Introduction

The concept of multimorbidity was first published in 1976 (Brandlmeier, Reference Brandlmeier1976). Multimorbidity has been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as people being affected by two or more chronic health conditions (World Health Organization, 2008). Multimorbidity is a very interesting and challenging concept particularly for family medicine (FM), given the increasing prevalence of chronic illness in an aging population across all developed countries. It is closely related to a global or comprehensive view of the patient, which is a core competency of FM, as defined, for instance, by the World Organization of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians (WONCA) (European Academy of Teachers in General Practice, 2002). It is a global “functional” view (useful for long-term care) versus a “disease” centered point of view (useful for acute care) (Huber et al., Reference Huber, Knottnerus, Green, van der Horst, Jadad and Kromhout2011).

The European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN) has created a research agenda specifically designed for methodological and instrumental research, which includes the development of primary care epidemiology, focusing on patient-centered health (Hummers-Pradier et al., Reference Hummers-Pradier, Beyer, Chevallier, Eilat-Tsanani, Lionis and Peremans2010). A comprehensive definition of the concept of multimorbidity (ie, one which is both understandable and usable for further collaborative research) was an important objective for this research network. The objective was to help researchers in FM to investigate the complexity of patients’ conditions and their overall impact on patients’ health. This concept of multimorbidity could be an additional tool for FPs, enabling them to prevent decompensation (Le Reste et al., Reference Le Reste, Nabbe, Lingner, Kasuba Lazic, Assenova and Munoz2015a).

A research team, including nine national groups, all active within the EGPRN, has created a research community for the purpose of clarifying the concept of multimorbidity for FM throughout Europe (Le Reste et al., Reference Le Reste, Nabbe, Lygidakis, Doerr, Lingner and Czachowski2012). This group produced a comprehensive definition of the concept of multimorbidity through a systematic review of the literature (Le Reste et al., Reference Le Reste, Nabbe, Manceau, Lygidakis, Doerr and Lingner2013). This concept was translated into most European languages for use in further collaborative research (Le Reste et al., Reference Le Reste, Nabbe, Rivet, Lygidakis, Doerr and Czachowski2015b). Finally, it was validated using qualitative research throughout Europe (Le Reste et al., Reference Le Reste, Nabbe, Lazic, Assenova, Lingner and Czachowski2016) and a specific research agenda was issued (Le Reste et al., Reference Le Reste, Nabbe, Rivet, Lygidakis, Doerr and Czachowski2015b). The EGPRN concept of multimorbidity included a set of different variables assessing patients’ multimorbidity, multimorbidity modulating factors, and multimorbidity consequences.

Decompensation (ie, death or hospitalization in acute care) is a challenge for FM as FPs, being familiar with their patient’s health status (Garrido-Elustondo et al., Reference Garrido-Elustondo, Reneses, Navalón, Martín, Ramos and Fuentes2016), could miss tiny factors which, if noticed, could help to prevent decompensation (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Heckman, McKelvie, Jong, D’Elia and Hillier2015). A predictive model that could be integrated into their clinical practice could help them to prevent decompensation and avoid serious health outcomes for their patients (Lussier et al., Reference Lussier, Richard, Glaser and Roberge2016). The EGPRN concept of multimorbidity was considered highly suitable for a purpose such as this. It could lead to a usable model for preventing decompensation.

The French population is aging, with one in three people over 60 years of age in 2050 (Robert-bob, Reference Robert-bob2006). Consequently, the number of dependent patients, some requiring institutionalization in care homes (CHs), is growing. Patients residing in CHs are included in the EGPRN definition of multimorbidity. In France, as in most European countries, patients in residential care are treated by FPs.

The purpose of this research was to assess which criteria in the EGPRN concept of multimorbidity could detect decompensating patients in residential care within a primary care cohort at a six-month follow-up.

Materials and methods

The survey was a prospective cohort study.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University de Bretagne Occidentale. The participants (FPs and patients) provided their written informed consent to participate in the study. The ethics committee approved the consent procedure.

Research team

Two senior FM researchers, one statistician, and two trainees in FM constituted the research group to improve participant selection and to support the FPs in the inclusion and follow-up procedure. A scientific committee composed of eight European senior researchers in primary care supervised the survey.

Participant selection

The study population included all multimorbid patients (according to the EGPRN definition of multimorbidity) who met 12 FPs in the Lanmeur residential care home in the county of Finistere (in north-west France). These FPs were drawn from those physicians associated with the Lanmeur residential care home.

Inclusion criteria were patients meeting the criteria for the definition of multimorbidity according to the EGPRN definition: any combination of chronic disease with at least another disease (acute or chronic) or a bio-psychosocial factor (associated or not) or somatic risk factor.

For the team, bio-psychosocial factors meant all psychosocial risk factors, lifestyle, demographics (age, gender), psychological distress, socio-demographic characteristics, aging, beliefs and expectations of patients, physiology, and pathophysiology.

In all cases, monitoring overtime was required, and the patient had to sign an informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were patients not meeting the criteria of the definition of multimorbidity, the inability to follow the study over time, patients on legal protection, and patients for whom survival was estimated at less than three months.

Data collection

FPs who had agreed to participate worked according to the following plan: first, the multimorbid patient was asked to give his/her consent to participate in the study once the terms had been explained to him/her. After that, FPs completed a questionnaire about their patient.

