Trust was central to the origins of the French Revolution, and remained central to its course and outcomes. This may seem like a paradoxical claim, when the one thing everyone knows about the Revolution is that it was a slide into increasingly paranoid and fatal suspicion. But as Anne Simonin has recently highlighted, even during its most fatal months ‘trust between governors and governed’ was ‘a fundamental political question’ and a significant component of the mental and emotional landscape of the nation.Footnote 1 This was also emphatically true during the years preceding this violent upheaval. When France’s finance minister Charles-Alexandre de Calonne opened the so-called ‘Pre-revolution’ in February 1787, with a doomed attempt to have a hand-picked Assembly of Notables endorse his plans for fiscal reform, almost his first words to the gathering were a summons to have ‘the most just confiance’ – trust – in the intentions of the king.Footnote 2 As he developed his reflections, Calonne noted how, when he came to office in 1783, ‘all the funds were empty, all the public stocks falling, all circulation interrupted; alarm was general, and trust destroyed’. Only through his own immediate efforts had ‘such a trust’ been restored that crisis was averted, and only his continuing efforts ‘to bring back a trust gone astray’ had now opened the way to real, lasting reform.Footnote 3 These claims proved fatally hubristic, and his failure to recuperate trust in practice would see Calonne ejected from office only months later, and the start of a rapid spiral towards state bankruptcy that left the convocation of an Estates-General – an elected national assembly unseen for 175 years – as the only route out of collapse.Footnote 4

The French were summoned to elect deputies for the Estates with a frequently cited royal assurance that the desires of even ‘the most remote dwelling-places’ would reach the king.Footnote 5 A more explicit language of trust was also present when the crown circularized its provincial governors with instructions to initiate the electoral process. It was ‘by a mutual trust and by a reciprocal love between the sovereign and his subjects’ that ‘an effective remedy for the ills of the State’ would emerge from the gathering. Thus those chosen to attend should be ‘all personages worthy of this great mark of trust, by their integrity and by the good spirit that animates them’.Footnote 6 This article will discuss how the thousands of individuals who answered this call in local assemblies in March and April 1789 themselves used the language of trust both positively and negatively as part of a kaleidoscopic episode of political self-expression. This showed that they were not naively trustful subjects, but were assuming potent political agency, to critique what had gone before, and to demand change in ways that affirmed their collective local identities and national political citizenship. They thus sent their deputies to Versailles with a complex freight of expectations, blending the trusting and the mistrustful, indicating why it would prove so difficult to provide France with orderly, top-down constitutional reform.

I

Within Anglophone social science, ‘trust’ has a family of definitions. In a collection of essays on the question Whom can we trust?, the first chapter defines it as ‘an expectation of beneficent reciprocity from others in uncertain or risky situations’, while the second opts for ‘a belief that the other person will take an action in one’s own interest, perhaps in response to a trusting action’.Footnote 7 Such definitions are usually held to relate to social conditions that are, in creating a need to risk trusting strangers, specifically modern.Footnote 8 However, Charles Tilly noted in 2004 that it was impossible in practice to define radically different eras of trust in European or global history, while offering his own pithy definition: ‘Trust consists of placing valued outcomes at risk to others’ malfeasance’, and a trust relationship is one where ‘people regularly take such risks’.Footnote 9

Recent historiography has shown that the practical consideration of trust and risk was at the heart of social and political life in pre-revolutionary France. Elise Dermineur demonstrates that villagers and townsfolk were embedded in networks of financial credit that drew on practices of interpersonal evaluation. As she concludes, ‘Contrary to one entrenched view, trust is not a modern concept’.Footnote 10 Clare Haru Crowston’s discussion of crédit and its permeation of social, political, and economic relations in the revolutionary era reinforces this.Footnote 11 Crowston highlights the doubled meaning of the term: the ‘personal/subjective’ evaluation of individual reputation, merit, and esteem – of trustworthiness, in essence – and the ‘material’ assessment of financial resources and potential power that built on and paralleled it. She shows that ‘revolutionary politics clearly wedded moral values and material interests’, using crédit in both senses.Footnote 12 This was demonstrated on 17 June 1789, when the ‘National Assembly’ that had just adopted that name separated itself from the perceived general malfeasance of royal government by guaranteeing the entirety of the kingdom’s debts, on the basis of nothing except the political will to do so.Footnote 13

Future events would demonstrate the insurmountable complexity that followed from such a decisive act.Footnote 14 Looking back to the origins of the Assembly, in the cahiers de doléances, ‘registers of grievances’, drawn up by localities as part of the time-honoured procedure of Estates-General convocation, allow us to discern the complexity of sentiment and expectations of trust weighing upon these events from their outset. The cahiers are a remarkable corpus of political expression, and have their own classic historiography. Reference to Alexis de Tocqueville’s self-reported ‘terror’ half a century later, at discovering the universal ‘simultaneous and systematic repeal’ of all France’s laws and customs demanded by the texts, is obligatory.Footnote 15 The 1998 work of Gilbert Shapiro and John Markoff remains unmatched for detailed examination of the cahiers, their research team having encoded thousands of distinct ‘revolutionary demands’. Due to the level of abstraction required by such volumes of data, that work focuses exclusively on the subjects of grievances, rather than the form of their expression.Footnote 16 Attention to such forms, given the vast volume in which the cahiers of thousands of village communities survive in the archive, has often taken a celebratory route, offering textual selections as evidence of proto-democratic sensibilities whose meaning is largely taken for granted.Footnote 17 As Pierre-Yves Beaurepaire has noted, small sample-sizes and ‘ideological postures’ continue to render many analyses of questionable overall value.Footnote 18 Recent efforts to digitise the corpus of the nineteenth-century Archives parlementaires, including many of the texts of the cahiers carried to Versailles by the elected deputies of the Estates-General, offer the possibility of wider ranging semantic analysis.Footnote 19

One preliminary observation from the corpus of pre-revolutionary texts also included in the Archives parlementaires is how far the ideology of absolutist paternalism continued to take an emotional, trusting, childlike attitude for granted as the natural relationship of subject to monarch, and as the proper motivation for dutiful obedience and active collaboration.Footnote 20 In Calonne’s words, cited above, personal, emotional trust, public trust, and what we might now call investor confidence were bundled together as key motivating forces and essential components of both crisis and recovery.Footnote 21 For Calonne, the outcome of his appeal was disaster, as the Notables blamed him for the situation he claimed to be addressing, propelling his ejection from office in early April 1787. The replacement Brienne ministry made its own increasingly hollow efforts to promote the language of compulsory trust, telling the Notables on the eve of their dissolution that ‘you have prepared and facilitated the most desirable revolution, with no other authority than that of trust, which is the first of all the powers [puissances], in the government of States’.Footnote 22 Brienne also warned that assemblies which ‘owed their existence’ to royal trust ‘will sufficiently feel the price of that not to expose themselves to losing it in abusing his trust’.Footnote 23

A few months later, the language of trust became overtly minatory. On 6 August 1787, in the face of elite resistance, the personal presence of the king at a lit de justice had to be used to register new measures in the Parlement of Paris. Such measures were declared essential ‘to fortify public trust’, and moreover, ‘the nation owes too much trust and respect to its king, to be able to doubt’ the value of reforms. ‘Public mistrust [méfiance] would be at this moment the most dangerous obstacle one could oppose to the general good with which the Government is concerned.’Footnote 24 More than a year of turmoil followed, including the short-lived abolition of the deeply distrustful, and actively resistant, Parlements in May 1788, and a brush with state bankruptcy at the end of that summer that forced the final concession that an Estates-General was the only way to legitimize further reform.Footnote 25

II

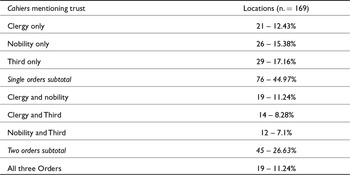

Like everything else about old-regime France, the process of convoking the Estates-General was complex and, to the modern eye, somewhat obscure.Footnote 26 A nested structure of royal judicial boundaries (bailliages or sénéchaussées in different regions) and allowance for population was used to assign varying numbers of ‘deputations’ of one cleric, one noble, and two others to electoral districts.Footnote 27 Representatives meeting in each location produced separate cahiers for each of those three Estates, or Orders, as they were interchangeably known, along with a handful of jointly-produced texts, markers of advanced patriotic unity.Footnote 28 The Archives parlementaires contain the records of some 169 of these locations in metropolitan France. Not all the documents subsequently identified by historians are included in this corpus, but it covers the vast majority of locations for which such documents can be found.Footnote 29 Of those 169 bailliages and sénéchaussées, some 140, or 82.8%, referenced confiance in at least one of their surviving cahiers (see Table 1).

