1. Introduction

In 2021, a variety of Indigenous activists from regions as diverse as Africa, North America, and South America appeared in different international venues for economics, climate change, and criminal law to assert claims regarding the crime of ecocide. Specifically, Indigenous representatives engaged with the International Criminal Court (ICC), the 26th Conference of the Parties for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),Footnote 1 and the World Economic Forum (WEF) to call for greater attention to ecocide in identifying environmental harm.Footnote 2 While acting separately from each other, they expressed common concerns over the destruction of the environment and the resulting impacts upon Indigenous communities. Such concerns are not abstract, with scholarly and policy literature recognizing that the close connections between Indigenous communities with their surrounding environments place Indigenous societies at elevated levels of vulnerability to environmental harm relative to other populations.Footnote 3

These claims of ecocide by Indigenous activists suggest an underlying belief that the concept can assist Indigenous interests in the environment. However, they also raise questions about the extent to which ecocide is appropriate for Indigenous peoples. In particular, they incur reflection about, firstly, how definitions of ecocide can extend to encompass Indigenous issues and, secondly, the degree to which efforts to include ecocide in international criminal law can work to serve Indigenous interests.Footnote 4 The normative tenor of such uncertainty calls for a means of evaluation that can clarify Indigenous sensibilities regarding ecocide.

The present analysis provides an evaluation of ecocide discourse relative to Indigenous interests in the environment. Specifically, the analysis seeks to explore the bases for Indigenous normative concerns regarding ecocide, both in respect of its meaning and its inclusion in international criminal law. It does so by drawing upon Indigenous studies literature to develop a framework that represents Indigenous perspectives, through which it is possible to discern the nuances of Indigenous arguments related to ecocide. The attendant goal is to organize diverse Indigenous approaches to ecocide in ways that assist descriptive understanding of Indigenous positions towards components of ecocide discourse and guide future work to identify prescriptive actions consistent with Indigenous interests. In essence, the article seeks to serve a heuristic function in clarifying Indigenous approaches and to facilitate engagement with Indigenous voices within deliberations over ecocide.

Section 2 begins with a summary of the historical project of ecocide, reviewing the movements to define it and advance it in international criminal law, as well as noting the Indigenous scholarship directed towards its study. Section 3 proceeds to construct a framework that aids comprehension of the range of Indigenous views on ecocide, referencing Indigenous studies literature regarding the connections between Indigenous peoples and the environment. The analysis in Section 4 applies the framework to organize diverse Indigenous concerns towards ecocide, clarifying the components of ecocide discourse that are problematic for Indigenous peoples. Section 5 offers reflections for future research, drawing upon Indigenous studies literature for supplementary guidance that can help subsequent studies to identify actions that align with Indigenous expectations for the environment. Section 6 concludes.

2. Background

The contours of ecocide discourse arise from the social movements that sought to articulate its definition and advance its prohibition in international criminal law.Footnote 5 Arguments for the international criminalization of ecocide first appeared in statements by biologist Arthur Galston in a 1970 Conference on War and National Responsibility in the United States.Footnote 6 While expressed as part of a political movement by American scientists against the Vietnam War,Footnote 7 in ensuing years the concept of ecocide was considered for inclusion in domestic and international criminal law.Footnote 8 These debates led to a draft Ecocide Convention in 1973, produced by Richard Falk, which proposed ecocide as a crime associated with military operations, as opposed to non-military activities such as economic enterprises.Footnote 9 In particular, the text of Falk’s draft Convention defined ecocide as acts which are ‘committed with intent to disrupt or destroy, in whole or in part, a human ecosystem’, where the term ‘acts’ involve military use of weapons of mass destruction, chemical defoliants, bombs and artillery that ‘impair the quality of the soil’ or ‘enhance the prospect of diseases’, bulldozing equipment to destroy forest or cropland, techniques to modify the weather, or forcibly removing ‘human beings or animals from their habitual places of habitation’.Footnote 10

The draft Ecocide Convention 1973 never proceeded to adoption in international law. However, debates over ecocide continued in subsequent decades through domestic movements that articulated their own particular permutations of ecocide.Footnote 11 Concurrently, the United Nations (UN) also dedicated attention to the development of ecocide, with the UN Human Rights Commission’s Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities (Sub-Commission)Footnote 12 contemplating the addition of ecocide to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide 1948,Footnote 13 and the UN International Law Commission (ILC) exploring the placement of ecocide among the crimes recognized by international law.Footnote 14 The Sub-Commission’s work debated various wordings for ecocide, including Falk’s language, but failed to advance ecocide as part of the Genocide Convention 1948.Footnote 15 The ILC discussed harm to the environment as part of the Draft Code of Crimes against the Peace and Security of MankindFootnote 16 and the Draft Articles on State Responsibility for Internationally Wrongful Acts,Footnote 17 but ultimately excluded expression of a dedicated crime for environmental damage in the final versions of both.Footnote 18 Outside the Sub-Commission and the ILC, concerns for the environment persisted within the discourses over international criminal law, with the work for the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal CourtFootnote 19 producing language that articulates war crimes as encompassing ‘wide-spread, long-term, and severe damage to the natural environment’, echoing Falk’s concerns for situations of violent conflict.Footnote 20

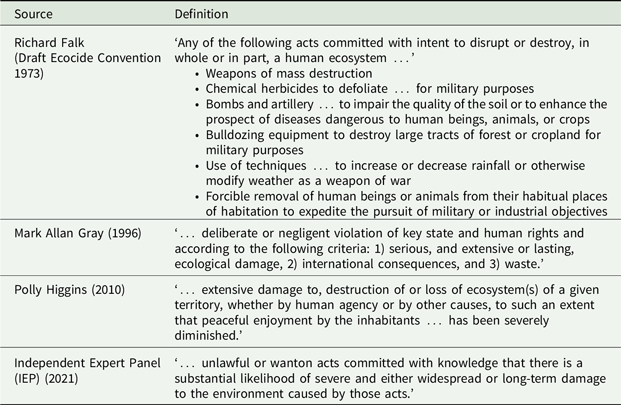

While the UN efforts fell short of installing ecocide within international law, the global discourse accelerated from the 1990s into the 2000s, with prominent proposals coming in 1996 from Mark Allan Gray, in 2010 from Polly Higgins, and in 2021 from the Independent Expert Panel for the Legal Definition of Ecocide (Independent Expert Panel, or IEP).Footnote 21 In brief, Gray asserted ecocide as a ‘deliberate or negligent violation’ of state and human rights that involve ‘1) serious, and extensive or lasting, ecological damage, 2) international consequences, and 3) waste’.Footnote 22 In contrast, Higgins phrased ecocide as ‘extensive damage to, destruction of or loss of ecosystem(s)’ that ‘peaceful enjoyment by inhabitants…has been severely diminished’.Footnote 23 More recently, the IEP articulated a definition of ecocide as ‘unlawful or wanton acts’ committed (i) ‘with knowledge that there is substantial likelihood of severe damage caused by those acts’, and incurring (ii) ‘either widespread or long-term damage’.Footnote 24

A summary of the above definitions for ecocide is presented in Table 1. Select quotations are provided reflecting the points given in preceding discussion, with some components of the original language paraphrased with more succinct wording.

