Introduction

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also referred to as ‘female genital cutting’ or ‘female circumcision’, is a traditional and harmful practice that involves ‘the partial or total removal of external female genitalia or other injury to female genital organs for non-medical reasons’ (World Health Organisation, 2024). The practice is an embedded social norm in cultures across over 30 countries in Africa as well as in parts of the Middle East and South East Asia.

It is estimated that more than 200 million girls and women alive today have undergone female genital mutilation in the countries where the practice is concentrated. The practice is recognised internationally as a violation of human rights of girls and women and as an extreme form of sex discrimination, reflecting deep-rooted inequality between the sexes.

The World Health Organisation classification (World Health Organisation, 2024) defines four broad categories of FGM depending on which part(s) of a girl’s or woman’s vulva or vagina is affected. Types 1, 2 and 3 involve cutting/removal of parts of the external genitals including the clitoris and in type 3 (the most anatomically severe), the cut labia are sewn together to create a covering seal over the vaginal orifice. There are no health benefits to FGM. Severity and health risks are closely related to the type of FGM performed as well as the amount of tissue that is cut. It can lead to immediate health issues, as well as long-term complications for the person, including chronic pain, infections, urinary problems, menstrual problems, sexual difficulties, birth complications and psychological problems (Reisel and Creighton, Reference Reisel and Creighton2015).

There is limited research into the psychological effects of FGM. One study assessing the mental health of 47 Senegalese women found that over 30% suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to their FGM (Behrendt and Moritz, Reference Behrendt and Moritz2005). Studies suggest that when comparing women with and without FGM, those women with FGM have higher rates of psychological complications such as anxiety, depression and PTSD (Behrendt and Moritz, Reference Behrendt and Moritz2005; Köbach et al., Reference Köbach, Ruf-Leuschner and Elbert2018). Although there are few studies focusing on the role, extent and circumstances of cutting, it is evident that it can lead to adverse psychological effects (Mulongo et al., Reference Mulongo, Hollins Martin and McAndrew2014).

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a disorder associated with stress that may develop following ‘exposure to an extremely threatening or horrific event or series of events’ (ICD-11; World Health Organisation, 2019/2021). Three core elements need to be present to meet a diagnosis of PTSD: (1) re-experiencing of the traumatic event(s), which can include vivid, intrusive memories, flashbacks and nightmares, and can be experienced in any sensory modality. The re-experiencing feels as if it is occurring again, in the here and now and is usually accompanied by strong, overwhelming negative emotions and/or physical sensations; (2) deliberate avoidance of thoughts, memories, activities, situations or people who are reminiscent of the event(s); (3) a persistent perception of heightened current threat such as hypervigilance or enhanced startle response to unexpected noises. Symptoms should persist for several weeks and cause significant impairment in functioning before a diagnosis can be made (ICD-11; World Health Organisation, 2019/2021). Undergoing FGM would meet the event criterion for a diagnosis of PTSD and research suggests that experiencing the more severe forms of FGM (types 2 and 3) can lead to higher levels of mental health symptoms (Köbach et al., Reference Köbach, Ruf-Leuschner and Elbert2018).

Information on refugees/asylum seekers

With migration, forced or voluntary, there are many women and girls who have undergone FGM living in diaspora communities worldwide. Therefore this form of sex-based violence is likely to be more prevalent in psychological practice than perhaps previously appreciated. Women and girls who have undergone forced migration are a particularly vulnerable group and may have lived experience of this and other forms of sexual, physical and emotional abuses. The Refugee Convention defines a refugee as someone who is ‘unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of particular social group, or political opinion’ (The UN Refugee Agency, 2020).

The number of asylum seekers and refugees in the United Kingdom is rising as people flee conflict and discrimination in their country of origin, in the hope of finding safety in the UK. In the year ending 2023, the UK received over 67,000 asylum applications (Home Office, 2024). People flee their country of origin for many different reasons including persecution for political beliefs and actions, personal reasons, such as gender or sexuality, trafficking, modern slavery and war (Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe2015). Many are subjected to violent inhumane experiences, such as torture, rape, sexual assault, FGM, ethnic cleansing and other horrors of war (Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe2015; Kalt et al., Reference Kalt, Hossain, Kiss and Zimmerman2013).

Research suggests that asylum seekers and refugees are more likely to experience difficulties with their mental health when compared with the local population (Tribe, Reference Tribe2002); these include depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. In addition, rates of PTSD are higher in survivors of human trafficking and refugees, than in migrants who are not forcibly displaced (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities 2022).