Table 1. Numbers and percentages of bailliage/sénéchaussée assemblies mentioning confiance, breakdown by Order.

As they were summoned into being on the explicitly-stated ground of official trust, we might expect trust to appear in formulaic fashion in the cahiers themselves. Yet it does not. Usage skewed clearly towards the likelihood that only one Order in any particular location would mention trust. This suggests that it was the choice of particular gatherings, and their drafting authors, rather than any kind of imposed model or pattern.Footnote 30 The total number of individual Orders’ cahiers that mention trust is 223, or 42% of some 531 extant individual cahiers – 165 First-Estate (73 documents mentioning trust, 44.2%), 165 Second-Estate (76, 46.1%), and 201 Third-Estate (74, 36.8%).Footnote 31 Particular references to trust were widely distributed through the texts in question. On average, each cahier that mentioned it did so more than once (148 mentions across 73 clergy texts, 139 across 76 noble ones, and 178 across 74 Third-Estate documents), but the distribution covers a large number of single mentions, through to a handful of documents that used confiance more than a dozen times.

The cahiers themselves are rarely less than several thousand words, and often much longer, addressing dozens of individual issues, and in some cases offering entire treatises on public administration. Their use of confiance can be mapped across five dimensions, as follows:Footnote 32

• Location: texts tend to have distinct sections, with opening remarks including expressions of loyalty and gratitude; overviews of the state of the nation; elaborated grievances and recommendations; specific instructions to the chosen deputies (what to insist on, what to be flexible about, how to honour their constituents’ wishes, etc.); and other, usually process-based, commentary.

• Actor: the person or group observed to be trusting (or distrusting); divided into: the drafters of the text itself; the king; the administration; the nation; the specific Order; and other groups.

• Target: who is trusted (or not): the king himself; current finance-minister Jacques Necker (widely understood as the architect of change); government and administration more generally; the chosen deputies and the Estates-General itself; the wider nation or public; the specific Order; the reform process more widely; and occasional reflexive reference to trust in the text’s authors.

• Substance: what is the essence of the trust expressed: is it fundamentally interpersonal, either a one-way sentiment towards a person or group, or a sense of mutual trust between groups; or is it more abstract: trust in ongoing reform processes, or conversely trust in existing structures; or trust in the eventual outcomes of the Estates-General?

• Orientation: how is trust itself being experienced: as a clearly positive attribute; as something lacking or to be restored; as actively threatened by events or attitudes; or as potentially endangered; and, finally, as a simple adjective (particularly in regard to fears about the censorship of letters, regarded as being matters de confiance)?

