Intraspinal teratoma is a rare spinal cord tumor (0.2–0.5% of spinal tumors) and exceedingly uncommon in adults. Reference Arora, Chumber and Vani1,Reference Ariñez Barahona, Navarro Olvera and Esqueda Liquidano2 Most adult intramedullary teratomas are located in the thoracolumbar region and conus medullaris. Reference Arora, Chumber and Vani1,Reference Ak, Ulu, Sar, Albayram, Aydin and Uzan3 The clinical presentation is usually non-specific, most frequently including back pain and lower limb weakness and numbness due to mass effect and compression of the cauda equina nerve roots. Reference Arora, Chumber and Vani1 Histologically, teratomas comprise elements from all three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm) and thus often contain adipose tissues, calcifications, glandular tissues, hair follicles and epithelia. They are classified as mature, immature or malignant based on tissue differentiation. Reference Jeong, Park and Jun4,Reference de Oliveira, Guirado, Yamaki and Frasseto5 On MRI, mature cystic teratomas show heterogenous signal intensity with a mixture of fatty tissue, cystic and solid components located within the thecal sac. Reference Ariñez Barahona, Navarro Olvera and Esqueda Liquidano2,Reference Jeong, Park and Jun4,Reference Keykhosravi, Tavallaii and Rezaee6 The presence of intralesional fat and the location are considered the key diagnostic clue. Reference Ariñez Barahona, Navarro Olvera and Esqueda Liquidano2,Reference Jeong, Park and Jun4 Spinal teratomas may also be associated with congenital spinal dysraphism such as tethered cord and spina bifida. Reference Ak, Ulu, Sar, Albayram, Aydin and Uzan3,Reference Jeong, Park and Jun4 The main differential diagnosis includes dermoid cyst and atypical schwannoma. Reference Jeong, Park and Jun4 Complete surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment; however, radical resection may be limited by adherence to adjacent structures. Reference Arora, Chumber and Vani1,Reference Ariñez Barahona, Navarro Olvera and Esqueda Liquidano2,Reference Jeong, Park and Jun4 As such, subtotal excision is performed to minimize the neurological deficits, particularly given the benign nature of this lesion. Reference Ak, Ulu, Sar, Albayram, Aydin and Uzan3,Reference Jeong, Park and Jun4

