Policy Significance Statement

Digital inclusion is a significant issue today, given the broader focus on disability inclusion internationally. How national digital ID apps are designed for inclusion, however, leaves much to be desired. This paper spotlights the workings of Singpass, Singapore’s national digital ID app. It situates Singpass within international regimes around web and app accessibility as well as local standards of digital inclusion. It highlights the importance of designing for disability, noting that while international guidelines and standards may provide useful starting points, there also needs to be standards that take into account local issues. This has policy implications for national digital ID apps, which are being developed around the world.

1. Introduction

National digital identification (ID) apps are increasingly gaining prominence all over the world, with many countries, especially Asian nation-states, having rolled out such apps or being in the midst of doing so (Ho, Reference Ho2021). In Europe, the electronic Identification, Authentication and Trust Services (eIDAS) provides a unified and common standard for electronic identification across the European Union (Tsakalakis et al., Reference Tsakalakis, O’Hara and Stalla-Bourdillon2016; European Commission, 2025), while the Modular Open Source Identity Platform (MOSIP) is being followed by 26 countries in the Global South (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Kim, Li, Burnett and Sarma2023; Connect, Reference Connect2025). As the United Nations Development Programme explains, national digital IDs are the means by which citizens can gain access to an official ID and allow for citizens to transact with both public and private sector actors (Handforth and Lee, Reference Handforth and Lee2022). More importantly, a World Bank report highlights how national digital IDs have an upsized role in enabling the “inclusive digital transformation of countries” (The World Bank, 2022). More crucially, many have begun to highlight the role of national digital IDs in including marginalized populations (Van der Straaten, Reference Van der Straaten2020; Yee Yen et al., Reference Yee Yen, Yeow and Wee Hong2022; Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Kim, Li, Burnett and Sarma2023).

Understood as a range of technologies, devices, and politics that enable the emergence of “citizenship platforms [which] facilitate virtual exchanges between government and the governed” (Athique and Goggin, Reference Athique and GogginForthcoming), national digital IDs lie at the critical intersections of disability, technology, and policy. Understanding these intersections is key in the ongoing turn to digital society and digital transactions, which have wide-ranging implications (but also can create new possibilities), especially pertaining to disabled people’s citizenship and inclusion (as well as exclusion) in nation-states where they reside (Goggin et al., Reference Goggin, Hawkins and Schokman2024; van Toorn and Cox, Reference van Toorn and Cox2024).

Here, we note that digital transactions are an important aspect of digital societies for several key reasons. As Athique and Goggin (Forthcoming) highlight, there are a range of transactions that take place digitally across various platforms, such as banking and payment, beyond national digital IDs. This is unsurprising, given how most transactions that take place digitally tend to be financial in nature. In the UK, for instance, the implementation of Open Banking has supported the abilities of institutions to verify recipients’ identities, simplifying the complex nature of digital financial transactions but also presenting new problems in terms of accessibility (Balkan, Reference Balkan2021; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Murinde, Mcgarrell, Arun, Goel, Kostov, Sethi and Markose2024; Clarke and Macartney, Reference Clarke and Macartney2025). More crucially, a key part of the move to the digital, however, has been the optimism that digital transactions can drive financial inclusion for marginalized groups (World Bank, 2024).

As with all new forms of digital transactions, there can be problems. For instance, when ATMs were first introduced (Goggin and Newell, Reference Goggin and Newell2007), its design presented key challenges to disabled people. Crucially, disability and digital inclusion remains largely understudied across Asia (Goggin et al., Reference Goggin, Ford, Martin, Webb, Vromen, Weatherall, Athique and Baulch2019). In Asia and the Pacific, this has had significant implications for disabled people, given that they number more than 650 million and comprise about one in six of the total population (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2017). In other words, national ID apps can also create disabling barriers for particular segments of the population, even though they may serve to enable citizen–government interactions.

Amidst this broader transformation of society, the Singpass app, a government app that enables the verification of Singapore citizens’ and residents’ digital identity and enables them to transact with government, private businesses, and agencies in the nation-state, offers an exemplary entryway into the issues at stake for digital inclusion. This is especially so, given how national ID apps are increasingly becoming used globally, specifically in countries such as Estonia, India, Sweden, Australia, and many others (McClune, Reference McClune2025). The centrality of the Singpass app in mediating social relations (or more precisely, government-to-people relations) in Singapore cannot be denied. From its inception in 2003 as a web-based programme (Salim, Reference Salim2021) to the ubiquitous use of its app today, Singpass has grown to be a key tool by which the government transacts with its citizens—all Singapore government webpages and services rely on the use of Singpass as a key form of authentication, as well as some private corporates, notably major banks. As a key platform mediating digital everyday lives in Singapore, the national digital ID sees more than 41 million transactions made through the app every month, with 4.2 million users who are connected to more than 2,700 services through the Singpass app (Singpass, 2023).

With an explicit focus on inclusive design led by the Singapore government, Singpass presents a pertinent case study to understand digital inclusion in policy and practice, especially amidst the broader focus on achieving inclusion for disabled people signalled by the passing of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The Singpass website proclaims the app’s three key design principles, namely safe and secure data; trusted ecosystem of partners; and inclusive design for all residents [emphasis ours] (Singpass, 2023). As the Singpass team explains on their blog, thought and effort were made in ensuring the mobile application and its experience were “seamless and more inclusive” especially for disabled populations. This is highly important, given how designing for disability can also streamline processes for non-disabled populations, supporting key aspects such as user experience and usability of digital transactions.

In this paper, we offer a discussion of the Singpass app and its implications for understanding inclusion. We first situate this discussion amidst the broader transformation of society, in particular one focused on the use of digital means to mediate how citizens interact with governments. In this instance, and given the widespread adoption of digital apps as the basis for citizen–government transactions, who is included and/or excluded is thus key to understanding what kinds of populations are considered as full participating citizens in society. As our theoretical framework, we adopt the concept of “smart equality,” which highlights the ways that disability can provide important insights into inclusion and design. We situate Singpass within the broader context of global regimes of disability rights policies and digital accessibility standards, highlighting the importance of context in the implementation of international standards of accessibility, rather than strict adherence to guidelines and standards. Importantly, we note that these broader international regimes are often seen as the standard to aspire to; however, as we highlight through the case of Singpass, it is also important to pay attention to local understandings and variations of inclusion. We then conclude by reiterating key insights from our analysis of Singpass to inform existing understandings of digital inclusion.

Our analysis is based on a corpus of publicly available sources around digital inclusion in Singapore and internationally, drawing primarily from websites, guidelines, and documents on policies and accessibility standards. The analysis is also informed by a wider study that includes three focus group discussions with 12 participants, comprising non-disabled app developers at GovTech Singapore and disabled user-testers of the app, all visually impaired users who have deep knowledge of the Singpass app. In addition, Victor and Bella have had longstanding involvement in and with the disability sector and community in Singapore.

2. Policy context: Global regimes of disability rights and digital accessibility

National digital ID apps have emerged in a context where disability inclusion is now an important facet of contemporary life. Across Asia and the Pacific, great attention and emphasis have been placed on both disability rights and digital inclusion. This is encapsulated by global instruments such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Jakarta Declaration on the Asian and Pacific Decade of Persons with Disabilities 2023–2032. In particular, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities represents the key milestone where disability rights are coded into international discourse (Degener, Reference Degener2016).

The accessibility of information and communication technologies (ICTs) is central to these policy instruments. Regional initiatives like the Incheon Strategy (UNESCAP, 2012) and the ASEAN Enabling Masterplan (ASEAN, 2019) put forth key recommendations to support the development of inclusive ICTs for persons with disability, while Article 9 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities highlights that state parties have obligations to ensure equal access to ICTs and systems (United Nations General Assembly, 2007). International non-governmental organizations, such as the Global Initiative for Inclusive Infocomm Technologies (G3ict) (G3ict, 2023), the International Association of Accessibility Professionals (IAAP), Web Accessibility in Mind (WebAIM), and the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), as well as corporates like Level Access and DigitalA11Y, have been heavily involved in the translation of these international goals into practice (Peri, Reference Peri2025).

