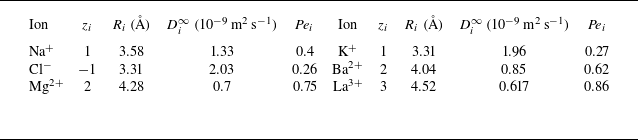

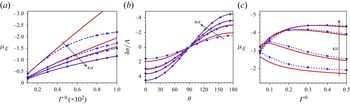

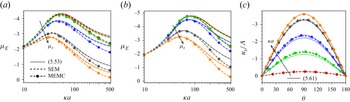

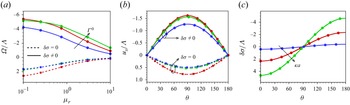

1. Introduction

Liquid droplets formed through the emulsification of immiscible liquids are ubiquitous in nature and widely used in industrial, biological and pharmaceutical applications. Their controlled transport under applied electric fields has enabled advancements in droplet-based microfluidics (Shui, Eijkel & Van den Berg Reference Shui, Eijkel and Van den Berg2007; Teh et al. Reference Teh, Lin, Hung and Lee2008), lab-on-a-chip devices (Haeberle & Zengerle Reference Haeberle and Zengerle2007), biomedical microelectromechanical system applications (Katsura et al. Reference Katsura, Yamaguchi, Inami, Matsuura, Hirano and Mizuno2001), targeted drug delivery, separation of biomolecules (e.g. RNA, DNA, proteins) (Keren Reference Keren2003), food toxin analysis (Juan-García et al. Reference Juan-García, Font and Picó2005) and oil recovery technologies (Qi et al. Reference Qi, Sun, Li, Chen, Liu and Li2022). Droplet manipulation minimises cross-contamination and enhances mixing efficiency, making it essential in processes ranging from cosmetics to food processing (Okochi & Nakano Reference Okochi and Nakano2000; Dickinson Reference Dickinson2011). Additionally, droplets serve as models for biological entities like cells and vesicles (Hochmuth et al. Reference Hochmuth, Ting-Beall, Beaty, Needham and Tran-Son-Tay1993; Lim, Zhou & Quek Reference Lim, Zhou and Quek2006), and their motion and deformation in viscous media play a critical role in crude-oil industries and colloid science (Frising, Noïk & Dalmazzone Reference Frising, Noïk and Dalmazzone2006; Abeynaike et al. Reference Abeynaike, Sederman, Khan, Johns, Davidson and Mackley2012).

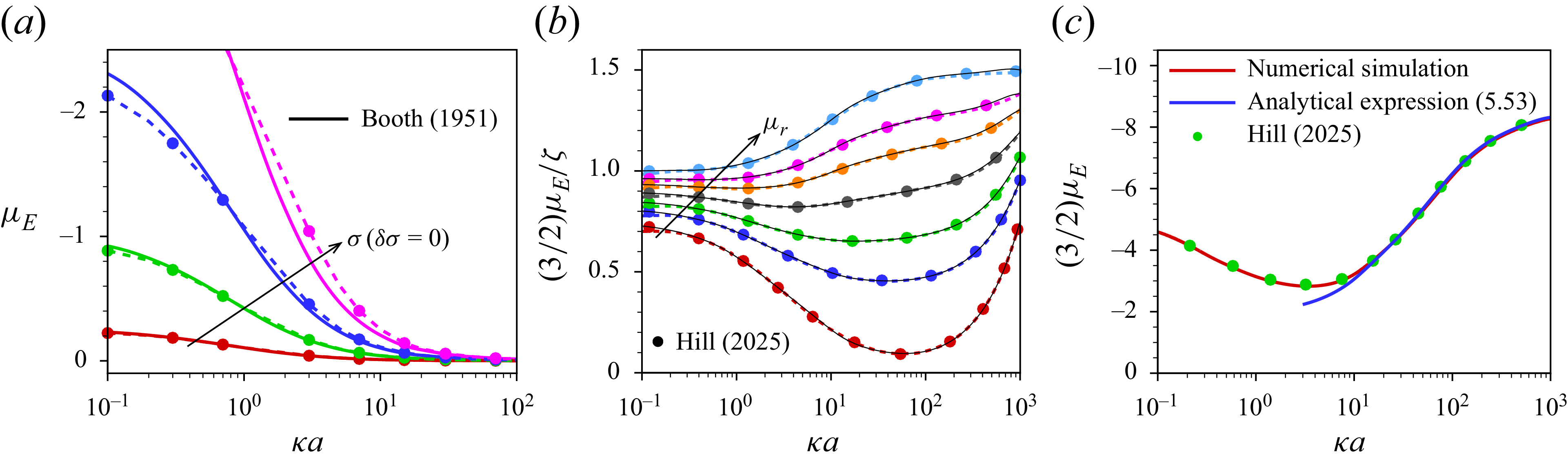

The electrophoresis of liquid droplets fundamentally differs from that of rigid particles due to the occurrence of Maxwell traction at the interface coupled with hydrodynamic stresses, and interfacial tension effects (Baygents & Saville Reference Baygents and Saville1991). Based on the Debye–Hückel approximation, Booth (Reference Booth1951) provided an analytical expression for the electrophoretic mobility of dielectric droplets by considering a uniformly charged and non-deformable interface with no surface tension gradients. Ohshima, Healy & White (Reference Ohshima, Healy and White1984) extended this framework to consider the electrophoresis of conducting mercury droplets with uniform surface charge density, providing mobility expressions under the assumptions of low

![]() $\zeta$

-potential as well as beyond the Debye–Hückel regime with thin-layer consideration, while ignoring surface tension effects. Recent studies (e.g. Schnitzer, Frankel & Yariv Reference Schnitzer, Frankel and Yariv2014; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Fan, Jian and Lee2021) on the electrophoresis of non-polarisable droplets with uniform surface charge have found a discontinuous variation of mobility with surface charge density or

$\zeta$

-potential as well as beyond the Debye–Hückel regime with thin-layer consideration, while ignoring surface tension effects. Recent studies (e.g. Schnitzer, Frankel & Yariv Reference Schnitzer, Frankel and Yariv2014; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Fan, Jian and Lee2021) on the electrophoresis of non-polarisable droplets with uniform surface charge have found a discontinuous variation of mobility with surface charge density or

![]() $\zeta$

-potential. Mahapatra, Ohshima & Gopmandal (Reference Mahapatra, Ohshima and Gopmandal2022) analysed the electrophoresis of polarisable hydrophobic droplets of constant surface charge density with no Marangoni effects and derived analytical expressions for the mobility within the Debye–Hückel regime. While these models provide valuable insights under idealised conditions, they do not capture the coupling between surface charge transport, interfacial flow and surface tension gradients that arises in the presence of adsorbed ionic surfactants. The presence of surfactant molecules that adsorb at the interface further modifies the droplet dynamics (Levich Reference Levich1962; Manikantan & Squires Reference Manikantan and Squires2020). Surfactants, which stabilise the droplet interface, can redistribute due to advection, diffusion and interfacial electric stresses. This redistribution creates gradients in interfacial tension, resulting in Marangoni stresses. These stresses significantly alter the electrophoretic mobility of droplets, often resulting in behaviour distinct from that of rigid particles or surfactant-free droplets. Understanding these dynamics is vital for optimising drug delivery, oil recovery and advanced materials.

$\zeta$

-potential. Mahapatra, Ohshima & Gopmandal (Reference Mahapatra, Ohshima and Gopmandal2022) analysed the electrophoresis of polarisable hydrophobic droplets of constant surface charge density with no Marangoni effects and derived analytical expressions for the mobility within the Debye–Hückel regime. While these models provide valuable insights under idealised conditions, they do not capture the coupling between surface charge transport, interfacial flow and surface tension gradients that arises in the presence of adsorbed ionic surfactants. The presence of surfactant molecules that adsorb at the interface further modifies the droplet dynamics (Levich Reference Levich1962; Manikantan & Squires Reference Manikantan and Squires2020). Surfactants, which stabilise the droplet interface, can redistribute due to advection, diffusion and interfacial electric stresses. This redistribution creates gradients in interfacial tension, resulting in Marangoni stresses. These stresses significantly alter the electrophoretic mobility of droplets, often resulting in behaviour distinct from that of rigid particles or surfactant-free droplets. Understanding these dynamics is vital for optimising drug delivery, oil recovery and advanced materials.

The modelling of ionic surfactants at fluid–fluid interfaces remains an area of active research, with no clear consensus on how to accurately describe the charge distribution at the interface. Kralchevsky et al. (Reference Kralchevsky, Danov, Broze and Mehreteab1999) and Kralchevsky & Danov (Reference Kralchevsky and Danov2015) describe a thermodynamically consistent model for surface tension isotherms at interfaces with adsorbed ionic or non-ionic species which are in equilibrium with the adjacent diffuse electric double layer (EDL). Depending on the granularity of the modelling approach for the interface and its surface tension isotherm, this allows a consistent coarse-grained treatment of an effective interface comprising both surface layer and EDL as a lumped model or a detailed microscopic approach with a separate treatment of the surface isotherm for the adsorbed species and a resolved diffuse ion cloud. The contribution related to surface adsorption can be modelled by one of the commonly employed surface isotherms such as the Langmuir, Vollmer or Frumkin isotherms (Kralchevsky et al. Reference Kralchevsky, Danov, Broze and Mehreteab1999; Kralchevsky & Danov Reference Kralchevsky and Danov2015; Manikantan & Squires Reference Manikantan and Squires2020), while a Gouy–Chapman model can be applied to describe the EDL. This approach also facilitates a thermodynamically consistent treatment of specifically adsorbed counterions forming a ’Stern layer’ on the surfactant layer. A similar modelling approach was already adopted by Baygents & Saville (Reference Baygents and Saville1991) for analysing the electrophoresis of drops and bubbles, albeit using a simple Henry isotherm for the surface model and a resolved ion cloud modelled by the Poisson–Nernst–Planck equations appropriate under dilute conditions. Prosser & Franses (Reference Prosser and Franses2001) and Ivanov, Ananthapadmanabhan & Lips (Reference Ivanov, Ananthapadmanabhan and Lips2006) review coarse-grained equilibrium surface tension models for the description of experimentally obtained surface tension isotherms.

Hill & Afuwape (Reference Hill and Afuwape2020) developed a thin-double-layer approximation retaining temporal fluid inertia to investigate the mobility of nano-drops in the presence of charged surfactants with no exchange of surfactant between the interface and the immediately adjacent electrolyte under oscillating applied electric and sonic pressure fields. Subsequently, Hill (Reference Hill2020) presented an exact numerical solution for the electrophoresis of surfactant-stabilised emulsion drops including the surfactant exchange kinetics. Experimental interpretations of these theoretical studies (Hill & Afuwape Reference Hill and Afuwape2020; Hill Reference Hill2020) are made in Afuwape & Hill (Reference Afuwape and Hill2021) by measuring the dynamic mobility spectra as well as interfacial tension isotherms of oil drops with irreversibly adsorbed charged surfactants and also illustrated the effects due to Marangoni and Maxwell stresses. These studies address discrepancies between measured mobilities and inferred

![]() $\zeta$

-potentials, suggesting that the use of the Smoluchowski formula may not fully capture the complexities of surfactant effects at highly charged interfaces even for thin double layers. Building on this foundation, Hill (Reference Hill2025) investigated the impact of both irreversibly bound and soluble surfactants on droplet electrophoresis through numerical simulation based on the first-order perturbation from equilibrium. In that study it is demonstrated that the singularity in the electrophoretic mobility of a droplet, which occurs as its uniform, immobile surface charge density is varied, is regularised when the surface charge is considered mobile. Based on the Debye–Hückel approximation, Ohshima (Reference Ohshima2025a

) derived an analytical expression for the electrophoretic mobility of an oil drop that acquires its surface charge through ion adsorption following a linear adsorption isotherm, assuming instantaneous interfacial equilibrium between adsorbed and dissolved surfactants. The linear isotherm neglects finite site saturation effects, which can strongly influence interfacial Marangoni stresses at high surfactant coverage. He further showed that the resulting expression is independent of the drop’s relative dielectric permittivity. That work was subsequently extended to gel media (Ohshima Reference Ohshima2025b

). However, existing studies on the electrophoresis of droplets have not derived analytical solutions beyond the Debye–Hückel approximation for droplets laden with ionic surfactants.

$\zeta$

-potentials, suggesting that the use of the Smoluchowski formula may not fully capture the complexities of surfactant effects at highly charged interfaces even for thin double layers. Building on this foundation, Hill (Reference Hill2025) investigated the impact of both irreversibly bound and soluble surfactants on droplet electrophoresis through numerical simulation based on the first-order perturbation from equilibrium. In that study it is demonstrated that the singularity in the electrophoretic mobility of a droplet, which occurs as its uniform, immobile surface charge density is varied, is regularised when the surface charge is considered mobile. Based on the Debye–Hückel approximation, Ohshima (Reference Ohshima2025a

) derived an analytical expression for the electrophoretic mobility of an oil drop that acquires its surface charge through ion adsorption following a linear adsorption isotherm, assuming instantaneous interfacial equilibrium between adsorbed and dissolved surfactants. The linear isotherm neglects finite site saturation effects, which can strongly influence interfacial Marangoni stresses at high surfactant coverage. He further showed that the resulting expression is independent of the drop’s relative dielectric permittivity. That work was subsequently extended to gel media (Ohshima Reference Ohshima2025b

). However, existing studies on the electrophoresis of droplets have not derived analytical solutions beyond the Debye–Hückel approximation for droplets laden with ionic surfactants.

Experimentally, it is widespread practice to interpret the electrophoretic mobility of drops or bubbles assuming a fully immobilised interface (e.g. Hunter Reference Hunter1981; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Dabros, Li, Czarnecki and Masliyah2001; Pullanchery et al. Reference Pullanchery, Kulik, Okur, De Aguiar and Roke2020), often rationalised by the effect of adsorbed surfactant on the compressibility of the interface. Wuzhang et al. (Reference Wuzhang, Song, Sun, Pan and Li2015) measured the electrophoretic mobility of droplets in the presence of charged surfactants but did not attempt to model their results. Instead, they invoked the formation of a stagnant cap on certain regions of the interface to explain the vortices observed in their experiments.

Most of the existing theories on electrophoresis are based on simplified assumptions, such as ion as point charge (O’Brien & White Reference O’Brien and White1978; Ohshima et al. Reference Ohshima, Healy and White1983, Reference Ohshima, Healy and White1984; Kim, Nakayama & Yamamoto Reference Kim, Nakayama and Yamamoto2006), which neglects hydrodynamic steric hindrance between ions (Khair & Squires Reference Khair and Squires2009) and ion–ion correlations (Bazant, Storey & Kornyshev Reference Bazant, Storey and Kornyshev2011). The electrokinetics for such cases is governed by the standard electrokinetic model (SEM), based on the Poisson–Nernst–Planck–Navier–Stokes equations (O’Brien & White Reference O’Brien and White1978; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Nakayama and Yamamoto2006; Schnitzer et al. Reference Schnitzer, Frankel and Yariv2013, Reference Schnitzer, Frankel and Yariv2014; Cobos & Khair Reference Cobos and Khair2023). These assumptions suffice for dilute electrolytes and low surface charge densities but fail to capture the non-ideal behaviour at a high ionic concentration of electrolytes or highly charged interfaces. In such cases, the finite size of ions introduces steric interactions that limit the accumulation of counterions near the surface, creating counterion saturation. Ion–ion electrostatic correlations become significant in multivalent electrolytes (Storey & Bazant Reference Storey and Bazant2012; Stout & Khair Reference Stout and Khair2014; de Souza & Bazant Reference de Souza and Bazant2020), modifying the structure of the EDL (Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Govind Rajan, Carter and Stone2020). Consideration of the ion–ion correlations in electrokinetics can explain several non-ideal phenomena such as like-charge attraction, occurrence of reversal in mobility of a charged particle in multivalent counterions and the development of a layered structure of ions in the EDL (Semenov et al. Reference Semenov, Raafatnia, Sega, Lobaskin, Holm and Kremer2013; Kubíčková et al. Reference Kubíčková, Křížek, Coufal, Vazdar, Wernersson, Heyda and Jungwirth2012; Agrawal, Duan & Wang Reference Agrawal, Duan and Wang2023).

Under a continuum hypothesis, Bazant et al. (Reference Bazant, Storey and Kornyshev2011) and Storey & Bazant (Reference Storey and Bazant2012) developed a model which accounts for the correlations of finite-sized ions based on the non-local electrostatic approach (Hildebrandt et al. Reference Hildebrandt, Blossey, Rjasanow, Kohlbacher and Lenhof2004). This model is implemented by several authors (Stout & Khair Reference Stout and Khair2014; Alidoosti & Zhao Reference Alidoosti and Zhao2018; Misra et al. Reference Misra, de Souza, Blankschtein and Bazant2019; Paik, Bhattacharyya & Majhi Reference Paik, Bhattacharyya and Majhi2024) to illustrate the electrokinetics of rigid colloids in multivalent electrolytes and demonstrate the layering structure of ions in EDL and electrophoretic mobility reversal. This model also provides better agreement of the mobility of colloids with experimental observations (Stout & Khair Reference Stout and Khair2014; Paik et al. Reference Paik, Bhattacharyya and Majhi2024). However, similar investigations on liquid droplets are yet to be conducted. Recently, Majhi & Bhattacharyya (Reference Majhi and Bhattacharyya2024) examined droplet electrophoresis by incorporating ion steric interactions under the assumption of neutral surfactants on charged surfaces, demonstrating rigidification in the presence of neutral surfactants. However, they did not account for the electrostatic ion–ion correlation effects in their model, which manifests for multivalent electrolytes. In the recent past, several experimental studies (Li & Somasundaran Reference Li and Somasundaran1991, Reference Li and Somasundaran1992) have reported mobility reversal of gaseous bubbles in multivalent electrolytes, which cannot be explained based on the mean-field-based electrokinetic models. Nevertheless, no theoretical attempt to elucidate such phenomena in the context of fluid droplets has been made. Thus, a unified treatment that combines surfactant dynamics with short-range correlations and steric interactions of finite-sized ions is important in the context of droplet electrophoresis.

In this paper, a mathematical model is developed to describe the electrophoresis of droplets laden with insoluble, compressible ionic surfactants, which are irreversibly bound to the interface and do not exchange with the surrounding electrolyte medium during the flow. A modified electrokinetic formulation, MEMC (modified electrokinetic model with correlations), is employed, which incorporates ion steric interactions and electrostatic ion–ion correlations of finite-sized ions. The hydrodynamic ion steric interaction is governed by the Boublík–Mansoori–Carnahan–Starling–Leland (BMCSL) equation of state (Boublík Reference Boublík1970; Bazant et al. Reference Bazant, Kilic, Storey and Ajdari2009). As the ions are considered as finite-sized, the viscosity of the electrolyte medium and, consequently, the diffusivity of ions vary with the local ionic volume fraction, which are modelled by the Batchelor–Green two-particle hydrodynamics framework (Batchelor & Green Reference Batchelor and Green1972). Electrostatic ion–ion correlations are integrated into the model based on the Bazant–Storey–Kornyshev approach (Bazant et al. Reference Bazant, Storey and Kornyshev2011), which modifies the classical Poisson equation into the fourth-order modified Poisson equation for the electric potential.

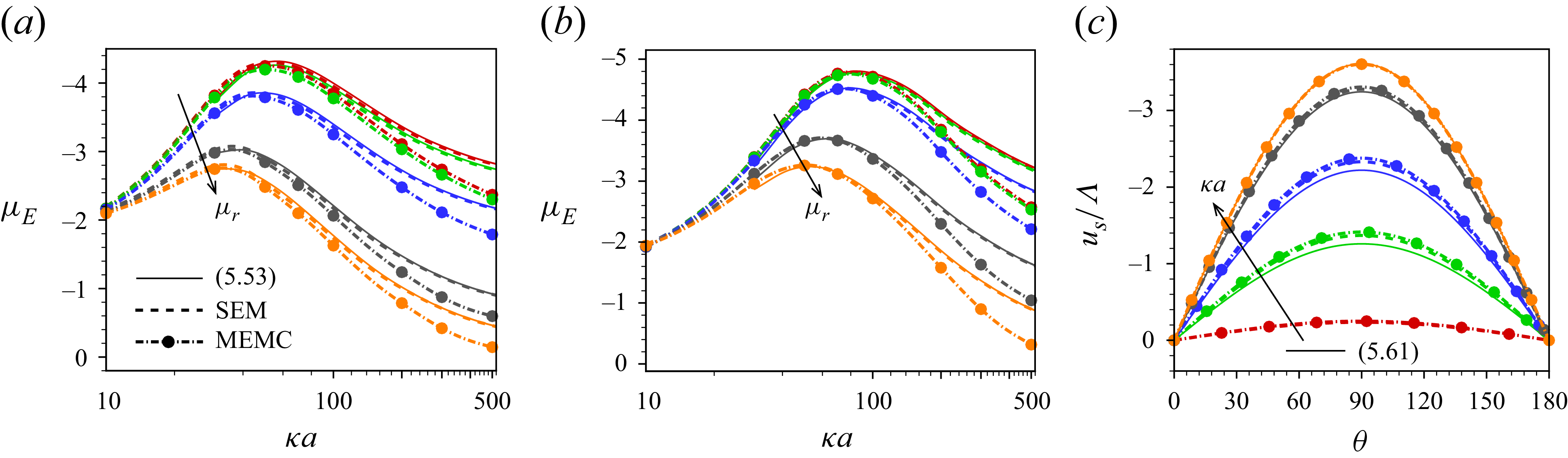

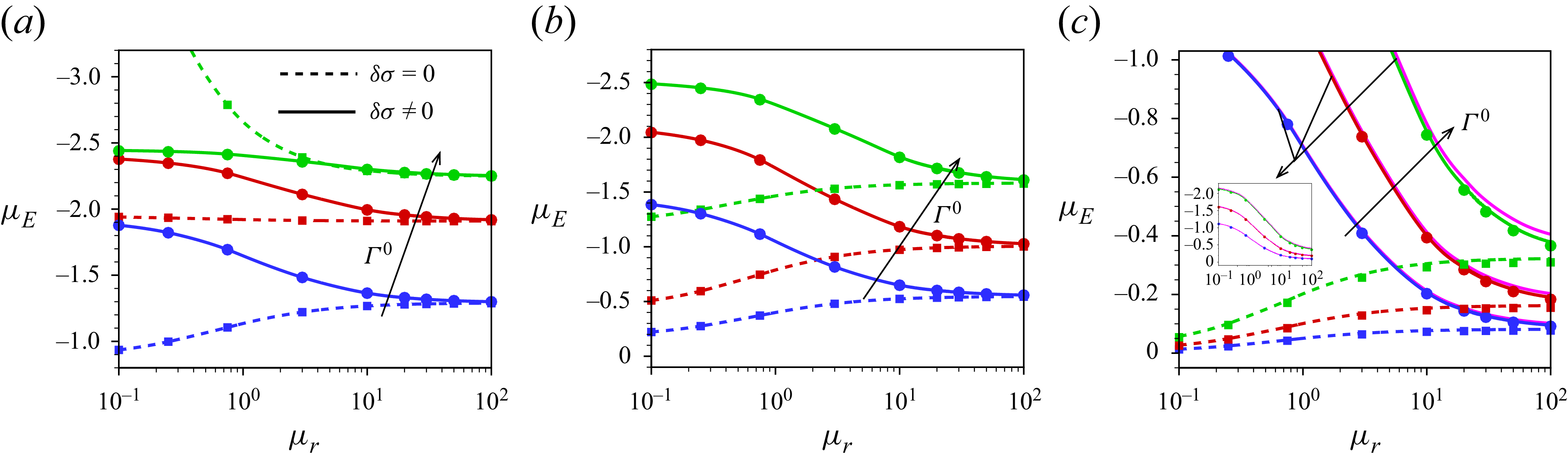

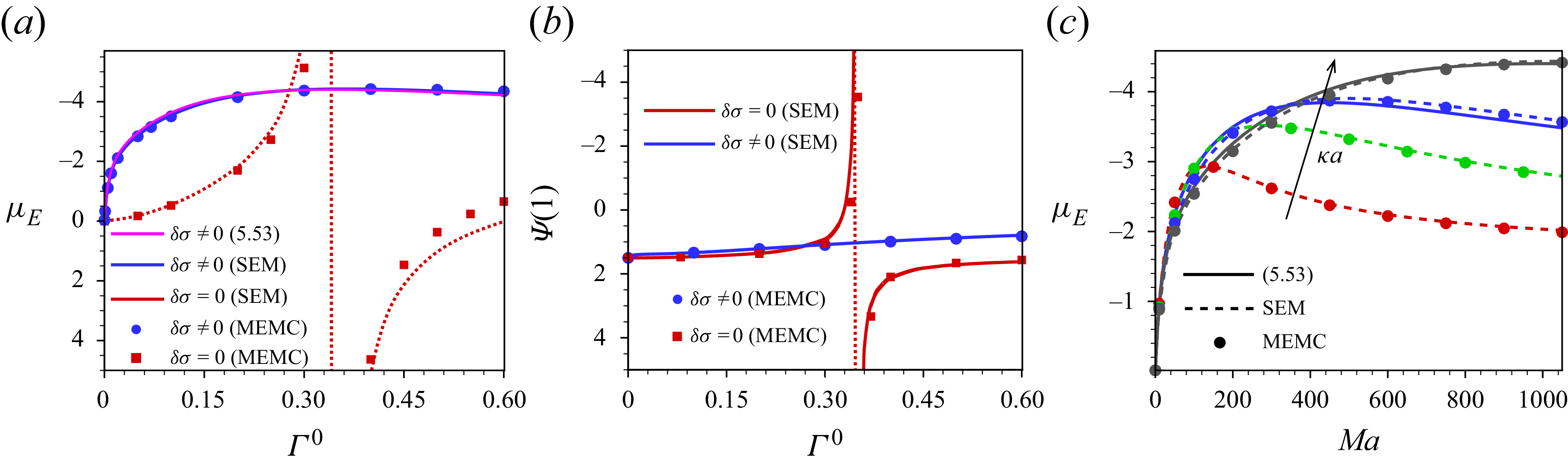

Our analysis is based on the numerical solution of the resulting equations describing the electrokinetics up to linear order in the applied electric field. It is worth noting that the numerical solution of the full set of electrokinetic equations does not deviate from the present approach for a moderate range of the applied electric field. The present MEMC reduces to the point-charge-based SEM for certain values of the parameters. We derive analytical solutions based on the SEM under the Debye–Hückel approximation, valid for a range of surface charge density for which the surface potential is lower than the thermal potential, as well as under the thin-Debye-layer consideration applicable for an arbitrary equilibrium surface potential. Under certain conditions the present Debye–Hückel-based solution reduces to several existing analytical expressions for mobility. Through the numerical solution of our modified model, we have shown the mobility reversal in droplet electrophoresis in a trivalent electrolyte. This study advances the theoretical understanding of droplet electrophoresis incorporating non-ideal effects in ion transport to get further insights into droplet electrophoresis, which may offer guidance for the design and optimisation of droplet-based nanofluidics and emulsion-based technologies.

2. Mathematical model

We consider the electrophoresis of a surfactant-laden liquid spherical droplet of radius

![]() $a$

immersed in an incompressible ionised fluid of permittivity

$a$

immersed in an incompressible ionised fluid of permittivity

![]() $\epsilon _e$

and viscosity

$\epsilon _e$

and viscosity

![]() $\mu ^{*}_{e}$

moving with electrophoretic velocity

$\mu ^{*}_{e}$

moving with electrophoretic velocity

![]() $U^{^*}_{E}$

in response to an external electric field

$U^{^*}_{E}$

in response to an external electric field

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}^{\infty }$

. The fluid inside the droplet is incompressible, immiscible with the outer fluid and electrically neutral and its viscosity is

$\boldsymbol{E}^{\infty }$

. The fluid inside the droplet is incompressible, immiscible with the outer fluid and electrically neutral and its viscosity is

![]() $\overline {\mu }$

. There is no electrolyte ionic species inside the droplet or no electrolyte ion can penetrate through its surface. The surface charge

$\overline {\mu }$

. There is no electrolyte ionic species inside the droplet or no electrolyte ion can penetrate through its surface. The surface charge

![]() $\sigma ^{*}$

is created due to the presence of insoluble charged surfactant molecules at the droplet surface and it can be obtained as

$\sigma ^{*}$

is created due to the presence of insoluble charged surfactant molecules at the droplet surface and it can be obtained as

![]() $\sigma ^{*}=\sum _{i}{z_{s,i}e\varGamma ^{*}_{i}}$

, where

$\sigma ^{*}=\sum _{i}{z_{s,i}e\varGamma ^{*}_{i}}$

, where

![]() $\varGamma ^{*}_{i}$

and

$\varGamma ^{*}_{i}$

and

![]() $z_{s,i}$

are the concentration and valency of

$z_{s,i}$

are the concentration and valency of

![]() $i\text{th}$

components of the surfactant. Variables with an asterisk are dimensional. A spherical polar coordinate system (

$i\text{th}$

components of the surfactant. Variables with an asterisk are dimensional. A spherical polar coordinate system (

![]() $r,\theta ,\psi$

) is adopted with its origin fixed at the centre of the droplet and the

$r,\theta ,\psi$

) is adopted with its origin fixed at the centre of the droplet and the

![]() $z$

axis (

$z$

axis (

![]() $\theta = 0$

) along the imposed electric field

$\theta = 0$

) along the imposed electric field

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}^{\infty }$

. Figure 1 provides a schematic illustration of the problem under consideration.

$\boldsymbol{E}^{\infty }$

. Figure 1 provides a schematic illustration of the problem under consideration.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of a surfactant-laden spherical droplet moving with electrophoretic velocity

![]() $U^{*}_{E}$

under the impact of external electric field

$U^{*}_{E}$

under the impact of external electric field

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}^{\infty }=E^{\infty }\boldsymbol{e_z}$

in an electrolyte solution where hydrated radius and valency of cations (subscript ‘+’) and anions (subscript ‘−’) are given by

$\boldsymbol{E}^{\infty }=E^{\infty }\boldsymbol{e_z}$

in an electrolyte solution where hydrated radius and valency of cations (subscript ‘+’) and anions (subscript ‘−’) are given by

![]() $R_{+,-}$

and

$R_{+,-}$

and

![]() $z_{+,-}$

, respectively.

$z_{+,-}$

, respectively.

For a highly charged surface in an electrolyte with multivalent counterions the electric coupling parameter providing the ratio between the inter-ionic spacing and the Guoy–Chapman length becomes large. In this case the mobile ions are laterally correlated with the surface charge (Grosberg, Nguyen & Shklovskii Reference Grosberg, Nguyen and Shklovskii2002). In order to account for the impact of electrostatic ion–ion correlations, Bazant et al. (Reference Bazant, Storey and Kornyshev2011) developed a fourth-order modified Poisson equation (MPE) for electric potential based on the non-local electrostatic approach. This introduces an additional parameter, the correlation length

![]() $\ell _{c}$

, which is bounded by the ion diameter (lower limit) and

$\ell _{c}$

, which is bounded by the ion diameter (lower limit) and

![]() $V^{2}_{c}l_{B}$

(upper limit). Here,

$V^{2}_{c}l_{B}$

(upper limit). Here,

![]() $V_{c}$

is the valency of the counterion and

$V_{c}$

is the valency of the counterion and

![]() $\ell _{B}=e^2/4\pi \epsilon _e k_BT$

is the Bjerrum length. The latter corresponds to the distance at which the electrostatic interaction energy between a pair of monovalent ions equals the thermal energy; in aqueous medium,

$\ell _{B}=e^2/4\pi \epsilon _e k_BT$

is the Bjerrum length. The latter corresponds to the distance at which the electrostatic interaction energy between a pair of monovalent ions equals the thermal energy; in aqueous medium,

![]() $\ell _{B}\sim 0.7\,\textrm{nm}$

. If the distance between ions exceeds

$\ell _{B}\sim 0.7\,\textrm{nm}$

. If the distance between ions exceeds

![]() $\ell _{c}$

, they primarily experience mean-field electrostatics. However, when the distance is smaller than

$\ell _{c}$

, they primarily experience mean-field electrostatics. However, when the distance is smaller than

![]() $\ell _{c}$

, Coulombic electrostatic correlations become significant, requiring a higher-order correction to the traditional Poisson equation. The MPE is written as

$\ell _{c}$

, Coulombic electrostatic correlations become significant, requiring a higher-order correction to the traditional Poisson equation. The MPE is written as

where

![]() $\psi ^{*}$

is the electrostatic potential and

$\psi ^{*}$

is the electrostatic potential and

![]() $\rho ^{*}_e=\sum _{i=1}^{N}{z_{i}en^{*}_{i}}$

is the space charge density in which

$\rho ^{*}_e=\sum _{i=1}^{N}{z_{i}en^{*}_{i}}$

is the space charge density in which

![]() $n^{*}_{i}$

is the ionic concentration of the

$n^{*}_{i}$

is the ionic concentration of the

![]() $i{\text{th}}$

ionic species with valency

$i{\text{th}}$

ionic species with valency

![]() $z_{i}$

. Upon non-dimensionalising, using the droplet radius

$z_{i}$

. Upon non-dimensionalising, using the droplet radius

![]() $a$

as length scale, (2.1) becomes

$a$

as length scale, (2.1) becomes

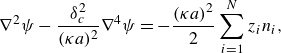

\begin{equation} {\nabla}^{2}\psi -\frac {\delta ^{2}_{c}}{(\kappa a)^{2}}{\nabla}^{4}\psi =-\frac {(\kappa a)^{2}}{2}\sum _{i=1}^{N}{z_{i}n_{i}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {\nabla}^{2}\psi -\frac {\delta ^{2}_{c}}{(\kappa a)^{2}}{\nabla}^{4}\psi =-\frac {(\kappa a)^{2}}{2}\sum _{i=1}^{N}{z_{i}n_{i}}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $\psi$

and

$\psi$

and

![]() $n_{i}$

are, respectively, the dimensionless electric potential, scaled by the thermal potential,

$n_{i}$

are, respectively, the dimensionless electric potential, scaled by the thermal potential,

![]() $\psi _{0}=k_{B}T/e$

, and the ionic concentration of the

$\psi _{0}=k_{B}T/e$

, and the ionic concentration of the

![]() $i{\text{th}}$

ionic species, scaled by the bulk ionic strength,

$i{\text{th}}$

ionic species, scaled by the bulk ionic strength,

![]() $I$

. Length

$I$

. Length

![]() $\kappa ^{-1}$

is the Debye length defined as

$\kappa ^{-1}$

is the Debye length defined as

![]() $\kappa ^{-1}=\sqrt {\epsilon _e\psi _{0}/2Ie}$

and

$\kappa ^{-1}=\sqrt {\epsilon _e\psi _{0}/2Ie}$

and

![]() $I$

is the ionic strength in the bulk defined by

$I$

is the ionic strength in the bulk defined by

![]() $I=(1/2)\sum _{i=1}^{N}{z^{2}_{i}n^{\infty }_{i}}$

, where

$I=(1/2)\sum _{i=1}^{N}{z^{2}_{i}n^{\infty }_{i}}$

, where

![]() $n^{\infty }_{i}$

is the dimensional bulk concentration of the

$n^{\infty }_{i}$

is the dimensional bulk concentration of the

![]() $i\text{th}$

ionic species. Length

$i\text{th}$

ionic species. Length

![]() $\delta _{c}$

is the dimensionless correlation length scaled by

$\delta _{c}$

is the dimensionless correlation length scaled by

![]() $\kappa ^{-1}$

, i.e.

$\kappa ^{-1}$

, i.e.

![]() $\delta _{c}=\ell _{c}\kappa$

. De Souza & Bazant (Reference de Souza and Bazant2020) provide a power-law relationship of

$\delta _{c}=\ell _{c}\kappa$

. De Souza & Bazant (Reference de Souza and Bazant2020) provide a power-law relationship of

![]() $\delta _{c}$

in terms of the Gouy–Chapman length,

$\delta _{c}$

in terms of the Gouy–Chapman length,

![]() $\ell _{GC}$

, the Bjerrum length,

$\ell _{GC}$

, the Bjerrum length,

![]() $V^{2}_{c}\ell _{B}$

, and the Debye length,

$V^{2}_{c}\ell _{B}$

, and the Debye length,

![]() $\kappa ^{-1}$

, and can be expressed as

$\kappa ^{-1}$

, and can be expressed as

where

![]() $\ell _{GC}$

can be calculated as

$\ell _{GC}$

can be calculated as

![]() $\ell _{GC}=e(2\pi V_{c}\ell _{B}\sigma ^{*})^{-1}$

in which

$\ell _{GC}=e(2\pi V_{c}\ell _{B}\sigma ^{*})^{-1}$

in which

![]() $\sigma ^{*}$

is the surface charge density at the droplet surface. In order to solve the MPE for electric potential, the following boundary condition can be imposed at the droplet interface:

$\sigma ^{*}$

is the surface charge density at the droplet surface. In order to solve the MPE for electric potential, the following boundary condition can be imposed at the droplet interface:

Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}$

is the outward unit normal vector at the surface. We assume that the electric permittivity

$\boldsymbol{n}$

is the outward unit normal vector at the surface. We assume that the electric permittivity

![]() $\epsilon _d$

of the droplet is much smaller than the permittivity of the surrounding fluid,

$\epsilon _d$

of the droplet is much smaller than the permittivity of the surrounding fluid,

![]() $\epsilon _d \ll \epsilon _e$

, as is usually suitable for oil droplets in water. In this case, the electric field variation inside the droplet has a negligible influence on boundary conditions such as (2.4) at the interface (Schnitzer et al. Reference Schnitzer, Frankel and Yariv2014; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Fan, Jian and Lee2021).

$\epsilon _d \ll \epsilon _e$

, as is usually suitable for oil droplets in water. In this case, the electric field variation inside the droplet has a negligible influence on boundary conditions such as (2.4) at the interface (Schnitzer et al. Reference Schnitzer, Frankel and Yariv2014; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Fan, Jian and Lee2021).

In the present study, we restrict ourselves to a single adsorbed species with surface concentration

![]() $\varGamma ^{*}$

and valency

$\varGamma ^{*}$

and valency

![]() $z_{s}$

. In this case,

$z_{s}$

. In this case,

![]() $\sigma ^{*}=z_{s}e\varGamma ^{*}$

. The dimensionless form of the above boundary condition (2.4) is obtained as

$\sigma ^{*}=z_{s}e\varGamma ^{*}$

. The dimensionless form of the above boundary condition (2.4) is obtained as

The dimensionless surface charge density

![]() $\sigma$

is given by

$\sigma$

is given by

![]() $\sigma =z_{s}Ma\varGamma$

, in which the surfactant concentration

$\sigma =z_{s}Ma\varGamma$

, in which the surfactant concentration

![]() $\varGamma ^{*}$

is scaled by

$\varGamma ^{*}$

is scaled by

![]() $\varGamma ^{\infty }$

. Here

$\varGamma ^{\infty }$

. Here

![]() $\varGamma ^{\infty }$

is the maximum packing surface concentration of the surfactant at the interface and

$\varGamma ^{\infty }$

is the maximum packing surface concentration of the surfactant at the interface and

![]() $\textit{Ma}$

is the Marangoni number defined as

$\textit{Ma}$

is the Marangoni number defined as

![]() $\textit{Ma}=ea\varGamma ^{\infty }/\epsilon _e\psi _{0}$

, or equivalently,

$\textit{Ma}=ea\varGamma ^{\infty }/\epsilon _e\psi _{0}$

, or equivalently,

![]() $\textit{Ma}=k_{B}T\varGamma ^{\infty }/\mu U_{0}$

. In the present formulation,

$\textit{Ma}=k_{B}T\varGamma ^{\infty }/\mu U_{0}$

. In the present formulation,

![]() $\textit{Ma}$

represents the ratio of the characteristic surfactant-induced surface-pressure stress,

$\textit{Ma}$

represents the ratio of the characteristic surfactant-induced surface-pressure stress,

![]() $k_B T\,\varGamma ^\infty /a$

, to the characteristic viscous stress,

$k_B T\,\varGamma ^\infty /a$

, to the characteristic viscous stress,

![]() $\mu U_0/a$

. Here,

$\mu U_0/a$

. Here,

![]() $U_0=\epsilon _e \psi _0^{2}/a\mu$

is the velocity scale and

$U_0=\epsilon _e \psi _0^{2}/a\mu$

is the velocity scale and

![]() $\mu$

is the dynamic viscosity of the electrolyte at infinite dilution. The dielectric displacement vector with non-local electrostatic consideration becomes

$\mu$

is the dynamic viscosity of the electrolyte at infinite dilution. The dielectric displacement vector with non-local electrostatic consideration becomes

![]() $\boldsymbol{D}^{*}=\epsilon _e(\ell ^{2}_{c}{{\nabla} ^{*}}^{2}-1)\boldsymbol{E^{*}}$

, and with that the Maxwell stress

$\boldsymbol{D}^{*}=\epsilon _e(\ell ^{2}_{c}{{\nabla} ^{*}}^{2}-1)\boldsymbol{E^{*}}$

, and with that the Maxwell stress

![]() $S^{*}_{E}$

becomes (de Souza & Bazant Reference de Souza and Bazant2020)

$S^{*}_{E}$

becomes (de Souza & Bazant Reference de Souza and Bazant2020)

\begin{align} S^{*}_{E}&=\epsilon _e\left [\boldsymbol{E^{*}E^{*}}-\frac {1}{2}{E^{*}}^2 \boldsymbol{I}\right ]\nonumber\\ &\quad +\epsilon _e\ell ^{2}_{c}\left [(\boldsymbol{E^{*}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }{{\nabla} ^{*}}^{2}\boldsymbol{E^{*}})\boldsymbol{I}-\boldsymbol{E^{*}}({{\nabla} ^{*}}^{2}\boldsymbol{E^{*}})-({{\nabla} ^{*}}^{2}\boldsymbol{E^{*}})\boldsymbol{E^{*}}+\frac {1}{2}({{\nabla} ^{*}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{E^{*}})^{2}\boldsymbol{I}\right ]\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} S^{*}_{E}&=\epsilon _e\left [\boldsymbol{E^{*}E^{*}}-\frac {1}{2}{E^{*}}^2 \boldsymbol{I}\right ]\nonumber\\ &\quad +\epsilon _e\ell ^{2}_{c}\left [(\boldsymbol{E^{*}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }{{\nabla} ^{*}}^{2}\boldsymbol{E^{*}})\boldsymbol{I}-\boldsymbol{E^{*}}({{\nabla} ^{*}}^{2}\boldsymbol{E^{*}})-({{\nabla} ^{*}}^{2}\boldsymbol{E^{*}})\boldsymbol{E^{*}}+\frac {1}{2}({{\nabla} ^{*}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{E^{*}})^{2}\boldsymbol{I}\right ]\!. \end{align}

Here

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}^{*}=-{\nabla} ^{*} \psi ^{*}$

,

$\boldsymbol{E}^{*}=-{\nabla} ^{*} \psi ^{*}$

,

![]() $(E^{*})^2=\boldsymbol{E^{*}\boldsymbol{\cdot }E^{*}}$

and

$(E^{*})^2=\boldsymbol{E^{*}\boldsymbol{\cdot }E^{*}}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{E^{*}E^{*}}$

denotes the dyadic product. The first term represents the classical tangential electrostatic stress exerted by the field on the interfacial surface charge, while the second term arises from ion–ion correlation effects. Using (2.4), the tangential electric stress at the interface is obtained as

$\boldsymbol{E^{*}E^{*}}$

denotes the dyadic product. The first term represents the classical tangential electrostatic stress exerted by the field on the interfacial surface charge, while the second term arises from ion–ion correlation effects. Using (2.4), the tangential electric stress at the interface is obtained as

As the droplet is considered non-polarisable, i.e.

![]() $\epsilon _d \ll \epsilon _e$

, the permittivity contrast between the droplet and the electrolyte medium is negligibly small so that the internal Maxwell stress tensor,

$\epsilon _d \ll \epsilon _e$

, the permittivity contrast between the droplet and the electrolyte medium is negligibly small so that the internal Maxwell stress tensor,

![]() $\overline {S}^{*}_{\overline {E}} = \epsilon _d [ \boldsymbol{\overline {E}^{*}\,\overline {E}^{*}} - ({1}/{2}){\overline {E}^{*}}^2 \boldsymbol{I}]$

, where

$\overline {S}^{*}_{\overline {E}} = \epsilon _d [ \boldsymbol{\overline {E}^{*}\,\overline {E}^{*}} - ({1}/{2}){\overline {E}^{*}}^2 \boldsymbol{I}]$

, where

![]() $\overline {\boldsymbol{E}}^{*}$

is the internal electric field of the droplet, becomes much smaller than the external contribution and is therefore neglected in the interfacial stress balance condition. The electric force on the surface charge is governed by tangential electric field at the interface, i.e.

$\overline {\boldsymbol{E}}^{*}$

is the internal electric field of the droplet, becomes much smaller than the external contribution and is therefore neglected in the interfacial stress balance condition. The electric force on the surface charge is governed by tangential electric field at the interface, i.e.

![]() $-({1}/{a})({\partial \psi ^{*}}/{\partial \theta })$

, and the corresponding tangential force density is

$-({1}/{a})({\partial \psi ^{*}}/{\partial \theta })$

, and the corresponding tangential force density is

![]() $-\sigma ^{*}({1}/{a})({\partial \psi ^{*}}/{\partial \theta })$

, which is

$-\sigma ^{*}({1}/{a})({\partial \psi ^{*}}/{\partial \theta })$

, which is

![]() $-z_{s}e\varGamma ^{*}({1}/{a})({\partial \psi ^{*}}/{\partial \theta })$

(

$-z_{s}e\varGamma ^{*}({1}/{a})({\partial \psi ^{*}}/{\partial \theta })$

(

![]() $-z_{s}Ma\varGamma ({\partial \psi }/{\partial \theta })$

in scaled form). This implies that the second term on the right-hand side of (2.7) has to vanish at the interface, which provides the additional boundary condition at the interface to solve the MPE, i.e.

$-z_{s}Ma\varGamma ({\partial \psi }/{\partial \theta })$

in scaled form). This implies that the second term on the right-hand side of (2.7) has to vanish at the interface, which provides the additional boundary condition at the interface to solve the MPE, i.e.

and in dimensionless form

Further, with (2.8) we have at the interface

The equations of motion for the ionised incompressible Newtonian electrolyte outside the droplet can be expressed in non-dimensional form as

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}=v \boldsymbol{e}_r + u \boldsymbol{e}_\theta$

is the velocity vector,

$\boldsymbol{u}=v \boldsymbol{e}_r + u \boldsymbol{e}_\theta$

is the velocity vector,

![]() $v$

is the radial velocity component,

$v$

is the radial velocity component,

![]() $u$

is the cross-radial velocity component and

$u$

is the cross-radial velocity component and

![]() $p$

is the pressure. The above equations are obtained by scaling the dimensional variables as follows: the length scale is the radius of the sphere

$p$

is the pressure. The above equations are obtained by scaling the dimensional variables as follows: the length scale is the radius of the sphere

![]() $a$

,

$a$

,

![]() $U_0=\epsilon _e \psi _0^{2}/a\mu$

is the velocity scale, as previously mentioned,

$U_0=\epsilon _e \psi _0^{2}/a\mu$

is the velocity scale, as previously mentioned,

![]() $\tau =a/U_0$

is the time scale and

$\tau =a/U_0$

is the time scale and

![]() $\epsilon _e \psi _0^{2}/a^{2}$

is the pressure scale. If we consider the ions as finite-sized charged spheres suspended in the medium, then the viscosity of the medium must vary with the local volume fraction of ions. The variation of viscosity of the electrolyte medium with ionic volume fraction

$\epsilon _e \psi _0^{2}/a^{2}$

is the pressure scale. If we consider the ions as finite-sized charged spheres suspended in the medium, then the viscosity of the medium must vary with the local volume fraction of ions. The variation of viscosity of the electrolyte medium with ionic volume fraction

![]() $\varPhi$

is governed by the Batchelor–Green expression (Batchelor & Green Reference Batchelor and Green1972):

$\varPhi$

is governed by the Batchelor–Green expression (Batchelor & Green Reference Batchelor and Green1972):

in which

![]() $\mu _{e}$

is the viscosity of the electrolyte medium, scaled by

$\mu _{e}$

is the viscosity of the electrolyte medium, scaled by

![]() $\mu$

and

$\mu$

and

![]() $\varPhi$

is the local ionic volume fraction defined as

$\varPhi$

is the local ionic volume fraction defined as

![]() $\varPhi =\sum _{i}{Iv_{i}n_{i}}$

, where

$\varPhi =\sum _{i}{Iv_{i}n_{i}}$

, where

![]() $v_i=(4/3)\pi R^{3}_{i}$

is the volume of the

$v_i=(4/3)\pi R^{3}_{i}$

is the volume of the

![]() $i{\text{th}}$

ionic species with hydrated radius

$i{\text{th}}$

ionic species with hydrated radius

![]() $R_{i}$

. The non-dimensional equation for the flow inside the droplet is

$R_{i}$

. The non-dimensional equation for the flow inside the droplet is

where

![]() $\overline {\boldsymbol{u}}=\overline {v} \boldsymbol{e}_r +\overline { u} \boldsymbol{e}_\theta$

is the velocity vector and

$\overline {\boldsymbol{u}}=\overline {v} \boldsymbol{e}_r +\overline { u} \boldsymbol{e}_\theta$

is the velocity vector and

![]() $\overline {p}$

is the pressure inside the droplet. Ratio

$\overline {p}$

is the pressure inside the droplet. Ratio

![]() $\mu _{r}\ (=\overline {\mu }/\mu )$

is the viscosity ratio between the viscosity inside the drop and the viscosity of the outside electrolyte at infinite dilution. We assume that the droplet region is free of electrolytes, i.e. it contains no free ions, which implies

$\mu _{r}\ (=\overline {\mu }/\mu )$

is the viscosity ratio between the viscosity inside the drop and the viscosity of the outside electrolyte at infinite dilution. We assume that the droplet region is free of electrolytes, i.e. it contains no free ions, which implies

![]() $\overline {\rho }_e = 0$

. Therefore, there is no electrical body force term in (2.14). The conservation law for the

$\overline {\rho }_e = 0$

. Therefore, there is no electrical body force term in (2.14). The conservation law for the

![]() $i\text{th}$

ionic species is

$i\text{th}$

ionic species is

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{N}_{i}$

is the molar flux of the

$\boldsymbol{N}_{i}$

is the molar flux of the

![]() $i{\text{th}}$

ionic species defined as

$i{\text{th}}$

ionic species defined as

in which

![]() $\mu _{i}$

is the dimensionless electrochemical potential given by

$\mu _{i}$

is the dimensionless electrochemical potential given by

The term

![]() $\mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}$

, known as the excess electrochemical potential, accounts for short-range steric repulsion due to the finite size of ions, and its effect is characterised by the bulk ionic volume fraction,

$\mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}$

, known as the excess electrochemical potential, accounts for short-range steric repulsion due to the finite size of ions, and its effect is characterised by the bulk ionic volume fraction,

![]() $\varPhi (\infty )=\sum _{i}{v_{i}n^{\infty }_{i}}$

. When

$\varPhi (\infty )=\sum _{i}{v_{i}n^{\infty }_{i}}$

. When

![]() $\varPhi (\infty ) \sim \mathcal{O}(0.1)$

, the steric interactions significantly influence the ionic concentration distribution, thereby modifying the local charge density. This, in turn, alters the electric potential, which affects the electrostatic forces governing fluid motion, ultimately leading to changes in the velocity field. Therefore, under such conditions, the contribution of

$\varPhi (\infty ) \sim \mathcal{O}(0.1)$

, the steric interactions significantly influence the ionic concentration distribution, thereby modifying the local charge density. This, in turn, alters the electric potential, which affects the electrostatic forces governing fluid motion, ultimately leading to changes in the velocity field. Therefore, under such conditions, the contribution of

![]() $\mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}$

cannot be neglected. Based on the BMCSL equation of state (Boublík Reference Boublík1970),

$\mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}$

cannot be neglected. Based on the BMCSL equation of state (Boublík Reference Boublík1970),

![]() $\mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}$

can be expressed as

$\mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}$

can be expressed as

\begin{align} \mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i} = &-\left [1+2\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}R_{i}}{\varPhi }\right )^{3}-3\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}R_{i}}{\varPhi }\right )^{2}\right ]\ln (1-\varPhi )+\frac {3\alpha _{2}R_{i}+3\alpha _{1}R^{2}_{i}+\alpha _{0}R^{3}_{i}}{1-\varPhi }\nonumber\\ & +\frac {3\alpha _{2}R^{2}_{i}}{(1-\varPhi )^{2}}\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}}{\varPhi }+\alpha _{1}R_{i}\right )-\alpha ^{3}_{2}R^{3}_{i}\frac {\varPhi ^{2}-5\varPhi +2}{\varPhi ^{2}(1-\varPhi )^{3}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i} = &-\left [1+2\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}R_{i}}{\varPhi }\right )^{3}-3\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}R_{i}}{\varPhi }\right )^{2}\right ]\ln (1-\varPhi )+\frac {3\alpha _{2}R_{i}+3\alpha _{1}R^{2}_{i}+\alpha _{0}R^{3}_{i}}{1-\varPhi }\nonumber\\ & +\frac {3\alpha _{2}R^{2}_{i}}{(1-\varPhi )^{2}}\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}}{\varPhi }+\alpha _{1}R_{i}\right )-\alpha ^{3}_{2}R^{3}_{i}\frac {\varPhi ^{2}-5\varPhi +2}{\varPhi ^{2}(1-\varPhi )^{3}}. \end{align}

The quantity

![]() $\alpha _{k}$

is defined as

$\alpha _{k}$

is defined as

![]() $\alpha _{k}=\sum _{i}{Iv_{i}R^{k-3}_{i}n_{i}}$

. We consider the BMCSL model as it regards each ion to have a different radius, whereas the Carnahan–Starling equation of state assumes the hydrated radius of all ions as equal, taken as the average of the hydrated radii of cation and anion. The additional term

$\alpha _{k}=\sum _{i}{Iv_{i}R^{k-3}_{i}n_{i}}$

. We consider the BMCSL model as it regards each ion to have a different radius, whereas the Carnahan–Starling equation of state assumes the hydrated radius of all ions as equal, taken as the average of the hydrated radii of cation and anion. The additional term

![]() $\mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}$

in the electrochemical potential disappears when ions are treated as point charges, i.e. when

$\mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}$

in the electrochemical potential disappears when ions are treated as point charges, i.e. when

![]() $R_i=0$

. We refer to the present framework as the MEMC, which reduces to the SEM when

$R_i=0$

. We refer to the present framework as the MEMC, which reduces to the SEM when

![]() $\ell _{c}=0$

and

$\ell _{c}=0$

and

![]() $R_i=0$

. Since the viscosity of the electrolyte depends on the local ionic volume fraction, the diffusion coefficient of the

$R_i=0$

. Since the viscosity of the electrolyte depends on the local ionic volume fraction, the diffusion coefficient of the

![]() $i{\text{th}}$

ionic species,

$i{\text{th}}$

ionic species,

![]() $D_{i}$

, also varies with the local volume fraction, and is prescribed as

$D_{i}$

, also varies with the local volume fraction, and is prescribed as

In (2.17),

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}_i=\epsilon _e \psi _0^{2}/\mu D^{\infty }_i$

is the Péclet number of the

${\textit{Pe}}_i=\epsilon _e \psi _0^{2}/\mu D^{\infty }_i$

is the Péclet number of the

![]() $i{\text{th}}$

ionic species, characterising the ratio of advective to diffusion transport of ions in which

$i{\text{th}}$

ionic species, characterising the ratio of advective to diffusion transport of ions in which

![]() $D^{\infty }_i$

is the diffusion coefficient of the

$D^{\infty }_i$

is the diffusion coefficient of the

![]() $i{\text{th}}$

ion at infinite dilution. The boundary conditions for the velocity field and ion concentration at the droplet surface (

$i{\text{th}}$

ion at infinite dilution. The boundary conditions for the velocity field and ion concentration at the droplet surface (

![]() $r=1$

) are the continuity of tangential velocity, assuming no molecular slip, as well as fluid and ion impermeability conditions, i.e.

$r=1$

) are the continuity of tangential velocity, assuming no molecular slip, as well as fluid and ion impermeability conditions, i.e.

The stress balance condition is crucial in droplet electrophoresis and is significantly influenced by the presence of ionic surfactants at the interface. The tangential stress balance condition is given as (Slattery, Sagis & Oh Reference Slattery, Sagis and Oh2007; Manikantan & Squires Reference Manikantan and Squires2020)

where

![]() $S^{*}_{H}$

is the hydrodynamic stress, i.e.

$S^{*}_{H}$

is the hydrodynamic stress, i.e.

![]() $S^{*}_{H}=-p^{*}\boldsymbol{I}+\mu ^{*}_{e}[{\nabla} ^{*} \boldsymbol{u}^{*} + ({\nabla} ^{*} \boldsymbol{u}^{*})^T]$

,

$S^{*}_{H}=-p^{*}\boldsymbol{I}+\mu ^{*}_{e}[{\nabla} ^{*} \boldsymbol{u}^{*} + ({\nabla} ^{*} \boldsymbol{u}^{*})^T]$

,

![]() $\gamma ^{*}$

represents the surface tension and

$\gamma ^{*}$

represents the surface tension and

![]() ${\nabla} ^{*}_{s}=(\boldsymbol{I}-\boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{n})\boldsymbol{\cdot }{\nabla} ^{*}$

is the gradient along the surface. Here, the surface gradient of

${\nabla} ^{*}_{s}=(\boldsymbol{I}-\boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{n})\boldsymbol{\cdot }{\nabla} ^{*}$

is the gradient along the surface. Here, the surface gradient of

![]() $\gamma ^*$

contains the tangential Maxwell stress as explained in the following. According to the Gibbs adsorption isotherm,

$\gamma ^*$

contains the tangential Maxwell stress as explained in the following. According to the Gibbs adsorption isotherm,

where

![]() $\varPi ^*$

is the surface pressure due to adsorption of components

$\varPi ^*$

is the surface pressure due to adsorption of components

![]() $i$

at the interface with interface concentrations

$i$

at the interface with interface concentrations

![]() $\varGamma ^{*}_{i}$

and

$\varGamma ^{*}_{i}$

and

![]() $\mu ^*_{s,i}$

is the electrochemical potential at the interface due to the surfactant concentration. Assuming a single surfactant species characterised by a Langmuir isotherm, the electrochemical potential of the surfactant is (Manikantan & Squires Reference Manikantan and Squires2020)

$\mu ^*_{s,i}$

is the electrochemical potential at the interface due to the surfactant concentration. Assuming a single surfactant species characterised by a Langmuir isotherm, the electrochemical potential of the surfactant is (Manikantan & Squires Reference Manikantan and Squires2020)

Substituting in (2.23) and simplifying yields

Substituting (2.25) into the tangential stress balance condition (2.22), we obtain

The final term of the above equation can be expressed as

![]() $z_{s}e\varGamma ^{*}{\nabla} ^{*}_{s}\psi ^{*}_{s}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{t}=-\boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{\cdot }S^{*}_{E}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{t}$

from (2.10). The tangential stress balance condition, arising through the balance of electric, hydrodynamic and Marangoni stresses (Baygents & Saville Reference Baygents and Saville1991; Vlahovska Reference Vlahovska2019), can thus be recast as

$z_{s}e\varGamma ^{*}{\nabla} ^{*}_{s}\psi ^{*}_{s}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{t}=-\boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{\cdot }S^{*}_{E}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{t}$

from (2.10). The tangential stress balance condition, arising through the balance of electric, hydrodynamic and Marangoni stresses (Baygents & Saville Reference Baygents and Saville1991; Vlahovska Reference Vlahovska2019), can thus be recast as

It may be noted that the contribution to the Maxwell stress from the interior of the droplet can be neglected as

![]() $\epsilon _d \ll \epsilon _e$

. Upon applying the necessary substitutions, non-dimensionalising and performing algebraic simplifications, (2.27) reduces to

$\epsilon _d \ll \epsilon _e$

. Upon applying the necessary substitutions, non-dimensionalising and performing algebraic simplifications, (2.27) reduces to

The left-hand side of (2.28) represents the hydrodynamic stress jump across the interface and the first term on the right-hand side accounts for the tangential Maxwell stress. The last term in (2.28) arises due to the surface pressure of the surfactant present at the interface of the droplet.

Throughout this study, we assume that the droplet retains a spherical shape under the influence of an applied electric field

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}^{\infty }$

. This assumption is justified in the weak-field regime, characterised by the dimensionless parameter

$\boldsymbol{E}^{\infty }$

. This assumption is justified in the weak-field regime, characterised by the dimensionless parameter

![]() $ \varLambda = aeE^{\infty }/k_B T \ll 1$

. As shown in classical works by Taylor (Reference Taylor1964), Torza, Cox & Mason (Reference Torza, Cox and Mason1971) and Baygents & Saville (Reference Baygents and Saville1991), deformation of the droplet surface arises only at

$ \varLambda = aeE^{\infty }/k_B T \ll 1$

. As shown in classical works by Taylor (Reference Taylor1964), Torza, Cox & Mason (Reference Torza, Cox and Mason1971) and Baygents & Saville (Reference Baygents and Saville1991), deformation of the droplet surface arises only at

![]() $\mathcal{O}(\varLambda ^2)$

, which corresponds to the electric capillary number

$\mathcal{O}(\varLambda ^2)$

, which corresponds to the electric capillary number

![]() $Ca_E = \epsilon _e {E^{\infty }}^2 a/\gamma ^{*}$

(Vlahovska Reference Vlahovska2019). In the weak-field limit,

$Ca_E = \epsilon _e {E^{\infty }}^2 a/\gamma ^{*}$

(Vlahovska Reference Vlahovska2019). In the weak-field limit,

![]() $Ca_E \ll 1$

, indicating that electric stresses are negligible compared with surface tension, and the droplet shape remains spherical. Since our analysis is carried out up to

$Ca_E \ll 1$

, indicating that electric stresses are negligible compared with surface tension, and the droplet shape remains spherical. Since our analysis is carried out up to

![]() $\mathcal{O}(\varLambda )$

, shape deformations are beyond the leading-order accuracy and are thus neglected. To illustrate, consider a typical oil droplet of radius

$\mathcal{O}(\varLambda )$

, shape deformations are beyond the leading-order accuracy and are thus neglected. To illustrate, consider a typical oil droplet of radius

![]() $a = 100\,\textrm{nm}$

in water with interfacial tension

$a = 100\,\textrm{nm}$

in water with interfacial tension

![]() $\gamma ^{*} \approx 10^{-2}\,\text{N m}^{-1}$

, subject to an electric field

$\gamma ^{*} \approx 10^{-2}\,\text{N m}^{-1}$

, subject to an electric field

![]() $E^{\infty } = 10^4\,\text{V m}^{-1}$

, and with water permittivity

$E^{\infty } = 10^4\,\text{V m}^{-1}$

, and with water permittivity

![]() $\epsilon _e= 7.0832 \times 10^{-10}\,\text{F m}^{-1}$

. The electric capillary number evaluates to

$\epsilon _e= 7.0832 \times 10^{-10}\,\text{F m}^{-1}$

. The electric capillary number evaluates to

![]() $Ca_E=7.0832 \times 10^{-7} \ll 1$

, confirming that droplet deformation is negligible for realistic field strengths in our regime of interest.

$Ca_E=7.0832 \times 10^{-7} \ll 1$

, confirming that droplet deformation is negligible for realistic field strengths in our regime of interest.

Moreover, the variation of surface tension on the drop due to mobile surfactants influences the pressure jump across the interface. With the Young–Laplace equation an estimate for the relative change in the radius of curvature due to these surface tension variations is

![]() $\Delta a/a \sim \Delta \gamma ^{*} / \gamma ^{*} \sim kT\Delta \varGamma ^* / \gamma ^{*}$

for not too large surface coverage. In this study, we have considered

$\Delta a/a \sim \Delta \gamma ^{*} / \gamma ^{*} \sim kT\Delta \varGamma ^* / \gamma ^{*}$

for not too large surface coverage. In this study, we have considered

![]() $\varGamma ^{\infty }$

up to

$\varGamma ^{\infty }$

up to

![]() $2\,\textrm{nm}^{-2}$

and use the leading-order form

$2\,\textrm{nm}^{-2}$

and use the leading-order form

![]() $\Delta \varGamma ^* \sim \varDelta _s\varGamma ^{\infty }\varLambda \cos \theta$

to estimate surface concentration variations (discussed in a later section). Numerical results across the entire parameter space considered in the study reveal that the dimensionless coefficient

$\Delta \varGamma ^* \sim \varDelta _s\varGamma ^{\infty }\varLambda \cos \theta$

to estimate surface concentration variations (discussed in a later section). Numerical results across the entire parameter space considered in the study reveal that the dimensionless coefficient

![]() $\varDelta _s=\mathcal{O}(10^{-2})$

. Consequently, the maximum variation in surface concentration is bounded by

$\varDelta _s=\mathcal{O}(10^{-2})$

. Consequently, the maximum variation in surface concentration is bounded by

![]() $ |\Delta \varGamma ^*|_{\textit{max}} \leqslant 2 \times \mathcal{O}(10^{16}) \varLambda \,\textrm m^{-2}$

. Invoking the thermodynamic estimate

$ |\Delta \varGamma ^*|_{\textit{max}} \leqslant 2 \times \mathcal{O}(10^{16}) \varLambda \,\textrm m^{-2}$

. Invoking the thermodynamic estimate

![]() $ \Delta \gamma \sim k_B T \varDelta \varGamma ^*$

together with

$ \Delta \gamma \sim k_B T \varDelta \varGamma ^*$

together with

![]() $ k_B T / \gamma ^{*} \approx 4.1 \times 10^{-19}\,\textrm{m}^2$

, where

$ k_B T / \gamma ^{*} \approx 4.1 \times 10^{-19}\,\textrm{m}^2$

, where

![]() $k_{B}=1.381\times 10^{-23}$

,

$k_{B}=1.381\times 10^{-23}$

,

![]() $T=298\,\textrm K$

and

$T=298\,\textrm K$

and

![]() $\gamma ^{*} \approx 10^{-2}\,\text{N m}^{-1}$

, the resulting upper bound on curvature variation becomes

$\gamma ^{*} \approx 10^{-2}\,\text{N m}^{-1}$

, the resulting upper bound on curvature variation becomes

![]() $\left |{\Delta a}/{a} \right |_{{max}} \sim 8.2 \times \mathcal{O}(10^{-3}) \varLambda$

. For a representative case involving a droplet of radius

$\left |{\Delta a}/{a} \right |_{{max}} \sim 8.2 \times \mathcal{O}(10^{-3}) \varLambda$

. For a representative case involving a droplet of radius

![]() $ a = 100\,\textrm{nm}$

subjected to an external electric field of

$ a = 100\,\textrm{nm}$

subjected to an external electric field of

![]() $ E^{\infty } = 10^4\,\textrm{V m}^{-1}$

, we find

$ E^{\infty } = 10^4\,\textrm{V m}^{-1}$

, we find

![]() $ \varLambda = 0.039$

, yielding

$ \varLambda = 0.039$

, yielding

![]() $ |\varDelta a/a|_{{max}} \sim 0.3 \times \mathcal{O}(10^{-3})$

. This corresponds to a relative curvature change below

$ |\varDelta a/a|_{{max}} \sim 0.3 \times \mathcal{O}(10^{-3})$

. This corresponds to a relative curvature change below

![]() $ 0.3\,\%$

, even at maximal surface coverage. We thus conclude that curvature variation of the droplet, induced by surfactant-driven surface tension inhomogeneity, remains negligible throughout the parameter regime considered.

$ 0.3\,\%$

, even at maximal surface coverage. We thus conclude that curvature variation of the droplet, induced by surfactant-driven surface tension inhomogeneity, remains negligible throughout the parameter regime considered.

In light of the negligible deformation discussed above, we do not explicitly impose the normal component of the interfacial stress balance as a boundary condition. This is a deliberate and justified modelling choice in the absence of deformation; the role of the normal stress condition is to maintain the droplet shape, not to determine interfacial velocities or mobility. Instead of the normal stress balance, the impermeability condition is taken as a boundary condition (Baygents & Saville Reference Baygents and Saville1991; Schnitzer et al. Reference Schnitzer, Frankel and Yariv2014; Yang, Shin & Stone Reference Yang, Shin and Stone2018), as given in the second equation of (2.21). We note, however, that in systems with high electric field strengths, deformation effects may become non-negligible. These regimes lie beyond the scope of the current study and represent promising directions for future work.

Now to find the surfactant concentration, we use the mass balance principle at the interface, which for an insoluble surfactant is simply

where the interface flux

![]() $\boldsymbol{J}^{*}_{s}$

of surfactants can be written as

$\boldsymbol{J}^{*}_{s}$

of surfactants can be written as

Substituting

![]() $\mu ^{*}_{s}$

from (2.24), we get the general expression of

$\mu ^{*}_{s}$

from (2.24), we get the general expression of

![]() $\boldsymbol{J}^{*}_{s}$

as

$\boldsymbol{J}^{*}_{s}$

as

Substituting

![]() $\boldsymbol{J}^{*}_{s}$

into (2.29) and non-dimensionalising it, we get

$\boldsymbol{J}^{*}_{s}$

into (2.29) and non-dimensionalising it, we get

where

![]() $\varGamma =\varGamma ^*/\varGamma ^\infty$

and

$\varGamma =\varGamma ^*/\varGamma ^\infty$

and

![]() ${\textit{Pe}}_s=U_0 a/D_s$

.

${\textit{Pe}}_s=U_0 a/D_s$

.

A frame of reference is considered in which the droplet is stationary and the fluid moves with the far flow field approaching the droplet with a speed

![]() $-U_E$

. To ensure electroneutrality, the ionic concentration must equal its bulk value in the far field. Thus, the boundary conditions far from the droplet

$-U_E$

. To ensure electroneutrality, the ionic concentration must equal its bulk value in the far field. Thus, the boundary conditions far from the droplet

![]() $(r\to \infty )$

are

$(r\to \infty )$

are

where

![]() $\varLambda ={E^{\infty }a}/{\psi _{0}}$

is the scaled externally imposed electric field and

$\varLambda ={E^{\infty }a}/{\psi _{0}}$

is the scaled externally imposed electric field and

![]() $\mu _{E}$

is the electrophoretic mobility. The electrophoretic mobility is defined as the electrophoretic velocity per unit externally imposed electric field, i.e.

$\mu _{E}$

is the electrophoretic mobility. The electrophoretic mobility is defined as the electrophoretic velocity per unit externally imposed electric field, i.e.

![]() $\mu _{E}=U_{E}/\varLambda$

(Stout & Khair Reference Stout and Khair2017).

$\mu _{E}=U_{E}/\varLambda$

(Stout & Khair Reference Stout and Khair2017).

Note that both the tangential stress balance (2.27) and the interfacial surfactant balance (2.32) depend on the chosen surfactant isotherm, derived from a suitable free energy required to assemble the surfactant layer. Here, we have focused on the Langmuir isotherm, originating from a lattice gas model for the surfactant molecules. At large surface coverage attractive interactions between bound surfactant molecules frequently play a role, such that the Langmuir isotherm, which only takes steric interactions into account, is often replaced by Frumkin or van der Waals isotherms in modelling particular surfactants (Lyklema Reference Lyklema2000; Prosser & Franses Reference Prosser and Franses2001; Manikantan & Squires Reference Manikantan and Squires2020), but also these will only describe the interface tension within a limited range of surfactant coverage. Since in the following we consider low applied electric fields, allowing a linearised analysis, only the Marangoni dilational modulus

![]() $-\varGamma (\partial \gamma /\partial \varGamma )$

evaluated at the mean interface concentration

$-\varGamma (\partial \gamma /\partial \varGamma )$

evaluated at the mean interface concentration

![]() $\varGamma ^0$

is relevant (Manikantan & Squires Reference Manikantan and Squires2020). The Langmuir isotherm thus allows a transparent way to adjust the Marangoni modulus by prescribing an average and maximal surface coverage without the need to introduce additional phenomenological parameters in the present analysis.

$\varGamma ^0$

is relevant (Manikantan & Squires Reference Manikantan and Squires2020). The Langmuir isotherm thus allows a transparent way to adjust the Marangoni modulus by prescribing an average and maximal surface coverage without the need to introduce additional phenomenological parameters in the present analysis.

We have limited our present investigation to insoluble surfactants. In general (2.29) would include fluxes describing surfactant adsorption from and desorption to the surrounding liquid phases. In the present study, we assume that the exchange rates are so small that on the time scale of the experiment no significant exchange with the liquid phase takes place (Levich Reference Levich1962; Lyklema Reference Lyklema2000; Manikantan & Squires Reference Manikantan and Squires2020). It may be noted that insoluble ionic surfactants are particularly well documented at water–air interfaces (Lyklema Reference Lyklema2000) and that the model employed here is applicable for gas bubbles in the limit of small internal viscosity,

![]() $\mu _r \ll 1$

. As mentioned before, the exchange of surfactants at the droplet interface with the liquid phase is taken into account in the context of droplet electrophoresis by Hill (Reference Hill2025) based on the SEM for monovalent electrolytes and Ohshima (Reference Ohshima2025a

) by considering an instantaneous equilibrium between interface and fluid phase.

$\mu _r \ll 1$

. As mentioned before, the exchange of surfactants at the droplet interface with the liquid phase is taken into account in the context of droplet electrophoresis by Hill (Reference Hill2025) based on the SEM for monovalent electrolytes and Ohshima (Reference Ohshima2025a

) by considering an instantaneous equilibrium between interface and fluid phase.

3. Governing equations for a weak imposed field

Most of the experimental studies reported in the literature considered an externally applied electric field up to

![]() $10^{4}\,\textrm{V m}^{-1}$

, which corresponds to

$10^{4}\,\textrm{V m}^{-1}$

, which corresponds to

![]() $\varLambda =0.039$

for a

$\varLambda =0.039$

for a

![]() $100\,\textrm{nm}$

particle. Tottori et al. (Reference Tottori, Misiunas, Keyser and Bonthuis2019) conducted their experiment for a non-polarisable particle with an applied electric field

$100\,\textrm{nm}$

particle. Tottori et al. (Reference Tottori, Misiunas, Keyser and Bonthuis2019) conducted their experiment for a non-polarisable particle with an applied electric field

![]() $E^{\infty }=25 \,\textrm{V cm}^{-1}$

which gives

$E^{\infty }=25 \,\textrm{V cm}^{-1}$

which gives

![]() $\varLambda =9.7\times 10^{-3}$

for

$\varLambda =9.7\times 10^{-3}$

for

![]() $a=100\,\textrm{nm}$

. For

$a=100\,\textrm{nm}$

. For

![]() $\varLambda$

this small, terms higher than linear in

$\varLambda$

this small, terms higher than linear in

![]() $\varLambda$

have no significant impact on the mobility of the droplet. Consequently, the perturbation method is appropriate for solving the governing equations with the applied electric field

$\varLambda$

have no significant impact on the mobility of the droplet. Consequently, the perturbation method is appropriate for solving the governing equations with the applied electric field

![]() $(\varLambda )$

as the perturbation parameter. Under such weak-field consideration, the variables can be expressed as a linear perturbation from their equilibrium, as

$(\varLambda )$

as the perturbation parameter. Under such weak-field consideration, the variables can be expressed as a linear perturbation from their equilibrium, as

![]() $\psi =\psi ^{0}(r)+\delta \psi (r,\theta )$

,

$\psi =\psi ^{0}(r)+\delta \psi (r,\theta )$

,

![]() $n_{i}=n^{0}_{i}(r)+\delta n_{i}(r,\theta )$

,

$n_{i}=n^{0}_{i}(r)+\delta n_{i}(r,\theta )$

,

![]() $\mu _{i}=\mu ^{0}_{i}+\delta \mu _{i}(r,\theta )$

,

$\mu _{i}=\mu ^{0}_{i}+\delta \mu _{i}(r,\theta )$

,

![]() $\mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}=\mu ^{{\textit{ex}},0}_{i}+\delta \mu ^{{\textit{ex}}}_{i}(r,\theta )$

and

$\mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}=\mu ^{{\textit{ex}},0}_{i}+\delta \mu ^{{\textit{ex}}}_{i}(r,\theta )$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}=\boldsymbol{0}+\delta \boldsymbol{u}(r,\theta )$

, where the quantities with the superscript

$\boldsymbol{u}=\boldsymbol{0}+\delta \boldsymbol{u}(r,\theta )$

, where the quantities with the superscript

![]() $0$

refer to those at equilibrium and variables with prefix

$0$

refer to those at equilibrium and variables with prefix

![]() $\delta$

are the perturbation from their equilibrium values under the influence of the external electric field. The surfactant concentration and the surface charge density are also perturbed with respect to the imposed electric field and can be written as

$\delta$

are the perturbation from their equilibrium values under the influence of the external electric field. The surfactant concentration and the surface charge density are also perturbed with respect to the imposed electric field and can be written as

![]() $\varGamma =\varGamma ^{0}+\delta \varGamma (\theta )$

and

$\varGamma =\varGamma ^{0}+\delta \varGamma (\theta )$

and

![]() $\sigma =\sigma ^{0}+\delta \sigma (\theta )$

. As

$\sigma =\sigma ^{0}+\delta \sigma (\theta )$

. As

![]() $\sigma =z_{s}Ma\varGamma$

, hence

$\sigma =z_{s}Ma\varGamma$

, hence

![]() $\sigma ^{0}=z_{s}Ma\varGamma ^{0} \text{ and }\delta \sigma (\theta )=z_{s}Ma\delta \varGamma (\theta )$

.

$\sigma ^{0}=z_{s}Ma\varGamma ^{0} \text{ and }\delta \sigma (\theta )=z_{s}Ma\delta \varGamma (\theta )$

.

3.1. The equilibrium structure of the EDL

The equilibrium state refers to the situation before applying any external electric field, i.e.

![]() $\varLambda =0$

. In this situation, the ion velocities as well the fluid velocity vanish, which implies that the electrochemical potential gradient must be zero. This gives

$\varLambda =0$

. In this situation, the ion velocities as well the fluid velocity vanish, which implies that the electrochemical potential gradient must be zero. This gives

\begin{equation} z_{i}\frac {{\textrm d}\psi ^{0}(r)}{{\textrm d}r}+\frac {1}{n^{0}_{i}(r)}\frac {{\textrm d}n^{0}_{i}(r)}{{\textrm d}r}+\frac {{\textrm d}\mu ^{\textit{ex},0}_{i}(r)}{{\textrm d}r}=0. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} z_{i}\frac {{\textrm d}\psi ^{0}(r)}{{\textrm d}r}+\frac {1}{n^{0}_{i}(r)}\frac {{\textrm d}n^{0}_{i}(r)}{{\textrm d}r}+\frac {{\textrm d}\mu ^{\textit{ex},0}_{i}(r)}{{\textrm d}r}=0. \end{equation}

Upon integration to the far field, (3.1) gives

Equation (3.2) is obtained with the condition that the equilibrium potential vanishes at the far field. Here,

![]() $\mu ^{\textit{ex},0}_{i}(\infty )$

is the excess electrochemical potential of the

$\mu ^{\textit{ex},0}_{i}(\infty )$

is the excess electrochemical potential of the

![]() $i{\text{th}}$

ionic species at the far field in the absence of applied electric field and is given by

$i{\text{th}}$

ionic species at the far field in the absence of applied electric field and is given by

\begin{align} \mu ^{\textit{ex},0}_{i}( \infty ) = &-\left [1+2\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}( \infty )R_{i}}{\varPhi ( \infty )}\right )^{3}-3\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}( \infty )R_{i}}{\varPhi ( \infty )}\right )^{2}\right ]\ln (1-\varPhi ( \infty ))\nonumber\\ &+\frac {3\alpha _{2}( \infty )R_{i}+3\alpha _{1}( \infty )R^{2}_{i}+\alpha _{0}( \infty )R^{3}_{i}}{1-\varPhi ( \infty )}\nonumber\\ &+\frac {3\alpha _{2}( \infty )R^{2}_{i}}{(1-\varPhi ( \infty ))^{2}}\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}( \infty )}{\varPhi ( \infty )}+\alpha _{1}( \infty )R_{i}\right )\nonumber\\ &-\alpha ^{3}_{2}( \infty )R^{3}_{i}\frac {\varPhi ^{2}( \infty )-5\varPhi ( \infty )+2}{\varPhi ^{2}( \infty )(1-\varPhi ( \infty ))^{3}}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \mu ^{\textit{ex},0}_{i}( \infty ) = &-\left [1+2\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}( \infty )R_{i}}{\varPhi ( \infty )}\right )^{3}-3\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}( \infty )R_{i}}{\varPhi ( \infty )}\right )^{2}\right ]\ln (1-\varPhi ( \infty ))\nonumber\\ &+\frac {3\alpha _{2}( \infty )R_{i}+3\alpha _{1}( \infty )R^{2}_{i}+\alpha _{0}( \infty )R^{3}_{i}}{1-\varPhi ( \infty )}\nonumber\\ &+\frac {3\alpha _{2}( \infty )R^{2}_{i}}{(1-\varPhi ( \infty ))^{2}}\left (\frac {\alpha _{2}( \infty )}{\varPhi ( \infty )}+\alpha _{1}( \infty )R_{i}\right )\nonumber\\ &-\alpha ^{3}_{2}( \infty )R^{3}_{i}\frac {\varPhi ^{2}( \infty )-5\varPhi ( \infty )+2}{\varPhi ^{2}( \infty )(1-\varPhi ( \infty ))^{3}}, \end{align}

where

![]() $\varPhi (\infty )=\sum _{i}{v_{i}n^{\infty }_{i}}$

and

$\varPhi (\infty )=\sum _{i}{v_{i}n^{\infty }_{i}}$

and

![]() $\alpha _{k}(\infty )=\sum _{i}{v_{i}R^{k-3}_{i}n^{\infty }_{i}}$

. Applying (3.2) in the MPE (2.2) and introducing

$\alpha _{k}(\infty )=\sum _{i}{v_{i}R^{k-3}_{i}n^{\infty }_{i}}$

. Applying (3.2) in the MPE (2.2) and introducing

![]() $\xi ={{\nabla}^{2}}\psi$

, the equilibrium potential outside the droplet is governed by

$\xi ={{\nabla}^{2}}\psi$

, the equilibrium potential outside the droplet is governed by

\begin{align} \xi ^{0}(r)-\frac {\delta ^{2}_{c}}{(\kappa a)^{2}}\left [\frac {{\textrm d}^{2}\xi ^{0}(r)}{{\textrm d}r^{2}}+\frac {2}{r}\frac {{\textrm d}\xi ^{0}(r)}{{\textrm d}r}\right ]&=-\frac {(\kappa a)^2}{2}\sum _{i=1}^{N}z_{i}n^{0}_{i}(r), \end{align}

\begin{align} \xi ^{0}(r)-\frac {\delta ^{2}_{c}}{(\kappa a)^{2}}\left [\frac {{\textrm d}^{2}\xi ^{0}(r)}{{\textrm d}r^{2}}+\frac {2}{r}\frac {{\textrm d}\xi ^{0}(r)}{{\textrm d}r}\right ]&=-\frac {(\kappa a)^2}{2}\sum _{i=1}^{N}z_{i}n^{0}_{i}(r), \end{align}

with the boundary conditions

The equilibrium profiles for electrostatic potential

![]() $\psi ^{0}(r)$

and ionic concentration

$\psi ^{0}(r)$

and ionic concentration

![]() $n^{0}_{i}(r)$

can be obtained by solving (3.2) and (3.4) subject to the boundary conditions (3.5) in a coupled manner. Note that there is no relative osmotic flow in the equilibrium situation, i.e.

$n^{0}_{i}(r)$

can be obtained by solving (3.2) and (3.4) subject to the boundary conditions (3.5) in a coupled manner. Note that there is no relative osmotic flow in the equilibrium situation, i.e.

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}^{0}=\boldsymbol{0}$

.

$\boldsymbol{u}^{0}=\boldsymbol{0}$

.

3.2. Non-equilibrium effect due to imposed electric field

The perturbed MPE and modified Nernst–Planck equation for the

![]() $i{\text{th}}$

ionic species are obtained from (2.2), (2.16) as

$i{\text{th}}$

ionic species are obtained from (2.2), (2.16) as

\begin{align}\delta \xi (r,\theta )-\frac {\delta ^{2}_{c}}{(\kappa a)^{2}}{\nabla}^{2}\delta \xi (r,\theta ) = -\frac {(\kappa a)^2}{2}\sum _{i=1}^{N}z_{i}\delta {n_{i}}(r,\theta ),\end{align}

\begin{align}\delta \xi (r,\theta )-\frac {\delta ^{2}_{c}}{(\kappa a)^{2}}{\nabla}^{2}\delta \xi (r,\theta ) = -\frac {(\kappa a)^2}{2}\sum _{i=1}^{N}z_{i}\delta {n_{i}}(r,\theta ),\end{align}

The spherical symmetry of the problem allows us to express the perturbed quantities as (Ohshima, Healy & White Reference Ohshima, Healy and White1983)

The perturbed ionic concentration

![]() $\delta {n_{i}}(r,\theta )$

of the

$\delta {n_{i}}(r,\theta )$

of the

![]() $i{\text{th}}$

ionic species can be expressed in terms of other variables as

$i{\text{th}}$

ionic species can be expressed in terms of other variables as

The inclusion of the perturbed excess electrochemical term

![]() $\delta \mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}(r,\theta )$

in (3.8) introduces a dependence of

$\delta \mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}(r,\theta )$

in (3.8) introduces a dependence of

![]() $\delta n_{i}(r,\theta )$

and, hence, (3.8) becomes an implicit equation for

$\delta n_{i}(r,\theta )$

and, hence, (3.8) becomes an implicit equation for

![]() $\delta n_{i}(r,\theta )$

. Such type of complexity is absent in previous studies (e.g. Baygents & Saville Reference Baygents and Saville1991; Hill Reference Hill2020; Uematsu & Ohshima Reference Uematsu and Ohshima2022; Hill Reference Hill2025) where the ion steric effect is not taken into consideration. Based on a first-order perturbation analysis,

$\delta n_{i}(r,\theta )$

. Such type of complexity is absent in previous studies (e.g. Baygents & Saville Reference Baygents and Saville1991; Hill Reference Hill2020; Uematsu & Ohshima Reference Uematsu and Ohshima2022; Hill Reference Hill2025) where the ion steric effect is not taken into consideration. Based on a first-order perturbation analysis,

![]() $\delta \mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}(r,\theta )$

can be expressed in terms of

$\delta \mu ^{\textit{ex}}_{i}(r,\theta )$

can be expressed in terms of

![]() $\delta n_{i}(r,\theta )$

. For a general electrolyte

$\delta n_{i}(r,\theta )$

. For a general electrolyte

![]() $z_{1}:z_{2}$

,

$z_{1}:z_{2}$

,

![]() $\delta n_{i}(r,\theta )$

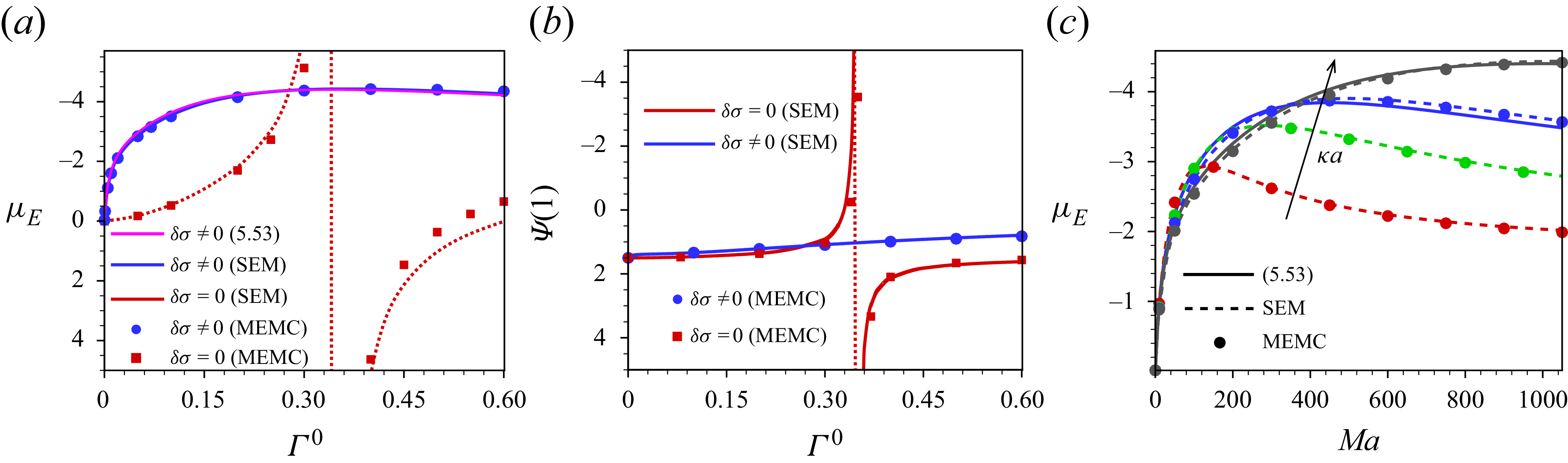

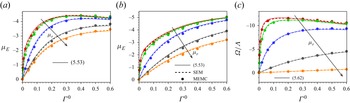

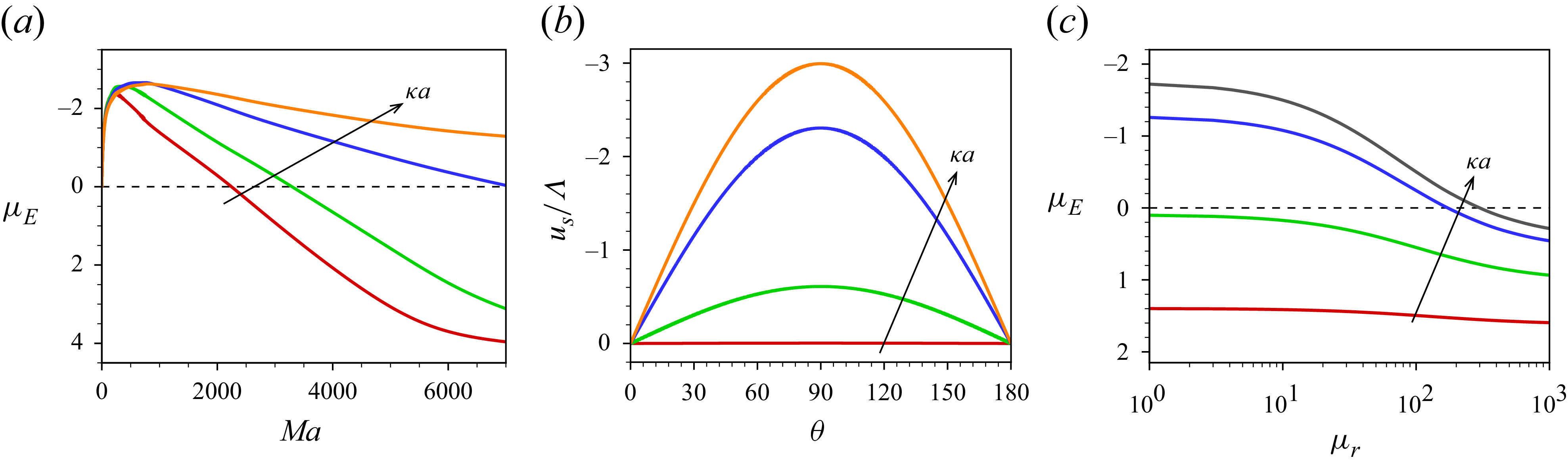

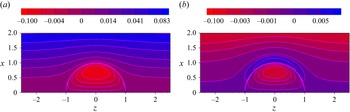

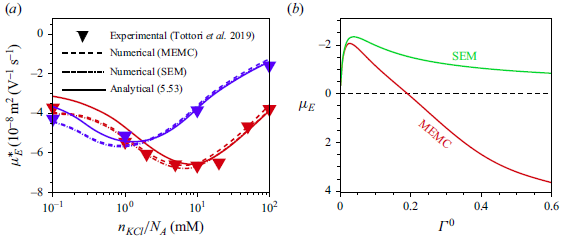

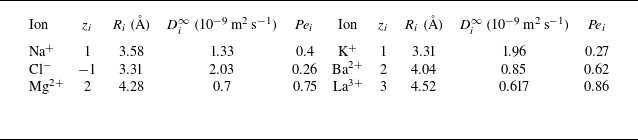

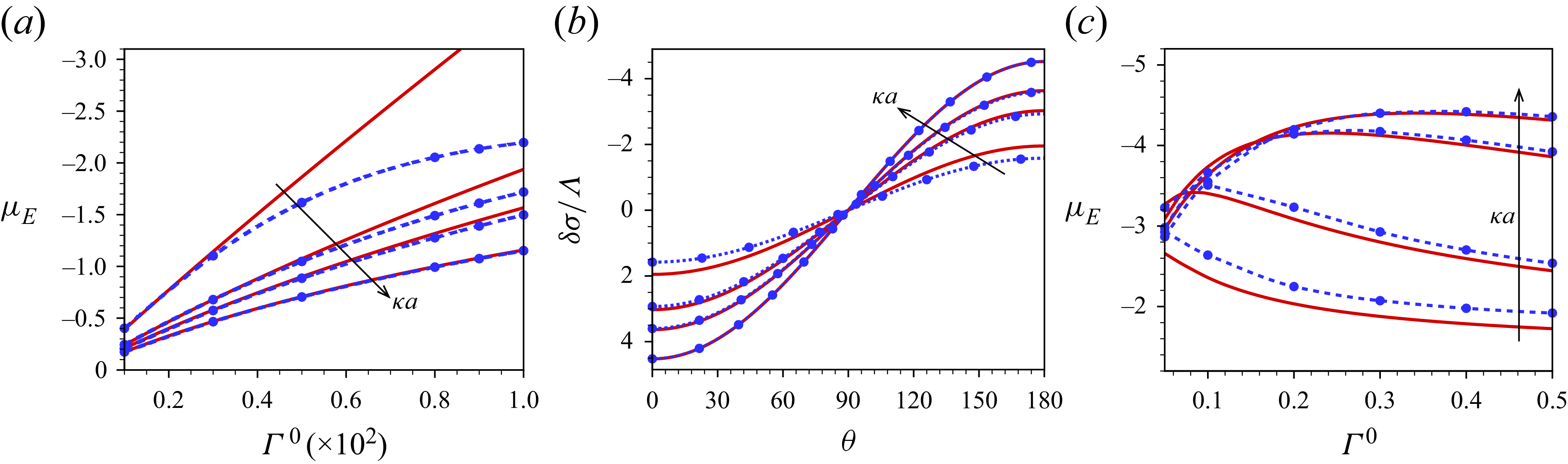

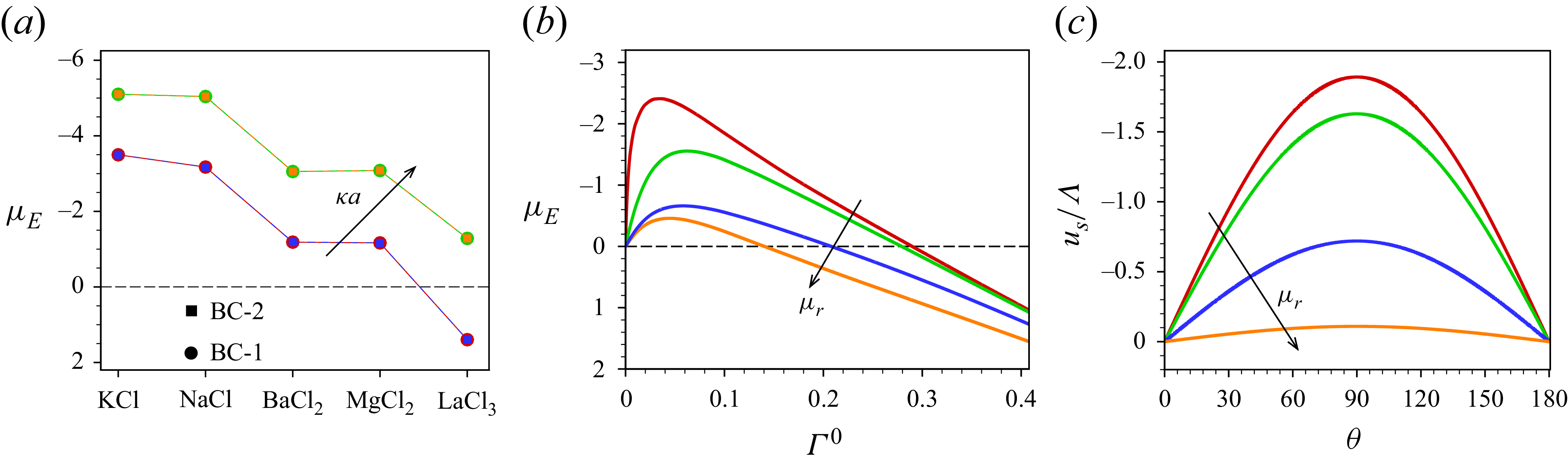

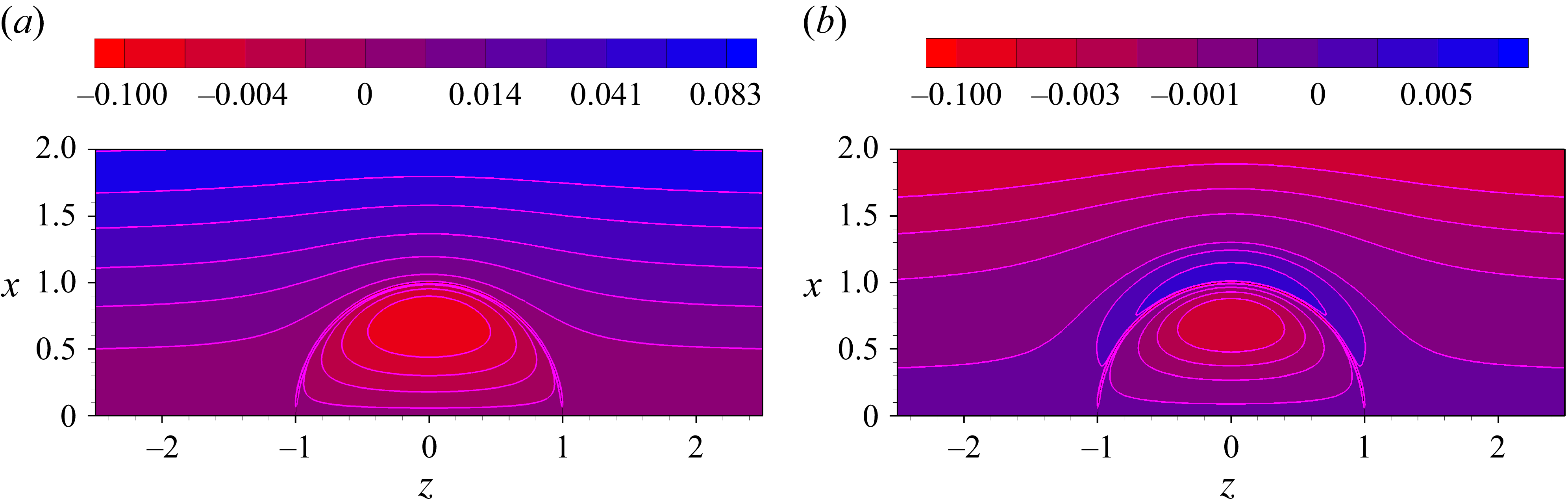

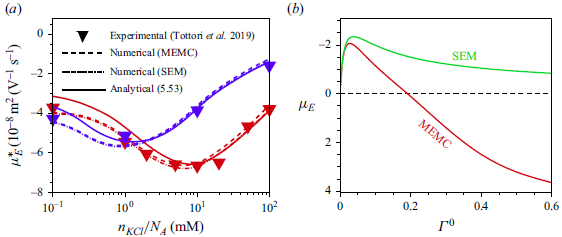

can be expressed in terms of