Plain language summary

Historical documents often contain valuable information, but their unstructured and inconsistent formats make them difficult to use for large-scale analysis. Traditional approaches to information extraction, such as regular expressions and rule-based natural language processing tools, often struggle with these irregularities. This research explores how large language models (LLMs) can help scholars extract and organize data from challenging historical materials. We use the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Plant Inventory books (1898–2008) as a case study. These volumes feature varied layouts, old fonts and inconsistent terminology.

Our approach involved a three-step process that combined the strengths of traditional and newer extraction methods:

-

1. Optical character recognition: We used Azure AI Document Intelligence to convert scanned book images into raw text.

-

2. Custom segmentation: We developed a specialized script to divide this text into logical blocks to handle entries that spanned multiple columns or pages.

-

3. LLM testing: We evaluated commercial and open-source LLMs on their ability to extract specific information (e.g., plant names, type and origins) from the segmented text and structure it into an organized JSON format.

We found that performance varied across models. Open-source models, such as Llama, were constrained by context window limits when processing longer passages. While commercial LLMs showed improved accuracy in identifying and extracting relevant information, the newest models did not necessarily yield the best results. Overall, our findings suggest that LLMs provide a promising starting point for making unstructured historical data more accessible to computational humanities research.

Introduction

Historical sources contain vast amounts of unstructured data with immense potential for scholarly analysis, yet their inherent complexities make it difficult to efficiently capture and process relevant information. Beyond the initial challenge of converting analog materials into machine-readable formats, variability in language, structure and context further complicates efforts to extract insights – even when using state-of-the-art named entity recognition (NER) tools (Ehrmann et al. Reference Ehrmann, Hamdi, Pontes, Romanello and Doucet2023). In the past, building large-scale historical databases has often relied on the labor of countless workers who painstakingly compiled, digitized and standardized heterogeneous records. Because such projects require extensive human intervention for processing and annotation, many promising initiatives never materialize due to the lack of sufficient resources. As a result, significant portions of historical texts remain underutilized and locked behind barriers of unstructured complexity.

Large language models (LLMs) offer promising solutions to these challenges, assisting in tasks ranging from data extraction and annotation to contextual analysis and summarization. A growing number of studies have explored using LLMs for text classification and data mining, with significant implications for fields like healthcare (Fink et al. Reference Fink, Bischoff, Fink, Moll, Kroschke, Dulz, Heußel, Kauczor and Weber2023; Moulaei et al. Reference Moulaei, Yadegari, Baharestani, Farzanbakhsh, Sabet and Afrash2024), the social sciences (Abdurahman et al. Reference Abdurahman, Ziabari, Moore, Bartels and Dehghani2025; Ziems et al. Reference Ziems, Held, Shaikh, Chen, Zhang and Yang2024) and the humanities (Laato et al. Reference Laato, Kanerva, Loehr, Lummaa and Ginter2025; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Santos, Lackey, Viswanathan and O’Malley2024). Targeted approaches for capturing specific entities or classifying texts have proven effective (Bamman et al. Reference Bamman, Chang, Lucy and Zhou2024; Polak and Morgan Reference Polak and Morgan2024; Underwood Reference Underwood2025), and some studies suggest that ChatGPT can even outperform crowd-sourced workers on some annotation tasks (Gilardi, Alizadeh, and Kubli Reference Gilardi, Alizadeh and Kubli2023; Törnberg Reference Törnberg2023). Recently, Stuhler, Ton, and Ollion (Reference Stuhler, Ton and Ollion2025) argued that generative AI tools allow for a more flexible approach to data mining by turning deterministic codebooks into adaptable “promptbooks.”

We build on this body of research to evaluate the potential of LLMs for targeted text mining and information extraction, focusing on the creation of a database from the Plant Inventory booklets published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) between 1898 and 2008. The unstructured and inconsistent formatting of the records poses challenges for traditional information extraction methods, such as regular expressions, rule-based systems and traditional machine learning-based parsers. The variable formatting, however, makes them an ideal test case for assessing the reliability of LLMs for mining unstructured historical texts for humanities research. We find that prompt-based approaches to data mining provide a more accessible and flexible approach to extracting information from unstructured historical texts. However, the “black-boxed” nature of LLMs can lead to errors that are both non-random and ambiguous, especially when working with commercial models and historical texts (Stuhler, Ton, and Ollion Reference Stuhler, Ton and Ollion2025; Underwood, Nelson, and Wilkens Reference Underwood, Nelson and Wilkens2025; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Jin, Zhou, Wang, Idnay, Luo, Park, Nestor, Spotnitz, Soroush, Campion, Lu, Weng and Peng2024). This tradeoff requires a greater degree of care and consideration when validating the reliability of information extraction with generative AI models, especially in fields like digital humanities that are increasingly dedicated to transparency and reproducibility (Ries, van Dalen-Oskam, and Offert Reference Ries, van Dalen-Oskam and Offert2024).

