Introduction

As populations age globally, maintaining social connection has emerged as a critical factor in supporting successful ageing in place. The ability to remain connected within one’s community directly influences whether older adults can continue living independently in their own homes, a wish expressed by the majority of Australians (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2013). Socially connected individuals typically maintain better physical and cognitive health, require fewer institutional supports and report higher quality of life as they age (Howick et al. Reference Howick, Kelly and Kelly2019). In Australia, approximately 16 per cent of people are aged 65 and over and this number is projected to reach approximately 23 per cent by 2066 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2024). Therefore, understanding and addressing the factors that influence social connection among older adults is a priority for sustainable community development and ageing-in-place policies.

The Global Initiative on Loneliness and Connection (GILC) framework for conceptualizing social connection (Badcock et al. Reference Badcock, Holt-Lunstad, Garcia, Bombaci and Lim2022) represents the agreed upon approach in modern social connection research (Holt‐Lunstad Reference Holt‐Lunstad2024). Following these definitions, we conceptualize social connection as a multi-dimensional construct encompassing structural, functional and quality domains. The GILC defines social connection as ‘the size and diversity of one’s social network and roles, the functions these relationships serve and their positive or negative qualities’ (Badcock et al. Reference Badcock, Holt-Lunstad, Garcia, Bombaci and Lim2022). At the opposite end of this continuum lies social disconnection, characterized by experiences of loneliness (subjective unpleasant feelings of lack of connection), social isolation (objectively few social relationships and infrequent interaction) and social negativity (poor relationship quality) (Badcock et al. Reference Badcock, Holt-Lunstad, Garcia, Bombaci and Lim2022). Individuals exist along this connection–disconnection continuum, with their position influenced by both personal characteristics and environmental factors that either foster connection or contribute to disconnection.

The health implications of social disconnection have been explored extensively, with research demonstrating increased risks of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, premature cognitive decline and mental health issues like depression and anxiety (Morina et al. Reference Morina, Kip, Hoppen, Priebe and Meyer2021). The health consequences are further compounded by the economic costs of social disconnection through increased health service utilization and reduced productivity (Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Lee, McLeod, Mahmuda, Howard, Cockrell and Angeles2019; Morina et al. Reference Morina, Kip, Hoppen, Priebe and Meyer2021). This evidence base underscores the importance of approaches that target environmental conditions fostering social connection, thereby supporting individuals’ movement towards the connection end of the continuum and away from the adverse health outcomes associated with social disconnection.

Theoretical framework

Examining social connection through environmental lenses aligns with health promotion principles that recognize the broader community and societal influences on health and wellbeing, extending beyond individual choices to consider the contexts in which people live (Golden and Wendel Reference Golden and Wendel2020). The social-ecological model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding these multi-level influences, conceptualized as nested systems where individual characteristics interact with interpersonal relationships, community contexts and broader societal factors (Bronfenbrenner Reference Bronfenbrenner1977; Dahlberg and Krug Reference Dahlberg, Krug, Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi and Lozano2002).

A growing body of research has applied social-ecological approaches to examine environmental determinants of social connection among older adults. Studies examining built environment factors have demonstrated how walkable neighbourhoods, public spaces and community amenities influence connection opportunities (Finlay et al. Reference Finlay, Esposito, Kim, Gomez-Lopez and Clarke2019; Ottoni et al. Reference Ottoni, Winters and Sims-Gould2022). Research on age-friendly communities has identified how transport accessibility, safety perceptions and social infrastructure shape older adults’ ability to maintain social relationships (Cao et al. Reference Cao, Dabelko-Schoeny, White and Choi2020; Hartt et al. Reference Hartt, DeVerteuil and Potts2023). Critical perspectives on urban ageing have examined how community and societal factors create both constraints and opportunities for older adults’ social participation, demonstrating the importance of involving older people themselves as actors in understanding their environmental experiences rather than passive recipients of interventions (Buffel et al. Reference Buffel, Phillipson and Scharf2012). However, most existing research has focused on individual components of the social ecology rather than examining how factors across multiple levels interact to shape connection experiences.

Within this framework, the individual level encompasses personal characteristics including psychological traits, demographic factors and health status that influence connection capacity (McLeroy et al. Reference McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler and Glanz1988). The interpersonal level represents close social networks and relationships with family, friends and colleagues that provide direct connection experiences (McLeroy et al. Reference McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler and Glanz1988). The community level encompasses the physical and social environments where relationships form, including neighbourhood characteristics, community organizations and local resources (Gibney et al. Reference Gibney, Moore and Shannon2019). The societal level represents broader contextual factors including cultural norms, policy frameworks and economic systems that create the conditions within which all other levels function (Dahlberg and Krug Reference Dahlberg, Krug, Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi and Lozano2002).

Research gap

Recent longitudinal research using Australian population data identified community engagement, neighbourhood social cohesion, cultural practices and neighbourhood safety as significant community-level determinants of loneliness and social isolation among older adults (Meehan et al. Reference Meehan, Clare, Grunseit and Merom2025). However, this quantitative approach, while establishing statistical associations, provides limited insight into how older adults perceive and experience these environmental factors in their daily lives, or how they understand the mechanisms through which these factors influence their social connection experiences.

A systematic synthesis of qualitative research on loneliness shows that most studies focus on individual and interpersonal dimensions, with limited exploration of how community and societal contexts specifically influence connection experiences from older adults’ perspectives (McKenna-Plumley et al. Reference McKenna-Plumley, Turner, Yang and Groarke2023). Furthermore, few studies have applied social-ecological frameworks to examine how factors across multiple levels interact to shape connection outcomes, particularly using older adults’ own accounts to understand these complex relationships.

