Introduction

Do political parties take differing public stances on education? Historically, the answer was a clear yes. Through the nineteenth and early‐twentieth centuries deep partisan divisions emerged over the role of the church in education, social stratification among pupils and the teaching of morals (Ansell & Lindvall, Reference Ansell and Lindvall2021; Morgan, Reference Morgan2002; Paglayan, Reference Paglayan2021). As the state‐building era ended, however, the nature of partisan conflict over education changed. While voters’ education is an increasingly central political cleavage (Attewell, Reference Attewell2021; Simon, Reference Simon2022; Stubager, Reference Stubager2009), existing work debates the extent to which education policy remains a domain of partisan conflict.

On the one hand, sociologists studying the dissemination of global norms argue that the post‐war emergence of professionalised public administrations, interacting with international organisations, reduced the scope of domestic conflict over education (Furuta, Reference Furuta2020; Lerch et al., Reference Lerch, Bromley, Ramirez and Meyer2017; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Kamens and Benavot1992). These shifts produced a convergence in both party action and rhetoric, by creating common incentives for parties to showcase their commitment to global education reforms (Jakobi, Reference Jakobi2011). By contrast, work looking at electoral and interest group coalitions finds ongoing partisan differences in educational speech and reform, which in turn reflect the distinctive interests of partisan bases (Ansell, Reference Ansell2010; Busemeyer, Reference Busemeyer2014; Castles, Reference Castles1989; Österman, Reference Österman2017).

To date, adjudicating among these approaches has been difficult. Empirically, existing cross‐national studies of educational speech are largely limited to examining its overall salience (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Franzmann and Garritzmann2013; Jakobi, Reference Jakobi2011). While yielding important insights about when and where parties speak about education, this work leaves open critical questions regarding what parties are actually talking about. At a theoretical level, questions also remain as to when parties have incentives to take differing public stances on education. Recent work has increased our knowledge of the conditions under which politicians attach more salience to varying domains (Pinggera, Reference Pinggera2021; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2014), express more specific policy proposals (Bräuninger & Giger, Reference Bräuninger and Giger2016) and adopt different tones (Bischof & Senninger, Reference Bischof and Senninger2018). However, understanding how policymakers speak about specific issues requires theorising both their underlying goals and their incentives to express these stances publicly.

Our analysis provides the first systematic examination of how mainstream right‐ and left‐wing parties have rhetorically approached education in the post‐war period. We construct a new dataset, the Education Politics Dataset (EPD), which draws on an original hand coding of the manifestos of the largest right and left parties in 20 wealthy long‐standing democracies from the 1950s to 2020 (1970s onwards for Greece, Spain and Portugal). This approach yields 786 coded manifestos, categorising political rhetoric on education across 34 policy indicators. The EPD follows recent studies on migration (Dancygier & Margalit, Reference Dancygier and Margalit2020), housing (Kohl, Reference Kohl2020), welfare (Giuliani, Reference Giuliani2022) and foreign policy (Dietrich et al., Reference Dietrich, Milner and Slapin2020) in focusing on party manifestos as a critical indicator of partisan attention.

Political speech does not translate directly into policy: once in power, parties may enter governing coalitions (Jungblut, Reference Jungblut2017) or face competing priorities (Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005). However, existing research finds that election promises are an important determinant of public (Klingemann et al., Reference Klingemann, Hoffebert and Budge1994; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson2017) and education policy (Ansell, Reference Ansell2010) and can influence public perceptions (Schneider & Jacoby, Reference Schneider and Jacoby2005). Crucially, manifestos are authoritative statements of a party's official positions, as elaborated through its internal decision‐making processes. They condense the stances that parties wish to communicate to voters, who can, in turn, use them to hold parties to account (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2003; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2014).

We show that there is important variation in the extent and character of partisan attention to education: some issues are more consensual and convergent, while others remain divisive and divergent. To theorise this variation, we build on Busemeyer et al.’s (Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann and Neimanns2020) work on the domestic politics of education. We argue that mainstream parties’ speech incentives follow from the intersection of a given issue with a) existing partisan cleavages and b) diffuse electoral support.

Where an issue cuts across existing political cleavages and offers broader electoral gains, parties benefit from devoting attention to the issue and taking common stances, a pattern we describe as de‐polarised. However, many issues offer concentrated gains/losses to a party's base. Where an issue aligns with existing partisan cleavages, but also has a more universal electoral appeal, we expect a pattern of differential salience: the party whose base benefits from the issue will emphasise it more, while its rival avoids discussing it. By contrast, where an issue divides the electorate, parties have an incentive to take contrasting stances, leading to polarisation. We further draw on Garritzmann's (Reference Garritzmann2016) work on time‐sensitive partisanship to theorise how past educational choices shape speech incentives.

The paper investigates these claims by examining three areas: the distribution of education (funding, access, and de‐streaming); the plurality of educational governance (participation, markets and decentralisation); and the structure of educational content (quality, academic focus and traditionalism). We show that in the first post‐war period, most political debate focused on educational distribution and, to a lesser extent, governance. Given the need to address gaps in access to secondary education, discussion of expansion initially was de‐polarised – all parties supported it. However, as education systems grew, and expansion placed more concentrated costs on the right's higher‐income base, mentions of funding and access took on a more differentially salient character. Given these issues’ widespread electoral appeal, right parties chose to speak about them less, rather than speak negatively about them. By contrast, issues of de‐streaming and market governance show more open polarisation.

In the post‐1980s period, as parties’ focus partly shifted from quantity to quality, new issues emerged. This development led to a rise of de‐polarised attention towards policies aimed at improving educational quality and participatory governance, but also new partisan polarisation around the transmission of traditional values.

These findings offer a window into political speech more generally, and are increasingly relevant at a time when education is emerging as a new source of social conflict, as evidenced by debates over religion, critical race theory and LGBTQ+ rights from the United States to France to Italy. Rather than suggesting a uniform politicisation or depoliticisation of educational speech, the paper shows that issues interact with the electoral and institutional structure in systematic ways to promote varying patterns of politicisation.

Conceptualising education in political speech

What explains variation in the positions parties publicly take on education? The existing literature provides different answers to this question, which, in turn, build on different conceptualisations of both the purpose of political speech and the nature of partisan divisions.

One line of work sees educational speech largely as an expression of norms of modernity. For instance, in their analysis of global shifts in education reform, Bromley et al. (Reference Bromley, Furuta, Kijma, Overbey, Choi and Santos2023) conceptualise reforms as discursive acts that ‘indicate the intensity of belief in education as a core institution in society’ (p. 150). In this framing, both action and speech serve a common expressive purpose that is global and shared rather than local and divisive.

These shared global norms emerged from the growing influence of experts and international organisations. In the early post‐war period, these actors emphasised two key issues: expanding access to education (Jakobi, Reference Jakobi2011; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Kamens and Benavot1992) and re‐shaping the curriculum to emphasise individual rights (Lerch et al., Reference Lerch, Bromley, Ramirez and Meyer2017). In the 1980s, these same actors took a more market‐liberal turn, overlaying questions of access and individual rights with the rhetoric of performance and quality (Mehta, Reference Mehta2013; Verger et al., Reference Verger, Fontdevila and Zancajo2016). Domestic policymakers, in turn, shifted attention from educational access and content to governance, leading to convergent approaches across parties and countries.

A second line of work on education reform flips this logic, emphasising its local and conflictual nature. Most of these studies focus on policy change – not speech – showing that institutional variation in education systems follows from distinctive partisan approaches to education combined with domestic political constellations (Busemeyer, Reference Busemeyer2014; Castles, Reference Castles1989; Jungblut, Reference Jungblut2015; Österman, Reference Österman2017). Where this work turns to speech, it largely treats it as an expression of educational interests (Ansell, Reference Ansell2010; Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Franzmann and Garritzmann2013). Here, the presence or absence of attention to education reflects parties’ support for educational expansion, which varies across party families within their particular institutional and historical contexts (Ansell, Reference Ansell2010; Garritzmann, Reference Garritzmann2016; Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2011; Jungblut, Reference Jungblut2017).