Data

Our primary source of data is the Plant Inventory series, published from 1898 to 2008 by the USDA documenting the introduction of over 650,000 plant materials into the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System. While there was a longer tradition of introducing foreign plants into the United States, the establishment of the USDA’s “Section of Seed and Plant Introduction” in 1898 marked a turning point in centralizing and expanding this process. While the division underwent multiple changes over the years, including its name, it became an important organ of promoting the introduction of foreign germplasm by agricultural explorers, such as David Fairchild and Niels Hansen. The impact of these efforts can be seen throughout the American agricultural landscape, including the countless fields of hard winter wheat, soybeans and lemons. To systematically document newly imported plants and make them available to the growing number of experiment stations scattered throughout the United States, the USDA began publishing this information in booklets that would come to be known as Plant Inventory. Within these booklets, each plant was given a unique number to serve as a means of designation due to the complicated and multilingual context of global agriculture. Each entry also listed detailed information about the plants, including botanical and common names, collection location, collector’s name and descriptive notes about its potential uses or climatic suitability. This systematic documentation reflected the USDA’s effort to centralize agricultural experimentation and maintain a robust archive for plant genetic resources (Fullilove Reference Fullilove2019; Hodge and Erlanson Reference Hodge and Erlanson1956; Hyland Reference Hyland1977; Li Reference Li2022).