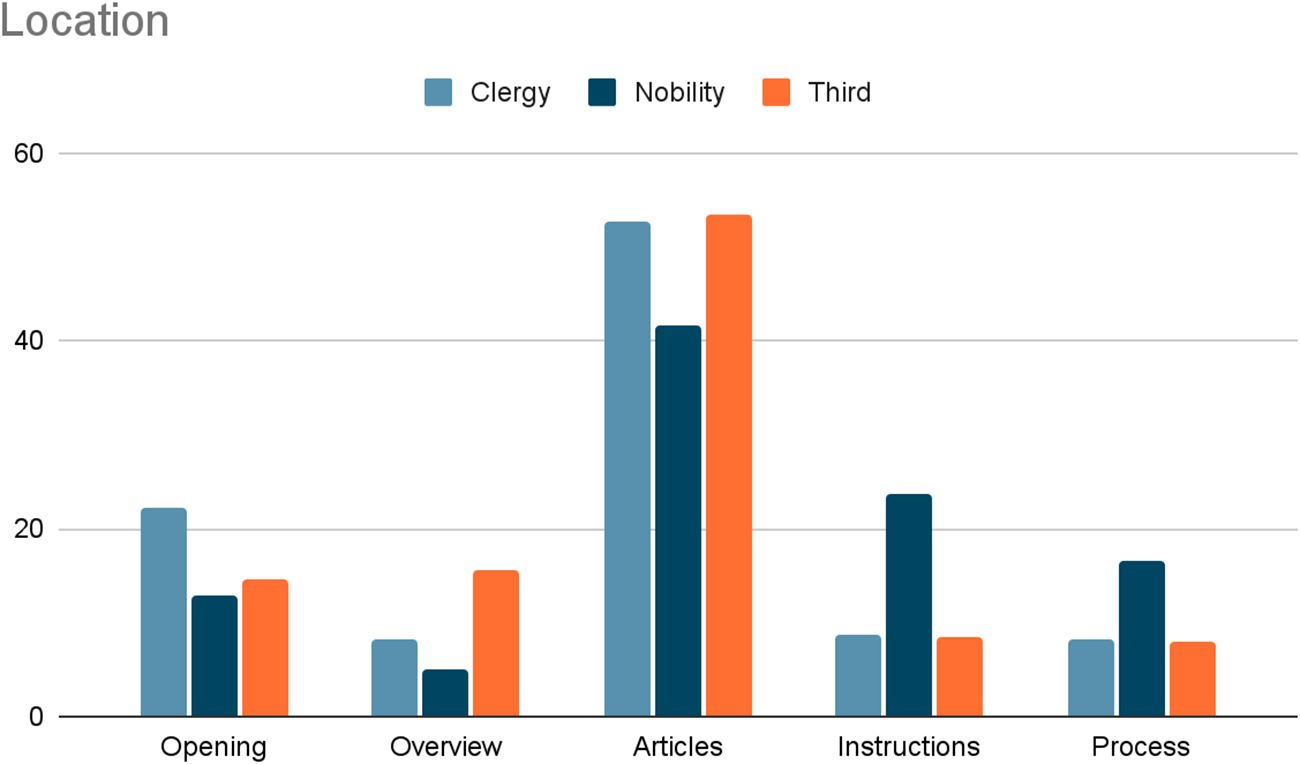

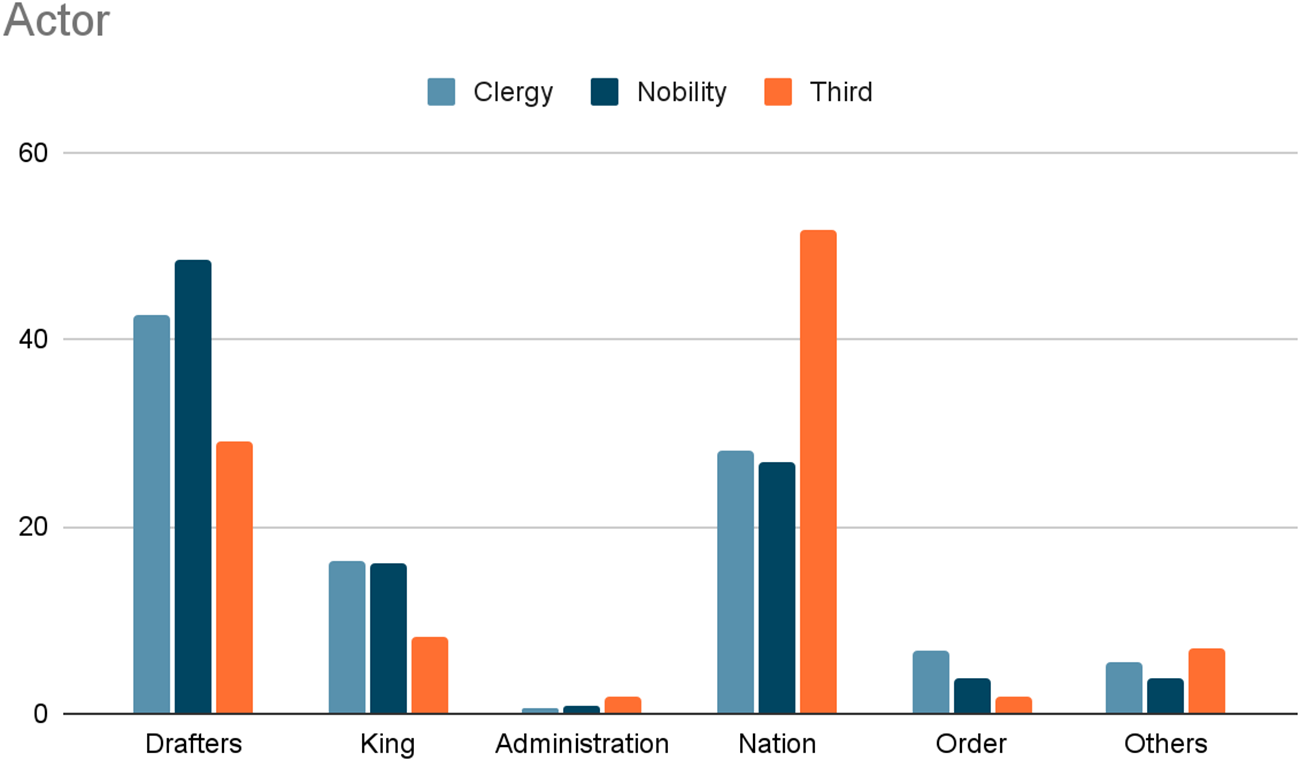

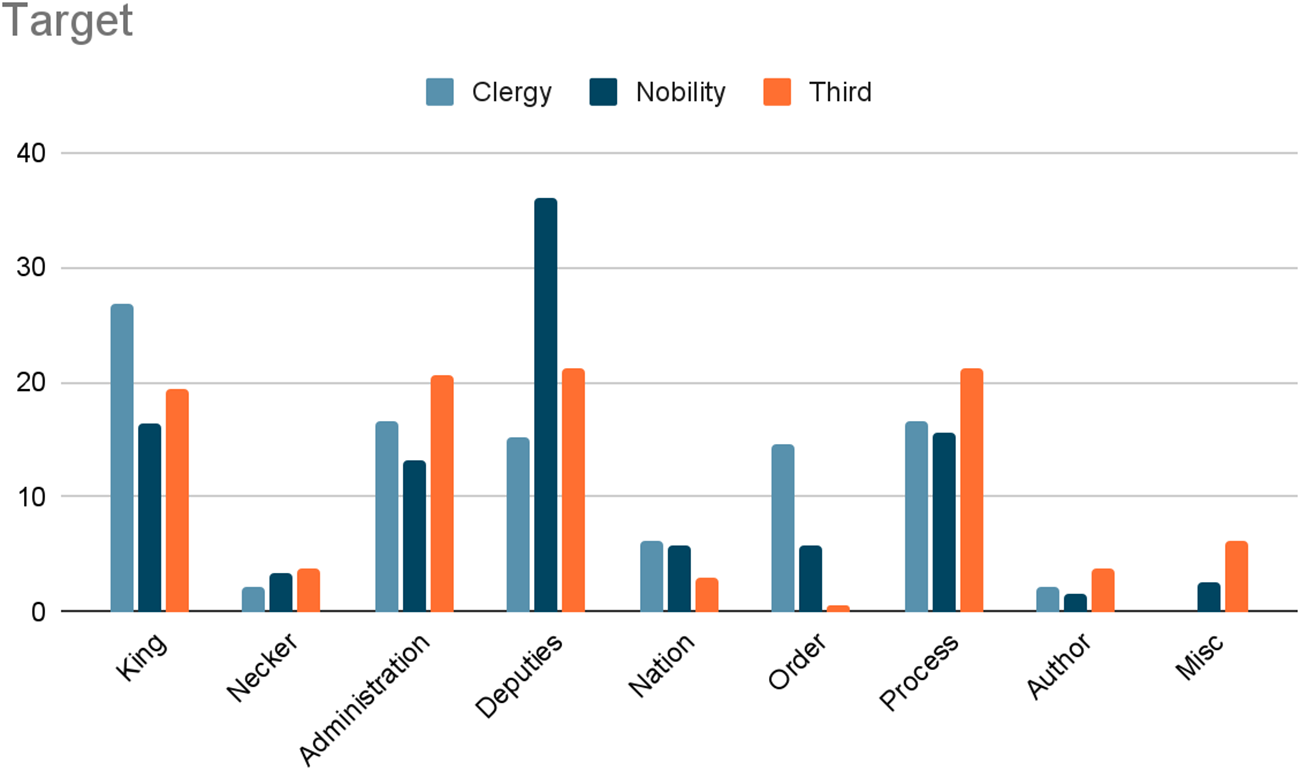

The following charts offer an initial comparison of the distribution of these characteristics within the cahiers of the three Orders, normalized by percentage of the overall number of occurrences for each Order.Footnote 33

For all three Orders, Figure 1 shows that reference to confiance is not confined to rhetorical gestures in prefatory remarks, but is substantially concentrated in the bulk of the documents devoted to grievances and proposed changes: almost half of all uses connect the issue of trust to a specific situation in need of remedy. Also noteworthy is the nobility’s relatively clear preference for using a language of trust when detailing the expected conduct of their representatives, and the nature of the drafting process itself, invoking it as a significant element in the political relationships these actions embodied.

Figure 1. Location of confiance mentions within the structure of cahiers texts.

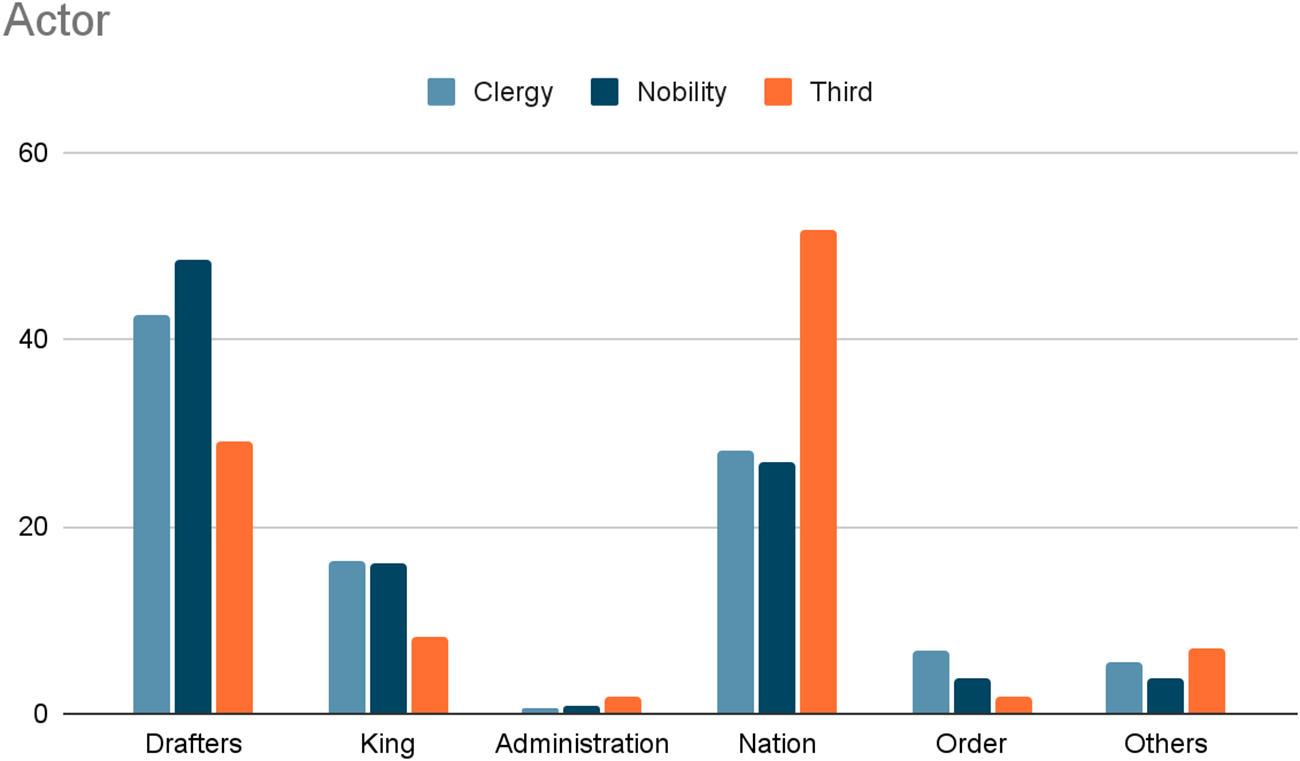

In considering ‘who trusts’ (Figure 2), the dominant balance between the drafters identifying themselves, as an embodied assembly, as the actor, and identifying the people or nation as a much larger collective, stands out – strikingly, across all three Orders, although with the balance tilted differently for the Third. Trusting is something that drafters frequently express as an active, personal engagement, while also feeling confident in identifying it as a quality of the whole body politic. Invocations of the king as a trusting actor, coming a distant third to these, are almost always in terms of gratitude and respect, while the occasional mention of other governmental figures is largely negative.

