Large pans, often bearing exterior fabric impressions,Footnote 1 are common at Indigenous salt-making sites throughout the Mississippian Southeast and Midwest. These vessels, typically over 1–2 cm thick and tempered with coarsely ground shell,Footnote 2 were durable enough to withstand prolonged exposure to fire, and their wide openings served to facilitate the evaporation of brine (Figure 1). As a result of these qualities, they are sometimes referred to as “saltpans” or “salt pans.” Despite being among the most durable precontact ceramic vessels made in North America, these vessels are prone to cracking and breaking over time, especially with repeated use, making it common to find large quantities of pan sherds at salt production sites (Brown Reference Brown1980; Bushnell Reference Bushnell1907; Dumas Reference Dumas2007; Early Reference Early and Early1993; Guidry and McKee Reference Guidry and McKee2014; Keslin Reference Keslin1964; Muller Reference Muller1984; Muller and Renken Reference Muller and Renken1989).

Figure 1. Sketch of a fabric-impressed pan from southern Indiana (probably the Bone Bank site) made by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur in 1828. Lesueur notes that the vessel has a diameter of 71 cm (28 in.) and a height of 20 cm (8 in.). Image reproduced with permission from the Muséum d’histoire naturelle du Havre (inventory number: 41208).

Although traditionally associated with brine reduction, fabric-impressed pans are also found at sites without nearby sources of salt or at sites with weak saline springs (Brown Reference Brown1980:29–30). This is particularly evident in the Middle Cumberland Region (MCR) of north-central TennesseeFootnote 3 where pans have been found in a variety of domestic and nondomestic contexts (see Barker and Kuttruff Reference Barker and Kuttruff2010:14; Eubanks et al. Reference Eubanks, Smith, Guidry, McKee, Dumas and Eubanks2021; Jones Reference Jones2017:35; Moore Reference Moore2005:151; Moore and Breitburg Reference Moore and Breitburg1998:Table 8; Moore and Smith Reference Moore and Smith2001:127–128; Myer Reference Myer1928:526–527; Figure 2). Given the presence of these vessels at such sites, it is clear that our understanding of their function(s) remains incomplete.

Figure 2. Example of fabric-impressed pan sherds from the MCR. (Color online)

Background

The MCR contains evidence of Indigenous occupation dating back to the Paleoindian period (prior to 10,000 BP; Smith Reference Smith1992). However, beginning around AD 1300 and accelerating through the first half of the fifteenth century, this region experienced a significant depopulation event driven by a series of severe, multidecadal droughts (Cobb et al. Reference Cobb, Krus, Deter-Wolf, Smith, Boudreaux and Lieb2024). By the second half of the fifteenth century, this abandonment was all but complete. Consequently, the chronological range considered here, as well as the period during which shell-tempered Mississippian fabric-impressed pans were produced, is from approximately AD 1000 to 1475.

The function of fabric-impressed pans at sites without a nearby source of brine or at sites with weak saline springs has been the subject of some speculation over the past several decades; however, little work has been conducted to address this issue. It has been suggested that these pans could have been involved in the preparation or serving of food (Brown Reference Brown1980:29; Eubanks et al. Reference Eubanks, Smith, Guidry, McKee, Dumas and Eubanks2021:38; Pollack Reference Pollack1998:353, 356; Thruston Reference Thruston1973:159; Webb Reference Webb1952:90, 93), and it is known that they were sometimes used to line graves, especially in the Mississippian MCR (Brown Reference Brown1981:6–7; Bushnell Reference Bushnell1908; Dowd Reference Dowd1969:6–7; Thruston Reference Thruston1973:159). It has also been argued that pans were used to concentrate mineral-rich waters (Clanton and Eubanks Reference Clanton and Eubanks2018; Eubanks et al. Reference Eubanks, Smith, Guidry, McKee, Dumas and Eubanks2021; Millichamp et al. Reference Millichamp, Eubanks and Saul2023), perhaps in an effort to create a purgative tonic similar to the Black Drink (see Emerson Reference Emerson, Peres and Deter-Wolf2018; Hudson Reference Hudson1979). Although some pans might have been employed in such a manner, this latter idea is difficult to test, given that mineral residues easily dissolve and wash away. However, if pans were occasionally used for cooking foods such as maize, residues from this activity could be preserved in the vessels’ walls. For instance, as part of the nixtamalization process, some Indigenous groups slow boiled their corn for extended periods—sometimes up to 18 hours (Briggs Reference Briggs2017:Table 3.3, 64). Although this was often done in ceramic jars, the protracted boiling technique closely resembles methods used for brine evaporation, which makes it plausible that pans could have been used for any activity that required the prolonged boiling of a liquid.

