Introduction

The COVID‐19 pandemic was a crisis that was massive in scale, rapid in pace and global in scope. It confronted governments around the world with the manifold challenges of making sense of a volatile situation, engaging in effective planning and implementation of emergency measures, and, above all, communicating with anxious populations. Since effective crisis management and the survival of governments hinge at least partly on how executives communicate during a crisis (Boin et al., Reference Boin, 't Hart and McConnell2009), political leaders were forced to think about how to craft clear, consistent and compelling messages.

According to previous studies (e.g. Eisele et al., Reference Eisele, Tolochko and Boomgaarden2022; Witte & Allen, Reference Witte and Allen2000), threat language can be a crucial communication tool that allows governments to raise public awareness and enhance compliance with emergency measures and thus ensure effective crisis management. A case in point is the dire warning of Austria's Chancellor Sebastian Kurz at the outset of the pandemic in March 2020 that ‘everyone will know someone who died of Corona’ (Kleine Zeitung, 2020).Footnote 1 At the same time, however, the use of threat language can also be a risky tool as its extensive use can make governments appear overwhelmed by a crisis. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that during the COVID‐19 crisis governments used references to threats strategically in some speeches but not in others.

While the existing literature on political crisis communication during the COVID‐19 pandemic has produced valuable insights into rhetorical strategies (e.g. Montiel et al., Reference Montiel, Uyheng and Paz2021), the use of metaphors (e.g. Seixas, Reference Seixas2021) and frames (e.g. Lilleker et al., Reference Lilleker, Coman, Gregor and Novelli2021; Wodak, Reference Wodak2021) or the choice of channels such as Facebook or Twitter (e.g. Box‐Steffensmeier & Moses, Reference Box‐Steffensmeier and Moses2021; Rufai & Bunce, Reference Rufai and Bunce2020), it has not systematically analysed the use of threat language during the pandemic. In particular, we still know very little about who used threat language and in which contexts. Addressing this gap in the literature, our article investigates the question of which factors influence the likelihood of threat language in the crisis communication of governments.

To answer this question from a comparative perspective, we make use of government communication during the COVID‐19 pandemic. We argue that individual‐level factors (politician vs. non‐politician and gender) shape the likelihood of including threat language and that contextual factors (time and subject area) determine the probability with which speakers employ this communication tool. In detail, we posit that politicians are more likely to use threat language than non‐politicians and men rather than women. Moreover, we expect that the subject areas addressed affect political actors' willingness to use threat language. Since in the early phase of the pandemic, it was first and foremost regarded as a health crisis, we propose that threat language is most likely to be used in the subject area of the health system. Furthermore, to account for the multi‐dimensionality of the crisis (Boin et al., Reference Boin, McConnell and 't Hart2021), we postulate that threat language becomes more diverse as the crisis evolves.

To test these propositions, we draw on a unique dataset of 1108 televised press conferences held by 433 actors in 17 OECD countries and three US states in the initial phase of the pandemic in early 2020 (Hayek et al., Reference Hayek, Dingler, Senn, Schwaderer, Kraxberger and Ragheb2023). This initial phase covers the period from the first public address of governments on COVID‐19 to the first address in which governments announced the relaxation of COVID‐related measures. We focus on televised press conferences because they are the preferred means of communication at times of crises (see Craig, Reference Craig2016; Ekström & Eriksson, Reference Ekström, Eriksson, Wodak and Forchter2017). For this paper, we build on methods of quantitative text analysis that have proven to be reliable tools in the analysis of governmental crisis communication (see, e.g., Traber et al., Reference Traber, Schoonvelde and Schumacher2020, for a similar approach). In the first step, we employ a dictionary approach to identify threat language and use this measure to determine how being a politician and gender affects the likelihood of using threat language (Galantino, Reference Galantino2022) by means of a multi‐level analysis. Second, we use topic models to investigate the subject areas in which threat language was used.

Our results show that – contrary to our expectations – politicians and non‐politicians are equally likely to use threat language. As proposed, however, men are slightly more prone to make use of threat language than women. Further, in the subject areas of the health system and public management, speakers are most likely to use references to threats compared to all other contexts (e.g. economy, security). In addition, as expected, the usage of threat language has diversified over time as the crisis has become increasingly multi‐dimensional in the initial phase of the pandemic.

Overall, our findings imply that crisis communication across countries is more homogeneous than previously indicated by the literature. Political actors chose to communicate in a similar manner once facing a comparable challenge. In the context of the unprecedented COVID‐19 pandemic, governments tended to adapt their communication strategies depending on which area of official life was most affected rather than sticking to a pre‐defined communication strategy.

Individual‐level and context‐level factors

To analyse and evaluate public political crisis communication, Eisele et al. (Reference Eisele, Tolochko and Boomgaarden2022) propose a framework that includes four dimensions: accessibility of information, allaying fears, accommodation of the public and alignment. Since fear appeal messages are one of the most important tools to alter citizens' behaviour – a major goal to effectively manage a health crisis – we focus on this dimension only. And, we adopt a broad definition of threat (see Battistelli & Galantino, Reference Battistelli and Galantino2018; Galantino, Reference Galantino2022). Instead of limiting our definition to threats alone, we also include communication that relates to the dangers and risks posed by the pandemic. This approach allows us to capture that the meaning, relevance and harmfulness of threat, risk or danger varies according to the social context and to the role of those who make claims (Battistelli & Galantino, Reference Battistelli and Galantino2018). For instance, in the case of infectious diseases such as ‘mad cow disease’ or SARS, media narratives and public opinion were very diverse ranging from a ‘danger independent of human decisions’ to ‘an enemy that threatened us’ depending on the circumstances (see Battistelli & Galantino, Reference Battistelli and Galantino2018, p. 72, for an elaboration).