Figure 2. Identity of the trusting actor within cahiers texts.

Examining who or what is trusted (Figure 3) demonstrates the breadth of the concept. The king garners positive attention from all three Orders, but a very substantial majority of cahiers do not choose to explicitly express trust in him – it was evidently not a ceremonious expectation (or one they were willing to fulfil). He is outscored for both the Nobility and Third by trust in their own elected deputies – although, as we shall see later, the latter, especially from the nobility, are sometimes admonitory in tone – and challenged for second place by trust in those undertaking the reform process more broadly. Only the clergy were significantly likely to invoke trust in themselves as a nationwide collective Order, and it is notable that the general nation, frequently depicted as trusting, is only rarely described as trusted. The relatively frequent mention of administrative personnel in general is linked to a more evaluative tone as to whether they merit trust, or if trust in them has been misplaced.

Figure 3. Identity of the target of trust in cahiers texts.

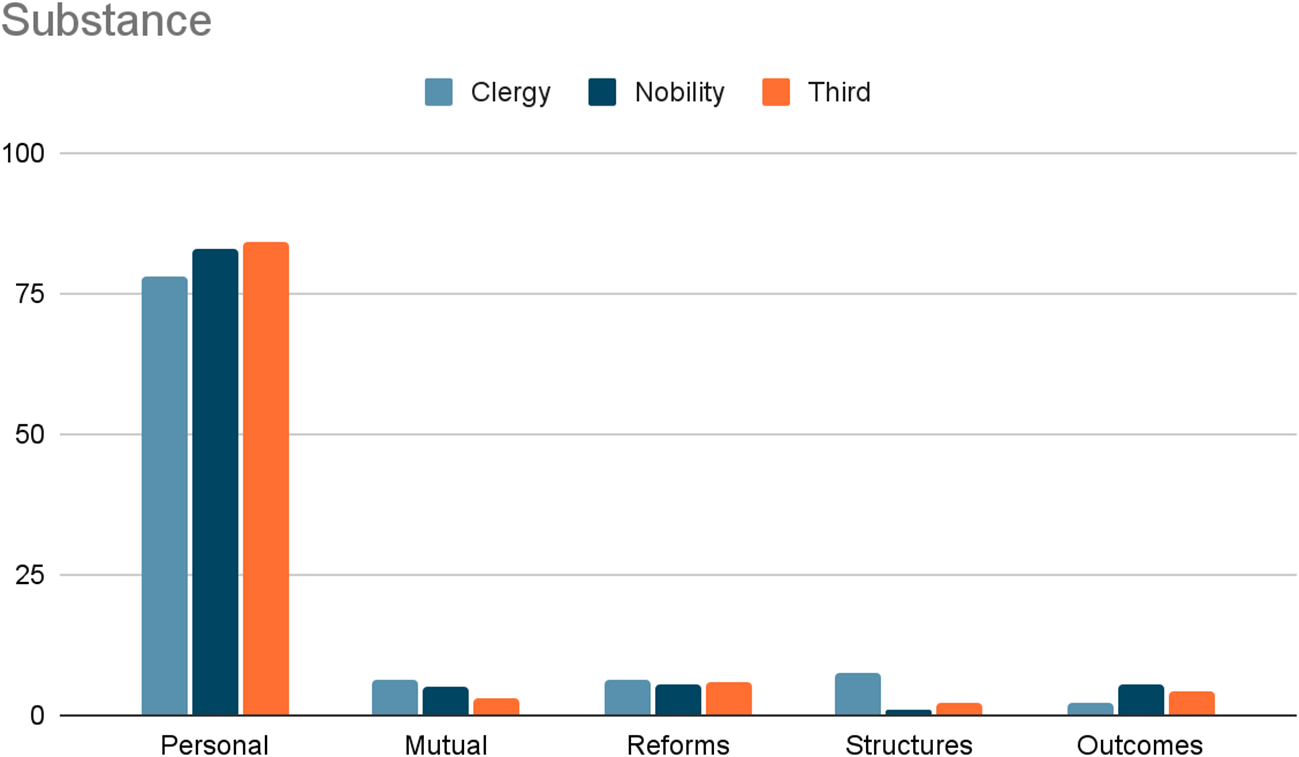

Taking a more schematic view of the areas that trust is used to discuss, Figure 4 indicates the predominance of a basic idea of trust as interpersonal, and particularly as a one-way expression of attitudes from one group towards another group or individual, and in one sense this dimension of classification serves only to pick out the very few occasions on which trust is used in other ways. The very low level of reference to mutual trust between such groups is perhaps reflective of continuing senses of the imbalance of hierarchical relationships within society. Use of trust to discuss impersonal concepts – the reform process itself (distinct from its personnel), the existing structures of society, or the desired outcomes of the Estates-General – was also at a notably low level in comparison.

Figure 4. The substance of the trusting relationships depicted in cahiers texts.

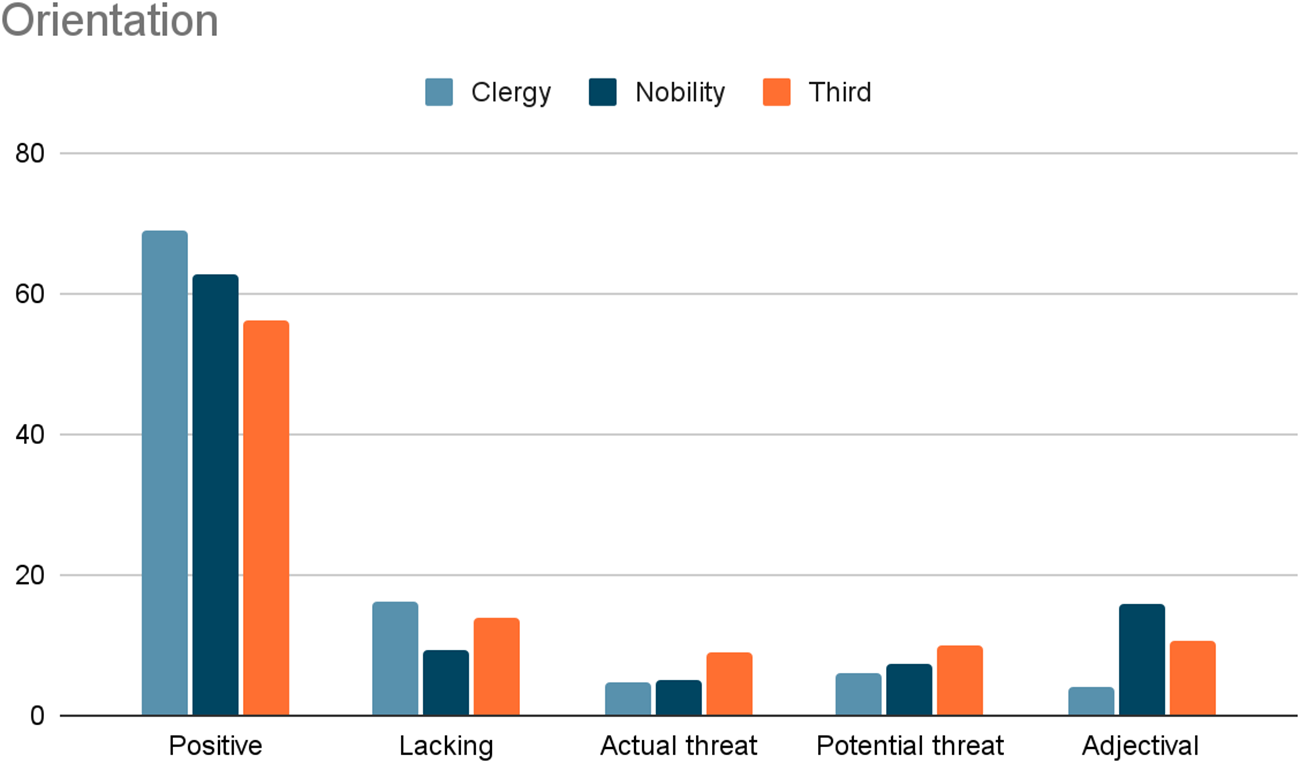

Finally, it is clear that, while trust was predominantly referenced as a positive characteristic, a notable minority of references across all three orders invoked trust as a lack in need of remedy, or as a desirable quality actually or potentially threatened by current abuses (see Figure 5). Across all three orders, this manifested the sense that trust did not simply exist but was in play politically, a stake to be won or lost that had real significance. This carries over to the adjectival use of the description de confiance, which in the great majority of cases was used to characterize personal correspondence as in need of protection from unjust and illegal administrative interception and interference, where the violation of individual and public trust was perceived as a systemic, and damning, problem.

