Recent literature shows that emotions are vital for understanding the success of populist radical right parties. While anger seems particularly relevant (e.g., Rico et al., Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017; Widmann, Reference Widmann2021), another increasingly studied emotion is nostalgia. The focus on nostalgia – a ‘sentimental longing for one's past’ (Sedikides & Wildschut, Reference Sedikides and Wildschut2017, p. 1) – is not surprising, given that pledges to Make America Great Again or Take Back Control proved politically successful. Interestingly, nostalgic experiences are not limited to radical right voters, and nostalgic rhetoric is used by politicians of various camps (e.g., Jobson & Wickham‐Jones, Reference Jobson and Wickham‐Jones2010; Robertson, Reference Robertson1988).

However, the emotion seems particularly relevant among populist radical right parties, that is, parties that embrace populist, authoritarian and nativist elements (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007). Hence, a growing body of literature documents populists’ nostalgic rhetoric (e.g., Elgenius & Rydgren, Reference Elgenius and Rydgren2022), nostalgia's changes over time (Heath et al., Reference Heath, Richards and Jungblut2022) or its link to acculturation preferences (Smeekes & Jetten, Reference Smeekes and Jetten2019) and radical right ideology (De Vries & Hoffmann, Reference De Vries and Hoffmann2018; Smeekes et al., Reference Smeekes, Wildschut and Sedikides2021). Experimental evidence by Van Prooijen and colleagues (Reference Van Prooijen, Rosema, Chemke‐Dreyfus, Trikaliti and Hormigo2022) shows that people become more nostalgic after populist, compared to pluralist, rhetoric.

Despite these important contributions, the question abides why nostalgia is particularly relevant in motivating radical right support. The fact that large shares of society regularly experience nostalgia (Hepper et al., Reference Hepper, Wildschut, Sedikides, Ritchie, Yung, Hansen and Zhou2014; Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Sedikides, Arndt and Routledge2006) suggests that underlying mechanisms explain why nostalgia – and which contents of it specifically – relates to radical right support.

In this paper, I address this question with three contributions. First, I theorize why nostalgia motivates support for this ideology by positioning relative deprivation as a mediator. Relative deprivation research (e.g., Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Christ, Wagner, Meertens, Van Dick and Zick2008; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Pettigrew, Pippin and Bialosiewicz2011) suggests that individuals can feel relatively disadvantaged when comparing their own or their group's situation to a subjectively chosen, potentially biased reference, such as other individuals, groups or their past. When nostalgic, individuals long for a rose‐coloured past that they memorize as positive but bygone (Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Sedikides, Arndt and Routledge2006). I argue that this makes them automatically compare the present and past and results in feelings of relative deprivation. Thus, nostalgia creates an ambitious reference to which some individuals think society's present cannot live up to, even if it does in objective terms. In turn, individuals react to this temporal relative deprivation by supporting parties that pledge to restore the favourable past, such as the radical right.

Second, I refine the relative deprivation argument by theorizing distinct relationships for different nostalgia contents. Previous literature shows that individuals are nostalgic for various things (Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014), such as personal childhood memories or group‐based accounts of a bygone, golden‐era society. Based on my argument that nostalgia inherently makes individuals compare past and present, I posit that the current societal crises make group‐based nostalgic individuals feel that society is worse off than in the past. In contrast, as personal nostalgia helps individuals to find meaning (Routledge et al., Reference Routledge, Arndt, Wildschut, Sedikides, Hart, Juhl, Vingerhoets and Schlotz2011; Sedikides & Wildschut, Reference Sedikides and Wildschut2017), longing for the personal past does not result in a similar conclusion about one's personal situation.

With this distinction, I build on previous literature distinguishing sociotropic (i.e., society‐based) from egotropic (i.e., personal) voting motivations (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Kinder & Kiewiet, Reference Kinder and Kiewiet1981). If personal memories, like childhood experiences, drive the effects, this would suggest that radical right support is a consequence of personal grievances. In contrast, if societal memories, like former values, are more relevant, this would support theories explaining radical right support as societal dissatisfaction (see Mutz, Reference Mutz2018; Rico & Anduiza, Reference Rico and Anduiza2019; Steenvoorden & Harteveld, Reference Steenvoorden and Harteveld2018). I postulate that group‐based nostalgia creates group‐based relative deprivation because it makes people feel that the societal present is worse than its past. Instead, personal nostalgia does not evoke personal relative deprivation because it helps to find meaning in one's present life (Routledge et al., Reference Routledge, Arndt, Wildschut, Sedikides, Hart, Juhl, Vingerhoets and Schlotz2011; Sedikides & Wildschut, Reference Sedikides and Wildschut2017). Support for this argument would fit recent literature suggesting that sociotropic concerns steer political behaviour more than personal ones (Abdallah, Reference Abdallah2022; Solodoch, Reference Solodoch2021).

Third, I use nationally representative panel data from the Netherlands to examine the prevalence and contents of nostalgia, their relation to radical right support and the relative deprivation argument. The data have two merits. First, they allow me to quantitatively map the prevalence of various nostalgia contents, which, compared to previous work differentiating personal and group‐based nostalgia (e.g., Van Prooijen et al., Reference Van Prooijen, Rosema, Chemke‐Dreyfus, Trikaliti and Hormigo2022), is more detailed and derived from a representative sample. Second, compared to previous cross‐sectional analyses on the relationship between nostalgia and radical right support (e.g., De Vries & Hoffmann, Reference De Vries and Hoffmann2018; Smeekes et al., Reference Smeekes, Wildschut and Sedikides2021), the panel design facilitates better causal conclusions. This is vital, given that the nostalgic rhetoric of radical right elites (e.g., Elgenius & Rydgren, Reference Elgenius and Rydgren2022) may also spark nostalgia. Likewise, nostalgia and radical right voting may be consequences of omitted variables. Arguably, panel data cannot keep up with experimental designs’ causal evidence (e.g., Van Prooijen et al., Reference Van Prooijen, Rosema, Chemke‐Dreyfus, Trikaliti and Hormigo2022). Nevertheless, combining a large, representative sample with various control variables and fixed‐effect regressions with clustered standard errors, reduce the risks of omitted variable bias and selection effects better than cross‐sectional designs. I find that group‐based but not personal nostalgia is associated with radical right support. Moreover, group‐based but not personal relative deprivation mediates this relationship. I consider the Netherlands a likely case for studying the relationship between nostalgia and radical right support in Western Europe.

