Introduction

According to Polish guidelines futile therapy refers to medical interventions that artificially maintain organ function in patients without a realistic prospect of achieving goals of care. Such practice prolongs patients’ suffering without any benefit and is widely considered a medical and ethical error (Kübler et al. Reference Kübler, Siewiera and Durek2014). However, Poland is characterized by particularly low incidence of life-sustaining treatment limitations compared to other European countries (Guidet et al. Reference Guidet, de Lange and Boumendil2020; Wernly et al. Reference Wernly, Rezar and Flaatten2022). The precise opinions and sentiments of Polish intensive care clinicians regarding end-of-life and futile care remain unknown.

The main aim of the study was to conduct the questionnaire study to evaluate the approach of Polish medical personnel to the problem of futile treatment in the ICUs.

Materials and methods

The electronic questionnaire was administered to participants of the intensive care conference ‘Forum Intensywnej Terapii’ held in April 2023. The congress gathered clinicians practicing intensive care across the whole country. Roughly 700 participants participated in the conference. The questionnaire consisted of 10 questions regarding goals of care, communication between physicians and patients or patients’ families, futile treatment protocol, as well as baseline data (country, region, gender, specialty, work experience, type of hospital).

The results were collected anonymously. The statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS version 29. The chi-squared test was conducted when comparing the responses between respondents with shorter (<10 years) and longer (>10 years) work experience. P-value of 0.05 was considered a threshold for statistical significance. In post-hoc assessments, residual analysis was used with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison adjustment.

Results

Overall, 354 questionnaires were collected, corresponding to a response rate of approximately 50%. The detailed breakdown of participants’ characteristics is summarized in Table 1. We present questions asked in Table 2.

Table 1. Demographic data of patients

Table 2. Questions asked in the questionnaire study

1 Multiple choice possible

Question 1. In your opinion, should we talk to patients about end-of-life care and futile treatment?

The vast majority (98.5% of respondents) stated that talking to patients about goals of care/futile treatment is important in practice, with less than 2% thinking otherwise (Table 3).

Table 3. Responses to Question 1: In your opinion, should we talk to patients about end-of-life care and futile treatment?

Question 2. Assuming that the diagnosis is known, when is the optimal time to discuss goals of care with patients?

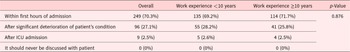

About 70.3% of respondents believed that patients should be talked to about goals of care immediately after hospital admission, with further 27.1% pointing to significant deterioration of patient’s condition and only 2.5% indicated such discussion should happen only after ICU admission (Table 4).

Table 4. Responses to Question 2: Assuming that the diagnosis is known, when is the optimal time to discuss goals of care with patients?

Question 3. What should be the balance of decision-making authority regarding treatment limitations between family and medical personnel?

About 81.6% of respondents believed that medical personnel should have more influence than family members when undertaking end-of-life care decisions (Table 5).

Table 5. Responses to Question 3: What should be the balance of decision-making authority regarding treatment limitations between family and medical personnel?

Question 4. Do you find it difficult to discuss futile treatment with the patient, even if you consider it important?

Question 5. Do you find it difficult to discuss futile treatment with the patient’s family, even if you consider it important?

51.2% of participants reported discomfort when discussing end-of-life care topics with patients while 48.8% had difficulty talking to their families, Respondents with longer work experience significantly more frequently reported having no difficulties (Tables 6 and 7].

Table 6. Responses to Question 4: Do you find it difficult to discuss futile treatment with the patient, even if you consider it important?

a Significant differences found in residual analysis.

Table 7. Responses to Question 5: Do you find it difficult to discuss futile treatment with the patient’s family, even if you consider it important?

a Significant differences found in residual analysis.

Question 6. Are you familiar with the protocol and guidelines on limiting futile treatment, introduced in 2014 by prof. Kubler’s team and recommended by the Polish Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care?

81.2% were aware of futile treatment protocol, however only 35.3% used it regularly. Residual analysis revealed that respondents with shorter work experience significantly more often admitted not knowing about the protocol (Table 8).

Table 8. Responses to Question 6: Are you familiar with the protocol and guidelines on limiting futile treatment, introduced in 2014 by prof. Kubler’s team and recommended by the Polish Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care?

a Significant differences found in residual analysis.