Table 1. Definitions of Ecocide

The aforementioned efforts to characterize ecocide as a crime in international criminal law have drawn extensive critique. The critiques reflect a range of viewpoints, with commentaries appearing from fields such as criminology, law, political ecology, political economy, politics, philosophy, sociology, and visual arts.Footnote 25 The substance of their arguments encompasses issues such as the deleterious role of capitalism in driving environmental destruction;Footnote 26 tensions posed by a human–nature dichotomy in ecocide discourse, with contestation over ambiguities in discerning what is anthropocentric, ecocentric, or the relationship between the two;Footnote 27 the hazards of assigning victimhood to nature, in that it risks reductionism in understanding the contextual complexities associated with ecosystems and the resulting definition of criminal environmental harm;Footnote 28 and the colonial implications of international systems imposing universalist ideals.Footnote 29

These critiques often invoke Indigenous peoples, directing attention to the dependence of Indigenous societies upon surrounding environments, and their resulting vulnerabilities to environmental damage.Footnote 30 Such scholarship raises concerns over differences in Indigenous conceptualizations of human relationships with the environment relative to ecocide discourse. More specifically, Indigenous peoples tend to hold more holistic conceptions that do not follow the human–nature dualism prevalent in ecocide debates.Footnote 31 Other issues include the challenges of engaging the broad scope of connections between Indigenous peoples and nature, which encompasses worldviews, knowledge production, governance and law, and socio-cultural ordering;Footnote 32 the existence of Indigenous legal orders distinct from non-Indigenous legal systems, with contrasting approaches to environmental and criminal law;Footnote 33 the complexities faced by non-Indigenous legal approaches in addressing Indigenous issues, particularly for doctrinal legal frameworks in articulating environmental crimes accommodating Indigenous concerns;Footnote 34 the occurrence of ecocide as an extension of colonial capitalism that continues an ongoing subjugation of Indigenous peoples;Footnote 35 and the history of law, both domestic and international, in furthering colonial systems that subordinate Indigenous communities, with the attendant risk of ecocide serving to reinforce that legacy.Footnote 36

This literature is particularly vulnerable to issues of positionality – that is, the differences between studies about Indigenous peoples compared with studies by Indigenous peoples. Scholarship about Indigenous peoples refer to works by non-Indigenous voices writing on Indigenous societies. Such scenarios invariably feature Western forms of analysis pursuing claims of objective inquiry, using approaches that explore phenomena in isolation from Indigenous subjectivities.Footnote 37 Critics argue that those forms of study decontextualize Indigenous issues from lived experiences, and in so doing dehumanize Indigenous peoples by denying their realities.Footnote 38 In contrast, scholarship by Indigenous peoples relates to literature with Indigenous voices speaking on Indigenous issues.Footnote 39 Proponents of the latter assert the value of Indigenous approaches in enriching discourses regarding the environment.Footnote 40 Of particular relevance for deliberations over ecocide in international criminal law, advocates for Indigenous approaches emphasize the existence of Indigenous legal orders concurrent with existing state-based law;Footnote 41 the association of those legal orders with Indigenous systems of knowledge;Footnote 42 and the bases of that knowledge, and hence their attendant legal orders, in Indigenous relationships with the environment.Footnote 43 Such Indigenous perspectives respond to and further scholarly calls for greater reflexivity so as to expose the subjectivities underlying claims of objectivity in Western-based knowledge systems, to encourage greater attention to the normative issues arising from the suppression of alternative forms of knowledge, and to foster more equitable collaborations between diverse forms of knowledge production.Footnote 44

In keeping with the preceding admonitions, the orientation of the present analysis is to build upon the scholarship on Indigenous peoples and ecocide by centring reflection around perspectives articulated by Indigenous peoples vis-à-vis ecocide discourse. Specifically, the article seeks to promote Indigenous approaches by involving works containing Indigenous voices drawn from the field of Indigenous studies. To promote appreciation for the diversity of Indigenous viewpoints, the analysis clarifies the nuances of different Indigenous perspectives towards ecocide through a framework that organizes the complexities of their arguments into more identifiable elements of distinction. In constructing such a framework, the analysis follows the guidance of Indigenous scholarship on Indigenous forms of understanding, particularly from the 2021 edited volume on critical Indigenous studies produced by Brendan Hokowhitu, Aileen Moreton-Robinson, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Chris Andersen, and Steve Larkin.Footnote 45 In addition, the author’s own position is that of an Indigenous scholar with experience in bridging Indigenous and non-Indigenous approaches in international law and policy discourses, with a motivation to follow the precedents set by scholars such as Fikrit Berkes,Footnote 46 Adriana Moreno-Cely,Footnote 47 Tyler Jessen,Footnote 48 Kate Harriden,Footnote 49 Michael Hart,Footnote 50 Lynn Chi Lee,Footnote 51 and Siri Veland,Footnote 52 who advocate more equitable inclusion of Indigenous voices in wider deliberations over the environment.

The analysis acknowledges arguments that see the concept of Indigeneity as a social construct, either as a colonial imposition of hegemonic powers or as a product of agency by groups of peoples.Footnote 53 As a social construct, Indigeneity can be political in terms of it being contested as well as instrumental in the sense that it is used to serve ulterior goals.Footnote 54 As a consequence, claims to Indigenous status reflect the interests of its claimants, such that the meaning of Indigeneity varies by their individual contexts. The resulting fluidity is compounded by international legal discourse, which holds no consensus definition for Indigeneity and instead displays different interpretations across various instruments and institutions.Footnote 55 The present article, however, treats such issues as a feature of the complexities in Indigenous studies and hence as a contributor to the richness in Indigenous perspectives. In pursuing a framework to organize the nuances of diverse Indigenous arguments, the analysis seeks to provide readers with the capacity to clarify assorted perspectives that may claim to hold Indigenous status. Further, in highlighting Indigenous voices, the analysis adopts an inclusive orientation which is receptive to any source that self-identifies as Indigenous.

The point of the analysis is not for an entire Indigenous rejection of existing ecocide debates, but rather for an understanding of Indigenous perspectives in ways that enrich current ecocide discussions. In essence, the analysis works to support the presence of Indigenous studies scholarship in ecocide discourse. In referencing Indigenous studies, the analysis strives to fulfil the goal of centring Indigenous voices by emphasizing sources from Indigenous authors, with supplementary works coming from non-Indigenous scholars. The subsequent sections assert Indigenous studies literature as offering a body of Indigenous sources that represent Indigenous approaches to topics such as ecocide. In particular, the analysis performs a heuristic function in terms of identifying a framework that facilitates greater understanding of Indigenous normative concerns regarding two components of ongoing ecocide discussions: firstly, the definition of ecocide and, secondly, its inclusion in international criminal law.