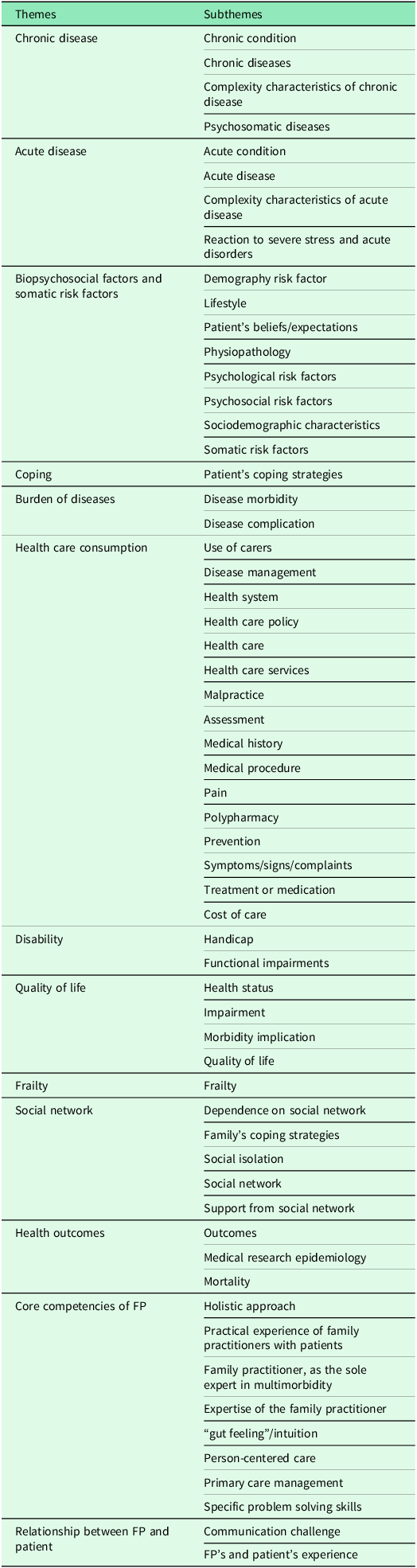

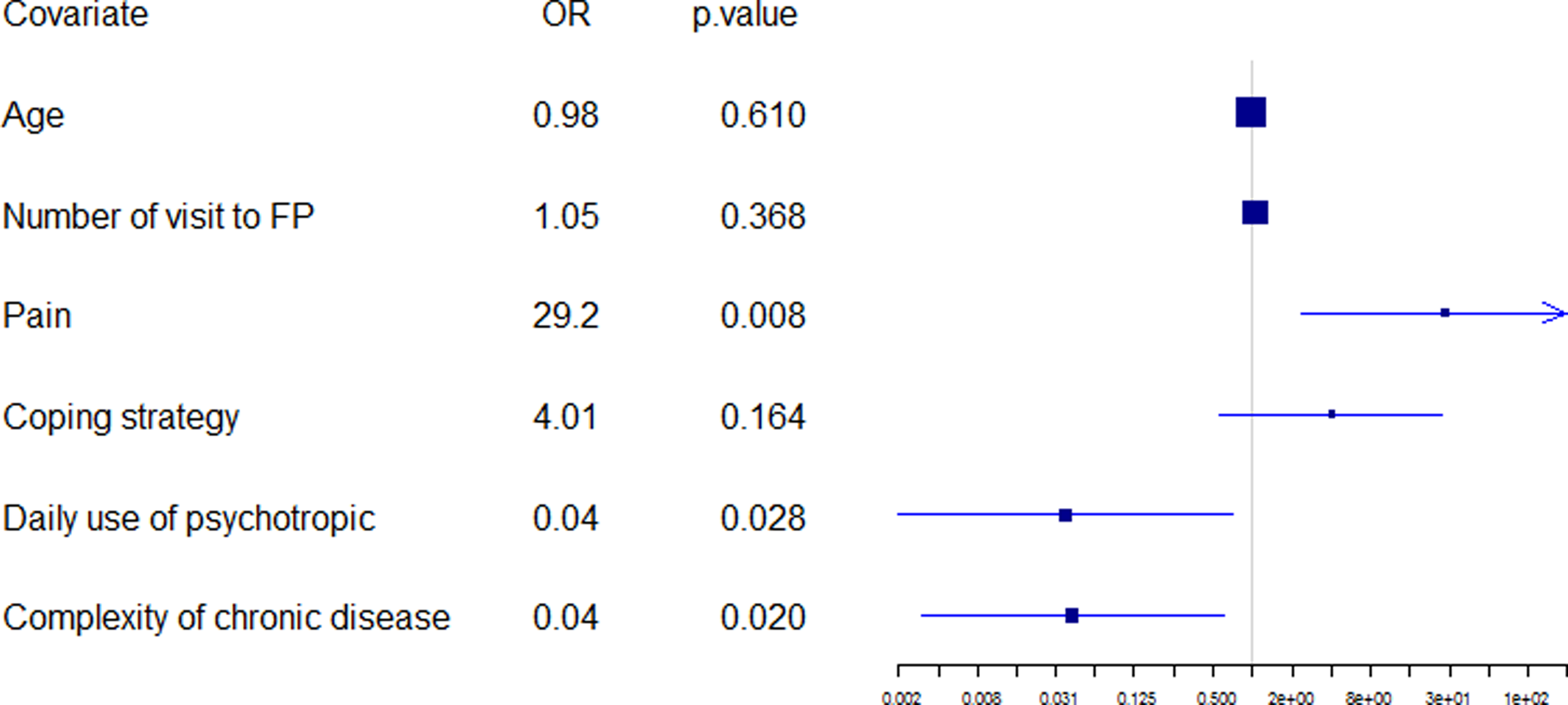

The purpose of this questionnaire was to explore potential decompensation risk factors within the themes and subthemes of multimorbidity (Table 1).

Table 1. Themes and subthemes identified for the multimorbidity concept of EGPRN

The research group developed this questionnaire according to the definition of multimorbidity. To evaluate the concept of somatic risk factors, the team retained variables around a cardiovascular risk factor, a risk of falling factor, and an assessment of hygiene, nutrition, and physical activity. The risk of falling was calculated using the score CETAF. A first pilot study was used to delete some irrelevant variables: chronic condition (which was already described within chronic disease or psychological risk factor), cost of care (impossible to estimate given the time and resources dedicated to the study), disability (disability/impairment), quality of life and health outcome (that is, the consequences rather than the characteristics of the multimorbidity), physiology (the notion is too broad to be evaluated), demography, and aging (already assessed within sociodemographic characteristics). This questionnaire was accepted by the scientific committee of the research team and tested with FPs and medical students. It was formatted to conform to computerized data collection with the help of EVALANDGO software. Data were saved using Microsoft Excel. Six months after inclusion, FPs were contacted by email to check the status of the patient. The collected data were anonymized and a number was assigned to each patient, in order of inclusion. The patient was then classified into either group according to his/her status: decompensation (D) or nothing to report (NTR). The team defined decompensation, in this context, as the occurrence of hospitalization for more than six days or death during the six months of follow-up. Where necessary, the research team called the FPs to collect these data.

Data analysis

In order to harmonize the data before statistical analysis, a data cleaning process was completed. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data and check the data quality. Some missing data were identified. For instance, some questions about the number of specialist consultations per year were unanswered in the case of a few included patients. These missing data had to be detected and to be integrated into the statistical analysis (missing data were replaced by the median value of the group). The biggest recoding work took place during data cleaning: the number of acute and chronic diseases was reconsidered by FP trainees from free text fields completed by FP recruiters. Over one hundred chronic diseases were taken into account. Every change and its rationale was recorded in “a dictionary” which is available on demand from the corresponding author.

Comparisons were made between patients who had decompensated and patients who were in the “nothing to report” group. Continuous variables were compared using the Fisher–Snedecor procedures and the Fisher’s exact test was performed for categorical variables. A multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was used to reduce the dimensions (factorial method). The patients are represented in factorial space where each dimension represents a combination of the initial variables. As this technique is suitable for qualitative variables only, quantitative variables are not used during the procedure but they are then projected, a posteriori, onto the factorial space. Based on the individual coordinates obtained, the technique of hierarchical clustering on principal components (HCPC) was then performed to highlight groups of patients sharing common characteristics. The combination of MCA and HCPC helps in the interpretation of the group results. For the purpose of the evaluation of the optimal number of groups in the dataset and the clustering stability, an alternative procedure was carried out. The same clustering structure was obtained. A clustering quality index (Silhouette) was plotted as suggested by Kaufman (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, Reference Kaufman and Rousseeuw1990). Each cluster was then described and interpreted using a list of qualitative and quantitative variables for which the proportion, or mean of the group, was interpreted in comparison with the global rate or the overall mean.

Finally, a logistic regression was used with the objective of identifying factors associated with the patient’s status at six months. As a particular case of the general linear model, logistic regression is suitable because the dependent variable is binary: D (decompensation) versus (vs) NTR (Nothing to Report). The goal was to find the best subset of variables able to explain the decompensation. In this way, a mixed variable selection procedure, backward–forward, was applied with Akaike information criterion (AIC). The shortcomings of this procedure were minimized by combining the results with expert knowledge. The Wald significance tests were used to strengthen the proposed interpretations and the relevance of the results.

Results

Sample

Participants

About 64 patients were included. The status at six months was collected for all patients. None was lost to follow-up.

Data cleaning and recoding

Several non-discriminating variables were removed from the analysis because the entire population included had the same answer: the presence of pharmacological treatment (answer was always yes), material available to the patient (answer was always yes), human aid available to the patient (answer was always yes), institutional life (answer was always yes), unemployment (answer was always no), suicide risk (answer was always no), stress at work (answer was always no), and family history of cardiovascular diseases (answer was always no).

The number of uses of health professionals per year, answer was always 1092 (which is the average number in this nursing home).

Included patients’ characteristics

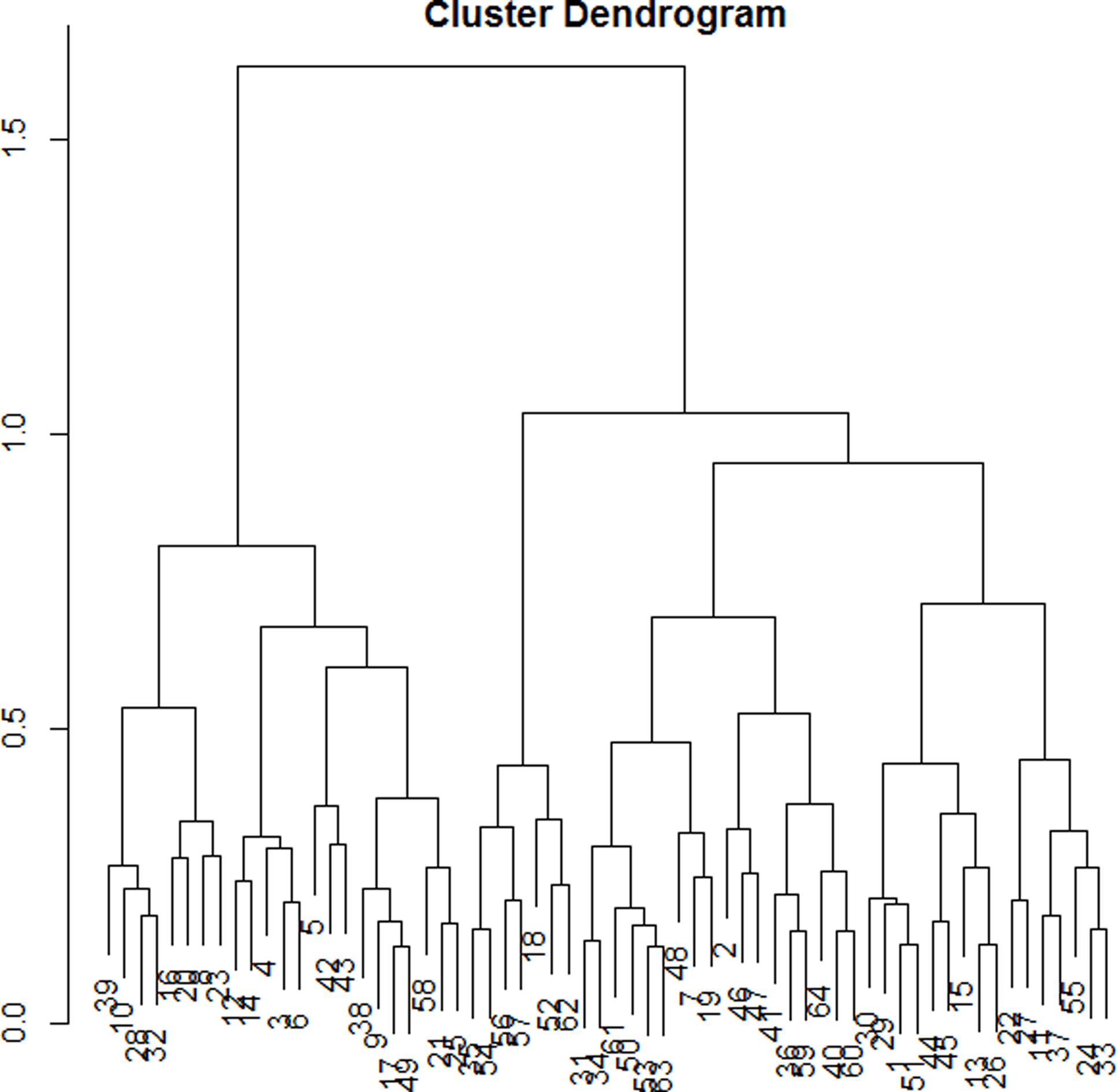

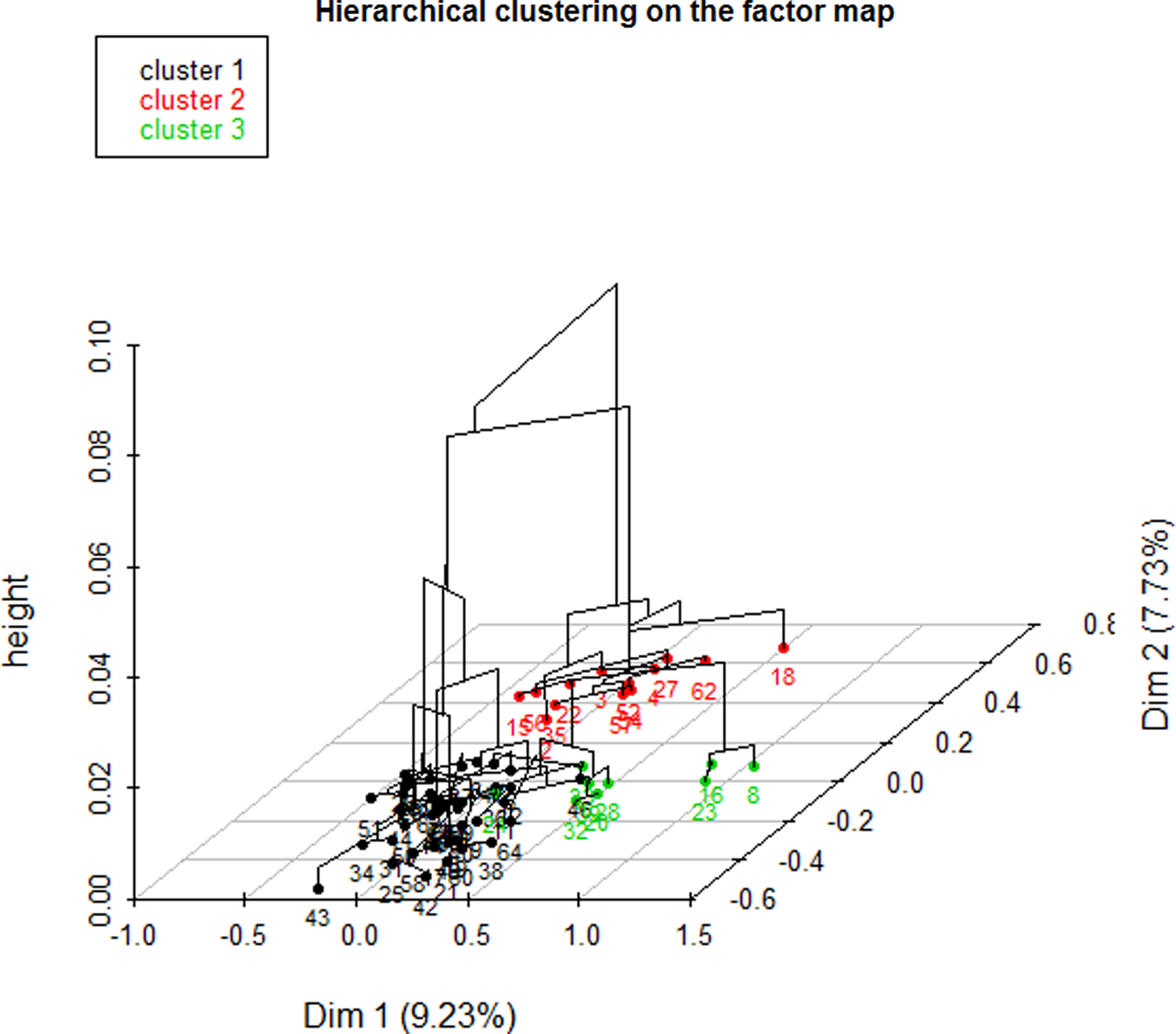

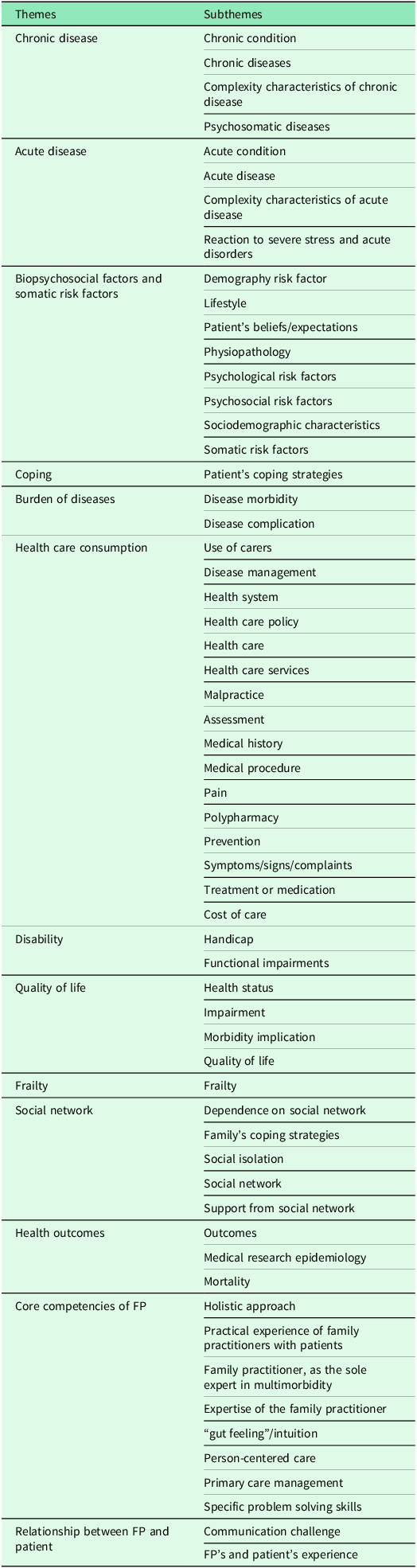

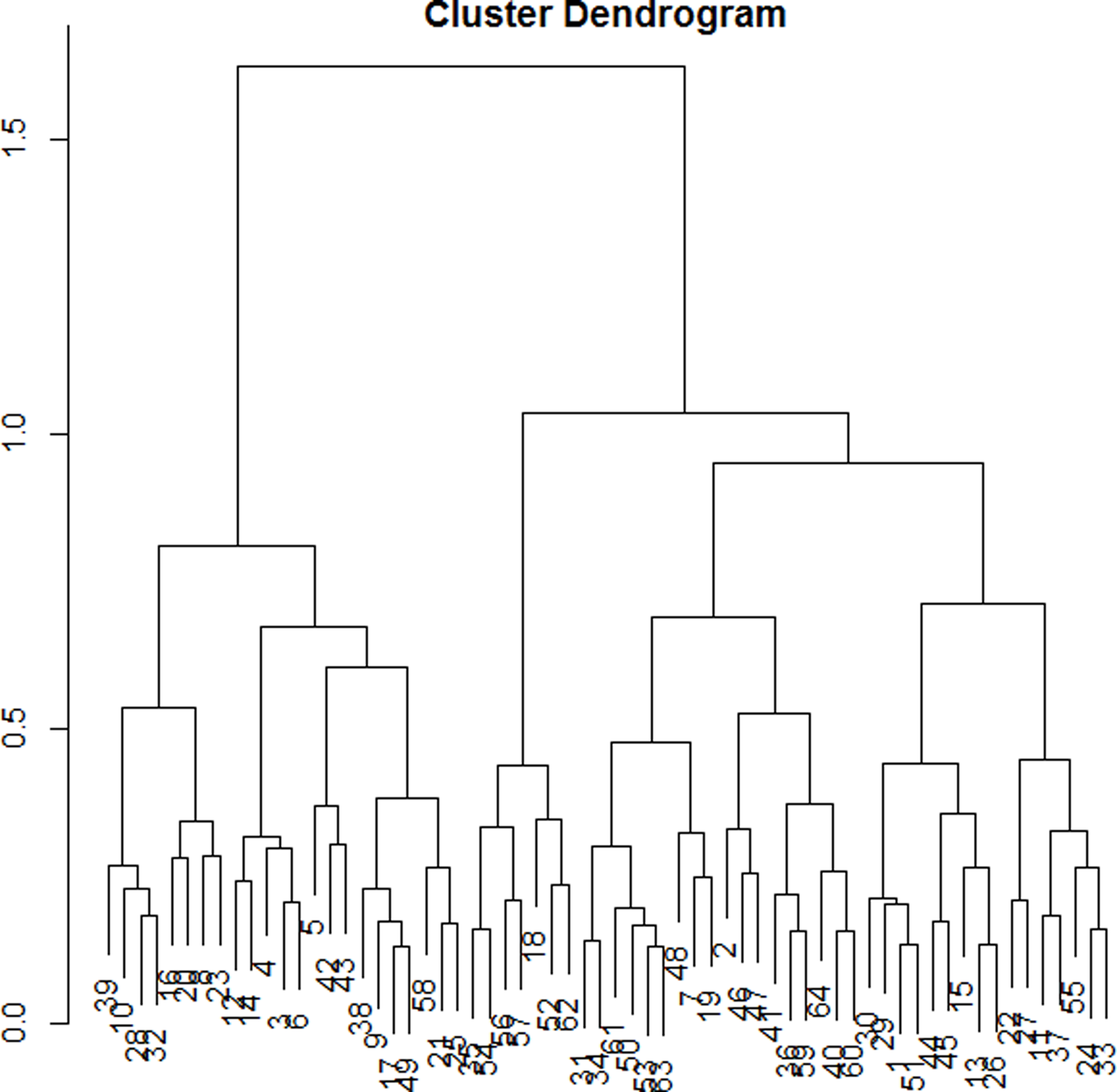

The dendrogram (Figure 1) allowed observation of the hierarchical groups formed from the aggregation of individuals during the hierarchical clustering. The height of a branch is proportionate to the distance between individuals or groups of individuals. Graphically, the dendrogram suggested between 2 and 5 groups, whereas a clustering quality index was maximized for 3 groups of patients. After discussion among the group of experts, the model with 3 clusters was also found to be the most meaningful from a clinical perspective. Figure 2 depicts the 3 groups of individuals projected on the MCA factor map (first two dimensions).

Figure 1. Cluster dendogram.

Figure 2. Factor map.

In order to interpret each patient group, a comparison of the proportion within the group (PwG) and within the study population (PwP), meaning the 64 patients, allowed the team to understand the importance of a variable in measuring specific characteristics.

CLUSTER 1

In this cluster, all patients were single (PwG: 100% vs. PwP: 19%) and without any psychological risk factor (PwG: 100% vs. PwP: 84%), and none showed addictive behavior (PwG: 100% vs. PwP: 87%) or risky lifestyle (PwG: 100% vs. PwP: 95%). Usually, they accepted screening (PwG: 26% vs. PwP: 19%) when suggested. Most of them had experienced the loss of a close relative (PwG: 86% vs. PwP: 69%) or had at least one dependent relative (PwG: 90% vs. PwP: 83%). Often, the patients were female (PwG: 76% vs. PwP: 62%), and a large majority had postural instability (PwG: 86% vs. PwP: 73%). This cluster is characterized by patients without a reaction to severe stress (PwG: 52% vs. PwP: 42%) and without a somatic risk factor (PwG: 90% vs. PwP: 81%).

CLUSTER 2

A large majority of patients in this group had been living as a couple or were widowed (PwG: 92% vs. PwP: 81%). Most of them had not experienced the loss of a close relative (PwG: 77% vs. PwP: 31%). Often, this group was associated with a lower proportion of patients with chronic pathologies (PwG: 61.5% vs. PwP: 34.4%). None of the patients refused screening (PwG: 100% vs. PwP: 81%) when offered.

CLUSTER 3

All patients in this group had at least one psychological risk factor (PwG: 100% vs. PwP: 84%). For example, most of them had an addiction (PwG: 89% vs. PwP: 12.5%) or immunodepression as a somatic risk factor (PwG: 67% vs. PwP: 19%). Relatives did not develop any adaptive strategies to cope with the patient’s situation (PwG: 100% vs. PwP: 64%).

Included patients’ characteristics and status at six months

Six months after inclusion, the population was divided into two groups: 12 “decompensation (D)” and 52 “nothing to report (NTR).”

In the decompensation, group 9 patients were dead and three patients had been hospitalized for more than six days.

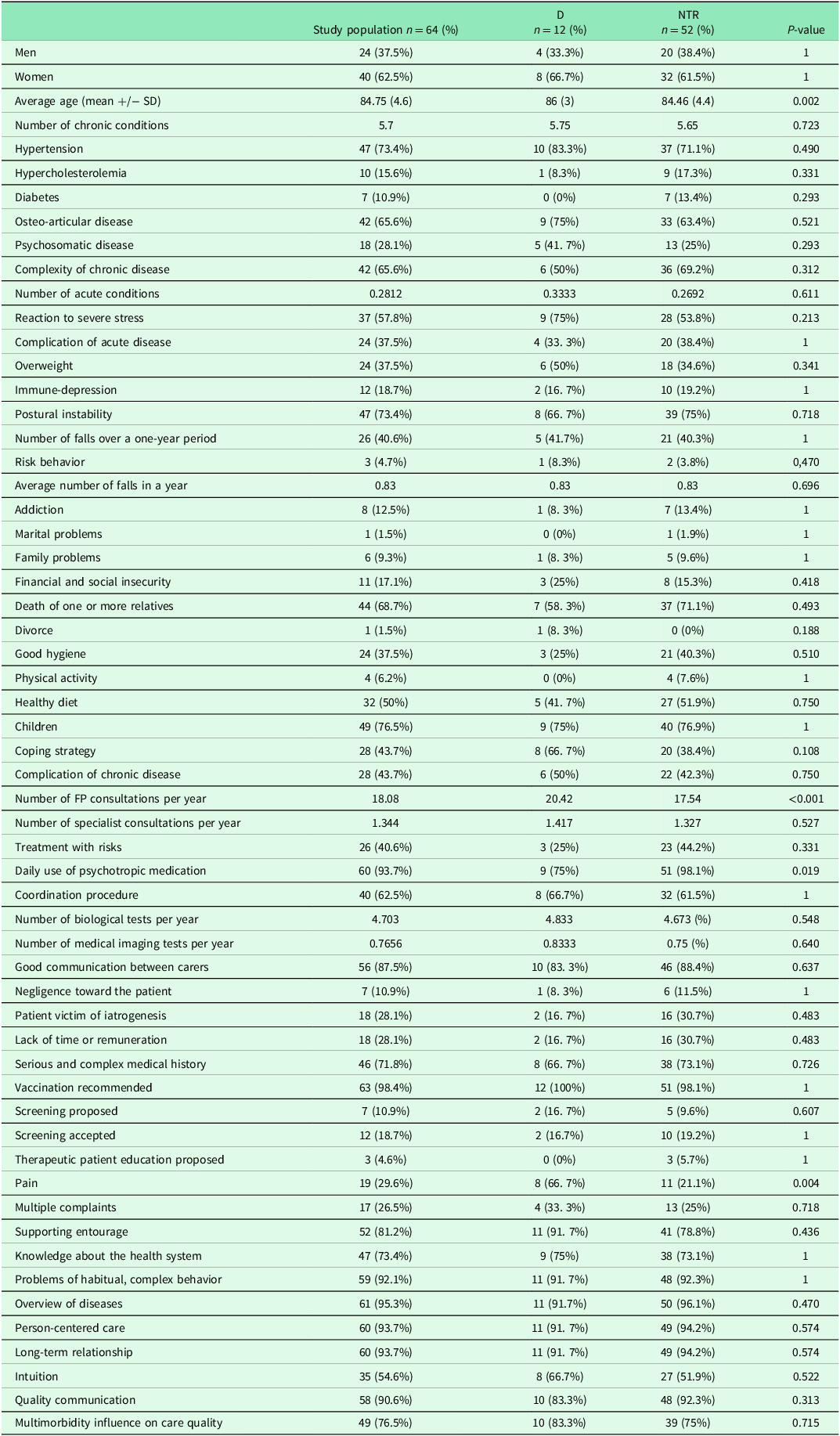

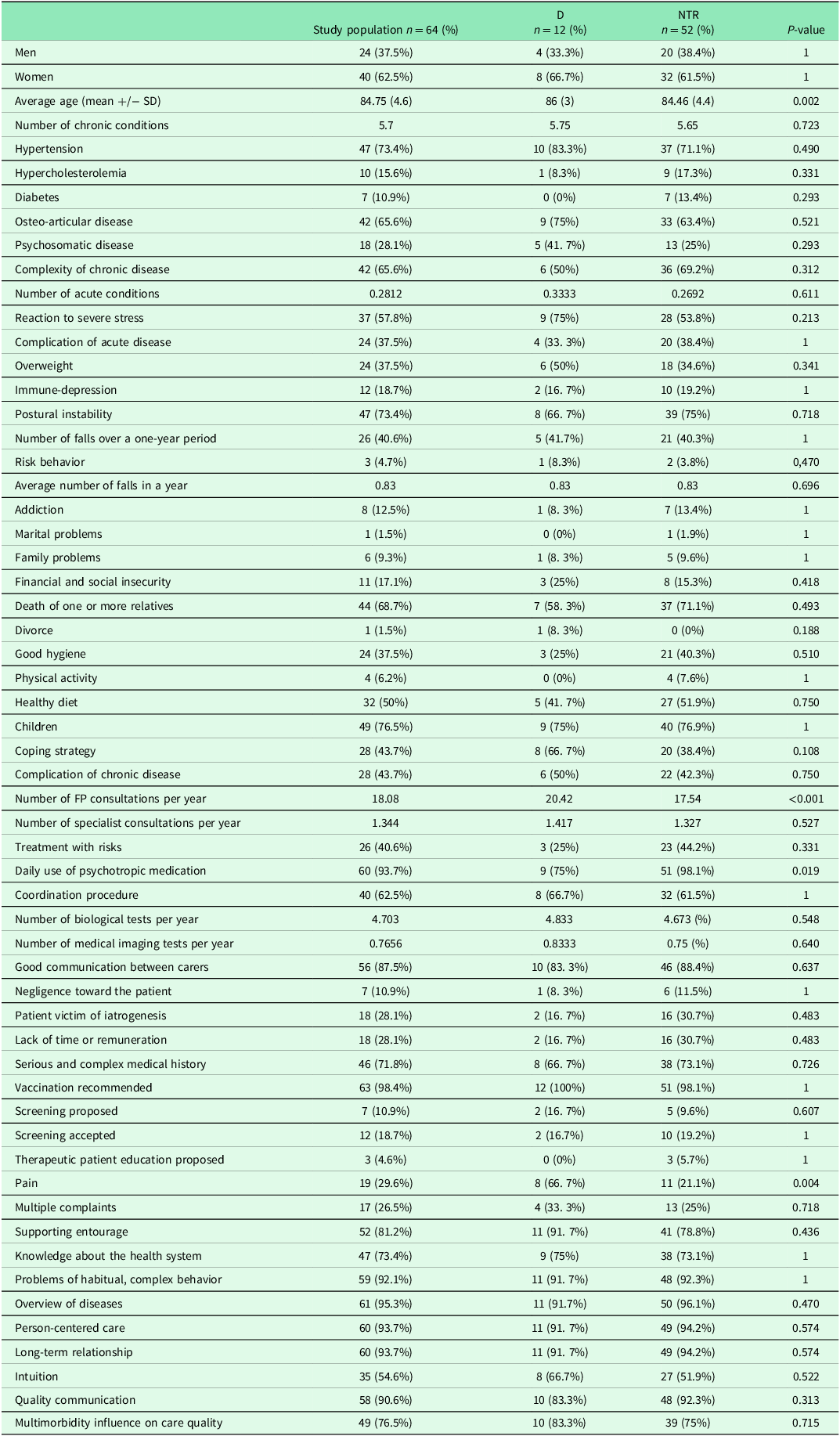

Characteristics of each group are reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Characteristics of the study population

Two qualitative variables compared by the Fisher test were significant (p < 0.05):

-

Patients of “D” group suffered significantly more pain than group “NTR”: 67% in the “decompensation” group compared with 21% in the group “NTR” (p = 0.004).

-

Patients of “D” group used significantly less psychotropic medication (75%) than group “NTR” (98%) (p = 0.019).

A variance test was achieved for quantitative variables. Two means were statistically different between the groups: age (p = 0.002) and the number of FP consultations per year (p < 0.001).

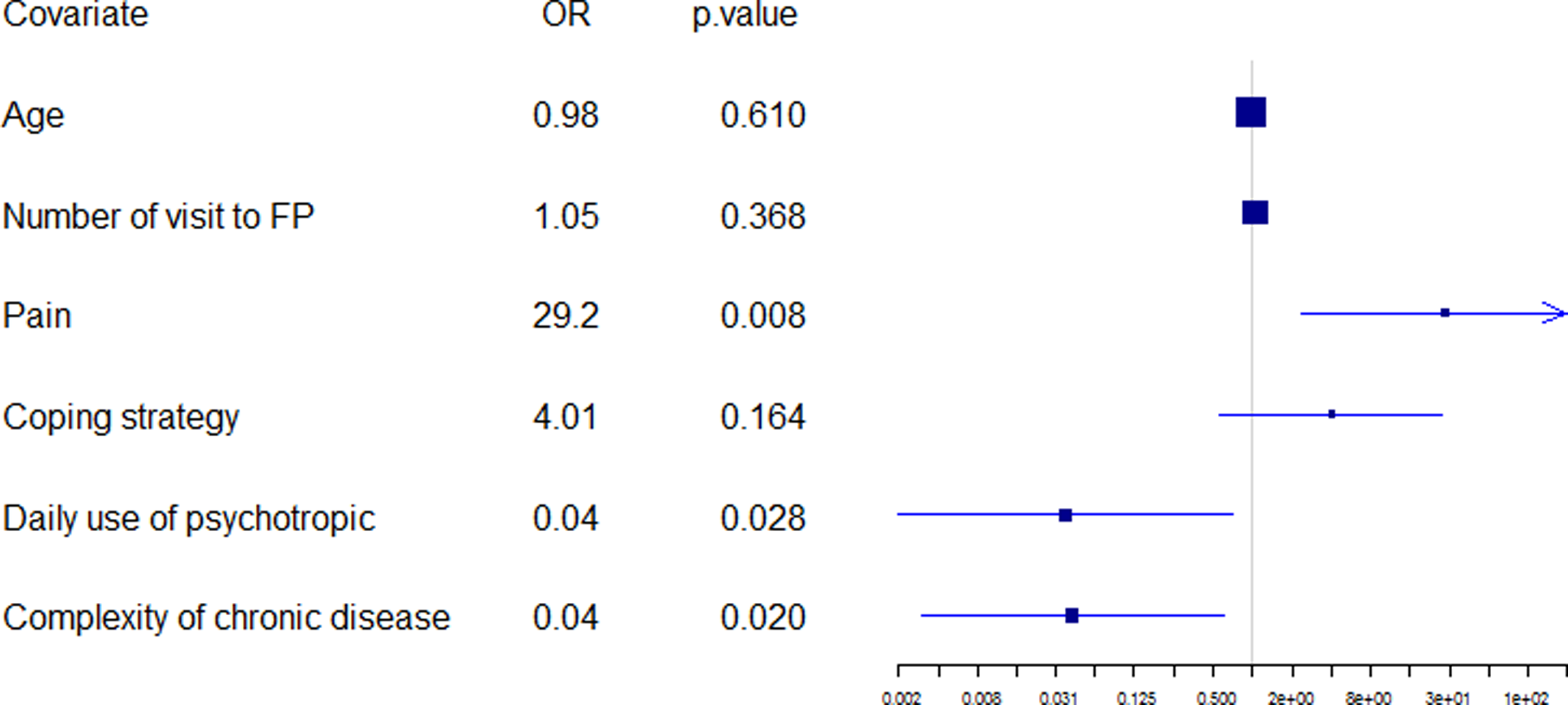

Logistic Regression: Research for decompensation risk factor

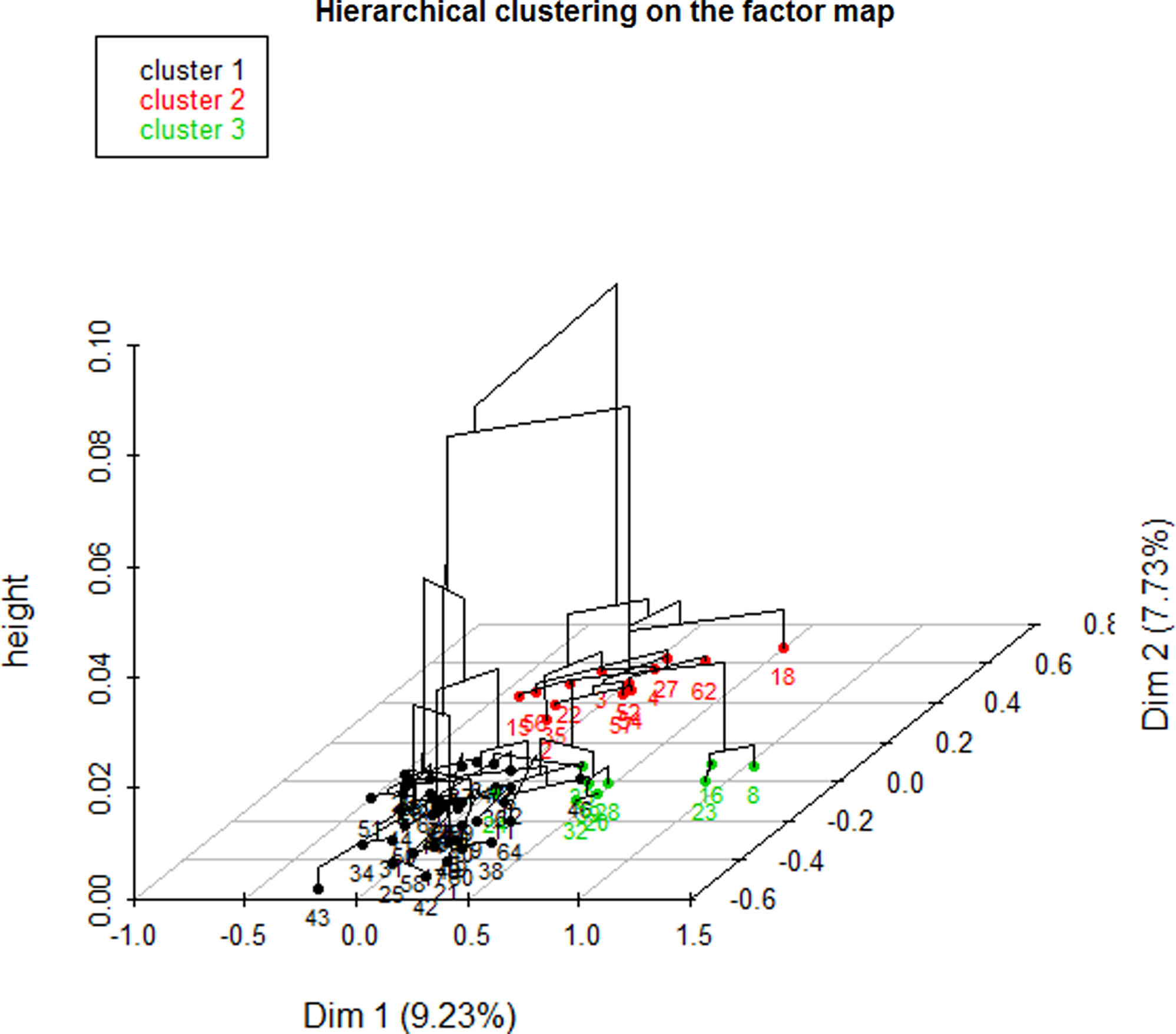

Logistic regression was performed according to the backward–forward procedure used with the AIC to select the most relevant variables. The initial model included all variables with the removal of those which were non-discriminatory. An automatic selection contained 51 variables with substantial “standard error.” It was necessary to bring expert knowledge to bear, at this level in the automatic scanning, in order to reduce the number of variables produced. For example, the names of chronic diseases were removed (bone and joint disease, diabetes, high cholesterol, high blood pressure…), favoring a number of chronic diseases (and not their type as the list was not extensive). Then, the second initial model included 39 variables (available on demand from the corresponding author). An automatic selection contained 12 variables and the final model (figure 3) was obtained using expert knowledge to select the most significant variables and associated confounding factors (which were not necessarily significant, such as age). As the complexity of chronic disease was borderline significant, the research group wished to check up on antecedents and coping strategies. The first was not significant, once adjusted, whereas the second, coping strategy, was close to being significant, at the 90% level.

Figure 3. Final regression model.

Three variables were statistically significant: Patients suffering pain (OR, 29.2; p = 0.008), complex characteristics of chronic disease (OR, 0.04; p = 0.020), and daily use of psychotropic medication (OR, 0.01; p = 0.028).

Key points

The most relevant information from the final regression model was as follows:

-

40% of patients suffering pain had decompensated over the six-month period (p = 0.012);

-

20% of the pain-free patients who presented no complex characteristic of chronic disease had decompensated during the same period;

-

A pain-free patient with a complex characteristic of his chronic disease had no added risk of decompensation; and

-

A pain-free patient with a daily use of psychotropic medication had no added risk of decompensation.

Discussion

Main results

The description of the population showed 3 statistically different features between the “D” group and the “NTR” group: pain (which was higher in the “D” group), daily consumption of psychotropic drugs (which was less in the “D” group), and a complex characteristic of chronic diseases (which was less in the “D” group).

Pain was a factor that appeared in the description of the population but also in the final model. The difference was very statistically significant between the two groups and remained significant after adjustment: patients of the “D” group suffered significantly (p = 0.008) more pain than the “NTR” group: 67% in the “D” group compared with 21% in the “NTR” group. Many studies focused on the prevalence of pain in CHs (Smalbrugge et al., Reference Smalbrugge, Jongenelis, Pot, Beekman and Eefsting2007; Fox et al., Reference Fox, Raina and Jadad1999) and the impact of pain on quality of life (Hopman-Rock et al., Reference Hopman-Rock, Kraaimaat and Bijlsma1997), but the impact of pain on the decompensation of the elderly had not been studied. The studies of analgesia procedures suggested that proper management of pain was a factor that reduced the length of hospital stays (Vaishya et al., Reference Vaishya, Wani and Vijay2015; Essving et al., Reference Essving, Axelsson, Åberg, Spännar, Gupta and Lundin2011). Pain in the elderly was a common and well-known phenomenon with several rating scales: Self-evaluation (digital scale EN or verbal scale EVS) and hetero-evaluation of chronic pain (by DOLOPLUS® or ECPA) or acute pain (by ALGOPLUS). Three significant factors could contribute to this: lack of proper pain assessment, potential risks of pharmacotherapy in the elderly, and misconceptions regarding both the efficacy of non-pharmacological pain management strategies and the attitudes of the elderly toward such treatments (Gagliese & Melzack, Reference Gagliese and Melzack1997).

Daily use of psychotropic drugs was a protective factor. This could seem inconsistent as it was admitted that psychotropic molecules, such as benzodiazepine, increased the risk of side effects in the elderly (including falling and confusion) and therefore, the risk of hospitalization or death. Nevertheless, health teams were aware of the importance of following up their patients on psychotropic drugs, and we could hypothesize that this could lower the follow-up of those without these drugs.

The final model showed a link between decompensation and the absence of any complex characteristic of chronic disease. This variable referred to the burden of disease. The variable « number of diseases » did not emerge from the analysis as opposed to the variable « complex characteristic of chronic disease » while many previous studies on multimorbidity did not highlight the importance of the « burden of disease » and put diseases of very different severity on the same level (Fortin et al., Reference Fortin, Stewart, Poitras, Almirall and Maddocks2012). The result of the final model seemed to go against logic: in fact, patients who did not present any « complex characteristic of chronic disease » were more at risk of decompensation. We could hypothesize that the presence of a « complex characteristic of chronic disease » generated more stringent monitoring by the health team and thus a decreased risk of hospitalization or death.

Strengths and weaknesses

Selection bias

One of the exclusion criteria was an estimated survival expectation of less than three months, this estimate was based solely on the feeling of the team and therefore brought an element of subjectivity to inclusion (Colleter, Reference Colleter2015).

The characteristics of the study population differed from those of the population of French CHs. This was due to recruitment centered solely on the Lanmeur CHs (Colleter, Reference Colleter2015).

Information bias

During the analysis, some results had appeared inconsistent:

-

No patient had a cardiovascular antecedent. This is probably related to the fact that « antecedents » were not well documented in the files.

-

The annual number of demands for paramedic attention was chosen arbitrarily at

three per day because it was too difficult to assess in a CHs.

-

Two patients were noted to have agreed to screening when this had not been prescribed for them. These questions should be changed to “Did the patient receive personal or organized screening?”

-

The patient’s pain was the theme that presented the greatest difference when compared with the French CHs population as a whole (29.69 % in Lanmeur versus 71.50 % in mainland France as a whole) (Colleter, Reference Colleter2015). This was probably due to the information collection method: the question was put to the FP who responded according to his or her own memory of the patients’ conditions (probably remembering the patients with severe pain but not necessarily those with moderate pain). A standardized scale to measure pain was not used. Indeed, many studies on the subject showed a high prevalence of pain in CHs. For example, a Dutch study of 350 CH patients « Pain-prevalence was 68.0% (40.5% with mild pain symptoms, 27.5% with serious pain symptoms) » (Smalbrugge et al., Reference Smalbrugge, Jongenelis, Pot, Beekman and Eefsting2007). In another example, in 1999, a systematic review found that the prevalence of pain ranged from 49% to 83% in CHs (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Raina and Jadad1999). One hypothesis could be that FPs in this study only focused on serious pain as the level of consumption of painkillers in the Lanmeur CH is the same as in other French CHs.

Confounding bias

The themes and sub-themes chosen as references were in English. The questionnaire was conducted by translating from English into French and transforming qualitative into quantitative values. Some translations or transformation values could be inaccurate.

This pilot study was performed using the most appropriate statistical method. However, the small number of patients compared to the large number of variables was the source of many difficulties throughout the analysis.

The choice was made to reduce the number of variables: variables that did not seem relevant statistically, or according to expert knowledge, were removed from the analysis. The results of the final model obtained depended on the choices made previously. These results could have been different if the choices made during the analysis had been different.

What is new with the results

Many studies have been conducted to assess the relationship between multimorbidity and health outcomes but without solving the problem of the meaning or the intensity of that relationship (Winograd, Reference Winograd1991; Speechley & Tinetti, Reference Speechley and Tinetti1991). The most effective variables identified by this study simplify the concept when it targets the specific outcome of decompensation. This is helpful for clinicians in everyday practice. It could resolve the debate around measuring a concept as broad as multimorbidity appears to be.

Focusing on the number and description of all active chronic diseases seemed pointless. Much of the multimorbidity prevalence research used a list of chronic diseases (van den Bussche et al., Reference van den Bussche, Koller, Kolonko, Hansen, Wegscheider and Glaeske2011; Fortin et al., Reference Fortin, Bravo, Hudon, Lapointe, Almirall and Dubois2006; Wicke et al., Reference Wicke, Güthlin, Mergenthal, Gensichen, Löffler and Bickel2014). However, those lists of chronic diseases were very different. In addition, the criteria for the selection of the diseases were often pragmatic (Diederichs et al., Reference Diederichs, Berger and Bartels2011). Based on this observation, the team chose to consider almost all chronic diseases listed by the FPs. However, in the end, this was not important for predicting decompensation. A massive amount of research aimed at clusters of diseases now seems inefficient in predicting decompensation.

Implications for practice, teaching, and future research

In practice, pain should alert FPs and geriatrists to the possibility of decompensation in a multimorbid CHs patient in the subsequent six-month period.

In teaching activities, trainees should be made aware of the importance of this “risk factor.”

In future research, these results should be confirmed by a large-scale study. This study is included in an EGPRN project which aims to define the best possible intervention in order to prevent decompensation in multimorbid patients within 11 European countries.

Conclusion

The pain seemed to be decisive in determining decompensation in multimorbid patients in residential care. The number of chronic diseases and the burden of these diseases do not make any difference. Preventing decompensation, by using the EGPRN concept of multimorbidity, has now become more straightforward in everyday practice within residential CHs.

Data availability statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [JYLR].

Acknowledgements

We thank all FPs who participated in the procedure. This article is supported by the French network of University Hospitals HUGO (Hôpitaux Universitaires du Grand Ouest).

Author contributions

PA analyzed data, drafted, and revised the paper. JYLR designed the study, monitored the data collection for the whole study, collected data, undertook the definition process, and revised the paper. LBC collected the data and revised the paper. MB, PB, MGL, and BC revised the paper. DLG designed the study, collected the data, drafted the paper, followed the study process, and revised the paper.

Funding statement

The department of general practice from the “université De Bretagne occidentale” assumed funding (public funding) for the whole survey.

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflict of interest related to the content of this article.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the “Université de Bretagne Occidentale.” All participants have given their written informed consent.