To gain public attention and mobilize people, the language used is crucial. Research demonstrates that citizens' compliance with measures imposed by governments and the confidence of the wider public in crisis‐coping mechanisms can be influenced by the language with which the population is addressed (Burdett, Reference Burdett1999; McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Cunningham, Reynolds and Matthews‐Smith2020). In the context of a health crisis like a pandemic, threat language can increase people's perception of the severity and susceptibility of the health issue and in turn lead to behavioural change (see Stolow et al., Reference Stolow, Moses, Lederer and Carter2020). Thus, threat language is a means employed by politicians, experts and health professionals in governments and beyond to persuade the public to adapt their behaviour to the respective situation (e.g. stay at home) (see Stolow et al., Reference Stolow, Moses, Lederer and Carter2020). At the same time, however, overusing threat language can backfire, because it conveys a sense of overload and loss of control (Eisele et al., Reference Eisele, Tolochko and Boomgaarden2022; Falkheimer & Heide, Reference Falkheimer and Heide2010).

We expect that not all government members utilize this communication tool equally, since personal factors affect the style of leadership, communication and the decisions leaders make (Carney et al., Reference Carney, Jost, Gosling and Potter2008; Schoonvelde et al., Reference Schoonvelde, Brosius, Schumacher and Bakker2019). Individual‐level factors, for instance, can determine whether leaders are open to seeking advice or information, changing their strategies and even whether they are likely to use their powers (Dyson, Reference Dyson2006; Kaarbo, Reference Kaarbo1997; Kaarbo & Hermann, Reference Kaarbo and Hermann1998; van Esch & Swinkels, Reference van Esch and Swinkels2015). Based on these considerations, we argue that individual‐level factors also shape how governments communicated during the early phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic. In detail, we expect that the role of a speaker as a politician and the gender of the speaker shape differences in the likelihood of threat language in the COVID‐related communication of governments. Furthermore, accounting for the multi‐faceted nature of the crisis, we expect that not all threat language was directed towards the same subject and that contextual factors influence crisis communication (see, e.g., Traber et al., Reference Traber, Schoonvelde and Schumacher2020). We argue that as the crisis continued, communication moved from health threats to threats against the society and the nation as a whole.

How speakers' role and gender shape threat language

Even though the COVID‐19 pandemic hit most countries worldwide, the way governments tackled it in their communication strategies varied to a large extent. For example, some countries such as Sweden (Nygren & Olofsson, Reference Nygren and Olofsson2020; Petridou, Reference Petridou2020) deliberately only chose to have health officials communicate their COVID‐19 measures. In a complex situation such as the pandemic, politicians ‘took advice from their experts, but personalized command over decision making and public communication’ (Lilleker et al., Reference Lilleker, Coman, Gregor and Novelli2021, p. 337). Health experts enjoy high levels of public trust because they are perceived as competent and objective (Warren & Lofstedt, Reference Warren and Lofstedt2022). As scientists or bureaucrats, rather than active political actors, their communication serves more of a rational function to legitimize the uncertainty with regard to scientific assessment of the pandemic situation. Hence, they have an incentive to objectively discuss and communicate scientific knowledge about the pandemic at hand.

By contrast, governments and politicians whose survival in office depends on the support of voters have to perform a tightrope act with the use of emotions in their communication. On the one hand, they are expected to allay fears about the pandemic in order to convince the public that they can protect them and effectively navigate through this difficult situation. On the other hand, they have to use threat language and induce negative emotions to convey a sense of emergency and to ensure compliance with countermeasures (Boin et al., Reference Boin, 't Hart, Stern and Sundelius2005; Eisele et al., Reference Eisele, Tolochko and Boomgaarden2022; Heath, Reference Heath, Coombs and Holladay2010).

In line with this argumentation, a previous study on H1N1 in the Netherlands, for instance, finds that many citizens believed that the government exaggerated the situation during some periods (van der Weerd et al., Reference van der Weerd, Timmermans, Beaujean, Oudhoff and van Steenbergen2011). Based on the idea that politicians rely on citizens' compliance with containment measures to ensure effective crisis management, we expect that they are also more likely to use threat language.

-

• H1a: Threat language is more likely to be used by politicians than by non‐politicians.

Beyond the formal role of a politician, we argue that the gender of a speaker affects crisis communication with women less prone to use threat language than men. Two mechanisms might account for gendered communication patterns. First, existing literature indicates that communication differences might stem from socialization along the lines of gender stereotypes. These stylized expectations about each gender associate women with the role of the caretaker in the private sphere and men with the organization of political life. In line with the abilities crucial to succeed in these roles, women are thought to exhibit soft traits (e.g. warmth, sensitivity, passion and orientation towards compromise in conflict situations) whereas men should demonstrate strength, competitiveness, assertiveness, agency and aggression (Eagly & Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002). Even today stereotypes inform beliefs about which behavioural patterns are accepted for each gender. As recent research demonstrates they in some cases even become more important, for instance, with regard to expectations about women's behaviour (e.g. honesty, politeness, ability to handle people well) (Eagly et al., Reference Eagly, Nater, Miller, Kaufmann and Sczesny2020). Internalization of these stereotypical expectations through socialization should result in different communication patterns between men and women.