3. A Framework for Organizing Indigenous Approaches on Ecocide

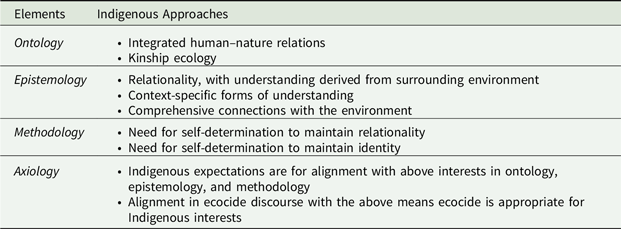

In considering the range of Indigenous perspectives that relate to ecocide, it is helpful to reference antecedent efforts for more general theoretical study of Indigenous approaches to knowledge. Particular guidance comes from critical Indigenous studies literature, with notable works by Kate Harriden,Footnote 56 Ella Henry and Dennis Foley,Footnote 57 and Brendan Hokowhitu and co-authorsFootnote 58 organizing deliberations over Indigenous forms of understanding along the elements in Indigenous perspectives that reflect aspects of ontology, epistemology, methodology, and axiology.Footnote 59 Ontology relates to identification of the phenomenon that is the focus of study; epistemology refers to the ways of reasoning applied by inquiry into a chosen phenomenon; methodology denotes the activities that comprise the conduct of inquiry; and axiology considers the norms and values directing the work of inquiry.Footnote 60 Collectively, the aforementioned categories provide a means to identify components of Indigenous studies discourse that can form a framework for analysis. The following subsections follow such guidance to delineate the elements of Indigenous studies arguments that together illustrate Indigenous approaches to ecocide.

3.1. Ontology

Within Indigenous critiques of ecocide discourse, it is possible to ascertain ontology regarding Indigenous conceptions of human–nature relations. In particular, in distinguishing their arguments from ecocide discourse, Indigenous critics note the contrast between prevailing ecocide discussions that display tendencies to employ human–nature dichotomies in deliberations, versus Indigenous approaches that reflect more holistic considerations that encompass humans and the environment together.Footnote 61 Such conceptualizations feature in broader Indigenous studies literature, with examples of works from Humberto Ortega-Villaseñor,Footnote 62 Mamaweswen Niigaaniin and Timothy MacNeill,Footnote 63 Irene Watson,Footnote 64 Laura Westra,Footnote 65 and Deborah Bird RoseFootnote 66 detailing the integration of Indigenous peoples with their surrounding environments. Such findings are complemented by studies from scholars such as Gabriela Loayza and co-authors,Footnote 67 Deborah McGregor,Footnote 68 Jamie Ojeda and co-authors,Footnote 69 and Alexandre Suralles and Pedro Hierro.Footnote 70 These scholars share similar findings that Indigenous societies see human–nature connections as mutually influential, with reciprocal interconnections between human communities and the environment in which a change in one entails a corresponding change in the other.Footnote 71 For some Indigenous peoples, humans and the environment are immersed in kinship networks in which they are indistinguishable from each other, to the extent that humans hold the same status as flora or fauna in the determination of harm.Footnote 72 The collective tenor of Indigenous perspectives contrasts with more dominant non-Indigenous approaches, which employ more anthropocentric frameworks of property, economic markets, or authoritative dominion that accord the environment with status subordinate to human control.Footnote 73

Some caution should be noted in that the discourse over Indigenous–environment connections is contested, with critics questioning the claims of Indigenous societies as holding uniquely harmonious relationships with nature.Footnote 74 However, while Indigenous studies may pose divergent assertions regarding the manner of consonance between Indigenous peoples and the environment, there is a common underlying recognition of the close ties between Indigenous communities and their surrounding environmental contexts. In particular, the present analysis follows the commentaries of scholars such as Aileen Moreton-Robinson,Footnote 75 Christine Black,Footnote 76 Rebecca Tsosie,Footnote 77 and Irene Watson,Footnote 78 who observe that their claims are not for romantic notions of Indigenous peoples as living in harmony with nature, but instead about deeper perceptions regarding the broad scope of mutual relationships through which Indigenous societies and the natural world interact. Under such advice, it is reductionist to frame Indigenous peoples as being purely harmonious with nature, and it is more appropriate to consider Indigenous conceptions of human–nature relationships as involving complex understandings of the wide range of ways by which Indigenous societies and the natural world mutually influence each other.Footnote 79

3.2. Epistemology

With regard to epistemology, Indigenous assertions of integrated human–nature connections entail forms of reasoning grounded in the interactive dynamics between humans and the environment.Footnote 80 In essence, the character of Indigenous understanding is relational in the sense that it is derived from the conceptions held by each Indigenous community regarding its connections with the natural world around it.Footnote 81 Relationality renders Indigenous perspectives contextual, with the previously noted works of Loayza and co-authors, McGregor, Ojeda and co-authors, and Surallés and Hierro noting the ways in which each Indigenous community conceptualizes its existence in relation to the particular conditions of its surrounding environments.Footnote 82 Such context-specificity means that Indigenous conceptualizations of the self and the world can vary across different Indigenous groups.Footnote 83 The consequent implication is that Indigenous peoples are not monolithic, and are instead diverse. Such diversity means an array of nuances in Indigenous sensibilities of identity, with attendant complexities in their various approaches to understanding human–nature relationships.

In addition, relationality can manifest in various ways, such that human–nature connections can encompass a comprehensive scope of factors comprising Indigenous realities. In particular, an Indigenous community’s relations with its surrounding environment can appear in its worldviews, beliefs, and values.Footnote 84 Such impacts can extend to direct that community’s political, legal, economic, spiritual, and socio-cultural sensibilities.Footnote 85 To the extent that the aforementioned features contribute to a group’s understanding of itself, they connect the environment to notions of that group’s identity. As argued by scholars such as Christine Black,Footnote 86 Kate Harriden,Footnote 87 Rebecca Tsosie,Footnote 88 Siri Veland,Footnote 89 Irene Watson,Footnote 90 and Patricia Dudgeon and co-authors,Footnote 91 the environment is the base from which Indigenous societies comprehend their existence, with the land being a source of Indigenous norms, laws, and governance; a root of economic and socio-cultural order; an origin of cosmology, metaphysics, and spirituality; a foundation for framing Indigenous expression, teaching, and argumentation; and a repository of Indigenous memory, history, and lessons. In essence, as much as the natural world may serve to sustain subsistence for an Indigenous community, it also functions to define its understanding of itself within a larger universe.Footnote 92 Of particular note for deliberations to criminalize ecocide, Indigenous conceptions of human–nature relationships lead to political-legal orders with more holistic approaches relative to prevailing state and global governance systems.Footnote 93

3.3. Methodology

The above features pose consequences for methodology regarding the conduct of Indigenous inquiry, especially with regard to the issue of self-determination. Indigenous studies literature asserts that Indigenous struggles for self-determination encompass motivations to protect and revitalize Indigenous identities.Footnote 94 To a degree, identities are characterized by distinct forms of reasoning, in the sense that an Indigenous group’s particular conception of reality affects how it sees itself as a distinctive entity within a larger world.Footnote 95 In effect, the continued existence of the identity of a given Indigenous group involves the preservation of its approach to understanding, making Indigenous forms of analysis a primary concern in Indigenous struggles for survival.Footnote 96 Indigenous approaches to understanding, however, are tied to Indigenous relationships with the environment, and so incorporate the environment within Indigenous conceptions of identity.

