I. Introduction

In recent years, the literature on international economics has broadened its scope by incorporating firm-level heterogeneity into international trade models (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Jensen, Redding and Schott2012; Chaney, Reference Chaney2008; Melitz, Reference Melitz2003; among others). The possibility of using microdata relating to firms in the internationalization process has led to a new theoretical approach based on firm heterogeneity that challenges and refines traditional trade models (Eaton and Kortum, Reference Eaton and Kortum2012).

This study employs a version of the gravity equation that integrates firm-level heterogeneity. The fundamental insight of the gravity equation is that the trade between two countries primarily depends on the size of their respective markets, which can be interpreted as the exporter’s supply capacity and the importer's demand capacity. However, these trade flows are also subject to a variety of frictions, referred to broadly as trade costs, which vary across destinations. These include geographical, political, economic and cultural distances, and other barriers that inhibit export opportunities.

In the context of international wine trade, many studies have applied this gravity equation from a macroeconomic perspective (Ayuda et al., Reference Ayuda, Ferrer-Pérez and Pinilla2020a, Reference Ayuda, Ferrer-Pérez and Pinilla2020b; Bargain et al., Reference Bargain, Cardebat and Chiappini2022; Castillo et al., Reference Castillo, Villanueva and García-Cortijo2016; Dal Bianco et al., Reference Dal Bianco, Boatto, Caracciolo and Santeramo2016; Dascal et al., Reference Dascal, Mattas and Tzouvelekas2002; Macedo et al., Reference Macedo, Gouveia and Rebelo2020; Pinilla and Serrano, Reference Pinilla and Serrano2008; Puga et al., Reference Puga, Sharafeyeva and Anderson2022). While this approach has generated valuable insights into the dynamics of international trade flows, it often overlooks firm-specific characteristics and strategies, focusing exclusively on external variables. Yet the actions and attributes of firms are critical in explaining a country's export performance (Corsi et al., Reference Corsi, Mazzarino and Blanc2025). Wineries are the primary economic agents operating in markets, and as such, integrating the micro-level dimension into trade models is essential. Trade outcomes are shaped not only by external factors but also by firms’ strategic decisions (Alonso-Ugaglia et al., Reference Alonso-Ugaglia, Cardebat and Corsi2019; Ferrer et al., Reference Ferrer, Serrano, Abella-Garcés, Pinilla and Maza2022).

This study is framed within this perspective, aiming to account for firm-level decision-making in explaining variations in export flows. Internationalization represents a significant challenge for most wineries, particularly for those lacking sufficient resources and knowledge of foreign markets (Johanson and Mattsson, Reference Johanson and Mattsson2015). A winery's ability to understand consumption patterns in target markets-and to adapt its products accordingly-is a key determinant of export success (Helm and Gritsch, Reference Helm and Gritsch2014; Wood and Robertson, Reference Wood and Robertson2000). The greater the alignment between offerings and the preferences of distributors, intermediaries, and consumers in each country, the more favorable the export opportunities (Gangurde and Akarte, Reference Gangurde and Akarte2013; Vanegas-López et al., Reference Vanegas-López, Baena-Rojas, López-Cadavid and Mathew2020).

Specifically, this study investigates whether product–market fit in the destination country (i.e., the adjustment of wine attributes to local market preferences) positively affects both the probability of exporting to those markets and the intensity of such exports. Furthermore, it examines whether a high degree of product adjustment reduces cross-market costs, more precisely, whether it moderates the effect of the distance between markets.

To address these research questions, we have selected a highly suitable case study, the wine industry. This is an ideal sector for this analysis due to its high level of internationalization. Approximately 70% of global wine production has been traded internationally for the past two decades (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Nelgen and Pinilla2017; Anderson and Pinilla, Reference Anderson and Pinilla2022). Specifically, we use a representative sample of Spanish wineries. The choice of Spain is particularly relevant, as it is one of the world’s leading wine exporters, selling a substantial portion of its production abroad (Fernández and Pinilla, Reference Fernández, Pinilla, Anderson and Pinilla2018).

Our analysis considers two main dimensions: (1) internal firm characteristics—namely, resources and capabilities—and (2) the extent to which firm strategies are adapted to the characteristics of destination markets. This adaptation is critical because greater market distance entails higher transaction costs, especially for smaller firms, which characterize much of the Spanish wine industry. Notably, in 2021, Spanish wineries exported 23.6 million hectoliters out of a total production of 35 million, representing approximately 67% of total output (OIV, 2022). Internationalization and market selection have thus become major challenges for Spanish wineries, particularly smaller ones, which increasingly seek markets better matched to their product profiles.

To conduct our empirical analysis, we apply a gravity model that incorporates firm-level heterogeneity in order to examine the factors influencing both the probability and intensity of exports, following the approach of Roberts and Tybout (Reference Roberts and Tybout1997). Specifically, the study analyzes the effect of product-market adjustment on both the propensity and intensity of exports across a diverse range of international destinations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on product–market adjustment and formulates the hypotheses to be tested. Section 3 outlines the econometric strategy and describes the data sources. Section 4 presents and discusses the results, and Section 5 concludes with a summary of the main findings.