Figure 5. The orientation of the trust identified in cahiers texts.

III

A sampling of cahiers that head the corpus alphabetically illustrates the rich tapestry of expectations and assumptions invoked by confiance, before we go on to a more selective examination of some salient groupings. The clergy of Amont, for example, in their twenty-seventh specific demand, wanted a new law on the ‘liberty of the press and the means to determine, judge and punish those who would abuse it, as well as on the inviolable security of posted letters and relations of trust’: coupling together freedom, control, punishment, and confidentiality, and marking the complex ways that power and its abuse were felt to be out of kilter in the present.Footnote 34 The same cahier also segued from ordering their deputies to the Estates to demand ‘a note of their resistance’, if their demands were not accepted by the whole body, to recording that ‘as testimony of the mutual trust of the three estates of the bailliage’; the text was read and approved by commissaires from the other two orders.Footnote 35

The clergy of Arles expressed ‘the just confiance’ that, if they agreed to new taxes and charges, the funds would pay down the national debt; those of Auch enjoined their deputy to ‘answer worthily to the trust of his constituents’; those of Auxerre asked for new regional assemblies, and full-time agents to manage the affairs of the order, ‘freely elected and always chosen amongst those ecclesiastics who would inspire trust by their talents, virtues and age, which may not be less than thirty years’.Footnote 36 In Avesnes, the clergy offered a long opening passage of ‘gratitude for the boons and the trust with which His Majesty honours us’, and went on to ask for the systematic establishment of parish schools, with ‘sufficient funds for the support of masters and mistresses worthy of public trust by their science [sic.] and their morals’.Footnote 37

The clerics of Bassigny also opened by lauding the king, ‘who honours them with his trust’. Further in to their lengthy cahier, however, they fulminated:

The expectation of impunity hardens the guilty; an ambitious and corrupt minister makes from his elevation, his authority, his power, the credit of his creatures, a shield which protects him from the blade of justice; as he now fears nothing, he exercises no restraint in his vexations, he often abuses the trust of his sovereign, appropriates unjustly the goods of the State and believes he owes no account of it to the nation.

They went on, in tones which indicate the depth of perceived crisis amongst these largely rural clerics of the southern Champagne region: ‘We expect from the justice and authority of our monarch that he will destroy this principle in delivering the guilty man to the severity of a nation whose rights he has injured, whose trust he has abused, and which has laws which should make the illustrious guilty tremble, just like the obscure criminal.’Footnote 38 Meanwhile, in Bar-sur-Seine, the clergy developed a series of reflections on what, and what not, to trust. Invoking the plenitude of their ‘trust in the sacred word of the King’, they nonetheless beseeched the periodic return of the Estates-General; they asked for justice to be fully public, to ‘conciliate the … magistrates with the respect and trust of the peoples [sic. plural]’;Footnote 39 they demanded that the Estates and the king jointly hold the power to judge ‘ministers … recognised as having abused the public trust’. Turning from general issues of policy to the particular needs of the clergy, they asked, ‘full of trust in the equity of the nation’, that parish priests might receive the full value of tithes, so often removed by historical ‘usurpation’. They asked to be able to name a single cleric ‘to conciliate the trust of all interested parties’, in managing diocesan funds. The meeting closed by offering ‘no limitation on the powers with which it charges its representative who, by his zeal and patriotism, will surely justify the trust of his constituents’: such phrasing both granting latitude and imposing a moral burden of expectation.Footnote 40

In thus scratching the surface of the cahiers corpus, we can already see that confiance exists, is threatened, withheld, and hoped-for, within a complex nexus of contemporary and historical awareness, corporate identity, and anxieties about public and private power.Footnote 41 The first noble cahier alphabetically to invoke trust, that of Agen, led with a highly personal sense of its stakes: a sixteen-point plan for establishing the permanent existence and legislative supremacy of the Estates-General, that their chosen deputies ‘may not, in any case, under any pretext, without an infidelity of which they are incapable, allow themselves to alter’. In the most binding of mandates, ‘We disavow them in advance, were they to be so culpable as not to fulfil their engagements, and strictly obey our will, without adding, removing or modifying anything.’Footnote 42 Yet they immediately followed this with the declaration that ‘We have too much trust in them, we believe them too enlightened, not to leave them all freedom’ in considering a second, even longer series of demands. Invoking confiance once again as they offered to surrender their privileges if everyone else did too, they then insisted that the national ‘deficit’ was inherently illegitimate, but they would ‘consent’ to assume it as a national debt, if the current ‘disorder of the finances’ was replaced by ‘such an order of things, that trust is reborn’.Footnote 43

The parallel Third-Estate gathering at Agen was concerned, like so many, with the future arrangement of governance. In classic form they insisted that ‘It will never be the sovereign that the nation will complain of or distrust’, but the same was not true of ministers. Future officials ‘whose talents and intentions gain little general trust’ required arrangement to expose them to ‘public opinion’ and ‘competent judges’. Their deputies’ ‘mission is a proof of the trust that the sénéchaussée has in their talents and in their merits’.Footnote 44 From Amiens, meanwhile, returning to our first theme above, the Third demanded ‘the most rigorous measures to assure the inviolability of the secrecy of the mails, being the essence of a good constitution to respect the secrecy of families, to protect reciprocal trust and to give free range to opinion’. Noting royal intentions to rely on ‘that agreement that is born from public trust’, they went on to sharply criticize venality of office, especially for judicial functions: ‘Those who exercise upon their fellows the most holy and august of ministries, no longer being called forth by the trust and the veneration of their fellow-citizens, some have believed themselves dispensed from meriting them.’Footnote 45 The juxtaposition here of public trust and its emphatic loss by the authorities was to reappear frequently.