Nostalgia

While nostalgia was historically considered a negative, home‐sickness‐like experience, recent evidence describes it as an emotion bearing sad and joyful feelings when thinking about the past (see Sedikides et al., Reference Sedikides, Wildschut, Stephan, Forgas and Baumeister2018 for a review). People experiencing nostalgia feel the pleasure of joyous times and the pain that these times are gone, making the emotion bittersweet. Contrasting present and past, individuals perceive themselves in a bigger picture, which may help them make sense of themselves and find purpose in life (Routledge et al., Reference Routledge, Arndt, Wildschut, Sedikides, Hart, Juhl, Vingerhoets and Schlotz2011; Sedikides & Wildschut, Reference Sedikides and Wildschut2017). Even if nostalgia sometimes hurts, it facilitates coping by strengthening social connectedness, self‐esteem, optimism and goal‐oriented behaviour (Sedikides et al., Reference Sedikides, Wildschut, Stephan, Forgas and Baumeister2018). Nostalgia is experienced by large shares of society, across cultures (Hepper et al., Reference Hepper, Wildschut, Sedikides, Ritchie, Yung, Hansen and Zhou2014) and often several times a week (Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Sedikides, Arndt and Routledge2006), which contradicts the portrayal of radical right voters as a unique circle of backward‐looking people.

But nostalgia is not limited to personal experiences. Consistent with intergroup emotions theory's (Mackie et al., Reference Mackie, Devos and Smith2000) suggestion that individuals experience emotions based on the group they identify with, individuals feel nostalgic about personal and group‐based memoirs. Group‐based Footnote 1nostalgia describes a longing for a past that ‘is contingent upon thinking of oneself in terms of a particular social identity or as a member of a particular group’ (Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014, p. 845). For example, individuals identifying with their country may feel nostalgic for how the country has been in the past.

The distinction between personal and group‐based nostalgia matters because they have distinct effects on attitudes and behaviour. While personal nostalgia primarily evokes effects on an individual level (e.g., Sedikides et al., Reference Sedikides, Wildschut, Stephan, Forgas and Baumeister2018), group‐based nostalgia is primarily related to group‐level consequences, such as ingroup‐support intentions (Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014) or outgroup animosity (e.g., Smeekes, Reference Smeekes2015; Smeekes et al., Reference Smeekes, Verkuyten and Martinovic2014). Furthermore, while group‐based nostalgia becomes more relevant when individuals strongly identify with a group (Smeekes (Reference Smeekes2015), Wildschut et al. (Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014) finds that personal nostalgia is unrelated to group identity.

These differential effects have theoretical and empirical implications. Theoretically, they suggest that group‐level outcomes like radical right voting are mostly related to group‐based but not personal nostalgia. Hence, the mechanism underlying this relationship needs to have a group‐based rather than a personal focus. Empirically, the relevance of group identity for group‐based nostalgia requires that analyses of its relationship with radical right support include respective control variables. As national identity is related to group‐based nostalgia (Smeekes, Reference Smeekes2015; Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014) and radical right support (e.g., Filsinger et al., Reference Filsinger, Wamsler, Erhardt and Freitag2020), it is a possible confounder. To illustrate, an individual's membership in a group makes them experience group‐based nostalgia, and their membership in a native group more specifically motivates their vote for a radical right party (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007).

Nostalgia and populist radical right support

Amid rising radical right parties in Western democracies, scholars have invested considerable efforts in studying emotions in an electorate depicted as left behind (e.g., Jennings & Stoker, Reference Jennings and Stoker2016) or globalization losers (e.g., Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). However, it remains unclear what emotion characterizes this sensation of being left behind best (see Obradović et al., Reference Obradović, Power and Sheehy‐Skeffington2020 for a review). While Hochschild (Reference Hochschild2016) pinpoints anger and mourning among the radical right, others (e.g., Capelos & Katsanidou, Reference Capelos and Katsanidou2018; Salmela & von Scheve, Reference Salmela and von Scheve2017) argue for a more complex dynamic of various emotions. Capelos and Katsanidou (Reference Capelos and Katsanidou2018) summarize ‘anger, fear, nostalgic hope, betrayal and a sense of perceived injustice’ (p. 1272) as resentment, an emotion underlying reactionary politics. Some in this line of research highlight nostalgia's relevance within this emotional blending more explicitly (Jennings & Stoker, Reference Jennings and Stoker2016; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2021).

While populist politicians’ rhetoric suggests that support for this ideology is a function of many emotions (Widmann, Reference Widmann2021, but see Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Rooduijn and Bakker2022), it is important to acknowledge that single emotions have different action tendencies (Frijda et al., Reference Frijda, Kuipers and Ter Schure1989) that, studied in isolation, help characterize voters’ emotional experience. Nostalgia, for instance, has at least two characteristics that differentiate it from the emotions mentioned aboveFootnote 2. First, while anger and resentment are mostly negative experiences, nostalgia is primarily positive and only partly negative (Hepper et al., Reference Hepper, Ritchie, Sedikides and Wildschut2012). As I will elaborate upon in the next section, this suggests that it may not be negative emotions per se that relate to radical right voting but the attitudes following an ambiguous emotion like nostalgia. Second, the ‘rose‐tinted’ (Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014, p. 844) experience of nostalgia explicitly emphasizes the subjectiveness with which individuals think about the past. Hence, even if the present is objectively better than the past, nostalgia may make people feel that the present is worse.

Empirically, a growing body of correlational and experimental evidence documents nostalgia's effects on intergroup relationships (Smeekes, Reference Smeekes2015; Smeekes et al., Reference Smeekes, Verkuyten and Martinovic2014; Smeekes et al., Reference Smeekes, Jetten, Verkuyten, Wohl, Jasinskaja‐Lahti, Ariyanto, Autin, Ayub, Badea, Besta, Butera, Costa‐Lopes, Cui, Fantini, Finchilescu, Gaertner, Gollwitzer, Gómez, González and Van Der Bles2018) and political attitudes (De Vries & Hoffmann, Reference De Vries and Hoffmann2018; Smeekes et al., Reference Smeekes, Wildschut and Sedikides2021; Van Prooijen et al., Reference Van Prooijen, Rosema, Chemke‐Dreyfus, Trikaliti and Hormigo2022). Although essential contributions, the current evidence mainly rests on general measures of nostalgia, cross‐sectional designs or convenience samples. Given the theoretically distinct effects of nostalgia (Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014), the risk of reverse causality (e.g., Elgenius & Rydgren, Reference Elgenius and Rydgren2022) and the prevalence of nostalgia in society (Hepper et al., Reference Hepper, Wildschut, Sedikides, Ritchie, Yung, Hansen and Zhou2014; Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Sedikides, Arndt and Routledge2006), it is vital to study the association between nostalgia and radical right support while accounting for these limitations.

Group‐based nostalgia evokes temporal relative deprivation

In this paper, I argue that temporal relative deprivation can explain why nostalgia is associated with radical right support and why these relationships depend on nostalgia's content. Relative deprivation is the ‘judgment that one is worse off compared to some standard accompanied by feelings of anger and resentment’ (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Pettigrew, Pippin and Bialosiewicz2011, p. 203). Thus, individuals feel relatively deprived if they compare themselves to a relevant referent and subjectively conclude that they are disadvantaged compared to that referent. Notably, the referent may be another individual, an outgroup or oneself at earlier times (Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Christ, Wagner, Meertens, Van Dick and Zick2008). Due to its subjectiveness, individuals can even feel relatively deprived if their current conditions are objectively equal to or even better than the past (Sengupta et al., Reference Sengupta, Osborne and Sibley2019).