Second, in addition to internalization, women might strategically choose to communicate in a more positive and empathetic manner. When acting in ways that are not in line with gender stereotypical roles, women face prejudices about their competence according to the role incongruency hypothesis (Eagly & Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002). Thus, women leaders might deliberately decide to use certain types of communication tools or language that have proven to be beneficial for them. A large number of studies substantiate the idea that women should be less likely to use threat language in their communication than men even in highly political contexts (Maiorescu, Reference Maiorescu2016; Tannen, Reference Tannen2007). In parliamentary debates, for example, men behave more dominantly than women (Koppensteiner et al., Reference Koppensteiner, Stephan and Jäschke2016), stand up and shout more frequently, are more combative and aggressive (Tolleson‐Rinehart, Reference Tolleson‐Rinehart and Carroll2001), tend to make more personal attacks (Kathlene, Reference Kathlene1994) and interrupt more often (Shaw, Reference Shaw2000). With regard to the language used, men employ more adversarial language (Hargrave & Langengen, Reference Hargrave and Langengen2020) while women MPs are more likely to use positive emotive words emphasizing social relations (Wäckerle & Silva, Reference Wäckerle and Silva2023) and are less negative (Haselmayer et al., Reference Haselmayer, Dingler and Jenny2022). In a similar vein, a case study on the crisis communication of New Zealand's Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, during the COVID‐19 pandemic finds that her communication evolved from an initially decisive and reinforcing approach towards an empathetic one, emphasizing the shared experience of the crisis and solidarity (McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Cunningham, Reynolds and Matthews‐Smith2020). Overall, based on these considerations, it is reasonable to expect that women are more reluctant than men to focus on scenarios that include threat appraisals in their communication.

-

• H1b: Threat language is more likely to be used by men than by women.

How context shapes threat language

Beyond individual‐level factors, we expect that the content of the policy areas discussed affects the likelihood with which threat language is employed by politicians. In the very beginning, the COVID‐19 pandemic started out as a public health crisis. The first and most obvious threat posed by the COVID‐19 pandemic was the heightened health risk of any individual contracting the virus (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Lueders, Sankaran and Politi2021; Boin et al., Reference Boin, McConnell and 't Hart2021). Protecting citizens who were at a higher risk of falling seriously ill became a focal point of the measures proposed by experts and governments alike (Boin et al., Reference Boin, McConnell and 't Hart2021). Thus, in this early phase, government communication centred first and foremost on informing the public of the current state of the crisis as well as on justifying imposed measures that impacted the lifestyle of citizens. Particularly, in the early phase, heads of governments depicted the COVID pandemic as a health crisis since health systems across the world faced unprecedented and unpredictable challenges. Governments were facing the possible collapse of the health care system as hospitals were overwhelmed with patients (Woods et al., Reference Woods, Schertzer, Greenfeld, Hughes and Miller‐Idriss2020). This made providing financial aid and medical supplies to hospitals a top priority for governments alongside the enforcement of containment measures. The situation in hospitals and the possibility of collapsing health infrastructures were often used to justify these strict containment measures. Citizens were asked to follow the rules in order to avoid risking their own health, but also the health of others, and, more importantly, to protect the overall system. Based on these considerations, we argue that threat language was mostly used in subject areas related to the health system and public management (e.g. announcement of containment measures, etc.).

-

• H2a: Threat language is more likely to be used in the context of the health system and public management than in other contexts.

As the crisis progressed and especially with rising numbers of infections, threat language became increasingly diverse for three reasons. First, what started out as an attempt to maintain critical health care on a national scale quickly developed into a substantial economic crisis, triggered by the closure of businesses and subsequent rise in unemployment levels (Pereira & Oliveira, Reference Pereira and Oliveira2020). Second, governments perceived the unfolding crisis to be an exogenous threat to national security and in turn concentrated their response on the deployment of the military and tightening border security (Reich & Dombrowski, Reference Reich and Dombrowski2020). These developments led to the rise of what scholars call ‘COVID‐related nationalism’ or ‘nationalism of pandemics’ more broadly, which is characterized by a tendency to think primarily within the national context in battling the pandemic. This shift can, for example, be observed in the sharpening of anti‐immigration sentiment among individuals amid the outbreak of the pandemic (Esses et al., Reference Esses, Sutter, Bouchard, Choi and Denice2021; Nossem, Reference Nossem2020). Third, despite these trends towards a focus on threats on the national level, border closures and the attempt to fight the virus nationally, it became clear that the pandemic required, at least partly, addressing on the supranational or global level as demonstrated, for example, by multi‐causal disturbances in the supply chains of food, medicine and other essential products (Pereira & Oliveira, Reference Pereira and Oliveira2020).

Overall, within weeks, multiple governmental entities with vastly differing functions were trying to mount a collective crisis response (Boin et al., Reference Boin, McConnell and 't Hart2021). When, in the beginning, concrete dangers of COVID‐19 were mostly felt by individual citizens across many different areas of life (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Lueders, Sankaran and Politi2021), threat language became increasingly diversified over time. The COVID‐19 pandemic has affected nearly every aspect of modern society, the global economy, and the political realities of many countries. What started as a crisis limited to individual health and the provision of healthcare quickly ballooned into an all‐encompassing, existential threat (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Lueders, Sankaran and Politi2021; Boin et al., Reference Boin, McConnell and 't Hart2021).

-

• H2b: The longer the crisis lasted, the more diverse did threat language become.

