 4: The coefficient of PFTZ is significantly positive, indicating that the results do not change due to a change in the estimate model.

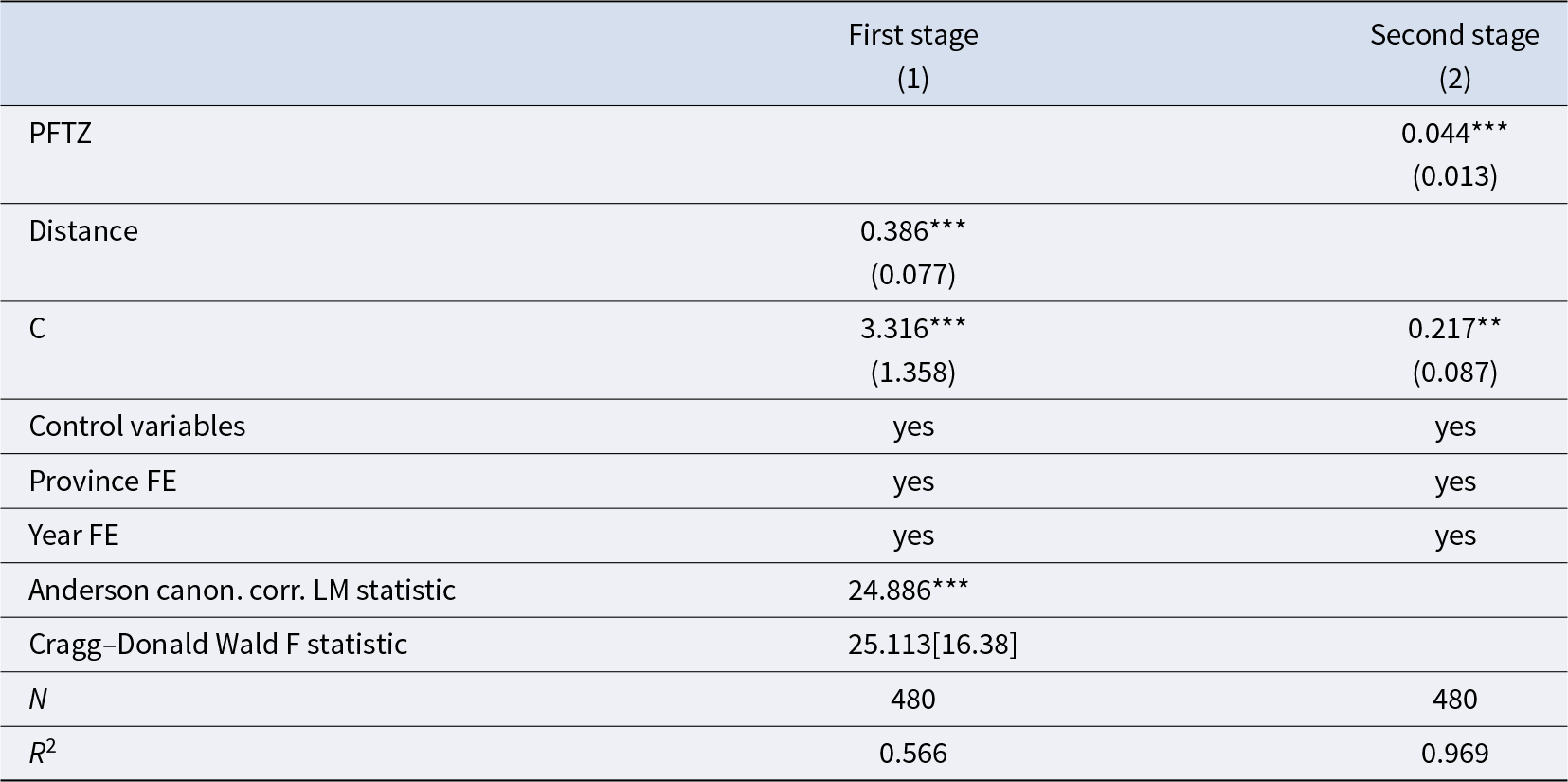

4.3 Endogeneity Test

Considering that the location of PFTZs may not be random, a two-way causal relationship might exist between PFTZ and LGQ, and the potential endogeneity may lead to biased estimation results. Therefore, the ratio of road density along the route to the distance from each capital to the coastline (Distance) is chosen as the instrumental variable. The main reasons are that PFTZs are located in the open system innovation test, and provinces with a high degree of openness have a higher probability of setting up a PFTZ, which is in line with the assumption of instrumental variable correlation. The geographical characteristics of each province do not directly affect LGQ, which is consistent with the instrumental variable exogeneity hypothesis. The results are reported in Table 6. The Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic surpasses the critical value of the Stock–Yogo weak instrument test at the 10% significance level, rejecting the original hypothesis of weak instrumental variables. Therefore, the instrumental variable is reasonable. The second-stage estimation results in column 2 show that the coefficients of PFTZ are significantly positive, confirming that the results are robust.