This study aims to extend existing research by exploring older adults’ perspectives on environmental factors that influence their position on the social connection–disconnection continuum. Specifically, we examine: (1) how older adults perceive and experience community and societal factors identified in quantitative research as significant determinants of social connection, including community engagement, neighbourhood social cohesion, cultural practices and neighbourhood safety; (2) additional environmental factors that older adults identify as important for their connection experiences beyond those captured in quantitative measures; and (3) how factors across different social-ecological levels interact to shape where individuals sit on the connection–disconnection continuum. By examining these factors from older adults’ perspectives across diverse community contexts, this research provides foundational evidence for developing interventions that foster social connection, supporting individuals’ movement towards the connection end of the continuum and away from the adverse health outcomes associated with social disconnection.

Methods

Research design

We used qualitative focus groups to explore older adults’ perceptions of factors that influence their social connection experiences. Specifically, we employed a qualitative descriptive approach that enables theoretically informed yet flexible exploration of complex social phenomena in applied health research contexts (Colorafi and Evans Reference Colorafi and Evans2016). This approach was particularly appropriate as it allowed us to examine participants’ perceptions of community and societal factors identified in quantitative research while remaining open to emergent concepts beyond our predetermined social-ecological framework. We aimed to uncover the meaning of participants’ perceptions regarding their social environment using naturalistic inquiry (Colorafi and Evans Reference Colorafi and Evans2016).

Sampling and recruitment

Using maximum variation sampling, four localities within New South Wales, Australia, were purposively selected. This selection was based on Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey data to capture diverse social connection experiences. We operationalized social disconnection through combined loneliness and social isolation measures, identifying localities with high proportions of well-connected residents (lowest quartile) and disconnected residents (highest quartile). Localities were further stratified by geographic classification (metropolitan/regional), resulting in four types: regional well-connected, regional disconnected, metropolitan well-connected and metropolitan disconnected areas.

Participants were recruited through multiple channels designed to reach both connected and disconnected older adults: social media posts in place-based community groups; physical posters in community venues; local council communication channels; and targeted outreach via community organizations. The latter was particularly important for reaching potentially isolated individuals who might not encounter general recruitment materials. All materials directed interested individuals to a brief screening survey to indicate focus group participation willingness.

Inclusion criteria were: primary residence within selected localities; aged 60+ years; no diagnosed cognitive decline; conversational English ability. We acknowledge potential selection bias towards socially engaged individuals, particularly through social media channels. To mitigate this, we asked community organizations to identify and invite potentially isolated members, though this was only marginally successful.

Eligible participants were contacted directly to arrange attendance, resulting in four focus groups (one per locality) with three to six participants each. This size range ensured diverse perspectives while allowing sufficient speaking time for all participants. The final sample consisted of 15 participants.

Data collection

Focus groups were conducted in community centres within each locality between August and December 2024. Community centres were selected as venues representing important connection hubs that could introduce participants to local resources. Each two-hour focus group included a refreshment break and was facilitated by the lead researcher with an experienced co-facilitator.

Our semi-structured question guide (in the supplementary material) was developed through iterative refinement. Initial questions were based on the social-ecological model and community and societal factors identified in quantitative research as determinants of social connection (Meehan et al. Reference Meehan, Clare, Grunseit and Merom2025). Following each focus group, the research team conducted debriefing sessions to identify emergent topics and refine subsequent questions, allowing exploration of new concepts while maintaining theoretical consistency.

As part of the recruitment survey, participants completed brief measures of loneliness and social isolation for descriptive purposes. Loneliness was assessed using the University of California, Los Angeles three-item Loneliness Scale, with participants rating agreement on a three-point scale (‘hardly ever’, ‘some of the time’, ‘often’). Social isolation was measured using the six-item Duke Social Network Scale, assessing social support availability on a six-point scale.

To minimize priming effects, focus groups began with open-ended questions about general social connection experiences before introducing the social-ecological model as a visual aid with four concentric circles (individual, interpersonal, community, societal levels). Each level was explained using everyday language and examples. Participants received handouts with working definitions of key concepts for reference throughout discussions. Facilitation employed circular questioning, validation of diverse viewpoints and gentle probing to explore experiences beyond predetermined frameworks. A copy of the question guide and other participant materials can be found in the supplementary material.

Focus groups were audio-recorded with written consent and manually transcribed verbatim by the lead researcher as part of the familiarization analysis (McMullin Reference McMullin2023). Transcripts were de-identified with speaker numbers assigned to maintain anonymity while preserving individual contribution tracking. Field notes documenting group dynamics and initial insights were completed immediately post-session by the facilitation team (DEM and MG) and integrated into the analysis.

Data analysis

We employed directed content analysis as described by Hsieh and Shannon (Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005) to analyse our focus group data. Directed content analysis is a structured approach that uses existing theory or research to identify key concepts as initial coding categories, while remaining open to new categories that emerge during analysis. This approach was appropriate for extending previous quantitative research on social-ecological factors influencing social connection by exploring how older adults perceive and experience these factors.

Data analysis utilized NVivo 15 (Lumivero 2024). The social-ecological model provided our initial coding framework, with the four levels (individual, interpersonal, community, societal) serving as predetermined categories. The lead researcher read all transcripts repeatedly for familiarization, then systematically coded text related to social connection using predetermined categories. Text that did not clearly fit within categories was assigned to the ‘other’ category for further analysis, ensuring that we captured both content that aligned with our theoretical framework and potentially important concepts that fell outside it. Coding reliability was enhanced through multiple strategies: facilitation team discussions ensured contextual information preservation; broader research team consultations (blinded to participant information) maintained objectivity; clear coding rules addressed text spanning multiple ecological levels; and memos documented all coding decisions and category development.

Reflexivity

Our research team brought diverse health sciences expertise, with the lead researcher trained in public health and social epidemiology, and co-authors contributing expertise in epidemiology, qualitative methods, community health and psychology. This disciplinary composition likely influenced our interpretation of findings, particularly in emphasizing health implications of social connection and public health intervention potential. Throughout data collection, the facilitation team maintained reflective awareness of how personal characteristics and professional backgrounds might shape participant interactions and discussions. Post-focus group debriefing sessions and regular contact enabled iterative refinement of the question guide and facilitation approach between groups. Analysis was conducted by the lead researcher with co-author supervision, incorporating regular team meetings to discuss emerging findings and interpretations. This collaborative approach helped ensure analytical rigour while acknowledging the influence of our health sciences perspective on data interpretation and theoretical framing.

