Introduction

Cash transfer programmes constitute a central pillar of social protection policy worldwide (Brooks, Reference Brooks2015; Ellis, Reference Ellis2012; Slater, Reference Slater2011). Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa have generated substantial evidence documenting their effects on poverty, health, education, and household welfare (Bastagli et al., Reference Bastagli, Hagen-Zanker, Harman, Barca, Sturge and Schmidt2018; Handa et al., Reference Handa, Daidone, Peterman, Davis, Pereira, Palermo and Yablonski2018). These programmes provide direct financial assistance to vulnerable populations, and both theoretical frameworks and empirical findings have accumulated regarding their effectiveness across diverse settings (Bastagli et al., Reference Bastagli, Hagen-Zanker, Harman, Barca, Sturge and Schmidt2018; Daidone et al., Reference Daidone, Davis, Handa and Winters2019; Gentilini, Reference Gentilini2024; Leroy et al., Reference Leroy, Ruel and Verhofstadt2009; Millán et al., Reference Millán, Barham, Macours, Maluccio and Stampini2019).

Evidence on cash transfer effectiveness in the MENA region remains more limited. The region presents distinctive characteristics: high youth unemployment, political instability, ongoing conflicts, large-scale displacement, and widespread energy subsidy systems (Fakih et al., Reference Fakih, Haimoun and Kassem2020; Verme et al., Reference Verme, Gigliarano, Wieser, Hedlund, Petzoldt and Santacroce2015). Moreover, patriarchal family structures and gender norms show considerable variation across countries and socioeconomic strata (Charrad, Reference Charrad2011; Moghadam, Reference Moghadam2003, Reference Moghadam2020). These contextual factors may mediate programme effectiveness in ways that differ from other regions.

Critical questions persist regarding transfer effectiveness in these contexts. Do cash transfers exhibit threshold effects, whereby modest amounts modify behaviour but substantial poverty reduction requires larger sums? How does supply-side service capacity mediate demand-side incentive effectiveness? How do conflict and displacement influence programme sustainability? How do programme design features interact with patriarchal structures to shape women’s empowerment outcomes? This study addresses these gaps through examination of cash transfer impacts on poverty reduction, food security, education, health, and women’s empowerment in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Literature review

Research spanning fifteen to twenty years demonstrates that cash transfers can reduce poverty and improve household consumption across low- and middle-income countries (Bastagli et al., Reference Bastagli, Hagen-Zanker, Harman, Barca, Sturge and Schmidt2018; Handa et al., Reference Handa, Daidone, Peterman, Davis, Pereira, Palermo and Yablonski2018). Studies have identified non-linear relationships between transfer size and outcomes, whereby behavioural changes such as school enrollment may be achievable with modest transfers when strategically framed (Benhassine et al., Reference Benhassine, Devoto, Duflo, Dupas and Pouliquen2015; Glewwe and Kassouf, Reference Glewwe and Kassouf2012; Pedraja-Chaparro et al., Reference Pedraja-Chaparro, Santín and Simancas2022; Peruffo and Ferreira, Reference Peruffo and Ferreira2017; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Jiang and Wang2020), whereas substantial poverty reduction appears to require larger proportions of household income (Handa et al., Reference Handa, Daidone, Peterman, Davis, Pereira, Palermo and Yablonski2018). This evidence base encompasses randomised controlled trials establishing causal impacts (Baird et al., Reference Baird, Ferreira, Özler and Woodcock2014), quasi-experimental designs exploiting policy discontinuities (Aizer et al., Reference Aizer, Eli, Ferrie and Lleras-Muney2016), and qualitative research illuminating mechanisms and lived experiences (Adato and Bassett, Reference Adato and Bassett2009). Detailed quality assessment criteria for systematic reviews typically examine randomisation procedures, identification strategies, sample adequacy, measurement quality, and transparency in reporting (Petticrew and Roberts, Reference Petticrew and Roberts2008).

Beyond direct poverty impacts, extent research has documented important spillover effects across sectors. Education-focused programmes may generate improvements in child nutrition and health as households reallocate resources (Baird et al., Reference Baird, Ferreira, Özler and Woodcock2014), while health-focused transfers have been associated with enhanced educational participation and cognitive development (Awojobi, Reference Awojobi2022; Kessler and Hevenstone, Reference Kessler and Hevenstone2022). These cross-sectoral spillovers suggest that single-objective programmes can produce multi-dimensional welfare gains when household resources are fungible and families face multiple binding constraints simultaneously.

However, emerging evidence also identifies potential counterintuitive and negative effects requiring careful programme design. Gazeaud and Ricard (Reference Gazeaud and Ricard2024) established that demand-side education incentives can paradoxically reduce learning outcomes when supply-side capacity including teacher training, classroom infrastructure, and pedagogical adaptation to heterogeneous learners, fails to accommodate enrollment increases. This finding raises fundamental questions about whether demand-side incentives alone constitute sufficient policy interventions or whether complementary supply-side investments prove necessary for sustained effectiveness. Similarly, gender impacts have proven complex and context-dependent: while some programmes enhance women’s economic participation and decision-making power, others may inadvertently reinforce patriarchal norms when framing women primarily as mothers and caregivers responsible for child welfare (Nagels, Reference Nagels2021, Reference Nagels2024). These mixed findings underscore that programme design features, including conditionality structure, complementary services, framing, targeting mechanisms, and attention to supply-side capacity, may matter as much as transfer size in determining outcomes.

The MENA region presents distinct characteristics potentially influencing cash transfer effectiveness. Political instability, ongoing conflicts, and large-scale displacement have created humanitarian crises (Verme et al., Reference Verme, Gigliarano, Wieser, Hedlund, Petzoldt and Santacroce2015), operating alongside high youth unemployment (Assaad and Krafft, Reference Assaad and Krafft2021), inflation, credit constraints (Abdi and Nor, Reference Abdi and Nor2025), and wealth disparities (Alvaredo et al., Reference Alvaredo, Chancel, Piketty, Saez and Zucman2018). Energy subsidy systems create unique policy environments where cash transfers may compensate subsidy removal while providing social protection (Sdralevich et al., Reference Sdralevich, Sab, Zouhar and Albertin2014; Ianchovichina et al., Reference Ianchovichina, Mottaghi and Devarajan2015). Patriarchal family structures limiting women’s resource control vary considerably across countries and socioeconomic strata (Charrad, Reference Charrad2011; Moghadam, Reference Moghadam2003; Reference Moghadam2020), suggesting heterogeneous programme effects.

Despite these characteristics, systematic evidence remains sparse. Whether transfer effectiveness shows threshold effects requires investigation given diverse cost structures and poverty lines; how supply-side service capacity mediates demand-side incentives could inform programme design to avoid counterproductive outcome; how conflict and displacement influence programme sustainability remains poorly understood despite affecting substantial populations; how programme design interacts with patriarchal structures to shape women’s empowerment warrants examination; implementation challenges across diverse governance systems from Gulf monarchies to fragile states, require investigation regarding corruption, targeting, and political economy factors (Hickey and Sen, Reference Hickey and Sen2024). Methodological rigor varies considerably, raising questions about causal claim reliability and generalisability from well-studied contexts to understudied countries (Bastagli et al., Reference Bastagli, Hagen-Zanker, Harman, Barca, Sturge and Schmidt2018).

Theoretical framework

This study draws on economic, behavioural, and gender theories to guide systematic analysis of how cash transfers may influence socioeconomic outcomes in MENA contexts, with particular attention to mechanisms that may operate differently given the region’s unique characteristics.

Economic theories of cash transfers

Economic models posit that cash transfers relax household budget constraints, enabling optimal consumption choices and human capital investments (Cruz and Ziegelhofer, Reference Cruz and Ziegelhofer2014; Egger et al., Reference Egger, Haushofer, Miguel, Niehaus and Walker2022; Enami et al., Reference Enami, Lustig and Taqdiri2019). Under these models, transfers provide immediate financial relief allowing households to meet basic needs such as food, healthcare, and education while potentially facilitating longer-term investments in children’s human capital (Aurino and Giunti, Reference Aurino and Giunti2022; Fiszbein et al., Reference Fiszbein, Ringold and Srinivasan2011; Slater, Reference Slater2011). However, poverty trap theories suggest more complex dynamics characterised by threshold effects: below certain transfer levels, households cannot escape subsistence constraints and behavioural poverty traps that perpetuate intergenerational poverty, whereas above these thresholds, marginal returns may diminish as households approach optimal consumption patterns (Barrett and Carter, Reference Barrett and Carter2013; Carter, Reference Carter, Barrett, Carter and Chavas2019; Sindzingre, Reference Sindzingre2012).