II. Theoretical background and hypotheses

When a firm seeks to expand internationally, one of the first and most critical decisions it must make concerns the choice of entry mode. This decision is often irreversible and is influenced by a wide range of factors (Rienda et al., Reference Rienda, Quer and Andreu2021). While firms acknowledge that internationalization involves certain risks, it also offers significant opportunities. Prior research suggests that firms typically pursue international expansion when they identify an advantage that can be effectively leveraged in foreign markets (Martins Antunes et al., Reference Martins Antunes, Gouveia Barandas and Martins2019).

A fundamental challenge in this process is acquiring relevant and strategic information about potential target markets and selecting those that offer the greatest opportunities. Scholars have distinguished between macroeconomic factors-such as country-level characteristics and the distance across markets, and microeconomic factors, which encompass human-related dimensions (Papadopoulos and Martin Martin, Reference Papadopoulos and Martin Martin2011; Sousa and Lages, Reference Sousa and Lages2010). These so-called “distances” refer to “the differences that exist between and within countries, regions, and societies” (Martins Antunes et al., Reference Martins Antunes, Gouveia Barandas and Martins2019, p. 347).

Among the microeconomic factors, product adaptation-namely, the alignment of a firm's marketing mix with the preferences of the target market-is particularly important (Sousa and Lages, Reference Sousa and Lages2010). According to the Nordic School of International Business, market selection is shaped by two key, interrelated concepts: distance and learning-by-doing (Fina and Rugman, Reference Fina and Rugman1996; Johanson and Vahlne, Reference Johanson and Vahlne1977; Kogut and Singh, Reference Kogut and Singh1988). When there is a substantial distance between markets, firms often cannot rely on standardized products to ensure successful entry. The distance between markets may cause consumers to perceive the product differently, potentially leading to failure.

In such cases, firms are advised to adopt a strategy focused on adapting their marketing mix. However, this approach entails a loss of economies of scale and may not be feasible for all firms, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Akgün et al., Reference Akgün, Keskin and Ayar2014; Baena-Rojas et al., Reference Baena-Rojas, Vanegas-López and López-Cadavid2021; Helm and Gritsch, Reference Helm and Gritsch2014). This challenge is especially pronounced in the wine industry, which is predominantly composed of small-scale wineries. In this context, and with the aim of maximizing standardization in their marketing strategies, including product, pricing, distribution, and promotion, firms tend to prioritize markets characterized by lower distances (Akgün et al., Reference Akgün, Keskin and Ayar2014; Erdil and Özdemir, Reference Erdil and Özdemir2016; Helm and Gritsch, Reference Helm and Gritsch2014).

In summary, among the range of potential international markets, firms are more likely to select those where their product and marketing strategy can be most effectively adapted to local tastes, consumer behavior, and cultural norms (Deaza et al., Reference Deaza, Díaz, Castiblanco and Barbosa2020; Helm and Gritsch, Reference Helm and Gritsch2014).

In international trade, transaction costs are fundamental to explaining the direction and intensity of goods flows. Macroeconomic models often use physical distance as a proxy for transportation costs between countries of origin and destination, making it a decisive and recurring factor in explaining bilateral trade flows. In the international business literature, market distance implies that firms must acquire knowledge about the countries they intend to enter. Differences across markets, whether cultural, economic, legal, or geographical, shape how managers perceive foreign markets and, consequently, influence their strategic decisions. These various types of distance determine how customers in foreign markets perceive a product, which in turn affects the strategic choices made by managers (Fonfara et al., Reference Fonfara, Hauke-Lopes and Soniewicki2021; Johanson and Wiedersheim, Reference Johanson and Wiedersheim1975; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Deligonul, Cavusgil and Chiou2021).

Several authors have developed frameworks for measuring the distance between countries (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Guillén and Zhou2010; Dow and Karunaratna, Reference Dow and Karunaratna2006; Ghemawat, Reference Ghemawat2001; Martín Martín and Drogendijk, Reference Martín Martín and Drogendijk2014). Among these, the framework proposed by Ghemawat—known as the CAGE (cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic differences between countries) framework—is the most widely used and is adopted in this study (Moalla and Mayrhofer, Reference Moalla and Mayrhofer2020). The CAGE framework examines distance between countries along four dimensions: cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic (Ghemawat, Reference Ghemawat2001).

According to Ghemawat (Reference Ghemawat2001), geographic distance refers to the “physical remoteness between countries, the physical size of the country, the lack of a common border and sea access, and differences in climate, transportation, and communication.” Administrative or political distance refers to “differences in colonial ties, monetary and political associations, government policies, [and] institutional weaknesses.” Economic distance refers to “differences in consumer incomes and in costs and quality of natural and human resources, infrastructure, intermediate inputs, and knowledge” (Moalla and Mayrhofer, Reference Moalla and Mayrhofer2020, p. 7). Finally, based on Geert Hofstede's framework, we use four cultural distance dimensions: uncertainty avoidance, power distance, individualism, and masculinity. Originally introduced in his 1980 book Culture’s Consequences, this framework remains the most widely used measure in the international business literature.