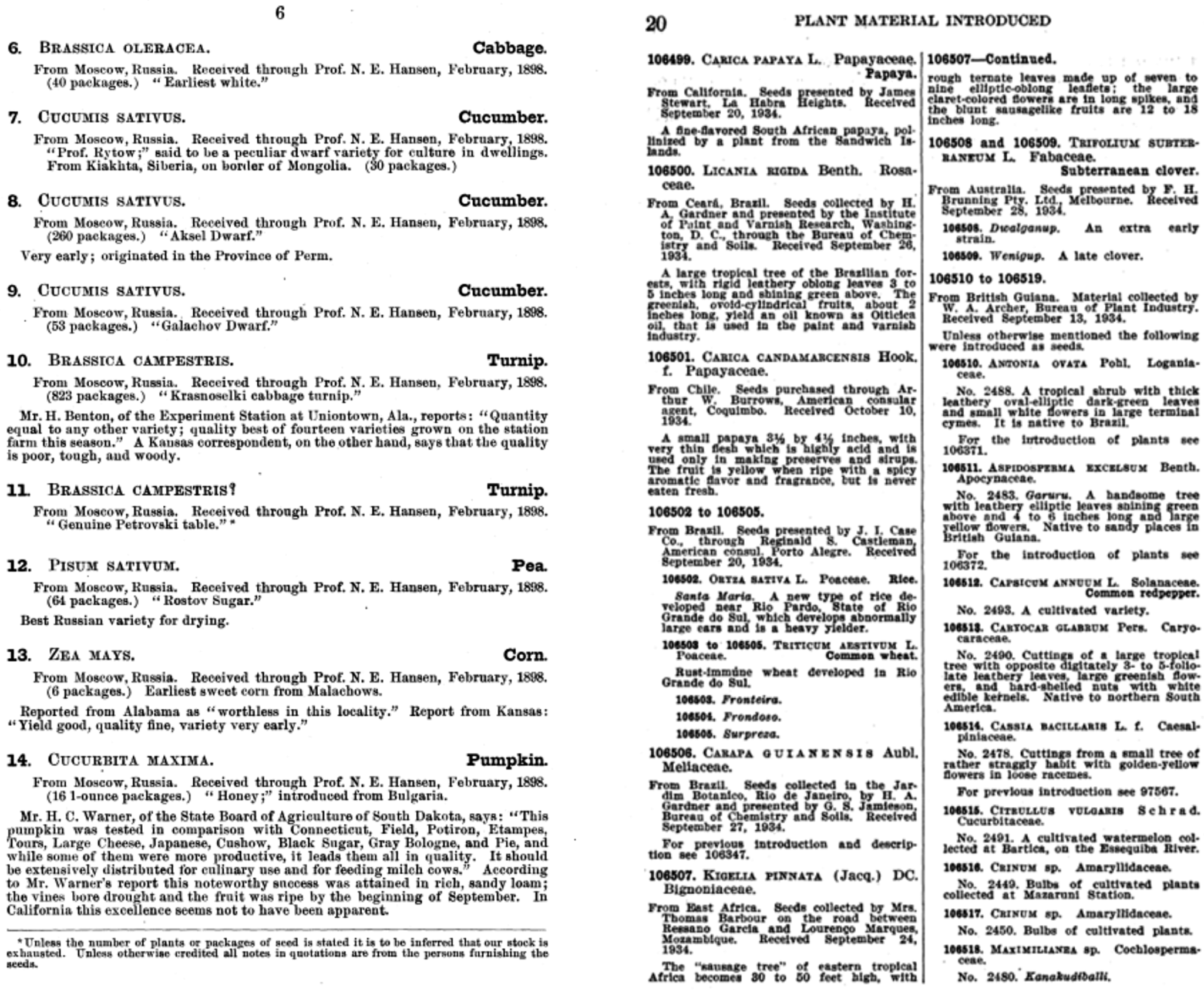

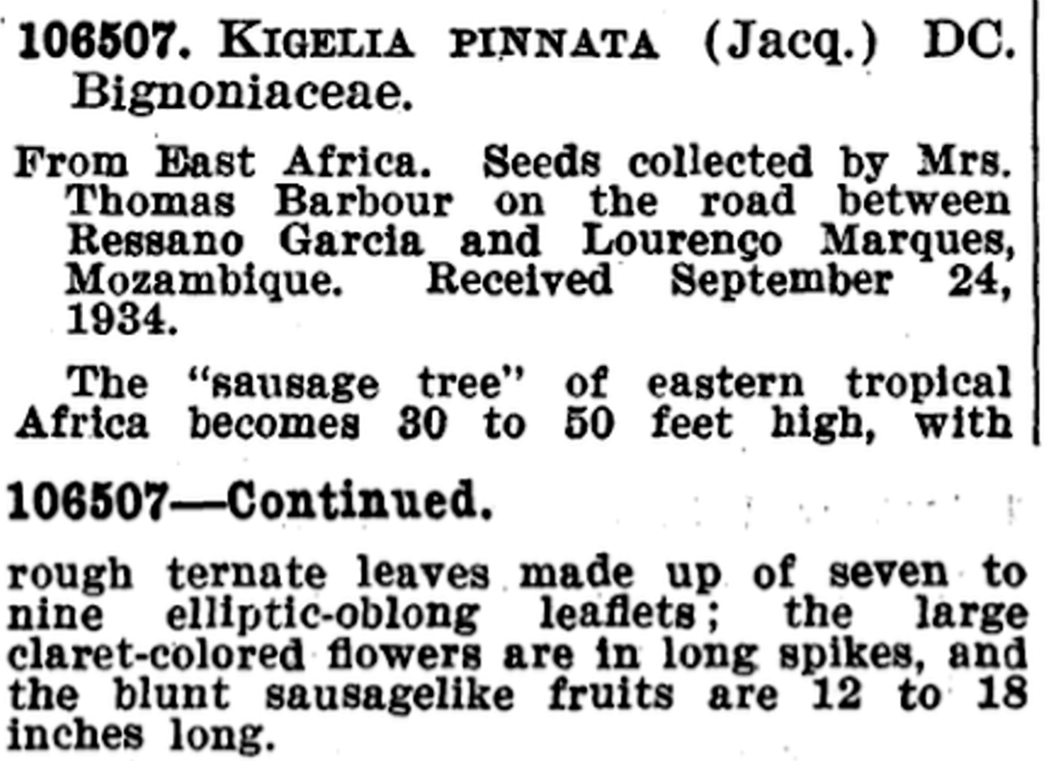

From 1898 to 2008, over 200 booklets were published as bound paper volumes. Initial publications were irregular, but they appeared quarterly from 1903 to 1941, shifting to an annual schedule in 1942. Beginning in 2009, they converted to a digital model. As the regularity of the publications shifted, so too did the format and information included. As seen in Figure 1, the differences could be dramatic, including the introduction of columns on the page or lumping together a range of numbers that might “continue” onto subsequent columns or pages. Such changes introduce additional complexities when trying to digitize the materials. These booklets, then, provide not only a window into the global origins of U.S. agriculture but also a case study for testing the limits of existing optical character recognition (OCR) tools and LLMs in processing complex historical documents.

Figure 1. Page examples from Plant Inventory booklets.

