Introduction

In March 2023, the federal government’s Treasury Board Secretariat announced that it had uncovered evidence of discrimination and systemic racism within the Canadian Human Rights Commission (Association of Justice Counsel 2023; Thurton Reference Thurton2023). This remarkable finding led to an investigation by the Senate Standing Committee on Human Rights. The hearings went beyond concerns around anti-Black racism within the commission to considering the challenges facing the entire human rights legal regime in Canada. As Senator David Arnot (former Chair of the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission) noted during the hearings, there was a backlog of more than 9,000 human rights cases in Ontario, while, in British Columbia, it could take four to seven years to reach a hearing. Claimants faced delays from two years in Manitoba to, not long ago, as long as six years in Alberta to reach a mediation hearing (Ataullahjan and Bernard Reference Ataullahjan and Bernard2023). In British Columbia, as recently as 2021–22, the Human Rights Tribunal, which was designed to handle approximately 1,100 cases per year, received 3,192 new cases (British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal 2021–22, 4).

Every federal, provincial and territorial jurisdiction in Canada has a human rights statute enforced by a state agency. It is among the most robust and accessible human rights legal regimes in the world (Cardenas Reference Cardenas2014; Langtry and Lyer Reference Langtry and Lyer2021). Although these statutes are primarily equality or anti-discrimination laws, they represent a profound commitment to codifying international human principles. Yet Canadian human rights institutions (HRIs) face immense challenges, notably a lack of funding, delays and a growing backlog of cases. Delays are especially concerning—HRIs were intended to adjudicate claims faster than the courts (Howe and Johnson Reference Howe and Johnson2000; Clément Reference Clément2017). Mediation, in particular, has become a common strategy among HRIs to address delays and backlogs in Canada (Leslie Reference Leslie, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014; Goss Reference Goss1995). Mediation has become widespread in civil and family law as well as restorative justice (Goss Reference Goss1995; Cappelletti Reference Cappelletti1993; Menkel-Meadow Reference Menkel-Meadow2007).

Despite an increasing reliance on mediation, delays continue to undermine confidence in human rights law. Additionally, delays can engender anger and frustration among claimants (Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014; Howe and Johnson Reference Howe and Johnson2000). To address these challenges, legislators in British Columbia and Ontario have experimented with a direct-access system. This reform enables claimants to bring their case directly to an administrative tribunal without having to first have their case reviewed by a human rights commission (although tribunals also offer mediation as an option). Yet many continue to feel unsupported or denied access in the direct-access systems (Parmar et al. Reference Parmar, Quesada, Efird, Pauchulo and Vaugeois2023). As a result, there is a widespread debate over which system is more effective at addressing the challenges facing HRIs in Canada (Clément Reference Clément2014; Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b; Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014; Leslie Reference Leslie, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014). Many studies on Canadian human rights law investigate ways to improve efficiency, although a major focus of this article is efficient claim processing, this only goes so far to help people attain justice. Improving efficiency still excludes those unaware of human rights laws and institutions (Piche Reference Piche2017) and can lead to injustice if complainants feel pressured to mediate their issues (Leslie Reference Leslie, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014).

No jurisdiction has experimented with different models for processing human rights cases more often than British Columbia. The province implemented a commission system between 1974 and 1982, as well as 1996 and 2002, while experimenting with the direct-access system from 1983 to 1996 and 2003 to 2019. Since 2019, the province has operated a hybrid system similar to that in Ontario: there is both a tribunal and a commission, but the latter’s mandate is education and it has no role in managing cases. The choice of models often reflects the priorities of the government: the Social Credit and Liberal governments, for instance, have slashed funding and instituted direct-access models; New Democratic Party governments, in contrast, have invested heavily in the human rights system, including the formation of a robust human rights commission (Clément Reference Clément2014).

Using British Columbia as a case study, this article compares the commission and direct-access systems to determine which is better situated to address delays and rising caseloads. The primary research question is: Which system is more effective at processing complaints and provides better access to a formal hearing? The first section is an overview of the literature that compares the commission and direct-access models. The following sections detail the methodology and findings arising from this study.

Context

There are three models of National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs): ombudsman offices, public defenders and human rights commissions (Cardenas Reference Cardenas2014):

NHRIs’ function as “receptor sites” (Frank et al. Reference Frank, Hironaka and Schoter2000) for the diffusion of global human rights norms within a local context. […] democratic countries, countries with better human rights records, and countries with more international linkages are more likely to establish such institutions. […] by 2004, 133 countries had established 178 NHRIs, including eighty-three classical ombudsman offices, seventy human rights commissions, and twenty-five human rights ombudsman offices. (Russell and Suarez Reference Russell, Suarez, Bajaj and Flowers2017, 27)

Commissions are the most common form of NHRI. Their mandates include responding to inquiries; processing and mediating cases; educating the public about human rights; promoting the importance of human rights; and producing human rights-related research (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b; Clément Reference Clément2017; Parmar and Gill Reference Parmar and Gill2023; De Silva Reference De Silva2020).

In Canada, there are fourteen human rights statutes—one in each of the federal, provincial and territorial jurisdictions. Each jurisdiction has an enforcement agency (HRI) in the form of a commission and/or tribunal. These statutes prohibit discrimination in goods, services, accommodation and facilities; publications and notices; employment practices; tenancy; applications and advertising regarding employment; and membership in trade unions, employers’ organizations or occupational associations. While the grounds of discrimination vary by jurisdiction, most prohibit discrimination on the grounds of sex, gender identity and expression, colour, race, religious beliefs, physical disability, mental disability, age, family status, ancestry or place of origin, marital status and sexual orientation. An action is considered discriminatory if adverse treatment received differs from the treatment given to others for reasons that fall within one of the protected areas and grounds under the statute.

Despite some jurisdictional differences, the Canadian model has several common features, including jurisdiction over the public and private sectors; a focus on conciliation over litigation; an adjudication process as an alternative to the courts; professional human rights investigators and legal representation before tribunals (except in direct-access systems); and a mandate for public education, as well as advocating for legal reform. These features contrast with comparable statutes in other countries that might rely on litigation and the courts rather than administrative tribunals; only apply to the public sector; or provide no representation to support claimants before formal hearings (Cardenas Reference Cardenas2014; Langtry and Lyer Reference Langtry and Lyer2021). Canadian HRIs are also consistent with the Paris Principles (Cardenas Reference Cardenas2014, 37), which are the international standards for NHRIs. Endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly in 1993, the Paris Principles dictate that NHRIs should be established under law; have a broad mandate to promote and protect human rights; have formal and functional independence from government; receive adequate resources and financial autonomy; enjoy the freedom to address any human rights issue; have annual reporting; and cooperate with national and international actors, including civil society (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b, 281–85).

Ontario was the first Canadian jurisdiction to create an administrative tribunal to enforce a human rights statute—the Ontario Human Rights Commission—which was established in 1961 (Tunnicliffe Reference Tunnicliffe2013). By 1977, there was a statute and a state agency in every jurisdiction (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b). A common theme in the history of HRIs in Canada is declining resources and rising caseloads. Funding in all jurisdictions initially expanded dramatically in size and scope when the first HRIs were founded in the 1960s and 1970s. Combined funding for HRIs increased from $3.2 million in 1975 to $12.7 million in 1983 (Clément Reference Clément2014, 173). Ontario alone had fourteen regional offices and thirty-three investigators by 1982 (Clément Reference Clément2014, 172). Over time, however, as Brian Howe and David Johnson have documented in their study on HRIs, funding remained static or even declined in most jurisdictions, beginning in the 1990s (Howe and Johnson Reference Howe and Johnson2000). Budgetary challenges continued into the 2000s. The Canadian Human Rights Commission’s budget, for example, was $22.4 million in 2005–06, $23 million in 2011–12 and $22.1 million in 2014–15 (Canadian Human Rights Commission 2005–23). In British Columbia, the Human Rights Tribunal’s budget was $3 million in 2015–16: the same amount in nominal dollars as it was in 2005–06 (British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal 2006–22).

Meanwhile, caseloads continued to rise. Between 1980 and 1997, caseloads increased in every jurisdiction, particularly in the federal (432 to 2,025), Ontario (994 to 2,775), British Columbia (828 to 1,439) and Alberta (281 to 825) jurisdictions (Howe and Johnson Reference Howe and Johnson2000, 72). Between 1980 and 1997, caseloads in most jurisdictions doubled or more (Howe and Johnson Reference Howe and Johnson2000, 72). Nova Scotia’s Human Rights Commission reported a rise of almost 400 percent between 1981 and 2001 (Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission 2002, 2). Most recently, complaints have exploded in number. In British Columbia, the number of new cases rose from 1,439 in 1996/97 to 3,192 in 2021/22 (British Columbia Human Rights Commission 1996/97; British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal 2021–22).

One solution to the challenge posed by a lack of funding and rising caseloads—which contributes to delays and backlogs—has been to replace the commission model with a direct-access model. This reform was advocated by several studies in the 1990s and 2000s (La Forest et al. Reference La Forest, Black, Dupuis and Jain2000; Cornish et al. Reference Cornish, Miles and Omidvar1992; Ontario Human Rights Commission 2005). These reforms represented a profound shift away from the historical Canadian model.