Results

Fifteen participants took part across four focus groups, representing diverse social connection experiences across metropolitan and regional localities (Table 1). Participants ranged from 60 to 80+ years of age, with 12 females and 3 males participating. The sample included both Australian-born participants (n = 8) and those born overseas (n = 7), representing varied cultural backgrounds including British, European and Asian heritage. Health status also varied, with some participants managing chronic conditions that influenced their mobility and social participation, while others described themselves as active and healthy. Using the UCLA three-item Loneliness Scale, five participants were experiencing loneliness, while three participants were experiencing social isolation according to the Duke Social Network Scale (see Table 1).

Table 1. Participant demographics (n = 15)

Note: UCLA: Univeristy of California, Los Angeles.

Social connection factors across ecological levels

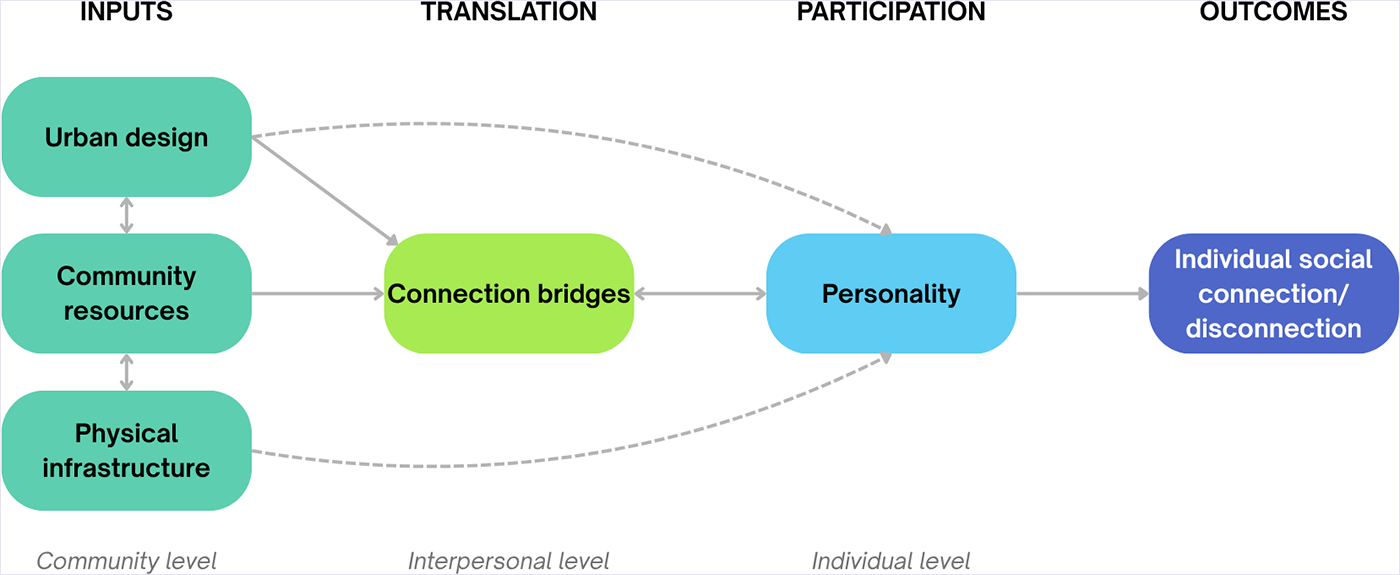

Participants identified factors influencing their social connection across individual, interpersonal, community and societal levels of the social-ecological model. Figure 1 summarizes the social connectors and disconnectors identified across these levels.

Figure 1. Summary of social connectors (+) and disconnectors (−) as described by participants within the social-ecological model.

Individual

At the individual level, having a purpose and role in society emerged as a critical factor for social connection. Participants frequently mentioned how having a meaningful role (e.g. volunteering, family responsibilities) provided motivation to engage socially: ‘I think loneliness for me is not having a role. It’s not having a purpose. It’s not being relied on’ (Speaker 1). Life stage transitions, particularly retirement, were frequently mentioned: ‘I think there’s more a sense of individual inadequacy in one way; they say teachers never die, they just lose their class’ (Speaker 6).

Participants discussed personality differences affecting connection approaches: ‘I talk to everyone and it’s rather, I suppose, it’s maybe a vanity within me. I like getting through to people’ (Speaker 9), while others noted: ‘I should be putting myself out there a bit more. That’s probably my biggest problem’ (Speaker 5).

Health impacts on connection were described both physically – ‘the significance of deafness on making people lonely … how difficult it is to maintain a sense of belongingness’ (Speaker 6) – and mentally – ‘many mental illnesses … stand as a barrier for them to meet people’ (Speaker 3). Pet ownership, particularly dogs, was consistently mentioned as facilitating connection: ‘I don’t think you feel lonely if you have a dog’ (Speaker 6).

Interpersonal

Family relationships formed the foundation of interpersonal connections for many participants: ‘keeping the connection with my family … we communicate probably half a dozen times a day’ (Speaker 5). However, family loss created significant gaps: ‘I’m in a situation where I don’t have any connection with family … so I am 100 per cent by myself’ (Speaker 12).

Participants emphasized relationship quality over quantity: ‘I’ve got so few people that I can really talk to. About things that are really very important to me’ (Speaker 8). Shared interests and values facilitated connections: ‘They could be much richer than me, or much poorer than me … as long as, you know, we are having something that really binds us together’ (Speaker 3).

Some participants described ‘connection catalysts’, which were individuals who facilitated connections for others: ‘Making a connection with me, saying, “Are you going to town?” I wouldn’t have done that to her if I was the person … Within a few minutes, she’d have conversations going on. But she just makes these friends wherever she is’ (Speaker 6). Life transitions disrupted interpersonal networks, with retirement, widowhood and relationship breakdown frequently mentioned as disconnectors.