Silva and Santos (Reference Silva and Santos2020), in a study examining Portuguese wine producers, offer a comprehensive analysis of the principal marketing mix elements relevant to the wine industry. These elements include alcohol level, awards, brand image, color, consumption context, Protected Denomination of Origin PDO certification, harvest, label information, label design, packaging, price, product positioning, promotion, quality, recommendations, reputation, bottle closure, wine ingredients, and region of origin. Their findings indicate that the most highly valued attributes among producers are quality, reputation, brand image, and price. In contrast, wine ingredients and alcohol content were perceived as the least important. The study also reveals that consumers who experience difficulty selecting a suitable wine tend to place greater emphasis on reputation and brand. Furthermore, the authors identify three overarching factors that encapsulate these marketing mix elements: (1) intrinsic attributes, related to wine processing, manufacturing, and production (including alcohol content, color, certification and region of origin, quality, harvest year, and bottle closure); (2) market-related factors, encompassing price, positioning, promotion, and the opinion of key influencers; and (3) extrinsic attributes, such as brand image, packaging, and labeling. The degree to which producers emphasize each of these attribute groups facilitates differentiation within the market and contributes to achieving competitive advantage.

Hence, firms-wineries in this case-must carefully analyze their product and positioning strategies when selecting export markets (Erdil and Özdemir, Reference Erdil and Özdemir2016; Gorecka and Szalucka, Reference Gorecka and Szalucka2013). A firm may choose to adapt its marketing mix to better align with the preferences of the target market. However, such a process of de-standardization can complicate the achievement of economies of scale, thereby increasing operations costs (Helm and Gritsch, Reference Helm and Gritsch2014; Sousa and Lages, Reference Sousa and Lages2010). Conversely, a product standardization strategy can help mitigate the impact of cross-national distance in the internationalization process. The negative effects of the distance may be moderated if the firm targets markets that align closely with the characteristic of its product (i.e., product-market adjustment).

The analytical framework that facilitates the integration of both macroeconomic and microeconomic variables including firm-level heterogeneity to explain export performance is provided by gravity models of trade. Several studies have employed the gravity equation to incorporate heterogeneity into their analyzes (e.g., Corsi et al., Reference Corsi, Mazzarino and Blanc2025; Serrano et al., Reference Serrano, Acero and Fernández-Olmos2016). Originally proposed by Anderson (Reference Anderson1979), the gravity equation posits that trade flows are positively related to the economic size of countries and negatively related to the distance between them. Economic size can be measured in various ways; in this article, we use the volume of sales in the foreign market as a proxy.

Gravity models are currently among the most widely used tools for explaining the determinants of international trade. While traditional gravity models often focus solely on macroeconomic variables, extensions that account for firm-level heterogeneity have become increasingly relevant. These models posit that trade flows between two countries are directly related to the size of their economies and inversely related to transaction costs or trade frictions. The market potential of the export destination is one of the most important factors influencing a country's attractiveness and, thus, market selection. It serves as a key driver of firms’ expansion into foreign markets (Yoshida, Reference Yoshida1987). While physical distance is frequently used, our approach considers four distinct dimensions of distance: economic, geographical, political, and cultural.

However, distance alone does not fully capture the ease or difficulty of entering a given market. Two firms from the same home country and operating within the same sector may experience different levels of success when exporting to the same foreign market. Not all firms within a sector face the same opportunities; outcomes depend on the specific characteristics of the firm and its products (Wood and Robertson, Reference Wood and Robertson2000). What may distinguish export performance are macroeconomic factors (Deaza et al., Reference Deaza, Díaz, Castiblanco and Barbosa2020), particularly the extent to which the product and its marketing mix are adapted to the characteristics of the target market (Deaza et al., Reference Deaza, Díaz, Castiblanco and Barbosa2020; Robertson and Wood, Reference Robertson and Wood2000).

Hypotheses

Within the theoretical framework described, the concept of product–market adjustment explains how wineries adapt their offerings—leveraging marketing experience and positioning—to enter foreign markets. Wineries tend to favor entry into markets that are highly attractive for their products, entail low market risk, and offer potential for competitive advantage.

Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1. The probability of exporting to a market increases when there is a strong alignment between the product and the target market.

H2. The intensity of exports to a market is positively influenced by the degree of alignment between the product and the target market.

H3. Product–market adjustment moderates the effect of distance on export propensity across markets.

H4. Product–market adjustment moderates the effect of distance on export intensity across markets.

III. Methodology

a. Sample

This study draws on three sources to obtain data on the characteristics of both the destination markets and the exporting firms. For the destination markets, two complementary data sources were used. The first is the Vinitrac Survey, conducted by Wine Intelligence, which collects data from wine consumers in countries worldwide. Through this survey, we obtained information on 21 wine markets to which the Spanish wine industry exports, representing 85% of the total volume exported by Spanish wineries with PDO status.

Second, to broaden the scope of information on destination markets, we conducted a survey of 2,560 importers across different countries, yielding 227 valid responses. This provided data on 49 destination markets, which together account for approximately 90% of the wine exported by Spanish PDO wineries. This second survey was designed to complement the Vinitrac Survey, following a similar structure and methodology, with the objective of identifying the key characteristics of destination markets.