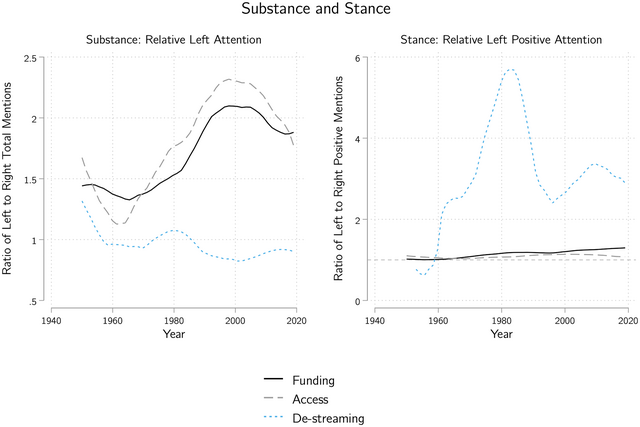

When we look at the empirical record, we see evidence for both perspectives: some educational issues look divisive and divergent, while others follow a more consensual and convergent path. In the next section, we introduce our conceptualisation and coding schema in more depth, but Figure 1 provides an initial snapshot. It builds on Dancygier and Margalit's (Reference Dancygier and Margalit2020) distinction between substance (what policy issues do parties address?) and stance (what positions do they take?) to examine partisan differences over time on three distributive issues: funding, access and de‐streaming. The first panel of Figure 1 shows the ratio of attention given to these three issues by left and right parties in each election. If, across all countries, left and right paid equal attention to an issue, then the average gap would converge to one. We see that this is largely the case for de‐streaming, but not for funding and access, which are disproportionately emphasised by the left.

Figure 1. Variation in substance and stance over time.

The right‐hand side of Figure 1 follows the same logic but looks at stances. It shows the average share of speech that is positive towards a policy area, comparing the ratio between left and right. Again, we see variation. Here, funding and access are closer to parity in terms of positive attention, while de‐streaming is divisive. The left is up to four times more likely to speak positively about it. In short, we see neither uniform convergence nor uniform politicisation.

To explain these patterns, we turn to theories of political speech. We build on the assumption that mainstream parties, in contrast to niche parties, see policy not only as an end in itself but also as a means to achieve office (Strøm & Müller, Reference Strøm and Müller1999). They therefore craft their public speech to communicate to both their specific constituencies and the general electorate (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Budge, Reference Budge2001; Dassonneville, Reference Dassonneville2018; Pinggera, Reference Pinggera2021; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2014). Educational issues differ in their appeal to partisan bases and to the wider electorate (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann and Neimanns2020) – both of which evolve as a result of shifting cleavages (Ford & Jennings, Reference Ford and Jennings2020) and feedback effects that shape and constrain future choices (Garritzmann, Reference Garritzmann2016; Pierson, Reference Pierson1993). The nature of education issues, combined with distinct partisan bases, thus creates different incentives.

First, parties have electoral and interest group bases with different stakes in education. In the post‐war period, left parties drew on a more working‐class electoral base (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2007; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1994) and tended to have stronger links to groups, such as primary school teachers, vested in secular state provision (Ansell & Lindvall, Reference Ansell and Lindvall2021; Wiborg, Reference Wiborg2009). By contrast, right parties largely had wealthier bases and more links to religious and elite education providers (Gidron & Ziblatt, Reference Gidron and Ziblatt2019; Giudici et al., Reference Giudici, Gingrich, Chevalier and Haslberger2023; Layton‐Henry, Reference Layton‐Henry1980). Over time, as these traditional class and religious cleavages faded, new divides have emerged around social values (Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2022; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1990). We argue that some educational issues align with these changing partisan cleavages, providing specific benefits (costs) to a party's core base, whereas other issues cut across them. All else equal, we expect parties will devote more attention to, and adopt more positive stances on, educational issues that benefit their base – and vice‐versa.

Second, however, speech also plays a critical role in signalling a party's priorities to the broader electorate. Busemeyer et al. (Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann and Neimanns2020) hypothesise that parties generally adhere to broad electoral demands where voters provide ‘loud and clear’ signals, meaning that the public has a strong and coherent preference on an issue. We draw on this claim to argue that certain issues are more likely to provoke ‘loud and clear’ public responses. When an educational issue has a general appeal, meaning a universal reach and less of a zero‐sum structure that divides the electorate, parties have fewer incentives to adopt contrasting positions than when an issue has a targeted or zero‐sum structure.

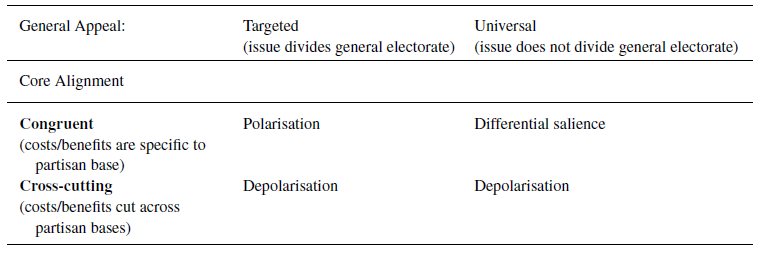

Table 1 outlines our predicted mode of partisan conflict, based on the core alignment and general appeal of an issue. We distinguish three configurations of cross‐partisan competition. When an issue divides both party bases and the electorate, we expect polarisation – similar levels of partisan attention but different stances. When an issue provides clear benefits (or costs) for parties’ base, but is less electorally divisive, we expect more variation between parties in attention than in stance. This constellation results in differential salience: parties that are less positive towards the issue talk less about it, rather than taking a negative stance. When an issue cuts across existing political cleavages, parties are likely to take distinct positions both in attention and stances, leading to a more depolarised configuration.

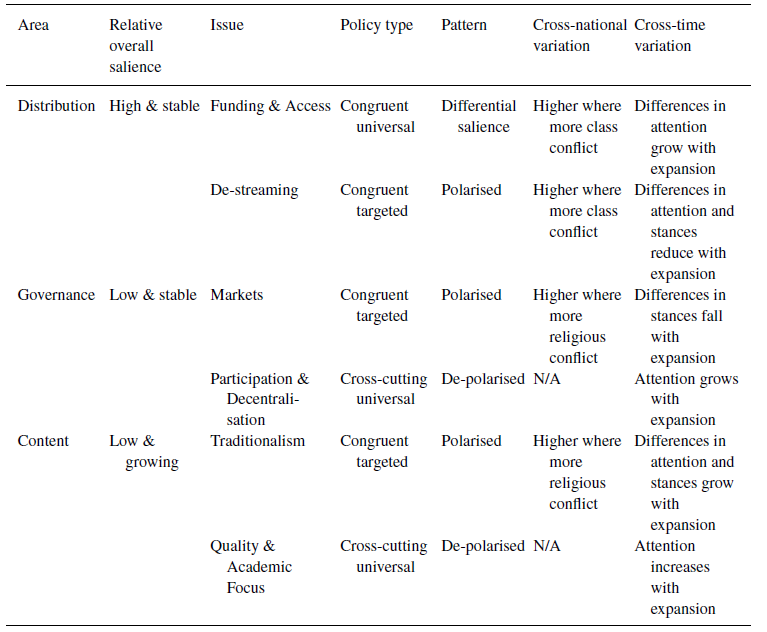

Table 1. Predicted patterns of educational politicisation.

These claims raise an obvious question: what shapes an issue's alignment and broader appeal? Answering this question requires conceptualising educational issues in a particular context. We point to two components of the context: the nature of the electoral base and the structure of the education system. In line with the above theory, as partisan bases change, so do parties’ incentives to politicise particular issues. Therefore, understanding the connection between the partisan base and a given issue is critical. However, issues do not exist in a vacuum. As Julian Garritzmann (Reference Garritzmann2016) argues, they are ‘time sensitive’ – past choices over institutional structures shape future politics, both because mass public preferences are partly endogenous to existing structures, and because interest groups and other actors mobilise around them. Understanding the politics of specific incentives, then, requires thinking about speech as a product of a party's base and institutions at a particular moment in time.

Following recent studies on education politics (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Jens and Jupskås2023; Jungblut, Reference Jungblut2015), we apply this reasoning to three issues that have dominated historical debates on education policy: who should receive it (distribution), who should provide it (governance), and what should be taught (content)? The following sections develop specific expectations for each area and the more concrete issues they encompass.

Distributive issues

Historically, access to education was the privilege of a small elite. Expanding access and funding were central issues in the development of mass education systems, and raised the further question of whether to equalise expansion by de‐streaming education, that is, relaxing grading, curricular differentiation and separate qualification paths. A long tradition of empirical (e.g., Ansell, Reference Ansell2010; Busemeyer, Reference Busemeyer2014) and theoretical (Domina et al., Reference Domina, Penner and Penner2017) work understands the three dimensions as having key distributive implications for class actors.