When individuals feel nostalgic, I argue, their thoughts about the past automatically entail implicit comparisons to the present. If these comparisons result in the evaluation that one's present is worse than the past, nostalgia induces feelings of temporal relative deprivation. Notably, the subjectiveness of one's experience is at the core of both rose‐tinted nostalgia (Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014) and the evaluations that evoke temporal relative deprivation (Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Christ, Wagner, Meertens, Van Dick and Zick2008). Hence, I posit that nostalgia motivates radical right support because it leads to the evaluation that one's memorized past was better than the present.

However, I also posit that whether nostalgia evokes temporal relative deprivation depends on what one is nostalgic for. In the wake of climate change, economic crises and migration‐related demographic change, the societal past may appear subjectively better than the present to some individuals. Hence, group‐based nostalgia evokes the subjective evaluation that one's group's present is worse off than the past. In turn, this temporal group‐based relative deprivation motivates individuals to support an ideology that promises to restore old standards, the populist radical right.

In contrast, I argue that personal nostalgia does not evoke personal relative deprivation. Previous work has established that personal nostalgia helps individuals to find meaning in the present life, even in challenging times (Routledge et al., Reference Routledge, Arndt, Wildschut, Sedikides, Hart, Juhl, Vingerhoets and Schlotz2011; Sedikides & Wildschut, Reference Sedikides and Wildschut2017). Therefore, I posit that when people are nostalgic for their personal past, they still implicitly compare past and present as they do after group‐based nostalgia. However, given the meaning‐providing function of personal nostalgia, this comparison does not evoke the conclusion that the personal past was better than the present. Consequentially, people may evaluate their present as equal to or even better than the past, therefore not raising personal motivations to change one's situation through the populist radical right.

Regarding the relationship with radical right support, two studies suggest that temporal relative deprivation becomes politically relevant. First, Pettigrew and colleagues (Reference Pettigrew, Christ, Wagner, Meertens, Van Dick and Zick2008) assess whether the extent to which individuals feel that they or people like them are economically worse off than 5 years ago, predicts prejudice. They find that only the group‐based form of experienced disadvantage relates to the outcome. Second, Gest and colleagues (Reference Gest, Reny and Mayer2017) find that the feeling that one or people like oneself are less important, financially worse off and less politically influential than 30 years ago, is positively related to the radical rightFootnote 3.

As shown in Figure 1, I theorize that group‐based nostalgia evokes temporal group‐based relative deprivation, which then relates to radical right support. In contrast, although personal nostalgia similarly makes individuals compare past and present, this does not evoke temporal personal relative deprivation and, therefore, not more radical right support. The empirical section of this paper examines the differential effects of group‐based and personal nostalgia in two steps. Using representative data from the Netherlands, it first presents preregistered analyses of the argument that group‐based but not personal nostalgia is associated with stronger radical right support. Based on the literature reviewed above, I hypothesize that group‐based nostalgia is linked to a higher likelihood of supporting the Dutch radical right party Partij voor de Vrijheid (Party for Freedom, PVV).

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

Note: Feeling nostalgic makes one compare past and present. The result of this subjective evaluation is dissatisfaction on the group‐based level (i.e., temporal group‐based relative deprivation). Instead, personal nostalgia does not evoke dissatisfaction on the personal level (i.e., no temporal personal relative deprivation). Hence, group‐based but not personal nostalgia is associated with stronger radical right support.

-

H1: Group‐based nostalgia is positively associated ith the likelihood of voting for the radical right PVV.

However, given the social stigma around radical right voting (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Dahlberg, Kokkonen and van der Brug2019) and voters’ tactical expectations that mainstream parties will not form a coalition with the radical right (Van Spanje & Van Der Brug, Reference Van Spanje and Van Der Brug2007), some voters may not vote for the party even if they sympathize with them. Hence, I complement the first hypothesis with an additional outcome that assesses people's sympathy towards the radical right.

H2: Group‐based nostalgia is positively associated with liking the PVV and its leader Geert Wilders.

Finally, and for the same reasons as above, I test the relationship between group‐based nostalgia and conservatism. If this form of nostalgia makes people feel that the present is worse than the past, they should seek to conserve it and thus endorse more conservative attitudes.

H3: Group‐based nostalgia is positively associated with a more conservative ideology.

While the literature review and the group‐based relative deprivation argument provides clear expectations that sociotropic motivations (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Kinder & Kiewiet, Reference Kinder and Kiewiet1981) relate to radical right support, it does not raise firm expectations for egotropic motivations following personal nostalgia. Hence, I state no hypotheses for personal nostalgia.

In the second step of the analysis, I conduct exploratory mediation analysis to test the argument that group‐based but not personal nostalgia evokes temporal group‐based relative deprivation, which then relates to radical right support. I hypothesize:

EH1: The relationship between group‐based nostalgia and radical right voting is (partially) mediated through temporal group‐based relative deprivation.

I do not hypothesize such mediation for personal nostalgia.

The research context

I conduct preregisteredFootnote 4 analyses on representative data from the Netherlands, encompassing the years 2011–2016. While the availability of representative panel data with fine‐grained measures of nostalgia is the primary reason to study this case, Zaslove and colleagues (Reference Zaslove, Geurkink, Jacobs and Akkerman2020) provide additional ones. First, the Netherlands has strong populist parties. After the radical right List Pim Fortuijn – which attained results as strong as 17 per cent in general elections – had burst over internal conflicts, its electorate moved towards the 2006‐founded PVV. Geert Wilders led the party to strong results in the highly fractionalized party system. In the 2017 general election, they came in second with 13.1 per cent of the votes. The party mobilizes with populist, authoritarian and nativist appeals and is categorized as radical right under the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES; Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022). Moreover, the PVV uses nostalgic rhetoric (Kešić et al., Reference Kešić, Frenkel, Speelman and Duyvendak2022). For example, Wilders promised to bring back the life of ‘Henk and Ingrid’, a fictional Dutch couple that is considered a stereotype of the good Netherlands. Living as a heteronormative couple in a suburb with their child and a car, Henk and Ingrid are seen as what Dutch society used to be (Müller & Dobbert, Reference Müller and Dobbert2017).

Second, Zaslove and colleagues (Reference Zaslove, Geurkink, Jacobs and Akkerman2020) argue that the Netherlands has not experienced fundamentally different developments from other Western European countries, such that the effects of economic crises and migration resembled those seen in neighbouring countries. While this would suggest that results from the Dutch context may be generalizable across Western Europe, the Netherlands has some unique characteristics. Among others, they have several successful radical right parties with different programs and organizations (De Jonge, Reference De Jonge2021), which compete against many other parties.