Community

Participants described the importance of activity diversity, particularly in metropolitan areas: ‘If you make a little bit of effort, you can find so many socially connected activities’ (Speaker 3). Community-led initiatives were favoured: ‘I think it’s about just creating opportunities … find individuals who have the passion to do it and give them the facility’ (Speaker 10).

Physical infrastructure emerged as fundamental, with public third places highlighted: ‘down at the [church]. They were told they had to utilize the space, so they have lots of stuff there … you can make connections there’ (Speaker 4). Community atmosphere was described through aesthetics and characteristics: ‘You’ve got nice … houses that are well kept. And you can walk down the street … And there’s always somebody that’s out and about’ (Speaker 4).

Local businesses served as community nodes: ‘every Wednesday after the gym, we go out and have coffee at the [café], and every Wednesday, the table is reserved for us by [the workers]’ (Speaker 4). The significance of these became apparent when lost: ‘when we had a terrible hailstorm … you realise how connected you were to the shop people’ (Speaker 4).

Specific design features were mentioned as connection-friendly, including main streets – ‘with the coffee shops there and the tables and chairs out, if you’re a local and you go there, you’ll probably see two or three people there that you actually know’ (Speaker 5) – and cul-de-sacs – ‘it’s a dead end. So, people are coming to [this community] … They’re not going through it to another place’ (Speaker 10).

Local news sources were valued for community connection: ‘To me the local paper is also a very key indicator of community’ (Speaker 6). Loss was shown to affect community spirit: ‘Since the local paper went, the community spirit, it has dropped’ (Speaker 15).

Societal

Transport availability was discussed primarily in metropolitan areas: ‘for me, transport is a huge thing … whatever it is, I need to go from point A to point B’ (Speaker 12). New transport options were seen as community-building: ‘The new train link … it’s changed the dynamics considerably’ (Speaker 11).

Location differences were noted: ‘I think as well if you lived in the country, you wouldn’t feel lonely … Country people are lovely people, and they’re more welcoming’ (Speaker 7). Regional participants described greater perceived safety: ‘I feel safer as an older person than I would have 20–30 years ago walking up the street on my own’ (Speaker 14), while metropolitan participants reported more safety concerns: ‘These days, I get very frightened with the community, and I feel I’m safer by just staying in my house’ (Speaker 12).

Generational differences were described as creating divides: ‘I think it’s the lack of social cohesion between the age groups is what is a problem’ (Speaker 1). Policy influences were mentioned regarding housing: ‘I don’t think housing policy has caught up with society’s needs in terms of social connectedness’ (Speaker 10).

Cross-level interactions

Participants described experiences where factors across different ecological levels worked together to influence their connection outcomes. Three distinct interaction patterns emerged from their accounts.