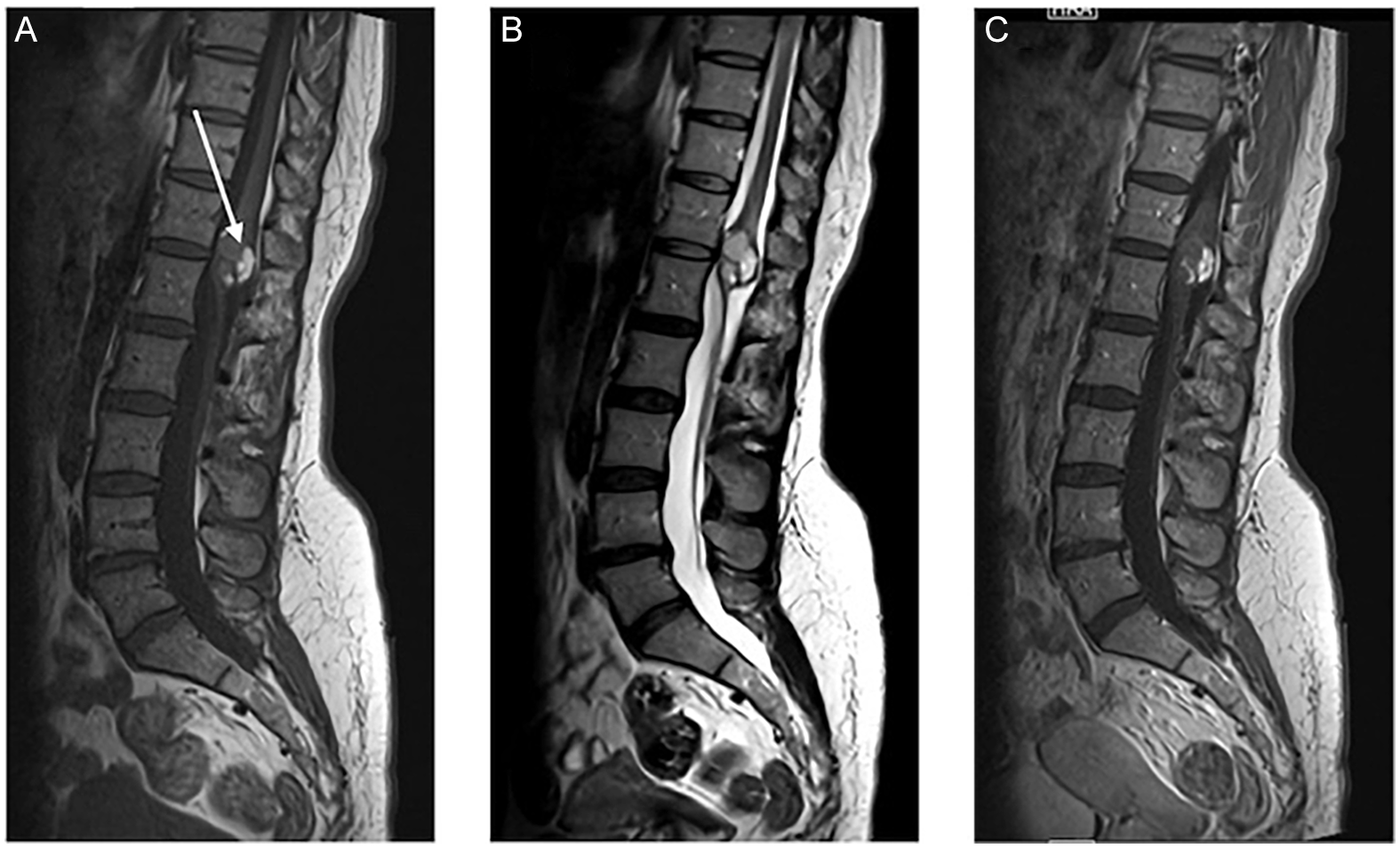

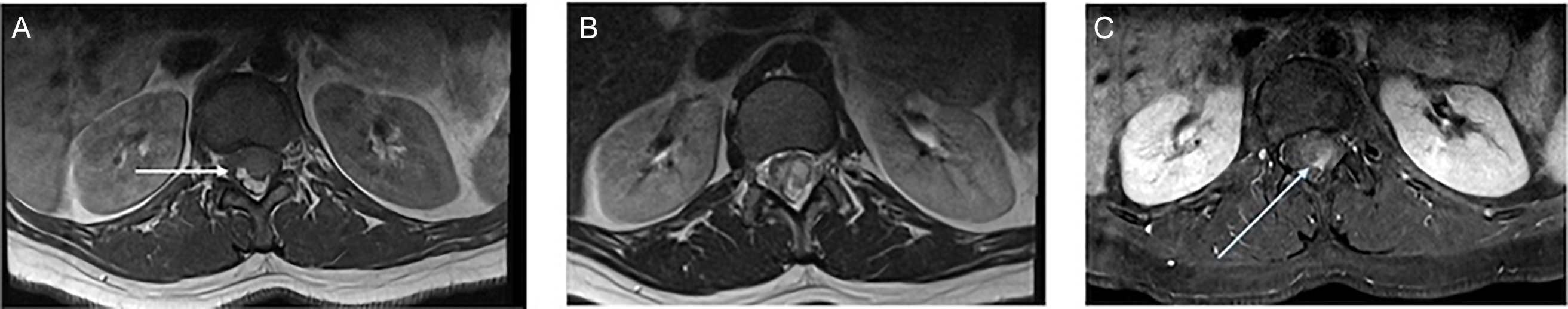

We report a case of a 39-year-old woman who presented with a long-standing history of back pain worsening over the past year, associated with progressive lower limb numbness and radicular pain. She also reported urinary urgency and anal sphincter control issues associated with intermittent urinary and bowel incontinence. There was no saddle anesthesia. On clinical examination, the power and sensation of the bilateral lower limbs were intact. The reflexes were brisker than the average response (3+), more pronounced on the left and associated with clonus. The plantar reflex was down-going bilaterally. The anal sphincter tone was reduced. Lumbosacral spine MRI was performed and showed a 2.7 cm expansile intramedullary well-defined conus medullaris lesion at the T12–L1 level that demonstrated intralesional high T1 signal intensity, consistent with fat components (Figures 1A, 2A and 2C), along with cystic and solid enhancing components (Figures 1C and 2C). There was resultant severe spinal canal stenosis and peripheral displacement of cauda equina nerve roots (Figures 1B and 2B). There was no associated tethered cord or spina bifida. The patient underwent T12–L1 posterior decompression and laminoplasty for resection of the conus medullaris lesion. Near-total excision was achieved without significant postoperative complications. Postoperatively, the patient was walking independently. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of mature benign cystic teratoma. On follow-up, her lower limb radicular pain and numbness improved. Sphincter control issues persisted, essentially unchanged from the preoperative period. There were no new or progressive neurological deficits. The patient was referred for spinal cord rehabilitation.

Figure 1. MRI of the lumbar spine (A), (B) and (C) sagittal T1, T2 and T1 post-Gad shows a well-defined intramedullary lesion involving the conus medullaris at the T12–L1 level. There is an intrinsic T1 signal intensity (white arrows), consistent with macroscopic fat. There is a cystic non-enhancing component.

Figure 2. MRI lumbar spine (A), (B) and (C) axial T1, T2 and T1 post-Gad FAT SAT demonstrate again the fatty component of the lesion, which is suppressed in FAT SAT images (white arrows). Small enhancing solid focus seen in post-contrast images (blue arrows). There was resultant severe spinal canal stenosis. No evidence of tethered cord or spinal dysraphism (not shown).

In summary, we present a rare case of intramedullary spinal cord mature cystic teratoma in an adult. Although most of the spinal cord teratomas are congenital and present early in neonates or early childhood, few cases of adult spinal cord teratomas are reported in the literature. The clinician and radiologists should be familiar with this entity and its characteristic imaging findings.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient and his family for granting permission to publish this case report.

Author contributions

DG had direct clinical contact with the patient and documented the case. AH and EW completed the background literature review. AH was the primary author of the manuscript and submission. EW provided invaluable expertise in the refinement of the manuscript and was instrumental in the review process. All authors collaborated on the composition of the manuscript text.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

AH: None. EW: None. DG: None

Ethical statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.