The ‘cash plus’ concept extends this framework by combining regular cash transfers with additional components or linkages that seek to augment income effects and achieve more sustainable impacts than cash alone (Austrian et al., Reference Austrian, Soler-Hampejsek, Kangwana, Wado, Abuya and Maluccio2021; Field and Maffioli, Reference Field and Maffioli2021; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Marsden and Quarterman2022; Leight et al., Reference Leight, Hirvonen and Zafar2024; Little et al., Reference Little, Roelen, Lange, Steinert, Yakubovich, Cluver and Humphreys2021; Maara et al., Reference Maara, Attree, Pavisic, Kalokhe, Karanja, Magongo, Musuva, Mwangi, Njue, Weiner and Maman2023; Olney et al., Reference Olney, Bliznashka, Pedehombga, Dillon, Ruel and Heckert2022; Roelen et al., Reference Roelen, Devereux, Abdulai, Martorano, Palermo and Ragno2017). These complementary interventions recognise that households face multiple binding constraints simultaneously including inadequate service quality, legal restrictions on employment, market failures, discrimination, and weak institutional capacity that financial resources alone cannot overcome. Cash plus approaches take diverse forms: graduation programmes focusing on economic outcomes through asset accumulation and livelihood investments, typically time-bound with predetermined poverty exit trajectories; and socioeconomic-focused programmes addressing nutrition, behaviour change, empowerment, or violence reduction without strict time limits (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Roelen, Enfield and Avis2019). Complementary components range from behaviour change communication and psychosocial support to in-kind benefits and service linkages, targeting both individual action and structural barriers (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Roelen, Enfield and Avis2019; Pruce et al., Reference Pruce, Price and Sabates-Wheeler2025).

Economic theories must also account for political economy factors shaping programme design and implementation. Patronage dynamics, corruption risks, and state legitimacy building through welfare provision influence both how programmes are structured and how effectively they reach intended beneficiaries (Morsi, Reference Morsi2023; Merouani et al., Reference Merouani, Messekher, Hamaizia and Ait Belkacem2023). These political economy dimensions prove particularly relevant in MENA’s diverse governance contexts ranging from authoritarian regimes using social protection to build popular support to fragile states where institutional weakness constrains implementation capacity.

These economic frameworks become testable when examining threshold effects across MENA countries with vastly different cost structures, wage levels, and poverty lines from resource-rich Gulf states to conflict-affected fragile states. Region-specific structural barriers including ongoing conflicts, large-scale displacement generating legal restrictions on refugee employment, and governance challenges (El-Abed et al., Reference El-Abed, Najdi and Hoshmand2023; Fakhoury, Reference Fakhoury2019; Kalush and Lambert, Reference Kalush, Lambert, Lambert and Elayah2023) affecting implementation provide natural experiments for evaluating the impact of cash transfer.

Behavioural economics and framing effects

Behavioural economics provides additional insights into transfer effectiveness through theories of framing effects, mental accounting, and nudging. Research demonstrating that labeled but unconditional transfers generate behavioural changes comparable to conditional transfers indicates that psychological mechanisms not merely material incentives or enforcement of conditionalities can drive behaviour change (Benhassine et al., Reference Benhassine, Devoto, Duflo, Dupas and Pouliquen2015; Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer, Scullion, Jones, McNeill and Stewart2022). Furthermore, extent literature suggest that cash transfers can reduce financial stress (Owusu-Addo et al., Reference Owusu-Addo, Renzaho and Smith2018), enabling beneficiaries to make more rational decisions about resource allocation, savings, and investment (Nnaeme, Reference Nnaeme2021) rather than remaining trapped in survival-mode decision-making characterised by high discount rates and risk aversion (Acland, Reference Acland2021; Allen et al., Reference Allen, Gilligan, Kurdi and Yassa2024; Mullainathan and Shafir, Reference Mullainathan and Shafir2013; Slater, Reference Slater2011).

Whether framing effects documented elsewhere achieve similar impacts in the MENA region remains an empirical question given distinct cultural norms around conditionality, state authority, and household decision-making processes. More critically, the supply-side capacity constraint mechanism becomes particularly salient in contexts experiencing rapid programme expansion despite limited institutional capacity. Documented cases of enrollment surges in education systems or increased health service utilisation in under-resourced facilities provide opportunities to examine whether the predicted quality degradation materialises, potentially explaining counterintuitive outcomes where access improvements coincide with effectiveness declines.

Gender theory and empowerment dynamics

Feminist scholarship argues that economic resources constitute necessary but insufficient conditions for gender equity and women’s empowerment (Kabeer, Reference Kabeer1999). Empowerment requires addressing both practical needs through income provision and strategic interests through challenging gender norms, power relations, and structural barriers that constrain women’s agency (Mosedale, Reference Mosedale2005; Saluja et al., Reference Saluja, Singh and Kumar2023). When cash transfer programmes frame women primarily as mothers and caregivers responsible for child welfare, they may reinforce rather than challenge patriarchal structures by enhancing women’s value within traditional roles while failing to expand their authority in non-caregiving domains or decision-making spheres beyond childcare (Tabbush, Reference Tabbush2010). This theoretical lens suggests examining not only whether women receive transfers but how programme design mediates impacts on women’s decision-making authority, economic participation, mobility, and agency across multiple domains (Alcázar et al., Reference Alcázar, Balarin and Espinoza Iglesias2016).

These feminist frameworks provide analytical tools for interpreting how programme design features including framing strategies, conditionality structures, and complementary interventions, interact with patriarchal structures, legal frameworks, and social norms to shape empowerment outcomes. Given that MENA contexts exhibit considerable variation in gender dynamics across countries and socioeconomic strata (Solomon and Tausch, Reference Solomon, Tausch, Solomon and Tausch2021; Madi et al., Reference Madi, Morales, Yosef and Andreosso2023), these frameworks guide examination of when and how cash transfers promote versus constrain women’s agency within different configurations of gender inequality.

Methods

Procedures

This study conducted a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald and Moher2021) to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and systematicness in identifying and synthesising evidence concerning cash transfer programmes in the MENA region.

Search strategy

We undertook exhaustive searches across multiple electronic databases and institutional repositories to identify relevant studies published between January 2000 and December 2024. Databases included Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, EconLit, JSTOR, Google Scholar, and specialised sources such as the World Bank Open Knowledge Repository, UNICEF publications database, UNHCR evaluation repository, WFP evaluation database, and websites of key research institutions operating in social protection within the MENA region (including IFPRI, ODI, ERF, and ESCWA). Search terms combined three conceptual groups using Boolean operators: intervention terms, including ‘cash transfer’, ‘cash assistance’, ‘cash-based transfer’, ‘social protection’, ‘safety net’,‘conditional cash’, ‘unconditional cash’, ‘cash for work’, and ‘multipurpose cash’; outcome terms, encompassing ‘poverty’, ‘education’, ‘health’, ‘nutrition’, ‘employment’, ‘empowerment’, ‘wellbeing’, and ‘food security’; and geographic terms, including ‘MENA’, ‘Middle East’, ‘North Africa’, and the names of all twenty-one MENA countries. We further complemented these searches with backward citation tracking and forward citation tracking (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019; Booth et al., Reference Booth, Sutton, Clowes and Martyn-St James2021; Greenhalgh and Peacock, Reference Greenhalgh and Peacock2005). Additionally, we contacted researchers and implementing agencies to obtain grey literature, unpublished evaluations, and ongoing studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility for inclusion was determined based on the following criteria: populations located within MENA countries, including nationals, refugees, internally displaced persons, or other vulnerable groups; interventions involving cash transfer programmes of any modality (conditional, unconditional, labeled, multipurpose, cash-for-work, emergency cash assistance, or social pensions); reported outcomes relating to poverty, education, health, nutrition, employment, empowerment, social cohesion, or other welfare indicators; empirical study designs, including experimental, quasi-experimental, qualitative, mixed-methods, descriptive, or monitoring data; publication in English, Arabic, or French; and publication dates between January 2000 and December 2024. Studies were excluded if they: examined exclusively in-kind transfers or vouchers without a cash component; focused solely on contributory social insurance programmes without a non-contributory cash transfer element; were purely theoretical or model-based without empirical data; did not include enough methodological information to allow for quality assessment and data extraction.