IV

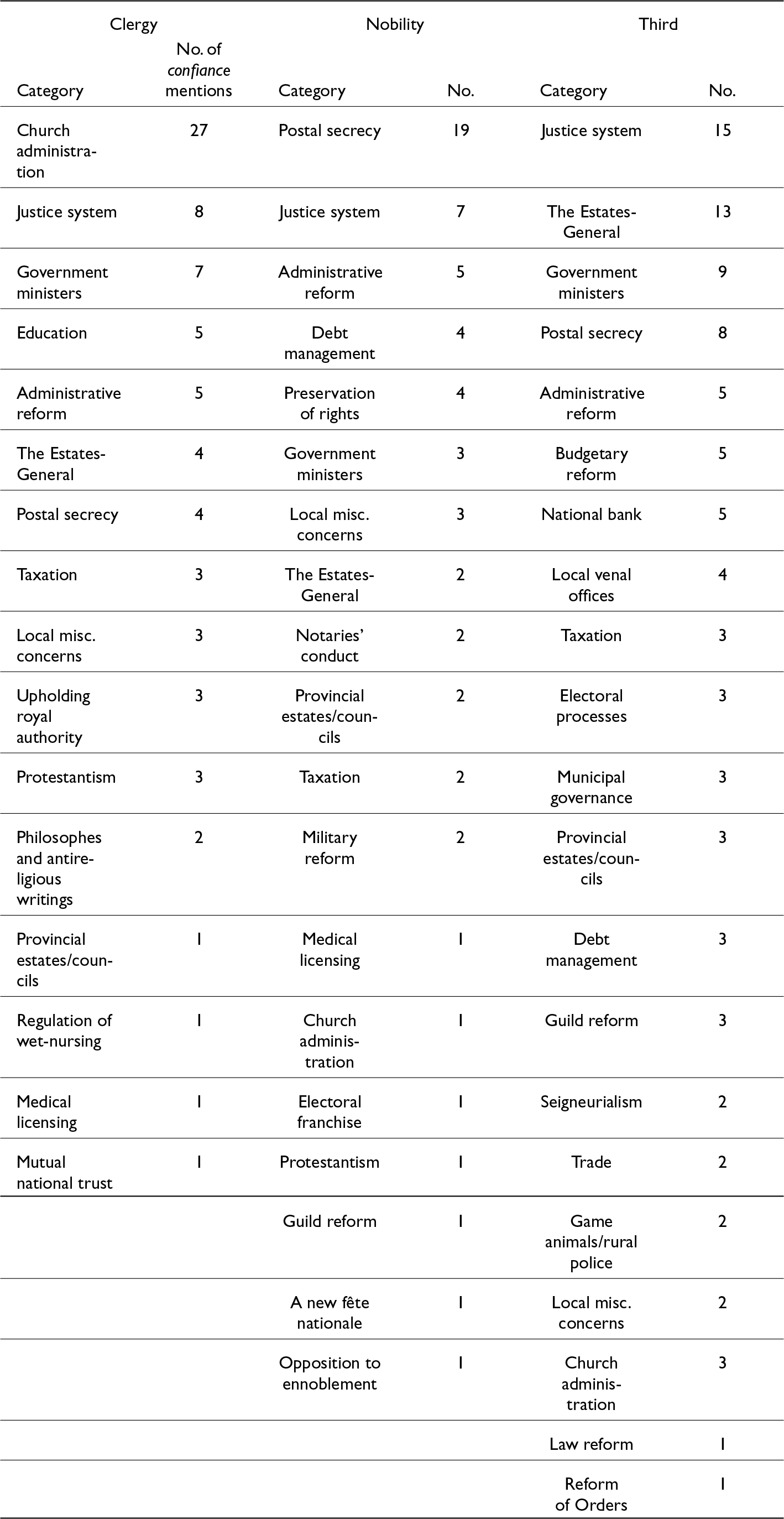

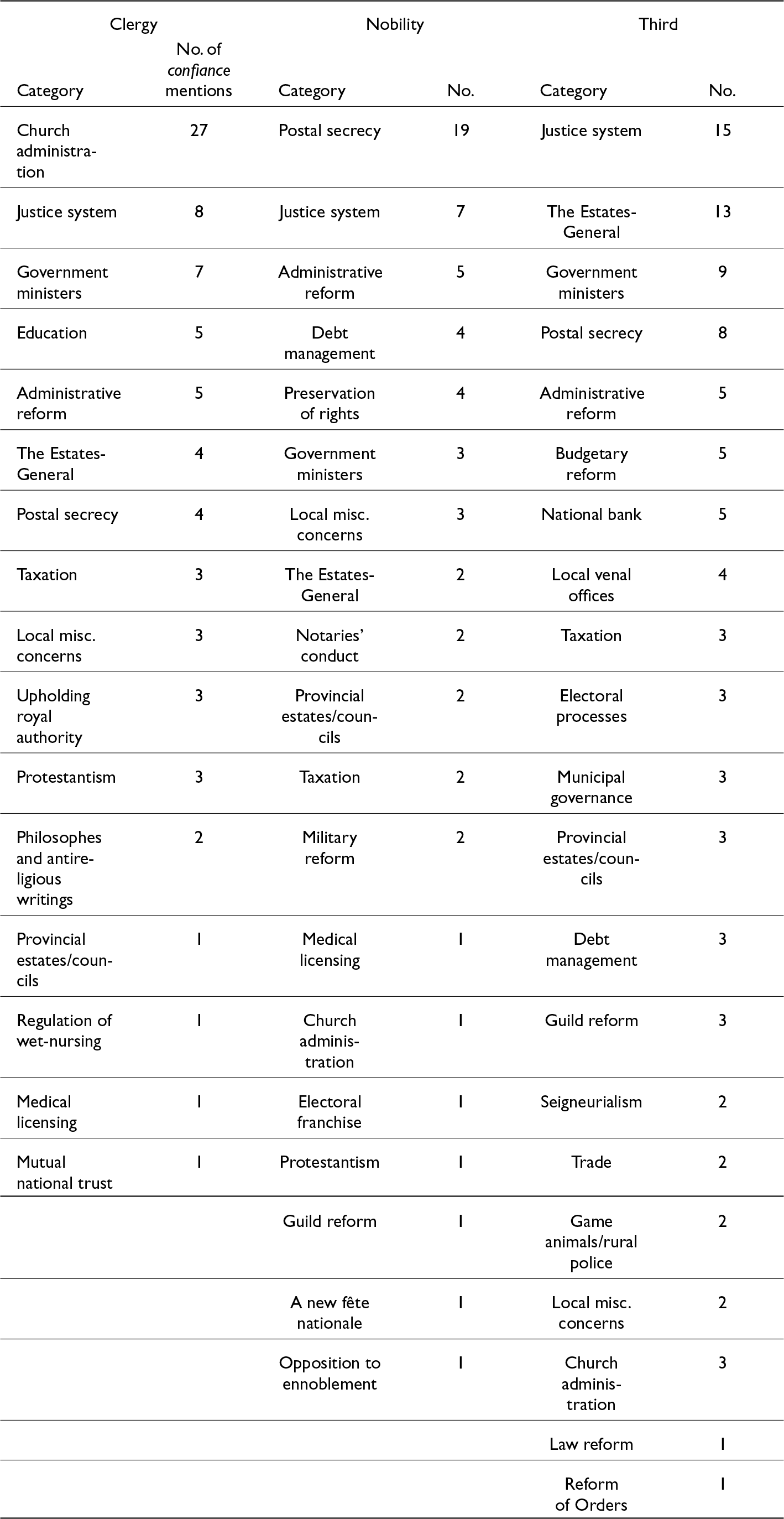

Approaching the corpus more thematically, we can examine the presence of trust in those elements of the texts that articulated specific demands for reform: the strong plurality of all instances. Here, the nobility were least likely to mention trust (fifty-seven occasions), and the Third Estate most (ninety-five), with the clergy falling almost halfway between (seventy-eight). The Third’s demands extended over more than twenty categories, and the nobility’s almost as many, while the clergy’s covered some sixteen definable topics (see Table 2).

Table 2. Thematic breakdown of topics where confiance was used to express specific demands in the cahiers, by Order.

There are few major concerns that did not cause at least one gathering to invoke trust. The relatively low salience of issues around taxation – the most-frequent of all topics in the cahiers – is noteworthy, and perhaps explicable by an assertive expectation of change in this area.Footnote 46 One topic notable by its absence is concern with the food supply, although it should be noted that only about a dozen cahiers at this level reference subsistances as a general issue at all.Footnote 47 The focus of clerical cahiers on the internal affairs of the Church, clearly taking first place in the table above, reminds us that the whole electoral process for the First Estate was a ‘revolt of the parish clergy’ against episcopal dominance.Footnote 48 Even within this single theme, trust was used to express many different relationships to the understood audience and targets of demands. The clergy of Bazas, for example, used it as a hint at moral blackmail, asking for augmentation of the inadequate portion congrue many clergy survived on, and doing so ‘with such greater trust’ because the king, ‘touched by their condition’, had issued a decree for their relief in 1785 ‘that the lack of registration had rendered without effect’.Footnote 49

Use of the language of trust to plead poverty was notable elsewhere. The priests of Grasse asked for better incomes for parish curés, but as to how, ‘we refer ourselves with complete trust to the wisdom of His Majesty and the Estates’.Footnote 50 In the Pays de Gex, the clergy were similarly ‘too full of trust in the wisdom of Your Majesty’s views’ not to hope for relief.Footnote 51 From Puy en Velay came a more pointed expectation that ‘by an honourable trust’, the nation would compel bishops to reallocate resources from themselves to the lower clergy; they also asked for the lifting of a ‘crushing surcharge’ of local taxation, ‘with that trust and liberty given by justice and the profound sentiment of a long oppression’.Footnote 52 Rivière-Verdun stressed that the casuel forcé – treating supposed fees for specific services as a compulsory tax – was ‘odious to the people and tended to destroy trust’ in the clergy, and thus should be abolished.Footnote 53 In these messages we also see the development of a tension between what some clerics were essentially pleading with the king to do, and what was expressed as an issue for the nation or the people to take charge of.

