1. Introduction

In [Reference ZagierZag10], Zagier introduced the concept of quantum modular forms (QMF). Given a Fuchsian cofinite subgroup

![]() $\Gamma$

of

$\Gamma$

of

![]() $\textrm{SL}(2, \mathbb{Z})$

whose set of cusps

$\textrm{SL}(2, \mathbb{Z})$

whose set of cusps

![]() $C(\Gamma)\subset \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Q})$

is non-empty, and

$C(\Gamma)\subset \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Q})$

is non-empty, and

![]() $k\in\mathbb{C}$

, QMF are defined as functions

$k\in\mathbb{C}$

, QMF are defined as functions

for some finite set S, satisfying a form of modularity, in the purposely vague sense that for any

![]() $\gamma=(\begin{smallmatrix}a & b\\ c&d\end{smallmatrix})\in\Gamma$

, the period function

$\gamma=(\begin{smallmatrix}a & b\\ c&d\end{smallmatrix})\in\Gamma$

, the period function

is somewhat regular with respect to the real topology. The exact assumptions vary widely in the literature; in our case, we will mainly require continuity or bounds on the growth around possible singularities.

Numerous examples of quantum modular forms are known, in various contexts, and we refer in particular to [Reference ZagierZag10, Reference Bringmann, Folsom and RhoadesBFR15, Reference Ngo and RhoadesNR17, Reference Kim, Lim and LovejoyKLL16, Reference Bruggeman, Lewis and ZagierBLZ15, Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY97, Reference Jaffard and MartinJM18]. More references are listed in the introduction of [Reference Bettin and DrappeauBD22].

In this paper, we focus on QMF for the full modular group

![]() $\Gamma =\textrm{SL}(2, \mathbb{Z})$

, so that

$\Gamma =\textrm{SL}(2, \mathbb{Z})$

, so that

![]() $C(\Gamma) =\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Q})$

, and which are periodic (i.e.

$C(\Gamma) =\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Q})$

, and which are periodic (i.e.

![]() $h_{U}=0$

for

$h_{U}=0$

for

![]() $U=(\begin{smallmatrix}1 & 1\\ 0&1\end{smallmatrix})$

).Footnote

1

By composition, it is sufficient to consider (1.1) for the second generator

$U=(\begin{smallmatrix}1 & 1\\ 0&1\end{smallmatrix})$

).Footnote

1

By composition, it is sufficient to consider (1.1) for the second generator

![]() $\gamma=(\begin{smallmatrix}0 & -1\\ 1&0\end{smallmatrix})$

of

$\gamma=(\begin{smallmatrix}0 & -1\\ 1&0\end{smallmatrix})$

of

![]() $\textrm{SL}(2, \mathbb{Z})$

, so that, in order to prove that f is a QMF, one only needs to verify that

$\textrm{SL}(2, \mathbb{Z})$

, so that, in order to prove that f is a QMF, one only needs to verify that

has some regularity property.

The cases of

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)=0$

and

$\operatorname{Re}(k)=0$

and

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)\neq0$

are different in nature. In the case

$\operatorname{Re}(k)\neq0$

are different in nature. In the case

![]() $k=0$

, by iterating the relation (1.2) and using periodicity, we can express f as a twisted Birkhoff sum of h evaluated along orbits under the Gauss map, see [Reference Bettin and DrappeauBD22, Equation (3.1)], the twist being given by the multiplicative automorphic factor. Using this observation, in [Reference Bettin and DrappeauBD22] it was then shown that, for a large class of functions h, the multisets

$k=0$

, by iterating the relation (1.2) and using periodicity, we can express f as a twisted Birkhoff sum of h evaluated along orbits under the Gauss map, see [Reference Bettin and DrappeauBD22, Equation (3.1)], the twist being given by the multiplicative automorphic factor. Using this observation, in [Reference Bettin and DrappeauBD22] it was then shown that, for a large class of functions h, the multisets

![]() $\{f(x)\mid x\in\mathbb{Q}\cap[0,1),\, \operatorname{Den}(x)\leqslant Q\}$

become asymptotically distributed, as

$\{f(x)\mid x\in\mathbb{Q}\cap[0,1),\, \operatorname{Den}(x)\leqslant Q\}$

become asymptotically distributed, as

![]() $Q\to\infty$

, according to a stable law, which is in fact a normal law if h is of moderate growth at 0.Footnote

2

As a consequence, one has that, in general, f is nowhere continuous according to the real topology, nor can f be extended by continuity to any point outside of

$Q\to\infty$

, according to a stable law, which is in fact a normal law if h is of moderate growth at 0.Footnote

2

As a consequence, one has that, in general, f is nowhere continuous according to the real topology, nor can f be extended by continuity to any point outside of

![]() $\mathbb{Q}$

. For the same reasons, we expect a similar phenomenon to occur whenever

$\mathbb{Q}$

. For the same reasons, we expect a similar phenomenon to occur whenever

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)=0$

.

$\operatorname{Re}(k)=0$

.

The purpose of the present paper is to study the case when

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)\neq 0$

.

$\operatorname{Re}(k)\neq 0$

.

1.1 Weights with negative real parts

If

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)<0$

and h is continuous on

$\operatorname{Re}(k)<0$

and h is continuous on

![]() $[-1,1]\smallsetminus \{0\}$

with finite right and left limits

$[-1,1]\smallsetminus \{0\}$

with finite right and left limits

![]() $h(0^\pm)$

at 0, then we show that, in fact, f can always be extended by continuity to a bounded function

$h(0^\pm)$

at 0, then we show that, in fact, f can always be extended by continuity to a bounded function

![]() $f^\triangleleft:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{C}$

. Moreover, we prove that

$f^\triangleleft:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{C}$

. Moreover, we prove that

![]() $f^\triangleleft$

is continuous on

$f^\triangleleft$

is continuous on

![]() $\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus \mathbb{Q}$

and is continuous on the whole real line if

$\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus \mathbb{Q}$

and is continuous on the whole real line if

![]() $h(0\pm)=f(0)$

, a condition that could be morally interpreted as saying that (1.2) holds also at ‘

$h(0\pm)=f(0)$

, a condition that could be morally interpreted as saying that (1.2) holds also at ‘

![]() $0^{\pm}$

’. More precisely, the following holds.

$0^{\pm}$

’. More precisely, the following holds.

Theorem 1.1. Let

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)<0$

and let

$\operatorname{Re}(k)<0$

and let

![]() $f:\mathbb{Q}\to\mathbb{C}$

be a 1-periodic function satisfying (1.2) for a function

$f:\mathbb{Q}\to\mathbb{C}$

be a 1-periodic function satisfying (1.2) for a function

![]() $h:\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus \{0\}\to \mathbb{C}$

which is continuous on

$h:\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus \{0\}\to \mathbb{C}$

which is continuous on

![]() $[-1,1]\smallsetminus \{0\}$

with finite left and right limits

$[-1,1]\smallsetminus \{0\}$

with finite left and right limits

![]() $h(0^\pm)$

at 0. Then the function

$h(0^\pm)$

at 0. Then the function

\begin{align} f^\triangleleft(x):= \begin{cases} f(x) & \text{if }x\in\mathbb{Q},\\ {\displaystyle \lim_{\mathbb{Q}\ni y\to x}f(y)} & \text{if }x\notin\mathbb{Q} \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} f^\triangleleft(x):= \begin{cases} f(x) & \text{if }x\in\mathbb{Q},\\ {\displaystyle \lim_{\mathbb{Q}\ni y\to x}f(y)} & \text{if }x\notin\mathbb{Q} \end{cases} \end{align}

is defined for all

![]() $x\in\mathbb{R}$

and is continuous on

$x\in\mathbb{R}$

and is continuous on

![]() $\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. Moreover, for any rational

$\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. Moreover, for any rational

![]() $x= a/q$

in reduced form, one has

$x= a/q$

in reduced form, one has

![]() $f^\triangleleft(y)\to f(x) + q^k(h(0^\pm)-f(0))$

as

$f^\triangleleft(y)\to f(x) + q^k(h(0^\pm)-f(0))$

as

![]() $y\to x^\pm$

. In particular,

$y\to x^\pm$

. In particular,

![]() $f^\triangleleft$

is continuous on

$f^\triangleleft$

is continuous on

![]() $\mathbb{R}$

if and only if

$\mathbb{R}$

if and only if

![]() $h(0^\pm)=f(0)$

. Furthermore, in this case, if

$h(0^\pm)=f(0)$

. Furthermore, in this case, if

![]() $h\in\mathcal C^{m}([-1,1],\mathbb{C})$

with

$h\in\mathcal C^{m}([-1,1],\mathbb{C})$

with

![]() $0\leqslant m < {| {\operatorname{Re}(k)} |}/2$

, then

$0\leqslant m < {| {\operatorname{Re}(k)} |}/2$

, then

![]() $f^\triangleleft\in\mathcal C^{m}(\mathbb{R},\mathbb{C})$

.

$f^\triangleleft\in\mathcal C^{m}(\mathbb{R},\mathbb{C})$

.

If h is continuous at 0 but

![]() $h(0)\neq f(0)$

, we can modify f by letting

$h(0)\neq f(0)$

, we can modify f by letting

![]() $\widetilde f(x):=f(x)+\operatorname{Den}(x)^k(h(0)-f(0))$

. The map

$\widetilde f(x):=f(x)+\operatorname{Den}(x)^k(h(0)-f(0))$

. The map

![]() $\widetilde f$

is a QMF with h as its period function, and

$\widetilde f$

is a QMF with h as its period function, and

![]() $\widetilde f(0)=h(0)$

.

$\widetilde f(0)=h(0)$

.

As we will see below, in some of the examples of QMF that we will consider, the map f actually admits an expression as an absolutely converging Fourier series, and the differentiability of such series has been studied in detail in many instances, see in particular [Reference ChamizoCha04, Reference PetrykiewiczPet14, Reference Chamizo, Petrykiewicz and Ruiz-CabelloCPRC17]. Theorem 1.1 instead gives a proof of the continuity and differentiability of f extended to

![]() $\mathbb{R}$

which does not rely on an a priori knowledge of a Fourier expansion for f.

$\mathbb{R}$

which does not rely on an a priori knowledge of a Fourier expansion for f.

Theorem 1.1 shows that, in fact, one cannot expect the period function h to be continuous if f does not have some continuity property to start with, so that non-trivial instances of QMF (meaning those cases when h is more regular than f) arise only when h is differentiable at least

![]() $\lceil -\operatorname{Re}(k)/2\rceil$

times.

$\lceil -\operatorname{Re}(k)/2\rceil$

times.

Our method uses properties of the Gauss map, and is closely related to the works [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY97, Reference Lee, Marmi, Petrykiewicz and SchindlerLMPS24, Reference Balazard and MartinBM19]. These works are concerned with the regularity properties of the Brjuno function. This function is related to linearization problems in holomorphic dynamics [Reference BrjunoBrj72, Reference YoccozYoc88, Reference YoccozYoc95], and is close to being a QMF of weight

![]() $-1$

, see [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY06]. The methods of [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY97] likely extend to the setting of Theorem 1.1, and would be relevant to study e.g. the Hölder regularity of the highest-order derivative of f (see Definitions 1.1 to 1.3 in [Reference Chamizo, Petrykiewicz and Ruiz-CabelloCPRC17]).

$-1$

, see [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY06]. The methods of [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY97] likely extend to the setting of Theorem 1.1, and would be relevant to study e.g. the Hölder regularity of the highest-order derivative of f (see Definitions 1.1 to 1.3 in [Reference Chamizo, Petrykiewicz and Ruiz-CabelloCPRC17]).

We point out that precise estimates on Hölder regularity are achievable by methods from wavelet theory. In [Reference PetrykiewiczPet14] this was carried out using an explicit Fourier expansion, while in [Reference Jaffard and MartinJM18] instead this was performed using properties of the Gauss map, a point of view similar to the one taken in [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY97] or in the present paper.

The existence of the function

![]() $f^\triangleleft$

in (1.3) can actually be proved under much weaker hypotheses, which we explain in what follows. This will be required later on, when we will study cotangent sums.

$f^\triangleleft$

in (1.3) can actually be proved under much weaker hypotheses, which we explain in what follows. This will be required later on, when we will study cotangent sums.