Methods

A total of 74 fabric-impressed sherds from 12 Mississippian sites within the MCR were selected for absorbed organic residue analysis using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS; Figure 3; Table 1). These sites were chosen because their associated materials were readily accessible at the Tennessee Division of Archaeology’s (TDOA) repositories in Nashville and at Pinson Mounds State Archaeological Park. The number of sherds examined per site ranged from 1 to 15, reflecting differences in excavation thoroughness and the prevalence of fabric-impressed pans. None of these sites have strong saline springs, but some—such as Sulphur Dell and Castalian Springs—have mineral springs with a low salt content (Eubanks et al. Reference Eubanks, Smith, Guidry, McKee, Dumas and Eubanks2021; Guidry and McKee Reference Guidry and McKee2014).

Figure 3. The MCR with the locations of sampled sites.

Table 1. Sites in the MCR Selected for Analysis.

Although the sampled sites all date to within several centuries of each other, some (e.g., Castalian Springs) have well-defined chronologies, whereas others do not. Therefore, teasing out fine-scale chronological variation remains beyond the scope of what the present study can accomplish. In addition, an effort was made to collect samples from non-mound habitation sites, but there is a sampling bias toward mound and mound and village centers, given that these are more likely to have been subject to large-scale excavations. Sherds from feature contexts were given preference over those from nonfeature contexts,Footnote 4 though in many instances, sherds from nonfeature contexts were sampled.

Samples were extracted using the direct acidic methanol extraction methodology described in Correa-Ascencio and Evershed (Reference Correa-Ascencio and Evershed2014), using isotopically measured methanol and isotopically measured µl N,O-bis (trimethylsilyl) fluoroacetamide (BSTFA) + 1% trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) to derivatize compounds.

Samples were analyzed on an Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph interfaced to an Agilent 5973 quadrupole mass spectrometer using a DB-1HT 15 m × 0.32 mm column with 0.1 µl film thickness. The temperature was held at 50˚C for two minutes, then ramped at 10˚C/minute until 300˚C, followed by a 10-minute hold at that temperature. Total runtime was 42 minutes. Prior to analysis each day, the GC/MS was tuned with DFTPP to EPA standards to ensure consistent and precise mass spectrometry.

Solvent blanks were run in parallel with the archaeological samples and were used to control for laboratory contamination. The blanks associated with these samples were clean, indicating that no laboratory contamination was present in the samples. Samples were run in a semiblind fashion, in that each sample was assigned a lab number for analysis, and the provenience of the samples was not used until interpretation began to take place.

CSIA Methods

Compound-specific isotope analysis (CSIA) was carried out on all residues estimated to contain sufficient fatty acid for analysis. All CSIA analysis was performed at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry Lab—directed by Chad Lane, with assistance by Hai Pan—on a Delta V Plus mass spectrometer interfaced to a Thermo 1310 gas chromatograph using a 60 m 0.25 ID DT-5 column and Isolink II interface. Temperature programs began with a two-minute hold at 70°C, followed by a ramp at 20°C/minute to 180°C, then a 5°C/minute ramp to 300°, followed by a five-minute hold at that temperature. All samples were run in duplicate, with calibration runs of known compound mixtures (IU B5 Alkane mixture) run after every three injections, and regular blank runs to ensure that the column and autosampler solvent were clean.