Data, methods and operationalization

To test these hypotheses, we study government crisis communication in 17 OECD countries (Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Turkey and the United Kingdom), as well as three US states (New York, Vermont and Iowa). With this country selection, our original dataset (Hayek et al., Reference Hayek, Dingler, Senn, Schwaderer, Kraxberger and Ragheb2023) is characterized by broad variation in the key variables of interest. Since institutional and socio‐economic contexts across the countries in the sample remain comparable, they provide ideal testing grounds for a large‐scale comparison and broad generalization potential. For the analysis, we draw on transcripts of all televised speeches and press conferences of governments during the immediate phase of the COVID‐19 crisis. For each country, the sampling period spans from the first public address held on COVID‐19 up to the first public address in which a government announced a relaxation of the restrictive measures that had been put in place to contain the virus. Since we focus on this initial phase of the crisis, which is crucial for crisis communication (Coombs, Reference Coombs2022), rather than the whole period of the pandemic, and since we are also interested in the likelihood with which governments use this type of communication, we do not restrict the analysis to singular events but to all televised government speeches and press conferences during the initial phase (for a detail on the sampling period and the number of press conferences by country, see Table A1 in the Online Appendix.). These press conferences usually consisted of one or more introductory speeches, followed by a question‐and‐answer session with journalists (Ekström & Eriksson, Reference Ekström, Eriksson, Wodak and Forchter2017).Footnote 2

In total, 1108 press conferences and televised addresses were held in the initial phase of the pandemic between January and July 2020. The number of press conferences varies strongly between countries, ranging from nine press conferences in the Czech Republic to 300 in the Republic of Korea.Footnote 3 Video recordings of press conferences were downloaded and then transcribed using a combination of Speech2Text recognition and manual transcription proofreading. The transcripts were then translated by machine translations (using DeepL and Google Neural Machine Translation) and post‐edited by professional human translators. This combination of automatic tools and human expertise ensures a high quality and reliability of the data. Each of the resulting 1108 transcripts – one transcript for each event – was then split into segments based on individual speakers present during a press conference. The initial dataset includes 2507 segments in English (Hayek et al., Reference Hayek, Dingler, Senn, Schwaderer, Kraxberger and Ragheb2023). Each segment was then assigned to its corresponding speaker; overall, we have 433 different actors speaking at press conferences. For our analysis, the speaker segments were split into 90,344 sub‐segments of 23 words, creating the final aggregated dataset with sub‐segments as the chosen unit of analysis. This allows for a more fine‐grained identification of discussed topics. In order to accommodate the inherent differences in sentence structures between spoken word in press conferences and written text, the sub‐segments were compiled by taking into consideration the average sentence length prevalent in the spoken discourse in our data. This approach enables a more accurate representation of the spoken content and enhances the applicability of the analysis to the specific context of press conferences.

As a first step, to investigate when governments talk about threats, we determined the content of all sub‐segments. The goal is to identify the underlying topic of every given text unit for which we expand on existing approaches to text analysis in crisis communication research (see, e.g., Traber et al., Reference Traber, Schoonvelde and Schumacher2020, for a similar approach). In terms of topics, we focus on the targeted groups as well as COVID‐related subject areas. To assign subject area and target to the respective sub‐segments, we followed a semi‐supervised approach, that allows for a classification of text into predefined groups (Galantino, Reference Galantino2022). Our analysis is based on a latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), a commonly used topic model in social science research. However, unsupervised topic models tend to lack interpretability as they often do not correspond to established theoretical concepts (Watanabe & Baturo, Reference Watanabe and Baturo2023). To get around this issue that is especially prevalent in the unique context of pandemic communication, we rely on ex ante mapping of our concepts of targets and subject areas to the algorithm through seed words before fitting the models. The use of a Seeded‐LDA allows us to obtain topic‐specific models, that are theoretically grounded and correspond to our data (Watanabe & Baturo, Reference Watanabe and Baturo2023). Based on a theory‐driven collection of groups for targets and subject areas, we constructed two dictionaries with predefined groups (see Tables 2 and 3 in the Online Appendix) to assign seed words to each group. Each category captures a prevailing topic in governmental communication regarding the COVID‐19 pandemic, while each target represents an entity frequently cited as being affected by the pandemic. For this step, we first manually selected the most prevalent words from the transcripts, representing each of the groups by thoroughly reviewing the transcripts. As Seeded‐LDAs often suffer from over‐fitting, leading to topics that may not accurately represent the actual concepts present in the texts, we supplement the dictionaries with additional seed words to unveil underlying descriptions of these categories: the manually selected keywords for each group were used as a basis for word embeddings to identify keywords that were used in the semantic context of the corresponding categories. These were then assigned as meaningful keywords to the respective categories. Although one possible strategy might entail using synonyms, it's crucial to recognize the potential variation in meaning that can occur when true synonyms are not present. With this approach, we managed to capture a broader understanding of concepts that linked to the specific context of the COVID‐19 pandemic. The threshold for semantic similarity was chosen individually for each category in the dictionary and manually evaluated. The resulting dictionary acted as the basis for the Seeded‐LDA for Topic Modeling using the R package quanteda (Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Watanabe, Wang, Perry, Lauderdale, Gruber and Lowe2021) to assign each of the text modules to a subject area. While we try to minimize the limitations of Seeded‐LDAs, it is important to acknowledge that this semi‐supervised approach may not be as effective in mitigating fitting biases compared to manual coding. Nevertheless, we have chosen to adopt this approach in order to handle a substantial volume of data efficiently.