Theorem 1.2. Suppose that

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)<0$

and let

$\operatorname{Re}(k)<0$

and let

![]() $\delta>0$

. Suppose that f satisfies

$\delta>0$

. Suppose that f satisfies

in other words that f is 1-periodic separately on

![]() $(-\infty, 0)$

and

$(-\infty, 0)$

and

![]() $(0, \infty)$

, and that Equation (1.2) holds for

$(0, \infty)$

, and that Equation (1.2) holds for

![]() $x\in[-1, 1]\smallsetminus\{0\}$

, for a function h satisfying

$x\in[-1, 1]\smallsetminus\{0\}$

, for a function h satisfying

Then there is a full measure set

![]() $X \subset\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

such that the limit

$X \subset\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

such that the limit

exists for

![]() $x\in X$

, where

$x\in X$

, where

![]() $(x_j) = ([a_0(x); a_1(x), \dotsc, a_j(x)])_j$

denotes the sequence of convergents of x. This value coincides with the limit (1.3) when h is bounded. In general, for any

$(x_j) = ([a_0(x); a_1(x), \dotsc, a_j(x)])_j$

denotes the sequence of convergents of x. This value coincides with the limit (1.3) when h is bounded. In general, for any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

, there is a subset

$\varepsilon>0$

, there is a subset

![]() $X_\varepsilon\subset X$

invariant by

$X_\varepsilon\subset X$

invariant by

![]() $x\mapsto x+1$

and with

$x\mapsto x+1$

and with

![]() $\nu(X_\varepsilon \cap [0, 1]) \geqslant 1-\varepsilon$

, such that

$\nu(X_\varepsilon \cap [0, 1]) \geqslant 1-\varepsilon$

, such that

![]() $f^\triangleleft|_{X_\varepsilon}$

is continuous on

$f^\triangleleft|_{X_\varepsilon}$

is continuous on

![]() $X_\varepsilon$

equipped with the restricted topology. In particular,

$X_\varepsilon$

equipped with the restricted topology. In particular,

![]() $f^\triangleleft$

is Lebesgue-measurable.

$f^\triangleleft$

is Lebesgue-measurable.

The set X in this statement does not depend on f, h or

![]() $\delta$

. It consists of numbers having mildly growing continued fraction coefficients, see Lemma 2.2 below.

$\delta$

. It consists of numbers having mildly growing continued fraction coefficients, see Lemma 2.2 below.

The extension of the definition of f(x) also allows us to show that f has a limiting distribution when evaluated at reduced rationals

![]() $0\leqslant a/q<1$

with

$0\leqslant a/q<1$

with

![]() $q\to\infty$

.

$q\to\infty$

.

Theorem 1.3. Suppose that

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)<0$

and let

$\operatorname{Re}(k)<0$

and let

![]() $f:\mathbb{Q}\to\mathbb{C}$

satisfy (1.2) and (1.4), for a function

$f:\mathbb{Q}\to\mathbb{C}$

satisfy (1.2) and (1.4), for a function

![]() $h:\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus \{0\}\to \mathbb{C}$

satisfying (1.5). Then the multiset

$h:\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus \{0\}\to \mathbb{C}$

satisfying (1.5). Then the multiset

becomes distributed, as

![]() $q\to \infty$

, according to the push-forward

$q\to \infty$

, according to the push-forward

![]() $ f^\triangleleft_\ast(\nu)$

of the Lebesgue measure

$ f^\triangleleft_\ast(\nu)$

of the Lebesgue measure

![]() $\nu$

on [0, 1] (see [Reference Le GallLG22, p. 13]).

$\nu$

on [0, 1] (see [Reference Le GallLG22, p. 13]).

If, moreover, h is real-analytic on

![]() $(-1, 1)\smallsetminus\{0\}$

and f is non-constant on

$(-1, 1)\smallsetminus\{0\}$

and f is non-constant on

![]() $\mathbb{Q}_{>0}$

, then the measure

$\mathbb{Q}_{>0}$

, then the measure

![]() $f^\triangleleft_\ast(\nu)$

is diffuse.

$f^\triangleleft_\ast(\nu)$

is diffuse.

In contrast with the case

![]() $k=0$

treated in [Reference Baladi and ValléeBV05, Reference Bettin and DrappeauBD22], we remark here that we did not need to perform an additional average over q in order to obtain a limiting statement.

$k=0$

treated in [Reference Baladi and ValléeBV05, Reference Bettin and DrappeauBD22], we remark here that we did not need to perform an additional average over q in order to obtain a limiting statement.

We recall that a measure is diffuse if it has no atoms. When

![]() $f^\triangleleft$

is real-valued, then

$f^\triangleleft$

is real-valued, then

![]() $f^\triangleleft_\ast(\nu)$

is supported on

$f^\triangleleft_\ast(\nu)$

is supported on

![]() $\mathbb{R}$

, and diffuseness is equivalent to the continuity of the associated cumulative distribution function. Under appropriate conditions, we are able to reach the stronger conclusion that for any non-zero linear form

$\mathbb{R}$

, and diffuseness is equivalent to the continuity of the associated cumulative distribution function. Under appropriate conditions, we are able to reach the stronger conclusion that for any non-zero linear form

![]() $\phi:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{R}$

, the measure

$\phi:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{R}$

, the measure

![]() $(\phi\circ f^\triangleleft)_\ast(\nu)$

on

$(\phi\circ f^\triangleleft)_\ast(\nu)$

on

![]() $\mathbb{R}$

is diffuse.Footnote

3

This is equivalent to the statement that the graph of

$\mathbb{R}$

is diffuse.Footnote

3

This is equivalent to the statement that the graph of

![]() $f^\triangleleft$

never remains on a given straight line for a positive proportion of time: for any line

$f^\triangleleft$

never remains on a given straight line for a positive proportion of time: for any line

![]() $D\subset\mathbb{C}$

,

$D\subset\mathbb{C}$

,

![]() $\nu((f^\triangleright)^{-1}(D)) = 0$

. Also, the statement that

$\nu((f^\triangleright)^{-1}(D)) = 0$

. Also, the statement that

![]() $(\phi\circ f^\triangleleft)_\ast(\nu)$

is diffuse means that its cumulative distribution function is continuous.

$(\phi\circ f^\triangleleft)_\ast(\nu)$

is diffuse means that its cumulative distribution function is continuous.

1.2 Weights with positive real parts

In the case

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)>0$

, we find that iterating the reciprocity formula (1.2) does not imply the continuity of f, even if h is continuous. It is, however, still possible to extend naturally f if one considers f(x), not as a function of

$\operatorname{Re}(k)>0$

, we find that iterating the reciprocity formula (1.2) does not imply the continuity of f, even if h is continuous. It is, however, still possible to extend naturally f if one considers f(x), not as a function of

![]() $x= a/q$

, but rather as a function of

$x= a/q$

, but rather as a function of

![]() $\overline {x}:={\overline {a}_q}/q$

, where

$\overline {x}:={\overline {a}_q}/q$

, where

![]() $\overline a_q\in (0,q]$

is the multiplicative inverse of

$\overline a_q\in (0,q]$

is the multiplicative inverse of

![]() $a\ (\textrm{mod}\,q)$

.

$a\ (\textrm{mod}\,q)$

.

Theorem 1.4. Let

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)>0$

and let f be 1-periodic and satisfy (1.2) with

$\operatorname{Re}(k)>0$

and let f be 1-periodic and satisfy (1.2) with

![]() $h(x):\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\{0\}\to\mathbb{C}$

satisfying

$h(x):\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\{0\}\to\mathbb{C}$

satisfying

![]() $h(x)=O(|x|^{-\operatorname{Re}(k)})$

for

$h(x)=O(|x|^{-\operatorname{Re}(k)})$

for

![]() $|x|\in(0,1]$

. Then the function

$|x|\in(0,1]$

. Then the function

\begin{align} f^\triangleright(x):= \begin{cases} q^{-k}f(\overline x) & \text{if }x= a/q\in\mathbb{Q},\\ {\displaystyle \lim_{\mathbb{Q}\ni y= a/q\to x}q^{-k}f(\overline y)} & \text{if }x\notin\mathbb{Q} \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} f^\triangleright(x):= \begin{cases} q^{-k}f(\overline x) & \text{if }x= a/q\in\mathbb{Q},\\ {\displaystyle \lim_{\mathbb{Q}\ni y= a/q\to x}q^{-k}f(\overline y)} & \text{if }x\notin\mathbb{Q} \end{cases} \end{align}

defines a continuous function of

![]() $x\in\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. Furthermore, if

$x\in\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. Furthermore, if

![]() $h(x)=o(|x|^{-\operatorname{Re}(k)})$

as

$h(x)=o(|x|^{-\operatorname{Re}(k)})$

as

![]() $x\to0$

, then

$x\to0$

, then

![]() $f^\triangleleft$

is continuous on

$f^\triangleleft$

is continuous on

![]() $\mathbb{R}$

.

$\mathbb{R}$

.

Finally, there exists a full measure set

![]() $X \subset\mathbb{R}$

such that

$X \subset\mathbb{R}$

such that

![]() $f^\triangleright$

is

$f^\triangleright$

is

![]() $\alpha$

-Hölder continuous at any point of X, for any

$\alpha$

-Hölder continuous at any point of X, for any

![]() $\alpha<\frac12\operatorname{Re}(k)$

. In particular, if

$\alpha<\frac12\operatorname{Re}(k)$

. In particular, if

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)>2$

, then

$\operatorname{Re}(k)>2$

, then

![]() $f^\triangleright$

has derivative zero almost everywhere.

$f^\triangleright$

has derivative zero almost everywhere.

It would be interesting to know what could be said about the

![]() $L^p$

or the bounded mean oscillation regularity of

$L^p$

or the bounded mean oscillation regularity of

![]() $f^\triangleright$

, similarly to [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY97]; or what could be said about the fractal or multi-fractal property of

$f^\triangleright$

, similarly to [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY97]; or what could be said about the fractal or multi-fractal property of

![]() $f^\triangleright$

in specific cases, similarly to [Reference Jaffard and MartinJM18].

$f^\triangleright$

in specific cases, similarly to [Reference Jaffard and MartinJM18].

Also in the case

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)>0$

, the limit (1.7) makes sense under more general hypotheses, which we will require in some of our applications: it suffices that f satisfies (1.4) instead of being periodic on

$\operatorname{Re}(k)>0$

, the limit (1.7) makes sense under more general hypotheses, which we will require in some of our applications: it suffices that f satisfies (1.4) instead of being periodic on

![]() $\mathbb{R}$

, and that h merely satisfies

$\mathbb{R}$

, and that h merely satisfies

![]() $h(x)=O({e}^{-|x|^{\delta-1}})$

for

$h(x)=O({e}^{-|x|^{\delta-1}})$

for

![]() $x\in[-1,1]\smallsetminus\{0\}$

and some

$x\in[-1,1]\smallsetminus\{0\}$

and some

![]() $\delta>0$

. More precisely, the following holds.

$\delta>0$

. More precisely, the following holds.

Theorem 1.5. Suppose that

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)>0$

and let

$\operatorname{Re}(k)>0$

and let

![]() $f:\mathbb{Q}\to\mathbb{C}$

satisfy (1.2) and (1.4) for a function

$f:\mathbb{Q}\to\mathbb{C}$

satisfy (1.2) and (1.4) for a function

![]() $h:\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus \{0\}\to \mathbb{C}$

with

$h:\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus \{0\}\to \mathbb{C}$

with

![]() $h(x)\ll {e}^{|x|^{-1+\delta}}$

for

$h(x)\ll {e}^{|x|^{-1+\delta}}$

for

![]() $x\in(-1,1)\smallsetminus\{0\}$

and some

$x\in(-1,1)\smallsetminus\{0\}$

and some

![]() $\delta>0$

. Then the limit

$\delta>0$

. Then the limit

exists on a full measure subset X of

![]() $\mathbb{R}$

, and coincides with the value (1.7) under the hypotheses of Theorem 1.4.

$\mathbb{R}$

, and coincides with the value (1.7) under the hypotheses of Theorem 1.4.

Remark 1.6. As in Theorem 1.2 we will show, under the hypotheses stated above, the existence of sets

![]() $X_\varepsilon\subset X$

with

$X_\varepsilon\subset X$

with

![]() $\nu(X_\varepsilon)\geqslant 1-\varepsilon$

such that

$\nu(X_\varepsilon)\geqslant 1-\varepsilon$

such that

![]() $f^\triangleright|_{X_\varepsilon}$

is continuous with the restricted topology, and in particular

$f^\triangleright|_{X_\varepsilon}$

is continuous with the restricted topology, and in particular

![]() $f^\triangleright$

is also Lebesgue-measurable.

$f^\triangleright$

is also Lebesgue-measurable.

Similarly to Theorem 1.2, we can then show that the values of f at rationals converge to a limiting distribution.

Theorem 1.7. Under the notation and conditions of Theorem 1.5, the multisets

become distributed, as

![]() $q\to \infty$

, according to

$q\to \infty$

, according to

![]() $ f^\triangleright_\ast( \nu)$

.

$ f^\triangleright_\ast( \nu)$

.