Table 6. Results of endogeneity test

4.4 Heterogeneity Analysis

Due to the different initial endowments and functional positioning of PFTZs in different regions and batches, their impacts on LGQ may differ. Therefore, this study will analyze from two dimensions: geographical location and establishment batch.

According to the different geographical locations, PFTZs in provinces adjoining the coastline are classified as coastal-type PFTZs, and PFTZs in provinces adjoining the national border are classified as border-type PFTZs.Footnote 1 From column 2 in Table 7, it can be seen that, compared with inland provinces, PFTZs in coastal provinces have limited effects on improving LGQ, while PFTZs in border provinces have a more significant impact on improving LGQ. This may be because coastal provinces generally have a higher degree of foreign trade dependence while border provinces have a relatively lower foreign trade dependence. The effectiveness of local governance will be lowered by a significant reliance on international trade. Border provinces have a relatively weak foundation for development and resource endowment, and the driving structure for promoting LGQ is limited. PFTZs have brought a new impetus for improving LGQ in border provinces, compensating for the insufficient endowment of factors and geographical location. PFTZs in border provinces are used to accomplish specific regional cooperation; for example, Guangxi PFTZ focuses on building a China–ASEAN information post and Heilongjiang PFTZ deepens cooperation with Russia.

Table 7. Results of heterogeneity analysis

According to the different approval times for PFTZs, PFTZs are divided into four batches.Footnote 2 The coefficients of the interaction terms between each batch and PFTZ are significantly negative, indicating a significant weakening of the subsequent promotion effect of PFTZs on LGQ. This may be related to the fact that the Shanghai PFTZ, as in the first batch of PFTZs, bears the national strategic priority tag and receives greater support. Consequently, its role in enhancing government efficiency is more significant. In contrast, the policy intensity of the second, third, and fourth batches of PFTZs is relatively lower, and institutional innovation has a long-term development effect. However, in the short term, there is a lag effect, leading to a decline in the promotion effect in the short term.

4.4 Mechanism Analysis

As seen in columns 1 and 2 of Table 8, PFTZs can improve LGQ through the institutional spillover effect. By introducing a series of market-oriented reform measures and policy innovations in PFTZs, including the pre-access national treatment, negative list system, international trade ‘single window’, tax preferences, and innovative financial policies, these policies involving market-oriented reforms can drive local governments to reform and optimize institutions, and strengthen common institutional recognition and cooperation. This positive impact has a policy demonstration effect and will gradually diffuse to surrounding areas, producing an institutional spillover effect. In addition, replicating and promoting innovative experiences in PFTZs benefit local governments by producing a more complete governance framework. Furthermore, the construction of PFTZs often involves multiparty cooperation and exchange, promoting the institutional construction and governance capabilities of local governments by sharing experiences.

Table 8. Results of the mechanism

As seen in columns 3 and 4 of Table 8, PFTZs can enhance LGQ through the factor allocation effect. The policy and institutional advantages of PFTZs attract many enterprises to settle in them. The rationalization of production factors between different departments and the improvement of the industrial chain require the guidance and management of local governments. This will enhance local government resource allocation and utility maximization to enhance the targeted and adaptive nature of local government policies. PFTZs expand the opening of industrial sectors, accelerate the flow, and coordinate the development of various factors, further enhancing LGQ.

As seen in columns 5 and 6 of Table 8, the talent agglomeration effect of PFTZs can significantly improve LGQ. The talent introduction policy of PFTZs can attract high-end talents, and its superior business environment can attract high-end industries to gather in the host, creating high value-added employment and attracting more high-end talents. The advanced management concepts and methods of high-end talent can enhance LGQ through talent exchange and interdisciplinary cooperation.

4.5 The Substitute Effect of FDI Spillover

PFTZs provide a platform for local governments to explore new ways of opening up, driving local government reforms and strengthening the promoting effect of opening up on LGQ. The interaction term (PFTZ×FDI) is introduced into the model to identify the substitute effect of FDI spillover. The FDI spillover (FDI) equals the average scale of foreign industrial enterprises, measured by the ratio of the total assets to the number of industrial enterprises with foreign investment from foreign, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwanese investors. The data are derived from the China Statistical Yearbook and China Industrial Statistical Yearbook from 2005 to 2021.

