Background

Perinatal depression is a critical problem faced by mothers (O’Hara & McCabe, Reference O’Hara and McCabe2013), with the global prevalence of postpartum depression estimated at 17.7% (Hahn-Holbrook, Cornwell-Hinrichs, & Anaya, Reference Hahn-Holbrook, Cornwell-Hinrichs and Anaya2017). Perinatal depression has been linked to attempted suicide of mothers, paternal depression, and developmental delay of their offspring (Slomian, Honvo, Emonts, Reginster, & Bruyere, Reference Slomian, Honvo, Emonts, Reginster and Bruyere2019; Wang, Li, Qiu, & Xiao, Reference Wang, Li, Qiu and Xiao2021). To address these public health problems, researchers have identified potentially modifiable social factors (Zhao & Zhang, Reference Zhao and Zhang2020) and implemented several preventive efforts (Force et al., Reference Curry, Krist, Owens, Barry, Caughey, Davidson, Doubeni, Epling, Grossman, Kemper, Kubik, Landefeld, Mangione, Silverstein, Simon, Tseng and Wong2019; Yasuma et al., Reference Yasuma, Narita, Sasaki, Obikane, Sekiya, Inagawa and Nishi2020). However, women who need mental support are still not adequately treated because of barriers to healthcare access, including physical distance, lack of time, and high cost (Dennis & Chung-Lee, Reference Dennis and Chung-Lee2006; Fonseca, Gorayeb, & Canavarro, Reference Fonseca, Gorayeb and Canavarro2015; Kingston et al., Reference Kingston, Austin, Heaman, McDonald, Lasiuk, Sword and Biringer2015). Therefore, addressing barriers is essential for preventing perinatal depression.

Recently, mobile wireless technologies for public health—commonly referred to as ‘mHealth’ (World Health Organization, 2016)—have been increasingly implemented. For example, a large randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigated the effect of automated Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in preventing perinatal depression and revealed that it could be effective in women with mild psychological distress (Nishi et al., Reference Nishi, Imamura, Watanabe, Obikane, Sasaki, Yasuma and Kawakami2022). Similarly, our previous RCT revealed that providing mHealth consultation services in the early perinatal periods reduced the risk of elevated depressive symptoms at three months post-delivery to a relative risk of 0.67 (Arakawa et al., Reference Arakawa, Haseda, Inoue, Nishioka, Kino, Nishi and Kondo2023). Because perinatal depression often begins within four weeks after birth but can also occur during pregnancy (Tokumitsu et al., Reference Tokumitsu, Sugawara, Maruo, Suzuki, Shimoda and Yasui-Furukori2020; Wisner et al., Reference Wisner, Sit, McShea, Rizzo, Zoretich, Hughes and Hanusa2013), initiating mHealth interventions during pregnancy is reasonable.

Although the effectiveness of mHealth consultation services for preventing early-phase depressive symptoms has been demonstrated, its long-term effect remains unclear. Recent research indicates that some experience persistent depressive symptoms throughout the first year postpartum, some experience them only in the early postpartum period, and others only in the late postpartum periods (Kikuchi et al., Reference Kikuchi, Murakami, Obara, Ishikuro, Ueno, Noda and Tomita2021). Given that maternal postpartum depression is associated with adverse health outcomes in children, and that longer durations of depressive episodes exacerbate this association (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014), effective preventive interventions in the late postpartum period are crucial. However, research is scant on whether mHealth interventions in the early perinatal period can have long-term effects on preventing postpartum depression. Furthermore, no research has explored how patterns of postpartum depressive symptoms over the first year after birth are affected by mHealth intervention using a randomized design. Moreover, the mechanism by which mHealth intervention prevents postpartum depressive symptoms is still unclear, despite previous studies indicating the importance of social factors, such as loneliness, on maternal mental health (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, Reference Cacioppo, Hawkley and Thisted2010; Dennis & Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2013; Harrison, Moulds, & Jones, Reference Harrison, Moulds and Jones2022).

To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a follow-up study of our previous RCT. We hypothesized that (H1) preventive mHealth consultation during the early perinatal period may have long-term effects and influence the transition patterns of depressive symptoms during the first year after birth, and (H2) reductions in loneliness resulting from the intervention may mediate its effects on maternal mental health.

To test these hypotheses, we examined: (1) the risk of elevated depressive symptoms at 12 months postpartum, (2) group differences in the transition patterns of postpartum depressive symptoms over the first year, and (3) the mediating role of loneliness at three months postpartum in the association between the intervention and depressive symptoms at 12 months postpartum.