Workflow

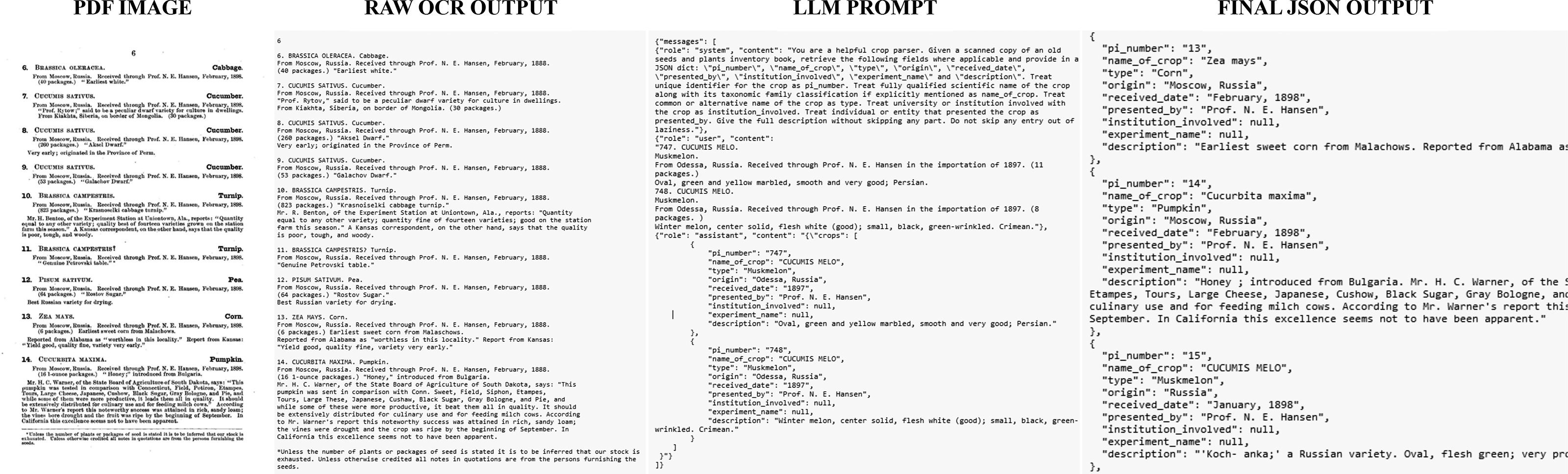

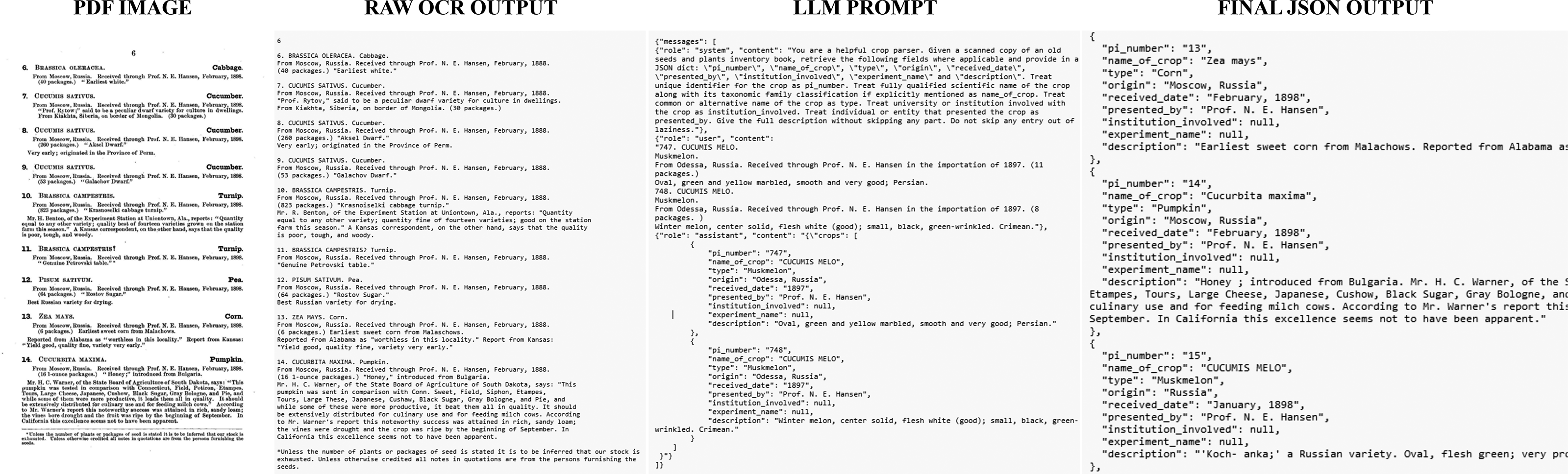

Given the complexity of our documents, which feature multiple formatting styles and irregular text structures, we developed a multi-stage workflow that includes the steps represented in Figure 2. The process begins by converting the PDF image into raw OCR output. This unstructured text is then embedded within a specific LLM prompt, which instructs the model to return the information as a structured final JSON output. A more detailed overview of this process is as follows.

Figure 2. Pipeline for structured data extraction using OCR and LLM prompting.

Optical character recognition

The Plant Inventory books have already been scanned and are available online through multiple venues, including the USDA Agricultural Research Service and the National Agricultural Library. We downloaded a complete run of the 231 publications through the Agricultural Research Service, which totaled 45,051 pages (https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-barc/beltsville-agricultural-research-center/national-germplasm-resources-laboratory/docs/plant-inventory-books/).

We experimented with multiple OCR solutions, each presenting unique strengths and limitations for historical documents. We ultimately settled on using Azure AI Document Intelligence, Microsoft’s OCR engine, after experimenting with both Tesseract and Google Vision OCR. We found that while Tesseract performed adequately on clean images, its handling of complex layouts, such as multi-column pages, resulted in omissions or fragmented text. Google Vision OCR demonstrated robust capabilities that were comparable to Azure, but its ecosystem was less conducive to rapid, iterative prototyping. In our side-by-side comparison during initial testing, Azure consistently provided coherent and complete text extractions with minimal errors, including when dealing with irregularities, such as inconsistent spacing and partial-page text alignments. Its multi-column detection capabilities significantly minimized the need for extensive manual intervention in preparing the raw OCR output for subsequent processing.

LLM prompting

preparing the text for prompting first required us to segment the text into manageable blocks. Simple regular expressions proved insufficient for this task due to the complexity and inconsistency of the entries, which often lacked clear delimiters and sometimes spanned multiple PI numbers; a new regular expression configuration would have been required for nearly every printed volume. Additionally, while sending one OCR-processed page at a time avoided overloading the LLM and minimized hallucination, it introduced a new challenge: many entries extended across multiple pages, making single-page segmentation inadequate (for some examples of these complexities, see Appendix A).

To address this, we developed a Python script to identify and reconstruct multi-page entries by analyzing textual and formatting patterns across all 231 booklets. The script began by detecting anchor elements, such as bold PI numbers or numeric ranges (e.g., “300968–300972”) that typically marked the start of a new entry. It then scanned for continuation cues, such as the keywords “continued,” “to,” or conjunctions like “and,” all of which often signaled entries that spanned multiple PI numbers or pages.

This process distinguished between true continuations (e.g., “300968–300972 – Continued”) and independent entries with similar structures. It also handled complex edge cases, including nested continuations and synonyms used inconsistently to indicate entry extension. To merge these segments, the script maintained a dynamic buffer: one set of functions scanned each line for trigger terms, while another group handled the logic of whether to append content to an ongoing record or start a new one based on contextual cues. After iterative testing and refinement, we established a set of heuristics capable of reliably merging fragmented entries.

Once the text was segmented into coherent multi-page blocks, we used OpenAI’s API playground to craft a prompt that would process the text in accordance with our criteria. The main data points that we extracted included:

-

• PI – The unique plant identifier number assigned to the crop.

-

• Name – The scientific name of the crop species.

-

• Type – The botanical family or classification of the crop.

-

• Origin – The geographic location where the crop specimen was collected or reported.

-

• Date – The date the specimen was received or entered into the record.

-

• Presented – The individual or institution who submitted or presented the crop.

Evaluation

To evaluate the prompt’s extraction performance, we created a ground-truth dataset by manually labeling 525 crop entries from 27 sample text chunks. Our evaluation criteria were designed to provide a granular analysis of performance, moving beyond a single similarity score that might obscure important distinctions between minor transcription errors and complete extraction failures. We therefore employed the following metrics:

-

1. Output reliability: We measured the percentage of model outputs that could be successfully parsed as valid JSON. This metric assessed a model’s ability to consistently adhere to the required output format.

-

2. Field-level accuracy: We calculated accuracy for each metadata field (e.g., name and type) by comparing the extracted value against the ground truth. For this, we first normalized both sets of text to account for minor differences. This normalization included converting text to lowercase, removing punctuation (e.g., “CUCUMIS MELO” vs. “Cucumis melo.”), and reconciling over- or under-extraction of entities (e.g., “Col. Robert H. Montgomery

$\ldots $

” vs. “Robert H. Montgomery”).

$\ldots $

” vs. “Robert H. Montgomery”). -

3. Computational efficiency: We measured the average tokens consumed and the runtime per file for each model. These metrics provide insight into the computational cost and practicality of each approach alongside its extraction accuracy.

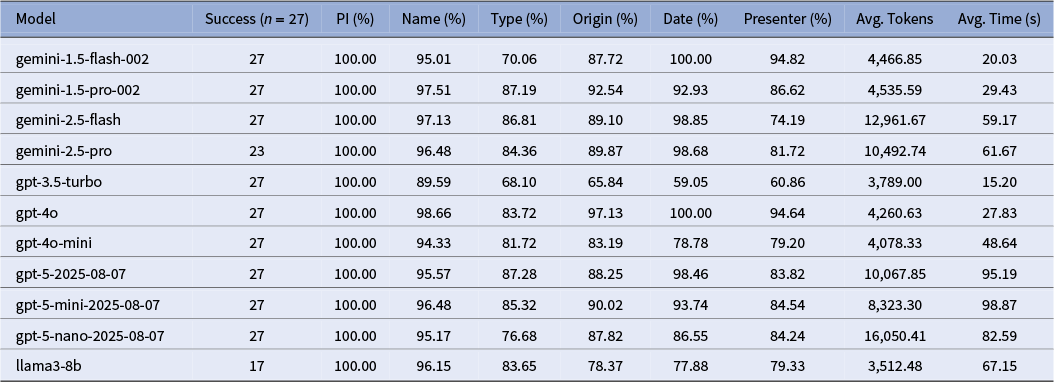

We evaluated a suite of state-of-the-art language models available in late 2024 on their ability to extract structured crop metadata from OCR-transcribed documents. Following an initial round of peer review, we updated our analysis to include several more recent models available by mid-2025. Our comparison included models from OpenAI (GPT-5, GPT-4o, GPT-4o-mini and GPT-3.5), Google (Gemini 2.5 Flash and Pro, and Gemini 1.5 Flash and Pro) and Meta (Llama3-8B), with the temperature set to 0 (when available) to ensure more deterministic outputs. While most models were accessed via commercial APIs, the Llama3-8B model was run locally on a Google Colab A100 High-RAM GPU instance. This local setup introduced additional overhead in managing dependencies and runtime stability, and both this and the Gemini 2.5 Pro failed to successfully process the full set of 27 test files.

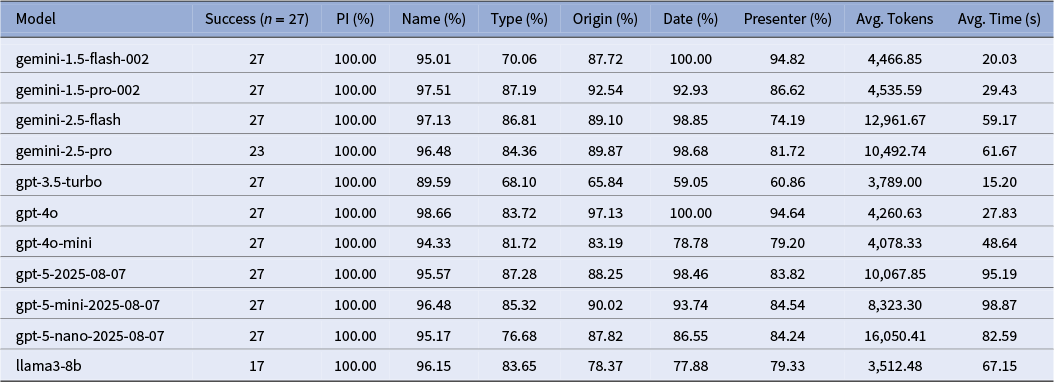

An overview of the results, as shown in Table 1, reveals a clear tradeoff between model accuracy, speed and token efficiency. GPT-4o emerged as the top-performing model, achieving the highest accuracy in the fields of Name (98.66%) and Origin (97.13%). The Gemini 1.5 and 2.5 series models were highly competitive, though they showed variability in certain fields; for instance, Gemini 2.5 Flash scored lower on Presenter accuracy (74.19%). In terms of processing speed, GPT-3.5 Turbo was the most efficient model at 15.20 seconds per file, with Gemini 1.5 Flash following at 20.03 seconds.

Table 1. Comparison of large language models on extraction accuracy, speed and cost

Note: “Success” refers to the number of files that the model was able to successfully process and return in the required JSON format. Subsequent results are based solely on the successfully-returned files. Overall accuracy is calculated by comparing the output from each model to a “gold standard” sample after standardizing for casing, punctuation and over-extraction of metadata.

A qualitative review of the discrepancies reveals several recurring error patterns that highlight the specific challenges of this extraction task. For instance, in the type field, models frequently struggled with semantic ambiguity; for a single entry, one model might extract a generic common name like “tree,” while another would extract the scientific family name, both of which could be technically correct but would fail a direct comparison against a gold standard expecting “acacia.” A second common issue was the over-extraction of structured metadata, particularly in the presenter field, where models would correctly identify a name but also include their title and affiliation (e.g., “Col. Robert H. Montgomery, Director, Coconut Grove arboretum”). Finally, we observed frequent cases of embedded descriptive phrases, especially in the origin field, where text like “at 12,000 feet altitude” was inserted into the middle of a place name. These examples demonstrate that failures were often not simple factual mistakes but rather issues of formatting, specificity and interpretation. While our post-processing framework was ultimately able to manage a majority of these errors, further prompt refinement and model fine-tuning would likely improve the consistency of the initial extraction (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Mann, Ryder, Subbiah, Kaplan, Dhariwal, Neelakantan, Shyam, Sastry, Askell, Agarwal, Herbert-Voss, Krueger, Henighan, Child, Ramesh, Ziegler, Wu, Winter, Hesse, Chen, Sigler, Litwin, Gray, Chess, Clark, Berner, McCandlish, Radford, Sutskever and Amodei2020).

Discussion

One key consideration in our process was the tradeoff between commercial and open-source language models. Commercial APIs (e.g., OpenAI and Gemini) typically offer ease of use, powerful performance, larger context windows and scalable infrastructure. However, they introduce concerns around consistency and reproducibility. Calling the same prompt twice may return different outputs, and proprietary models provide limited visibility into versioning, training data or system behavior. These challenges make it difficult to ensure transparency and replicability.

For this reason, many researchers in the humanities and social sciences have turned to open-source alternatives, such as Meta’s LLaMA models (Alizadeh et al. Reference Alizadeh, Kubli, Samei, Dehghani, Zahedivafa, Bermeo, Korobeynikova and Gilardi2025; Ziems et al. Reference Ziems, Held, Shaikh, Chen, Zhang and Yang2024). These models offer greater transparency and control, but they also demand significantly more computational power. As early-career researchers in Digital Humanities, our access to such resources was limited. We were able to run the LLaMA 3 8B model with a monthly subscription to Google Colab Pro, which was sufficient for small-scale evaluations. However, attempts to scale up to larger models like LLaMA 70B quickly ran into memory limitations, constraints that commercial API-based models typically circumvent. For researchers without access to institutional computing clusters, Colab Pro remains a practical option for working with smaller open models. Still, as of the writing of this paper, these models have their own drawbacks, including inconsistent performance on complex tasks and smaller context windows compared to commercial alternatives.

Moreover, our study provides a limited but productive glimpse into the trajectory of model change over time, along with how prompts can be model sensitive. When holding our prompt constant, the generational leap from older models like GPT-3.5 Turbo to the more recent GPT-4o is unambiguous as seen in Table 1, with accuracy scores jumping more than 30 percentage points in fields like origin. However, the progression among newer models is less linear. The performance of the “GPT-5” series, for instance, did not uniformly surpass that of GPT-4o on this task and came with a substantial increase in processing time. Factors, such as model size (mini vs. standard), intended function (flash vs. pro) and the incomplete runs of Llama3-8B and Gemini 2.5 Pro, are all important to consider when identifying models for information extraction. While this might point to a general yet uneven increase in capacity over time, it also underscores the challenge of prompt portability: a prompt optimized for GPT-4o will not necessarily yield promising results with Gemini 2.5 Pro.

Ultimately, LLMs are not a magic bullet for data extraction. They work best when paired with traditional methods, such as manual annotation, human-in-the-loop verification and domain-specific heuristics (Khraisha et al. Reference Khraisha, Put, Kappenberg, Warraitch and Hadfield2024; Schilling-Wilhelmi et al. Reference Schilling-Wilhelmi, Rıos-Garcıa, Shabih, Gil, Miret, Koch, Márquez and Jablonka2025; Schroeder, Jaldi, and Zhang Reference Schroeder, Jaldi and Zhang2025). By designing thoughtful validation strategies (e.g., checking field alignment, comparing PI numbers across pages and calculating similarity scores), we can build confidence in the outputs, even when working with the black-box nature of generative AI. Used strategically, LLMs can accelerate labor-intensive processes like historical metadata extraction while still preserving data integrity.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the promise and limitations of using LLMs to extract structured metadata from unstructured historical documents. By combining OCR, custom segmentation heuristics and LLM prompting, we developed a pipeline capable of transforming over 45,000 pages of USDA Plant Inventory records into a structured and analyzable dataset. Our multi-model evaluation showed that commercial models like OpenAI and Gemini offer high accuracy and ease of deployment, while open-source models like LLaMA provide transparency and control, though at greater computational cost.

Our results also highlight the indispensable role of validation and post-processing in any LLM-based workflow. Even the most powerful and costly models produced formatting glitches, hallucinated entries and occasional edge-case failures. LLMs, therefore, are complements – not replacements – for human expertise: domain specialists will continue to be essential for designing prompts, interpreting ambiguous outputs and enforcing quality standards. When generative AI is paired with systematic checks and subject knowledge, it has the potential to deliver more reliable and scalable results.

Data availability statement

All code, data and examples can be found on our GitHub repository here: https://github.com/sdstewart/Plant-Inventory-LLMs/.

Ethical standards

The research meets all ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements of the United States.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: S.S., S.D.S.; Data curation: S.S.; Methodology: S.S., S.D.S.; Writing – original draft: S.S., S.D.S.; Writing – review and editing: S.S., S.D.S. Both authors approved the final submitted draft.

Funding statement

This research was supported by the Libraries and School of Information Studies at Purdue University.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Disclosure of use of AI tools

Generative AI was used for assistance in prompt refinement, generating and debugging code, and in basic formatting. Otherwise, no AI tools were used outside of the experimental methodology outlined in the paper.

Appendix A. Sample input and output from fine-tuned LLM

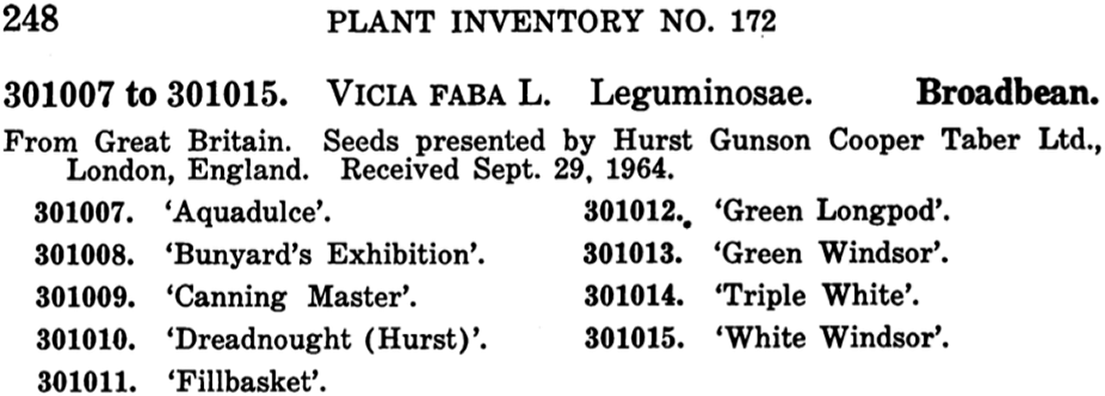

Example A.1. Example of how the model was able to account for irregular formatting, most notably applying information to a subset of plants.

INPUT:

OUTPUT:

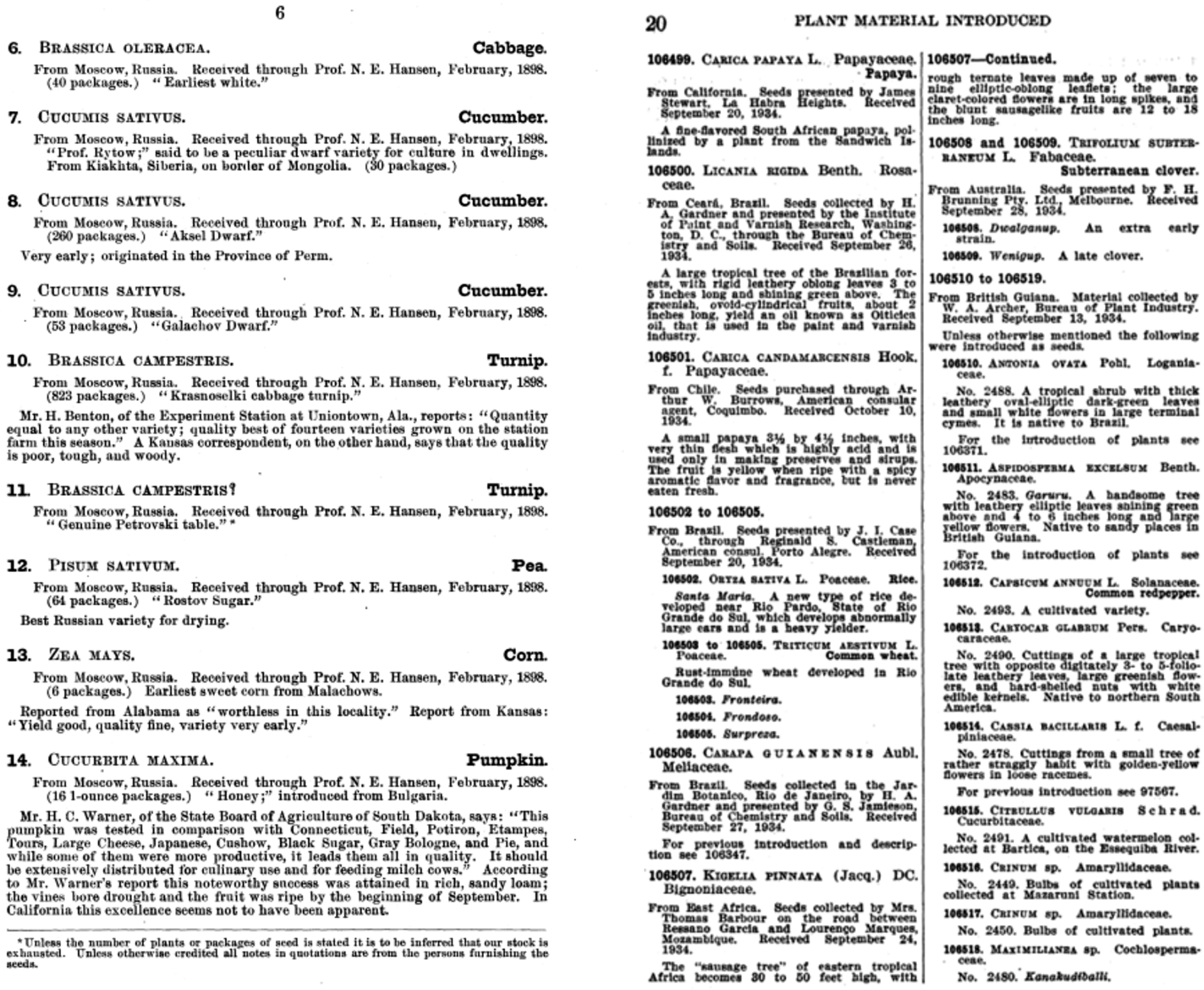

Example A.2. An example where the model is able to capture seed information that spans multiple pages.

INPUT:

OUTPUT:

Rapid Responses

No Rapid Responses have been published for this article.