The relationality between Indigenous understanding and the environment renders the identity of any given Indigenous group specific to its unique experiences with the natural world, effectively placing that group as the sole authority over its conceptualization of itself and its connections to nature.Footnote 97 As argued by scholars encompassing Anna Laing,Footnote 98 Michelle Daigle,Footnote 99 Jeff Corntassel,Footnote 100 Peter Manus,Footnote 101 Humberto Ortega-Villaseñor,Footnote 102 Rebecca Tsosie,Footnote 103 Patricia Dudgeon,Footnote 104 and Laura Westra,Footnote 105 the exercise of authority is an expression of self-determination, such that agendas to preserve Indigenous perspectives regarding the environment call for the promotion of Indigenous authority through the empowerment of their self-determination. As a consequence, Indigenous relationships with the environment are integral to Indigenous movements for self-determination, with sensibilities towards the environment lying within the scope of authority of each Indigenous group over its own identity.

3.4. Axiology

With respect to axiology, it is possible to draw upon the preceding reflections on ontology, epistemology, and methodology as a means of normative assessment in the sense that they circumscribe the parameters of Indigenous expectations for ecocide discourse. Specifically, discussions on ecocide are appropriate for Indigenous peoples to the extent that they align with Indigenous ontologies, epistemologies, and methodologies towards the environment. To begin, in asserting Indigenous conceptions of integrated human–nature relations, Indigenous scholarship eschews discursive frameworks referencing humanity and nature as distinct components. In essence, Indigenous perspectives see the separate considerations of humans and nature as problematic, and seek instead a collapse of the human–nature distinction to pursue more holistic explorations that treat humans and the environment as mutually enmeshed in networks of interaction.Footnote 106 Such perspectives contrast with arguments that call for a balance of human and environmental issues in analysis,Footnote 107 with Indigenous approaches seeing such calls as unsatisfactory because the attention to balance implies a bifurcation between humans and the environment as distinct factors.Footnote 108 Indigenous perspectives also disagree with other arguments that seek to position ecocide as being an ecocentric companion to the anthropocentric concept of genocide, in that the separation of analysis into ecocentric and anthropocentric considerations exacerbates the division of environmental and human concerns that Indigenous ontologies seek to avoid.Footnote 109 For Indigenous critics, a distinction between humans and nature is a false dichotomy, and the presence of that dichotomy in discussions of ecocide move ecocide discourse away from Indigenous preferences.

Next, Indigenous epistemologies do not align with discussions that ignore or suppress the relational character of Indigenous understandings of human–nature relationships. The relationality of Indigenous knowledge, in rendering Indigenous approaches to understanding context-specific to surrounding environments, generates a diversity of Indigenous forms of reasoning tied to distinct conceptions of existence and the natural world. Such diversity challenges universalist aspirations for a single definition of ecocide, not just because it counters the potential for a coherent definition that accommodates the preferences of all peoples, Indigenous or otherwise, but also because it resists efforts for a unified project to produce general progress towards a single definition. In addition, the comprehensive impact of Indigenous conceptions of human–nature relations associates the environment with the full breadth of Indigenous existence, including politics, law, economics, spirituality, and socio-cultural aspects. The reach of human–nature conceptions in Indigenous life extends outside the scope of ecocide discourse, which centres its attention on harm to the environment. Indigenous perspectives, in contrast, would pursue conceptions of ecocide that accommodate diverse Indigenous understandings of human–nature relations and include the broad scope of connections between Indigenous peoples and the environment.

Lastly, the centrality of self-determination for Indigenous peoples places it as a fundamental issue in Indigenous deliberations over ecocide. In essence, Indigenous perspectives find arguments that infringe Indigenous ambitions for self-determination to be problematic. Indigenous studies literature views self-determination as tied to survival, with the preservation of Indigenous identity a core concern for claims of self-determination.Footnote 110 Because Indigenous identity encompasses particular conceptions of human–nature relations, Indigenous understandings of human–nature connections also tie to ambitions for self-determination.Footnote 111 The consequence is that Indigenous interests in the environment, including Indigenous approaches to human–nature relationships, are attendant with Indigenous efforts for self-determination. As a result, discussions on ecocide which do not support self-determination present an ambiguity for Indigenous concerns, and conceptions of ecocide which constrain self-determination constitute a threat to Indigenous ambitions.

The above elements are summarized in Table 2, which identifies each component in association with points of Indigenous perspectives relevant to deliberations over ecocide.

Table 2. Elements of Indigenous Approaches to Ecocide

4. An Indigenous Evaluation of Ecocide

The preceding reflections on Indigenous approaches help to clarify the engagement of Indigenous peoples with ecocide discourse, with the organization into ontology, epistemology, methodology, and axiology providing an analytical framework to identify points of critique raised by Indigenous studies literature. In doing so, the aforementioned framework serves to guide deliberations in ways that respond to Indigenous concerns. In particular, it furthers descriptive comprehension by highlighting nuances in Indigenous perspectives, with the elements of Indigenous approaches raised in the preceding section helping to discern the issues of ecocide discourse that are problematic for Indigenous interests. The following subsections extend the descriptive analysis, employing the components of ontology, epistemology, methodology, and axiology to parse through Indigenous concerns with respect to the deliberations over the definitions of ecocide and the addition of ecocide as a crime in international law.

4.1. Indigenous Concerns regarding Definitions of Ecocide

Applied to the various definitions of ecocide, the framework assembled in the previous discussion functions to delineate the types of issue facing Indigenous peoples for each one. In doing so, it deepens analysis beyond a general critique of ecocide discourse as a whole to a more particular evaluation of the diverse proposals for ecocide as a concept. In essence, it facilitates the assessment of each definition against expectations manifested by Indigenous studies literature.