Methods

Trial design and participants of the original RCT

Our original RCT was conducted in Yokohama, an urban city and one of the most populous municipalities in Japan. Yokohama City provides conventional free face-to-face perinatal care services to all mothers in ordinary situations; however, some were restricted during the COVID-19 era. The previous study enrolled pregnant women who lived in Yokohama City from September 1, 2020, to March 7, 2021. Our inclusion criteria were (1) self-reported pregnancy (expected delivery date by October 31, 2021), (2) living in Yokohama City, and (3) able to communicate in Japanese. We recruited women who visited public ward offices to register their pregnancy status or who attended mothers’ preparation classes, regardless of trimester. We also recruited pregnant women through announcements on an official website and distributed leaflets at public facilities supporting childcare and local clinics. The details of the recruitment process have previously been described (Arakawa et al., Reference Arakawa, Haseda, Inoue, Nishioka, Kino, Nishi and Kondo2023). There were no exclusion criteria since a recent review highlighted the importance of universal preventive strategies (Yasuma et al., Reference Yasuma, Narita, Sasaki, Obikane, Sekiya, Inagawa and Nishi2020). All women who accessed our study website and agreed to participate in the study provided their informed consent with baseline data on the website. Participants were immediately randomized to either the mHealth or usual care group, using 1:1 algorithmic randomization. After group allocation, the participants were sent an online questionnaire via e-mail to collect additional baseline data. In the original trial, we followed the participants and sent an online questionnaire to evaluate their depressive symptoms up to three months post-delivery. The primary outcome of the original study was depressive symptoms at three months postpartum.

Follow-up study design and participants

This study was a follow-up study of the original RCT. Participants who were randomized to either group in the original RCT were asked at the study’s conclusion whether they would be interested in participating in additional survey-based follow-up research. Those who said yes were included in the current follow-up study and provided a survey 12 months postpartum. We analyzed data collected via an online questionnaire with Google Forms 12 months postpartum, as well as data collected in the original RCT through a research website and online questionnaires. All participants received 1,000 JPY (approximately 7 USD) in online vouchers when they completed the questionnaire 12 months post-delivery.

Intervention

The intervention was an mHealth consultation service offered by a private company, Kids Public, Inc. In the previous study, the City of Yokohama and Kids Public, Inc. were contracted to offer mHealth consultation services to the mHealth group, from assignment to four months post-delivery. This service was provided through the LINE platform, Japan’s most popular social media application for messaging and calling (reaching approximately 95% of women of childbearing age; Institute for Information and Communication Policy, 2021). Women in the mHealth group could freely consult with health professionals using their mobile devices, with no limit on the number of consultations. The consultants comprised obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians, and midwives with more than three years of experience in maternity or childcare. The doctors and midwives offered general advice and emotional support regarding pregnancy and childcare, without making diagnoses or prescriptions. Women in the mHealth group could reserve available 10-minute sessions and select their preferred consultants and communication tool (voice call, text messaging/chat, or video calls) between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m., Monday through Friday. After delivery, they could also use chat consultations with midwives without time restrictions, from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Users were regularly sent online articles with helpful information on maternity and childcare, encouraging women to use the service if they needed help.

Women assigned to the usual care group were not offered mHealth services. Instead, they were offered access to a website developed by a research team, where they could easily obtain useful information related to maternity and childcare provided by the City of Yokohama or other institutions, such as national public hospitals. From April 28, 2022, in response to the results of the previous study, some perinatal women in Yokohama City (living in Kohoku Ward) were offered the opportunity to use the mHealth service regardless of their group assignment.

Outcome

Our primary outcome was the risk of elevated postpartum depressive symptoms 12 months after delivery. We used the Japanese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987; Okano, Reference Okano1996), a 10-item structured questionnaire used to screen for perinatal depression worldwide (O’Connor, Rossom, Henninger, Groom, & Burda, Reference O’Connor, Rossom, Henninger, Groom and Burda2016), to assess the primary outcome. Each item was scored from 0 to 3, with total scores ranging from 0 to 30. Higher scores on the EPDS indicate increased depressive symptoms. We defined a score of ≥9 as elevated postpartum depressive symptoms, based on the validation study (Okano, Reference Okano1996). We also used EPDS scores as continuous variables. In Japan, the EPDS is also used to screen for depressive symptoms during pregnancy, with a cut-off score of ≥13 reported in another validation study (Usuda, Nishi, Okazaki, Makino, & Sano, Reference Usuda, Nishi, Okazaki, Makino and Sano2017).

