1 Introduction

This Element describes early Chinese views of the mind and how it relates to the psychology of a whole person. In particular, it examines differing early views on the relation of the mind or heart-mind (xin 心) to affective and cognitive faculties, and to the spirit (shén 神) and the embodied person (shēn 身). A distinctive feature of Chinese philosophy is its recognition of the importance of the body and emotions in extensive and diverse self-cultivation traditions. It thus contrasts with Western philosophical debates about the relationship between mind and body, which are often described in terms of mind-body dualism. Questions of how our bodies relate to our minds or spirits are of central importance to several humanistic and scientific disciplines. The problem of mind–body dualism is central to the history of philosophy and religion; and recent work in cognitive and neuroscience underscores the importance of somatic experience for how we think and feel.Footnote 1

There are multiple varieties of dualism, as well as multiple mind–body problems. For example, the term dualism refers to claims that, for a given domain, there are two fundamental kinds or categories of things or principles (e.g., Good and Evil in theology), in contrast to monism: the theory that there is only one fundamental principle, kind, or category of thing. (It also contrasts with pluralism: the view that there are many kinds or principles, kinds or categories.) In philosophy of mind, dualism refers to the theory that the mental and physical, or mind and body (including the brain) are composed of metaphysically different kinds of entities in that the former are nonmaterial and the latter material. The mind-body problem refers to problems of the relationship between mind and body, or between the mental and the physical. It includes: the ontological problem of distinguishing mental states from physical states and the nature of their relationship; causal questions of their mutual influence (if any); and related issues involving the nature of consciousness, intentionality, the self, and so on (Robinson Reference Robinson2017). I will focus on two of these: the (non)materiality of the mind and the relation between mental and physical states.

Parts of the Element summarize, in much compressed form, earlier research on the relation of body, mind, and spirit in early China (Raphals Reference Raphals2023). This Element differs from that earlier research in several ways. Most importantly, it focuses on the role of what in contemporary terms are called embodiment and embodied cognition (these terms are discussed in Section 5) in the philosophical traditions of early China. In addition, it offers brief comparative observations on the (perhaps, to some) surprising importance of embodied cognition in the world of ancient and Classical Greece.

1.1 Mind–Body Dualism and Its Problems

Mind–body dualism has become an important issue in Chinese and comparative philosophy because of claims that Chinese thought is in some sense “holist.” There are various versions of this view. One is the claim that there was no mind–body dualism in early China; another takes the form of contrasts between supposed Chinese holism and “Western” dualism. These holist views tend to minimize distinctions between body and mind and spirit by reducing all three to material or quasi-material substances, often identified with qi 氣.Footnote 2 Dualist views – in the sense of mind–body dualism – have been historically Eurocentric. However, recent claims for concepts of mind–body dualism in early China argue against the holist position in a Chinese context. Arguments for mind–body dualism in a Chinese context make the claim that are part of a broader critique of a “neo-Orientalist” tendency to portray Chinese and Western thought as radically different. In particular, a series of studies by Edward Slingerland (Slingerland Reference Slingerland2013, Reference Slingerland and Tan2016, Reference Slingerland2019) argue against claims that early China had no concept of mind–body dualism. This debate has led to renewed interest in the role of mind–body interactions in early Chinese thought. However, in a Chinese context, the “mind–body” binary encounters a problem: namely, the very important role of “spirit” (shén) and its relation to the mind.

In this Element I argue that there was an important divergence in early China between two views of the self. I begin with evidence that in early China there were two very different views of a person, understood as composed of body, mind, and spirit. In one, which can be called a mind-centered view, mind and spirit are closely aligned, and are understood to rule the body as a ruler rules a state or populace, in a hierarchically superior relation to the body. A polarity between body and mind/spirit (xin/shén) implies that mind and spirit are distinct from the body (for example, by being composed of a more refined kind of qi than the rest of the body). We see this view in the Analects, Mengzi, Xunzi, and tests excavated from Guodian. This view is very compatible with Eurocentric mind–body dualism.

In a very different spirit-centered view, all three were distinct, often with pride of place given to spirit over mind. In this view, the person is tripartite, and mind and spirit are independent entities that cannot be reduced to a material–non-material binary. In some cases body and spirit are even aligned in opposition to mind. This spirit-centered view rejects the hegemony of mind and gives pride of place to spirit, sometimes in alliance with the body. Examples occur in the “Inner Workings” chapter of the Guanzi, the Zhuangzi, texts excavated from Mawangdui 馬王堆, and the Huainanzi.

1.1.1 Care of the Self

Several important studies have contributed to new understandings of the relations of body, mind, and spirit in early China. Some approaches discuss something analogous to what Foucault has called “the care of the self,” better understood in a Chinese context as “self-cultivation” (xiushēn 修身) or “nurturing life” (yangsheng 養生). Self-cultivation traditions fundamentally involve the care and preservation of body, mind and spirit, but often disagree about relations between them. Some recent studies emphasize the importance of embodied self-cultivation traditions, from very different points of view.Footnote 3

Michael Puett argues for a fundamental change in Chinese understandings of the relation between humans and gods, beginning in the fourth century BCE. At this time, critics of court sacrificial practices argued that humans could use self-cultivation practices to appropriate the powers of spirits, in effect to “become” spirits. As a result, the term shén – spirit(s) – came to include not only extrahuman spirits with powers over natural phenomena but also “spirit” capacities within humans, achieved through the refinement of qi within humans (Puett Reference Puett2002: 21–23, 80–224).

Why did Warring States thinkers begin to claim that they could “become” spirits? According to Puett, Bronze Age attitudes toward spirits were fundamentally agonistic because spirits were capricious; sacrificial rituals were used to control them by transforming ancestors into gods in a divine hierarchy that was amenable to human manipulation through prayer and sacrifice (Puett Reference Puett2002: 31–79, cf. Keightley Reference Keightley1978, Reference Keightley1998; Poo Reference Poo1998). Warring States thinkers argued against these attitudes and effectively used the self-cultivation practices they advocated to reduce the distance between humans and gods. Such “self-divinization” practices increased individual human control and reduced the importance of divination and sacrifice.Footnote 4

In a very different approach to self-cultivation, Edward Slingerland argues for the centrality of wuwei 無為 or “acting without acting” as a spiritual ideal for thinkers as diverse as Confucius, Mengzi, the authors of the Daodejing, Zhuangzi, and Xunzi. Slingerland describes wuwei as both a mental state (characterized by effortlessness and lack of self-consciousness) and a mode of efficacious action (efficacious because it is in accord with the normative order of the cosmos) (Slingerland Reference Slingerland2003b: 5, 7, 29–33). He considers wuwei central to a worldview in which the cosmos has a normative order, but humans have fallen away from their proper roles and modes of behavior. A person who has regained this original state through wuwei acquires power or charismatic virtue (de 德), but, paradoxically, “effortless action” can only be accomplished through self-cultivation characterized by the need to “try not to try.”

Mark Csikszentmihalyi uses the Mengzi and two versions of the Wuxing 五行 (“Five Kinds of Action”) recovered from Guodian 郭店 and Mawangdui 馬王堆 (Changsha, Hunan, c.168 BCE) to argue for what he calls a “material virtue” tradition: a detailed moral psychology that describes procedures for the cultivation of virtue(s) (Csikszentmihalyi Reference Csikszentmihalyi2005: 7). In particular, they describe virtues in terms similar to bodily humors. Csikszentmihalyi argues these texts describe sagehood in terms of material virtue; and that this “material virtue” tradition was a Ru (“Confucian”) response to criticisms of the adequacy of “archaic” rituals for self-cultivation or the creation of social order.

In this material virtue tradition, virtue was grounded in the transformation of qi. It manifested physically in the body, and was inseparable from it. Cultivation of the virtues transforms the body and its appearance: it manifests in a jadelike countenance and the appearance of the eyes. This view of qi draws on late Warring States physiognomy and medicine. Medical and physiognomic texts share the view that internal qi is reflected in appearance and makes it possible to judge character or potential. In economic and military contexts this meant judging the “character” of an animal or weapon. Excavated texts show the importance of physiognomy in practical contexts. Examples include a text from Yinqueshan on the physiognomizing of dogs, a Han sword physiognomy text from Juyan and a text on the physiognomy of horses from Mawangdui.

These ethically normative self-cultivation traditions are important for several reasons. All involve body, mind, and spirit, often not clearly distinguished or explicitly blended. They provide strong expressions of “individualism” in early China, insofar as only an individual can perform self-cultivation (xiushēn) or “nurture life” (yangsheng). Only individuals can “xiu” their “shēn” or “yang” their “sheng.” Most important for the purposes of this Element, they all involve knowledge that is embodied in the immediate sense that it is gained through physical practices. These approaches thus place the study of the body squarely within the purview of ethics. (A full account of issues of individualism is beyond the scope of the present discussion. See Brindley Reference Brindley2010.)