More crucially, the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Southeast Asian contexts, as Cogburn (Reference Cogburn, Cogburn and Reuter2017) points out, represents an important step in addressing the “grand challenge” of disability rights. Importantly, Reuter and Cogburn (Reference Reuter, Cogburn, Cogburn and Reuter2017) highlight how the signing and ratification of the Convention allowed for “a common basis as a starting point for disability rights implementation”; however, actual implementation is still uneven across Southeast Asian nation-states (Cogburn, Reference Cogburn, Cogburn and Reuter2017, p. 271).

Such a perspective is particularly relevant—Singapore has signed and ratified the Convention, yet as scholars have pointed out, how inclusion functions in Singapore is vastly different from these international norms and standards, given how the Singapore state has steadfastly refused the passing of any disability rights legislation (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Zhuang, Goggin, Wong, Robinson and Fisher2023). This is despite the enacting of the Enabling Masterplans, a series of state-led roadmaps to chart out the steps needed to take towards inclusion, first implemented in 2007 and now in its fourth edition covering 2022–2030. The state of affairs in Singapore can be characterized as a pervasive reliance on medicalized notions of disability together with a focus on communitarianism, where family and society are encouraged to take the first step in supporting disabled people (Zhuang, Reference Zhuang2016), rather than the use of disability rights law or legislation. Notably, when it comes to ICTs, there are still pressing issues to be addressed for disabled people to gain full access to information in digital spaces (Tan and Zhuang, Reference Tan and Zhuang2025).

Beyond the Convention, there are also established regimes for digital inclusion when it comes to disability. Central to establishing the standards for digital accessibility, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) has been fundamental in setting standards and guidelines with its Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), now at version 2.2. While geared towards making web content accessible, WCAG also provides guidance for building accessible mobile apps. In a document published in 2015 drawing from version 2.0, the W3C highlights 17 accessibility considerations based on the four principles of WCAG—perceivable, robust, open, understandable, and robust (w3c, 2015), including considerations such as “zoom/magnification,” “contrast,” “consistent layout,” “providing easy methods for data entry,” among others.

The 17 listed considerations are, however, a subset of the range of criteria that can be considered. The latest reiteration of the WCAG, version 2.2 (w3c, 2023), highlights how both web content and mobile apps should aim to comply with its various considerations and success criteria (of which there are now 86). However, the accessibility of apps is not a main focus of WCAG, and as a result, there have been differences in how the guidelines have been interpreted for accessibility for apps. Consequently, a range of accessibility guidelines have also been developed by Apple and Google; yet these guidelines may differ between apps and also app stores (Ballantyne et al., Reference Ballantyne, Jha, Jacobsen, Hawker and El-Glaly2018; Yan and Ramachandran, Reference Yan and Ramachandran2019), highlighting the subjective nature of accessibility standards and guidelines.

There are, however, numerous problems with simply relying on the WCAG as the standard frame of reference. As DeNardis (Reference DeNardis2010, p. 133) writes, standards are political—they operate at a technical level and embed particular values and norms that reflect the interests of those who create the standards. Ellcessor (Reference Ellcessor2010) points out that while the development of web accessibility standards embedded in the WCAG is critical in creating a more accessible internet, these standards are also based on particular understandings of accessibility. As Ellcessor (Reference Ellcessor2010) explains, the WCAG was developed as a guideline and based on notions of human variation; it is unable to retain such focus on human variability when translated into a legal standard, which requires compliance to fixed notions of what a disabled body is. Notwithstanding this, various institutions and agencies globally (audioeye, 2024; Level Access, 2022; UK Government, 2023) have highlighted the importance of using the four principles of WCAG—perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust—as starting points for understanding and measuring accessibility.

A key discussion and point of concern has also been how the WCAG exports minority world standards, issues, and concerns to other global contexts. Lewthwaite and Swan (Reference Lewthwaite, Swan and Meloncon2013), p. 157) note that while the development of WCAG provides key impetus for global web accessibility, these standards “fail to account for disability as a socio-cultural product dependent on any given context.” Importantly, disability standards, evident in the WCAG, are built and geared towards minority world contexts and do not take into account issues across majority world contexts, in particular concerns by local disabled populations (Lewthwaite and Swan, Reference Lewthwaite, Swan and Meloncon2013). For instance, questions of literacy are not accounted for in the WCAG, and there is a keen focus on issues that concern wealthy disabled consumers rather than disabled people who may require basic access to basic resources such as water and housing. Summing up, Lewthwaite (Reference Lewthwaite2014, p. 1377) notes how these standards do not understand disability as “one amongst multiple and inter-related identities and indices of disadvantage.”

There is thus an urgent need to develop nuanced understandings of accessibility within local contexts, especially outside of minority world contexts. In the case of Singapore, these international frameworks for disability rights and digital inclusion are replicated (and referenced), but in very different ways. Despite signing and ratifying the Convention, notions of disability rights are seemingly disavowed in the Singapore context (Zhuang, Reference Zhuang2023). As Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Zhuang, Goggin, Wong, Robinson and Fisher2023) highlight, inclusion focuses on implementing practical measures such as the building of physical infrastructure like lifts and ramps. The same goes for questions of the digital, where the focus is on practical goals, rather than on affirming rights.

This divergence takes on added impetus when we turn to understand the adoption of technology in Singapore society. As a young nation-state celebrating 59 years of independence in 2024, Singapore has seen rapid economic growth, industrialization, and urbanization in its transformation from third world to first (Lee, Reference Lee2000). Its rapid development has also seen Singapore become one of the most digitally connected societies. In 2023, the Infocomm Media Development Authority in its digital society report highlighted that 99% of resident households are connected to the internet, with 97% of residents owning smartphones and the mobile penetration rate at 166.1% (Infocomm Media Development Authority, 2024a, 2024b).

Yet, the question of digital participation for marginalized groups is still very much unaddressed, especially for disabled persons. As Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Sun, Pang, Lim, Soh and Pakianathan2021) highlight, disadvantaged groups in Singapore (namely students from low-income households, seniors, low-income adults) continue to face barriers to digital access, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, while little is known about the experiences of disabled communities. Indeed, disabled people continue to face exclusionary barriers across other offline/non-digital domains of public life (Hong, Reference Hong2022; Choo, Reference Choo, Zhuang, Wong and Goodley2023; Zhuang et al., Reference Zhuang, Wong and Goodley2023; Tan and Ho, Reference Tan and Ho2025). Given the ubiquity of its use in everyday life in Singapore, Singpass thus presents a key platform to understand everyday experiences of digital inclusion and accessibility.

3. Theoretical framing: disability perspective on digital inclusion

We position our work as a case study to examine the usefulness of existing global accessibility standards, drawing from perspectives from disability studies and “smart equality” to demonstrate the importance of context in the implementation of international standards of accessibility, with a focus on the social affordances that apps like Singpass afford to its disabled users.

Our conceptual framework for this paper builds on the concept of “smart equality,” which highlights how “digital inclusion can build on disability as the organizing principle in order to reimagine digital infrastructure” (Goggin and Zhuang, Reference Goggin, Zhuang and Tsatsou2022, p. 262), particularly in areas such as digital relationships and transactions. As Goggin and Zhuang explain, rather than seeing digital inclusion from the perspective of guidelines, compliance, and regulation (or the lack thereof, which is nonetheless important), smart equality draws attention to how disability can offer new opportunities and possibilities (as well as insights) for policy, design, and implementation (among others). To do so is to focus on the structures that disability is embedded within. In the case of Singpass, smart equality asks that we consider how disability can instead be the basis for inclusion, rather than simply its object of study and/or governance.

We also note that disability studies, which have been built from the advent of the disability rights movement globally from the 1970s, have led to a transformation of how disability is understood in contemporary societies. A key analytical frame offered by disability studies has been to examine the social structures that inhibit our worlds and which continue to pose barriers to disabled peoples’ participation and obstruct their emancipation (Oliver, Reference Oliver1996). In other words, while we focus on smart equality, we are also cognizant of the possible problems that may be present, in terms of both structural barriers that may pre-exist and those that are embedded within its development, and also current problems and issues.