Based on a recent study examining the transition patterns of depressive symptoms (Kikuchi et al., Reference Kikuchi, Murakami, Obara, Ishikuro, Ueno, Noda and Tomita2021), we categorized participants into four patterns by their depressive symptoms at three months post-delivery in the original study and at 12 months post-delivery in the current follow-up study: (1) resilient, women with no depressive symptoms at both time points; (2) recovered, those with depressive symptoms at three months but not at 12 months; (3) late-onset, those without depressive symptoms at three months but with symptoms at 12 months; and (4) persistent, those with depressive symptoms at both three and 12 months.

Potential mediator variable

To uncover the mechanism by which the mHealth intervention decreases postpartum depressive symptoms, we selected loneliness at three months post-delivery in the original study as a potential mediator. A Cochrane review conducted in 2013 indicated loneliness as a potential target to prevent postpartum depression (Dennis & Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2013), and participants assigned to the mHealth group in our previous study had lower loneliness at three months post-delivery. We assessed loneliness using the Japanese version of the University of California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale, version 3 (Arimoto & Tadaka, Reference Arimoto and Tadaka2019). It is a three-item scale, with each item rated on a four-point scale: (1) never, (2) rarely, (3) sometimes, and (4) always. The total score ranges from 4 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater levels of loneliness. Loneliness was assessed at baseline and three months postpartum in the previous study, and 12 months postpartum in the current study.

Covariates

Participants’ sociodemographic data included age, parity (primipara or multipara), marital status (married or unmarried), household number, trimester of participation (first, second, and third trimester), household income, and educational attainment level. Since no women under 20 participated, we categorized participants’ ages into 20–29, 30–34, and 35 years and over, considering their age distribution. Equivalent household income was calculated and categorized into low (<4.5 million yen), intermediate (≥4.5 and ≤ 6.5 million yen), or high (>6.5 million yen) using tertile. Educational attainment was categorized into <16 years (under university) or ≥ 16 years (university or higher). In the baseline questionnaire, participants were asked whether they had a history of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder. Those who reported any of these conditions were categorized as having past mental health problems. Additionally, we included EPDS and loneliness scores at baseline as covariates.

Statistical analysis

First, as our study participants were randomized, we compared the primary outcome according to the intention-to-treat principle. We performed Fisher’s exact tests for the primary outcome and t-tests for the EPDS score and the UCLA loneliness scale to compare the outcomes between the groups at 12 months after childbirth, using complete case analyses. We applied modified Poisson regression analysis for the primary outcome (Zou, Reference Zou2004) and multiple linear regression analyses for the EPDS score and the UCLA loneliness scales to obtain risk ratios and risk differences and to estimate 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We also compared the primary outcome with baseline adjustment. We described mHealth use during pregnancy, the first month, and after two months postpartum, along with consultation frequency across these periods, and compared depressive symptoms at 12 months postpartum by consultation frequency. Further, we used all cases with multiple imputations for missing variables as a sensitivity analysis of the main analysis. Because the missing covariates and outcomes displayed a monotone pattern, we applied a sequence of independent univariate conditional imputation methods. Baseline variables used to impute missing baseline covariates and EPDS scores at three and 12 months post-delivery included age, parity, household size, random assignment of intervention, and calculated days between the participation and expected delivery day. We generated 10 simulated data which were combined with Rubin’s rule, obtaining the estimated treatment effect and 95% CIs.

Second, to explore how patterns of postpartum depressive symptoms up to one year differed between the two groups, we described and compared the number of participants categorized in each pattern (resilient, recovered, late-onset, and persistent) by mHealth and usual care groups. Since our previous study revealed the short-term effectiveness of the mHealth intervention, it could also influence the distribution of these depressive symptom patterns for up to one year. As a sensitivity analysis, we also ran a multinomial logistic regression model to adjust for baseline covariates.

Third, we conducted a mediation analysis to evaluate whether alleviating loneliness at three months post-delivery mediated the intervention effect on the risk of elevated depressive symptoms at 12 months post-delivery. A directed acyclic graph of our mediation model is illustrated in Supplementary Figure S1. We fitted a linear regression model for the mediator and a modified Poisson regression model for the outcome. Although our intervention was randomly assigned, there were mediator-outcome confounders between loneliness at three months post-delivery and depressive symptoms at 12 months post-delivery. Therefore, we included the covariates mentioned above in our mediation model. The EPDS and UCLA Loneliness Scale scores at participation were included as continuous variables. From this model, we estimated the total effect (from the intervention to the risk of elevated depressive symptoms at 12 months post-delivery), direct effect, and indirect effect (mediated through loneliness at three months post-delivery). We calculated the proportion mediated by dividing the coefficient of the indirect effect by that of the total effect. As a sensitivity analysis of the mediation model, we additionally included the EPDS score at three months post-delivery as a covariate, assuming that depressive symptoms preceded loneliness during this early phase. All analyses were conducted using the Stata software version 16 (StataCorp). The command ‘paramed’ was used to perform mediation analysis. The 95% CIs were obtained from 1,000 bootstrapped samples.

Project information

A previous randomized trial was executed under a contract between the City of Yokohama, Kids Public, Inc., the University of Tokyo, and other stakeholders; however, our research team conducted this follow-up study independently. The researchers were solely responsible for questionnaire construction, outcome data collection, analyses, and manuscript preparation. The study protocol was approved by the ethical review board of the University of Tokyo (No. 2019347NI).

Results

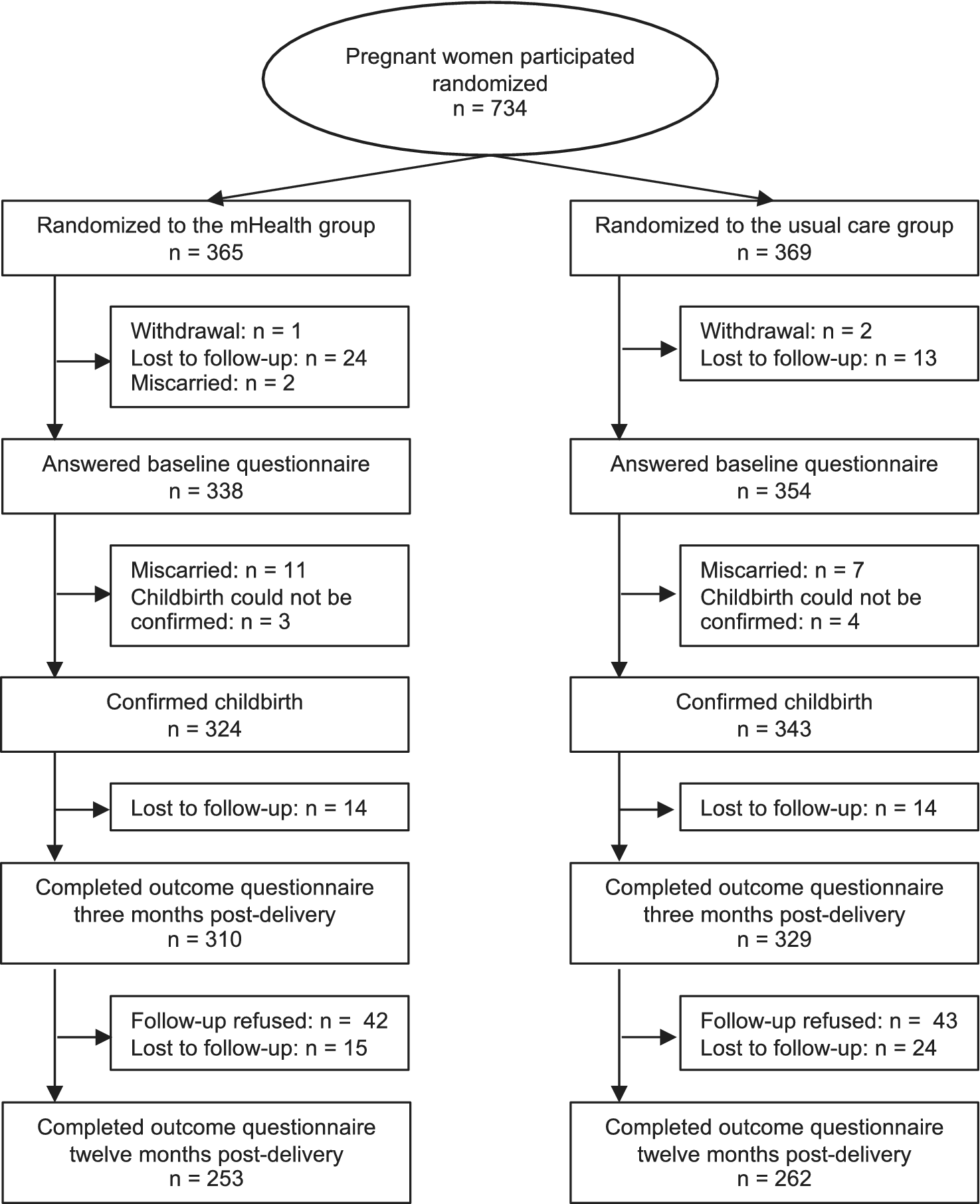

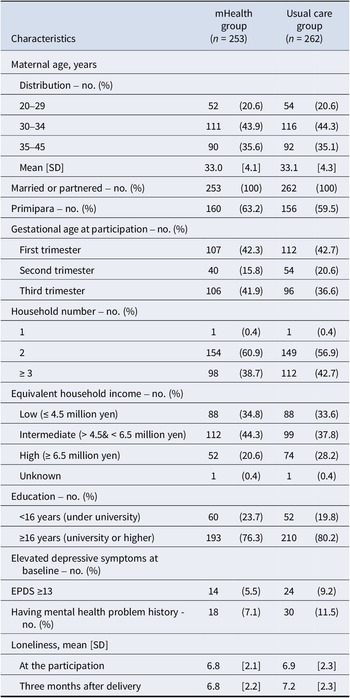

Among 734 women allocated to the mHealth (n = 365) or usual care (n = 369) groups in a previous study, 310 and 329 women completed the three months post-delivery questionnaires in the mHealth and usual care groups, respectively. Of these, 42 and 43 women refused to participate in the current study, respectively. Therefore, we followed 268 and 286 women in the mHealth group and usual care group (554 women; 75.5% of the original participants) up to 12 months post-delivery, with 15 and 24 lost to follow-up, respectively. Consequently, 253 women in the mHealth group and 262 women in the usual care group completed the outcome assessment 12 months after delivery in the current study (515 women; 70.2% of the original participants, Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of participants who completed all questionnaires were similar between the mHealth and usual care groups (Table 1). At baseline, 5.5% of the mHealth group and 9.2% of the usual care group exhibited elevated depressive symptoms, as indicated by the EPDS score of ≥13. Loneliness levels were also comparable between the two groups at baseline.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the study participants.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study participants who completed the 12-month post-delivery questionnaire (n = 515)

Note: EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SD, standard deviation.

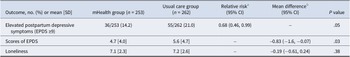

Compared to women in the usual care group, women in the mHealth group had a lower risk of experiencing elevated postpartum depressive symptoms at 12 months post-delivery (36 of 253 women [14.2%] vs. 55 of 262 women [21.0%]; relative risk, 0.68 [95% CI, 0.46, 0.99]; Table 2). The mean EPDS score at 12 months post-delivery was also lower in the mHealth group than in the usual care group (4.7 vs. 5.6, mean difference: -0.83 [95% CI, −1.60 to −0.07]). We found no difference in loneliness levels at 12 months post-delivery between the two groups (7.1 vs. 7.2, mean difference: -0.19 [95% CI, −0.61 to +0.24]). When adjusting for baseline covariates, the results were qualitatively consistent with the main analysis, although the 95% CI included the null (relative risk, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.49, 1.05]). About half of the women used mHealth during pregnancy, in the first month postpartum, and after two months postpartum, with most having zero to two consultations (Supplementary Table S1, Figure S2). No differences in depressive symptoms at 12 months postpartum were observed across consultation frequency categories (Supplementary Table S2). Our sensitivity analysis of the main analysis, imputing all missing variables, also showed a similar direction of the intervention effect with the main analysis; however, the 95% CIs of the sensitivity analysis included null (relative risk, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.51, 1.00]).

Table 2. Postpartum depressive symptoms, score of EPDS, and loneliness at 12 months post-delivery between the mHealth and usual care group

Note: CI, confidence interval; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SD, standard deviation.

a Relative risks were calculated using modified Poisson regression models.

b Mean differences were calculated using linear regression models.

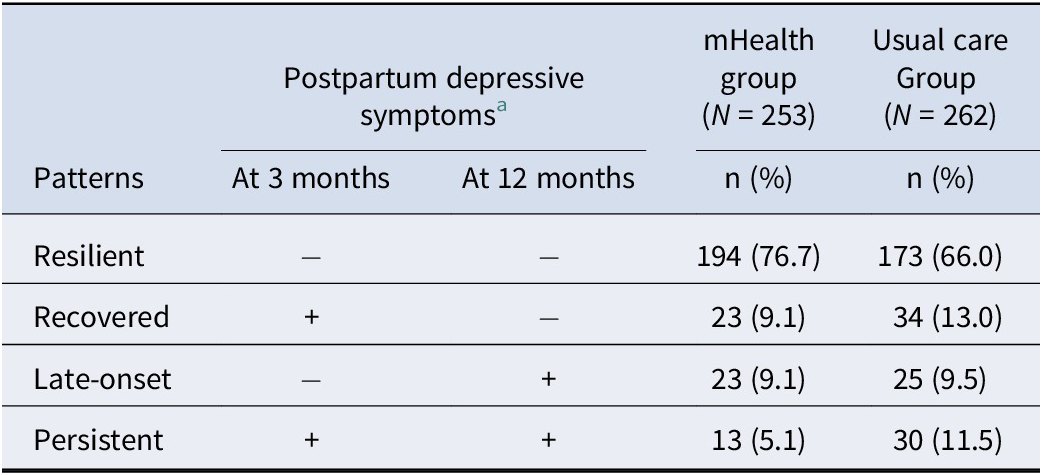

From the assessment of the transition patterns of depressive symptoms, of the 253 women in the mHealth group and 262 in the usual care group, 194 (76.7%) and 173 (66.0%) were classified as resilient, 23 (9.1%) and 34 (13.0%) as recovered, 23 (9.1%) and 25 (9.5%) as late-onset, and 13 (5.1%) and 30 (11.5%) as persistent, respectively (Table 3). Compared to the women in the usual care group, more women in the mHealth group were classified as resilient in the postpartum period. The proportions of women categorized in the recovered and persistent pattern were lower in the mHealth group, and the difference was evident in the persistent one. In contrast, we found no apparent difference in the proportion categorized in the late-onset depressive symptom pattern between the two groups. When adjusted for baseline covariates, the proportion categorized as the persistent pattern was lower in the mHealth group than in the usual care group (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 3. Differences in the transition patterns of postpartum depressive symptoms between the mHealth and usual care groups

a Postpartum depressive symptoms were defined as present with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scored nine or higher.

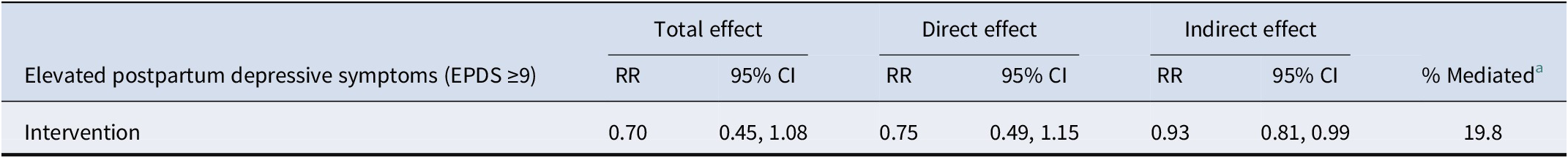

In the mediation analysis, the total effect was estimated to be 0.70 [95% CI, 0.45, 1.08] and the indirect effect (mediated through loneliness at three months post-delivery) was 0.93 [95% CI, 0.81. 0.99] (Table 4). The proportion mediated by reducing loneliness was estimated to be 19.8%. Our sensitivity analysis of the mediation model with adjustment for the EPDS score at three months post-delivery showed consistent direction; however, the proportion mediated was approximately halved (total effect, 0.75 [95% CI, 0.44, 1.16]; indirect effect, 0.97 [95% CI, 0.87, 1.01]; proportion mediated, 10.9%).

Table 4. Direct and indirect (through loneliness) effects of mHealth consultation services on the risk of elevated postpartum depressive symptoms (EPDS ≥9)

Note: CI, confidence interval; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The outcome model was modified Poisson regression with baseline adjustment. The mediation model was a linear regression with baseline adjustment. The adjustment variables were age, parity, trimester, household number, income, education, depressive symptoms at participation, loneliness at participation, and history of mental health problems.

a We calculated the proportion of the total effect that was mediated through loneliness at three months post-delivery by dividing the coefficient of indirect effect by that of total effect.

Discussion

Compared to the usual care group, the mHealth group had a lower risk of elevated postpartum depressive symptoms by one-third at 12 months post-delivery, despite our intervention being provided only from participation to four months post-delivery. Although the original study was randomized, the mHealth group had fewer participants with depressive symptoms at baseline in this follow-up due to attrition. However, the results were qualitatively consistent after adjusting for baseline covariates. When exploring differences in the transition patterns of depressive symptoms during the first year postpartum between the two groups, we found that the proportions of the recovered and persistent patterns were lower in the mHealth group. Our mediation analysis estimated that the effect of mHealth consultation services on the risk of elevated depressive symptoms at 12 months post-delivery was 10–20% mediated by reducing loneliness at three months post-delivery.

Our follow-up study suggests that early perinatal mHealth intervention may help alleviate postpartum depressive symptoms during the first year after delivery. Studies indicated some women suffer from their depressive symptoms in the late phase of postpartum (Chow et al., Reference Chow, Dharma, Chen, Mandhane, Turvey, Elliott and Kozyrskyj2019; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Sit, Yang, Ciolino, Gollan and Wisner2019; Putnick et al., Reference Putnick, Sundaram, Bell, Ghassabian, Goldstein, Robinson and Yeung2020), requiring effective interventions to reduce these burdens; however, most of the RCTs of perinatal mHealth interventions did not explore their impact on late-phase symptoms. For example, a recent review of digital interventions for preventing postpartum depression included 14 studies; of these, only two assessed outcomes at six months postpartum, and only one assessed outcomes at one year postpartum (Lewkowitz et al., Reference Lewkowitz, Whelan, Ayala, Hardi, Stoll, Battle and Miller2024). Similarly, a study reviewing app-based interventions included 16 studies, of which only one assessed the outcomes at one year postpartum (Miura et al., Reference Miura, Ogawa, Shibata, Kamijo, Joko and Aoki2023). In addition, the two studies that assessed symptoms at one year found no clear effects, suggesting limited evidence for the long-term effectiveness of mHealth interventions. Our study suggests that early perinatal mHealth support may help prevent the worsening of depressive symptoms in the later postpartum period. Several mechanisms may explain the long-term effects of early perinatal mHealth consultation services on depressive symptoms. Women in the mHealth group may have obtained general skills and knowledge about childcare, such as breastfeeding and child development, as well as individualized informational and emotional support, which could help them deal with issues in the later postpartum periods. From the perspective of the transactional model of stress and coping (Folkman, Lazarus, Gruen, & DeLongis, Reference Folkman, Lazarus, Gruen and DeLongis1986), overcoming problems in the early perinatal period with professional support can enhance coping abilities in managing childcare issues. This, in turn, may contribute to preventing depressive symptom elevation during later postpartum periods. Help-seeking experience is another factor that may explain our findings. Several studies have emphasized that perinatal women do not know that their feelings are not normal or how to deal with them (Goodman, Reference Goodman2009; Kingston et al., Reference Kingston, Austin, Heaman, McDonald, Lasiuk, Sword and Biringer2015). mHealth consultation services could reduce access barriers to seeking help and consultation on their feelings, which would lead to their recognition that it is better to seek help early. During the COVID-19 era, new private and public consultation services emerged, including one launched by Yokohama City in the later phase of this follow-up study. Women in the mHealth group may have increased their help-seeking behaviors through these services, based on positive early perinatal experiences. These mechanisms could have been achieved by the features of the mHealth consultation service, especially its timeliness and appropriateness through individualized support (Sakamoto et al., Reference Sakamoto, Carandang, Kharel, Shibanuma, Yarotskaya and Basargina2022).

Our exploratory analysis suggested that the mHealth service may help alleviate early-phase and persistent depressive symptoms. A previous Japanese study reported that some women experience depressive symptoms in the early postpartum period and recover naturally (recovered pattern; Kikuchi et al., Reference Kikuchi, Murakami, Obara, Ishikuro, Ueno, Noda and Tomita2021). The lower proportion of this pattern in our study suggests that the mHealth intervention may have prevented an elevation in depressive symptoms during the early perinatal period and maintained lower levels over one year, thereby reducing the number of women who would otherwise have been categorized as recovered without mHealth. The study also identified predictive factors for persistent depressive symptom patterns, such as higher psychological distress in early pregnancy. Our intervention, providing informational and emotional support during pregnancy, may have reduced psychological distress and, in turn, prevented persistent depressive symptoms. As a result, the mHealth intervention may have shifted women from the recovered and persistent patterns to the resilient ones. Early-phase and persistent depressive symptoms can affect offspring development (Tainaka et al., Reference Tainaka, Takahashi, Nishimura, Okumura, Harada, Iwabuchi and Tsuchiya2022). Delivering mHealth services in the early perinatal period may benefit both perinatal women and their offspring by minimizing prolonged exposure to maternal depressive symptoms throughout postpartum, which, in turn, may have a social impact from the life course perspective. In contrast, we did not find clear group differences in the late-onset pattern. Women may face challenges unique to the later postpartum period, such as child mobility or exhaustion after returning to work (Chow et al., Reference Chow, Dharma, Chen, Mandhane, Turvey, Elliott and Kozyrskyj2019). Further studies are needed to clarify specific factors related to late-onset depressive symptoms.

Our mediation analysis suggests that alleviating loneliness can be important for preventing perinatal depression. Several studies revealed that loneliness can predict depression (Adlington et al., Reference Adlington, Vasquez, Pearce, Wilson, Nowland, Taylor and Johnson2023; Kruse, Williams, & Seng, Reference Kruse, Williams and Seng2014). A review of preventive interventions for postpartum depression suggested the importance of reducing loneliness (Dennis & Chung-Lee, Reference Dennis and Chung-Lee2006), however, whether alleviating loneliness contributes to preventing postpartum depression was not empirically proven by an RCT. Our finding of the mediating effect of loneliness indicates that constructing a meaningful social connection may be important in preventing postpartum depression. Our intervention facilitated relationships and interactions with healthcare providers through mHealth, which could not be achieved through a completely automated program. Some studies indicate that human interaction in mHealth is beneficial in improving retention rates and outcomes (Mohr, Cuijpers, & Lehman, Reference Mohr, Cuijpers and Lehman2011; Silang et al., Reference Silang, Sohal, Bright, Leason, Roos, Lebel and Tomfohr-Madsen2022; Torous, Lipschitz, Ng, & Firth, Reference Torous, Lipschitz, Ng and Firth2020), which may be partly explained by a feeling of connectedness and reduced loneliness (Sakamoto et al., Reference Sakamoto, Carandang, Kharel, Shibanuma, Yarotskaya and Basargina2022). However, the mediated proportion was less than 20%, suggesting that other factors may play a substantial role in producing the preventative effect. Changes in coping style—such as an increase in help-seeking behavior—are considered potential mediators, as such changes, once established, are likely to persist over time. We must continue seeking other factors that contribute to preventing depressive symptoms to achieve effective and replicable mHealth interventions.

This study has several limitations. First, the attrition rate of 30% may introduce bias to the results. Some participants with depressive symptoms during the postpartum period might refuse to be followed up or drop out because they could not use the mHealth consultation services in the follow-up periods, which might yield overestimation. Despite the RCT design, baseline differences in depressive symptoms due to attrition should also be considered when interpreting the findings. Second, due to the lack of time-ordering between loneliness and depressive symptoms at three months, we cannot rule out the possibility that depressive symptoms at three months confounded the mediator-outcome association. However, we found similar results in our sensitivity analysis of mediation adjusting for EPDS score at three months post-delivery, indicating that alleviating loneliness played, to some extent, a necessary role in the effect of mHealth on long-term postpartum depression. Third, some unmeasured confounders between the mediator and outcome, such as children’s temperament or work environment, may yield confounding bias. Fourth, although the EPDS is the most reliable patient-reported screening measure for postpartum depression and a well-validated scale for diagnostic interviews for perinatal depression worldwide (Levis et al., Reference Levis, Negeri, Sun, Benedetti, Thombs and Group2020; Sultan et al., Reference Sultan, Ando, Elkhateb, George, Lim, Carvalho and O’Carroll2022), we did not utilize a formal clinical diagnosis of postpartum depression as the primary outcome. Fifth, the consultation service launched by Yokohama City in the later phase of this follow-up study may have influenced depressive symptoms, as women in the usual care group also had access, though for a limited duration and proportion. Sixth, we included only women who could communicate in Japanese, so our findings cannot be extended to those with language barriers in Japan. Finally, all study participants had partners and most had high incomes and levels of education. In addition, this study was conducted during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, when face-to-face contact was partially restricted. These circumstances may limit the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusions

In this follow-up study of RCT, we found that mHealth services may have a long-term effect in alleviating elevated postpartum depressive symptoms one year after delivery. Our findings suggest that providing mHealth consultation services focused on the early perinatal period may positively impact perinatal women’s mental health related to their offspring’s developmental delay. Interventions aimed at alleviating loneliness may contribute to the development of more effective mHealth strategies for preventing postpartum depression. Incorporating our findings into future mHealth prevention programs and evaluating their broader public health impact are warranted.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291725102596.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants of our study. We are grateful to the staff from the City of Yokohama for their assistance. We further appreciate Naoya Hashimoto and Daisuke Shigemi from Kids Public, Inc., for their valuable discussions on how to implement this study in a real-world setting. Additionally, we would like to thank Hanae Nagata, Kaori Sumino, Keiko Ueno, Minami Koda, Saki Nakamura, and Hisako Ogasawara, for valuable support to improve our questionnaires. We also would like to acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI) for assistance in improving the clarity and readability of the English language.

Funding statement

This study was funded by The Health Care Science Institute Research Grant in 2021. The previous randomized trial was funded by the City of Yokohama. Kids Public, Inc. offered the mHealth consultation service funded by the City of Yokohama.

Competing interests

DN received personal fees outside the submitted work from MD.net, and an honorarium from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. and Otsuka Medical Devices Co., Ltd.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.