I make it whole. This wholeness means that it has lost its power to hurt me; it gives me, perhaps because by doing so I take away the pain, a great delight to put the severed parts together.

V. Woolf, The Waves.

1 Three grades of local involvement

There is space and spatial regions.Footnote

1

There is the material world and material objects. Both space and the material world have mereological structure. The mereological structure of spatial regions is often taken to be well understood. It’s a model of classical extensional mereology.Footnote

2

By contrast, the mereology of material objects seems elusive. But material objects are located in space. What if we could use location to transfer, so to speak, the mereological structure of regions to objects? One initially tempting thought is that the mereological structures of regions and objects perfectly mirror each other. They are in complete and perfect harmony. Unsurprisingly, this is known in the literature as Mereological Harmony.Footnote

3

Mereological Harmony is but one example of how the logic of parthood and composition and the logic of location might interact.Footnote

4

We shall see examples of harmony principles throughout the paper, but as of now I want to distinguish three grades of local involvement, three ways in which locative notions play a somewhat substantive role in the mereology of objects. Abusing terminology, I will use “spatial mereology” and “material mereology” to refer to the mereology of space and the material world respectively. Let me stipulate that, e.g., a claim (principle,

![]() $\ldots $

) is a purely mereological claim (principle,

$\ldots $

) is a purely mereological claim (principle,

![]() $\ldots $

) iff it contains only mereological (and logical) vocabulary, and that a claim (principle,

$\ldots $

) iff it contains only mereological (and logical) vocabulary, and that a claim (principle,

![]() $\ldots $

) is mereo-locational iff it contains mereological and locational (and logical) vocabulary. This might be somewhat vague but it is enough for our (initial) purposes. Then we can distinguish at least three grades of local involvement:Footnote

5

$\ldots $

) is mereo-locational iff it contains mereological and locational (and logical) vocabulary. This might be somewhat vague but it is enough for our (initial) purposes. Then we can distinguish at least three grades of local involvement:Footnote

5

-

First grade of local involvement: the use of spatial mereology and location to define notions of material mereology.

-

Second grade of local involvement: the use of spatial mereology and location to provide substantive mereo-locational answers to questions about material mereology.

-

Third grade of local involvement: the use of location and locational principles to provide purely mereological answers to questions about material mereology.Footnote 6

A few examples might help. These examples are not chosen randomly. They will keep us occupied for the rest of the paper. Arguably, the most debated example of First Grade is the so-called subregion theory of parthood.Footnote 7 This is roughly the following view:

-

Subregion Theory of Parthood: For any material object x and y, x is part of y iff the location of x is part of the location of y.

But it is not the only example. Cartwright, in his classic paper on scattered objects,Footnote 8 suggests the following definition of fusion for material objects:

-

Locative Fusion: For any material object x and set of material objects M, x fuses M iff “the region occupied by x is the smallest receptacle [i.e., location] that includes the receptacles occupied by the members of M” [Reference Cartwright and Lehrer7, p. 161].

And the literature on mereological harmony can be mined for other illustrative examples, as we shall see in due course. As for the second and third grades of involvement, it is instructive to recall the infamous special composition question.Footnote 9 One of its (many) formulations asks what are the necessary and sufficient conditions for material objects to compose.Footnote 10 Recently a particular answer has attracted significant attention. Said answer is known as Regionalism:

-

Regionalism: Some material objects compose iff there is something located at the fusion of the regions at which the objects are located.

Even in this vague formulation, it should be clear that regionalism counts as a mereo-locational claim. It is a claim which crucially involves both mereological and locational vocabulary. As I said, regionalism is advertised as an answer to the special composition question, a paradigmatic question of material mereology, if any.Footnote 11 In the light of this, it seems a clear example of Second Grade.Footnote 12 By contrast, consider the following purely mereological answer to the special composition question:

-

Underlap: Some material objects compose iff there is something of which they are all parts.

Underlap is a purely mereological claim, in that it contains only mereological (and logical) vocabulary. An example of Third Grade would then be an example of a locational principle that entails Underlap. Once again: I did not choose these examples on a whim. I will argue that there is one such locational principle, the so-called Arbitrary Partition principle. This is, I contend, a substantive result on its own. In effect, once the distinction between different grades of local involvement is in place, a natural question arises. Suppose one endorses a “first grade thesis”—to abuse terminology once more. Does this force any second or third grade theses? The rest of the paper explores particular instances of this general question. In doing so not only it provides a critical assessment of some recent results in the literature, but it also proves new substantive (and surprising) ones along the way. All this sheds new light on the relations between the logic of parthood and composition and the logic of location.

Let me be upfront. I intend neither to defend nor to endorse any of the mereological and locational principles used in the arguments below. Gilmore and Leonard, in their recent discussion of Regionalism, write: “Our goal is to chart connections, not to proselytize” [Reference Gilmore and Leonard12, p. 172]. I have the same goal.

2 Formal framework

Let me then be explicit about the formal framework I will be using in the rest of the paper. This is basically the framework used in Gilmore and Leonard [Reference Gilmore and Leonard12]—with minor alterations. This is mostly for pragmatic reasons. The next section provides a critical assessment of some of their results about regionalism. It’s therefore easier to stick to their formalism as closely as possible. To that end, I will work with first order plural logic with (plural) identity, together with the definite description operator

![]() $\iota $

. Single signs such as x, o, and r stand for singular terms (constants and variables), whereas double signs such as

$\iota $

. Single signs such as x, o, and r stand for singular terms (constants and variables), whereas double signs such as

![]() $xx$

,

$xx$

,

![]() $oo$

and

$oo$

and

![]() $rr$

stand for plural ones. To this we add a few special predicates. The first three such predicates are the plural logic predicate “being one of” (

$rr$

stand for plural ones. To this we add a few special predicates. The first three such predicates are the plural logic predicate “being one of” (

![]() $\prec $

, as in “x is one of the

$\prec $

, as in “x is one of the

![]() $xx$

”), the mereological predicate “parthood” (

$xx$

”), the mereological predicate “parthood” (

![]() $\leq $

, as in “x is part of y”), and the locative predicate “exact location” (

$\leq $

, as in “x is part of y”), and the locative predicate “exact location” (

![]() $@$

, as in “x is exactly located at y”). Then there are two other special predicates, M for “being a material object,” and R for “being a spatial region.” Starting from the first special predicate. Standard plural logic with (i) no empty plurality, (ii) extensionality, and (iii) comprehension axioms is assumed throughout. As for the other two, I will discuss some mereological and locational details at length. As of now, we simply need to recall orthodox mereological definitions: (i) x is an extension of y (

$@$

, as in “x is exactly located at y”). Then there are two other special predicates, M for “being a material object,” and R for “being a spatial region.” Starting from the first special predicate. Standard plural logic with (i) no empty plurality, (ii) extensionality, and (iii) comprehension axioms is assumed throughout. As for the other two, I will discuss some mereological and locational details at length. As of now, we simply need to recall orthodox mereological definitions: (i) x is an extension of y (

![]() $\geq $

) iff y is part of x, (ii) x is a proper part of y (

$\geq $

) iff y is part of x, (ii) x is a proper part of y (

![]() $\ll $

) iff it is a distinct part of y, (iii) x and y overlap (

$\ll $

) iff it is a distinct part of y, (iii) x and y overlap (

![]() $\circ $

) iff they share a part, and (iv) x and y are disjoint iff they do not overlap. The attentive reader probably noticed I did not talk about mereological fusion. It is well known that there are many inequivalent notions of fusion. Cotnoir and Varzi [Reference Cotnoir and Varzi10] distinguish three of them. Calosi and Giordani [Reference Calosi and Giordani4, Reference Calosi and Giordani5] go even further and distinguish four. These differences will play a crucial role later on. At this stage it is worth recalling one particular definition. From now on, for the sake of readability, let “

$\circ $

) iff they share a part, and (iv) x and y are disjoint iff they do not overlap. The attentive reader probably noticed I did not talk about mereological fusion. It is well known that there are many inequivalent notions of fusion. Cotnoir and Varzi [Reference Cotnoir and Varzi10] distinguish three of them. Calosi and Giordani [Reference Calosi and Giordani4, Reference Calosi and Giordani5] go even further and distinguish four. These differences will play a crucial role later on. At this stage it is worth recalling one particular definition. From now on, for the sake of readability, let “

![]() $xx \leq y $

” abbreviate “

$xx \leq y $

” abbreviate “

![]() $\forall x (x \prec xx \rightarrow x \leq y)$

,” and “

$\forall x (x \prec xx \rightarrow x \leq y)$

,” and “

![]() $x \circ xx$

” abbreviate “

$x \circ xx$

” abbreviate “

![]() $\exists y (y \prec xx \wedge x \circ y)$

.” Then:

$\exists y (y \prec xx \wedge x \circ y)$

.” Then:

-

(D.1)

$ F_1 (y, xx) \equiv _{\text {df}} xx \leq y \wedge \forall x (x \leq y \rightarrow x \circ xx).$

Fusion1

$ F_1 (y, xx) \equiv _{\text {df}} xx \leq y \wedge \forall x (x \leq y \rightarrow x \circ xx).$

Fusion1

As for location, I assume that

![]() $@$

is a total injective function from M to R.Footnote

13

We can thus assign to each material object M its unique exact location via:

$@$

is a total injective function from M to R.Footnote

13

We can thus assign to each material object M its unique exact location via:

-

(D.2)

$\ell (x) \equiv _{\text {df}} \iota y (x@y).$

Exact Location of x

$\ell (x) \equiv _{\text {df}} \iota y (x@y).$

Exact Location of x

Similarly for

![]() $xx$

, that is,

$xx$

, that is,

![]() $\ell \ell (xx)$

stands for the exact locations of the

$\ell \ell (xx)$

stands for the exact locations of the

![]() $xx$

. Besides these principles I assume that (i) everything is either a material object M or a region R; (ii) only objects are located at regions; (iii) both M and R are closed under parthood and fusions, i.e., parts and fusions of M are M—ditto for R; and (iv) regions are a model of classical extensional mereology, whereas material objects are a model of the extensional mereology EM. That is,

$xx$

. Besides these principles I assume that (i) everything is either a material object M or a region R; (ii) only objects are located at regions; (iii) both M and R are closed under parthood and fusions, i.e., parts and fusions of M are M—ditto for R; and (iv) regions are a model of classical extensional mereology, whereas material objects are a model of the extensional mereology EM. That is,

![]() $\leq $

is an extensional partial order. The difference between material and spatial mereology is that unrestricted composition holds for the latter. There is no fusion axiom for the former. A few words on two principles that will be used explicitly in the following proofs. The fact that

$\leq $

is an extensional partial order. The difference between material and spatial mereology is that unrestricted composition holds for the latter. There is no fusion axiom for the former. A few words on two principles that will be used explicitly in the following proofs. The fact that

![]() $\leq $

is extensional means that it obeys:

$\leq $

is extensional means that it obeys:

-

(P.1)

$\neg y \leq x \rightarrow \exists z (z \leq y \wedge \neg z \circ x).$

Strong Supplementation

$\neg y \leq x \rightarrow \exists z (z \leq y \wedge \neg z \circ x).$

Strong Supplementation

This yields that, when fusions exist, they are unique. The fact that

![]() $@$

is injective means that it obeys the following Anti-Colocation principle:

$@$

is injective means that it obeys the following Anti-Colocation principle:

-

(P.2)

$x@y \wedge z@y \rightarrow x = z.$

Anti-Colocation

Footnote

14

$x@y \wedge z@y \rightarrow x = z.$

Anti-Colocation

Footnote

14

3 From first to second grade: The debate over regionalism

3.1 Formulations

The recent debate over regionalism boils down to whether regionalism follows from the subregion theory of parthood. This is why the debate can be thought of as an illustration of the general question introduced in §1. It amounts to asking whether a first grade thesis (here: the subregion theory of parthood) entails a second grade thesis (here: regionalism).

Markosian [Reference Markosian and Kleinschmidt15] claims the answer is in the positive: the relevant entailment holds. Korman and Carmichael [Reference Korman and Carmichael13] agree.Footnote 15 Gilmore and Leonard [Reference Gilmore and Leonard12] recently challenged that conclusion. In the light of §2, the subregion theory of parthood translates into:Footnote 16

-

(P.3)

$ x \leq y \leftrightarrow \ell (x) \leq \ell (y).$

STP

$ x \leq y \leftrightarrow \ell (x) \leq \ell (y).$

STP

As for regionalism. Let me simplify the discussion if only slightly and take composition

![]() $_i$

to be the converse of fusion

$_i$

to be the converse of fusion

![]() $_i$

.Footnote

17

This is a simplification because one may take composition to be fusion by pairwise disjoint elements, as, e.g., Gilmore and Leonard do.Footnote

18

In which case it would be strictly stronger than composition as converse of fusion.Footnote

19

Let me then stipulate that “

$_i$

.Footnote

17

This is a simplification because one may take composition to be fusion by pairwise disjoint elements, as, e.g., Gilmore and Leonard do.Footnote

18

In which case it would be strictly stronger than composition as converse of fusion.Footnote

19

Let me then stipulate that “

![]() $C_1^{\exists } (xx)$

”—the

$C_1^{\exists } (xx)$

”—the

![]() $xx$

compose

$xx$

compose

![]() $_1$

—abbreviates “

$_1$

—abbreviates “

![]() $\exists y (F_1 (y, xx))$

,” and that “

$\exists y (F_1 (y, xx))$

,” and that “

![]() $@L_1(xx)$

”—some material object is located at something which is the fusion

$@L_1(xx)$

”—some material object is located at something which is the fusion

![]() $_1$

of the locations of the

$_1$

of the locations of the

![]() $xx$

—abbreviates “

$xx$

—abbreviates “

![]() $\exists y \exists z (M(y) \wedge R(z) \wedge F_1 (z, \ell\ell (xx)) \wedge y @z)$

.” Then regionalism can be formulated as follows:

$\exists y \exists z (M(y) \wedge R(z) \wedge F_1 (z, \ell\ell (xx)) \wedge y @z)$

.” Then regionalism can be formulated as follows:

-

(P.4)

$ C_1^\exists (xx) \leftrightarrow @L_1(xx).$

Regionalism1

$ C_1^\exists (xx) \leftrightarrow @L_1(xx).$

Regionalism1

That is to say, the

![]() $xx$

compose iff a material object is exactly located at the fusion of the

$xx$

compose iff a material object is exactly located at the fusion of the

![]() $xx$

’s exact locations, as desired.Footnote

20

$xx$

’s exact locations, as desired.Footnote

20

The general argument is that Regionalism1 does not follow from STP—not even in the presence of the substantive assumptions in §2. The following countermodels—where I used o-terms for objects and r-terms for regions for the sake of readability—show as much.

3.2 First countermodel

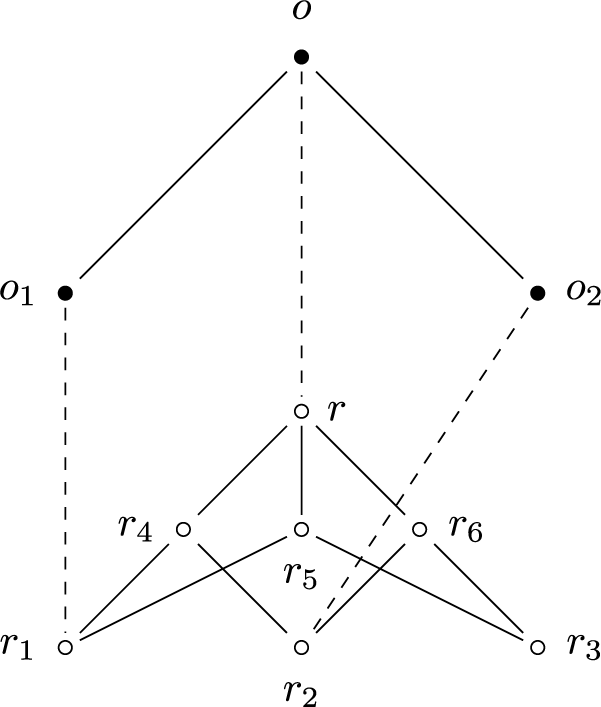

The first countermodel is presented in Figure 1. Full lines represent proper parthood (going uphill) and dashed lines represent exact locations (going downhill):

Figure 1 Countermodel 1.

The argument is as follows. In Figure 1 the subregion theory of parthood is satisfied but regionalism is not, thus undermining the relevant entailment. To see this, note that r is the

![]() $F_1$

of

$F_1$

of

![]() $r_1$

and

$r_1$

and

![]() $r_2$

, but

$r_2$

, but

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

do not have an

$o_2$

do not have an

![]() $F_1$

and therefore do not compose anything. Given that o is exactly located at r, there is an object exactly located at the region composed by the regions at which

$F_1$

and therefore do not compose anything. Given that o is exactly located at r, there is an object exactly located at the region composed by the regions at which

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

are exactly located but

$o_2$

are exactly located but

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

do not compose, contra the right-to-left direction of Regionalism

$o_2$

do not compose, contra the right-to-left direction of Regionalism

![]() $_1$

.

$_1$

.

3.3 Second countermodel

The second countermodel is depicted in Figure 2:

Figure 2 Countermodel 2.

Similarly, in Figure 2, the subregion theory of parthood is satisfied but regionalism is not. Note that o is the

![]() $F_1$

of

$F_1$

of

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

.

$o_2$

.

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

are exactly located at

$o_2$

are exactly located at

![]() $r_1$

and

$r_1$

and

![]() $r_2$

, respectively. Furthermore,

$r_2$

, respectively. Furthermore,

![]() $r_4$

is the

$r_4$

is the

![]() $F_1$

of

$F_1$

of

![]() $r_1$

and

$r_1$

and

![]() $r_2$

. Thus,

$r_2$

. Thus,

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

compose but there is nothing exactly located at the region that is composed by their exact locations, contra the left-to-right direction of Regionalism

$o_2$

compose but there is nothing exactly located at the region that is composed by their exact locations, contra the left-to-right direction of Regionalism

![]() $_1$

.

$_1$

.

Gilmore and Leonard rightly note that the first countermodel violatesFootnote 21

-

(P.5)

$x \circ y \leftrightarrow \ell (x) \circ \ell (y)$

Overlap

$x \circ y \leftrightarrow \ell (x) \circ \ell (y)$

Overlap

whereas the second countermodel violatesFootnote 22

-

(P.6)

$C(x) \wedge x@y \rightarrow $

$C(x) \wedge x@y \rightarrow $

$\forall yy (F_1 (x, yy) \rightarrow $

$\forall yy (F_1 (x, yy) \rightarrow $

$\forall w (w \leq y \rightarrow \exists z \exists v (z \prec yy \wedge z @v \wedge w \circ v))) $

Strong Delegation

$\forall w (w \leq y \rightarrow \exists z \exists v (z \prec yy \wedge z @v \wedge w \circ v))) $

Strong Delegation

—where C stand for “being mereologically complex,” i.e.,

![]() $C(x) \equiv _{\text {df}} \exists y (y \ll x)$

. Overlap is another clear example of First Grade. In effect, it is often enlisted as a core principle in different formulations of mereological harmony. Strong Delegation looks complicated but the picture behind it is simple and reasonable enough.Footnote

23

It is supposed to capture the idea that complex objects fill their locations by “delegation,” that is, with the help of their proper parts (see Gilmore and Leonard [Reference Gilmore and Leonard12]). Interestingly, the second countermodel does not violate Overlap. Gilmore and Leonard go on to provide a new argument for the entailment between STP and Regionalism1

based on those principles. I simply refer to Gilmore and Leonard [Reference Gilmore and Leonard12] for the proof.

$C(x) \equiv _{\text {df}} \exists y (y \ll x)$

. Overlap is another clear example of First Grade. In effect, it is often enlisted as a core principle in different formulations of mereological harmony. Strong Delegation looks complicated but the picture behind it is simple and reasonable enough.Footnote

23

It is supposed to capture the idea that complex objects fill their locations by “delegation,” that is, with the help of their proper parts (see Gilmore and Leonard [Reference Gilmore and Leonard12]). Interestingly, the second countermodel does not violate Overlap. Gilmore and Leonard go on to provide a new argument for the entailment between STP and Regionalism1

based on those principles. I simply refer to Gilmore and Leonard [Reference Gilmore and Leonard12] for the proof.

3.4 An assessment

As I noted

![]() $F_1$

is not the only notion of fusion in the literature. For the purpose of the paper, let me introduce just another one:

$F_1$

is not the only notion of fusion in the literature. For the purpose of the paper, let me introduce just another one:

-

(D.3)

$F_2 (y, xx) \equiv _{\text {df}} xx \leq y \wedge \forall x (xx \leq x \rightarrow y \leq x).$

Fusion2

$F_2 (y, xx) \equiv _{\text {df}} xx \leq y \wedge \forall x (xx \leq x \rightarrow y \leq x).$

Fusion2

Roughly,

![]() $F_2$

corresponds to the algebraic notion of least upper bound. Gilmore and Leonard run their argument from Countermodel 1 with only one notion of composition, the one that uses (albeit implicitly)

$F_2$

corresponds to the algebraic notion of least upper bound. Gilmore and Leonard run their argument from Countermodel 1 with only one notion of composition, the one that uses (albeit implicitly)

![]() $F_1$

—as I did above. However, whilst it is true that in classical extensional mereology

$F_1$

—as I did above. However, whilst it is true that in classical extensional mereology

![]() $F_1$

and

$F_1$

and

![]() $F_2$

—and thus composition

$F_2$

—and thus composition

![]() $_1$

and composition

$_1$

and composition

![]() $_2$

—are equivalent, EM is not strong enough to deliver the result. This is best appreciated as follows. Figure 3 is a model of EM. Yet there are

$_2$

—are equivalent, EM is not strong enough to deliver the result. This is best appreciated as follows. Figure 3 is a model of EM. Yet there are

![]() $F_2$

that are not

$F_2$

that are not

![]() $F_1$

.

$F_1$

.

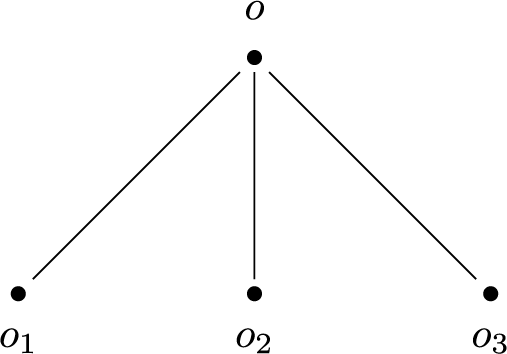

Figure 3 Model 3.

For instance, it is easily checked that

![]() $F_2(o, [o_1, o_2])$

holds but

$F_2(o, [o_1, o_2])$

holds but

![]() $F_1(o, [o_1, o_2])$

doesn’t—where

$F_1(o, [o_1, o_2])$

doesn’t—where

![]() $[o_1, o_2]$

represents the plurality

$[o_1, o_2]$

represents the plurality

![]() $oo$

whose sole members are

$oo$

whose sole members are

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

. In other words, o counts as the

$o_2$

. In other words, o counts as the

![]() $F_2$

of

$F_2$

of

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

but not as their

$o_2$

but not as their

![]() $F_1$

.Footnote

24

This might seem as an insignificant detail but it is not. This is because the “material object” part of Countermodel 1 just is Model 3. The reply to Gilmore and Leonard’s first argument on behalf of the regionalist can then be put in the form of a dilemma.

$F_1$

.Footnote

24

This might seem as an insignificant detail but it is not. This is because the “material object” part of Countermodel 1 just is Model 3. The reply to Gilmore and Leonard’s first argument on behalf of the regionalist can then be put in the form of a dilemma.

Either (i) one sticks to EM as the background mereology or (ii) one moves to a stronger mereology in which

![]() $F_1$

and

$F_1$

and

![]() $F_2$

are indeed equivalent. First horn first. If one sticks to EM, to resist the original argument, regionalists simply need to switch from

$F_2$

are indeed equivalent. First horn first. If one sticks to EM, to resist the original argument, regionalists simply need to switch from

![]() $F_1$

to

$F_1$

to

![]() $F_2$

in their formulation of regionalism. Let me elaborate. Let “

$F_2$

in their formulation of regionalism. Let me elaborate. Let “

![]() $C_2^{\exists } (xx)$

” abbreviate “

$C_2^{\exists } (xx)$

” abbreviate “

![]() $\exists y (F_2 (y, xx))$

,” and let “

$\exists y (F_2 (y, xx))$

,” and let “

![]() $@L_2(xx)$

” abbreviate “

$@L_2(xx)$

” abbreviate “

![]() $\exists y \exists z (M(y) \wedge R(z) \wedge F_2 (z, \ell\ell (xx)) \wedge y @z)$

.” Finally, claim that regionalism can be captured by:

$\exists y \exists z (M(y) \wedge R(z) \wedge F_2 (z, \ell\ell (xx)) \wedge y @z)$

.” Finally, claim that regionalism can be captured by:

-

(P.7)

$ C_2^\exists (xx) \leftrightarrow @L_2(xx).$

Regionalism2

$ C_2^\exists (xx) \leftrightarrow @L_2(xx).$

Regionalism2

The gist is that now the original argument does not go through. Look back at Countermodel 1. r is the

![]() $F_2$

of

$F_2$

of

![]() $r_1$

and

$r_1$

and

![]() $r_2$

and o is still exactly located at r. However, now

$r_2$

and o is still exactly located at r. However, now

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

compose

$o_2$

compose

![]() $_2\ o$

. Thus, Regionalism2

is not violated. Second horn then. If one takes the second horn one needs to change the mereology in such a way as to render

$_2\ o$

. Thus, Regionalism2

is not violated. Second horn then. If one takes the second horn one needs to change the mereology in such a way as to render

![]() $F_1$

and

$F_1$

and

![]() $F_2$

equivalent. But the argument in this section then establishes that one would therefore lose Countermodel 1.

$F_2$

equivalent. But the argument in this section then establishes that one would therefore lose Countermodel 1.

To be fair, two things are worth noticing. First,

![]() $F_1$

is arguably the most widely used—and some say well-behaved—notion of fusion. One should also note that there are dissenting voices (see, e.g., Calosi and Giordani [Reference Calosi and Giordani5]). Interestingly, the new notion of fusion Calosi and Giordani define can be used to run a counterpart of Gilmore and Leonard’s original argument. Second,

$F_1$

is arguably the most widely used—and some say well-behaved—notion of fusion. One should also note that there are dissenting voices (see, e.g., Calosi and Giordani [Reference Calosi and Giordani5]). Interestingly, the new notion of fusion Calosi and Giordani define can be used to run a counterpart of Gilmore and Leonard’s original argument. Second,

![]() $F_2$

is rarely used in the debates on “composition.” One reason is that it might fail to capture some of our pre-theoretical intuitions about composition. For instance, an

$F_2$

is rarely used in the debates on “composition.” One reason is that it might fail to capture some of our pre-theoretical intuitions about composition. For instance, an

![]() $F_2$

of the

$F_2$

of the

![]() $xx$

can have something that is completely disjoint from any of the

$xx$

can have something that is completely disjoint from any of the

![]() $xx$

as a part. One may also push the point that is also biased towards the existence of the so-called arbitrary undetached parts. And this is relevant, in this context, because of the relations between arbitrary parts and certain principles of location (see §4.3). Consider Countermodel 3. One may want to claim that something that is composed of

$xx$

as a part. One may also push the point that is also biased towards the existence of the so-called arbitrary undetached parts. And this is relevant, in this context, because of the relations between arbitrary parts and certain principles of location (see §4.3). Consider Countermodel 3. One may want to claim that something that is composed of

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

is an arbitrary undetached part of o. Given that the existence of such arbitrary parts is supposed to be controversial, one should not invoke a definition of composition that almost guarantees their existence. But, in the case at hand, such existence is guaranteed by

$o_2$

is an arbitrary undetached part of o. Given that the existence of such arbitrary parts is supposed to be controversial, one should not invoke a definition of composition that almost guarantees their existence. But, in the case at hand, such existence is guaranteed by

![]() $F_2$

, insofar as

$F_2$

, insofar as

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

compose o. Therein lies the problem. Or so the thought goes. Here is a possible response. An arbitrary undetached part x of y is supposed to be a proper part of y. And given that—as I pointed out already—an

$o_2$

compose o. Therein lies the problem. Or so the thought goes. Here is a possible response. An arbitrary undetached part x of y is supposed to be a proper part of y. And given that—as I pointed out already—an

![]() $F_2$

of the

$F_2$

of the

![]() $xx$

could have parts that are disjoint from the

$xx$

could have parts that are disjoint from the

![]() $xx$

, the fact that the

$xx$

, the fact that the

![]() $xx$

have an

$xx$

have an

![]() $F_2$

might be necessary, but is not sufficient to qualify their

$F_2$

might be necessary, but is not sufficient to qualify their

![]() $F_2$

as an arbitrary undetached part of y. Such

$F_2$

as an arbitrary undetached part of y. Such

![]() $F_2$

should be distinct from y. In the case of Model 3, the

$F_2$

should be distinct from y. In the case of Model 3, the

![]() $F_2$

of

$F_2$

of

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

thus fails to qualify as an arbitrary undetached part of o. More in general, the definition of

$o_2$

thus fails to qualify as an arbitrary undetached part of o. More in general, the definition of

![]() $F_2$

does not seem to guarantee by itself the existence of arbitrary undetached parts.Footnote

25

$F_2$

does not seem to guarantee by itself the existence of arbitrary undetached parts.Footnote

25

Whatever one thinks of the considerations above, the argument establishes that, contrary that what is assumed in the literature, the threat posed to regionalism by Countermodel 1 crucially depends on both very fine-grained details about the notion of fusion and the background mereology one works with. It also shows that the regionalist might have some leeway in both respects. The point can actually be strengthened. In §4.2 I will argue that one can prove the left-to-right direction of Regionalism2

in the presence of STP alone. Let me be clear. This does not detract from Gilmore and Leonard’s overall point. The argument from Countermodel 2 is still standing. But note that there seems to be a crucial difference between Countermodel 1 and Countermodel 2. As far as location is concerned Countermodel 1 does not seem problematic. The problem for regionalism stems from the fact that spatial mereology and material mereology are not aligned. In particular, material mereology is not a model of classical mereology, whereas spatial mereology is. By contrast, in Countermodel 2 location (rather than mereology) seems to be the source of the problem. In effect, both spatial and material mereology are models of classical mereology in Countermodel 2. What is problematic, intuitively, is that the composite object o extends further than its parts

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

. One may think that any theory of location should rule that locative pattern out, independently of the background mereology of space and objects. Thus, one may push the following argument. Any satisfactory theory of location should rule out Countermodel 2 along with it. And those who want regionalism to follow from the subregion theory of parthood can undermine the argument from Countermodel 1. So there is at least hope for that entailment to emerge unscathed from the previous arguments. Rather than pushing this line of argument I want focus on a theory of location that does in effect rule out Countermodel 2 thanks to a locative principle that is different from Strong Delegation—the reason will be clear shortly. In the present context this is particularly relevant as it offers new, substantive, and unexplored examples of the interaction between the first and third grades of local involvement. More in general, it sheds new light on the relations between the logic of parthood and the logic of location.

$o_2$

. One may think that any theory of location should rule that locative pattern out, independently of the background mereology of space and objects. Thus, one may push the following argument. Any satisfactory theory of location should rule out Countermodel 2 along with it. And those who want regionalism to follow from the subregion theory of parthood can undermine the argument from Countermodel 1. So there is at least hope for that entailment to emerge unscathed from the previous arguments. Rather than pushing this line of argument I want focus on a theory of location that does in effect rule out Countermodel 2 thanks to a locative principle that is different from Strong Delegation—the reason will be clear shortly. In the present context this is particularly relevant as it offers new, substantive, and unexplored examples of the interaction between the first and third grades of local involvement. More in general, it sheds new light on the relations between the logic of parthood and the logic of location.

3.5 Another argument

Interestingly, the logical relations between Locative Fusion and STP—the two examples of First Grade involvement I discussed in §1—provide another argument against the entailment between STP and Regionalism1 . In effect, they provide an argument against a particular direction of Regionalism1 , the left-to-right direction. That, as we shall see, is important. Suppose one defines (material) parthood in terms of fusion, using the standard definition of parthood for “fusion-first mereologies”:Footnote 26

-

(P.8)

$x \leq y \equiv _{\text {df}} F(y, [x,y]).$

Parthood

$x \leq y \equiv _{\text {df}} F(y, [x,y]).$

Parthood

And suppose one endorses Cartwrigth’s locative fusion. It follows that

![]() $\ell (y)$

has the exact locations of x and y as parts. Thus

$\ell (y)$

has the exact locations of x and y as parts. Thus

![]() $\ell (x) \leq \ell (y)$

. This yields that

$\ell (x) \leq \ell (y)$

. This yields that

![]() $x \leq y \rightarrow \ell (x) \leq \ell (y)$

. And

$x \leq y \rightarrow \ell (x) \leq \ell (y)$

. And

![]() $\ell (x) \leq \ell (y) \rightarrow x \leq y$

simply follows from Locative Fusion. This means that STP itself follows from Locative Fusion. Now for the argument. One may think that not every region of space(time) is eligible to be an exact location of a material object. For instance, three-dimensionalists should maintain that four-dimensional (spacetime) regions are not eligible exact locations for material objects. Say that a receptacle is a region of space that meets an eligibility requirement (E) to be an exact location for a material object:

$\ell (x) \leq \ell (y) \rightarrow x \leq y$

simply follows from Locative Fusion. This means that STP itself follows from Locative Fusion. Now for the argument. One may think that not every region of space(time) is eligible to be an exact location of a material object. For instance, three-dimensionalists should maintain that four-dimensional (spacetime) regions are not eligible exact locations for material objects. Say that a receptacle is a region of space that meets an eligibility requirement (E) to be an exact location for a material object:

-

(P.9)

$REC(x) \equiv _{\text {df}} R(x) \wedge E(x).$

Receptacle

$REC(x) \equiv _{\text {df}} R(x) \wedge E(x).$

Receptacle

There is no guarantee that

![]() $REC$

is closed under fusion. That is, there is no guarantee that the fusion of two receptacles is a receptacle. This crucially depends on the eligibility condition E. Cartwright’s own view of receptacles provides an example. Cartwright endorses the view that E is “being a non-null open domain,” that is, a region that is identical with the interior of its closure [Reference Cartwright and Lehrer7, p. 156]. And as he notes, an open sphere cut by a plane is a fusion of open domains (the open regions on both sides of the plane) that is not an open domain. This is important because, given that STP follows from Locative Fusion, those who endorse the latter are committed to STP. But the “eligibility” argument above—as I shall call it—shows that things might have a fusion—and thus compose—even if there is nothing that is exactly located at the fusion of the exact locations of their parts, contra the left-to-right direction of Regionalism1

. For the sake of illustration let me use Cartwright’s own example. Go back to the open sphere cut by a plane. Let

$REC$

is closed under fusion. That is, there is no guarantee that the fusion of two receptacles is a receptacle. This crucially depends on the eligibility condition E. Cartwright’s own view of receptacles provides an example. Cartwright endorses the view that E is “being a non-null open domain,” that is, a region that is identical with the interior of its closure [Reference Cartwright and Lehrer7, p. 156]. And as he notes, an open sphere cut by a plane is a fusion of open domains (the open regions on both sides of the plane) that is not an open domain. This is important because, given that STP follows from Locative Fusion, those who endorse the latter are committed to STP. But the “eligibility” argument above—as I shall call it—shows that things might have a fusion—and thus compose—even if there is nothing that is exactly located at the fusion of the exact locations of their parts, contra the left-to-right direction of Regionalism1

. For the sake of illustration let me use Cartwright’s own example. Go back to the open sphere cut by a plane. Let

![]() $o_l$

be the open region on the left of the plane and let

$o_l$

be the open region on the left of the plane and let

![]() $o_r$

be the open region on the right. And let

$o_r$

be the open region on the right. And let

![]() $x@o_l$

and

$x@o_l$

and

![]() $y@o_r$

. Nothing prevents x and y to have a fusion, say

$y@o_r$

. Nothing prevents x and y to have a fusion, say

![]() $z = x \oplus _1 y$

. z has an exact location that is not the fusion of the exact locations of its parts

$z = x \oplus _1 y$

. z has an exact location that is not the fusion of the exact locations of its parts

![]() $o_l \oplus _1 o_r$

, contra Regionalism1

. Therefore, regonalism cannot follow from STP alone. Something else needs to be added.Footnote

27

$o_l \oplus _1 o_r$

, contra Regionalism1

. Therefore, regonalism cannot follow from STP alone. Something else needs to be added.Footnote

27

4 From first to third grade: Partitions and least upper bounds

4.1 Partition and countermodels

Gilmore and Leonard rightly note that Countermodel 2 does not violate Overlap. Similarly, Countermodel 1 does not violate Strong Delegation. Hence they assume both principles in their new argument. They also rightly claim that another locative principle in the vicinity of Strong Delegation rules out Countermodel 2. This is Arbitrary Partition from Casati and Varzi [Reference Casati and Varzi6]. Informally, the principle says that an object has parts that are exactly located at every region it pervades (or fills—

![]() $x@_\geq y$

):Footnote

28

$x@_\geq y$

):Footnote

28

-

(P.10)

$ x@_\geq y \rightarrow \exists z (z \leq x \wedge z @ y)$

Arbitrary Partition

$ x@_\geq y \rightarrow \exists z (z \leq x \wedge z @ y)$

Arbitrary Partition

—where

![]() $x@_\geq y \equiv _{\text {df}} \exists z (x@z \wedge z \geq y)$

. Interestingly, Arbitrary Partition can be used to rule out both countermodels in one fell swoop. This is because in the presence of Arbitrary Partition, Overlap follows from STP. Overlap, remember, is the following biconditional:

$x@_\geq y \equiv _{\text {df}} \exists z (x@z \wedge z \geq y)$

. Interestingly, Arbitrary Partition can be used to rule out both countermodels in one fell swoop. This is because in the presence of Arbitrary Partition, Overlap follows from STP. Overlap, remember, is the following biconditional:

![]() $x \circ y \leftrightarrow \ell (x) \circ \ell (y)$

. The left-to-right direction of that biconditional follows directly from STP. Assume

$x \circ y \leftrightarrow \ell (x) \circ \ell (y)$

. The left-to-right direction of that biconditional follows directly from STP. Assume

![]() $x \circ y$

. Then there is a z such that

$x \circ y$

. Then there is a z such that

![]() $z \leq x$

and

$z \leq x$

and

![]() $z \leq y$

. By STP,

$z \leq y$

. By STP,

![]() $\ell (z) \leq \ell (x)$

and

$\ell (z) \leq \ell (x)$

and

![]() $\ell (z) \leq \ell (y)$

. Hence

$\ell (z) \leq \ell (y)$

. Hence

![]() $\ell (x) \circ \ell (y)$

. For the right-to-left, assume that

$\ell (x) \circ \ell (y)$

. For the right-to-left, assume that

![]() $\ell (x) \circ \ell (y)$

. Then, there is a region w such that w is part of both

$\ell (x) \circ \ell (y)$

. Then, there is a region w such that w is part of both

![]() $\ell (x)$

and

$\ell (x)$

and

![]() $\ell (y)$

. Arbitrary Partition now entails that there is a

$\ell (y)$

. Arbitrary Partition now entails that there is a

![]() $z_1$

such that

$z_1$

such that

![]() $z_1 \leq x$

and

$z_1 \leq x$

and

![]() $z_1@w$

. It also entails that there is a

$z_1@w$

. It also entails that there is a

![]() $z_2$

such that

$z_2$

such that

![]() $z_2 \leq y$

and

$z_2 \leq y$

and

![]() $z_2@w$

. It follows that

$z_2@w$

. It follows that

![]() $\ell (z_1) = \ell (z_2)$

, which in turn entails that

$\ell (z_1) = \ell (z_2)$

, which in turn entails that

![]() $\ell (z_1) \leq \ell (z_2)$

and

$\ell (z_1) \leq \ell (z_2)$

and

![]() $\ell (z_2) \leq \ell (z_1)$

. By STP

$\ell (z_2) \leq \ell (z_1)$

. By STP

![]() $z_1 \leq z_2$

and

$z_1 \leq z_2$

and

![]() $z_2 \leq z_1$

. But parthood is assumed to be a partial order and therefore anti-symmetric, which yields

$z_2 \leq z_1$

. But parthood is assumed to be a partial order and therefore anti-symmetric, which yields

![]() $z_1 = z_2$

. x and y then overlap as desired. We already noted that Arbitrary Partition rules out Countermodel 2. It now rules out Countermodel 1 as well, by implying Overlap.Footnote

29

$z_1 = z_2$

. x and y then overlap as desired. We already noted that Arbitrary Partition rules out Countermodel 2. It now rules out Countermodel 1 as well, by implying Overlap.Footnote

29

Interestingly enough, Anti-Colocation and Arbitrary Partition can be used to derive yet another mereological harmony principle that might appeal to those who endorse STP. For obvious reasons I shall call it the proper subregion theory of proper parthood (PSTP):

-

(P.11)

$x \ll y \leftrightarrow \ell (x) \ll \ell (y).$

PSTP

$x \ll y \leftrightarrow \ell (x) \ll \ell (y).$

PSTP

Suppose

![]() $x \ll y$

. Then

$x \ll y$

. Then

![]() $x \leq y$

and

$x \leq y$

and

![]() $x \neq y$

. By STP,

$x \neq y$

. By STP,

![]() $\ell (x) \leq \ell (y)$

. There are two possibilities. Either

$\ell (x) \leq \ell (y)$

. There are two possibilities. Either

![]() $\ell (x) = \ell (y)$

or

$\ell (x) = \ell (y)$

or

![]() $\ell (x) \ll \ell (y)$

. If

$\ell (x) \ll \ell (y)$

. If

![]() $\ell (x) = \ell (y)$

, then two distinct things are exactly located at

$\ell (x) = \ell (y)$

, then two distinct things are exactly located at

![]() $\ell (y)$

, namely, x and y, against Anti-Colocation. As for the other direction assume

$\ell (y)$

, namely, x and y, against Anti-Colocation. As for the other direction assume

![]() $\ell (x) \ll \ell (y)$

. Then

$\ell (x) \ll \ell (y)$

. Then

![]() $\ell (x) \leq \ell (y)$

and

$\ell (x) \leq \ell (y)$

and

![]() $\ell (x) \neq \ell (y)$

. By STP,

$\ell (x) \neq \ell (y)$

. By STP,

![]() $x \leq y$

. By Strong Supplementation,

$x \leq y$

. By Strong Supplementation,

![]() $\ell (y)$

has a part that is disjoint from

$\ell (y)$

has a part that is disjoint from

![]() $\ell (x)$

, call it w.Footnote

30

y pervades w, so Arbitrary Partition entails that there is a part of y, say z that is exactly located at w. By Overlap z is disjoint from x. Thus x and y do not have the same proper parts, and are therefore distinct. Hence

$\ell (x)$

, call it w.Footnote

30

y pervades w, so Arbitrary Partition entails that there is a part of y, say z that is exactly located at w. By Overlap z is disjoint from x. Thus x and y do not have the same proper parts, and are therefore distinct. Hence

![]() $x \ll y$

as desired.Footnote

31

$x \ll y$

as desired.Footnote

31

It should be clear that PSTP is an attractive principle by regionalist standards. Or better: it is attractive to those regionalists that want their regionalism to follow from STP. In effect, it should be how one cashes out the subregion theory of parthood if one takes

![]() $\ll $

as the mereological primitive. Now Arbitrary Partition is starting to look attractive, especially in the eyes of a regionalist. It (i) takes care of both the arguments from countermodels and (ii) it entails principles like Overlap and PSTP that are certainly in the same ballpark as STP. And it seems to get even better.

$\ll $

as the mereological primitive. Now Arbitrary Partition is starting to look attractive, especially in the eyes of a regionalist. It (i) takes care of both the arguments from countermodels and (ii) it entails principles like Overlap and PSTP that are certainly in the same ballpark as STP. And it seems to get even better.

4.2 Partition and regionalism

In §3 I argued that Gilmore and Leonard’s argument does not go through if one switches to

![]() $F_2$

. I also claimed that the point can be strengthened. It turns out one can prove the right-to-left direction of Regionalism2

. To do that one needs plural versions of some principles we discussed. To be in line with extant literature,Footnote

32

I have formulated the subregion theory of parthood (and other principles) using exclusively singular terms. Plural versions are however readily available. For the purpose of the following argument we need the following:

$F_2$

. I also claimed that the point can be strengthened. It turns out one can prove the right-to-left direction of Regionalism2

. To do that one needs plural versions of some principles we discussed. To be in line with extant literature,Footnote

32

I have formulated the subregion theory of parthood (and other principles) using exclusively singular terms. Plural versions are however readily available. For the purpose of the following argument we need the following:

-

(P.12)

$xx \leq y \leftrightarrow \ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (y). $

Plural STP

$xx \leq y \leftrightarrow \ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (y). $

Plural STP

Given our agreed abbreviations, Plural STP just says that each of the

![]() $xx$

is part of y iff the exact location of each of the

$xx$

is part of y iff the exact location of each of the

![]() $xx$

is part of the exact location of y.Footnote

33

First let me prove that if the

$xx$

is part of the exact location of y.Footnote

33

First let me prove that if the

![]() $xx$

are part of y, their

$xx$

are part of y, their

![]() $F_1$

is also part of y:

$F_1$

is also part of y:

-

(P.13)

$xx \leq y \wedge F_1 (w, xx) \rightarrow w \leq y.$

Plural F1-Part

$xx \leq y \wedge F_1 (w, xx) \rightarrow w \leq y.$

Plural F1-Part

Suppose there is a w that is the

![]() $F_1$

of

$F_1$

of

![]() $xx$

but not part of y. By Strong Supplementation w has a part that does not overlap y. Call it

$xx$

but not part of y. By Strong Supplementation w has a part that does not overlap y. Call it

![]() $z_1$

. Given that w is an

$z_1$

. Given that w is an

![]() $F_1$

of the

$F_1$

of the

![]() $xx$

, all parts of w,

$xx$

, all parts of w,

![]() $z_1$

included, overlap some

$z_1$

included, overlap some

![]() $xx$

. So there is a

$xx$

. So there is a

![]() $z_2$

that is part of both

$z_2$

that is part of both

![]() $z_1$

and one of the

$z_1$

and one of the

![]() $xx$

, say x. But

$xx$

, say x. But

![]() $\leq $

is transitive, so

$\leq $

is transitive, so

![]() $z_2$

is part of y. Thus,

$z_2$

is part of y. Thus,

![]() $z_2$

is part of both y and

$z_2$

is part of both y and

![]() $z_1$

. That is,

$z_1$

. That is,

![]() $z_1$

and y overlap. Contradiction.

$z_1$

and y overlap. Contradiction.

Now for the argument from Plural STP to Regionalism2

. Suppose there is an object y that is exactly located at the fusion of the exact locations of some

![]() $xx$

,

$xx$

,

![]() $\ell \ell (xx)$

. Then

$\ell \ell (xx)$

. Then

![]() $\ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (y)$

. By Plural STP,

$\ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (y)$

. By Plural STP,

![]() $xx$

$xx$

![]() $\leq $

y. Let now w be an arbitrary extension of

$\leq $

y. Let now w be an arbitrary extension of

![]() $xx$

, that is

$xx$

, that is

![]() $xx \leq w$

. By Plural STP

$xx \leq w$

. By Plural STP

![]() $ \ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (w)$

. Therefore by Plural F1-Part the fusion of

$ \ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (w)$

. Therefore by Plural F1-Part the fusion of

![]() $\ell \ell (xx)$

is part of

$\ell \ell (xx)$

is part of

![]() $\ell (w)$

.Footnote

34

But such fusion is nothing but

$\ell (w)$

.Footnote

34

But such fusion is nothing but

![]() $\ell (y)$

. Thus,

$\ell (y)$

. Thus,

![]() $\ell (y) \leq \ell (w)$

. By STP,

$\ell (y) \leq \ell (w)$

. By STP,

![]() $y \leq w$

. But w was an arbitrary extension of the

$y \leq w$

. But w was an arbitrary extension of the

![]() $xx$

. Thus

$xx$

. Thus

![]() $xx$

are parts of y and y is part of any extension of

$xx$

are parts of y and y is part of any extension of

![]() $xx$

. Hence

$xx$

. Hence

![]() $F_2 (y, xx)$

. This gives us the right-to-left direction of Regionalism2

.

$F_2 (y, xx)$

. This gives us the right-to-left direction of Regionalism2

.

One cannot prove the left-to-right direction. This is interesting. In §3.5 I actually argued that this is exactly the direction that cannot be derived from the subregion theory of parthood alone—be it singular or plural as it turns out. However, we can derive it in the presence of Arbitrary Partition. Assume

![]() $F_2 (y, xx)$

. Then

$F_2 (y, xx)$

. Then

![]() $xx$

are parts of y. By Plural STP,

$xx$

are parts of y. By Plural STP,

![]() $\ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (y)$

. Let w be the fusion of

$\ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (y)$

. Let w be the fusion of

![]() $\ell \ell (xx)$

. By Plural F1-Part,

$\ell \ell (xx)$

. By Plural F1-Part,

![]() $w \leq \ell (y)$

, and therefore y pervades w. Arbitrary Partition now entails that there is a part of y that is exactly located at w. Therefore there is a material object that is exactly located at the fusion of the exact locations of the parts

$w \leq \ell (y)$

, and therefore y pervades w. Arbitrary Partition now entails that there is a part of y that is exactly located at w. Therefore there is a material object that is exactly located at the fusion of the exact locations of the parts

![]() $xx$

of y. Which gives us the left-to-right direction of Regionalism2

.

$xx$

of y. Which gives us the left-to-right direction of Regionalism2

.

And now Arbitrary Partition is starting to look really attractive. We saw in §4.1 that (i) it takes care of both the arguments from countermodels and (ii) it entails principles like Overlap and PSTP that are certainly in the same ballpark as STP. In this section we even saw that it actually entails regionalism—at least Regionalism2

. But

![]() $\ldots $

$\ldots $

4.3 Partition and composition

In the light of the results above a natural questions arises: Why don’t regionalists simply endorse Arbitrary Partition?Footnote 35 The problem is that it also entails composition principles that are different from regionalism. Or so I am about to argue.

Let me start from a “finitary” principle as a warm up. Say that x and y underlap (

![]() $\odot $

) iff they have a common extension. Let me then abuse notation and write

$\odot $

) iff they have a common extension. Let me then abuse notation and write

![]() $\oplus _1$

as a short-hand for binary fusion

$\oplus _1$

as a short-hand for binary fusion

![]() $_1$

. Arbitrary Partition entails the following:Footnote

36

$_1$

. Arbitrary Partition entails the following:Footnote

36

-

(P.14)

$x \odot y \rightarrow \exists z (z = x \oplus _ 1 y).$

Binary Underlap

$x \odot y \rightarrow \exists z (z = x \oplus _ 1 y).$

Binary Underlap

First, note that the following is a finitary consequence of Plural F1-Part:

-

(P.15)

$x \leq z \wedge y \leq z \wedge w = x \oplus _1 y \rightarrow w \leq z.$

F1-Part

$x \leq z \wedge y \leq z \wedge w = x \oplus _1 y \rightarrow w \leq z.$

F1-Part

Now for the argument in favor of Binary Underlap. Suppose x and y underlap. Then there is a z such that

![]() $x \leq z$

and

$x \leq z$

and

![]() $y \leq z$

. By STP we get that

$y \leq z$

. By STP we get that

![]() $\ell (x) \leq \ell (z)$

and

$\ell (x) \leq \ell (z)$

and

![]() $\ell (y) \leq \ell (z)$

. There is a region

$\ell (y) \leq \ell (z)$

. There is a region

![]() $\ell (x) \oplus _1 \ell (y)$

. By F1-Part,

$\ell (x) \oplus _1 \ell (y)$

. By F1-Part,

![]() $\ell (x) \oplus _1 \ell (y) \leq \ell (z)$

. By Arbitrary Partition there is a w such that

$\ell (x) \oplus _1 \ell (y) \leq \ell (z)$

. By Arbitrary Partition there is a w such that

![]() $w \leq z$

and

$w \leq z$

and

![]() $\ell (w) = \ell (x) \oplus _1 \ell (y)$

. We show that

$\ell (w) = \ell (x) \oplus _1 \ell (y)$

. We show that

![]() $w = x \oplus _1 y$

. Clearly

$w = x \oplus _1 y$

. Clearly

![]() $\ell (x) \leq \ell (w)$

and

$\ell (x) \leq \ell (w)$

and

![]() $\ell (y) \leq \ell (w)$

. By STP,

$\ell (y) \leq \ell (w)$

. By STP,

![]() $x\leq w$

and

$x\leq w$

and

![]() $y \leq w$

. Consider an arbitrary part v of w. By STP,

$y \leq w$

. Consider an arbitrary part v of w. By STP,

![]() $\ell (v) \leq \ell (w) = \ell (x) \oplus _1 \ell (y)$

. It follows that, for an arbitrary part v of w, its exact location overlaps either the exact location of x or the exact location of y. By Overlap, an arbitrary part of w overlaps either x or y. Thus, by definition of

$\ell (v) \leq \ell (w) = \ell (x) \oplus _1 \ell (y)$

. It follows that, for an arbitrary part v of w, its exact location overlaps either the exact location of x or the exact location of y. By Overlap, an arbitrary part of w overlaps either x or y. Thus, by definition of

![]() $F_1$

,

$F_1$

,

![]() $w = x \oplus _1 y$

. This gives us Binary Underlap.

$w = x \oplus _1 y$

. This gives us Binary Underlap.

As I mentioned, Binary Underlap is a finitary principle. However, the result could be generalized to cover infinite pluralities. Say that the

![]() $xx$

underlap (

$xx$

underlap (

![]() $U(xx)$

) iff they have a common extension. Then set:

$U(xx)$

) iff they have a common extension. Then set:

-

(P.16)

$U(xx) \rightarrow \exists z (F_1 (z, xx)).$

General Underlap

$U(xx) \rightarrow \exists z (F_1 (z, xx)).$

General Underlap

General Underlap is logically stronger than Binary Underlap.Footnote 37 The argument from Arbitrary Partition to General Underlap is similar to the one one we just saw

Suppose the

![]() $xx$

underlap. Then there is a z such that

$xx$

underlap. Then there is a z such that

![]() $xx \leq z$

. By Plural STP we get that

$xx \leq z$

. By Plural STP we get that

![]() $\ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (z)$

. There is a region, call it s, such that

$\ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (z)$

. There is a region, call it s, such that

![]() $F_1(s, \ell \ell (xx))$

. By Plural F1-Part,

$F_1(s, \ell \ell (xx))$

. By Plural F1-Part,

![]() $s \leq \ell (z)$

. By Arbitrary Partition there is a w such that

$s \leq \ell (z)$

. By Arbitrary Partition there is a w such that

![]() $w \leq z$

and

$w \leq z$

and

![]() $\ell (w) = s$

. We show that

$\ell (w) = s$

. We show that

![]() $F_1 (w, xx)$

. Clearly

$F_1 (w, xx)$

. Clearly

![]() $\ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (w)$

. By Plural STP again

$\ell \ell (xx) \leq \ell (w)$

. By Plural STP again

![]() $xx \leq w$

. Consider an arbitrary part v of w. By STP,

$xx \leq w$

. Consider an arbitrary part v of w. By STP,

![]() $\ell (v) \leq \ell (w) = s$

. This entails that for an arbitrary part v of w, its exact location overlaps an exact location of the

$\ell (v) \leq \ell (w) = s$

. This entails that for an arbitrary part v of w, its exact location overlaps an exact location of the

![]() $xx$

—s being the fusion of the

$xx$

—s being the fusion of the

![]() $xx$

’s exact locations. By Overlap, an arbitrary part of w overlaps one of the

$xx$

’s exact locations. By Overlap, an arbitrary part of w overlaps one of the

![]() $xx$

. Thus, by definition of

$xx$

. Thus, by definition of

![]() $F_1$

,

$F_1$

,

![]() $F_1(w, xx)$

. This gives us General Underlap.

$F_1(w, xx)$

. This gives us General Underlap.

For the sake of completeness let me note that that the subregion theory of parthood entails another locative principle that provides a counterpart, to speak loosely, of principles such as Arbitrary Partition and Strong Delegation. The idea behind such principles is that wholes should not go further than their parts. If a whole goes somewhere, so does one of its parts. Conversely, it seems plausible to require that wholes go at least as far as their parts. If one of their parts goes somewhere, so does the whole it is part of. There are different ways to capture this formally, one of which is given by the following principle:

-

(P.17)

$x \leq y \wedge x@w \wedge y @z \rightarrow w \leq z. $

Expansivity

$x \leq y \wedge x@w \wedge y @z \rightarrow w \leq z. $

Expansivity

Expansivity follows from STP. To see this assume the antecedent, i.e.,

![]() $x\leq y$

,

$x\leq y$

,

![]() $x@\ell (x)$

, and

$x@\ell (x)$

, and

![]() $y@\ell (y)$

. STP, recall, is the following biconditional,

$y@\ell (y)$

. STP, recall, is the following biconditional,

![]() $ x \leq y \leftrightarrow \ell (x) \leq \ell (y)$

. The left-to-right directly yields the consequent of Expansivity. Interestingly, Expansivity can be used to run a different argument in favor of, e.g., Binary Underlap—which I relegate to a footnote.Footnote

38

$ x \leq y \leftrightarrow \ell (x) \leq \ell (y)$

. The left-to-right directly yields the consequent of Expansivity. Interestingly, Expansivity can be used to run a different argument in favor of, e.g., Binary Underlap—which I relegate to a footnote.Footnote

38

The arguments in favor of Binary Underlap and General Underlap actually show how strong the mereology of regions needs to be for the point to go through. As I noted, spatial mereology is a model of classical extensional mereology. In effect, the following countermodel shows that a weaker mereology would not support the arguments.

Figure 4 Countermodel 3.

In Figure 4, Countermodel 3 above both Arbitrary Partition and Expansivity are satisfied but Binary Underlap—and therefore General Underlap—is not:

![]() $o_1$

and

$o_1$

and

![]() $o_2$

underlap but they do not have an

$o_2$

underlap but they do not have an

![]() $F_1$

. The significant feature of the countermodel is that regions obey a weaker mereology than before. For instance, “universal fusion for regions” fails. This, in turn, makes it possible that there is no

$F_1$

. The significant feature of the countermodel is that regions obey a weaker mereology than before. For instance, “universal fusion for regions” fails. This, in turn, makes it possible that there is no

![]() $r_1 \oplus _1 r_2$

, and therefore Arbitrary Partition does not entail that something is exactly located there.

$r_1 \oplus _1 r_2$

, and therefore Arbitrary Partition does not entail that something is exactly located there.

Binary Underlap—and therefore General Underlap—rules out Model 3 and thus Countermodel 1 and Countermodel 3 as well. Indeed, we can now close the circle, so to speak, and show that the addition of General Underlap to EM results in a mereology in which

![]() $F_1$

and

$F_1$

and

![]() $F_2$

are indeed equivalent. A little more precisely. Let EMGU be the mereology that is obtained by adding General Underlap to EM. Then, the following is a theorem of EMGU:Footnote

39

$F_2$

are indeed equivalent. A little more precisely. Let EMGU be the mereology that is obtained by adding General Underlap to EM. Then, the following is a theorem of EMGU:Footnote

39

-

(P.18)

$F_1(y,xx) \leftrightarrow F_2 (y, xx).$

Fi

-Equivalence

$F_1(y,xx) \leftrightarrow F_2 (y, xx).$

Fi

-Equivalence

The left-to-right direction is actually provable in EM alone. Suppose this is not the case. Then there is a plurality

![]() $xx$

such that

$xx$

such that

![]() $F_1 (y, xx)$

but not

$F_1 (y, xx)$

but not

![]() $F_2 (y, xx)$

. Given that y is not an

$F_2 (y, xx)$

. Given that y is not an

![]() $F_2$

of the

$F_2$

of the

![]() $xx$

, there is some z such that

$xx$

, there is some z such that

![]() $xx \leq z$

but y is not part of z. By Strong Supplementation, there is a part of y that is disjoint from z. But each part of y overlaps some of the

$xx \leq z$

but y is not part of z. By Strong Supplementation, there is a part of y that is disjoint from z. But each part of y overlaps some of the

![]() $xx$

, given that y is an

$xx$

, given that y is an

![]() $F_1$

of the

$F_1$

of the

![]() $xx$

. And given that the

$xx$

. And given that the

![]() $xx$

are all part of z, each part of y overlaps z.Footnote

40

Contradiction.

$xx$

are all part of z, each part of y overlaps z.Footnote

40

Contradiction.

The right-to-left relies on General Underlap. Suppose once again this is not the case. Then there is a plurality

![]() $xx$

such that

$xx$

such that

![]() $F_2(y, xx)$

but not

$F_2(y, xx)$

but not

![]() $F_1 (y, xx)$

. By General Underlap and our assumption, there is a z such that

$F_1 (y, xx)$

. By General Underlap and our assumption, there is a z such that

![]() $F_1 (z, xx)$

and

$F_1 (z, xx)$

and

![]() $z\neq y$

. Given that y is an

$z\neq y$

. Given that y is an

![]() $F_2$

of the

$F_2$

of the

![]() $xx$

, it is part of everything that have the

$xx$

, it is part of everything that have the

![]() $xx$

as parts. In particular

$xx$

as parts. In particular

![]() $y \leq z$

. The

$y \leq z$

. The

![]() $xx$

are parts of y. Then, by F1-Part, their

$xx$

are parts of y. Then, by F1-Part, their

![]() $F_1$

is part of y. Thus,

$F_1$

is part of y. Thus,

![]() $z \leq y$

, and

$z \leq y$

, and

![]() $ z= y$

by anti-symmetry. Contradiction. This establishes

Fi

-Equivalence.Footnote

41

$ z= y$

by anti-symmetry. Contradiction. This establishes

Fi

-Equivalence.Footnote

41

Fi

-Equivalence is particularly interesting in this context, for different reasons. First, it addresses the first horn of the dilemma we introduced in the discussion of regionalism. Second, what General Underlap claims is that pluralities that have an upper bound have a fusion. But

![]() $F_2$

is basically the definition of least upper bound induced by

$F_2$

is basically the definition of least upper bound induced by

![]() $\leq $

. Thus, what General Underlap tells us is that pluralities that have an upper bound have a least upper bound—something which is known to be algebraically important. Finally, together with the results in §4.2, it also shows that Arbitrary Partition entails Regionalism1

as well.

$\leq $

. Thus, what General Underlap tells us is that pluralities that have an upper bound have a least upper bound—something which is known to be algebraically important. Finally, together with the results in §4.2, it also shows that Arbitrary Partition entails Regionalism1

as well.

The following figure (Figure 5) sums up the logical consequences of Arbitrary Partition—arrows indicating entailment.Footnote 42 It also serves as a reminder of how powerful that principle is.

Figure 5 Logical consequences of Arbitrary Partition.

These results are not only important on their own. They have substantive consequences for the debate over the special composition question. For it is now immediate to prove:Footnote 43

-

(P.19)

$U(xx) \leftrightarrow \exists z (F (z, xx)).$

Underlap

Footnote

44

$U(xx) \leftrightarrow \exists z (F (z, xx)).$

Underlap

Footnote

44

This vindicates the claim I made at the beginning, namely, that a locative principle, Arbitrary Partition, entails (together with STP) a purely mereological answer to the special composition question, Underlap. It also shows that this is an example of an entailment between a first grade (here: the subregion theory of parthood) and a third grade thesis (here: arbitrary partition and underlap)—as advertised. In effect, interestingly enough, Arbitrary Partition provides both an example of an entailment between a first and a third grade theses, and another example of an entailment between a first and second grade thesis—given that it entails regionalism as well.

4.4 Underlap and regionalism

As we saw, Arbitrary Partition entails both regionalism and the underlap principles. What are the relations between the two? First, one should note that they are logically independent. For a model of General Underlap that is a countermodel to both Regionalism1 and Regionalism2 one needs to look no further than Countermodel 2 in Figure 2. And for a model of both Regionalism1 and Regionalism2 that is also a countermodel to underlap principles one needs to look no further than Countermodel 3 in Figure 4. However, as I noted, that model is also a countermodel of classical mereology for regions. The one below is a model of both classical mereology for regions and Regionalism1 , but a countermodel to both Binary and General Underlap: See Figure 6 below.

Figure 6 Model of regionalism, countermodel of underlap.

The two are different also when it comes to their relation with extreme answers to the Special Composition Question. Both are compatible with both extreme answers, mereological universalism and mereological nihilism. This should not come as a surprise. Usually, (allegedly) restricted answers to the special composition question single out necessary and sufficient conditions

![]() $\varphi $

for some plurality

$\varphi $

for some plurality

![]() $xx$

to compose. But they usually do not tell us whether and when the conditions

$xx$

to compose. But they usually do not tell us whether and when the conditions

![]() $\varphi $

are satisfied. At least not by themselves. Consider one of the most controversial restricted answers, namely, van Inwagen’s organicism, roughly the view that the

$\varphi $

are satisfied. At least not by themselves. Consider one of the most controversial restricted answers, namely, van Inwagen’s organicism, roughly the view that the

![]() $xx$

compose iff they constitute a life. Organicism alone—as an answer to the special composition question—does not tell us what it takes for something to constitute a life. Thus, restricted answers usually do not tell us whether conditions are always or never satisfied—which renders such allegedly restricted answers compatible with extreme ones. This does not mean there are no differences in that respect. For instance, in the presence of the universe, that is, the mereologically maximal element of which everything is part, General Underlap is equivalent to mereological universalism. By contrast, neither versions of regionalism are. In effect, mereological universalism entails only the left-to-right direction of regionalism—noting that Regionalism1

and Regionalism1

are equivalent in the presence of mereological universalism. Mereological Nihilism on the other hand, together with the assumption that

$xx$

compose iff they constitute a life. Organicism alone—as an answer to the special composition question—does not tell us what it takes for something to constitute a life. Thus, restricted answers usually do not tell us whether conditions are always or never satisfied—which renders such allegedly restricted answers compatible with extreme ones. This does not mean there are no differences in that respect. For instance, in the presence of the universe, that is, the mereologically maximal element of which everything is part, General Underlap is equivalent to mereological universalism. By contrast, neither versions of regionalism are. In effect, mereological universalism entails only the left-to-right direction of regionalism—noting that Regionalism1

and Regionalism1

are equivalent in the presence of mereological universalism. Mereological Nihilism on the other hand, together with the assumption that

![]() $@$

is a total injective function from M to R, entails the right-to-left direction of both regionalism and the underlap principles. Relatedly, regionalism and the underlap principles may diverge in their composition verdicts. Assume that I exist and consider my clavibula, the fusion of my left clavicle and my right fibula. Given that they are both part of me, the underlap principles—even the weaker finitary one—entail its existence. By contrast, regionalism is silent over the existence of clavibulas. Note that I had to assume my existence in the “clavibula argument” above, for the underlap principles are not enough to deliver that I exist. As we saw, this is not uncommon.

$@$

is a total injective function from M to R, entails the right-to-left direction of both regionalism and the underlap principles. Relatedly, regionalism and the underlap principles may diverge in their composition verdicts. Assume that I exist and consider my clavibula, the fusion of my left clavicle and my right fibula. Given that they are both part of me, the underlap principles—even the weaker finitary one—entail its existence. By contrast, regionalism is silent over the existence of clavibulas. Note that I had to assume my existence in the “clavibula argument” above, for the underlap principles are not enough to deliver that I exist. As we saw, this is not uncommon.

A final difference between the principles relates to their grade of local involvement, as they were distinguished in §1. Regionalism is a mereo-locational answer—hallmark of the second grade, whereas the underlap principles are purely mereological—hallmark of the third grade. It follows that regionalism informs us of the locations of parts and wholes. By contrast, the underlap principles are silent when it comes to locational issues.