In a second step, in order to operationalize our dependent variable, threat, we capture if a sub‐segment includes a threat or not. To identify notions of threat, we examined the sub‐segments, based on the keywords drawing on the conceptual and empirical work by Battistelli and Galantino (Reference Battistelli and Galantino2018) and Galantino (Reference Galantino2022). Building on their approach, we use an English‐language dictionary including nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs and derivatives of ‘risk’, ‘danger’ and ‘threat’ (Galantino, Reference Galantino2022, p. 336). In this subset, we identified 1986 sub‐segments referring to a threat, risk or danger. From our data, threat language includes examples such as ‘If you don't follow the guidance, you will be endangering the lives of your own friends, family and loved ones’ (Priti Patel, 10 April 2020) or, ‘The better we follow the rules, the faster we can curb the course of the epidemic and completely eliminate the threat. Otherwise, it is inevitable that we will fall into the situation of some countries that we are following with sadness today’ (Recep Tayyip Erdoǧan, 3 April 2020).

Having identified the topic of a sub‐segment and whether it includes a keyword indicating a threat, we ran a second Seeded‐LDA, based on the dictionary on targets. This automated classification of the sub‐segments into seven distinct groups was based on the subset of sub‐segments containing threat language.

To capture variations between speakers on the individual level, we collected biographic data for all speakers using information that was publicly available on official government websites or CVs. Our independent variables include the professional role of the speaker as well as their sex. The politician variable indicates whether the speaker is a politician and gender_men measures whether the speaker is a man (1) or not (0).

As controls, we include a variable accounting for whether a speaker is a health expert since we would expect that experts use less threat language than non‐experts. This information was retrieved from official CVs, government websites or descriptions attached to the press conferences. Moreover, the variable coalition governments specify whether two or more parties were in power or only a single party as we assume that the communication behaviour of coalition members is less likely to incorporate threat language since coalition members have a higher interest in showing unity and control over the situation (Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2008).

Further, we account for the epidemiological situation as well as the capacity of the health system as we expect that threat language should become more likely as the severity of the crisis and its impact on the functioning of the health system becomes more pronounced. Therefore, we include publicly available information on the epidemiological situation in the country. This comprises the COVID‐19 death rates per 100,000 inhabitants, based on the death rates reported by the WHO (World Health Organization, 2021) and the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021) for countries and US states, respectively, as well as the population estimates provided by the OECD (OECD, 2021) and the US Census Bureau (United States Census Bureau, 2021), respectively. We also include the ICU occupancy in per cent taken from the data made available by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME, 2021). All these indicators have been measured on the day a press conference was held.

Results on factors determining the usage of threat language

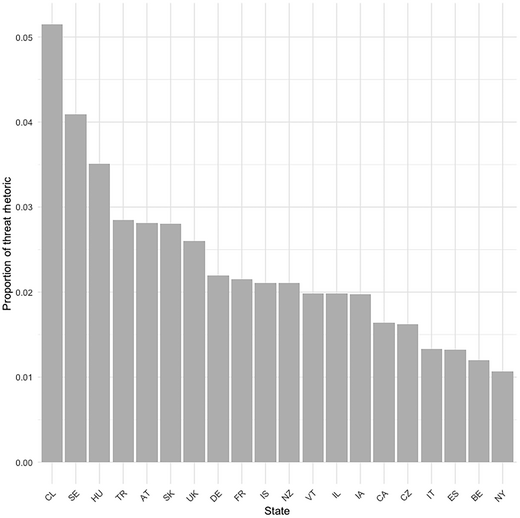

Starting with some descriptives, as Figure 1 shows, the average use of threat language by country varies to some extent. Chile is in the lead, with 4.8 per cent of all segments including the mention of a threat, risk or danger. On the other end of the spectrum, New York seems to have employed more non‐threatening language, despite having been affected by a rapidly increasing infection rate, only using threat rhetoric in about 0.9 per cent of all communication.

Figure 1. Speakers' average use of threat language by state.

On the one hand, the difference between states in the degree of emphasis placed on threats is probably a result of differing communication strategies of governments – some focusing on the problems and the risk of not addressing them, others adopting a more pragmatic approach. On the other hand, it is important to note that our analysis detects the mention of several different types of threats, making it necessary to look into each one in more detail. Therefore, the variations in the use of threat‐related messages in crisis communication cannot be explained by one factor only. A deeper dive into the content of these messages is necessary.

In total, 434 different speakers appeared in press conferences across 17 countries and three US states, making 2507 statements. However, we found stark differences between countries in terms of the number of speakers at press conferences as well as the roles they assumed. Canada, for example, was represented solely by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and is situated at the low end of the spectrum, next to Turkey (five speakers) and Chile (three speakers). Sweden, on the other hand, had a total of 57 different speakers appear in press conferences, closely followed by Austria with 51 speakers and Iceland with 48 speakers. Larger numbers of speakers do not necessitate more press conferences. As mentioned, Canada's prime minister held 44 press conferences on his own, which is just below the average of 55 press conferences, whereas the Czech Republic held only nine press conferences in the analysis time frame.