A disability perspective is critical in shaping our understanding of digital inclusion. As an analytical lens, disability allows us, as Goodley (Reference Goodley2016, p. 156) highlights, “to think through a host of political, theoretical and practical issues that are relevant to all.” Such a frame pivots to disability as a generative form of knowledge and embodiment, rather than simply the object of charity, welfare, or pity. Doing so also shifts the attention from what disability is to how disability is understood in contemporary societies. This is pertinent in understanding technologies, as disability can provide “a rich and indispensable site and ‘test bed’ for how societies can confront technology for better futures” (Goggin et al. Reference Goggin, Ellis and Hawkins2019, p. 298).

In centring disability in our analysis, we seek to understand the kinds of affordances technology can provide for disabled people in mediating social relations. Explaining, Hutchby (Reference Hutchby2001, p. 444) notes that affordances “are functional and relational aspects which frame, while not determining, the possibilities for agentic action in relation to an object.” Understanding how technology—in this case, inclusive apps—can provide key affordances thus turns attention to the ways in which technology enables but also the limitations on the actions that users can or cannot take (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins, Friese, Rebane, Nolden and Schreiter2016).

Yet, affordances are not simply neutral devices, but can also be embedded within problematic socio-economic contexts. As Arseli Dokumaci writes, disabled people do improvise their environments to make their own worlds more liveable (Dokumaci, Reference Dokumaci2023); this also includes digital environments. Centring disability in the digital can thus provide key insights into the workings of technology, especially when mobilized and deployed by disabled people or when designed with disability in mind (Hamraie and Fritsch, Reference Hamraie and Fritsch2019), providing new affordances for world-making (Dokumaci, Reference Dokumaci2023). This emphasizes how lived experiences of disability can be a form of generative knowledge with important lessons for design, both digital and otherwise (Pullin, Reference Pullin2009; Hendren, Reference Hendren2020).

Earlier disability studies research on technologies have elucidated the complex relationship between disability and technology, where emerging technologies can be both beneficial and problematic for disabled populations. One key example is Roulstone’s (Reference Roulstone1998) discussion of how technologies—such as keyboards, mouse, and in today’s context, zoom technology—come to be adopted for workplaces and the benefits these adoptions can provide for disabled people. More recently, the (re)emergence and accelerated uptake of artificial intelligence reflect this paradoxical relationship between disability and technology. While the deployment of artificial intelligence can create new possibilities—enabling and supporting disabled people at work, it can also create new problems (Zhuang and Goggin, Reference Zhuang and Goggin2024).

More broadly, scholars have highlighted the inherent biases embedded within the normative visions of emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (Whittaker et al., Reference Whittaker, Alper, Bennett, Hendren, Kaziunas, Mills, Morris, Rankin, Rogers and Salas2019). A broad range of other scholars have also critiqued and spotlighted the inequalities and problems that continue to exist for disabled people and the digital across a spate of global locations (Dobransky and Hargittai, Reference Dobransky and Hargittai2016; Goggin, Reference Goggin, Ragnedda and Muschert2017; Hargittai, Reference Hargittai2022). Importantly, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated some of these transformations that have had impacts (some beneficial, but also negative) on disabled people. As Hargittai (Reference Hargittai2022) highlights, while technological adoption during the pandemic has led to new forms of work and sociality, some of which have benefits for disabled people (like remote and flexible work), disabled people are still very much disadvantaged when it comes to digital connectivity.

As a form of government-led technology, national digital ID apps present a unique case to understand the intersections of disability, technology, and policy. These apps function as information systems for governance (and also surveillance) as they allow for the recognition of one’s identity and allow access to services in their nation-states/jurisdiction, while reducing identification to data and rules (Lyon, Reference Lyon2009). When it comes to access, Hayes de Kalaf and Fernandes (Reference Fernandes2023) note how national ID systems can also systemically exclude by design and deny people access to important services.

Others have also highlighted how such systems can present problems to the populations they purportedly are designed for, especially when they are unable to access or use the systems as they are designed (Park and Humphry, Reference Park and Humphry2019; Chudnovsky and Peeters, Reference Chudnovsky and Peeters2022; Okunoye, Reference Okunoye2022; Sperfeldt, Reference Sperfeldt2023). While digital ID systems may pose problems, Gelb and Metz (Reference Gelb and Metz2018), citing the case of India, are more optimistic in noting how they may also provide the catalyst for sustainable development and equality, noting that such systems may allow access to much-needed services. Similarly, Banerjee (Reference Banerjee2016) highlights the various affordances the Aadhaar, India’s digital ID system, provides for digital inclusion. Yet, the question remains: How would national digital ID apps look like if they centre disability in designing for inclusion?

4. Accessibility of Singpass

First launched as a national ID system in 2003, the introduction of the app version in October 2018 marked a significant milestone. In his landmark study on the operations of mobile apps, Goggin (Reference Goggin2021, pp. 2–Reference Athique and Goggin3) highlights how apps “provide bridges across the messy ecologies of media, technology, environments, and bodies” and bring together a range of technologies, software, and hardware, ranging from the mobile web and internet to phones and software development, and also technologies such as biometric and so on. In doing so, apps provide key affordances—for instance, to access social media and entry into digital society.