Moreover, if h is not identically zero, and is either continuous on

![]() $[-1,1]$

or satisfies

$[-1,1]$

or satisfies

![]() $h(x)\ll {e}^{{| {x} |}^{-1+\delta}}$

and

$h(x)\ll {e}^{{| {x} |}^{-1+\delta}}$

and

![]() $h(x) \sim c x^{-\lambda}$

as

$h(x) \sim c x^{-\lambda}$

as

![]() $x\to0^+$

for some

$x\to0^+$

for some

![]() $\delta>0$

,

$\delta>0$

,

![]() $c\in\mathbb{C}\smallsetminus\{0\}$

and

$c\in\mathbb{C}\smallsetminus\{0\}$

and

![]() $\lambda\in\mathbb{R}_{>0}\smallsetminus\{k\}$

, then the measure

$\lambda\in\mathbb{R}_{>0}\smallsetminus\{k\}$

, then the measure

![]() $f^\triangleright_\ast( \nu)$

is diffuse.

$f^\triangleright_\ast( \nu)$

is diffuse.

Remark 1.8. One can relax considerably the conditions required to ensure the diffuseness of the limiting measures. For example, it is sufficient that h is right continuous at 0 with

![]() $h(0^+)\neq0$

or that h(x) goes to

$h(0^+)\neq0$

or that h(x) goes to

![]() $\infty$

as

$\infty$

as

![]() $x\to 0$

without staying too close to a multiple of

$x\to 0$

without staying too close to a multiple of

![]() $1-|x|^{-k}$

. See § 3.3 for more details.

$1-|x|^{-k}$

. See § 3.3 for more details.

Similarly as for

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)<0$

, under natural conditions which are, however, more involved, we show that the measure

$\operatorname{Re}(k)<0$

, under natural conditions which are, however, more involved, we show that the measure

![]() $(\phi \circ f^\triangleright)_\ast(\nu)$

on

$(\phi \circ f^\triangleright)_\ast(\nu)$

on

![]() $\mathbb{R}$

is diffuse for any non-zero linear form

$\mathbb{R}$

is diffuse for any non-zero linear form

![]() $\phi:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{R}$

.

$\phi:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{R}$

.

1.3 Applications

The above theorems apply to many objects, some of which are described in the following corollaries.

1.3.1 Eichler integrals of classical holomorphic forms.

The elementary-looking function

\begin{equation} A_{k,D}(x):=\sum_{\substack{Q(x)=ax^2+bx+c>0\\ a\in-\mathbb{N},\, b,c\in\mathbb{Z},\, b^2-4ac=D }}Q(x)^k,\quad x\in\mathbb{R}, k\in2\mathbb{N}+3,\ \square\neq D\equiv 1\ (\textrm{mod}\,4)\end{equation}

\begin{equation} A_{k,D}(x):=\sum_{\substack{Q(x)=ax^2+bx+c>0\\ a\in-\mathbb{N},\, b,c\in\mathbb{Z},\, b^2-4ac=D }}Q(x)^k,\quad x\in\mathbb{R}, k\in2\mathbb{N}+3,\ \square\neq D\equiv 1\ (\textrm{mod}\,4)\end{equation}

was introduced and studied by Zagier in [Reference ZagierZag99];Footnote

4

see [Reference BengoecheaBen15] for more details on the convergence of the sum. With a simple algebraic computation one can verify that

![]() $A_{k,D}(x)$

is a 1-periodic QMF of weight

$A_{k,D}(x)$

is a 1-periodic QMF of weight

![]() $-2k$

, satisfying (1.2) with a period function

$-2k$

, satisfying (1.2) with a period function

![]() $h = h_{k,D}$

which is a polynomial of degree 2k satisfying, by [Reference ZagierZag99, Equation (25)]

$h = h_{k,D}$

which is a polynomial of degree 2k satisfying, by [Reference ZagierZag99, Equation (25)]

$$ h_{k,D}(0)=A_{k,D}(0) = \sum_{\substack{0\leqslant b < \sqrt{D} \\b^2 \equiv D \ (\textrm{mod}\,4)}} \sigma_k\bigg(\frac{D-b^2}4\bigg) $$

$$ h_{k,D}(0)=A_{k,D}(0) = \sum_{\substack{0\leqslant b < \sqrt{D} \\b^2 \equiv D \ (\textrm{mod}\,4)}} \sigma_k\bigg(\frac{D-b^2}4\bigg) $$

where

![]() $\sigma_k(n) = \sum_{d\mid n}d^k$

. Theorem 1.1 applies to

$\sigma_k(n) = \sum_{d\mid n}d^k$

. Theorem 1.1 applies to

![]() $A_{k,D}$

and gives another proof that

$A_{k,D}$

and gives another proof that

![]() $A_{k,D}\in\mathcal C^{k-1}(\mathbb{R},\mathbb{R})$

. The fact that

$A_{k,D}\in\mathcal C^{k-1}(\mathbb{R},\mathbb{R})$

. The fact that

![]() $A_{k,D}(x)$

is in

$A_{k,D}(x)$

is in

![]() $\mathcal C^{k-1}(\mathbb{R},\mathbb{R})$

was instead obtained by Zagier in [Reference ZagierZag99] by observing that

$\mathcal C^{k-1}(\mathbb{R},\mathbb{R})$

was instead obtained by Zagier in [Reference ZagierZag99] by observing that

![]() $h_{k,D}$

belongs to the space of period polynomials corresponding to modular forms of weight

$h_{k,D}$

belongs to the space of period polynomials corresponding to modular forms of weight

![]() $2k+2$

. This implies, in particular, that

$2k+2$

. This implies, in particular, that

![]() $A_{k,D}(x)$

has to coincide with the Eichler integral of a weight

$A_{k,D}(x)$

has to coincide with the Eichler integral of a weight

![]() $2k+2$

modular form and thus can be written as a Fourier series whose nth Fourier coefficient decays roughly as

$2k+2$

modular form and thus can be written as a Fourier series whose nth Fourier coefficient decays roughly as

![]() $n^{-k-1/2}$

, see [Reference ZagierZag99, Equation (53)].

$n^{-k-1/2}$

, see [Reference ZagierZag99, Equation (53)].

From Theorem 1.3 we deduce the following distributional result for

![]() $A_{k,D}$

.

$A_{k,D}$

.

Corollary 1.9. Let

![]() $k\geqslant 5$

be odd and assume

$k\geqslant 5$

be odd and assume

![]() $D \equiv 0,1 \ (\textrm{mod}\,4)$

is not a square. Then

$D \equiv 0,1 \ (\textrm{mod}\,4)$

is not a square. Then

becomes distributed, as

![]() $q\to \infty$

, according to the measure

$q\to \infty$

, according to the measure

![]() $(A_{k,D}^\triangleleft)_\ast( \nu)$

. This measure has a continuous cumulative distribution function.

$(A_{k,D}^\triangleleft)_\ast( \nu)$

. This measure has a continuous cumulative distribution function.

More generally, let g be in the space

![]() $\text{S}_{k}(1)$

of cusp forms of weight

$\text{S}_{k}(1)$

of cusp forms of weight

![]() $k\geqslant12$

and level 1. If

$k\geqslant12$

and level 1. If

![]() $g(z):=\sum_{n\geqslant1}a_n{e}(nz)$

for

$g(z):=\sum_{n\geqslant1}a_n{e}(nz)$

for

![]() $\operatorname{Im}(z)>0$

, where

$\operatorname{Im}(z)>0$

, where

![]() ${e}(z):={e}^{2\pi i z}$

, then the Eichler integral of g

${e}(z):={e}^{2\pi i z}$

, then the Eichler integral of g

restricted to

![]() $\mathbb{Q}$

, is a quantum modular form of weight

$\mathbb{Q}$

, is a quantum modular form of weight

![]() $2-k$

with period function given by the period polynomials of g.

$2-k$

with period function given by the period polynomials of g.

Corollary 1.10. For

![]() $k\geqslant12$

, let

$k\geqslant12$

, let

![]() $0\neq g\in \text{S}_{k}(1)$

. Then

$0\neq g\in \text{S}_{k}(1)$

. Then

becomes distributed, as

![]() $q\to \infty$

, according to

$q\to \infty$

, according to

![]() $\widetilde g^\triangleleft_\ast( \nu)$

. For any non-zero linear form

$\widetilde g^\triangleleft_\ast( \nu)$

. For any non-zero linear form

![]() $\phi:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{R}$

, the measure

$\phi:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{R}$

, the measure

![]() $(\phi\circ \widetilde g^\triangleleft)_\ast(\nu)$

is diffuse.

$(\phi\circ \widetilde g^\triangleleft)_\ast(\nu)$

is diffuse.

It follows from Theorem 1.1 that the map

![]() $\widetilde g$

is

$\widetilde g$

is

![]() $k/2-1$

times differentiable, but in this special case it could be seen immediately from the definition (1.10) and square-root cancellation in averages of

$k/2-1$

times differentiable, but in this special case it could be seen immediately from the definition (1.10) and square-root cancellation in averages of

![]() $a_n$

, see [Reference IwaniecIwa97, Theorem 5.3]. We comment on this after the proofs, see Remark 4.3.

$a_n$

, see [Reference IwaniecIwa97, Theorem 5.3]. We comment on this after the proofs, see Remark 4.3.

1.3.2 Period functions of Maaß forms.

In [Reference Lewis and ZagierLZ01], Lewis and Zagier extend in some sense the theory of period polynomial to period functions associated to Maaß forms. Their work then allows us to construct quantum modular forms also from Maaß forms, as was described by Bruggeman [Reference BruggemanBru07]. We briefly review their construction. Let u be a Maaß cusp form for

![]() $\textrm{SL}(2, \mathbb{Z})$

of Laplace eigenvalue

$\textrm{SL}(2, \mathbb{Z})$

of Laplace eigenvalue

![]() $s(1-s)$

, with

$s(1-s)$

, with

![]() $s\in1/2+i\mathbb{R}_{>0}$

, which we expand as

$s\in1/2+i\mathbb{R}_{>0}$

, which we expand as

We define

$$ \widetilde u(z) := \frac{\pi^s \Gamma(1-s)}2 \sum_{n\geqslant1} n^{s-1/2} a_n {e}(nz) \quad (\operatorname{Im}(z)\gt0). $$

$$ \widetilde u(z) := \frac{\pi^s \Gamma(1-s)}2 \sum_{n\geqslant1} n^{s-1/2} a_n {e}(nz) \quad (\operatorname{Im}(z)\gt0). $$

We then include

![]() $\mathbb{Q}$

in the domain of

$\mathbb{Q}$

in the domain of

![]() $\widetilde u$

by letting

$\widetilde u$

by letting

It is shown in [Reference BruggemanBru07, Reference Lewis and ZagierLZ01] that

![]() $\widetilde u(x)$

thus defined is a quantum modular form of weight 2s whose associated period function h is

$\widetilde u(x)$

thus defined is a quantum modular form of weight 2s whose associated period function h is

![]() $\mathcal{C}^\infty$

on

$\mathcal{C}^\infty$

on

![]() $\mathbb{R}$

and real-analytic on

$\mathbb{R}$

and real-analytic on

![]() $\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\{0\}$

. Using a suitable variant of Theorem 1.7, we will deduce the following result.

$\mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\{0\}$

. Using a suitable variant of Theorem 1.7, we will deduce the following result.

Corollary 1.11. Let u be a non-trivial Maaß form of spectral eigenvalue

![]() $s(1-s)$

. Then

$s(1-s)$

. Then

becomes distributed, as

![]() $q\to \infty$

, according to

$q\to \infty$

, according to

![]() $\widetilde u^\triangleright_\ast( \nu)$

. Moreover, for any non-zero linear form

$\widetilde u^\triangleright_\ast( \nu)$

. Moreover, for any non-zero linear form

![]() $\phi:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{R}$

, the measure

$\phi:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{R}$

, the measure

![]() $(\phi\circ \widetilde u^\triangleright)_\ast(\nu)$

is diffuse.

$(\phi\circ \widetilde u^\triangleright)_\ast(\nu)$

is diffuse.

We also show that

![]() $\widetilde u^\triangleright$

is almost everywhere locally

$\widetilde u^\triangleright$

is almost everywhere locally

![]() $(1/2-\varepsilon)$

-Hölder continuous, but again in this case it can be seen directly from the Fourier expansion of the underlying form, see Remark 4.3.

$(1/2-\varepsilon)$

-Hölder continuous, but again in this case it can be seen directly from the Fourier expansion of the underlying form, see Remark 4.3.