The commission and direct-access models

The direct-access model has been implemented in British Columbia, Nunavut and Ontario. It enables individuals to appear directly before a formal hearing (unless the case is dismissed during the intake phase). While British Columbia and Ontario have also established commissions, unlike other jurisdictions’ human rights commissions, these institutions focus on education—they do not investigate cases or provide carriage of complaint. Critics argue that the direct-access system is plagued with delays; that people are more likely to be self-represented before hearings; that it prioritizes conflict over conciliation and settlement; and that claimants lack the investigatory powers and expertise to properly prepare a case for a formal hearing (Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014; Leslie Reference Leslie, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014; Alberta Civil Liberties Research Centre 2019). In contrast, critics of the commission model argue that commissions act as “gatekeepers” that deny people access to a hearing; that this function exacerbates delays and costs; and that it unfairly enables commissions to dismiss cases (Eliadis Reference Eliadis, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014a, Reference Eliadis2014b; Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014).

The commission model

In jurisdictions with a commission model, a state agency (e.g., Canadian Human Rights Commission) receives and investigates cases of discrimination. Claimants do not shoulder the burden of investigating and litigating their case. There is no cost or fee to file a case. Cases are often settled through conciliation (Howe and Johnson Reference Howe and Johnson2000; Clément Reference Clément2014). When conciliation fails—and if the investigator finds evidence of discrimination—the commission assigns legal counsel to represent the public interest before a formal hearing (referred to as carriage of complaint). Respondents might pay a fine, offer an apology, reinstate an employee or agree to a negotiated settlement, among other possible settlements (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b; Howe and Johnson Reference Howe and Johnson2000).

As Eliadis (Reference Eliadis2014b) explains, commissions are “first deciders”—they are responsible for intake and they reject cases that are deemed frivolous or do not fall within the jurisdiction of the legislation. The first stage is mediation or conciliation. A Human Rights Officer (HRO) will process the case by communicating with both parties, request written submissions and confirm the details of the case with the claimant and the respondent. They will then offer to mediate between both parties. If mediation fails (or is rejected), the investigator will recommend to senior leadership within the commission whether or not a case should be dismissed or sent to tribunal for a determination. If a commission forwards the claim to a tribunal, then the commission argues the case before the tribunal on behalf of the public interest (except in Saskatchewan, which eliminated its tribunal in 2011 and requires claimants to seek restitution in court).

Three issues, in particular, inform debates on the competing models for human rights law in Canada: gatekeeping, investigation of complaints and carriage of complaints. Opponents of the commission model argue that the agency functions as a gatekeeper that denies claimants the opportunity to appear before a tribunal. Claimants can only appear before a tribunal if approved by the commission, which essentially vets the case. In performing this function, commissions act as a barrier to the tribunal (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b; Leslie Reference Leslie, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014; Clément Reference Clément2014). Leslie (Reference Leslie, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014), however, argues that the commission model’s gatekeeping function benefits complainants. Commissions are impartial arbiters. Gatekeeping ensures that human rights claims deemed suitable for further adjudication are accepted and sent to a tribunal rather than overwhelming the tribunal with frivolous cases or claims that have no chance of success. This system ensures that “decisions should not be or appear to be arbitrary, unfair, or inconsistent” (Leslie Reference Leslie, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014, 147). The gatekeeper function also provides the basis for carriage of complaint, which ensures that claimants are not alone in making a legal case before a tribunal.

Another strength of the commission model is investigation. There are no HROs or investigators in the direct-access model. In the commission system, a case worker investigates the case by attaining information from both the complainant(s) and respondent(s). This includes speaking to both parties about their experiences; interviewing witnesses; and assembling documentation. Human rights legislation provides investigators with powers to compel the production of documents for their inquiry, such as employment records. Additionally, investigators produce a report that features a breakdown of the case and may additionally contain any recommendations on that case (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b). HROs are an important feature of the commission model. In addition to the legal power to compel records and collect information from both respondents and claimants, HROs offer expert assessment of the evidence. They are in a better situation than claimants to conduct investigations and to identify patterns of prejudiced behaviour such as discriminatory hiring practices or inequitable pay practices. As Eliadis (Reference Eliadis2014b, 36) explains, HROs “occupy specialized positions in commissions and have training in subjects such as evidence, human rights law, constitutional law, interviewing, and document management.”

A third benefit of the commission model is carriage of complaint. If a commission determines that a case has merit, it assigns legal counsel to argue the case before a tribunal. They do not represent claimants—who can represent themselves or hire legal counsel—but, rather, they represent the public interest because the outcome of the case has broader implications, such as discouraging sexual harassment in the workplace. The role of the commission’s representative is to “lead evidence and make representations in support of the complaint” (La Forest et al. Reference La Forest, Black, Dupuis and Jain2000, 77).

These features of the commission model—gatekeeping, investigation and carriage of complaint—are especially beneficial to marginalized populations who lack the resources to prepare complex cases, investigate and collect evidence or to hire legal counsel. These attributes are a defining feature of the Canadian model of anti-discrimination legislation, in contrast to other countries’ equality laws that often lack legal assistance and investigators, and/or require claimants to seek restitution through the courts rather than through administrative tribunals (Cardenas Reference Cardenas2014; Eliadis Reference Eliadis, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014a, Reference Eliadis2014b).

The direct-access model

Some jurisdictions have shifted the processing of discrimination cases exclusively to a tribunal: the direct-access model. In this system, the tribunal receives and processes all cases. In a direct-access model, tribunals provide mediation services and determine which cases appear before the tribunal (Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014; Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b). Cases are either dismissed at the outset; successfully mediated by staff at the tribunal; or sent to a tribunal for determination.

Some scholars such as Eliadis (Reference Eliadis2014b), Flaherty (Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014) and Tsun (Reference Tsun2009) argue that the direct-access system solves several problems around delays and access to justice that are systemic in the commission model. In Ontario, only seventy-five of 2,500 cases went to adjudication each year under the commission model (Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014). Tsun (Reference Tsun2009) argued that the commission system was overly complex and that changing to a direct-access model in Ontario was necessary. Both Eliadis and Flaherty note that cases processed by using a direct-access system have a greater likelihood of reaching the adjudication stage because there is no commission acting as a gatekeeper (Reference Eliadis2014b; Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014). In 2012, the average wait time under the direct-access system in Ontario was 12.7 months (Pinto 2012, as cited in Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b). This was a significant improvement from the pre-tribunal system in Ontario, when the average case required five years or more to be adjudicated. Flaherty also argues that the direct-access system processes cases more efficiently—Ontario’s tribunal cleared 95 percent of their cases in 2009–10. In 2010–11, Ontario’s tribunal processed a greater number of cases than it received (Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014).

Although the direct-access model dispenses with the commission, critics argue that it still performs a gatekeeping function by dismissing meritless complaints or cases that are outside the scope of the legislation. At the same time, however, the commission’s gatekeeping function creates significant barriers for claimants. Human rights commissions’ determinations are difficult to overturn. In 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that judges should defer to human rights tribunals because of their specialized expertise in interpreting human rights statutes (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b, 250). Tribunal decisions, in particular, are only invalidated in cases involving errors in legal reasoning; if the decision is unjustifiable; or in circumstances involving improper procedures (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b, 250–51). In this way, eliminating gatekeeping benefits claimants who prefer to present their case directly before a tribunal that can enforce remedies (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b; Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014; La Forest et al. Reference La Forest, Black, Dupuis and Jain2000). Flaherty (Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014) argues that eliminating investigations results in faster response times. Eliminating the gatekeeping of complaints, moreover, ensures that all claimants can secure a hearing for their claim (Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014; Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b; La Forest et al. Reference La Forest, Black, Dupuis and Jain2000; Tsun Reference Tsun2009).

There are no investigators under the direct-access system. Rather, tribunals rely on disclosure. Disclosure involves claimants and respondents providing each other and the tribunal with documentation that is relevant to the case. Both parties are also responsible for providing a list of witnesses who will offer testimony at the tribunal. There are penalties for non-compliance. A claimant could have their complaint dismissed or, alternatively, the claimant or respondent can be fined for improper conduct (British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal 2024).

Finally, the direct-access system has no carriage of complaint. There is no guaranteed representation in the direct-access system; instead, claimants need to hire a lawyer, represent themselves or apply for support from a legal aid clinic associated with the tribunal. In British Columbia, the government provides funding to the BC Human Rights Clinic, which offers some legal assistance and general information and support to complainants. However, many complainants are left without representation because the Clinic has limited resources. To illustrate, in the years for which data on representation are available, most complainants were without representation in any given year. On average, complainants had representation only 37 percent of the time from 2006 to 2016 (British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal 2006–22). Lack of representation also impacts people within the commission model to a lesser extent, as the commission does not guarantee legal help with any aspect of the complaint except at the hearing stage, which can also limit access (Parmar et al. Reference Parmar, Quesada, Efird, Pauchulo and Vaugeois2023).

In sum, there are profound disagreements over the benefits of each model. The most compelling argument in favour of the direct-access system is that it is faster, more efficient and therefore provides greater access to seeking restitution for people who experience discrimination. This claim relies, in part, on the premise that the direct-access model is more efficient than the commission model.

Methodology

There is a dearth of research that compares the effectiveness of the commission model and the direct-access model. To determine which system is more efficient—and which system sends more complaints to a full hearing—we analyzed annual reports from British Columbia. These reports were produced during the last time the commission system was operational in British Columbia from 1996 to 2002 and for the last 16 years of the direct-access system from 2006 to 2022 (the years 2006–22 were chosen as the data are the most complete from this period and data beyond 2022 were excluded as reports after 2022 contained incomplete or missing information). The annual reports for the years 1996–2002 contain statistical information for the British Columbia Human Rights Commission (BCHRC), whereas the reports for the years 2006–22 contain statistical information on the operations of the British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal (BCHRT). The annual reports include data on how cases are closed by each system. Cases can be closed by screening, mediation or adjudication. Annual reports produced during the commission system from 1997 to 2002 do not include information concerning complaints processed at the tribunal for adjudication, as these data are missing. The Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLII) was used to supplement these missing data for these years and these data include cases dismissed and justified at the tribunal.

When a case is filed with the BCHRC or the BCHRT, it is screened by the institution to determine whether the case should be accepted or dismissed. Screening is a necessary function of HRIs to ensure that claims are within the mandate of the legislation and that they have been filed within the time limits set out by the institution. As noted above, this can lead to issues of access for marginalized groups and those who do not have legal and other support. The BCHRC can screen out a complaint either before or after an investigation. The BCHRT, in contrast, will screen out a complaint if it is deemed to be outside of its jurisdiction, if it is deemed untimely or if a respondent’s motion to dismiss is accepted. When that is done, a case is not considered closed as a result of screening, as these complaints have gone past the screening stage.

Cases may also be settled at the BCHRC or BCHRT instead of being screened or adjudicated. The settlement process involves both the complainant and the respondent coming together with an impartial mediator to try and resolve the case without a hearing. If both parties agree to a settlement, the case is closed and the respondent typically provides the complainant with a monetary sum (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b). During the operation of the BCHRC, a case could be settled before the investigation or once it has been sent to the tribunal. In the BCHRT, a case may be settled at any time before it is found to be justified or dismissed at a hearing. We determined which system was more efficient by comparing how many cases each system closed relative to how many they opened. We assess which system closed more complaints, which system closed complaints more quickly and, in so doing, reduced backlogs and delays (British Columbia Human Rights Commission 1996–2002; British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal 2006–22; CanLII 1997–2002). We also analyze the rate at which each model screened out cases. Doing so helps us understand which cases see a tribunal and in turn gain greater access to justice. Here, we discuss access to justice as meaning a chance to have their complaint resolved in a timely manner.

Findings

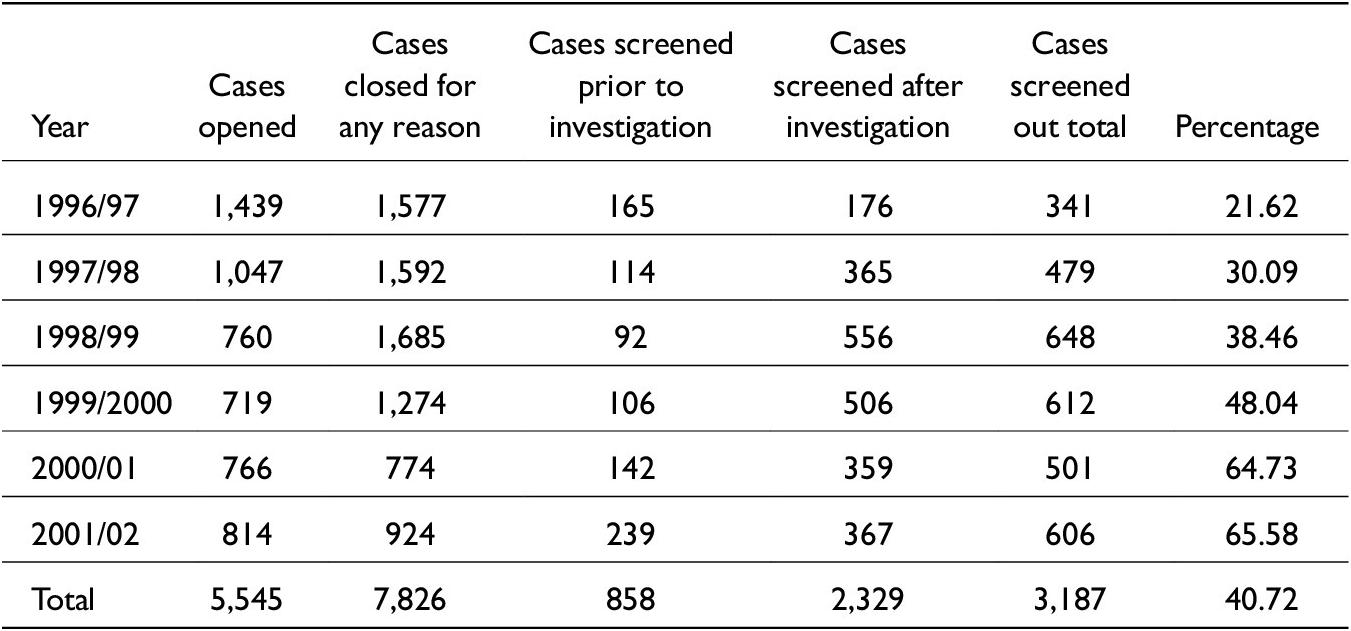

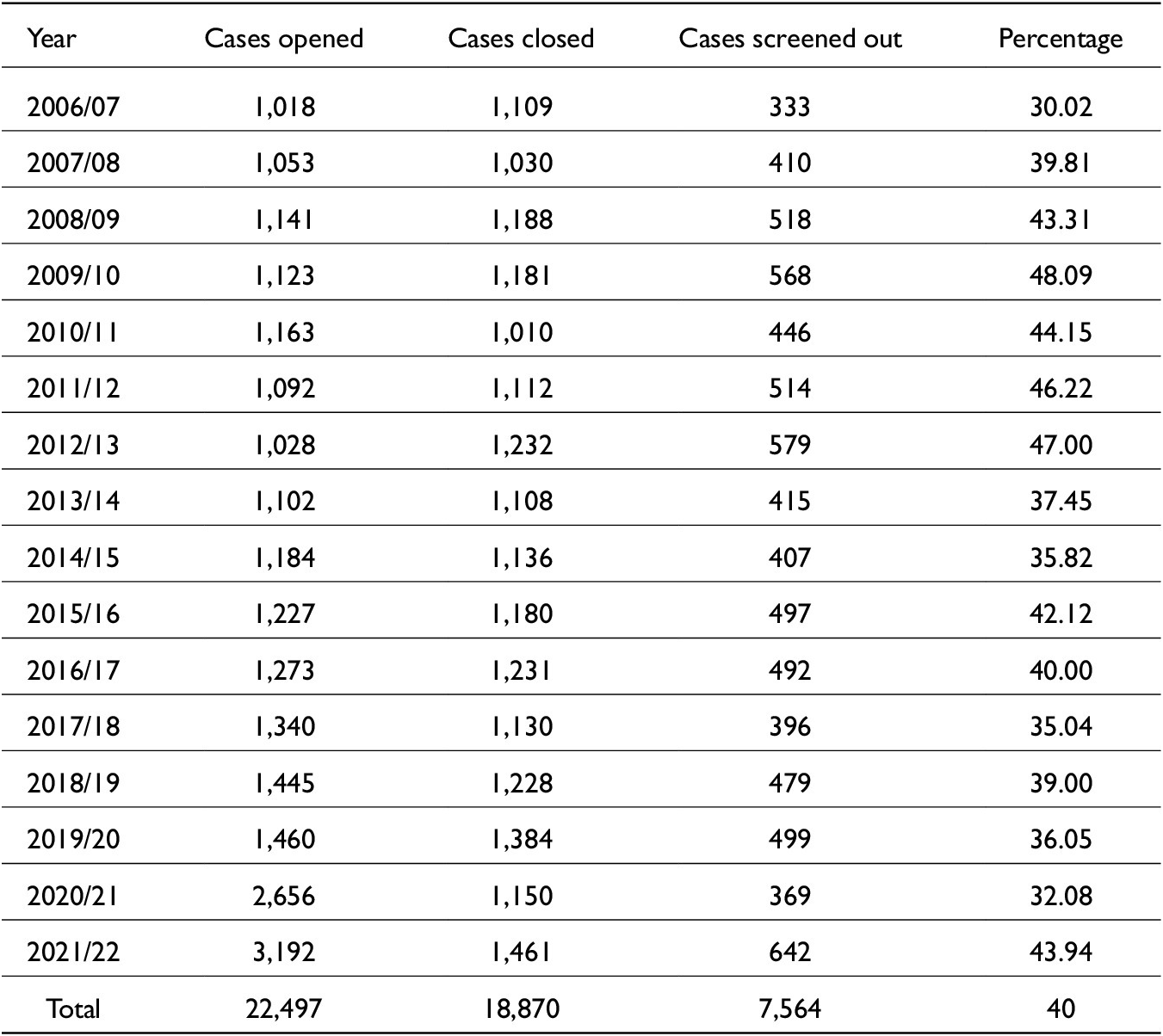

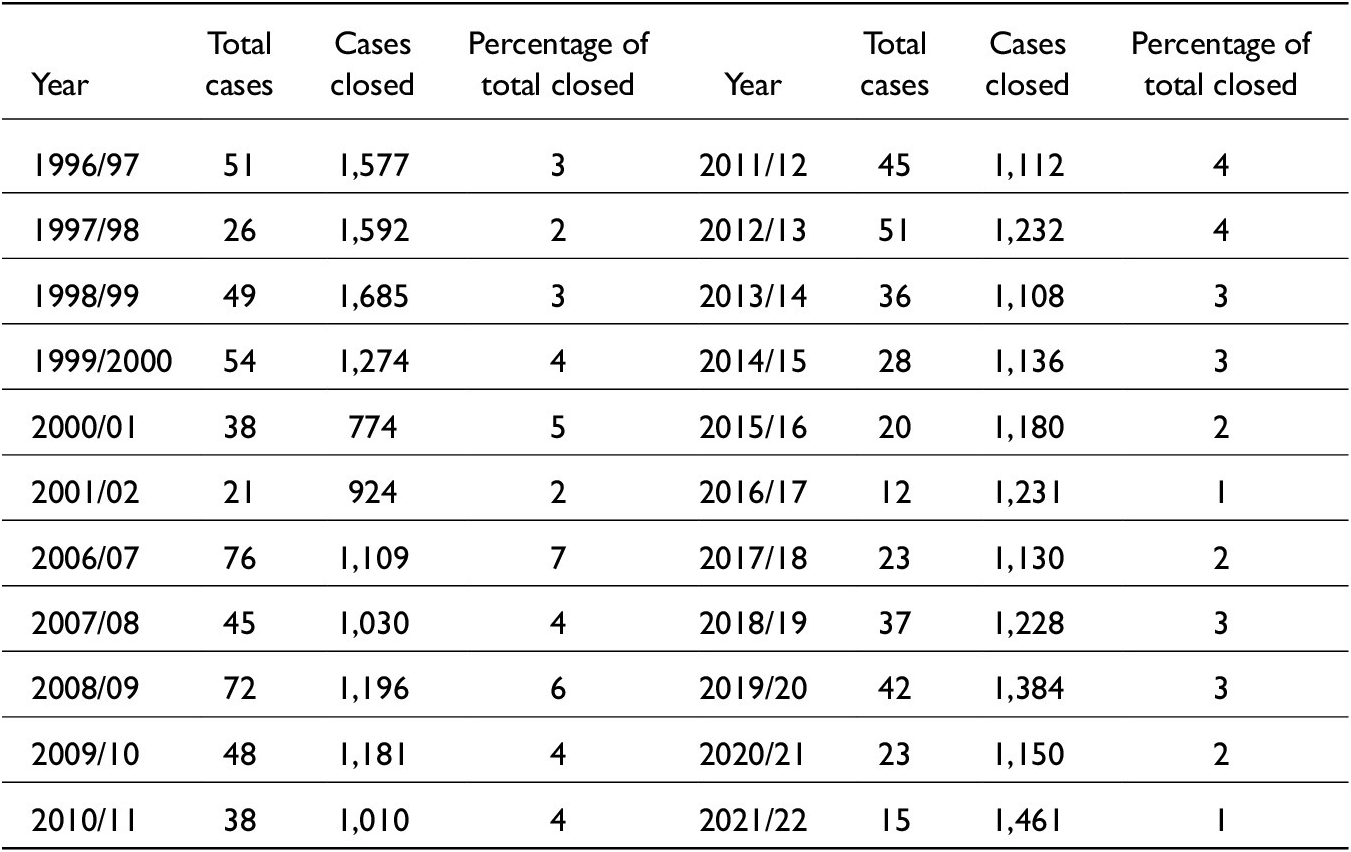

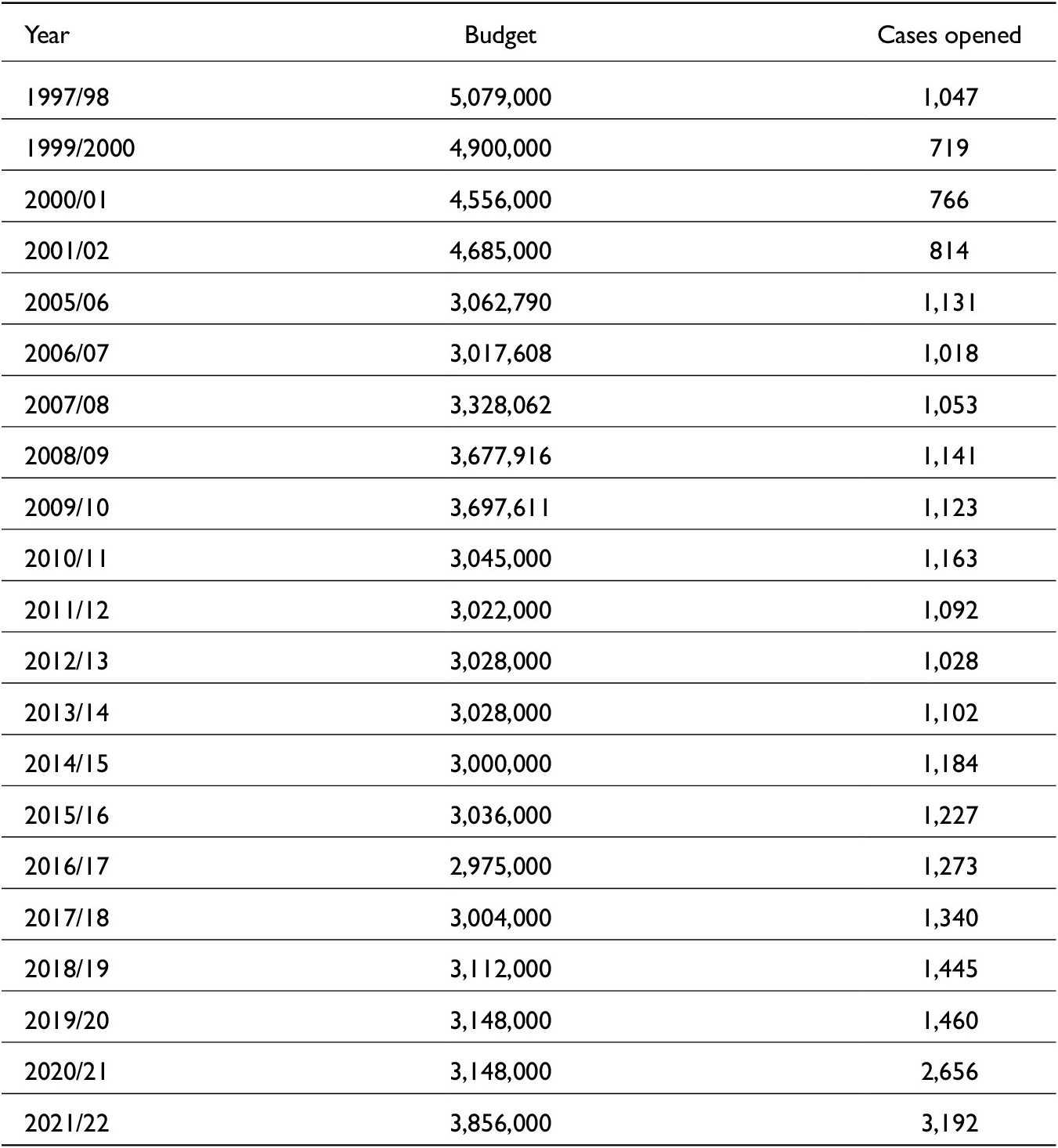

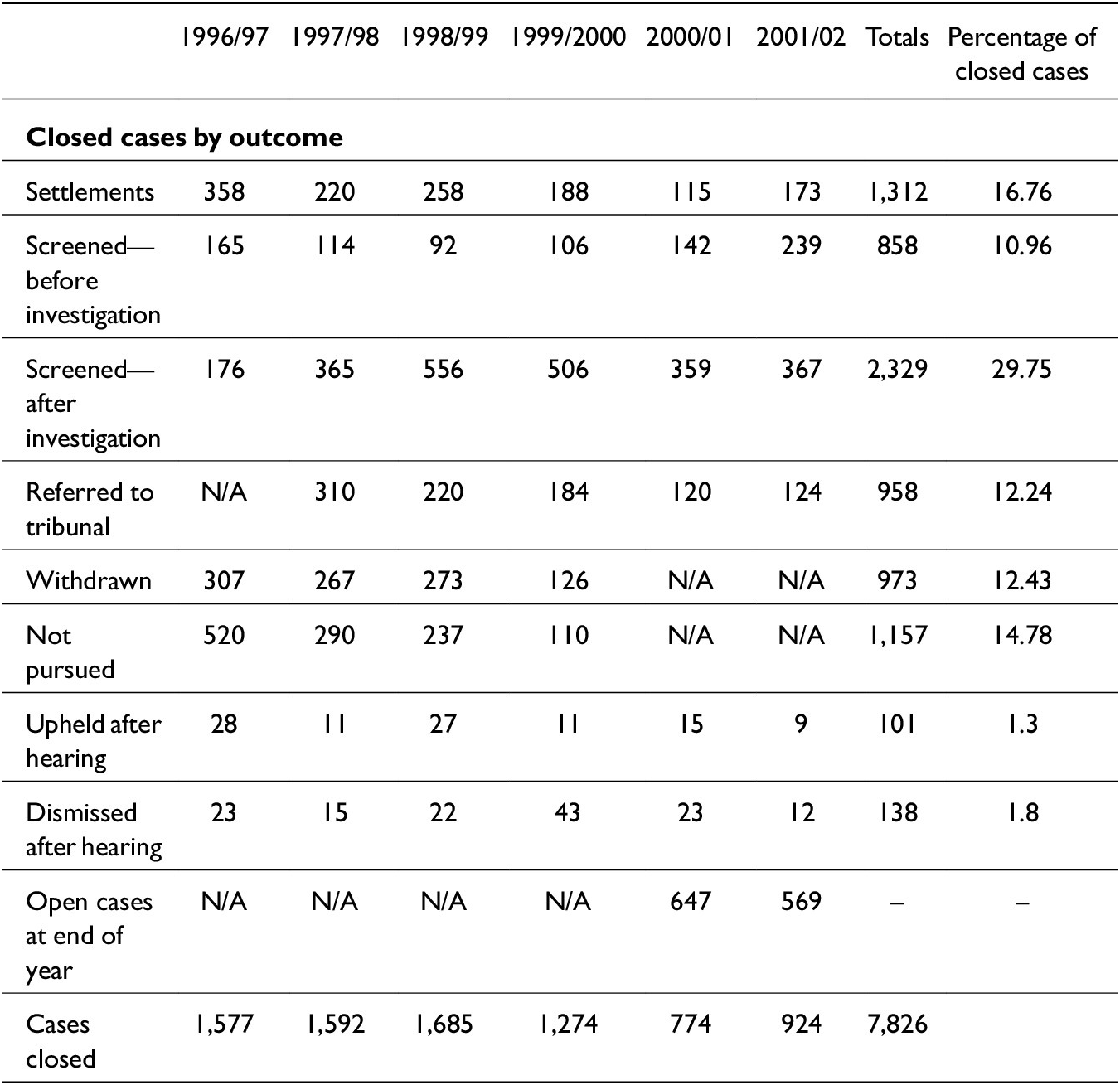

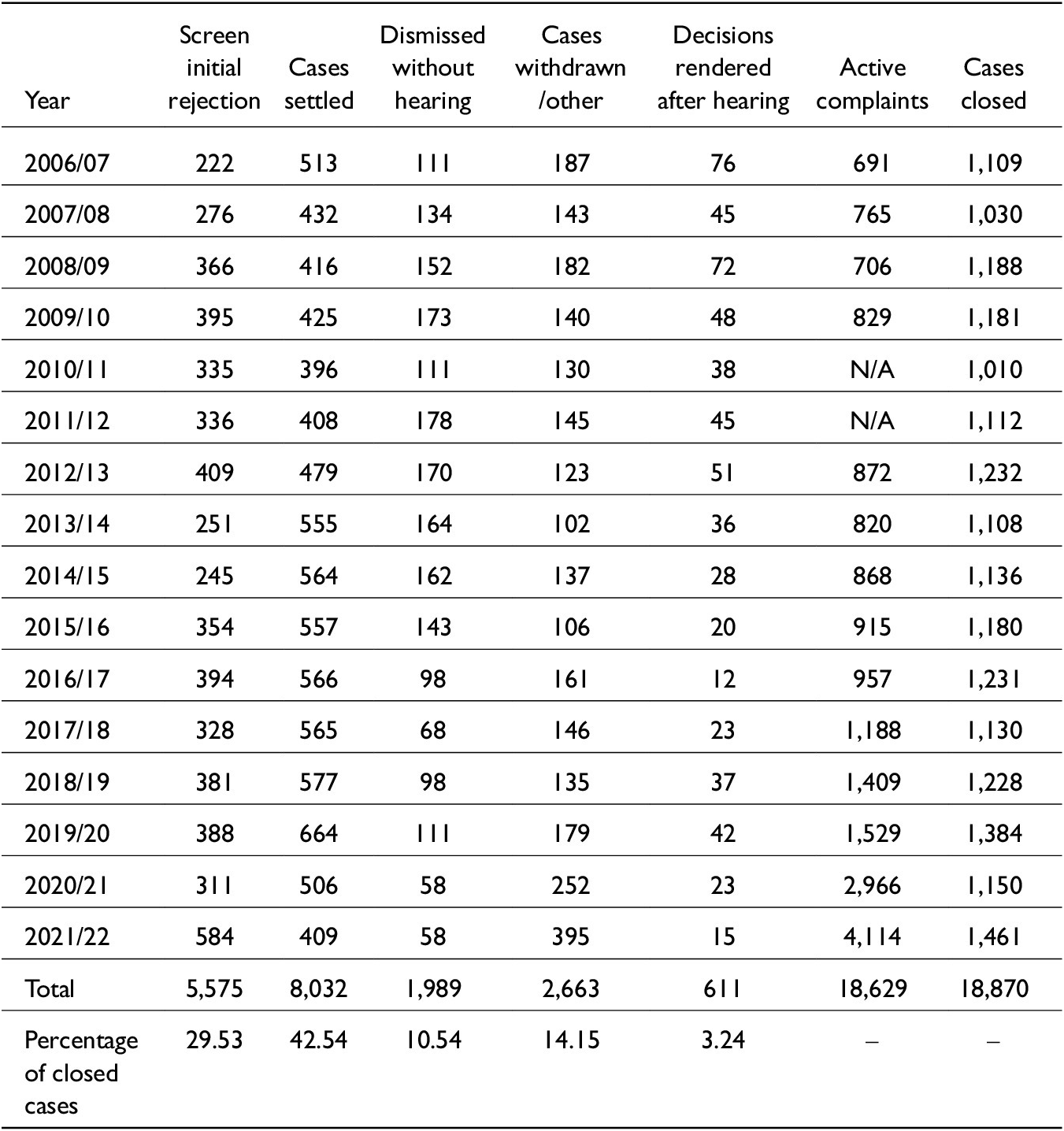

We begin our analysis by comparing how many cases were opened and closed under the commission and the direct-access models (Tables 1 and 2). The BCHRC (Table 1) closed more cases than it opened compared with the BCHRT—5,545 cases opened (excluding screened cases) and 7,826 closed (closed cases include a case backlog from the BCHRC’s predecessor, the BC Human Rights Council). In contrast, the BCHRT opened 22,497 cases and closed 18,870 (Table 2).Footnote 1 Over six years, the BCHRC closed 2,281 cases more than it opened. Alternatively, the BCHRT in the direct-access system opened 3,627 cases more than it closed over a sixteen-year period. The BCHRC closed 41 percent more cases then it opened and the BCHRT closed 16 percent fewer cases then it opened. Even though both are dealing with backlogged complaints, the commission model was more efficient at processing claims overall.

Table 1. Cases Opened, Closed and Screened Out by the BC Human Rights Commission (BCHRC) Over Time, 1996–2002

Source: Compiled from BCHRC 1996–2002.

Notes: Cases opened: cases newly accepted for filing each year. Cases closed for any reason: includes cases that are settled, screened, etc. Screened out prior to investigation: cases that are screened out before they are investigated at the commission. Cases screened out after investigation: cases that are screened out once an investigation is completed and no discrimination is found or could be proven. Cases screened out total: all complaints screened out that year. Percentage: refers to percentage of complaints closed that year via screening only; for other methods, see Table 3.

Table 2. Cases Opened, Closed and Screened Out by the BCHRT Over Time, 2006–22

Source: Compiled from BCHRT 2006–22.

Notes: Cases opened: cases newly accepted for filing each year. Cases closed: includes cases closed by settlement, screening, etc. Cases screened out: includes cases screened out at any stage, those that are filed late and those that have been accepted for dismissal. Percentage: refers to percentage of complaints closed via screening; for other closing methods, see Table 4.

Screening is a pervasive way of reducing complaints volumes at both institutions. Tables 1 and 2 show that both the BCHRC and the BCHRT screened out cases at a higher rate over time. During the years in which the government of British Columbia instituted the BCHRC, the total number of screened-out cases almost doubled over the six-year period. Table 1 also shows that 341 cases were closed through screening by the BCHRC in the first year compared with the final year (2001/02), when it screened out 606 cases. Table 2 displays a similar trend for the BCHRT. The cases closed by screening more than doubled from 333 cases in 2006/07 to 642 in 2021/22.

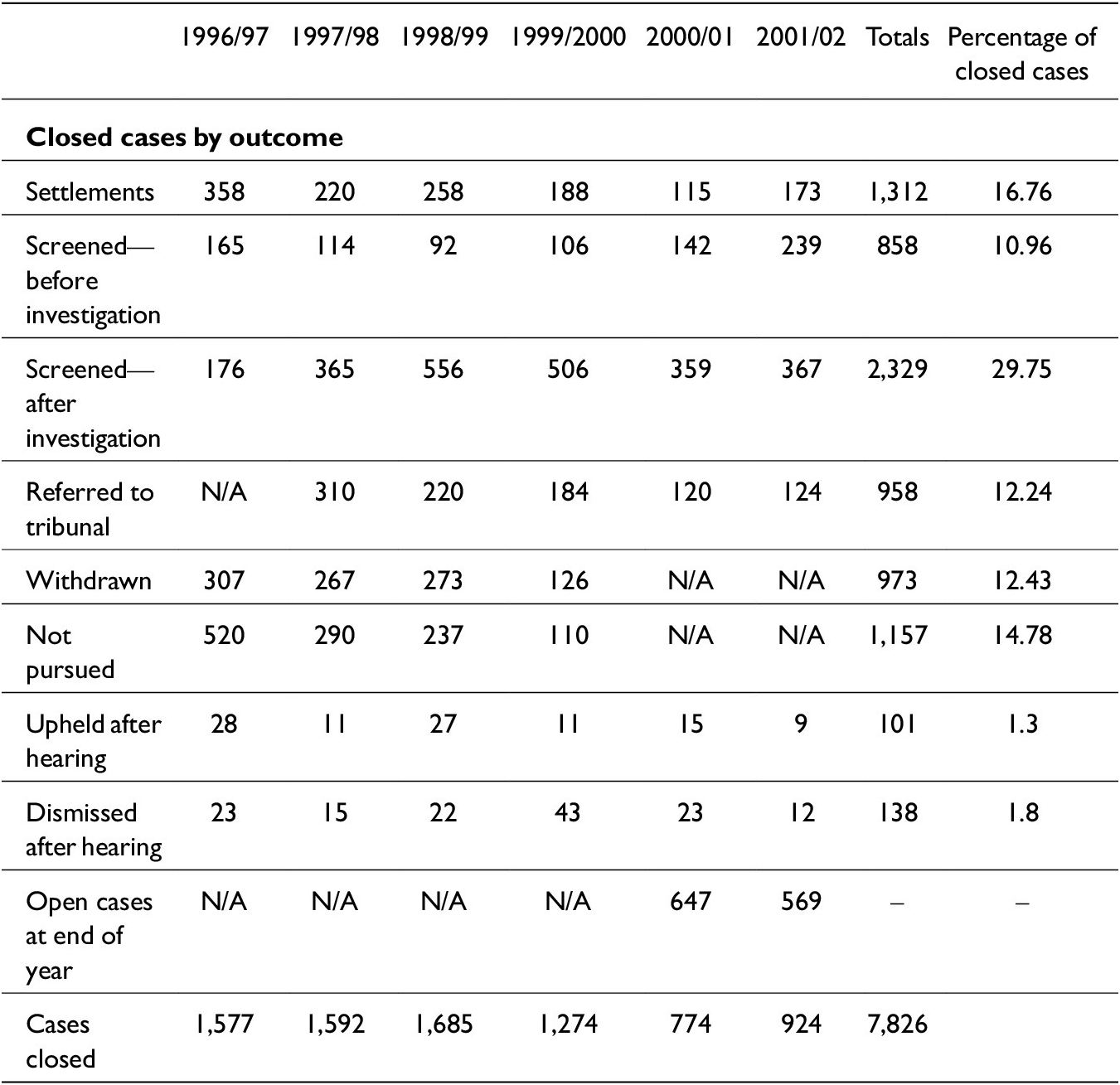

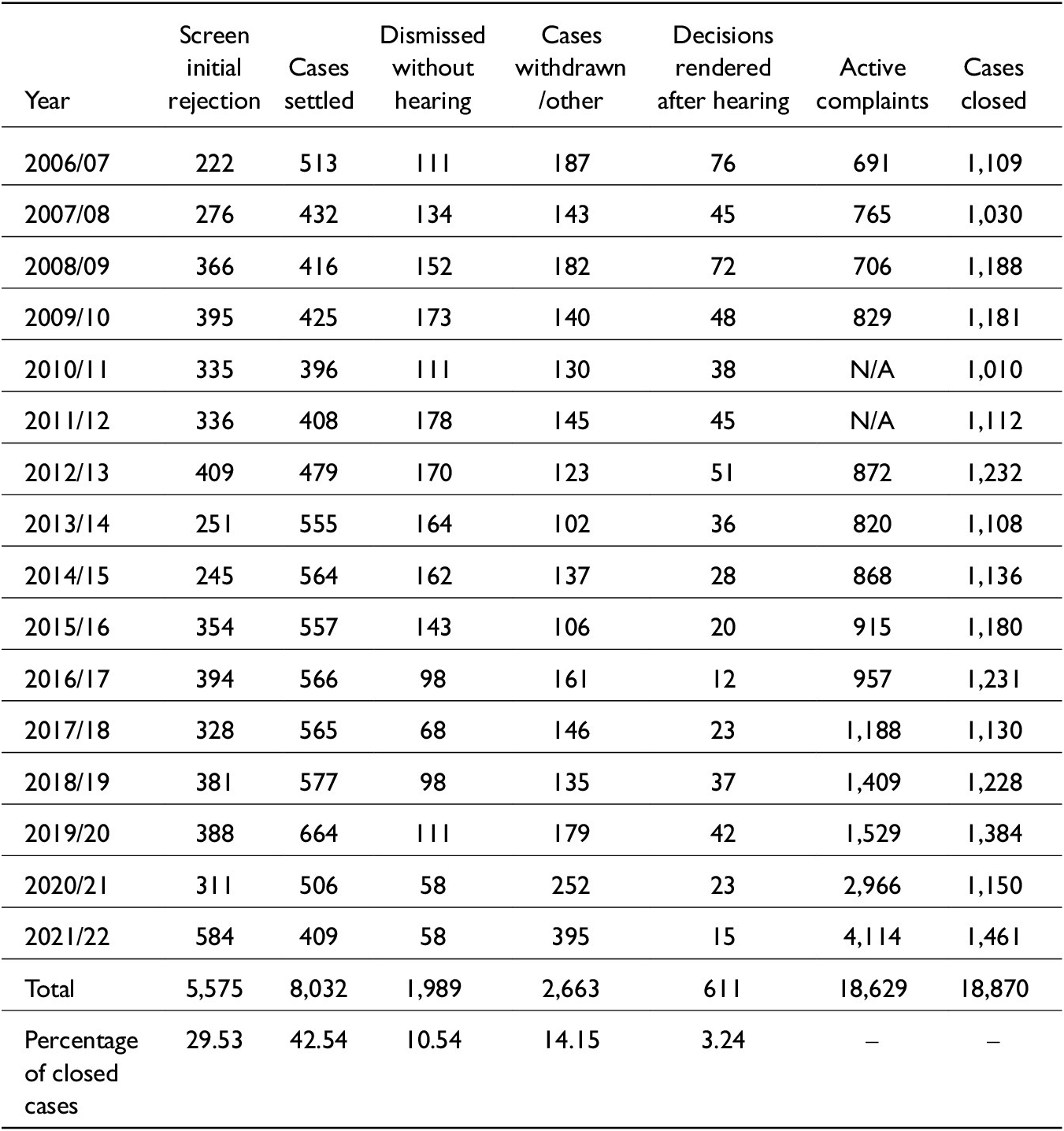

We also analyze the extent to which each system mediated or screened out complaints, which helps to further answer the first research question on the efficiency of each system. Tables 3 and 4 report the number of complaints closed by each system. Although both systems screened out a larger number of cases over time, Table 3 shows that the BCHRC screened out proportionately more cases than did the BCHRT, as seen through Table 4. The BCHRC also closed the majority of its cases by screening, whereas the BCHRT closed the majority of its cases through settlement. Under the BCHRC, for every year except 1996/97, cases were closed more by screening than by any other method. Additionally, the total number of cases screened out from 1996 to 2002 amounted to 3,187, or 41 percent of all cases closed at the time. At the BCHRT, the tribunal closed 18,870 cases—40 percent of those cases were screened out before proceeding to the tribunal (screened includes those removed in the initial process, cases that were filed late and those complaints that were accepted for dismissal initiated by respondents). During the years in which the government of British Columbia employed a direct-access system, 43 percent of all closed cases were closed by way of a settlement over the period studied (Table 4).Footnote 2 In sum, screening out cases was a common strategy for closing cases for both the BCHRC and the BCHRT. But it was more common with the former and cases were more likely to be mediated (settled) under the latter. For this metric, though the commission may end up as being more efficient, the direct-access system provides more people with the ability to reach some level of restitution through mediation.

Table 3. Cases Closed by the BCHRC in 1996–2002 Organized by Outcome

Source: Compiled from BCHRC 1996–2002.

Notes: Settlements: cases closed by mediation. Screened—before investigation: cases screened out before investigation. Screened—after investigation: cases screened out after investigation. Referred to tribunal: number of cases sent to tribunal for processing in that year; 1996/97 has information from the tribunal on how complaints were processed, whereas every other year does not. Withdrawn: cases that were withdrawn. Not pursued: cases not pursued by complainants. Upheld after hearing: complaints found in favour of complainants (justified). Dismissed after hearing: complaints found in favour of respondent (dismissed). Open cases at end of year: cases awaiting processing at the end of the year (backlogged cases). Cases closed: cases closed for any of the above reasons. Percentage of closed cases: refers to the percentage of each category closed relative to the total number of closed cases N/A: information was not available in that category for that year. Recovered information from the CanLII reports increased the closed rates for the commission period by 188 cases for years 1997–2002 because of the addition of hearing numbers for those years.

Table 4. Cases Closed by the BCHRT in 2006–22 Organized by Outcome

Source: Compiled from BCHRT 2006–22.

Notes: Screen initial rejection: cases screened out initially (not within code). Cases settled: cases closed by settlement. Dismissed without hearing: cases dismissed due to being filed late or because a dismissal request was granted. Cases withdrawn/other: cases withdrawn, not pursued or other. Decisions rendered after hearing: decisions rendered by the tribunal after a hearing. Active complaints: complaints currently awaiting processing (backlogged cases). Cases closed: cases closed by settlement, screening, etc. Percentage of closed cases: refers to the percentage of category closed relative to total closed cases.