For the exporting wineries, we needed to identify firm characteristics, the reasons why their products are selected, and their competitive strengths. To this end, we surveyed all Spanish PDO wineries (2,540 in total), obtaining 351 valid responses, which represent 14% of the defined population, with a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence level. These figures were determined using the standard error of the mean for finite populations, assuming p = q = 0.5.

In this survey, the questions assessing wineries’ capacity to enter foreign markets mirrored those used by Wine Intelligence to characterize destination markets.

By combining these three data sources, we were able to compare how consumers select wines in importing countries with how wineries design their product positioning strategies at origin.

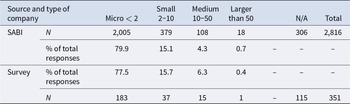

Tables 1 and 2 show the representativeness of the sample relative to the total population.

Table 1. Wineries in Spain by number of employees (Dec 2019) and their percentages, compared to the wineries in the sample

Table 2. Wineries in Spain by size and sample response share (sales in € millions)

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on our survey of Spanish wineries and SABI database (SABI 2022). Figures for December 2019.

The combination of the three data sources allows for a maximum of 19,199 cross-referenced data points, covering 351 exporting wineries and 49 destinations.

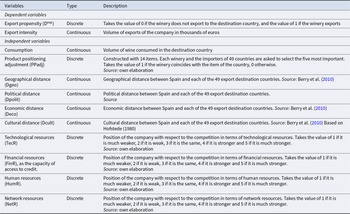

b. Variables

Product–market adjustment is analyzed using the variable “Product–Market Adjustment” (PMaj). This is a multiplicative variable constructed from the same information gathered through the winery survey and destination market data (Vinitrac and the importer survey).

Wineries were asked to rate, on a scale from 1 to 5, the five most important factors they believe influence their customers’ purchase decisions, from a list of 14 items: country of origin of the wine, grape variety, promotional offers, brand recognition, recommendation from a friend or family member, region of origin, bottle and/or label design, awards received, recommendation from store staff, recommendation from a critic or magazine, wine description, alcohol content, food pairing, and price. Meanwhile, consumers and importers in the destination countries assessed the importance of these same 14 items in consumers’ purchasing decisions. The Appendix reports the questions used by Wine Intelligence—which are the same as those included in our survey of importers— as well as the questions addressed to the wineries for the construction of the PMaj variable.

To measure the distance between markets, this study uses the database developed by Berry et al. (Reference Berry, Guillén and Zhou2010), which disaggregates different distance dimensions. Geographical distance (Dgeo) is calculated based on the geographic centroids of the countries analyzed, using data from the Berry et al. (Reference Berry, Guillén and Zhou2010) database, which provides information for all relevant countries. The Dgeo variable was standardized by centering it on its mean and scaling it by its standard deviation. The second variable used to measure the difference between markets is the political distance (Dpolit), for which the differences in the democratic quality of the country are analyzed, together with the size of the state in relation to the economy and the number of international trade agreements signed. The study also uses the economic distance (Deco), which takes into account the differences in economic development and macroeconomic characteristics between the countries of origin and destination. To calculate this, we consider the distance between the two markets in terms of GDP per capita, inflation rate, and trade intensity with the rest of the world. Cultural distance (Dcult) is measured using Geert Hofstede's four cultural dimensions: Power distance (based on questions about obedience and respect for authority); Uncertainty avoidance (questions about trust in people); Individualism (questions on independence and the role of government in providing for citizens), and Masculinity (questions on the importance of family and work). The data are sourced from the database compiled by Berry et al. (Reference Berry, Guillén and Zhou2010).

Four multiplicative variables are also used in the model, obtained from the interaction of the adjustment in product-market (PMaj) with the four distances: geographical, political, economic. and cultural. That is, PMaj × Dgeo, PMaj × Dpolit, PMaj × Deco, and PMaj × Dcult (see Table 4). The variable PMaj × Dgeo was standardized by centering it on its mean and scaling by its standard deviation.

In addition to the variables that characterize the distance and adjustment of the product to the destination market, a series of control variables have been included. Following the traditional version of gravity trade models, the size of the market is controlled. The first variable used is wine consumption (Consumption), which is measured as the total amount consumed and has been obtained from OIV (2022) for the year 2021, in MHl. The variable was standardized by centering it on its mean and scaling by its standard deviation. Moreover, variables related to the characteristics of the companies have also been included, following the literature on heterogeneous companies. The resources and capabilities theory (Barney, Reference Barney1991) postulates that the performance of companies depends on a set of available resources and capabilities developed by the company. On the one hand, tangible resources (Barney, Reference Barney1991) have been studied, analyzing the technological and financial resources. On the other hand, the intangible resources (Barney, Reference Barney1991) are also studied including human and network resources. The importance and expected meaning are explained below.

The technological resources variable (TecR) has been characterized according to the technological position of the company with respect to the competition (Ferrer-Lorenzo et al., Reference Ferrer-Lorenzo, Maza-Rubio and Abella-Garcés2018; Ortega, Reference Ortega2010). The variable of financial resources (FinR) evaluates the ability of a firm to access credit with respect to its competitors (Ferrer-Lorenzo et al., Reference Ferrer-Lorenzo, Maza-Rubio and Abella-Garcés2018; Ortega, Reference Ortega2010).