Regarding nostalgia, it is also important to note that European countries define nationhood differently as ethnic or civic. If longing for society's past alludes to ethnic homogeneity, the relationship between group‐based nostalgia and radical right nativism becomes more apparent than when individuals long for civic values. While Ariely (Reference Ariely2012) operationalizes the Dutch conception as a combination of civic and ethnic elements, the conception likely became more ethnic following the so‐called 2015 migration crisis. Smeekes and colleagues (Reference Smeekes, Wildschut and Sedikides2021) invigorate this assumption when finding that an ethnic conception of nationhood partially mediates the relationship between national nostalgia and outgroup prejudice in the Netherlands. Furthermore, Lubbers and Smeekes (Reference Lubbers and Smeekes2022) find that Dutch radical right voters are more likely than other voters to take pride in the nation's history and that this pattern is similar in other European countries.

Together, I consider this a likely case, such that the Netherlands has several established radical right parties. Yet, while several features of this case are comparable to other Western democracies, the generalizability to other countries remains limited. For example, nostalgia may have a different relevance in Eastern European countries, where citizens were socialized in a different political system (Ekman & Linde, Reference Ekman and Linde2005).

Research design and participants

I analyze data from the Dutch Longitudinal Internet studies for the Social Sciences (LISS; Tilburg University, the Netherlands). Since 2007, the LISS Panel follows about 7,500 Dutch citizens drawn by true probability sampling from the population register. This form of sampling allows generalizing findings from the sample to its target population, the Dutch society. As radical right support varies across demographic subgroups (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), representative samples matter because they reduce the risk that findings are solely due to selection effects. Panel members complete monthly online questionnaires covering a range of issues in about 10–15 minutes. Participants without internet access receive the respective equipment to participate. The response rate (50—80 per cent) varies by month and questionnaire, and the attrition rate is about 12 per cent per year. Four refreshment samples were added to the initial sample to account for attrition and complement the representation of underrepresented groups (see here for more information).

I analyze data from waves collected between 2011 and 2016 (see Supporting Information S1 in the Supporting Information for all measures). These data include detailed nostalgia items, allowing me to differentiate between group‐based and personal nostalgia and, therefore, study what respondents felt particularly nostalgic about and how these contents were associated with radical right support. As shown in Supporting Information S2, the sample's demographic background (N = 10,413) was 50.88 per cent female, had a mean age of M = 40.81 years (SD = 20.02) and a gross median household income of M = 4125.90€ (SD = 2525.34€). Almost half (48.96 per cent) lived in ‘moderately’ or ‘very’ urban areas.

Measures

Nostalgia

I operationalize nostalgia as an independent variable, measured four times between November 2012 and March 2014. Drawing from Batcho's (Reference Batcho1995) nostalgia inventory, 20 items assess nostalgic contents (see Supporting Information S1). This variety of content provides two levels of detail. First, rather than just assessing the extent to which respondents were nostalgic, it differentiates between group‐based and personal nostalgia. Second, it details what respondents particularly long for. While two items are specifically about society (‘the way people were’, ‘the way society was’), the remaining 18 cover a range of personal nostalgia contents (e.g., family, vacation, childhood toys); all were rated 1 (Not at all nostalgic) – 7 (Very nostalgic). To test the differential effects of group‐based and personal nostalgia, I summarize them into separate indices. While the two group‐based nostalgia items resemble operationalizations in previous research (e.g., Smeekes, Reference Smeekes2015; Smeekes et al., Reference Smeekes, Verkuyten and Martinovic2014; Van Prooijen et al., Reference Van Prooijen, Rosema, Chemke‐Dreyfus, Trikaliti and Hormigo2022), a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the R‐package lavaan (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012) show that the differentiation into two group‐based (α ≥ 0.86) and 18 personal nostalgia (α ≥ 0.94) items is appropriate (CFI = 0.954, TLI = 0.946, RMSEA = 0.09, 95%‐CI [0.08; 0.09]). Additionally, to gauge the prevalence of nostalgia in general, I analyze one item, asking, ‘Specifically, how often do you bring to mind nostalgic experiences?’ (1 [Once or twice a year] – 7 [At least once a day]).

Radical right support

I operationalize three outcome variables, measured four times between December 2011 and January 2016. First, I dichotomize radical right vote propensity (‘If parliamentary elections were held today, for which party would you vote?’; 1 [PVV], 0 [Other]). Second, I operationalize party and politician liking with one item asking how much one liked the PVV and Geert Wilders, respectively (0 [Very unsympathetic] – 10 [Very sympathetic]). To condense the results, I integrate these two in an index of radical right liking (α ≥ 0.94). The organization of the PVV is tailored to Geert Wilders (De Jonge, Reference De Jonge2021), which suggests that sympathy towards the party and its candidate are strongly related. Third, I operationalize conservatism with one item asking, ‘Where would you place yourself on the scale below, where 0 means left and 10 means right?’ (0 [Left] – 10 [Right]). As this measure is quite broad and the left‐right placement of radical right parties remains debated for the economic dimension (De Lange, Reference De Lange and Mudde2016; Zaslove, Reference Zaslove2009), I additionally assess economic and cultural conservatism. These are measured as support for increasing income differences (1 [Differences in income should decrease] – 5 [Differences in income should increase]) and migrants’ cultural adaptation (1 [Immigrants can retain their own culture] – 5 [Immigrants should adapt entirely to Dutch culture]).

Mediators

For the exploratory mediation analysis, I operationalize group‐based and personal relative deprivation. For the former, I assess government satisfaction, asking, ‘How satisfied are you with the way in which the following institutions operate in the Netherlands? The Government’ (0 [Very dissatisfied] – 10 [Very satisfied]). For the latter, I operationalize personal satisfaction, reading, ‘If you imagine a “ladder of life”, where the first step represents the worst possible life, and the tenth (top) step the best possible life, on what step would you place yourself?’ (0 [Worst] – 10 [Best]). Both items were assessed four times during the time frame of interest.

Control variables

I control for seven demographic background variables: gender (male, female, other), age (continuous), highest education, occupation status, gross household income, origin (Dutch or other) and place of residence (1 [Extremely urban] – 5 [Not urban]). Furthermore, I control for some time‐varying variables that could potentially affect nostalgia and radical right support. First, I control for national identity. As reviewed above, national nostalgia is related to group‐based nostalgia (Smeekes, Reference Smeekes2015; Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Bruder, Robertson, van Tilburg and Sedikides2014) and radical right support (e.g., Filsinger et al., Reference Filsinger, Wamsler, Erhardt and Freitag2020). I compute an index of three items (e.g., ‘I really feel connected to other Dutch people.’; α ≥ 0.85; 1 [Disagree entirely] to 5 [Agree entirely]), which were measured twice in the studied period.