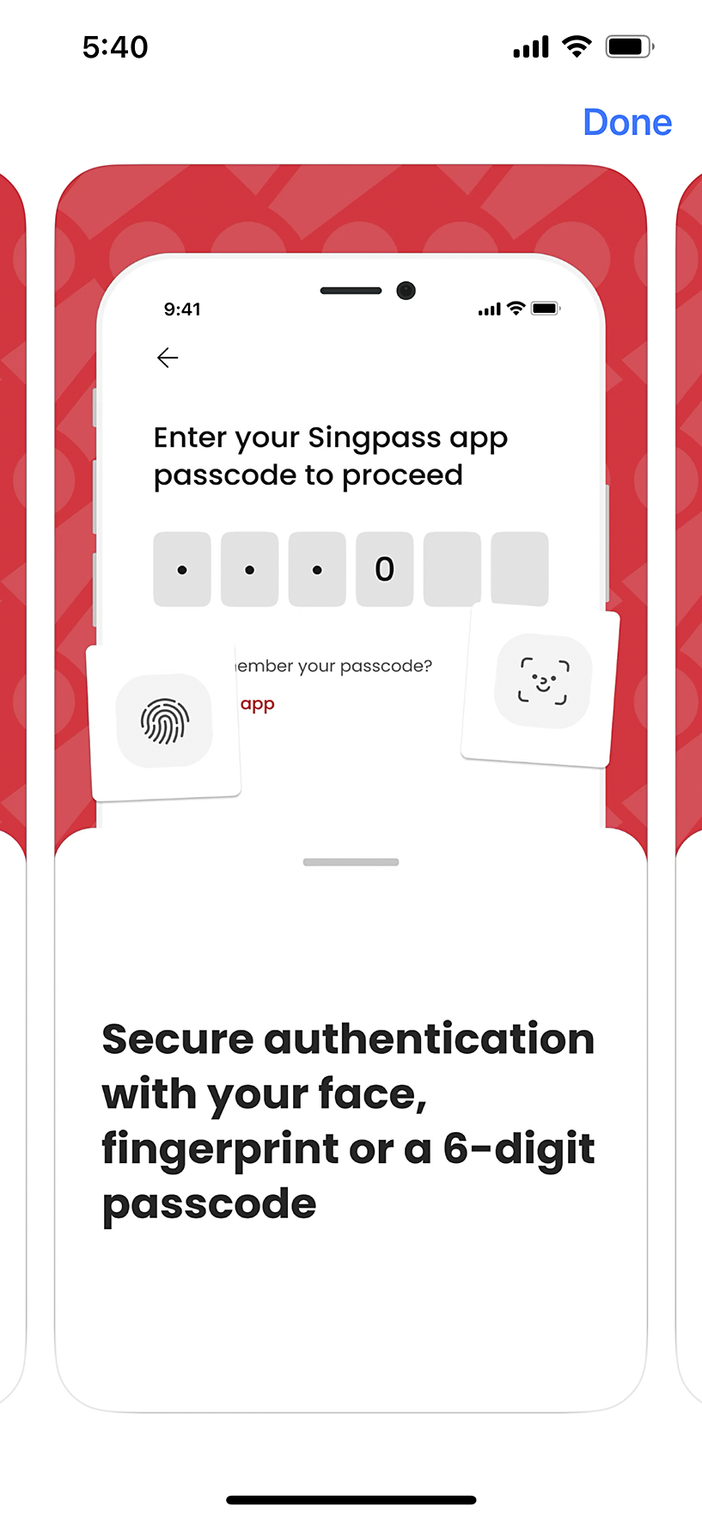

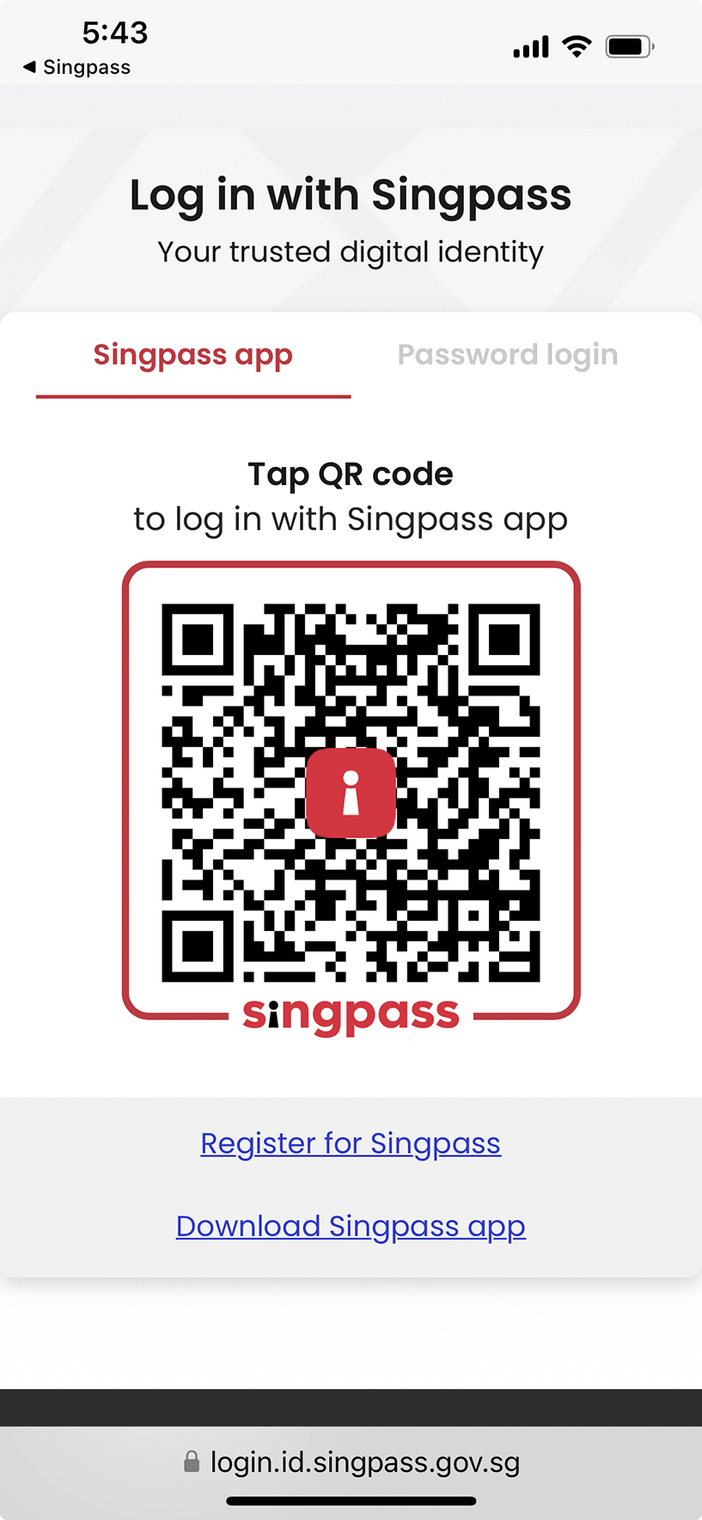

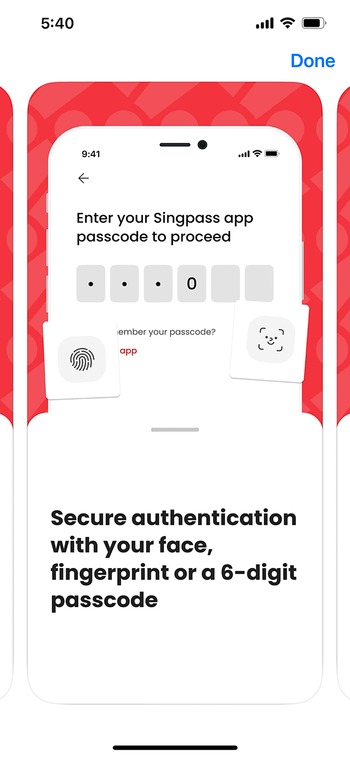

It is precisely within this confluence of media and communication technologies that the Singpass app operates. A brief discussion of how the Singpass app operates would be useful. First of all, the use of the app’s functions requires the use of facial, fingerprint, or six-digit passcode authentication as a security measure (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screenshot of the Singpass app on the App Store describing various authentication methods.