Furthermore, a second group of variables is included, which seeks to control the access to intangible resources that influence exports (Abella and Salas, Reference Abella and Salas2006). Marketing resources are measured through a variable that evaluates the position of the company with respect to its competitors, and the values are classified on a scale from 1 “much weaker than the competition” to 5 “much stronger than the competition.” The availability of better human resources has been related to the internationalization of the company (Davis and Harrigan, Reference Davis and Harrigan2011). They are measured, as in the previous cases, using a variable (HumR) that contemplates the position of the company with respect to the competition (see Table 3). Finally, there is broad consensus as to the positive relationship between network resources and exports and/or the internationalization of companies, which is especially relevant in the case of the wine industry (Abella et al., Reference Abella, Serrano, Ferrer and Pinilla2025; Corsi et al., Reference Corsi, Mazzarino and Blanc2025; Serrano et al., Reference Serrano, Dejo-Oricain, Ferrer, Pinilla, Abella and Maza2023). Networks mitigate the uncertainties of companies (Phelps et al., Reference Phelps, Heidl and Wadhwa2012; Ferrer et al., Reference Ferrer, Abella-Garcés and Serrano2021), they enable risks to be reduced (Chetty and Blankenburg Holm, Reference Chetty and Blankenburg Holm2000), facilitate access to foreign markets (Coviello, Reference Coviello2006), reduce their costs (Buchwald, Reference Buchwald2014) and enable their products to be adapted to the destination market (Johanson and Mattsson, Reference Johanson and Mattsson2015). Network resources (NetR) is introduced using the evaluation of the available network resources of the companies with respect to the position of the competition (see Table 3).

Table 3. Variables of the empirical model

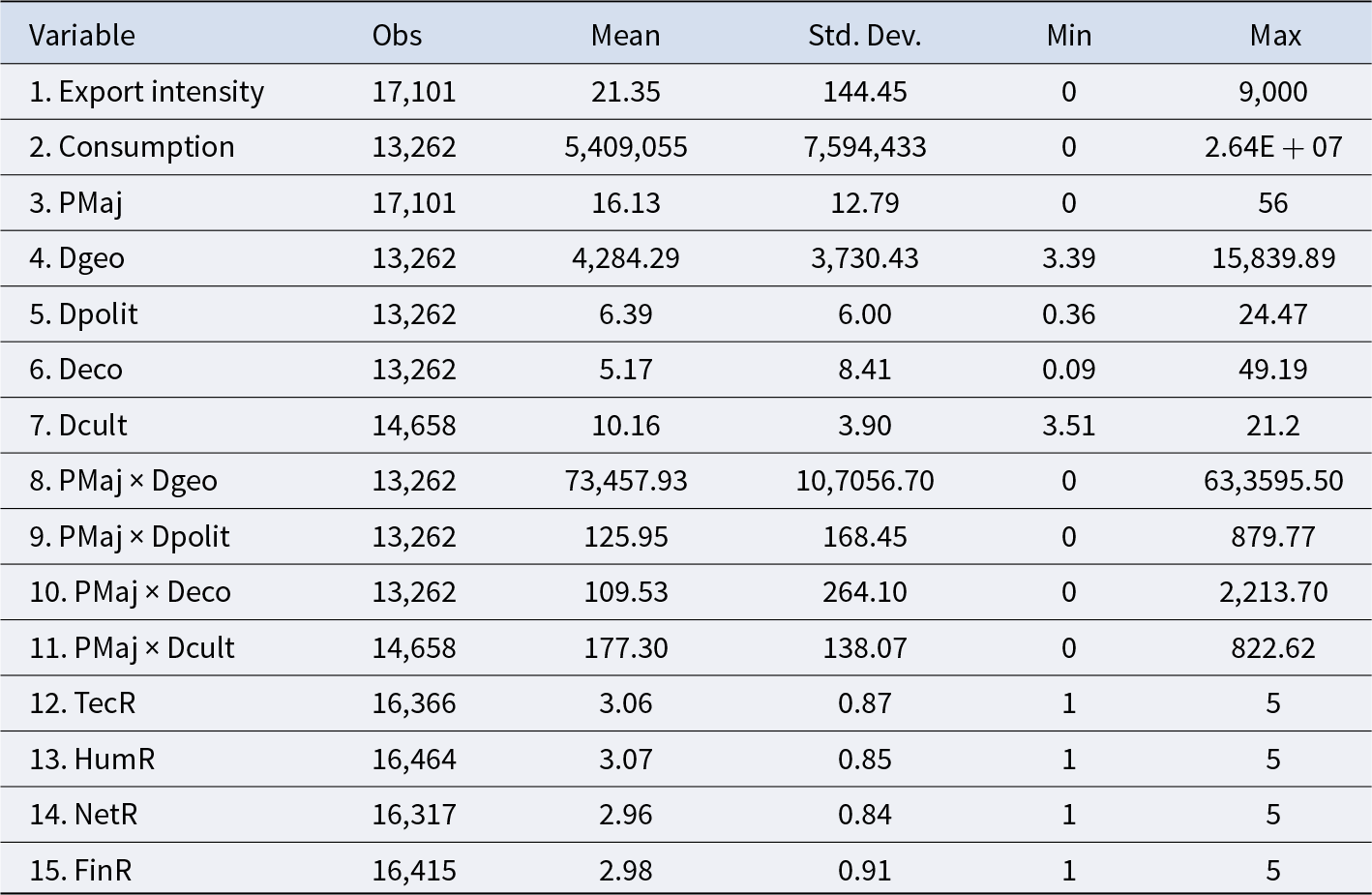

Table 4 shows the descriptive information of the variables of the sample. The maximum number of possible observations is 19,199 (351 wineries and 49 countries. However, this number is not always obtained as not all of the wineries work in all of the destination markets or respond to all of the questions).

