A properly convex domain is a convex open set in real-projective space whose closure contains no projective line. The quotient of such a domain by a discrete torsion-free group of projective transformations that preserve the domain is a properly convex manifold. If, in addition, the frontier of the domain contains no segment of a projective line bigger than one point, then the manifold is strictly convex. A hyperbolic manifold is a strictly convex projective manifold.

The case of dimension

![]() $2$

had been much studied. This is the simplest case of higher Teichmüller theory. A basic result is that a strictly convex structure on a closed manifold is uniquely determined by the conjugacy class of the holonomy homomorphism into the projective general linear group. Moreover, if the dimension of the manifold is at least

$2$

had been much studied. This is the simplest case of higher Teichmüller theory. A basic result is that a strictly convex structure on a closed manifold is uniquely determined by the conjugacy class of the holonomy homomorphism into the projective general linear group. Moreover, if the dimension of the manifold is at least

![]() $2$

, then the holonomies that arise are precisely those in certain topological components of the representation variety. The goal of this paper is to provide self-contained proofs of these results.

$2$

, then the holonomies that arise are precisely those in certain topological components of the representation variety. The goal of this paper is to provide self-contained proofs of these results.

If

![]() $G$

is a Lie group, and

$G$

is a Lie group, and

![]() $X$

is a manifold on which

$X$

is a manifold on which

![]() $G$

acts analytically and transitively, then a

$G$

acts analytically and transitively, then a

![]() $(G,X)$

-structure on a manifold is a maximal collection of charts which take values in

$(G,X)$

-structure on a manifold is a maximal collection of charts which take values in

![]() $X$

and such that the transition functions are in

$X$

and such that the transition functions are in

![]() $G$

. For such structures, the Ehresmann–Thurston principle says that when

$G$

. For such structures, the Ehresmann–Thurston principle says that when

![]() $M$

is closed (compact without boundary), then the set of holonomies of

$M$

is closed (compact without boundary), then the set of holonomies of

![]() $(G,X)$

-structures is an open subset of the representation variety. However, properly convex structures do not fit into this scheme. The basic issue is that the convex open set in projective space varies. The set of such holonomies is often not closed. For example, the space of hyperbolic structures on the circle is not closed in

$(G,X)$

-structures is an open subset of the representation variety. However, properly convex structures do not fit into this scheme. The basic issue is that the convex open set in projective space varies. The set of such holonomies is often not closed. For example, the space of hyperbolic structures on the circle is not closed in

![]() $\textrm {PO}(1,1)$

. In general, the space of all projective structures on a manifold of dimension larger than

$\textrm {PO}(1,1)$

. In general, the space of all projective structures on a manifold of dimension larger than

![]() $2$

is mysterious.

$2$

is mysterious.

If

![]() $M$

is a compact

$M$

is a compact

![]() $n$

-manifold, then

$n$

-manifold, then

![]() $\textrm {Rep}(M)={\textrm {Hom}}(\pi _1M,\textrm {PGL}(n+1,{\mathbb{R}}))$

is a real algebraic variety. Let

$\textrm {Rep}(M)={\textrm {Hom}}(\pi _1M,\textrm {PGL}(n+1,{\mathbb{R}}))$

is a real algebraic variety. Let

![]() $\textrm {Rep}_{P}(M)$

and

$\textrm {Rep}_{P}(M)$

and

![]() $\textrm {Rep}_{S}(M)$

be, respectively, the subsets of

$\textrm {Rep}_{S}(M)$

be, respectively, the subsets of

![]() $\textrm {Rep}(M)$

of holonomies of properly convex, and of strictly convex structures on

$\textrm {Rep}(M)$

of holonomies of properly convex, and of strictly convex structures on

![]() $M$

. Then

$M$

. Then

![]() $\textrm {Rep}_S(M)\subseteq \textrm {Rep}_P(M)$

. Throughout this paper we use the Euclidean topology everywhere, and not the Zariski topology. In the following,

$\textrm {Rep}_S(M)\subseteq \textrm {Rep}_P(M)$

. Throughout this paper we use the Euclidean topology everywhere, and not the Zariski topology. In the following,

![]() $M$

is closed and

$M$

is closed and

![]() $n\geqslant 2$

.

$n\geqslant 2$

.

1. Open Theorem.

![]() $\textrm {Rep}_{P}(M)$

is open in

$\textrm {Rep}_{P}(M)$

is open in

![]() $\textrm {Rep}(M)$

.

$\textrm {Rep}(M)$

.

2. Closed Theorem.

![]() $\textrm {Rep}_{S}(M)$

is closed in

$\textrm {Rep}_{S}(M)$

is closed in

![]() $\textrm {Rep}(M)$

.

$\textrm {Rep}(M)$

.

3. Clopen Theorem. Then

![]() $\textrm {Rep}_S(M)$

is a union of connected components of

$\textrm {Rep}_S(M)$

is a union of connected components of

![]() $\textrm {Rep}(M)$

.

$\textrm {Rep}(M)$

.

It follows from (1.15) that the holonomy of a strictly convex structure uniquely determines a projective manifold up to projective isomorphism. The Open Theorem is due to Koszul [Reference KoszulKos65, Reference KoszulKos68]. Our proof is distilled from his. There is an affine manifold that is the tautological line bundle over a projective manifold,

![]() $M$

. Then

$M$

. Then

![]() $M$

is properly convex if and only if there is an outwards-convex section of this bundle such that every connected flat subset of the section is contained in a simplex. This type of convexity is easily shown to be preserved by small deformations.

$M$

is properly convex if and only if there is an outwards-convex section of this bundle such that every connected flat subset of the section is contained in a simplex. This type of convexity is easily shown to be preserved by small deformations.

The Closed Theorem when

![]() $n=2$

is due to Choi and Goldman [Reference Choi and GoldmanCG93, Reference Choi and GoldmanCG05], to Kim [Reference KimKim01] when

$n=2$

is due to Choi and Goldman [Reference Choi and GoldmanCG93, Reference Choi and GoldmanCG05], to Kim [Reference KimKim01] when

![]() $n=3$

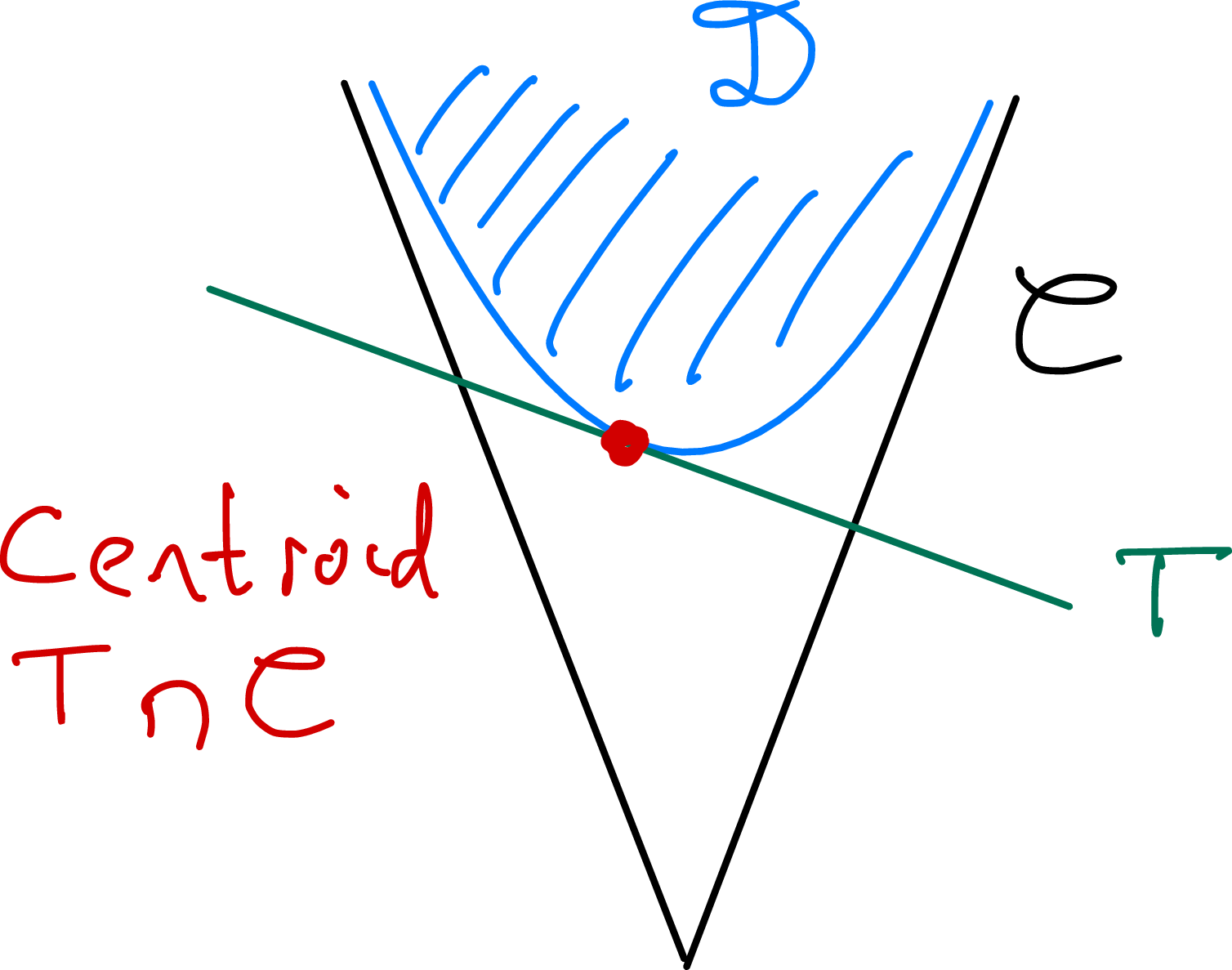

and to Benoist [Reference BenoistBen05] in general. Our proof is new, and based on a geometric argument called the box estimate (4.3). Given a sequence of strictly convex projective structures whose holonomies converge, the associated domains might degenerate. Benzécri’s compactness theorem [Reference BenzécriBen60] implies one may apply projective transformations so that the domains converge to a properly convex domain, but then the holonomies might diverge. The box estimate implies that if one chooses the conjugacies carefully, then the holonomies also converge. This involves an elementary geometric fact (2.8) about an analogue of centroids for subsets of the sphere.

$n=3$

and to Benoist [Reference BenoistBen05] in general. Our proof is new, and based on a geometric argument called the box estimate (4.3). Given a sequence of strictly convex projective structures whose holonomies converge, the associated domains might degenerate. Benzécri’s compactness theorem [Reference BenzécriBen60] implies one may apply projective transformations so that the domains converge to a properly convex domain, but then the holonomies might diverge. The box estimate implies that if one chooses the conjugacies carefully, then the holonomies also converge. This involves an elementary geometric fact (2.8) about an analogue of centroids for subsets of the sphere.

The Clopen Theorem follows from the Open Theorem and the fact, due to Benoist, that a properly convex manifold that is homeomorphic to a strictly convex manifold is also strictly convex (1.11). We have made an effort to make the paper self-contained by including proofs of all the foundational results needed in Sections 1 and 2. We have endeavoured to simplify these proofs as much as possible. See [Reference BenoistBen08] for an excellent survey.

There are extensions of the Open and Closed Theorems when

![]() $M$

is the interior of a compact manifold with boundary, see [Reference Cooper, Long and TillmannCLT18] and forthcoming work. Indeed, the techniques in this paper were developed to handle this more general situation for which the pre-existing methods do not suffice. But it seems useful to present some of the main ideas in the simplest setting.

$M$

is the interior of a compact manifold with boundary, see [Reference Cooper, Long and TillmannCLT18] and forthcoming work. Indeed, the techniques in this paper were developed to handle this more general situation for which the pre-existing methods do not suffice. But it seems useful to present some of the main ideas in the simplest setting.

1. Properly and strictly convex

This section and the next review some well-known results concerning properly and strictly convex projective manifolds that are needed to prove the theorems. The results needed subsequently are (1.13)–(1.11) at the end of this section. The only mild innovation is that, to avoid appealing to results about word-hyperbolic groups, a more direct approach was taken to the proof of (1.11). The early sections of [Reference Cooper, Long and TillmannCLT15] greatly expand on the background in this section.

If

![]() $M$

is a manifold, the universal cover is

$M$

is a manifold, the universal cover is

![]() $\pi _{M}:\widetilde M \to M$

, and if

$\pi _{M}:\widetilde M \to M$

, and if

![]() $g\in \pi _1M$

, then

$g\in \pi _1M$

, then

![]() $\tau _g:\widetilde M\to \widetilde M$

is the covering transformation corresponding to

$\tau _g:\widetilde M\to \widetilde M$

is the covering transformation corresponding to

![]() $g$

. A geometry is a pair

$g$

. A geometry is a pair

![]() $(G,X)$

, where

$(G,X)$

, where

![]() $G$

is a group that acts analytically and transitively on a manifold

$G$

is a group that acts analytically and transitively on a manifold

![]() $X$

. A

$X$

. A

![]() $(G,X)$

-structure on a manifold

$(G,X)$

-structure on a manifold

![]() $M$

is determined by a development pair

$M$

is determined by a development pair

![]() $(\textrm {dev},\rho )$

that consists of the holonomy

$(\textrm {dev},\rho )$

that consists of the holonomy

![]() $\rho \in {\textrm {Hom}}(\pi _1M,G)$

and the developing map

$\rho \in {\textrm {Hom}}(\pi _1M,G)$

and the developing map

![]() $\textrm {dev}:\widetilde M\to X$

which is a local homeomorphism. The pair satisfies for all

$\textrm {dev}:\widetilde M\to X$

which is a local homeomorphism. The pair satisfies for all

![]() $x\in \widetilde M$

and

$x\in \widetilde M$

and

![]() $g\in \pi _1M$

that

$g\in \pi _1M$

that

![]() $\textrm {dev}(\tau _{g}x)=(\rho g)\textrm {dev} x$

.

$\textrm {dev}(\tau _{g}x)=(\rho g)\textrm {dev} x$

.

In what follows

![]() $V={\mathbb{R}}^{n+1}$

, its dual vector space is

$V={\mathbb{R}}^{n+1}$

, its dual vector space is

![]() $V^*={\textrm {Hom}}(V,{\mathbb{R}})$

, and

$V^*={\textrm {Hom}}(V,{\mathbb{R}})$

, and

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^{n+1}_0=V_0=V\setminus \{0\}$

. Projective space is

${\mathbb{R}}^{n+1}_0=V_0=V\setminus \{0\}$

. Projective space is

![]() ${\mathbb{P}} V=V_0/{\mathbb{R}}_0$

, and

${\mathbb{P}} V=V_0/{\mathbb{R}}_0$

, and

![]() $[A]\in {\textrm {Aut}}({\mathbb{P}} V)=\textrm {PGL}(V)$

acts on

$[A]\in {\textrm {Aut}}({\mathbb{P}} V)=\textrm {PGL}(V)$

acts on

![]() ${\mathbb{P}} V$

by

${\mathbb{P}} V$

by

![]() $[A][x]=[Ax]$

. Projective geometry is

$[A][x]=[Ax]$

. Projective geometry is

![]() $({\textrm {Aut}}({\mathbb{P}} V),{\mathbb{P}} V)$

and is also written

$({\textrm {Aut}}({\mathbb{P}} V),{\mathbb{P}} V)$

and is also written

![]() $({\textrm {Aut}}(\mathbb{RP}^n),\mathbb{RP}^n)$

. Radiant-affine geometry is

$({\textrm {Aut}}(\mathbb{RP}^n),\mathbb{RP}^n)$

. Radiant-affine geometry is

![]() $(\textrm {GL}(V),V_0)$

.

$(\textrm {GL}(V),V_0)$

.

We use the notation

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^+=(0,\infty )$

. Positive projective space is

${\mathbb{R}}^+=(0,\infty )$

. Positive projective space is

![]() $\mathbb{RP}^n_+={\mathbb{P}}_+V=V_0/{\mathbb{R}}^+$

and

$\mathbb{RP}^n_+={\mathbb{P}}_+V=V_0/{\mathbb{R}}^+$

and

![]() $[x]_+=\{\lambda x:\lambda \gt 0\}$

for

$[x]_+=\{\lambda x:\lambda \gt 0\}$

for

![]() $x\in V_0$

. Sometimes we identify

$x\in V_0$

. Sometimes we identify

![]() ${\mathbb{P}}_+V$

with the unit sphere

${\mathbb{P}}_+V$

with the unit sphere

![]() $S^n\subset {\mathbb{R}}^{n+1}$

via

$S^n\subset {\mathbb{R}}^{n+1}$

via

![]() $[x]_+\equiv x/\|x\|$

. The group

$[x]_+\equiv x/\|x\|$

. The group

![]() ${\textrm {Aut}}({\mathbb{P}}_+V):=\textrm {SL}_{\pm }(V)\subset \textrm {GL}(V)$

is the subgroup with

${\textrm {Aut}}({\mathbb{P}}_+V):=\textrm {SL}_{\pm }(V)\subset \textrm {GL}(V)$

is the subgroup with

![]() $\det =\pm 1$

. Positive projective geometry

$\det =\pm 1$

. Positive projective geometry

![]() $({\textrm {Aut}}({\mathbb{P}}_+V),{\mathbb{P}}_+V)$

is the double cover of projective geometry. We will pass back and forth between projective geometry and positive projective geometry without mention, often omitting the term positive.

$({\textrm {Aut}}({\mathbb{P}}_+V),{\mathbb{P}}_+V)$

is the double cover of projective geometry. We will pass back and forth between projective geometry and positive projective geometry without mention, often omitting the term positive.

If

![]() $U$

is a vector subspace of

$U$

is a vector subspace of

![]() $V$

, then

$V$

, then

![]() ${\mathbb{P}} U$

is a projective subspace of

${\mathbb{P}} U$

is a projective subspace of

![]() ${\mathbb{P}} V$

. This is a (projective) line if

${\mathbb{P}} V$

. This is a (projective) line if

![]() $\dim U=2$

and a (projective) hyperplane if

$\dim U=2$

and a (projective) hyperplane if

![]() $\dim U=\dim V-1$

. The (projective) dual of

$\dim U=\dim V-1$

. The (projective) dual of

![]() $U$

is the projective subspace

$U$

is the projective subspace

![]() ${\mathbb{P}} U^0\subset {\mathbb{P}} V^*$

where

${\mathbb{P}} U^0\subset {\mathbb{P}} V^*$

where

![]() $U^0=\{\phi \in V^* :\phi (U)=0\}$

. We use the same terminology in positive projective geometry. By lifting developing maps one obtains the following.

$U^0=\{\phi \in V^* :\phi (U)=0\}$

. We use the same terminology in positive projective geometry. By lifting developing maps one obtains the following.

Proposition 1.1.

Every projective structure on

![]() $M$

lifts to a positive projective structure.

$M$

lifts to a positive projective structure.

The frontier of a subset

![]() $X\subset Y$

is

$X\subset Y$

is

![]() $\textrm {Fr} X=\textrm {cl}(X)\setminus \textrm {int}(X)$

, and the boundary is

$\textrm {Fr} X=\textrm {cl}(X)\setminus \textrm {int}(X)$

, and the boundary is

![]() $\partial X=X\cap \textrm {Fr} X$

. A segment is a connected, proper subset of a projective line that contains more than one point. In what follows

$\partial X=X\cap \textrm {Fr} X$

. A segment is a connected, proper subset of a projective line that contains more than one point. In what follows

![]() $\Omega \subset \mathbb{RP}^n$

. If

$\Omega \subset \mathbb{RP}^n$

. If

![]() $H$

is a hyperplane and

$H$

is a hyperplane and

![]() $x\in H\cap \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

and

$x\in H\cap \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

and

![]() $H\cap \textrm {int}\Omega =\emptyset$

, then

$H\cap \textrm {int}\Omega =\emptyset$

, then

![]() $H$

is called a supporting hyperplane (to

$H$

is called a supporting hyperplane (to

![]() $\Omega$

) at

$\Omega$

) at

![]() $x$

. The set

$x$

. The set

![]() $\Omega$

:

$\Omega$

:

-

• is convex if every pair of points in

$\Omega$

is contained in a segment in

$\Omega$

is contained in a segment in

$\Omega$

;

$\Omega$

; -

• is properly convex if it is convex, and

$\textrm {cl}\Omega$

does not contain a projective line;

$\textrm {cl}\Omega$

does not contain a projective line; -

• is strictly convex if it is properly convex and

$\textrm {Fr}\Omega$

does not contain a segment;

$\textrm {Fr}\Omega$

does not contain a segment; -

• is flat if it is convex and

$\dim \Omega \lt n$

;

$\dim \Omega \lt n$

; -

• is a convex domain if it is a properly convex open set;

-

• is

$C^1$

if for each

$C^1$

if for each

$x\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

there is a unique supporting hyperplane at

$x\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

there is a unique supporting hyperplane at

$x$

.

$x$

.

The same terms will be applied to a lift of

![]() $\Omega$

to

$\Omega$

to

![]() ${\mathbb{R}\textrm {P}_+}^n$

. If

${\mathbb{R}\textrm {P}_+}^n$

. If

![]() $V=U\oplus W$

, then projection from

$V=U\oplus W$

, then projection from

![]() ${\mathbb{P}} W$

onto

${\mathbb{P}} W$

onto

![]() ${\mathbb{P}} U$

is

${\mathbb{P}} U$

is

![]() $\pi :{\mathbb{P}} V\setminus {\mathbb{P}} W\longrightarrow {\mathbb{P}} U$

given by

$\pi :{\mathbb{P}} V\setminus {\mathbb{P}} W\longrightarrow {\mathbb{P}} U$

given by

![]() $\pi [u+w]=[u]$

. Duality is the map that sends each point

$\pi [u+w]=[u]$

. Duality is the map that sends each point

![]() $\theta =[\phi ]\in {\mathbb{P}} V^*$

to the hyperplane

$\theta =[\phi ]\in {\mathbb{P}} V^*$

to the hyperplane

![]() $H_{\theta }={\mathbb{P}}\ker \phi \subset {\mathbb{P}} V$

. If

$H_{\theta }={\mathbb{P}}\ker \phi \subset {\mathbb{P}} V$

. If

![]() $L$

is a line in

$L$

is a line in

![]() ${\mathbb{P}} V^*$

the hyperplanes

${\mathbb{P}} V^*$

the hyperplanes

![]() $H_{\theta }$

dual to the points

$H_{\theta }$

dual to the points

![]() $\theta \in L$

are called a pencil of hyperplanes. Then

$\theta \in L$

are called a pencil of hyperplanes. Then

![]() $Q=\cap H_{\theta }$

is the projective dual of

$Q=\cap H_{\theta }$

is the projective dual of

![]() $L$

and is called the core of the pencil. It is a codimension

$L$

and is called the core of the pencil. It is a codimension

![]() $2$

projective subspace.

$2$

projective subspace.

Lemma 1.2.

A convex set

![]() $\Omega$

is properly convex if and only if

$\Omega$

is properly convex if and only if

![]() $\textrm {cl}\Omega$

is disjoint from some hyperplane.

$\textrm {cl}\Omega$

is disjoint from some hyperplane.

Proof.

Without loss of generality, suppose

![]() $\Omega$

is closed. The reverse implication is immediate since the complement of a hyperplane contains no line.

$\Omega$

is closed. The reverse implication is immediate since the complement of a hyperplane contains no line.

Hence, assume

![]() $\Omega$

is properly convex. The result is immediate if

$\Omega$

is properly convex. The result is immediate if

![]() $n=1$

, so assume

$n=1$

, so assume

![]() $n\gt 1$

. Since

$n\gt 1$

. Since

![]() $\Omega$

is convex and contains no projective line, it is simply connected, and so lifts to

$\Omega$

is convex and contains no projective line, it is simply connected, and so lifts to

![]() $\Omega ^{\prime}\subset {\mathbb{R}\textrm {P}_+}^n$

. Let

$\Omega ^{\prime}\subset {\mathbb{R}\textrm {P}_+}^n$

. Let

![]() $H\subset {\mathbb{R}\textrm {P}_+}^n$

be a hyperplane. Then

$H\subset {\mathbb{R}\textrm {P}_+}^n$

be a hyperplane. Then

![]() $H\cap \Omega ^{\prime}$

is empty or properly convex. By induction on dimension,

$H\cap \Omega ^{\prime}$

is empty or properly convex. By induction on dimension,

![]() $H$

contains a projective subspace

$H$

contains a projective subspace

![]() $Q$

with

$Q$

with

![]() $\dim Q=n-2$

that is disjoint from

$\dim Q=n-2$

that is disjoint from

![]() $H\cap \Omega ^{\prime}$

. There is a pencil of hyperplanes

$H\cap \Omega ^{\prime}$

. There is a pencil of hyperplanes

![]() $H_{\theta }$

with core

$H_{\theta }$

with core

![]() $Q$

. Now

$Q$

. Now

![]() $\Omega ^{\prime}\cap H_{\theta }$

is contained in one of the two components of

$\Omega ^{\prime}\cap H_{\theta }$

is contained in one of the two components of

![]() $H_{\theta }\setminus Q$

. As

$H_{\theta }\setminus Q$

. As

![]() $\theta$

moves half way around

$\theta$

moves half way around

![]() ${\mathbb{R}\textrm {P}_+}^1$

the component must change. Thus for some

${\mathbb{R}\textrm {P}_+}^1$

the component must change. Thus for some

![]() $\theta$

the intersection is empty.

$\theta$

the intersection is empty.

In what follows

![]() $\Omega \subset \mathbb{RP}^n$

is a properly convex domain, and

$\Omega \subset \mathbb{RP}^n$

is a properly convex domain, and

![]() ${\textrm {Aut}}(\Omega )\subset {\textrm {Aut}}(\mathbb{RP}^n)$

is the subgroup that preserves

${\textrm {Aut}}(\Omega )\subset {\textrm {Aut}}(\mathbb{RP}^n)$

is the subgroup that preserves

![]() $\Omega$

. The Hilbert metric

$\Omega$

. The Hilbert metric

![]() $d_{\Omega }$

on

$d_{\Omega }$

on

![]() $\Omega$

is defined as follows. If

$\Omega$

is defined as follows. If

![]() $\ell \subset \mathbb{RP}^n$

is a line and

$\ell \subset \mathbb{RP}^n$

is a line and

![]() $\alpha =\Omega \cap \ell \ne \emptyset$

, then

$\alpha =\Omega \cap \ell \ne \emptyset$

, then

![]() $\alpha$

is a proper segment in

$\alpha$

is a proper segment in

![]() $\Omega$

and

$\Omega$

and

![]() $\alpha =(a_-,a_+)$

with

$\alpha =(a_-,a_+)$

with

![]() $a_{\pm }\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. There is a projective isomorphism

$a_{\pm }\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. There is a projective isomorphism

![]() $f:\alpha \rightarrow {\mathbb{R}}^+$

and

$f:\alpha \rightarrow {\mathbb{R}}^+$

and

for

![]() $x,y\in \alpha$

. It follows from the next result that

$x,y\in \alpha$

. It follows from the next result that

![]() $d_{\Omega }$

satisfies the triangle inequality, and thus is a metric. It is a Finsler metric: given by a norm on the tangent space. The factor of

$d_{\Omega }$

satisfies the triangle inequality, and thus is a metric. It is a Finsler metric: given by a norm on the tangent space. The factor of

![]() $1/2$

ensures that this gives the hyperbolic metric when

$1/2$

ensures that this gives the hyperbolic metric when

![]() $\Omega$

is a round disc. A geodesic in

$\Omega$

is a round disc. A geodesic in

![]() $\Omega$

is a curve whose length is the distance between its endpoints. It is immediate that

$\Omega$

is a curve whose length is the distance between its endpoints. It is immediate that

![]() ${\textrm {Aut}}(\Omega )$

acts by isometries of

${\textrm {Aut}}(\Omega )$

acts by isometries of

![]() $d_{\Omega }$

.

$d_{\Omega }$

.

The interior of a triangle in the projective plane is a properly convex domain that is projectively equivalent to the positive quadrant in an affine patch

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^2$

. A metric ball in this domain with center

${\mathbb{R}}^2$

. A metric ball in this domain with center

![]() $p$

is a hexagon. The vertices of the hexagon lie on the lines through

$p$

is a hexagon. The vertices of the hexagon lie on the lines through

![]() $p$

that contain a vertex of the triangle. A smooth curve in the interior of a triangle is a geodesic for the Hilbert metric if, and only if, the tangent line at each point on the curve intersects the same pair of sides of the triangle. Thus, in a properly convex domain, there may be many geodesics with the same endpoints.

$p$

that contain a vertex of the triangle. A smooth curve in the interior of a triangle is a geodesic for the Hilbert metric if, and only if, the tangent line at each point on the curve intersects the same pair of sides of the triangle. Thus, in a properly convex domain, there may be many geodesics with the same endpoints.

Let

![]() $H_{\pm }$

be supporting hyperplanes for

$H_{\pm }$

be supporting hyperplanes for

![]() $\Omega$

at

$\Omega$

at

![]() $a_{\pm }\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

, and

$a_{\pm }\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

, and

![]() $P=H_+\cap H_-$

. Projection from

$P=H_+\cap H_-$

. Projection from

![]() $P$

onto

$P$

onto

![]() $\alpha$

is the map

$\alpha$

is the map

![]() $\pi :\Omega \to \alpha =(a_-,a_+)$

given by

$\pi :\Omega \to \alpha =(a_-,a_+)$

given by

![]() $\pi [u+v]=[v]$

where

$\pi [u+v]=[v]$

where

![]() $[u]\in P$

and

$[u]\in P$

and

![]() $[v]\in \alpha$

. The choice of

$[v]\in \alpha$

. The choice of

![]() $H_{\pm }$

is unique only if

$H_{\pm }$

is unique only if

![]() $a_{\pm }$

are

$a_{\pm }$

are

![]() $C^1$

points. If

$C^1$

points. If

![]() $\Omega$

is strictly convex, then for each

$\Omega$

is strictly convex, then for each

![]() $x\in \Omega$

by (1.3)(iii) there is a unique point

$x\in \Omega$

by (1.3)(iii) there is a unique point

![]() $\Pi (x)\in \alpha$

closest to

$\Pi (x)\in \alpha$

closest to

![]() $x$

, and

$x$

, and

![]() $\Pi :\Omega \rightarrow \alpha$

is continuous and called the nearest point retraction. In general

$\Pi :\Omega \rightarrow \alpha$

is continuous and called the nearest point retraction. In general

![]() $\pi \ne \Pi$

.

$\pi \ne \Pi$

.

Lemma 1.3. With the preceding notation we have the following:

-

(i)

$d_{\Omega }(x,y)\geqslant d_{\Omega }(\pi x,\pi y)$

;

$d_{\Omega }(x,y)\geqslant d_{\Omega }(\pi x,\pi y)$

;

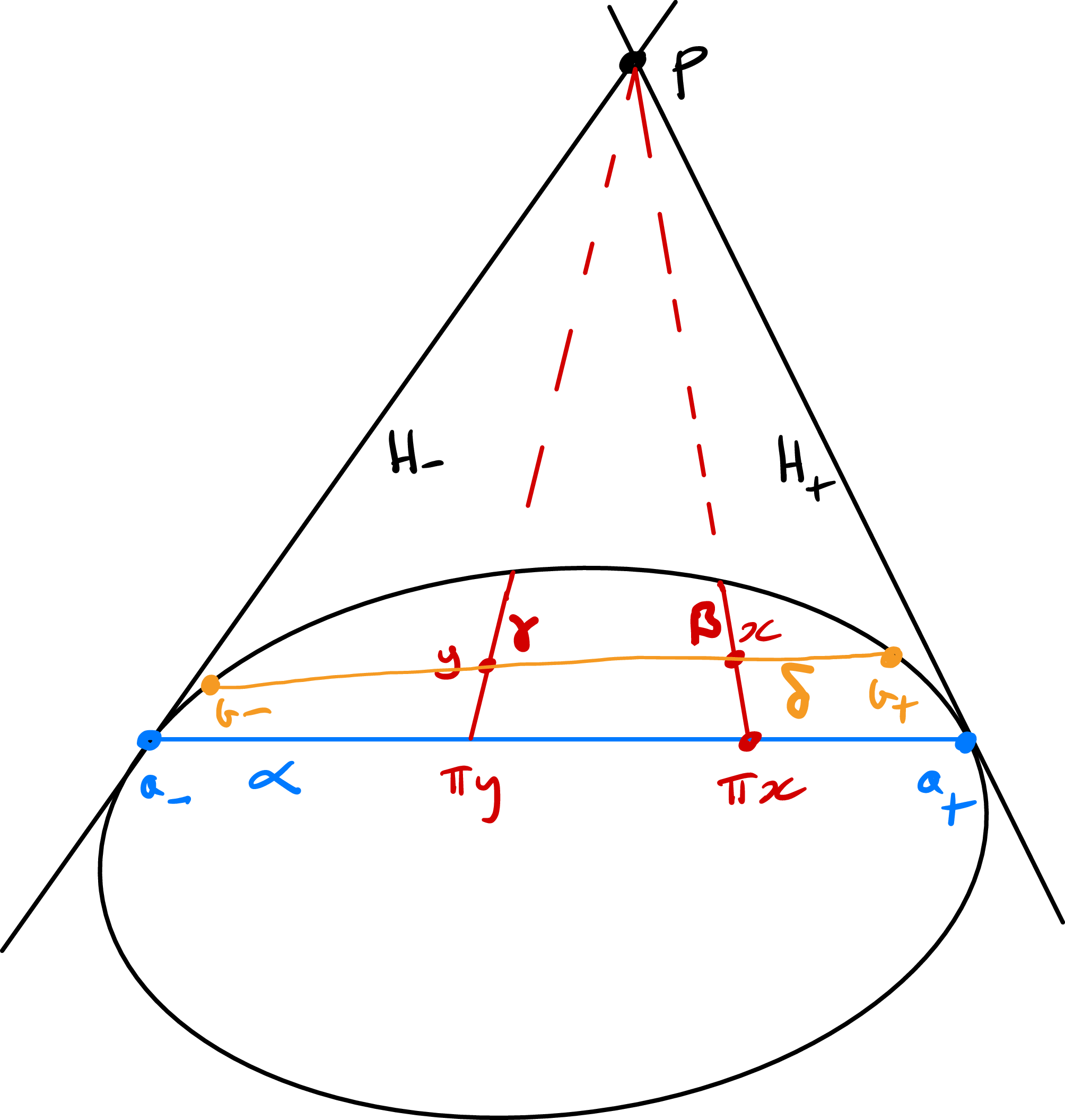

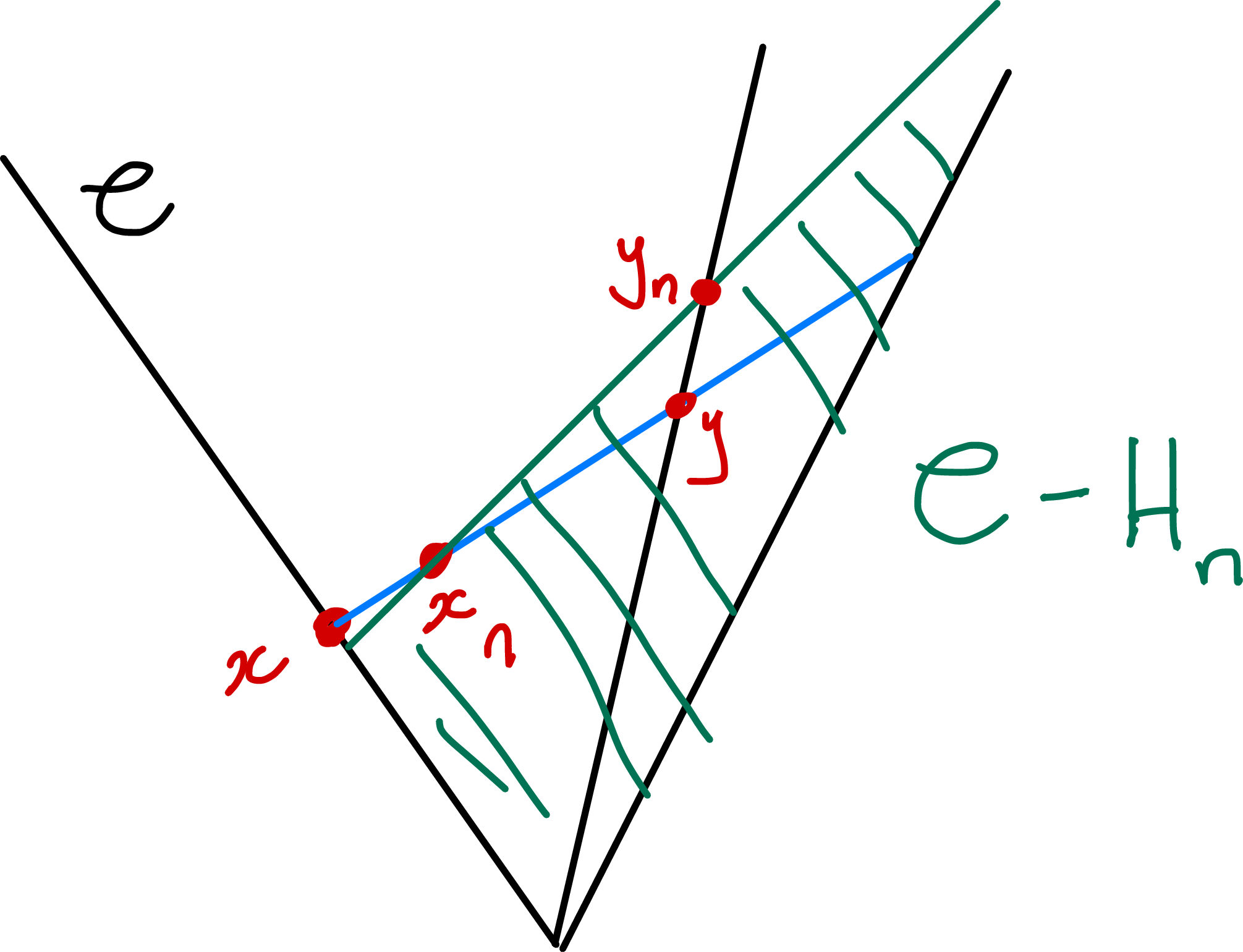

Figure 1. Projecting onto a line.

-

(ii) If

$\Omega$

is strictly convex, then geodesics are segments of lines;

$\Omega$

is strictly convex, then geodesics are segments of lines;

-

(iii) If

$\Omega$

is strictly convex, then

$\Omega$

is strictly convex, then

$\forall \ y\in \Omega \ \ \{x\in \Omega : d_{\Omega }(x,y)\leqslant 1\}$

is strictly convex.

$\forall \ y\in \Omega \ \ \{x\in \Omega : d_{\Omega }(x,y)\leqslant 1\}$

is strictly convex.

Proof.

Figure 1 represents two or more dimensions. Let

![]() $\delta =(b_-,b_+)$

be the proper segment in

$\delta =(b_-,b_+)$

be the proper segment in

![]() $\Omega$

containing

$\Omega$

containing

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $y$

, and

$y$

, and

![]() $\pi :\Omega \rightarrow \alpha$

as above. Then

$\pi :\Omega \rightarrow \alpha$

as above. Then

![]() $d_{\Omega }(x,y)=d_{\delta }(x,y)$

. Since

$d_{\Omega }(x,y)=d_{\delta }(x,y)$

. Since

![]() $(\pi |\delta ):\delta \to \alpha$

is a projective embedding

$(\pi |\delta ):\delta \to \alpha$

is a projective embedding

![]() $d_{\delta }(x,y)=d_{\pi \delta }(\pi x,\pi y)$

. Also

$d_{\delta }(x,y)=d_{\pi \delta }(\pi x,\pi y)$

. Also

![]() $d_{\pi \delta }(\pi x,\pi y)\geqslant d_{\alpha }(\pi x,\pi y)$

because

$d_{\pi \delta }(\pi x,\pi y)\geqslant d_{\alpha }(\pi x,\pi y)$

because

![]() $\pi \delta \subset \alpha$

. Finally

$\pi \delta \subset \alpha$

. Finally

![]() $d_{\alpha }(\pi x,\pi y)=d_{\Omega }(\pi x,\pi y)$

, which proves (i).

$d_{\alpha }(\pi x,\pi y)=d_{\Omega }(\pi x,\pi y)$

, which proves (i).

Equality implies

![]() $\alpha =\pi \delta$

. Thus, after relabelling if needed,

$\alpha =\pi \delta$

. Thus, after relabelling if needed,

![]() $b_{\pm }\in H_{\pm }$

. Thus

$b_{\pm }\in H_{\pm }$

. Thus

![]() $[a_{\pm },b_{\pm }]\subset H_{\pm }\cap \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. If

$[a_{\pm },b_{\pm }]\subset H_{\pm }\cap \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. If

![]() $\Omega$

is strictly convex it follows that

$\Omega$

is strictly convex it follows that

![]() $b_{\pm }=a_{\pm }$

. This gives (ii). For (iii) see [Reference Cooper, Long and TillmannCLT15, (1.7)].

$b_{\pm }=a_{\pm }$

. This gives (ii). For (iii) see [Reference Cooper, Long and TillmannCLT15, (1.7)].

A line in a projective manifold is flat connected

![]() $1$

-manifold. A projective manifold

$1$

-manifold. A projective manifold

![]() $M$

is convex if every pair of points in

$M$

is convex if every pair of points in

![]() $M$

are contained in a line. The developing map might not be injective on a lift of a line. For example, every covering space of

$M$

are contained in a line. The developing map might not be injective on a lift of a line. For example, every covering space of

![]() $\mathbb{RP}^1$

is convex. It is easy to see (cf. Figure 2) the following.

$\mathbb{RP}^1$

is convex. It is easy to see (cf. Figure 2) the following.

Proposition 1.4.

Suppose that

![]() $\Omega$

is properly convex and

$\Omega$

is properly convex and

![]() $\gamma _1,\gamma _2:[0,1)\to \Omega$

are two lines that are both contained in the same projective plane, and

$\gamma _1,\gamma _2:[0,1)\to \Omega$

are two lines that are both contained in the same projective plane, and

![]() $p_i=\lim _{t\to 1}\gamma _i(t)\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. Let

$p_i=\lim _{t\to 1}\gamma _i(t)\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. Let

![]() $f(t)=d_{\Omega }(\gamma _1(t),\gamma _2)$

.

$f(t)=d_{\Omega }(\gamma _1(t),\gamma _2)$

.

-

(i) If

$p_1=p_2$

, then

$p_1=p_2$

, then

$f$

is a non-increasing function. Moreover,

$f$

is a non-increasing function. Moreover,

$f(t)\to 0$

if and only if

$f(t)\to 0$

if and only if

$\Omega$

is

$\Omega$

is

$C^1$

at

$C^1$

at

$p_1$

.

$p_1$

. -

(ii) If

$p_1\ne p_2$

, then

$p_1\ne p_2$

, then

$f$

is bounded if and only if there is a segment in

$f$

is bounded if and only if there is a segment in

$\textrm {Fr}\Omega$

that contains both

$\textrm {Fr}\Omega$

that contains both

$p_1$

and

$p_1$

and

$p_2$

in its interior.

$p_2$

in its interior.

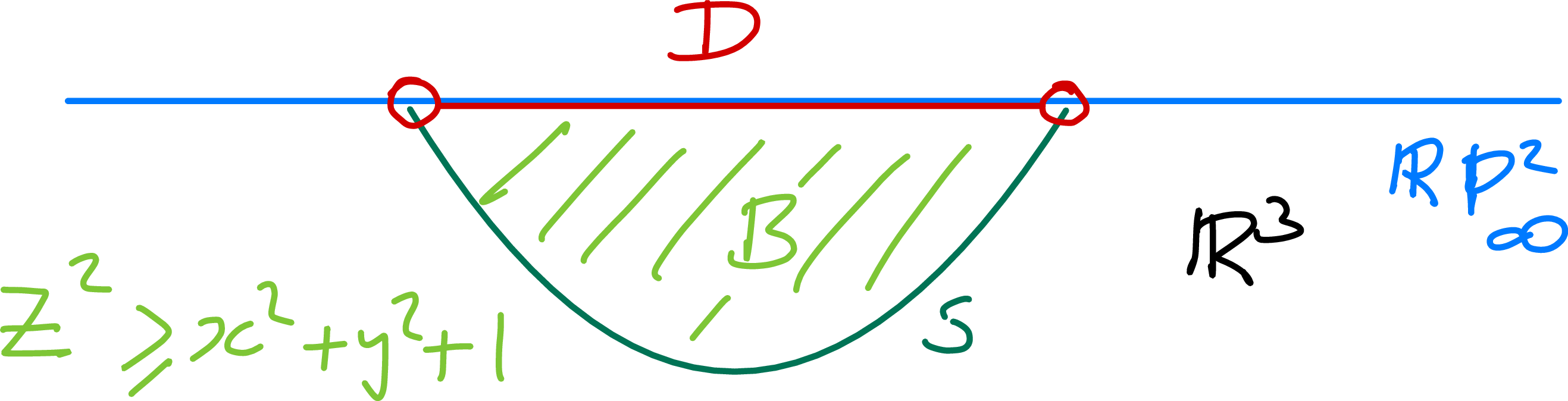

Figure 2. Distance between two lines near infinity.

A subset

![]() $\mathcal{C}\subset V_0$

is a cone if

$\mathcal{C}\subset V_0$

is a cone if

![]() $t\cdot \mathcal{C}=\mathcal{C}$

for all

$t\cdot \mathcal{C}=\mathcal{C}$

for all

![]() $t\gt 0$

. The dual cone

$t\gt 0$

. The dual cone

![]() $\mathcal{C}^*=\textrm {int}\left (\{\phi \in V^*:\ \phi (\mathcal{C})\geqslant 0\}\right )$

is convex. If

$\mathcal{C}^*=\textrm {int}\left (\{\phi \in V^*:\ \phi (\mathcal{C})\geqslant 0\}\right )$

is convex. If

![]() $\Omega \subset {\mathbb{P}}_+ V$

, then

$\Omega \subset {\mathbb{P}}_+ V$

, then

![]() $\mathcal{C}\Omega$

is the cone

$\mathcal{C}\Omega$

is the cone

![]() $\{v\in V_0:\ [v]_+\in \Omega \}$

. If

$\{v\in V_0:\ [v]_+\in \Omega \}$

. If

![]() $\Omega$

is open and properly convex, then the dual domain

$\Omega$

is open and properly convex, then the dual domain

![]() $\Omega ^*={\mathbb{P}}(\mathcal{C}\Omega ^*)$

is open, and properly convex. Using the natural identification

$\Omega ^*={\mathbb{P}}(\mathcal{C}\Omega ^*)$

is open, and properly convex. Using the natural identification

![]() $V\cong V^{**}$

it is immediate that

$V\cong V^{**}$

it is immediate that

![]() $(\Omega ^*)^*=\Omega$

.

$(\Omega ^*)^*=\Omega$

.

Corollary 1.5.

If

![]() $\Omega$

is open and properly convex, then

$\Omega$

is open and properly convex, then

![]() $\Omega$

is

$\Omega$

is

![]() $C^1$

(respectively strictly convex) if and only if

$C^1$

(respectively strictly convex) if and only if

![]() $\Omega ^*$

is strictly convex (respectively

$\Omega ^*$

is strictly convex (respectively

![]() $C^1$

).

$C^1$

).

Proof.

We have

![]() $[\phi ]\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega ^*$

if and only if the dual hyperplane

$[\phi ]\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega ^*$

if and only if the dual hyperplane

![]() $H={\mathbb{P}}\ker \phi$

supports

$H={\mathbb{P}}\ker \phi$

supports

![]() $\Omega$

. In this case we will always assume that

$\Omega$

. In this case we will always assume that

![]() $\phi (\Omega )\geqslant 0$

. If

$\phi (\Omega )\geqslant 0$

. If

![]() $p\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

, then there are two distinct supporting hyperplanes

$p\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

, then there are two distinct supporting hyperplanes

![]() $H_0={\mathbb{P}}\ker \phi _0$

and

$H_0={\mathbb{P}}\ker \phi _0$

and

![]() $H_1={\mathbb{P}}\ker \phi _1$

for

$H_1={\mathbb{P}}\ker \phi _1$

for

![]() $\Omega$

at

$\Omega$

at

![]() $p$

if and only if all the hyperplanes

$p$

if and only if all the hyperplanes

![]() $H_t={\mathbb{P}}\ker \phi _t$

contain

$H_t={\mathbb{P}}\ker \phi _t$

contain

![]() $p$

and support

$p$

and support

![]() $\Omega$

, where

$\Omega$

, where

![]() $\phi _t=(1-t)\phi _0+t\phi _1$

and

$\phi _t=(1-t)\phi _0+t\phi _1$

and

![]() $0\leqslant t\leqslant 1.$

This happens if and only if the segment

$0\leqslant t\leqslant 1.$

This happens if and only if the segment

![]() $\sigma =\{[\phi _t]:\ 0\leqslant t\leqslant 1\}$

is in

$\sigma =\{[\phi _t]:\ 0\leqslant t\leqslant 1\}$

is in

![]() $\textrm {Fr}\Omega ^*$

. Hence,

$\textrm {Fr}\Omega ^*$

. Hence,

![]() $\Omega$

is

$\Omega$

is

![]() $C^1$

if and only if

$C^1$

if and only if

![]() $\Omega ^*$

is strictly convex. Replacing

$\Omega ^*$

is strictly convex. Replacing

![]() $\Omega$

by

$\Omega$

by

![]() $\Omega ^*$

and using

$\Omega ^*$

and using

![]() $\Omega ^{**}=\Omega$

gives the other result.

$\Omega ^{**}=\Omega$

gives the other result.

If

![]() $\Gamma \subset {\textrm {Aut}}(\Omega )$

is a discrete and torsion-free subgroup, then

$\Gamma \subset {\textrm {Aut}}(\Omega )$

is a discrete and torsion-free subgroup, then

![]() $M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a properly (respectively strictly) convex manifold if

$M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a properly (respectively strictly) convex manifold if

![]() $\Omega$

is properly (respectively strictly) convex. Then

$\Omega$

is properly (respectively strictly) convex. Then

![]() $\widetilde M=\Omega$

and there is a development pair

$\widetilde M=\Omega$

and there is a development pair

![]() $(\textrm {dev},\rho )$

, where

$(\textrm {dev},\rho )$

, where

![]() $\textrm {dev}$

is the identity map, and the holonomy

$\textrm {dev}$

is the identity map, and the holonomy

![]() $\rho :\pi _1M\to \Gamma$

is an isomorphism.

$\rho :\pi _1M\to \Gamma$

is an isomorphism.

The tautological line bundle is the quotient map

![]() $\pi :V_0\rightarrow {\mathbb{P}} V$

. If

$\pi :V_0\rightarrow {\mathbb{P}} V$

. If

![]() $M$

is a projective manifold modelled on

$M$

is a projective manifold modelled on

![]() ${\mathbb{P}} V$

, then the pull-back of this line bundle by the developing map

${\mathbb{P}} V$

, then the pull-back of this line bundle by the developing map

![]() $\textrm {dev}:\widetilde M\rightarrow {\mathbb{P}} V$

is a line bundle over

$\textrm {dev}:\widetilde M\rightarrow {\mathbb{P}} V$

is a line bundle over

![]() $\widetilde M$

. Covering transformations induce bundle isomorphisms, and the quotient is a line bundle over

$\widetilde M$

. Covering transformations induce bundle isomorphisms, and the quotient is a line bundle over

![]() $M$

called the tautological line bundle. It is a trivial bundle, since the lines can be oriented to point away from

$M$

called the tautological line bundle. It is a trivial bundle, since the lines can be oriented to point away from

![]() $0$

.

$0$

.

This bundle has a natural structure as a radiant-affine manifold. In the case that

![]() $M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is properly convex, the holonomy lifts to

$M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is properly convex, the holonomy lifts to

![]() $\widetilde \Gamma \subset \textrm {SL}_{\pm } V$

. Then this bundle over

$\widetilde \Gamma \subset \textrm {SL}_{\pm } V$

. Then this bundle over

![]() $\widetilde M$

is naturally identified with

$\widetilde M$

is naturally identified with

![]() $\mathcal{C}\Omega$

and the quotient

$\mathcal{C}\Omega$

and the quotient

![]() $\mathcal{C}\Omega /\widetilde \Gamma$

is a radiant-affine manifold (3.3) that can be naturally identified with the tautological line bundle over

$\mathcal{C}\Omega /\widetilde \Gamma$

is a radiant-affine manifold (3.3) that can be naturally identified with the tautological line bundle over

![]() $M$

. This plays a key role in the proof of the Open Theorem. If

$M$

. This plays a key role in the proof of the Open Theorem. If

![]() $X$

is a subset of a metric space

$X$

is a subset of a metric space

![]() $Y$

, the

$Y$

, the

![]() $r$

-neighborhood of

$r$

-neighborhood of

![]() $X$

is

$X$

is

We now use a compactness argument to show that if

![]() $\Omega$

is the universal cover of a closed strictly convex manifold, then projection from a projective subspace onto a geodesic in

$\Omega$

is the universal cover of a closed strictly convex manifold, then projection from a projective subspace onto a geodesic in

![]() $\Omega$

is uniformly distance decreasing in the following sense.

$\Omega$

is uniformly distance decreasing in the following sense.

Lemma 1.6.

Suppose

![]() $M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a strictly convex closed manifold. Given

$M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a strictly convex closed manifold. Given

![]() $b\gt 1$

there is

$b\gt 1$

there is

![]() $R=R(b)\gt 0$

so the following holds. Suppose

$R=R(b)\gt 0$

so the following holds. Suppose

![]() $\pi :\Omega \to \alpha$

is a projection onto a geodesic

$\pi :\Omega \to \alpha$

is a projection onto a geodesic

![]() $\alpha$

. Suppose that

$\alpha$

. Suppose that

![]() $\eta$

is a rectifiable arc in

$\eta$

is a rectifiable arc in

![]() $\Omega \setminus N_R(\alpha )$

of length

$\Omega \setminus N_R(\alpha )$

of length

![]() $\ell$

with endpoints

$\ell$

with endpoints

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $y$

. Then

$y$

. Then

![]() $d_{\Omega }(\pi x,\pi y)\lt 1+(\ell /b)$

.

$d_{\Omega }(\pi x,\pi y)\lt 1+(\ell /b)$

.

Proof.

By decomposing

![]() $\eta$

into finitely many subarcs, with one of length at most

$\eta$

into finitely many subarcs, with one of length at most

![]() $b$

, and

$b$

, and

![]() $\lfloor \ell /b \rfloor$

of length

$\lfloor \ell /b \rfloor$

of length

![]() $b$

, it suffices to prove if

$b$

, it suffices to prove if

![]() ${\textrm {length}}(\eta )\leqslant b$

, then

${\textrm {length}}(\eta )\leqslant b$

, then

![]() $d_{\Omega }(\pi x,\pi y)\leqslant 1$

.

$d_{\Omega }(\pi x,\pi y)\leqslant 1$

.

Write

![]() $d=d_{\Omega }$

. If no such

$d=d_{\Omega }$

. If no such

![]() $R$

exists, then there are sequences

$R$

exists, then there are sequences

![]() $x_k,y_k\in \Omega$

and projections

$x_k,y_k\in \Omega$

and projections

![]() $\pi _{_k}:\Omega \to \alpha _k$

with

$\pi _{_k}:\Omega \to \alpha _k$

with

![]() $d(x_k,y_k)\leqslant b$

and

$d(x_k,y_k)\leqslant b$

and

![]() $d(x_k,\alpha _k)\geqslant k$

and

$d(x_k,\alpha _k)\geqslant k$

and

![]() $1\leqslant d(\pi _{_k} x_k,\pi _{_k} y_k)\leqslant b$

. Then

$1\leqslant d(\pi _{_k} x_k,\pi _{_k} y_k)\leqslant b$

. Then

![]() $\beta _k=[\pi _k x_k,x_k]$

and

$\beta _k=[\pi _k x_k,x_k]$

and

![]() $\gamma _k=[\pi _{_k} y_k,y_k]$

are geodesic segments and

$\gamma _k=[\pi _{_k} y_k,y_k]$

are geodesic segments and

![]() $\pi _{_k}\beta _k=\pi _{_k} x_k$

and

$\pi _{_k}\beta _k=\pi _{_k} x_k$

and

![]() $\pi _{_k}\gamma _k=\pi _{_k}y_k$

.

$\pi _{_k}\gamma _k=\pi _{_k}y_k$

.

There is a compact subset

![]() $W\subset \Omega$

such that

$W\subset \Omega$

such that

![]() $\Gamma \cdot W=\Omega$

. By applying an element of

$\Gamma \cdot W=\Omega$

. By applying an element of

![]() $\Gamma$

we may assume that

$\Gamma$

we may assume that

![]() $\pi _{_k}x_k\in W$

. After subsequencing we may assume

$\pi _{_k}x_k\in W$

. After subsequencing we may assume

![]() $\beta =\lim \beta _k$

,

$\beta =\lim \beta _k$

,

![]() $\gamma =\lim \gamma _k$

,

$\gamma =\lim \gamma _k$

,

![]() $\alpha =\lim \alpha _k$

and

$\alpha =\lim \alpha _k$

and

![]() $\pi =\lim \pi _{_k}$

all exist and

$\pi =\lim \pi _{_k}$

all exist and

![]() $\pi :\Omega \to \alpha$

is projection. Refer to Figure 1. Thus

$\pi :\Omega \to \alpha$

is projection. Refer to Figure 1. Thus

![]() $\beta$

are

$\beta$

are

![]() $\gamma$

are geodesic rays in

$\gamma$

are geodesic rays in

![]() $\Omega$

that start on

$\Omega$

that start on

![]() $\alpha$

, and end on

$\alpha$

, and end on

![]() $\textrm {Fr}\Omega$

, with

$\textrm {Fr}\Omega$

, with

![]() $\pi (\beta )=\alpha \cap \beta \ne \alpha \cap \gamma =\pi (\gamma )$

.

$\pi (\beta )=\alpha \cap \beta \ne \alpha \cap \gamma =\pi (\gamma )$

.

Since

![]() $\Omega$

is strictly convex, and

$\Omega$

is strictly convex, and

![]() $d(x_k,y_k)\leqslant b$

, it follows from (1.4) that

$d(x_k,y_k)\leqslant b$

, it follows from (1.4) that

![]() $x_k$

and

$x_k$

and

![]() $y_k$

limit on the same point

$y_k$

limit on the same point

![]() $p\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. Hence

$p\in \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. Hence

![]() $p$

is the endpoint of both

$p$

is the endpoint of both

![]() $\beta$

and

$\beta$

and

![]() $\gamma$

on

$\gamma$

on

![]() $\textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. Also

$\textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. Also

![]() $p\in P=H_-\cap H_+$

, where

$p\in P=H_-\cap H_+$

, where

![]() $H_{\pm }$

are the supporting hyperplanes to

$H_{\pm }$

are the supporting hyperplanes to

![]() $\Omega$

at the endpoints of

$\Omega$

at the endpoints of

![]() $\alpha$

. Since

$\alpha$

. Since

![]() $\Omega$

is strictly convex,

$\Omega$

is strictly convex,

![]() $p\notin P$

. It follows that

$p\notin P$

. It follows that

![]() $\pi (\beta )=\pi (p)=\pi (\gamma )$

which is a contradiction.

$\pi (\beta )=\pi (p)=\pi (\gamma )$

which is a contradiction.

The following is due to Benoist [Reference BenoistBen04]. A triangle is a disc

![]() $\Delta$

in a projective plane bounded by three segments. If

$\Delta$

in a projective plane bounded by three segments. If

![]() $\Delta \subset \textrm {cl}\Omega$

and

$\Delta \subset \textrm {cl}\Omega$

and

![]() $\Delta \cap \textrm {Fr}\Omega =\partial \Delta$

, then

$\Delta \cap \textrm {Fr}\Omega =\partial \Delta$

, then

![]() $\Delta$

is called a properly embedded triangle, or PET. A properly convex set

$\Delta$

is called a properly embedded triangle, or PET. A properly convex set

![]() $\Omega$

has thin triangles if there is

$\Omega$

has thin triangles if there is

![]() $\delta \gt 0$

such that for every triangle

$\delta \gt 0$

such that for every triangle

![]() $T$

in

$T$

in

![]() $\Omega$

, each side of

$\Omega$

, each side of

![]() $T$

is contained in a

$T$

is contained in a

![]() $\delta$

-neighborhood of the union of the other two sides with respect to the Hilbert metric.

$\delta$

-neighborhood of the union of the other two sides with respect to the Hilbert metric.

Proposition 1.7.

If

![]() $M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a properly convex closed manifold, then the following are equivalent:

$M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a properly convex closed manifold, then the following are equivalent:

-

(i)

$M$

is strictly convex;

$M$

is strictly convex;

-

(ii)

$\Omega$

does not contain a PET;

$\Omega$

does not contain a PET;

-

(iii)

$\Omega$

has thin triangles.

$\Omega$

has thin triangles.

Proof.

![]() $(ii)\Rightarrow (i)$

: if

$(ii)\Rightarrow (i)$

: if

![]() $\Omega$

is not strictly convex, there is a maximal segment

$\Omega$

is not strictly convex, there is a maximal segment

![]() $\ell \subset \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. Choose

$\ell \subset \textrm {Fr}\Omega$

. Choose

![]() $x\in \Omega$

and let

$x\in \Omega$

and let

![]() $P\subset \Omega$

be the interior of the triangle that is the convex hull of

$P\subset \Omega$

be the interior of the triangle that is the convex hull of

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $\ell$

. Choose a sequence

$\ell$

. Choose a sequence

![]() $x_n$

in

$x_n$

in

![]() $P$

that limits on the midpoint of

$P$

that limits on the midpoint of

![]() $\ell$

. By (1.4)

$\ell$

. By (1.4)

![]() $d_{\Omega }(x_n,\textrm {Fr} P)\to \infty$

because

$d_{\Omega }(x_n,\textrm {Fr} P)\to \infty$

because

![]() $\ell$

is maximal. Since

$\ell$

is maximal. Since

![]() $M$

is compact there is compact set

$M$

is compact there is compact set

![]() $W\subset \Omega$

such that

$W\subset \Omega$

such that

![]() $\Gamma \cdot W=\Omega$

. Thus there is

$\Gamma \cdot W=\Omega$

. Thus there is

![]() $\gamma _n\in \Gamma$

with

$\gamma _n\in \Gamma$

with

![]() $\gamma _nx_n\in W$

. After choosing a subsequence

$\gamma _nx_n\in W$

. After choosing a subsequence

![]() $\gamma _nx_n\to y\in W$

, and

$\gamma _nx_n\to y\in W$

, and

![]() $\gamma _n P$

converges to the interior of a PET

$\gamma _n P$

converges to the interior of a PET

![]() $\Delta \subset \Omega$

that contains

$\Delta \subset \Omega$

that contains

![]() $y$

.

$y$

.

![]() $(iii)\Rightarrow (ii)$

: if

$(iii)\Rightarrow (ii)$

: if

![]() $\Omega$

contains a PET

$\Omega$

contains a PET

![]() $\Delta$

, then

$\Delta$

, then

![]() $d_{\Omega }|\Delta =d_{\Delta }.$

Now

$d_{\Omega }|\Delta =d_{\Delta }.$

Now

![]() $\textrm {PGL}(\Delta )$

contains a subgroup

$\textrm {PGL}(\Delta )$

contains a subgroup

![]() $G\cong {\mathbb{R}}^2$

that acts transitively on

$G\cong {\mathbb{R}}^2$

that acts transitively on

![]() $\Delta$

. Therefore

$\Delta$

. Therefore

![]() $(\Delta ,d_{\Delta })$

is isometric to a normed vector-space, thus does not have thin triangles.

$(\Delta ,d_{\Delta })$

is isometric to a normed vector-space, thus does not have thin triangles.

![]() $(i)\Rightarrow (iii)$

: if

$(i)\Rightarrow (iii)$

: if

![]() $\Omega$

does not have thin triangles, then there is a sequence of triangles

$\Omega$

does not have thin triangles, then there is a sequence of triangles

![]() $T_k$

in

$T_k$

in

![]() $\Omega$

and points

$\Omega$

and points

![]() $x_k$

in

$x_k$

in

![]() $T_k$

with

$T_k$

with

![]() $d_{\Omega }(x_k,\partial T_k)\gt k$

. As above, after applying elements of

$d_{\Omega }(x_k,\partial T_k)\gt k$

. As above, after applying elements of

![]() $\Gamma$

, we may assume

$\Gamma$

, we may assume

![]() $T_k$

converges to a PET, so

$T_k$

converges to a PET, so

![]() $\Omega$

is not strictly convex.

$\Omega$

is not strictly convex.

It follows that in dimension

![]() $2$

either

$2$

either

![]() $\Omega$

is a triangle (and

$\Omega$

is a triangle (and

![]() $M$

is a torus or Klein bottle) or else is strictly convex. Using a basic fact from geometric group theory, it follows that a properly convex manifold (of any dimension) is strictly convex if and only if

$M$

is a torus or Klein bottle) or else is strictly convex. Using a basic fact from geometric group theory, it follows that a properly convex manifold (of any dimension) is strictly convex if and only if

![]() $\pi _1M$

has thin triangles. This is an algebraic characterization of strictly convex. However, we will give a direct geometric argument.

$\pi _1M$

has thin triangles. This is an algebraic characterization of strictly convex. However, we will give a direct geometric argument.

Given

![]() $K\geqslant 1$

and

$K\geqslant 1$

and

![]() $L\geqslant 0$

, a

$L\geqslant 0$

, a

![]() $(K,L)$

-quasi-isometric embedding is a map

$(K,L)$

-quasi-isometric embedding is a map

![]() $f:X\to Y$

between metric spaces

$f:X\to Y$

between metric spaces

![]() $(X,d_X)$

and

$(X,d_X)$

and

![]() $(Y,d_Y)$

such that

$(Y,d_Y)$

such that

for all

![]() $x,x^{\prime}\in X.$

If

$x,x^{\prime}\in X.$

If

![]() $X=[a,b]\subset {\mathbb{R}}$

, then

$X=[a,b]\subset {\mathbb{R}}$

, then

![]() $f$

is a quasi-geodesic. The map

$f$

is a quasi-geodesic. The map

![]() $f$

is a quasi-isometry, or QI, if also

$f$

is a quasi-isometry, or QI, if also

![]() $Y\subset N(fX,L)$

.

$Y\subset N(fX,L)$

.

If

![]() $g:Y\to Z$

is a

$g:Y\to Z$

is a

![]() $(K^{\prime},L^{\prime})$

-QI, then

$(K^{\prime},L^{\prime})$

-QI, then

![]() $g\circ f$

is a

$g\circ f$

is a

![]() $(KK^{\prime},K^{\prime}L+L^{\prime})$

-QI. In particular, if

$(KK^{\prime},K^{\prime}L+L^{\prime})$

-QI. In particular, if

![]() $g$

is a QI and

$g$

is a QI and

![]() $f$

is a quasi-geodesic, then

$f$

is a quasi-geodesic, then

![]() $g\circ f$

is a quasi-geodesic with QI constants that only depend on those of

$g\circ f$

is a quasi-geodesic with QI constants that only depend on those of

![]() $f$

and

$f$

and

![]() $g$

.

$g$

.

If

![]() $G$

is a finitely generated group, then a choice of finite generating set gives a word metric on

$G$

is a finitely generated group, then a choice of finite generating set gives a word metric on

![]() $G$

. A different choice of generating set gives a bi-Lipschitz equivalent metric. The Švarc–Milnor lemma in this setting is

$G$

. A different choice of generating set gives a bi-Lipschitz equivalent metric. The Švarc–Milnor lemma in this setting is

Proposition 1.8.

If

![]() $M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a closed and properly convex manifold, then

$M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a closed and properly convex manifold, then

![]() $(\Omega ,d_{\Omega })$

is QI to

$(\Omega ,d_{\Omega })$

is QI to

![]() $\pi _1M$

.

$\pi _1M$

.

Proof.

Fix

![]() $x\in \widetilde M=\Omega$

. Then

$x\in \widetilde M=\Omega$

. Then

![]() $f:\pi _1M\rightarrow \widetilde M$

given by

$f:\pi _1M\rightarrow \widetilde M$

given by

![]() $f(g)=\tau _g(x)$

is a QI.

$f(g)=\tau _g(x)$

is a QI.

A metric space

![]() $(Y,d_Y)$

is ML if it satisfies the Morse Lemma, i.e. for all

$(Y,d_Y)$

is ML if it satisfies the Morse Lemma, i.e. for all

![]() $(K,L)$

there is

$(K,L)$

there is

![]() $S=S(K,L)\gt 0$

, called a tracking constant, such that if

$S=S(K,L)\gt 0$

, called a tracking constant, such that if

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $\beta$

are

$\beta$

are

![]() $(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesics in

$(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesics in

![]() $Y$

with the same endpoints, then

$Y$

with the same endpoints, then

![]() $\alpha \subset N_{S}(\beta )$

and

$\alpha \subset N_{S}(\beta )$

and

![]() $\beta \subset N_{S}(\alpha )$

. Since quasi-geodesics are sent to quasi-geodesics by quasi-isometries, it follows that the property of ML is preserved by QI.

$\beta \subset N_{S}(\alpha )$

. Since quasi-geodesics are sent to quasi-geodesics by quasi-isometries, it follows that the property of ML is preserved by QI.

Clearly

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^2$

is not ML, and any norm on

${\mathbb{R}}^2$

is not ML, and any norm on

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^2$

is QI to the standard norm, so

${\mathbb{R}}^2$

is QI to the standard norm, so

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^2$

with any norm is not ML. A geodesic in the Cayley graph of

${\mathbb{R}}^2$

with any norm is not ML. A geodesic in the Cayley graph of

![]() $G$

picks out a sequence in

$G$

picks out a sequence in

![]() $G$

that is a quasi-geodesic. It follows from (1.8) that whether or not a closed properly convex manifold is ML only depends on

$G$

that is a quasi-geodesic. It follows from (1.8) that whether or not a closed properly convex manifold is ML only depends on

![]() $\pi _1M$

.

$\pi _1M$

.

Proposition 1.9.

If

![]() $M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a properly convex closed manifold, then

$M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a properly convex closed manifold, then

![]() $M$

is strictly convex if and only if

$M$

is strictly convex if and only if

![]() $(\Omega ,d_{\Omega })$

is ML.

$(\Omega ,d_{\Omega })$

is ML.

Proof.

If

![]() $\Omega$

is not strictly convex, then by (1.7) it contains a PET

$\Omega$

is not strictly convex, then by (1.7) it contains a PET

![]() $\Delta$

. The metric

$\Delta$

. The metric

![]() $d_{\Omega }$

restricted to

$d_{\Omega }$

restricted to

![]() $\Delta$

is isometric to a norm on

$\Delta$

is isometric to a norm on

![]() ${\mathbb{R}}^2$

. Hence,

${\mathbb{R}}^2$

. Hence,

![]() $(\Omega ,d_{\Omega })$

is not ML.

$(\Omega ,d_{\Omega })$

is not ML.

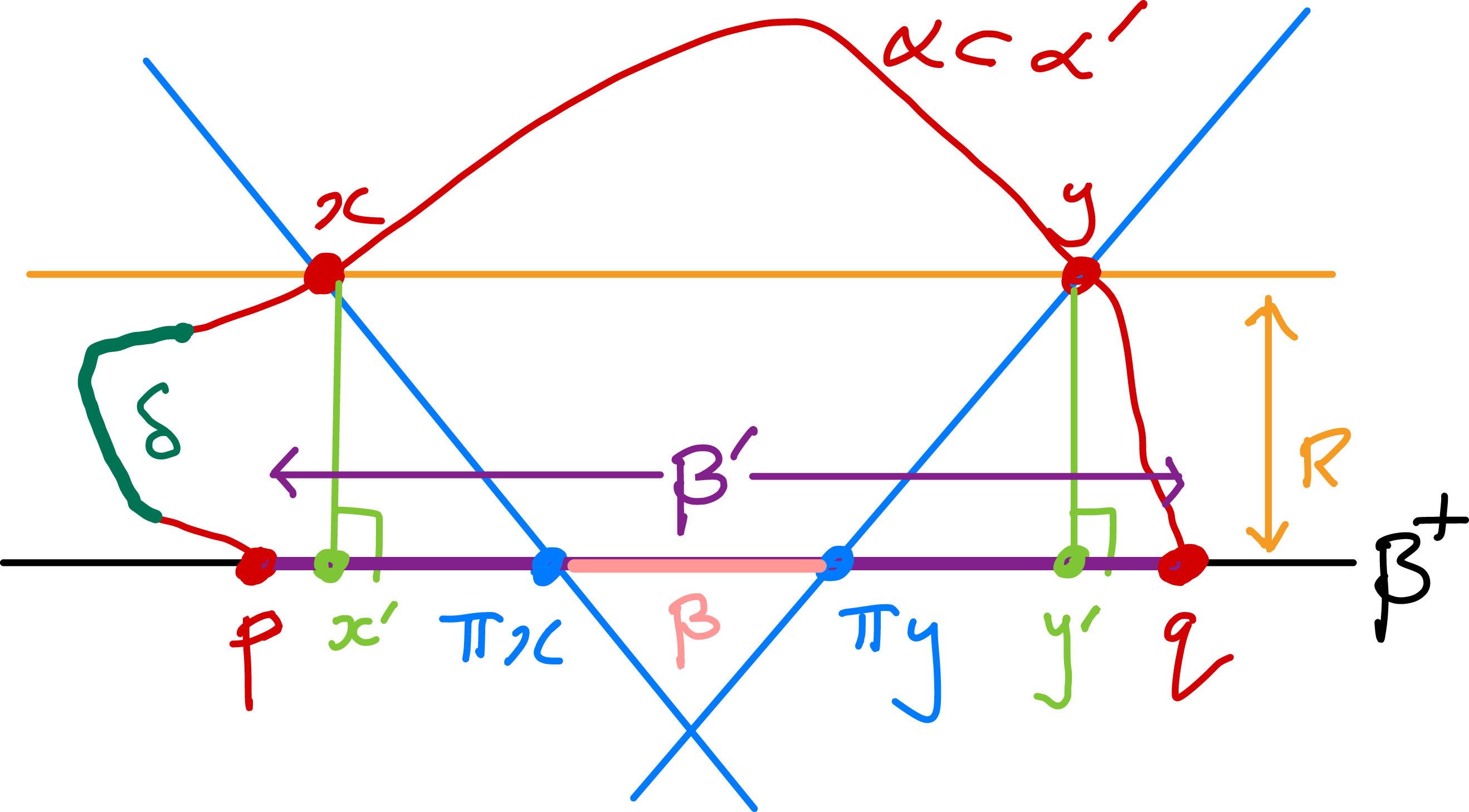

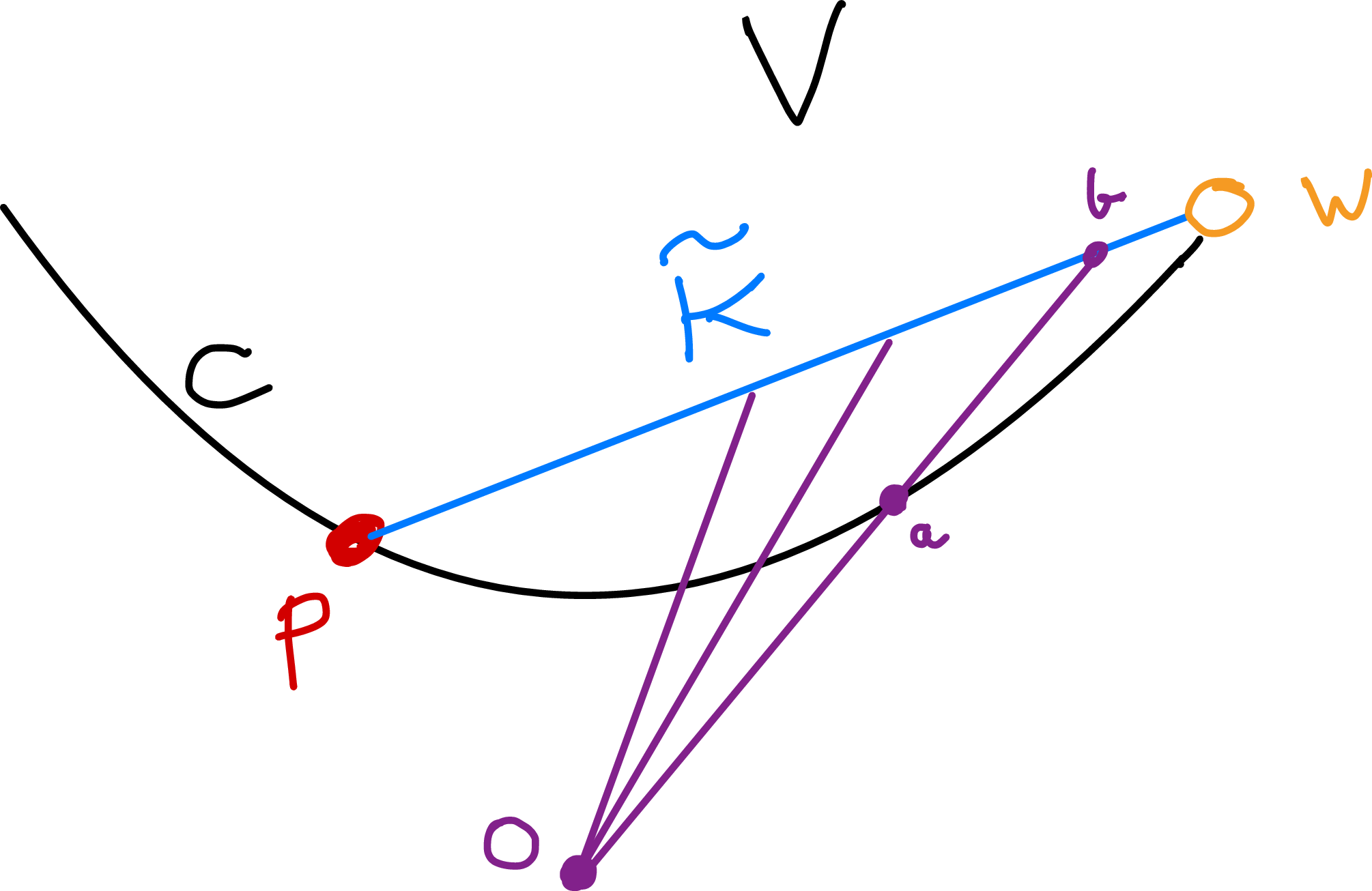

Figure 3. Quasi-geodesics.

Now suppose

![]() $\Omega$

is strictly convex. A quasi-geodesic is nice if the image consists of finitely many line segments and each line segment is parameterized by arc length. Every

$\Omega$

is strictly convex. A quasi-geodesic is nice if the image consists of finitely many line segments and each line segment is parameterized by arc length. Every

![]() $(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesic

$(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesic

![]() $\alpha$

in

$\alpha$

in

![]() $\Omega$

is approximated by a nice

$\Omega$

is approximated by a nice

![]() $(K^{\prime},L^{\prime})$

-quasi-geodesic

$(K^{\prime},L^{\prime})$

-quasi-geodesic

![]() $\overline {\alpha }$

in the sense that

$\overline {\alpha }$

in the sense that

![]() $\alpha \subset N(\overline {\alpha },D)$

and

$\alpha \subset N(\overline {\alpha },D)$

and

![]() $\overline {\alpha }\subset N(\alpha ,D)$

and

$\overline {\alpha }\subset N(\alpha ,D)$

and

![]() $(D, K^{\prime},L^{\prime})$

only depends on

$(D, K^{\prime},L^{\prime})$

only depends on

![]() $(K,L)$

. Thus it suffices to prove there is a tracking constant for nice quasi-geodesics.

$(K,L)$

. Thus it suffices to prove there is a tracking constant for nice quasi-geodesics.

Refer to Figure 3. Let

![]() $\alpha ^{\prime}$

be a nice

$\alpha ^{\prime}$

be a nice

![]() $(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesic with endpoints

$(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesic with endpoints

![]() $p$

and

$p$

and

![]() $q$

. Let

$q$

. Let

![]() $\beta ^{\prime}$

be the line segment with the same endpoints as

$\beta ^{\prime}$

be the line segment with the same endpoints as

![]() $\alpha ^{\prime}$

. Let

$\alpha ^{\prime}$

. Let

![]() $R=R(2K)$

be given by (1.6) and set

$R=R(2K)$

be given by (1.6) and set

![]() $S^{\prime}=R+4RK+K+L$

. We show that

$S^{\prime}=R+4RK+K+L$

. We show that

![]() $S=2KS^{\prime}+2L+2S^{\prime}$

is a tracking constant. Let

$S=2KS^{\prime}+2L+2S^{\prime}$

is a tracking constant. Let

![]() $\beta ^+$

be the geodesic in

$\beta ^+$

be the geodesic in

![]() $\Omega$

that contains

$\Omega$

that contains

![]() $\beta ^{\prime}$

and

$\beta ^{\prime}$

and

![]() $\pi :\Omega \rightarrow \beta ^+$

be a projection.

$\pi :\Omega \rightarrow \beta ^+$

be a projection.

Claim 1:

![]() $\alpha ^{\prime}\subset N(\beta ^+,S^{\prime})$

.

$\alpha ^{\prime}\subset N(\beta ^+,S^{\prime})$

.

Claim 2:

![]() $\alpha ^{\prime}\subset N(\beta ^{\prime},S/2)$

and

$\alpha ^{\prime}\subset N(\beta ^{\prime},S/2)$

and

![]() $\beta ^{\prime}\subset N(\alpha ^{\prime},S/2)$

.

$\beta ^{\prime}\subset N(\alpha ^{\prime},S/2)$

.

Assuming the claims, if

![]() $\gamma ^{\prime}$

is another nice

$\gamma ^{\prime}$

is another nice

![]() $(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesic with endpoints

$(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesic with endpoints

![]() $p$

and

$p$

and

![]() $q$

, then

$q$

, then

which proves that

![]() $S$

is a tracking constant. Hence,

$S$

is a tracking constant. Hence,

![]() $(\Omega ,d_{\Omega })$

is ML.

$(\Omega ,d_{\Omega })$

is ML.

For Claim 1, suppose that

![]() $\alpha$

is the closure of a component of

$\alpha$

is the closure of a component of

![]() $\alpha ^{\prime}\setminus N(\beta ^+,R)$

. The endpoints

$\alpha ^{\prime}\setminus N(\beta ^+,R)$

. The endpoints

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $y$

of

$y$

of

![]() $\alpha$

satisfy

$\alpha$

satisfy

![]() $d(x,\beta ^+)=d(y,\beta ^+)=R$

. Let

$d(x,\beta ^+)=d(y,\beta ^+)=R$

. Let

![]() $x^{\prime},y^{\prime}\in \beta ^+$

be chosen so that

$x^{\prime},y^{\prime}\in \beta ^+$

be chosen so that

![]() $d(x,x^{\prime})=R=d(y,y^{\prime})$

and let

$d(x,x^{\prime})=R=d(y,y^{\prime})$

and let

![]() $\beta =[\pi x,\pi y]\subset \beta ^+$

. By (1.6),

$\beta =[\pi x,\pi y]\subset \beta ^+$

. By (1.6),

by definition of

![]() $R$

. Since

$R$

. Since

![]() $\pi$

is distance non-increasing

$\pi$

is distance non-increasing

![]() $d(x^{\prime},\pi x)=d(\pi x^{\prime},\pi x)\leqslant d(x^{\prime}, x)=R$

, and similarly

$d(x^{\prime},\pi x)=d(\pi x^{\prime},\pi x)\leqslant d(x^{\prime}, x)=R$

, and similarly

![]() $d(y^{\prime},\pi y)\leqslant R$

. Thus

$d(y^{\prime},\pi y)\leqslant R$

. Thus

Since

![]() $\alpha$

is parametrized by arc length, the domain of

$\alpha$

is parametrized by arc length, the domain of

![]() $\alpha$

is

$\alpha$

is

![]() ${\textrm {length}}(\alpha )$

, Since

${\textrm {length}}(\alpha )$

, Since

![]() $\alpha$

is a

$\alpha$

is a

![]() $(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesic, we have

$(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesic, we have

\begin{equation*}\begin{array}{lrcl} & K^{-1}({\textrm {length}}(\alpha )-L)& \leqslant & d(x,y)\\ \Rightarrow & {\textrm {length}}(\alpha ) &\leqslant & K\cdot d(x,y)+L \\ & & \leqslant & K(4R +{\textrm {length}}(\beta ))+L\\ & & \leqslant & K(4R+1+{\textrm {length}}(\alpha )/2K)+L\\ & & = &4RK+K+L+{\textrm {length}}(\alpha )/2\\ \Rightarrow & (1/2){\textrm {length}}(\alpha )&\leqslant & 4RK+K+L. \end{array}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\begin{array}{lrcl} & K^{-1}({\textrm {length}}(\alpha )-L)& \leqslant & d(x,y)\\ \Rightarrow & {\textrm {length}}(\alpha ) &\leqslant & K\cdot d(x,y)+L \\ & & \leqslant & K(4R +{\textrm {length}}(\beta ))+L\\ & & \leqslant & K(4R+1+{\textrm {length}}(\alpha )/2K)+L\\ & & = &4RK+K+L+{\textrm {length}}(\alpha )/2\\ \Rightarrow & (1/2){\textrm {length}}(\alpha )&\leqslant & 4RK+K+L. \end{array}\end{equation*}

Since the endpoints of

![]() $\alpha$

are in

$\alpha$

are in

![]() $N(\beta ^+,R)$

, it follows that

$N(\beta ^+,R)$

, it follows that

Now

This proves Claim 1.

For Claim 2, let

![]() $\Pi :\alpha ^{\prime}\rightarrow \beta ^+$

be the nearest point retraction. This map is continuous, and

$\Pi :\alpha ^{\prime}\rightarrow \beta ^+$

be the nearest point retraction. This map is continuous, and

![]() $p,q$

are both in the image, so the image of

$p,q$

are both in the image, so the image of

![]() $\Pi \circ \alpha ^{\prime}$

contains

$\Pi \circ \alpha ^{\prime}$

contains

![]() $\beta ^{\prime}$

. If

$\beta ^{\prime}$

. If

![]() $x^{\prime}\in \beta ^{\prime}$

there is

$x^{\prime}\in \beta ^{\prime}$

there is

![]() $y^{\prime}\in \alpha ^{\prime}$

with

$y^{\prime}\in \alpha ^{\prime}$

with

![]() $\Pi y^{\prime}=x^{\prime}$

. Then

$\Pi y^{\prime}=x^{\prime}$

. Then

![]() $d(\beta ^+,y^{\prime})=d(x^{\prime},y^{\prime})$

, and by Claim 1

$d(\beta ^+,y^{\prime})=d(x^{\prime},y^{\prime})$

, and by Claim 1

![]() $d(\beta ^+,y^{\prime})\leqslant S^{\prime}$

so

$d(\beta ^+,y^{\prime})\leqslant S^{\prime}$

so

![]() $d(x^{\prime},y^{\prime})\leqslant S^{\prime}$

thus

$d(x^{\prime},y^{\prime})\leqslant S^{\prime}$

thus

Let

![]() $\delta \subset \alpha ^{\prime}$

be the closure of a component of

$\delta \subset \alpha ^{\prime}$

be the closure of a component of

![]() $\alpha ^{\prime}\setminus \eta$

, thus

$\alpha ^{\prime}\setminus \eta$

, thus

![]() $\delta$

is an arc in the interior of

$\delta$

is an arc in the interior of

![]() $\alpha ^{\prime}$

. Let

$\alpha ^{\prime}$

. Let

![]() $r,s$

be the endpoints of

$r,s$

be the endpoints of

![]() $\delta$

. Then

$\delta$

. Then

![]() $\Pi (r)=\Pi (s)\in \{p,q\}$

. By Claim 1,

$\Pi (r)=\Pi (s)\in \{p,q\}$

. By Claim 1,

Since

![]() $\delta$

is a nice

$\delta$

is a nice

![]() $(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesic,

$(K,L)$

-quasi-geodesic,

By Claim 1, the endpoints of

![]() $\delta$

are distance at most

$\delta$

are distance at most

![]() $S^{\prime}$

from

$S^{\prime}$

from

![]() $\beta ^{\prime}$

so

$\beta ^{\prime}$

so

Since

![]() $\delta \cup \eta \subset N(\beta ^{\prime},S/2)$

it follows that

$\delta \cup \eta \subset N(\beta ^{\prime},S/2)$

it follows that

![]() $\alpha ^{\prime}\subset N(\beta ^{\prime},S/2)$

, proving Claim 2.

$\alpha ^{\prime}\subset N(\beta ^{\prime},S/2)$

, proving Claim 2.

In the proof of the Closed Theorem, we construct a properly convex manifold with the correct holonomy. In order to know this manifold is closed and strictly convex we use the pair of results (1.10) and (1.11). A properly convex manifold has contractible universal cover. Whitehead’s theorem (that a weak homotopy equivalence between CW complexes is a homotopy equivalence) implies that if

![]() $M$

and

$M$

and

![]() $M^{\prime}$

are properly convex and

$M^{\prime}$

are properly convex and

![]() $\pi _1M\cong \pi _1M^{\prime}$

, then

$\pi _1M\cong \pi _1M^{\prime}$

, then

![]() $M$

and

$M$

and

![]() $M^{\prime}$

are homotopy equivalent. This is key in the following result.

$M^{\prime}$

are homotopy equivalent. This is key in the following result.

Lemma 1.10.

Suppose

![]() $M$

and

$M$

and

![]() $M^{\prime}$

are properly convex manifolds and

$M^{\prime}$

are properly convex manifolds and

![]() $\pi _1M\cong \pi _1M^{\prime}$

. If

$\pi _1M\cong \pi _1M^{\prime}$

. If

![]() $M$

is closed, then

$M$

is closed, then

![]() $M^{\prime}$

is closed.

$M^{\prime}$

is closed.

Proof.

Let

![]() $\pi :\Omega \to M$

be the projection. This is the universal covering space of

$\pi :\Omega \to M$

be the projection. This is the universal covering space of

![]() $M$

, so

$M$

, so

![]() $M$

is a

$M$

is a

![]() $K(\pi _1M,1)$

. The same holds for

$K(\pi _1M,1)$

. The same holds for

![]() $M^{\prime}$

. Hence

$M^{\prime}$

. Hence

![]() $M$

and

$M$

and

![]() $M^{\prime}$

are homotopy equivalent. If

$M^{\prime}$

are homotopy equivalent. If

![]() $n=\dim M$

, then

$n=\dim M$

, then

![]() $M$

is closed if and only if

$M$

is closed if and only if

![]() $H_n(M;{\mathbb{Z}}_2)\cong {\mathbb{Z}}_2$

. Since homology is an invariant of homotopy type the result follows.

$H_n(M;{\mathbb{Z}}_2)\cong {\mathbb{Z}}_2$

. Since homology is an invariant of homotopy type the result follows.

Corollary 1.11.

Suppose

![]() $M$

and

$M$

and

![]() $N$

are closed and properly convex, and that

$N$

are closed and properly convex, and that

![]() $\pi _1M\cong \pi _1N$

. If

$\pi _1M\cong \pi _1N$

. If

![]() $M$

is strictly convex, then

$M$

is strictly convex, then

![]() $N$

is strictly convex.

$N$

is strictly convex.

Proof.

Since ML is preserved by QI, it follows from (1.9) and (1.8) that

![]() $M$

is strictly convex if and only if

$M$

is strictly convex if and only if

![]() $\pi _1M$

is ML, and this is determined by

$\pi _1M$

is ML, and this is determined by

![]() $\pi _1M$

.

$\pi _1M$

.

The remaining discussion in this sections comes logically after Section 2 since it depends on (2.6), but it fits better into the narrative here. We let the reader choose their preferred order.

The displacement distance of

![]() $\gamma \in {\textrm {Aut}}(\Omega )$

is

$\gamma \in {\textrm {Aut}}(\Omega )$

is

![]() $t(\gamma )=\inf \{d_{\Omega }(x,\gamma x): x\in \Omega \}$

. The element

$t(\gamma )=\inf \{d_{\Omega }(x,\gamma x): x\in \Omega \}$

. The element

![]() $\gamma$

is called hyperbolic if

$\gamma$

is called hyperbolic if

![]() $t(\gamma )\gt 0$

. It is elliptic if it fixes a point in

$t(\gamma )\gt 0$

. It is elliptic if it fixes a point in

![]() $\Omega$

and parabolic if it has no fixed point in

$\Omega$

and parabolic if it has no fixed point in

![]() $\Omega$

but

$\Omega$

but

![]() $t(\gamma )=0$

. By [Reference Cooper, Long and TillmannCLT15, Proposition 2.1] we have that

$t(\gamma )=0$

. By [Reference Cooper, Long and TillmannCLT15, Proposition 2.1] we have that

![]() $t(\gamma )=\log |\lambda /\mu |$

, where

$t(\gamma )=\log |\lambda /\mu |$

, where

![]() $\lambda$

and

$\lambda$

and

![]() $\mu$

are the eigenvalues of

$\mu$

are the eigenvalues of

![]() $t(\gamma )$

of largest and smallest modulus. We will not make use of elliptics or parabolics in this paper.

$t(\gamma )$

of largest and smallest modulus. We will not make use of elliptics or parabolics in this paper.

Lemma 1.12 (Hyperbolics). Suppose

![]() $\Omega \subset {\mathbb{P}} V$

and

$\Omega \subset {\mathbb{P}} V$

and

![]() $M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a strictly convex closed manifold and

$M=\Omega /\Gamma$

is a strictly convex closed manifold and

![]() $1\ne \gamma \in \Gamma$

. Then

$1\ne \gamma \in \Gamma$

. Then

![]() $\gamma$

is hyperbolic and there are

$\gamma$

is hyperbolic and there are

![]() $a_{\pm }\in \textrm {Fr}(\Omega )$

such that for all

$a_{\pm }\in \textrm {Fr}(\Omega )$

such that for all

![]() $x\in {\mathbb{P}} V\setminus (H_+\cup H_-)$

we have

$x\in {\mathbb{P}} V\setminus (H_+\cup H_-)$

we have

where

![]() $H_{\pm }$

is the supporting hyperplane to

$H_{\pm }$

is the supporting hyperplane to

![]() $\Omega$

at

$\Omega$

at

![]() $a_{\pm }$

.

$a_{\pm }$

.

Proof.

Since

![]() $M$

is compact, the Arzela–Ascoli Theorem implies there is a closed geodesic

$M$

is compact, the Arzela–Ascoli Theorem implies there is a closed geodesic

![]() $C$

in

$C$

in

![]() $M$

that is conjugate to

$M$

that is conjugate to

![]() $\gamma$

in

$\gamma$

in

![]() $\pi _1M$

and

$\pi _1M$

and

![]() $t(\gamma )={\textrm {length}}(C)\gt 0$

. Hence,

$t(\gamma )={\textrm {length}}(C)\gt 0$

. Hence,

![]() $\gamma$

is hyperbolic. By (1.3),

$\gamma$

is hyperbolic. By (1.3),

![]() $C$

is covered by a proper segment

$C$

is covered by a proper segment

![]() $\alpha =(a_-,a_+)$

in

$\alpha =(a_-,a_+)$

in

![]() $\Omega$

that is preserved by

$\Omega$

that is preserved by

![]() $\gamma$

. By (2.6),

$\gamma$

. By (2.6),

![]() $M$

is

$M$

is

![]() $C^1$

so there are unique supporting hyperplanes

$C^1$

so there are unique supporting hyperplanes

![]() $H_{\pm }$

to

$H_{\pm }$

to

![]() $\textrm {cl}\Omega$

that contain

$\textrm {cl}\Omega$

that contain

![]() $a_{\pm }$

, respectively. Then

$a_{\pm }$

, respectively. Then

![]() $Q=H_+\cap H_-$

is a codimension-2 subspace, and it is disjoint from

$Q=H_+\cap H_-$

is a codimension-2 subspace, and it is disjoint from

![]() $\Omega$

by strict convexity. Moreover

$\Omega$

by strict convexity. Moreover

![]() $Q$

is preserved by

$Q$

is preserved by

![]() $\gamma$

.

$\gamma$

.

The pencil of hyperplanes

![]() $\{H_t:t\in L\}$

in

$\{H_t:t\in L\}$

in

![]() ${\mathbb{P}} V$

that contain

${\mathbb{P}} V$

that contain

![]() $Q$

is dual to a line

$Q$

is dual to a line

![]() $L\subset {\mathbb{P}}(V^*)$

. Since the dual of

$L\subset {\mathbb{P}}(V^*)$

. Since the dual of

![]() $\gamma$

acts on

$\gamma$

acts on