Uncertainties were calculated using the process developed by Polissar and D’Andrea (Reference Polissar and D’Andrea2014), which allows pooled uncertainties from all aspects of the CSIA analytical process, including calibration, instrument standard, derivatization, and variation between multiple runs.

Interpretive Methods and Defining “Empty”

In this study, pans used primarily or entirely for salt/mineral processing were assumed to be “empty” in residue terms, because of the lack of lipids in salt and salt water. For residue purposes, Evershed (Reference Evershed2008) has suggested that 5 μg of lipid per gram of potsherd (µg/g) is the lower limit for interpretation of an archaeological sample, whereas other researchers have suggested 0.5 µg/g (Hart et al. Reference Hart, Taché and Lovis2018). This limit appears to depend on several factors, including the sensitivity of the instrument, the possibility of postdepositional contamination, and the possibility of lipids being reintroduced to a pot during open-pit firing (Reber et al. Reference Reber, Kerr, Whelton and Evershed2019).

Defining “empty” was more difficult than originally envisioned, partially because of the presence in many of the residues of compounds atypical for archaeological residues, including even-chained alkanes, hopanes, and cyclic octaatomic sulfur. These were generally interpreted as contamination from burial, deposition, and storage—although it is possible that they originated in lipids deriving from microorganisms, organic material, and metabolic byproducts that might have been concentrated during the process of extracting salt.

Even residues that had low amounts of limited fatty acids often contained more than 5 μg lipid/g sherd because of the presence of these compounds. As a result, residues at or below 5 μg lipid/g sherd were defined as “empty.” Those between 5 and 30 μg lipid/g were defined as “probably empty” if the residue was atypical of archaeological residues with limited fatty acids and with most of the residue consisting of nondiagnostic compounds typical of soil contamination or possible brine concentration. For a further description of interpretive methods and contamination, please see Supplementary material 1.

Interpreting CSIA Results

Given that the ecosystem in Middle Tennessee is largely C3, maize or other plants with C4 or crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) photosynthesis can be detected using CSIA analysis. Maize can be most accurately detected in pottery residues by doing CSIA on n-dotriacontanol, a compound that is more common in maize than in many other resources processed in pottery in the southeastern United States (Reber et al. Reference Reber, Dudd, van der Merwe and Evershed2004). However, this compound was not present in any of the residues in this study. As a result, the detection of C4 contribution to the residues depended on analysis of the fatty acids C16:0 and C18:0, which are ubiquitous in residues largely because they are present in nearly all foodstuffs.

As has often been discussed, plants with CAM photosynthesis may have δ13C values that overlap with C4 plants (Tankersley et al. Reference Tankersley, Conover and Lentz2016; van der Merwe Reference van der Merwe1991; and others), and there are also occasional native C4 plants that are part of the diet in the southeastern United States. Candidates for this type of plant include purslane (Portulaca oleracea), which alternates between CAM and C4 photosynthesis (Koch and Kennedy Reference Koch and Kennedy1980; Tankersley et al. Reference Tankersley, Conover and Lentz2016), prickly pear cacti (Opuntia spp.) with CAM photosynthesis, and panic grass (Panicum spp.) and amaranth (Amaranthus spp.), both of which vary by species (Giussani et al. Reference Giussani, Cota-Sánchez, Zuloaga and Kellogg2001; Sage et al. Reference Sage, Sage, Pearcy and Borsch2007). Although maize would seem to be the most likely source for C4 photosynthesis in residues from the Mississippian period in the MCR, the possibility of purslane, prickly pear, panic grass, or amaranth cannot entirely be discounted.

Because fatty acids are present in animals as well as plants, the potential presence of fatty acids from animal-based lipids must also be addressed. Carbon isotope values are passed up the food chain as individuals eat plants (or consume other animals that ate the plants), so the fatty acids from an animal that eats C4 or CAM plants may mimic those of a C4 or CAM plant itself, possibly with a slight trophic shift (Twining et al. Reference Twining, Taipale, Ruess, Bec, Martin-Creuzburg and Kainz2020). In order to show a strong C4 signature, the animal in question would have to be eating almost entirely C4 or CAM resources, which seems unlikely given the general C3 nature of the ecosystem in the study area.