In terms of the individual speaker function, politicians (43.9 per cent) and health experts (29.27 per cent) made up the majority of the speakers, while in some countries journalists, business representatives as well as public and civil servants also addressed the public. With the exception of Canada and France, all governments also brought in health experts to address the public during press conferences. In Iowa, Iceland, New Zealand and South Korea, health experts even outnumbered politicians. Politicians are also mostly in the lead concerning the sheer volume of spoken content, barring New Zealand (67 per cent) and Iceland (65 per cent), where health experts somewhat predictably outperform politicians by a large margin. In contrast, the State of New York has given health experts the smallest share of public addresses with only around 0.2 per cent of spoken content, followed by Italy with 0.7 per cent and Austria with 4.4 per cent.

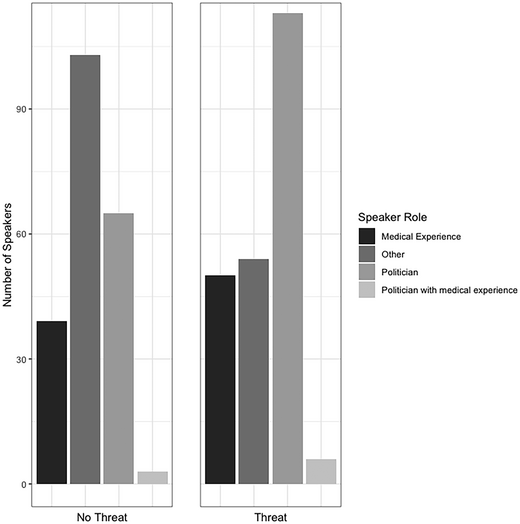

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of speakers between speech segments with and without mention of a threat. About 52 per cent of all speakers employ threat language in their addresses, of whom 50 per cent are politicians, and about 21.5 per cent are people with prior medical experience.

Figure 2. Use of threat language by speaker roles.

‘Threat’ represents speakers that used threat language at least once, and ‘No Threat’ represents speakers that never used threat language.

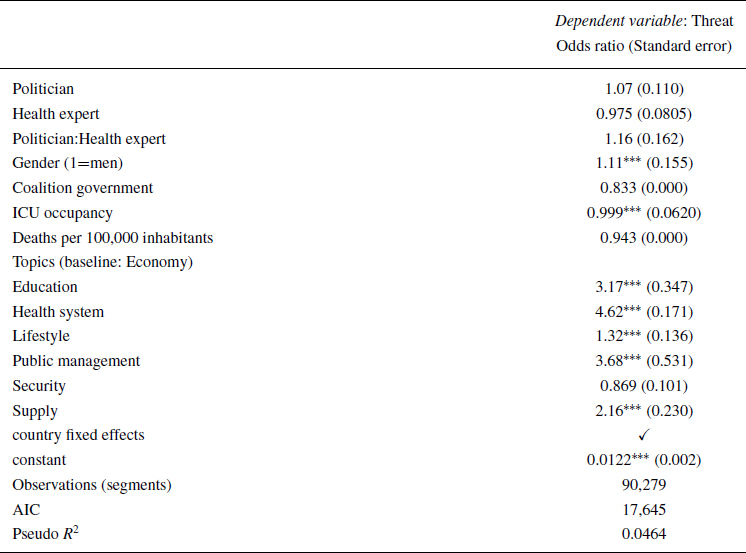

Turning to our logistic regression model with countries as fixed effects (Table 1), we examine the effects of individual‐level factors (H1a and H1b) and the effects of context (H2a and H2b).

Table 1. Logistic regression model: Threat likelihood

Abbreviations: AIC, Akaike information criterion; ICU, intensive care unit.

![]() $^{***}$

p

$^{***}$

p

![]() $<$0.01;

$<$0.01;

![]() $^{**}$p

$^{**}$p

![]() $<$0.05.

$<$0.05.

H1a expects politicians to be more likely to use threats than non‐politicians. The regression model (Table 1), however, shows that politicians are not any more prone to use threats in their statements than non‐politicians leading us to reject H1a. After all, extensively using threat language poses risks to the reputation of governments and their ability to handle the crisis as predicted by the literature (Eisele et al., Reference Eisele, Tolochko and Boomgaarden2022). Both, politicians and experts, seemingly were rather careful in their usage of threat language.

Beyond the role as politician, we posit men to be more prone to use threat language than women (H1b). As Table 1 shows, men are indeed significantly more likely to include threat language than women; however, the effect size is very small: Being a man increases the odds of using threat language by 15.8 per cent. This result is in line with previous research demonstrating that women are more likely to use positive emotive words (Wäckerle & Silva, Reference Wäckerle and Silva2023).

This is illustrated by New Zealand's Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, who emphasized the shared experience of the crisis and solidarity (McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Cunningham, Reynolds and Matthews‐Smith2020) in her communication. In a press conference held on 23 March 2020, for instance, Ardern's introductory remarks show this pattern of stating that there is a threat while adding a positive note of togetherness to the statement:

Like the rest of the world, we are facing the potential for devastating impacts from this virus. But, through decisive action, and through working together, we have a small window to get ahead of it. (Newshub, 2020)

By contrast, statements containing the most threat language were made primarily by men. A good example is a statement by Ardalan Shekarabi, Minister of Social Security in Sweden during a press conference on 23 April 2020 in which he said:

What we are seeing now is a dangerous cocktail of circumstances that risks increasing the risks of problem gambling and gambling addiction. Isolated people with high anxiety about their jobs and finances are a dangerous breeding ground for increased problem gambling. (O'Hagan, Reference O'Hagan2021)

With these findings, we can confirm Hypothesis 1b.