In supplementary analyses, I also control for personality and personal trust. As personality is related to both nostalgia (Stefaniak et al., Reference Stefaniak, Wohl, Blais and Pruysers2022) and political orientation (e.g., Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Schumacher and Rooduijn2021), stable personality traits may underlie any relationships between the two. Therefore, it is essential to account for people's personality characteristics. Following Gallego and Pardos‐Prado (Reference Gallego and Pardos‐Prado2014), I summarize 50 personality items from the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP, Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Johnson, Eber, Hogan, Ashton, Cloninger and Gough2006) into the five personality dimensions (10 items per dimension): extraversion (α ≥ 0.85), agreeableness (α ≥ 0.79), openness (α ≥ 0.75), conscientiousness (α ≥ 0.78) and neuroticism (α ≥ 88).

Likewise, personal trust is related to radical right support (Berning & Ziller, Reference Berning and Ziller2017; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2009) but could potentially also explain why people become nostalgic. I use one item asking, ‘Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can't be too careful in dealing with people? Please indicate a score of 0 to 10.’ (0 [You can't be too careful] – 10 [Most people can be trusted]). Like personality, personal trust was measured four times.

Results

Descriptive analyses

About 61 per cent of all respondents reported to experience nostalgia at least once or twice a month. Approximately 33 per cent stated to be nostalgic at least once a week. Men reported less personal but not group‐based nostalgia than women (p < 0.001, |d| = 0.12). They were also somewhat more likely to vote for the PVV, like the party and its head Geert Wilders and endorse economic and cultural conservatism (all ps < 0.001, |ds| > 0.08). Employed or self‐employed participants were less likely to report group‐based but not personal nostalgia than unemployed participants (including students, homemakers, retired participants, p < 0.001, |d| = 0.19). They were also somewhat more likely to vote for the radical right, like the PVV and Wilders, and to be more economically but less culturally conservative (all ps < 0.05, |ds| > 0.03). Participants of Dutch origin reported less group‐based and personal nostalgic than participants of other origins (both ps < 0.001, |ds| > 0.16). However, they were more likely to vote for the radical right, like the PVV and Wilders, and to be more culturally but not economically conservative (all ps < 0.05, |ds| > 0.06).

While more educated and wealthier people were less likely to report nostalgic experiences, group‐based nostalgia increased with age. The place of residence was unrelated to nostalgia. Group‐based and personal nostalgia were highly correlated (Supporting Information S2.2). There was little variation in either nostalgia type over time, and the variation was larger between individuals than within individuals (see Supporting Information S3.1.‐3.2.)

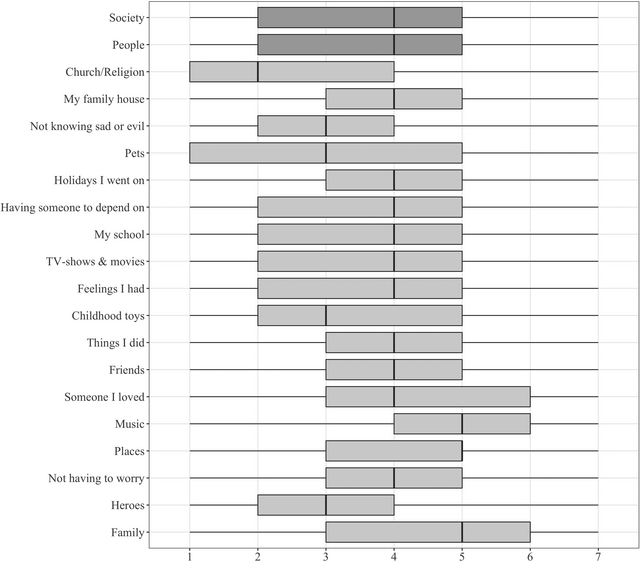

As shown in Figure 2, people were primarily nostalgic for music, family, places they have been to, things they did or people they loved. Nostalgia for church or religion was less common. People were approximately equally nostalgic for how society was and how people were. All nostalgia forms were highly related. The frequency of nostalgic experiences was most strongly related to feelings one had, things one did and places (Supporting Information S3.3.). Two‐sample t‐tests indicated that PVV voters experienced more group‐based (p < 0.001, d = 0.28) and somewhat more personal nostalgia (p = 0.03, d = 0.13) than voters of other parties.

Figure 2. Contents of nostalgia.

Note: Intensity of group‐based (dark‐grey) and personal (light‐grey) nostalgia. Feeling nostalgic about 1 (Not at all) – 7 (Very). Vertical lines show the median, dots the mean, boxes the interquartile range (IQR) and whiskers min and max values, respectively.

Both nostalgia types were positively associated with all outcome measures but economic conservatism (Supporting Information S3.4). Group‐based nostalgia was associated with lower government and personal satisfaction, personal nostalgia only with the latter. The two nostalgia forms were also positively correlated with national identity, agreeableness, conscientiousness and neuroticism but negatively with personal trust. Government and personal satisfaction were associated with weaker radical right support and less cultural conservatism but more economically conservative attitudes. The outcome measures were positively related.

Hypotheses tests

Given that most variation in nostalgia occurred between rather than within individuals, I cannot exploit any temporal variation in the panel. Therefore, I model between‐subject differences using time‐fixed effects panel models and robust standard errors clustered at the individual level. These models provide limited causal interpretations compared to individual‐fixed effects because they do not account for differences between individuals (except for differences accounted for by the model's control variables). However, time‐fixed panel models still provide better evidence than cross‐sectional designs since they rely on more observations per case and account for time‐specific effects. Together with time‐invariant (i.e., demographic) and time‐variant (i.e., national identity, personality, personal trust) control variables, these models reduce the risk of omitted variable bias and thus facilitate causal conclusions, even if not as firmly as in any experiments (e.g., Van Prooijen et al., Reference Van Prooijen, Rosema, Chemke‐Dreyfus, Trikaliti and Hormigo2022).

In five models, I regress the outcome measures on nostalgia: I estimate the direct effects of group‐based nostalgia (Model 1), personal nostalgia (Model 2) and their combination (Model 3). I then estimate one model controlling for demographics and national identity (Model 4). I report an additional model controlling for demographic background, personality and personal trust (Model 5) in Supporting Information 4Footnote 5. I test the binary outcome ‘radical right vote’ as a logistic model and all other models as continuous regressions. I normalize all continuous predictors to facilitate comparability between them.