Table 4. Descriptive statistics

c. Econometric models

Standard trade theory suggests that export behavior can be understood as the net outcome of two firm-level decisions. The first is whether or not to enter foreign markets, known as “export propensity.” The second is how much to sell overseas, “export intensity” conditional on having entered. This setup is consistent with Melitz (Reference Melitz2003) or Chaney (Reference Chaney2008)-style models, which emphasize the existence of both an extensive and an intensive margin of trade, which is thus being implemented in gravity models that incorporate business heterogeneity.

The econometric strategies employed in this study include Probit and Heckman-Probit two-stage models (Heckman, Reference Heckman1979). The internationalization process of winemakers has been analyzed through a two-stage approach. The first stage is estimated using the Heckman-Probit selection model and a probabilistic Probit model. At this stage, we examine the factors influencing a firm's decision to export. In the second stage, the Heckman methodology is applied, incorporating the inverse Mills ratio to address the issue of selection bias. This stage focuses on the determinants of export intensity, measured as the percentage of export sales relative to total sales. The use of the Heckman model at this stage enables us to mitigate selection bias, an issue that cannot be adequately addressed through a direct application of a multivariate linear regression model. By doing this, it is possible to study which factors have a statistically significant effect on the export propensity of a firm (hypothesis 1 and 3). The equation, therefore, is constructed based on a probit model such as the one described in equation (1).

\begin{align}

D_i^{\exp} = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll}

1\left( {export} \right) \Rightarrow & P\left( {D_i} = 1 \right)\, = f\left( {log\_consumption, PMaj, Dgeo, Dpolit,}\right.\\

& {Deco, Dcult,\,\,PMaj \times\! \,Dgeo, PMaj \times\! \,Dpolit, PMaj \times\! \,Deco,} \\

&\left. {PMaj \times \,Dcult,\;\,TecR, HumR, NetR, FinR} \right) \\

0 \left( {no\,export} \right) & {Otherwise}

\end{array} \right.

\end{align}

\begin{align}

D_i^{\exp} = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll}

1\left( {export} \right) \Rightarrow & P\left( {D_i} = 1 \right)\, = f\left( {log\_consumption, PMaj, Dgeo, Dpolit,}\right.\\

& {Deco, Dcult,\,\,PMaj \times\! \,Dgeo, PMaj \times\! \,Dpolit, PMaj \times\! \,Deco,} \\

&\left. {PMaj \times \,Dcult,\;\,TecR, HumR, NetR, FinR} \right) \\

0 \left( {no\,export} \right) & {Otherwise}

\end{array} \right.

\end{align} Where the dependent variable (![]() $D_i^{exp}$ is a dummy variable taking the value 1 if firm i exported and zero otherwise.

$D_i^{exp}$ is a dummy variable taking the value 1 if firm i exported and zero otherwise.

In the second step, a linear regression is used to analyze the variables that have a significant effect on the volume of business exports (hypothesis 2 and 4). The independent variables of this second step belong to the three above-mentioned types. Moreover, as we have commented, the inverse Mills ratio is introduced as another independent variable. The linear regression used is described in equation (2).

\begin{align}

{Export\_Intensity}_i &= {\beta _1}{Consumtion}_i + {\beta _2}{PMaj}_i + {\beta _3}{Dgeo}_i + {\beta _4}{Dpolit}_i + B_5{Deco}_i \cr

&\quad+ {B}_6{Dcult}_i + {B}_7{PMaj} \times {Dgeo}_i + {B}_8{PMaj} \times {Dpolit}_i \cr

&\quad+ {B}_9{PMaj} \times Deco_i + {B}_{10}{PMaj} \times {Dcult}_i + {B}_{11}{Tec}{R_i} \cr

&\quad+ {B}_{12}Hum{R_i} +

{{\beta _{13}}Net{R_j} + {\beta _{14}}Mill{s_j} + {U_{ij}}}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

{Export\_Intensity}_i &= {\beta _1}{Consumtion}_i + {\beta _2}{PMaj}_i + {\beta _3}{Dgeo}_i + {\beta _4}{Dpolit}_i + B_5{Deco}_i \cr

&\quad+ {B}_6{Dcult}_i + {B}_7{PMaj} \times {Dgeo}_i + {B}_8{PMaj} \times {Dpolit}_i \cr

&\quad+ {B}_9{PMaj} \times Deco_i + {B}_{10}{PMaj} \times {Dcult}_i + {B}_{11}{Tec}{R_i} \cr

&\quad+ {B}_{12}Hum{R_i} +

{{\beta _{13}}Net{R_j} + {\beta _{14}}Mill{s_j} + {U_{ij}}}

\end{align}In the literature on Heckman model, the use of an exclusion variable is often required. The variable “financial resources” was selected. This variable plays a role in the decision process but not in the intensity value. We tested whether this variable had a significant effect in the probit equation, but not in the regression part.