Left parties traditionally represented the classes with the least access to prestigious academic certificates; those who stood to benefit the most from publicly funded expansion and de‐streaming (Ansell, Reference Ansell2010; Iversen & Stephens, Reference Iversen and Stephens2008). Thus, on aggregate, we expect left parties to have more incentives to positively emphasise distributive issues than the right. Indeed, even as the left's grounding in the working‐class vote has declined, its new base of middle‐class voters and public‐service professionals continues to support greater access and funding (Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2022).

By contrast, the right's incentives to publicise its distributive stances vary systematically across issues and over time. Historically, right‐wing electoral coalitions relied on older and wealthier voters who already had access to prestigious educational paths and were more sensitive to the costs of increased public funding (Ansell, Reference Ansell2010). Dependent on these elite coalitions, pre‐war conservative parties often opposed increasing educational access and funding (Ansell & Lindvall, Reference Ansell and Lindvall2021). But as education – and later social investments – was recast from the 1950s as a meritocratic and growth‐friendly alternative to welfare policies, such outright opposition became unpopular (Garritzmann and Häusermann, Reference Garritzmann, Häusermann and Palier2022; Jensen, Reference Jensen2011). Further pressure for expansion came from the right's base, with middle‐class parents demanding more opportunities and employers more skills (Busemeyer, Reference Busemeyer2014; Giudici et al., Reference Giudici, Gingrich, Chevalier and Haslberger2023).

This dynamic changed from the 1970s onwards. As expansion began to target former elite tertiary pathways, it threatened the comparative educational and labour market advantages of the right's base (Ansell, Reference Ansell2010; Garritzmann, Reference Garritzmann2016; Jungblut, Reference Jungblut2015). However, by creating new beneficiaries of further expansion, these same forces also limited outright opposition (Garritzmann, Reference Garritzmann2016; Jungblut, Reference Jungblut2015; Pierson, Reference Pierson1993). Put differently, although the right's base had an interest in opposing further expansion, feedback effects from past policies expanding educational benefits reduced the incentives for right parties to openly oppose expansion.

Concretely, the different costs and benefits for left and right partisan bases, and overtime, feedback effects related to expansion, lead us first to expect a pattern of differential salience in attention to funding and access: that is, larger gaps in substance (attention) than in distinct stances. Second, building on these claims, we expect that where parties are less divided along class lines, differences in substance and stance may attenuate. Third, as systems expand in enrolment, feedback effects reduce incentives for overt opposition, increasing the incentives for differential salience, as further shifts impose higher costs on the right's core base.

By contrast, de‐streaming creates much more specific targeted winners and losers. Streaming, like privatisation, can provide a mean of maintaining privileged pathways in situations of expanding access (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2011; Jungblut, Reference Jungblut2017). The move towards more comprehensive schools thus takes on a more zero‐sum character – de‐streaming schools often leads to the end (often the closure) of privileged elite programmes. We expect de‐streaming to be more openly polarised, with the right taking a more negative stance. Again, however, the politics are likely to change over time. As de‐streamed/streamed structures take shape, and enrolment expands, the benefits to politicians of continuing to politicise them diminish as more voters become vested in the status quo.

Governance

Nineteenth‐century state building generated tensions between state authorities and those who had traditionally controlled the provision of education, namely local authorities, private (religious) providers and stakeholders such as parents and teachers (Ansell & Lindvall, Reference Ansell and Lindvall2021; Lipset & Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Morgan, Reference Morgan2002). Subsequent conflict in educational governance thus centred on who controls education: whether to allow private actors (markets), the balance between central and local control (decentralisation) and the extent to which stakeholders can shape provision (participation).

In many early post‐war education systems, debates about markets and private actors in education were effectively debates about the role of religious education providers (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2024). They largely aligned with historic left‐right cleavages. In this period, parties on the right drew on more religious, rural and elite voters with stronger links to religious schooling (Knutsen, Reference Knutsen2004) and had more ties to church providers (Giudici et al., Reference Giudici, Gingrich, Chevalier and Haslberger2023). By contrast, while many social democratic parties had confessional voters in their base, they were ideologically linked to secular movements and tended to emphasise material class appeals over religious ones (Ansell & Lindvall, Reference Ansell and Lindvall2021). The constellation of class and religious cleavages thus means that, in the early post‐war period, questions about markets often aligned with the core axes of political conflict. Markets, like streamed schools, tend to offer distinct benefits to specific constituencies, making them more divisive. We therefore expect substantial open polarisation over markets in this period.

Over time, however, the issue of funding for private schools became linked to a new market‐liberal agenda in education, which emphasised choice and competition as benefits for parents and pupils rather than religious providers (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2011; Verger et al., Reference Verger, Fontdevila and Zancajo2016). Questions of school choice often drew together new middle classes with minority voters seeking diverse options. This shift, combined with the blurring of class electoral constituencies and the rise of new middle‐class voters on the left who could potentially benefit from choice, softened the left's opposition to markets (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2011). Because these new debates about markets were less focused on religion, the institutional space around them was more open than it was for distribution. We thus expect fewer institutional feedback effects from system expansion.

Parents can influence education not only through choice but also through participation. Stakeholder participation has grown in prominence in the post‐war period, with the 1968 student protests focusing political attention to parent, pupil and teacher participation. Unlike market‐based choice, participation does not clearly align with existing left‐right cleavages. While younger voters and students tend to lean left, participatory issues also draw on the demands of wealthier parents, a core constituency of the right (Brown, Reference Brown1990; Nickerson, Reference Nickerson2012).

The same is true of decentralisation. The growth of the public sector put issues of decentralisation on the agenda in the 1970s and 1980s, but partisan alignments to regional governments differ across countries. In the UK, for instance, the right‐wing Thatcher government centralised power to limit the power of local governments, while in the Nordic countries the right promoted decentralisation as a means of limiting the growth of central bureaucracy (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2011).

As such, decentralisation and participation are less clearly aligned with left‐right divides than market reforms or de‐streaming. In any given country, their politics may be highly structured along left‐right lines, but we expect them to be generally less salient and polarised than other dimensions in our cross‐national study. We therefore predict polarisation on markets, with right parties expressing more positive stances, and less conflict on the other governance issues. We further expect these conflicts to be greater where religious divisions between parties are stronger, and for the differences to diminish over time as the issue of markets becomes linked to secular, broader middle‐class appeals.

Content

Historically, elite schools emphasised academic content that prepared wealthier students for university examinations, while vocational schools taught work‐related skills and mass schools aimed to instil morals in the general population (Young, Reference Young1971). The establishment of modern education systems integrated these institutions, raising questions about what kind of knowledge such systems should prioritise (academic focus), how this knowledge should be delivered (quality) and its normative character (traditionalism) (Gutmann, Reference Gutmann1999; Kliebard, Reference Kliebard1986). As Berg et al. (Reference Berg, Jens and Jupskås2023) argue, little comparative work exists on partisan approaches to educational content. We therefore draw on insights from studies on curriculum‐making and standards to develop expectations about different patterns of politicisation for the three content‐related issues.

Issues of quality and academic focus largely cut across parties’ core constituencies. Improving quality is considered a universal valence issue; Mehta (Reference Mehta2013) argues that standards are the educational ‘paradigm’ of the second post‐war period. Experts and international organisations have been particularly influential in pushing the need to raise standards through instruments ranging from research‐based teacher‐training to new inspection regimes (Lerch et al., Reference Lerch, Bromley, Ramirez and Meyer2017). Views on the specific goals and design of quality reforms may vary, especially when they have distributive implications for constituencies such as teachers. But quality appeals rarely divide voters.

The focus on academic over practical and vocational knowledge also cuts across party lines. Left‐wing constituencies have long been divided between those who see academic curricula – traditionally reserved for the wealthy – as a means of empowerment or as a tool to devalue practical knowledge and, by extension, work (Martin, Reference Martin2023). Within the traditional right‐wing base, businesses tend to be interested in vocationally‐oriented curricula (Busemeyer, Reference Busemeyer2014). In contrast, as individuals value programmes that they themselves have experienced (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann and Neimanns2020), wealthier voters tend to support academic curricula with high cultural prestige (Young, Reference Young1971). Each type of knowledge is associated with vested interests, which in turn have different links to parties (Kliebard, Reference Kliebard1986). Given this cross‐cutting structure, we expect the discussion on academics and quality to follow a depolarised pattern.