Starting with Falk’s articulation of ecocide, the language expressed in the draft Ecocide Convention 1973 poses multiple challenges for Indigenous interests.Footnote 112 To a degree, Falk’s use of the term ‘human ecosystem’ offers tentative ontological alignment with Indigenous approaches, in that it suggests an embedding of humans in ecosystems that conceivably conforms to Indigenous conceptions of integrated human–nature relationships. However, Falk’s ascription of harm to situations of armed conflict means a constriction in scope that falls short of Indigenous expectations, which look to impacts on human–nature relationships arising from situations both within and outside armed conflict. Such a narrow focus generates an attendant epistemological issue, in that the restriction to cases of armed conflict incurs an exclusion of situations outside armed conflict, effectively delimiting the reach of context-specificity associated with Indigenous forms of understanding. Further, Falk’s text presents a methodological issue, in that it is ambiguous regarding self-determination. Admittedly, it is possible to construe impacts to human ecosystems as reducing Indigenous capacities for self-sufficient subsistence, and hence as weakening Indigenous autonomy. However, such an inference is subject to contestation, such that the uncertainty by itself is sufficient to pose a problem for Indigenous critics. As a consequence, Falk’s approach to ecocide is axiologically problematic because its language falls short of the ontological, epistemological, and methodological expectations of Indigenous perspectives.

Similar to Falk, Gray’s articulation of ecocide poses broad problems.Footnote 113 Ontologically, Gray’s version views ecological damage on the basis of violations of rights and an absence of benefits to society, effectively presenting an anthropocentric orientation to identify cases of ecocide. As a consequence, Gray differs from Indigenous approaches that consider harm to humans and the environment as equally interconnected. Epistemologically, Gray’s approach also poses issues because an anthropocentric framing limits considerations of types of environmental harm to those with an impact on humans, deviating from Indigenous proclivities for relational approaches that follow broader reflections of humans and nature in exploring human–environment relations. Further, Gray’s reference to rights exposes ecocide to corollary struggles over the content of rights in law, where protection is dependent upon the articulation of rights expressed in the text of legal instruments. Particular examples are the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)Footnote 114 and the 1989 International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 169 concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries (ILO 169),Footnote 115 which provide a comprehensive array of Indigenous rights covering a variety of political, legal, economic, spiritual, and socio-cultural issues, but which are still contested by Indigenous critics. For example, with respect to UNDRIP, scholars such as Megan Davis,Footnote 116 Stephanie Green,Footnote 117 Fiona MacDonald and Ben Wood,Footnote 118 Aileen Moreton-Robinson,Footnote 119 and Charmaine White Face (also known as Zumila Wobaga)Footnote 120 see the Declaration as a product of compromises which maintain the hegemony of state sovereignty to inhibit Indigenous ambitions for self-determination. Similarly, with respect to ILO 169, scholars like Les Malezer,Footnote 121 Tracey Whare,Footnote 122 and Athanasios YupsanisFootnote 123 view the Convention as neglecting Indigenous agency, in that it focuses on the duties of states in protecting Indigenous rights, limits access by Indigenous peoples to the treaty’s mechanisms, and fails to affirm an Indigenous right to self-determination. The contestation over rights carries over to methodology, with the failure of ILO 169 to guarantee self-determination accompanied by the delimitation by UNDRIP of Indigenous self-determination to maintain the primacy of state sovereignty set forth by the UN Charter.Footnote 124 Hence, as much as a rights-based approach may assert self-determination, it does not assure an absolute right, and so does not guarantee the exercise of self-determination on behalf of Indigenous ontologies or epistemologies. Collectively, the aforementioned issues describe the axiological challenge posed by Gray’s conception of ecocide for Indigenous peoples.

In contrast to Falk and Gray, the issues with Higgins’ definition are more confined, relating less to ontology and more to epistemology and methodology.Footnote 125 Ontologically, Higgins centres the idea of harm around the diminishment of ‘peaceful enjoyment by the inhabitants’ of an ecosystem, with broad constructions that treat peaceful enjoyment as encompassing ‘peace, health, and cultural integrity’ and inhabitants as referring to ‘indigenous occupants’ consisting of humans, animals, plants, and other living organisms.Footnote 126 Such scope positions human and non-human organisms as equal elements sharing an ecosystem, and so generally fits within Indigenous expectations to avoid human–nature dichotomies in favour of integrated frameworks. With regard to epistemology, there is a measure of space for relationality, in the sense that Higgins’ language addresses questions of human agency in driving environmental destruction and conversely questions of environmental destruction harming human welfare. However, it is not clear if there is comparable space to accommodate the comprehensive scope of human–nature relations in Indigenous understanding. Doing so requires an interpretation of ‘peaceful enjoyment’ and ‘peace, health, and cultural integrity’ as encompassing the diverse political, legal, economic, spiritual, and socio-cultural connections between Indigenous peoples with the environment. Comparable difficulty also applies for methodology, with the terminology of ‘peace, health, and cultural integrity’ needing interpretation to include Indigenous self-determination. Such ambiguities open space for argument in meaning, and similar to the concerns with Falk, the potential for argument raises axiological concerns for Indigenous approaches.

Finally, the issues in the formulation of ecocide by the Independent Expert Panel echo Higgins’ difficulties in terms of centring more around epistemology and methodology than ontology.Footnote 127 With regard to ontology, the IEP language phrases ecocide as ‘severe’ and ‘widespread or long-term’ damage to the environment, indicating a more ecocentric disposition that directs attention to harm to the natural world. There is, however, an inclusion of human interests, with the IEP defining ‘severe’ to encompass ‘grave impacts on human life or natural, cultural, or economic resources’.Footnote 128 The result is a definition that includes both human and environmental considerations, and in that respect offers a measure of conformity with Indigenous perspectives. The IEP definition, however, leaves an epistemological issue with respect to the treatment of human–environment relations. Specifically, the IEP language describes grave impacts in terms of human life or resources for human use, which may echo the relational character between humans and the environment in Indigenous understanding, but curtails the comprehensive scope of human–nature interactions in Indigenous approaches. In particular, it is not clear if the IEP text encompasses the full range of political, legal, economic, spiritual, and socio-cultural connections contained in Indigenous perspectives. IEP commentary stresses that the inclusion of ‘cultural’ resources in its definition is intended to assert explicitly ‘the cultural value of elements of the environment, particularly to Indigenous peoples’.Footnote 129 It may be possible to interpret such language as including other components of Indigenous conceptions of human–nature relations, but to do so requires an inference regarding the IEP wording, reopening the possibility of contestation in meaning. As a result, the IEP raises epistemological concerns for Indigenous perspectives. Similar difficulties arise with respect to methodology, in that construction of Indigenous self-determination from the IEP language also requires inference. In a sense, it may be possible to read the IEP commentary as implying self-determination, in that degradation of ‘human life or natural, cultural, or economic resources’ brings a loss of ability to exercise self-determination over those elements. However, the ambiguities that incur such inference leave the IEP definition problematic for Indigenous critics. Hence, the complications of epistemology and methodology prevent the IEP approach from meeting the axiological requirements of Indigenous expectations.