1.3.3 A function of Kontsevich and Zagier.

Another example of quantum modular form, described in [Reference ZagierZag01, Reference ZagierZag10], is given by the series

\begin{equation} \varphi(x):={e}(x/24)\sum_{m=0}^\infty (1-{e}(x))\cdots (1-{e}(m x)) \quad (x\in\mathbb{Q}).\end{equation}

\begin{equation} \varphi(x):={e}(x/24)\sum_{m=0}^\infty (1-{e}(x))\cdots (1-{e}(m x)) \quad (x\in\mathbb{Q}).\end{equation}

This function was studied by Kontsevich and is related to the Stoimenow numbers, which are used to bound the number of linearly independent Vassiliev invariants of a given degree. In [Reference ZagierZag01], a proof is sketched that

![]() $\varphi$

is a quantum modular form of weight

$\varphi$

is a quantum modular form of weight

![]() $\frac32$

in the generalized meaning that

$\frac32$

in the generalized meaning that

for a period function h(x) which is smooth on

![]() $\mathbb{R}$

(and, in fact, also continues analytically to

$\mathbb{R}$

(and, in fact, also continues analytically to

![]() $\mathbb{C}\smallsetminus i\mathbb{R}_+$

).Footnote

5

See [Reference Bringmann and RolenBR16] for a proof in the context of period functions for half-integral weight forms, and [Reference Goswami and OsburnGO21] for a generalization to periodic theta functions. In this case, due to the automorphy factors in the reciprocity relation (1.13), the definition of the limiting function

$\mathbb{C}\smallsetminus i\mathbb{R}_+$

).Footnote

5

See [Reference Bringmann and RolenBR16] for a proof in the context of period functions for half-integral weight forms, and [Reference Goswami and OsburnGO21] for a generalization to periodic theta functions. In this case, due to the automorphy factors in the reciprocity relation (1.13), the definition of the limiting function

![]() $\varphi^\triangleright$

is as follows: for

$\varphi^\triangleright$

is as follows: for

![]() $x \in \mathbb{Q}\cap (0, 1]$

,

$x \in \mathbb{Q}\cap (0, 1]$

,

![]() $x = [0; b_1, \ldots, b_r]$

with r odd, denote

$x = [0; b_1, \ldots, b_r]$

with r odd, denote

![]() $\sigma(x) = 3 + \sum_{1\leqslant j \leqslant r} (-1)^j b_j$

. Then

$\sigma(x) = 3 + \sum_{1\leqslant j \leqslant r} (-1)^j b_j$

. Then

\begin{equation} \varphi^\triangleright(x) := \begin{cases} {e}(\frac{-1}{24}\sigma(x))\operatorname{Den}(x)^{-3/2} \varphi(\overline x) & (x\in \mathbb{Q}\cap (0, 1]), \\ \lim_{\mathbb{Q} \ni y \to x} \varphi^\triangleright(y) & (x\not\in\mathbb{Q}). \end{cases}\end{equation}

\begin{equation} \varphi^\triangleright(x) := \begin{cases} {e}(\frac{-1}{24}\sigma(x))\operatorname{Den}(x)^{-3/2} \varphi(\overline x) & (x\in \mathbb{Q}\cap (0, 1]), \\ \lim_{\mathbb{Q} \ni y \to x} \varphi^\triangleright(y) & (x\not\in\mathbb{Q}). \end{cases}\end{equation}

By suitable variants of Theorems 1.4 and 1.7, we obtain the following result.

Corollary 1.12. The map

![]() $\varphi^\triangleright$

is continuous and, in fact, almost everywhere locally

$\varphi^\triangleright$

is continuous and, in fact, almost everywhere locally

![]() $(3/4-\varepsilon)$

-Hölder continuous for any

$(3/4-\varepsilon)$

-Hölder continuous for any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

.

$\varepsilon>0$

.

Moreover, the multiset

becomes distributed, as

![]() $q\to \infty$

, according to

$q\to \infty$

, according to

![]() $ \varphi^\triangleright_\ast( \nu)$

. For any

$ \varphi^\triangleright_\ast( \nu)$

. For any

![]() $\theta\in\mathbb{R}$

, the cumulative distribution function of

$\theta\in\mathbb{R}$

, the cumulative distribution function of

![]() $(\operatorname{Re}{e}^{i\theta}\varphi^\triangleright)_\ast( \nu)$

is continuous.

$(\operatorname{Re}{e}^{i\theta}\varphi^\triangleright)_\ast( \nu)$

is continuous.

Remark 1.13. The function

![]() $\sigma(x)$

can be expressed in terms of the Dedekind sum s(x) [Reference Rademacher and GrosswaldRG72]: using [Reference HickersonHic77, Theorem 1], we find

$\sigma(x)$

can be expressed in terms of the Dedekind sum s(x) [Reference Rademacher and GrosswaldRG72]: using [Reference HickersonHic77, Theorem 1], we find

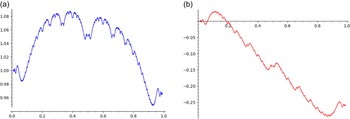

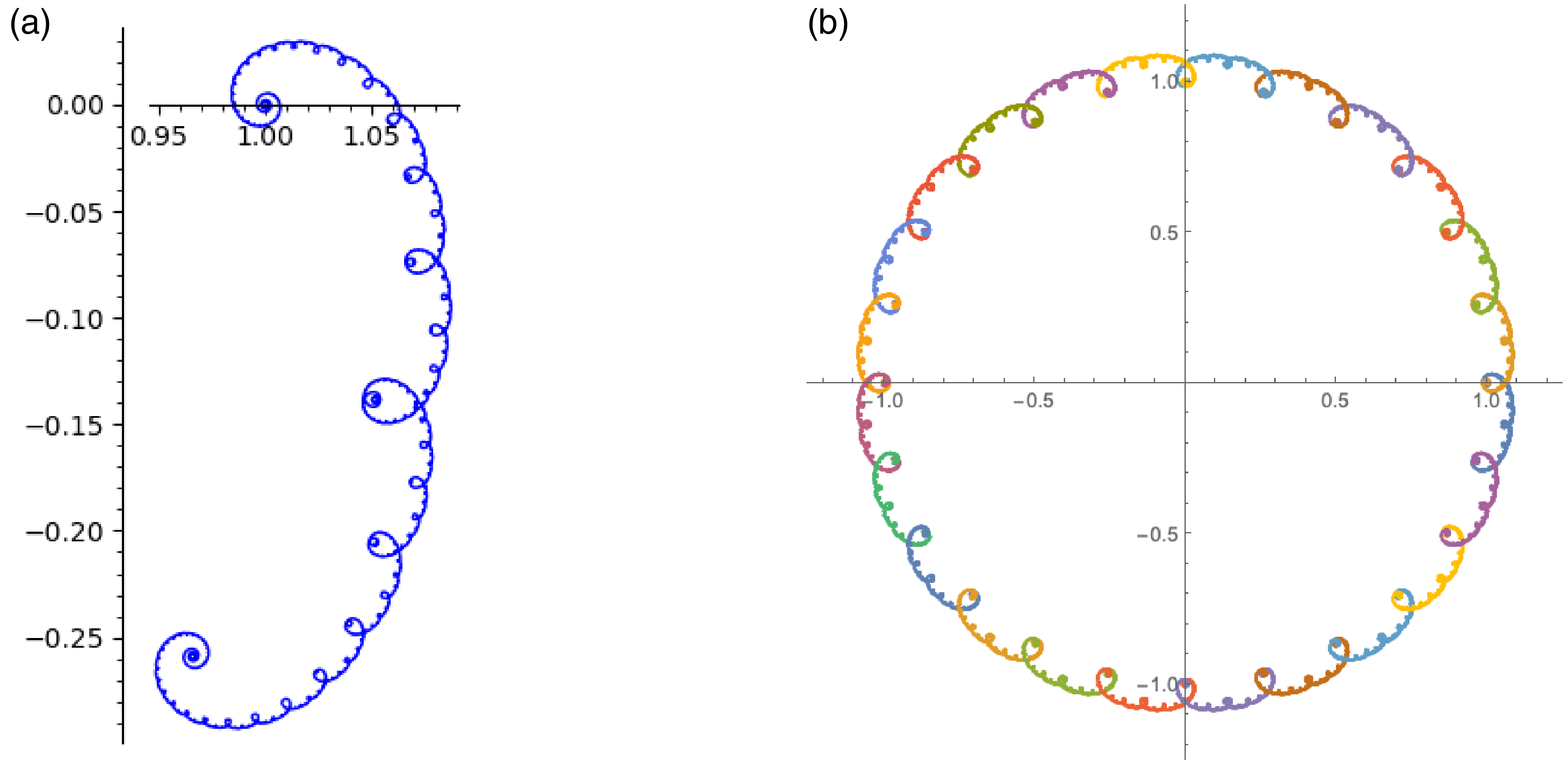

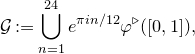

The function

![]() $\varphi^\triangleright : [0, 1] \to \mathbb{C}$

is depicted in Figure 1. Note that

$\varphi^\triangleright : [0, 1] \to \mathbb{C}$

is depicted in Figure 1. Note that

![]() $\varphi^\triangleright(0) = 1$

.

$\varphi^\triangleright(0) = 1$

.

Figure 1. Approximate plots of

![]() $\operatorname{Re} \varphi^\triangleright$

(a) and

$\operatorname{Re} \varphi^\triangleright$

(a) and

![]() $\operatorname{Im} \varphi^\triangleright$

(b) defined in (1.12).

$\operatorname{Im} \varphi^\triangleright$

(b) defined in (1.12).

If we normalize

![]() $\varphi$

by letting

$\varphi$

by letting

![]() $\varphi^\dagger(x):=\operatorname{Den}(x)^{-3/2}\varphi(x)$

, then as an immediate consequence of Corollary 1.12, we obtain that

$\varphi^\dagger(x):=\operatorname{Den}(x)^{-3/2}\varphi(x)$

, then as an immediate consequence of Corollary 1.12, we obtain that

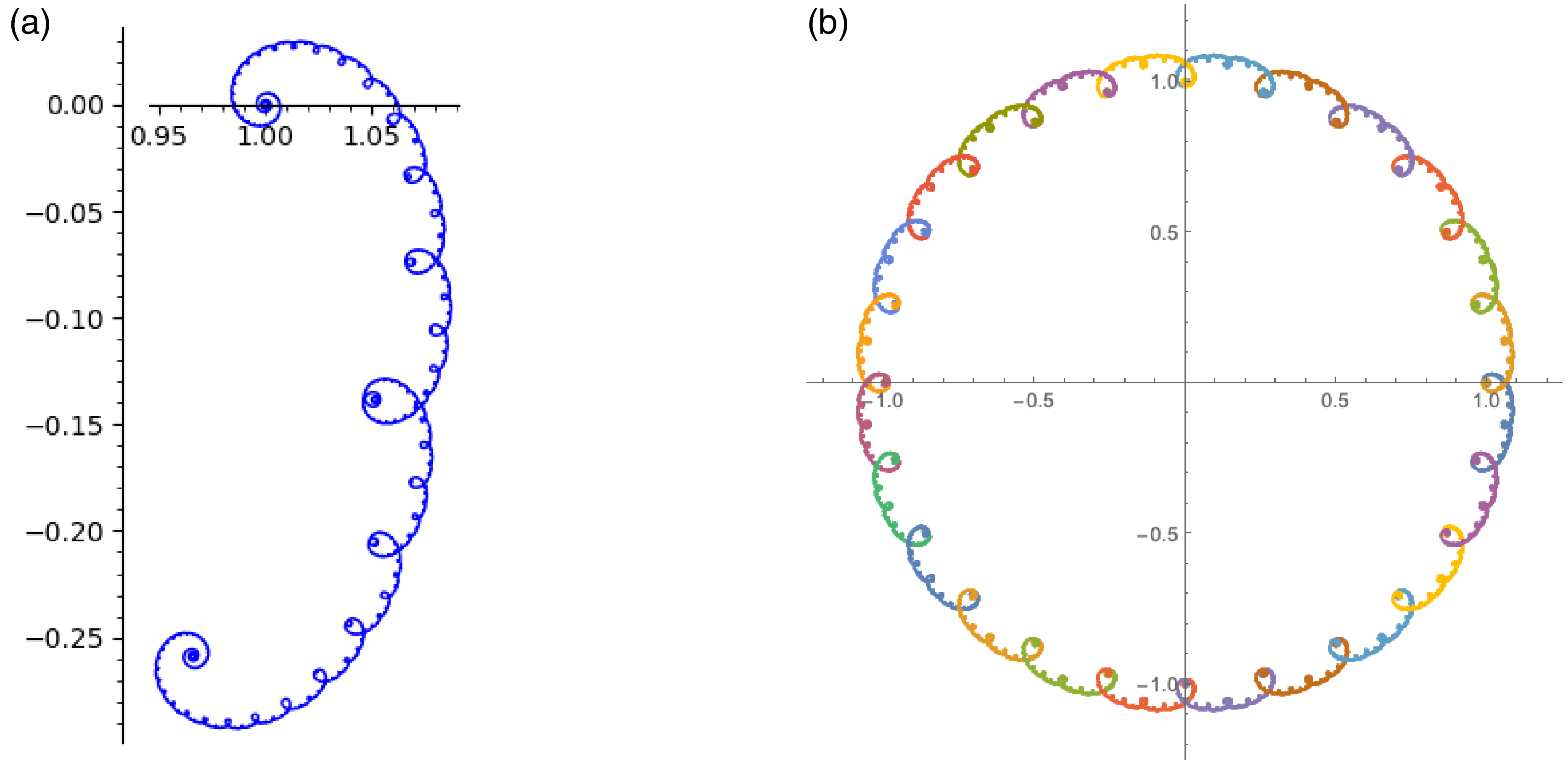

![]() $\overline{\varphi^\dagger(\mathbb{Q})}$

is equal to the curve

$\overline{\varphi^\dagger(\mathbb{Q})}$

is equal to the curve

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

given by

$\mathcal{G}$

given by

$$ \mathcal{G} := \bigcup_{n=1}^{24} {e}^{\pi i n/12} \varphi^\triangleright([0, 1]), $$

$$ \mathcal{G} := \bigcup_{n=1}^{24} {e}^{\pi i n/12} \varphi^\triangleright([0, 1]), $$