We expect to see more conflict over the normative character of curricula. Discussions on whether curricula should convey conservative or liberal understandings of gender, culture and authority are directly related to conflicts over traditional religious and more contemporary postmaterialist values. These values underlie the cultural cleavage that has increasingly defined party constituencies since the 1970s (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1990). We therefore expect the rhetoric around traditional content to show an increasingly polarised pattern, and the overall salience of content‐related issues to increase over time. We do not have strong expectations as to how institutional feedback effects from system expansion affect these outcomes.

Summarising our expectations

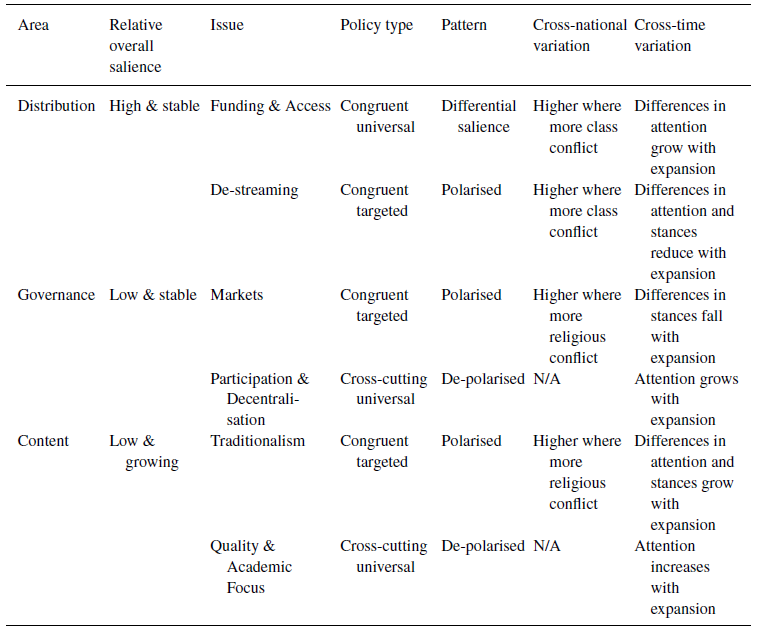

The above discussion sets out a framework for thinking about the politicisation of educational issues. It argues that parties’ rhetorical incentives vary across issues, depending on the intersection of the specific benefits of emphasising an issue for their base and the wider electorate. These specific benefits and costs are in turn a product of the cleavage environment and the structure of existing policy. Table 2 outlines these claims.

Table 2. Summary of expectations

In general, parties have more distinct stances where issues align with political cleavage structures. Where issues align less – either because they create cross‐cutting benefits or because the cleavage structure is blurred – we expect less distinct stances. However, the particular costs of articulating these stances are partly a function of the existing institutional structure. Where institutions have gained widespread support, parties that oppose them are more likely to mention them less, perhaps turning to politicise new issues that are less popular.

Concretely, we hypothesise that issues of participation, decentralisation, quality and academic focus, while controversial in some contexts, are not generally aligned with party competition and thus should produce more depolarised speech with similar attention and stances. By contrast, markets, de‐streaming and traditionalism fit different partisan cleavages but lack universal appeal. Here we expect polarisation, albeit the incentives for it change over time. Issues of funding and access become more vested as education systems expand, reducing right parties’ incentives to openly challenge them, leading us to expect differential salience.

Research design

To test these expectations, we develop an original database of coded manifestos that allows us to examine whether party families approach education issues in different ways in their speech. We first explain our rationale for this effort and then turn to the design of our speech measurement and analysis.

Existing data

The main existing data‐source for analysing partisan speech is the Comparative Manifesto Project (MARPOR) (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020). The MARPOR dataset has two major limitations for testing the above hypotheses.

First, MARPOR relies on saliency theory (Budge, Reference Budge2001). The coding approach thus assumes that parties compete on issue emphasis and is not designed to analyse competition on stances (Gemenis, Reference Gemenis2013). While the two education‐related codes in the MARPOR codebook – 506 Educational Expansion and 507 Education Limitation – do denote contrasting stances, they are too broad to capture stances on substantive issues. More disaggregated data is needed to examine whether stances and attention vary across areas and policies, as hypothesised above. Second, because MARPOR is designed to characterise partisan speech across policy fields and allows coders to use only one code per statement (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020), it undercounts education‐related text.

To assess the above hypotheses, we therefore need novel data measuring how parties approach different issues related to formal education. Following the Council of Europe (2024), we define the latter as ‘the structured education system’, ranging from institutionalised pre‐school, compulsory and vocational education to higher and further education and excluding informal and non‐formal learning.

Our approach to measuring speech

To accurately describe the substance and stances of post‐war education politics, we have created a new dataset. The Education Politics Dataset (EPD) codes the text relating to formal education in the manifestos of 20 wealthy, long‐standing democracies with populations of more than 5 million: Australia, Austria, Belgium/Flanders, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US. Following Dancygier and Margalit (Reference Dancygier and Margalit2020), we include, for each election, the main competing left‐ and right‐wing parties (Supporting Information Appendix A).

Our data collection covers all national manifestos of the two main parties issued in each election from 1945 to 2020. We code national manifestos, except for Belgium, where parties split into independent organisations after 1968. Here we code the Flemish parties as they represent the larger community in terms of population. Although attention at the national level may differ in federal systems, we assume that national organisations reflect similar principles to subnational branches with direct policy responsibility. We discuss the validation and robustness of these assumptions below.

Manifestos have a similar structure across time and place, making them a suitable document for standardised coding procedures (Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2014). However, schools are labelled differently across countries, and political speech often relies on cultural signals that are difficult to capture with contemporary automated protocols. We therefore relied on human coders with linguistic and country‐specific knowledge, resulting in a highly time intensive coding process. We estimate that each party required at least 45–55 hours of coding‐work, with additional time needed to prepare manifestos and review the coding. This approach gives us greater accuracy and depth in analysing speech, but means that we were limited in the number of parties we could cover. Our data thus provides a means of exploring how the major parties, which played a fundamental role in post‐war government formation, rhetorically shaped education politics.

We applied a four‐step coding procedure. First, we gathered all manifestos in digital format. These are largely the same manifestos as those included in MARPOR. However, to increase comparability in a few cases, such as the early Danish and Swedish manifestos, we collected new original sources (Supporting Information Appendix A.2). Second, we identified education‐related text. We define education‐related text as either manifesto sections dedicated to education or units of at least two sentences devoted to formal education. Non‐English text was automatically translated into English and the translations checked by expert speakers. All coding was done in the original language by native or fluent speakers.

Third, we developed a coding schema (online Appendix B). We replicated the MARPOR approach (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020) and parsed the text into quasi‐sentences. A quasi‐sentence includes one statement (i.e., a stance for/against a policy). It can therefore be an entire sentence or part of a sentence. We developed the coding schema ex‐ante, based on the existing literature, and then refined it after a pilot coding (Appendix C). We classified statements into three types: level of education, aim and policy. Each statement could receive a maximum of one code of each type. Aim codes are assigned to statements that link education to general values, objectives or problems, whereas policy codes are applied to sentences that either assess past performance or contain an actionable statement.

This paper focuses on policy codes that contain an actionable statement. We measure thirty‐two policies, dividing each into a positive and negative valence. For instance, the statement ‘Alianza Popular accepts private initiative in the operation of universities’ (Alianza Popular, 1982) is coded as a positive statement on the policy of private education, while ‘we will seek to strengthen and prioritise state schools’ (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, 2015) is coded as a negative statement on the policy of private education (one of the components of our ‘market’ index). Our coding breaks down both the substance of educational rhetoric (attention to issues measured by total mentions) and the stances parties take on a given issue.

Finally, coders applied this schema to the collected manifestos following a standardised procedure to maximise reliability. Due to the language specificity and long‐term nature of the coding, we could not rely on inter‐coder reliability tests to maximise quality. Instead, we trained our 17 coders extensively, double‐coded part of the coding blindly, and double‐checked all coding. We also systematically discussed ambiguous coding decisions between the core team and coders to reach a consensus and to ensure that codes were applied reliably and consistently across countries.

To further verify our approach, we compare our total number of coded educational sentences with the education content in MARPOR (Appendix D). We use the same approach as MARPOR to measure educational salience, dividing the total number of coded education quasi‐sentences by the total number of quasi‐sentences in the manifesto. Where possible, we take the latter from MARPOR itself, while in other cases we must generate the total count from the original manifestos. Reassuringly, the two measures are highly correlated, with an overall correlation of .64 between the share of education content in MARPOR and the EPD. Given we use national manifestos, including in federal countries, we perform an additional validation comparing the Bavarian and federal manifestos in Germany, which shows strong similarities in the basic structure of speech (Appendix E).

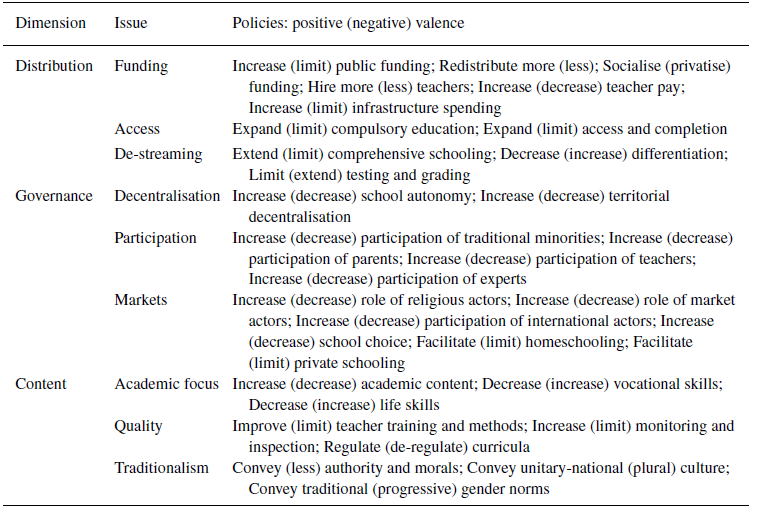

To match our theoretical attention to distribution (funding, access and de‐streaming), governance (markets, participation and decentralisation) and content (traditionalism, academics and quality), we allocate our 32 policy‐codes to these nine policy areas, each scaled to express support for the underlying dimension: equal and extensive distribution, pluralistic governance, and a high‐quality traditional curriculum. For each area, we measure two outcomes: substance – or attention – total mentions (the sum of positive and negative statements) on a given issue as a share of all education content; and stances, the share of these total statements that are positive. Table 3 illustrates the conceptual structure, while Supporting Information Appendix B provides detailed descriptions and examples for each code.

Table 3. Conceptual structure and policy allocation

Approach to analysing variation in speech

To test our hypotheses that parties approach issues in varying ways, we proceed in two steps, analysing both substantive attention to policies and stances. First, we regress a) substance (share of education mentions) and b) stance (share of mentions that are positive) on partisanship, interacted in decade dummies. Because attention to education is likely to vary based on the structure of the business cycle and the salience of immediate economic issues, we control in each regression for the employment rate and GDP per capita (Feenstra et al., Reference Feenstra, Inklaar and Timmer2015). Parties in office often speak differently about education because they need to defend their record, so we control for left prime minister incumbency. In each regression, we employ country fixed effects, decade dummies, and election‐specific clustered errors. We thus compare left and right parties over time, net of national differences, to see whether parties speak about education differently in a given decade.

If an issue is depolarised, we expect no significant differences in the share of overall substance (share of mentions) or stances (share of positive mentions) between parties. If an issue is differentially salient, we expect larger partisan gaps in substance than in stances. Finally, polarised issues will display larger gaps in stances than in substance. This first specification allows us to examine patterns over time. To address our second‐order prediction – that these patterns will vary across party bases and institutional development – we conduct two additional analyses.

First, we link parties to their electoral bases using the World Political Cleavages and Inequality Database (WPCID)(Gethin et al., Reference Gethin, Martínez‐Toledano and Piketty2021). The WPCID is a dataset of election and public opinion studies that harmonises a range of individual‐level demographic, income, and educational variables, as well as voters’ party choices, over time. For most countries, information on voter demographics is available from the 1970s to the present, a narrower period than our EPD data. We match all parties in our dataset to the demographic characteristics of their voters, averaged over the decade of the election (Appendix F).

Because of the centrality of both religious/cultural and distributive interests to education politics, as outlined in our theoretical section, we focus on these demographic characteristics in the party electorate. High‐quality measures of class are not available over time, so we use a cohort‐standardised measure of education that looks at the relative base of the party across 10‐year age cohorts. This measure correlates at 0.51 with self‐reported middle‐class status, and .88 with a measure of middle‐class status that is relative to the national mean (Appendix F). We also measure the share of the base who report not attending church (i.e. the secular share), measuring this share relative to the national mean.

We first regress both substance and stances on the interaction between the cohort‐standardised education measure/relative secular share of the base and party type. We include country and decade fixed effects in each model. These models tell us whether there are left‐right differences net of general national and time trends. In models that consider religious bases, we control for the education of the base and vice‐versa. We can thus see whether left and right parties with a more secular (less formally educated) base take more distinct stances on distributive, governance, and content issues than parties with a less distinct base.

As a second step, we examine whether party speech changes as institutions expand, potentially exerting feedback effects that make certain forms of speech more or less costly. To do this, we relate speech in a given election to enrolment rates averaged over the decade, using the Barro‐Lee (Reference Barro and Lee2013) data on secondary school enrolment (Appendix G). We rely on data that measures the share of the youth cohort enrolled in secondary, rather than tertiary, education for two reasons. Theoretically, the expansion of secondary education is one of the central educational shifts in the post‐1945 democracies; enrolment rates range from below 40% in the early post‐war period to nearly 100% in most contexts today. This growth makes these systems a likely source of institutional feedback effects. Second, secondary enrolment is empirically more comparable. The lack of an agreed definition of a tertiary cohort means that comparative measures are less clearly consistent in defining cohort enrolment (Barro & Lee, Reference Barro and Lee2013).

This approach is a thinner test of policy feedback effects than Garritzmann (Reference Garritzmann2016) theorises. However, given the heterogeneity of educational institutions and their differential feedback effects, enrolment in the core compulsory system serves as a proxy for institutional entrenchment. Appendix H shows the structure of these data, with Appendix I showing the full analyses that accompany the ensuing figures.

We further engage in a series of robustness tests. We replicate the core analyses examining each area as a share of total manifesto speech, not just educational speech (Appendix J). We further perform a jackknife analysis and restrict the analysis to unitary states to assess whether the sample composition is driving results (Appendix K). Appendix L replicates the analysis relating attention and stances to parties’ educational base (included in Figure 4, Appendix Figures L1 and L2) with the relative class measure.

As most manifesto rhetoric is not level specific, we cannot reliably analyse differences in the education levels to which the statements refer. Therefore, in this paper we pool across all levels. However, as a robustness check, we rerun our analyses excluding explicit mentions of non‐compulsory education (Appendix M) and look at the conditioning effect of tertiary expansion on both total educational speech and speech specific to non‐compulsory education (Appendix N). Appendix O further investigates the temporal structure of our data, replicating our core analyses using a measure of the decade lagged average salience/stance of an issue. Finally, Appendix P looks at whether the results are conditional on the structure of overall salience. Collectively, the core results we show below are robust to these alternative specifications, and we discuss deviations from them where relevant.

Results

Both the length of education‐related text in manifestos overall and in relation to the total length of manifestos has increased over time. Across our sample, we code an average of 17.1 quasi‐sentences on education in the 1950s and of 143.8 in the 2010s, showing an increase in the absolute length of education content. The relative share increased less sharply, from 7.1 per cent of manifesto content to a high of 10.6 per cent in 2000 (declining to 9.7 per cent in the 2010s). But how is attention distributed?

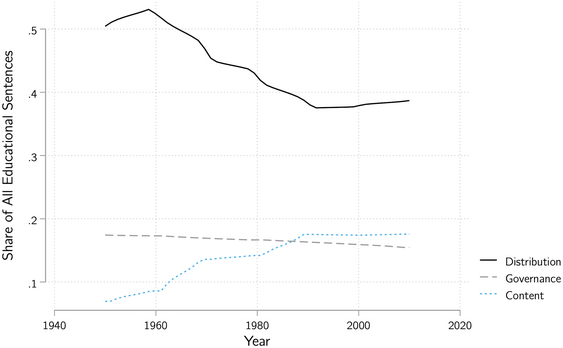

Figure 2 shows the share of education speech by broad sub‐dimension over time. Manifestos for Greece, Portugal and Spain are only available after these countries’ transition to democracy, thus the composition of countries changes in the 1970s (but the basic trends are similar when restricted to the non‐Southern countries). As Figure 2 indicates, distributive issues dominate the substance of speech in all periods. In the 1960s, 54 per cent of education mentions referred to access, funding, and de‐streaming, and although the share of these issues declined over time, they still accounted for 38 per cent of mentions in the 2010s. This finding corresponds to our expectations about the incentives for parties to foreground distributive issues. Governance and content issues account for a smaller share of the overall text. In the 1950s, when the religious ‘school wars’ still raged in Belgium, France and other parts of Europe, governance issues constituted close to a fifth of educational speech. This share fell to 15–17 per cent in subsequent decades. Overt attention to content, by contrast, was more limited in the 1950s and 1960s, when it accounted for 7 per cent of speech, rising to about 17 per cent in the 2010s (note that these shares sum to less than 100 per cent because some speech is devoted to questions of performance rather than policy).

Figure 2. Overall substantive attention to different policy areas.

Behind these aggregate patterns, however, we hypothesise critical differences in relative partisan and substantive mentions and stances taken, as summarised in Table 2. We now turn to examining these differences.

Distribution

We begin by regressing both substance (share of education mentions) and stance (positive shares) on partisanship interacted with decade dummies, allowing us to assess differences in party approaches over time (Appendix I shows the tabular results).

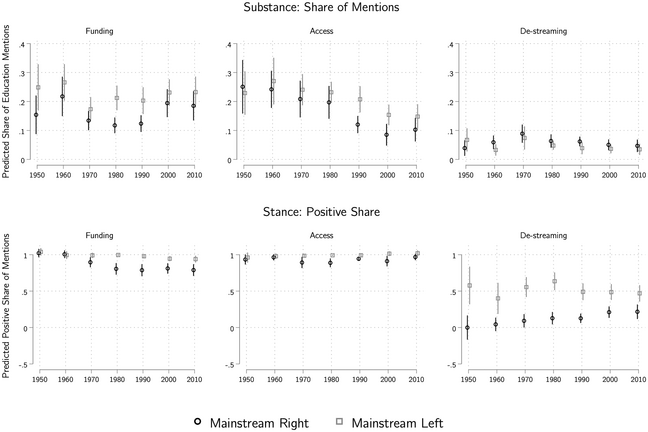

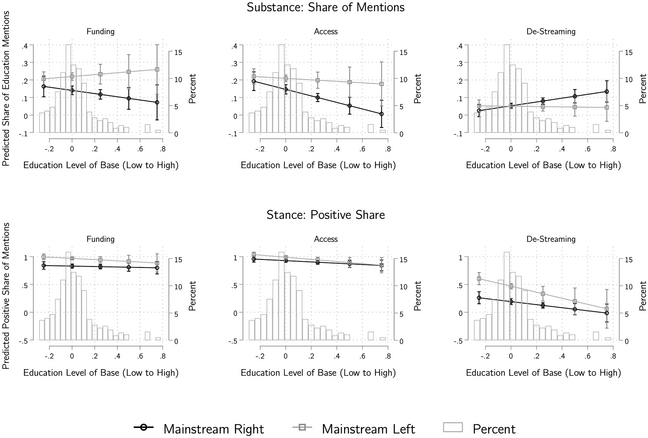

Figure 3 presents the results of this first analysis. In line with our expectations, it shows that distributive issues are characterised by consistent partisan differences, but of a different character depending on the issue. Across the full sample, left partisanship has a positive and statistically significant effect on mentions of both funding and access (Appendix I.1). However, as Figure 3 shows, these differences are concentrated in the 1980s and 1990s for funding and the 1990s to 2010s for access. In the 1950s and 1960s, the right devoted a similar amount of attention to funding and access as the left, but by the 1970s differences emerged in funding. These differences narrowed again in the 2000s, but emerged for access, suggesting that attention to these dimensions may be substitutive. When we look at the share of mentions of funding and access in the full manifesto text – not just the education sections – we see similar overall patterns (Appendix Table J.1), but left‐right differences in mentions are only significant at the 10 per cent level for funding from the 1980s to the 1990s and for access from the 1990s to the 2010s (Appendix J.1).

Figure 3. Substance and stance for distribution.

While the left is significantly more likely to mention funding and access positively, over 85 per cent of right parties’ mentions of funding and access are also positive. The core difference is thus one of differential salience: discussions of funding are overwhelmingly positive, but the left devotes between 20 and 40 per cent more text to discussing funding and access combined than the right. In the 2010s, funding and access combined accounted for a predicted share of 38.1 per cent of left educational speech, compared to 28.7 per cent of right educational speech. Given that left parties generally devote more attention to education, these differences contribute to much more left attention: the left devotes a predicted 33.6 statements to funding and access combined, compared to 14.5 statements by the right.

Discussions of de‐streaming, by contrast, are more polarised. The top right panel of Figure 3 shows that the left is only slightly less likely to mention de‐streaming. Both left and right mention it much less frequently than funding and access, but in equal measure. However, parties are much more distinct in their stances. The right is almost uniformly negative towards de‐streaming, while the left is on balance more positive. This constellation results in a more polarised pattern.

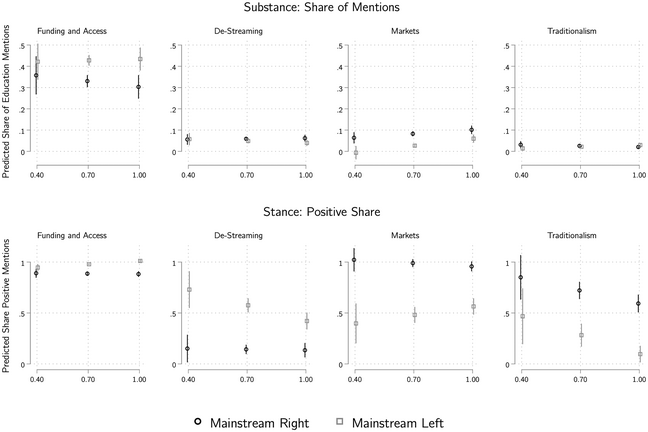

Do these differences vary systematically by party base? Figure 4 presents the results of our models interacting the educational structure of a party's base with both mentions and positive stances. If the cleavage structure matters, we would expect smaller differences where the right looks more ‘left’ in its base (more voters with lower formal education) and vice‐versa.

Figure 4. Substance and stance for distribution by party base.

Figure 4 provides some evidence in support of this claim, although the interaction terms are not always significant in the core models (Appendix I). The top row shows that the right's propensity to mention both funding and access decreases as its base becomes more highly educated, creating larger gaps in attention. The left, by contrast, is relatively consistent in mentioning both funding and access. Put differently, gaps between parties on substance (mentions) become larger where bases are more traditionally segmented, and these effects are largely driven by the right devoting less attention to funding and access where it has a more educated base. On the other hand, there are no significant differences in attention to de‐streaming.

Looking at stance, the bottom row, we see a different pattern. Here there are few differences in positive attention to funding or access. However, we see that the left becomes less positive towards de‐streaming as its base becomes more educated, leading to a more depolarised pattern.

Governance

Turning to issues of governance, we again see distinct patterns. We start with the same approach as above, regressing substance and stance on the interaction of partisanship and time.

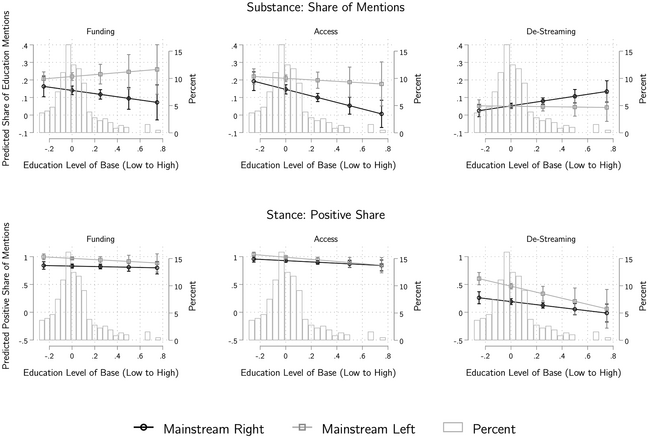

The top row of the middle and right panels of Figure 5 show, as predicted, more depolarised patterns of speech on decentralisation and participation. There are few partisan differences in the share of education mentions and in positive stances (there are some small differences when we look at decentralisation as a share of the full manifesto text – Appendix I.2). Left and right parties pay similar attention to these issues and take similar positions.

Figure 5. Substance and stance for governance.

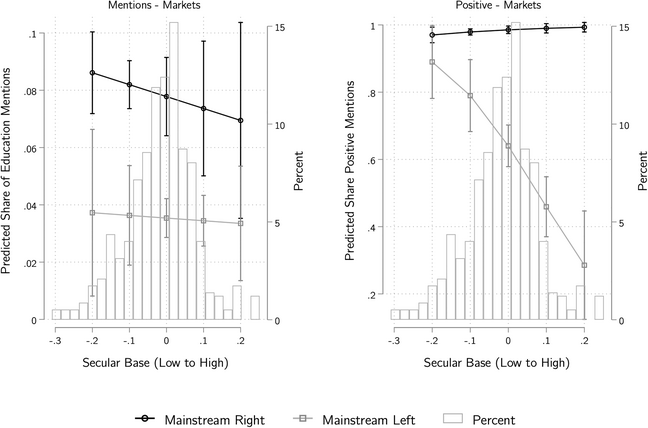

The discussion of markets is different. The left‐hand side of Figure 5 shows that the right is more likely to mention markets than the left (the results are similar, slightly less pronounced if we look at markets as a share of the full manifesto text, Appendix J.2). More importantly, the right mentions markets almost exclusively in positive terms. Here we see a pattern of open polarisation, which over time shades into a more differentially salient structure as the left adopts more positive stances. In the 1960s, the right mentioned markets more than the left – 3.2 per cent of educational text versus 1.3 per cent – and was dramatically more positive on the issue: 88 per cent of right mentions of markets are positive versus 43 per cent of left mentions. Over time, the positive gap narrows, with 72 per cent of left mentions of markets being positive in the 2000s, falling slightly in the 2010s.

We now probe these findings on markets more, looking at whether they differ where parties have more distinct religious bases (Appendix I.2 presents results for varying educational bases). Figure 6 shows the results. Because a linear model provides some out of sample prediction – more than 100 per cent shares positive – we use a fractional response model, but results are substantively similar with a linear model. The left‐hand side shows that there is little difference in the right's propensity to mention markets or take a positive stance as its base changes. The right‐hand side, however, shows that the left is less positive towards markets as its base becomes more secular, leading to more open polarisation. By contrast, the right remains uniformly positive towards markets regardless of changes in its base. Put differently, where markets overlay religious cleavages, speech is more polarised.

Figure 6. Substance and stance for markets by religious party base.

Content

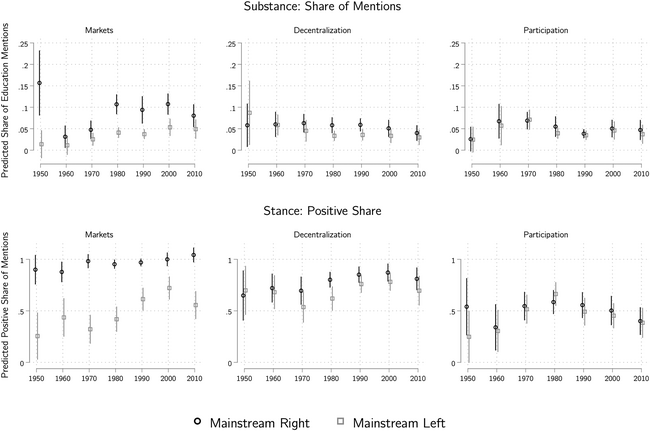

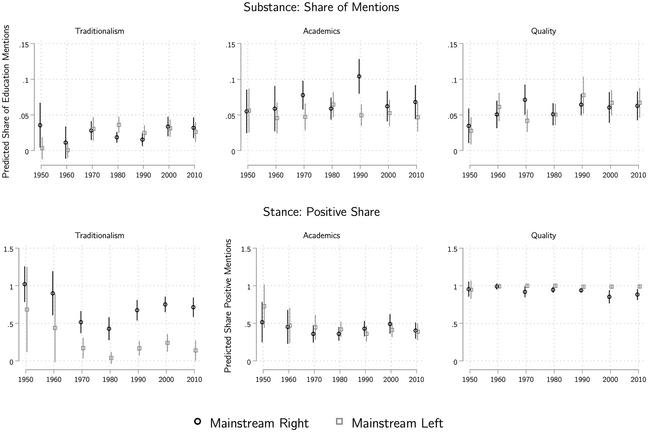

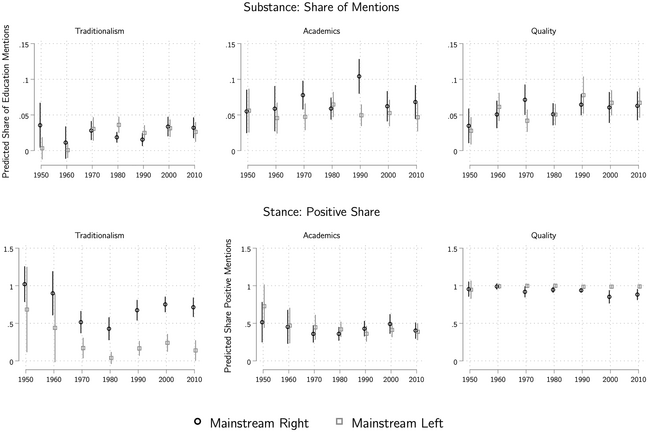

We now turn to content. As with governance issues, we find two distinct patterns. The middle and right panels of Figure 7 show a depolarised pattern for quality and academic focus. Attention increases over time, but shows few partisan differences – except in the 1980s, when academic content is associated with more right attention. Over the whole period, the left is statistically less likely to mention these issues, and to mention them positively, but the effect size is very small. Parties may still associate different goals or policy‐designs with quality and academic content (Gingrich & Giudici, Reference Gingrich and Giudici2023). However, their manifestos express similar levels of attention to these issues, with the right being a little less uniformly positive than the left.

Figure 7. Substance and stance for content.

For traditionalism, by contrast, we see a polarised pattern of left‐right speech. Figure 7 shows that there is no statistically significant difference in the likelihood of the left and the right mentioning traditionalism (top right), but there is a gap in positive mentions (bottom right). Over the whole time period, the right is more likely to mention traditionalism in a positive way, but these differences are concentrated in the post‐1960s period. Since the 1960s and 1970s, the left has adopted more overtly anti‐traditional rhetoric, while the right has not. In the 2000s and 2010s, the predicted share of positive statements about traditional content for the right was 71 per cent compared to 14 per cent for the left, while there were no significant differences in the number of mentions.

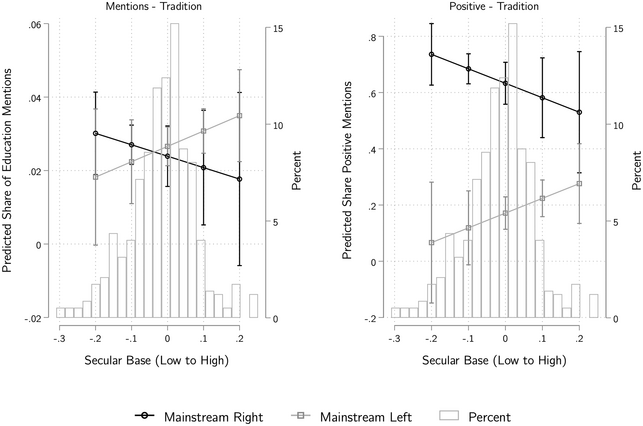

We now analyse whether mentions of traditional content vary across parties according to the religiosity of their base. Figure 8 shows a somewhat unexpected finding. Polarisation on traditionalism seems to be greater for parties with a more religious base – the opposite pattern to what we saw for markets. These results suggest, in line with expectations, that the right is more traditional when it has a less secular base. However, contra our expectations, they indicate that the left is less positive towards traditionalism when it has a less secular base. Whether these results suggest a propensity towards non‐religious traditionalism (for instance, regarding school discipline or secular national identities) or a competitive response in an electoral context increasingly shaped by cultural issues, in which left parties emphasise traditional content in order to attract voters with traditional values from the right (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Ingelhart2019), requires further analysis.Footnote 1

Figure 8. Substance and stance for traditional content by religious party base.

Over time changes

The above section showed three key findings: first, educational politics is multi‐dimensional; there is no single pattern of convergence or divergence in party attention or stances. Second, the politics of education is much ‘louder’ in some areas than in others, and third, these forces together create different patterns of education competition. This final section considers how these patterns have changed as education systems have expanded, potentially exerting the feedback effects identified by Garritzman (Reference Garritzmann2016) and others that reduce the incentives to discuss more entrenched issues, thereby increasing attention to other issues.