4.2. Indigenous Critique regarding the Inclusion of Ecocide as an International Crime

Beyond considerations over definitions of ecocide, the analytical framework for Indigenous approaches also serves to clarify the particular points of critique against efforts to include ecocide in international criminal law. Similar to the discussion above, the organization into ontology, epistemology, and methodology helps to discern nuances in Indigenous concerns. In so doing, it facilitates an axiological assessment about the appropriateness of international criminal law in prosecuting ecocide for Indigenous peoples.

Beginning with ontology, international criminal law raises concerns for Indigenous approaches with respect to its orientation on criminal justice. In pursuing perpetrators, international criminal law looks to individual culpability, with prosecution revolving around the identification of specific persons committing acts deemed to be crimes under international law. Such a disposition risks decontextualization in the sense that its focus on individuals turns attention away from potential political and social processes that drive criminal conduct.Footnote 130 In contrast, Indigenous conceptions of criminal justice frequently include considerations of wider political and social contexts, going beyond deliberations over perpetrators and victims to consider the welfare of their associated communities.Footnote 131

Additional issues arise in relation to epistemology, with international criminal law differing from Indigenous approaches in both the form of analysis and the motives for universalism. With respect to analysis, international criminal law employs reasoning that focuses on identifying a transgression of a legal norm by an individual, determining the intent of the perpetrator in mens rea and the accompanying conduct in actus reus, and evaluating the sufficiency of evidence to convict a defendant for violation of the specified legal norm.Footnote 132 In addition, in cases of conviction, the concern is for issuing sentences that are proportional to the transgression, with the permutations involving punishment upon the convicted perpetrator or restitution to the victim.Footnote 133 Indigenous studies literature, however, asserts that Indigenous systems of criminal law direct attention beyond violation of a legal norm to consider the status of the parties resulting from an action, and explore justice not just in terms of the individual criminal responsible for the action but, more broadly, in terms of a collective encompassing the perpetrator, the victim, and their associated communities.Footnote 134 In doing so, Indigenous approaches decentre concerns for mens rea, actus reus, evidentiary standards, or sentencing based on punishment or restitution, with the focus instead on the pursuit of more therapeutic and restorative forms of justice for affected parties and their respective communities.Footnote 135

In respect of universalism, international criminal law works to promote a global system for prosecuting a slate of internationally recognized crimes.Footnote 136 Goals for universal criminal justice, however, ignore the potential diversity of Indigenous peoples, in that various Indigenous communities may hold distinct conceptualizations of criminal law.Footnote 137 That is, for a given Indigenous group, the continuation of its justice system can be a part of group survival to the extent that sensibilities of law are a component of group identity. As a consequence, to the extent that criminal justice is a part of any Indigenous group’s sense of self, the universal ambitions of international criminal law present a threat to the preservation of their distinct identity. Indigenous interests call for some assurance of diversity, challenging international criminal law to discern the continued existence of Indigenous populations as unique peoples distinct from each other.

The issues of universalism extend to methodology, in that the efforts of international criminal law also threaten the aspirations for Indigenous self-determination and evoke legacies of colonialism in international law. To the extent that Indigenous law contributes to Indigenous identity, it becomes a part of Indigenous efforts to preserve identity through projects of Indigenous self-determination.Footnote 138 The concept of an international system for criminal law carries a premise of an overarching global system outside the various forms of criminal justice held by diverse legal orders in the world, including the legal orders of Indigenous communities. However, a global system risks inhibiting self-determination, to the degree that it involves a structure prescribing a uniform body of norms, rules, and practices that override the efforts of different Indigenous peoples to exercise their own unique legal systems.

Such tensions between universality and self-determination gain additional significance when viewed in the light of the colonial legacies of international law. In particular, critical Indigenous studies literature points to the origin of the modern international legal system in the historical global expansion of Western imperial powers.Footnote 139 For Indigenous critics, Western empires used the law as an instrument to subjugate Indigenous peoples, with criminal law being a component of colonial administrations working to suppress Indigenous resistance and erase Indigenous societies.Footnote 140 Such activities were compounded by the contributions of international law in promoting anthropocentric political orders tied to extractive economic systems that drove environmental consumption.Footnote 141 As a result, efforts to promote international criminal law evoke histories of colonial domination against Indigenous peoples and imperial destruction of host environments. The resulting implication is that the ambitions for international criminal law connect ecocide to Indigenous anxieties over the role of international law in colonization, and hence render those ambitions problematic for Indigenous interests.Footnote 142 For Indigenous peoples, self-determination is significant in mitigating the legacies of international law, particularly with respect to the placement of authority in Indigenous peoples to negotiate the intersections of their own laws with the laws of a world centred on states.Footnote 143

5. Future Directions for Indigenous Prescriptions

The preceding sections provided a descriptive discussion, presenting a framework of Indigenous theory that facilitates discernment of various aspects of Indigenous concerns over ecocide discourse. The framework of ontology, epistemology, methodology, and axiology serves a heuristic function in terms of clarifying details of Indigenous critiques regarding efforts to define ecocide and attendant movements to incorporate ecocide into international criminal law. In doing so, the ontological, epistemological, and methodological elements drawn from Indigenous studies literature provide a means for axiological assessment, in the sense that they represent Indigenous expectations which function as normative parameters demarcating the components of ecocide discourse that are appropriate or inappropriate for Indigenous peoples. In essence, to the extent that arguments or activities related to ecocide infringe upon Indigenous ontology, epistemology, or methodology, they constitute challenges for Indigenous axiology.

Such descriptive insights invite prescriptive reflection on potential responses that address Indigenous issues regarding ecocide. In particular, they call for future studies to identify prescriptions that satisfy Indigenous normative expectations. However, such efforts go beyond pedantic enumeration of actions to address ontology, epistemology, methodology, or axiology, in that ambitions for prescriptive insights must contend with a potential complexity of Indigenous perspectives arising from diverse Indigenous populations holding different concerns. In effect, each Indigenous community will have its own sensibilities on ecocide, and thus its own normative issues with ecocide discourse. The global breadth of Indigenous peoples risks an expansive scope of diverse expectations yielding a correspondingly wide array of resulting prescriptions. As a result, in keeping with heuristic goals of previous sections to clarify descriptive understanding of Indigenous perspectives, there is also a need for Indigenous theory to provide additional guidance for future studies regarding prescriptions responsive to the breadth of Indigenous concerns.

Indigenous studies literature provides potential guidance supplementing the analysis of previous sections, with particular Indigenous scholarship on international law offering parameters for prescriptive studies covering the broad variety of Indigenous perspectives regarding ecocide. While it may be daunting to attempt a comprehensive review of Indigenous cases covering all the potential nuances associated with the specific contexts of each individual Indigenous community, it is possible to clarify directions for future studies by identifying the scope of potential Indigenous prescriptions that may arise from the diversity of Indigenous peoples. Specifically, the literature identified as Fourth World Approaches to International Law (FWAIL) – sometimes ascribed with the term Original Nations Approaches to International Law (ONAIL) – offers a means for identifying relevant areas for further prescriptive studies.