Screening and selection process

Database search generated an initial corpus of 1,463 records. Upon eliminating 507 duplicate entries, two independent reviewers conducted title and abstract appraisal of the residual 956 citations. Citations manifestly failing to satisfy eligibility requirements were discarded, yielding a subset of 622 publications. Subsequently, dual reviewers scrutinised these publications against the inclusion criteria, with divergent assessments reconciled via consensus deliberation or, when requisite, adjudication by an additional reviewer. This protocol ultimately identified 270 studies. Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA flowchart.

Figure 1. Flow chart of study selection.

Data extraction

A standardised extraction form was developed and pilot-tested on ten studies prior to full implementation. For each included study, we extracted: bibliographic information (authors, year, title, publication type); study characteristics (country, study design, methodology, sample size, data collection period); programme characteristics (programme name, implementing agency, type, target population, transfer amounts in local currency and USD, frequency, conditionality, complementary services); outcomes (primary and secondary measures, measurement tools, follow-up periods); key findings (effect sizes, main results, subgroup analyses); and implementation features (targeting mechanisms, payment delivery methods, monitoring systems, reported challenges). Trained reviewers conducted extraction, with 20 per cent of studies double-extracted to ensure reliability, and discrepancies were reconciled through discussion.

Quality assessment

We assessed the methodological quality of all 270 studies using criteria appropriate to each study design, following best practices for systematic reviews of complex interventions (Petticrew and Roberts, Reference Petticrew and Roberts2008). For experimental studies (RCTs, n = 22), we evaluated randomisation procedures, baseline balance, attrition, outcome measurement, statistical power, spillovers, pre-registration, and robustness checks, classifying studies meeting ≥6 of 8 criteria as high quality, including Benhassine et al. (Reference Benhassine, Devoto, Duflo, Dupas and Pouliquen2015) on Morocco’s Tayssir programme and Ecker et al. (Reference Ecker, Al-Malk and Maystadt2024) on Yemen’s Social Welfare Fund. Similarly, quasi-experimental studies (n = 32) were assessed on identification strategy credibility, baseline comparability, falsification tests, robustness checks, outcome measurement, sample size, and transparency (≥5 of 7 for high quality), such as El-Enbaby et al.’s (Reference El-Enbaby, Hollingsworth, Maystadt and Singhal2024) regression discontinuity evaluation of Egypt’s Takaful programme.

Mixed-methods studies (n = 13) were evaluated using Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)-adapted criteria on integration, component quality, sampling, triangulation, and transparency, with high-quality examples including Presler-Marshall’s (Reference Presler-Marshall, Jones, Luckenbill, Alheiwidi, Baird and Oakley2024) Hajati evaluation, while qualitative studies (n = 111) were assessed using CASP-adapted criteria on research design, sampling, data collection, analysis, reflexivity, credibility, and transferability (≥5 of 7 for high quality), including Ulrichs et al.’s (Reference Ulrichs, Hagen-Zanker and Holmes2017) study of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) cash assistance in Jordan and Presler-Marshall et al.’s (Reference Presler-Marshall, Jones, Luckenbill, Alheiwidi, Baird and Oakley2024) study of adolescent girls’ experiences. Survey and descriptive studies (n = 135) were evaluated on sampling, response rates, measurement, data quality, analysis, and transparency, whereas meta-analyses and reviews (n = 10) were assessed using A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR-2) criteria, including Garcia and Saavedra’s (Reference Garcia and Saavedra2017) meta-analysis of conditional cash transfers, and economic modeling studies (n = 10) were evaluated on model appropriateness, data quality, assumptions, sensitivity analysis, validation, and transparency. Overall, we classified 22 per cent (60 studies) as high quality, 45 per cent (122 studies) as moderate quality, and 33 per cent (88 studies) as lower quality, with high-quality studies concentrated among experimental and quasi-experimental designs and lower-quality studies more common among descriptive reports and grey literature. We weighted findings accordingly, with high-quality experimental and quasi-experimental studies providing strongest causal evidence while lower-quality descriptive studies provided contextual information and hypothesis generation, with complete assessments in Supplementary Table S4.

Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis was deemed more appropriate than meta-analysis given the substantial variability observed in study methodologies, intervention types, contextual factors, and outcome assessment methods (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, McKenzie, Sowden, Katikireddi, Brennan, Ellis and Thomson2020). Findings were organised thematically by outcome domains (education, health/nutrition, poverty/consumption, employment, empowerment, etc.) and by programme type (conditional cash transfer (CCT), unconditional cash transfer (UCT), humanitarian cash, etc.). Within each domain, we identified patterns, explored sources of variation, and evaluated the strength of evidence, taking into account study quality, consistency of findings, and contextual characteristics. Particular attention was devoted to understanding why similar interventions yielded different outcomes across contexts, considering transfer size, programme design, implementation quality, complementary services, supply-side capacity, and structural barriers.

Results

Programme types and coverage

The 270 studies reviewed encompass a broad spectrum of cash transfer modalities (see Supplementary Table S1). General or multiple programme types constitute 56.30 per cent (152 studies), reflecting research that examines social protection systems broadly, compares multiple modalities, or does not focus on a specific cash transfer design. CCTs account for 22.59 per cent (sixty-one studies), including Morocco’s Tayssir and Egypt’s Takaful programmes, which condition transfers on school attendance and health service utilisation. UCTs represent 14.81 per cent (forty studies), including Yemen’s Social Welfare Fund and humanitarian assistance programmes that provide transfers without behavioural conditions. Multi-purpose or refugee cash transfers are featured in 12.22 per cent (thirty-three studies), such as UNHCR support for Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. Cash-for-work programmes constitute 6.30 per cent (seventeen studies), and labeled cash transfers (LCTs), representing a distinct educational purpose without conditionality, appear in only 0.37 per cent (one study). Percentages sum to more than 100 per cent due to studies examining multiple modalities.

Methodological approaches

Methodologies vary considerably, reflecting differing research objectives, resources, and contextual constraints (see Supplementary Table S1). Survey-based and descriptive studies comprise 50.00 per cent (135 studies), including cross-sectional surveys, monitoring reports, and programme evaluations describing programme features, beneficiary characteristics, and reported outcomes. Qualitative approaches are featured in 41.11 per cent (111 studies), employing interviews, focus groups, and case studies to provide rich contextual insight into implementation processes, beneficiary experiences, and mechanisms of change. Descriptive reviews and policy analyses account for 17.78 per cent (forty-eight studies), systematically contextualising social protection systems and programme design.

Quasi-experimental designs constitute 11.85 per cent (thirty-two studies), utilising regression discontinuity, difference-in-differences, propensity score matching, and fixed-effects panel models for credible causal identification without randomisation. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) account for 8.15 per cent (twenty-two studies). Mixed-methods studies comprise 4.81 per cent (thirteen studies), triangulating quantitative and qualitative data. Economic modelling approaches, including computable general equilibrium and microsimulation, are used in 3.70 per cent (ten studies), examining macroeconomic and fiscal impacts. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews account for 3.70 per cent (ten studies), synthesising findings across multiple studies, and post-distribution monitoring (PDM) constitutes 2.22 per cent (six studies), primarily by operational agencies. These percentages exceed 100 per cent because many studies employ multiple methods. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs (19.99 per cent) provide the strongest causal evidence, while qualitative and descriptive studies supply essential contextual understanding of programme mechanisms and implementation dynamics.

Transfer amounts and design features

The effectiveness of cash transfer programmes in the MENA region is closely linked to transfer size, though outcomes are mediated by programme design, context, and complementary services. Across 270 studies, approximately 40 per cent report specific transfer amounts, and only 20 per cent contextualise transfers relative to household income or expenditure (Supplementary Table S2). Transfer levels vary substantially, reflecting programme objectives, fiscal constraints, and local economic conditions.