Trust could also be invoked to demand more overt structural reform. The clergy of Blois sought royal measures to impose on each bishopric ‘a council worthy of the trust of the clergy that should be consulted in important matters’.Footnote 54 The Boulonnais asked, conversely, for a national council of clerics to advise the king on senior ecclesiastical appointments, and added ‘with the most respectful submission and with a just confiance’ in the king’s intentions, that he should not ‘allow the weakening of trust owed to his royal word’ by failing to honour earlier promises of reform.Footnote 55 The clergy of Mantes made the same demand for a national body, and carefully added that ‘the trust of the King would be the sole recompense’ of such council members.Footnote 56 The clergy of Peronne, echoing the implicit tension above, highlighted that such a council would ‘inspire more trust from the King and the nation’ than a prelate who ‘disposed [of positions] as if they were his own property’.Footnote 57

If trust could be used to bolster expressions of helpless poverty and bottom-up legitimacy, it could also be used to assert entitlement and superiority, placing the body of the nation in a very different relationship to clerics. The clergy of Quercy lamented ‘the pain of seeing tithe-holding priests, forced to undertake legal action in defence of the rights of their benefices, entirely lose the trust of their parishioners, and be exposed not only to unjust refusals but also to suffer the most violent and criminal physical attacks’. Thus they asked for a law to ‘fix irrevocably’ the payment they could demand.Footnote 58 Rouen’s clergy wished in parallel to ‘re-establish the trust which must exist between them and their flocks’, by having prior legislation on such tithe payments applied more rigorously.Footnote 59 Finally, we can note the comment of the clergy of Bitche, who expressed their willingness to ‘support whatever pecuniary impositions’ were agreed, so long as they ‘do not compromise the authority and trust of pastors with their parishioners’ by subjecting clergy to tax-assessment by laypeople.Footnote 60

V

As was noted above, reference to confiance in noble demands very clearly skewed towards the issue of postal secrecy (which was also the fourth-most frequent Third-Estate topic). The specific term in these cases generally refers to the confidentiality of communications themselves. However, the concerns raised indicate a loss of trust in public authority, which could produce quite remarkably bold denunciations.Footnote 61 Some treated it as mere dysfunction, Bar-le-Duc’s nobles demanding ‘the most severe penalties’ for any postal employee opening ‘sacred and inviolable’ correspondence de confiance.Footnote 62 This escalated for others to a need for substantive reform: Quesnoy demanded that ‘the supervisors and administrators of the post will be responsible to the Estates-General … to be pursued extraordinarily, if they abuse the public trust’.Footnote 63 The Third of the Perche asked for public nominations for postal directorships ‘by reason of the trust that they require’, and insisted ‘that the secrecy of letters may not be violated by the ministry’.Footnote 64

The latter point had been taken up much more strongly by other nobles. Amiens explicitly insisted that their deputies ‘will demand’ [réclameront], and not merely ask for, ‘inviolability of lettres missives’, along with ‘the assurance that confidential relations may never become the grounds for accusations against any citizen’.Footnote 65 Blois denounced the ‘violation of the secrecy of letters’ as an ‘attack on the liberty of citizens’, and stressed that because the post had been defined as a royal monopoly, it must operate ‘under the seal of trust’.Footnote 66 Cambrai explicitly linked the abolition of arbitrary detention by lettre de cachet with the prohibition of ‘all opening of lettres missives [as] oppressive and removing all trust from society’.Footnote 67 As we saw above, the Third Estate of Amiens had invoked the ‘secret of the post’ as the ‘essence of a good constitution’, and other Third cahiers also embraced a wider diagnosis of the problem. The denizens of Amont, composing a joint cahier of all three local orders, invoked the need to punish breaches of the ‘inviolable security of lettres missives and of relations of trust’.Footnote 68 Montpellier elaborated further: ‘that the secrecy of public trust between citizens should not be given over to a revolting inquisition; that every attack on this freedom should be regarded as an infraction of public and national law’.Footnote 69

Such denunciations culminated in the cahier of the Third Estate of Nemours, with a brutally frank illumination of their subtext:

There exists a supposedly secret commission, known to everyone, which is authorised to counterfeit seals, open letters, make extracts of them, and to place them, with or without the originals, before the eyes of the King, and, depending on the occasion, the ministry.

The King has had the greatest repugnance for this establishment; he has wished to destroy it; it has been observed to him that it has been done for a long time, and throughout Europe; he has been persuaded that it may sometimes be useful. As if, when one would [anyway] suppose that no reason could excuse such an abuse of trust on the part of the chief of society, one could draw any information from letters when those who write them know that they will be read, and as if they would not make use of that conduct to draw [him] into error!

Here we see denunciation of ministerial malfeasance, so common in the cahiers, shade over into claims that are at first blush extraordinary and apparently exaggerated. Yet it was authored by no less a figure than Pierre Samuel Dupont de Nemours, who as a noted Physiocrat, ennobled royal official, and secretary to the 1787 Assembly of Notables, presumably knew whereof he spoke.Footnote 70 Having exposed the hitherto supposedly secret machinations of the royal cabinet noir, the text went on to denounce incriminating forgery engineered by foreign powers and domestic plotters, before concluding ‘The King, who will read this, will see that this fact is exact’.Footnote 71

The conviction that letters were routinely intercepted by the state was widespread: in the summer of 1789, correspondents as varied as the marquis de Ferrières and Manon Roland mentioned it. The former wrote of ‘the old resource of stopping letters’, such ‘subterranean manoeuvres’ explaining why his wife might not hear from him regularly, and the latter more intemperately cursed ‘the cowards’ who might read her words, hoping they ‘blush’ at being denounced by a woman, and ‘tremble’ for their looming fate.Footnote 72 Such jabs were in letters that nonetheless themselves remained private. The willingness of someone like Dupont de Nemours to make it public is a striking instance of the mistrust of authority, and the shrinking away of the fear of that authority, under pressure of crisis.

VI

Concerns over administrative abuse of trust can usefully be compared to the shared anxieties about judicial abuses, prominent in all three orders’ recourse to confiance. The highest judges of the land had posed for decades as the defenders of liberty against royal tyranny, only to have their backward-looking attitudes to the formation of the Estates-General cast them into public opprobrium at the end of 1788. In this context, many cahiers reflected on layers of dysfunction.Footnote 73 For some gatherings, the collision of trust and justice was primarily a problem at the local level, where villagers lived under the sway of courts run by the local seigneurs (manorial lords). The Third of Montpellier set out a detailed plan for the nominated judges of such courts to undergo ‘public and rigorous examination’ by royal courts, insisting that no lordly privilege should be allowed to ‘force the confiance of the justiciables’ in such matters.Footnote 74 Toul asked for basic judicial and arbitration powers to be placed in the hands of village municipalities, headed by men ‘elected by them and worthy of their trust’.Footnote 75 The Third of Paris offered a broader plan for elected ‘notables, honoured with the public trust’ to form tribunals covering ‘five or six villages’, again with basic powers of both judgment and arbitration.Footnote 76 The nobles of Anjou, from the other end of the social telescope, noted the importance of seigneurial rights as ‘honorific distinctions’, but agreed to ask for ‘a regulation that submits these jurisdictions to an exact surveillance, so that they may be … worthy of public trust.’Footnote 77

Other gatherings identified issues that rose up the judicial hierarchy, suggesting that mistrust was permeating the system. The Third of Bigorre specifically condemned local criminal courts as ‘too rigorous’, and particularly heinous for giving ‘too great a trust’ to the declarations of customs-farm employees, in convicting possibly innocent individuals.Footnote 78 From the same location, the clergy enunciated a plan for revised, uniform courts of first instance nationwide. ‘But, whatever trust courts thus ameliorated may inspire’, they went on, a ‘supreme tribunal that can rectify their errors’ should be retained.Footnote 79 Douai’s clerics suggested that judges should not be admitted to higher ranks unless they had ‘acquired public trust by distinguished service in a lower court or at the bar’.Footnote 80 The clergy of Libourne spelt out a full revision of the criminal justice system, starting with public trials and defence counsel, and insisting that judges had to ‘inspire trust … by their estate and their wisdom’.Footnote 81

