[Latin America’s] crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable … It is only natural that they insist on measuring us with the yardstick that they use for themselves, forgetting that the ravages of life are not the same for all, and that the quest of our own identity is just as arduous and bloody for us as it was for them. The interpretation of our reality through patterns not our own, serves only to make us ever more unknown, ever less free, ever more solitary.

Drugs, violence, mafias, death squads, guerrilla armies, authoritarianism, corruption, crisis, death. These are the images conjured when I tell people about my research on labor regime dynamics in rural Colombia. Sensationalized in popular films and mass media, Colombian society is often likened to its most valued export, cocaine, its politics a dysfunctional banana republic, and its population poor and powerless victims. To many consumers of these media images, people living predominantly in core centers of global capitalism, these depictions of Colombian everyday life might appear chaotic and surreal in comparison to the routinized, orderly, and lawful realities of their own social and economic livelihoods. Indeed, the juxtaposition of stereotypes of violent oppression and chaos in Colombia, and Latin America more generally, to the democratic orderliness and stability of the countries in the global north, sparked the ire of Colombia’s Nobel prizewinner author, Gabriel García Márquez. In his Reference García Márquez1982 Nobel address, García Márquez lambasted the hypocrisy of such sensationalized depictions and made an impassioned plea to international observers to critically reexamine the capitalist West’s own arduous and bloody history and to analyze Latin American development using its own conceptual yardstick. This book is, in large part, an attempt to create such a yardstick.

Unfortunately, these sensational, albeit stereotypical, accounts of the violence and crisis of everyday life in Colombia are rooted in actual historical realities. Rural Colombians have experienced endemic low-intensity warfare from the country’s early experiences with laissez-faire liberalism at the turn to the twentieth century, through the years of state-directed developmentalism in the decades following World War II, and into the present era of twenty-first-century neoliberal globalization. During the nineteenth century, partisan conflict between Conservative and Liberal parties resulted in at least nine full-scale civil wars. These hostilities climaxed at the turn of the century with the deadly “Thousand Day War” (1899–1902), which led to nearly three decades of uneasy Conservative party domination marked by labor-repressive state measures meant to open the economy to foreign investment. Another wave of political violence resurfaced in the late 1940s following the assassination of populist Liberal candidate, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, on the streets of Bogotá in 1948. A period of violent urban unrest known as El Bogotazo spread to the countryside, where it morphed into a decade of intense rural partisan warfare known simply as La Violencia (1948–57) that pitted dissident Liberal and Communist insurgency groups against Conservative security forces and paramilitaries. This spiral of violence was initially constrained by a 1953 military coup headed by General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, an independent initially backed by Liberal and Conservative party leaders. But Pinilla’s incipient populism soon threatened the established class order, pressuring Colombia’s political elites to put their squabbles aside and join forces to oust Rojas Pinilla. In the wake of Pinilla’s ouster, they formed what became known as the National Front government (1958–74), a bipartisan power-sharing “gentleman’s agreement” that rotated executive positions between parties, suppressed antiestablishment political participation by outlawing third-party candidates, and instituted “state of siege” measures to quell social unrest. The authoritarianism of the National Front regime, combined with its promotion of disruptive state-directed industrial development measures, fanned the flames of Colombian political violence again as a number of Marxist and left-populist armed insurgency groups including the National Liberation Army (ELN), Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), Popular Liberation Army (EPL), and April 19th Movement (M-19) established bases of support among disaffected peasant communities, agricultural workers, urban proletarians, and radicalized students.

By the 1980s, hopes for a lasting solution to Colombia’s endemic violence arose once again with the election of Belisario Betancur (1982–86), a liberal reformer who entered into peace negotiations with guerrilla groups and instituted a series of political democratization measures that dismantled the National Front system. His successors, Virgilio Barco (1986–90) and César Gaviria (1991–94), continued the democratization process that culminated in the writing of a new, more inclusive constitution in 1991 and the demobilization of some guerrilla groups. Despite these efforts, Colombian society became embroiled in ever deeper and more complex forms of violence. Narco-trafficking mafia groups like the Medellín and Cali Cartels and heavily armed right wing paramilitary groups like the Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) engaged in terrorist actions that undermined peace negotiations and democratization efforts, while extant guerrilla groups bolstered their war-making activities through engagement in the illegal drug trade, extortion, and kidnapping for ransom. After a failed peace negotiation with the FARC (1998–99), the Colombian government revamped its militarization response through “Plan Colombia.” Ostensibly an institution-building initiative, the Plan became in essence a US-financed military effort that attacked guerrilla strongholds and facilitated the expansion of paramilitarism throughout the countryside. The election of hardline right wing President Álvaro Uribe (Reference Ferrer2002–10) escalated the militarization process by aligning the Colombian government’s efforts with US President Bush’s “War on Terror” initiatives, giving an implicit greenlight to paramilitaries to terrorize inhabitants of guerrilla strongholds and anyone else presumed to be complicit with them. By 2006, the balance of power shifted so far to the right that the Uribe government was able to oversee the demobilization and social reintegration of the AUC with impunity, offering little in the way of compensation to their victims. Soon thereafter, with guerrilla forces radically diminished, Uribe’s predecessor, Juan Manuel Santos (2010–18) implemented peace talks with the country’s largest group, the FARC, and began negotiations with the ELN. Despite the demobilization of armed groups on the right and left, incidents of rural violence continue into the present, as new, smaller paramilitary groups, drug trafficking cartels (cartelitos), and active splinter guerrilla factions now jockey for control of rural territories, resources, and populations.

The impact of this endemic violence in Colombia’s countryside bears out in the numbers. According to Human Rights Watch’s World Report 2019 (2019:151), violence associated with Colombia’s armed conflict has led to the forced displacement of 8.1 million people since 1985, a shocking number of people in a country of just over 49 million in total.Footnote 1 Worse still, over 200,000 more rural residents have been displaced amid ongoing armed conflict since the signing of the Santos peace agreement in 2016, as new armed actors have struggled to fill the “power vacuum” left from the disarmament of the FARC. Predictably, this massive exodus from the countryside has itself compounded systemic problems of over-urbanization, crime, unemployment, and rural poverty. With guerrilla groups like the FARC pushed aside, Colombia has experienced an unprecedented wave of “narco land grabs” driven in large part by elaborate and often illegal land-laundering schemes developed by Colombian elites that have concentrated a shocking 81% of the country’s total productive land into the hands of 1% of the population.Footnote 2 And while rural Colombians have borne the brunt of this political violence, the primary targets of directed acts of repression and terror are leftist social activists, including community organizers, human rights workers, journalists, and especially labor leaders and union members. The International Trade Union Confederation’s Global Rights Index reports (2016, Reference Baglioni2018) find Colombia to be “the country with the highest number of [trade unionist] murders of any country. Over 2,500 unionists have been murdered in the past 20 years, more than in the rest of the world combined.”

