There is no overestimating the importance of arithmetic for the development of human cultures. For the majority of people in the modern world, numbers and arithmetic are a constant part of everyday life. From keeping track of time to financial transactions, most modern societies could not function without arithmetic. For that reason, it has also become a crucial part of modern education. Alongside reading and writing, arithmetic is among the first subjects that children are taught as part of their formal education in most cultures.

Yet this was not always so. As we will see, the origins of arithmetic are not easy to trace but, in the scale of human development, it was not that long ago that all cultures were non-arithmetical. Indeed, as we will also see, there are still cultures that are non-arithmetical. This prompts the fundamental question in the history of arithmetic: how did arithmetic develop? If it is a purely cultural development, how could it develop in such similar ways independently in several cultures? If it is not a cultural development, why are there cultures that not only do not practice arithmetic but do not even have numeral words?

The answer I will argue for in this book is that arithmetic is a cultural development, but it is in important ways based on cognitive abilities that are shared universally by humans (as well as many non-human animals). This makes arithmetic philosophically highly interesting, especially in terms of epistemology. Since antiquity, philosophical accounts of arithmetic (and mathematics more generally) were for millennia dominated by views according to which the subject matter of arithmetic is eternal and independent of human cultures. In this book, I develop a radically different account, according to which the subject matter of arithmetic is a cultural creation. This does not mean that arithmetic consists merely of arbitrary conventions. Nor does it mean that arithmetic is not based on culture-independent factors. But it does imply that we need a non-traditional account of the epistemology of arithmetic; arithmetical knowledge can no longer be assumed to concern eternal truths about objectively existing numbers.

From that background, I want to provide an answer to what I see as the most fundamental question in the epistemology of arithmetic: How can arithmetical knowledge be acquired? Traditionally, philosophers have focused on the various aspects of the question of what arithmetical knowledge is like. These aspects (e.g., apriority, necessity, objectivity) will be important topics for this book. However, I believe that they can be understood better when we have a clearer idea of the way human agents are able to acquire arithmetical knowledge in the first place. Indeed, I believe that traditional epistemology of arithmetic has been hindered by too much focus on analysing the nature of arithmetical knowledge and too little on determining its origins. One main aim of this book is to alter that balance. In doing that, we need to be open to broadening the methodology of epistemology. As I will show, the acquisition of arithmetical knowledge is far from being a question only for philosophy, and proper methodology needs to be sensitive to that.

The question of how arithmetical knowledge is acquired consists of two parts, one concerning the ontogeny of arithmetical knowledge and one concerning its phylogeny and cultural history. The former question asks how human individuals can acquire arithmetical knowledge, while the latter question concerns how human cultures can develop arithmetical knowledge. As we will see, these two questions are tightly connected, and a satisfactory epistemological account of arithmetic will need to address both. I will also show that the question of arithmetical knowledge cannot be separated from studying arithmetic as a human endeavour and not simply as knowledge of formal arithmetic, as is often done in philosophy. In addition to knowledge, we need to consider arithmetical practices, skills, tools and applications. Furthermore, all these aspects need to be considered from the perspective of an individual learning arithmetic, as well as the perspective of a culture developing arithmetic.

The division into the ontogenetic and the phylogenetic/historical questions is particularly important because, as I will show in this book, arithmetic as we know it is ultimately a human cultural phenomenon. That matters for two reasons. First, it means that arithmetic should be studied as a cultural phenomenon. There is a great amount of literature about arithmetic in non-human animals and human infants, but I will show that none of that actually concerns arithmetic. While non-human animals and human infants have capacities with numerosities, these should be distinguished from proper arithmetic. Proper arithmetic is a cultural phenomenon and as such it exists only within arithmetical cultures. Studying arithmetic as a cultural phenomenon requires recognising our evolutionarily developed capacities with numerosities – those that we possess already as infants and share with many non-human animals – but it also requires much more. To understand this we need to have a better grasp of how humans develop and acquire arithmetical knowledge. This is what I will focus on in Part I (Ontogeny) and Part II (Phylogeny and History) of this book.

The second reason why it is important to recognise arithmetic to be a human cultural phenomenon is that we do not need anything further to understand the epistemology of arithmetic. As I will argue in Part III, all the relevant epistemological questions concerning arithmetic can be answered based on the ontogeny, phylogeny and cultural history of arithmetical knowledge. In addition, I will show that this epistemological analysis is also relevant for the ontology of arithmetic. In this, Part III of the book may be seen as controversial. Traditionally, both the ontology and the epistemology of mathematics, including that of arithmetic, have been considered to be subjects for a priori study. In contrast, my treatment of arithmetical knowledge in Parts I and II is based on empirical findings. However, I do not believe that there is any reason for controversy. In addition to showing what arithmetical knowledge is like as a culturally developed phenomenon, the other main purpose of this book – a meta-purpose, if you will – is to show that traditional a priori methodology can fruitfully co-exist with empirically-informed epistemology. Indeed, as Part III seeks to show, we need a synthesis of both in order to understand the epistemology of arithmetic.

Nevertheless, I do recognise that in this book I navigate a fractured landscape. I build on the work of researchers whose views may be inconsistent with each other, and some of them might not be happy with my aims. In the research on arithmetical knowledge, there are different cultures that have different methodologies, different forms of argumentation and different terminology. Taken at face value, the empirical study of numerical cognition and traditional a priori epistemology of arithmetic may seem to be irreversibly incompatible fields of study. Yet that is exactly the kind of attitude that I want to challenge with this book. What I want to show is that the differences in the disciplines are ultimately a richness. But it is a richness we can only recognise if we possess ways of seeing through the superficial differences and find common ground in diverse research paradigms.

In the rest of this introductory chapter, I want to detail how that can be achieved. The main aim of the chapter is to locate my work in the multi-faceted literature generally on mathematical and more specifically on arithmetical knowledge, including both empirical and philosophical approaches. In Section I.4, after there has been a chance to describe the methods and concepts that I will be applying, I will present the structure of the book in detail. But, to give an idea of the way things proceed, after the introduction the work is divided into three parts. In Part I, the focus is on the acquisition of arithmetical knowledge in individual ontogeny. In Part II, I move to the question of how arithmetical knowledge has developed in phylogeny and cultural history. In these two parts, I develop an epistemological account of arithmetic that I then assess philosophically in Part III. According to this account, arithmetical knowledge is a cultural development that is made possible by evolutionarily developed abilities for observing our environment in terms of numerosities. As I will argue, however, this does not make the epistemological status of arithmetical knowledge somehow ‘weaker’. Instead, the key characteristics traditionally associated with arithmetic – namely: apriority, necessity, objectivity and universality – are included in a sufficiently strong sense in the present account.

Before we start, one final thing should be noted. This book is limited to arithmetic, but I am confident that similar treatments could be given to other fields of mathematics. Indeed, early such work exists already for the development of geometrical cognition (Hohol, Reference Hohol2019; Pantsar, Reference Pantsar2021d). Arithmetic warrants a book-length treatment on its own, so I will not enter into discussions on geometry or other fields of mathematics, but at times I will point out connections to them. It should also be added that, when it comes to arithmetic, with the exception of Section 5.3, this book is focused on very basic arithmetic like addition and multiplication. There are two reasons for that choice. First, the scope of the book had to be limited somehow and, as interesting as pursuing the development of more advanced arithmetic would have been, it was not possible to tackle it here. Second, and more importantly, I am confident that the most important philosophical problems are present already when discussing basic arithmetic. When they are not, as in the topics of formalising arithmetic and infinity, I have expanded the scope.

I.1 A Priori Philosophy of Mathematics

I.1.1 Kant’s Synthetic A Priori Knowledge

A good place to start unravelling the cluster of problems involved in explaining the character of mathematical knowledge is the traditional epistemological distinction between a priori and a posteriori. The distinction itself is older, but it is most commonly associated with the work of Immanuel Kant (Reference Kant1787) in Critique of Pure Reason.Footnote 1 The fundamental distinction is that a priori knowledge is acquired independently of experience while a posteriori knowledge is obtained through experience. With this distinction in place, further distinctions can be made. A priori knowledge, since it does not depend on our experiences, was standardly considered to be both necessary and universal, while a posteriori knowledge was considered to never be necessary or universal.Footnote 2 To complete this famous Kantian framework in epistemology, we need one last distinction, the one between analytic and synthetic propositions. According to this semantic distinction, analytic propositions are true entirely by virtue of their meaning, while the truth of synthetic propositions depends on the world and their relation to it.

Some examples will help to make these distinctions clearer. The proposition expressed by the sentence ‘the mass of the fifth planet from the sun is greater than the mass of the sixth planet from the sun’ is synthetic.Footnote 3 There is nothing in the meaning of the sentence that dictates whether it is true or false; that depends on how things stand in the world. As it happens, scientists have established that the proposition is true, based on observations of the solar system. These observations are complex in character. They require instruments like telescopes, as well as mathematical calculations. A theory of gravitation, at present either Newtonian mechanics or the general theory of relativity, needs to be applied in order to calculate the masses of the two planets. These physical theories, in turn, rely heavily on mathematical theories. It is only with the help of these physical and theoretical instruments that we are able to establish the truth of the proposition. Nevertheless, knowledge of that truth clearly depends on experience. It is only through applying our senses, in this case primarily vision, that we are able to ascertain that Jupiter, the fifth planet, indeed has a greater mass than Saturn, the sixth planet. Therefore, the proposition is knowable a posteriori. Moreover, since the truth of the proposition clearly depends on the world, it is a case of synthetic a posteriori knowledge.

This example should make it clearer what the differences between a priori and a posteriori, on the one hand, and between analytic and synthetic, on the other hand, entail. Since the above proposition about Jupiter and Saturn is synthetic a posteriori knowledge, under the traditional view it is neither necessary nor universal. That Jupiter has a greater mass than Saturn is a contingent fact about the solar system; with a different course of actions after the Big Bang the matter could have been otherwise. In addition, in another solar system it could be the case that the sixth planet is indeed bigger than the fifth planet from the sun, making the truth a non-universal one. The truth may appear to be as certain as any truth, yet it is categorically distinct from analytic necessary and universal truths.

What kind of truths are analytic? In Kant’s (Reference Kant1787) view, in an analytic truth the concepts in the proposition are in a particular type of containment relationship. The proposition ‘all bachelors are unmarried’ is a standard example of this. It is true entirely in virtue of its meaning, that is, the definition of the subject ‘bachelor’ includes the predicate ‘is unmarried’. Unlike in the case of Jupiter and Saturn, we do not need to observe the world to ascertain its truth.Footnote 4

With the distinctions between a priori and a posteriori, as well as analytic and synthetic, in place, Kant asked what kind of knowledge there is. We have seen that there is synthetic a posteriori and analytic a priori knowledge. For Kant, analytic a posteriori was an impossible combination but, importantly, he argued that there is synthetic a priori knowledge, that is, knowledge that is acquired independently of observations but which is nevertheless true not only in virtue of the meaning of the propositions. Metaphysics, the kind that Kant was involved in, was one case of synthetic a priori knowledge. But, for the present purposes, the more interesting case is mathematical knowledge, which Kant also saw as being synthetic a priori. Kant used examples from both arithmetic and geometry to make his point. In this book I will focus on the former idea of Kant, that is, that both syntheticity and apriority are characteristics of arithmetical knowledge. In the sentence ‘7 + 5 = 12’, for example, the meaning of ‘12’ is not included in the meaning of ‘7’ or ‘5’, or the combination of the two (Kant, Reference Kant1787, B15–B16). But nevertheless, this knowledge is a priori in character. It is acquired by reason, and not through observation. Thus, Kant argued that arithmetic, like all pure mathematics, is synthetic a priori, while also being necessary and universal.Footnote 5

I.1.2 Mathematical Objects and Platonism

In that last claim of Kant, however, resides a potential problem. If arithmetical knowledge, as part of pure mathematics, is synthetic, how can it be necessary and universal? If a proposition being synthetic means, as specified in Section I.1.1, that its truth depends on its relationship with the world, does this not imply that propositions of pure mathematics should be assessed in terms of their relationship with the world of mathematical objects? As it has turned out, answers to this question have dominated the philosophy of mathematics ever since Kant. In addition, pre-Kantian philosophical views concerning mathematics can also be framed in terms of this question.

Although it was present already in pre-Socratic philosophy, the most famous and influential pre-Kantian view concerning mathematics can be found in the work of Plato. He argued that, since sense perception can never give knowledge about the mathematical objects themselves, knowledge about mathematical objects must be gained through reason and recollection (Plato, Reference Plato1992, 527a–b). Thus, the idea of mathematical knowledge being a priori was already present in antiquity. But equally crucial to Plato’s philosophy was the idea that there is a world of mathematical objects and by reason we can gain knowledge of that world. In the philosophy of mathematics, the realist position according to which mathematical objects and structures exist in a mind-independent fashion is still called platonism.Footnote 6

Platonism clearly provides an answer to the question about syntheticity. Propositions of pure arithmetic are synthetic because their truth depends on the state of things in the platonic world of mathematical ideas. Since truths about that world are necessary and universal, arithmetical knowledge can be at the same time synthetic a priori and both necessary and universal. The problem with this answer, however, is in explaining how our mental faculties can be used to get knowledge of mathematical objects in the platonic world. If mathematical objects such as numbers exist in the platonist sense, they must be abstract. But abstract objects, by definition, are non-spatial, non-temporal and causally inactive. This causes a problem in combining our cognitive faculties with the abstract world of mathematical objects. As famously asked by Benacerraf (Reference Benacerraf1973), how can we as physical subjects get knowledge of abstract, non-physical objects? Some platonists, like Gödel (Reference Gödel, Benacerraf and Putnam1983) and Penrose (Reference Penrose1989), have proposed a special epistemic faculty for mathematics as an answer. However, in modern philosophy of mathematics, such explanations have found limited popularity. Instead, as we will see in Section I.1.3, modern platonism has tended to deal with this epistemological problem by distancing itself from Kant’s idea that mathematical knowledge is synthetic a priori.

I.1.3 Analytic A Priori and Mathematical Objects

The importance of Benacerraf’s (Reference Benacerraf1973) question for modern philosophy of mathematics is indisputable. By pointing out the epistemological difficulty of combining an empiricist, observation-based, epistemology with a platonist ontology of mathematical objects, his question is problematic also for the Kantian notion of synthetic a priori mathematical knowledge. After all, if not the platonic world of mathematical ideas, then some other mind-independent aspects must determine mathematical truths – otherwise mathematical knowledge would be analytic a priori. But what could these aspects be and how could we have epistemological access to them?

In Section I.1.4, I will propose an answer to this question which I will defend throughout this book. But in the contemporary literature on philosophy of mathematics, especially in the tradition following Frege (Reference Frege1884), a more common solution to the problem is to deny that mathematical knowledge is synthetic a priori and contend that it is analytic. However, this rejection prompts a potential difficulty. If mathematical truths are analytic, how can we include mathematical objects in our mathematical theories? Truths like ‘all bachelors are unmarried’ are unproblematic analytic truths since they do not make the claim that there exist such things as bachelors. The only claim that is made is that if somebody is a bachelor, then he is unmarried. Certainly, many mathematical statements are like that, for example, the arithmetical statement ![]() (‘all numbers are equal to themselves’). However, integral to mathematics are existential statements, for example, of the type

(‘all numbers are equal to themselves’). However, integral to mathematics are existential statements, for example, of the type ![]() . For that statement to be true, there has to exist a number between

. For that statement to be true, there has to exist a number between ![]() and

and ![]() . But how can we make an analytic existential statement like that? Does the truth of the statement not depend on whether numbers exist or not? And if numbers do not exist, as Hartry Field (Reference Field1980), among others, has argued, such existential statements are, strictly speaking, false. Hence, a great part of mathematical statements, given a literal reading, would not be analytic truths but, more than that, they would not be truths at all.

. But how can we make an analytic existential statement like that? Does the truth of the statement not depend on whether numbers exist or not? And if numbers do not exist, as Hartry Field (Reference Field1980), among others, has argued, such existential statements are, strictly speaking, false. Hence, a great part of mathematical statements, given a literal reading, would not be analytic truths but, more than that, they would not be truths at all.

A famous answer to this problem was provided by Frege (Reference Frege1884), who argued that also analytic a priori truths can make existential claims, through introducing new objects. In the following analytic truth, for example, we introduce new abstract objects:

The direction of line ![]() is the same as the direction of line

is the same as the direction of line ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() and

and ![]() are parallel.

are parallel.

Through the equivalence relation of lines being parallel, we are able to introduce new abstract objects, namely directions, by an analytic truth. Similarly, it is possible to introduce numbers as abstract objects. An analytic truth called Hume’s Principle (Boolos, Reference Boolos, Jeffrey and Burgess1998, p. 181) states that the number of ![]() s is equal to the number of

s is equal to the number of ![]() s if and only if the

s if and only if the ![]() s and the

s and the ![]() s are equinumerous, that is, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the

s are equinumerous, that is, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the ![]() s and the

s and the ![]() s:

s:

Here the operator ‘#’ takes the concept of one-to-one correspondence and introduces new objects, that is, natural numbers.

These two analytic truths are cases of abstraction principles (see, e.g., Linnebo, Reference Linnebo2018b). They ‘carve up’ previous propositional conceptual content (e.g., about equinumerosity) and give us a criterion of identity for new objects (e.g., natural numbers). Such abstraction principles have been used to refer to abstract mathematical objects by the neo-Fregeans Bob Hale and Crispin Wright (Reference Hale and Wright2001, Reference Hale, Wright, Chalmers, Manley and Wasserman2009), as well as recently by both Agustín Rayo (Reference Rayo2015) and Øystein Linnebo (Reference Linnebo2018b). Rayo calls his position subtle platonism, while Linnebo writes about ‘thin objects’. The underlying idea in both accounts is that, by introducing mathematical objects via abstraction principles, we avoid Benacerraf’s (Reference Benacerraf1973) problem because the existence of abstract objects does not make any demands of the world. There is nothing problematic about epistemic access to abstract objects, since they are simply introduced by analytic truths, more specifically as singular referents in abstraction principles like Hume’s Principle (for more, see Pantsar, Reference Pantsar2021c). Thus, according to Linnebo, through such a process of ‘reconceptualisation’ we get ontological commitment to objects such as numbers (Linnebo, Reference Linnebo2018b, p. 23). We can therefore make existential statements about mathematical objects without being inconsistent, all the while staying within the realm of analytic a priori.

I.1.4 Kant Revisited and Reinterpreted

We will return to the topic of the previous section in Chapter 9, but for now it is important to recognise that the neo-Fregeans, Rayo and Linnebo all appear to be committed to the view that mathematical knowledge is analytic a priori. Indeed, the Kantian notion of mathematical knowledge as synthetic a priori has become increasingly unpopular in modern philosophy of mathematics. However, I believe that this is potentially misguided. As I will show in this book, there is a lot to like about the idea that mathematical knowledge is synthetic a priori, as long as we can explain properly what we mean by ‘synthetic’ and ‘a priori’. The way I will argue for this position is by including state-of-the-art data and theories from the empirical study of arithmetical and early quantitative cognition. Naturally, none of this data were available for Kant (or, for that matter, Frege). But I contend nevertheless that modern empirical research can be fruitfully understood in a Kantian context.

One of the most famous parts about Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason is the way he compares his philosophy to the revolution in astronomy due to Copernicus:

Hitherto it has been assumed that all our knowledge must conform to objects. But all attempts to extend our knowledge of objects by establishing something in regard to them a priori, by means of concepts, have, on this assumption, ended in failure. We must therefore make trial whether we may not have more success in the tasks of metaphysics, if we suppose that objects must conform to our knowledge.

What I will be arguing for in this book is something similar: I propose that we can understand the nature of mathematical objects better if we focus primarily on the characteristics of mathematical knowledge. In this, I am moving along the same lines as Rayo (Reference Rayo2015) and Linnebo (Reference Linnebo2018b) who also stress the primariness of knowledge (for them, concerning true abstraction principles) over objects in their argumentative methodology. However, there is an important difference in my approach. While I agree that, under a suitable (contextual) definition, mathematical knowledge is a priori, I do not believe that traditional a priori philosophical methodology suffices, or should even be prioritised, in studying the character of mathematical knowledge.

I.2 A Posteriori Approaches to Mathematical Knowledge

I.2.1 Empiricism

So far, I have focused on a priori approaches to mathematical knowledge, but there have also been well-known a posteriori approaches. These should be divided into two distinct positions. According to the first one, empirical research is integral to understanding what mathematical knowledge is like and how it is acquired. Let us call this the methodological a posteriori approach. According to the second position, arithmetical knowledge is fundamentally a posteriori. Let us call this the epistemological a posteriori position.

One can simultaneously subscribe to both the methodological and the epistemological a posteriori views on mathematical knowledge, that is, hold the position that mathematical knowledge is fundamentally based on observations and that it should be studied via empirical methodology. But it is also possible to subscribe to just one of the a posteriori views. Indeed, the account I argue for in this book takes empirical methodology to be crucial for understanding the development and character of arithmetical knowledge. Yet, I will argue that arithmetical knowledge is best understood as a priori, under a proper understanding of the term.

But this connection between methodological and epistemological a posteriori can also go the other way around. Historically, this other direction has in fact been more common. The most famous accounts that connect mathematical knowledge to the empirical, those provided by John Stuart Mill (Reference Mill and Robson1843) and Philip Kitcher (Reference Kitcher1983), both stick to essentially similar a priori philosophical methodology, as have platonist philosophers traditionally. Both accounts are empiricist in that they take mathematical knowledge to be fundamentally empirical in character, yet their methodology does not involve significantly engaging with empirical studies on mathematical cognition or mathematical practice. For Mill, the reason could be simple: there simply was no reliable and relevant empirical data available in the nineteenth century. And, even though Kitcher wrote his book almost a century and a half later, the situation had changed surprisingly little. As will be seen, there was already empirical research that pointed to future directions in the study of arithmetical cognition, but in the early 1980s the situation was radically different from the current state of the art. Therefore, the late emergence of methodological a posteriori approaches to mathematical knowledge is perhaps best explained by the simple fact that reliable and relevant empirical research has only started to accumulate during the last few decades.

But why was the epistemological a posteriori approach so unpopular among philosophers for so long – and indeed still is? Given that generally in epistemology there has been less and less room for rationalist approaches since the eighteenth century – although with notable exceptions like Hegelian philosophy – this was a somewhat peculiar state of affairs. As empirical data was given increasing importance in epistemology, mathematical knowledge remained largely a bastion of rationalism. The way mathematical knowledge was elucidated was through the traditional a priori methodology, with the – either explicit or implicit – understanding that mathematical knowledge is fundamentally different from most other types of knowledge.

The reason for the historical lack of popularity of epistemological a posteriori accounts can, I believe, be elucidated by an analysis of Mill’s empiricist philosophy in his main work on the topic, the book A System of Logic (Mill, Reference Mill and Robson1843). Previous empiricists like Hume had held mathematical truths to be analytic, but in Mill’s philosophy mathematical statements are not given any special epistemological status. For him, mathematical knowledge – including that of arithmetic – is based on experiences of the physical world, just like all knowledge. The necessity of even the very basic laws, such as the law of identity ![]() is questioned by Mill: ‘How can we know that a forty-horse power is always equal to itself, unless we assume that all horses are of equal strength?’ (Mill, Reference Mill and Robson1843, p. 170). Since all horses quite clearly are not of equal strength, Mill seems to argue that we cannot know that a forty-horsepower is always equal to itself. But this line of reasoning is quite confusing. If Mill means that we cannot equate the strength of an actual group of forty horses with that of another, he is of course correct. But it is hard to see the point of this observation, since nobody would claim the opposite. Similarly, if he means that we cannot be sure that the abstract unit of power ‘forty-horsepower’ does not match the power of all groups of forty horses, he is no doubt making a correct claim, but again nobody would claim the opposite. But if Mill’s point really is to question that the abstract unit of ‘forty-horsepower’ is equal to itself, he must be taking mathematical objects to be tied to physical objects in a very concrete way (for more, see Pantsar, Reference Pantsar2016a).

is questioned by Mill: ‘How can we know that a forty-horse power is always equal to itself, unless we assume that all horses are of equal strength?’ (Mill, Reference Mill and Robson1843, p. 170). Since all horses quite clearly are not of equal strength, Mill seems to argue that we cannot know that a forty-horsepower is always equal to itself. But this line of reasoning is quite confusing. If Mill means that we cannot equate the strength of an actual group of forty horses with that of another, he is of course correct. But it is hard to see the point of this observation, since nobody would claim the opposite. Similarly, if he means that we cannot be sure that the abstract unit of power ‘forty-horsepower’ does not match the power of all groups of forty horses, he is no doubt making a correct claim, but again nobody would claim the opposite. But if Mill’s point really is to question that the abstract unit of ‘forty-horsepower’ is equal to itself, he must be taking mathematical objects to be tied to physical objects in a very concrete way (for more, see Pantsar, Reference Pantsar2016a).

For Frege, Mill’s philosophy meant throwing away everything that is precious about mathematical knowledge, and he ridiculed Mill’s view as reducing mathematics to ‘pebble arithmetic’:

Often it is only after immense intellectual effort, which may have continued over centuries, that humanity at last succeeds in achieving knowledge of a concept in its pure form, in stripping off the irrelevant accretions which veil it from the eyes of the mind. What, then, are we to say of those who, instead of advancing this work where it is not yet completed, despise it, and betake themselves to the nursery, or bury themselves in the remotest conceivable periods of human evolution, there to discover, like John Stuart Mill, some gingerbread or pebble arithmetic. … A procedure like this is surely the very reverse of rational, and as unmathematical, at any rate, as it could well be.

Frege was thus worried that Mill’s effort to found arithmetic on empirical origins will take us away from the true essence of arithmetical truths and move the discourse to irrelevant details concerning the historical or personal discoveries of the truths. Given the direct connection Mill saw with physical objects (like horses) and abstractions (like horsepower), this criticism is easy to understand. Nevertheless, the origins that Frege saw as irrelevant are irrelevant to him because of his prior philosophical conviction that mathematical propositions have an essence that is independent of the cognitive origins of understanding them. Therefore, in the above passage Frege seems – to some degree – to conflate mathematics and the philosophy of mathematics. Clearly in mathematics, we do not want to bring in the empirical and psychological dimensions that may be involved. But, if we dismiss those dimensions as irrelevant for the epistemology of mathematics, we have already – without argument – rejected the view that mathematical knowledge could be somehow based on an empirical foundation.Footnote 7

From a modern perspective, it is not as easy to accept Frege’s dismissal of the possibility of mathematical knowledge having an empirical foundation. Mill’s empirical account may have been crude in its understanding of abstraction, but a more sophisticated empiricist approach to mathematics was presented by Kitcher (Reference Kitcher1983). In Kitcher’s view, mathematical knowledge concerns generalisations of operations that we do in our environment. In our environment, we may play around with collections of pebbles and learn that the operations obey certain rules. We can then generalise on these rules and end up with rules of arithmetic applicable not only to small collections of pebbles, but also to larger quantities of any kind of objects, even up to infinity. Frege might continue to dismiss this as ‘pebble arithmetic’, but there is an important difference to Mill’s empiricist philosophy. The pebbles (or other physical objects) play an integral psychological role in the process, but the arithmetical rules we learn in this way are operational generalisations, that is, abstractions that are no longer tied to particular sets of objects.

This topic will be given a lot of attention throughout this book, but initially it seems plausible that Kitcher is fundamentally correct about the way we first learn about arithmetical rules. At least for most people, empirical aspects play an important role in the early learning of arithmetic. As we will see, it is also plausible that the development of arithmetic as an intellectual discipline was initially tightly connected to empirical aspects. However, we can accept these origins without making the empiricist assumption that arithmetical knowledge is a posteriori. There are two reasons for this. First, after being aided by physical objects in the learning process, the empirical methods are not indispensable, which makes arithmetical knowledge different in character from empirical knowledge. Children may use their fingers to count and add, for example, but, while they may be integral for the learning process, such empirical methods can be abandoned later. Second, even if arithmetical statements had their origins in empirical procedures, they are not empirically confirmable or falsifiable under any relevant reading of ‘empirical’. For one thing, arithmetical calculations are neither corroborated nor refuted by direct experiment. If some arithmetical theorem is proved, an empirical corroboration of the proof has no value. The sum ![]() is true because it follows the axioms of arithmetic. Conducting a physical experiment with, say, pebbles would not make this any more certain.

is true because it follows the axioms of arithmetic. Conducting a physical experiment with, say, pebbles would not make this any more certain.

It is thus crucial to note that mathematical proof has its own special character and an epistemological theory must be sensitive to that. Hence, empiricist theories of mathematical knowledge seem to be fundamentally flawed, even though I – unlike Frege – support the idea that the empirical processes that are used in learning arithmetic are relevant for the epistemology of arithmetic. What I agree with Frege on is that these processes should not be confused with the character of arithmetical truths. In modern literature, this distinction is best known as the difference between the context of discovery and the context of justification (Frege, Reference Frege and Heijenoort1879). What Frege is writing about is the context of justification, how arithmetical truths can be established. He deems the context of discovery, how arithmetical truths are learned, to be irrelevant for the context of justification. This was the foundation of Frege’s criticism toward psychologism of the late nineteenth century, in particular that of Schröder (Reference Schröder1873).

What Frege thus wanted to do was to find a logical basis for arithmetic that is independent of the unpredictability of the psychological processes involved. Frege attributes to Schröder the view that we arrive at the concept of number by abstracting away every other property, such as colour and shape, from our observations. When we see, for example, a bag of oranges, we can abstract away everything that distinguishes the objects as oranges and arrive at the number of oranges. Frege (Reference Frege1884) pointed out serious difficulties with this approach. For instance, there are often various ways of extracting a number out of objects. If we have, say, a plateful of grapes, do we mean the number of individual grapes, the number of bunches of grapes, or perhaps something else – that there is one plate, for example? For Frege, a number could not be a property of the objects because our choice of extracting number is arbitrary in a way that the colour of the grapes, for example, clearly is not.

In general, I believe Frege’s criticism of psychologism mostly hits its target (see Pantsar, Reference Pantsar2016a for more). Like Frege, I find abstraction of the Schröder-type to run into the danger of arbitrariness: only certain types of abstraction let us extract the desired number, but in Schröder’s account there does not seem to be any reason why one would prefer one extracted number over another. However, a lot has happened in the century and a half after Schröder presented his theories. As I will argue in this book, currently we have good reasons to think that a certain type of abstraction to the numerosity of macro-level objects does have a privileged position over other types. But even so, I will show, it is problematic to conceive of number as a property of objects. Instead, what I will do in this book is to follow Kant’s Copernican revolution. We should not focus primarily on what the objects that numbers are associated with are like. Instead, we should focus on what knowledge of numbers is like and how it is made possible by cognitive processes.

I.2.2 Empirical Study of Mathematical Cognition

While I have criticised above the epistemological a posteriori approaches to mathematical knowledge, in this book I will make substantial use of the methodological a posteriori approach. Indeed, one of the main tenets of this book is that the philosophical study of mathematical knowledge should be informed by the empirical study of mathematical cognition and its development. Mathematical cognition is a relatively new field for empirical study and solid results have only properly emerged during the past few decades. This is not to say that the empirical study of mathematical cognition does not have a longer history. From learning mathematics (e.g., Skemp, Reference Skemp1987) to mathematical invention (e.g., Hadamard, Reference Hadamard1954), mathematical cognition was an important topic in psychology in the latter part of the twentieth century. While much of that work also carries philosophical relevance, for the epistemology of arithmetic the important change has taken place mostly starting from the 1990s. Since then, a widespread view has started to emerge that arithmetical ability and arithmetical knowledge are not solely the domain of sufficiently mature, educated human individuals. Data emerged on infant ability with numerosities, most famously in the experiment reported by Karen Wynn (Reference Wynn1992), according to which infants can carry out rudimentary addition and subtraction operations. Similar arithmetical abilities were reported in many animals, including ‘numerical and arithmetic abilities in non-primate species’ (Agrillo, Reference Agrillo, Cohen Kadosh and Dowker2015) and ‘arithmetic in newborn chicks’ (Rugani et al., Reference Rugani, Fontanari, Simoni, Regolin and Vallortigara2009).

Stanislas Dehaene, one of the most influential researchers in the field, argued in his widely read book The Number Sense (Dehaene, Reference Dehaene2011) that these abilities are due to our brains possessing an innate number sense that we share with many non-human animals:

How can a 5-month-old baby know that 1 plus 1 equals 2? How is it possible for animals without language, such as chimpanzees, rats, and pigeons, to have some knowledge of elementary arithmetic? My hypothesis is that the answers to all these questions must be sought at a single source: the structure of our brain.

For the epistemology of arithmetic, the verification of Dehaene’s hypothesis would be monumental. Instead of looking for explanations of arithmetical knowledge in mathematical objects, we should focus on the structure of the brain. If arithmetical knowledge, as Dehaene claims, is present in babies and non-human animals, then clearly abilities exclusive to sufficiently mature humans, such as language, are not necessary for the development of arithmetic. This would suggest a Kantian turn with a modern empirical twist: if we can explain how arithmetical knowledge emerges in non-human animals and human infants, we are likely to be dealing with the very foundation of arithmetical knowledge. Even modern formal axiomatic systems would essentially be expansions and specifications of an innate arithmetical cognitive system that is entirely the product of biological evolution.

Susan Carey, another researcher whose work will be extensively discussed in this book, has called these types of evolutionarily developed cognitive systems core cognition (Carey, Reference Carey2009).Footnote 8 Core cognitive systems are thought to differ ‘systematically from both sensory/perceptual representational systems and theoretical conceptual knowledge’ (Carey, Reference Carey2009, p. 10) and core cognition is thought to be ‘the developmental foundation of human conceptual understanding.’ (p. 11). In Chapter 1, we will see what kind of systems have been suggested as the relevant core cognitive systems for the development of arithmetical knowledge. But, for now, it is important to emphasise the difference of the core cognitive framework to the kind of empirical work that was done on mathematical cognition for most of the twentieth century. The psychology of learning mathematics was an important topic and Piaget’s (Reference Piaget1970) theory of stages of cognitive development, for example, had a great influence on mathematics education (see, e.g., Ojose, Reference Ojose2008). But, contrary to Piaget, who believed that arithmetical knowledge is only possible once the child has gone through several stages of cognitive development (namely, the stages of concrete operations and formal operations, after going through the earlier sensorimotor and preoperational stages (Piaget, Reference Piaget1970)), Dehaene is arguing that already infants only a few months of age have arithmetical knowledge. This is a paradigmatic difference when it comes to applying empirical data to the study of arithmetical knowledge.

I.3 A Synthesis of Two Approaches

I.3.1 Incongruent and Misleading Terminology

In this book, I will argue that arithmetical knowledge is best studied in an interdisciplinary manner, using methodology and results from both the empirical study of numerical cognition and the philosophical study of arithmetical knowledge. To be more precise, rather than explicitly arguing for this position, I will show that applying this interdisciplinary approach gives us the best understanding of arithmetical knowledge and how it is developed and acquired. One important problem in establishing a platform for fruitful interdisciplinary research, however, is to agree upon congruent terminology. This is a particularly pressing challenge in the empirical research on numerical cognition since the literature in different disciplines includes radically different application of the central terms. In the noted quotation of Dehaene, for example, he asks ‘How can a 5-month-old baby know that 1 plus 1 equals 2?’ But, from a philosophical perspective, this question makes little sense. Whatever the ability of the baby is, few philosophers would be ready to ascribe knowledge to it.

Yet it would be unreasonable to dismiss Dehaene’s question just because his language does not conform to the standard jargon of epistemologists. Whatever he means by knowledge, we can be confident that Dehaene does not think that infants have arithmetical knowledge in the same sense as mature humans have knowledge of the statement ![]() . In this way, I believe philosophers should generally give empirical literature a charitable reading and not get stuck with terminological issues, just as empirical scientists should give philosophers the benefit of doubt when they show lack of fluency with the empirical literature.

. In this way, I believe philosophers should generally give empirical literature a charitable reading and not get stuck with terminological issues, just as empirical scientists should give philosophers the benefit of doubt when they show lack of fluency with the empirical literature.

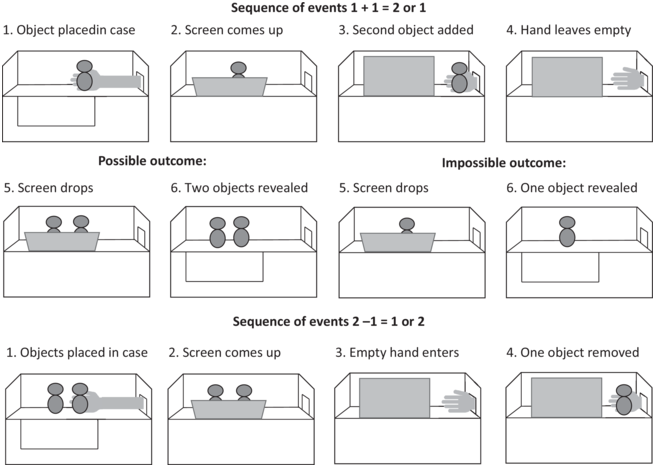

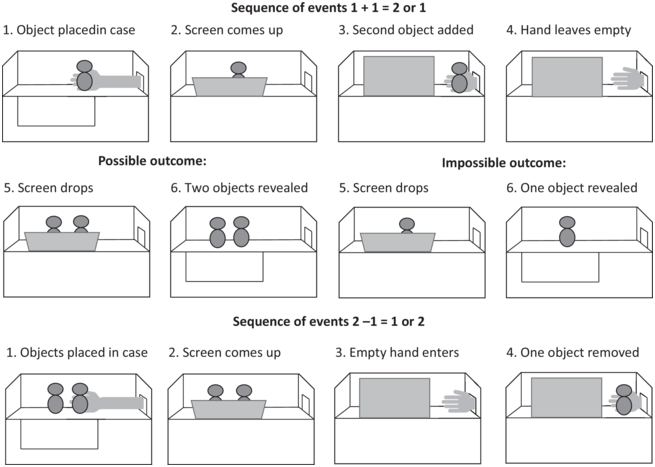

However, this kind of application of the principle of charity does not render the question of what exactly Dehaene did mean any less important. It is my belief that not only interdisciplinary research with philosophers but also empirical research itself would benefit from a clear and unambiguous use of terminology. Let us take a look at a couple of examples to see why. As mentioned earlier, one of the most influential experiments in the field of numerical cognition was conducted by Karen Wynn (Reference Wynn1992). In the experiment, 5-month-old infants were shown dolls in settings that were designed to test whether the infants had numerical abilities. The infants were shown one doll and another doll put behind a screen. In some trials, one of the dolls was removed clandestinely before the screen was lifted. In others, both dolls remained. In another variation, the infants were initially shown two dolls and then after one was visibly removed, either one or two dolls were revealed (Figure I.1).

Figure I.1 The setting on the experiment reported in Wynn (Reference Wynn1992).*

* She tested 5-month-old infants in trials that alternated between one-item and two-item results. The experimenter removed one doll through a hidden trap door in half the trials. The possible and impossible outcomes are reversed for the lower sequence of events.

What Wynn’s experiment (and its many replications) showed was that the infants reacted with surprise (measured as longer looking times) to the situation in which only one doll remained. This is what Dehaene referred to when he asked how 5-month-old infants can know that one plus one equals two. In Wynn’s formulation: ‘Here I show that 5-month-old infants can calculate the results of simple arithmetical operations on small numbers of items. This indicates that infants possess true numerical concepts, and suggests that humans are innately endowed with arithmetical abilities’ (Wynn Reference Wright1992, Abstract). Several claims are made in this short passage. Infants can calculate results of arithmetical operations. They possess numerical concepts and have innate arithmetical abilities. In this book, I show that all these statements are fundamentally wrong. Nevertheless, I believe that Wynn’s research is highly relevant and the results applicable in explaining the development of arithmetical knowledge.Footnote 9

The seemingly contradictory position in which I can take claims by empirical researchers to be wrong but still consider them important for explaining arithmetical knowledge becomes unproblematic when we understand the root of the problem. As will become clear in this book, I do not believe that infants or non-human animals calculate results of arithmetical operations, nor do I believe that they possess innate numerical concepts or arithmetical abilities. What they do is show behaviour that can be described in terms of arithmetical operations. The infant does not know that one plus one equals two, but if it did know it, the behaviour would likely be quite similar. Thus, the problem is not in the experimental data itself, it is with the cognitive ascriptions made in order to explain the data.

One important consequence of this type of use of incongruent terminology, as pointed out by Rafael Núñez (Reference Núñez2009), is the potential confusion of the explanans with the explanandum:

A major problem in most accounts of the concept of number is that scholars often introduce crucial elements of the explanans in the very explanandum. That is, they take number systems as pre-given and introduce them as a part of the explanatory proposal itself … Gallistel et al. (Reference Gallistel, Gelman, Cordes, Levinson and Jaisson2006, 247), for instance, speak of ‘mental magnitudes’ referring to a ‘real number system in the brain’, where the very real numbers are taken for granted, and put them ‘in the brain’.

The task at hand for Gallistel et al. (Reference Gallistel, Gelman, Cordes, Levinson and Jaisson2006) was to explain the development of real number systems based on an evolutionarily developed mental magnitude system. In Section 1.2, we will see how such explanations are developed in detail, but it is easy to see that something strange is going on if the mental magnitudes are equated with real numbers. The former, according to the hypothesis of Gallistel and colleagues, are innate and the product of biological evolution. The latter, on the other hand, are the product of a long line of development in mathematics. Perhaps there could be a straightforward explanation of how real number concepts are developed and acquired based on innate mental magnitudes – although I will argue that this is not the case – but we must not confuse the two notions (real number concepts and innate mental magnitudes) when presenting the phenomenon that needs to be explained.

These types of problems concern many accounts of the cognitive basis of numbers. When philosophers discuss numbers, they are concerned with abstract objects. There are many different ways of understanding what this abstractness entails (see, e.g., Rosen, Reference Rosen and Zalta2020 for details), but the general understanding is that numbers as abstract objects should be distinguished from mental or physical representations of numbers. Whatever numbers are, they are something different from my utterance of the word ‘three’ or writing the symbol ‘3’ on a piece of paper. Importantly, the abstractness of numbers also makes it necessary to distinguish between numbers and mental number concepts. At some point in my development, I acquired the number concept THREE.Footnote 10 However, this concept is not the number three. This is a crucial point to make, and it goes against the terminology used by many empirical researchers. Gallistel, for example, writes that ‘Behavioural and electrophysiological data now convincingly establish the existence of numbers in the brain – in animals from insects to humans’ (Gallistel, Reference Gallistel2018, p. 1). Ironically, Gallistel had earlier, together with Gelman, proposed the term ‘numeron’ to refer to the representation of ‘number in the brain’ (Gelman & Gallistel, Reference Gelman and Gallistel1978). But now that ‘numbers’ and ‘numerons’ are confused, we get sentences like the following: ‘Much of the work on numbers in the brain focuses only on the referential role of numerons – more particularly, on their reference to numerosities’ (Gallistel, Reference Gallistel2018, p. 1). I agree with Gallistel about the content of much of the work that he is referring to. The reference of numerons to numerosities is indeed a central topic of research for the topic at hand. However, that work is not about numbers in the brain. Granted, it is possible to entertain the view that numbers exist in the brain, and only in the brain. But that is a specific – and quite radical – claim that cannot simply be assumed to hold.

I.3.2 Key Terminology, Conceptual Analysis and Empirical Data

To avoid the kind of confusions discussed in Section I.3.1, it is clear that we must get rid of the incongruent terminology. To begin with, I want to establish a few basic terminological distinctions. This is not a new concern in the history of the study of numerical cognition. As detailed by Dos Santos (Reference Dos Santos2022), already Stevens (Reference Stevens1939) pointed out that specific terminology should be introduced for number-related concepts in the psychophysicist context. Davis and Pérusse (Reference Davis and Pérusse1988) asked for similar conceptual clarity in describing numerical competence in animals. Recently, both cognitive scientists (Núñez, Reference Núñez2017) and philosophers (De Cruz et al., Reference De Cruz and De Smedt2010; Dos Santos, Reference Dos Santos2022; Pantsar, Reference Pantsar2014, Reference Pantsar2021a) have emphasised the need for distinct terminology for numbers as used in mathematics and quantity notions in the context of non-mathematical capacities.

In this book, I use a particular conceptual distinction aimed at avoiding the problems just referred to. Here numerosity, as used by Gallistel, is a general term for quantities. Infants, non-human animals and adult humans all observe their environments in terms of numerosities. This is what the behavioural and electrophysiological data referred to by Gallistel (Reference Gallistel2018) strongly establishes. Numbers are a specific type of numerosity. They form the abstract subject matter for arithmetic (in case of natural numbers), as well as other fields of mathematics (in case of calculus, complex analysis, etc.). They can be referred to by numeral symbols (![]() , etc.) or by numeral words (one, two, drei, vier, cinque, etc.). In the brain, they are represented by number concepts (ONE, TWO, ONE THIRD, SQUARE ROOT OF TWO, etc.).

, etc.) or by numeral words (one, two, drei, vier, cinque, etc.). In the brain, they are represented by number concepts (ONE, TWO, ONE THIRD, SQUARE ROOT OF TWO, etc.).

In this book, the subject matter is the arithmetic of natural numbers ![]() In mathematics, sometimes the number 0 is included in the natural numbers but sometimes it is not. When this distinction is important, it will be noted, but mostly we will be concerned with the set of positive integers, thus not including zero. The infinite set of natural numbers in mathematics is referred to by the symbol

In mathematics, sometimes the number 0 is included in the natural numbers but sometimes it is not. When this distinction is important, it will be noted, but mostly we will be concerned with the set of positive integers, thus not including zero. The infinite set of natural numbers in mathematics is referred to by the symbol ![]() . Natural numbers can be used both for counting (one, two, three, …) and ordering (first, second, third, …). In the first case, we speak of cardinal numbers. In the second case, we speak of ordinal numbers. Cardinal and ordinal numbers have very different properties when considering infinite sets, but for finite sets we can switch from one to another: the cardinal number four refers to the fourth ordinal number on the counting list and so on (this in case that natural numbers are considered to begin from

. Natural numbers can be used both for counting (one, two, three, …) and ordering (first, second, third, …). In the first case, we speak of cardinal numbers. In the second case, we speak of ordinal numbers. Cardinal and ordinal numbers have very different properties when considering infinite sets, but for finite sets we can switch from one to another: the cardinal number four refers to the fourth ordinal number on the counting list and so on (this in case that natural numbers are considered to begin from ![]() ). Therefore, each non-zero natural number is connected in most languages to two numeral words. As for numeral symbols, practices vary across languages. In English, it is common in some contexts to use Roman numeral symbols to refer to ordinal numbers (e.g., Elizabeth II, Super Bowl LVI, Godfather III). Indo-Arabic numeral symbols are used both for cardinal numbers and ordinal numbers, with ordinality expressed by either a dot or another suffix (e.g., 9th) after the numeral symbol.Footnote 11

). Therefore, each non-zero natural number is connected in most languages to two numeral words. As for numeral symbols, practices vary across languages. In English, it is common in some contexts to use Roman numeral symbols to refer to ordinal numbers (e.g., Elizabeth II, Super Bowl LVI, Godfather III). Indo-Arabic numeral symbols are used both for cardinal numbers and ordinal numbers, with ordinality expressed by either a dot or another suffix (e.g., 9th) after the numeral symbol.Footnote 11

It is important to make the distinction between numbers, number concepts, numeral words and numeral symbols, as well as that between the cardinal and ordinal interpretation of natural numbers. While these distinctions are generally accepted, I believe that it is equally important to make similar distinctions when discussing the processing and manipulation of numbers and numerosities. With such distinctions in place, many confusions can be resolved. What goes wrong, for example, in Wynn’s ascription of cognitive abilities to explain infant behaviour? As I understand it, the problem is at least partly rooted in the terminology and the conceptual distinctions that it reflects. The writings about ‘infant arithmetic’ and ‘animal arithmetic’ create an accepted use of language in which any treatment of quantitative information is called arithmetic. But this kind of usage is almost certain to run into ambiguity and downright confusion. Certainly, there is no reason to think that researchers like Wynn and Dehaene want to equate the infant or animal abilities with the arithmetical ability of mature humans. But, nevertheless, they choose to write about both abilities as ‘arithmetic’.

Here I want to be emphatic about taking a different approach. Arithmetic, according to the best current knowledge, is exclusively the domain of sufficiently mature human subjects.Footnote 12 It involves an extensive grasp of exact number concepts and well-defined operations on them. Thus, arithmetic – to the best of our current knowledge – requires linguistic ability and is made possible in the individual development through processes of enculturation (Fabry, Reference Fabry2020; Fabry & Pantsar, Reference Fabry and Pantsar2021; Menary, Reference Menary2015; Pantsar, Reference Pantsar2014, Reference Pantsar2018a, Reference Pantsar2019b, Reference Pantsar2020). Once we understand arithmetic in this sense, it is much easier to take stock of the different types of quantitative abilities. Formal arithmetic is what advanced and expert mathematicians are able to do. That includes proving arithmetical theorems and other knowledge and skills not shared generally by humans. But almost all sufficiently mature humans growing up in arithmetical cultures have some arithmetical knowledge.Footnote 13 They can count items and conduct basic arithmetical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. They can do this with the help of cognitive tools like pen and paper and the abacus, but most of them can also do mental arithmetic, that is, carry out arithmetical operations for small numbers without using tools.

All those kinds of knowledge and skills are arithmetical, and none of them are possessed by non-human animals or infants. But there are also human cultures, such as the Amazonian peoples of Pirahã and Munduruku, in which none of those skills are generally possessed by their members – child or adult (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Everett, Fedorenko and Gibson2008; Gordon, Reference Gordon2004; Pica et al., Reference Pica, Lemer, Izard and Dehaene2004). Arithmetical abilities are thus present only in arithmetical cultures, and all other types of abilities with numerosities should be distinguished from them. I have suggested previously that the quantitative skills shown by anumeric cultures, non-human animals and human children before a certain developmental stage should be called proto-arithmetical (Pantsar, Reference Pantsar2014, Reference Pantsar2019b). Rafael Núñez has proposed the word ‘quantical’ to refer to roughly the same abilities (Núñez, Reference Núñez2017). I prefer the word ‘proto-arithmetical’, because it already points to an important claim that I defend throughout this book: that the evolutionarily developed quantitative abilities are the basis on which arithmetical ability develops.

With the distinction between proto-arithmetical and arithmetical in place, we can specify the important conceptual clarification between numbers and numerosities. Let us speak of ‘numbers’ only when discussing the referents of exact number concepts in the context of arithmetic or other mathematical areas, while using the word ‘numerosities’ in connection to proto-arithmetical abilities (De Cruz et al., Reference De Cruz and De Smedt2010; Pantsar, Reference Pantsar2018a). Finally, we need a term to distinguish numbers and numerosities, now connected to cognitive abilities, from the quantities that they represent or enable processing. Let us call these simply cardinalities. Importantly, cardinalities should be distinguished from cardinal numbers. One can get information about cardinality of a collection without possessing cardinal number concepts. For example, by matching each fork with a knife while setting a table, one can establish that the cardinality of the forks is the same as the cardinality of the knives. No knowledge of numbers is required. However, to establish that the cardinality of a collection is some natural number, one needs to possess (cardinal) number concepts.Footnote 14

At this point, we should also discuss the controversial issue of representations. As framed above, I take number concepts to be mental representations of numbers, which conforms to the standard use in the literature (see, e.g., Carey, Reference Carey2009). However, I will speak of representations also when discussing cognitive processes involving proto-arithmetical abilities. This has become controversial in the philosophy of cognition and mind in recent years. Proponents of (radical) enactivist cognition argue that representations are only present in the mind once there are linguistic truth-telling practices in place (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2017; Hutto & Myin, Reference Hutto and Myin2013, Reference Hutto and Myin2017; Zahidi, Reference Zahidi2021; Zahidi & Myin, Reference Zahidi, Myin, Etzelmüller and Christian2016). Since infants and non-human animals clearly do not have such practices, the radical enactivist account would denounce talk of numerosity representations in infant and non-human animal minds. Here I do not want to commit to any particular view about representations. I believe that the account I develop can be understood both in terms of radical enactivism and accounts that allow for non-linguistic representation (see Pantsar, Reference Pantsar2023c for a detailed treatment of this topic). Since a choice of terminology must be made, I have decided to talk about representations in a more general sense that could include, for example, visual representations or some kind of coding schemes. In any case, this should not be problematic since I have made the clear conceptual distinction between number concepts (which the radical enactivists would also accept as involving representations) and proto-arithmetical numerosity representations (which they would not).

Now that the key terminology is defined and the necessary conceptual analysis conducted, I believe that we are in a much better place to understand the kind of empirical data discussed by Wynn and Dehaene. The five-month-old babies do not have arithmetical knowledge. They do not possess number concepts, nor do they conduct arithmetical operations. But they do possess proto-arithmetical abilities with numerosities which enable them to get information about the cardinalities of collections of items. Just what are these abilities and how have they developed? How are they used in acquiring properly arithmetical abilities? These will be the topics of Chapter 1. But already we can see a way forward. Nothing about the experimental data of Wynn, for example, needs to be dismissed on the grounds of introducing new, coherent terminology. With the new conceptual framework in place, we only need to reinterpret the data. Perhaps some of the data needs to be ultimately rejected because it is revealed as problematic in the face of new data. But, as I will show, by combining philosophical conceptual analysis with data from empirical research, in most cases we get a better understanding of the cognitive phenomena involved.

I.3.3 A Project of Interdisciplinary Synthesis

In the manner described above, this book is a project of interdisciplinary synthesis in the research relevant to the development of arithmetical knowledge. While I also use a priori philosophical methodology, I am not committed to the position that arithmetical knowledge is a priori in character, let alone that arithmetical knowledge can be elucidated only through a priori methodology. In modern parlance, I am not a classic ‘armchair philosopher’. However, the kind of conceptual analysis I want to conduct here is not descriptive, in the sense that it ‘produce[s] a systematic account of the general conceptual structure of which our daily practice shows us to have a tacit and unconscious mastery’ (Strawson, Reference Strawson1992, p. 7). In referring to Strawson’s view, Somogy Varga writes that:

In the contemporary philosophical landscape, such a view of the tasks and methods of philosophical inquiry is becoming much less common, and major scientific fields of inquiry are now complemented by subdivisions of philosophy that specialize in investigating a range of questions pertinent to the subject matter. The success of cognitive science has surely been a motivating factor for philosophers to account for new findings and to adjust their theories, topics, and approaches. Philosophers investigating the mind now often draw on findings in the sciences of the mind, reaching conclusions based on empirically informed reflection instead of a priori methods.

While Varga writes in this passage about the philosophy of mind, I can wholeheartedly agree with his views when it comes to the epistemology of arithmetic. That is why I refer in this book to a vast array of studies in the cognitive sciences, from animal behaviour to cognitive neuroscience. This is crucial for achieving true progress in determining how arithmetical knowledge has developed. Yet this focus on empirical studies of cognition does not mean that more ‘traditional’ philosophical research does not play an important role in my methodology. Conceptual analysis and other philosophical methods are crucial for developing an understanding of how empirical data should be interpreted and understood. One reason for this is that empirical data, while increasing both in quantity and quality, still tells us relatively little about the development of arithmetical knowledge. There are still large parts that must be filled in with conjectures and hypotheses, to be tested by further studies.

Another reason is that conceptual analysis can help us see logical or epistemological connections between concepts that may well turn out to indicate connections also in cognitive development. After all, as I will argue in detail in Part II of the book, one of my main tenets in this book is that arithmetic is a culturally developed phenomenon. The development of arithmetic is thus tied to the general cultural development of knowledge, in which arithmetic as a discipline has been connected to many other areas, including philosophy. The history of the development of arithmetic should be studied in tandem with the study of the cultures in which arithmetic has developed. What was the status of arithmetic in that particular culture? Who were taught arithmetic, and with what aims? What applications did arithmetic have? These, and many other questions, are important in explaining how different cultures have developed arithmetical knowledge. Thus, the interdisciplinary approach, in addition to philosophy and the cognitive sciences, should also include the history of mathematics, cultural anthropology, archaeology, as well as mathematics itself. Studies from all these disciplines will play an important role in this book.Footnote 15

But most of all, I believe that an interdisciplinary synthesis between philosophy and other disciplines is needed because it works. It is the way we can get the best possible understanding of the development of arithmetical knowledge. The task at hand, after all, is huge. If the state of the art is correct, the extent of our innate proto-arithmetical abilities is not significantly different from that possessed by a wide range of non-human animal species. But somehow from these origins we have managed to create incredibly complex arithmetical theories whose applications have transformed the world in which we live in fundamental ways. In order to explain this kind of development, all relevant and reliable data are welcome, regardless of the discipline. That, however, makes it all the more important that data from different fields are analysed and interpreted in a unified, coherent theoretical framework. I hope that this book will make a positive contribution to this development.

I.4 Structure of the Book

As already mentioned, this book is divided into three parts. Part I focuses on the ontogeny of arithmetical knowledge. In Chapter 1, I explain the evolutionarily developed proto-arithmetical abilities for processing numerosities that humans already possess as infants and share with many non-human animals. These abilities (subitising, estimating) are then contrasted with proper arithmetical abilities. In addition to presenting the empirical data that establish the existence of proto-arithmetical abilities, the purpose of the chapter is to make clear that there is an important distinction between these evolved abilities and proper arithmetic of natural numbers.

Chapter 2 is about the way number concepts are acquired on the basis of proto-arithmetical abilities. First, a distinction is made between different types of abilities (conceptual, pre-conceptual) with numerosities. Then three prominent accounts in the empirical literature are discussed in detail: nativism, Dehaene’s (Reference Dehaene2011) ‘number sense’ and Carey’s (Reference Carey2009) bootstrapping account. The bootstrapping account is deemed as the best way forward and it is then analysed in detail in light of critical views presented in the literature.

In Chapters 1 and 2, it is established that proto-arithmetical abilities should not be confused with acquiring number concepts and arithmetical abilities. The latter, rather than being of evolutionary origin, demand cultural learning. In Chapter 3, the framework of enculturation as proposed by Menary (Reference Menary2015) and others is presented in order to formulate a theory of number concept acquisition that is sensitive to both biological and cultural factors. This theory is then expanded to arithmetical skills and knowledge. The details of the enculturation framework are analysed carefully, including its neuronal realisation (i.e., neuronal recycling vs. neural reuse). Finally, empirical predictions of the enculturation account are formulated and discussed.

In Part II, the focus switches to phylogeny and cultural history; the way human abilities have evolved biologically and developed culturally. In Chapter 4, I move the analysis from the individual level to the phylogeny and cultural history of numbers and arithmetic on a cultural level. How do number concepts develop within cultures? I start from the following challenge posed by, among others, Pelland (Reference Pelland and Bangu2018): how could numerals emerge without there first being number concepts, as suggested by the enculturation account? I will explore the framework of material engagement of Malafouris (Reference Malafouris2013) as a possible answer to this, based on recent anthropological data. Then I discuss the best current knowledge on the cultural development of numeral systems, from the point of view of both historical and ethnographical studies. Finally, I will detail a theory, influenced by the ones presented by Wiese (Reference Wiese2007) and dos Santos (Reference Dos Santos2021), that numerals and number concepts have co-evolved through material engagement. I argue that this theory is consistent with the enculturation framework as it applies to ontogeny.

While Chapter 4 focuses on number concepts, in Chapter 5 the approach is extended to the cultural history of arithmetical skills. These range from basic arithmetic (addition, multiplication) to formal systems of arithmetic and infinity. The role of cognitive tools (writing systems, abacus, etc.), cognitive practices (e.g., enumeration, finger counting) and applications (bookkeeping, trade, agriculture, etc.) are discussed. It is shown that all stages of the development of arithmetic can be explained in the present approach.

In Chapter 6, a theoretical framework for this approach is detailed, based on accounts of cumulative cultural evolution as proposed by Henrich (Reference Henrich2015), Heyes (Reference Heyes2018), Boyd and Richerson (Reference Boyd and Richerson1985, Reference Boyd and Richerson2005), and others. In incremental steps across generations, I will show, number concepts and arithmetical operations came to be through cultural learning. In virtue of the creativity and innovation of individuals and groups, as well as communication with other cultures, these developments may take new paths. Results from anthropology, ethnography and the history of mathematics are presented to support this account. Finally, the relation between enculturation (in ontogeny) and cumulative cultural evolution (in phylogeny and cultural history) is discussed, showing that these two accounts can be combined into one coherent theoretical framework.

Finally, in Part III, the considerations on arithmetical knowledge developed in Parts I and II are discussed in connection to the literature in the philosophy of mathematics. In Chapter 7, the topic is the epistemological importance of the first two parts of the book. First, the potential threat of conventionalism is discussed. I defend the view that the proto-arithmetical origins determine the trajectory of the development of arithmetical knowledge to a sufficiently strong degree to contradict strict forms of conventionalism. Nevertheless, conventions (e.g., symbols, words, practices) are important for both the ontogenetic and historical development of arithmetic. This is discussed also in terms of Wittgenstein’s philosophy of mathematics, which has received different interpretations in the literature. Finally, I will argue that arithmetical knowledge, as described in Chapters 1–7 of this book, is best described as being maximally inter-subjective, that is, basic arithmetical knowledge is shared in a highly similar manner by most phenotypical members of all arithmetical cultures.

In Chapter 8, the account of arithmetical knowledge I have developed is analysed in terms of the classical characteristics of mathematical knowledge as described in traditional philosophy of mathematics: apriority, objectivity, necessity and universality. I show that each of these can be saved in my account in a sufficiently strong sense. Apriority should be interpreted as contextual apriority; the context being set by our proto-arithmetical abilities and their enculturated development. Objectivity should be understood as maximal inter-subjectivity, as detailed in Chapter 7. The necessity of arithmetic needs to be seen as the impossibility of strongly deviant arithmetical knowledge in arithmetical cultures. And finally, the universality of arithmetical knowledge should be understood as universality of arithmetic for phenotypical members of arithmetical cultures. For each notion, I will argue in detail how the adjusted interpretation is strong enough to save what is generally seen as being essential to arithmetical knowledge.