1.1.2 Arguments for Dualism

Several recent studies have argued for the importance of dualist views in early China (Graham Reference Graham1989: 25, cf. Goldin Reference Goldin and Cook2003: 232, 243n22). Paul Goldin argued for the presence of mind–body dualism several of the most philosophically important Warring States texts. He points to passages in the Zhuangzi that seem to suggest the possibility of an immaterial mind or spirit, a passage in the Xunzi that presents a contrast between bodily and mental state, and Chinese beliefs about ghosts and postmortem consciousness (Goldin Reference Goldin and Cook2003: 228, 231, Reference Goldin and Richard2015).

In a recent monograph and several shorter studies, Edward Slingerland argues forcefully for the presence and importance of dualism in early China, and considers mind–body dualism to be one of several reductionist “Chinese-Western” dichotomies (Western dualism vs Chinese holism, Slingerland and Chudek Reference Slingerland and Chudek2011; critique by Klein and Klein 2012). Slingerland (Reference Slingerland2013: 9–15) argues against what he takes as the strongly holist positions of Roger Ames (Reference Ames1984, Reference Ames, Kasulis, Ames and Dissanayake1993), François Jullien (Reference Jullien2007: 8, 69), and Herbert Fingarette (Reference Fingarette1972, Reference Fingarette and Jones2008), among others. He argues for “weak” mind–body dualism, both in early China and as a psychological universal. He argues that in Chinese weak mind–body dualism, mind and body are experienced as functionally and qualitatively distinct, although potentially overlapping at points (Slingerland Reference Slingerland2013: 28).

Slingerland’s arguments also draw heavily on longstanding Chinese beliefs about the status of the soul after death. Chinese belief in some form of consciousness of the dead dates to the Shang oracle bone inscriptions; and Slingerland argues that, despite earlier evidence of belief in continuity between the world of the living and the dead, in late Warring States views of the afterlife, the dead were viewed as categorically different from the living (Guo Reference Guo, Olberding and Ivanhoe2011: 85–87; G. Lai Reference Lai2005: 42; Slingerland Reference Slingerland2019: 66–75).

He further argues that pre-Qin writers described the heart-mind or xin as the locus of personal identity, thought, free will, and moral responsibility, and as qualitatively different from other parts of the self (Slingerland Reference Slingerland2019: 101). Finally, he argues that soul–body dualism was strongly developed by the third century BCE, including detailed accounts of ritual and religious techniques for freeing the mind/spirit from the body.Footnote 5

Finally, Slingerland argues that any tripartite or multipartite account of the constituents of a person are “parasitic” on mind-body dualism because they all require the separability of personal essence from the physical body. (It also requires a close association between shén and the cognitive functions of xin.) He concludes that “if there is a unifying feature behind this diversity of terminology and divisions, it is that the soul … is intimately bound up with consciousness or mind” (Slingerland Reference Slingerland2019: 90). He argues that the unifying thread in a complex range of accounts of body-soul relations is

a bipartite division between the dumb, concrete vessel that is the physical body and then a thing or collection of things that fill or inhabit this vessel. The latter serve as the locus/ loci of consciousness, intention, and personal identity. In other words, soul-body dualism (or tripartite-ism, decipartite-ism, etc.) is fundamentally parasitic on mind- body dualism.

A dualist account of early Chinese psychology faces several problems. First, Chinese dualist arguments set up a problematic “body–mind” binary that conflates “mind–body” dualism and “spirit–body” dualism into one material–non-material binary that is historically Eurocentric. Second, most studies of mind–body dualism in early China are either not comparative or anachronistically compare early Chinese texts with modern European philosophers. Third, a dualist framework accounts for some of Chinese texts, but excludes others. Most broadly Confucian texts tend to identify the heart-mind with spirit and are thus friendly to this framework of analysis. But others present very separate roles of “mind” and “spirit.”

Finally, the dualist position and the comparative “mind–body dualism” debate on which it draws rely on Western conceptual categories based on a Western “mind–body” binary. Most studies of “mind–body dualism” in early China collapse mind and spirit into one entity, which can be dualistically contrasted to the body, for example, in metaphors of the heart-mind as ruler of the body. Others tacitly equate mind–body dualism during life with body–spirit dualism after death, and result in alternating treatments of “mind–body” and “body–spirit” dualisms.

1.2 Mind- and Spirit-Centered Texts

None of these frameworks account for significant interactions between mind and spirit. A dualist framework of analysis loses important dimensions of the relations between mind (and its associated faculties) and spirit or soul (and its associated faculties), including how both relate to the body. I argue instead that Warring States texts present a broad divergence between two views of a tripartite relation between body, mind and spirit. One closely aligns mind and spirit, often in a hierarchically superior relation to the body; the other decouples spirit from mind, and at times even aligns body and spirit in opposition to mind.

The French Sinologist Catherine Despeux rejects dominant contemporary Western representations of persons as a dichotomy between body (corps) and mind (esprit), noting that questions of body and mind are typically the purview of philosophy, whereas the study of the psyche (psyché) is the purview of the disciplines of religion and even psychology. She understands the term shén as soul (l’âme, rather than “spirit”) and proposes a tripartite representation of a person consisting of body, mind, and soul (a view she attributes to Greek thought, Aristotle’s On the Soul especially):

It seems desirable to get out of this dichotomy to analyze the vision in ancient China, especially since Western ancient thought most often referred to the trilogy body/soul/mind [corps/âme/esprit] which accords well enough with the analysis of subject and its components in Chinese culture. The Chinese equivalents of xing for the body, shén for the soul and xin for the heart/mind are easily found in body/soul/spirit.

I argue that there is a broad divergence between two views of a tripartite relation between body, mind, and spirit in Warring States texts. A mind-centered view aligns mind and spirit in a hierarchically superior relation to the body. A spirit-centered view problematizes the relation between mind and spirit, and in some cases even aligns body and spirit in opposition to mind. In this tripartite model, the self or person is composed of body in several aspects (including the form (xing 形), frame (ti 體), and embodied person (shēn 身, all discussed in detail in Section 1.3), the mind or heart-mind (xin) and the spirit (shén).

The mind-centered view closely aligns the heart-mind and spirit in a hierarchically superior relation to the body; together, they rule the body as ruler rules the people or a state. The result is effectively a binary view of a person – consistent with mind-body dualism – in which there is a polarity between the body on the one hand and mind and spirit on the other. Views of the heart-mind as ruler of the body, senses, and emotions changed over time; and this view is most prominent in the Xunzi but also appears to varying degrees in the Guanzi, Mengzi, Huainanzi, and Huangdi neijing.

The spirit-centered view gives pride of place to spirit (shén), both as the animating force that makes life possible and as the source of sagacity. In strong versions of the spirit-centered view, spirit is distinct from, superior to, and even at odds with the heart-mind, often operating through the body. This view is especially prominent in the Zhuangzi and the Huainanzi.

1.3 The Chinese Semantic Field

The Chinese semantic field for body, mind, and spirit differs from the English. No one term corresponds to either English “body,” “mind,” or “spirit.” “Bodies” are described as frame (ti 體), form (xing 形), or embodied person (shēn 身). The term xin 心 or “heart-mind” refers to both the “mind” and the heart. The term shén 神 refers to both an internal capacity of humans and to “spirits,” in the sense of divine powers external to humans.

1.3.1 Bodies: Frames and Forms

As important studies by Nathan Sivin and Deborah Sommer have demonstrated, Chinese terms for body have important differences from the English lexicon. They identify four key terms: ti 體, the physical body; xing 形, its structural form; gong 躬, the ritual person; and shēn 身, the social and self-cultivated person (Sivin Reference Sivin1995, Sommer Reference Sommer2008).

The ti or frame referred to the concrete physical body, including its major parts – usually the four limbs (si ti 四體) – and its physical form. An example of ti comes from Mengzi (2A2), who clearly refers to the entire body when he attributes to Gaozi a view of the body (ti) in which

The will is the master of the qi; qi is what fills the frame. Where the will arrives, the qi comes after it. Therefore it is said; Take hold of your will and do not do violence to the qi.