Transfer amounts across programmes

Transfers range from small, behavioural incentives to large humanitarian support. Morocco’s Tayssir programme provides 60–140 MAD ($8–$18 USD) per month (∼5 per cent of household expenditure), achieving 70 per cent reduction in dropout rates and 85per cent re-enrollment (Benhassine et al., Reference Benhassine, Devoto, Duflo, Dupas and Pouliquen2015). Egypt’s Takaful and Karama programmes deliver 325–625 EGP ($21–$40 USD), ∼6 per cent of income for the poorest decile, producing measurable poverty reduction and improved consumption (El-Enbaby et al., Reference El-Enbaby, Hollingsworth, Maystadt and Singhal2024; Breisinger et al., Reference Breisinger, Passim, Kurds, Randriamamonjy and Thurlow2023). Jordan’s Hajati programme provides 20 JOD per child ($28 USD), ∼15–20 per cent of household income, improving school participation, nutrition, and psychosocial wellbeing (Presler-Marshall et al., Reference Presler-Marshall, Jones, Luckenbill, Alheiwidi, Baird and Oakley2024). Humanitarian transfers in Lebanon and Jordan are larger ($80–$175, 40–60 per cent of household income) but benefits fade four to ten months post-programme (Masterson, Reference Masterson2016; Chaaban et al., Reference Chaaban, Salti, Ghattas, Moussa, Irani, Jamaluddine and Al-Mokdad2020). Yemen’s Social Welfare Fund, though irregular ($60–$80 quarterly), mitigates 42–43 per cent of child malnutrition in crisis conditions (Ecker et al., Reference Ecker, Al-Malk and Maystadt2024). Tunisia’s PNAFN provides 70–180 TND ($23–$60), ∼10–15 per cent of household expenditure, yielding modest poverty reduction (Ianchovichina et al., Reference Ianchovichina, Mottaghi and Devarajan2015). Saudi Arabia’s Citizen Account Program offers 300–1,000 SAR ($80–$267 USD), cushioning subsidy reform impacts while supporting fiscal sustainability (Alsayyad and Nawar, Reference Alsayyad and Nawar2017).

Relationship between transfer size and outcomes

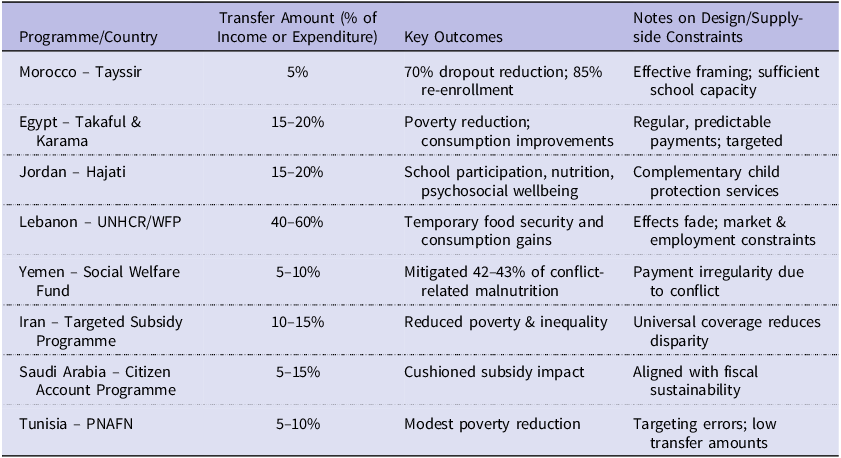

Findings indicate a non-linear, context-dependent relationship between transfer amount and impact (Table 1). Behavioural outcomes, such as school enrollment or health service utilisation, can be achieved with small transfers (5–10 per cent of household income/expenditure) if transfers are strategically framed and supply-side capacity exists. Morocco illustrates this pattern: modest transfers labeled as education support yielded dramatic enrollment gains, though class-size increases slightly reduced learning outcomes (Gazeaud and Ricard, Reference Gazeaud and Ricard2024). Poverty reduction and multi-dimensional welfare improvements generally require larger transfers (15–20 per cent), as in Egypt’s Takaful and Jordan’s Hajati programmes (Breisinger et al., Reference Breisinger, Passim, Kurds, Randriamamonjy and Thurlow2023; Presler-Marshall et al., Reference Presler-Marshall, Jones, Małachowska and Oakley2022, Reference Presler-Marshall, Jones, Luckenbill, Alheiwidi, Baird and Oakley2024). In humanitarian contexts, even generous transfers (40–60 per cent) may temporarily improve consumption but fail to generate sustainable livelihood effects (Masterson, Reference Masterson2016; Chaaban et al., Reference Chaaban, Salti, Ghattas, Moussa, Irani, Jamaluddine and Al-Mokdad2020). Programme design features, predictable payments, complementary services, labeling, and supply-side investments, are often as important as transfer size. For example, Tunisia’s cash-plus-training interventions enhanced female entrepreneurship beyond the effects of cash alone (Fitouri and Zouaoui, Reference Fitouri and Zouaoui2024; Leight and Mvukiyehe, Reference Leight and Mvukiyehe2025). Conversely, neglecting supply-side constraints can undermine outcomes: Morocco’s surge in enrollment slightly reduced test scores, and humanitarian assistance in Lebanon and Jordan could not create employment where legal barriers existed (Gazeaud and Ricard, Reference Gazeaud and Ricard2024; Altındağ and O’Connell, Reference Altındağ and O’Connell2023). Table 1 consolidates key programmes, transfer amounts, outcomes, and design considerations, highlighting the non-linear and context-specific nature of cash transfer effectiveness.

Table 1. Cash transfer programmes in MENA: transfer amounts, programme design, and key outcomes

The findings from this study shows that transfer amounts should align with programme objectives: small transfers suffice for behavioural incentives, moderate transfers for poverty reduction and multi-dimensional welfare, and larger transfers for acute humanitarian needs. Programme design including framing, predictability, complementary services, and supply-side support is crucial for sustained impact. Additionally, contextual factors determine the optimal transfer size, and demand-side interventions must be paired with adequate supply-side capacity to avoid counterproductive effects.