IV. Results

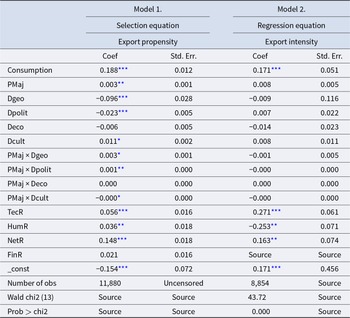

Table 5 presents the results of the Probit-Heckman regression. As we can observe, our results show that the variable that measures the effect of the adjustment of the product to the market (PMaj) has a positive and statistically significant effect at 10%, when the companies makes the decision to export to a certain market. However, it does not display a significant effect on export intensity. It appears to influence the entry decision, but not the volume of exports, an outcome more closely linked to the size of consumption in the destination market and the firm's technological capabilities. As is widely recognized, in the process of selecting new export markets, it is crucial to target those where there is a strong alignment between product characteristics and market requirements. At this stage, firms may face substantial adaptation costs related to compliance with labeling and bottling, as well as modifications to certain product attributes -whether enhancing or moderating them- to better match consumer preferences. These constitute sunk costs incurred at the point of market entry, but they do not subsequently affect the intensity with which the product is sold in that market.

Table 5. Effects of market-product adjustments on export propensity and intensity

Note: Errors are presented in brackets.

***, **, and * denote 1, 5, and 10 percent levels of statistical significance.

Therefore, we can say that, in order to make the export decision, wineries seek markets where the characteristics of their products adjust to the regulations and consumption patterns. However, once the firm has entered these markets, the volume of sales will depend on other factors. Therefore, hypothesis 1 is confirmed but we cannot accept hypothesis 2.

With respect to the moderating effect of the adjustment of the product to the market in the relationship between distance and internationalization, this is statistically significant in the case of the geographical and political distances (PMaj × Dgeo and PMaj × Dpolit). However, this effect is not observed in the export intensity. We believe that the reasons underlying this result are the same as those explaining the outcome of the variable PMaj. Therefore, hypothesis 3 is confirmed in the case of the geographical and political distances, while hypothesis 4 cannot be accepted. In the case of the other two dimensions of distance–economic and cultural–the hypotheses are not confirmed. In the first case, this is due to a lack of statistical significance; in the second, because the result is the opposite of what was expected (a negative and statistically significant sign). Cultural distance shows a positive effect on the entry decision. In other words, greater cultural distance is associated with a higher probability of market entry, which appears highly counterintuitive. We believe that the dimensions used by Hofstede to measure cultural distance do not fully align with the specific characteristics of the wine markets. In fact, our data show that in markets considered culturally distant from Spain according to Hofstede's indicators–such as northern European countries including Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Sweden- Spanish wine has a strong market presence. These are markets where new exporters appear to face fewer barriers to entry.

With respect to the control macro variables, there is a positive and significant effect of the consumption variable on both the propensity to export and the export intensity.

With respect to micro variables, they have been divided into two groups, referring to tangible and intangible resources. With respect to tangible resources, our study confirms the fundamental role of technical resources, which have a positive and significant effect at 1% in both the export propensity of the company and its export intensity. Financial resources had a positive effect on the propensity to export, but are not statistically significant.

On the other hand, within the intangible resources, we should highlight that human resources have a positive relationship and a significance of 5% in the case of export propensity; while their effect is negative and significant at 1% on export intensity. With respect to the network resources, these have a positive and a statistical significance at 1% and 5% in export propensity and intensity, respectively.

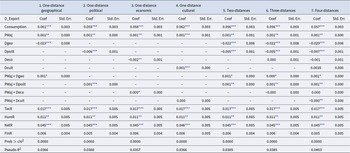

Furthermore, to present more robust results in the export entry decision (which is where the hypotheses have been validated), we estimated Probit models using different combinations of distance dimensions between markets. Given the use of Probit models, marginal effects are reported instead of raw coefficients to allow for a better interpretation of the results (Table 6). Four models include only one dimension of distance: geographical distance (Model 1—Dgeo); political distance (Model 2—Dpolit); economic distance (Model 3—Deco); and cultural distance (Model 4—Dcult). Model 5 includes the two dimensions that showed a positive effect (Dgeo and Dpolit). Model 6 incorporates three distance dimensions (Dgeo, Dpolit, and Deco). Finally, Model 7 includes all four distance dimensions.

Table 6. Marginal effects of market-product adjustments on export propensity (based on probit model)

Note: Standard errors are reported in brackets.

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, and *p < 0.10.

The results are confirmed in the analyses disaggregated by different dimensions of distance, indicating that product–market fit increases the probability of exporting. As shown in the previous estimates, product–market fit yields robust results across all types of econometric models. Therefore, hypothesis H1 is supported.