夫志, 氣之帥也; 氣, 體之充也。夫志至焉, 氣次焉。故曰: 「持其志, 無暴其氣」。

By contrast, the xing 形 – literally form or shape – is visible, with clear boundaries, and refers to the body’s outline. It has nothing to do with a person as a whole; it is not conscious and has no personality or sense of self. There are important differences between frames and forms. Body frames involve relationships between wholes and parts; body forms involve relationships between inner and outer (Sommer Reference Sommer2008, which provides a detailed account of differences between ti, xing, and shēn).

Shēn refers to a body, person, or “embodied person,” both as a lived physical body and as a socially constructed personality. As lived in bodies, shēn can be measured in space (height) and time (lifespan). The physical boundaries of one shēn do not overlap those of another. As social constructions, shēn have characteristics such as status, personal identity, character, moral values, and experience. Shēn are self-aware and are the locus of inner reflection and self-cultivation. They are materially discrete, but socially permeable, and can absorb social attributes such as honor, disgrace, and so on (Sommer 2008).

Finally, the term ren 人 or “person” refers to the entire person, including the shēn, heart-mind, and spirit (Ames Reference Ames, Kasulis, Ames and Dissanayake1993).

1.3.2 The Heart-Mind

Most texts attribute consciousness and thought to the xin, a term that refers to the mind but also to the heart, located in the center of the chest (Y. Lo Reference Yuet-Keung, Chong, Tan and Ten2003). This term is especially difficult to translate, and there is no consensus whether to call it “mind” or “heart”; I use the perhaps awkward “heart-mind.” Several psychological attributes are associated with the heart-mind: will or intentions (zhi 志), knowledge or consciousness (zhi 知), desires (yu 欲), and thought or awareness (yi 意).

There are important differences between Chinese and Western understandings of heart and mind, and the cognitive linguist Ning Yu has argued that Chinese cultural conceptualizations of the heart or mind differ fundamentally from Western dualism, because the “heart” (xin) is understood as the central faculty of both affective and cognitive activity and also as the source of thought, feelings, and emotions. By contrast, modern Western philosophy asserts a dichotomy between reason and emotion in which thoughts and ideas are linked to a largely disembodied “mind” and desires and emotions with an embodied “heart” (N. Yu Reference Ning2007: 27–28, cf. Damasio Reference Damasio1994, Lakoff and Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999). By contrast, early Chinese philosophy understood “heart” and “mind” as one xin 心: “the core of affective and cognitive structure, conceived of as having the capacity for logical reasoning, rational understanding, moral will, intuitive imagination, and aesthetic feeling, unifying human will, desire, emotion, intuition, reason and thought” (N. Yu Reference Ning2007: 28).

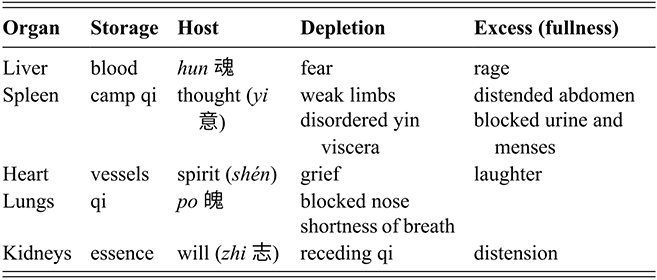

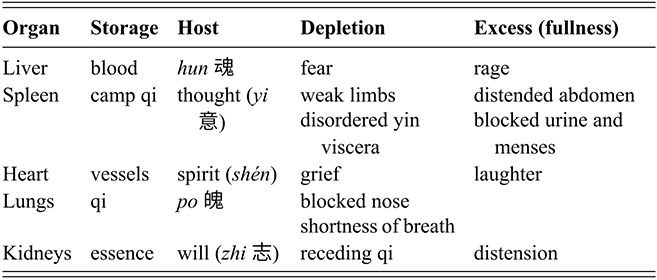

In mind-centered texts especially, the heart-mind was importantly considered the ruler of the body or the senses. In a major study of the body as an organization of space in early China, Mark Edward Lewis identifies two contrasting metaphors of the body as state. In “harmonious” body-state metaphors, the mind rules the state, and the body or senses are functionaries within it. By contrast, in “agonistic” metaphors, body components – including the senses and emotions – contest the heart-mind’s rulership (Lewis Reference Lewis2006: 37–39). These two metaphors provide two very different accounts of the heart-mind. The Huangdi neijing uses harmonious metaphors; here, the heart-mind is one of five yin “viscera” (zang 藏), and psychological functions are distributed harmoniously among the five. (The other four yin organs are the kidneys, liver, lungs, and spleen.) In the more prevalent agonistic metaphors, the mind asserts domination over the five sense organs – described as ministers or officials – who try to assert independence, and reject hierarchical control. This view appears in a wide range of Warring States and Western Han texts, including the Guanzi, Mengzi, and Xunzi. A potentially agonistic version of the metaphor appears in the text Wuxing 五行 (Five Kinds of Action), excavated from tombs at Mawangdui and Guodian. Here, the heart-mind rules the body as a ruler rules a state, and the senses are its servants or slaves.

A very different picture of the xin as heart appears in medical and recipe texts, which seem to have had different audiences and objectives than philosophical texts. Most describe xin straightforwardly as the heart, an organ in the center of the chest. For example, medical texts excavated from Mawangdui, Zhangjiashan 張家山 (Jingzhou, Hubei, 196–186 BCE), and Wuwei 武威 (Gansu, 25–220 CE) focus on description of ailments associated with the heart (xin) and spirit and accounts of therapies that involve them.

These medical passages treat xin in relative isolation, in contexts that are clearly diagnostic or therapeutic. Within these contexts, the absence of cosmological analogies or other theoretical content is not surprising. As in the multi-authored Greek Hippocratic corpus, treatises range considerably in content and audience from the clearly medical to the rhetorical, philosophical, and cosmological.

1.3.3 Spirits

Several terms with complex semantic fields refer to spirit or “soul” (shén 神). In its oldest uses, shén referred to extra- (or formerly) human entities, including ancestors, divine powers, and the inhabitants of mountains, lakes, and forests. These powers needed to be identified and placated. The term also came to be used of human beings of extraordinary sagacity who become “like” spirits. The term is also used of a “spirit” quality within humans that makes them “spirit-like.” In some medical contexts, spirit is one of the fundamental and necessary constituents of a living human being.

References to external, extra-human spirits begin with the oracle bone inscriptions. They appear repeatedly in the Book of Odes and Book of Rites, and, less frequently, in the Confucian Analects. Ritual texts – the Liji especially – address the role of sacrifice and other methods to achieve the presence of extra-human spirits. In Masters texts, discussions of spirit are divided between debates about the nature of extra-human shén, how humans should relate to them, and the nature and limits of their consciousness.

Starting in the fourth century, the view arose that individuals could store, enhance, and refine spirit internally. This internal spirit was closely linked to essence (jing) and qi. Importantly, it was independent of ritual relations with external spirits. Accounts of internal spirit are prominent in the Guanzi, Zhuangzi, and Xunzi, as well as in excavated texts from Mawangdui and Guodian. It is also prominent in medical texts as an important component of a person, which must be preserved and kept from harm. According to Puett, the term spirit was only applied to intra-human refined qi in the Warring States period, when the term’s meaning was redefined by ongoing debates about the nature of both spirits and spirit powers (Puett Reference Puett2002: 21–23). Advocates of new self-cultivation practices claimed that self-cultivation practices could offer spirit-like powers to humans, and thus tried to reduce the difference between spirits and humans.

Another meaning of shén, primarily in a medical context, is the animating force that maintains life in a living body. Living bodies are vivified by essence (jing), qi, and spirit, and when spirit leaves the body, it dies. For example, in the Huainanzi:

The form is the residence of life; qi is the origin of life; spirit is the governor of life. If [even] one loses its place, then [all] three are harmed.

夫形者, 生之所也; 氣者, 生之元也; 神者, 生之制也。一失位, 則三者傷矣. Huainanzi 1/9/15–16, Yuandao 原道)

2 Mind-Centered Texts

The mind-centered view has two separable components. One is claims for the hegemony of the mind over the body or the senses. The other is claims for correspondence or alliance between the heart-mind (xin) and internal spirit (shén), hand in hand with arguments for the importance of spirit. Mind-centered texts tend to recommend using self-cultivation procedures to enhance internal spirit within the body. They also identify internal spirit with virtue and with the heart-mind; and describe the heart-mind and spirit ruling the body as ruler rules the people or a state. They thus present a binary view of a person as a polarity between the body and the mind/spirit. These views developed over time, including the incorporation of spirit into the capabilities of the mind-ruler. This view is most prominent in the Analects, Mengzi, and Xunzi; and also appears in a range of texts that make body-state microcosm-macrocosm analogies, including some sections of the Guanzi and the Huangdi neijing. Although they fall short of a strict definition of mind-body or mind/spirit-body dualism, these mind-centered descriptions, including heart-mind as ruler metaphors, repeatedly draw contrasts between the body and mind and spirit.