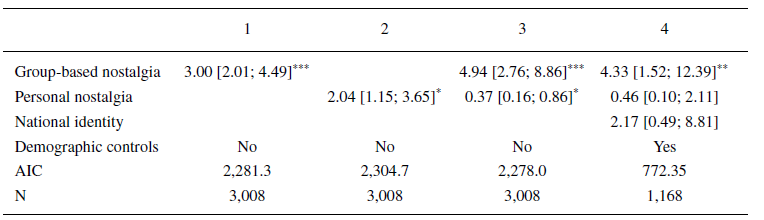

First, the hypothesis that group‐based nostalgia is associated with a higher propensity to vote for the radical right PVV (Hypothesis 1) is supported (Table 1a). While accounting for the control variables, moving from minimum to maximum group‐based nostalgia is associated with an increase in the odds of voting for the PVV by 4.33 or 5.50 (see Supporting Information S4.1. for tables including all control variables). Substantially, and all else equal, an increase in group‐based nostalgia from the first to the third quantile is associated with an increased probability of voting for the PVV of about 9.5 per cent. While the relationship between personal nostalgia and the outcome is negative when controlling for group‐based nostalgia and personality, this association is insignificant when accounting for national identity.

Table 1a. Radical right vote propensity (Hypothesis 1)

Note: Time‐fixed effect panel models with robust standard errors. Continuous predictors normalized.

*p < 0.05;

**< 0.01;

***< 0.001.

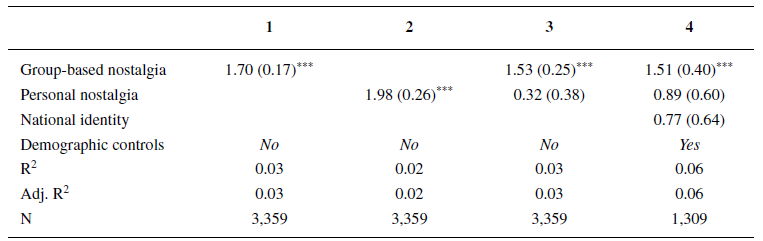

Second, the hypothesis that group‐based nostalgia is associated with more liking of the radical right (Hypothesis 2) is also supported (Table 1b). The size of this association is modest, such that moving from minimum to maximum group‐based nostalgia is, ceteris paribus, associated with about 1.5 points more sympathy on a 0−10 scale. Again, the results remain robust when controlling for demographic background, national identity and personality and personal trust (see Supplements S4.2.1.‐3. and S4.4. for details). The effect of personal nostalgia is insignificant when accounting for group‐based nostalgia but positive when adding personality controls. The results do not substantially differ when disaggregating PVV and Wilders liking.

Table 1b. Radical right liking (PVV and Geert Wilders) (Hypothesis 2)

Note: Time‐fixed effect panel models with robust standard errors. Continuous predictors normalized.

*p < 0.05;

**< 0.01;

***< 0.001.

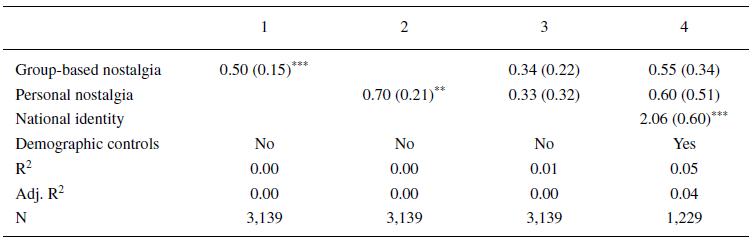

Third, the hypothesis that group‐based nostalgia is associated with more conservative attitudes (Hypothesis 3) remains unsupported (Table 1c). Group‐based nostalgia does not relate to conservative attitudes when accounting for demographic background and other controls. When differentiating economic and cultural conservatism (see Supporting Information S4.3.1.‐3. and S4.5. for details), group‐based nostalgia is associated with more culturally but not economically conservative attitudes. Instead, personal nostalgia is again inconsistently associated with the outcomes, such that it tends to relate positively to general and economic conservatism when controlling for personality but not when accounting for national identity.

Table 1c. Conservatism (Hypothesis 3)

Note: Time‐fixed effect panel models with robust standard errors. Continuous predictors normalized.

* p < 0.05;

**< 0.01;

***< 0.001.

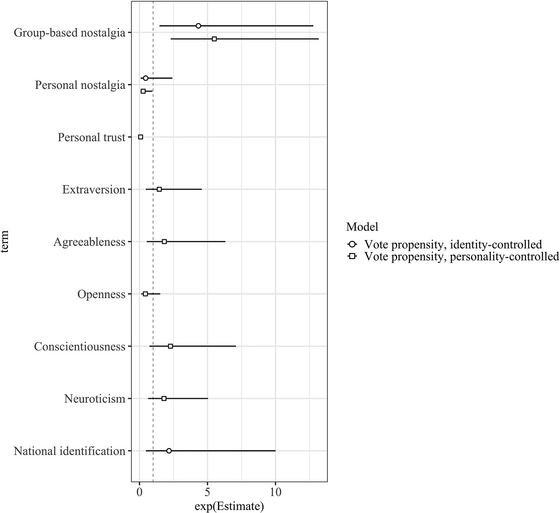

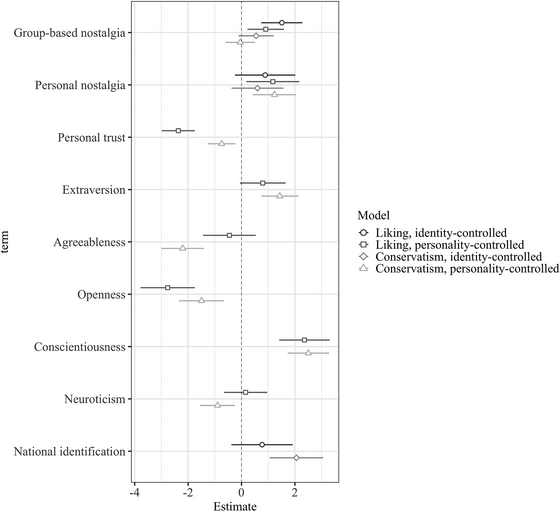

As summarized in Figures 3a and b, group‐based nostalgia is consistently associated with a higher vote propensity and sympathy for the radical right. While it is not significantly associated with more conservative attitudes in general, it is linked to a stronger endorsement of cultural conservatism. Regarding personal nostalgia, where I had not raised any hypotheses, its relationship with radical right support is inconsistent. It tends to be associated with more support for this orientation until group‐based nostalgia or relevant covariates are accounted for.

Figure 3a Results for radical right vote propensity.

Note: Odds with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3b Results for radical right liking and conservatism.

Note: Regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals.