In brief, FWAIL directs attention to the presence of Indigenous peoples in international law, with the terms ‘Fourth World’ or ‘Original Nations’ being used to represent the assembly of Indigenous peoples in the world.Footnote 144 FWAIL is distinguished from other critical literature known as Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) in that FWAIL critiques TWAIL as adhering to state-centric and materialist conceptions of international law, whereas FWAIL seeks to extend attention past states to address the concerns of Indigenous peoples.Footnote 145 In particular, FWAIL sees Indigenous political and legal orders as pre-dating the rise of an international legal system comprising nation-states and asserts that those orders continue to exist in the current era of state-centric international law.Footnote 146 Generally, FWAIL argues for greater awareness of Indigenous groups as distinct political and legal entities in the international legal system, criticizes the primacy of the state as a dominant unit of legal personality in international law, and calls for the decolonization of international law’s hegemonic structures that continue to subjugate Indigenous peoples.Footnote 147

FWAIL asserts Indigenous agency within the structure of international law and, in doing so, presents a range of prescriptive arguments regarding Indigenous activism. FWAIL organizes the various perspectives relative to each other along a continuum extending between ‘thin’ and ‘thick’ extremes. ‘Thin’ reflects arguments that look towards continuation of the existing international legal system, such that they seek to improve the status of Indigenous peoples through the exercise of the rules, procedures, and institutions of the prevailing international legal order.Footnote 148 In effect, their expectations trend more towards reforms rather than revolution. ‘Thick’, in contrast, relates to arguments that pursue comprehensive change and, in doing so, reject existing international law and advance an alternative vision that removes the state as the dominant legal actor in the international legal system.Footnote 149 For thick perspectives, the promotion of Indigenous peoples requires a departure from the status quo, and so goes beyond reform towards total transformation. The distinction between thin and thick approaches assists in distinguishing potential Indigenous prescriptions for ecocide discourse, both with respect to the deliberations over the definition of ecocide and the efforts to incorporate ecocide into international criminal law. The following subsections address how the differentiation between thin and thick extremes can function as parameters for prescriptive studies.

5.1. Indigenous Prescriptions regarding the Meaning of Ecocide

Applied to the discourse over the definition of ecocide, the appellation of ‘thin’ would apply to calls that operate to maintain the parameters of discourse reflected by various proposals, either in terms of their articulation of wording for ecocide or in terms of the processes responsible for producing them. With respect to existing wording, thin perspectives would avoid displacement of the language expressed by Falk, Gray, Higgins or the IEP, favouring instead modification or interpretation of their respective wordings to address Indigenous interests in the environment. With respect to processes, thin approaches provide a possibility for reforms in definition, in the sense that the goals would be for the inclusion of Indigenous voices as participants within existing activities to refine the language in each of the various definitions. Phrased in the analytical framework of previous sections: thin perspectives would address Indigenous axiological concerns by working within the existing parameters of discourse to direct conceptions of ecocide towards closer alignment with Indigenous norms. In essence, in advancing Indigenous expectations, the preference of thin approaches would be to engage ecocide discourse over its ontological offering of definitions, its epistemological treatment of Indigenous relationality with the environment, and its methodological accommodation of Indigenous self-determination in deliberations over the meaning of ecocide.

Examples of thin approaches for definitions of ecocide exist in the work of Indigenous organizations with the ICC, UNFCCC, and WEF in 2021, cited at the introduction of the present analysis.Footnote 150 For the ICC, prior to its submission to the Court, the organization Articulação dos Povos Indígenas do Brasil (Articulation of Indigenous Peoples from Brazil, or APIB) made public statements using the term ‘ecocide’ in relation to policies under the Brazilian government of Jair Bolsonaro that weakened forms of legal protection and enabled harm to the environment in Indigenous territories.Footnote 151 In effect, APIB connected its agenda to ecocide using an expansive definition that includes administrative, legislative, and judicial actions against Indigenous peoples. Such ontological action reflected APIB’s epistemological conception of harm as encompassing not just acts of dispossession of lands or the destruction of ecosystems but also the government policies enabling them. In contrast, Indigenous activists at the 26th Conference of the Parties for the UNFCCC linked femicide to ecocide, highlighting the disproportionate violence directed to Indigenous women in cases of land rights violations.Footnote 152 Their epistemic framing was in terms of gendered impacts of environmental destruction, with an ontological goal of opening ecocide meanings to include gender violence. An additional example is the presence of Indigenous representatives at the WEF, with the particular commentary by Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim adopting ecocide as a vehicle to protect Indigenous lands while concurrently asserting a need to widen the meaning of ecocide to include rights of nature.Footnote 153 Such an argument indicates motives for addition rather than revision, with an acceptance of the existing ontology of ecocide being supplemented by further elements addressing Indigenous epistemes.

In contrast to thin approaches, thick approaches would disapprove of the current conduct of discourse, with regard to both wording and the processes that produce them. Ontologically, thick perspectives would reject the current articulations of ecocide, and would instead pursue either a wholly Indigenous envisioning of ecocide or would abandon the project altogether. Epistemologically, thick arguments would emphasize Indigenous relationality, such that they would seek to remove discourses tied to dichotomies and replace them with deliberations employing Indigenous understandings of human–nature relations. Methodologically, thick approaches would advance self-determination as critical for Indigenous survival, such that they would either seek an articulation of ecocide that includes self-determination or avoid engagement with discourses that fail to include it. Thick approaches appear in arguments of scholars such as Irene Watson, who, in observing legal discourses on genocide and ecocide against Indigenous peoples, directs attention to the underlying power imbalances that privilege state sovereignty over Indigenous welfare. Watson asserts that Indigenous survival requires a balancing of power, such that it centres ontology on Indigenous ways of living and fosters a horizontal dialogue between colonial interests and Indigenous epistemologies as equals.Footnote 154 Watson’s prescription accepts the continued survival of the state, but it calls for a structural transformation that adjusts the hegemonic status of the state to re-empower Indigenous authority. The resulting implication is that deliberations regarding definitions of ecocide are not enough, and that full resolution of Indigenous concerns require more extensive systemic change in the relations between states and Indigenous peoples.

5.2. Indigenous Prescriptions regarding Ecocide within International Criminal Law

In connection with the efforts to make ecocide an international crime, the labels ‘thin’ and ‘thick’ work similarly to their application to definitions of ecocide in terms of indicating the character of Indigenous engagement with the status quo system. In particular, thin perspectives maintain the existing structure of international criminal law, looking to have Indigenous peoples work through the identified crimes, related procedures, and adjudicating institutions that comprise criminal justice in international law. In essence, thin approaches involve Indigenous peoples making instrumental use of international law on behalf of Indigenous agendas.Footnote 155

In keeping with such expectations, thin approaches would feature Indigenous actors aligning themselves with the ontology of justice in international criminal law through a reconceptualization of their concerns within the principles of international criminal justice. Likewise, in relation to epistemology, thin approaches would call upon Indigenous actors to adopt approaches in reasoning exercised by international criminal law, especially in the attention placed upon mens rea, actus reus, and sentencing for an individual accused perpetrator. For methodology, thin perspectives would assert that it is possible for Indigenous peoples to maintain their self-determination through the forms of rights protection currently available in international criminal law.