Impact of cash transfers in the MENA region

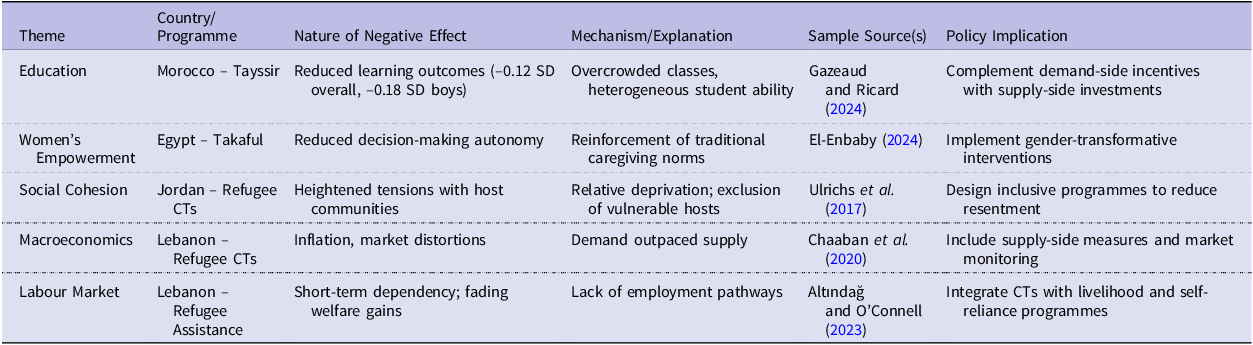

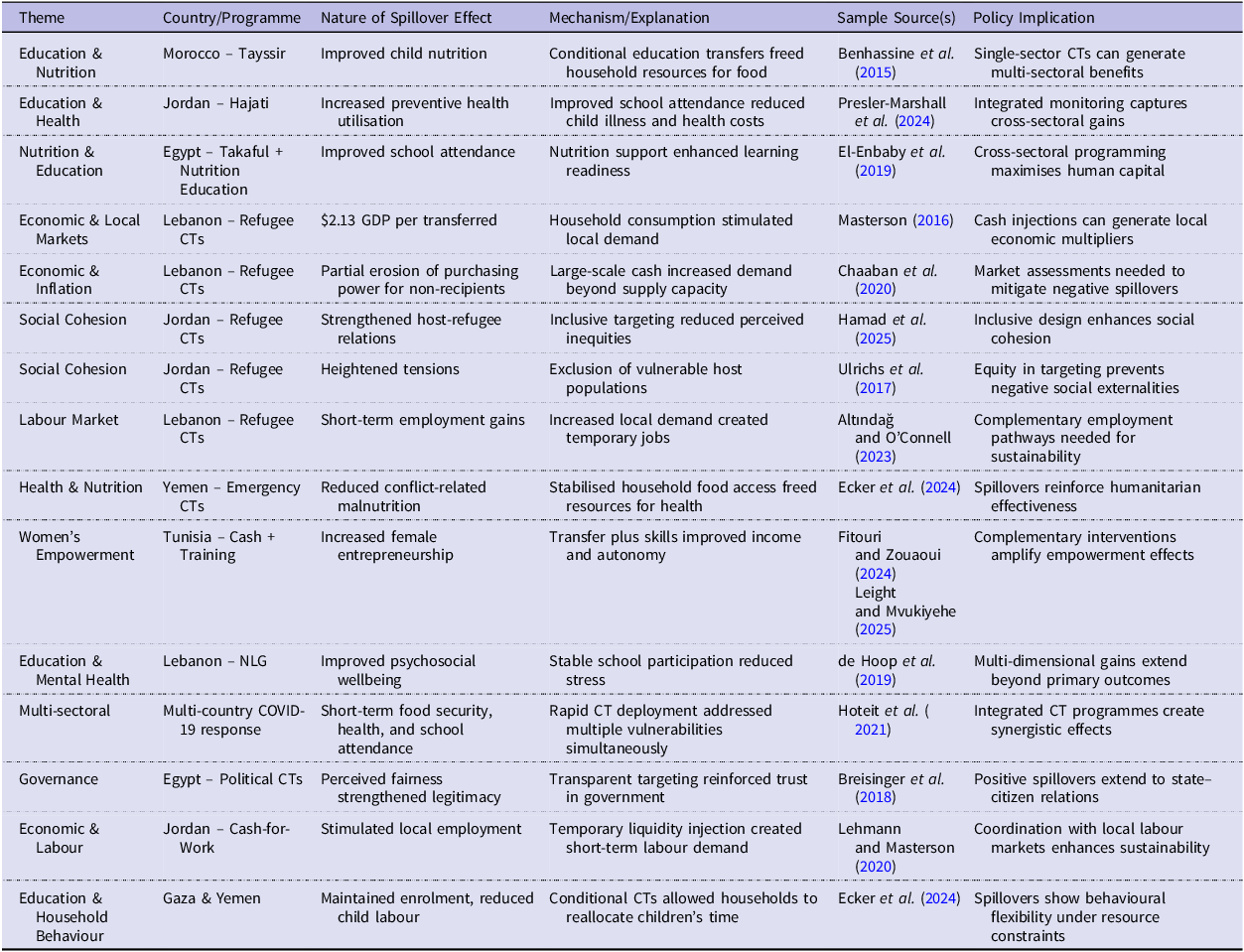

The findings from this study reveal a complex evidence base spanning diverse contexts, programme types, and outcomes. Cash transfer programmes, ranging from national poverty reduction schemes to humanitarian assistance for displaced populations, have demonstrated measurable impacts on education, health, nutrition, poverty reduction, social protection, and labour market outcomes. Concurrently, these interventions reveal implementation challenges, counterintuitive effects, and context-specific dependencies, which must be considered for realistic programme design and evaluation. Positive and neutral impacts are synthesised in Table 2, negative or counterintuitive effects in Table 3, and indirect or spillover effects are presented in Table 4.

Table 2. Positive and neutral impacts of cash transfers in the MENA region

Table 3. Counterintuitive and negative effects of cash transfers in the MENA region

Table 4. Indirect and spillover effects of cash transfers in the MENA region

Economic impacts: poverty, consumption, and inequality

Cash transfers generally reduce poverty and enhance household consumption, though effects depend on transfer size, targeting mechanisms, and contextual factors. In Egypt, Takaful and Karama transfers of EGP 325–625 per month (∼6 per cent of household income) significantly increased consumption and reduced poverty near eligibility thresholds (El-Enbaby et al., Reference El-Enbaby, Hollingsworth, Maystadt and Singhal2024). Breisinger et al. (Reference Breisinger, Passim, Kurds, Randriamamonjy and Thurlow2023) modelled replacing universal food subsidies with targeted transfers, finding that 15–20 per cent of income would be required for substantial poverty reduction. In Iran, the Targeted Subsidy Programme reduced poverty and inequality among lower-income deciles (Enami et al., Reference Enami, Lustig and Taqdiri2019; Zarepour & Wagner, Reference Zarepour and Wagner2022). Tunisia’s PNAFN, transferring 70–180 TND per quarter, produced modest poverty reduction but experienced targeting errors (Ianchovichina et al., Reference Ianchovichina, Mottaghi and Devarajan2015). Morocco’s Tayssir programme, primarily education-focused, improved household consumption even with transfers representing only 5 per cent of expenditure (Benhassine et al., Reference Benhassine, Devoto, Duflo, Dupas and Pouliquen2015; Ben Haman, Reference Ben Haman2025). Humanitarian transfers to Syrian refugees in Lebanon ($80–175/month) improved consumption and food security temporarily, though effects faded four to ten months post-programme (Chaaban et al., Reference Chaaban, Salti, Ghattas, Moussa, Irani, Jamaluddine and Al-Mokdad2020; Altındağ and O’Connell, Reference Altındağ and O’Connell2023).

Energy subsidy reforms indicate the interplay of CTs with policy context: Saudi Arabia’s Citizen Account Programme cushioned subsidy impacts while improving fiscal sustainability (Moerenhout, Reference Moerenhout2017), whereas Algerian reforms were undermined by corruption (Merouani et al., Reference Merouani, Messekher, Hamaizia and Ait Belkacem2023; Morsi, Reference Morsi2023). Across contexts, transfers representing 5–10 per cent of household income improve consumption and reduce poverty severity, whereas 15–20 per cent can lift households substantially above poverty thresholds. Proxy means testing enhances targeting efficiency but risks exclusion errors; universal transfers ensure inclusion but entail high fiscal costs. Complementary policies in health, education, and economic opportunity further enhance CT effectiveness (Table 2).

Education and child welfare: enrollment, attendance, and learning

Education-focused cash transfers typically increase enrolment and attendance but present mixed effects on learning outcomes. Morocco’s Tayssir programme reduced dropout by 70 per cent and re-enrolment increased by 85 per cent, achieving significant educational access gains (Benhassine et al., Reference Benhassine, Devoto, Duflo, Dupas and Pouliquen2015). However, Gazeaud and Ricard (Reference Gazeaud and Ricard2024) documented a reduction in test scores by 0.12 SD overall and 0.18 SD for boys due to supply-side overwhelm: the influx of students increased class sizes and heterogeneity, overwhelming teachers’ capacity (Table 3). Jordan’s Hajati programme improved school participation by four percentage points while enhancing nutrition and psychosocial wellbeing (Table 2). Lebanon’s No Lost Generation programme raised attendance by 20 per cent among enrolled Syrian refugee children, but had limited effect on initial enrolment (de Hoop et al., Reference De Hoop, Morey and Seidenfeld2019). In Gaza and Yemen, cash transfers temporarily maintained enrolment and reduced child labour during crises (Ecker et al., Reference Ecker, Al-Malk and Maystadt2024). These findings show that enrolment and learning are distinct objectives: small transfers (5–10 per cent of income) can drive behavioural change, but complementary investment in teacher training, infrastructure, and pedagogical support is necessary to sustain learning outcomes (Tables 2 and 3).

Health, nutrition, and food security

Cash transfers consistently improve nutrition, food security, and health outcomes across stable and crisis contexts. In Yemen, transfers mitigated 42–43 per cent of conflict-related nutritional declines (Ecker et al., Reference Ecker, Al-Malk and Maystadt2024; Table 2). Somalia’s cash and voucher programmes enhanced nutrition and provided flexibility without diversion (Doocy et al., Reference Doocy, Busingye, Lyles, Colantouni, Aidam, Ebulu and Savage2020). Lebanon’s humanitarian cash assistance improved dietary diversity and wellbeing during programme delivery but faded post-assistance (Battistin, Reference Battistin2016; Chaaban et al., Reference Chaaban, Salti, Ghattas, Moussa, Irani, Jamaluddine and Al-Mokdad2020; Table 3). Jordan showed similar short-term improvements (Altındağ and O’Connell, Reference Altındağ and O’Connell2023). Egypt’s Takaful improved dietary diversity, enhanced when combined with nutrition education (El-Enbaby et al., Reference El-Enbaby, Gilligan, Karachiwalla, Kassim and Kurdi2019, Reference El-Enbaby, Hollingsworth, Maystadt and Singhal2024). Health outcomes included increased preventive care utilisation (Rashad and Sharaf, Reference Rashad and Sharaf2017) and modest mental health gains (El-Enbaby, Reference El-Enbaby, Hollingsworth, Maystadt and Singhal2024). These results highlight that cash transfers prevent catastrophic coping, with benefits fading after cessation unless supplemented with complementary interventions (Tables 2 and 3).