Exploratory analysis 1: Supplementary analyses

I conduct two sets of supplementary analyses. First, I estimate reverse causality by regressing group‐based and personal nostalgia on the propensity to vote for the radical right, respectively (Supporting Information S5). Radical right voting is associated with higher magnitudes of group‐based but not personal nostalgia. While this finding speaks to the relevance of radical right rhetoric shaping people's experiences (e.g., Elgenius & Rydgren, Reference Elgenius and Rydgren2022; Mols & Jetten, Reference Mols and Jetten2020), it also shows that the above‐presented coefficients need to be interpreted cautiously. Group‐based nostalgia is associated with radical right voting intentions, sympathy for the party and its leader and more culturally conservative attitudes when accounting for temporal shocks and a series of background variables. Nevertheless, this relationship is reciprocal, and true causal effects can only be established through experimental manipulations of nostalgia (e.g., Van Prooijen et al., Reference Van Prooijen, Rosema, Chemke‐Dreyfus, Trikaliti and Hormigo2022).

Second, I evaluate whether group‐based nostalgia is associated with support for other parties (Supporting Information S6). I group the parties following Jolly and colleagues (Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022) and regress vote propensity for each party family on nostalgia with the exact model specifications as in Models 4 and 5. Group‐based nostalgia is only significantly associated with liberal voting intentions. The odds of voting for a liberal party decrease with stronger group‐based nostalgia but increase with personal nostalgia.

Exploratory analysis 2: Testing relative deprivation as a mechanism

To recall, I posit that nostalgia is associated with radical right support because thinking about the past would make people implicitly compare the past and the present, which creates temporal relative deprivation. Importantly, I argue that this mechanism only works on the sociotropic level (Abdallah, Reference Abdallah2022; Solodoch, Reference Solodoch2021), such that societal developments make group‐based nostalgic individuals experience group‐based relative deprivation. In contrast, personal nostalgia does not evoke personal relative deprivation. While the preregistered analyses show that group‐based nostalgia is more consistently related to radical right support than personal nostalgia, I did not, as yet, test the relative deprivation argument.

Thus, I conduct an exploratory mediation analysis and examine the relationship between nostalgia and radical right voting intentions when mediated through group‐based and personal relative deprivation. I operationalize group‐based relative deprivation with government satisfaction and personal relative deprivation with personal satisfaction. Using the R‐package lavaan (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012), I model the relationships of both nostalgia types with radical right voting through government and personal satisfaction (bootstrapping 5,000 samples). Given the binary outcome, I use a diagonally weighted least square (DWLS) estimator with robust standard errors. All models account for time effects and include all control variables as above.

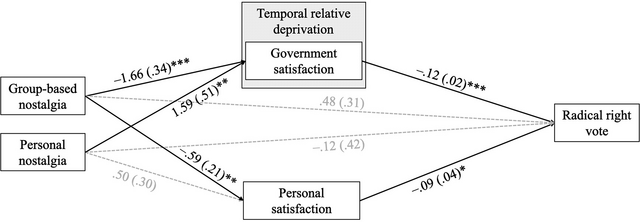

As expected under exploratory hypothesis 1, temporal group‐based relative deprivation does (partially) mediate the relationship between group‐based nostalgia and radical right voting: The more people long for society's past, the less satisfied they are with the government. In turn, less government satisfaction is associated with a higher likelihood of voting for the radical right (see Supporting Information S7 for coefficients and fits statistics). Figure 4 illustrates this mechanism when controlling for national identity. It also shows that personal satisfaction unexpectedly mediates this relationship, too, such that group‐based nostalgic individuals tend to be less personally satisfied, which is related to higher radical right vote propensities. However, Supporting Information S7 shows that only the mediation through government satisfaction is robust when controlling for personality characteristics and personal trust.

Figure 4. Mediation results (controlling for national identity).

Note: Dashed, grey lines represent insignificant relationships.

Moreover, personal nostalgia is not associated with lower personal satisfaction, which suggests that thinking about the personal past does not evoke personal relative deprivationFootnote 6.

Unexpectedly, however, personal nostalgia is related to radical right voting through government satisfaction, such that people tend to be more satisfied with the government when longing for their personal past. Together, these results suggest that thinking about the societal past is associated with temporal group‐based relative deprivation, which, in turn, is related to radical right support.

Discussion and conclusion

Why is nostalgia, and particularly its group‐based contents, associated with radical right support? Arguably, preferences for a more ethnically homogenous past will explain parts of it, such that people support exclusionary parties if they feel that societies have diversified too much (e.g., Elgenius & Rydgren, Reference Elgenius and Rydgren2022; Smeekes et al., Reference Smeekes, Wildschut and Sedikides2021). But, as shown in previous research (Hepper et al., Reference Hepper, Wildschut, Sedikides, Ritchie, Yung, Hansen and Zhou2014; Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Sedikides, Arndt and Routledge2006), nostalgia is a widely and frequently experienced emotion, and the present paper confirmed that its experience is not limited to radical right voters. Hence, I tested an underlying mechanism that could explain why nostalgia, particularly its group‐based contents, would relate to radical right support.

Applying relative deprivation reasoning (Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Christ, Wagner, Meertens, Van Dick and Zick2008; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Pettigrew, Pippin and Bialosiewicz2011), I argued that nostalgia evokes implicit comparisons of past and present, based on which people would subjectively conclude that the societal past was better than the present. This temporal group‐based relative deprivation would then be associated with attempts to improve conditions through radical right voting. Given that personal nostalgia helps individuals find meaning in the present (Routledge et al., Reference Routledge, Arndt, Wildschut, Sedikides, Hart, Juhl, Vingerhoets and Schlotz2011; Sedikides & Wildschut, Reference Sedikides and Wildschut2017), I posited that personal nostalgia would not evoke an equivalent form of personal relative deprivation. Thus, I argued that radical right support is more related to sociotropic rather than egotropic motivations (Abdallah, Reference Abdallah2022; Solodoch, Reference Solodoch2021).

Preregistered analyses of representative panel data from the Netherlands showed that nostalgia was a prevalent emotion. It also supported the claim that primarily group‐based nostalgia was associated with radical right support. Interestingly, the results were consistent for voting intentions and radical right sympathy, but nostalgia's relationships with conservatism were less clear‐cut. While the null results for the relationship with general left‐right placement indicate that this measure was too broad to be meaningful, the null results for economic conservatism are in line with prior literature arguing that the radical right is not necessarily economically conservative (e.g., De Lange, Reference De Lange and Mudde2016; Zaslove, Reference Zaslove2009). In contrast, the positive relationship with cultural conservatism suggests that parts of nostalgia's role are explained by a longing for a more ethnically homogenous past (Filsinger et al., Reference Filsinger, Wamsler, Erhardt and Freitag2020; Smeekes et al., Reference Smeekes, Wildschut and Sedikides2021).

In subsequent exploratory mediation analyses, I found support for the argument that one of the reasons why nostalgia motivates radical right voting could indeed be temporal relative deprivation. People who thought about the way society was and how people were, tended to be less satisfied with the government, which was related to radical right voting intentions. Unexpectedly, group‐based nostalgia also tended to be associated with personal dissatisfaction, which was related to vote choice. Personal nostalgia, instead, did not seem to evoke such temporal relative deprivation experiences. People who experienced personal nostalgia tended to be more satisfied with the government. This suggests that thinking about the past has different functions depending on what people long for. I will discuss this next.