2.1 The Analects And Mozi

The Analects of Confucius forms the backdrop for later views. It offers two interrelated views of the body. On the one hand, it stresses the importance of correct alignment for both ethical and political virtue. It also describes the correct alignment of the body as a key element of ritual conduct and a central element of the efficacy of ritual. The Analects has much to say about the body, the shēn person especially, but relatively little to say about mind or spirit. It combines a strong interest in ritual – for human purposes – with respectful distance from spirits, understood as external spirits rather than to human psychological capacities.

Confucius repeatedly describes ritual as a powerful technique for aligning the body correctly, and for aligning body and mind. For Confucius, ritual is inherently embodied, and would be incomprehensible otherwise. The Liji records a remark attributed to Confucius about things that don’t exist”:

Soundless music, disembodied ritual, and mourning without [mourning] clothes— these are what is called the three things that don’t exist.

無聲之樂, 無體之禮, 無服之喪, 此之謂三無

The Analects emphasizes the need for correct physical disposition of the shēn body as the basis for virtue and efficacious action. Analects 13.6 remarks:

If the person is correctly aligned, then there will be obedience without orders being given. If it is not correct, there will not be obedience even though orders are given.

其身正, 不令而行; 其身不正, 雖令不從 (Lunyu 13.6/34/13)Footnote 6

But what does it mean to be “aligned”? The term zheng is often translated as upright or “right” in the normative sense of being morally upright. But it can also refer to the correct alignment of physical objects. For example, in the Analects, zheng can also refer to aligning an object, including one’s own body. Thus, a “gentleman” or an exemplary person (junzi 君子) maintains a dignified appearance by straightening – which is to say, aligning – his robe and cap (20.2). He does not sit if his mat is not aligned correctly (buzheng 不正, 10.9), and aligns his mat before accepting a gift of meat (10.13). He is advised (8.4) to zheng yanse 正顏色 – literally to rectify his facial coloring – in order to encourage sincerity and trustworthiness in others. Finally, gentlemen associate with others who follow dao in order to be set right by them (1.14).

The notion of correct alignment also applies to government, for example, at 12.17: “To govern (zheng 政) means to align (zheng 正). If you set an example by [your own] alignment, who will dare not to be aligned?” (Lunyu 12.17/32/18). Finally, the sage-ruler Shun is described as governing, simply by aligning himself correctly to face south:

As for one who ruled by means of wuwei was it not Shun? How did he do it? He made himself reverent and aligned himself [in the ritually correct way] facing south, and that was all.

無為而治者, 其舜也與? 夫何為哉, 恭己正南面而已矣

These examples show how much importance Confucius attached to the body. Confucius repeatedly describes ritual as a powerful technique for aligning the body correctly and for aligning body and mind. (There are also close philological links between the terms for ritual (li 禮) and the ti 體 body.)

The Analects also underscores the importance of the body to virtuous conduct and ritual by the relative absence of accounts of the heart-mind. The term xin occurs only five times, and without reference to either bodies or spirits. Confucius speaks of his own xin in a famous account of his own development:

At fifteen, I set my will on learning. At thirty, I took my place. At forty, I had no doubts. At fifty, I understood the mandate of Heaven. At sixty, my ear was compliant. At seventy, I could follow the desires of my heart-mind (xin suo yu 心所欲) without going beyond the rule [the carpenter’s square].

His remark links the heart-mind to desires. Another passage links the heart-mind to virtue, describing Yan Hui as capable of spending three months with “nothing in his heart-mind but humaneness” (6.7/12/19).

References to shén in the Analects clearly denote external spirits, rather than human psychological capacities. Confucius is famously reticent about spirits, and “does not discuss prodigies, feats of strength, disorderly chaos or spirits” (7.21). He goes further and defines the virtue of wisdom as an attitude in which one “respects spirits but keeps them at a distance” (6.22). These remarks are clear that humans should not engage with spirit powers or try to influence them. As Puett puts it, the purpose of ritual should be not to influence spirits but to cultivate ourselves. We should revere spirits, but the best way to revere them is not to try to influence them (Puett Reference Puett2002: 98).

In summary, the Analects has much to say about the embodied person, but little to say about the heart-mind and either spirits or spirit capacities. He combines a strong interest in ritual – for human purposes – with respectful distance from spirits.

Early and late Mohist treatments of body, mind, and spirit differ considerably. Early Mohist texts discuss spirits at length; by contrast, the epistemological chapters engage in definitions of key terms.Footnote 7

In strong contrast to the Analects, the term xin occurs over fifty times in the Mozi. Sometimes, it refers to affective states, such “not having a peaceful heart-mind” (wu an xin 無安心, 1.1/1/10) or “having no remorse in one’s heart-mind” (wu yuan xin 無怨心, 1.1/1/12). Other passages use the term xin to refer to a cognitive faculty, often attributed to a superior person or junzi. For example, superior persons ensure that destructive thoughts and impulses are not present in their heart-minds (wu cun zhi xin 無存之心 , Mozi 1.2/2/14, ch. 2). The same chapter links a superior person’s wisdom to a mental faculty of discrimination: “For those who are intelligent, their heart-minds make distinctions” (hui zhe xin bian 慧者心辯, Mozi 1.2/3/2, ch. 2). Thus, although the heart-mind can be an affective faculty that feels peace, grief, etc., the Mozi also describes the heart-mind as an explicitly cognitive faculty that discriminates and thinks.

The early Mohist chapters include extensive discussion of external spirits and postmortem consciousness in accounts of “ghosts and spirits” (guishen 鬼神). These discussions focused on three issues concerning ghosts and spirits: whether they existed, whether they had consciousness (ming 明), and extended critiques of Ru attitudes and practices toward them. Three chapters titled “Explaining Ghosts” (Minggui 明鬼, 29–31) present examples of interactions between humans and spirits, and demonstrated human shortcomings.Footnote 8 The early Mohists believed that spirits were conscious, had foreknowledge of human actions, and could reward the worthy and punish the unworthy. These beliefs helped promote order in the world:

Now, if we could persuade the people under Heaven to believe that ghosts and spirits are capable of rewarding the worthy and punishing the wicked, then how could there ever be disorder in the world?

偕若信鬼神之能賞賢而罰暴也, 則夫天下豈亂哉!

Several definitions in the Mohist epistemological chapters describe how bodies and minds were constituted. The dialectical chapters define ti as limbs or “parts” in contrast to wholes. They define life as holding together the intelligence and physical form.Footnote 9 Here, intelligence and physical form are distinct entities that share a location in space, and both are prerequisites for life in a human being.

The text does not explore the logical implications of this coexistence in physical space, nor does it address the question of what happens to the body-intelligence composite after death, when the intelligence is no longer bound to the physical form. Finally, the passage identifies life as the coexistence, suggesting that the mind cannot survive the body, and the body requires the heart-mind to be alive.

2.2 The Mengzi

The mind-centered view first becomes prominent in the Mengzi (also known as the Mencius). It emphasizes the importance of the heart-mind – including its role as the ruler of the body and senses – and considers spirit as a capacity beyond even sagacity. These two views inform Mencian understandings of the body.

Mencius repeatedly refers to the heart-mind. He links it to virtue in his account of the four “sprouts” of virtue and considers it the “greatest” part of a person. It is also central to his account of self-cultivation by the refinement of qi. At 2A2 Mengzi claims to have attained an “unperturbed mind” (budongxin 不動心) at the age of forty; and describes qi as filling the frame of the body, commanded by the will: “The will is the commander of the qi; qi is what fills the frame.”Footnote 10

Mengzi goes on to describe the body as a container: filled by “flood-like qi” and containing the heart-mind. The container is permeable: qi can enter the body and emanate from it without loss. An aspect of that permeability is the body’s “transparency.” When a person is “upright within the breast” (xiong zhong zheng 胸中正), the pupils of the eye are clear and bright (4A15). The virtue of exemplary persons manifests in their limbs and coloring (7A21).

Unlike the Guanzi, which links qi with essence and spirit (discussed in Section 3.1), Mengzi does not discuss essence (jing). Mengzi describes the body as filled with flood-like qi and containing the heart-mind. Mengzi also describes the body as transparent in the sense that the state of the heart-mind is visible in the appearance of the body. If a person is internally upright, the pupils of the eye are clear and bright (4A15, 7.15/38/14–15). According to 7A21, an exemplary person’s true nature – humaneness, rightness, the rites and wisdom – is rooted in the heart-mind but manifests in his coloration by giving the face a sleek appearance and is also visible in the back and limbs (Mengzi 13.21/69/14–15).