Indirect and spillover effects

The findings from this study show additional categories of indirect and spillover effects. Cross-sectoral spillovers are common: education-focused cash transfers (Morocco’s Tayssir, Jordan’s Hajati) produced nutrition and health benefits beyond their primary enrolment objectives, while nutrition-focused interventions (Egypt’s Takaful with nutrition education) improved school attendance (Presler-Marshall et al., Reference Presler-Marshall, Jones, Luckenbill, Alheiwidi, Baird and Oakley2024; El-Enbaby et al., Reference El-Enbaby, Gilligan, Karachiwalla, Kassim and Kurdi2019). This indicates that single-sector interventions can generate multi-sectoral benefits when household resources are fungible and families face multiple binding constraints simultaneously.

Temporal dynamics of spillovers are critical. Immediate spillovers (consumption increases, food security improvements) occur during programme implementation but fade rapidly after programme cessation (Chaaban et al., Reference Chaaban, Salti, Ghattas, Moussa, Irani, Jamaluddine and Al-Mokdad2020; Altındağ and O’Connell, Reference Altındağ and O’Connell2023). In contrast, human capital spillovers (education, health) may take years to materialise and persist longer, though evidence on long-term effects is limited. Only 5–10 per cent of studies include follow-up beyond three years, leaving the sustainability of spillover effects poorly understood.

Spillovers can be positive or negative depending on context. Economic multipliers in Lebanon ($2.13 GDP per dollar transferred) benefited host communities (Masterson, Reference Masterson2016), whereas inflationary pressures from large-scale cash assistance partially eroded purchasing power for non-recipients (Chaaban et al., Reference Chaaban, Salti, Ghattas, Moussa, Irani, Jamaluddine and Al-Mokdad2020). Inclusive programming benefiting both refugees and host communities in Jordan strengthened social cohesion (Hamad et al., Reference Hamad, Jones, Abuhamad, Baird and Oakley2025), while perceived inequitable treatment in some contexts exacerbated tensions (Ulrichs et al., Reference Ulrichs, Hagen-Zanker and Holmes2017). Spillovers also interact with local economic conditions and market structure: in contexts with excess capacity and unemployment, cash injections stimulated local demand and employment without inflation; in contexts with supply constraints or thin markets, cash assistance contributed to price increases, partially offsetting benefits.

Measurement of spillovers remains limited. Most evaluations focus on direct beneficiary outcomes, with only a minority (∼15 per cent of studies) explicitly measuring effects on non-beneficiaries, local economies, or broader social outcomes. This measurement gap likely leads to underestimation of programme impacts and constrains understanding of optimal programme design to maximise positive externalities. These indirect and spillover effects are summarised in Table 4, which captures the type, direction, mechanism, and policy implications across education, health, economic, gender, and social cohesion outcomes.

Women’s empowerment and gender dynamics

The findings show that cash transfers alone do not guarantee women’s empowerment. Egypt’s Takaful increased women’s decision-making initially, but El-Enbaby (Reference El-Enbaby, Hollingsworth, Maystadt and Singhal2024) indicated that transfers reduced influence over child healthcare decisions, particularly among less-educated women (Table 3). Tunisia’s cash plus business training enabled female entrepreneurship (Fitouri and Zouaoui, Reference Fitouri and Zouaoui2024; Leight and Mvukiyehe, Reference Leight and Mvukiyehe2025). Jordan’s Hajati programme improved girls’ wellbeing and reduced early marriage, though education impacts were gender-differentiated (Presler-Marshall et al., Reference Presler-Marshall, Jones, Luckenbill, Alheiwidi, Baird and Oakley2024). Lebanon and Palestine observed improvements in economic wellbeing but persistent limitations in decision-making and community participation (Ulrichs et al., Reference Ulrichs, Hagen-Zanker and Holmes2017). These outcomes underscore that programme design, complementary interventions, education, and prevailing social norms critically shape empowerment results (Tables 2–4).

Refugee and humanitarian assistance

Cash transfers addressing immediate needs for refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, and displaced populations in Iraq, Palestine, Yemen, Syria, and Libya enhanced consumption, food security, and generated local economic multipliers (Masterson, Reference Masterson2016; Chaaban et al., Reference Chaaban, Salti, Ghattas, Moussa, Irani, Jamaluddine and Al-Mokdad2020; Altındağ and O’Connell, Reference Altındağ and O’Connell2023; Table 2). However, cash assistance can exacerbate social tensions when host communities perceive unequal treatment (Ulrichs et al., Reference Ulrichs, Hagen-Zanker and Holmes2017; Table 3). Inclusive programme design, targeting both refugees and vulnerable host communities, is essential to prevent social divisions. Spillover effects across host–refugee communities are highlighted in Table 4, showing both positive synergies and negative tensions.

Labour market and employment impacts

Cash transfers rarely reduce labour supply. Egypt’s Takaful increased female labour participation when credit constraints were relaxed (El-Enbaby et al., Reference El-Enbaby, Gilligan, Karachiwalla, Kassim and Kurdi2019; Table 2), while pensions influenced labour differently by type and age (Cuong and Arouri, Reference Cuong and Arouri2018). Cash-for-work in Jordan provided temporary income but not sustained employment (Lehmann and Masterson, Reference Lehmann and Masterson2020), and Syrian refugees in Lebanon continued job-seeking despite assistance (Altındağ and O’Connell, Reference Altındağ and O’Connell2023; Table 3). Tunisia’s cash plus training increased female entrepreneurship (Fitouri and Zouaoui, Reference Fitouri and Zouaoui2024; Leight and Mvukiyehe, Reference Leight and Mvukiyehe2025). Spillovers on local labour markets, such as multiplier effects or price distortions, are also captured in Table 4.

Socio-political impacts and governance

Cash transfers influence state–citizen relations, political behaviour, and governance quality. Egypt’s programmes increased support for incumbents, reflecting patronage (Breisinger et al., Reference Breisinger, ElDidi, El-Enbaby, Gilligan, Karachiwalla, Kassim, Kurdi and Thai2018; El-Enbaby et al., Reference El-Enbaby, Gilligan, Karachiwalla, Kassim and Kurdi2019; Table 2). Algeria’s corruption reduced programme effectiveness (Merouani et al., Reference Merouani, Messekher, Hamaizia and Ait Belkacem2023; Morsi, Reference Morsi2023; Table 2). Inclusive targeting in Jordan maintained cohesion between refugees and nationals (Presler-Marshall et al., Reference Presler-Marshall, Jones, Luckenbill, Alheiwidi, Baird and Oakley2024), while Lebanon’s fragile governance limited delivery and legitimacy (Ulrichs et al., Reference Ulrichs, Hagen-Zanker and Holmes2017). Yemen’s politicised assistance and Palestine’s blockade indicate context-specific barriers to effectiveness (Ecker et al., Reference Ecker, Al-Malk and Maystadt2024). Spillover effects from social cohesion interventions and local economic multipliers are detailed in Table 3, highlighting the importance of transparency, fairness, and monitoring in programme design.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal a complex evidence landscape that challenges simplistic assumptions about cash transfer effectiveness in the MENA region. While programmes demonstrate measurable impacts across poverty reduction, education, nutrition, and humanitarian assistance, the findings exposes significant limitations, counterintuitive effects, and contextual dependencies demanding careful interpretation.