A recent review of the literature on rates of PTSD in refugees suggested a prevalence of 31% (Blackmore et al., Reference Blackmore, Boyle, Fazel, Ranasinha, Gray, Fitzgerald, Misso and Gibson-Helm2020), which is much higher than in the general population. There is little research looking at rates of PTSD in women with FGM and results vary, from no significant difference with matched controls to 44% (Mulongo et al., Reference Mulongo, Hollins Martin and McAndrew2014).

Being aware of, and working with, cultural differences is vitally important when treating refugees, as outcomes are better when the patient’s values are brought to therapy (Semmlinger and Ehring, Reference Semmlinger and Ehring2022). It may be essential to use interpreters when working with patients whose first language is not English; however, clinicians can feel encouraged by research that suggests that outcomes are the same when working with, or without, interpreters (Lambert and Alhassoon, Reference Lambert and Alhassoon2015).

Imagery rescripting

This case study used imagery rescripting (ImRs) as it is a particularly good intervention for addressing many different traumatic events in a relatively short space of time. ImRs was developed from Smucker et al.’s (Reference Smucker, Dancu, Foa and Niederee1995) protocol by Arnoud Arntz for use with adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. ImRs is a technique used to alter the meaning and emotions associated with a distressing memory, thereby reducing unwanted intrusions. This involves the patient imagining the start of the traumatic memory and then, with the therapist’s help, rewriting it with a safer ending. Patients can experience in fantasy what they needed while in the traumatic situation, so that any unmet needs are discovered and met using the imagery (Arntz, Reference Arntz, Thoma and McKay2015). ImRs has been proven effective in reducing PTSD symptoms (e.g. Arntz et al., Reference Arntz, Tiesema and Kindt2007; Hackman, Reference Hackman2011; Smucker et al., Reference Smucker, Dancu, Foa and Niederee1995).

A more recent meta-analysis (Morina et al., Reference Morina, Lancee and Arntz2017) included eight trials that used imagery rescripting with patients with PTSD. It showed that ImRs demonstrated large effect sizes obtained in a small number of sessions (mean number of sessions was only 4.5). It has also been shown to be effective in treating complicated PTSD in refugees (Arntz et al., Reference Arntz, Sofi and van Breukelen2013; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Young, Akbar, Chessell, Stevens, Vann and Arntz2023). The other main evidence-based treatment for PTSD following multiple traumatic events, Narrative Exposure Therapy, reports smaller effects sizes (Siehl et al., Reference Siehl, Robjant and Crombach2020). ImRs is therefore a particularly good intervention for addressing many different traumatic events in a relatively short space of time, and would be useful for our participant ‘Grace’ with her long history of trauma. ImRs is also considered a particularly effective form of therapy for patients with little or no education, as it is relatively language-free and, as patients use their own ideas for the rescripts, it is culturally appropriate (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Young, Akbar, Chessell, Stevens, Vann and Arntz2023). The meta-analysis also showed that ImRs has high acceptability for patient and therapist as it is perceived as a less stressful treatment compared with exposure with no ImRs.

The Rose Clinic, Oxford

This work was conducted in the Rose Clinic, which is based in a teaching hospital in Oxford. This specialist clinic was founded by a consultant obstetrician, and holistically supports pregnant and non-pregnant women and girls with FGM. The multi-disciplinary team additionally includes a sexual health doctor, a clinical psychologist and midwives. The medical doctors see and assess all new patients with referral to the team’s psychologist when indicated. There is capacity in the clinical service for clinicians to undertake joint assessments, for example if referral (self or through health, social care, or education) suggests significant psychological concerns. There is access to interpreters in person, or via telephone or video call.

Presenting problem

Grace (pseudonym) was a 58-year-old asylum seeker from Africa who was referred to the Rose Clinic by a local asylum charity in February 2020. Details have been anonymised to maintain the patient’s confidentiality. Grace gave her consent for this case study to be published as she was keen for other women with FGM to be helped. She had been trafficked to the UK in 2017, and had been forced to work in offices and to undertake childcare. Her psychological symptoms included re-experiencing the FGM and sexual and physical abuse from numerous events spanning more than 40 years. From the referral, it seemed likely that Grace might have medical and psychological needs, so an initial joint assessment was arranged with the obstetrician and the clinical psychologist. Grace spoke English, so an interpreter was not needed.