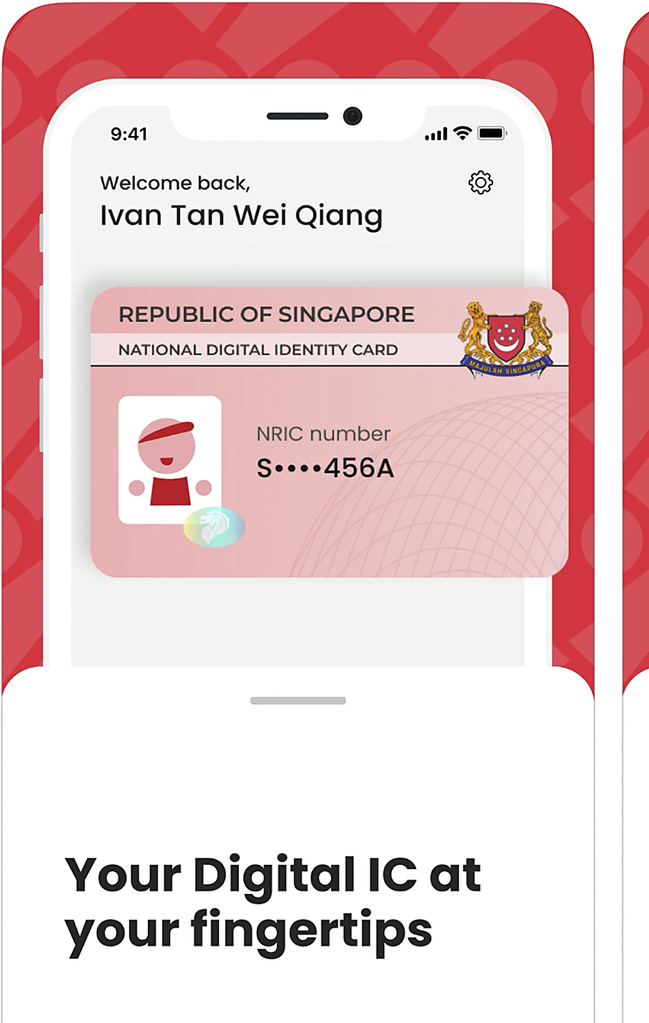

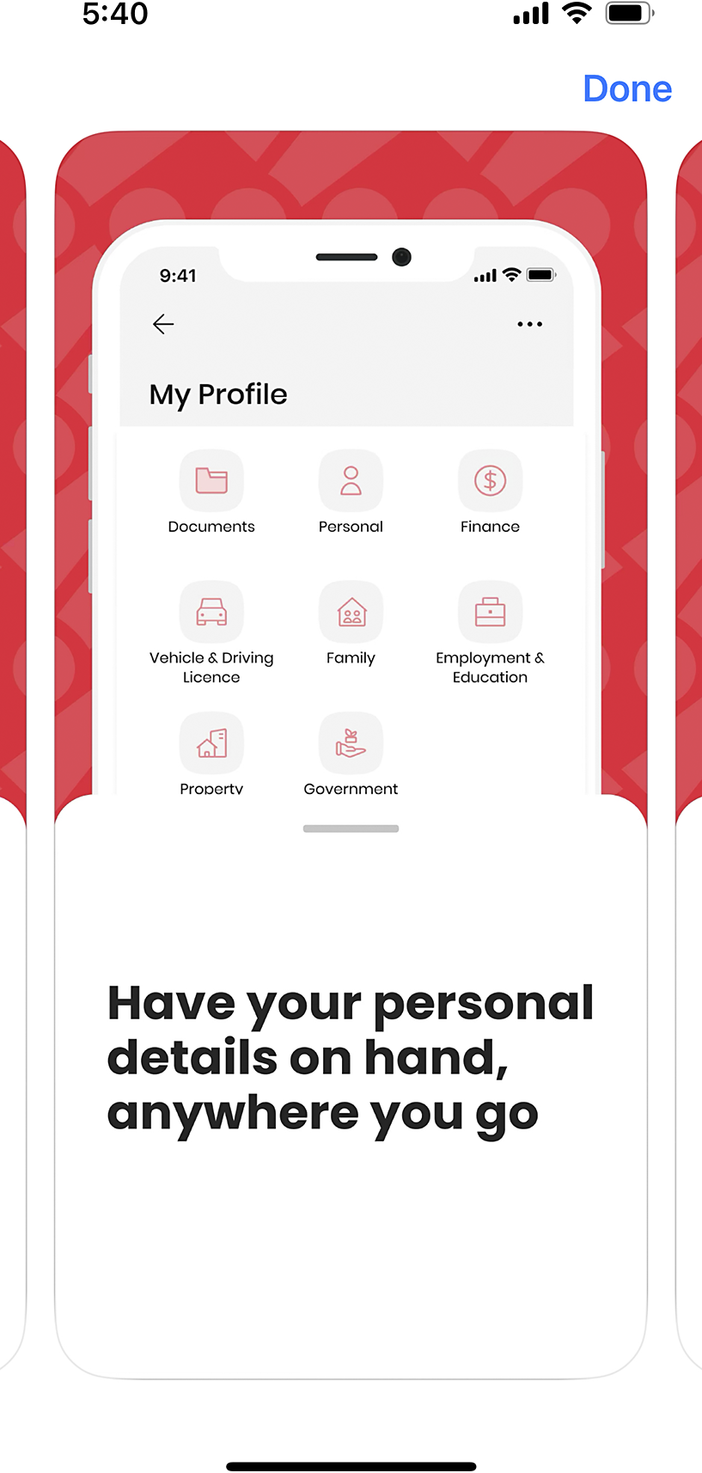

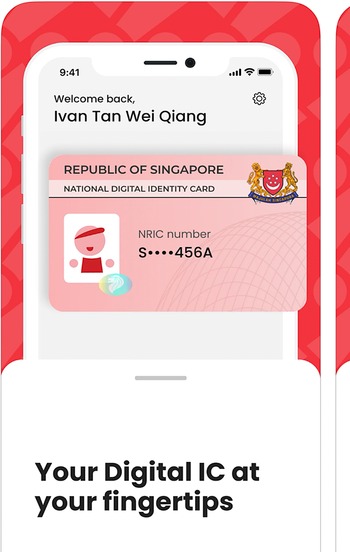

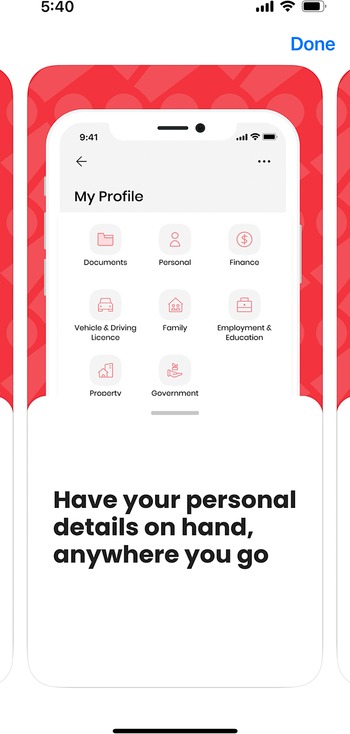

Upon entry, the user is able to access different functions. One key function is the provision of digital identification (Figure 2) and the consolidation of personal information from different government agencies, including financial, driving, family, employment, education, property, and other government information and documents (Figure 3). Users can also receive government notifications and digitally sign official documents without having to make in-person visits.

Figure 2. Screenshot of the Singpass app on the App Store, illustrating national identity documents on Singpass.

Figure 3. Screenshot of the Singpass app on the App Store showing different categories of official documents available on Singpass.

