1. Introduction

Indonesia has a long history of changing government policy on customary land rights since independence, accompanied by academic polemics on the topic: the trends to ignore or respect the customary land rights of local people have appeared alternately. Since President Soeharto’s resignation in the late 1990s, the trend to uphold the customary land rights has become apparent at the national level, but the trend in the field does not always follow suit. This study draws on a literature survey on the historical process of the status of customary rights in the changing setting of Indonesian land and forestry since colonial times. It investigates the status of customary land rights in the field with a focus on a notorious case of land grabbing in Padang Island, Indonesia, which has drawn public attention since 2009, based on the authors’ repeated field works from October 2023 to August 2024.

2. Literature review: Historical process of customary land rights in Indonesia

2.1. Colonial law vs. adatrecht

When the Dutch colonial government attempted to change the ruling system in Indonesia from forced labour to a system based on free wage labour around the 1850s, the security of the land regime started to matter as a basis for inviting Dutch capital investments. The first such attempt was made by the 1854 Governing Regulation (Regeringsreglement),Footnote 1 which stipulated that “the land that local people (Inlanders) had cleared for their own use, or as the community pasture, or on another reasons belonged to the villages would not be disposed by the Governor General” as per Article 62 Clause 6. Also, Clause 5 stipulated that “any concession of land by the Governor General would never damage the rights of local people.”

Since then, the relation between European law as formal law and local customary law has emerged as one of the most critical issues for agrarian policy in Indonesia (van Vollenhoven, Reference van Vollenhoven1928; van Vollenhoven, Reference van Vollenhoven1932; Soepomo and Djokosutono, Reference Soepomo and Djokosutono1951; Soepomo and Djokosusumo, 1954; Hooker, Reference Hooker1978, pp. 111–126; Ball, Reference Ball1982, pp. 23–236; Burns, Reference Burns and Hooker1988, pp. 147–185; Henley and Davidson, Reference Henley, Davidson, Davidson and Henley2007, pp. 1–49) like many other developing countries (Hooker, Reference Hooker1988; Takeuchi, Reference Takeuchi2022): Europeans established their rights of ownership (eigendomsrecht) in Indonesia through the registration under Dutch law, whereas local people almost never went through such registration.

The Dutch colonial government started to systematically erode the communal customary land rights of the population under the Agrarian Decree of 1870 (Agrarisch Besluit),Footnote 2 which contained the declaration of state land (domein verklaring) principle that “any area of land would be considered as state land (domein van de staat) if a proof of property rights could not be provided”, which controlled the agrarian legal system conceptually. Also, the communal customary land right was weakened by the Land Clearing Ordinance of 1874 (Ontginning Ordinantie), Footnote 3 which required the people to obtain permission from the district head to clear land of less than one bouw (around 0.7 hectares), and in the case of land less than five bouws, to obtain the permit from the head of the local government, Regency, or its council (regentschap or regenschapsraad). Lacking such a permit means no right on land could be asserted, and the harvest was lost (Alkema, Reference Alkema1932, pp. 8–9). Since 1865, the Forestry Administration (Boschwezen) has basically followed these policies, strictly controlling customary forest clearing by local people. Because these permissions were granted to individuals and promoted the idea of inheritable individual landholding (erfelijk indvidueel grondbezit), it was quite difficult for local people, who traditionally held communal land, to obtain permits resulting in their criminalisation as trespassers (Mizuno et al., Reference Mizuno, Hasibuan, Masaaki and Asrofani2023, pp. 67–79). The Royal decree of 1885Footnote 4 promoted the conversion of communal holdings into the right of inheritable individual land upon approval by a three-fourths majority of village members (Alkema, Reference Alkema1932, p. 7). Under these legal settings, communal holdings were destined to be eroded during the colonial period. Meanwhile, most of the local people were not aware of the need to register the land, which made the majority of land rights held by them only customarily ruled and proven (Mizuno, Reference Mizuno and Umehara1991, pp. 272–87; van der Eng, Reference van der Eng, McCarthy and Robinson2016, pp. 227–44).

In the academia, van Vollenhoven denounced the violation of residents’ customary land rights by the state land declaration in his accusation against the “unjust century,” defending the customary law (adatrecht) (van Vollenhoven, Reference van Vollenhoven1932, pp. 3–28). He emphasised the importance of customary adat rights that were generally uncodified and a totally different system from European law (van Vollenhoven, Reference van Vollenhoven1918, pp. 3–14). He particularly formulated the beschikkingsrecht (right of avail) as customary communal rights of disposition, which he claimed can be seen throughout the country (van Vollenhoven, Reference van Vollenhoven1909, pp. 19–41; Reference van Vollenhoven1932, pp. 8–11). He proposed abolishing the principle of state land declaration that had sacrificed the customary law, respecting the evolution of customary land rights of local people, and opposed the imposition of Western law (van Vollenhoven, Reference van Vollenhoven1932, pp. 82–121).

On the other hand, the Utrecht school, including Nolst Trenite and Eduard Herman s’Jacob, argued that the necessity of van Vollenhohen’s contention of beschikkingsrecht gradually declined, in parallel to the existence of beschikkingsrecht in the real world being eroded. The state land principle that was based on the Netherlands’ sovereignty should be prioritised, and used for the investments. The adatrecht was an uncodified, vague concept, and cannot be regarded at the same level as state law. The adatrecht should be respected, but should be recognised for cultivated agricultural land and residential area (or the land that was cultivated continuously, and maintained for habitation). The other land, especially waste land that is public land, should be made use of by the government freely (Trenite, Reference Trenite1942, pp. 63–87; S’Jacob, Reference S’Jacob1945, pp. 288–290, 487–500).

However, towards the end of the colonial period, a renewed respect for customary law emerged among the local people rather than Dutch scholars. In 1928, an incident occurred when the Dutch colonial government attempted to implement the principle of state land declaration at the level of autonomous government; the indigenous customary communities around outer islands, such as Sumatra and Borneo, opposed the very idea of the domein verklaring, or state land declaration. In August 1933, the government sought to mitigate the polemic on the state domain by introducing a binary regulation on land systems at the level of autonomous government in which indigenous customary communities were generally ruled by the customary law, while on the other hand, the areas directly controlled by the colonial government were ruled by the principle of state land declaration (Departemen Kehutanan, 1986a, pp. 84–88).

2.2. Post-independence Basic Agrarian Act

After independence, the Basic Agrarian Act (Undang-undang Pokok Agraria, or BAA)Footnote 5 was enacted in 1960 as the base of the agrarian system for the Republik Indonesia, which, first of all, abolished the dualism of the colonial agrarian system between Western law for European people and indigenous customary law for Indonesian people. The abolishment included the principle of state land declaration. Then, the Act provided the basic rules for customary law. According to Article 5, customary law is valid on land, water, and overcast as long as it does not conflict with the interests of the nation and state, regulations, and laws in Indonesia. What van Vollenhoven contended as beschikkingsrecht was now recognised as hak ulayat under the Act as long as the rights of customary legal community (masyarakat hukum adat) are proven to still exist, in accordance with the interests of the nation and state, covering the local people’s relation with land, water, and overcast in Indonesia, in general. On the other hand, the Indonesian state was now thought of as a supreme body to control the whole land, water, and air, with the right to control (Hak Menguasai dari Negara). In this system, the land that is not owned by any individual or other party is decided as the target of the state right of direct land control (Hak Menguasai Langsung dari Negara), for which the state has the authority to grant concessions, including the long-term usufruct right or Hak Guna Usaha (HGU), which has been the basis of many of the recent developments of oil palm plantations (Harsono, Reference Harsono1997, pp. 130–310).

The Act also, in order to secure legal certainty, required the government to implement the land registration system, as a condition for publicising land transfers. But in reality, numerous ownership rights (hak milik) remained without registration as a result of the implementation of the 1960 Act, and were generally referred to as hak milik adat (ownership under customary rights) (Harsono, Reference Harsono1997, p. 291).

2.3. Soeharto’s authoritarian regime

Soekano’s government at that time attempted to implement land reform that aimed at redistributing land from landlords to sharecroppers (Utrecht, Reference Utrecht1969, pp. 71–88), but such an attempt failed because those land reform programmes were branded as leftist initiatives (Mortimore, Reference Mortimore1972, pp. 63–68). Further, during Soeharto’s authoritarian developmentalist regime, following the 1965 aborted coup and subsequent mass killings in 1965–1968, land issues became difficult to address publicly (Rachman, Reference Rachman2011, pp. 81–93; Lucus and Warren, Reference Lucus, Warren, Lucas and Warren2013, pp. 1–11).

However, at the forefront of the local scene, since the latter half of the 1970s, many land disputes started to be reported by local papers and magazines. The reports that analysed 66 cases of land disputes based on the reported information from 1978 to 1980 pointed out that the majority of these cases (40 cases out of 64 cases) involved disputes between the state (state agencies) and local people, with many cases (38 cased out of 64 cases) disputed on land rights (Mizuno, Reference Mizuno and Takigawa1982, pp. 167–68). An implication was that these lands were located on what was declared as state land. Mizuno observed that a variety of supporting sectors, including the mass media, academia, and military, were involved in these cases. However, at this stage, the Soeharto government remained indifferent to people’s demands (Mizuno, Reference Mizuno and Takigawa1982, pp. 177–181), mainly on the grounds that local disputants lacked land ownership certificate since they had not registered their land (Mizuno, Reference Mizuno and Umehara1991, pp. 294–8). The status of local people was particularly vulnerable when their land was targetted for the state projects.

In the forest areas, the Soeharto government enacted the Basic Forestry Act of 1967,Footnote 6 which stipulated that the government-designated forest area (Kawasan Hutan, or state forest) will be created based on the decision by the Ministry of Forestry (Art. 1(4)). The state can issue concessions such as the right of timber cutting (Hak Pengusahaan Hutan, HPH since 1967) (Departemen Kehutanan, 1986b, p. 11), or industrial forestation (Hak Pengusahaan Hutan Tanaman Industri, HTI since 1990Footnote 7 ) on the Kawasan Hutan, which is the state forest where no private property rights were thought to exist. Then, by the Forestry Act introduced in 1999, all people who used the area of the state forest were obliged to get a permit from the government, although around 64% of the Indonesian surface was designated as state forest at that time, where about 50 million people lived (Hakim et al. Reference Hakim, Wibowo, Ginoga, Cahyono, Cahyono, Hakim, Wibowo and Ginoga2018, pp. xxii–xxviii; Bachriadi, Reference Bachriadi2023, pp. 9–19; Mizuno, Masuda and Syahza, Reference Mizuno, Masuda, Syahza, Mizuno, Kozan and Gunawan2023, p. 48; Kusmana, Reference Kusmana2011, p. 3). This newly introduced permit system simply placed a large majority of people into an unstable status in terms of their lawful access to land and forestry (Suwrno and Harahap, Reference Suwarno and Harahap2025, pp. 167–172; Arizona and Illiyina, Reference Arizona and Illiyina2024, pp. 121–123).

2.4. Post Soeharto era

After President Soeharto’s resignation, reform movements became apparent in the field of agrarian rights. First of all, those who had felt deprived of their land rights during the Soeharto era started efforts to reclaim their own rights (Bachriadi and Lucas, Reference Bachriadi and Lucas2001). People claiming their customary community right of disposition (hak ulayat, or beschikkingsrecht) also started to regain their rights over communal land (tanah ulayat) (Sukirno, 2018, pp. 3–6).

According to Article 2 of the People’s Supreme Representative Assembly (MPR) Decree No. IX/MPR/2001 on Renewal of Agrarian Reform and the Management of Natural Resources, agrarian reform includes a continuous process of rearranging control, ownership, use and utilisation of agrarian resources, implemented in order to achieve legal certainty, protection, as well as justice and prosperity for all Indonesian people (Wiradi, Reference Wiradi2009, pp. 94–139). In this spirit, in 2012, the Supreme Constitutional Court rendered Decision No. 35/PUU-X/2012, which affirmed that the Customary Forests (Hutan Adat) are forests located in customary territories, and no longer are State Forests. This constitutional court decision strengthened the independent status of the Customary Forests, encouraging the local people residing in the forest areas to claim the customary community right of disposition (Hak Ulayat).

Accordingly, regarding the issue of overlap of land rights on the government-designated forest area (Kawasan Hutan, or state forest), the government issued Presidential Regulation No 88 Year 2017 concerning the Settlement of Land Control in the State Forest (Perpres 88/2017),Footnote 8 which stated that the people used the land for more than 20 years can apply for the programme of converting the area out of state forest with the change in boundary, while people had used the land for less than 20 years could apply for the programme of social forestry.

Here, we can recognise a tendency that people’s customary rights on land become increasingly respected by the government, Parliament, and judiciary. Such a trend seemed to be supported by the World Bank, which has emphasised customary land rights since the 1990s (Bruce et al., Reference Bruce, Giovarelli, Rolfes, Blerdsoe and Mitchell2006, pp. 139–142). This policy shift should have been reflected on the actual process of agrarian policy, including the settlement of agrarian conflicts. We will examine this through a case study of an agrarian conflict on Padang Island, Kepulauan Meranti district, Riau Province, Indonesia, in the next section.

2.5. Customary communal right Hak Ulayat and its proof

Local people in this case had claimed customary communal rights, hak ulayat, as their basis of livelihood. There are many studies on the nature of hak ulayat, in West Sumatra (von Benda-Beckmann, Reference von Benda-Beckmann1979; Fitria, Hasanah and Yalhan, Reference Fitria, Hasanah and Yalhan2024), North Sumatra (Ikhsan, Reference Ikhsan2021). Bali (Setiawan, Reference Setiawan2003), Baduy, West Java, (Arianto, Reference Arianto2015; Iskandar and Iskandar, Reference Iskandar and Iskandar2018), where the right-holder is usually a group of local people who are recognised as a customary legal community (Ardiansyah, 2018, pp. 31–66). The problem is the extreme difficulty in obtaining recognition of the status of the customary legal communityFootnote 9 to claim hak ulayat (Erwiningsih and Sailan, Reference Erwiningsih and Sailan2018, p. 36–75; Sukirno, 2018, pp. 44–227). Even with the support extended by experienced NGOs, the recognition process for hak ulayat often fails because of the gap between the notion held by the local people and the criteria set by the local government (van der Muur, Reference van der Muur2018, pp. 165–171).Footnote 10

On the other hand, the government started the National Agrarian Programme (Prona) in 1981 for land registration, which could not help avoid a clash with hak ulayat. According to Government Regulation No. 24 of 1997 on Land Registration,Footnote 11 of approximately 55 million parcels of privately owned land eligible for registration, only approximately 16.3 million parcels had been registered by then. In 2015, in the Middle Term Development Plan (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional, 2015–2019), different figures were reported such that the number of parcels to be registered amounted to 126 million (BAPPENAS, 2018, pp. 6–15). In 2017, National Agrarian Agency Ministerial Regulation No. 12/2017 on PTSL (Systematic and Complete Land Registration)Footnote 12 was issued and its progress was reported in August 2023 showing that the number of registered parcels that had been registered remained at 85.6 million (BAPPENAS, 2023, p. 14).

Although the registration of land has gradually increased, the remaining issue is that it does not cover the state forest. Many issues have arisen related to the land owned but not registered (meaning the land rights were certificated through customary ways) in the state forest. In outer Indonesia, for example in Sumatra, many people hold a document known as the SKT letter (Surat Keterangan Tanah, or land information letter) (Mizuno, Masuda and Syahza, Reference Mizuno, Masuda, Syahza, Mizuno, Kozan and Gunawan2023, pp. 25–26; Parlindungan, Reference Parlindungan1978, pp. 16–32), which functions as a proof of the customary land rights issued by village officers and/or village head (sometimes also by sub-district heads), and endorsed by the heads of neighbourhood organisations, RT and RW, as well as the owners of the land bordering the relevant land area (Mizuno, Masuda and Syahza, Reference Mizuno, Masuda, Syahza, Mizuno, Kozan and Gunawan2023, pp. 34–35; Afrizal and Elida, Reference Afrizal and Elida2024, pp. 3–7). However, under the formal law, as the SKT is only an initial proof of legal land rights and needs to be supported by a formal land certificate from BPN, the SKT is actually an insecure evidence of land rights lacking legal finality. People have been largely unsuccessful in defending their rights with SKTs in their contest against the palm oil expansion (Afrizal and Elida, Reference Afrizal and Elida2024, pp. 6–8). Moreover, in areas unilaterally designated as state forest (that includes the large parts of peatland area), the government repeatedly refrains from issuing SKT (Mizuno, Hosobuchi and Ratri, Reference Mizuno, Hosobuchi, Ratri, Osaki, Tsuji, Foead and Rieley2021, pp. 644–5), forcing local people to resort to customary ways to secure their land titles. But many such cases fail to secure recognition by the customary legal community, which has been the cause of many agrarian conflicts, even though academic studies have seldom addressed this problem (Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick, Davidson and Henley2007, pp. 139–145).

Therefore, this study intends to focus on the issues in these areas that are not secured under the recognition system for hak ulayat due to the overly strict conditions for its recognition. Indeed, a very few areas have been recognised as hak ulayat, as it often happens that many areas under customary rights of holding are included in the areas demarcated as state forests.

2.6. Land grabbing

In the following sections, we will describe a typical case of land grabbing. Land grabbing is a term often defined as “capturing control of relatively vast tracts of land and other natural resources through a variety of mechanisms that involve large-scale capital” (Borras et al., Reference Borras, Franco, Gómez, Kay and Spoor2012, p. 851). Many incidents of land grabbing have been reported throughout in Indonesia, particularly regarding land uses for biofuel production and food production (Borras and Franco, Reference Borras and Franco2012, pp. 39–44), as well as oil palm, rubber, timber, green grabbing, water grabbing, urbanisation, mining, and so on (Yang and He, Reference Yang and He2021, pp. 5–10). One of the most comprehensive studies is carried out by Deininger, et al. (Reference Deininger, Byerlee, Lindsay, Norton, Selod and Stickler2010). The study showed that land grabs have taken place largely in places where buyers could exploit corrupt or indebted governments with limited ability to regulate transaction or prevent buyers from targeting the poorest rural communities, expelling the people with non-traditional land title from their land (Borras et al., Reference Borras, Hall, Scoones, White and Wolford2011, p. 210).

Thus, Indonesia has been reported as one of the countries where land grabbing has taken place the most frequently (Yang and He, Reference Yang and He2021, p. 4). One of the largest cases is the MIFEE (Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate) programme, which covers a total area of 1.6 million hectares in the southeastern part of Indonesian Papua. Residents’ resistance movement against the MIFEE project emerged at both local and national levels after the national government launched the project in 2010. At the national level, about 30 organisations agreed to join forces in forming the Civil Society Coalition Against MIFEE (hereinafter referred to as the Coalition) to organise the resistance against MIFEE. This rapid protest movement succeeded in slowing down the project and forced the government to review it. The resistance peaked in 2012–2013 but declined afterwards. Some critical limitations faced by the resistance movement included the dependency of NGOs and grassroots organisations on international funding. This made the coalition vulnerable to the ebbs and flows of international trends, which certainly weakened the resistance after 2013 (Ginting and Espinosa, Reference Ginting and Espinosa2016, pp. 6–11). Since the oil palm plantations, jatropha (biofuel), REDD+ (or Reducing the Emission from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, plus carbon sequence from conservation, sustainable management of forest, and enhancement of forest carbon stock), as well as the expansion of oil and natural gas exploitation have been the serious causes of land grabbing in Indonesia, especially in the outer islands (McCarthy, Vel and Afiff, Reference McCarthy, Vel and Afiff2012, pp. 6–23). Capital accumulation occurred with the involvement of the government and its apparatuses through the provision of facilities and economic rent-seeking. It was evident in the case of ExxonMobil’s operation in the Cepu Block of Java, where the neoliberal state apparatus facilitated the interests of investors to control individual and public lands at the expense of local people (Bachriadi and Suryana, Reference Bachriadi and Suryana2016, pp. 580–9). This occurred through land disposition steps such as (1) regional zoning regulations; (2) land transfers from local people to the state; (3) land speculation activities; and (4) involvement of local government-owned enterprises in land acquisition. During these steps, people’s organisations that initially opposed the extension of the oil extraction operation in Cepu gradually changed their strategy as land transfer activities intensified, and the possibilities for private economic gains increased, becoming more accommodating to the activities of the oil company that utilised sub-contractor businesses and corporate philanthropic programmes to tame dissent (Bachriadi and Suryana, Reference Bachriadi and Suryana2016, pp. 582–8). Numerous similar cases have been reported to describe the dynamism of capital accumulation (Gellert, Reference Gellert and Shefner2015, pp. 72–90), as well as the following process of land acquisition, but they lack a clear investigation into the legal analysis on what kinds of land rights were held by local people, and how these titles were damaged/respected through the legal apparatus.

3. Case study: Padang Island, Kepulauan Meranti district, Riau Province

3.1. Introduction of Padang Island case

This paper deals with the aspect of land rights asserted in a particular agrarian conflict case in Padang Island, Kepulauan Meranti district, Riau Province, Indonesia, due to the land grabbing by the industrial reforestation of Acacia timber plantation covering a total of 40,125 hectares by PT. RAPP company This was based on the concession offered by the government in the area designated as state forestry. Padang Island is a typical site located inside the timber plantation granted as a concession in the state forest. Many local people have stayed in this area for a long before the concession, but the majority of the land they owned has not been formally registered. Though this is quite a typical case of land grabbing in Indonesia, not many studies have been conducted on the legal status of unregistered land held by local people in the state forest, particularly involving the concession to the industrial timber plantation.

In this land grabbing case, Salim provided a detailed chorological description, which was described as a case of “People who stood up for resistance and land grabbing with an entire community at Padan Island were finally defeated” (Salim, Reference Salim2013, pp. 110–118; Salim, Reference Salim2017, pp. 81–195). The capital of the company, RAPP, which has a strong influence on the central and local governments, security forces, and politicians, has far more financial and human resources than local people. Salim (Reference Salim2017, pp. 186–195) and Thorburn and Kull (Reference Thorburn and Kull2014, pp. 161–162, 166) contended the peculiarity of the Padang Island case in their discussion on four agrarian conflicts that have taken place almost simultaneously since 2009 in Kepulauan Meranti district, where peatlands cover almost all the area, and sago planting is the most suitable for the ecosystem. These cases exhibited varied sequences, among which the case of the Padang Island was the most intense, as the farmers’ union was quite active in organising people across the entire island. The other cases, such as the timber plantation case at Rangsang Island, did not see such intense protests of villagers as they lacked organisers; in the case of Tebin Tinggi Island, villagers of the timber plantation prioritised dialogue since 2012, even when a major fire took place in 2014, when local people were well organised until it finally led to the revocation of the concession to the timber plantation; and also in the case of sago plantation at Tebin Tinggi Island, after a major fire in 2014, the company was sued and agreed to pay the compensation for environmental damage.

Accordingly, this study will shed light on land rights, particularly customary land rights, to investigate the background factors of the Padang Island case and the question of how these land rights, as asserted by local people, were treated during the process of contest with the acacia timber plantation development on the land grabbing or illegal land acquisition conflicts. In the following sections, this paper will first present the characteristics of the study site and then investigate the process of land conflict, followed by a discussion and conclusion.

3.2. Characteristics of Padang Island

Padang Island is located in Kepulauan Meranti district. Kabupaten Kepualan Meranti (Meranti Islands District, Riau Province) was created in 2009 from Bengkalis district, Riau Province. The capital is Selat Panjang.

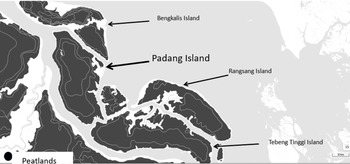

Most of the island is peatland, as shown in Figure 1, and peat swamp forests had covered the island for a long time.

Figure 1. Padang Island and the area of peatland (grey colour indicates peatlands)

(Source; BRGM)

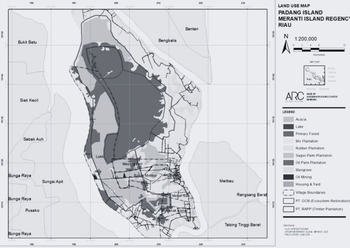

The island has an area of 1,109 km2, a population of 35, 224 (Andiko et. al., Reference Andiko, Siregar, Suhendri, Harmain, Zazali, Wawan, Sukendar and Hut2012, p. 12), and a population density of 31.7 persons per square kilometre in 2012. The island consists of two sub-districts. Merbau and Tasik Putri Puyu. The sub-district office of Merbau is located in Teluk Belitung, where there is a fishing port and a ferry terminal connecting the island to the rest of the country. The population of the Island comprises Melayu, Javanese, Bugis, Minangkabau, Batak, Chinese, and the Akit minority. Figure 2 shows the map of the island.

Figure 2. Map of Padang Island and the concession area held by PT RAPP

(Source; Authors made)

According to a survey of 228 households conducted in five villages (from October 2023 to November 2023 as mentioned later) as part of this research project, 136 households were headed by a Melayu, 75 households were headed by a Javanese, seven households were headed by a Batak, two households were each headed by an Akit and a Sundanese, and one household was each headed by a Banjar, an Acehnese, and a Buginese.

As for the industries of this island, the Panglong business or timber logging was active from the end of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century (Pastor, Reference Pastor1927, p. 6; van Anrooij, Reference van Anrooij1885, p. 307; Endert, Reference Endert1932, p. 786). Panglong consisted of logging, saw mill, and charcoal making business. The owners of the businesses stayed in Singapore and recruited Chinese labour from Malaysia and Singapore, and also Javanese from Java Island. Even today, many Javanese people assert that their ancestors came to the island in the 1910s–1930s, and there are also households where the ancestors came five generations ago. These businesses developed in Riau, and many islands between Riau and Singapore.

The residents’ livelihoods consist of agriculture, fishing, and commerce. Many inhabitants planted sago, rubber, and some oil palm. There are some dry sago powder making factories at Mekar Sari village and nearby areas. Today, with the favourable market price of sago, there is a shift from rubber to sago cultivation.

3.3. Field survey and data collection

Our research team conducted intermittent fieldwork from October 2023 to August 2024 at five villages of Padang Island, namely, Bagan Melibur, Lukit, Mekar Sari, Mayang Sari and Sungai Anak Kamal villages, all belonging to the Merbau sub-district. In October and November 2023, we first conducted a household survey of 228 households using a questionnaire concerning their origins, education, and occupation of household members, land holding both peatlands and non-peatlands, history of peatland fire, documents certifying land rights holding, production and sales of sago and rubber, income of households, and so on. We also conducted interviews with village heads/the village officers and residents including sago and rubber farmers/traders, dry sago powder making company’s managers, leaders of farmers groups (kelompok tani), heads of Village Deliberating Body (Badan Permusyawaratan Desa, or BPD), leaders of Riau Farmers’ Union (Serikat Tani Riau or STR), an informal leader of Akit community in five villages (all belonging to the Merbau sub-district). In addition, a supplemental survey was conducted in August 2024 by intensive interviewing with 10 households. Some of these households have retained their land within the industrial timber plantation concession by consistently refusing to sell it, while others have sold their land to the PT. RAPP.

3.4. Chronology of land grabbing in Padang Island

Based on the Forest Utilisation Consensus (Tata Guna Hutan Kesekapatan, TGHK) of 6 June 1986, Forestry Minister Decision No. 173/Kpts-II/1986Footnote 13 designated 4,686,075 hectares of Riau Province as state forest (Kawasan Hutan), including Padang Island. The area of the state forest on Padang Island amounted to 110,939 ha (Andiko et. al., Reference Andiko, Siregar, Suhendri, Harmain, Zazali, Wawan, Sukendar and Hut2012, p. 18), which means that almost all areas of Padang Island that correspond to 1,109 km2 were covered by state forest.

In February 1993, a private company PT. RAPP obtained the concession right of industrial forest plantation management (Hak Pengolahan Hutan Tanaman Industri, HPHTI) for approximately 300,000 hectares in four districts in Riau Province, namely, Siak, Pelalawan, Kampar, and Kuantan Sengini, by the Decision of the Ministry of Forestry No. SK 130/KPTS-II/1993.Footnote 14 In 1997, this area was somehow reduced to 159,500 hectares.

In 2004, however, it again increased to 235,140 hectares in the same four districts mentioned above. The company PT. RAPP attempted to further expand the area by obtaining letters of recommendation from the Governor of Riau Province and the head of Bengkalis district, while completing the environmental impact assessment (AMDAL) in preparation for further concessions (Salim, Reference Salim2017, pp. 108–110).

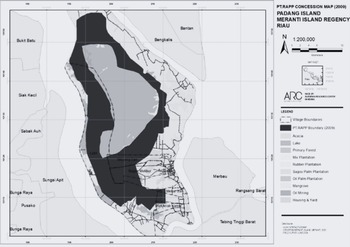

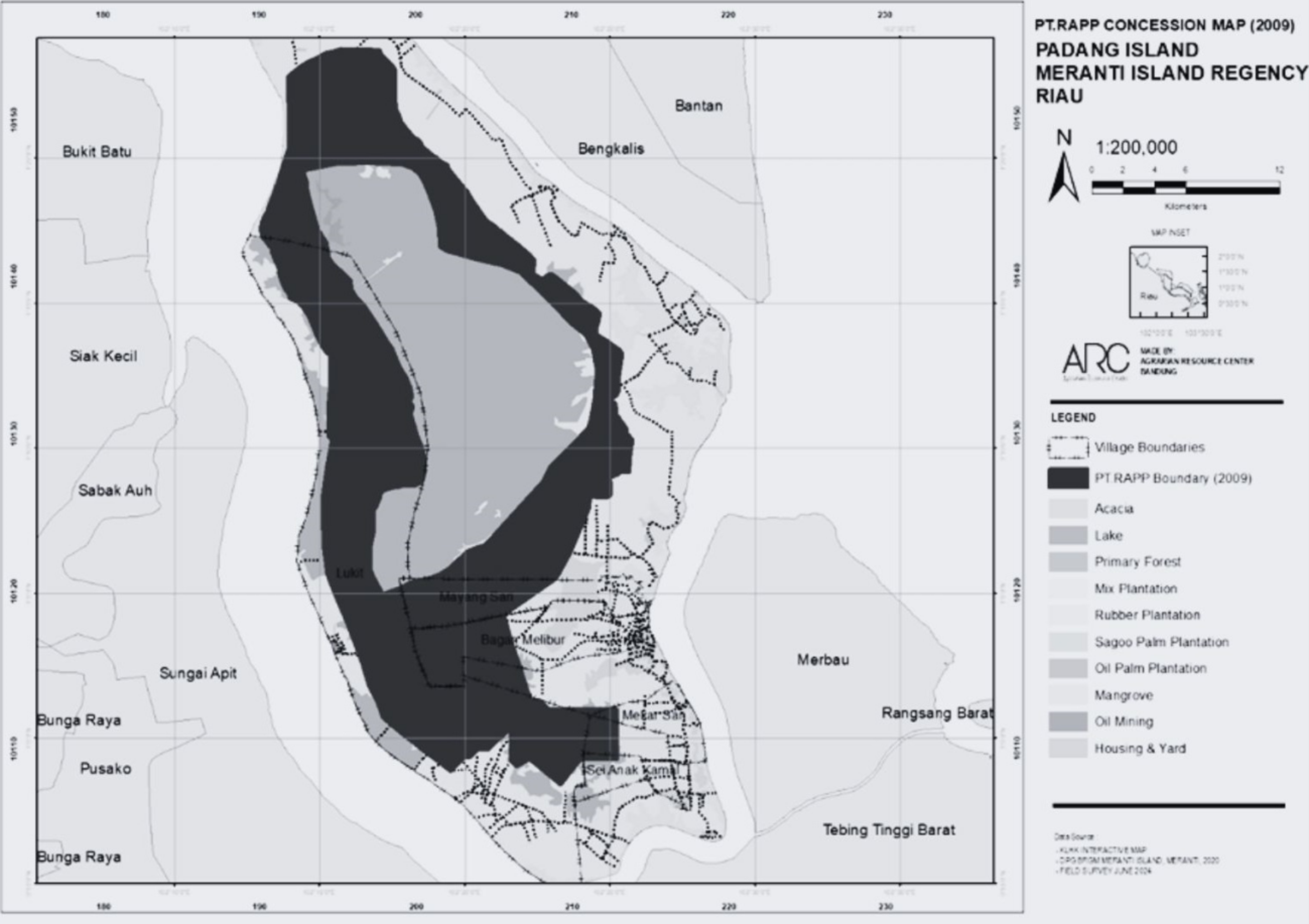

In June 2009, PT. RAPP obtained an additional concession right for industrial forest plantation for 350,165 hectares in five districts, including Bengkalis district, besides the four districts mentioned above. Under the Decision of the Minister of Forestry SK.327/MENHUT-II/2009,Footnote 15 Riau Province, it obtained a concession right for industrial timber plantation for 41,205 hectares in the Padang Island in Kepulauan Meranti district, which was separated from Bengkalis district on 16 January 2009. The area was classified as a limited production forest (HPT) in the state forest category. Figure 3 shows the concession area in black.

Figure 3. Map of Padang Island and the area of concession given to PT. RAPP (coloured black)

(Source; Authors made)

On 26 August 2009, the acting head of Kepulauan Meranti district sent a letter to the Ministry of Forestry to review the decision again.

Further, in September 2009, the farmers’ union Serikat Tani Riau (STR) was established among the villagers of Padang Island, with the participation of 15,000 persons at the peak of the activities.Footnote 16 Following its formation other farmers’ organisations, such as Serikat Tani Buruh (STB) emerged. On 30 December 2009, more than 1,000 residents of Padang Island gathered at the district’s office and conveyed their request to revoke the PT. RAPP’s concession for an industrial timber plantation in Padang Island. This meant a demand for the withdrawal of the Forestry Minister’s decision SK.327/MENHUT-II/2009. The residents of the islands of Teben Tinggi (in the case of an acacia plantation planned by PT Lestari Unggul Makmur or PT RUM) and Langsang (in the case of an acacia plantation planned by PT Sumatra Riang Lestari or PT SRL) in Kepulaun Meranti district also joined in this contest, each demanding the withdrawal of respective decisions by the Minister of Forestry. Then, the residents of these three islands together formed an alliance named Kepulauan Meranti District Environment Care Community Forum (Forum Masyarakat Peduli Lingkugan Kabupaten Kepulauan Meranti, FMPL-KM).

From January 2010 to December 2011, residents of Padang Island steadily continued their protests against the concession rights of PT. RAPP’s industrial timber plantation in front of the district head’s office in Serat Panjang, the Riau provincial governor’s office in Pekanbaru, and also the Ministry of Forestry in Jakarta, demanding the withdrawal of the 2009 decisions by the Minister of Forestry, and getting the company out of the island. Numerous NGOs and students from Riau Province also took action in support of the local people in various locations.

On 29 October 2010, the company held a briefing session inviting the protesting groups, including Padang Island’s residents, NGOs, and students, as well as the local council. During the meeting, residents demanded that the company show the results of the environmental impact assessment (AMDAL), but the company declined on the grounds that it was at the discretion of the government.

In November 2010, the Ministry of Forestry issued a statement that the company’s industrial forestation plantation is legal within the state forest area. To follow this, the head of Kepulauan Meranti district directed the heads of Kepuluan Meranti sub-districts to support the company’s activities.

In response, on 13 December 2010, people from almost all villages in Padang Island, including Lukit, Meranti Bunting, Pelantai, Mekar Sari, Teluk Belitung, Bagan Melibur, Mengkirau, and others, in total more than 1,300 people, held a joint prayer (ISTIGHOTSAH) at the Teluk Belitung Grand Mosque as a sign of protest.

Following this, on 20 December 2010, the head of the sub-district Merbau sent a letter to the village head of Tanjung Padang Village to oblige him to support all activities of the company.

Subsequently, the confrontation between the people and the government/company was intensified throughout the year 2011: on 27 March 2011, company’s attempts to bring heavy machinery onto the island were blocked by local people. On 25 April 2011, 46 residents’ representatives set up a tent at the entrance to the Minister of Forestry’s premises in Jakarta and began a hunger strike. On 28 April 2011, seven representatives of the residents met with Minister of Forestry Zulkifli Hasan. The Minister of Forestry was reported to have said, “The residents who come to Jakarta and go on hunger strike are not the original residents of Padang Island, there are no residents on Padang Island, you can demonstrate all you want, but if you obstruct us, we will also resist.” On 30 May 2011, after 900 local residents blocked the operation of PT. RAPP and returned home, a fire broke out at the company’s heavy machinery, and camps at company’s premises on the island. A total of 24 villagers were chased by the police; on 9 June 2011, three residents were arrested by the police. Residents protested. In response to the residents’ mass actions, the police eventually returned the three residents. Numerous shots were fired. On 1 November 1 2011, five people stitched their mouths at a mosque in front of the Provincial Assembly. Since then, residents have stitched their mouths in front of the office of the Riau Province Governor on consecutive days. On 27 December 27 2011, 5,000 residents of Padang Island occupied the Governor’s Office in Surat Panjang and stayed there for four nights and five days to protest against the Governor’s rejection of the people’s demand to send the recommendation letter to withdraw the Forestry Minister’s decision.

After all these confrontations, finally on 27 December 2011, the Mediation Team was appointed by the Minister of Forestry to deal with the local people’s demands, with the mandate to deal with the demand of the withdrawal of the Forest Ministrer’s decision, and the getting out of the company from the Padang Island, Kepulauan Meranti district, Riau Privince.Footnote 17 The team was entrusted to complete the mediation by the fourth week of January 2012.

Meditation Team’s report was submitted to the Minister of Forestry in January 2012, which showed two optional solutions for dispute resolution, together with a number of recommendations to mitigate the frictions, such as the issues of procedural fairness of negotiation for land transaction and the recognition of customary law. Its essence was as follows:

Solution A: To amend the 2009 Decision of the Minister of Forestry (No. 3227/Menhut-II/2009) to exclude the entire Padang Island from the concession.

Solution B: To amend the 2009 Forestry Ministerial Decision to reduce the area of industrial timber plantation within Padang Island.

In the option of Solution A, the government should prepare to negotiate compensation with the concession holders and consider the lawsuits in civil and administrative courts.

In the option of Solution B, the government should continue the mediation with the public and withdraw the concession from the overlapping land areas through participatory mapping. (Andiko et. al., Reference Andiko, Siregar, Suhendri, Harmain, Zazali, Wawan, Sukendar and Hut2012, pp. 19–93)

On 13 February 2013, the leaders of STR met with the managers of the company RAPP at Hotel Pangeran, Pekanbaru, and agreed on the conditions of reconciliation.Footnote 18 After this agreement, the protest movements by the villages reduced its intensity.

The Company supplied many programmes of scholarship, integrated agricultural training, agricultural inputs to farmers’ groups, health check for local people, and so on (Andiko et. al., Reference Andiko, Siregar, Suhendri, Harmain, Zazali, Wawan, Sukendar and Hut2012, p. 52).

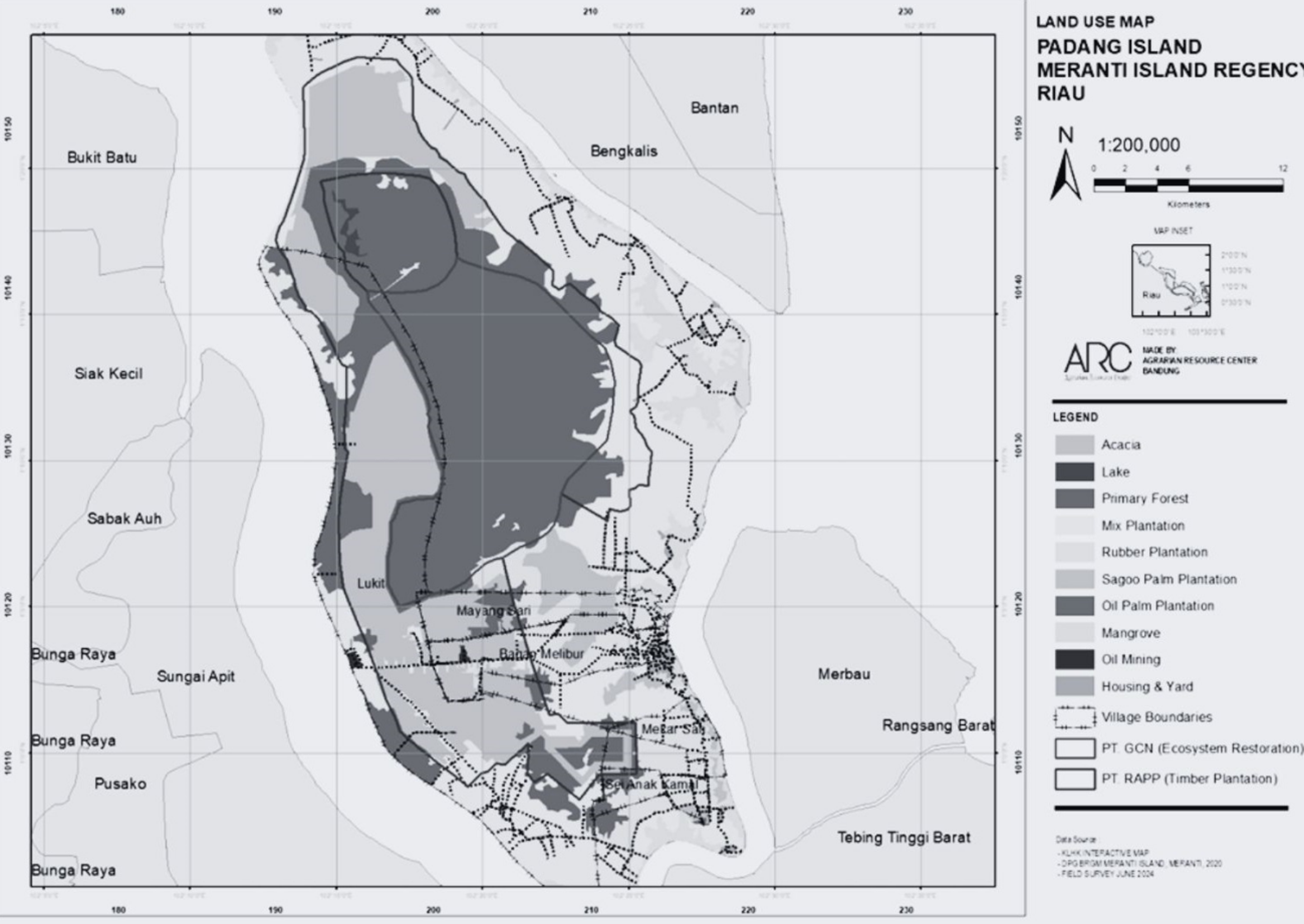

Finally, the Minister of Forestry issued Decision SK 180/Menut-II/2013 in April 2013, to reduce the concession area by approximately 6,000 hectares, which reduced the total concession area to 35,165 hectares (Salim, Reference Salim2017, pp. 162–163), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Map of Padang Island, and the area of concession given to PT. RAPP(coloured black) based on the Decision Letter SK180/Menhut-II/2013 of the Ministry of Forestry (Source: Authors made).

4. Customary land rights in the Padang Island case

4.1. Changing status under the formal law: State land to state forest

We may say that the Padang Island case was a partial triumph for local people in the sense that their movement finally changed the once rendered governmental decision for concession. However, we may also say it was a failure since it could not reform the legal status governing customary land rights under formal law, which is the fundamental cause of repeated land grabbing cases.

To understand the status of customary land rights, which the local people in Padang Island claim, we first need to have a quick historical review. Padang Island used to be a part of the Siak Sultanate, which started in the seventeenth century, and was prosperous in the eighteenth century, in the eras of Raja Alam who controlled the Senapelan (present Pekan Baru) around the 1760s and Sultan Ali who brought prosperity to the Siak Sultanate until 1821 (Barnard, Reference Barnard2003, pp. 55–173). Siak Sultanate came under the control of the Netherlands Indie Government in 1858 (Schadee, Reference Schadee1918, pp. 73–77). In 1906, Siak Sri Indrapura kept the status of an Autonomous Administration (Zelfbesturende Landschap), but Bengkalsi was under the direct control of the Dutch colonial government since 1873 (Schadee, Reference Schadee1918, pp. 67–68; Stibbe et al., Reference Stibbe, Wintgens and Uhlenbeck1919, pp. 143–49; Paulus, Reference Paulus1917, p. 268).

The land regime in the area of Autonomous Administration in Sumatra was principally kept under the customary land law, while the areas under the direct control of the Netherlands Indie were put under the State land declaration (Domein Verklaring) after 1874 (Paulus, Reference Paulus1917, pp. 21, 629).

Once domein verklaring was applied, the agrarian laws (Agararisch wet Footnote 19 /Agrarisch Besluit) of 1870 and the land clearing law (Ontginning ordinance) of 1874 were validated, meaning that people who wanted to clear forest were required to obtain permits from the government. In contrast to this, according to customary law, the permission of/acquaintance with the local chief or village head, for example, was enough (Pelzer, Reference Pelzer1978, pp. 66–85).

Padang Island was considered part of the Siak Sultanate, and after 1906, it became part of the Siak Sri Indrapur Autonomous Administration, not like Bengkalis Island. So, land law there was customary law. During 1858–1907, the Siak Sultanate lost its authority to levy new taxes, for example. The Siak Sultanate could not make decisions without the agreement of the Dutch colonial government (Schadee, Reference Schadee1918, pp. 73–81). But on the matter of local people’s land rights control, it was believed that the Island followed the customary law.

After independence, these conditions continued until the enactment of the Basic Agrarian Act of 1960 changed the legal framework as mentioned above. Now the people in Padang Island were required to formalise their customary land order as hak milik, or formal ownership under the Act. The situation further changed during the Soeharto era, especially in 1986 when the Ministry of Forestry issued the Ministerial Decision No. 173/Kpts-II/1986 on 6 June 1986 on the Forest Use Consensus (Tata Guna Hutan Kesepakatan, TGHK).Footnote 20 Under the TGHK, the government vigorously started designating areas of state forests (Kawasan hutan) totalling 8,964,075 hectares:Footnote 21 a significant percentage of the Riau Province’s total area of 9,456,160 hectares. In the TGHK, Padang Island, even though no detailed data was announced, according to the data referred to by the Minister of Forestry in 1999, the area designated as state forests at the Padang Island was 110,939 hectares (Salim, Reference Salim2017, p. 106; Andiko et. al., Reference Andiko, Siregar, Suhendri, Harmain, Zazali, Wawan, Sukendar and Hut2012, p. 18), which covered almost all areas of this island with a total area of 1,109 km2. This sudden designation as state forests (Kawasan Hutan) had a fundamental impact on the insecure status of customary land rights of the people on Padang Island.

Since the number of people on Padang Island has been limited,Footnote 22 its forestry resources have been a sufficient basis of livelihood for the local people. Being known as one of the most active locations of logging since the beginning of the twentieth century (Endert, Reference Endert1932, p. 786), it attracted a number of Javanese migrants to the island, while Malay and Akit people maintained the customary regime before the coming of the Javanese. As such, it is quite natural that local people considered themselves to have rights to the land and adhered to the prior legal system.

The area’s designation as state forest in 1986 enabled local people to keep their customary property rights (hak milik adat). This situation will be explained in further detail in Section 4.2.

4.2. Legal nature of the local people’s customary rights

During the process of the dispute resolution for the Padang Island case, one of the most critical points frequently debated was whether the protesters in Padang Island are the original inhabitants or mere migrants, which implies that the length requirement of land possession was considered as the basis of asserting customary land rights.

According to the survey conducted by the authors on Padang Island, it is clear that many who migrated to the island were Javanese but the migration occurred a long time ago during the colonial period. Among 228 households which we surveyed, 166 households answered that they were the original inhabitants (asli daerah, meaning they were locally born). While 60 households identified that their ancestors came from Java Island, 57 of these households have stayed on the island for generations, and 32 household heads said they are the third or subsequent generation of the Island. All of their ancestors cleared the land. One respondent reported to have inherited three parcels of land from his father, each measuring 2 hectares. His grandfather came from Pati, Central Java, in order to join his relative who was born on the island, but the grandfather of the relative came from Pati. The respondent knew the term Panglong and stated that the latter’s grandfather came to the island to log timber.Footnote 23 Overall, 168 respondents answered as born on the Island, out of which 85 identified as belonging to the third or later generation, and 18 identified themselves as the fifth or later generation (those people include the Javanese and non-Javanese).

Many people reported that they or their ancestors had cleared land collectively. A villager said he joined to clear the land collectively (secara kelompok) in 1998 with 390 other people. They cleared 780 hectares, and each person got 2 hectares of land. When they cleared the land, each person was paid 250,000 rupiah, partly because of hiring labourers to clear the land. The villager kept a letter of group landholding (surat kelopmpok) that was signed by the village head, and showed it to the authors. The letter listed the villagers who joined the collective clearing and the map of lands/parcels.Footnote 24 Another villager said they cleared the land in 1989 with 12 people in all. Each person got 2 hectares of land. The villager said there was a letter of group landholding.Footnote 25 A villager of Sungai Anak Kamal village said they cleared 6 hectares, and each person got 2 hectares, but if the member did not join the collective works (kerja bakti) three times consecutively, the land would return to the group.Footnote 26

In terms of land ownership status, among the 278 parcels of peatland and 33 parcels of non-peatland owned by respondents (total of 311 parcels of land), 142 parcels were obtained via inheritance and 111 parcels were acquired via purchase. Among them, 19 parcels were acquired by the local people before 1986, when almost the whole island was designated as state forest, and 171 parcels were acquired before 2009, when RAPP obtained the concession. The majority of the land inherited or purchased was previously owned by the local people who used to clear the land. This estimation is quite reasonable, since the island has been inhabited for generations, with the former generations having cleared, inherited, or sold the land until now.

Thus, we can conclude that the nature of land rights held by the local people in Padang Island, either original or migrated households, is characterised by the long-term continuous holding for many generations, which is said to be the hak milik adat or the customary ownership right, which is equivalent to ownership (hak milik) under the Basic Agrarian Act even though lacking formal registration.

4.3. Documentary evidence narrowed for customary land rights

Another critical issue debated during the process of mediation in the Padang Island case was whether the local people held the documentary evidence for the proof of land rights. The challenge was that several documents which local people regarded as proof of ownership were not recognised as legal documents in government practice. According to our survey in October-November 2023, we identified that, among the 461 land parcels (peatland 415 parcels, non-peatland 46 parcels) which claimed ownership, only 141 parcels held a formal land ownership title SHM (Sertifikat Hak Milik, or land ownership certificate). Others were different: namely, 169 parcels held the document known as SKT (Surat Keterangan Tanah mentioned above); 93 parcels held SKGR (Surat Keterangan Ganti Rugi, Letter of Compensation Statement, letter to prove the payment of land purchase, or transaction of land that is attached with SKTFootnote 27 ). Meanwhile 40 parcels held no formal documentation on land status, in which four parcels were located within the company’s concession; two parcels were organised with social forestry programme with SKPS (Surat Keputusan Perhutanan Sosial or social forestry certificate), two parcels with Surat Kelompok (certify the certificate of the land right owned collectively by those who joined the clearing the land as explained above) one parcel with Kwitansi (receipt, a letter made the time of transaction, singed by the seller and buyer of the land), and five with Surat Hibah (letter to certify the land given before the death).

Among these documents, only SHM and SKPS are considered as formal legal letters issued by National Agrarian Agency (BPN, Badan Pertanahan Nasional) for SHM and Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) for SKPS, while other letters are ignored in the government practice of cadaster survey because they lack the BPN’s or KLHK’s involvement.Footnote 28 This result is unjustifiable from the perspective of local people, since SKT and SKGR have the endorsement by the village head (lurah), or sometimes the head of the sub-district (camat), and have been deemed as due evidence of “hak milik adat.”

4.4. Discretionary procedure of state forest designation and HTI concessions

From the above discussion, it is clear that the land rights of local people in Padang Island have been proven in the local customary way and deemed as hak milik adat (property right without registration) based on the BAA of 1960 as explained earlier. It was only after the designation of state forests (Kawasan Hutan) in 1986 that these existing land rights suddenly became controversial. Did these existing rights automatically disappear after 1986, when the state forestry was unilaterally designated, or after 2009, when the HTI concession was given to the company? This is, after all, a question of superiority contest between state forestry on the basis of its concession and the people’s customary property rights (hak milik adat). The most critical question in this regard is the validity of the Forestry Law of Indonesia in 1999,Footnote 29 which automatically designates land as state forest if there is no registered title, without conducting any substantial survey on people’s rights on land before the designation of the state land (art.1, no. 4), and also in the issuance of the HTI concessions (art. 28), or by the Basic Forestry Act of 1967 and subsequent regulations as mentioned above. Such a discretionary procedure of designation deprives local people of any chance to access the information on the boundary of the state forests and the HTI concessions, which was the fundamental cause of friction in the Padang Island case (Andiko et. al., Reference Andiko, Siregar, Suhendri, Harmain, Zazali, Wawan, Sukendar and Hut2012, pp. 65–68).

4.5. Improvement of land transaction practices on customary land rights

One of the reasons why local people massively and continuously protested the advancement of PT. RAPP was that the transaction of land between local people and the company was not fair and transparent. At the first stage, many people who did not hold evidential documents of land title sold their land massively to the company at unfairly low prices (Andiko et. al., Reference Andiko, Siregar, Suhendri, Harmain, Zazali, Wawan, Sukendar and Hut2012, pp. 26, 65–66). A sense of anger spread among the local people once they realised the fraudulent nature of the land sales, and they feared that all of their land would be sold in this manner. Many people referred, in the authors’ interviews,Footnote 30 to the involvement of land mafia when the land was sold in a collective way, sometimes in collaboration with the village officers in letting them issue the fictive SKT document (Andiko et. al., Reference Andiko, Siregar, Suhendri, Harmain, Zazali, Wawan, Sukendar and Hut2012, pp. 65–66).

Therefore, the principles of “Free, Priority, Informed and Consent” in land transactions became a goal in their massive protest (Andiko et. al., Reference Andiko, Siregar, Suhendri, Harmain, Zazali, Wawan, Sukendar and Hut2012, p. 91). Especially since 2019, the village office has started to get involved in each transaction of land to ensure transparency. In this operation, first, the company was obliged to negotiate with the land owner. The payment from the company to the land owner is called Sagu Hati (benevolence), not the compensation (ganti rugi) because the company has not yet recognised the customary land rights of local people, although the Mediation team’s report recommended respecting the customary land rights (Andiko et. al., Reference Andiko, Siregar, Suhendri, Harmain, Zazali, Wawan, Sukendar and Hut2012, pp. 88–92). The amount of Sagu Hati varies depending on the condition of the land, such that if the land is vacant, or within the bush, the payment is 6 million rupiah; if the land is with planting such as rubber or sago palm, the payment is 9 million rupiah; if the land has productive planting, the payment is 12.5 million rupiah. This amount of payment was actually considered still too low for local people, given the standard of earnings. A rubber farmer who the authors interviewed has around 800 rubber trees in 2 hectares of land within the concession area, and collects the products of around 19 kg latex in every three days, which sells at the price around Rp.9000 per kg latex as of August 2024, which is equivalent to the monthly earning of 1.7 million rupiah per month, and 13.6 million rupiah per year (as his harvest period is 8 months in a year). Despite this, he was offered only 12.5 million rupiah per hectare by the company. He rejected the offer and claimed that he would reject the offer even if it were 50 million rupiah.Footnote 31 Another respondent had offered 300 million rupiah per hectare, although he finally accepted the offer of 15 million rupiah from the company.Footnote 32

Among the ten respondents interviewed who had owned land within the concession area, seven respondents reported that they had sold the land to the company, with prices ranging from 10 to 18 million rupiah, depending on negotiations. In the case of the highest payment (18 million rupiah), the negotiation took one year before an agreement was reached.

Once they agreed on the amount of payment per hectare, the land measurement was conducted by a joint team consisting of representatives from both the company and the village office. After this, the documents certifying land rights will be handed over to the company at the notary’s office located in Beton, Siak Indrapura district. Among the seven interviewed respondents who sold their land to the company, two had SKT letters, one had a SKSG letter, one had a surat kelompok (a letter of communal land clearing), while the other three lacked any letter. To certify these three cases, the village office issued the Sporadik letter, which has a similar function as SKT, which the village office often issues based on consensus among the village head, heads of neighbourhood organisations, RT and RW, persons who have bordering land, as well as the land holder. The transaction at the notary’s was usually photographically documented and the transportation costs to the notary were paid by the company.

Thus, our follow-up interviews identified visible changes in the company’s attitude towards transactions involving customary land rights and an active involvement by the local government. Both are considered to be positive consequences of the aforementioned mediation.

5. Discussion and conclusion

As reviewed in the beginning of this study, the policies on customary land rights of local people in Indonesia have gone through a historical path of change, and academia has also debated much on this topic intensively. Since 1870, when the Dutch colonial government established the legal framework on agrarian policy, customary land rights started to erode. But in the academia, Van Vollenhoven led the idea of beschikkingsrecht, right of avail, or customary communal right of self-disposition, and proposed to respect them. To this, the Utrecht school opposed and proposed to minimise the recognition of beschikkingsrecht based on the principle of state land declaration (Domen verklaring).

After independence, especially under the Basic Agrarian Act of 1960, it seemed the government abandoned the state land declaration principle, and recognised the customary rights, including the customary communal rights hak ulayat (beschikingsrecht). But the recognition of the hak ulayat was strictly limited as if following the idea of the Utrecht School. On the other hand, the local people continued to hold their land without formal registration (bezitrecht) as ownership (hak milik) under the Act, and as a result, the customary property rights (hak milik adat) covered almost the whole country.

During Soeharto’s authoritarian developmentalist administration, such unregistered land holdings were jeopardised by development projects, which neglected the customary land rights, lacking the legal documents for certification.

After President Soeharto’s resignation in 1998, many people stood up for the restoration of land, which they thought had been unjustifiably deprived during the Soeharto regime. Many political and judicial decisions have been rendered to settle the land conflicts, such as the decision of the Supreme Peoples’ Representative Assembly (MPR), and verdicts of the Supreme Constitutional Court, which pushed the government to change the policy orientation of the regulations towards a recognition of the customary land rights, including both hak milik adat or customary land ownership and hak ulayat or customary communal rights.

In order to observe the present status of historically changing land policies in Indonesia, this study has focused on the aftermath of a land grabbing conflict in Padang Island, Riau Province, which was the most intensive during 2009–2013, where the local people asserted their customary land rights against the industrial timber plantation operating under the government concession. The conflict was very messy in the first stage in 2009–2010, when the company refused to take any sincere response, and continued land collection at low prices by even involving the land mafia. This resulted in the mass mobilisation of local people, including mass meetings held in front of the district head office, or the Ministry of Forestry in Jakarta, and in the end, these protests prompted the government to take action by forming a Mediation team. The Mediation team proposed several options, including the cancellation or partial withdrawal of the concession to the company. As a result, the concession area was finally reduced from 41,205 hectares to 35,165 hectares.

The partial physical triumph in the Padang Island case was, however, legally insignificant in the sense it did not change the underlying legal framework that causes land grabbing in numerous similar cases. To examine the aftermath of this case, the authors conducted field surveys on Padang Island during October–November 2023 and August 2024. One of the critical findings was the duration of land possession, which was the central issue in conflict, as the minister repeatedly contended that the protesting people were migrants to the island, and not original inhabitants, implying that they lacked eligibility. The authors’ survey has shown that many Javanese have lived on the island since colonial times, for more than five generations, especially since the logger of the Panglong system at the beginning of the twentieth century. Many parcels have been inherited by the present generation. We may conclude that such a definitely long possession is the basis of hak milik adat, customary ownership, which is recognised under the formal legal regime authorised by the judicial interpretation of the Basic Agrarian Act.

Another critical finding was that the local people could not prove their rights by certain categories of documents even though they use them as the proof of land rights in the customary practice. Namely, many local people lacked the formally registered title document SHM for ownership hak milik, but instead presented the SKT certifying the customary property rights certified by the community including the village head, sometimes by the sub-district head, and heads of neighbourhood organisations, or the SKGR certifying the payment for the land purchase, but these documents were not accepted by the government and the company. But such an attitude is not justifiable when we consider the firm status of customary land regime in Padang Island throughout the historical process of changing land policies as we saw above. During the colonial times, when the island was under the Siak Sri Indrapura Autonomous Administration, the State Land declaration principle was not essentially implemented, and the matter of land rights control there followed the customary law. After independence, the customary law was dominant. The 1960 Basic Agrarian Act legalised the customary regime, under which people retained their customary property rights, hak milik adat, as well as hak ulayat, collective rights. It was only after 1986 that the abrupt designation of state forests (Kawasan Hutan) covered nearly the whole of Padang Island on the basis of concession. After the collapse of the Soeharto regime in 1998, the local people were allowed to contest such an unjustifiably discretionary designation of state forests, based on the documents that are valid under customary practice.

Actually, this is a contest between the customary legal regime and the formal statutory system. Even though an intensive confrontation ceased with the settlement of Mediation in 2013, the local people’s quiet contest continues. They have to engage in hard negotiations with the company for the land sale prices, by making use of the transparent procedures established by the Mediation team, as the company does not intend to pay anything more than a low-priced Sagu Hati (benevolence), implying that the customary land rights of the people are not a formal title eligible for ganti rugi (compensation). Moreover, as a protest against the ongoing land grabbing, many people have adopted the strategy of not selling their land to the company.

The dynamism of Indonesian society with regard to the customary land rights is evolving towards their legal recognition. This dynamic energy will not subside as long as local people, who base their substantial livelihood on the land, remain at the forefront of the movement, backed by plentiful initiatives by NGOs, academia, bureaucrats, and the civil society as a whole.

Acknowledgements

The survey was financed by the Matching Fund Program of the Ministry of Education and Culture of the Government of Indonesia, and the Peatland and Mangrove Restoration Agency (BRGM). This survey was also financed by the JSPS Grand-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) titled “Property Rights and Customary Law in Indonesia” (24K03164). The survey was conducted in collaboration with BRGM, School of Environmental Science (SIL), Faculty of Humanities (FIB), University of Indonesia (UI), and Agrarian Resource Center (ARC). We would like to say sincere thanks to these institutions, and also to many students from the University of Indonesia, Gajah Mada University, and Bogor Agricultural University who supported us during the field work in 2023-2024.