History

Grace had grown up in a large family in a village in Africa with a loving mother and three sisters. At the age of 14, she was introduced to an older man in his 40s and told that she had to marry him and go with him to his home that same day. They drove for many hours and when they arrived, he raped her for the first time. Grace was not allowed to leave the compound where they lived and was locked in at night. Grace was subjected to sexual, physical and emotional abuse by the older man for the next 25 years until she was 40 years old. Then the man joined a religious sect that allowed members to rape each other’s wives. Grace was then subjected to multiple rapes and physical assaults by different men over the next few years. When she was 56, the group members decided that she needed to be cut and subjected her to FGM. When she had recovered sufficiently to be able to walk, Grace stole some money and escaped the compound to walk to the nearest large city. There, she was befriended by a man who told her he would help her get to the UK. She gave him her money and he arranged for a passport and aeroplane ticket. When Grace arrived in the UK, she was met by another man who said she owed them money for the plane ticket and passport. He took her to a house where she was told to look after the children during the day and clean offices at night, in order to repay the money for the journey to the UK. She had no idea where she was living and had no freedom or wages. After about 18 months she was taken in a van and driven for about two hours and left in a churchyard. As she was crying on a bench, a woman came out of the church and offered to help her. She was taken to the woman’s home and introduced to a local asylum charity who referred her to the Rose Clinic. When we first met, Grace was living with the woman, but did not know anyone else, nor did she have any support system in place. Grace had recently applied for asylum in the UK when we met her.

Assessment

At assessment, Grace met the ICD-11 diagnostic criteria for PTSD (ICD-11; World Health Organisation, 2019/2021). She had been exposed to many years of prolonged and repetitive, threatening and horrific events where escape was impossible. She also presented with the three core symptoms of PTSD:

-

(1) Re-experiencing. Grace said that she had vivid intrusive memories of the FGM and the physical and sexual abuse. She had nightmares and dissociative flashbacks that felt as if she was experiencing these events again in the present day.

-

(2) She avoided thinking about the traumatic events and went out of her way to avoid any men and other reminders that might trigger flashbacks.

-

(3) She felt a persistent sense of heightened current threat, where she was constantly on the lookout for danger and felt ‘very jumpy’.

In addition, she believed that she smelled and was permanently contaminated due to the rapes and sexual assaults.

Working with people with complex, lengthy and complicated abusive histories can feel overwhelming initially. It can be difficult to know where to start. NHS guidance states that unstable circumstances or unresolved asylum claims, ‘should not automatically exclude patients from being treated in NHS Talking Therapy services’ (p. 14; NHS England, 2024), rather the decision about whether a patient can, and wants to undertake trauma-focused therapies in these circumstances should be made with the patient, on a case-by-case basis and following a discussion with them about their goals, priorities and the competing demands upon them. When someone has PTSD to multiple traumatic events, it is important to establish what events are being re-experienced (Murray and El-Leithy, Reference Murray and El-Leithy2022). Because of Grace’s complex and lengthy history of abuse, a lifeline was used to help with the assessment and chronology of her traumas. Grace listed the significant events in her life, both positive and negative, in chronological order.

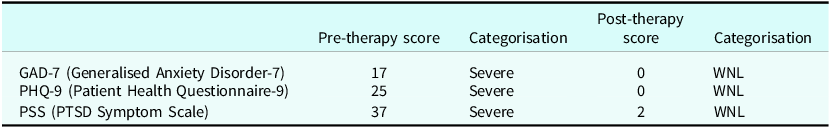

Once the lifeline was completed, Grace was asked to show which events she re-experienced in order to understand which traumatic events would need to be targeted in treatment. NHS England guidance says that it is not so much the number of traumatic events, but the number the person re-experiences, and how different these are from each other, that matter in treatment planning (NHS England, 2024). Standardised screening measures were also used at assessment and confirmed severe levels of symptoms on the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) and the PTSD Symptom Scale (PSS; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Riggs, Dancu and Rothbaum1993).

Grace was asked to keep an intrusion diary detailing her re-experienced symptoms at the start of her treatment, which was used to double check which traumatic events were still being re-experienced and to gauge any progress. At the start of therapy, she was experiencing between eight and 15 intrusions a day.

During the assessment, because she had been assaulted and raped, Grace was asked if she felt contaminated. She responded that she felt 100% dirty and contaminated. The therapist explained to Grace that there was a powerful and quick evidence-based treatment protocol that has been shown to reduce feelings of being contaminated and reduce PTSD symptoms in only two sessions (Jung and Steil, Reference Jung and Steil2013). The protocol is called cognitive restructuring and imagery modification, or CRIM. If it was possible to help Grace reduce her feelings of being contaminated within the two-session protocol, this could help foster trust and confidence in the therapeutic model and the therapist. This could be particularly useful for someone for whom trust might be an issue. Grace was keen to start work on her feelings of being contaminated first, and then move onto her intrusions.

Course of therapy

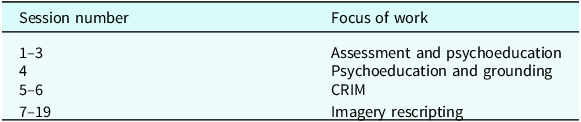

Grace presented with a complex and complicated history of abuse and trauma lasting over 40 years. Because of the large number of re-experienced events, there was a concern that there would not be time to do cognitive therapy for PTSD to each event and therefore, as discussed earlier, an imagery rescripting approach was thought to be beneficial. In addition, Steel et al. (Reference Steel, Young, Akbar, Chessell, Stevens, Vann and Arntz2023) demonstrated that ImRs is an effective treatment for PTSD with refugees and asylum seekers being treated within the NHS. Grace’s treatment began with psychoeducation about PTSD and information about managing dissociation, then moved onto the two-session treatment for Grace’s feelings of being contaminated using Jung and Steil’s (Reference Jung and Steil2013) CRIM protocol. Finally, imagery rescripting was used to work through her extensive list of re-experienced events (Arntz, Reference Arntz, Thoma and McKay2015). See Table 1 for an overall map of therapy.

Table 1. Map of therapy showing the number of sessions and the focus of the work

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation was initially given to explain what PTSD was, why she was experiencing the symptoms, and how the treatment could help. It was important to give a good rationale for undertaking the work, as the treatment would involve discussing the rapes, abuse and FGM in detail and over some weeks and months. It was crucial that Grace understood the process, agreed with the rationale and ‘signed up’ to doing the therapy, so that the therapist did not feel they were coercing her to talk about the most difficult things in her life against her will. The linen cupboard metaphor (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) was used to help with the psychoeducation. See Young et al. (Reference Young, Akbar, Brady, Chessell, Chisholm, Dixon, Raven Ellison, Grey, Hall, Khan, Lee, Michael, Paton, Penny, Roberts, Rouf, Said, Soubra, Steel, Stich, Vann, Wells and Bartholdy2025) for a comprehensive explanation of the linen cupboard metaphor.

Dissociation

During the assessment, there were times when Grace stopped talking, shut her eyes and became very still while silently crying. This was a sign of dissociation, so it was important to discuss dissociation with Grace; what it is, how it impacts on trauma memories, and how best to manage it. Dissociation is an automatic response to inescapable trauma. The 6F Defence Cascade is a useful way to conceptualise dissociation for patients, whereby there is a continuum of automatic, survival-based behaviours, activated in response to danger or perception of danger. It starts with freeze, flight, fight, then moves onto fright, flag and ends with faint (Chessell et al., Reference Chessell, Brady, Akbar, Stevens and Young2019; Schauer and Elbert, Reference Schauer and Elbert2010). When confronted with a traumatic event, the brain decides how to keep you safe by going through the six different survival behaviours. See Murray and El-Leithy (Reference Murray and El-Leithy2022) and Chessell et al. (Reference Chessell, Brady, Akbar, Stevens and Young2019) for more comprehensive explanations of dissociation. It was explained to Grace that dissociation is when patients temporarily lose awareness of their surroundings, zone out, feel helpless and can feel detached from their bodies. Not all patients dissociate during their traumas, especially if the traumatic event is short and they have been able to fight back or run away. However, in more prolonged traumas, when patients are unable to save themselves, they can automatically start to dissociate. If someone dissociated while in the traumatic situation, they are likely to dissociate again when having flashbacks to that trauma in the present day (Chessell et al., Reference Chessell, Brady, Akbar, Stevens and Young2019).

One of the most important things to note, both for therapists and patients, is that dissociation is not necessarily dangerous or particularly worrying, but is an understandable and automatic response when confronted by extremely dangerous, inescapable situations. It is a way for our bodies to try to protect ourselves and is a hard-wired protective response, rather than a conscious choice. Normalising the experience for patients can be important to help them realise that they had no choice not to fight back or run away when in a traumatic situation.

Grounding

Grounding was introduced as a way to help Grace bring her attention back to the present day and to help with dissociation. Grounding items need to be easily accessible and attention-grabbing in order to counteract any intrusive memories quickly and easily. It can be useful to find grounding strategies in all the sensory modalities to which the patient has intrusions (Murray and El-Leithy, Reference Murray and El-Leithy2022; Chessell et al., Reference Chessell, Brady, Akbar, Stevens and Young2019) so, for example, if they feel pinned down, the grounding strategy can be to move their arms vigorously, or walk around the room. If they get taste intrusions, then the grounding strategy to counteract these could be sucking a sweet or mint. For a more comprehensive discussion, please see Chessell et al. (Reference Chessell, Brady, Akbar, Stevens and Young2019) and Young et al. (Reference Young, Akbar, Brady, Chessell, Chisholm, Dixon, Raven Ellison, Grey, Hall, Khan, Lee, Michael, Paton, Penny, Roberts, Rouf, Said, Soubra, Steel, Stich, Vann, Wells and Bartholdy2025).

After discussion and exploration, Grace chose a eucalyptus essential oil that reminded her of happy memories of her childhood and some strong mints to suck that helped to counteract the taste flashbacks she regularly experienced. She also found it helpful to stroke a soft piece of blanket placed over her lap to remind her that there was no pain in her genitals in the present day. Having discussed dissociation, Grace said that she would like us to tap her on the hand and call her name loudly if she dissociated during their sessions. Grace could use the grounding items to help keep her in the ‘here and now’ when confronted by triggers both in therapy and at home/in the community.

Feelings of being contaminated

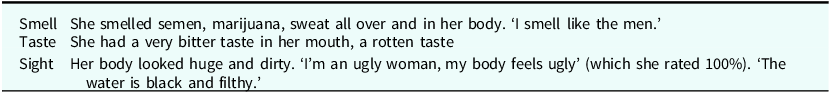

Grace said that she felt 100% contaminated all the time, she felt dirty and could smell the men who assaulted her all over her body. She washed herself frequently to try to get rid of the smell, but nothing worked which added to her belief that she was permanently changed since the abuse. After washing her body, she had to wash her hands to try to get the contamination off her hands. In addition, Grace would wash her mouth and nose out with water several times a day, but the water that she spat out continued to look black to her.

Grace believed that other people could smell her, so she tried never to get physically close to people. However much she washed or cleaned herself, she was not able to get rid of her feelings of being contaminated (see Table 2).

Table 2. Grace’s re-experiencing symptoms to feeling contaminated in different senses

Jung and Steil’s (Reference Jung and Steil2013) two-session CRIM protocol was used. Their initial trial consisted of 34 women who had PTSD to childhood sexual abuse, although it works well with other types of contamination trauma too, for example to the smell of dead bodies, or burning (Murray and El-Leithy, Reference Murray and El-Leithy2022).

Initially Grace was asked to colour in a picture of a human body detailing the areas where she felt dirty. She coloured in the mouth, nose, vulva and stomach (see Fig. 1). The therapist checked whether the stomach meant outside on her skin, or inside her body. Grace said the contamination was outside on the skin of her stomach. Had she said that it was inside her body, we would have suggested using a different coloured pen to denote this, but rescripting feelings of contamination inside or outside the body would be the same. Visual representations of patients’ feelings of being contaminated can be helpful as felt senses can be hard to describe verbally and pictorial representations can be particularly helpful when working through interpreters.

Figure 1. Parts of her body that Grace felt were contaminated before using CRIM.

The next part of the Jung and Steil (Reference Jung and Steil2013) protocol was to provide psychoeducation about how dermal cells rebuild themselves every few days. The therapist said the following:

‘Have you ever noticed that the dry skin on your elbows and feet flakes off? Well, this is part of a process that all skin cells go through. The top layer of human skin dies and is replaced by a new layer underneath. The same thing happens for all cells in every part of your body, both internally and externally – your mouth, nose, arms, legs, vagina, stomach, anus and all your internal organs.’

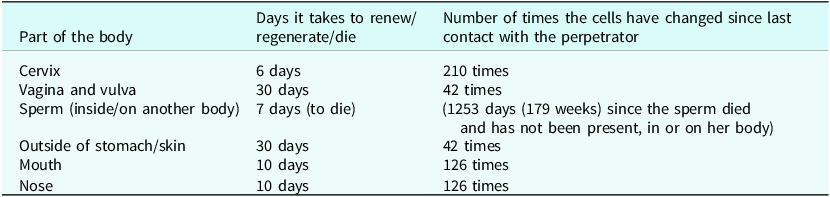

Grace did not know that cells all over the body are constantly dying off and renewing at different rates. The therapist and Grace looked up the different areas where Grace felt contaminated and discovered information about how many days it takes for the skin to turn over and renew in different areas of the body.

So Grace learned that all cells in the body are constantly dying and rebuilding themselves at different rates. She was surprised and pleased to learn this information. The next step was for the therapist and patient to work out together how many times the cells in each part of Grace’s body had changed since the last time she was raped or abused. Table 3 shows Grace’s information.

Table 3. How many days it takes for cells to renew/regenerate/die in different parts of the body and the number of times those cells have changed for Grace since last contact with the perpetrators

This new information was discussed with Grace. She said she was amazed and relieved that none of the cells currently in her body had been in contact with the perpetrators. At the end of this session of CRIM, Grace said that she believed she was clean, ‘I feel so different, it’s not like before, I feel clean’. However, although she knew the facts that none of the perpetrators’ cells could still be on her body, it was helpful to use imagery to embed this knowledge emotionally and transfer the information ‘from the head to the heart’ (Jung and Steil, Reference Jung and Steil2013). Creating an image helps the person move from knowing they are no longer contaminated, to feeling they are not contaminated. At the beginning of the next session, Grace said that her feelings of being contaminated had got a bit better and she enjoyed knowing that none of the mens’ cells could be on her body. Grace was then asked to come up with an image that embodied this new knowledge. Grace said that she was standing in a shower and the sparkly, bright water was washing away all the contamination. We spent some time enhancing and enriching this image using all the senses. While Grace was describing the image of being in a cleansing shower, it was possible to see her relax and enjoy the image. Once the image felt strong and meaningful, Grace was asked to recall a recent occasion when she had felt contaminated at a moderate level. She was then guided to use her new cleansing image to counteract the contamination imagery. At the end of this session Grace said that she felt 100% clean. She also said she was beautiful and not smelly, and believed this 70%. We established that the cleansing image worked to help her feel clean, so we recorded it and Grace was asked to listen to it daily throughout the week before the next session. At the beginning of the next session, Grace said she still felt 100% clean and when she gargled with water, the water she spat out was now clean and she did not need to wash her nose out anymore. The therapist asked her to draw on a picture where she felt contaminated now. She said there were now no areas of contamination, so nothing was drawn on the figure.

Further information can be found in Young et al. (Reference Young, Akbar, Brady, Chessell, Chisholm, Dixon, Raven Ellison, Grey, Hall, Khan, Lee, Michael, Paton, Penny, Roberts, Rouf, Said, Soubra, Steel, Stich, Vann, Wells and Bartholdy2025). The links below are a series of short videos made by two of the authors to demonstrate the Jung and Steil (Reference Jung and Steil2013) protocol. These demonstrations were unscripted and an attempt to capture a real-time approach to consultations, rather than present a ‘perfect’ encounter.

How to do CRIM: https://vimeo.com/814947339 .

Characterise the feelings of being contaminated and do research for the clean image: https://vimeo.com/559650949/10c5670236 .

Generate clean image: https://vimeo.com/559653045/938c041f17 .

Swap in clean image: https://vimeo.com/559649927/acdb5a0ad9

Imagery rescripting – working on Grace’s intrusive traumatic memories

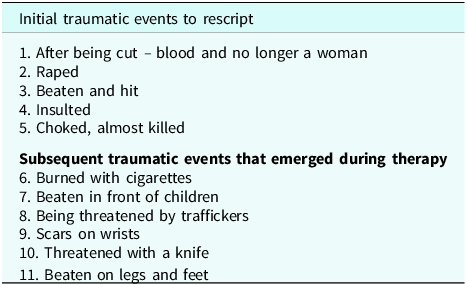

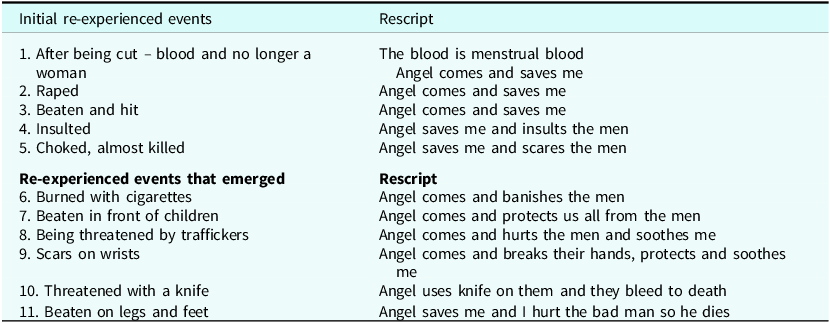

Within the ImRs paradigm, the therapist and patient generate a list of traumatic events to rescript. Generally speaking, patients are encouraged to pick traumatic events that are currently re-experienced. Grace and the therapist made an initial list; see Table 4. She placed these in order with the one she wanted to work on first at the top, and then the second one and so on. Grace chose to work on the experience of FGM first.

Table 4. Initial list of traumatic events to rescript and subsequent events that emerged during therapy

As therapy progressed, Grace revealed new re-experiencing symptoms (Table 4), which led the therapy to target further traumatic events. It is common throughout therapy that the order of events might change and new events emerge. In this way it is a very collaborative and dynamic process involving reviewing and re-ordering treatment targets each week (Arntz, Reference Arntz, Thoma and McKay2015).

As Arntz (Reference Arntz, Thoma and McKay2015) discusses, ‘the basic idea of ImRs is to activate the trauma memory and imagine a different ending that better matches the needs of the patient’. Initially, Grace was given an explanation of the ImRs procedure. Arntz lists the important parts of the explanation as the following:

-

Imagery is a more powerful way to change traumatic memories and the meaning/emotions attached to them, than talking. We know from brain research that the brain responds in almost the same way to imagined events as to real events – even when the person knows the event is imagined.

-

During a traumatic event, various needs, emotions, and actions are naturally triggered, but they often cannot be fully expressed because it is either impossible or too dangerous. It can be healing to imagine these emotions being expressed, actions carried out and needs met. We cannot change what happened to the patient, although we would like to, but we can change how they feel when they remember it, so that it does not affect them so much. The impact is much stronger when we imagine these responses occurring within the context of the actual trauma rather than just discussing them. The patient may know that they are safe now, and their head understands this, but their heart and body do not. The best way to move the knowledge from their head to heart and body is by using imagery.

-

ImRs does not create new memories, but the cognitive and emotional processing of the event leads to a reduction of vividness of the memory, changes its meaning and reduces the fear within the memory which leads to reduced intrusions and nightmares.

-

The patient can imagine all kinds of changes in the script as long as the rescript meets their needs. The changes do not have to be real or possible, as long as they are experienced as satisfying the patient’s needs and having a powerful impact.

-

At the end of each rescript, the therapist needs to check that all the patient’s needs in that moment have been met. If not, then new scripts can be tried out, or altered until all the needs have been met.

-

The therapist encourages the patient to notice what happens to that memory over the week and if possible, to try to ‘glue on’ the rescript if the bad memory occurs spontaneously.

Grace wanted to start with the cutting (FGM) as this was her worst intrusion, which she re-experienced many times a week. We discussed beforehand what she would have liked to happen, what she would have needed in that moment, so she would be prepared for the question while imagining the trauma. She was asked to bring the event to mind and describe it in detail using all her senses to describe her emotions, physiological response and cognitions. When the therapist could see that her distress level was raised, the therapist asked, ‘What do you need now?’. Grace said that she now realised that all the blood was normal menstrual blood, that she had not been cut, but was just having a bad period and that the pain she was experiencing was just severe period pain. Her level of affect reduced a bit, but Grace struggled to ‘flesh out’ this rescript when asked for more details. We stopped the rescript and discussed what else she might have needed in that moment.

At this point, Grace said that she needed to be rescued before the cutting happened, rather than rescript the aftermath. With some gentle prompting about who or what could rescue her, she then described a beautiful, powerful, female angel who smiled at her with warmth and kindness. The angel was tall and strong and was not afraid of the bad men who cut her. Within the imagery rescripting the angel appeared before Grace was cut and banished the men who were taken away by the police. The angel then tended to Grace’s bruises and looked after her.

During the rescript the therapist observed Grace’s affect diminish significantly once the angel appeared. Grace’s body relaxed and she appeared relieved and calm. Grace was able to describe the image in detail using all her senses and found it calming and supportive. When Grace said that she felt safe and looked after, the rescript was stopped. On discussion, Grace said she really liked the angel appearing when she needed her and banishing the bad men. It is very common to try out one or more rescripts in the session until you find one that works. With this in mind, each rescript should be approached in a very experimental and curious way.

At the next session, Grace said she had not had any re-experiencing symptoms to the FGM. She was amazed and delighted and keen to move on to a different memory. Grace said that she wanted to work on her re-experienced symptoms of rape. As she had been raped innumerable times over the years, she was asked if there was a particular occasion that intruded, or if there was a typical event that she wanted to work on. She said the intrusive memories of rapes that she re-experienced did not relate to any one event but were a combination/amalgam of different rapes. This is quite common with survivors of multiple traumatic events that are quite similar. In our clinical experience, working with whatever is re-experienced, regardless of where it comes from, will still be effective. When asked what she would have needed at the time, Grace replied that she wanted her angel to save her before she was raped. We completed the rescripting as before, using her angel. The therapist could see Grace relax once the angel arrived.

Over the next few sessions, each event listed by Grace was worked through using the image of this angel to save her. The further down the list, the quicker it became for Grace to rescript it. When each event had been rescripted once, Grace largely stopped having intrusions to that event. See Table 5 for information on the different re-experienced events and the rescripts that were used.

Table 5. Grace’s initial re-experienced events and rescripts, and the events and rescripts that emerged during therapy

It was interesting to note how Grace’s choice of rescript changed over the course of the therapy. She started by having the bad men taken away by the police, but as therapy progressed, she changed it so that the angel starts to hurt them and at the end of the work, her rescript involved her hurting them and killing them, ‘so they could not hurt any other person ever again’. It was possible to notice Grace enjoying hurting the men within her rescript, she smiled and said she felt powerful. Seebauer et al. (Reference Seebauer, Froß, Dubaschny, Schönberger and Jacob2014) explored whether it was dangerous to fantasise revenge in imagery rescripting and concluded that it was not risky as using violent rescripts did not lead to an increase in aggressive emotions in participants. Our experience is that exacting revenge on violent perpetrators can be an incredibly powerful part of imagery rescripting, and being able to express your anger within the imagery almost always diminishes it.

Example of films demonstrating ImRs to domestic violence

These films were made unscripted and are not flawless but represent a ‘good enough’ attempt to show the reader how to undertake this treatment.

Imagery rescripting – this video shows an example of how a patient might rescript an episode of domestic violence. https://vimeo.com/837338244/e6aec9536e?share=copy. This is the session following the re-script of domestic violence above. It shows how to gather information over the week to decide whether to re-do last week’s re-script or to move onto a new target. https://vimeo.com/manage/videos/837335721/2a0a8d8c35

Outcome

At the end of therapy, Grace’s scores on standard measures had reduced from severe levels in all areas to scores that were within normal limits (WNL); see Table 6.

Table 6. Grace’s pre- and post-therapy scores on the screening measures

In addition, Grace’s re-experiencing symptoms had reduced from between 8–15 intrusions a day, to zero in a typical week. Grace described how she would, very occasionally, have a nightmare, but these usually only occurred if there had been a particular incident in the day, such as men shouting on the bus. Crucially, Grace said she could live happily with this much reduced level of symptoms.

In terms of Grace’s functioning, she described being very much happier, she attended a local church and was meeting new people. Her life also improved as she was granted leave to remain towards the end of our work together, so Grace was able to get a job, which improved her sense of self-esteem and confidence. Subjectively, Grace smiled and laughed more towards the end of our therapy and did not sit hunched over with her arms wrapped around her as she had at assessment.

Discussion

Therapists may approach working with women who have experienced FGM with caution due to various cultural considerations and sensitivities. This paper demonstrates that using imagery techniques with this population can lead to positive patient outcomes, and patient and therapist satisfaction. Both CRIM and ImRs are relatively culture-free, powerful techniques that can achieve excellent results within a relatively short space of time. With this in mind, future research examining the effectiveness of CRIM with a refugee population would be helpful.

Key practice points

-

(1) Using imagery rescripting means it is possible to work through many traumatic memories very quickly.

-

(2) Imagery rescripting leaves patients with a sense of power and mastery.

-

(3) Using imagery is very culturally appropriate (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Young, Akbar, Chessell, Stevens, Vann and Arntz2023). There is minimal reliance on linguistic information and patients are able to incorporate their own spiritual beliefs because the rescripting content comes directly from the patient.

-

(4) FGM is another form of sexual violence and therefore it can, and should, be addressed in therapy if the person is re-experiencing it.

-

(5) If sexual violence or rape has occurred, it is always worth asking if patients feel contaminated and, if so, use CRIM.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, L.D. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of the research participant.

Acknowledgements

With special thanks to Grace who is keen for this to be published to help other women in her position.

Author contributions

Lucinda Dixon: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Kerry Young: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (lead), Visualization (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Brenda Kelly: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. The participant gave informed consent to participate in the study and for the results to be published. Senior management at Oxford Rose Clinic approved the governance arrangements for this study. The person described in this case study has seen the submission and agreed to it going forward for publication.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.