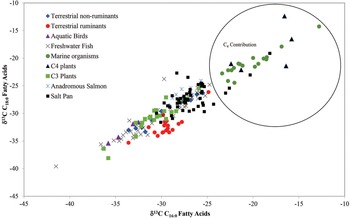

Finally, as shown in Figure 4, marine fish have δ13C values that overlap with those of C4 plants. However, since the residues in this study were from pottery excavated in Tennessee, the presence of marine resources in the pottery seems unlikely. Freshwater resources from a primarily C3 environment do not overlap with C4 resources, as also shown in Figure 4. C4 contributions to the fatty acids in this study are likely from C4 or CAM plants, with maize the most likely source.

Figure 4. δ13C values of C16:0 and C18:0 fatty acids from a variety of resources with the saltpan sherds indicated by a black square. Four of these derive primarily from C4 lipids, whereas the others are predominantly C3. Resource data is taken from Anderson et alia (Reference Anderson, Tushingham and Buonasera2017), Woodbury et alia (Reference Woodbury, Evershed and Rossell1998), Spangenberg (Reference Spangenberg2016), and from work done previously in the University of North Carolina at Wilmington (UNCW) laboratory. (Color online)

Results

Of the 49 sherds submitted for CSIA analysis, four contained clear C4 (likely maize) contributions to their fatty acids, as shown in Figure 4 and Table 2. However, given the relatively low abundance of maize lipids compared to other resources (Reber et al. Reference Reber, Dudd, van der Merwe and Evershed2004:692–693), it is possible that other vessels in the sample were involved in the preparation of this food, given that a substantial amount of maize must be processed compared to other resources before its lipids become detectable. In addition to the four C4 samples, 44 contained primarily C3 residues, and one did not contain enough fatty acids to complete the analysis successfully.

Table 2. CSIA Results from All Sherds Successfully Analyzed in This Project.

Notes: Results are organized by degree of enrichment of the C16:0 fatty acid, with δ13C values reported in ‰ PDB. The solid black line indicates the border between C4- and C3-dominated residues.

* Sites with “JDC” preceding the sample number were donated to the TDOA by amateur archaeologist John Dowd.

The four residues with C4 contributions derived from four different sites (Table 2). Although the sample from the Barnes site (JDC 10) did contain some soil and/or diesel oil contamination, the fatty acids were convincingly dominated by C4 resources. This is different from the other residues in the study containing oil contamination, which derived from C3 resources. The oil contamination, therefore, was not the source of the C4 contribution. Fewkes Sample 2 contained a small amount of residue, close to the limit of “empty” as defined above, but it appeared to be interpretable and not contaminated, with a standard distribution of fatty acids and alkanes typical of an archaeological sample. As a result, this sample was interpreted as containing small amounts of C4 residue.

Of the 74 samples, 21 were interpreted as “empty” or “probably empty.” This does not include the 16 samples that were uninterpretable due to contamination. Given the probable absence of lipids from minerals such as salt, it was not possible to determine if a sherd was part of a brine or mineral-processing vessel. However, it is reasonable to assume that at least some of the empty sherds came from vessels that were used in this manner. Of the sites sampled in this study, as shown in Table 3, Castalian Springs and Sulphur Dell had the highest incidence of “empty” sherds, which may not be coincidental given that both sites have or once had weakly saline mineral springs.

Table 3. Summary for All Residues in the Project, Showing Site Totals and Overall Interpretations by Site.

Interestingly, 27 samples contained interpretable residues from resources other than maize. These resources were interpreted as well as possible based on fatty acid abundances (Table 3) but seemed to derive most commonly from plant resources, keeping in mind the difficulties inherent in interpreting vessel contents through fatty acids alone (Reber and Evershed Reference Reber and Evershed2004; Whelton et al. Reference Whelton, Hammann, Cramp, Dunne, Roffet-Salque and Evershed2021; and many others). Although the specific C3 plants processed in these sherds are unknown—and there are numerous possibilities, including nuts (e.g., for kanuchi), tubers, roots, beans, squash, seeds, or fruit—the use of pans for processing C3 resources appears to have been more common than their use for processing maize.