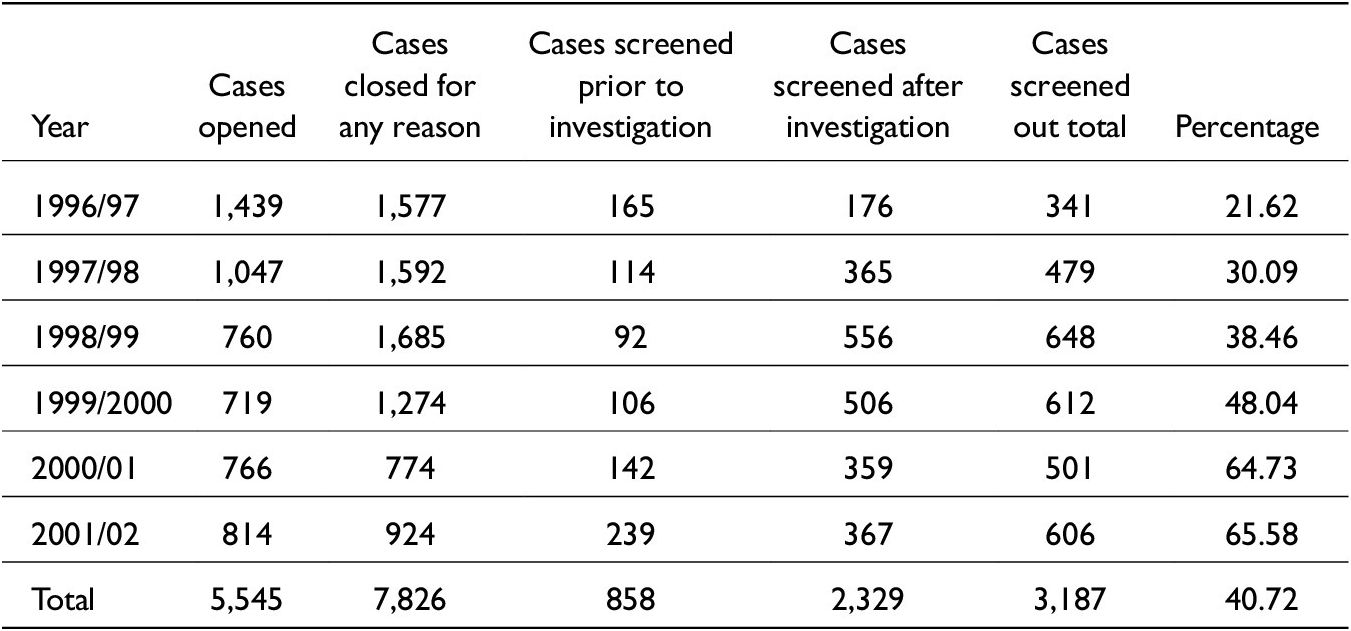

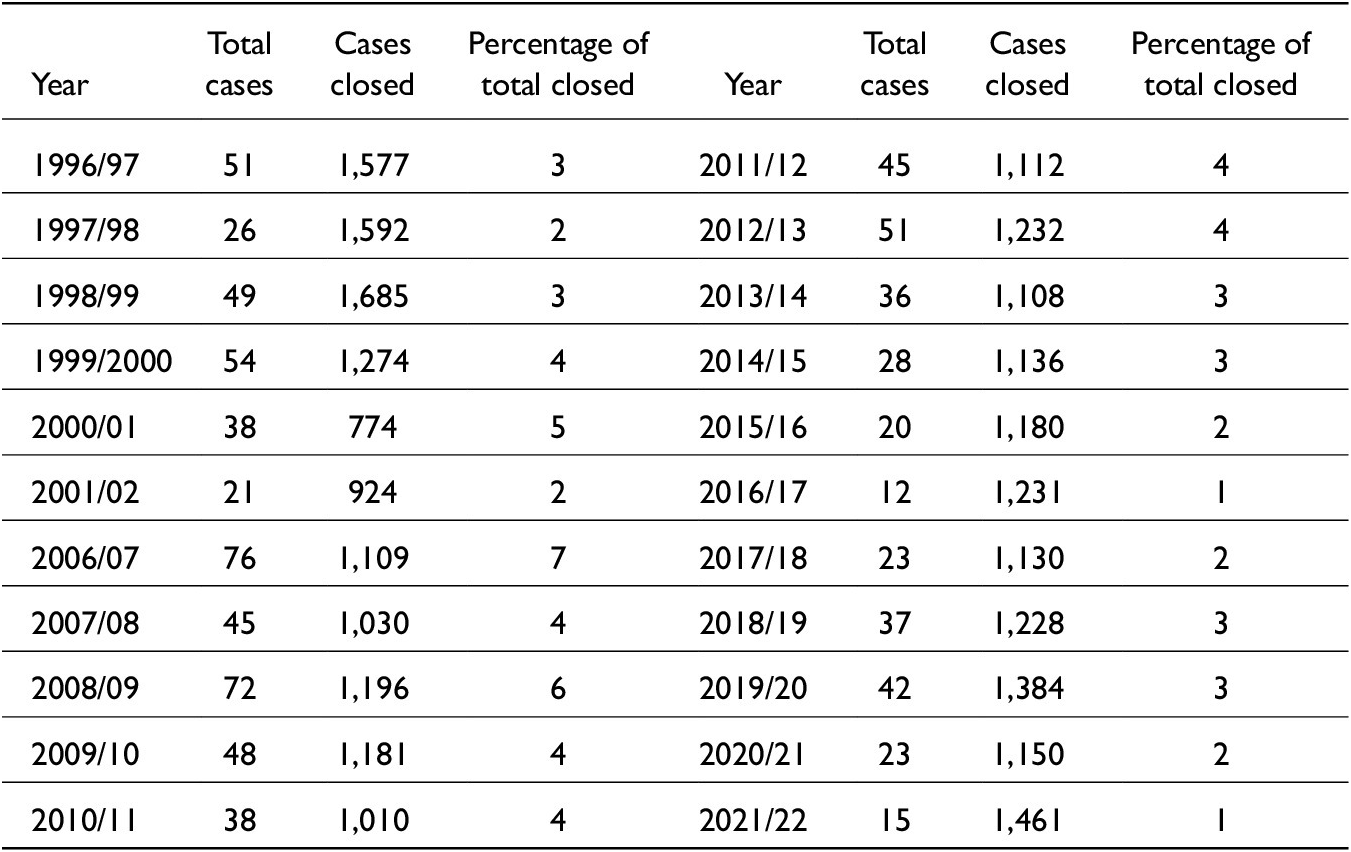

If cases are not settled or dismissed during the screening process, the BCHRC or BCHRT forwards the case to a hearing for adjudication. Greater access to a hearing is a means of achieving greater access to justice and these analyses allow us to answer our second research question. Table 5 looks at the cases that were sent to formal hearings. The table shows that both systems had cases sent to adjudication less often over time. Between 1996 and 2022, the number of formal hearings rendered by both systems decreased, with fifty-one decisions rendered in 1996/97 compared with fifteen decisions rendered in 2021/22. This means that 3.2 percent of cases closed in 1996/97 were closed via adjudication, compared with only 1 percent of cases closed by adjudication in 2021/22. The number of cases opened at the BCHRT increased from 1,018 in 2006/07 to 3,192 in 2021/22. However, decisions rendered after a hearing have decreased over time—from seventy-six decisions in 2006/07 to only fifteen decisions in 2021/22. There is a brief period from 2010/11 to 2012/13 in which the cases increase from thirty-eight to fifty-one, but the numbers decrease again to fifteen. In 2006/07, the seventy-six decisions rendered equalled 7 percent of the cases closed during the year, compared with 2021/22, in which fifteen decisions were rendered, equalling 1 percent of the total cases closed during this period. In other words, complainants were less likely to reach a hearing under the BCHRT.

Table 5. Total Tribunal Decisions Rendered Over Both Systems: BCHRC 1996–2002 and BCHRT 2006–22

Source: Compiled from BCHRC 1996–2002 and BCHRC 2006–22.

Notes: Total cases: number of cases decided by adjudication. Cases closed: includes cases closed by settlement, screening, etc. Percentage of total closed: refers to the percentage of cases closed via adjudication.

In British Columbia, there were proportionately fewer cases going to the hearing stage under the direct-access system compared with under the commission system, although fewer cases did appear before a formal hearing over time under the commission system. The tribunal rendered fifty-one decisions in 1996/97 but only twenty-one in 2001/02. The highest number of decisions rendered during the employment of the commission system occurred not in the first year of operation in 1996/97, but rather in 1999/2000, when the total number of decisions rendered was fifty-four. It is worth noting that the number of cases decreased from 1,439 in 1996/97 to 814 in 2001/02. However, hearings accounted for 3.2 percent of the closed cases in 1996/97 compared with 2.3 percent of the closed cases in 2001/02. The number of hearings remains at a low percentage of cases closed each year. Overall, these data demonstrate that complainants do not attain the same level of access to hearings each year, regardless of the system. Instead, their cases are increasingly screened, settled or backlogged. On this front, some may argue that less justice is achieved because cases are increasingly not heard.

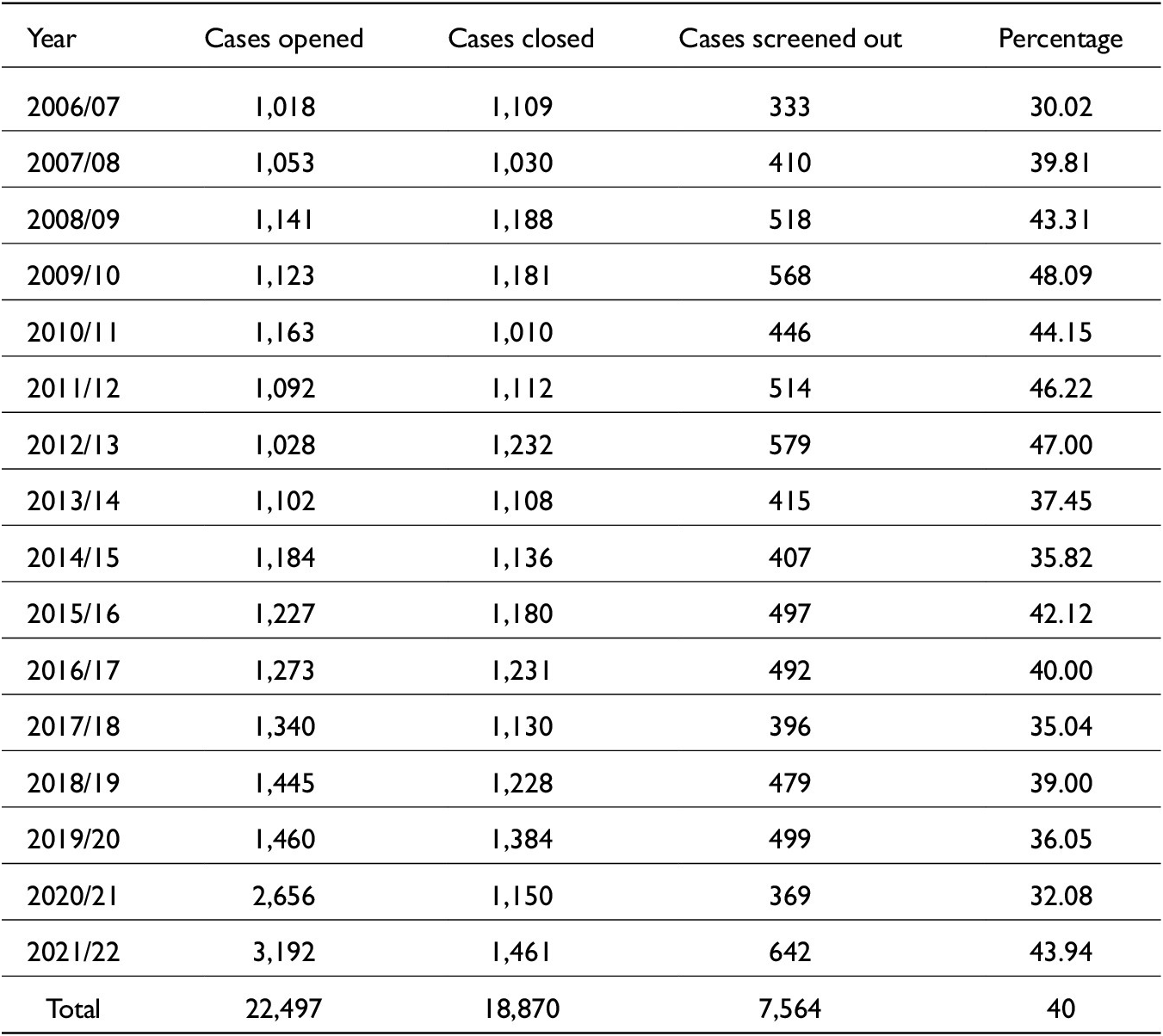

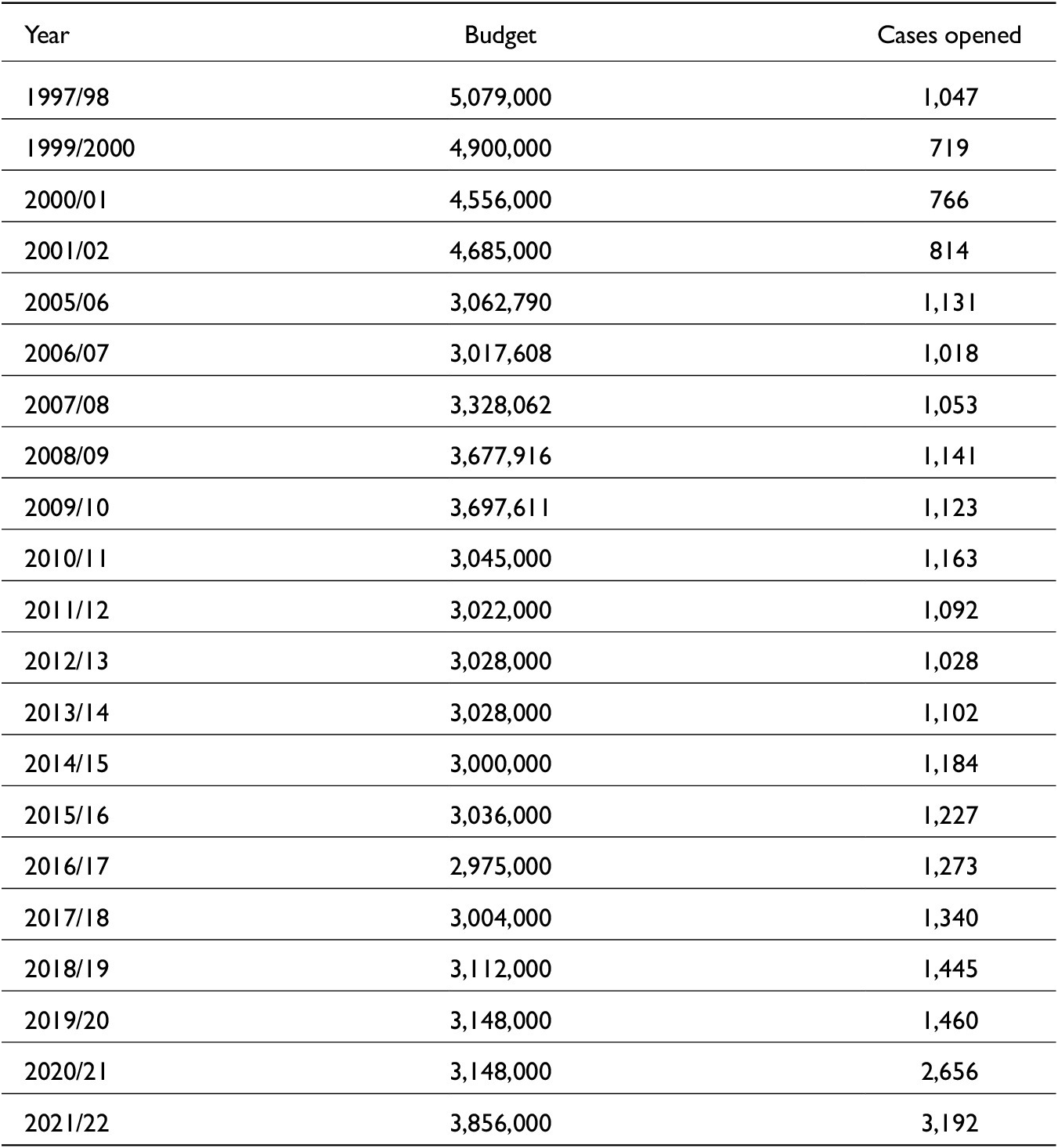

One explanation for why the British Columbia Human Rights Commission closed more complaints and was more efficient overall might be related to the level of funding received compared with the level of complaints logged. In order to address this, we analyzed the funding over time. The years for which funding data were available, from 1997 to 2022,Footnote 3 provide some credence to this argument. As shown in Table 6, in 1997, the British Columbia Human Rights Commission’s budget was $5,079,000, while their caseload was 1,047. In comparison, the BCHRT’s funding in 2022 was $3,856,000, while their matching caseload was 3,192. During this 25-year period, HRIs have seen an overall decrease in funding of around 24 percent, while their caseloads have increased by over 300 percent. With additional funding, human rights systems should be able to perform their duties more effectively. Greschner et al. (Reference Greschner, Hutchinson, Archdekin and Lwanga1996) note that the Saskatchewan commission was able to process cases more effectively when it had an expanded short-term budget increase that allowed more staff to be hired to process claims (1996). It would be reasonable to assume that increased funding would have had a similar impact in British Columbia.

Table 6. British Columbia Human Rights Commission/Tribunal Budgets and Cases Opened, 1997–2022

Source: Compiled from BCHRC and BCHRT cases and budget data from 1997–2022 (1996/97 and 1998/99 not included, as budget information from these years is missing).

Notes: Cases opened and budget data for each year data were available.

Discussion and conclusion

Canadian HRIs have been beset with challenges related to their efficiency, including delays and backlogs of cases (Clément Reference Clément2017; Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014; Howe and Johnson Reference Howe and Johnson2000; Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b; Greschner et al. Reference Greschner, Hutchinson, Archdekin and Lwanga1996; Symons et al. Reference Symons, Abella and Armstrong1977; Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission 2001; Ontario Human Rights Commission 2005). In this study, we examined the BC human rights systems over twenty-six years by looking at its commission system (1996–2002) and its direct-access system (2006–22). Our objective was to determine whether the direct-access system is, as some advocates have claimed, more efficient at processing cases filed under the provincial human rights code. In other words, does the direct-access system, which dispenses with the gatekeeping function of a commission, provide better access to justice?

In general, British Columbia’s commission system closed cases more quickly than did the direct-access system. It also closed considerably more cases. The commission closes the majority of its complaints through screening, whereas the direct-access system closed more complaints through mediation. The commission’s screening out of cases means fewer complaints reaching later stages and thereby less access to justice, which is in line with what Eliadis (Reference Eliadis2014b) and Flaherty (Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014) observe. Also, by relying more on settlements, the direct-access system ensures that more parties can come together collaboratively towards an agreeable solution. A collaborative option can be especially important when the alternative is an adversarial and lengthy trial, although parties can often feel pushed towards a mediation, which upsets the idea of settlements being totally conciliatory (Clément et al. Reference Clément, Parmar, Quesada and Vaugeois2025).

There are also two other considerations. First, more time is spent in the direct-access system as more cases are mediated and they still do not have a full hearing. One of the main justifications by scholars who argue in favour of a direct-access system is that it is said to improve access to a hearing (Eliadis Reference Eliadis2014b; Flaherty Reference Flaherty, Day, Lamarche and Norman2014). This was not the case in the years that we analyzed in British Columbia. Second, and more importantly, the direct-access system in British Columbia was less efficient, which means justice is delayed.

To conclude, human rights systems must be properly funded; it is reasonable to assume that a boost in funding would allow an increase in the number of staff to handle the large surplus of cases inundating human rights systems in British Columbia and beyond. Moreover, if human rights are to be taken seriously, it is important for human rights systems to not only offer greater access to justice, but also efficiently deliver it. It is clear in this research that one way to do so for British Columbia and Canada would be to ensure that the commission system is not dismantled and forgotten, but improved and strengthened.