The fallacy of universal transfer amounts

The findings contradict conventional donor practices of replicating transfer amounts across settings based on successful programmes elsewhere. Transfer effectiveness indicates non-linear, threshold-dependent relationships with size, where behavioural objectives require fundamentally different approaches than income-based poverty reduction. Morocco achieved dramatic enrollment gains with transfers representing merely 5 per cent of household expenditure through strategic framing (Benhassine et al., Reference Benhassine, Devoto, Duflo, Dupas and Pouliquen2015), whereas Egypt’s poverty reduction demands 1520 per cent of income (Breisinger et al., Reference Breisinger, Passim, Kurds, Randriamamonjy and Thurlow2023). This non-linearity reveals a critical misconception: policymakers have assumed incremental increases produce proportional improvements when in fact behavioural change operates at low thresholds while poverty thresholds require substantially larger investments. The fiscal implications prove significant; governments may achieve greater impact through careful objective-setting and calibration than through increasing budgets alone.

When demand-side interventions undermine their own objectives

The findings exposes a fundamental design flaw often overlooked in cash transfer theory: demand-side incentives can produce perverse outcomes when supply constraints bind. For example, Morocco’s Tayssir programme shows that enrollment surged while test scores declined by 0.12–0.18 standard deviations due to classroom overcrowding and overwhelmed teacher capacity (Gazeaud and Ricard, Reference Gazeaud and Ricard2024). This counterintuitive result raises uncomfortable questions about whether programmes inadvertently harm populations by creating under-resourced service environments. The phenomenon likely extends beyond MENA to any context where service capacity remains fixed while demand expands. Egypt and Tunisia’s superior outcomes when combining cash with nutrition education and business training (El-Enbaby et al., Reference El-Enbaby, Gilligan, Karachiwalla, Kassim and Kurdi2019; Fitouri and Zouaoui, Reference Fitouri and Zouaoui2024; Leight and Mvukiyehe, Reference Leight and Mvukiyehe2025) demonstrate that the ‘cash plus’ model emerges not as optional enhancement but as necessary design principle. Cash transfers must be reconceptualised as components of integrated social protection systems rather than standalone interventions.

The structural limits of humanitarian cash assistance

The findings show structural barriers; legal restrictions, market failures, discrimination, as binding constraints rather than inadequate transfer amounts or durations. For example, the rapid fade-out of humanitarian cash impacts within —four to ten months exposes fundamental tensions between immediate relief and sustainable development (Chaaban et al., Reference Chaaban, Salti, Ghattas, Moussa, Irani, Jamaluddine and Al-Mokdad2020; Altındağ and O’Connell, Reference Altındağ and O’Connell2023). While humanitarian actors correctly prioritise acute needs, consumption support alone cannot generate pathways from poverty in displacement contexts. The persistence of education-focused programme effects relative to humanitarian assistance suggests investments targeting human capital and institutional relationships prove more durable than pure consumption support, even when initial transfer levels appear smaller. Yemen’s irregular payments nonetheless mitigated 42-43 per cent of conflict-related child malnutrition (Ecker et al., Reference Ecker, Al-Malk and Maystadt2024), indicating that even inconsistent transfers provide critical buffering in crisis contexts, yet this defensive function differs fundamentally from poverty graduation.

Cash transfers and the reproduction of gender inequality

The contradictory empowerment outcomes demonstrate that cash transfers simultaneously alleviate economic hardship and reinforce gender inequality. This paradox emerges because programme design often instrumentalises women as vehicles for child welfare rather than agents with independent interests. When transfers frame women primarily as mothers and caregivers, they strengthen patriarchal bargains by enhancing women’s value within traditional roles while constraining authority in non-caregiving domains. This mechanism explains why Egypt’s Takaful increased female labor force participation by relaxing credit constraints (El-Enbaby et al., Reference El-Enbaby, Gilligan, Karachiwalla, Kassim and Kurdi2019) yet decreased women’s healthcare decision-making power (El-Enbaby, Reference El-Enbaby, Hollingsworth, Maystadt and Singhal2024), the former relaxes economic constraints while the latter reinforces gendered responsibility divisions. Tunisia’s differential success through complementary training (Fitouri and Zouaoui, Reference Fitouri and Zouaoui2024; Leight and Mvukiyehe, Reference Leight and Mvukiyehe2025) suggests interventions must explicitly challenge gender norms rather than simply providing resources within existing power structures.

Global perspective

The findings from this study both converge with and diverge from cash transfer evidence documented in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. Education and health conditionalities effectively increase service utilisation when supply exists across regions, mirroring Mexico’s Oportunidades and Brazil’s Bolsa Família (Fiszbein and Schady, Reference Fiszbein and Schady2009). Poverty reduction consistently requires 15–20 per cent of income transfers (Handa et al., Reference Handa, Daidone, Peterman, Davis, Pereira, Palermo and Yablonski2018), women recipients prioritise children’s needs over male recipients (Adato and Bassett, Reference Adato and Bassett2009), and cash does not systematically reduce labor supply globally (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Hanna, Kreindler and Olken2017).

However, three MENA-specific patterns distinguish this region. Political economy dynamics reveal stronger linkages between cash transfers and state legitimacy than observed elsewhere. Egypt’s Takaful increased incumbent support (Breisinger et al., Reference Breisinger, ElDidi, El-Enbaby, Gilligan, Karachiwalla, Kassim, Kurdi and Thai2018) while Algeria’s corruption undermined effectiveness (Morsi, Reference Morsi2023), reflecting authoritarian regimes using welfare provision to build legitimacy amid limited democratic accountability. Conflict and displacement operate at scales rarely encountered elsewhere; Syrian refugees, Yemeni civil war households, and blockaded Palestinian populations face constraints fundamentally altering programme dynamics. Humanitarian impacts dissipate within —four to ten months in MENA (Chaaban et al., Reference Chaaban, Salti, Ghattas, Moussa, Irani, Jamaluddine and Al-Mokdad2020; Altındağ and O’Connell, Reference Altındağ and O’Connell2023), contrasting sharply with longer-lasting effects in non-conflict African contexts, suggesting violence and displacement create barriers cash alone cannot overcome. Additionally, energy subsidy reform contexts distinguish MENA from regions without extensive subsidy systems. Iran’s Targeted Subsidy Programme and Saudi Arabia’s Citizen Account Programme represent hybrid interventions combining subsidy rationalisation with social protection (Moerenhout, Reference Moerenhout2017), generating political economy dynamics absent in Latin America and most of sub-Saharan Africa.

Theoretical implications

The findings extend theoretical frameworks guiding cash transfer research in important ways. Economic models explain observed poverty reduction through relaxed budget constraints enabling optimal consumption choices, yet the non-linear dose-response relationship contradicts constant marginal utility assumptions, instead suggesting threshold effects consistent with behavioural poverty traps (Barrett, Carter and Little, Reference Barrett, Carter and Little2006). Below certain levels, households cannot escape subsistence constraints; above thresholds, marginal returns diminish. For example, Morocco’s labeling effects provide strong behavioural economics support. Framed but unconditional transfers generated enrollment gains (Benhassine et al., Reference Benhassine, Devoto, Duflo, Dupas and Pouliquen2015), demonstrating psychological mechanisms, not merely material incentives, drive behaviour change. This finding carries practical implications for low-cost programme design, suggesting strategic framing amplifies impact without increasing amounts.

Social protection programmes receives validation from integrated ‘cash plus’ models’ superior performance (Cluver et al., Reference Cluver, Orkin, Boyes and Sherr2014). These findings align with recent literature emphasising cash transfers function most effectively as systematic system components rather than standalone interventions (Handa et al., Reference Handa, Ibrahim and Palermo2023; Roelen et al., Reference Roelen, Devereux, Abdulai, Martorano, Palermo and Ragno2017). Supply-side constraint evidence reinforces this point: social protection effectiveness depends on functioning public services, a relationship often acknowledged theoretically but neglected in implementation (Devereux and White, Reference Devereux and White2010).

Gender theories find support in mixed empowerment findings. Tunisia’s agency enhancement through complementary training versus Egypt’s Takaful reinforcing traditional roles substantiates feminist arguments that economic resources constitute necessary but insufficient conditions for gender equity (Kabeer, Reference Kabeer1999). Empowerment requires addressing practical needs through income provision and strategic interests through challenging gender norms and power relations (Yeboah et al., Reference Yeboah, Arhin, Kumi and Owusu2015; Lwamba et al., Reference Lwamba, Shisler, Ridlehoover, Kupfer, Tshabalala, Nduku, Snilstveit and Stevenson2022).

Policy implications

Multiple interconnected implications emerge from this study, each addressing critical design and implementation challenges facing cash transfer programmes in the MENA region.