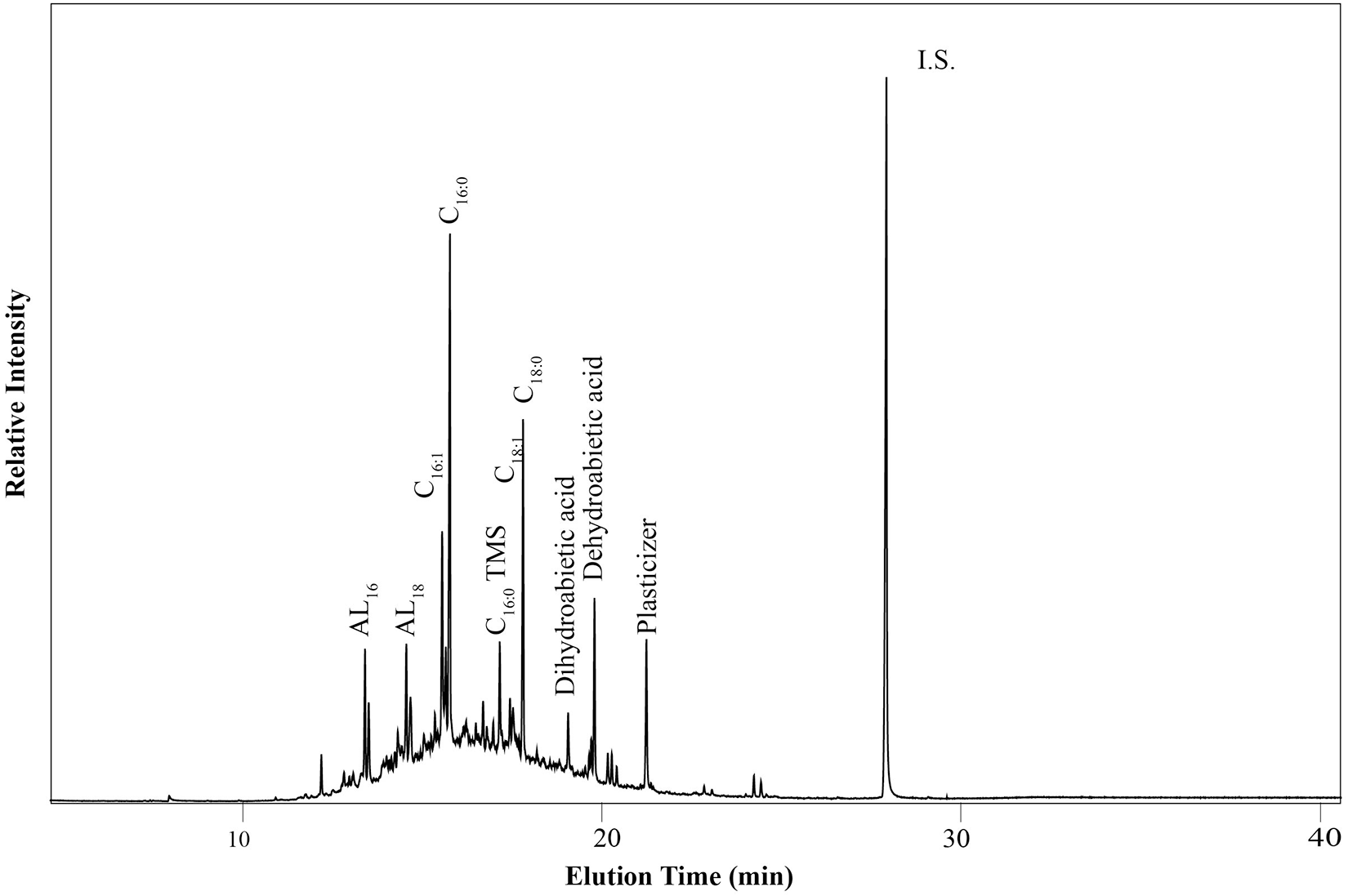

Conifer resins were detected in seven of the 32 interpretable residues, including two of the C4-containing residues—Fewkes 2 and Brick Church Pike 8 (BCP 8). Resin might have been used to seal the saltpans prior to use, potentially leading to the misinterpretation of “empty” sealed sherds as containing residues from resource processing (Reber and Hart Reference Reber and Hart2008). However, conifer resin was present in less than a quarter of interpretable samples, suggesting that sealing was not ubiquitous in the tested saltpans. Residues with a conifer contribution also generally contained small amounts of one or two highly oxidized compounds, suggesting that only small amounts of the resin remained in the residues. In at least a few cases, “probably empty” sherds appeared to derive primarily from conifer resin. It is notable that conifer resin was unlikely to lead to false positive identifications of resource processing.

Conifer resin, which is a C3 resource, might also potentially affect the δ13C values of fatty acids in interpretable residues, possibly masking C4 resources. However, conifer resin was present, as mentioned, in two of the C4 residues. It does not seem to have contributed enough to the fatty acids in Fewkes 2 to affect the isotope values. In BCP 8, as shown in Figure 5, conifer resin comprised an appreciable part of the residue. In this case, it appears that fatty acids from the conifer resin contributed enough C18:0 fatty acid to deplete its δ13C value slightly; however, given that C16:0 is less abundant in conifer resin than C18:0, the value of the C16:0 fatty acid was shifted much less, and the residue was still interpreted as deriving primarily from C4 resources (Table 2). Therefore, given that BCP 8 contained more conifer resin than all but one other sherd in the study, conifer resin does not seem to have masked the presence of C4 resources in the residues.