As seen in columns 1 and 2 of Table 9, the coefficients of FDI are significantly positive, and the coefficient of PFTZ×FDI is significantly negative. This suggests that PFTZs can weaken the FDI spillover effect on LGQ. This may be because increasing FDI leads to a significant spillover effect on LGQ, and PFTZs form the substitution for FDI spillover effect on LGQ. In addition, PFTZs would intensify local government competition for FDI, and this, combined with soft budget constraints, would lead to a noticeable weakening of the FDI spillover effect on LGQ.

Table 9. Results of the substitute effect of FDI spillover

4.6 The Distorting Effect of Economic Growth Pressure

PFTZs are not a policy vacuum of the past but highlands of institutional innovation, which makes it difficult to promote short-term economic growth. Local governments tend to adjust the function of PFTZs to develop the local economy, thereby distorting the positive effects of PFTZs on LGQ. To examine the distorting effect of economic growth pressure, we refer to the approach of Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Li and Wang2023), this study uses the ratio of the provincial annual economic growth target of the past five-year moving average actual GDP growth rate to measure the economic growth pressure (press). The data come from various provincial government work reports over the years. The interaction term (PFTZ×press) is introduced to investigate the distorting effect of economic growth pressure. The results are reported in Table 10.

Table 10. Results of the distorting effect of economic growth pressure

The coefficient of the press is significantly positive, indicating that local governments can promote efficiency under certain economic growth pressures. The coefficient of PFTZ × press is significantly negative, indicating that economic growth pressure can weaken the role of PFTZs in improving LGQ. This could be because the pressure imposed by economic expansion usually implies resource scarcity and competitiveness, and local governments will leverage PFTZs to attract external resources and high-quality enterprises, optimize local resource allocation, and promote economic growth, thereby alleviating some economic growth pressure, which deviates from the institutional innovation positioning of PFTZs. Under economic growth pressure, local governments tend to manage and even intervene in local economies, leading to ‘government overstepping its authority’ and prioritizing resource allocation to short-term projects, which distorts the government spending structure.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1 Research Conclusions

Based on the panel data of 30 provinces in the Chinese mainland from 2004 to 2020, the multi-period DID method was applied to analyze the impact of PFTZs on LGQ. The findings show that:

First, PFTZs can significantly promote LGQ, and this conclusion remains valid after numerous robustness tests. Compared with non-border and coastal provinces, PFTZs in border and inland provinces significantly improve LGQ. Compared with the first batch of established PFTZs, the subsequent establishment of PFTZs has a weaker promotion effect.

Second, PFTZs promote LGQ through the institutional spillover effect, factor allocation effect, and talent agglomeration effect.

Third, PFTZs can weaken the FDI spillover effect on LGQ, and economic growth pressure can distort the promotion effect of PFTZs on LGQ.

5.2 Policy Implications

PFTZs are not only pilot zones for regional economic development but also important hands for deepening reform and opening up, promoting the transformation of government functions, optimizing resource allocation, and building a modernized industrial system.

First, the central government should weaken the assessment of economic growth targets and return to the original functions of the PFTZ. It should summarize the successful experience of PFTZs, strengthen exchanges and learning among local governments, and promote regional cooperation and information sharing.

Second, given the spillover effect of PFTZs, local governments should be encouraged to improve the quality of public services, strengthen interregional cooperation, realize the sharing of public service resources, and narrow the regional development gap.

Third, relying on the development plan of PFTZs, PFTZs should focus on the development of high-tech industries and headquarters economies, promote upstream and downstream cooperation in the industrial chain, and form a modernized and globalized industrial system with high resource efficiency and strong regional linkage.

5.3 Prospects for Further Research

This study analyzed the impact of PFTZs on LGQ at the macro level by constructing a comprehensive indicator to evaluate LGQ. However, the study focused only on the overall impact of PFTZ on LGQ without revealing the micromechanisms through which PFTZs promote LGQ. Future research could explore the impact of PFTZs on the operational efficiency of local governments in prefecture-level or county-level dimensions, as well as their effects on expenditure scale, structure, and efficiency. This would comprehensively reveal the influence of PFTZs on local governments.

Funding

This work was supported by the Youth Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22CJY051) and Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education Graduate Innovation Fund Project (Grant No.: YC2024-S278).