Regarding the moderating effect of the product–market fit on distance for geographical distance (PMadj × Dgeo) and political distance (PMadj × Dpolit), the effect is positive and statistically significant in the models that include only one distance dimension (Models 1 and 2), as well as in the models incorporating two, three, and four dimensions (Models 5, 6, and 7). Therefore, hypotheses H3 are supported and show robust results in the case of both geographical and political distance.

In contrast, for the other types of distance, the results are either not robust or do not support this hypothesis. For economic distance (Deco), only the single-dimension model (Model 3) shows a positive and significant effect. In the case of cultural distance (Dcult), the models either do not show statistical significance, or when they do, the sign is opposite to what was expected.

Table 6, which presents the marginal effects, highlights the importance of market size from the perspective of macro-level determinants, especially when compared to the effect of distance between markets. Regarding firms’ internal resources, network resources and technological capabilities appear to be more influential than other types of variables considered in the analysis.

V. Conclusion

The objective of this study is to analyze the effect of aligning a winery's product positioning with the conditions of the destination market on its export performance. We believe that our findings offer valuable insights. First, we introduce a novel variable-product–market adjustment which is not commonly used in the literature. This variable allows us to capture the wineries’ strategic decisions in selecting specific product attributes (such as country of origin, grape variety, expert recommendations, and price), and how these align with consumption patterns across diverse markets.

Our results highlight that a good product–market fit increases the likelihood that wineries will engage in exporting. However, this effect is not observed in the intensity of exports. We argue that product–market alignment plays a crucial role in the initial export decision, but once the sunk costs of entering a foreign market have been incurred, the intensity of exports is influenced more by external factors, such as wine consumption in the destination country or the firm's technological capabilities, which are clearly linked to product quality.

Second, a notable finding of our model is the moderating effect of product–market adjustment on transaction costs, specifically distance-related barriers. Our results underscore the importance of accounting for firm-level heterogeneity and decision-making in international trade models. In particular, we show that the negative effect of distance on the export decision is mitigated especially for the geographical and political distances when the product is well aligned with the preferences of the destination market. This is evidenced by the positive and significant coefficients of the moderating variables.

However, this moderating effect is not observed for economic and cultural distance. In the case of economic distance, although the variable has the expected sign, it is not statistically significant. This may reflect the difficulty of overcoming barriers such as differences in income levels between countries or, more generally, entering markets that differ substantially from the exporter's home economy.

This study opens several avenues for future research. First, the analysis could be extended to other major wine-exporting countries. Given that wineries often exhibit idiosyncratic characteristics (Corsi et al., Reference Corsi, Mazzarino and Blanc2025), it would be valuable to examine whether product–market fit plays a similarly important role in different national contexts. Two complementary directions are proposed in this regard. One would involve replicating this study in France the world's leading wine exporter which could substantially strengthen our results. Another would consist of a comparative analysis across several key wine-exporting countries, thereby enhancing the generalizability of our findings.

A further extension would be to disaggregate the product-market fit indicator into its core components, in order to identify which specific dimensions most effectively enhance export performance and moderate the impact of distance across markets. Following Silva and Santos (Reference Silva and Santos2020), the most highly valued attributes include quality, reputation, price, and brand recognition.

Pursuing these research paths could not only refine our theoretical understanding of product-market fit in international contexts but also offer actionable insights for policymakers and industry stakeholders seeking to strengthen the global competitiveness of wine producers.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply indebted to the participants at the seminar held at the Department of Economics, University of Bordeaux, as well as to the anonymous referees and the editor of the journal for their valuable comments and suggestions. Needless to say, we alone bear responsibility for any remaining shortcomings. This study has received financial support from the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain (project PID2022-138886NB-I00) and from the Department of Science, Innovation and Universities of the Government of Aragon (Consolidated Groups S52_23R and S55_23R).

Appendix

Questions used for the definition of the variable Product Positioning Adjustment in the study of destination markets, Vinitrac (Wine Intelligence) and Importers, as well as in the characteristics of Spanish exporting wineries.

Vinitrac (Wine Intelligence) and importers

What importance (%) do each of the attributes have for the consumer when they buy wine?

• The country of origin (France, Spain, Portugal)

• Grape variety (cabernet, grenache)

• Promotional offer

• A brand I am aware of

• Recommendation by friends or family

• The region of origin

• Appeal for the bottle and/or label design

• Whether or not the wine has won a medal or award

• Recommendations from shop staff or shop leaflets

• Recommendation by wine critic or writer

• Taste or wine style descriptions displayed on the shelves or no wine labels

• Alcohol content

• Wine that matches or complements food

• Price

Spanish wineries

Identify the five most important elements for which your wine is chosen

• The country of origin (France, Spain, Portugal, )

• Grape variety (cabernet, grenache)

• Promotional offer

• A brand that the customer is aware of

• Recommendation by friends or family

• The region of origin

• Appeal for the bottle and/or label design

• Whether or not the wine has won a medal or award

• Recommendations from shop staff or shop leaflets

• Recommendation by wine critic or writer

• Taste or wine style descriptions displayed on the shelves or no wine labels

• Alcohol content

• Wine that matches or complements food

• Price