Figure 5. Gas chromatogram of Brick Church Pike Sample 8, showing the fatty acid distributions and the presence of conifer resin (dehydroabietic acid and dihydroabietic acid). I.S. stands for the Internal Standard, n-tetratriacontane. The unusually abundant C16:1 fatty acid is likely from the conifer resin.

Two other unexpected results were obtained from this study. First, indicators for fish and/or shellfish were identified in three residues—two from Sulphur Dell and one from Fewkes (see Table 3). Sulphur Dell samples 1 and 5 both contained pristanic acid with the monounsaturated fatty acid C22:1 present, whereas C22:0 was not only lesser in abundance but absent from both residues. Pristanic acid is an isoprenoid fatty acid that is often used as an indicator for fish or shellfish, although it is not a biomarker per se (Baeten et al. Reference Baeten, Jervis, De Vos and Waelkens2013; Corr et al. Reference Corr, Richards, Jim, Ambrose, Mackie, Beattie and Evershed2008; Roffet-Salque et al. Reference Roffet-Salque, Dunne, Altoft, Casanova, Cramp, Smyth, Whelton and Evershed2017). Abundant monounsaturated fatty acids, especially C22:1, is also an indicator for fish and/or shellfish (Brown and Heron Reference Brown, Heron, Mulville and Outram2005). Generally, the presence of two such indicators permits an interpretation of “possible fish/shellfish presence.” Sample 1 from Fewkes had three isoprenoid fatty acids—trimethyltridecanoic acid (TMTD), pristanic acid, and phytanic acid—as well as abundant C22:1. This residue can be interpreted as probably containing fish/shellfish lipids. The most common fish identified in the MCR are freshwater drum, river redhorse, catfish, and various bass species; however, fish do not appear to have been exceptionally important in the diets of the region’s Mississippian occupants (Smith Reference Smith1992:37). At present, residue analysis cannot distinguish between lipids from fish and shellfish, either bivalve or gastropod. Therefore, these three pots may have been used to process either fish or any type of shellfish.

The second unexpected result was the high incidence of petroleum oil in the residues, typically in the form of hopanes, likely resulting from modern diesel-oil contamination during deposition. However, one sherd—Sulphur Dell Sample 9—appeared to contain raw crude oil, with an Unresolved Complex Mixture (UCM; Gough and Rowland Reference Gough and Rowland1990) that made integrating the residue difficult. This sherd contained such a high concentration of oil that it likely came into direct contact with crude oil, either intentionally in the past or as a result of modern contamination. Sufficient petroleum oil to produce a smaller UCM was present in three sherds from Travellers Rest, two from Harpeth Meadows, and one from Moss Rose / Cooper Creek (see Table 3).

Conclusion

Understanding how fabric-impressed “saltpans” were used provides direct and tangible insight into Mississippian foodways. Although they are often associated with evaporating saline or mineral-rich waters, it is evident—at least in the MCR—that these were multifunctional vessels used for food preparation, likely including soaking or boiling maize; cooking animal foods, such as fish or shellfish; and processing at least one, if not multiple, C3 plants. This multifunctionality is exemplified at places such as Sulphur Dell, located in modern-day downtown Nashville. This likely salt/mineral-processing site yielded two sherds with evidence of fish or shellfish, one sherd with probable maize residue, and eight “empty” sherds—a pattern consistent with vessels used for processing salt or other minerals. Although pan-lined graves have not been documented at Sulphur Dell, it is likely that the people at this site were familiar with this burial tradition, given that pan-lined graves have been identified elsewhere in and around Nashville (Thruston Reference Thruston1973:159).

In some contexts, pans may have been viewed as an alternative type of cooking vessel (Brown Reference Brown1980:29; Thruston Reference Thruston1973:159; Webb Reference Webb1952:90, 93), complementing the standard Mississippian jar or bowl. However, a key morphological distinction separates these vessel forms: jars have restricted openings, whereas pans and bowls have open forms that allow for faster evaporation. This characteristic makes pans and bowls particularly suited to reducing brine to produce salt. Furthermore, when used for cooking, their higher rates of evaporation may have been seen as advantageous (e.g., if trying to create a concentrated broth or liquid). However, for foods that required prolonged heating—whether by boiling or another method—pans may have been preferred over bowls due to their thicker walls and greater durability, despite being less portable. Although the reasoning behind choosing a pan, bowl, or jar for meal preparation remains unclear, one thing is certain: pans were versatile tools, not limited solely to salt production.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Tennessee Division of Archaeology—especially Phil Hodge, Macie Orrand, Paige Silcox, Satin Platt, Aaron Deter-Wolf, and Hannah Guidry—as well as Olivia Thompson and Debbie Shaw from the Tennessee State Museum, Jay Gray and the Brentwood City Commission, Krista Gray from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s Illinois History and Lincoln Collections, and Gabrielle Baglione and Jean-Marc Argentin from the Muséum d’histoire naturelle du Havre. The MCR base map used in Figure 3 was created by Eckhardt and Deter-Wolf (Reference Eckhardt and Deter-Wolf2023) and modified by Paige Silcox to include the approximate locations of the analyzed sites. We also thank Kayla Albee for her help with sample collection and Lauren Averill for her assistance with photography. Kevin Smith provided valuable insight into this project. Chad Lane and Hai Pan of the UNCW IRMS Lab generously assisted with CSIA instrumentation, and Zoe Collins ably supported residue extraction. Finally, we express our gratitude to this report’s peer reviewers, the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Middle Tennessee State University, and the Department of Anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Middle Tennessee State University’s MT-IGO program.

Data Availability Statement

The residue analysis conducted for this research was destructive. Whenever possible, sherds weighing more than 3.5 g (the minimum sample size) were selected to avoid destroying entire specimens. The analyzed sherds and their associated collections are stored at the TDOA’s repositories in Nashville and at Pinson Mounds State Archaeological Park. Requests to reanalyze or examine these materials can be directed to the Tennessee State Archaeologist. GC/MS data files are held in an online repository hosted by the UNCW residue lab and may be obtained upon request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2025.23.

Supplementary material 1. Interpretive Methods (text).