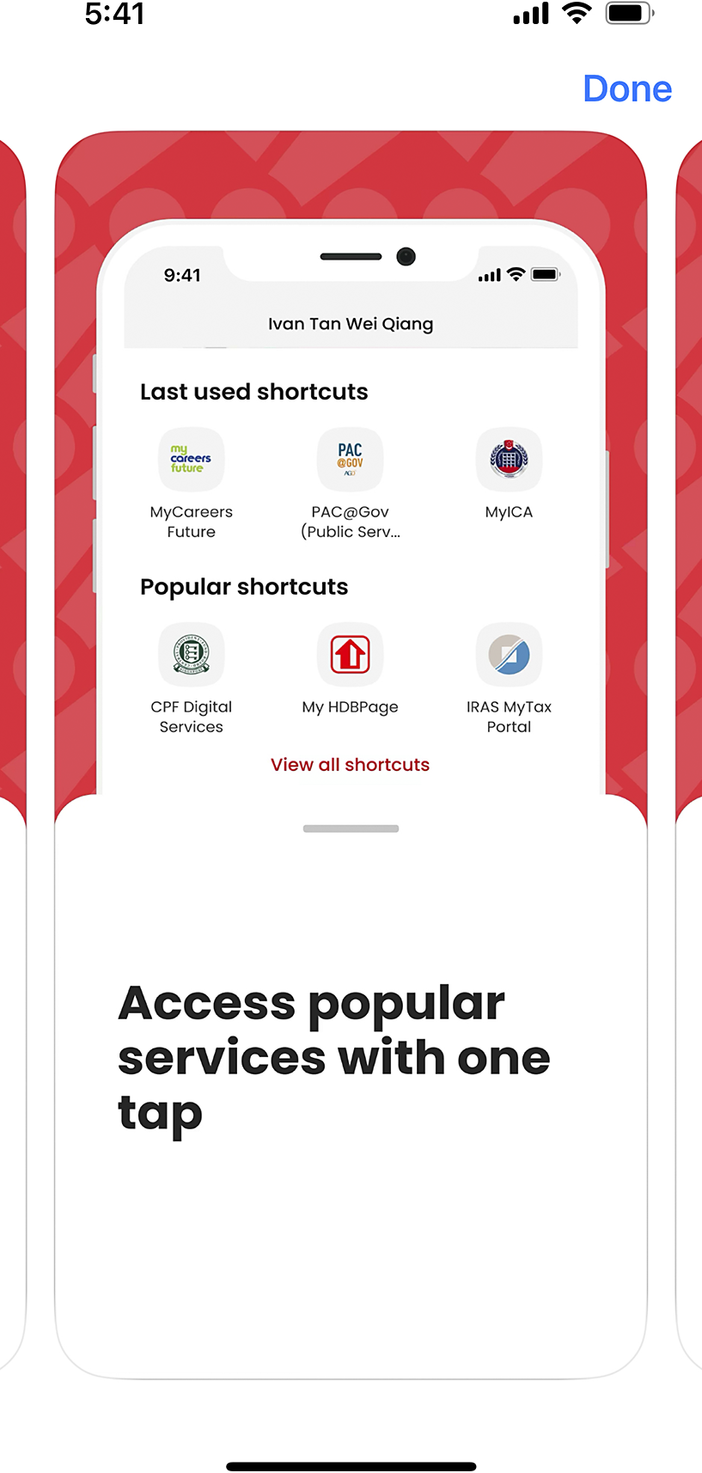

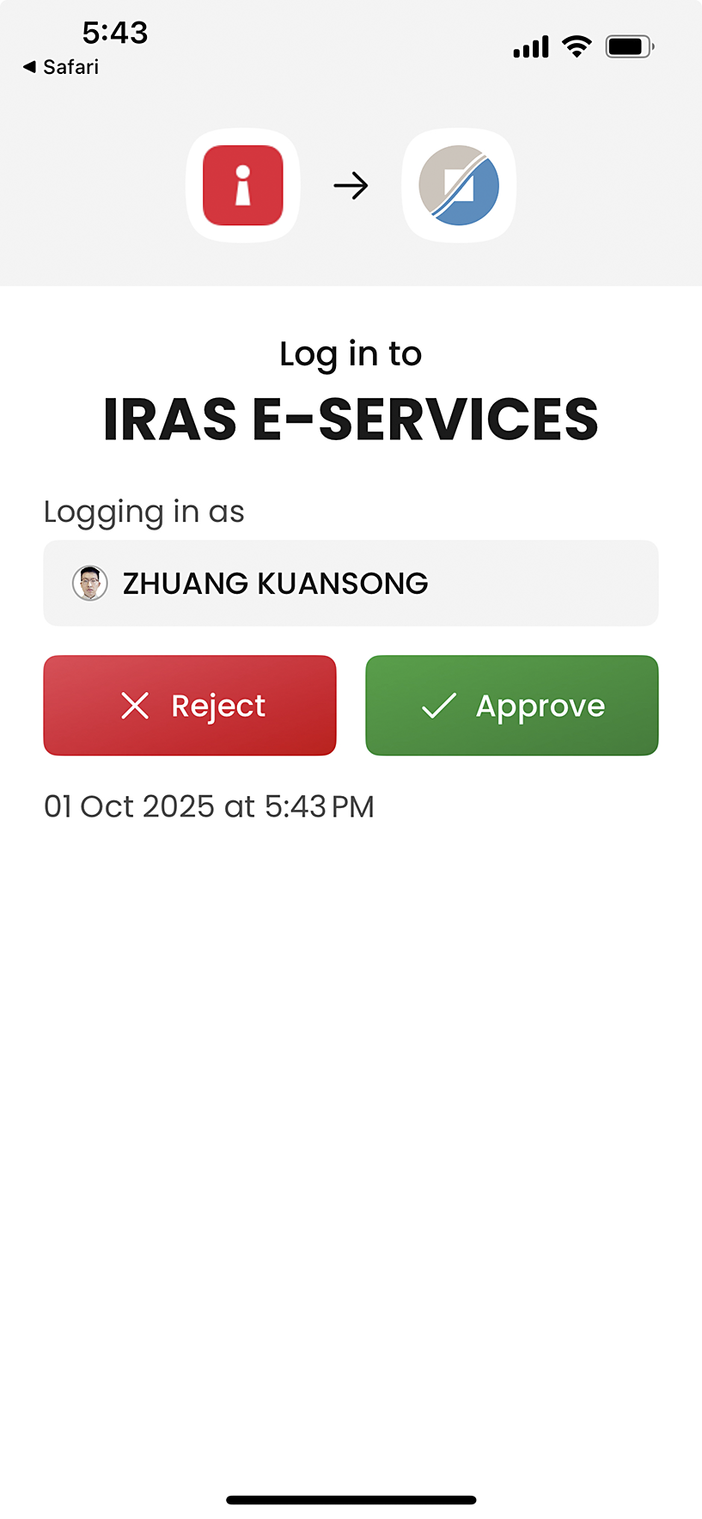

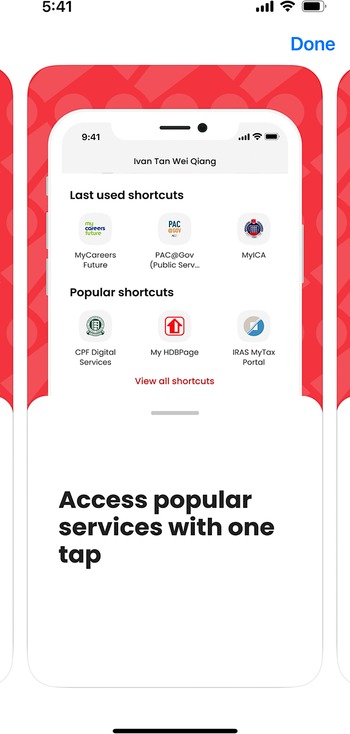

Another primary function of Singpass is to provide access to all online government services, such as the IRAS MyTax portal for any tax-related services (Figure 4). In this case, upon authentication, users will be directed to the IRAS MyTax portal on their mobile browser. Alternatively, users can also access tax services directly from the respective government service portal on their mobile device, tablet, or computer. Upon clicking on the logon button on the tax portal, they would be directed first of all to a webpage that offers two ways of logging in—one, a QR code that allows one to log in with the app and two, password login (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Screenshot of the Singpass app on the App Store, featuring key shortcuts to different government service portals.

Figure 5. Screenshot of the Singpass app showing a QR code that allows users to verify their identity for government services through the app.

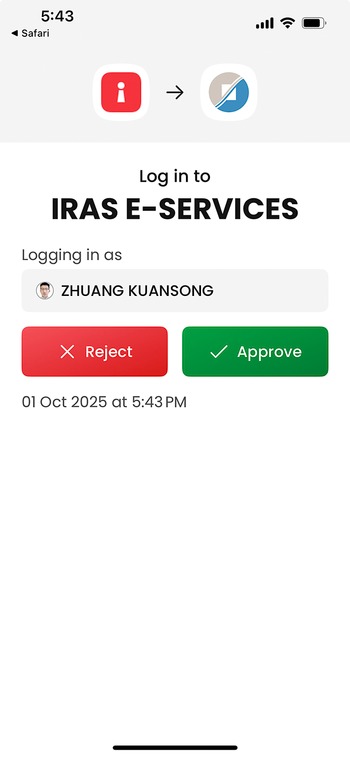

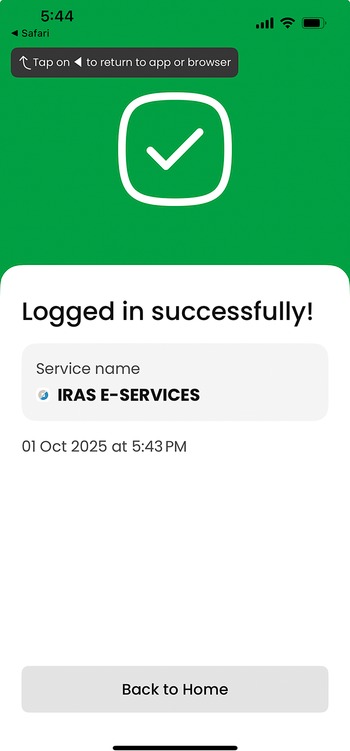

Clicking on the QR code redirects to the Singpass app (presumably installed on the same mobile device), where the user can choose to approve or reject the request (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Screenshot of the Singpass app. The user is then asked to approve or reject the authentication request via the app.

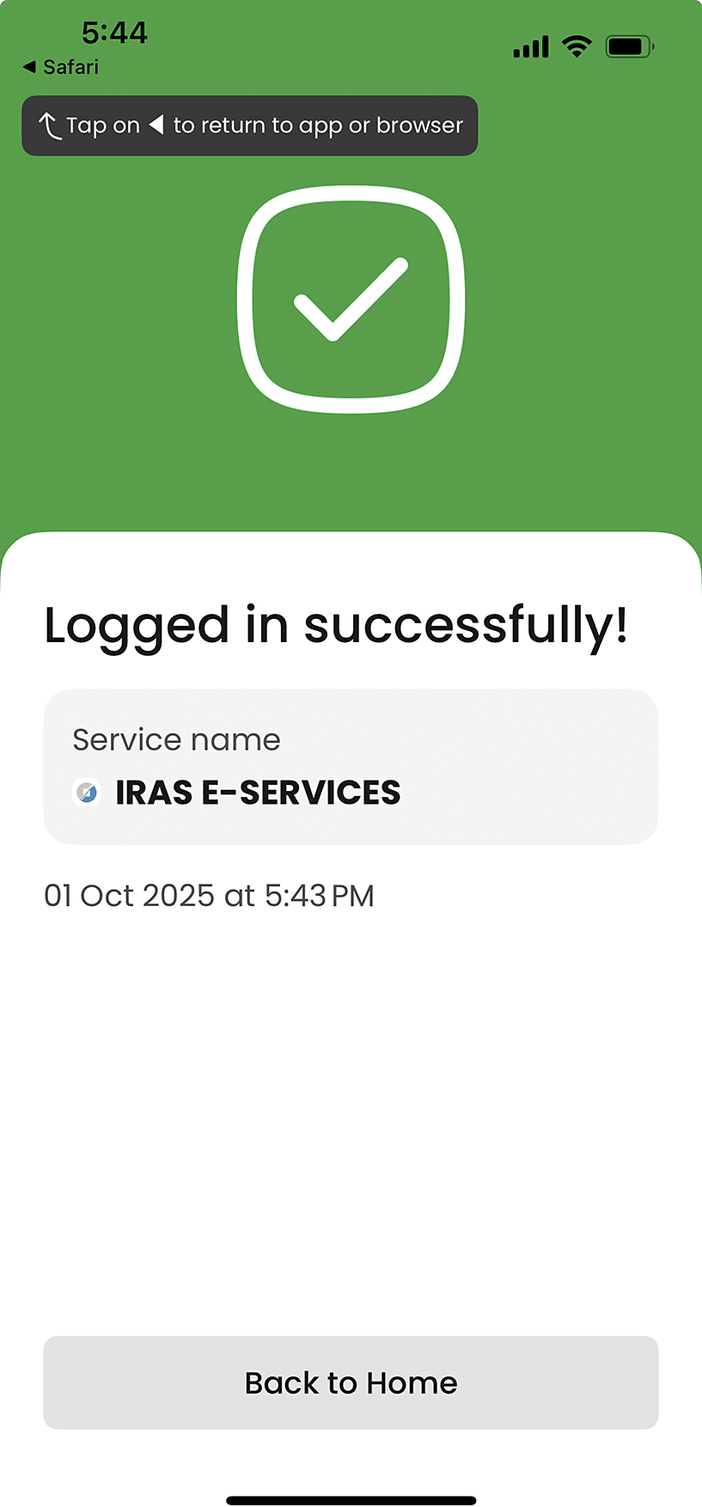

Upon clicking the “approve” button, the mobile device will authenticate the user. In this instance, an Apple iPhone 13 uses face ID to biometrically authenticate the user (the user may also use other forms of authentication, including but not limited to inputting the Singpass app passcode if biometrics are not recognized and/or the use of SMS one-time password for two-factor authentication). Upon successful authentication, the user may then return to their initial logon page by clicking on the link for the browser (see Figure 7). Importantly, depending on the browser and systems used (desktop/mobile), the user experience for authentication may differ slightly.

Figure 7. Image showing the mobile screen after successful authentication and login. The user is required to click on the link on the screen to return to the app or browser.

This description of the logon and authentication process serves as an entryway into the processes, ecosystems, and technologies that are embedded and also entangled within the Singpass app. Importantly, in this process, we highlight the confluence of different forms of media and technology. What is immediately recognizable are mobile internet and broadband service, web, phone hardware such as camera and sensors, biometric face and/or fingerprint recognition, and short messaging service. Other forms of technology and features may be available, but not quite recognizable. As our respondents highlight, this includes the development of accessibility in smartphones such as voiceover, assistive touch buttons, among others, which have allowed key affordances for disabled users in using and navigating the app and its ecosystem.

Crucially, the app offers connectivity not just with a whole range of services that interface with not only government agencies but select corporate entities. Beyond authentication, the user can also e-sign documents, receive important notifications from government agencies in their app inbox, pre-fill digital forms, and display digital IDs, providing a one-stop accessible interface for government-to-people transactions and moving away from physical interfaces and providing ease of connection to both disabled and non-disabled populations. As GovTech explains, the key reason why the Singpass app was built this way was to allow for a wide diversity of user experience and to allow for a more inclusive app (GovTech, 2024).

What this highlights is that disability can provide generative insights for design and benefit a larger segment of society.

5. Localization of policy and standards for digital inclusion

We turn to examine how Singpass as technology interprets both the international and local policy contexts within which it is embedded. As a key technological product of the government, the Singpass app reflects broader moves towards building an inclusive society in Singapore. The Enabling Masterplan, as we introduced earlier, sets out the contours of how inclusion can be achieved specifically for disabled persons. In the fourth edition from 2022 to 2030, it notes specifically that all high-traffic government websites will be accessible by 2030, in contrast to the 61% in 2022 (Ministry of Social and Family Development, 2022, p. 152). However, we also note that most of the discussion of technology in the Masterplans tends towards notions of technology as assistive devices that are meant and used towards enabling disabled people to achieve full productivity (Goggin and Zhuang, Reference Goggin, Zhuang and Tsatsou2022), presenting a limited understanding of digital inclusion for disabled persons (Scully, Reference Scully2025).

More broadly, digital inclusion policies in Singapore extend beyond simply focusing on disabled individuals, but also on other segments of the population. As the Ministry of Digital Development and Information highlights, there are two key aspects to building a safe and inclusive digital society—digital access, referring to connectivity and the devices for participation; and digital literacy and skills, referring to people’s abilities to be able to use technology (Ministry of Digital Development and Information, 2025a). With reference to this, the Infocomm Media Development Authority has developed a digital readiness blueprint that lays out how Singapore should undertake the development of a digital society (Ministry of Communications and Information, 2018). In defining digital readiness, it notes the importance of ensuring digital access, literacy, and participation for all Singaporeans, laying out the following key principles:

-

• Every Singaporean has the means to transact digitally;

-

• Every Singaporean has the skills, confidence, and motivation to use technology;

-

• Every Singaporean makes use of technology to achieve a better quality of life; and

-

• Every digital product or service is designed for easy and intuitive use by all Singaporeans (Ministry of Communications and Information, 2018, p. 10).

More crucially, the blueprint highlights the importance of inclusion by design—that products and services are “designed for easy and intuitive use by all Singaporeans” (Ministry of Communications and Information, 2018, p. 13). The blueprint notes the importance of user-centric design for the goals of universal inclusion so that “almost everybody can participate and transact digitally with little or no instruction” (Ministry of Communications and Information, 2018, p. 11). Among its various recommendations, we note that it highlights the need to ensure access in vernacular languages and also that access is customized for those with “special needs” (Ministry of Communications and Information, 2018, p. 13).

This focus on digital inclusion takes on added impetus when we examine more recent developments, in particular at the Committee of Supply debates of 2025, when the Ministry of Digital Development and Information announced that the “Government’s current Digital Service Standards (DSS) will be enhanced to provide better guidance to agencies in making digital services accessible to persons with disabilities” (Ministry of Digital Development and Information, 2025b). Explaining, it notes that the Digital Services Standards takes reference from the WCAG; at the same time, it spotlights tools that it has developed, namely Oobee, to be used for accessibility checking (Ministry of Digital Development and Information, 2025b). The Standards were developed and launched in October 2018 by the same agency—GovTech—that developed the Singpass app, and the app was thus developed in adherence to the Standards. To explain how user-centric services can be developed, the Standards were created by seeking insights from all sectors, including citizens, businesses, and government agencies, with reference to the WCAG and other standards, such as the Singapore Standard 618 on designing for older adults (Singapore Government Developer Portal, 2024).

While there is a revised edition of the Digital Services Standards updated in July 2020, we focus on the original version, given that it coincides with the launch of the Singpass app. Across the original Standards, it lays out some 56 standards that government agencies need to meet to achieve across three different principles—intuitive design and usability; accessibility and inclusivity; and relevance and consistency (we note this has been reduced to some 34 standards in the revised edition) (GovTech, 2018).

Of particular relevance is Section 1, which focuses on intuitive design and usability—highlighting the need for digital services to be universally designed. It notes that “transactional services shall be easily discoverable (within 2 clicks from homepage/home screen) and viewable by user without prior login and be featured prominently” (GovTech, 2018, p. Standard 1.4); consistent navigation (GovTech, 2018, p. standard 1.7); use of standard sans serif font with a minimum base font size of 16 CSS pixels with the size to be adjustable (GovTech, 2018, p. Standard 1.15); and mandating the use of “Myinfo,” which draws on Singpass data (and login) to prefill and auto-populate key information for government form filling (GovTech, 2018, p. Standard 1.23). Notably, the use of “Myinfo” reduces the need for users to fill in personal details already captured by government databases and reduces errors in form filling. We also spotlight Standard 2.5 in Section 2 on Accessibility and Inclusivity, which states that “All web-based digital services shall be offered in English. Additional languages should be offered to better serve the target users if required” (GovTech, 2018, p. Standard 2.5). We note that of these standards highlighted, Standards 1.4, 1.15 and 1.23 are either not discussed in WCAG or far exceeds that listed in WCAG, even in its latest iteration version 2.2. The WCAG, for instance, does not put forth any recommendation on font type or font size, even though others have highlighted this as a form of best practice (Bureau of Internet Accessibility, 2023).

Discussion of the usability and user experience of Singpass, however, extends beyond accessibility for disabled people but also for the general population. Many have highlighted how usability and user experience cover areas such as user-engagement, effectiveness and efficiency of the mobile interface and process, error tolerance, users’ ease of learning, and others (Díaz-Bossini and Moreno, Reference Díaz-Bossini and Moreno2014; Interactive Design Foundation, 2025; Punchoojit and Hongwarittorrn, Reference Punchoojit and Hongwarittorrn2017; Sharp, Reference Sharp2003). In-app accessibility is a huge focus of Singpass design with clear and efficient authentication processes; our respondents did not find issues with Singpass’s authentication process and found it straightforward and intuitive. Singpass developers also took great lengths to explain their desire to ensure processes were designed to support in-app user experiences. Notably, in the second edition of the Digital Services Standards published in 2020, intuitive design and usability took centre stage, with some 16 standards highlighting the need that government digital services “must be well designed so that citizens and businesses can interact and transact with us digitally in an intuitive and easy to use manner” (GovTech, 2020, pp. 8–15); there are also additional guidelines on consistency across government websites, adding on to the focus on accessibility in the first edition.

While our respondents found the Singpass app easy to use and intuitive, with clear indications of the process, we note, however, that this did not extend to inter-app switching. As we show in Figure 7, once the authentication process is completed, users have to manually switch to the original browser/app that the authentication process was initiated from by clicking at the top left corner of their mobile screens. In the voiceover mode, the link to their original browser/app would be the first element encountered, providing visually impaired users with ease of access in switching apps. As the developers of Singpass tell us, this is a key constraint of app switching in both Apple and Android systems and is an important element to prevent background hacking of information. The implication here is that user experiences, in the streamlining of processes between different apps and systems (i.e. the initial transaction and the Singpass authentication process), are mediated by developer guidelines on data protection and privacy.

Furthermore, Singpass developers mentioned how accessibility guidelines by both Apple and Google were also followed in building the app. As the user testers we spoke with suggested, this has resulted in numerous features within the app that are built for accessibility (GovTech, 2022, 2024) such as text contrast, text size, and other features embedded within accessibility in iOS and Android systems. In adhering to these guidelines developed in a North American context, the Singpass app may well conform to the contextual standards and norms within which these guidelines are embedded —in particular, the Americans with Disabilities Act, as well as other associated laws such as Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act.

However, as we have highlighted earlier in the discussion on the Digital Services Standards, there are local variations that are discussed and which Singapore-designed government digital services need to comply with. The developers of Singpass accounted for local variations and demands for digital inclusion and sought to incorporate accessibility issues present in local contexts. One specific example is the inclusion of a feature that allows users to choose between the four official languages of Singapore (English, Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil), given that not all of the population are literate in English. Hence, we note that what may be considered as central for inclusivity in apps for Singapore is dependent also on contextual factors and may be different from what is set out in the WCAG or Section 508, highlighting the need to recognize technologies as productive interpretations of both international and local policy contexts. Here, we note that instead of restricting our perspective of digital inclusion to guidelines, compliance, and regulation (or the lack thereof), disability, as a generative insight that focuses on the disabling structures around us, can offer new opportunities and possibilities for inclusion in itself.

6. Towards digital inclusion: key intersections of disability, technology, and policy

Digital media is central to society today (Couldry et al., Reference Couldry, Rodriguez, Bolin, Cohen, Goggin, Kraidy, Iwabuchi, Lee, Qiu, Volkmer, Wasserman, Zhao, Koltsova, Rakhmani, Rincón, Magallanes-Blanco and Thomas2018), more so given how transactions are increasingly taking place in digital forms. Understanding digital inclusion is thus pertinent now more than ever, where a disability perspective is key. In this paper, we have argued that the key to building inclusive digital societies lies at the intersections of disability, technology, and policy. As demonstrated through the case of Singpass, centring disability as a form of knowledge affords new ways of rethinking digital inclusion, raising key implications for existing global regimes of digital inclusion and accessibility. How national ID apps are designed is thus important, given how accessibility affects not only disabled populations but also the usability and user experiences of non-disabled people.

While policies and standards serve as useful tools to establish safeguards for accessibility, these international frameworks need to be situated within local contexts, and understandings of digital inclusion need to go beyond standards and policies. Smart equality spotlights the importance of drawing on disability to examine the underpinning structures that disabled people are embedded within, which can also serve as a means to generate new knowledge of achieving digital inclusion. The Singapore context thus serves as a useful counterpoint to dominant narratives of how inclusion can and should happen and the kinds of practices that it may entail. In analysing the policy context within which Singpass is embedded, we posit the importance of understanding Singapore’s pursuit of inclusion, which differs sharply from that in many other policy contexts, possessing key lessons for dominant understandings of digital inclusion developed largely from legal frameworks in minority world contexts. In so doing, we posit the necessity for global policymaking to recognize the processes of localization of disability rights legislation and accessibility standards.

Understanding the complex interactions between disability, technology, and policy highlights how the adoption of disability as an “organising principle” can afford new ways of reimagining digital inclusion for research, policy, and technology (Goggin and Zhuang, Reference Goggin, Zhuang and Tsatsou2022, p. 262). Without centring disability, especially how it is understood and lived in local contexts, rather than simply as perceived within foreign or global frameworks, our understandings and practices of digital inclusion remain exclusionary and problematic.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the public data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Data that support the findings from the focus group discussions are available from the corresponding author, subject to ethics restrictions. The data are not publicly available due to information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: K.V.Z., B.C., G.G., F.T.C.T.; Data curation: B.C.; Formal analysis: K.V.Z., B.C., C.S.L., F.T.C.T.; Funding acquisition: K.V.Z., G.G., C.S.L.; Investigation: K.V.Z., F.T.C.T., R.L.; Methodology: K.V.Z., B.C., G.G., C.S.L., F.T.C.T., R.L.; Project administration: K.V.Z., B.C.; Resources: K.V.Z., F.T.C.T.; Supervision: C.S.L.; Writing—original draft: K.V.Z.; Writing—review and editing: K.V.Z., B.C., G.G., C.S.L., F.T.C.T., R.L.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Nanyang Technological University under a CoHASS Incentive Grant Scheme IGS-02-2024. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.