Colombia’s protracted and seemingly exceptional tendency for social and political violence has spawned a vast body of scholarly literature that has focused on local conditions that have given rise to armed insurgency groups, drug trafficking mafias, and social unrest. Indeed, much ink has been spilt explaining Colombia’s troublesome and endemic history of social and political violence over the past half century. In fact, there is even an informal group of Colombian scholars known as violentólogos, or specialists in the study of Colombian violence.Footnote 3

This focus on violence, however, often overshadows a different, and in comparison paradoxical, side of Colombian social and political history. Most striking here is the fact that Colombia remains Latin America’s most long-standing and stable electoral democracy. The country has held regular competitive elections with peaceful transfers of power consistently since the last century with few exceptions.Footnote 4 Of course, party politics in Colombia remains the exclusive affair of elites, corruption continues to permeate the country’s political institutions, and voter turnout remains low.Footnote 5 Yet, much to the chagrin of the Colombian left, it is also true that the traditional parties and their recent offshoots continue to retain the loyalty of the vast majority of the country’s voters.Footnote 6 Indeed, the hegemony of Colombia’s traditional political establishment runs surprisingly deep. Explaining the country’s political conservatism, Charles Bergquist (Reference Bergquist, Bergquist, Peñaranda and Sánchez2001:203) argued that the leftist politics espoused by Colombia’s guerrilla groups “[have] had limited appeal for the vast majority of the people. Throughout the twentieth century, in fact, Colombia has had the weakest left of all the major Latin American countries.” And while most of Latin America shifted leftward during the years of the “pink tide” in the early twenty-first century, the Colombian government locked step with the United States and became a stalwart of neoliberal policy initiatives pushed by global multilateral agencies.Footnote 7 It is this enduring political conservatism that twice elected hardliner Álvaro Uribe (Reference Ferrer2002–10), then his former Minister of Defense and hand-picked successor, Juan Manual Santos (2010), and most recently another Uribe successor, Iván Duque Márquez (2018–22), to the presidency.

The country’s historically vibrant national economy and stable economic growth also contrast sharply with its endemic violence. In comparison to the development histories of other Latin American countries, wherein capitalist transformation triggered powerful anticapitalist movements that led to experiments in populism, economic nationalism, and socialism, Colombian politicians and economic policymakers have been described as predominantly “risk-averse” and “pragmatic technocrats,” shielded from mass politics by the hegemony of the traditional political establishment.Footnote 8 Moreover, this pragmatic economic liberalism actually delivered on its promise of sustained economic growth over the course of the 20th century, making Colombia a developmental lodestar showcased by the United States and the global multilateral agencies as a progressive alternative to economic nationalism and communism. For example, in 1949 Colombia became the first site of the World Bank’s new “economic missions” meant to extend Franklin Roosevelt’s “Fair Deal” developmental vision to the Third World. New Deal economist, Lauchlin Currie, headed the mission and came to view Colombia as a beacon of “accelerated economic development.”Footnote 9 Three years later, eminent economist Albert Hirschman also moved to Bogotá, becoming a founding member of Colombia’s new National Planning Board and an economic counselor to Colombian President, Carlos Lleras Restrepo, to whom he later dedicated his classic Journeys toward Progress: Studies of Economy Policy-Making in Latin America (Reference Hirschman1963).Footnote 10 Both Currie and Hirschman saw in Colombia’s exceptional growth a universal template of national development and modernization for the Third World. In the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution, when guerrilla insurgencies were spreading across the countryside of Latin America, Africa, and Asia, Colombia became a key testing ground of the Kennedy Administration’s “Alliance for Progress” and the World Bank’s rural development initiatives, both designed to thwart rural radicalism by bolstering economic productivity and social stability in the countryside. In the 1970s, the vibrancy of Colombia’s economy granted its policymakers the privilege of sidestepping the debt incurred by many developing countries to finance large-scale development projects and promote domestic industrialization. Combined with the influx of capital from illegal drug trafficking in the 1980s, this allowed Colombia to essentially elude the crushing debt crisis of the 1980s and therefore sidestep the imposition of virulent structural-adjustment loans and austerity measures advocated by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank in the 1990s.Footnote 11

To be clear, contemporary scholars have challenged “the developmentalist illusion” linking economic growth and industrialization to social welfare in the global south, showing it to be only loosely correlated at best and antithetical at worst.Footnote 12 In Colombia, economic growth brought with it fabulous wealth for a small segment of the population and some of the worst levels of economic inequality in the region. A 2018 World Bank report on economic mobility in Latin American middle class, for example, describes Colombian inequality as “stubbornly high,” with 10% of income earners garnering 40% of the country’s wealth and its Gini co-efficient (50.8) the second worst in Latin America (only Brazil scored higher).Footnote 13 Rural Colombians have been particularly affected by this inequality, as Colombia ranks highest in Latin America for its extreme concentration of land ownership and sizable population of precarious rural migrants.Footnote 14 This said, Colombia’s economic growth has also produced a sizable and durable middle economic strata that stands out in the region.Footnote 15 And this middle class is not only urban. Colombia’s countryside has also been the home of one of Latin America’s few “middle class peasant” populations – coffee-producing, or cafetero, farmers – who have been largely impervious to the revolutionary politics of Marxist guerrilla insurgency groups, the pull of the illegal narcotics economy, and the social and political violence that has taken root in other rural regions of the country.

How can we explain the coexistence of these complex and contradictory dynamics of Colombian development? Why has capitalist development in Colombia produced both bastions of support for an entrenched class of elites and endemic social crises and violence? And what does an analysis of development in Colombia teach us about the broader prospects for social well-being and stability for those living at the margins of the world market?

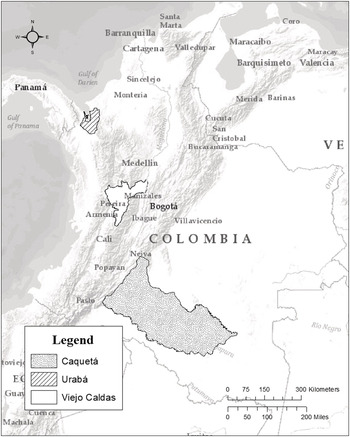

This book answers these questions through a comparative and world historical analysis of the labor regime dynamics of rural Colombia’s most important global commodity-producing regions: the coffee region of Viejo Caldas, the banana region of Urabá, and the coca (base ingredient of cocaine) region of the Caguán. Analyzing development trajectories through the lens of labor regimes is uncommon. Indeed, since its origins in the 1940s and 1950s when development economists likened national economic growth and industrialization with the high mass consumption culture associated with North American and European livelihoods, the concept of national development has undergone significant definitional reiterations and major conceptual unlearning. In this book, I use the term “development” in its most generic formulation as the set of policy initiatives and practices implemented by states to promote economic growth through the production of commodities for the global market. Such initiatives are “capitalist” because the production of these commodities becomes ensconced in a market logic that gives priority to the ceaseless accumulation of capital above all else. Analyzing development from the perspective of labor regimes analysis thus reorients the discussion away from abstract thinking about the relationship between economic growth and social welfare toward concrete analysis of the social contradictions, unintended social consequences, and labor control strategies that arise when developmental processes seek to transform marginalized regions into sites of capitalist growth and production.

Focusing on the labor and development dynamics of Colombia’s coffee, banana, and coca regimes is especially useful because each of these commodities has played a central role linking rural land, labor, and capital to the world market while also expressing the broad diversity of development dynamics that have taken root in the country.Footnote 16 In different ways and to varying degrees, coffee, banana, and coca production have both absorbed rural labor and expelled it through violent processes of rural land dispossession. They have generated foreign exchange, regional economic growth and development as well as highly exploitative and dangerous working conditions, underdevelopment, labor repression, and economic marginalization.Footnote 17 They have expanded the territorial presence of the state to frontier regions of the country, producing both bulwarks of conservative electoral support and state legitimacy as well as radical political opposition that has challenged the interests of capital and brought the state to the brink of collapse.

Taken collectively, the dynamics of these three commodities paint a picture of Colombia’s highly varied and contentious development trajectory from the country’s early experiences with laissez-faire liberalism at the turn of the twentieth century, through the years of state-directed developmentalism in the decades following World War II, and into the present era of twenty-first-century neoliberal globalization. Coffee and bananas, for instance, were the main commodities (along with oil) that first propelled Colombia’s insertion into the world economy. As such, they helped transform the largely stagnant and “inward-looking” economy inherited from the era of Spanish colonialism in the nineteenth century into a liberal growth economy by the early decades of the twentieth century. Both generated the foreign investment and foreign exchange needed to finance the developmental goals of rapid industrialization, urbanization, and “high mass consumption” that had become Colombia’s national growth model throughout the postwar decades. Yet, they differed significantly in terms of their ability to generate local social and economic stability.

Colombia’s coffee sector was bolstered by what has been called the “Pacto cafetero,” a developmentalist social compact instituted by the parastatal National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia (Fedecafé) that regulated the domestic coffee market and generated what I describe as a hegemonic labor regime characterized by the active participation of cafetero farmers in the expansion of the sector. Under this social compact, Colombia’s coffee farms transformed into highly rationalized “factories in the fields” while its producers transformed from coffee-producing campesino peasants into market-dependent cafetero farmers. And while Colombia continues to churn out some of the world’s most highly valued mild Arabica coffee beans, the economic and social viability of the Pacto cafetero has been crushed by the weight of macro-structural transformations in the world coffee economy. Since the early 1990s, Colombia’s coffee regime has erupted in waves of cafetero militancy that have thrown Fedecafé’s hegemonic control into deep crisis. The continued vibrancy of the coffee sector has become, in many ways, a gauge of Colombia’s ability to continue its developmental successes of the past into an uncertain future of twenty-first-century global market turbulence.

Bananas, in contrast, have a more controversial significance in Colombia’s developmental history. Banana production first arose as an export enclave in the Santa Marta region of Colombia’s Caribbean coast, where it remained under the dominion of the US-based United Fruit Company (UFC). When banana workers organized a strike for better wages and working conditions in 1928, Colombian military forces were called in, leading to a massacre that tarnished the reputation of the UFC and led to the company’s divestment from the region over the ensuing years. In the early 1960s, banana production arose once again, this time through the establishment of domestically owned plantations and exporting firms located in the coastal region of Urabá. Unlike coffee, which incorporated land-owning cafetero farmers into a hegemonic social compact, the banana regime of Urabá developed through the dispossession of local populations from the land and the full-proletarianization of their labor, leading to the consolidation of a wage-dependent and polarized class structure in the region. This modality of commodity production – proletarianized workers in state-backed agro-export centers – became the developmental model promoted by the Colombian state during the postwar decades and a barometer of its economic success. But rather than facilitate local development, Urabá quickly deteriorated into a despotic labor regime marked by state and (later) paramilitary violence used to quell labor militancy and avert redistributive demands that threatened the continued economic vibrancy of the sector. While Colombia’s banana plantation owner association (Asociación de Bananeros de Colombia, Augura) was able to rely upon labor repression to contain worker militancy during Urabá’s early decades of production, this strategy itself unraveled in the 1980s and into the 1990s when the region experienced its own deep crisis of labor control.

The cocaine industry is the latest iteration of rural commodity production and development in Colombia, one that is best contextualized historically within the present era of neoliberal globalization. Emerging in the 1980s when the postwar developmental model was becoming exhausted, and consolidating in the 1990s when the Colombian state began to adopt neoliberal policies meant to dismantle its erstwhile developmental institutions, coca and the cocaine economy arose as one of the few commodities capable of absorbing rural surplus labor and providing a relatively stable livelihood for landless migrants. The Caguán region emerged as a key site of coca production in the 1980s, only after its rural inhabitants experienced decades of despotism driven by local landed elites and large-scale cattle ranchers. The region’s transformation into a coca-producing regime occurred through the actions of the revolutionary FARC guerrillas, who instituted their own protective social compact that regulated the domestic coca market, protected coca farmers from land dispossession, and generated what I describe as a counter-hegemonic labor regime. By the turn of the twenty-first century, however, FARC counter-hegemony ran up against the US’ “War on Drugs” and “War on Terror” initiatives, eventually forcing the FARC to give up its territorial control of the region under the 2016 peace negotiations.

Analyzing these diverse experiences of capitalist development that have arisen across Colombia’s coffee, banana, and coca regimes raises two sets of questions that guide this book. First, why do we see such starkly differently local labor regimes in rural Colombia at the same period in time, that is, during the postwar developmental decades? Why did hegemony prevail in the coffee regime and despotism in the banana and cattle-turned-coca regimes? And second, why did these stable, albeit contrasting, labor regimes of the postwar developmental decades converge toward crises of labor control and counter-hegemonic social formations in the 1980s and 1990s?

Conceptual Approach: Labor Regimes, Commodity Chains, and World Hegemonies

To explain the diverse experiences of global commodity production across rural Colombia, I extend insights from three bodies of scholarly literature: labor regimes analysis, global commodity chains, and world historical sociology.

Extending Insights from Labor Regimes

Scholarship on labor regimes arose in the 1970s and 1980s to analyze the social contradictions and production politics that arise from capitalist labor processes. At the core of labor regime scholarship is what might be described as Antonio Gramsci‘s questions, that is, under what conditions do workers and commodity producers acquiesce to capitalist labor processes and consent to the logic of market imperatives and under what conditions must labor control be obtained through overt expressions of coercion and labor repression? Over the past decades, labor regime scholars have traversed the globe, engaging in rich ethnographic and historical analyses of the varied strategies of labor control deployed by capital and states across distinct industries and national contexts.Footnote 18 In their efforts to analyze the diverse ways that local labor regimes have adapted to the structures of global capitalism, contemporary labor regimes scholars have provided important insights into the ways that contemporary processes of economic globalization have generated new forms of capitalist labor control that are highly coercive in form but that have not relied explicitly upon direct expressions of the types of state and capitalist violence that characterized the early despotic labor regimes described by Karl Marx and other early critics of capitalist labor processes. Market despotism, they argue, is the emergent form of labor control in a globalized economy that promotes capital mobility and flexible production systems, while forcing local workers to accept increasingly precarious working conditions or lose their jobs.

Indeed, the core focus of this book analyzes the ways that Colombian workers have been harnessed by capital and state agencies to meet the demands of global markets and the social struggles that this process has engendered. However, it also challenges some of the core assumptions of labor regime scholarship regarding the link between contemporary processes of globalization and market despotism. And instead, it develops a novel, more nuanced conceptual framework that is sensitive to the specific sets of social contradictions and labor control dynamics that arise in highly marginalized spaces of world capitalism. It does this in two ways. First, I reconceptualize labor regimes as hegemonic class projects in which ongoing and profitable processes of global commodity production and labor control are a social accomplishment rather assumed a priori. Far from institutions of capitalist class domination, labor regimes are constituted by efforts, actions, and strategies created and acted upon by specific groups of capital and state agencies and actively contested by local workers, families, and communities. As this book demonstrates, in the remote regions of rural Colombia that produce coffee, bananas, and coca, labor is not always effectively controlled, market institutions are highly unstable, and capitalist development is a risky enterprise and rare achievement rather than an immutable feature of progress and modernity. Efforts to harness labor to meet the demands of commodity production for the world market can just as readily swing between consensual and coercive mechanisms of labor control to endemic crises of labor control and even the establishment of counter-hegemonic regimes that exist outside of the dominion of capital and state. Broadening the labor regime framework beyond the consent–coercion dichotomy to include the endemic crises, frequent use of extra-market violence, and the breakdown of capitalist production altogether are thus essential to an understanding of capitalism in rural Colombia and other marginalized regions of the world economy.

Second, I demonstrate how capitalist firms and state agencies that operate at the margins of the global market – that is, where the very institutions of the market are perennially challenged, subverted, and reconstructed – are tasked with a broader set of social and economic imperatives than their counterparts in advanced centers of world capitalism. As a consequence, they must adopt a broader range of institutional and extra-institutional strategies to control labor and stabilize market transactions. While the interventions of their capitalist counterparts in core centers of the world economy typically engage in market-regulatory efforts in order to mediate class conflicts and cultivate worker acquiescence, the capitalist firms and state agencies driving the establishment of labor regimes in rural Colombia are often “developmental organizations” that must create the structural and institutional conditions of the market itself. As we shall see, state developmentalist interventions in rural Colombia have played a critical role in the clearing of forests, the migration of workers through state-backed settlement and land colonization practices, the establishment of land titles and property rights institutions, and the construction of transport and other vital infrastructure to connect production sites to global markets. Importantly, however, these interventions do not merely extend the market to new geographies and new commodity frontiers. In rural Colombia, state development interventions must also actively engage in practices meant to create and reproduce pools of landless and market-dependent working-class populations, or what might simply be described as proletarianized working-class formations.

Moreover, the developmental strategies, institutional practices, and organizations deployed to reproduce market-dependent livelihoods have varied significantly. Some regimes have relied heavily on the use of state and paramilitary violence to dispossess rural inhabitants from the land and repress labor unrest and militancy. Others have created hegemonic discourses and institutional rationales that connect systems of commodity production to ideological constructs intended to imbue greater meaning and legitimacy to what would otherwise be viewed as mere commodity production, raw profit, or simply a job. As this book points out, far from structures of the global market generating the labor control required for global commodity production across rural Colombia, developmentalist state, parastatal, and indeed quasi-state organizations have played a critical role.

The organizations that I study – the National Federation of Coffee Growers (Fedecafé), the Association of Banana Growers (Augura), the National Federation of Cattle Ranchers (Fedegán), and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) – vary radically in terms of their organizational origins and imperatives. They are therefore unlikely comparative units. Fedecafé, Augura, and Fedegán are all Colombian industrial trade associations, or interest groups, that were created to lobby the state and advocate for the commercial expansion of their respective sectors. However, Fedecafé also developed into a parastatal organization that was granted state-like authority to tax coffee exports, regulate domestic market transactions, and institute developmental projects related to the coffee sector. The FARC, in turn, is a revolutionary Marxist insurgency group that has taken on state-like functions in the areas under its territorial control, including the taxation and regulation of the coca sector. Despite these differences, I demonstrate that each organization has struggled with the same structural problem of how to harness local land, labor, and livelihoods to meet the demands of commodity production for the global market and in doing so, they have developed surprisingly comparable, albeit distinct, hegemonic projects with varied labor regime outcomes.

Extending Insights from Global Chain Studies

Like most labor regimes analyses, this book explores the complex social dynamics and historical processes that have made the production of global commodities across rural Colombia possible. However, unique to this book is an equally compelling analysis of the global markets in coffee, bananas, and cocaine and an elaboration of how the local labor regime dynamics of each is shaped by, and indeed shapes, the global markets in which they are embedded.

To understand this connection between global markets and local labor dynamics, I draw from and extend insights from the scholarly literature on what sociologist Jennifer Bair (Reference Bair2009:1) has aptly described as “the field of global chain studies.” Since its early origins in world-systems analysis, scholars have used the commodity chain metaphor to map out and analyze the networks of labor and production processes that transform natures, raw materials, and human labor into finished products sold in capitalist markets. World-systems scholars like Immanuel Wallerstein and Terence Hopkins developed the commodity chain construct as a heuristic tool to demonstrate how systems of commodity production have historically cut across national territorial boundaries and, through processes of unequal exchange, reproduced core–periphery spatial inequalities in the world economy.Footnote 19 Since this early formulation, the chain metaphor has undergone significant reformulations as new bodies of scholarship have further unpacked the social and institutional workings of global industries and reappropriated its heuristic power to analyze a broad range of world market dynamics. Indeed, recent iterations in the literatures on global commodity chains (GCC) and global value chains (GVC) have developed a robust conceptual toolkit to analyze how global industries and markets differ significantly in terms of their governance structures, institutional norms and practices, and the opportunities for economic and social upgrading they provide to local populations, firms, and governments across the world economy.Footnote 20

This book draws from two tools in the commodity chain toolkit. First, it revisits the early world-systems emphasis on commodity chains as mechanisms that reproduce global inequalities by analyzing how local labor and development dynamics in rural Colombia are impacted by the relative profitability of their nodal location within the sequence of production processes that transform raw materials and human labor into value-added finished products. Following the work of Giovanni Arrighi and Jessica Drangel (Reference Arrighi and Drangel1986), it distinguishes the core–periphery nodal location of Colombia’s coffee, banana, and coca regimes by their access to the unequal distribution of wealth produced along each commodity chain. Core locations are those that occupy the most profitable niches, with “core-like wealth” accruing to firms that are able to externalize competition in the market down the chain to peripheral actors. Peripheral positions, in contrast, are characterized by greater market competition and therefore less access to the overall wealth generated by the totality of production processes that constitute the chain.

As we shall see, accessing the wealth associated with core positions in the commodity chain does not only open opportunities for local economic growth and development. It also makes available additional resources that can be used to generate and finance new, albeit costly, hegemonic labor systems. As highly competitive market niches marked by lower profits and greater economic instability, peripheral positions narrow the range of strategies that can be used to effectively contain labor, thereby increasing the propensity for despotism and crises of labor control. Situating Colombia’s coffee, banana, and coca regimes spatially within the core–periphery structures of their respective commodity chains therefore provides crucial insights into the opportunities and obstacles that each market presents to local regime actors, with some providing local regime actors in Colombia access to core-like profits and others remaining stubbornly structured by deep core–periphery divisions that throw up significant barriers to local growth, development, and worker well-being.

If the first insight from the field of global chain studies comes from this book’s use of core–periphery nodal locations to identify the structural obstacles experienced by local regime actors, the second insight comes from an analysis of the actions deployed by local regime actors that challenge these core–periphery structures. As Gary Gereffi (Reference Gereffi2018) points out, global industries are composed of distinct governance structures, institutional practices, and market norms that have important bearing on the capacity of local firms and states to “upgrade” to more profitable market niches along the chain. Put simply, core-peripheral nodal locations are not overdetermined by the uneven spatial geography of world capitalism. Rather, they are dynamic locations that vary over time within any given commodity chain and that vary starkly across distinct global markets.Footnote 21 Indeed, the institutional mechanisms and practices that reproduce core-peripheral positions are themselves key sites of contestation within any given market or global industry, the outcome of which has important ramifications for a regime’s prospects for upgrading to more profitable market niches.

This book contributes to our understanding of industrial upgrading in two ways. First, it draws attention to how processes of upgrading do not only result from the actions of firms or industry groups that move into new product lines, transform production processes, increase skills, or shift investments to new industries.Footnote 22 Instead, upgrading processes can arise through changes in the geopolitical and institutional contexts of a chain itself, which can open opportunities to access core-like profits without substantially changing existing labor processes or production strategies. Second, it clarifies the social implications of upgrading processes by drawing attention to how processes of upgrading, and indeed downgrading, impact the range of strategies available for local labor control. In this sense, we are better able to identify the sociological mechanisms that link processes of economic upgrading, or the shift to higher-value-added activities, to the “social upgrading” that is associated with improvements in the rights and entitlements of workers and to favorable local development outcomes.Footnote 23

As we shall see, the hegemony of Colombia’s coffee regime of Viejo Caldas was premised upon developmental and parastatal strategies that upgraded the regime’s location in the world coffee market from a peripheral niche to a core-like niche. It was access to core-like wealth that permitted Colombia’s parastatal coffee organization, Fedecafé, the means to institute a protective social compact that proved essential to the construction of hegemony on the ground in Viejo Caldas. Likewise, albeit by vastly different means, the FARC’s ability to generate a counter-hegemonic labor regime in the Caguán region of Colombia has been premised upon its capacity to access core-like wealth through the illegal cocaine market. Despite the vast differences in the global market dynamics of coffee and cocaine, local regime actors in rural Colombia were able to take advantage of the opportunities to upgrade in each respective market to access core-like wealth, and this upgrading process has been critical to their ability to control labor locally. The establishment of hegemonic and counter-hegemonic regimes in Caldas and the Caguán stand in stark contrast to the despotism of Colombia’s banana regime, which has been anchored firmly within the most peripheral niche of the international banana market. Unable to upgrade to avoid the hyper-competitiveness of the banana market, Colombia’s banana-producer association, Augura, has been forced to rely upon more repressive measures to contain labor unrest and avert redistributive demands from below.

Extending Insights from World Historical Sociology

Situating Colombia’s rural labor regimes within the core-peripheral dynamics of their respective commodity markets provides a more nuanced and useful understanding of how the spatiality of regimes within their respective markets provides local regime actors with the resources needed to control labor through consensual rather than coercive means. Yet, one should be cautious about developing unidirectional explanations of the impact of global market structures on local labor regime outcomes. Indeed, as this book demonstrates, the strategies of labor control deployed break down over time, giving way to deep crises of labor control and even to the establishment of alternative social formations that operate outside of the effective control of the state. The global markets in coffee, bananas, and cocaine themselves have been subjected to systemic bouts of labor militancy and geopolitical contestation that have seriously threatened the continued profitability of core market actors and forced significant restructuring of the markets themselves. And as we shall see, these periods of systemic upheaval have transformed the core–periphery structures of global markets in ways that have opened opportunities to upgrade and thereby avert the social and economic ramifications of peripheralization.

To understand the geopolitical contestation and historical dynamism of global markets, I situate Colombia’s labor regimes temporally within the arc of rising and falling world hegemonies. Following the work of Giovanni Arrighi (Reference Arrighi1994, Reference Abbott2009; Arrighi and Silver Reference Arrighi and Silver1999), I argue that periods of world hegemony arise through the systemic reorganization of the institutions of world capitalism and the emulation of the dominant state by other states, both of which foster the stabilization of the world market and the systemic expansion of world production and trade. World hegemonic unraveling occurs when interstate rivalries and inter-capitalist competition intensify in ways that challenge rather than bolster the geopolitical power of the world hegemon. As capital accumulation shifts from production and trade to finance, the global governance institutions deployed by world hegemons unravel, system-wide social conflicts arise, and are eventually abandoned altogether, giving rise to periods of world-systemic chaos. These world hegemonic transitions occurred at various periods of global capitalism, including through the rise of Dutch hegemony in the seventeenth century, British hegemony in the nineteenth century, and US hegemony in the twentieth century.

In this book, I demonstrate how the emergence of local labor regimes in rural Colombia have been shaped by, and indeed shaped, the historic rise and contemporary decline of US world hegemony. Situating Colombia’s labor regimes world historically is useful for three reasons. First, it illuminates the economic and political impetus driving the production of global commodities in rural Colombia and the adoption of various upgrading strategies. As we shall see, US efforts to stabilize and expand the workings of the global market through governance institutions and foreign aid gave credence to the idea, shared by Colombian state and parastatal agencies, that global commodity production for export could become a viable strategy of development and economic growth.

Second, the fact that Colombia’s developmentalist ventures indeed produced results on the ground further intensified the state’s efforts to maintain its developmental efforts even when these efforts generated deep social contradictions and crises rather than sustained growth and development. By situating Colombia’s labor regimes world historically within the arc of US world hegemony, we see that the violence and despotism of Colombia’s labor regimes has not only been rooted in the efforts of capitalist firms and agencies to adapt to competitive and peripheral niches of global markets. Rather, the pervasive use of violence and terror to contain labor unrest and instill capitalist control of the labor process has been deeply implicated in the developmentalist logic of the Colombia state, which has prioritized economic growth above the interests of rural workers and commodity-producing farmers.

Third, situating Colombia’s labor regimes temporally within the arc of rising and falling world hegemonies draws attention to the critical role of US hegemonic institutions themselves in facilitating local efforts to contain, repress, and mediate the social contradictions of the country’s labor regimes. Like other studies of US imperial interventions in Colombia, this focus on US world hegemony draws attention to the ways that US foreign policy, development aid, and militarization strategies have propped up the power of domestic elites, promoted capitalist expansion into the countryside, and contained popular struggles that have arisen to democratize the country’s political and economic institutions. Unique to the world hegemonies perspective, however, is its attention to the fragility, variability, and unintended consequences of these efforts to control, stabilize, and expand the workings of capitalism into marginalized regions of the world economy. During the heyday of US hegemony in the postwar decades, US hegemonic actions were critical factors influencing the Colombian government’s efforts to ensure social stability in the countryside through market-based forms of development. In Viejo Caldas and Urabá, US hegemony manifests in its support of the geopolitical restructuring of the international coffee and banana markets that were designed to open opportunities for local growth and development. In the Caguán, the United States helped finance rural development initiatives that were critical to the frontier colonization of the region. By the 1980s and 1990s, each of these interventions backfired and the United States responded by abandoning its support of local development in favor of neoliberal policies backed by military interventions under the aegis of the US wars on drugs and terror. As we shall see, the most significant impact of the unraveling of US world hegemony on Colombia’s rural labor regimes has been a general shift, not from hegemony to despotism but from hegemony and despotism to deep crises of control across each region.

Overall, conjoining the insights of labor regimes, global commodity chains, and world historical sociology draws attention to a critical, albeit overlooked, factor that has been especially destabilizing of Colombia’s rural labor regimes: the socially toxic convergence of local processes of full-proletarianization with global processes of market peripheralization. I describe the convergence of these two processes within a given labor regime as peripheral proletarianization. Whereas market peripheralization indeed restricts the options made available to capital and state agencies in their efforts to harness labor to the whims of the world market, the social contradictions of proletarianization alone can be partly ameliorated when workers and farmers retain access to nonmarket strategies of economic survival. When these nonmarket-based avenues are closed off and livelihoods are made dependent upon the vicissitudes of the world market, the mechanisms of labor control tilt toward despotism and crisis. Understanding the forces driving peripheral proletarianization and the consequences of it on local labor regimes, I argue, provides valuable insights into the contradictory impulses of Colombian national development during the heyday of US world hegemony in the mid-twentieth century and the increasing precarity of social and economic life in rural Colombia as US hegemony has unraveled.

Methodological Approach: Comparative and World Historical

The questions at the center of this book ask why we see such stark variation across Colombia’s rural labor regimes during the heyday of US world hegemony in the postwar developmental decades and why these distinct, albeit varied, labor regimes broke down into crises of labor control in the 1980s and 1990s as US world hegemony unraveled. Given the nature of these questions, the methodological approach used is comparative and historical. As a variation-finding strategy, the comparative methodological approach is uniquely situated to understand both the vast differences and common patterns that have arisen across Colombia’s rural labor regimes and the markets for their respective commodities.

As the primary object of analysis, much of the empirical focus of this book utilizes the comparative-historical case method to understand the varied and complex ways that rural frontier regions in Colombia were transformed into sites of global commodity production and the varied strategies of labor control that were deployed to make these systems of commodity production viable. Given the historical timing of the formation of each labor regime, the comparative method offers novel insights into how each labor regime was affected by the developmental opportunities and strategies that have arisen across three distinct periods of time: the period of laissez-faire liberalism from the late nineteenth century to the period of the Great Depression in the 1930s, the heyday period of developmentalism ushered in through the rise of US world hegemony in the postwar decades, and the rise of neoliberal globalization that has been associated with the unraveling of US world hegemony since the 1980s.

My use of the comparative-historical method is not limited to an analysis of labor regime dynamics on the ground in rural Colombia. Importantly, I also use it to analyze continuities and differences in the global commodity chain dynamics for coffee, bananas, and coca, thus pointing out the varied ways that the core–periphery structures and governance institutions of each commodity market have provided opportunities and obstacles to labor regime actors in each region. Using the comparative-historical method in this double way offers insights into both the significant historical ruptures and surprising historical continuities that have arisen across each labor regime and global market over time. Understanding these spatial and temporal dynamics provides a robust set of comparisons of nine comparative units: three rural labor regimes (coffee, bananas, and coca) across three periods of world historical time (laissez-faire liberalism from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1930s, developmentalism from the close of World War II until the 1970s, and neoliberalism from 1980s until the present). Understanding the continuities and differences that have arisen across these comparable units forms the backbone of the empirical analysis of this book.

However, I also draw from the methodological insights of world historical sociology to add an additional layer of complexity to the analysis. As world historical sociologists point out, one should be skeptical of the comparativist notion that individual cases can be analyzed as self-contained units.Footnote 24 As we shall see, the dynamics of Colombia’s labor regimes are not simply produced by the actions of local actors, be they capitalist firms, state agencies and institutions, or local populations. Nor are they unidirectionally shaped by outside forces that act upon these actors, whether these forces emanate from national state offices in Bogotá, the boardrooms of transnational corporations, or the halls of the US Pentagon, Capitol Hill, and the White House. As this book highlights, the regime dynamics of each is impacted directly and indirectly by the dynamics of the other regimes.

Analyzing interregional dynamics provides insights into the complex ways that Colombia’s coffee, bananas, and coca labor regimes have direct and indirect bearing on one another. As we shall see, the early successes of Colombia’s coffee regime in generating regional growth and social stability provided Colombian policymakers with a model that guided national development endeavors and promoted the marketization of other rural export zones of the country, including the banana region of Urabá and what became the coca region of Caquetá. And importantly, the state continued to support these developmental initiatives in Urabá and Caquetá, even when the regions degenerated into sites of labor militancy, guerrilla activity, and heightened political violence. This complex interplay of interregional dynamics across rural Colombia also acted in more direct ways. As we shall see, the successes and failures of each regime in absorbing labor and generating stable livelihoods pushed and pulled migratory flows of rural labor and settlement that impacted the strategies of labor control and labor politics of each. Understanding the indirect and unintentional ways that rural Colombia’s commodity regimes co-constitute one another and shape larger national development trends is a major finding of this book.

Measurement and Data

Analyzing the divergent spatial and temporal patterning of Colombia’s rural labor regimes from a comparative and world historical perspective requires extensive research on the complexities and particularities of each local regime, on Colombian state developmental policy and national political trends, on the core–periphery structures and governance institutions of the global coffee, banana, and cocaine markets, on US foreign policy, and more. Due to the breadth of the study, the research design naturally rests chiefly upon secondary sources, including the vast academic literature amassed by Colombian and North American social scientists and historians, governmental documents, publications issued by nongovernmental organizations and Colombian think tanks, as well as pamphlets and other documents issued by activist groups and organizations. These secondary texts were the central sources of empirical data used to construct the historical narratives for each of the three regional case studies.Footnote 25 While each of these secondary sources was written according to its own particular theoretical agenda, all of them use in-depth ethnographic and/or historical methods that were instrumental in either tracing the class dynamics of each local labor regime over time or in honing in on macro-structural transformations of the market for each commodity. The “value added” comes from bringing these different sources into dialogue with each other.

One of the most critical elements of the research design, however, is the capacity to identify and measure what may be considered the “dependent variable” of the study, namely, the spatial and temporal patterning of Colombia’s labor regimes across what I conceptualize as four distinct labor regime types: hegemony, despotism, counter-hegemony, and crises of control. This required longitudinal data that could distinguish the key mechanisms of labor control deployed and identify periods when these mechanisms were effective in maintaining capitalist control of the labor process.

Critical to my measurement of the key mechanisms of labor control deployed was the extent to which capital used violent labor repression. To operationalize “labor repression,” I spent a substantial amount of time amassing, recoding, and analyzing a longitudinal dataset that measures the number of incidents of state, paramilitary and other forms of political violence that occurred within each region over time. This data was originally compiled by a Bogotá-based Jesuit peace institute, the Popular Education Research Center (CINEP), which collected newspaper and human rights reports of all incidents of political violence that occurred in the country and published their findings in the journal Justicia y Paz (1987–96) and later in the journal Noche y Niebla (1996–present). This data was particularly useful because it specified the type of violent act perpetrated, which I then recoded to distinguish acts of labor repression such as death threats, kidnappings, killings, massacres, and other acts of violence that are meant to repress a regional population of commodity producers, workers, and peasants already under its effective control from acts of warfare such as combat activity, raids, territorial skirmishes between armed groups (state forces, paramilitaries, guerrillas, etc.) that arise from territorial struggles to control a region. The dataset also specified the group or individuals who allegedly perpetrated the act (including paramilitary groups, all branches and divisions of the Colombian armed forces, police forces, private individuals or groups, and guerrilla groups), the exact location and time in which the incident took place, the occupation of the victim, and a brief description of the context and circumstances in which the act of violence took place. Because this CINEP data only dates back to 1987, during the period when the developmental state was being dismantled and before the adoption of the neoliberal model, I assembled a research team that searched the archives of the largest Colombian newspaper, El Tiempo, and compiled all of the incidents of violence that occurred within the territorial demarcations of the regional cases from 1975 until the CINEP data began in 1987. This broader longitudinal dataset, which I call the “coercion dataset,” therefore covers the period from 1975 to 1987 and 1987 to 2017. This broad temporal sweep, from 1975 to 2017, was essential to capturing the general increases and decreases in the incidents of labor repression occurring within each region over the transition from the developmental to neoliberal eras.

Critical to my measurement of effective labor control was the extent to which workers and commodity producing farmers engaged in protest activities and political actions that challenged capitalist efforts to control their labor and land. In order to measure this contestation and labor unrest from below, I used three other key data sources in addition to the secondary texts. The first, also the product of CINEP investigators scanning domestic media sources and NGO reports, documented all known incidents of social protest activity that occurred across the country between 1975 and 2016. These protest incidents were coded according to the specific location in which the protest activity took place (including municipality and department), the time and date of its occurrence, the groups and actors involved, the target of the protest (state, local government, private business), and the type of protest activity that occurred (labor, peasant and indigenous, student, urban, and other actors).Footnote 26 In addition to the social protest data that captured the extra-institutional politics of each regime, I also analyzed electoral data compiled by the Colombian National Registry Office (RNEC). This data was critical to understand the institutional politics of each regime’s workers and commodity-producing farmers and to measure the extent to which local political positions remained dominated by traditional elite-led parties rather than falling into the hands of populist and leftist political parties. Finally, neither the social protest data nor the electoral data captured forms of labor unrest and class politics that arose through armed struggle. Since politics in Colombia is often militarized, and class struggles engulfed by guerrilla insurgency activity, I used the “coercion dataset” to trace the patterns of guerrilla activity in each region.

I spent a great deal of time and effort constructing and analyzing the datasets and the secondary literature. However, I also conducted multiple bouts of fieldwork in Colombia. The first period of fieldwork was in the summer of 2001, when I established initial contact with various organizations and individuals in Bogotá to ascertain whether the project was feasible or not. These initial contacts were essential in paving the way for a second round of fieldwork that I conducted over a twenty-month period between 2003 and 2004.Footnote 27 During this period, I was kindly afforded an office in Universidad de los Andes’ Centro de Investigaciones Socio-culturales e Internacionales (CESO) in Bogotá, which became my base of operations. During this time, I worked together with a group of research assistants to compile and code the data that became the coercion dataset.Footnote 28 I later updated this data in 2009–10, 2015–16, and 2018 with the assistance of numerous MA students at Florida Atlantic University.Footnote 29

Between 2003 and 2004, I conducted over forty structured and semi-structured interviews with key informants, including local, departmental and national governmental representatives, local and national military leaders and police officials, social and political activists, union leaders and rank-and-file militants, peasants and large landowners, workers and business leaders, and ex-guerrilla leaders, in addition to academics, specialists and experts, in addition to countless nonstructured interviews and conversations. It is worth noting that the feasibility of conducting qualitative research in Colombia has been severely limited by the widespread use of violence by public and private actors on both the left and the right of the political spectrum. Many academics have fallen victim to this violence, including the shooting of a leading political scientist at the National University in Bogotá. This “climate of fear” against academics, and particularly those who speak openly about human rights issues, was made painfully clear in a report that showed no fewer than twelve incidents of violence perpetuated against academics in 2006 alone!Footnote 30 For this reason, it was too risky for me to enter the Caguán region of Caquetá, which was considered to be a “hot spot” of political violence between 2003 and 2004. And while I was indeed successful in establishing rapport with many key informants who lived and worked in Urabá, a trip to this region was also avoided due to an unexpected incident in Bogotá in May of 2004, when I was drugged, beaten, robbed, and kidnapped for a short period. Despite these limitations, I was able to interview key actors from Urabá from the relative safety of Medellín, where both Augura‘s and Urabá’s banana worker union offices reside. Even operating with these precautions, I had to become accustomed to groups of armed men “testing my politics” before a scheduled interview, bouts of phone tag and scheduled meeting spaces that mysteriously took me from safe public spaces into dark corridors and remote fields, interviews with politicians and elites who appeared to maintain a strange inability to critique leftist guerrillas and interviews with labor activists who seemed unwilling to critique paramilitaries or local elites, situations that allow you to gain the loyalty of one group while simultaneously losing the capacity to enter sites occupied by antagonistic groups, the occasional provision of armed body guards and attack dogs when walking to and from interviews, and of course the pistol set strategically next to your microphone on the interview desk. Such is the nature of field research in Colombia, and is itself a reflection of the degree to which contemporary Colombian society has become characterized by coercive forms of domination and crisis.

Since these initial periods of fieldwork in 2001 and 2003–4, rural territorial contestation in Colombia has calmed, making it easier to enter field sites that were off limits at the time. To be sure, this relative calming of incidents of political violence is itself the product of a period of intense militarization and repression that began under the Uribe Administration (2002–10). Nonetheless, the expansion of state control over regions that had once been war zones allowed me to return to Colombia and conduct research in Urabá and Caquetá, in addition to Viejo Caldas, Medellín and Bogotá in recent years. In the summer of 2009, I conducted over thirty additional interviews with local labor and agrarian rights activists, government officials, union bosses, military officials, farmers, workers, displaced peasants, and others while visiting countless banana plantations, coffee fields, government offices, libraries, and military bases. I also returned to Colombia for a fourth bout of fieldwork in the summer of 2015, this time spending almost my entire time in Viejo Caldas, largely through the assistance of fellow academic traveler, Chris London, who set me up with an initial array of contacts in and around Pácora, Caldas. During this period, I interviewed another thirty+ people, including coffee farmers, activists, government officials, and extensions agents and others working with Fedecafé, largely to better understand the waves of cafetero militancy that have arisen over the past years. Finally, over the past years I have been able to supplement these bouts of fieldwork with skype and telephone interviews with key informants who have helped keep me up to date with current events occurring in the remote rural regions of this study. In total, I have conducted over 100 interviews, most of them in field sites. Rather than systematically incorporate these interviews into the narrative of each case study, I have used these interviews primarily as a guide to help clarify the dynamics of each case study as they unfolded over the broad historical periods analyzed.

Overall, this book is the product of nearly 20 years of research, including 4 rounds of fieldwork, over 100 structured and semi-structured interviews, and countless informal ones. An early version of this research was my dissertation thesis. Since then, various threads of it have been published as solo and coauthored articles in various scholarly journals, including Politics and Society, Global Labour Journal, Journal of World-Systems Research, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, Review: A Journal of the Fernand Braudel Center, and Journal of Agrarian Change. This gestation period has allowed me the opportunity to revisit the various conceptual arguments and substantive claims of the dissertation while providing greater time to familiarize myself with the historical nuances of the three regional cases through new bouts of fieldwork and deep immersion in the burgeoning secondary literatures on Colombian politics, coffee, bananas, and cocaine. Indeed, as most comparative historical sociologists would acknowledge, gaining familiarity with the complex social dynamics of the cases – including three regional regimes and three global markets – in addition to an understanding of how these dynamics were historically situated within the arc of US world hegemony requires significant reading of secondary sources and critical reflection. It is only through this book, however, that I have been able to satisfactorily knit these threads together into a coherent argument that captures the broad and deep dynamics of labor regime variation across macro-periods and micro-regions that are encapsulated here.

Chapter Outline

This book begins with a discussion of labor regimes theories that associate contemporary processes of neoliberal globalization with the rise of new forms of market despotism and forwards a new, more nuanced conceptualization of labor regime and development dynamics that arise at the margins of world capitalism. The remainder of the book is divided into three empirical parts, each of which focuses on a regional case study. The first case study focuses on the coffee regime of Viejo Caldas; the second on the banana regime of Urabá; and the third on the frontier regime of the Lower and Middle Caguán region of Caquetá. The geographic locations of these three regions are depicted in Map 1. Each case study is further segmented into two temporally distinct chapters in order to illuminate the continuities and changes in the nature of labor regimes over time. The first chapter of each regional case study examines the transformation of each labor regimes from its origins in the nineteenth century into the highpoint of US world hegemony in the postwar developmental decades of the twentieth century. The second chapter focuses on how these labor regime dynamics changed as US world hegemony unraveled and each regime was forced to adapt to world markets that have become unhindered by geopolitical regulations.

The first regional case study examines the trajectory of the coffee regime of Viejo Caldas. Chapter 2 examines the rise of Viejo Caldas as a site of coffee production for export during a period in which the global coffee market operated according to laissez-faire principles rooted in a British world hegemonic order. I highlight how two distinct structures of coffee production emerged – frontier smallholds and large coffee estates, both of which developed strategies to protect themselves from direct exposure to the market. I analyze how the large estates experiment with proletarianized labor forces triggered a wave of labor unrest that led to their dissolution by the 1930s. It was in this historical context that the National Federation of Coffee Growers took on parastatal responsibility for developing the sector based upon the smallholder structure of production. I examine Fedecafé’s developmentalist interventions in the sector and argue that these interventions facilitated the emergence of a hegemonic social compact (Pacto cafetero) that transformed the region’s smallholding producers into fully marketized cafetero farmers.

Chapter 3 recasts Fedecafé’s hegemonic social compact in world historical perspective, asking how and why it was successful despite the increasing dependence of cafetero farmers on coffee production for the market to meet their class reproduction needs. I argue that Fedecafé was able to exploit new opportunities in the international coffee market brought on by the rise of US world hegemony. Specifically, Colombia engaged in geopolitical collective action efforts that led to the establishment of international coffee agreements. These agreements politically regulated the market in ways that allowed Fedecafé to “move up” the coffee chain and avoid the social contradictions of peripheral proletarianization. I argue that the shift to crises of control came when the US pulled its support for the politically regulated world coffee market, essentially returning the market back to a highly volatile laissez-faire institutional structure and therefore re-peripheralizing Colombia’s market location. This re-peripheralization undermined Fedecafé’s social compact and thus the economic and social stability of cafetero farmers.

The second regional case study examines the trajectory of the banana regime of Urabá. Chapter 4 argues that the rise of paramilitary despotism in contemporary Urabá has been shaped by the historical geopolitics of the world banana market. It begins with an analysis of the rise and fall of the international banana market in the early half of the twentieth century. I point out that the banana market arose through the activities of a handful of powerful vertically integrated corporations that secured control of production through despotic means, but that this despotism gave way to a global wave of labor unrest and economic nationalism that forced the companies to vertically disintegrate their activities by mid-century. Next, I discuss how the banana market was restructured under the auspices of the United States, which encouraged domestic banana production as a developmentalist growth strategy but ultimately re-peripheralized the producer end of the market. Banana production in Urabá, I argue, arose during this period of developmental optimism. However, the region’s movement into a highly peripheralized niche forced Urabá’s banana elites to rely upon the authoritarian practices of the National Front regime to control labor and keep production costs low. Chapter 5 describes how the despotism of Urabá’s banana regime endured in the 1970s, but fell into crisis in the 1980s when the central state implemented a series of democratization reforms that opened new political opportunities to Urabá’s local working class. By the end of the decade, the workers succeeded in displacing elites from local political offices and using this leverage to grant concessions to banana unions. However, this crisis of labor control triggered a violent reaction from elites who relied upon paramilitarism to regain control of the region and therefore adapt to the competitive demands of the banana export market.

The final case study examines the rise and collapse of FARC counter-hegemony in the Caguán region of Caquetá. Chapter 6 analyzes the Caguán’s historic transformation from a frontier region comprised of displaced migrants in the 1960s into a despotic cattle regime under the control of Colombia’s Cattle Ranchers Association (Fedegán) by the 1970s and finally into a coca regime under the counter-hegemonic control of the FARC by the 1980s. I argue that FARC counter-hegemony was rooted in part in its ability to absorb populations of rural surplus labor that came to the region as a result of the dispossessing tendencies of the developmentalist politics of the state. It was also rooted in the FARC’s involvement in the illegal coca market, which granted them core-like profits that they used to consolidate a protective social compact vis-à-vis local cocalero producers. In this sense, the FARC’s interventions in the Caguán’s coca regime provide important points of convergence and divergence to the actions of the other developmental organizations analyzed, including Fedecafé and Augura as well as Fedegán, all of whom have struggled to adapt to the competitive demands of the world market.

In Chapter 7, I analyze how FARC counter-hegemony in the Caguán collapsed in the 2000s and 2010s. I show that the adoption of neoliberal economic policies in the 1990s bolstered FARC counter-hegemony because it created new waves of displaced migrants who sought shelter in coca-producing regions like the Caguán. However, I also show how Colombian neoliberalism provided the impetus for a significant shift in the region’s cattle industry from its historic production of meats and hides into the production of dry and powdered milks for export. This shift, in addition to the growth in the FARC’s presence, intensified struggles over control of the region. What eventually dismantled the FARC’s control of the region was a shift in geopolitics, as the FARC’s involvement in the illegal coca economy gained the attention of the United States, which intensified its aid to the Colombian military through its War on Drugs and War on Terror initiatives. This militarization of the region undermined the FARC’s ability to continue to protect local cocaleros, eventually leading to the collapse of the FARC’s labor regime altogether. It was in this context that the peace accords were signed. And it is in this context that we can see more clearly how the state’s central underlying problem is neither the FARC nor the coca economy, but rather how to respond to a crisis of surplus populations.

I conclude with a discussion of the key arguments of this book and some closing remarks on the capacity of the twenty-first- century world market to accommodate stable forms of social class reproduction and development for populations living at its margins.