Transfer amounts must be calibrated to programme objectives rather than replicated across contexts, as the non-linear relationship between size and outcomes necessitates careful consideration of specific objectives, local economic conditions, and complementary investments. Small transfers effectively modify behaviour when strategically framed and supply-side capacity exists, whereas income-focused poverty reduction demands substantially larger transfers representing 15–30 per cent of household income. This calibration principle directly connects to the imperative that demand-side interventions require complementary supply-side investments to avoid counterproductive effects. Programmes targeting education or health services must therefore accompany transfers with investments in teacher training, classroom construction, pedagogical adaptation, and service quality improvements, ensuring that ministries coordinate closely to align demand-side incentives with supply-side capacity while recognising that enrollment and learning constitute distinct objectives requiring different responses.

Beyond domestic programming, humanitarian cash assistance must link to development programming and livelihood pathways, given that evidence consistently demonstrates humanitarian transfers improve consumption short-term yet impacts fade within —four to ten months with no lasting employment, asset, or self-reliance effects. Even generous transfers cannot substitute for sustainable livelihood pathways when refugees face legal employment restrictions, limited credit access, and discrimination, thus humanitarian actors and host governments must implement legal reforms enabling refugee employment, link assistance to skills training and job placement, establish graduation programmes combining transfers with productive assets and mentorship, and design multi-year programming providing sufficient time for building sustainable livelihoods. This humanitarian-development nexus connects importantly to gender considerations, as women’s empowerment requires complementary interventions addressing social norms, legal rights, and capacity building beyond cash provision. Transfers to women do not automatically produce empowerment and may reinforce patriarchal norms when framing women primarily as mothers and caregivers, thus programmes must integrate financial literacy and business skills training, legal empowerment interventions, social norm change programming engaging men and religious leaders, women’s collective action through savings groups and cooperatives, and childcare support enabling economic participation.

Targeting systems present particularly complex challenges, as they must balance efficiency, inclusion, and social cohesion while acknowledging no perfect solution exists. Proxy means testing improves efficiency yet risks exclusion errors and social tensions, categorical targeting ensures inclusion but proves fiscally expensive, and community-based targeting leverages local knowledge but faces elite capture risks. Governments must therefore recognise inherent trade-offs, invest in grievance and redress mechanisms, conduct regular targeting audits, consider hybrid approaches, and adopt inclusive programming in refugee contexts, while maintaining transparency regarding eligibility criteria and appeals mechanisms to ensure social acceptability. These targeting considerations connect fundamentally to implementation quality, which matters as much as programme design given that evidence documents how targeting errors, payment delays, disrespectful treatment, weak grievance mechanisms, and corruption undermine well-designed programmes. Governments and donors must consequently invest in digital payment systems ensuring inclusion through hybrid approaches, robust monitoring providing real-time data for adaptive management, strong grievance mechanisms enabling accountability, anti-corruption measures including transparency and regular audits, respectful assistance delivery recognising beneficiaries as rights-holders, and coordination mechanisms linking transfers to complementary services.

Methodological reflections

The findings from this study reveal methodological diversity that profoundly shapes understanding. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs provide strong causal evidence for short-term impacts yet face constraints including limited generalisability, high costs, ethical concerns, and context-specific features. Mixed-methods studies and qualitative research demonstrates mechanisms and lived experiences quantitative designs cannot capture, showing how family dynamics, social norms, and implementation realities shape impacts. Survey-based and descriptive studies document reach and coverage but cannot establish causality. Meta-analyses and economic modeling synthesise evidence across contexts yet face heterogeneity challenges and assumption dependencies. This methodological landscape indicates no single approach provides complete understanding. Causal rigor, contextual depth, and generalisability each involve trade-offs; triangulating evidence across methods strengthens confidence. Priorities include expanding rigorous evaluations in understudied contexts, conducting longitudinal studies capturing medium- and long-term outcomes, integrating qualitative insights to unpack mechanisms, and promoting transparency and open data to reduce bias. Methodological choices remain inseparable from what can be reliably concluded about programme impacts.

Limitations and future research directions

Multiple limitations necessarily temper conclusions drawn from this study. Research concentrates heavily in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Lebanon, leaving most countries including Iran, Libya, Somalia, Oman, Kuwait, Djibouti, and Bahrain substantially understudied.

Findings from well-studied contexts may not generalise to Gulf states with citizen-only welfare systems or conflict-affected regions with collapsed institutions. Methodological constraints further limit confidence in causal claims, as most studies rely on survey-based, qualitative, or descriptive methods with only few studies employing rigorous experimental or quasi-experimental designs. Evaluations rarely exceed three years, consequently leaving sustainability, long-term impacts, and dynamic effects poorly understood. Data quality and availability, particularly in conflict-affected contexts, further restrict reliable assessment while programme heterogeneity, encompassing differences in objectives, conditionality, targeting, transfer size, frequency, modalities, and complementary services, substantially complicates cross-programme comparisons. Implementation fidelity remains rarely measured despite its critical importance for interpreting outcomes. Political economy factors including governance quality, corruption, and authoritarian control fundamentally shape programme delivery yet remain underexamined in the existing literature. Most studies focus on average effects while paying limited attention to mechanisms and heterogeneous impacts essential for effective design, and publication bias alongside selective reporting further constrain what can be reliably concluded.

These limitations simultaneously highlight clear priorities for future research. High-quality impact evaluations in understudied contexts including Gulf states, Iran, and conflict-affected countries require urgent attention alongside longer-term follow-ups examining impacts five to ten years post-intervention to assess sustainability and intergenerational effects. Mechanisms explaining how cash transfers achieve outcomes, and heterogeneous effects across beneficiaries and contexts, demand rigorous investigation to inform programme targeting and design decisions. Economic modeling of general equilibrium effects encompassing price impacts, labor markets, and fiscal sustainability can guide macroeconomic planning, while implementation research on governance, corruption, and operational challenges proves essential for understanding bottlenecks constraining programme effectiveness. Studies examining graduation strategies linking humanitarian assistance to development programming can help prevent rapid benefit fade-out, whereas comparative analyses of conditional, unconditional, and labeled transfers in similar contexts will clarify which designs prove most effective under varying circumstances. Political economy research remains critical for assessing how governance quality and civic space shape programme outcomes and sustainability. Greater transparency including pre-registration of protocols, systematic reporting of null and negative findings, and open data sharing, will strengthen the credibility, replicability, and policy relevance of the evidence base, thereby enabling more informed decisions across the MENA region. These research priorities ultimately serve the broader objective of building evidence base that can guide effective social protection programming in one of the MENA region.

Conclusion

This study conducted systematic review of studies examining cash transfer programmes across the MENA region, addressing a critical knowledge gap in social protection research. While extensive evidence documents programme effectiveness in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, the MENA region has remained under-researched despite unique contexts characterised by ongoing conflicts, displaced populations, energy subsidy reforms, and diverse governance systems.

The findings demonstrates that cash transfers effectively reduce poverty, enhance food security, improve educational access, and support health outcomes when appropriately designed. However, findings challenge simplistic assumptions about programme effectiveness. Transfer size indicates non-linear relationships with outcomes, where behavioural objectives require fundamentally different approaches than income-based poverty reduction. Demand-side incentives can produce counterproductive effects when supply constraints bind. Humanitarian cash assistance provides temporary relief but limited sustainable pathways from poverty, with impacts dissipating within months. Cash transfers may simultaneously alleviate hardship while reinforcing gender inequality depending on programme framing and complementary interventions. Three MENA-specific patterns distinguish this region: stronger linkages between cash transfers and state legitimacy building among authoritarian regimes, conflict and displacement operating at unprecedented scales fundamentally altering programme dynamics, and energy subsidy reform processes creating hybrid interventions generating distinct political economy dynamics.

Policy implications demand integrated approaches. Transfer amounts must be calibrated to objectives rather than replicated across contexts. Demand-side interventions require complementary supply-side investments. Humanitarian assistance must link to development programming through legal reforms and skills training. Women’s empowerment requires interventions addressing social norms beyond cash provision. Implementation quality matters as much as design.

Future research must prioritise rigorous evaluations in understudied contexts, longer-term follow-ups, and investigation of mechanisms and political economy factors. As MENA countries navigate instability and crises, successfully harnessing cash transfer potential requires moving beyond simple provision toward integrated approaches embedding robust evaluation for continuous improvement.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746425101267

Funding statement

No funding to disclose.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.