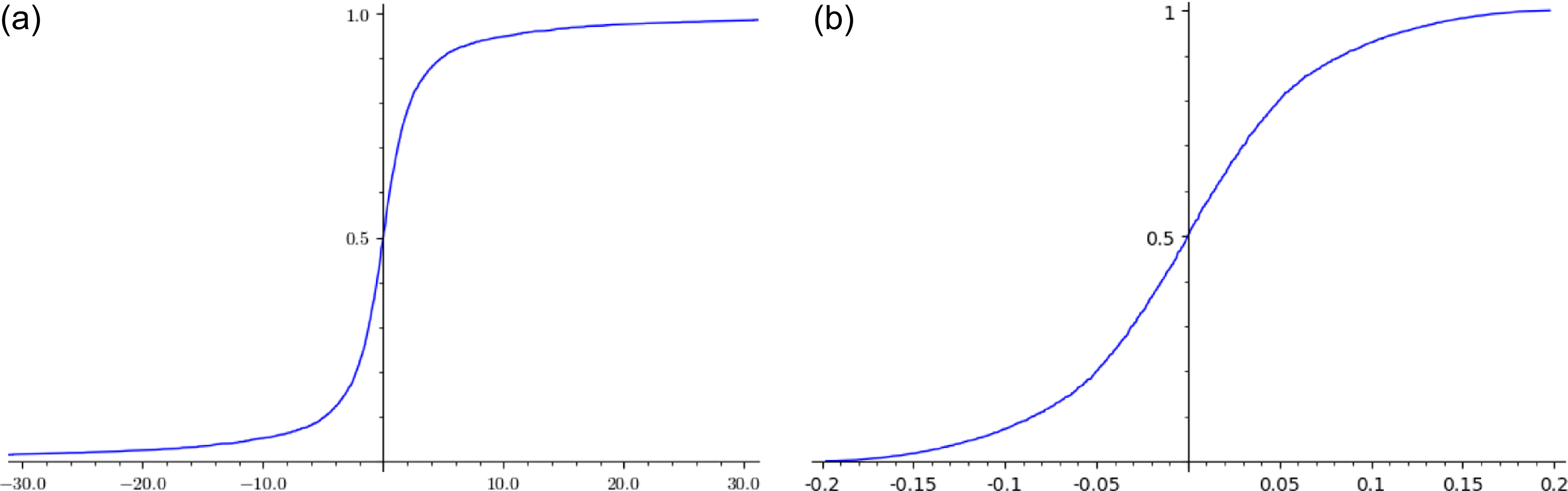

which passes through the 24th roots of unity. In Figure 2a, we have plotted the points

![]() $\varphi^\triangleright(x)$

for

$\varphi^\triangleright(x)$

for

![]() $\operatorname{Den}(x)\leqslant 101$

. The limiting curve is the graph of

$\operatorname{Den}(x)\leqslant 101$

. The limiting curve is the graph of

![]() $\varphi^\triangleright$

. In Figure 2b, we have plotted the points

$\varphi^\triangleright$

. In Figure 2b, we have plotted the points

![]() $\varphi^\dagger(x)$

for

$\varphi^\dagger(x)$

for

![]() $\operatorname{Den}(x)\leqslant 307$

, colored depending on

$\operatorname{Den}(x)\leqslant 307$

, colored depending on

![]() $\sigma(x)$

. The limiting curve is the curve

$\sigma(x)$

. The limiting curve is the curve

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

.

$\mathcal{G}$

.

Figure 2. Approximate plots of

![]() $\varphi^\triangleright([0, 1])$

(a) and

$\varphi^\triangleright([0, 1])$

(a) and

![]() $\varphi^\dagger([0, 1])$

(b).

$\varphi^\dagger([0, 1])$

(b).

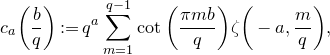

1.3.4 Generalized cotangent sums.

Finally we mention the generalized cotangent functions, studied in [Reference Bettin and ConreyBC13a] and defined for

![]() $b\in\mathbb{Z}$

,

$b\in\mathbb{Z}$

,

![]() $q\in\mathbb{N}_{>0}$

, coprime by

$q\in\mathbb{N}_{>0}$

, coprime by

$$c_a\bigg(\frac bq\bigg):=q^a\sum_{m=1}^{q-1}\cot\bigg(\frac{\pi m b}{q}\bigg)\zeta\bigg(-a,\frac mq\bigg),$$

$$c_a\bigg(\frac bq\bigg):=q^a\sum_{m=1}^{q-1}\cot\bigg(\frac{\pi m b}{q}\bigg)\zeta\bigg(-a,\frac mq\bigg),$$

where

![]() $a\in \mathbb{C}$

. Here,

$a\in \mathbb{C}$

. Here,

![]() $\zeta(s,x)$

denotes the Hurwitz zeta function, which is the analytic continuation of

$\zeta(s,x)$

denotes the Hurwitz zeta function, which is the analytic continuation of

![]() $s\mapsto \sum_{n\geqslant 1} (n+x)^{-s}$

. When

$s\mapsto \sum_{n\geqslant 1} (n+x)^{-s}$

. When

![]() $a=-1$

, the poles of

$a=-1$

, the poles of

![]() $\zeta$

cancel out and

$\zeta$

cancel out and

![]() $c_a$

reduces in that case to the classical Dedekind sum [Reference Rademacher and GrosswaldRG72]. In [Reference Bettin and ConreyBC13a], it was shown that the functions

$c_a$

reduces in that case to the classical Dedekind sum [Reference Rademacher and GrosswaldRG72]. In [Reference Bettin and ConreyBC13a], it was shown that the functions

![]() $c_a$

are almost quantum modular forms of weight

$c_a$

are almost quantum modular forms of weight

![]() $1+a$

with period function

$1+a$

with period function

![]() $h_a$

satisfying, in a neighborhood of 0, the estimate

$h_a$

satisfying, in a neighborhood of 0, the estimate

The meaning of ‘almost’ here will be made precise later on. The function

![]() $c_a$

is very closely related to Eichler integrals of certain real-analytic Eisenstein series, see [Reference Bettin and ConreyBC13a, § 2] and [Reference Lewis and ZagierLZ19]. We will deduce from our main results the following statement on the distribution of values of

$c_a$

is very closely related to Eichler integrals of certain real-analytic Eisenstein series, see [Reference Bettin and ConreyBC13a, § 2] and [Reference Lewis and ZagierLZ19]. We will deduce from our main results the following statement on the distribution of values of

![]() $c_a$

.

$c_a$

.

Corollary 1.14. If

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(a)<-1$

, then the multiset

$\operatorname{Re}(a)<-1$

, then the multiset

becomes distributed, as

![]() $q\to \infty$

, according to the measure

$q\to \infty$

, according to the measure

![]() $\lambda_a := (c_a^\triangleleft)_\ast( \nu)$

. If

$\lambda_a := (c_a^\triangleleft)_\ast( \nu)$

. If

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(a)>-1$

, then the multiset

$\operatorname{Re}(a)>-1$

, then the multiset

becomes distributed, as

![]() $q\to \infty$

, according to a measure

$q\to \infty$

, according to a measure

![]() $\lambda_a := (c_a^\triangleright)_\ast( \nu)$

. Moreover:

$\lambda_a := (c_a^\triangleright)_\ast( \nu)$

. Moreover:

-

(1) when

$a\in (2\mathbb{Z}_{\geqslant0}+1)$

, the measure

$a\in (2\mathbb{Z}_{\geqslant0}+1)$

, the measure

$\lambda_a$

is supported on

$\lambda_a$

is supported on

$\{0\}$

;

$\{0\}$

; -

(2) when

$a\in \mathbb{R}\smallsetminus(2\mathbb{Z}_{\geqslant -1}+1)$

, the measure

$a\in \mathbb{R}\smallsetminus(2\mathbb{Z}_{\geqslant -1}+1)$

, the measure

$\lambda_a$

is supported inside

$\lambda_a$

is supported inside

$\mathbb{R}$

and is diffuse;

$\mathbb{R}$

and is diffuse; -

(3) when

$\operatorname{Re}(a)\neq -1$

and

$\operatorname{Re}(a)\neq -1$

and

$a\not\in\mathbb{R}$

, then for any non-zero linear form

$a\not\in\mathbb{R}$

, then for any non-zero linear form

$\phi:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{R}$

, the push-forward measure

$\phi:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{R}$

, the push-forward measure

$\phi_\ast(\lambda_a)$

on

$\phi_\ast(\lambda_a)$

on

$\mathbb{R}$

is diffuse.

$\mathbb{R}$

is diffuse.

When

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(a)>0$

, the map

$\operatorname{Re}(a)>0$

, the map

![]() $c_a^\triangleright$

is continuous at irrationals. Moreover, for

$c_a^\triangleright$

is continuous at irrationals. Moreover, for

![]() $0<\operatorname{Re}(a)\leqslant 1$

, the map

$0<\operatorname{Re}(a)\leqslant 1$

, the map

![]() $x\mapsto c_a^\triangleright(x)$

is

$x\mapsto c_a^\triangleright(x)$

is

![]() $\alpha$

-Hölder-continuous locally almost everywhere, for any

$\alpha$

-Hölder-continuous locally almost everywhere, for any

![]() $\alpha<(\operatorname{Re}(a)+1)/2$

. When

$\alpha<(\operatorname{Re}(a)+1)/2$

. When

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(a)>1$

, the same is true for the map

$\operatorname{Re}(a)>1$

, the same is true for the map

![]() $x\mapsto c_a^\triangleright(x) + x a \zeta(1-a)/\pi$

, and in particular the map

$x\mapsto c_a^\triangleright(x) + x a \zeta(1-a)/\pi$

, and in particular the map

![]() $c_a^\triangleright$

is then differentiable almost everywhere with derivative

$c_a^\triangleright$

is then differentiable almost everywhere with derivative

![]() $-a\zeta(1-a)/\pi$

.

$-a\zeta(1-a)/\pi$

.

In this statement we have kept the notation

![]() $c_a^\triangleleft, c_a^\triangleright$

; however, we warn that the actual definitions differ from those in Theorems 1.1 and 1.4, mainly due to the fact

$c_a^\triangleleft, c_a^\triangleright$

; however, we warn that the actual definitions differ from those in Theorems 1.1 and 1.4, mainly due to the fact

![]() $c_a$

is only ‘almost’ a quantum modular form. The precise definitions are given in § 4.3 below in several cases depending on the value of a.

$c_a$

is only ‘almost’ a quantum modular form. The precise definitions are given in § 4.3 below in several cases depending on the value of a.

In the case (3) above, we obviously also have that

![]() $\lambda_a$

itself has no atoms.

$\lambda_a$

itself has no atoms.

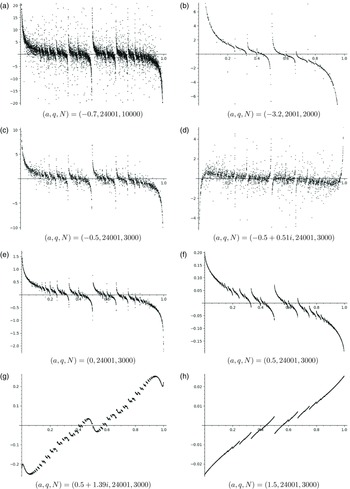

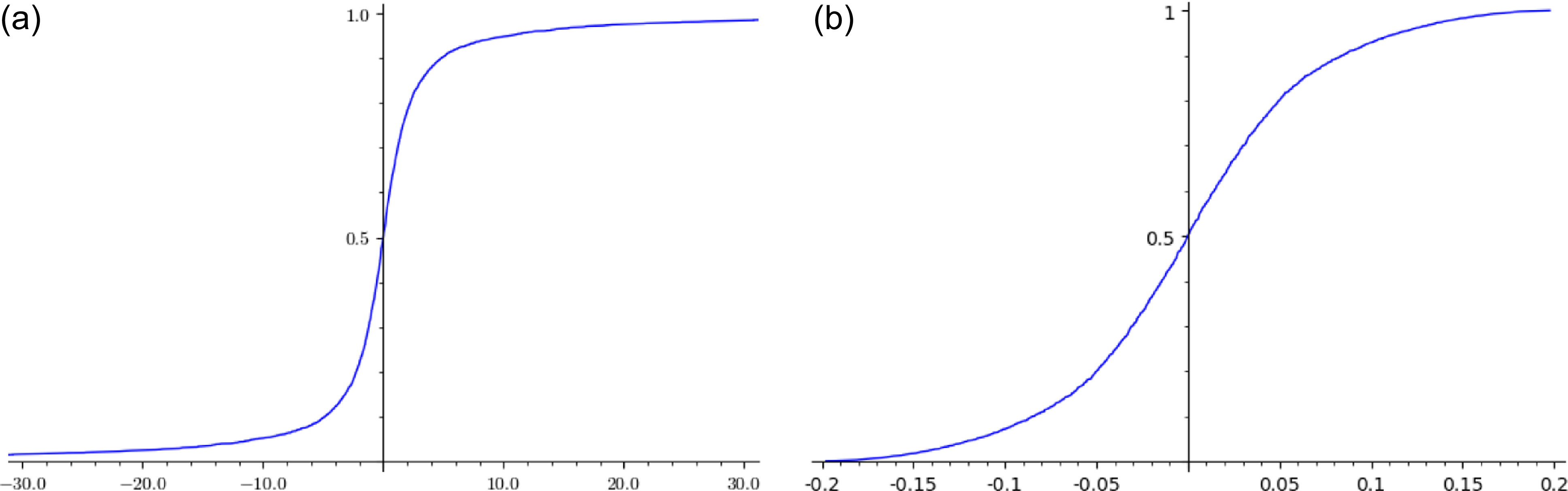

The empirical cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) in Corollary 1.14 for

![]() $q=5000$

are plotted in Figure 3 for some real values of a. The fact that the corresponding measures are diffuse, stated in item (2) of the previous corollary, translates into the continuity of the limiting functions.

$q=5000$

are plotted in Figure 3 for some real values of a. The fact that the corresponding measures are diffuse, stated in item (2) of the previous corollary, translates into the continuity of the limiting functions.

Figure 3. CDF of the empirical measures at

![]() $q=5000$

in Corollary 1.14, for

$q=5000$

in Corollary 1.14, for

![]() $a = -2$

(a) and

$a = -2$

(a) and

![]() $a = 1/2$

(b).

$a = 1/2$

(b).

The case

![]() $a=0$

of Corollary 1.14 was studied earlier in [Reference Maier and ThMR16, Reference BettinBet15]. The fact that the values of

$a=0$

of Corollary 1.14 was studied earlier in [Reference Maier and ThMR16, Reference BettinBet15]. The fact that the values of

![]() $c_0$

have a limiting distribution was proved in [Reference Maier and ThMR16] with an elaborate argument relying on an explicit expression for

$c_0$

have a limiting distribution was proved in [Reference Maier and ThMR16] with an elaborate argument relying on an explicit expression for

![]() $c_0({\overline b_q}/{q})$

in terms of

$c_0({\overline b_q}/{q})$

in terms of

![]() $b/q$

(see e.g. [Reference BettinBet15, pp. 1–2]). A simpler proof was then given in [Reference BettinBet15] using an explicit computation of the moments of both the original QMF and the limiting measure. In the generality of Theorem 1.7, and already even in the case

$b/q$

(see e.g. [Reference BettinBet15, pp. 1–2]). A simpler proof was then given in [Reference BettinBet15] using an explicit computation of the moments of both the original QMF and the limiting measure. In the generality of Theorem 1.7, and already even in the case

![]() $a<-1$

and

$a<-1$

and

![]() $a\in (-1, 0)$

of Corollary 1.14, the moments don’t exist (see Remark 4.2). The proof of Theorems 1.3 and 1.7 instead identifies directly the limiting function and avoids the computation of moments, thus allowing for more general period functions h.

$a\in (-1, 0)$

of Corollary 1.14, the moments don’t exist (see Remark 4.2). The proof of Theorems 1.3 and 1.7 instead identifies directly the limiting function and avoids the computation of moments, thus allowing for more general period functions h.

It might be interesting to know if the CDF of the Cauchy distribution can be obtained as a limit of the distribution of values of

![]() $c_a^\triangleright, c_a^\triangleleft$

, appropriately normalized, as

$c_a^\triangleright, c_a^\triangleleft$

, appropriately normalized, as

![]() $a\to -1$

; in other words, if for some scaling factor

$a\to -1$

; in other words, if for some scaling factor

![]() $\gamma(a)>0$

, we have

$\gamma(a)>0$

, we have

Indeed, this would match the case

![]() $a=-1$

(weight zero), for which

$a=-1$

(weight zero), for which

![]() $c_{-1}(x)$

are the Dedekind sums: it is proved in [Reference VardiVar93] (see [Reference Bettin and DrappeauBD22, § 9.4] for another argument) that the values

$c_{-1}(x)$

are the Dedekind sums: it is proved in [Reference VardiVar93] (see [Reference Bettin and DrappeauBD22, § 9.4] for another argument) that the values

![]() $c_{-1}(x)$

tend to distribute according to a Cauchy distribution when x is picked at random among rationals of denominators at most Q, as

$c_{-1}(x)$

tend to distribute according to a Cauchy distribution when x is picked at random among rationals of denominators at most Q, as

![]() $Q\to\infty$

.

$Q\to\infty$

.

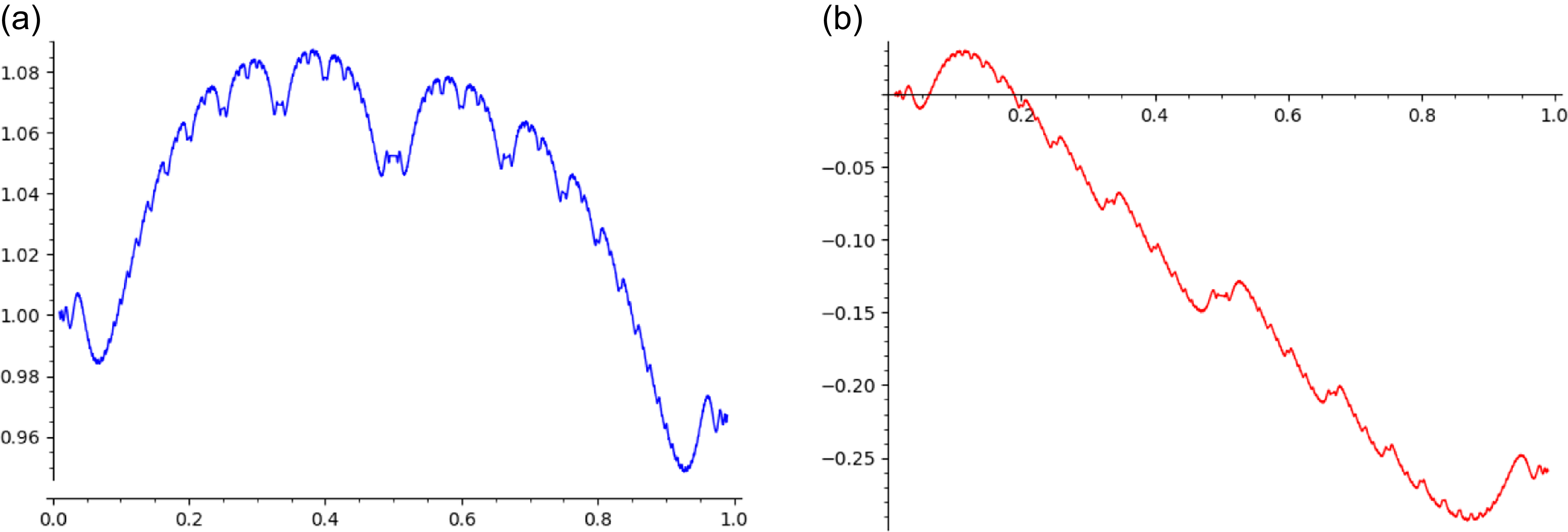

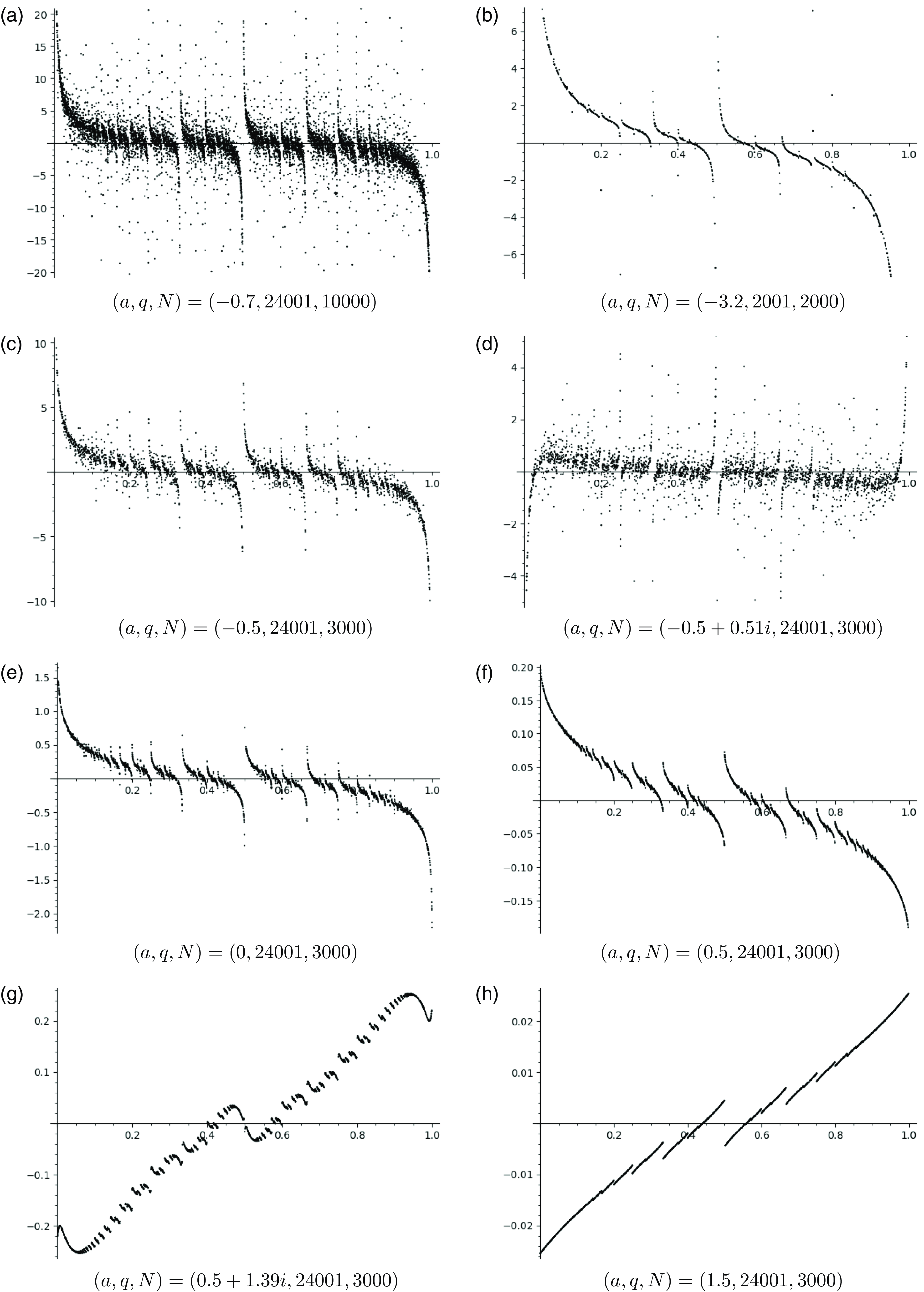

In Figure 4 we present the plots of the real part of

![]() $c_a^\triangleleft$

and

$c_a^\triangleleft$

and

![]() $c_a^\triangleright$

for various values of a. The relevant period function

$c_a^\triangleright$

for various values of a. The relevant period function

![]() $h(x)=h_a(x)$

roughly satisfies

$h(x)=h_a(x)$

roughly satisfies

![]() $h(x) \sim \kappa(a) x^{-1} + O(1)$

for some constant

$h(x) \sim \kappa(a) x^{-1} + O(1)$

for some constant

![]() $\kappa(a)$

, see (4.11) later. When

$\kappa(a)$

, see (4.11) later. When

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(a)<-1$

, we witness a rise in regularity in

$\operatorname{Re}(a)<-1$

, we witness a rise in regularity in

![]() $c_a^\triangleleft$

as

$c_a^\triangleleft$

as

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(a)$

decreases, but without reaching full continuity, due to the fact that

$\operatorname{Re}(a)$

decreases, but without reaching full continuity, due to the fact that

![]() $h_a$

has a pole at 0. When

$h_a$

has a pole at 0. When

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(a)>0$

, Corollary 1.14 shows that the map

$\operatorname{Re}(a)>0$

, Corollary 1.14 shows that the map

![]() $c_a^\triangleright$

is continuous at irrationals, and when

$c_a^\triangleright$

is continuous at irrationals, and when

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(a)>1$

, that it has derivative

$\operatorname{Re}(a)>1$

, that it has derivative

![]() $-a\zeta(1-a)/\pi$

almost everywhere. In Figure 4h, we have

$-a\zeta(1-a)/\pi$

almost everywhere. In Figure 4h, we have

![]() $a=1.5$

and

$a=1.5$

and

![]() $-a\zeta(1-a)/\pi \approx 0.09926$

.

$-a\zeta(1-a)/\pi \approx 0.09926$

.

Figure 4. Sample points of

![]() $c_a$

at N points of denominator q.

$c_a$

at N points of denominator q.

1.4 Notation

1.4.1 General notation.

We set the following general notation:

-

–

$\nu$

is the Lebesgue measure on [0, 1];

$\nu$

is the Lebesgue measure on [0, 1]; -

–

$b_j(x)$

is the jth continued fraction coefficient of x;

$b_j(x)$

is the jth continued fraction coefficient of x; -

–

$\textrm{Num}(x)$

and

$\textrm{Num}(x)$

and

$\operatorname{Den}(x)$

are the numerator and denominator of a rational number x;

$\operatorname{Den}(x)$

are the numerator and denominator of a rational number x; -

–

$\mu(c_1, \dotsc, c_\ell)$

is the Lebesgue measure of the ‘cylinder set’

$\mu(c_1, \dotsc, c_\ell)$

is the Lebesgue measure of the ‘cylinder set’

$J(c_1, \dotsc, c_\ell)$

defined at (3.10);

$J(c_1, \dotsc, c_\ell)$

defined at (3.10); -

– notation using the letters f, g will typically denote quantum modular forms;

-

– notation using the letter h will denote period functions;

-

– the superscripts

$f^\triangleright$

and

$f^\triangleright$

and

$f^\triangleleft$

refer to continuous extensions defined in (1.3), (1.6), (1.7) or (1.8);

$f^\triangleleft$

refer to continuous extensions defined in (1.3), (1.6), (1.7) or (1.8); -

– T denotes the Gauss map (cf. the next section);

-

– w and

$w_j$

refer to products of iterates of the Gauss map defined in (2.12) and (2.19);

$w_j$

refer to products of iterates of the Gauss map defined in (2.12) and (2.19); -

–

$\vartheta_j$

is a root of unity defined in (2.27);

$\vartheta_j$

is a root of unity defined in (2.27); -

– the sets

$\mathfrak{T}(B)$

,

$\mathfrak{T}(B)$

,

$\mathfrak{S}$

,

$\mathfrak{S}$

,

$\mathfrak{A}_q$

and

$\mathfrak{A}_q$

and

$\mathfrak{T}_q$

are defined in Lemmas 2.2, 3.1 and 3.2;

$\mathfrak{T}_q$

are defined in Lemmas 2.2, 3.1 and 3.2; -

– V(B, m, x) and

$\Delta_\lambda(m)$

are defined in (2.6) and (2.7), respectively;

$\Delta_\lambda(m)$

are defined in (2.6) and (2.7), respectively; -

–

$\mathscr{S}(\lambda)$

is the property defined in Definition 2.4.

$\mathscr{S}(\lambda)$

is the property defined in Definition 2.4.

Throughout the paper, we use the Vinogradov notation

![]() $A\ll B$

to mean

$A\ll B$

to mean

![]() $A = O(B)$

. We denote

$A = O(B)$

. We denote

![]() $\varpi = {(1 + \sqrt{5})}/{2}$

to be the golden ratio.

$\varpi = {(1 + \sqrt{5})}/{2}$

to be the golden ratio.

1.4.2 The Gauss map, partial quotients, partial denominators.

Let

![]() $T : \mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\{0\} \to [0, 1)$

,

$T : \mathbb{R}\smallsetminus\{0\} \to [0, 1)$

,

![]() $T(x):=\{1/x\}$

be the Gauss map,

$T(x):=\{1/x\}$

be the Gauss map,

![]() $T^i$

its ith iterate. For

$T^i$

its ith iterate. For

![]() $x\in\mathbb{Q}$

, we let

$x\in\mathbb{Q}$

, we let

![]() $r:=r(x)$

be the minimum non-negative integer such that

$r:=r(x)$

be the minimum non-negative integer such that

![]() $T^{r}(x)=0$

and, for

$T^{r}(x)=0$

and, for

![]() $0\leqslant j < r$

, we write

$0\leqslant j < r$

, we write

![]() $T^j(x)$

in simplest terms as

$T^j(x)$

in simplest terms as

In particular, we have

where

![]() $\operatorname{Den}(x)$

is the denominator of x. Whenever

$\operatorname{Den}(x)$

is the denominator of x. Whenever

![]() $u_{r-1}(x)>1$

, we also define

$u_{r-1}(x)>1$

, we also define

which will be convenient to change the length of the continued fraction (CF) expansion. In the terminology of [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY97], with the value

![]() $\alpha = 1$

, we have

$\alpha = 1$

, we have

![]() $u_j(x) = \operatorname{Den}(x) \beta_{j+1}(x)$

. Thus, from [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY97, Proposition 1.4.(iv)] we deduce

$u_j(x) = \operatorname{Den}(x) \beta_{j+1}(x)$

. Thus, from [Reference Marmi, Moussa and YoccozMMY97, Proposition 1.4.(iv)] we deduce

We will also use the following other decomposition. Given

![]() $y \in \mathbb{Q}\cap (0, 1)$

and writing uniquely y as its CF expansion

$y \in \mathbb{Q}\cap (0, 1)$

and writing uniquely y as its CF expansion

with s odd, we define

Equivalently,

![]() $v_j(y) = \operatorname{Den}([0; c_j, \dotsc, c_1])$

. Note that, with

$v_j(y) = \operatorname{Den}([0; c_j, \dotsc, c_1])$

. Note that, with

![]() $\overline{y} = [0; c_s, \dotsc, c_1]$

, we have

$\overline{y} = [0; c_s, \dotsc, c_1]$

, we have

and as such

We refer to Khinchin’s book [Reference KhintchineKhi63] and to the survey [Reference Flajolet, Vallée and VardiFVV] for additional information about continued fractions.

2. Extending the domain of quantum modular forms

In this section we prove Theorems 1.1, 1.2, 1.4 and 1.5.

2.1 Iteration of the reciprocity formula

First, we notice that by Euclid’s algorithm, any QMF f of level 1 is determined by h and its value at 0. Indeed, by repeatedly applying (1.2) and periodicity, we obtain, for

![]() $x=\frac aq\in[0,1)$

in reduced form,

$x=\frac aq\in[0,1)$

in reduced form,

\begin{equation} f(x)=\sum_{j=0}^{r-1}\bigg(\prod_{i=0}^{j-1}T^{i}(x)\bigg)^{\!{-}k} h((-1)^{j}T^j(x))+q^{k} f(0).\end{equation}

\begin{equation} f(x)=\sum_{j=0}^{r-1}\bigg(\prod_{i=0}^{j-1}T^{i}(x)\bigg)^{\!{-}k} h((-1)^{j}T^j(x))+q^{k} f(0).\end{equation}

Notice that we used that

![]() $\prod_{i=0}^{r-1}T^{i}(x)=1/q$

.

$\prod_{i=0}^{r-1}T^{i}(x)=1/q$

.

The above quantities are naturally expressed in terms of continued fractions. Indeed, if

![]() $x\in(0,1)$

, then the length of its CF expansion

$x\in(0,1)$

, then the length of its CF expansion

![]() $x=[0;b_1,\ldots,b_{r}]$

with minimal length (i.e.

$x=[0;b_1,\ldots,b_{r}]$

with minimal length (i.e.

![]() $b_{r}\neq1$

if

$b_{r}\neq1$

if

![]() $r>1$

) is r. Also, for

$r>1$

) is r. Also, for

![]() $0\leqslant j\leqslant r$

we have

$0\leqslant j\leqslant r$

we have

![]() $q \prod_{i=0}^{j-1}T^{i}(x)=(\prod_{i=j}^{r-1}T^{i}(x))^{-1}$

is the denominator

$q \prod_{i=0}^{j-1}T^{i}(x)=(\prod_{i=j}^{r-1}T^{i}(x))^{-1}$

is the denominator

![]() $u_{j}(x)$

defined in (1.15). Notice also that

$u_{j}(x)$

defined in (1.15). Notice also that

![]() $u_0(x)=q$

. Thus, abbreviating

$u_0(x)=q$

. Thus, abbreviating

![]() $u_j = u_j(x)$

, we can then rewrite (2.1) as

$u_j = u_j(x)$

, we can then rewrite (2.1) as

\begin{equation} f(x)=\sum_{j=0}^{r-1}\bigg(\frac{u_j}{u_0}\bigg)^{\!{-}k} h\bigg((-1)^{j}\frac{u_{j+1}}{u_{j}}\bigg) + u_0^{k} f(0).\end{equation}

\begin{equation} f(x)=\sum_{j=0}^{r-1}\bigg(\frac{u_j}{u_0}\bigg)^{\!{-}k} h\bigg((-1)^{j}\frac{u_{j+1}}{u_{j}}\bigg) + u_0^{k} f(0).\end{equation}

This formula holds also if r is formally replaced by

![]() $r+1$

, which corresponds to expressing

$r+1$

, which corresponds to expressing

![]() $x = [0;b_1,\ldots,b_{r}]$

rather as

$x = [0;b_1,\ldots,b_{r}]$

rather as

![]() $[0; b_1, \dotsc, b_r - 1, 1]$

, since the additional term in (2.2) is

$[0; b_1, \dotsc, b_r - 1, 1]$

, since the additional term in (2.2) is

by (1.2) and periodicity.

Finally, we deduce another variant of (2.2). First, we notice that if

![]() $[0;b_1,\ldots,b_r]$

is the CF expansion of

$[0;b_1,\ldots,b_r]$

is the CF expansion of

![]() $x\neq0$

with r odd, then

$x\neq0$

with r odd, then

![]() $\overline x=[0;b_r,\ldots,b_1]$

. In particular, after the change of variables

$\overline x=[0;b_r,\ldots,b_1]$

. In particular, after the change of variables

![]() $r\to r-j$

, (2.2) can be rewritten as

$r\to r-j$

, (2.2) can be rewritten as

where, for

![]() $y=[0;c_1,\ldots,c_r]$

with r odd, and the notation (1.17),

$y=[0;c_1,\ldots,c_r]$

with r odd, and the notation (1.17),

\begin{equation} \Psi(y):=\sum_{j=1}^{r}v_{j}^{-k}h\bigg((-1)^{j-1}\frac{v_{j-1}}{v_{j}}\bigg)+f(0).\end{equation}

\begin{equation} \Psi(y):=\sum_{j=1}^{r}v_{j}^{-k}h\bigg((-1)^{j-1}\frac{v_{j-1}}{v_{j}}\bigg)+f(0).\end{equation}

From the expansions (2.2) and (2.5), and the fact that both quantities

![]() $u_j/u_0$

and

$u_j/u_0$

and

![]() $v_j^{-1}$

decrease exponentially fast with j, we see the difference of behavior according to the sign of

$v_j^{-1}$

decrease exponentially fast with j, we see the difference of behavior according to the sign of

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)$

, and the relevance of switching x to

$\operatorname{Re}(k)$

, and the relevance of switching x to

![]() $\overline x$

when

$\overline x$

when

![]() $\operatorname{Re}(k)>0$

.

$\operatorname{Re}(k)>0$

.

Finally, we need the following simple fact.

Lemma 2.1. Let

![]() $x\in\mathbb{Q}$

. Then, there exists a neighborhood

$x\in\mathbb{Q}$

. Then, there exists a neighborhood

![]() $I_x$

of x such that

$I_x$

of x such that

![]() $r(y)\geqslant r(x)+1$

for all

$r(y)\geqslant r(x)+1$

for all

![]() $y\in I_x\smallsetminus\{x\}$

.

$y\in I_x\smallsetminus\{x\}$

.

Proof. The statement is immediate if

![]() $x\in\mathbb{Z}$

. Now let

$x\in\mathbb{Z}$

. Now let

![]() $x=[b_0;b_1,\ldots,b_r]\in\mathbb{Q}\smallsetminus \mathbb{Z}$

with

$x=[b_0;b_1,\ldots,b_r]\in\mathbb{Q}\smallsetminus \mathbb{Z}$

with

![]() $r:=r(x)$

. In particular,

$r:=r(x)$

. In particular,

![]() $b_r>1$

. Assume r is odd. Then the statement holds for

$b_r>1$

. Assume r is odd. Then the statement holds for

![]() $I_x=(L_x,R_x)$

, where

$I_x=(L_x,R_x)$

, where

![]() $L_x=[0;b_1,\ldots,b_r+1]$

,

$L_x=[0;b_1,\ldots,b_r+1]$

,

![]() $R_x=[0;b_1,\ldots,b_r-1]$

. Indeed, if

$R_x=[0;b_1,\ldots,b_r-1]$

. Indeed, if

![]() $y\in(L_x,x)$

then

$y\in(L_x,x)$

then

![]() $y=[0;b_1,\ldots,b_r,\alpha]$

for some

$y=[0;b_1,\ldots,b_r,\alpha]$

for some

![]() $\alpha\in\mathbb{R}_{>1}$

, whereas if

$\alpha\in\mathbb{R}_{>1}$

, whereas if

![]() $y\in(x,R_x)$

then

$y\in(x,R_x)$

then

![]() $y=[0;b_1,\ldots,b_r-1,\alpha]$

for some

$y=[0;b_1,\ldots,b_r-1,\alpha]$

for some

![]() $\alpha\in\mathbb{R}_{>1}$

. In either case

$\alpha\in\mathbb{R}_{>1}$

. In either case

![]() $T^{r}(y)=1/\alpha \neq0$

and thus

$T^{r}(y)=1/\alpha \neq0$

and thus

![]() $r(y)>r$

. The case of r even is identical with the role of

$r(y)>r$

. The case of r even is identical with the role of

![]() $L_x$

and

$L_x$

and

![]() $R_x$

reversed.

$R_x$

reversed.

2.2 Continuity almost everywhere and extension

In this section, we state and prove a technical proposition which will be helpful when extending f almost everywhere in Theorems 1.2 and 1.5.

We first need the following lemma, which follows readily from a result of Khinchin [Reference KhintchineKhi63, Theorem 30]. In the following we will use the notation

![]() $r(x)=\infty$

if

$r(x)=\infty$

if

![]() $x\notin\mathbb{Q}$

.

$x\notin\mathbb{Q}$

.

Lemma 2.2. For each

![]() $B>0$

, let

$B>0$

, let

The set

![]() $\mathfrak{T}(B)$

is invariant under

$\mathfrak{T}(B)$

is invariant under

![]() $x\mapsto x+1$

. Moreover,

$x\mapsto x+1$

. Moreover,

![]() $\nu(\mathfrak{T}(B)\cap[0, 1]) = 1 + o(1)$

as

$\nu(\mathfrak{T}(B)\cap[0, 1]) = 1 + o(1)$

as

![]() $B\to\infty$

and the set

$B\to\infty$

and the set

is of full Lebesgue measure.

Proof. By [Reference KhintchineKhi63, Theorem 30] one deduces that

![]() $\mathfrak{S}$

has full measure. Since

$\mathfrak{S}$

has full measure. Since

![]() $ \mathfrak{T}(B')\subseteq \mathfrak{T}(B)$

if

$ \mathfrak{T}(B')\subseteq \mathfrak{T}(B)$

if

![]() $0<B'\leqslant B$

, one then deduces that

$0<B'\leqslant B$

, one then deduces that

![]() $\nu(\mathfrak{T}(B)\cap[0, 1]) = 1 + o(1)$

as

$\nu(\mathfrak{T}(B)\cap[0, 1]) = 1 + o(1)$

as

![]() $B\to\infty$

. Finally, the invariance under

$B\to\infty$

. Finally, the invariance under

![]() $x\mapsto x+1$

is clear since the conditions in

$x\mapsto x+1$

is clear since the conditions in

![]() $\mathfrak{T}(B)$

don’t involve

$\mathfrak{T}(B)$

don’t involve

![]() $b_0$

.

$b_0$

.

Remark 2.3. Lemma 2.2 holds with the condition

![]() $b_j(x) \leqslant \max(B, j(\log j)^2)$

replaced by

$b_j(x) \leqslant \max(B, j(\log j)^2)$

replaced by

![]() $b_j(x) \leqslant \max(B,a_j)$

for any non-negative increasing sequence

$b_j(x) \leqslant \max(B,a_j)$

for any non-negative increasing sequence

![]() $(a_j)_j$

such that

$(a_j)_j$

such that

![]() $\sum_{j\geqslant 1}a_j^{-1}$

converges. For our later purposes we will also need that

$\sum_{j\geqslant 1}a_j^{-1}$

converges. For our later purposes we will also need that

![]() $a_j\ll_\varepsilon j^{1+\varepsilon}$

for all

$a_j\ll_\varepsilon j^{1+\varepsilon}$

for all

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

. Making the explicit choice

$\varepsilon>0$

. Making the explicit choice

![]() $a_j=j(\log j)^2$

simplifies the notation in later computations.

$a_j=j(\log j)^2$

simplifies the notation in later computations.

Given

![]() $B>0$

, an integer

$B>0$

, an integer

![]() $m\geqslant 1$

and a number

$m\geqslant 1$

and a number

![]() $x\in \mathfrak{T}(B)$

, define

$x\in \mathfrak{T}(B)$

, define

the set of all rationals in

![]() $\mathfrak{T}(B)$

whose first m coefficients coincide with those of x.

$\mathfrak{T}(B)$

whose first m coefficients coincide with those of x.

Definition 2.4 (Property

![]() $\mathscr{S}(\lambda)$

.) We say that

$\mathscr{S}(\lambda)$

.) We say that

![]() $f:\mathbb{Q}\to\mathbb{C}$

has the property

$f:\mathbb{Q}\to\mathbb{C}$

has the property

![]() $\mathscr{S}(\lambda)$

if the quantity

$\mathscr{S}(\lambda)$

if the quantity

satisfies

as

![]() $m\to\infty$

.

$m\to\infty$

.

Proposition 2.5. Let

![]() $\lambda>1$

, and assume that f has the property

$\lambda>1$

, and assume that f has the property

![]() $\mathscr{S}(\lambda)$

. Then for any

$\mathscr{S}(\lambda)$

. Then for any

![]() $x\in \mathfrak{S} \smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

, the limit

$x\in \mathfrak{S} \smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

, the limit

exists for any

![]() $B>0$

such that

$B>0$

such that

![]() $x\in \mathfrak{T}(B)\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. Moreover, let

$x\in \mathfrak{T}(B)\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. Moreover, let

![]() $m\in\mathbb{N}$

and

$m\in\mathbb{N}$

and

![]() $B>0$

be given with

$B>0$

be given with

![]() $m \geqslant B^{1/\lambda}$

, and define

$m \geqslant B^{1/\lambda}$

, and define

![]() $f^*(x) := f(x)$

for

$f^*(x) := f(x)$

for

![]() $x\in\mathbb{Q}$

. Then uniformly in

$x\in\mathbb{Q}$

. Then uniformly in

![]() $x, x' \in \mathfrak{T}(B)$

satisfying

$x, x' \in \mathfrak{T}(B)$

satisfying

![]() $r(x), r(x')\geqslant m$

and

$r(x), r(x')\geqslant m$

and

![]() $b_j(x) = b_j(x')$

for

$b_j(x) = b_j(x')$

for

![]() $j\leqslant m$

, we have

$j\leqslant m$

, we have

where the rate of decay may depend on

![]() $\lambda$

, but not on B.

$\lambda$

, but not on B.

Remark 2.6. Let

![]() $x\in \mathfrak{T}(B)\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. Since

$x\in \mathfrak{T}(B)\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. Since

![]() $\mathfrak{T}(B') \subset \mathfrak{T}(B)$

for

$\mathfrak{T}(B') \subset \mathfrak{T}(B)$

for

![]() $B \geqslant B' > 0$

, from (2.9) we also get

$B \geqslant B' > 0$

, from (2.9) we also get

![]() $f^*(x) = \lim_{y\in\mathbb{Q}\cap \mathfrak{T}(B'), y\to x} f(y)$

, for any

$f^*(x) = \lim_{y\in\mathbb{Q}\cap \mathfrak{T}(B'), y\to x} f(y)$

, for any

![]() $0<B'<B$

with

$0<B'<B$

with

![]() $x\in \mathfrak{T}(B')\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. In particular, the existence of the limit implies that its value

$x\in \mathfrak{T}(B')\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. In particular, the existence of the limit implies that its value

![]() $f^*(x)$

is independent of B. Notice that the rate of convergence, however, might depend on it.

$f^*(x)$

is independent of B. Notice that the rate of convergence, however, might depend on it.

Proof of Proposition 2.5. Let

![]() $x\in \mathfrak{T}(B)\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. We wish to show that the limit (2.9) exists. By Cauchy’s criterion, it suffices to show that

$x\in \mathfrak{T}(B)\smallsetminus\mathbb{Q}$

. We wish to show that the limit (2.9) exists. By Cauchy’s criterion, it suffices to show that

\begin{align} \lim_{\varepsilon\to 0^+} \sup_{\substack{x', x'' \in \mathbb{Q} \cap\mathfrak{T}(B) \\ {| {x'-x} |}, {| {x''-x} |} \leqslant \varepsilon}} {| {f(x') - f(x'')} |} = 0. \end{align}

\begin{align} \lim_{\varepsilon\to 0^+} \sup_{\substack{x', x'' \in \mathbb{Q} \cap\mathfrak{T}(B) \\ {| {x'-x} |}, {| {x''-x} |} \leqslant \varepsilon}} {| {f(x') - f(x'')} |} = 0. \end{align}

Let

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

. Since

$\varepsilon>0$

. Since

![]() $x\not\in\mathbb{Q}$

, we may find

$x\not\in\mathbb{Q}$

, we may find

![]() $m\in\mathbb{N}$

such that for any

$m\in\mathbb{N}$

such that for any

![]() $y\in\mathbb{Q}\cap[x-\varepsilon, x+\varepsilon]$

, then

$y\in\mathbb{Q}\cap[x-\varepsilon, x+\varepsilon]$

, then

![]() $r(y)>m$

and

$r(y)>m$

and

![]() $b_j(y) = b_j(x)$

for all

$b_j(y) = b_j(x)$

for all

![]() $j\leqslant m$

. Clearly,

$j\leqslant m$

. Clearly,

![]() $m\to\infty$

as

$m\to\infty$

as

![]() $\varepsilon\to0^+.$

In particular, we can assume

$\varepsilon\to0^+.$

In particular, we can assume

![]() $m\geqslant B^{1/\lambda}$

so that

$m\geqslant B^{1/\lambda}$

so that

![]() $\mathfrak{T}(B) \subset \mathfrak{T}(m^\lambda)$

. Thus,

$\mathfrak{T}(B) \subset \mathfrak{T}(m^\lambda)$

. Thus,

![]() $x\in\mathfrak{T}(m^\lambda)$

and

$x\in\mathfrak{T}(m^\lambda)$

and

![]() $\mathbb{Q}\cap[x-\varepsilon, x+\varepsilon]\cap \mathfrak{T}(B)\subseteq V(m^\lambda,m,x)$

and (2.11) follows from (2.8).

$\mathbb{Q}\cap[x-\varepsilon, x+\varepsilon]\cap \mathfrak{T}(B)\subseteq V(m^\lambda,m,x)$

and (2.11) follows from (2.8).

It remains to show (2.10). Let

![]() $x, x' \in \mathfrak{T}(B)$

,

$x, x' \in \mathfrak{T}(B)$

,

![]() $m \geqslant B^{1/\lambda}$

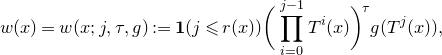

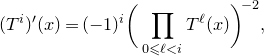

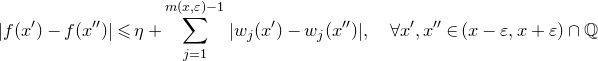

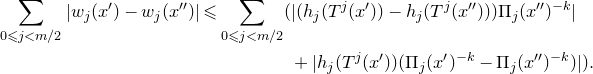

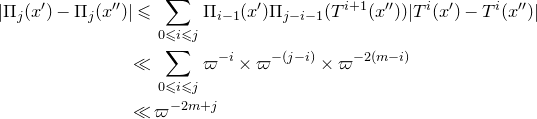

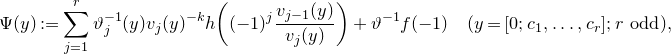

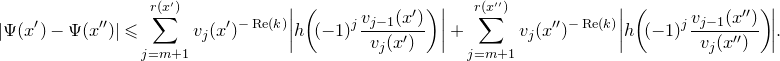

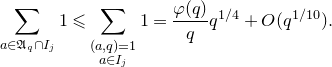

, and for