Group‐based and personal nostalgia as two forms of coping

The present results suggest that nostalgia's relationship with the radical right is more intricate than suggested in some prior research (e.g., De Vries & Hoffmann, Reference De Vries and Hoffmann2018). Many people across the world regularly experience nostalgia (Hepper et al., Reference Hepper, Wildschut, Sedikides, Ritchie, Yung, Hansen and Zhou2014; Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Sedikides, Arndt and Routledge2006) and even if the realization that the desired time is bygone may hurt, the overall effects of its experience are positive (see Sedikides et al., Reference Sedikides, Wildschut, Stephan, Forgas and Baumeister2018, for a review). A gross depiction of so‐called left behind voters stuck in some idealized past (e.g., Jennings & Stoker, Reference Jennings and Stoker2016) does thus seem inappropriate.

Differentiating single contents of nostalgia and theorizing what they evoke among individuals seems more fruitful. Certainly, the diversification of Western democracies may explain some people's longing for a more ethnically homogenous group‐based past (e.g., Lubbers & Smeekes, Reference Lubbers and Smeekes2022; Smeekes et al., Reference Smeekes, Wildschut and Sedikides2021). But group‐based nostalgia is not limited to that. Previous research suggests that group‐based nostalgia captures contents as broad as political systems (Ekman & Linde, Reference Ekman and Linde2005), grandiosity (Marchlewska et al., Reference Marchlewska, Cichocka, Panayiotou, Castellanos and Batayneh2018), traditions and community (Jobson & Wickham‐Jones, Reference Jobson and Wickham‐Jones2010) and the longing for ‘coming home’ (Robertson, Reference Robertson1988). Hence, different contents of group‐based nostalgia relate to different political orientations (Stefaniak et al., Reference Stefaniak, Wohl, Sedikides, Smeekes and Wildschut2021).

While the specific contents of personal and group‐based nostalgia surely matter, I devoted this paper to understanding why these two overarching forms have different relationships with the radical right. The result that only thinking about group‐based history is associated with dissatisfaction and, in turn, radical right voting intentions, suggests that personal and group‐based nostalgia can be understood as different kinds of coping with a challenging present.

On the one hand, the temporal comparison following group‐based nostalgia results in negative evaluations of the sociotropic present, which motivates political action to attenuate this dissatisfaction. Group identities get reinforced and become exclusionary towards outgroups (Smeekes, Reference Smeekes2015). On the other hand, temporal comparisons following personal nostalgia do not create dissatisfaction with one's personal present and thus do not motivate political action. But more than that, the fact that personal nostalgia was positively associated with government satisfaction and support for liberal parties (including the governing VVD during the study period, see Supporting Information S6) suggests that personal nostalgia helps to appreciate the present. Even if current challenges may spark people's longing for their personal past, reflecting on these times provides strength and meaning for the present (Boym, Reference Boym2001; Routledge et al., Reference Routledge, Arndt, Wildschut, Sedikides, Hart, Juhl, Vingerhoets and Schlotz2011; Sedikides & Wildschut, Reference Sedikides and Wildschut2017).

Connecting these strategies to sociotropic versus egotropic political motivations (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Kinder & Kiewiet, Reference Kinder and Kiewiet1981), I suggest understanding nostalgia in relation to the radical right as a primarily sociotropic motivation. Personal memories seem secondary, given that they do not come with equivalent feelings of deprivation on a personal level.

Strengths, limitations and future research

Besides the theoretical effort to propound an argument for why nostalgia, specifically its group‐based contents, relate to radical right voting, this paper used large‐scale, representative and detailed panel data to illustrate the argument. By mapping the prevalence and variety of nostalgic experiences and testing their differential relationships with radical right support, I hope to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of this emotion in political science research. As with other emotions (e.g., Chudy et al., Reference Chudy, Piston and Shipper2019), being nostalgic is not exclusively good or bad. Its consequences depend on what its experience elicits.

As for the limitations, the most significant caveat is that panel data remains subject to other omitted variables, especially as the little within‐individual variance prevented accounting for individual‐fixed effects. Although the representative data reduced selection effects and its panel design accounted for time effects, the presented analyses do not allow for causal interpretations as in experimental designs (e.g., Van Prooijen et al., Reference Van Prooijen, Rosema, Chemke‐Dreyfus, Trikaliti and Hormigo2022). Besides omitted variable bias, such designs matter because radical right politicians drive emotions with their rhetoric (e.g., Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Rooduijn and Bakker2022; Widmann, Reference Widmann2021). Externally valid, natural experiments seem particularly promising for understanding causality better.

The results indicate several pathways for future research. First, studies could examine the generalizability of the findings presented here. While this paper used detailed data, it was limited to one country and a few years from a likely case. It is thus worthwhile to examine if these results travel to other countries and political systems (such as Eastern European countries with a communist past, see Ekman & Linde, Reference Ekman and Linde2005), especially as different countries differ in their conceptualization of nationhood and history of ethnic heterogeneity (e.g., Brubaker, Reference Brubaker1992). Related to the diversity of group‐based nostalgia discussed above, what people think of when longing for the group‐based past depends on a country's history. Hence, group‐based nostalgia's relationships with various political orientations may differ across countries, which promises fruitful exploring.

Second, the temporal relative deprivation argument could be pursued further. While I found that sociotropic motivations following group‐based nostalgia were more politically relevant than egotropic ones, the differentiation of group‐based vs. personal paths of nostalgia and relative deprivation was not as clear‐cut as I theorized. Future research on emotions in politics, relative deprivation and their combination could clarify where the personal and the group‐based paths are distinct or intersect.

Third, future studies should investigate the role of personal nostalgia. The inconsistent results for personal nostalgia suggest that it may not be as relevant for radical right support as group‐based nostalgia. However, if radical right support politically expresses feelings of uncertainty or pessimism about the present (cf. Steenvoorden & Harteveld, Reference Steenvoorden and Harteveld2018), personal nostalgia's capacity to help individuals find meaning in a distressing present (Routledge et al., Reference Routledge, Arndt, Wildschut, Sedikides, Hart, Juhl, Vingerhoets and Schlotz2011; Sedikides & Wildschut, Reference Sedikides and Wildschut2017) could be an alternative route to cope with dissatisfaction. Individuals can easily evoke personal nostalgia themselves (e.g., Wildschut et al., Reference Wildschut, Sedikides, Arndt and Routledge2006). This suggests that it could serve as a simple and reliable tool to bear with distressing contexts like climate change, uncertain job markets or wars without raising support for parties that are defined as authoritarian, populist and nativist.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: