Introduction

In 2024, the U.S. Government released a revised policy to strengthen oversight of Dual Use Research of Concern (DURC) and Pathogens with Enhanced Pandemic Potential (PEPP), domains at the intersection of life science innovation, public health and national security. The U.S. Government’s 2024 Policy for Oversight of Dual Use Research of Concern and Pathogens with Enhanced Pandemic Potential (2024 DURC/PEPP policy; Office of Science and Technology Policy, 2024) had an effective date of May 6, 2025; however, President Trump rescinded the policy with Executive Order 14292, Improving the Safety and Security of Biological Research (Executive Order 14292, 2025). Despite its stated goal of improving biosafety and biosecurity, the 2024 DURC/PEPP policy’s ambiguous language, broad scope and lack of operational detail generated widespread uncertainty among those responsible for applying it in research institutions.

This study examines how professionals tasked with institutional oversight interpreted and responded to the now-rescinded policy. Rather than analyzing the policy through a purely legal or theoretical lens, this article foregrounds the lived experiences of biosafety officers, compliance managers and research administrators: those on the front lines of implementation. In October 2024, a national workshop was convened to elicit their perspectives. Participants from diverse institutional settings engaged in structured discussions about how the policy’s definitions, assumptions and requirements aligned, or failed to align, with real-world practice. Participants expressed serious concerns about the policy’s clarity, usability and ability to be implemented. They described the text as overly long, repetitive and challenging to interpret, with key terms either undefined or used inconsistently. While the policy’s flexibility may have been intended to accommodate evolving science, attendees worried that it created confusion about what types of research were covered, how to train personnel and how to advise investigators. Compounding these challenges was a lack of guidance from federal agencies, specifically, the absence of clear expectations for risk mitigation plans, inspection procedures and standardized training resources. As with prior U.S. biosecurity policies (Department of Health and Human Services, 2017; Office of Science and Technology Policy, 2012, 2014, 2017), the 2024 DURC/PEPP policy applied only to federally funded research, raising fears of uneven oversight and the potential for research to migrate to less-regulated spaces and places, domestically and internationally.

The insights presented in this article reflect the grounded expertise of practitioners who manage the day-to-day complexities of biosafety and biosecurity. This analysis took place amid an evolving U.S. and international policy landscape. Executive Order 14292 called for revising or replacing the 2024 DURC/PEPP policy, revising or replacing the 2023 policy on synthetic nucleic acid screening (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, 2023) and developing a strategy for managing risks of research that is not federally funded. The National Institutes of Health has since initiated efforts to modernize biosafety and biosecurity oversight (National Institutes of Health, 2025), and the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine is conducting an external review of biosecurity issues in synthetic cell research (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2025a) and mirror-life (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2025). These initiatives reflect the ongoing relevance of this study’s findings to current and future policy reform efforts. By documenting these practitioner-informed perspectives, this research aims to support more transparent, actionable and equitable approaches to DURC and PEPP oversight, to protect public health and security and sustain life science research’s essential progress.

Literature review

This literature review aims to synthesize prior biosafety and biosecurity research and policy frameworks and highlight key debates and gaps that inform this study. The oversight of DURC and PEPP has evolved over more than two decades in response to shifting scientific, security and institutional pressures. The National Research Council’s Biotechnology Research in an Age of Terrorism (2004), also known as the Fink Report, articulated the risks posed by “dual use” life sciences research and recommended review mechanisms for “experiments of concern.” Building on that foundation, the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB) helped formalize the label DURC and led to the U.S. Government’s Policy for Oversight of Life Sciences Dual Use Research of Concern (OSTP, 2012), and to the complementary United States Government Policy for Institutional Oversight of Life Sciences Dual Use Research of Concern (OSTP, 2014). These were further supplemented by the Recommended Policy Guidance for Departmental Development of Review Mechanisms for Potential Pandemic Pathogen Care and Oversight (OSTP, 2017) to extend oversight of gain-of-function (GOF) or enhanced pathogens research. Several authors have provided detailed timelines of biosecurity events and publications (Epstein, Reference Epstein2025; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Wu, Zuo, Xiang, Chen, Zhang and Liu2025; Gillum, Reference Gillum2025a).

Oversight of DURC and PEPP continued to be a significant focus area for biosafety and biosecurity professionals. Historically, policy frameworks and guidance generated by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, the National Institutes of Health Office of Science Policy and the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity have sought to mitigate the potential misuse of biological research (Department of Health and Human Services, National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity, 2023; Office of Science and Technology Policy, 2012, 2014, 2017, 2024). However, recent research has demonstrated that these frameworks often lack clarity, consistency and adaptability to the rapid evolution of the life sciences, creating uncertainty for those tasked with implementing them (Gillum, Reference Gillum2025b).

One of the contested areas within DURC and PEPP oversight is GOF research. In routine molecular biology, GOF typically refers to standard laboratory techniques, such as reverse genetics, site-directed mutagenesis or CRISPR-based editing, used to genetically alter organisms and study gene function, viral host–pathogen interactions or immune evasion mechanisms (Kilianski et al., Reference Kilianski, Nuzzo and Modjarrad2016; National Academies, 2015). These tools have been foundational to virology research for decades and have helped to expand our understanding of pathogenicity pathways and inform vaccine and therapeutic development. However, the term has also been appropriated to describe riskier experiments that intentionally enhance a pathogen’s transmissibility, virulence or host range with the potential to generate novel pandemic threats (Dance, Reference Dance2021; Gillum et al., Reference Gillum, Moritz, Palmer and Weiss Evans2021). As a result, GOF has become a catchall phrase applied to a broad spectrum of life sciences research. This connotation has contributed to public confusion and political polarization, especially amid the uncertainty surrounding the origins of COVID-19 and lab-leak theories (Brownstein, Reference Brownstein2025; Chan and Ridley, Reference Chan and Ridley2021).

Imperiale et al. have previously argued that with strict biological safety and security protocols, GOF experiments can provide important insights into viral evolution, disease mechanisms and vaccine development (Imperiale et al., Reference Imperiale, Howard and Casadevall2018). Many virologists support this perspective, noting that these routine, valuable methods are generally not controversial when performed under proper oversight (Imperiale et al., Reference Imperiale, Howard and Casadevall2018; National Academies, 2015). However, others have stated that even under strict safety protocols, the research presents unacceptable risks (Lipsitch & Inglesby, Reference Lipsitch and Inglesby2014; Selgelid, Reference Selgelid2016). Evans argues that no mitigation can fully account for systemic failures or human error in high-containment laboratories, making specific GOF experiments ethically indefensible (Evans, Reference Evans2025). Others have noted that many benefits attributed to GOF research might be achievable through safer, alternative strategies such as the use of less-hazardous surrogates (Lipsitch & Galvani, Reference Lipsitch and Galvani2014). However, virologists caution that surrogate models often fail to capture important aspects of virus behavior, such as infectivity, persistence and host response, thereby limiting their relevance for critical questions about transmissibility, virulence or environmental survival (Park et al., Reference Park, Cleveland and Gandhi2025; Richards, Reference Richards2012). These disparate views help to frame the tension in DURC and PEPP oversight: while GOF-type experiments hold significant scientific promise and potential benefit, concerns still remain about what experiments should be done, and why. Part of this issue (as our participants discussed) lies with science communication, and the challenges of effectively describing the benefits of the research in a manner that makes sense and is palatable to the public.

Beyond the controversies surrounding GOF research, broader organizational and cultural factors complicate effective DURC and PEPP oversight. Basbug et al. have shown that principal investigators with high institutional status often resist safety requirements, leading to inconsistent policy compliance across research environments (Basbug et al., Reference Basbug, Cavicchi and Silbey2023). Gray and Silbey similarly demonstrate that day-to-day interpretations of regulations, shaped by organizational hierarchies, expertise and relationships, often determine whether compliance is substantive or symbolic (Gray & Silbey, Reference Gray and Silbey2014). Likewise, Vaughan’s theory on the normalization of deviance argues that ambiguous or impractical rules and processes, especially in high-pressure settings, may allow risky practices to become routinized (Vaughan, Reference Vaughan1996). However, noncompliance is not always driven by risky choices alone; researchers may disregard policies they perceive as poorly designed, impractical or misaligned with scientific workflows (Evans & Silbey, Reference Evans and Silbey2022).

The field of science and technology studies (STS) has provided ethnographic studies that demonstrate that practitioners are not merely passive implementers of rules but actively shape their practical meaning through their day-to-day work (Oudshoorn and Pinch, Reference Oudshoorn and Pinch2003). As prior research has shown, safety professionals interpret and adapt ambiguous rules based on local risk perceptions, available resources and institutional culture (Evans & Silbey, Reference Evans and Silbey2022; Gillum, Reference Gillum2025b; Gray & Silbey, Reference Gray and Silbey2014; Shannon et al., Reference Shannon, Quinn, Sutcliffe, Stebbing, Dally, Glover and Dunn2019). Adaptive risk management approaches, such as Perrow’s high-reliability organizations, suggest that oversight systems should be flexible and responsive to real-world experience, evolving iteratively through stakeholder input to maintain scientific progress, public safety and national security (Perrow, Reference Perrow1999).

This literature reinforces insights from STS, which discusses how scientific knowledge, and its governance are co-produced through interactions among experts, institutions and policy frameworks (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff2004, Reference Jasanoff2006; Latour, Reference Latour1993). From this perspective, biosafety professionals are not merely implementers of top-down directives; they actively shape how biosafety and biosecurity are interpreted, negotiated and applied in practice.

The research in this article also builds on public policy scholarship examining how frontline actors interpret and enact policy under conditions of ambiguity (Lipsky, Reference Lipsky1980; May, Reference May2015). Biosafety professionals, like other “street-level bureaucrats,” adapt formal directives to local settings and shape policy outcomes through their discretion and professional judgment. Integrating these perspectives with STS research highlights how professional expertise mediates the implementation of biosecurity policy.

Methodology

The findings are drawn from a 2-day deliberative workshop held October 10–11, 2024, at the University of Nevada, Reno. The workshop included 45 biosafety professionals, scientists, compliance officers and other key stakeholders from U.S. scientific research facilities. Participants were recruited by invitation through professional networks and national and regional biosafety associations, using purposive sampling to ensure diversity in institutional type, professional role, organizational size and geographic location. Participants included senior and mid-career biosafety officers, institutional biosafety committee (IBC) chairs, environmental health and safety directors, research compliance administrators and faculty principal investigators representing universities, medical research institutes and federal laboratories.

The workshop was conducted under Chatham House Rule, with organizers strongly committed to maintaining participant anonymity and confidentiality in all subsequent reporting, to support frank, open dialogue about experiences with policy implementation and perspectives on the 2024 DURC/PEPP Policy. This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) award #1R01GM155913-01 and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Arizona State University (IRB# 00016457) and the University of Nevada, Reno (IRB # 2102871).

The workshop combined large-group plenary discussions and small-group breakout sessions. Workshop discussions are labeled by session and room number. For example, “1/405” would refer to breakout session 1 held in room 405. Similarly, large group discussions are noted as LG. This naming scheme allows for cross-referencing of statements provided below to specific group discussions. Participants were randomly assigned to breakout groups to encourage cross-institutional dialogue, with individuals engaging in the two LG discussions and 16 small-group discussions across the 2 days. Day 1 focused on DURC, while Day 2 focused on PEPP. Structured discussion prompts guided participants through cross-cutting topics, including policy language and clarity, definitions and terminology, feasibility of practical implementation, inspection requirements, risk mitigation planning, relational and organizational dynamics and training and communication practices.

Small-group discussions were moderated by research team members (including two authors of this article). At the same time, large-group plenary sessions were facilitated by an experienced professional facilitator to promote inclusive participation and structured synthesis of findings. Notetakers were assigned to each small group to support systematic data capture. All sessions were audio recorded with participant consent, using a combination of handheld recorders and Zoom-based closed-caption transcription to ensure redundancy and reliable backup. Staff took real-time field notes to document nonverbal interactions, group dynamics and immediate reflections on emerging ideas. Notes on nonverbal interactions (e.g., body language, pauses, laughter and group reactions) were used qualitatively to contextualize participant statements and interpret emphasis, agreement or disagreement among discussants during subsequent analysis. These multiple sources were triangulated to produce a rich and accurate account of the discussions.

Data analysis followed an inductive, grounded theory approach. Full line-by-line coding was impractical because of the significant data volume (exceeding 200,000 words of transcripts). In the first phase, transcripts were closely read, and analytic memos were developed to identify initial patterns, particularly (as relevant to this article) around challenges of clarity, definitional gaps and insufficient guidance. In the second phase, these memos were synthesized into a preliminary coding framework (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz, Smith, Harre and Van Langenhove1996, Reference Charmaz2006). In the third phase, all transcripts were uploaded to NVivo (version 15), where they were systematically coded, with minor adjustments to the framework to accommodate emergent subthemes.

The analysis was led by a research team member with expertise in qualitative methods and bioscience policy, working closely with the research team as a whole to maintain consistency and rigor. Regular review meetings ensured emerging findings reflected shared interpretations grounded in the data. This methodology was explicitly designed to center biosafety and compliance professionals’ practical experience and expertise, whose voices are often underrepresented in policy evaluation. By systematically capturing their insights, this research aims to inform clearer, more actionable and realistic DURC/PEPP oversight guidance that supports biosafety and biosecurity while maintaining space for scientific progress. The coding framework and associated analytic documents (where permissible, given research ethics commitments) are available from the authors upon reasonable request to support transparency and further research.

Policy detail

Following the description of the workshop’s objectives and the data collection and analytical methods, the focus now turns to participants’ reflections on the policy itself. Participants expressed significant concerns about how the policy would operate in practice. In particular, they noted that unclear language, undefined key terms and a lack of practical, actionable guidance posed significant challenges for daily implementation. These gaps were viewed as frustrating and potentially unworkable for those responsible for translating policy into effective research oversight. The following section presents their perspectives in their own words to illustrate how concerns about clarity, specificity and guidance emerged during the discussions. Extensive quotations are retained to preserve participant voice and illustrate how biosafety professionals articulated shared concerns in their own language. These excerpts were selected to represent the most frequently discussed themes.

Participant perspectives on the 2024 DURC/PEPP policy

Lack of clarity

Workshop participants highlighted problems with the clarity of the 2024 policy, describing the policy as poorly written and difficult to read and understand. They noted the unclear definition of key terms, so that it was open to interpretation what was captured under the policy and what was not. Participants also pointed out that specific provisions (e.g., inspections) were not detailed in the policy, so what these would involve was unclear. Beyond the text of the policy itself, participants also mentioned that funding agencies had not clarified their processes for policy implementation, and that the (lack of) legal standing of the policy created further confusion.

Participants highlighted a general problem of ambiguity and lack of clarity in the policy. As one participant put it, “even the framework is kind of nebulous and ambiguous in its own right” (2/402). This ambiguity leaves the policy open to interpretation by individuals and institutions: “it is very nebulous language right now, it’s very open to interpretation and people’s perception of the risk associated with particular research” (3/405). As another participant put it: “We’re not getting clear communication. You’re left to your own interpretation, to some extent […]. They lay down the groundwork, but then there’s some ambiguity associated with it. Translating it into practice” (1/405). Thus, the same policy could be applied very differently in different settings by different individuals or agencies. To go further, this ambiguity and lack of clarity would arguably make policy implementation impossible, because those tasked with implementing the policy “literally don’t know how to apply this,” or how to explain it to scientists at their institution (2/402). As one participant asked: “how are people supposed to be able to implement it if they don’t have an idea of what the scoping is” (3/405). Participants called for “Some intentionality in that communication. […] That way Institution A doesn’t go this way, and Institution B, same set of rules, goes that way. Interpreted very differently” (1/405).

The policy’s lack of clarity had several aspects. First, as repeatedly noted by participants, the policy was simply poorly written and difficult to read and understand, even for trained scientists and biosafety professionals. Particular issues noted were wordiness, repetition and redundancy and unnecessary complexity:

It’s so wordy, and it’s like the same long phrases over and over and over and over again. And it’s like, why do you have to use that phrase again? Like every other sentence or – like, I’m serious. I got so sick of reading that same phrase. […] they did not need to reuse those things, and it could have been a little bit more concise, I think. (1/402).

They were using certain phrases in the new document over and over […] the redundancy in it wasn’t well written. […] one sentence kept being repeated. (2/405).

The second key aspect of this lack of clarity, beyond just the standard of the writing, is that key terms in the policy were not defined, so that it was unclear what would be captured under the policy and what would not:

I think people are actually really confused about what a DURC experiment actually is. […] When I read these, the little words here, […] ‘could be directly misapplied’. Well, how on earth are you defining ‘directly’? How on earth are you defining ‘reasonably’? There’s a lot of these kinds of things. (1/320).

I think one of the hard things is […] what is the definition of PPP and PEPP? Because the classical definitions that we were working on with the 2017 [policy], it was more clear-cut. This is what falls under it. This is what’s not. So there’s a lot of, I would say, confusion, even from my institution, of what is going to fall under this policy. Is it certain agents? Is it criteria? Are [the scientists] experienced? How do we capture them? So I think it’s, first and foremost, what even falls under this policy is difficult to define. (3/402).

These quotes are a reflection of the challenges of trying to understand what is meant in policy and making it a reality at an institution. Greater care is needed to ensure that the purpose of the policy is understood and effectively implemented at institutions.

In some cases, the problem was not lack of definition but inappropriate or inaccurate use of scientific terms that have their own clearly defined meaning outside this policy:

You can see that the people who drafted this did not consult epidemiologists. […] it goes from word to word to word. ‘Highly transmissible’. Highly transmissible also has an epidemiological connotation […] So I mean, I guess I do not tell you anything new there, but this is not thought out. (3/405).

There is an inherent ambiguity when adverbs such as highly are incorporated into policy language. What qualifies as “highly transmissible” in epidemiological terms may differ significantly from how the same phrase is understood by biosafety professionals or the general public.

Participants repeatedly pointed out that the general lack of definition meant that the policy, taken at face value, would have extremely broad scope:

When you talk about research that can be misapplied through minor modification, what does that mean? Because to me, it could be interpreted [very broadly], right? So it’s really hard to know exactly where the line is of how far and wide we need to apply this [policy]. And who knows, I may have a very diligent and industrious PI that is doing some of the basic science research that’s like, oh, crap, bioterrorists could use this. He’s not wrong. He may not be right either, but where is that line? (2/402).

I have some questions about the definitions on some of these things […]. Like, how are they supposed to be applied? So the category one where it says ‘alter the host range or tropism of a pathogen or toxin’, I mean, when I think about all the work that’s done at the university, we have BSL-2 organisms where people do that all the time. Like, all the time. And if you have to do that for every one of the E. coli on campus, like, it’s going to be a lot of work. (4/405).

These excerpts illustrate the challenge of determining what falls within the scope of the policy and what does not. When the criteria for concern are so broadly defined that nearly any research could be interpreted as dual use, institutions are left uncertain about where to draw the line between legitimate inquiry and regulated activity.

In practice, this means that the definition of key terms becomes ‘highly subjective’ and open to interpretation:

I’m a little bit nervous with the word ‘pandemic’ and everything else, because it’s undefined. And just because there are three different individuals in four different countries, or something, does not to me mean that we have a pandemic, right? To other people, it might. (4/405).

What do you see as the biggest challenges for potential pandemic pathogen oversight in the future?

[…]

I think it’s still a subjective definition, right? And so we are always going to be arguing, well we do not think that meets the definition. Oh, we think it does, you know, then who’s right? ‘Likely virulent’, or whatever the hell they are saying. Yeah, from a parent strain, I mean even some of the adaptive strains are just like, ooh, you know? It’s like, come on. (LG).

I think it’d be one situation if, by building on the definitions, they took these assessments of ‘potentially’, or ‘highly likely’, or things like that, and put much more of an intelligence parlance into it. So there are actual levels of significance associated with particular types of assessments. So high confidence versus medium confidence versus low. So but there is not even that. It’s highly subjective […]. So I think that’s a significant problem. (3/405).

As noted previously, the use of undefined adverbs (e.g., potentially, highly, likely) introduces significant interpretive variation and complicates implementation. Beyond linguistic ambiguity, both social context and political calculus influence how such terms are applied; for example, some may consider human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections worldwide to represent a pandemic, while others may not. These interpretations often hinge not only on epidemiological evidence, such as case numbers and transmission, but also on political, institutional and governmental priorities. This is part of the broader challenge of defining significance within public health policy.

Participants pointed out that the lack of definitions and broad scope of the policy may well result from an attempt to be proactive or forward-looking, recognizing the developing nature of science. Avoiding strict definitions could build in flexibility and help to future proof the policy against emerging, unforeseen concerns. The downside and risk of this approach, however, is lack of clarity:

I think these new things are trying to be proactive, but if the intent of being proactive creates the nebulosity of confusion. Where’s the line? How do we look at these things, because definitions, mortality, morbidity are definitive things. But in these contexts of working with these agents, what you can do with them, it all depends on what you are doing with it. So that’s, I think, in my opinion, where these new things become very hard for us, or at least me, to wrap my head around and how to go about these things, because it’s trying to be proactive. But in a proactive approach, it creates so much ambiguity that a lot of us are just almost catatonic, like, I do not know what to do, I do not even know how to train on this, because it’s inherently convoluted […] You’re trying to be proactive, but that causes more confusion and scope-creeping, if you will. (3/405).

When a policy requires subjective interpretation of its boundaries, it is inevitable that it will result in variation in how institutions understand and implement it.

The tension between clear definitions and flexibility in the context of ever-moving scientific research is, admittedly, a challenge without any obvious solution, as participants themselves acknowledged and discussed. As one pithily summed up:

We’re in the business of research, we are making discoveries. And so the definition of a dangerous pathogen or something, it’s evolving, it’s growing. […] So it’s this weird stalemate situation, like, okay, having a list [of agents] would be helpful because people need guidance, but then with having the list backfire and have unintended consequences of being so absolute that things that are outside the list are now automatically okay. […] So yeah, that’s the big question is how to, yeah, have guidance, but without definitions that are so strict that they would just not be very useful. (3/406).

Participants also recognized that the definition of many of the terms used in the policy is inherently political. This includes the term ‘pandemic’ itself, for which participants noted ‘political’ (or expedient) exceptions to the definition, ranging from HIV to the common cold:

WHO has never declared HIV as a pandemic. So it’s actually not a pandemic. […] There are only two viruses that have ever caused a pandemic according to the WHO, the SARS-CoV-2, and now monkeypox is going in that direction. But by their own definition, it would meet their definition of what a pandemic is. But they need to declare a pandemic to make it a pandemic. They’re not declaring it. Which is a political process. (4/405).

Participant 1: All the rhinoviruses, all the common cold viruses are, for sure, a pandemic. They’re a big one. Everybody gets one all the time. But nobody wants to put them into this […].

Participant 2: […] they really will not call it a pandemic if it’s something that’s already a pandemic.

Participant 1: Well, SARS-CoV-2 is endemic.

Participant 2: Yeah.

That’s why there’s no longer a pandemic anymore, because it’s everywhere now. So now it’s just an endemic. Now it’s endemic everywhere.

Participant 3: There’s supposed to be that significant morbidity […] and mortality.

Participant 4: Which also epidemiologically just does not make sense.

Participant 5: No. Or maybe significant to one person is not significant to another. (4/405)

As another participant later noted: “The moment you take a scientific stringency mind to all of this, you see that for all of these processes, there is one exception over there, but this does not count” (4/405).

As previously discussed, the classification of a public health event as a pandemic or as an endemic is inherently political and has direct consequences for how resources are distributed and prioritized. This politicization of terminology within policy contexts undermines efforts toward definitive interpretation and consistent implementation, as one participant observed:

The whole conversation around PPE [Personal Protective Equipment], especially over the past five to six years, is much more ideologically driven and politically driven as opposed to scientifically or evidence-based driven. And that’s created a lot of conflict between trying to implement something that is basically unscientific to a scientific process. And that makes it very frustrating for everyone to then try to implement it. And therefore, that’s why definitions matter. (3/405).

There is, admittedly, a risk in accepting the participant’s distinction here between politics and apolitical science that somehow produces pure knowledge or fact. Rather, we would argue, scientific truth or evidence has its own social context and construction. Yet the quote nonetheless highlights the tension between politics and science when they meet in the policy context.

Beyond the lack of clarity in the policy wording and definitions, participants also pointed out that the policy lacked clarity around its requirements and provisions for implementation and enforcement, notably the risk mitigation plan and inspections:

It feels more like they have presented us with a problem. And the most bare bones basic skeleton of a solution, but without any flesh to the idea. […] So […] one thing that kept frustrating me is it kept talking about developing a risk mitigation plan. What is that? Is it not doing the research? Is it changing what it is that your research goals are? Is it using a different organism? Is it restricting what gets published? Is it restricting who has access to the publication? What does that look like? But there’s no framework for it that I saw. (2/402).

The other giant black hole that is super nebulous for me is the inspection portion that will be implemented, because it says that […] if you do all these things, and if you review it at the local level, and you identify that, yes, this is DURC, you submit these plans, well, then the agency can come back and do these on-site inspections. […] What does the inspection entail? Are there guidelines for how the inspections will be conducted? Who are you using to do the inspections? So are you using, say, like, the Federal Select Agent Program coming out, and if they are doing an inspection, and are they looking at your DURC activities while they are inspecting, according to your select agents? And then they are submitting that report to an agency. Do you have a separate group of inspectors who will be trained to specifically only assess DURC? That is an extremely nebulous statement that just says inspections will be conducted, but it does not say who, what, how, what frequency, what expectation. (1/406).

These accounts highlight that the problem was not only what the policy said, but what it failed to specify. The absence of concrete guidance on risk mitigation plans and inspection processes left attendees unsure of how to operationalize the policy’s intent, which led to a broader sense of uncertainty and frustration.

Beyond the policy itself, funding agencies had not clarified their implementation processes either (as of the date of the workshop), even though, for example, funding applications submitted prior to the implementation date (6 May 2025) might be subject to the provisions if the funding decision happened after that date (as discussed in 3/406). As one participant said: ‘The NIH and other agencies should be a little bit more […] transparent […] like, the logistics […] of what’s going to happen and how this is going to happen. […] That’s where I think a lot of confusion lies’ (3/406).

The general lack of clarity was exacerbated by the (lack of) legal standing of the policy, as guidance rather than law: “These are not congressionally directed. These are agency things. So that’s the difference, right? […] It just adds to the general murkiness of all of this, because they’re not laws. They’re just guidance” (2/402).

While participants repeatedly highlighted the policy’s lack of clarity, from poorly defined terms to ambiguous language, their concerns did not stop there. Beyond struggling to interpret the words on the page, many practitioners also felt that the policy lacked the specificity to put its intentions into practice. In other words, even if the language were made more transparent, they argued, the policy still fell short of explaining precisely what it was trying to address and how institutions should respond. This deeper problem of insufficient specificity forms the focus of the next section.

Lack of specificity

Participants’ concerns about the policy’s lack of clarity were related to its lack of specificity. These are distinct points, yet the distinction is deceptively subtle. While lack of clarity relates, fundamentally, to the wording of the policy (i.e., is the policy clear on its face?), lack of specificity relates to the policy’s intent (i.e., what is its intended meaning?).

In calling for greater specificity, what participants repeatedly requested, in practical terms, were real-life case studies (as opposed to hypothetical or general policy terms). Further, they called for these case studies to be broken down to highlight the specific concerns, and thus to illustrate how the policy should be applied and how to explain it to scientists at their institution. Thus, in calling for specificity, participants sought to root the policy in real or actual problems that had occurred and had prompted the development of the policy, both for their own understanding of how to apply it and to justify the provisions to researchers. The following quotes illustrate these arguments:

One of the big things that I would love to see with a lot of these policy initiatives is […] more examples about, OK, specifically, what is your concern here? Give us some case studies that have led to this development of this policy. What were the primary concerns? Just break it down so it’s easier for us to digest. And then I think it would also be helpful in terms of that information and disseminating that training to our faculty to say, OK, this is why now we have to bother you with these additional details. The process is changing, and this is why. […] So being able to tell them, OK, these are the concerns here. This is why this policy is actually being developed, because there were actual issues with publication and dissemination of information. (2/402).

I think one of the main goals that we need to focus on, too, is defining, OK, what are we actually looking for here? And being able to provide case studies and practical examples to people, because that’s really how the PIs are going to relate. If we can say, OK, these are some of the publications of concern that have gone out in recent years that have prompted and inspired this new policy. And again, that’s where it would help to get some of that additional information with the policy. I think we are all aware of some of the bigger DURC-related publications that are famously cited and things like that. But what specifically […] breaking that down and defining it. (2/402).

What we really need is a little bit more specificity. What are the real concerns here? I hate the broad language, because again, it leaves it open to interpretation. (LG).

It is worth noting the double meaning of words like ‘really’ and ‘actually’ in this context. On the one hand, these words root the policy in real-world problems and concerns, as noted above. Yet these words also reflect a repeatedly implied perception among participants that the policy does not ‘really’ mean what it appears to mean on its face – in other words, that the intended meaning is not reflected (or not reflected clearly) in the text itself. We can see this in the quotes above (italics added): ‘What are we actually looking for here’ (2/402); ‘This is really what we are looking at’ (3/405); ‘What are the real concerns here?’ (LG). This refusal to accept the policy on its face is notable and curious, though it arguably reflects the problems of both clarity and practicability (discussed later) in the policy itself – in other words, participants had concluded that the policy could not possibly mean what it said because this did not make sense.

These comments highlight a recurring tension in how participants interpreted the policy. Because the wording seemed unclear or even implausible on its face, participants felt they had to look past the text to infer what the policy was “really” trying to say. The less straightforward the text seemed, the more participants relied on the policy’s spirit to guide them, even as they continued to call for clearer, more usable wording. This reflects the practical challenge of implementing a policy whose stated meaning and intended meaning were not well communicated.

The distinction between the policy’s intent (the ‘real’ meaning) and clarity (face value) is helpfully summed up by Participant 1 below, who argues convincingly for the primacy of intent, not least given the challenges (discussed above) of policymaking in a context of fast-moving science and emerging concerns:

Participant 1: When we get so caught up, so focused on words, that we lose the intent, are we actually creating…

Participant 2: The intent’s there, and trying to create a definitive line is where policies do not fit into an area there, because I’m trying to be proactive in a […] steam forward research area with everything, it’s hard […].

Participant 1: I do not want to have, as part of my job responsibility, to have a legal counsel of how do I interpret this, and are we falling in, or out of scope of this, and that’s, when we get that hung up on words, then actually we are stagnating, and well…

Participant 3: So one question, […] would you like then more specificity in the policy, […] do you find it ambiguous to when you might have to go to legal now, or not?

Participant 1: I do not know if I personally find it ambiguous yet or not with the new policy. I think it’s broad application, and again, when people get hung up on words, we are spending much more time parsing out what the words mean than to, okay, here is the intent of the policy and what we should do, right? (3/405).

This exchange highlights the delicate balance between language and intent in policymaking. Words give policy its form, but intent gives it direction. Without careful consideration to both, even well-intentioned policies can lose meaning in practice.

Finally, calls for greater specificity were closely linked with the desire for more guidance on how to apply the policy in practice, as further discussed below:

Having some additional guidance there where we actually see, OK, these are the specific things that we are looking at here in terms of the DURC review would definitely help streamline our development of the training and dissemination of the information to the faculty (2/402).

Although participants felt that greater specificity would help anchor the policy in real-world practice, they emphasized that specificity alone would not be enough. They argued that a well-defined and targeted policy still requires robust guidance to translate its aims into day-to-day implementation. Without concrete, actionable direction from policymakers and funding agencies, institutions feared they would be left to interpret and operationalize the policy in isolation, risking inconsistency and confusion. The following section explores these concerns about the broader lack of guidance in more detail.

Lack of guidance

Closely related to the lack of clarity and specificity, as discussed, participants noted the lack of guidance from policymakers and funding agencies about how to interpret and implement the policy – in other words, to supply some of the missing clarity and specificity. As one participant put it in the workshop’s closing plenary session, the policy as it stood was “just [going to] cause a whole bunch of questions, speculation and basically spinning up an entire community to try to figure this out without any support or guidance” (LG). It seems, in fact, that further guidance was initially promised, yet this was later retracted:

I reached out to the Office of White House Policy about the new synthetic nucleic acids guidance. And I said, in your initial open house, or roundtable, whatever, town hall meeting, you said you were going to give us extra guidance. Where is that guidance? Oh, we are not going to give you any extra guidance. In fact, if you could get back to us and let us know what it is that you ended up doing, and talk to your colleagues for us, and let us know what they do. (1/320).

Whether due to a change in agency leadership or broader political calculations during an election time, the decision not to provide accompanying guidance was viewed by participants as unacceptable. Issuing a policy without precise mechanisms for interpretation and follow-up not only creates confusion but also represents a significant waste of public resources, such as taxpayer funding, policymaker effort and institutional time. Policies of this kind require not just intent but infrastructure: clear guidance, support and accountability to ensure that implementation is possible in practice.

At the broad level, guidance is needed in order to clarify requirements, allocate resources and ensure consistent implementation across institutions, as some participants noted:

Until we get more guidance […] we cannot really tell them [scientists] how much of a burden it’s going to be on them, because we do not know how much it’s going to be a burden on us. (1/406).

Participant 1: There needs to be real guidance associated with it. There needs to be telephone numbers associated where you can call and you can ask how something is being met. All of these things, they need to be put in place. They cannot someday come up with a new framework and dump it on everybody, and then every single person here sits and says, I do not know how to do this.

Participant 2: And then everyone does it differently, so it does not really…

Participant 3: Right, and there’s also no consistency or standardization and everybody’s trying to make it work, right? (2/320).

Issuing a policy without accompanying guidance risks rendering it ineffective. Without it, implementation becomes fragmented, burdens are unevenly distributed and frustration grows among those expected to comply. Future policymakers should prioritize the development of clear, accessible guidance and support mechanisms to enable coherent and practical implementation.

Participants particularly called for further guidance to make up for the lack of clarity in the policy, notably around definitions and scope:

Health and Human Services, it would be very helpful if they could put out more guidance to universities and research on what they mean or what they are looking for. (3/405).

When I look at the definition of PPP […] I feel like different people are going to have different ideas of what those pathogens are, and it’s like, well, what if we miss one? But then what if an IBC member thinks everything is a PPP? And I feel a little, like, lost there with initial identification of a PPP. Some are obvious, but, like, thinking about monkeypox or mpox before these outbreaks, I do not think I would have thought of that as one, for example. So I wish there was a little more guidance on PPP identification to begin with. (3/406).

We need more guidance to make sure that we are appropriately implementing. […] And we cannot come out guns blazing to researchers because that’s a lot of additional work for everybody and then have the government back up and go, wait, wait, wait, we only meant group 3, group 4, really. So my bet is that the ‘alter host tropism’, what it really meant is towards humans. I mean, yeah. It’s not written there. (4/405).

Effective policymaking requires not only written rules but also sustained support to ensure they can be understood and implemented in practice. As discussed in the previous section, it is worth noting the distinction drawn in this quote between what the policy says, on its face, and “what is really meant” (italics added), as the participant believes is most likely.

Participants also called for further guidance to make up for the lack of clarity around implementation requirements in the policy, for example, around training and the risk mitigation plan:

Participant 1: We’re looking and hungering for some kind of guidance to be able to get that training [developed] […] also guidance with developing risk mitigation policies. […].

Participant 2: I’ll train anyone on anything. I just need to know what to train. We’re not totally sure, other than, here’s 30 pages. Like, do it.

Participant 3: Who grades the mitigation policy? […].

Participant 2: […] if you do identify DURC, you are going to have to develop a risk mitigation policy.

Participant 1: But […] what exactly is a risk mitigation plan? Is it, oh, you cannot do the research now because we have identified this potential research as DURC. OK, you can do this, but it has to be with a different organism. OK, you cannot publish the data. Or it’s confidential who it is shared with. […] And then also, if a policy is telling me I need to develop a risk mitigation plan, what are the guardrails for that plan? Or are there none? Well, and who grades the effectiveness of that plan? You can write a document that has the word plan in it. I might just say, do good and be well. (2/402).

The problem is not unwillingness to comply but uncertainty about what compliance actually means. Without clear examples or evaluation standards, institutions are left to invent their own approaches to training and risk mitigation, producing inconsistency and frustration. One further specific implementation issue on which participants called for guidance is that of previously funded, ongoing projects – how, if at all, would the new policy apply to these?

How things are going to apply to existing protocols, how are you going to approach that perspective? That’s what we are wondering, if any more guidance will come out on that or not, do we have to retroactively now go back through the 200 that we already have and have to review those, or is it just from May forward and new ones that come in, and/or if those previous ones get renewed, now they are falling into [the scope of the policy] (4/402).

If it’s already a funded grant […] that’s where the challenge is. It’s how will the funding agency do it, we do not know. (4/402).

Without clear timelines or criteria for retroactive application, compliance risks becoming inconsistent and dependent on local interpretation. The lack of guidance from funding agencies – which ‘may or may not ever come’ (1/406) – was impacting institutions planning for implementation, forcing them to keep things open or to delay planning at all:

The guidance from the funding agencies has yet to come out if they are going to go above and beyond the policy or if they are going to stick by just the letter of the policy itself. So, yes, we are putting implementation plans in place right now, but they have to be flexible because the funding agencies have not come out with their requirements yet. […] everybody is still flying blind to some degree with all of this. (1/405).

I keep hearing this rumor […] that we need to wait until the grant agencies create a process. And that’s where I’m stalled out with our IBC right now. Our IBC, our Office of Research Integrity, which falls under research arm of the university, is saying, there’s no point in doing anything […] because there’s guidance that’s going to come from the grant agencies. It just seems like we’ll be waiting. (3/402).

These comments point to the need for a cohesive and coordinated policy implementation process. Guidance from funding agencies is a critical component of this process, as their terms and conditions ultimately shape how institutions operationalize policy requirements. Such guidance should be issued simultaneously with the policy itself, alongside clear implementation frameworks and supporting resources to ensure alignment, consistency and timely compliance across the research community.

One participant suggested that the lack of guidance from funding agencies at this point might be due to a lack of engagement by policymakers with these agencies during the policymaking process, leaving funding agencies to develop implementation guidance post hoc in response to a top-down mandate; similar, in other words, to the issues facing institutions:

It would be nice to see some of the policymakers maybe reach out to some of these resources [such as funding agencies] beforehand so that when we get these policies, there’s a little bit more guidance for something that they are comfortable working with (2/402).

Gaps in communication during policy development reverberate through the system, leaving both funding agencies and institutions struggling to interpret and apply unclear directives. While clarity, specificity and guidance gaps were central concerns, participants also raised broader questions that extended beyond the policy’s language or implementation challenges. These reflections went deeper, interrogating the policy’s fundamental assumptions, purpose and overall effectiveness. On this broader critique, participants examined whether the policy could truly achieve its stated goals or whether, in its current form, it risked unintended consequences and missed opportunities.

Wider critique

This section covers participants’ wider critiques of the policy, not just its present wording and content, but its overall approach more broadly. Participants raised diverse questions about the policy’s purpose, practicability and effectiveness.

Purpose and rationale

There was seemingly majority agreement, if not total consensus, that the policy’s underlying rationale was sound and important. That is, the ‘spirit’ of the policy was satisfactory, even if the current version was not. In other words, for most participants, trying again to produce a better policy, rather than just throwing it out altogether, would be the way forward (see, e.g., 4/406, LG). This participant, for example, puts the case clearly that the rationale for the policy was genuine and its spirit good:

Having been on an intelligence panel […] there is a real risk. There is a reason for this policy. It’s very difficult to communicate that outside of a classified environment. And we have to do a better job as an […] intelligence community and national security community to find unclassified ways to communicate what that risk is. Because I think otherwise, we get this reaction, this is just a knee-jerk reaction to the pandemic. This is just a knee-jerk reaction to this. And having sat on the other side, I can say with confidence, there is a risk. And there is a reason for these policies. So if we keep that in mind and move forward, I think that will help. And […] we talked about the spirit [of the policy], right? And everyone’s like, oh, the spirit’s good. And they must understand the spirit’s good because there’s something driving it, right? (LG).

That said, other participants were more skeptical and discriminating in approving the spirit of the policy, across the board:

Participant 1: There’s elements of [the policy] that are really necessary, right? Like, we do not want to be publishing things that other countries or […] bad actors, even on the homeland, that they can use in ways that are going to be harmful to the population. […] You know, it’s there for a reason, and there are at least elements that are necessary. Every part of it necessary, well, that’s up for debate, probably.

Participant 2: Is there a better way of doing it?

Participant 3: Probably. There’s always a better way. (1/405)

These quotes suggest that participants recognized the importance of the policy’s goals but questioned whether its present version effectively served them, calling instead for a more thoughtful and collaborative reworking.

A particular point that was raised, with regard to the purpose of the policy, is that the policy was political, ideological or interest-driven, and that this may explain some of its intrinsic problems:

They were looking to hit certain benchmarks, and they were looking to hit certain outputs, preferably in advance of certain kind of political events. And there’s a massive political element associated with this. There are also ideological elements. (LG).

The security community in particular tends to be very reactive and knee-jerk and tends to look at the glass half-empty. So if they see something that even smells like something that would be potentially risky […] [it] creates knee-jerk reactions, which makes it politically unviable to then put forward these studies. […] And I think that is my biggest concern, is that the policies do not make sense. The policies are driven by interest. They’re not driven by fact. (3/405).

There was a perception that the policy’s development was influenced by political and ideological considerations and could undermine its credibility as a science-based framework.

Finally, it is worth noting that even those participants who accepted the rationale, or underlying justification, for the policy were trenchant in criticizing the mismatch between its spirit and its letter:

I think the individuals that were working on this policy had the right intentions. I think that if we look at spirit as in, does this actually help us in addressing the risk sets that they are meant to address? Then I would say no. And […] we can be well-intentioned, but also the path to hell is paved with good intentions. […] I would say that the spirit is not necessarily there in terms of the policy itself. The people might have had good intentions. But frankly speaking, I think that the policy is really stupid and does not accomplish what it’s meant to accomplish at all. (LG).

Participants generally agreed with the motivations behind the policy but doubted that its current form could realize them and pointed to a gap between good intentions and effective practice.

Practicability and top-down design

A further key concern raised by participants is that policy development had been top down, rather than drawing on insight on the ground. This creates immense challenges for implementation, because the policy simply did not align with institutional processes and constraints, nor with the practical realities of scientific research. The following excerpts sum up participants’ frustration:

I do not know who was sitting on developing these policies […], but it was rolled out in a way that this is a definition of a top-down thing. […] And it is not in any kind of way thought out. (1/320).

It just does not make any sense that they put this out without speaking with the people that actually have to implement this kind of stuff. […] if they actually want this to be done correctly, then they should have allowed greater input in the overall scheme of things. And I know that […] the government, USG always throws stuff out, they say they want public comments and all that kind of stuff. No, they do not want public comments. They’ve already made up their mind, this is how it’s going to be, you know, make it happen (4/320).

I’m equally frustrated with providing feedback and then seeing the feedback not being implemented in any other form […] Like, I can get the new [draft of the policy] that comes out and stuff, and provide edits […] I think, three times over the last six months, and every single [version] is even worse [than the previous version]. (LG).

Did you [policymakers] think about how many issues you are creating by simultaneously requiring additional expanded requirements while not increasing the funding and the budgets and the resources, expecting all of these institutions to be able to just carry it by themselves (2/406).

These discussions point to the dangers of developing policy in isolation from those who must carry it out. Participants saw the process as emblematic of a wider disconnect between federal policy ambitions and the everyday realities of institutional practice.

Participants expressed particular frustration with a perceived reliance in policymaking on theoretical rather than practical expertise, once again leading to major challenges for on-the-ground implementation in due course:

Part of the problem […] was when policies like these are made, not having biosafety people with practical implementation experience on it because they could easily have told them, you know, these things will not work or you need to clarify it better or have exceptions in place. And oftentimes it’s policy people who have not done any practical experience get on these committees or working groups and put things in place, which once it comes out, we are all going, this is not going to work. So that’s really where the problem starts. (1/402).

Participant 1: The people that they are asking for advice, they are calling themselves experts […] but they actually have no idea what we do, nor do they, I think, read the current requirements, […] and for me, that’s concerning because these are often the people that are being called to Congress, and […] you are like, you have no idea […] how the changes that you are proposing are going to actually affect, or not affect, I suppose, one way or the other, on the ground.

Participant 2: […] it’s all theoretical, and as you have the discussions with them, you find out, even like basic stuff, there’s no understanding of it, and it’s actually alarming, because they are not in the implementation space, they have all the time to sit and talk about it, […] but it’s purely theoretical, and a lot of things that are suggested just are not practical, because they just do not know the ground reality of things. (4/320).

These quotes illustrate how policymaking divorced from practice risks producing rules that cannot be effectively implemented. Participants viewed this imbalance between theoretical and practical expertise as a fundamental flaw in the policy’s design.

Overall, participants viewed the policy as a well-intentioned but ultimately flawed attempt to regulate high-consequence research. They acknowledged its spirit and rationale but described a disconnect between the ideals behind the policy and its likely impacts on the ground. Concerns about top-down decision-making, impractical requirements and political drivers left many practitioners questioning whether the policy could support security and scientific progress. These deeper critiques reflected a frustration that policies affecting research practice too often fail to reflect the realities of the laboratory environment. Building on these broader critiques, participants also reflected on a more fundamental question: whether the policy would achieve its intended safety and security outcomes at all.

Effectiveness

Beyond how the policy was designed or implemented, many participants questioned whether it could meaningfully improve biosafety and biosecurity in practice. They worried it might create a sense of compliance without delivering actual risk reduction, adding paperwork rather than promoting safer research. Some framed this concern as “performative” regulation, or policy that looks protective on paper but fails to change behaviors or outcomes. Others wondered whether the policy might have the opposite effect of its intentions, pushing riskier research overseas. These reflections on the policy’s practical effectiveness and its potential unintended consequences are explored in the following discussion.

Performativity and paperwork

Participants repeatedly questioned whether the policy would have any real or commensurate effect on safety or security, or whether it would merely increase administrative and paperwork burden:

I’m more concerned about […] that administrative burden. […] where has that increased safety and security? Why are we doing this part? And where is that benefit? I want to see a benefit for all this paperwork that we have got to do. (1/406).

Are we just generating checklists or are we actually doing something towards making people more aware, and really thinking about, okay, DURC actually applies to me, and these are the reasons why. And here’s what I should do about it. (2/406).

There was a frustration that the policy could create the appearance of action without delivering real impact. For participants, the measure of success lay not in more forms or procedures, but in demonstrable improvements to safety and awareness.

Participants further suggested that the policy was ‘performative’ (1/320): that it would serve to create an illusion of greater safety and security for the sake of public perception, rather than a real, demonstrable improvement:

In the end, we do not manage it any differently. […] it’s public perception. […] We’re not safer, more or less safer anyway. […] The only thing we are really treating differently is the data and how it’s presented or put out into the world, making sure that it’s conveyed in a way that will not be taken the wrong way by laypeople. (3/402).

Is there a measurement to say what they are trying to do is actually effective or not? That’s the missing piece in all this for me […] we push through these rules because a reporter is freaking out or there’s all these news stories. Instead of like, is it really going to reduce risk? […] Is this a mitigation trend or is it a paper tiger, like is it a trap? […] Because I think we are creating a lot of paper traps for researchers and ourselves, honestly. (2/406).

There’s a dichotomy that exists that all of us see all the time, which is, you see things like TSA [the Transportation Security Administration], security and safety theater, and […] really, actually important stuff […] things that actually impact safety. […] Does this policy actually increase safety and security? Or is it just to increase the perception of it? […] It’s going to make people feel good about biosafety and security, but it’s funny. But is it really doing anything? (4/406).

There was a concern that the policy’s main achievement may be reassuring the public, not reducing actual risk. This concern with performativity is closely related to the widespread culture of ‘getting round’ biosafety and biosecurity policy (which we discuss in detail in a forthcoming paper based on the same dataset). In other words, given that researchers will simply work out how to get round it, the policy is mere window dressing – a ‘paper regulation’, as this participant puts it:

Essentially, the PIs are going to become wordsmiths. They’re going to learn how to express things, how to describe it; how to circumvent [it]. So that’s a caveat […] that I will have to deal with. I do not know if that was well thought out either. Or does it just become a paper regulation, very similar to what a lot of a select agent [regulation] is? (LG).

Participants’ concerns about effectiveness highlighted a fear that the policy would not meaningfully strengthen biosafety or biosecurity but would instead add burdensome procedures and encourage box-checking behavior. While participants broadly supported stronger oversight in principle, they questioned whether the policy would have a measurable impact or whether it might simply create new administrative hurdles without improving outcomes. These reflections revealed a tension between genuine risk mitigation and policies that serve more symbolic or political purposes. In addition to these worries about practical effectiveness, participants raised related questions about the policy’s legal force and the consequences of its limited regulatory scope.

Legal standing and scope

Beyond the issue of performativity, participants raised further concerns about the effectiveness of the 2024 DURC/PEPP policy relating to its (lack of) legal standing and limited scope. First, this was policy or guidance rather than legally enforceable regulation (as also discussed under the Lack of Clarity section); and second, the policy has limited applicability, capturing only federally funded research and leaving work that does not receive federal funds out of scope:

Some of these things need to be a regulation. […] I know it’s not popular. But in order to actually get anything meaningful out of it, we need that. (LG).

[If it were law] then there would be fines […]. There would be actual consequences there for the institution. (4/405)

Tying it to funding is great, but that means that only organizations who get funding have to implement it. (3/406)

Attendees argued that a policy that applies only to federally funded work and lacks legal force risks becoming symbolic rather than substantive. This reinforces uneven standards and inconsistent implementation across the research landscape. Participants also pointed out that in limiting the policy’s scope to human agents, excluding animal and plant pathogens, policymakers seriously constrained its effectiveness and left a significant hostage to fortune. As one participant noted, “it’s all human-focused and human-centric,” in contrast to “the alleged vision that we have of One Health” (3/405).

Predicting risk

Participants further raised what we might call fundamental challenges to the policy, questioning the possibility of its effectiveness based on the inherent difficulties in identifying risks in advance. In part, this reflects a kind of nihilism, based on the arguable pointlessness of trying to predict what might happen, or to identify which of an infinite array of possibilities might turn out to be a problem: “I feel like we risk assess the heck out of what could be until, like, a plane crashes into the building, right, and so not that you can always predict” (1/406).

In relation to DURC, the breadth of research that could potentially be misapplied is huge. It could include basic research; research that does not involve pathogens or select agents and research that is, on its face, entirely and obviously beneficial. Given this, any attempt to define or delimit types of research that should be subject to the policy would inevitably exclude something that could pose a problem – yet it is also simply not practical to identify and manage every possible risk. Again, this can lead to a kind of nihilism, leading some participants to question (at least rhetorically) the point of any attempt to identify or mitigate risks: “There’s so many things we could be concerned about, like, does any of it even matter?” (2/406).

Relatedly, participants raised the point that science is always ahead of policy, by definition, posing particular challenges in managing emerging risks (as also discussed in relation to lack of clarity, and the pros/cons of more definition):

Participant 1: When they put this out originally, they had the 15 [agents], and then later on they learned, wait a minute, there are others that are in this 15, right? So then they came up with the PPP, right? And now they have come up with the ePPP to hopefully capture [everything else] […] they are trying to make sure that […] they are throwing out a net broad enough to capture everything, but the whole thing is that what they are running behind, they are always behind the eight ball in this situation, is technology. Technology’s moving at such a rapid pace right now that they are always still, always lagging, yeah.

Participant 2: It’s always reactionary. (1/405)

I frankly do not find the subset of pandemic potential pathogens to be very helpful to me, because it’s highly speculative, and it builds upon a real nebulousness of where the state of science is, and you do not necessarily have a map of, if you conduct X experiment, you have a reasonable certainty, Y is going to happen. You have to do it, and then you have to replicate it, and then you have to try it again to see if there’s actually a there there. And I think that what this effectively does is it hinders our ability to gain scientific knowledge at the expense of, I’m really not sure what security considerations. It does not seem like a really good trade-off for me (3/405).

Efforts to expand definitions or tighten controls in response to emerging risks only reinforce a cycle of reactivity, which could stifle innovation without effectively mitigating future threats.

Participants described the policy’s lack of legal standing and its narrow focus on federally funded, human-centered research as major weaknesses. Without enforceable authority and broader applicability, they feared the policy could create loopholes and inconsistent protections, potentially undermining its goals. These limitations raised doubts about whether the policy could meaningfully address the complex and evolving risks posed by high-consequence research in today’s interconnected world. These concerns about the policy’s legal status and narrow reach naturally extended to its relevance and impact on the global stage.

International context

Participants pointed out that biosecurity is “not a boundaryless problem” (LG), posing a fundamental challenge to the effectiveness of any national policy in this area. Although at least one participant argued for the United States “set[ting] the example” globally, it was recognized that “we need to involve other countries” – “it should be an international effort to demonstrate this is not just a U.S.-based risk” (LG).

Thus, the lack of a global approach actually disadvantages the United States, posing risks not just to the national science base, but to national security itself. Although participants flagged the need for an international approach, this should be understood as a globally harmonized regime, rather than a “one-size-fits-all” policy:

I do not think that the list of agents that are considered for U.S. should be the list of agents that necessarily should be applied to other countries in terms of agents for concern for a variety of reasons. Well, if they are endemic, they are already [present], right? Or things that we do not consider dual use risk will be dual use risk. They are because of different climate, crops, environment, all of those things. (1/405).

Finally, although the workshop discussion touched on the desirability of international policy in this area, participants were also cognizant of the challenges of international policymaking:

Participant 1: It would be nice to see instead of […] a White House [policy] […] something pushed through the U.N. eventually, try to at least make an effort to see an international policy that everyone’s voting by […].

Participant 2: Like, we are very focused on the U.S. here. It’s like, what’s actually happening around the world would be an interesting conversation, wouldn’t it? […].

Participant 3: You think the U.S. is a mess? Talk to me about how the U.N. works with these types of policies […] Twelve years into this environment of conversation about a policy, and there are no further language barriers, right?

Participant 4: It’s just basically rehashing the same details over and over and over again. (LG)

Participants saw global coordination as essential in principle but nearly impossible in practice, given the political divisions and procedural stagnation that characterized current international governance.

These discussions reflect the deep and varied concerns that biosafety professionals and other practitioners held about the 2024 DURC/PEPP policy. Their insights revealed not only the challenges of implementation but also the broader tensions between security, scientific progress and practical feasibility. These findings point toward critical opportunities for improvement in future policies.

Conclusion

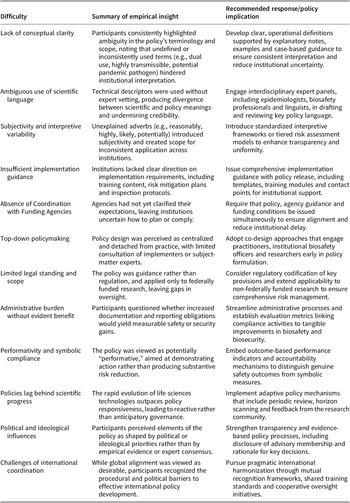

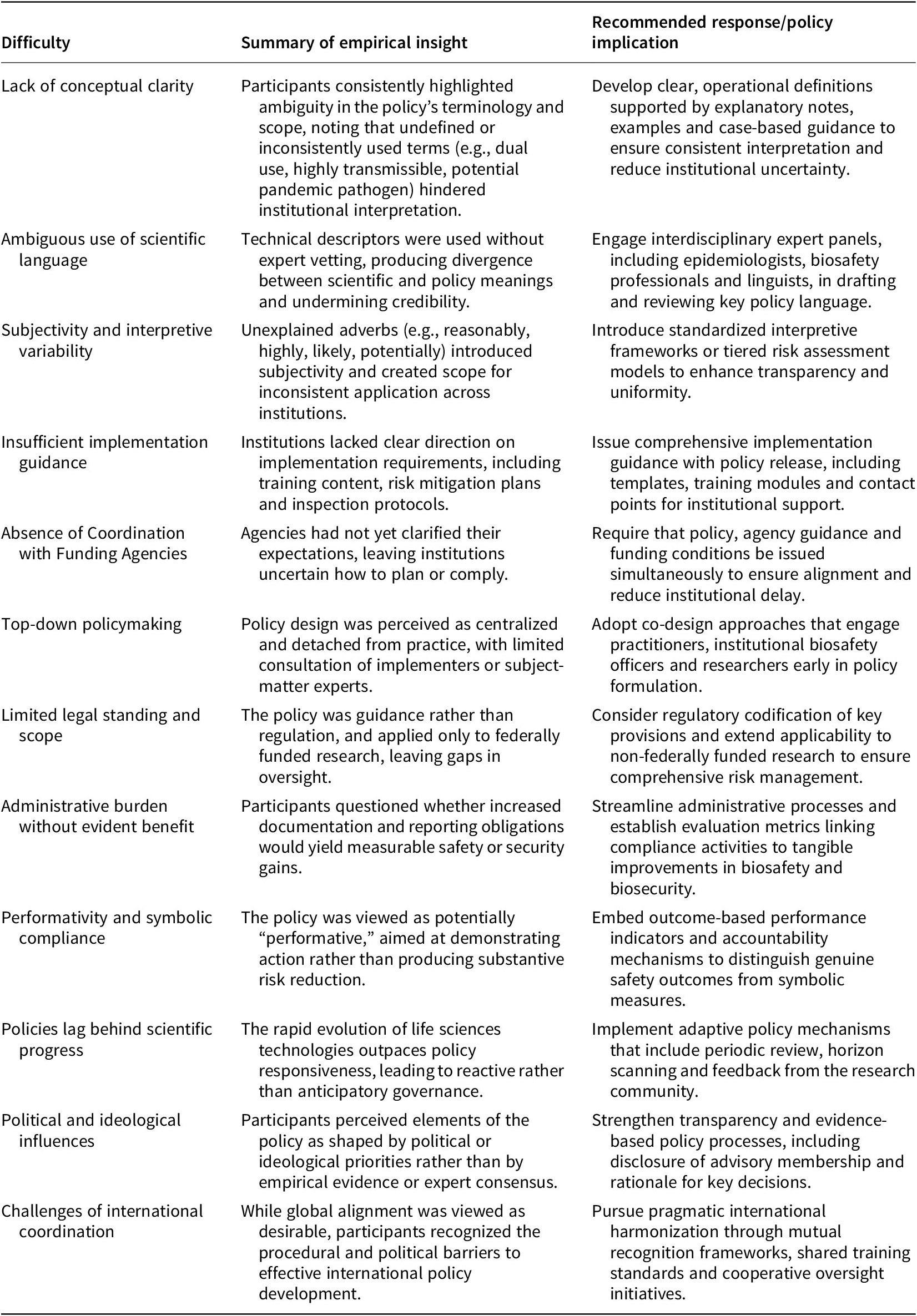

While participants broadly supported the 2024 DURC/PEPP policy’s ambition to protect public health and strengthen biosecurity, they identified shortcomings in its clarity, specificity, practical guidance, legal authority and international applicability. As discussed in the sections on Lack of Clarity, Lack of Specificity and Lack of Guidance (and summarized in Table 1), these deficiencies undermined the policy’s potential effectiveness and could have unintentionally incentivized researchers to relocate high-consequence studies to jurisdictions with weaker oversight, ultimately jeopardizing global safety and security. These concerns were further exacerbated by the NIH notice regarding its implementation of the framework without clear guidance provided to the research community or those responsible for implementation of the framework at the local level (National Institutes of Health, 2025).

Table 1. Key challenges identified in the 2024 DURC/PEPP policy and recommended responses

This table includes themes from workshop discussions and integrates participant insights with analytical interpretation to identify both structural and operational challenges and corresponding solutions. The recommendations are intended to inform policymakers, funding agencies and research institutions seeking to improve dual use research oversight in practice.

Building on the Wider Critique section (and summarized in Table 1), participants emphasized that many of these challenges stemmed from a top-down policy design process that did not incorporate practitioner expertise. Their concerns, ranging from definitional ambiguity to institutional feasibility, describe the challenges that arise when governance is developed without meaningful engagement from those expected to implement it. Participants called for consistent terminology, clearer expectations and two-way communication with policymakers. There was also consensus that biosafety professionals must have a seat at the table during policy development if such frameworks are to succeed in practice.

This research highlights the need for DURC and PEPP oversight frameworks that are evidence-informed, ethically grounded and operationally feasible for those tasked with implementation. Moving forward, policymakers should prioritize more precise definitions, actionable guidance and sustained engagement with biosafety practitioners to ensure that oversight frameworks are realistic, practical and globally harmonized (Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Vogel and Brock2023; Warmbrod et al., Reference Warmbrod, Cole, Sharkey, Sengupta, Connell, Casagrande and Delarosa2021). Inclusive governance development that engages practitioners as epistemic partners is essential to building oversight systems that are legitimate, sustainable and make sense on the ground. By meaningfully involving those responsible for implementing these policies on the ground, future frameworks will be better positioned to balance protective aims with the demands of responsible, innovative research.