To a degree, the APIB submission to the ICC provides an example of a thin approach, in the sense that it reflects a willingness by Indigenous activists to engage with an institution of international criminal law. Such an engagement indicates an axiological acceptance of the ICC as being an appropriate means to address APIB concerns over environmental destruction on Indigenous lands. Engagement with the ICC, however, entails the presentation of Indigenous concerns within the framework of the ICC, particularly with respect to the epistemology of the ICC in terms of its vernacular and conceptualization of investigations and prosecutions, as well as its methodology in terms of its procedures for managing cases.Footnote 156 Such limitations are apparent in the APIB submission to the ICC, which omitted the term ‘ecocide’ to fit within the limits of the ICC list of recognized crimes.Footnote 157 Hence, APIB represents a thin approach in engaging international criminal law, which modified Indigenous agendas for the purpose of making instrumental use of international law.

Thick approaches, in contrast, would see the prevailing system of international criminal law itself as being problematic. Ontologically, they would focus on the differences in notions of criminal justice held by Indigenous peoples against the existing system of international criminal law, with the priority being fulfilment for the former over the latter. Epistemologically, thick perspectives would refuse to accept rationales based on mens rea, actus reus, or sentencing of an individual defendant, and instead would pursue greater accommodation of Indigenous interests in restorative and therapeutic justice for the community alongside the perpetrator and victim. In terms of methodology, thick perspectives would view the existing forms of protection for self-determination as inadequate, and would either call for reforms that guarantee protection of self-determination in international criminal law or reject the universalist project of international criminal law entirely. The implications for thick arguments would be a supplanting of existing international criminal law with Indigenous criminal law, or at minimum a transformation of international criminal law so that it applied Indigenous approaches to criminal justice.

Thick approaches appear in critical literature that asserts the existence of Indigenous forms of criminal justice. In particular scholars such as Beverly Jacobs,Footnote 158 Valmaine Toki,Footnote 159 Chris Cuneen,Footnote 160 and Juan TauriFootnote 161 present cases detailing Indigenous conceptions of crime and Indigenous systems of criminal law. With regard to international criminal law, efforts for a Nations International Criminal Tribunal (NICT),Footnote 162 and reflections by scholars such as Terry Beitzel and Tammy Castle,Footnote 163 consider the possibilities for Indigenous alternatives to mechanisms such as the ICC. The more extreme positions charge criminal law as a construct of imperial hegemony, with the history of criminal law at international and domestic levels demonstrating it to be an instrument of colonial powers for the subjugation of Indigenous societies.Footnote 164 For such arguments, there are few prospects to redeem prevailing systems of criminal law, and Indigenous peoples are better served in asserting their own forms of justice entirely.

6. Conclusion

The preceding sections explored the bases for Indigenous normative concerns towards ecocide discourse, both in terms of its meaning and its inclusion in international criminal law. The discussion did so by following Indigenous studies literature regarding the components of Indigenous approaches to understanding existence, framing Indigenous critiques as axiological considerations over issues of ontology, epistemology, and methodology surrounding ecocide. The analysis applied the framework to assist descriptive understanding of the nuances in Indigenous perspectives towards ecocide, clarifying the various ways in which ecocide discourse can be problematic for Indigenous peoples. The discussion proceeded to offer prescriptive reflections, referencing Indigenous studies literature again to draw supplementary guidelines that can help future studies in identifying actions that align with Indigenous concerns. Collectively, the previous sections contribute to existing literature on ecocide by detailing an analytical framework for clarifying Indigenous approaches to ecocide that functions to organize the array of existing Indigenous critiques into a coherent framework that reflects Indigenous norms.

Caution should be noted that individually, each Indigenous community is not a static but a rather dynamic entity that exists concurrently with the existence of states.Footnote 165 As a consequence, considerations for any given Indigenous group should be treated as open to change. The work of preceding sections, however, remains relevant, in that the components of the framework function to clarify the parameters of Indigenous perspectives by delimiting the space of arguments that encompass diverse Indigenous concerns. Further, they provide a framework for analysis that can be applied over time to follow changes in Indigenous discourses and maintain understanding of evolving Indigenous sensibilities.

Additional circumspection should also be dedicated to the parameters of Indigeneity and ecocide. The work of previous sections confined attention to a narrow scope, with analysis focused on the development of a framework clarifying Indigenous approaches to ecocide within discourses of international criminal law. Indigeneity and ecocide, however, are not closed concepts in the sense that discussions over the meanings of both extend beyond the scope of international criminal law. The analysis dealt more with the former rather than the latter. With respect to Indigeneity, the analysis operated with a purpose of facilitating engagement with Indigenous approaches and, on that basis, pursued an orientation that enabled consideration of any source that self-identified as Indigenous. Hence, the analysis provided capacity to converse with diverse conceptions of Indigeneity. In contrast, in relation to ecocide, the delimitation of scope to discourses in international criminal law meant that the analysis did not address the potential of alternative definitions for ecocide that exist outside international criminal law. As a consequence, there is a need for future studies that extend the work of previous sections to broader discourses encompassing other fields, such that the analysis can be refined by the insights on ecocide offered by discussions occurring outside international criminal law.

Returning to the efforts of Indigenous activists raised at the opening of this article, the work in preceding sections serves to temper perceptions of their operations. As much as their actions demonstrate an engagement with international discourses regarding ecocide, they do not necessarily represent an acceptance of existing conceptions in its meaning or current agendas to criminalize it in international law. Rather, the discussion in previous sections highlights Indigenous distinctiveness, with agency to articulate Indigenous perspectives that differ from prevailing arguments over ecocide. The nuances in perspectives make Indigenous approaches rich, with complexities that open alternative considerations in ecocide discourse. Therefore, as much as engagement in international venues may be construed as a tacit acknowledgement of ecocide, they may also be seen as an exercise of Indigenous agency to engage ecocide discourse in service of Indigenous agendas. In keeping with such observations, the larger import of the preceding sections is that greater understanding of the details in Indigenous perspectives will ensure more inclusion of Indigenous voices and more clarity in deliberations to address their concerns.

Acknowledgements

The author is a member of the Pa’Oh Indigenous peoples of Shan State, Myanmar. The author extends acknowledgements to the Cambridge University Lauterpacht Centre for International Law, the Oxford University Bonavero Institute of Human Rights, and the Harvard Law School Human Rights Program, all of which hosted the work embodied in this article. The author also thanks the TEL reviewers for their constructive comments and attention.

Funding statement

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares none.