2.2.1 The Heart-Mind in Mencian Moral Psychology

Having an unmoved heart-mind is important for Mengzi because it manages the will and through it, the qi. But the unmoved heart-mind only nourishes floodlike qi if it itself is nourished with rightness and propriety (yi 義). According to Kwong-loi Shun, the heart-mind can only be unmoved if the will – which governs the qi – accords with rightness and propriety. Cultivating qi is thus necessary to support the will. The unmoved heart-mind is what makes the will conform to rightness and propriety (Shun Reference Shun1997: 75–76, 84). Mengzi’s innovation here is to link qi cultivation to moral excellence. As Alan Chan puts it, for Mengzi, “floodlike qi” is the moral vigor of a sage; qi thus shapes the heart-mind, and this fundamental insight underlies Mengzi’s approach to ethical life. Chan (like Shun) takes the will as the aim or direction of the heart-mind, and necessary to set the heart-mind in a firm direction. However, well-nourished qi is not sufficient to direct the heart-mind, since it can also be set in a wrong direction (A. Chan Reference Chan and Chan2002: 43 and 47).

Mengzi’s claim that qi fills the body was conventional by this time, but his claim that the heart-mind commands it (via the will) is more complex. It is not clear whether Mengzi thinks that qi always follows the dictates of the heart-mind because qi is controlled by the will, rather than the heart-mind. The problem is that everything we do affects our qi. Thus, the heart-mind could only command the qi if it could control its affective and cognitive movements, especially likes and dislikes. The Zuozhuan, Gaozi, and Mengzi (and also the Zhuangzi and the Guodian texts) agree on the importance of regulating the will, so that it does not succumb to the excesses of qi. What distinguishes Mengzi’s approach to self-cultivation is his focus on the importance of the heart-mind’s control of the qi, and how to achieve it.

At issue is how the heart-mind is directed. Chan suggests that Mengzi’s important innovation is the view that we can nourish qi so that the resulting “floodlike qi” becomes one with rightness and propriety. But this can only happen if the qi is consistently nourished by rightness and propriety, since our tastes and preferences affect the qi. Here Mengzi disagrees with Gaozi, who relies on learning from external sources. Mencius takes the source of rightness and propriety to be internal. According to Chan, the heart-mind has an inherent inclination toward rightness and propriety, so that feelings of commiseration and respect arise naturally (A. Chan Reference Chan and Chan2002).

This point is pursued in 2A6, where Mencius famously argues that all persons have a heart-mind that cannot endure the sufferings of others (buren ren zhi xin 不忍人之心). This “mind” is the basis of the four sprouts of virtue (3.6/ 18/ 4). He identifies four innate “heart-minds” that are inherent in human nature:

Anyone without a mind for empathy and compassion is not human; anyone without a mind for shame and repulsion is not human; anyone without a mind for politeness and respect is not human; and anyone without a mind for right and wrong is not human.

無惻隱之心, 非人也; 無羞惡之心, 非人也; 無辭讓之心, 非人也; 無是非之心, 非人也. (Mengzi 3.6/18/7–8)Footnote 11

He considers these four tendencies to be the origin of four major virtues and identifies each tendency as a “mind.” The mind that feels empathy and compassion is the “sprout” (duan 端) of the virtue of humaneness (ren 仁); the mind that feels shame and dislike is the sprout of rightness and propriety (yi). The mind that feels modesty and courtesy is the sprout of ritual propriety (li 禮), and the mind that distinguishes right from wrong is the sprout of wisdom (zhi 智). These four tendencies are as inherent in our nature as having four limbs (Mengzi 3.6/18/8–9). These tendencies resist classification as either purely “affective” or “rational”; the result is a distinctive Mencian conception of practical reason (D. Wong Reference Wong1991, Shun Reference Shun1997). Mengzi thus redefines the mind as a central part of ethical life.

It is in this context that he briefly mentions the heart-mind’s relation to the senses. At 6A15 he argues that individual morality depends on which part of a person guides and controls. That is, whether one follows the greater or more petty part of oneself. Here, the senses play a role. He argues that “the offices of the eyes and ears cannot think, and can be confused by things; it is the office of the heart-mind that can think.Footnote 12 He thus uses the relation of the heart-mind to the senses to account for ethical failure, which occurs when people follow their less important part (the senses) instead of their greater part (the heart-mind). Mengzi thus locates ethical failure in the senses but stops short of claiming the heart-mind’s rule over the senses (Shun Reference Shun1997: 175–77). The full version of that claim is put forward by Xunzi.

2.2.2 Mengzi on Spirit

Mengzi has little to say about spirit; the term shén appears only three times in the Mengzi. One is a clear reference to external spirits, and two passages discuss internal shén. At 7A.13 he remarks that an exemplary person (junzi) manifests spirit. The context is a contrast between the influence of a gentleman, a hegemon (ba 霸), and a true king (wang 王). A hegemon makes the people happy; a true king makes them deeply content, but where a gentlemen passes, transformation occurs and where he resides is spirit-like.Footnote 13 This influence surpasses even that of a true king.

At 7B25, spirit is at the apex of a moral hierarchy:

What is appropriate to desire is called good; but to have it in oneself is called trustworthy. To be filled with it and instantiate it is called beautiful; but to be filled with it, instantiate it, and shine it forth is called great. To be great and thus transform others is called being a sage; but to be a sage whose sagacity is is impossible to understand is called “spirit.”

可欲之謂善, 有諸己之謂信, 充實之謂美, 充實而有光輝之謂大, 大而化之之謂聖, 聖而不可知之之謂神。

In this hierarchy of excellences, when sagacity reaches a level that is impossible to understand, it is called shén. These passages clearly portray spirit as an internal quality, even sagehood. Mengzi suggests the mind’s rule over the senses, but he does not elaborate, nor does he link spirit to claims for the mind’s rulership of the body. These steps are taken by Xunzi.

2.3 Xunzi

Mengzi gave a new importance to the mind by taking its affective and cognitive capacities as the origin of moral development. Xunzi goes several steps farther. First he makes the explicit claim that the mind is the ruler of the body and the senses. Second, he explicitly identifies it as the source of thinking and evaluative judgments, including the assessment of feelings. Third, he explicitly links the activity of the mind to spirit. Xunzi explicitly posits the heart-mind as the ruler of the body and the senses, which function as the heart-mind’s ministers:

When the work of Heaven has been established and the accomplishments of Heaven have been completed, the form is set and spirit arises. Liking, dislikes, happiness, anger, sorrow, and joy are contained therein – these are called one’s Heavenly Dispositions. The eyes, ears, nose, and mouth each has its own form and its respective objects and they cannot assume each others’ abilities – these are called one’s Heavenly Officials. The heart-mind inhabits the central cavity so as to govern the Five Officials; for this reason it is called one’s Heavenly Lord.

天職既立, 天功既成, 形具而神生, 好惡喜怒哀樂臧焉, 夫是之謂天情。耳目鼻口形能各有接而不相能也, 夫是之謂天官。心居中虛, 以治五官, 夫是之謂天君

Here the heart-mind inhabits its central cavity of the body, just as a ruler governs from the center of a state. This container is semi-porous. Information moves from the outside in; orders and instructions issue from the inside out.

2.3.1 Xin And Cognition

Xunzi considers the heart-mind the source of cognition and moral judgments; the heart-mind is the faculty that can understand dao, which allows it to make correct judgments. He attributes this faculty to the qualities of emptiness (xu 虛), unity (yi 壹), and stillness (jing 靜): “How do people know dao? I say: with the heart-mind. How does the heart-mind know? I say: it is through emptiness, unity, and stillness.”Footnote 15 He goes on to explain: “People are born and have awareness; with awareness they have intention.”Footnote 16 People are born with awareness because “The heart-mind is born and has awareness. With understanding comes awareness of differences.”Footnote 17 He explains that the heart-mind has emptiness even though having intentions means that it is always storing something. It has unity even though it is aware of differences. The heart-mind is always in motion, but – if properly cultivated – it maintains stillness by not letting its movements disorder its understanding.

He uses the metaphor of a mirror created by still water to describe this stillness: “Hence, the human heart-mind may be compared to a pan of water.”Footnote 18 If you keep it upright and still, the mud sinks to the bottom, and the water is clear enough to see your face in detail. But even the slightest movement stirs the mud and muddles the water’s clarity. “The heart-mind is just like this” (xin yi ru shi yi 心亦如是矣, Xunzi 21/104/8).

Xunzi describes the heart-mind as making cognitive judgments based on the inputs of the senses and the body: it uses the inputs of the different senses to differentiate different kinds of things. Xunzi emphasizes that these distinctions should be reflected by correct names. The passage begins with the different kinds of information that are differentiated (yi 異) by the individual senses and the body overall:

Form and structure, color, and pattern (xing ti, se li 形體, 色理) are differentiated (yi 異) by means of the eyes. Notes, tones, clear highs, muddy lows, mode, measure and strange sounds are differentiated by means of the ears. Sweet, bitter, salty, bland, piquant, sour, and other strange flavors are differentiated by the mouth. Fragrant, foul, flowery, rotten, putrid, sharp, sour, and other strange smells are differentiated by the nose. Pain, itch, cold, hot, slippery, sharp, light, and heavy are differentiated by the form and frame (xingti 形體). Persuasions, reasons, happiness, anger, sorrow, joy, love, hate, and desire are differentiated by the heart-mind

Each corporeal faculty thus engages in its own proper area of discrimination and differentiates its proper sensory input. At the end of the sequence is the heart-mind, which differentiates emotions, desires, and reason.

In addition, the heart-mind seems to have a unique power to judge its own awareness (though the meaning of this line is unclear, and any reading is necessarily interpretive): “The heart-mind has the power to judge its awareness” (xin you zhi zhi 心有徵知. Xunzi 22/109/1). Once it judges its awareness, it can understand the sounds and forms made available by the ears and eyes. But it can only do so after sensory faculties encounter their objects:

Judging awareness must await the Heaven-given faculties (tian guan 天官) to appropriately encounter their respective kinds and only then can it work. If the five faculties (wu guan 五官) encounter them but have no awareness (zhi 知), or if the heart-mind judges among them but has no persuasive explanations (shuo 說) [for its judgments], then everyone will say that such a person does not know.

Only after this process is complete is it possible to name things (Xunzi 22/109/5). Xunzi’s moral psychology is distinctive for this new emphasis on cognition, understood as the critical and reflective understanding of the heart-mind.

Xunzi also emphasizes that, although the ability to think is a natural human aptitude, this kind of reflective thinking is not natural, and is the product of deliberate effort, which he describes as “deliberate artifice” (wei 偽):

The feelings of liking, disliking, happiness, anger, sadness and joy in one’s nature are called dispositions (qing 情). When there is a certain disposition and the heart-mind makes a choice on its behalf, this is called reflection (lü 慮). When the heart-mind reflects and the abilities act on it, this is called deliberate artifice (wei 偽). That which comes into being through accumulated reflection and training of one’s abilities is also called deliberate artifice.

In summary, Xunzi attributes to the heart-mind a new and unique autonomy to govern, including the ability to accept what it thinks right, choose among emotions, and approve and disapprove of desires.Footnote 21 He thus presents the heart-mind as the faculty that rules the body, engages in cognition and reflection, and apprehends dao: “What the heart-mind deems to be right it accepts; what it deems wrong it rejects.”Footnote 22 In his view, “order and disorder reside in what the heart-mind approves of, they are not present in the desires from one’s dispositions.”Footnote 23

This description goes well beyond the Mengzi. Xunzi defines the heart-mind in a new way by making it the active agent of self-cultivation. It is the site of all psychological phenomena, including sensation, emotion, and desires. But for the heart-mind to engage in critical thinking, it must have a volitional power that allows it to be independent of desires and emotions. The heart-mind’s autonomy is what allows it to supervise the senses, emotions, and desires; its faculty of appropriateness is what allows it to engage in deliberate effort. On this view, human morality has a tenuous connection with Heaven, but a very close connection to the activity of the heart-mind (Lee Reference Lee2005: 37–40).

2.3.2 Xunzi on Mind And Spirit

Xunzi’s third innovation is explicitly linking the heart-mind to internal spirit. Like Mengzi, he takes a pragmatic view of external spirit(s), which he understands as how the cosmos operates as it does: “We cannot see the activity, but we can see the accomplishments. This is what we call spirit.”Footnote 24 But Xunzi is also explicit that humans have internal spirit. For example, he describes what he calls methods to control qi and nourish the heart-mind in order to become “spirit-like”: “In the arts of controlling qi and nourishing the heart-mind, nothing is more direct than following ritual, nothing is more important than getting a good teacher, and nothing is [more] spirit-like than single-minded liking [of these practices].”Footnote 25 Elsewhere, he recommends integrity (cheng 誠) as the way to cultivate the heart-mind (yangxin 養心) and achieve spirit powers: “If, with a heart-mind of integrity, you cling to humaneness (ren) you will embody it [integrity]; if you embody it, you will be a spirit; if you are a spirit, you will be able to transform things.”Footnote 26 Spirit, however, is not inherently moral; some people are “knowing but dangerous, harmful but spirit-like, skilled at deceit but clever.”Footnote 27

Xunzi disagrees with Mengzi’s view of spirit as a capacity that surpasses even sagehood. As Roel Sterckx puts it, Xunzi understands shén as a spirit-like power that can transform and harmonize the world through the activity of a ruler who governs without apparent effort. His understanding of shén is thus grounded in notions of order and hierarchy, both social and cosmic (Sterckx Reference Sterckx2007: 27). The order that results from such a sage-ruler’s activity is shén: “To achieve the utmost goodness and to uphold proper order is called being spirit[- like]. To be so that none of the ten thousand things can overturn you is called being firm. One who is spirit[- like] and firm is called a sage.”Footnote 28 In other words, spirit can be used to transform the people. If an enlightened lord uses power and dao to control the people, their transformation by dao is spirit-like” (ruo shén 如神, 8/31/5).

Xunzi also describes spirit illumination (shénming 神明) as a property of the heart-mind. He considers the heart-mind to be both the ruler of the body and the master of shénming:

The heart-mind is the lord of the form (xing zhi jun 形之君) and the master of shénming (shénming zhi zhu 神明之主). It issues orders, but it takes orders from nothing … thus, the mouth can be compelled either to be silent or to speak, and the body can be compelled, either to contract or to extend itself, but the heart-mind cannot be compelled to change its thoughts. What it considers right, one accepts, what it consider wrong, one rejects.

Xunzi thus links the heart-mind’s control over the body to its mastery of spirit illumination; he thus assimilates spirit-like powers to the normative activity of the heart-mind.

Texts excavated from Guodian present views very similar to those of Xunzi, with several accounts of relations between body and mind.Footnote 29 Two texts argue that the mind rules the body as a ruler rules a state. According to Five Kinds of Action (Wuxing 五行): “The ears, eyes, nose, mouth, hands, and feet – these six are the slaves of the mind.”Footnote 30 Another Guodian text, “Black Robes” (Ziyi), presents a very different metaphor: “The people take the ruler as their mind; the ruler takes the people as his frame. When the mind is fond of something the frame is at peace with it; when the ruler is fond of something the people desire it.”Footnote 31 Here, authority arises from mutual recognition and assent between the ruler and the ruled. These two passages present entirely different metaphors of the mind as ruler. In one, the mind governs the body in agonistic relationship of master to servant; the other presents a harmonious relationship in which a ruler’s authority comes from mutual recognition and consensus.

2.4 Conclusion

This section has surveyed claims for the hegemony of the heart-mind across several Warring States texts. They assert the importance of the heart-mind and attribute to it the capacity to make normative or cognitive distinctions. Such arguments first appear in the Analects and continue to appear in the Mozi, Mengzi, and Xunzi, but these texts make this claim in very different ways. The Analects and Mengzi focus on the “heart” in the heart-mind, its affective capacities, and its ability to guide desires. The Mozi and Xunzi, by contrast, call attention to its more narrowly cognitive capacities. (These capacities are in no way mutually exclusive, but are differences of emphasis.) Xunzi’s views may well be indebted to the Mohists; they also resemble accounts of the centrality of the mind in several texts excavated from Guodian.Footnote 32

A second claim is that the heart-mind is more important than, or has command over, the body or senses. Versions of this view appear in the Mengzi, Xunzi, in texts excavated from Guodian, and in the Tsinghua University bamboo slip texts. Some texts make the specific claim that the heart-mind rules the body or senses. This view appears in analogies between the mind’s hegemony over the body and a ruler’s hegemony over a state.

Finally, arguments about the role of spirit and its relation to the heart-mind appear in claims for correspondence or alliance between heart-mind and spirit. Xunzi in particular identified internal spirit with virtue and with the heart-mind. He thus aligns the heart-mind with spirit in a hierarchically superior relation to the body: the heart-mind and spirit rule the body as a ruler rules a state. The result is a binary view of a person in which the body is opposed to the mind or spirit.

3 Spirit-Centered Perspectives

I now turn to texts that both emphasize the importance of spirit and the body as sites of self-cultivation, and in some cases disparage or marginalize the activity of the mind. These texts all understand spirit (shén) as an internal faculty that is central to self-cultivation, and closely linked with qi and essence (jing 精), a product of refined qi that circulates in the body.Footnote 33 They all describe procedures whereby, if essence is sufficiently still (jing 靜) and unified (yi 一), it transforms into spirit and is stored in the heart-mind, and is the source of sagelike abilities. Spirit thus requires an adequate supply qi and essence. Such accounts occur in the “Inner Workings” (Neiye 內業) chapter of the Guanzi, the Zhuangzi, and several chapters of the Huainanzi. They share important similarities with the “Ten Questions” text from Mawangdui and with medical literature from approximately the first century BCE and later, starting with the Huangdi neijing (discussed in Section 4).

3.1 The Guanzi

Accounts of shén as an intrahuman capacity first appear in the Guanzi, a complex and composite text which presents polyvocal views of body, mind, and spirit. Accounts of persons as composites of body, mind, and spirit appear in two chapters titled “Arts of the Mind,” 1 and 2 (Xinshu shang, xia 心術上, 下, chs. 36 and 37) and “Inner Workings” (Neiye, ch. 49). One difficulty is that text order does not indicate age. “Inner Workings” is considered the oldest of the three, but is numerically the last; and ideas in “Arts of the Mind, 2” seem to derive from it. “Arts of the Mind, 1,” the first of the sequence, is a completely separate work. A fourth chapter, “The Pure Mind” (Baixin 白心, ch. 38), expands on concepts from both “Inner Workings” and “Arts of the Mind, 1.”

3.1.1 Refining Qi and Essence

The “Arts of the Mind” chapters closely link the heart-mind to jing and qi. A passage in “Arts of the Mind, 1” describes a “house” that can become the dwelling of spirit illumination (shénming): “Clean your mansion, open its gates! Once you have eliminated partiality and are without speech, spirit illumination will appear.Footnote 34 An explanation of the passage, states that “mansion” refers to the mind and “gates” to the senses (specifically, the eyes and ears, Guanzi 13.1/96/16, ch. 36). The passage describes a deliberate emptying in order to allow the spontaneous entry of spirit illumination. This replacement is effected by the circulation of jing and leads to the practitioner becoming “enlightened (ming 明) and “spirit-like.” Interestingly, the passage never mentions the mind: the heart-mind is simply a dwelling place that spirit enters and inhabits if the circumstances are correct.

Descriptions of body, mind, and spirit in terms of jing and qi continue in “Arts of the Mind, 2.” It claims that “power” (de 德, a quasi-magical power or virtue, in the sense of “good at”) will only come when the physical form is correctly aligned (zheng 正). But the heart-mind can only govern if body and heart-mind are quiescent (jing 靜). “Align the form and cultivate power; then all things may be fully grasped.”Footnote 35

Here the body and heart-mind work together to acquire powers associated with sages and the legendary rulers of antiquity. However, the passage turns to a potential conflict between a part of the body – the senses – and the heart-mind:

Not to let things disorder the senses (guan 官) and not to let the senses disorder the heart-mind, this is called inner power (nei de 內德). And so, once thought and qi become stable (yi qi ding 意氣定), it [the form] becomes correctly aligned of itself (ranhou you zheng 然後反正). Qi is what fills the embodied person; in conduct, right alignment should be the guiding principle (zheng zhi yi 正之義). If what fills [the person] is not good, the heart-mind will not succeed.

In this passage, the actions of the body (including sense perception) are distinguished from the actions of the mind, but they are not described as ontologically different. Rather they are a composite in which the mind does not rule the senses. The mind has normative functions – and a correctly ordered heart-mind affects the body – but inner power only comes when internal equilibrium prevents the senses disordering the heart-mind.

Because they are a composite, the state of the heart-mind is visible in the body. Correct alignment and quiescence are outwardly visible in firm muscles and sturdy bones. “A complete heart-mind within cannot be concealed. Outwardly it can be seen in the bearing, and it can be observed in the complexion.”Footnote 36 This combination of correct alignment and quiescence strengthens muscle and bone, and also manifests in bearing (xingrong 形容) and coloration (yanse 顏色), emphasizing how pervasively body and mind affect each other. Here, self-cultivation depends not on textual study but on physical and possibly meditative practices.Footnote 37

3.1.2 Spirit in “Inner Workings”

The view that shén is an intrahuman capacity is prominent in the Guanzi chapter “Inner Workings” (Neiye, ch. 49). It makes three claims about the development of spirit. First, essence (jing) is the basis of both physical life and sagacity; it is what constitutes both human internal spirit and external spirits are composed of the same stuff (essence). Second, essence can only lodge in a mind that is stable or settled (dingxin), and that cultivating the heart-mind (xiuxin 脩心) and making one’s thoughts tranquil makes it possible to attain dao. However, third, the senses must be keen and the body must be strong (Guanzi 16.1/116/2–3, ch. 49). In other words, body and mind must cooperate to refine qi into essence.

The discussion of the heart-mind in “Arts of the Mind, 2” (Section 3.1.1, above) addressed the need for a “settled heart-mind” before jing and qi could be circulated and cultivated in the body. As the self-cultivation proceeds, attention shifts to the circulation of jing in the body and the entry of spirit. The Neiye begins by identifying essence (jing) as highly refined qi that is identified with life: “It is always the case that the essence of things is what makes them be alive.”Footnote 38 Jing is also linked to both external spirits and the development of internal spirit and sagacity: “When it flows between Heaven and Earth, we call it ghosts and spirits; when it is stored within a person’s chest, we call that person a sage.Footnote 39

In other words, sages contain the same jing as external spirits (spirits are pure jing; humans are a mixture of jing and form), and jing is clearly identified with both spirit and sageliness. It is stored in the heart-mind, and eventually transformed into spirit. This can only happen if the heart-mind is settled:

Only one who is capable of correct alignment and capable of stillness is, as a result, capable of being settled. When a settled heart-mind is present within, the ears and eyes are keen and bright, and the four limbs are durable and strong, is it possible to create a lodging place for essence. As for essence, it is the essence of qi. When qi is guided, it [essence] is generated.

能正能靜, 然后能定。定心在中, 耳目聰明, 四枝堅固, 可以為精舍。精也者, 氣之精者也。氣, 道乃生.

The text then turns to spirit, understood as an internal faculty that can unify and transform. But the prerequisite for the entry of spirit illumination (shénming 神明) is the correct alignment of the body:

If the form is not aligned, inner power will not come; if the center is not tranquil, the heart-mind will not be well ordered. Align the form, hold fast to inner power, and the extremity of spirit illumination will gradually arrive of itself.

形不正, 德不來; 中不靜, 心不治。正形攝德, 則淫然而自至神明之極

The passage concludes with a warning to not allow things to disorder the senses or to allow the senses to disorder the heart-mind.Footnote 40 The text then turns to spirit, which naturally resides in the body: “There is a spirit that of itself is present in the person, sometimes going, sometimes coming.”Footnote 41 Its loss results in disorder, and its presence ensures good order. If one carefully cleans its lodging place, essence comes of itself. This preparation involves the activity of the heart-mind:

Refine your thoughts and contemplate it; make your thinking tranquil and put it in order. Be reverent, generous, dignified, and respectful, and essence will arrive and settle.

精想思之, 寧念治之, 嚴容畏敬, 精將至定.

These passages offer a picture of complex interactions between body, heart-mind, essence, and spirit. The process begins with aligning the body and settling the heart-mind: correct alignment of the body is a prerequisite for both an ordered heart-mind and spirit illumination. Spirit (shén) is described as naturally present within a person (shēn) and key to internal order. (The Guanzi never warns against “losing” one’s mind, but repeatedly warns against losing spirit.)

The heart-mind is the lodging place of spirit, but also of a “mind within the mind” that seems to be linked with spirit:

The mind thus stores the mind; within the mind there is another mind in it. In that mind within the mind, intention precedes words. Only after there is intention is there form; only after there is form are there words; only after words are there orders; only after orders is there order. If there is no order, disorder is inevitable. If there is disorder, there will be death.

心以藏心, 心之中又有心焉。彼心之心, 意以先言。 意然后形, 形然后言。言然后使, 使然后治。不治必亂, 亂乃死

This “mind within the mind” seems to operate before sensory input; in contemporary terminology, it is precognitive. It is not explicitly identified with spirit.

The end of “Inner Workings” reiterates the importance of correct interactions between the body and heart-mind in order for spirit to arrive. First it is necessary to concentrate one’s qi and align the body correctly: “Concentrate your qi like a spirit and the myriad things will all reside within.”Footnote 42 It also reiterates the importance of the body:

When the four limbs are aligned, and the blood and qi are stilled, unify your awareness, concentrate your heart-mind, and your ears and eyes will never go astray.

四體既正, 血氣既靜, 一意摶心, 耳目不淫.

The procedures described in the chapter start with aligning the body, which in turn aligns the heart-mind. The heart-mind in turn regulates the body and senses. The result is that spirit enters spontaneously, with powers normally ascribed to external spirits. This process clearly requires three elements – body, heart-mind, and spirit – that cannot be reduced to two. As a result, it does not fit dualist descriptions of body and mind (or body and spirit).

A difficulty in this account of spirit is how it arises in a person and why it is so important to retain and not deplete it. It clearly is not part of a person at birth, as it seems to be in the Zhuangzi and clearly is in the Huainanzi (discussed in Sections 3.2 and 3.3), and requires deliberate and sustained effort. Nor is it an “external” spirit or entity that is “invited” or that moves in from outside and can come and go at will. The distinction is that, after the preparations described in “Inner Workings,” spirit arises internally, rather than coming in from the outside. At that point, this internal capacity or power becomes an important part of the person who has cultivated it, and depleting or losing spirit would cause the loss of the powers it entails.Footnote 43

3.2 The Zhuangzi

The Zhuangzi is distinctive both for a negative view of the mind and a positive view of cultivating spirit, but with very different goals than those of the Guanzi.

3.2.1 Zhuangist Critiques of the Heart-Mind

The Zhuangzi’s attitude toward the heart-mind is complex. Several passages appear to belittle its activity, but other accounts of skills and practices clearly rely on it. The Zhuangzi appears to have two objections to the heart-mind. The first is to oppose the – by now – conventional view that it should be the ruler of the body.

A passage in the second chapter of the Zhuangzi seems to ridicule the view that the heart-mind should rule the body: “There seems to be a genuine commander, except we find no sign of it.”Footnote 44 Which, the text asks, of the hundred bones, nine orifices, and six viscera present and complete in the body should we consider as closest to us? Do we have a favorite?

If so, are the others all its servants? Are the servants unable to govern each other? Might they take turns being ruler and servant? Might there be a genuine ruler present among them?

如是皆有為臣妾乎? 其臣妾不足以相治乎? 其遞相為君臣乎? 其有真君存焉?

The text suggests that it is there is no inherent reason for the mind to rule and the rest of the body to be its servants, and asks, perhaps tongue-in-cheek, whether all the parts of the body should rule by turns.

The second objection is that the heart-mind actually obscures our ability to apprehend dao. In Chapter 4, a very Zhuangist Confucius instructs his student Yan Hui on a process of “fasting the heart-mind” (zhai xin 齋心):

Listen not with your ears but with your heart-mind; listen not with your heart-mind but with your qi. Listening stops with the ears, the heart-mind stops with the tallies. The qi emptily waits on things. Only dao gathers emptiness. Emptiness is the fasting of the mind

无聽之以耳而聽之以心, 无聽之以心而聽之以氣! 聽止於耳, 心止於符。氣也者, 虛而待物者也。唯道集虛。虛者, 心齋也

The phrase “the heart-mind stops with the tallies” indicates that what the mind grasps is the signs or symbols – the tallies – that it uses, but these tallies may not correspond well to actual circumstances. So the recommendation is to “listen,” not with the heart-mind but with our actual constituent qi. Unlike the mind, it is “empty,” open, and fluid (Fraser Reference Fraser2024: 255).

David B. Wong usefully explains this difference between attending the mind and attending the qi in terms of the difference between “top-down” and “bottom-up” thinking. The mind works by selecting and by making distinctions, both in empirical judgments that something is “so” or “not-so” (shifei 是非) but also that something is “right” or “wrong” (also shifei). Selection is necessary to get through the day, but it results in a partial and mediated access to the world. Contemporary theories of perception understand the mind to work both top-down and bottom-up. Perception is an interaction of bottom-up processes of receiving sensory input and top-down mental processes of both interpreting it and predicting future sensory inputs based on past assumptions and experience. But this process deprives us of much of our sensory input. The problem is that the perceptions and predictions of a “complete heart-mind” (cheng xin 成心) are insufficient to apprehend the varieties and divigations of dao. The text’s point is that the more we attend – “listen” – to bottom-up sensation from the world, and the less we follow the top-down dictates of the mind, the better we will truly understand things. Seen in this way, “listening with the qi” suggests that it is possible to still the over-eager, top-down heart-mind and enhance the bottom-up processing of sensory information (probably through meditative practices). This approach to “listening with the qi” suggests the importance of the body not only in physical interaction with the world but in “thinking” (Wong Reference Wong2024: 5–6).

Nonetheless, the heart-mind seems to be essential to many attitudes or practices the Zhuangzi praises or recommends. While the Zhuangist authors seem quite critical of the completed heart-mind, other passages refer more positively to a xin that is not fixed, and some of the skill masters (for example, the wheelwright Lun Bian) use their heart-minds in ways the Zhuangist authors endorse. These include the mastery of skill (discussed in Section 3.2.3) and the complex analytic activity that characterizes the arguments of several chapters, Chapter 2 especially.

3.2.2 Concentrating Spirit and the Body

In contrast to its ambivalent or critical view of the heart-mind, the Zhuangzi seems to view spirit in entirely positive terms. (The Zhuangist authors do not share the Xunzi‘s warning that some people are “knowing but dangerous, harmful but spirit-like,” discussed in Section 2.3.2.) The Zhuangist focuses on spirit in two contexts. One is accounts of the importance of “concentrating shén” and of spirit “dwelling within.” The other is the use of spirit in the exercise of certain kinds of skill.

The Zhuangzi repeatedly presents the attitudes and behavior of a “spirit person” (shénren 神人) as different from – and superior to – the judgments and responses of the heart-mind. In Chapter 1 a “spirit person” makes grain ripen and protects animals from plagues by “concentrating shén” (shén ning 神凝, 1/2/16). Chapter 2 praises “realized persons” as “spirit-like”(zhi ren shén yi 至人神矣, Zhuangzi 2/6/17).

Other passages refer to spirit “inhabiting” the body in terms reminiscent of “Inner Workings.” After its description of fasting the heart-mind (discussed in Section 3.2.1), Chapter 4 describes the entry of spirit as a consequence of pushing out the knowledge of the heart-mind:

Let your ears and eyes connect within and push out the knowledge of the heart-mind, then ghosts and spirits will come and lodge [within].

夫徇耳目內通而外於心知, 鬼神將來舍.

Several passages in Chapter 11 describe self-cultivation practices that nourish spirit by a – perhaps counter-intuitive – combination of aligning the body by withdrawing from sensation: “Don’t look, don’t listen; Enfold your spirit in stillness; The body will correct itself.”Footnote 45 It continues:

“Let your eyes see nothing, your ears hear nothing, your heart-mind know nothing; Your spirit will guard your form and your form will live long.

目无所見, 耳无所聞, 心无所知, 女神將守形, 形乃長生.

The passage concludes with the advice to “carefully guard your embodied person” (shen shou nü shēn 慎守女身 11/27/27). Another passage in the same chapter describes similar practices as “nourishing the heart-mind” (xin yang 心養):

Simply abide in wuwei, and things will transform of themselves. Let the form and frame fall away; cast out hearing and vision … release your heart-mind and free your spirit.

汝徒處无為, 而物自化。墮爾形體, 吐爾聰明 … 解心釋神.

These passages privilege spirit over the heart-mind, but also assert a strong relation to the body. On the one hand, they repeatedly urge putting the body or senses at a distance, but they also describe the body aligning itself correctly as a result.

3.2.3 Spirit and Skill

Chapter 3 and several passages in the Outer Chapters links spirit to the exercise of skill in depictions of hyper-aware individuals who excel at the performance of a craft or skill. In Chapter 3 the skilled butcher Pao Ding 庖丁 explains that he relies on spirit, rather than technical expertise in carving oxen:

Now I meet it [the ox] with spirit rather than looking with my eyes. The knowledge of the senses stops, and then spirit urges proceed.

臣以神遇而不以目視, 官知止而神欲行.

Pao Ding emphasizes that what he values is dao, not simple skill. As the scene concludes, the Lord Wenhui (whom he has been instructing) exclaims that Pao Ding’s words have taught him how to nurture life (yang sheng 養生, Zhuangzi 3/8/11).