Question 7. What could be the reasons for not adhering to the guidelines and the futile treatment protocol? (multiple choice question)

Fear of legal consequences (61.9%), fear of family reactions (55.6%) and lack of proper knowledge (39.3%) were the leading causes for protocol implementation hesitancy. The participants with shorter work experience were significantly more likely to point to lack of knowledge and time constraints (Table 9).

Table 9. Responses to Question 7: What could be the reasons for not adhering to the guidelines and the futile treatment protocol?

Question 8. In your opinion, which initiatives could expand clinicians’ knowledge about futile treatment? (multiple choice question)

Implementation of the futile therapy protocol as a standard hospital procedure and its legal recognition were most frequently indicated as possible means of increasing the physicians’ knowledge of the existing protocol. Respondents with shorter work experience more frequently pointed to usefulness of internal courses in the ICU and discussions at medical conferences (Table 10).

Table 10. Responses to Question 8: In your opinion, which initiatives could expand clinicians’ knowledge about futile treatment?

Question 9. Have you talked more often to patients and/or their families about futile therapy since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland (March 2020)?

Question 10. Have you used the futile treatment protocol more frequently since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland (March 2020)?

Most respondents reported no change in the frequency of discussing goals of care or implementing protocol after COVID-19 pandemic; however, roughly 30% admitted to doing so somewhat or significantly more often [Table 11; Table 12].

Table 11. Responses to Question 9: Have you talked more often to patients and/or their families about futile therapy since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland (March 2020)?

a Statistically significant difference found in residual analysis.

Table 12. Responses to Question 10: Have you used the futile treatment protocol more frequently since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland (March 2020)?

a Statistically significant difference found in residual analysis.

Discussion

The topic of futile treatment is a contentious issue that has recently gained increasing recognition among healthcare professionals. According to the literature, approximately 80–90% of ICU physicians have already practiced withholding or withdrawing therapy (Cardoso et al. Reference Cardoso, Fonseca and Pereira2003; Giannini et al. Reference Giannini, Pessina and Tacchi2003; Kübler et al. Reference Kübler, Adamik and Lipinska-Gediga2011). Our respondents widely acknowledged the importance of discussing futile treatment with patients and their relatives.

However, many clinicians admit administering or witnessing futile treatment for a variety of reasons (Huynh et al. Reference Huynh, Kleerup and Wiley2013). Several guidelines regarding adequate end-of-life care in ICUs have been introduced to support physicians facing ethical dilemmas (Kesecioglu et al. Reference Kesecioglu, Rusinova and Alampi2024). Polish guidelines recommend implementing a protocol for documenting decisions on withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining therapies, while ensuring the continuation of palliative and comfort care. (Kübler et al. Reference Kübler, Siewiera and Durek2014).

Recently, considerable attention has been devoted in the Polish medical community to the issue of perceived overzealous treatment, futile care or end-of-life care. These terms are sometimes (and potentially inappropriately) used interchangeably. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused renewed discussion regarding these phenomena as well as the implications of limited ICU resources (Zadi et al. Reference Zadi, Tavani and Behshid2024). Poland participated in both Very Old Intensive Patients studies, which addressed limitations of treatment (Flaatten et al. Reference Flaatten, De Lange and Morandi2017; Guidet et al. Reference Guidet, de Lange and Boumendil2020). Several national conferences held panels dedicated to the topic of futile treatment. This issue has been also explored by experts in other populations, including pediatric ICU patients (Bartkowska-Śniatkowska et al. Reference Bartkowska-Śniatkowska, Byrska-Maciejasz and Cettler2021) and patients in internal medicine wards (Szczeklik et al. Reference Szczeklik, Krajnik and Pawlikowski2023). The recent novelization of the Polish Code of Medical Ethics introduced a new paragraph specifically prohibiting futile treatment (Alichniewicz and Alichniewicz Reference Alichniewicz and Alichniewicz2024).

Despite those efforts, there is still much to be learned and done. Several studies identified Poland as a country with comparatively low prevalence of treatment limitations (including withdrawal and withholding). In a multicenter study of older patients in the European ICUs, 19.8% older patients in Poland were subjected to some form of treatment limitation compared to 34.4% in the overall European sample (Guidet et al. Reference Guidet, de Lange and Boumendil2020). Polish clinicians limit life-sustaining treatment less frequently than their Scandinavian counterparts (Siewiera et al. Reference Siewiera, Tomaszewski and Piechocki2019). Our survey supports this observation: although most clinicians were aware of the protocol and recognized its importance, they admitted to never or only rarely using it.

Our study attempted to identify barriers to implementing the existing professional protocol. The most frequently reported obstacle was the fear of legal consequences. In a survey of Polish nurses, the fear of legal consequences was also a leading reason to continue what was perceived as futile therapy. (Damps et al. Reference Damps, Gajda and Stołtny2022). This sentiment is understandable, as futile treatment is virtually absent from the Polish legal framework. Although numerous legal experts believe that the Polish law does support limitations of futile treatment, this is never explicitly stated in the Polish legal documents (Szeroczyńska Reference Szeroczyńska2013). Moreover, Poland lacks a ‘no-fault’ rule, and a physician suspected of medical error can be prosecuted based on the Penal Code (Bargiel and Sułkowski Reference Bargiel and Sułkowski2023). Introducing an act of law dedicated to the issue, similarly to the German and French solutions (Graw et al. Reference Graw, Spies and Wernecke2012; Lesieur et al. Reference Lesieur, Leloup and Gonzalez2015), might significantly improve clinicians’ confidence when approaching end-of-life care ethical problems, especially the issue of futile treatment. The impact of legal frameworks on ethical decision-making in ICUs has been emphasized in European guidelines on limitations of treatment in the ICUs (Kesecioglu et al. Reference Kesecioglu, Rusinova and Alampi2024).

Another major factor highlighted by respondents was fear of the patient’s family objections. This is less modifiable but aligns with findings from other surveys. More than half of Polish nurses reported fear of being accused of malpractice by a patient’s family as a reason for continuing futile treatment (Damps et al. Reference Damps, Gajda and Stołtny2022). It is worth noting that, in addition to proper legislation and hospital procedures, effective communication with family along with psychosocial and spiritual support, contributes to better cooperation and mutual understanding between the health care team and relatives during end-of-life discussions (Woźnica-Niesobska et al. Reference Woźnica-Niesobska, Goździk and Śmiechowicz2020). One study found out that prognostic communication, documentation of DNR orders and limitations of treatment, and social worker support positively influenced the deceased patients’ relatives’ satisfaction with ICU care (Chou et al. Reference Chou, Huang and Hu2022). At the same time, it is generally acknowledged that physicians are not obliged to follow relatives’ wishes in every case by prolonging treatment deemed futile and unethical (Szeroczyńska Reference Szeroczyńska2013). Such situations, however, may lead to conflicts arising from differing perceptions of what constitutes futility.

In our study, respondents with less work experience reported feeling less comfortable discussing end-of-life care with patients and their relatives and indicated that a lack of knowledge may underlie the non-implementation of the futile treatment protocol. This association between lower professional experience and greater difficulty in addressing futility is consistent with an American study, which found that intensive care fellows differed significantly from more experienced clinicians in their assessment of medical futility (Neville et al. Reference Neville, Wiley and Holmboe2015). Simultaneously a questionnaire study of Polish medical students found that even though most Polish students heard about futile treatment, only 39% could define it properly (Pełczyński et al. Reference Pełczyński, Karbowiak and Ziembicki2023). These findings along with our study point out the necessity of putting more focus on the topic of futile treatment in Polish medical education.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. The questionnaires were filled by voluntary respondents, which might increase the risk of omitting physicians who were not familiar with the concept of futile therapy or unwilling to state their opinion. Due to our questionnaire distribution method, it was not possible to calculate the exact response rate.

Conclusions

Even though there is significant awareness among Polish clinicians regarding futile treatment and end-of-life care/protocol in ICUs, there is still a significant room for improvement regarding knowledge of and implementation of guidelines for limitations of treatment in situations deemed futile, especially among clinicians with shorter work experience. Our study underlines the need for optimizing legal and formal frameworks allowing open and transparent discussion about different aspects of end-of-life care.

Acknowledgments

PP, WSz, and RJ formed study design and planned methodology. PP, WSz, RJ, and MF prepared the questionnaire. WSz and MF distributed the survey among the participants. PP conducted statistical analysis. PP and WS conducted a literature search and drafted the first version of the manuscript. The manuscript was revised by MF, WSz, and RJ. All authors accepted the final draft of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no actual, potential or perceived conflict of interest related to the study.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or non-profit sectors.