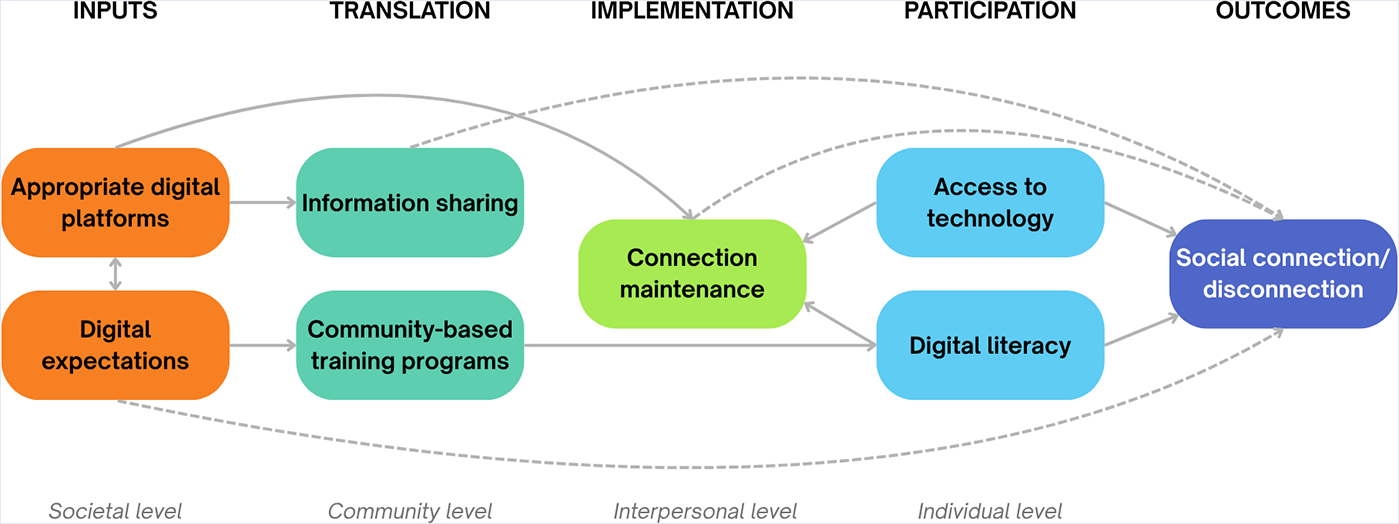

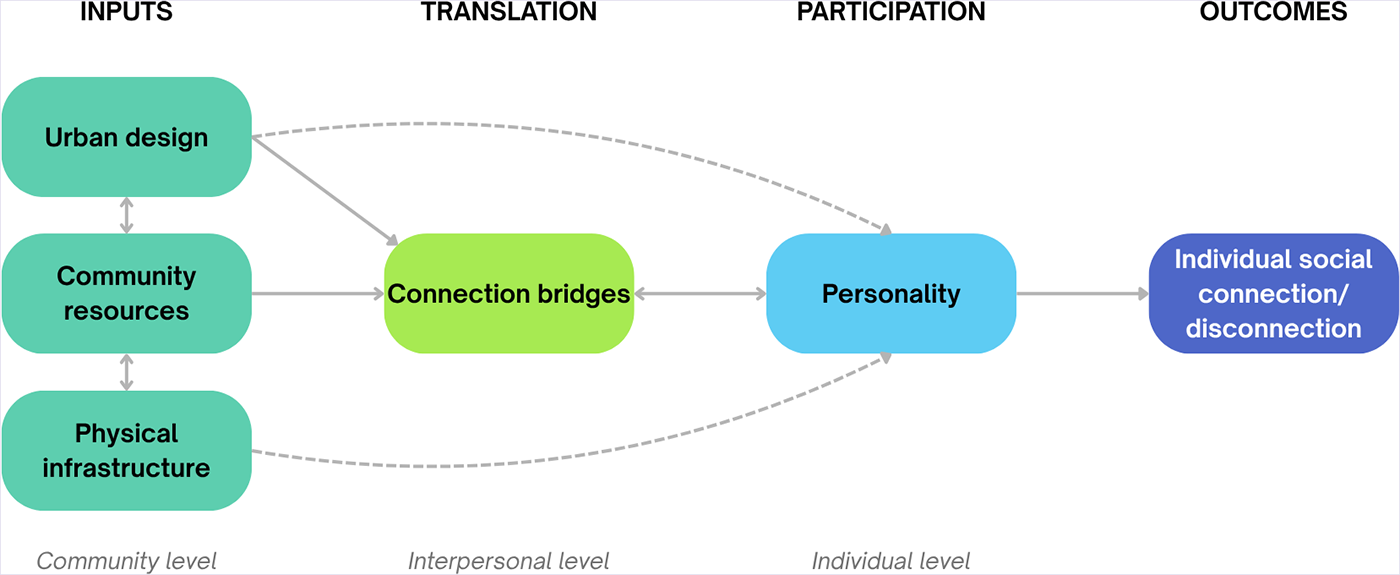

Individual traits, community spaces and interpersonal facilitators

Participants described how personality characteristics interacted with community resources and interpersonal relationships (Figure 2). Those identifying as more introverted described using community spaces for ‘passive’ connection: ‘I’d better get to the [shopping centre] because then I’ll be seeing people’ (Speaker 6), and ‘Going to the shopping centre or something, just so you feel like you’re part of something’ (Speaker 4).

Figure 2. Cross-level interaction patterns in social connection showing individual traits, community spaces and interpersonal facilitators.

However, participants also described how other community members could serve as bridges to wider networks. One participant provided a detailed example: ‘When I turned 81, she took me down to [the local high street] and bought a little birthday cake for me. And I felt as though I now belonged to the community. Every second person … said “Hello” to her. She’s just my model of community awareness’ (Speaker 6).

This example shows how individual characteristics (introversion), community infrastructure (local high street) and interpersonal relationships (well-connected person) can work together to create connection opportunities.

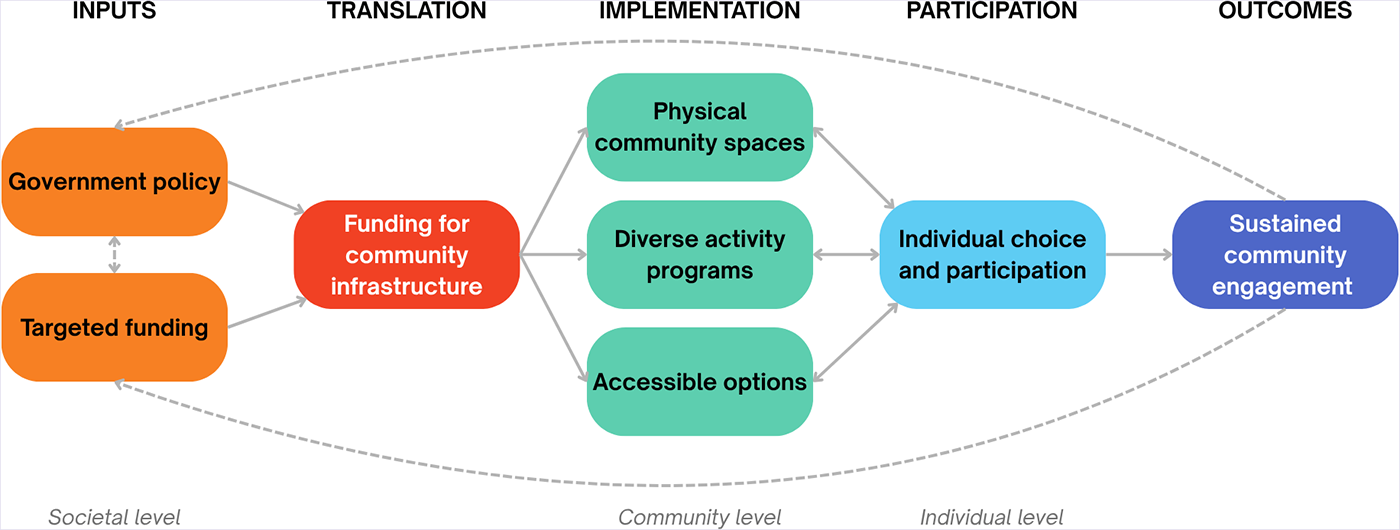

Digital technology

Participants described digital technology operating simultaneously across individual, interpersonal, community and societal levels, demonstrated in Figure 3. At the individual level, digital literacy determined access: ‘If you’re not on Facebook and not on social media, how do you get the information?’ (Speaker 6).

Figure 3. Cross-level interaction patterns for digital technology and social connection.

For those with access, technology maintained interpersonal connections: ‘On my phone, with my kids … we communicate probably half a dozen times a day with each one’ (Speaker 5). At the community level, local organizations provided crucial support: ‘Everything’s online. But rather than just saying we’re moving online, [the local organization] offered anybody who wasn’t computer literate down at the local café once a week … free lessons’ (Speaker 10).