In addition to individual‐level factors, we expect the likelihood of threat language to vary across subject areas, with statements addressing the health system and public management most likely entailing references to threats. As the model in Table 1 shows, we can confirm Hypothesis 2a. In contrast to the reference area economy, all subject areas show a significantly higher effect on the likelihood of using threat language. Statements addressing the area of public management are 3.77 times more likely to include a threat, followed by the health system with a likelihood of 3.37.

This finding is not surprising, since speakers tended to stress the public health crisis, then follow up with a description of the solution or strategy in the form of public management plans. A good example is Sebastián Piñera's address at the Chilean press conference on 13 March 2020:

Dear fellow citizens: The Coronavirus emerged in China late last year, has spread rapidly around the world and is now the most serious threat to humanity in more than a century. […] [W]e must prepare to face the most difficult stages of this epidemic, which requires the unity and collaboration of all and always putting the health of Chileans as our main priority. As soon as we learned of the cases of Coronavirus in China, our government began to prepare to adequately deal with this disease and effectively protect the health of all Chileans. Thus, early in January, together with the Minister of Health, we formed a task force to take all the necessary measures and develop an Action Plan to adequately address the looming crisis. […] Dear fellow citizens, challenging times are coming in terms of health. […] In accordance with the Constitution, I have designated the Minister of Health as the Interministerial Coordinator of the Plan to Protect Chileans from the Coronavirus. […] Dear fellow citizens: I am fully confident that all Chileans will know how to face with unity and generosity this serious threat to the health of our citizens, whose protection is the main priority and concern of our Government and of this President. (Government of Chile, 2020)

As evident in this example, a health‐related threat appeal may go hand‐in‐hand with an outline of a managerial plan. Piñera starts by identifying a threat related to the health of citizens, then describes how the government has prepared to face that threat by mentioning a number of public management steps, and then concludes with another mention of the threat to public health before signing off. Picking a similar strategy, Rudolf Anschober (Austrian health minister at that time) justified the country's lockdown strategy by explaining the risks it aims to avoid:

We want to avoid a development like the one in Italy with all the political and democratic options for action that we have, and that is why we are also focusing on three strategic priorities […] first, concrete measures to reduce direct and immediate social contact and thus reduce the risk of infection […] (Bundeskanzleramt Österreich, 2020)

Turning to our control variables, health experts are not more likely to employ threat language than non‐health experts. The interaction effect between politicians and health experts does not reach conventional levels of significance either, showing that it does not matter whether a politician also has a background in health. Also, coalition governments are not more or less likely to use threat language. While death rates do not have a significant effect on a government's crisis communication, the situation of the health system does influence the threat language used: ICU occupancy has a small negative effect. Hence, as hospitals become closer to working at capacity, government communication is more likely to include threat language, however, speakers at the press conferences do seem to be more careful in their word choice as ICU occupancy becomes problematic. This is in line with the literature which suggests that threat language should be used carefully in order to avoid conveying a sense of overload and loss of control (Eisele et al., Reference Eisele, Tolochko and Boomgaarden2022; Falkheimer & Heide, Reference Falkheimer and Heide2010).

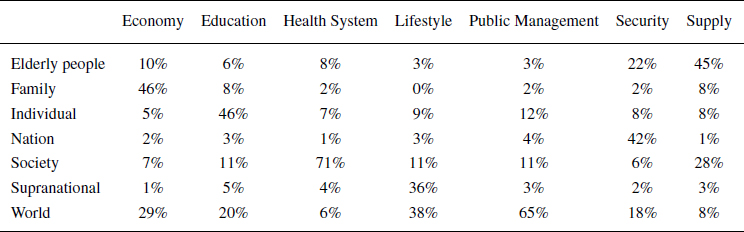

Table 2 shows subject areas by targets. Health threats were generally targeted mainly towards the society (71 per cent), while threats to the educational system were aimed at the individual (46 per cent). Additionally, economic threats were addressed overwhelmingly at families (46 per cent), while questions of threats to security were mainly discussed at the national level (42 per cent).

Table 2. Subject areas by targets

While most threat language was used towards more or less all targets, we see distinct spikes for certain targets and can confirm that there are significant differences between the targets that are addressed using threat language (

![]() $\chi ^2 = 2332$,

$\chi ^2 = 2332$,

![]() $p < 2.2e-16$).

$p < 2.2e-16$).

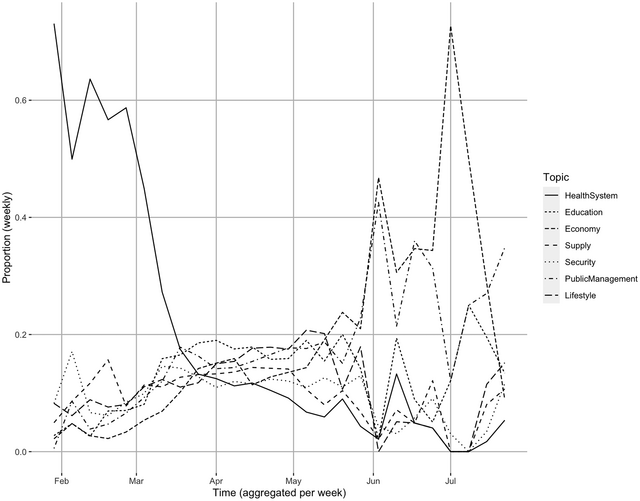

We argue that threat language would diversify as the pandemic progressed (H2b). Over time, the impact of the pandemic has increasingly spread to broader areas, which have been addressed in press conferences. Thus, at the beginning of the pandemic, when many countries had not yet experienced COVID‐19 cases and little was known about the direct impact of the virus, governments referred to those issues that were already concretely affected at that time (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Use of threat rhetoric by subject area over time.

What becomes immediately apparent is the initial emphasis on health risks and threats to the health care system. This threat scenario was picked up quickly by press conferences. However, we observe that disruptions in the daily life of the population as well as threats to the political and bureaucratic systems and education increasingly came into the focus of government communication. Information on health risks as well as the health system dominated press conferences at this stage since few people had actually been infected with COVID‐19 at the beginning of the pandemic. Press conferences increasingly provided new and pressing information about threats posed by restrictions on daily life, such as the threat of travel restrictions, increased border controls, mandatory health certificates or even the obligation to wear respiratory masks – issues that would affect a larger share of the population. By mid‐March 2020, as the initial demand for information about health risks was satiated, press conference discussions of these subject areas declined and threats to education and the political and bureaucratic systems came to the forefront as the central threat by mid‐March, making up about 20 per cent of all threat language during this phase. This overarching threat appeal shifted significantly from June 2020 onwards. Government communication on the COVID‐19 pandemic up to that point had been largely balanced between the above‐mentioned two distinct threat categories. While the subject area health risks as well as supply chain and security remained present and only slowly diminished as the pandemic progressed, press conferences now increasingly discussed threats to the economy and the political and bureaucratic systems, both remaining a central concern for the remainder of the initial phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Taken together, this shows that the understanding of the threat introduced by the pandemic changed over the course of the period under investigation. While governments initially saw the dominant threats posed by COVID‐19 as individual and collective health risks and the restriction of daily life, the threats soon expanded to encompass a broad range of issues. Based on this evidence, we can confirm Hypothesis 2b.

Conclusion

The use of threat language in political crisis communication is a double‐edged sword. It helps political actors to alert the public to dangers and galvanize support for measures. If overused, however, it conveys an image of anxiety and overload, which eventually undermines trust in leadership and measures during crises. Thus, speakers employ it with care as this paper demonstrates. Our results show that the role of the speakers, that is, whether they appear as politicians or not, does not affect the likelihood with which threat language is used. Women, however, tend to be less likely to use threat language than men and we thus confirm previous studies that lead us to expect gendered patterns of crisis communication. These findings imply that the gender of politicians matters and that a diverse set of speakers can also lead to more diverse crisis communication. Still, since the effect size is relatively small, we conclude that, on the whole, individual‐level factors are not as important drivers of different strategies of crisis communication as previous research suggests.

Our findings further demonstrate that context matters. We provide evidence that there is a large variation in the use of threat language between the subject areas that speakers are addressing. In particular, the health system and public management are subject areas that are most prone to entail threat language. In view of how the pandemic unfolded across the world, these findings are not surprising. Finally, our results also indicate that the use of threat language diversified in the course of the pandemic. The longer the pandemic lasted, the more the threat language of governments reflected the pandemic's nature as a multi‐threat (Boin et al., Reference Boin, McConnell and 't Hart2021). In turn, when considering other crisis than the pandemic, it seems likely that threat language is mostly used in the sectors most affected by a crisis at the beginning, while it then diversifies to other areas.

Overall, while we focus on the COVID‐19 pandemic, we believe that our findings are applicable to other crisis situations beyond health crises. In particular, the phases of the pandemic followed similar patterns as those of other crises (Boin et al., Reference Boin, McConnell and 't Hart2021) and even across our large sample, country factors did not significantly shape crisis communication. Thus communication strategies during COVID‐19 should be comparable to other crisis situation in different countries. In addition, the pandemic with its multi‐dimensional nature affected a very diverse set of countries at a similar point in time and hit a diverse set of sectors, hence, the way political actors communicated during COVID‐19 should provide robust evidence for how political actors use communication tools when dealing with the challenges confronted by crises way beyond the health sector.

Building on the results of our paper, future research on the use of threat language could address a number of interesting questions. First of all, future studies could investigate the extent to which actors combine the negative emotions of threat language with the positive emotions, as also the exemplary quote from the statement by New Zealand's former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern suggested. In this context, previous literature found that such a combination, or ‘emotional battery’ (Jasper, Reference Jasper2011, Reference Jasper, Maney, Klutz‐Flamenbaum, Rohlinger and Goodwin2012), is an effective tool of mobilization. Second, future research should enquire into whether different leadership styles and cultural factors affect the frequency of threat language. As studies on the use of emotions in advertising suggest (e.g. Cochrane & Quester, Reference Cochrane and Quester2005), the effect of emotions on audiences is influenced by the cultural context. Third, another interesting avenue for future research pertains to the setup of press conferences or who gets to speak in political crisis communication. Our findings show that 42.9 per cent of speakers are politicians and 20 per cent are health experts. The rest comprises a diverse group of actors ranging from public servants to business representatives and citizens. Future research should identify factors that influence the choice of speakers in governmental crisis communication in order to understand when politicians take centre stage and when they (strategically) give others the opportunity to speak. Finally and moving beyond the COVID‐19 pandemic, future research could also investigate in more detail whether different kinds of crises affect the frequency of threat language in governmental crisis communication.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), Grant‐DOI 10.55776/P34225. For open access purposes, the authors have applied a CC BY public copyright license to any author accepted manuscript version arising from this submission. We would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2023 Annual International Communication Association Conference in Toronto and the 2022 General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research in Innsbruck.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: