In recent decades, nongovermental organizations (NGOs) have become a powerful political force in countries that receive foreign aid. The rise of NGOs as major political actors was driven largely by bilateral donors, who dramatically increased the share of aid channeled through NGOs.Footnote 1 Whether to bypass corrupt governments or to directly empower civil society, donors have relied on a growing number of both international and local NGOs to implement aid projects.Footnote 2

Importantly, NGOs engage in activities that can both benefit and threaten political incumbents. On the one hand, many NGOs provide services that improve citizen well-beingFootnote 3 and yield political benefits for national incumbents.Footnote 4 NGOs can also strengthen ties between citizens and the stateFootnote 5 and bolster states’ international standing.Footnote 6 On the other hand, NGOs have been a force for democratic accountabilityFootnote 7 credited with public mobilization ranging from higher voter turnout and local land disputes all the way to regional “color revolutions.”Footnote 8

In response to the sector’s destabilizing potential, many governments have adopted “NGO laws” that provide administrative means to crack down on activities incumbents find threatening.Footnote 9 These laws emerged over the last fifteen yearsFootnote 10 and have proliferated most dramatically in aid-receiving countries.Footnote 11 Research has found that these laws work as intended, reshaping the NGO sector by driving out NGOs working on human rights and discouraging domestic and international civil society groups from engaging in politically sensitive activities.Footnote 12 Clearly, these laws threaten the interests of donors who value democracy promotion by constraining such activities and increasing administrative burdens on their implementing partners.

How have bilateral donors responded? Research has focused on explaining cross-country variation in the adoption of NGO lawsFootnote 13 and why governments use administrative rather than violent means of repression.Footnote 14 However, relatively little research has considered the response of donors.Footnote 15 We argue that donor response to illiberal NGO legislation hinges on the donor’s commitment to funding democracy promotion, typically understood as aid allocated to inclusive governance, civil society, and human rights. Specifically, we expect restrictive NGO laws to have a greater impact on the behavior of these “democracy-oriented” (DO) donors than on donors that prioritize services and infrastructure (non-DO donors).

Why might DO donors be more responsive to NGO laws? On the one hand, by erecting new barriers to democratic governance, NGO laws explicitly threaten the programmatic objectives of DO donors. As a result, we might expect DO donors to “push back” by increasing the volume of aid allocated to democracy promotion. Initiatives such as the United States’ Stand with Civil Society agenda, which calls for “coordinated action to support and defend civil society” amid increasing restrictions on freedom of association and assembly, give the impression that DO donors respond to closing civic space by channeling more resources to democracy promotion.Footnote 16 At the same time, NGO laws reduce the delivery capacity of DO donors more than other donors. DO donors channel more aid through NGOs than non-DO donors, and NGO laws typically include vague provisions that enable selective enforcement, targeting NGOs engaged in contentious human rights activities while sparing those providing services.Footnote 17 By differentially increasing the cost of democracy promotion, NGO laws may prompt DO donors to “back down” and devote less aid to democracy promotion.

To test heterogeneity in donor responses to NGO laws, we aggregate data on commitments for over 2 million aid projects from OECD donors, calculating the amount of aid channeled annually to democracy promotion or economic development (including services and infrastructure) for each donor–recipient dyad from 2005 through 2019. Combining data on aid with an original data set of restrictive NGO laws, we use event study, standard two-way fixed-effects models, and the generalized synthetic control (GSC) method to estimate the effect of NGO law enactment on sectoral aid flows.

We find that DO donors decrease their spending on democracy-promotion projects by 70 percent in the years after the passage of a restrictive NGO law. This is equivalent to a USD 3.3 million annual reduction in funding for democracy promotion for the average law-passing dyad. Furthermore, these decreases persist across the full post-treatment years in our sample, indicating a long-term negative effect on democracy funding. Some models suggest that DO donors also reduce their economic aid, but the results are inconsistent and the effect sizes smaller. Meanwhile, NGO laws have no impact on aid allocated by non-DO donors.

Our approach improves on previous analyses of NGO laws and aid flows in at least three ways.Footnote 18 First, we significantly expand both the geographic and temporal coverage of data on NGO laws,Footnote 19 identifying over fifty significant and restrictive NGO laws enacted in OECD recipient countries between 2005 and 2019. Second, by conducting the analysis at the donor–recipient dyad level, we account for theoretically important heterogeneity in the response of donors that prioritize different types of aid. Third, our GSC models allow us to estimate how the effect of anti-NGO laws evolves over the six years after laws are enacted, providing a more dynamic picture of donor responses over time.Footnote 20

This paper contributes new theory and evidence on the strategic behavior of bilateral donors in the face of illiberalization. A substantial body of work suggests that bilateral aid allocations often reflect donors’ strategic, economic, and political interests more than their ideological commitments to democracy and human rights,Footnote 21 especially during periods of heightened geopolitical competition.Footnote 22 Echoing findings on preferential trade agreements and human rights treaties,Footnote 23 DO donors’ retreat from democracy assistance may reflect their belief that aid-receiving governments are more willing to forfeit aid and trade than the repressive measures that help them consolidate power. More broadly, our results reinforce previous findings that donors are more strategic than ideological, emphasizing the challenges international actors face in stifling illiberal behavior by governments.Footnote 24

Our findings also cast doubt on the ability of NGOs in repressive countries to leverage transnational networks and mobilize international pressure in ways that change regime behavior. While some evidence suggests that donors punish states for severe human rights violations,Footnote 25 we do not see evidence that similar measures are taken to deter the “administrative crackdowns” imposed by anti-NGO legislation.Footnote 26 Because foreign donors provide most of the funding for many recipient-country NGOs,Footnote 27 reductions in support for democracy promotion may further degrade their ability to engage in international outreach in the wake of these laws.

Finally, our findings have important implications for donors seeking to counter backsliding among aid-receiving regimes. Our finding that the donors most committed to democracy promotion back down in the face of administrative crackdowns on their development partners suggests that from the perspective of aspiring autocrats, NGO laws have been “successful.” In fact, this donor behavior creates strong incentives for governments in aid-receiving countries to use legal measures to crack down on civil society. In the wake of these laws, support for democracy promotion decreases, yet the regimes see little or no corresponding reduction in economic aid.

Given recent reductions in aid by the United States and other OECD donors, understanding the effect of these cuts on domestic civil society is more important than ever. Far from an anomaly, recent aid cuts highlight the broader trend this paper identifies: the space for international democracy assistance is shrinking, not only because of actions by recipient governments, but also because donors are increasingly unwilling or unable to push back.

Bilateral Aid and NGO Laws

Over the last three decades, the prominence of NGOs in international development has increased dramatically. This has been driven by two factors. First, rising concerns about the misuse of foreign aid by recipient governments led donors to embrace NGOs as convenient means to “bypass” the public sector in the implementation of aid projects.Footnote 28 In diverting aid from governments to nonstate organizations, donors helped facilitate a proliferation of NGOs in aid-receiving countries where domestic sources of funding were (and remain) scarce.Footnote 29

Second, an increased reliance on NGOs for aid delivery coincided with a growing interest among donors in democracy promotion. After the Cold War, as donors began to prioritize funding for political advocacy work around human rights, government transparency, and election monitoring,Footnote 30 NGOs were seen as a critical ingredient in fostering liberal democracy.Footnote 31 A surge in aid gave rise to domestic NGOs that could advocate for change domestically while also tapping into transnational advocacy networks to publicize undemocratic behavior and generate international pressure on repressive governments.Footnote 32

While aid-receiving governments have generally welcomed the growing role of NGOs in providing services like health care and education,Footnote 33 many are less enthused by the increased availability of resources for NGOs working to mobilize citizens and advocate for political change, or what is commonly referred to as democracy promotion.Footnote 34 In response to the growing influence of NGOs, aid-receiving governments—especially those engaged in democratic backsliding—have increasingly turned to restrictive legislation, or “NGO laws,” to regulate the third sector. Between 2005 and 2019, sixty countries receiving bilateral aid from OECD donors passed at least one law imposing significant restrictions on NGOs (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Restrictive NGO law passage in aid-recipient countries, 2005 to 2019

These laws typically erect barriers to NGO registration and expand government oversight of NGO operations, increasing the state’s discretion to target specific NGOs for regulatory noncompliance. Also, many laws explicitly bar organizations from engaging in activities deemed “political” or threatening to “national interests.” For example, NGO laws in Cambodia, Russia, and Egypt all contain clauses empowering the government to revoke the registration of NGOs found to compromise “national unity,”Footnote 35 while the 2016 Foreign Donations Regulation Act in Bangladesh grants the government authority to shut down NGOs that make derogatory remarks about “constitutional bodies,” including the parliament, the election commission, and the judiciary.Footnote 36

In effect, NGO laws provide incumbents with tools for selective enforcement against organizations engaged in activities perceived as incompatible with the regime’s interests, creating substantial barriers to organizations engaged in democracy promotion.Footnote 37 In Algeria, commentators have described government officials as wielding the restrictive 2012 Law on Associations as “a Damocles sword hanging over independent associations that they dislike,”Footnote 38 with officials using regulations on legal registration to force the closure of two prominent and long-standing women’s rights organizations.Footnote 39 But the effects of NGO laws extend beyond those organizations directly targeted for closure. Crackdowns on civil society generate fear and uncertainty that can prompt organizations to preemptively disengage from activities that may attract negative attention, as in Turkey, where commentators described the arbitrary enforcement of NGO regulations as a “cost-effective tactic” prompting “large numbers of actors to impose self-censorship through a limited number of high-profile arrests and closures.”Footnote 40

By increasing uncertainty around the range of permissible activities, or outright repressing some activities, NGO laws erect barriers to the provision of democracy-promotion aid, a central component of many Western donors’ aid portfolios since the Cold War.Footnote 41 Thus, many donors—particularly those that have historically prioritized democracy promotion—have been vocal about countering administrative repression by doubling down on aid for civil society, democracy, and human rights.

Among the most outspoken donors on the issue of closing civic space, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency named “promoting an enabling environment for civil society” in response to restrictive legislation as one of its two highest priorities for 2016–2022.Footnote 42 Its support for initiatives such as the Regional Civil Society Development Hub—a SEK 22 million (USD 2.3 million) project aimed at enhancing the resilience of civil society organizations in the Western Balkans—exemplifies how increasing restrictiveness can prompt pushback from the most committed donors.Footnote 43 Similarly, USAID included the issue of closing civic space in its strategy on Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance to start in 2013.Footnote 44 The EU continued its support of democracy promotion in restrictive environments through a variety of mechanisms,Footnote 45 ranging from the creation of a 15 million (USD 17 million) fund to provide emergency support for human rights defenders,Footnote 46 to negotiating an agreement to allow EU funding to bypass Ethiopia’s draconian restrictions on NGOs’ access to foreign funding.Footnote 47

But despite stated commitments to push back against legal restrictions on civil society, practical considerations may hinder donors’ ability or willingness to sustain democracy promotion in the face of NGO legislation. Most straightforwardly, by imposing restrictions on organizations’ operations and funding, NGO legislation directly limits the extent to which donors can deliver aid through local partners. In Uzbekistan, for example, NGO funding regulations resulted in the obstruction of 80 percent of grants from foreign donors to local organizations.Footnote 48 Even where laws do not impose direct restrictions on funding or activities, the increased scope for selective enforcement may discourage NGOs from more contentious projects or donors,Footnote 49 reducing donors’ ability to implement democracy-building projects through third-sector partners.

NGO legislation may also signal recipient governments’ resolve to undermine democratic accountability, causing donors to conclude that democracy aid is no longer achieving its goals. Despite its role as one of the core supporters of democracy programming in Cambodia, Sweden ended all bilateral development support for that country in 2024.Footnote 50 The decision, made after a variety of attempts to reconfigure aid to the country in the context of closing civic space, was widely viewed as a result of a lack of positive change in democracy and human rights in the country.Footnote 51

Finally, donors may back down to avoid straining diplomatic relations with strategically important governments. Carothers notes that “a common response of essentially all assistance organizations faced with newly restrictive environments is to examine what they are doing in those places and consider whether they should stop funding certain groups, cease sponsoring certain activities, or otherwise curtail their activities to avoid triggering negative reactions.”Footnote 52 Further, “a strong desire to maintain good relations with partner governments” can prompt donors to scale back on politically sensitive programming.Footnote 53 As a result, some commentators have concluded that increasingly restrictive environments are pushing donors “even further in the direction of development cooperation and away from active democracy support.”Footnote 54

Anecdotal evidence thus provides conflicting accounts of donor response to NGO laws. Donors’ strong condemnations of NGO legislation, combined with intentional efforts to channel support to civil society, suggest that the donors who prioritize democracy assistance take an active role to bolster civil society amid administrative crackdowns. However, qualitative accounts of NGO laws argue that scaling back, rather than pushing back, is the norm. Thus, the question remains: how do donors respond to restrictive NGO legislation? In the next section, we detail two competing empirical expectations of how the donors most committed to democracy assistance respond to the pressures NGO laws impose on their aid strategies.

Heterogeneous Responses to NGO Laws

Bilateral donors can take drastically different approaches to foreign aid, including the institutions through which aid is channeled,Footnote 55 the provision of grants versus loans,Footnote 56 the geographic regions donors target,Footnote 57 the extent to which donors are altruistic versus self-interested,Footnote 58 and the prioritization of different programmatic sectors.Footnote 59 We argue that donors’ differences on this latter characteristic—their prioritization of programs in the democracy sector in particular—will condition their response to NGO legislation.

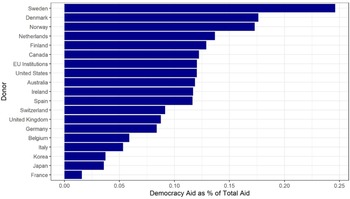

Figure 2 shows the share of total aid allocated to democracy activities among large OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors. Sweden is the most democracy oriented, allocating nearly 25 percent of total aid to democracy promotion, in contrast to France’s less than 2 percent. The most democracy-oriented donors align with the group of donors commonly referred to as the “like-minded” countries: Sweden, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, and Canada.Footnote 60 However, the “big donors”—the US, UK, Germany, France, Italy, and Japan—range from strongly democracy oriented (US) to relatively averse to democracy promotion (Italy, Japan, France).

Figure 2. Democracy aid as a share of total aid from large OECD donors, 2005 to 2019

We argue that donors’ relative prioritization of democracy aid conditions their motivation and capacity to respond to NGO laws. By definition, DO donors invest more resources in democracy promotion abroad than their non-DO counterparts. By both signaling a weakening of democratic rule and erecting barriers to democracy promotion in aid-receiving countries, NGO laws pose a greater threat to the foreign policy objectives of DO donors, likely increasing their motivation to push back against increasing restrictiveness.

DO donors are also better equipped than their less democracy-minded counterparts to adapt to more restrictive legal environments. DO donors are likely to have a larger network of advocacy partners, providing ready alternatives if partner NGOs are shut down, enabling “experimentation” with effective resistance strategies,Footnote 61 and enabling networks of resistance to NGO laws.Footnote 62 Similarly, a track record of supporting democracy-promotion activities requires certain skills that could enable resistance, such as retaining legal experts, adopting encrypted communications and security systems, providing psychosocial support and protection for staff, and training staff to de-escalate conflicts with local authorities.Footnote 63

The assertion that DO donors have both the motivation and the capacity to double down on democracy in the context of closing civic space corresponds to the following empirical expectation:

“Push back” expectation: Following the passage of a restrictive NGO law, DO donors will increase their democracy assistance.

Although DO donors have greater motivation and capacity to protest against NGO laws, they may also face dramatically increased costs for continued prioritization of democracy promotion. First, NGO laws can disrupt DO donors’ aid delivery chains, as NGO laws are often selectively enforced to target the advocacy NGOs on which these donors rely for the implementation of democracy programming.Footnote 64 NGOs that receive funding from DO donors are often subject to especially aggressive repression, making them more likely to shut down or to seek work that is less likely to provoke the regime.Footnote 65

Restrictive NGO laws may also signal the resolve of aid-receiving governments to suppress political dissent, leading donors to question the utility of democracy promotion in the face of concerted resistance. DO donors may conclude that the returns on investments in advocacy are too small or decide to prioritize the preservation of bilateral relations by reducing advocacy work while maintaining other forms of aid.Footnote 66 Non-DO donors with smaller advocacy portfolios composed of less contentious activities are unlikely to face these pressures.

The assertion that DO donors face steep costs to continued prioritization of democracy aid corresponds to the following alternative empirical expectation:

“Back down” expectation: Following the passage of a restrictive NGO law, DO donors will reduce their democracy assistance.

Data and Measurement

To test these competing expectations about how donors respond to NGO laws, we compiled a dyadic data set of yearly aid flows from nineteen large DAC donors to 110 recipient countries from 2005 to 2019.Footnote 67

Identifying Restrictive NGO Legislation

Our key independent variable is the passage of a significant, restrictive NGO law in an aid-receiving country. Partnering with the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), we compile an original data set on legal measures—including laws, amendments, and executive decrees—enacted between 2005 and 2019 that have a direct and restrictive impact on NGOs. To code whether each legal measure is direct and restrictive, we rely on contemporaneous reporting from organizations (including ICNL, CIVICUS, and USAID), local and international news sources, and academic reports. We designate legal measures as direct when contemporaneous reports expect the legislation to have a significant impact on NGOs’ ability to operate in the country, including registering, securing funding from local and international sources, and/or implementing its desired programming. We designate them as restrictive (as opposed to enabling) when contemporaneous reports indicate that the law is likely to increase the difficulty of operating in the country.Footnote 68 Appendix C gives a complete list of legal measures included in the data set. The variable ngo law is an indicator that takes the value of 1 in all dyad-years after the passage of a restrictive NGO law in the recipient country.Footnote 69 Figure 3 plots treatment onset for the 110 aid-receiving countries in our sample.

Figure 3. Treatment status of aid-recipient countries, 2005 to 2019

Categorizing Aid Flows

To measure aid flows, we aggregate project-level data on aid commitments in constant USD from over 2 million projects funded by DAC donors in the OECD’s Creditor Reporting System. Each project is put into one of three categories—democracy aid, economic aid, or other aid—using the five-digit purpose code attached to the project. Democracy aid comprises projects aimed at democratic participation and civil society, human and women’s rights, labor rights, media, elections, conflict prevention, legal reform, and anti-corruption.Footnote 70 Economic aid captures commitments to projects involving education, health, water and sanitation, transportation, agricultural development, housing, food security, and government administration. Effectively, this includes all projects for which a single sector is specified that are not categorized as democracy aid. Projects listed under multi-sector purpose codes or projects for which the sector is not specified are classified as “other.”

Because democracy and economic aid flows are highly skewed and contain meaningful zero-values, we use a log(y + 1) transformation for all outcome variables in our core results. To ensure that our findings are robust to other transformations commonly used in the aid literature, we also report our findings when using a log transformation that excludes dyads with zero-values, which would understate the true effect size if some donors reduce their democracy commitments to zero in years after an NGO law, and when using an inverse hyperbolic sine transformation, which is defined for zero-values but difficult to interpret for large coefficients.

Measuring Democracy Orientation

We measure the democracy orientation of donors in two ways. First, we estimate the extent to which a donor’s recent global aid portfolio emphasizes democracy aid. The variable democracy-oriented donor, or dod, takes a value of 1 for dyad

![]() $ij$

in year

$ij$

in year

![]() ${Y_0}$

if the share of all aid commitments allocated to democracy aid from donor

${Y_0}$

if the share of all aid commitments allocated to democracy aid from donor

![]() $i$

to all recipient countries in the years

$i$

to all recipient countries in the years

![]() ${Y_{ - 3}}$

to

${Y_{ - 3}}$

to

![]() ${Y_{ - 1}}$

is in the seventy-fifth percentile of all donors. This measure, which varies within donors over time, captures the overall democracy orientation of donors for each year, averaging across all recipients. Supplemental Table A4 reports DO donors for each year.

${Y_{ - 1}}$

is in the seventy-fifth percentile of all donors. This measure, which varies within donors over time, captures the overall democracy orientation of donors for each year, averaging across all recipients. Supplemental Table A4 reports DO donors for each year.

However, dod may be a poor indicator of a donor’s support for democracy in a particular recipient country. Strategic considerations in specific countries may override a donor’s general aid priorities, as has been the case with US support for countries like Uganda and Ethiopia where counterterrorism often takes precedence over democracy promotion,Footnote 71 or can result in different aid policies on a country-by-country basis, as with the European Union’s substantial support for good-governance programs in the early 2000s in Azerbaijan and Ukraine, but not in nearby Afghanistan or Russia.Footnote 72

To account for the highly contextual nature of donor priorities, our second measure estimates the time-invariant orientation of each dyad based on the composition of aid for that dyad in the years prior to law passage.Footnote

73

democracy-oriented relationship (dor) is set to 1 for dyad

![]() $ij$

if the share of aid allocated to democracy-promotion projects from donor

$ij$

if the share of aid allocated to democracy-promotion projects from donor

![]() $i$

to recipient

$i$

to recipient

![]() $j$

in the year of and two years prior to law passage is above the seventy-fifth percentile of all donors to recipient

$j$

in the year of and two years prior to law passage is above the seventy-fifth percentile of all donors to recipient

![]() $j$

over the same period. See supplemental Table A3 for a full list.

$j$

over the same period. See supplemental Table A3 for a full list.

Estimation

Our outcome variables are total dyadic aid commitments, aid commitments to democracy projects, and aid commitments to economic projects. Our independent variable is the passage of a significant, restrictive NGO law in the recipient country. By hypothesis, the effect of NGO law passage on dyadic aid flows is conditional on the donor’s past prioritization of democracy aid, which we operationalize at both the donor and dyad levels, as just described.

To estimate the effect of NGO laws on aid flows, we estimate “static” two-way fixed-effects models.Footnote 74 To model heterogeneity in donor response, we interact the treatment indicator with the indicator for the democracy orientation of the dyad or donor. As “treatment” (law passage) is assigned at the recipient-country level, we cluster our standard errors by recipient for all models. We estimate the following models:

where

![]() ${Y_{ij,t}}$

is the outcome of interest at time

${Y_{ij,t}}$

is the outcome of interest at time

![]() $t$

for the dyad containing donor

$t$

for the dyad containing donor

![]() $i$

and recipient

$i$

and recipient

![]() $j$

; postpassage is a dummy that takes the value of 1 for dyad

$j$

; postpassage is a dummy that takes the value of 1 for dyad

![]() $ij$

in the post-law-passage period and 0 otherwise;

$ij$

in the post-law-passage period and 0 otherwise;

![]() ${\rm{do}}{{\rm{r}}_{ij}}$

is a time-constant, binary variable equal to 1 if the dyad

${\rm{do}}{{\rm{r}}_{ij}}$

is a time-constant, binary variable equal to 1 if the dyad

![]() $ij$

is coded as democracy oriented at the time of law passage;

$ij$

is coded as democracy oriented at the time of law passage;

![]() ${\rm{do}}{{\rm{d}}_{it}}$

is a time-varying, binary variable equal to 1 if the donor

${\rm{do}}{{\rm{d}}_{it}}$

is a time-varying, binary variable equal to 1 if the donor

![]() $i$

is coded as democracy oriented in the year

$i$

is coded as democracy oriented in the year

![]() $t$

; and

$t$

; and

![]() ${\alpha _{ij}}$

,

${\alpha _{ij}}$

,

![]() ${\mu _i}$

, and

${\mu _i}$

, and

![]() ${\lambda _t}$

are fixed effects that control for time-invariant confounders across dyads, donors, and years, respectively.

${\lambda _t}$

are fixed effects that control for time-invariant confounders across dyads, donors, and years, respectively.

We estimate these models on a panel data set containing all dyads in which the recipient passed a restrictive NGO law during the study period. By excluding “never-treated” units from the analysis, we avoid the assumption that countries that do not pass restrictive NGO legal measures serve as valid counterfactuals for countries that do. However, recent work has suggested that the exclusion of never-treated units in the event-studies framework can lead to under-identification.Footnote 75 In Appendix F1, we show that our findings are robust to the inclusion of never-treated dyads in a staggered difference-in-differences design.

We also test our hypothesis using the GSC method. Like conventional synthetic control, GSC constructs a synthetic counterfactual for treated units through a weighted combination of never-treated units. However, GSC uses an interactive fixed-effects model to estimate latent factors that inform the weighting scheme, reducing bias. The method also allows units with heterogeneous treatment timing to be incorporated into a single model and produces straightforward frequentist uncertainty estimates using a parametric bootstrap procedure.Footnote 76

Drawing from the literature on the determinants of aid flows, we use the following variables as predictors in generating weights: the recipient country’s GDP per capita (logged), liberal democracy index and measure of civil society repression from V-Dem,Footnote 77 human rights score,Footnote 78 prevalence of civil conflict,Footnote 79 and deaths from natural disasters from EM-DAT,Footnote 80 as well as dyadic trade flows as compiled by CEPII.Footnote 81 To ensure we have sufficient data to generate plausible control units, we remove from the analysis any treated dyads with less than five pre-treatment periods and one post-treatment period, resulting in a sample of 756 treated and 1,584 control dyads. To compare DO donors’ response to law passage to that of other donors, we partition treated dyads into two subsamples: dyads with DO donors and dyads with non-DO donors.Footnote 82 We then estimate the GSC models separately on each subsample, taking all never-treated units as potential controls.

Results

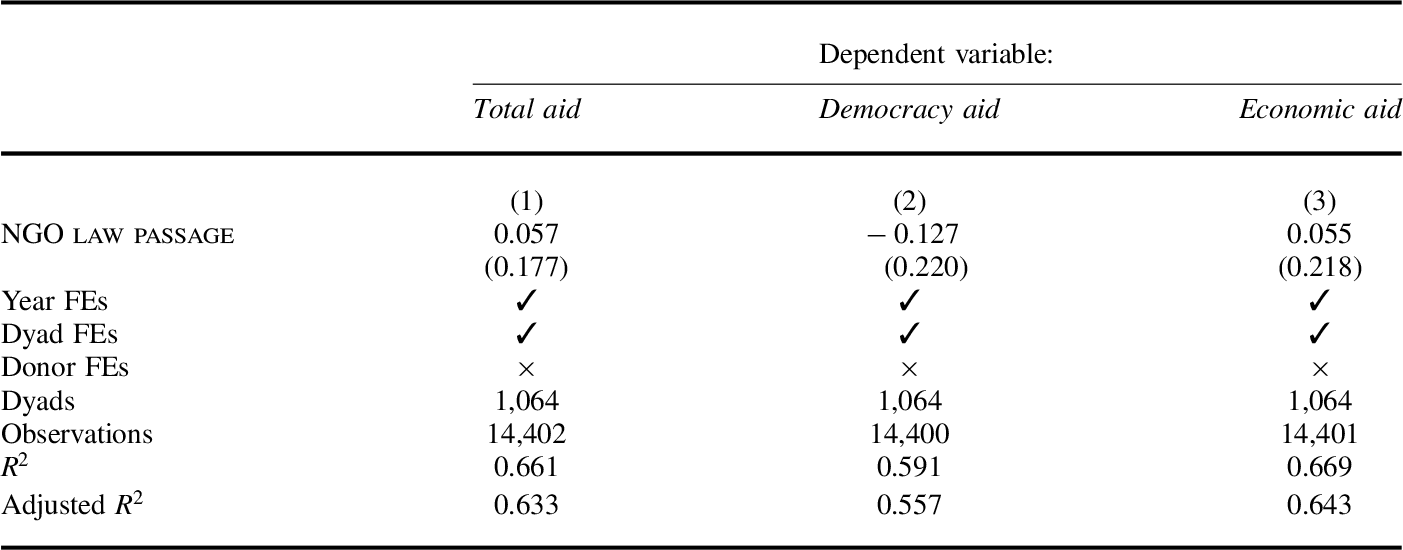

First, we estimate the effect of restrictive NGO laws on overall flows of total aid, democracy aid, and economic aid (Table 1). The coefficient on ngo law passage can be interpreted as the average within-dyad change in aid commitments following the enactment of an NGO legal measure. Consistent with our expectation that response to NGO laws will be conditioned on the democracy orientation of the donor, we find that the passage of an NGO law has no effect on total aid flows among all donors in general and a negative but insignificant effect on aid to the democracy sector.

Table 1. All donor responses to NGO law passage

Notes: *

![]() $p \lt .1$

; **

$p \lt .1$

; **

![]() $p \lt .05$

; ***

$p \lt .05$

; ***

![]() $ \lt .01$

. Robust standard errors clustered by recipient country. Dependent variables are logged using a

$ \lt .01$

. Robust standard errors clustered by recipient country. Dependent variables are logged using a

![]() ${\rm{log}}\left( {y + 1} \right)$

transformation.

${\rm{log}}\left( {y + 1} \right)$

transformation.

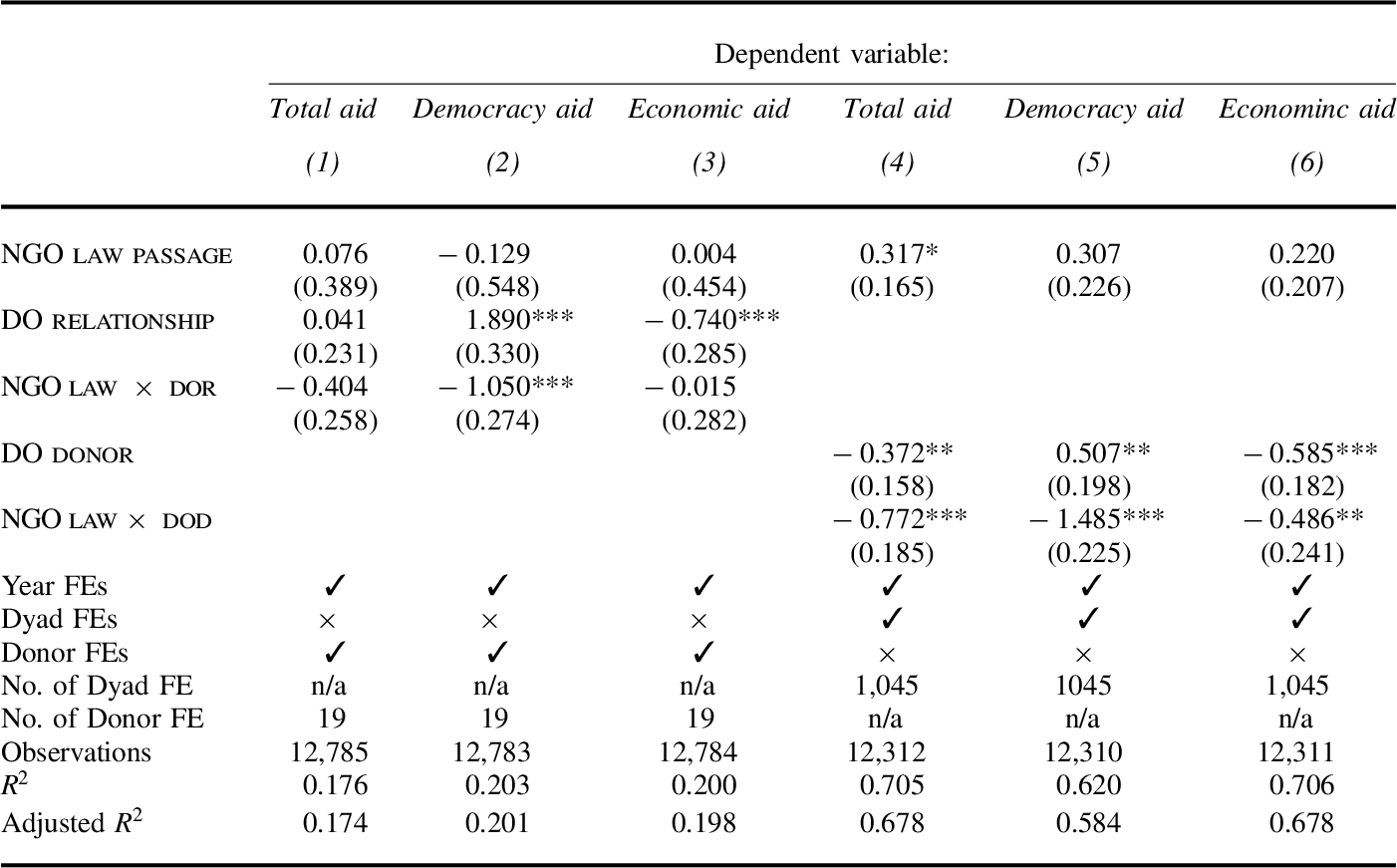

Next, we test whether donors’ past commitment to democracy promotion conditions the effect of NGO law passage on aid flows. Table 2 reports the marginal effect, as moderated by the democracy orientation of the donor–recipient relationship (models 1–3) and the donor overall (models 4–6). We find strong evidence that DO donors “back down” on their support for democracy activities in the face of administrative repression. The passage of an NGO law is associated with an enormous and statistically significant decrease in democracy spending among democracy-oriented donors across both dyad- and donor-level measures of democracy orientation. The results from models 2 and 5 suggest that the most democracy-oriented donors reduce their commitments to democracy projects by nearly 70 percent in the years after the passage of a restrictive NGO law.Footnote 83 To contextualize the size of the estimated effect, in the years prior to law passage, DO donors allocated USD 4,700,000 on average to democracy activities annually. A 70 percent decrease in democracy spending thus corresponds to an incredible reduction of USD 3,285,000 per year in democracy aid for the average dyad.

Table 2. Marginal effect of law passage, by democracy orientation

Notes: Robust standard errors clustered by recipient country. Due to the time-invariant nature of our measures of relationship orientation within dyads (DOR), we use donor FEs in models 1–3. Dependent variables are logged using a

![]() ${\rm{log}}\left( {y + 1} \right)$

transformation. *

${\rm{log}}\left( {y + 1} \right)$

transformation. *

![]() $p \lt .10$

; **

$p \lt .10$

; **

![]() $p \lt .05$

; ***

$p \lt .05$

; ***

![]() $p \lt .01$

$p \lt .01$

We find inconsistent evidence regarding the effect of restrictive laws on economic aid from DO donors. Model 3 suggests that NGO law passage has no effect on economic aid within DO dyads, while model 6 suggests a 23 percent reduction in economic aid among DO donors. Still, this suggests that DO donors are neither “taming” their aid by shifting funds from contentious democracy programs into more regime-compatible sectors,Footnote 84 nor punishing regimes by cutting economic assistance at the same rate as democracy assistance.

The finding that the passage of an NGO law corresponds to a large and statistically significant decrease in democracy aid among DO donors holds under a range of alternative measurement choices and model specifications, including the inclusion of never-treated dyads in a staggered difference-in-differences design; alternative operationalizations of democracy orientation; the inclusion of covariates, including lagged measures of civil society repression, human rights, and liberal democracy; alternative transformations of the outcome variables; and dropping the largest donor (the United States).Footnote 85 Results from these robustness tests are reported in Appendix F.

Taken together, these results provide strong support that in the face of increasing legal restrictions on NGOs, the most democracy-oriented donors “back down.” However, two-way fixed-effects models suffer from significant limitations that might reduce confidence in our findings. Fixed-effects models are vulnerable to bias in the presence of heterogeneous or dynamic treatment effects.Footnote 86 Event-study models can also overweight short-term and discount longer-term treatment effects.Footnote 87 Most importantly, fixed-effects models average across all post-treatment years, obscuring potential trends or reversions. To address these limitations and illuminate how treatment effects evolve over time, we complement our event-study analysis with GSC analysis.

We estimate GSC models on the full sample of donors, as well as two subsamples including only dyads with DO or non-DO donors, respectively (Figures 4 and 5). For all three samples, the pool of control units includes all never-treated dyads. To ensure a viable weighted control group, we exclude treated dyads with less than five pre-treatment periods.Footnote 88 Consistent with the results reported earlier, the passage of an NGO law is associated with no significant change in overall or democracy aid flows when averaging across all donors (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effect of law passage on aid flows: all donors

Figure 5. Effect of law passage on democracy aid, by donor orientation

Analyzing the effect of NGO law passage on donors who prioritize democracy, we again see clear evidence of a substantial, significant, and sustained decrease in democracy aid among DO donors. The average effect of law passage on treated DO dyads is –0.835 (

![]() $p = 0.013$

) in the first year following passage, equivalent to a 57 percent decrease in democracy aid flows (Figure 5a). By the fifth year after law passage, the effect of NGO law passage is estimated at –1.86 (

$p = 0.013$

) in the first year following passage, equivalent to a 57 percent decrease in democracy aid flows (Figure 5a). By the fifth year after law passage, the effect of NGO law passage is estimated at –1.86 (

![]() $p = 0.003$

), equivalent to an 84 percent decrease from pre-law democracy commitments. By contrast, we see very few sustained changes in democracy aid flows among non-DO donors (Figure 5b). Democracy aid briefly increases in the year after law passage, with an effect size of 0.526 (

$p = 0.003$

), equivalent to an 84 percent decrease from pre-law democracy commitments. By contrast, we see very few sustained changes in democracy aid flows among non-DO donors (Figure 5b). Democracy aid briefly increases in the year after law passage, with an effect size of 0.526 (

![]() $p = 0.007$

), but quickly returns to a null effect starting two years after law passage.

$p = 0.007$

), but quickly returns to a null effect starting two years after law passage.

On the other hand, we find no evidence of a significant change in economic aid flows among DO donors in each of the six years following law passage (see Figure A2 in Appendix G), suggesting that NGO laws are neither prompting DO donors to rechannel aid from democracy to economic sectors, nor prompting them to “punish” law-passing regimes by scaling back more regime-compatible economic aid.

Together, the results provide a clear picture of the aid environment following administrative crackdowns on NGOs. Rather than leveraging their networks and capacity to push back against shrinking civic space, the most democracy-oriented donors back away from democracy-promotion activities. But this effect is largely confined to the democracy sector, indicating that the donors most dedicated to democracy promotion scale back democracy assistance without sacrificing the flow of regime-compatible aid for services and infrastructure.

Discussion

We find strong evidence that DO donors respond to restrictive NGO laws by dramatically reducing their support for democracy-promotion projects. In this section, we consider two alternative explanations for our findings: (1) that donors are responding not to NGO laws specifically but to democratic backsliding and closing civic space in general; and (2) that the observed reductions in democracy aid reflect DO donors’ efforts to sanction law-passing regimes rather than a scaling back of support for NGOs in the democracy space. We then turn to two cases of NGO law passage—Ethiopia and Cambodia—to illustrate the different ways in which DO donors alter their patterns of aid provision following the implementation of restrictive laws.

Disentangling NGO Laws from Democratic Backsliding

Much of the literature exploring the proliferation of NGO laws identifies restrictive legislation as part of a regime’s general embrace of illiberal norms and policies,Footnote 89 raising the possibility that the observed reduction of democracy aid by DO donors is a response not to NGO laws specifically but to democratic backsliding or entrenching authoritarianism more broadly. To isolate the effect of NGO laws from the effect of assaults on democracy more broadly, we re-estimate our two-way fixed-effects models controlling for indicators of democratic backsliding. To capture the various ways backsliding regimes assault democratic norms, we include V-DEM’s Clean Elections index, Freedom of Expression and Alternative Sources of Information Index, and Harassment of Journalists measure in our models. Following Little and Meng’s call for objective measures of backsliding,Footnote 90 we also control for electoral competitiveness using the data on opposition-held legislative seats from the Database of Political InstitutionsFootnote 91 and assaults on media freedom using the data on the murder and imprisonment of journalists compiled by the Committee to Protect Journalists. We find that NGO laws decrease democracy aid flows from DO donors by a similar amount even after controlling for these indicators of democratic backsliding (Table A13 in Appendix H).

From Whom Is Democracy Aid Withdrawn?

Might the negative effect of NGO laws on democracy assistance be interpreted as donors’ attempts to punish law-passing regimes by decreasing aid to government institutions? Indeed, aid for the democracy sector does not flow solely to NGOs but also supports institution-strengthening activities within recipient governmentsFootnote 92 and activities implemented by other “bypass” actors.Footnote 93 To understand which actors bear the brunt of cuts to democracy aid, we disaggregate democracy aid commitments by delivery channel, estimating the effect of NGO laws on democracy aid channeled through international and local NGOs, recipient government institutions, donor government institutions, and other (non-NGO) bypass channels among both DO and non-DO donors.

Among DO donors, the passage of an NGO law results in a significant decrease in the amount of democracy aid channeled through NGOs and other bypass channels, as well as through donor government institutions (Figure A4 in Appendix I). By contrast, NGO laws have no effect on the amount of democracy aid channeled through recipient-country governments. These findings, while purely exploratory, suggest that it is civil society, and not regime institutions, that bears the brunt of donors’ reductions in democracy aid, providing additional support for the notion that NGO laws indeed “work” as regimes intend them to.

Case Illustrations

What does it look like when DO donors back down in the face of closing civic space? Our data suggest that, in most cases, donors find ways to deliver support for democracy-promotion activities to NGOs operating on the ground. In our sample, instances of DO donors eliminating all democracy support after an NGO law are relatively rare: of 271 DO donor-recipient dyads, only 31 dropped their democracy support to zero for the entire five-year period after the law.Footnote 94 In fact, Turkmenistan’s 2013 law, which implemented an elaborate registration process for all foreign aid, is the only case where every DO donor dropped democracy aid to zero. Descriptive analysis thus suggests that in all but the most severe cases, donors are still able to fund some democracy-promotion activities, even while NGO laws increase the difficulty of channeling those funds through local NGOs.

To better understand how donors navigate democracy promotion in the face of increasing restrictions, we turn to a brief analysis of two cases: Ethiopia and Cambodia. The two cases were chosen to probe donors’ responses to a highly restrictive law (Ethiopia) and a fairly average law (Cambodia). In both cases, the passage of NGO laws generated extensive media attention and vocal pushback from donors and civil society;Footnote 95 however, donors pursued different strategies—negotiation in Ethiopia and scaling back in Cambodia—to continue providing democracy assistance following law passage, with varying degrees of success. While far from an exhaustive characterization of donor response, together, these two cases help illustrate how committed donors attempt to push back in the face of closing civic space, while also underlining the critical role of the resolve of the recipient government in conditioning the effectiveness of such efforts.

We turn first to Ethiopia’s 2009 Charities and Societies Proclamation Act. Among the most restrictive NGO laws in our sample, the act prohibited NGOs receiving more than 10 percent of their funds from foreign sources from conducting work bearing on “internal politics.”Footnote 96 In diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks, US officials acknowledged that the law would “prohibit significant support to Ethiopian CSOs ... undercutting the potential to build local CSO capacity to sustain civil society’s watchdog role.”Footnote 97 Local NGOs that focused on human rights and democracy were decimated: only twelve or thirteen of the 125 existing NGOs successfully reregistered under the new regulatory framework.Footnote 98

The ostensible goal of these restrictions was to block international funding for democracy promotion, but our data suggest that only two of Ethiopia’s five DO donors decreased their democracy aid in the wake of the law. In practice, the Ethiopian government allowed donor countries to negotiate exemptions for their own programs and NGOs, meaning that the activities of international NGOs were only marginally affected.Footnote 99 Donors maintained (and even increased) their support for democracy-promotion activities by channeling funds through international NGOs while “cut[ting] support to local NGOs that continued to work in the restricted areas.”Footnote 100 For donors, the government’s willingness to negotiate exemptions signaled a desire to stifle local organizations but no resolve to suppress democracy-promotion activities altogether.Footnote 101

Cambodia’s 2015 Law on Associations and NGOs produced a much different outcome. Though it lacked explicit restrictions on NGOs’ ability to receive international funding, all five of Cambodia’s DO donors reduced funding for democracy programs by at least 50 percent after its passage, with two DO donors eliminating democracy aid completely. As the largest provider of democracy assistance before this law, Sweden’s response is particularly instructive. Sweden halved its average annual support for democracy promotion in the four years following the law’s passage. But despite this reduction, Sweden continued to provide substantial financial support to twelve prominent local human rights organizations through Diakonia, a Swedish international NGO. A 2018 report outlined the challenges faced by donors seeking to push back against closing civic space, noting that “Diakonia is expected to be both a brave member of an international coalition to counter attacks on human rights and democracy—and at the same time, minimize the risk of its country office, its staff and partners.”Footnote 102 Despite the donor’s desire to push back, reviewers concluded that Diakonia responded to the law by “taking a low profile to reduce risk for staff and possible de-registration (and even encouraged partners to do the same—which has not always been appreciated by partners who have chosen a more defiant role).”Footnote 103 The organization’s reluctance to fulfill its mandate as an “international democracy advocate” led some local partners to characterize Diakonia as “fearful.”Footnote 104

A review of Sweden’s human rights portfolio in Cambodia suggests that the new law, along with larger clampdowns on civil and political rights, rendered the donor’s strong ideological commitment to pushing back difficult to follow through on. In 2024, in a decision widely viewed as reflecting the difficulty of making real progress on democracy and human rights in Cambodia, Sweden ceased all bilateral cooperation with the country, including all democracy and economic assistance. The Ethiopian regime had signaled a willingness to negotiate continued democracy-promotion operations by donors and international NGOs, but the Cambodian government made no such concessions. Instead, a spokesperson dismissed widespread concern about Sweden’s withdrawal by claiming that “NGOs make bad reports about Cambodia to receive funding” and that the Swedish government understood “Cambodia doesn’t need the NGOs to continue working [on democracy] ... since the government has worked on that.”Footnote 105

Conclusion

As democracies across the developing world slide toward authoritarianism, it is important to assess what donors are doing to help defend the gains made under democracy’s third wave. Among the small group of donors most committed to democracy assistance, we find that administrative repression of civil society has succeeded in decimating aid to sectors such as human rights, advocacy, and elections, while aid for services and infrastructure that bolsters support for these backsliding regimes continues to flow. As a result, aspiring autocrats that use NGO laws to repress civil society are rewarded with a more regime-compatible composition of foreign aid flows.

Specifically, we find that the passage of a restrictive NGO law reduces democracy aid from DO donors by over 70 percent, and that this dramatic reduction persists for several years. The findings indicate that NGO laws are a powerful tool not only for suppressing the activities of local civil society organizations,Footnote 106 but also for altering the behavior of international actors who support democratic governance. Consistent with a large literature emphasizing the importance of donor self-interest in determining aid composition,Footnote 107 DO donors’ retreat suggests that even the donors most heavily invested in support for democracy and human rights are more strategic than ideological, with likely negative consequences for the efficacy of transnational advocacy efforts already hampered by government restrictions.Footnote 108

Nonetheless, democracy assistance rarely vanishes completely in the wake of restrictive legislation. As illustrated by the cases of Cambodia and Ethiopia, donors often prove capable of continuing some work with local and international NGOs to deliver democracy aid despite restrictions; however, in the face of high recipient-government resolve, donors’ options for continued engagement on human rights and advocacy might be especially limited. Recent work on successful efforts to block NGO law passage suggests that the decimation of democracy assistance need not be viewed as inevitable;Footnote 109 rather, future research should investigate in more detail the factors that enable donors to sustain support for democracy amid legal restrictions on civic space.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Vernon and the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law for sharing data, and Akash Chopra and Julie Snyder for excellent research assistance. We also thank Heather Huntington, Eddy Malesky, Jennifer Tobin, Kate Vyborny, Matthew Winters, participants at the APSA 2021 panel on Foreign Aid and NGOs in Developing Countries, participants in the DevLab@Duke 2021 workshop series, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this research note may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FIINC8>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this research note is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818325100957>.

Authors

Lucy Right is a Postdoctoral Associate with the Georg Walter Leitner Program in International and Comparative Political Economy at Yale University. She can be reached at lucille.right@yale.edu.

Jeremy Springman is a Research Assistant Professor at PDRI-DevLab at the University of Pennsylvania. He can be reached at jspr@sas.upenn.edu.

Erik Wibbels is the Presidential Penn Compact Professor of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania. He can be reached at ewibbels@sas.upenn.edu.