Community digital platforms extended neighbourhoods: ‘So many people have left [this town] and lost connection to it. So, we formed this Facebook page’ (Speaker 15). At the societal level, participants described widespread digital expectations: ‘In society now, everywhere, they think, they take it for granted that everybody has got the app, download the latest app’ (Speaker 12).

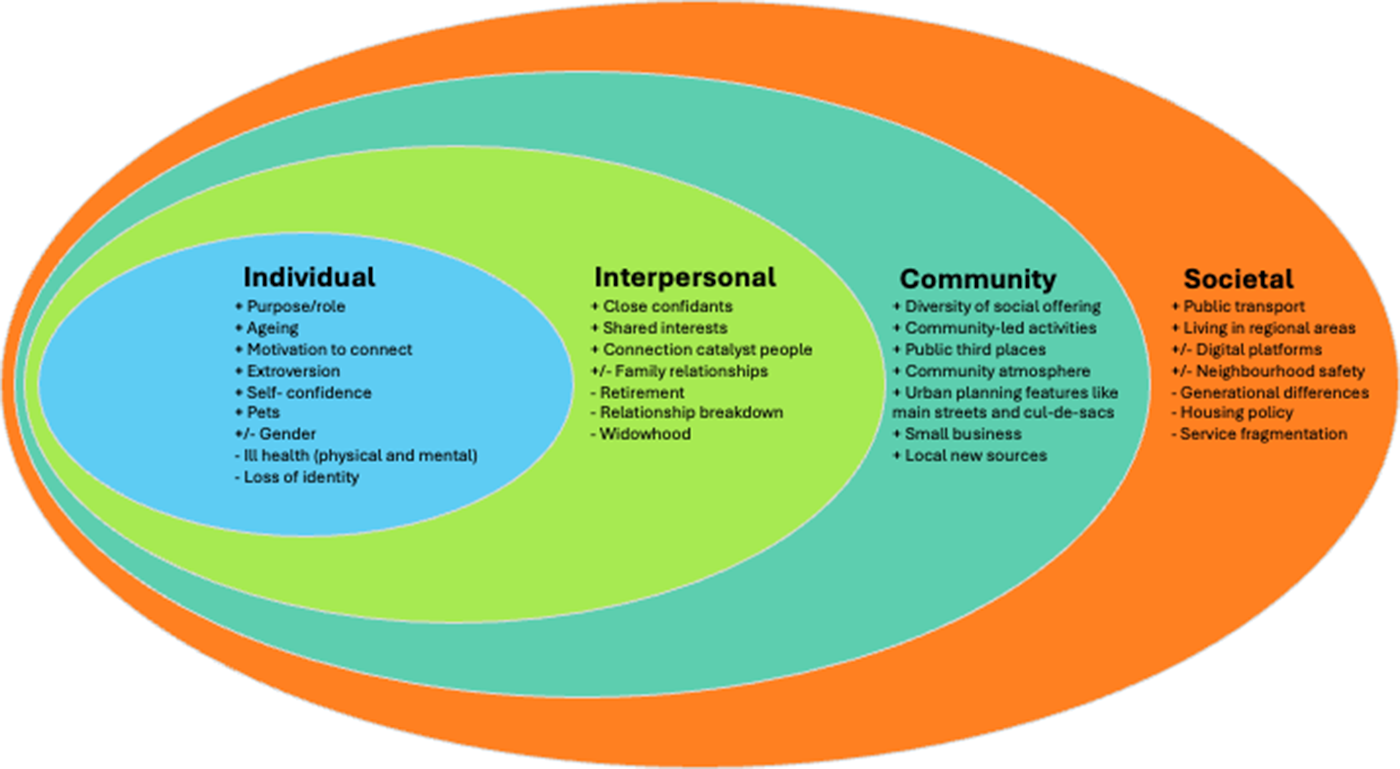

Policy, community infrastructure and individual participation

Participants described connections between government policies, community facilities and individual activities, as illustrated in Figure 4. They noted policy foundations: ‘There are ways of promoting neighbourhoods on a government level, particularly on a local government level’ (Speaker 6), and targeted funding: ‘Like in aged care, there are funded programmes around … where people can come together’ (Speaker 14). Furthermore, when policies translated into community infrastructure, participants described diverse activity options accommodating different interests. One group exchange illustrated this:

Figure 4. Cross-level interaction patterns in social connection showing policy, infrastructure and participation pathways.

Participant 11: ‘I mean, there’s, you know, courses to do, you can do a hell of a lot.’

Participant 8: ‘Yes, yes, there’s a lot there. And I actually go to an exercise class on a Saturday.’

Participant 9: ‘I used to give cooking classes there.’

Participant 8: ‘I’ve been doing the singing for over 10 years now.’

Participants also noted the importance of physical community spaces: ‘This community centre I think actually organized it, it’s good to have some place in the community, actual physical place, where you can have activities’ (Speaker 10). These patterns demonstrate how participants experienced connection through combinations of factors across ecological levels rather than through single-level influences alone.

Discussion

This study explored older adults’ perspectives on environmental factors that influence their social connection, extending existing social-ecological research by examining how community and societal factors interact dynamically to shape connection experiences. Our findings build upon established research demonstrating that environmental factors across multiple ecological levels influence older adults’ social connection status, while providing new insights into the mechanisms through which these factors operate in older adults’ daily lives. Participants readily identified factors across individual, interpersonal, community and societal levels that influenced their connection opportunities, confirming quantitative research highlighting the importance of neighbourhood safety, transport accessibility and community atmosphere. They also described additional environmental influences not captured in existing measures, such as local businesses functioning as informal social hubs, the layout of cul-de-sacs and main streets that facilitated casual encounters, and the decline of local media outlets that once fostered a sense of community identity. Most significantly, our analysis revealed three distinct patterns of cross-level interaction that demonstrate how factors across ecological levels work together to create connection opportunities or barriers, suggesting that effective prevention approaches must address environmental conditions simultaneously across multiple levels rather than focusing on isolated factors.

The three interaction patterns we identified demonstrate that traditional approaches focusing on single ecological levels may miss the synergistic effects that occur when factors work together. While previous research has identified factors at different ecological levels that influence social connection (Meehan et al. Reference Meehan, Clare, Grunseit and Merom2025; Ottoni et al. Reference Ottoni, Winters and Sims-Gould2022), our current findings reveal the mechanisms through which these factors work together, providing crucial insights for intervention development. Furthermore, our findings demonstrate how individual-level characteristics interact with community resources and interpersonal relationships to determine connection outcomes, extending understanding of how environmental factors can mitigate individual-level vulnerabilities. Participants described how personality traits such as introversion, traditionally viewed as individual-level risk factors for social isolation, could be successfully accommodated through specific combinations of community infrastructure and interpersonal facilitation.

The concept of ‘passive’ social connection through community spaces like shopping centres provides important insights into how built environments can serve diverse personality types and connection preferences. This extends research on public third places by revealing how these spaces function differently for individuals with varying social confidence levels (Finlay et al. Reference Finlay, Esposito, Kim, Gomez-Lopez and Clarke2019). Rather than requiring active social engagement, these environments enabled ambient sociability that provided belonging without social pressure.

Equally significant was participants’ identification of ‘connection catalysts’ describing extroverted community members who naturally facilitated connections for others. This interpersonal bridging function represents a crucial mechanism through which individual-level vulnerabilities can be overcome through community-embedded social relationships. This finding parallels research on social prescribing approaches that connect isolated individuals to community resources through link workers (Abel et al. Reference Abel, Kingston, Scally, Hartnoll, Hannam, Thomson-Moore and Kellehear2018), suggesting that naturally occurring social dynamics could inform formal intervention design. Programmes such as Groups 4 Health, which build capability for individuals to engage in community activities (Haslam et al. Reference Haslam, Cruwys, Chang, Bentley, Haslam, Dingle and Jetten2019), might be enhanced by incorporating these natural bridging mechanisms.

Digital technology exemplified complex interactions across all four ecological levels, revealing why technology interventions often fail when focused on single levels alone. Our findings extend understanding of digital inclusion by demonstrating how individual digital literacy, interpersonal connections, community support systems and societal infrastructure expectations interact to determine technology’s role in social connection.

At the individual level, digital literacy determined basic access to technology-mediated connection opportunities, consistent with existing research on digital divides among older adults. However, our findings reveal that community-level support through local organizations providing digital education represents a crucial mediating factor that enables individual engagement. This aligns with research emphasizing the importance of community-based digital inclusion approaches while providing specific evidence of how such support operates in practice. Karmann et al. (Reference Karmann, Handlovsky, Moullec, Frohlich, Hébert and Ferlatte2024) similarly emphasize the importance of addressing these nuanced cross-level interactions with digital technologies in developing effective public health approaches to enhance social connection among older populations. They found that during the Covid-19 pandemic digital platforms provided crucial social connections during isolation; however, they also intensified feelings of being ‘left behind’ among those with limited digital literacy or access. Further to our results, the interpersonal level demonstrated technology’s capacity to maintain family connections across geographic distance, while community-level platforms extended neighbourhood boundaries through local Facebook groups. At the societal level, widespread digital expectations created inclusion pressures that could marginalize those without access. This multi-level analysis explains why individual-focused digital literacy training alone often fails to achieve meaningful inclusion, supporting arguments for comprehensive approaches that address infrastructure, community support and societal expectations simultaneously.

The third interaction pattern explored in this article revealed how societal-level policies create enabling conditions for community infrastructure, which then provides opportunities for individual participation based on personal interests and preferences. This cascade effect demonstrates the importance of policy investments in creating environmental conditions that support and sustain social connection across diverse populations. Participants described how government policies at local and regional levels provided foundations for community facilities that could accommodate varied individual interests and preferences. The diversity of activities available within sustainably funded community centres, from exercise classes to cooking and singing groups, illustrates how societal investments can create environments that serve different personality types and interests simultaneously.

This finding extends research on age-friendly community policies (Buffel et al. Reference Buffel, Phillipson and Scharf2012), providing evidence of how policy intentions translate into individual connection outcomes through community-level implementation. Our findings suggest that age-friendly urban planning should prioritize both physical designs that facilitate chance encounters (cul-de-sacs, pedestrian-oriented main streets) and social infrastructure that supports sustained interaction (community facilities, local businesses). The findings align with research by Kingham et al. (Reference Kingham, Curl and Banwell2020) demonstrating how reduced traffic flow transforms streets into de facto public third places where neighbourly interaction flourishes. Similarly, participants’ emphasis on ‘main streets’ with local businesses and outdoor seating areas reflects research by Pendola and Gen (Reference Pendola and Gen2008) on how traditional commercial streetscapes foster a sense of community through regular, informal encounters. The cascade from policy frameworks to physical infrastructure to individual participation demonstrates why effective social connection interventions require coordination across multiple ecological levels and stakeholder groups.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, while our analytical approach primarily conceptualized community within geographical boundaries surrounding participants’ residences, our findings revealed more complex understandings of community that transcend physical space. Participants described meaningful communities of interest that spanned geographic boundaries, particularly through digital platforms that enabled connection with physically distant others while simultaneously strengthening relationships with local residents. This reflects observations by Irwin (Reference Irwin and Abrutyn2016) that community has become increasingly complex in the digital age, with overlapping and fluid boundaries that challenge traditional place-based definitions. Future research should more explicitly engage with these evolving conceptualizations of community that accommodate both place-based and interest-based social connections.

Second, the significant gender imbalance in our sample (12 women, 3 men) limits our ability to draw robust conclusions about gendered experiences of social connection especially given that participants themselves identified substantial differences in how men and women approach social connection, with men reportedly preferring shoulder-to-shoulder connection through shared activities rather than face-to-face conversation. These preliminary observations align with broader literature on gender differences in social connection strategies (Fragoso et al. Reference Fragoso, Ricardo, Tavares and Coelho2014), but require further investigation with a more balanced sample and potentially different data collection techniques. This limitation also reflects a common challenge in recruiting older men to research (Bracken et al. Reference Bracken, Askie, Keech, Hague and Wittert2019), potentially reinforcing the very patterns of male disconnection that participants described. Future research may employ more ‘shoulder-to-shoulder’ activity-based discussions, to involve men, where they may discuss while engaging in a hobby or task. This is akin to previous work which found that task-based discussions can be an appropriate way to engage people in a more meaningful way (Colucci Reference Colucci2007).

Third, several methodological limitations warrant consideration. The small sample size (n = 15) across four localities limits the generalizability of our findings, particularly regarding metropolitan versus regional comparisons, which should be interpreted with caution. However, our findings do provide experiential validation for factors previously identified in quantitative research (Meehan et al. Reference Meehan, Clare, Grunseit and Merom2025, Reference Meehan, Grunseit, Condie, HaGani and Merom2023), including the importance of public third places, digital technology and community atmosphere. More importantly, by exploring these factors through community-level discussions, we illuminate the mechanisms through which they influence connection experiences, revealing not just what matters but why it matters in older adults’ everyday lives.

Identifying cross-level interactions presents inherent interpretive challenges, as determining whether factors operate independently or through complex interactions relies on researcher judgement in categorizing participant experiences across ecological levels. While our findings suggest potential intervention targets through identified environmental factors and interaction patterns, they do not provide evidence of intervention effectiveness.

Implications for research, policy and practice

This study extends understanding of social-ecological approaches to social connection among older adults, building upon established research by revealing how factors across ecological levels interact dynamically to shape connection experiences. The identification of three distinct cross-level interaction patterns provides important insights for prevention-focused intervention development. Future research should build on these findings in several ways. First, longitudinal studies could explore how cross-level interactions evolve over time, particularly around key life transitions identified as vulnerability points for disconnection (retirement, widowhood, health declines). Second, intervention research should test whether addressing the specific interaction patterns identified, such as personality traits with community infrastructure and interpersonal bridges, digital technology across multiple levels and policy–community–individual cascades, produce better connection outcomes than single-level approaches. This may be done using multi-arm designs to assess the effectiveness of interaction-focused versus traditional interventions. Third, while our participants effectively engaged with the social-ecological framework when supported by visual aids and facilitator guidance, future research should examine whether cross-level interaction patterns operate similarly across diverse cultural contexts and whether alternative frameworks might better capture these dynamic relationships in different settings.

Our findings suggest important considerations for policy development across multiple domains, though these recommendations require validation through larger-scale research. In urban planning, the identification of specific design elements that facilitate cross-level interactions, like main streets, local business clusters and community-friendly geographic features, suggests that policies mandating inclusion of these elements in new developments could create physical infrastructure enabling the connection processes participants described. However, such approaches would require overcoming growth-focused development rhetoric to prioritize community wellbeing (Ríos-Ocampo and Gary Reference Ríos-Ocampo and Gary2025). In economic development, policies that support small, locally owned businesses may help preserve the community nodes that participants identified as crucial for both passive and active connection, particularly given their role in enabling interpersonal bridging relationships (Izenberg and Fullilove Reference Izenberg and Fullilove2016). In transportation, public transit routes and schedules aligned with community activities could reduce accessibility barriers that prevent the cross-level interactions necessary for social participation, particularly in metropolitan areas where transport emerged as an enabling factor (Reinhard et al. Reference Reinhard, Courtin, Van Lenthe and Avendano2018). Critically, our findings suggest that policy approaches should consider how interventions across different domains can work together to support the interaction patterns that facilitate connection.

For practitioners, our findings suggest several promising approaches for developing prevention-focused interventions that leverage cross-level interactions. The identification of ‘connection catalysts’ and their role in bridging individual vulnerabilities with community resources suggests opportunities for programmes that train and support natural community connectors, extending social prescribing approaches to incorporate peer mentoring and community relationship facilitation (Abel et al. Reference Abel, Kingston, Scally, Hartnoll, Hannam, Thomson-Moore and Kellehear2018). Digital inclusion programmes could be enhanced by addressing the multi-level nature of digital connection, combining individual skills development with community-level support systems and advocacy for accessible digital infrastructure. The importance of physical infrastructure in enabling cross-level interactions suggests that community development approaches should integrate place-making with social programming to create environments where diverse personality types and connection preferences can be accommodated. Critically, our ecological perspective indicates that the most effective prevention approaches will simultaneously address the environmental conditions that enable cross-level interactions rather than focusing on individual behaviour change or environmental modifications in isolation.

Conclusion

By examining community and societal influences on social connection across diverse geographical and social contexts, we have identified three distinct patterns of cross-level interaction that demonstrate how environmental factors work dynamically with individual characteristics to create both barriers and opportunities for meaningful connection. Our findings challenge individualistic approaches to loneliness and social isolation by demonstrating how factors beyond personal control, from urban design and local business presence to digital infrastructure and transportation systems, profoundly shape older adults’ connection opportunities. The perspectives shared by participants highlight that effective responses to loneliness and social isolation must extend beyond individual-level interventions and address the broader social and physical environments that enable or constrain connection possibilities. As populations age globally and loneliness receives increasing recognition as a public health priority, social-ecological approaches represent an important pathway towards creating communities where older adults can maintain meaningful social connections throughout later life. Future research and policy development should build upon these insights to create multi-level interventions that leverage cross-level interactions to support ageing in place through enhanced social connectedness.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X25100457.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the participants who took the time to participate in this study, sharing their perceptions and experiences. We would also like to acknowledge the community organizations who got on board and helped us to spread the word about this research.

Financial support

No external funding was obtained for this research.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval for this project was obtained from the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethic Committee (approval number H15985 issued on 15 May 2024). Written consent was collected at the venue before the commencement of the focus groups by the lead researcher. The lead researcher was trained in mental first aid to ensure that any distress felt by the participants owing to the sensitive nature of the topics covered was identified and dealt with appropriately.