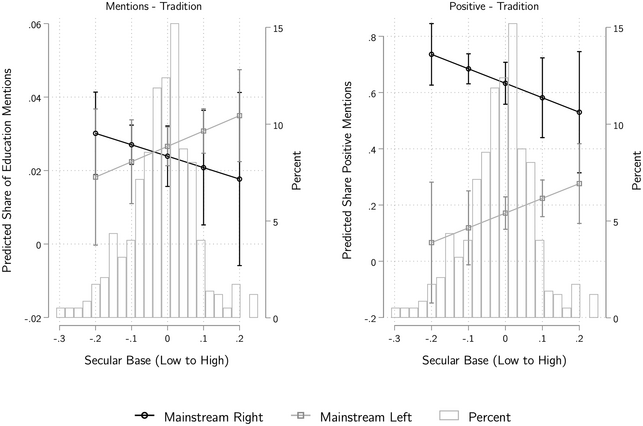

To engage in this task, we regress substance and stances on the interaction between partisanship and the share of secondary school enrolment, again with country and decade fixed effects and controls for employment/population, GDP per capita, and left incumbency. This model tests whether the entrenchment of particular institutional structures, proxied by the universality of secondary enrolment, reduces incentives for parties to mention issues that are increasingly popular but unattractive to their base (funding and access for the right) and increases incentives to move into new areas of debate (governance or traditionalism). Recall that we hypothesised that institutions would feedback on the distribution dimension, reducing the right's incentives to speak negatively about access, funding and de‐streaming over time, but we had less clear expectations about the other dimensions.

Figure 9 shows the results. As secondary education becomes more universal, moving from 40 to 100 per cent on the x‐axis, we see differences in the way parties relate to the system. To start with distribution. For ease of presentation, we combine the funding and access dimensions. Appendix I.3 shows the disaggregated results. While the interaction terms are not significant, when we plot the interactions, we see that at low levels of expansion there are no strong left‐right differences in mentions, but differences grow with expansion for both funding and access. This finding is consistent with Ansell's (Reference Ansell2010) and Garritzman's (Reference Garritzmann2016) hypotheses about time effects, suggesting that access issues become more ‘left’ as systems expand and expansion benefits more relatively disadvantaged citizens. While differences in stance also increase, they are less pronounced. When we look at de‐streaming, we do not see strong overtime shifts in substance, but there is a reduction of left‐right differences in stance.

Figure 9. Institutional expansion and stance.

The third panel shows that as school systems become more entrenched, differences in markets initially grow but then narrow slightly, both in terms of substance and stances. Differences in substance remain small for traditionalism, but grow in stance. These results suggest that the politicisation of educational issues changes over time as institutional coverage expands and the costs of change fall on different groups.

Discussion and conclusion

The above analysis showed that while the existing literature is correct in seeing an increase in the political salience of education over time, interpreting this increase as convergence is likely misleading. The amount of absolute attention devoted to education in manifestos has increased in the post‐war period, but parties do not use education speech to express only global and shared norms. Nor do they disagree on all aspects of education. Within each of the fundamental dimensions of education – its distribution, governance and content – parties emphasise some common issues and stances, but also express diverging priorities and stances.

Mapping and theorising these patterns required both theoretical and empirical innovation. First, we relied on policy‐specific literature to develop and apply a new multidimensional coding of educational speech. This approach allowed us to measure parties’ mentions of and stances on fundamental educational issues, providing a more accurate picture of how parties approach education than existing measurements of positions on spending or overall mentions of education.

Second, to theorise the resulting patterns of politicisation, we combined insights from the literature on party congruence with educational literature outlining the distributive and cultural implications of each issue. The analysis shows that we can anticipate patterns of politicisation by considering that non‐niche parties use political speech to appeal to both their core constituencies and the general electorate. Parties are more likely to take diverging positions on issues that are highly salient to their base and on which they face few electoral penalties. In the case of education, these issues include both cultural issues (support for traditional content) and distributive issues (de‐streaming), with our detailed analysis showing a correlation between the stances parties take and their electoral base.

These findings provide important insights into the nature of manifestos as a source of political speech. They add further evidence that existing aggregate manifesto studies overestimate the degree of cross‐party consensus on issue‐specific priorities and stances (Gemenis, Reference Gemenis2013). Parties may agree that education is important, but still hold different views on which education‐related issues need to be addressed and how to solve them. Our findings support recent research showing that parties, including mainstream parties, consider both the general electorate and their core constituencies when adjusting and crafting their public positions (Dassonneville, Reference Dassonneville2018; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2014).

Our analysis links educational speech to electoral cleavages both theoretically and empirically. However, other factors influence how parties choose to address education rhetorically, most importantly the institutional context to which they refer. To compare stances across place and time, our analysis neglects the fact that pro‐market statements in one country may be seen as anti‐market in another, a ‘status‐quo problem’ that affects comparative manifesto research more generally (Dancygier & Magalit, Reference Dancygier and Margalit2020; Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020). Our analysis also cannot directly capture how partisan speech relates to institutional change and variation (Garritzmann, Reference Garritzmann2016; Jungblut, Reference Jungblut2017). It seems plausible that the successful expansion of secondary education has shifted parties’ attention to the areas of governance and content and that this, together with the growing importance of cultural cleavages, is fuelling the raising salience and polarisation of traditional content (see also Berg et al., Reference Berg, Jens and Jupskås2023).

Building on our findings, future research might therefore want to explore other factors that shape parties’ rhetorical repositioning and the shift from first to second‐order preferences. In addition to institutional variation and its historical legacies, these factors may include the influence of ‘opinion leaders’ (Adams & Ezrow, Reference Adams and Ezrow2009), aligned stakeholders (Giudici et al., Reference Giudici, Gingrich, Chevalier and Haslberger2023) and strategic competitive reactions. The EPD offers a novel source of empirical data to test these and other hypotheses. It could also be extended to include niche parties to examine the extent to which a stronger policy orientation affects parties’ rhetorical approach to education (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Jens and Jupskås2023).

Parties tend to implement what they promise in their manifestos (Ansell, Reference Ansell2010; Klingemann et al., Reference Klingemann, Hoffebert and Budge1994; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson2017). However, political institutions and majorities can change the extent to which they may feel compelled to deliver on their promises (Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005; Jungblut, Reference Jungblut2017). By focusing on the relationship between electoral composition and political rhetoric, this analysis does not link rhetoric to reform. Further research is therefore needed to identify the extent to which electoral promises change as they are concretised into more public facing appeals (e.g., in the media), and policy proposals and reforms, for instance in deciding whether to prioritise education or other areas of funding. Comparing positions expressed in manifestos with those contained in coalition agreements and government programmes would be one way of learning more about how parties navigate trade‐offs and prioritise educational preferences.

If we view manifestos as a window into the issues and stances that parties want the electorate to associate with them (Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2014), our analysis finds that parties’ educational stances on both cultural and redistributive issues are correlated with broader electoral divisions. Such divisions are currently changing, with a growing body of literature identifying education as an increasingly salient electoral cleavage – shaped by economic and especially cultural attitudes (Attewell, Reference Attewell2021; Ford & Jennings, Reference Ford and Jennings2020; McArthur, Reference McArthur2023; Simon, Reference Simon2022) as well as group identities (Stubager, Reference Stubager2009). These developments raise the question of whether, as in the era of state‐building, we will see polarisation around an increasing range of educational issues – and cultural issues in particular, as seen recently in the politicisation of education by the far right (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Jens and Jupskås2023). Analysing how parties structure the education debate is crucial if we are to understand parties’ rhetorical and programmatic responses to such electoral shifts, and thus the politics of public policy reform that will structure future electorates. Our database and theoretical approach offer a novel and multi‐dimensional means for such analysis, which future scholarship can extend in time and scope.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ben Ansell, the participants of the Oxford Schoolpol Workshop, and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments on this paper, all errors are our own. We thank the research assistants involved in the dataset construction (see appendix). Research for this article is supported with funding from the European Research Council (ERC) with a Starting Grant for the project The Transformation of Post‐War Education: Causes and Effects (SCHOOLPOL) and we thank the ERC for its financial support.

Data availability statement

The dataset (EPD) and replication materials are available in the Harvard Dataverse https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/C761QS. We have uploaded an Appendix explaining the coding process and variables in detail.

Funding statement

Research for this article is supported with funding from the European Research Council (ERC) with a Starting Grant for the project The Transformation of Post‐War Education: Causes and Effects (SCHOOLPOL) (grant number 759188).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was not required for this study of party manifestoes, which did not involve human subjects. Research for this study is supported by the ERC, which received approval by the Departmental Research Ethics Committee (Politics & International Relations, University of Oxford).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting Information