The Third of Dinan bluntly requested the complete revision of all law-codes and the institution of uniform penalties ‘without distinction of rank or persons’, and that those convicted of ‘abuses of authority or trust’ should face fines that would be ‘applicable to the relief of the poor’.Footnote 82 Nemours demanded that courts should be formed in future ‘by an election which can assure to the magistrates the plenitude of public trust’.Footnote 83 Perpignan insisted that ‘justice should be well-administered in each province or jurisdiction in the manner most worthy of the trust of the nation’; though they added, in a classic piece of old-regime thinking, that this should be ‘while conserving to the inhabitants of the province of Roussillon the advantages’ of their current access to local viguerie courts.Footnote 84 In Quimper, overt dispute had already erupted, and the Third-Estate gathering noted that they would ‘betray the trust placed in them’ by 90,000 constituents if they failed to refer the ‘incendiary protestation’ of local judges to royal authority, and called on all Breton deputies to unite against a tribunal that dared ‘condemn at once the trust of subjects and the goodness of the monarch’.Footnote 85

Amongst the nobility, Auxerre asked directly for the end of judicial venality, ‘since [such offices] ought to be accorded only to citizens who have merited, by their work, their probity and their experience, the trust of the nation’.Footnote 86 Etain sought to cement the independence of the higher courts, insisting that their decrees ‘both in civil and criminal matters, should be unquestionable and without appeal’, once ‘reform of the abuses relative to the exercise of justice’ had made such courts ‘worthy of the trust of the nation’.Footnote 87 Fourcalquier briskly summed up an entire programme of reform: ‘Venality of office will be abolished, the funds reimbursed; the magistrates, salaried honestly, will be people of capacity, probity and experience. They will enjoy public trust if they are put forward by the assemblies of their respective districts.’Footnote 88 Macon asserted even more briefly that ‘the composition of courts should be such that the judges are enlightened, honoured with general trust, and that public opinion may influence their choice’.Footnote 89

While these demands seemed to lean towards a conception of popular judicial legitimacy, a final, striking suggestion, and a reminder that the language of trust was not always libertarian, came from the clergy of Chalons-sur-Marne. They suggested that what the nation needed was a network of tribunaux de confiance that would operate ‘under the seal of secrecy’ to issue ‘extraordinary orders to families for the detention of a subject who would compromise their honour, if they had recourse to the publicity and the delays of ordinary procedures’ – essentially lettres de cachet under judicial cover.Footnote 90

VII

Right at the top of politics, ministers were firmly targeted in many cahiers. The extent to which it was assumed they held the trust of the monarch interacted notably with the sense that the trust of the nation was also required.Footnote 91 There was a sharp contrast, expressed across all three orders, between attitudes to Necker and other, actual or hypothetical, ministers. Montreuil-sur-Mer’s nobles segued from ‘entire trust’ in Necker to urging the king, ‘without terror and without fear, with trust and freedom’, to now ‘close all access to favour and intrigue’.Footnote 92 In Lixheim the ‘first two orders’ united in a cahier that targeted ministers bluntly, ending the claims of absolutism in one long, minatory sentence:

That every minister who would have attempted to make arbitrary changes, either in the laws, or in the duration and weight of taxation, or who would have given advice tending to establish an arbitrary authority, destroying that trust which founds the power of kings, should be cited and judged by twelve judges named in the Estates-General of the kingdom.Footnote 93

Carcassonne’s nobles also deployed constitutional heavy artillery:

The Estates[-General] will have the right to accuse and to send before the courts any minister who would have formed enterprises tending to overturn or unsettle the constitution, to divert public monies from the usage assigned by the Estates, to abuse the name and authority of the sovereign to attack the security of the citizen, to betray the trust of the prince, and suggest acts contrary to the always-inseparable interests of the King and the nation.Footnote 94

The sense here that the nation was literally under threat from its government is striking. Similar patterns were on display in Third-Estate cahiers. Chalons-sur-Marne and five others invoked trust in Necker.Footnote 95 Hagenau, on the other hand, noted that ‘the too-frequent abuses that the ministers of His Majesty have made of his trust must make the nation desire to render them responsible for their conduct’; Gueret noted of such a change that ‘nothing is more capable of inspiring [the nation’s] trust and assuring its happiness’; and Draguignan pleaded with the king for ‘inflexible justice’, resisting any urge towards ‘pardoning the corrupt minister, enemy of the State, who would abuse his trust and the last efforts of his people’ – a reminder that Calonne was still understood as a criminal by many.Footnote 96 Chatellerault put a unique spin on the situation by demanding security of tenure (inamovibilité) for ‘both civil and military’ positions, ‘given that the nation cannot accord its trust to officers who would be in a servile dependence upon the minister’.Footnote 97

Ministerial power was intrinsically connected to the ongoing debt crisis, which caused cahiers to invoke trust in further intricate ways. The clergy of Meaux, for example, took a pro-finance line, demanding a full recognition of the whole ‘debt of the State’, ‘because every creditor of the State must be able to transact with trust’ and it was ‘unjust to make him bear the penalty for errors of government’.Footnote 98 Rouen’s clergy, on the other hand, lamented the ‘imprudent trust’ that had led to ‘multiple loans’ burdening the kingdom, and demanded that in future, to ‘invariably fix public trust’, any such loans would require the ‘consent of the nation’.Footnote 99 Clerics in Arles and Nîmes both consented to more uniform taxation regimes, but both invoked the ‘just confiance’ that such payments would defray a genuinely national debt, and in the case of Nîmes, sought in return for the dette particulière of the clergy to ‘be regarded, from this moment, as a debt of the State’.Footnote 100

Amongst the nobility, in Rivière-Verdun the assembly took a positive tone, ‘full of trust in the King’s justice, the wisdom of his minister, and the patriotism of the nation’s representatives’, empowering their deputy to sanction all governmental debt, after having prudently ‘verified the titles upon which it is established’.Footnote 101 Montargis went even further: ‘convinced of the necessity to restore calm to the souls of the State’s creditors, and have trust reborn’, they ‘enjoined’ their deputy to ask the Estates to ‘consolidate the debt without any delay, and recognise it as national debt’.Footnote 102 Lyon’s nobles were a little more sceptical, asking not only for debts to be ‘recognised and clarified [constatée]’, but also then converted into regular ‘contracts in order to eliminate speculation’ and which could then be taxed – rightly, because ‘the nation’s guarantee will give to them a degree of certainty and trust that they could not reasonably obtain until now’.Footnote 103 The meeting at Coutances spelled out what was implicit in some of these requests: they wanted a full accounting to the Estates of the ‘debts of the royal treasury’, and examination to result in those ‘illegitimate in their origins’ being repudiated, and those ‘illegitimate in their amount’ being ‘reduced to their just total’, all of them having been ‘surprised by an abuse of the King’s trust’. Only then should the Estates consent to the payment of a consolidated ‘national debt’, and the requisite taxes and further loans.Footnote 104

Third-Estate cahiers were relatively less concerned with yoking debt and trust, but in the three cases that mentioned it there remained divergent understanding, and seeds of future tension with some of the views above. Bar-sur-Seine centred the concerns of ‘creditors of the State’ and the public desire to ‘have trust reborn’, while also gently nudging the question of ‘the total sum of legitimate debts’ that should be ‘declared national’. Montargis spoke essentially of a process of recognition and acknowledgement of debts, and of the Estates finding a way to approach their ‘amount and liquidation’ that responded to ‘the dignity of a great kingdom and public trust’. Mont-de-Marsan, in contrast, aggressively forbade their deputies ‘to make the least retrenchment [or] contest the legitimacy’ of any debts, enjoining them ‘to the contrary to fortify credit and public trust, in declaring the debt [to be] national, and guaranteeing thereby its entire repayment’ – which was, as noted above, to be the first substantive act of the National Assembly.Footnote 105

VIII

At this point, we can turn to an examination of attitudes to the deputies who were destined to take such bold action. A first point is that the stark divide between nobles and commoners that so rapidly overtook the Estates from May 1789 is not overtly present in this corpus.Footnote 106 The main concern was insistence on reform against imagined ministerial resistance. As we noted above, the nobles of Agen extensively connected trust in their deputy with a watchful regard for his actual conduct, firm expectations of specific actions, and admonitions against failure or seduction. Armagnac similarly noted bluntly that ‘we will withdraw from him our trust and our powers, and declare him incapable of binding us by his consent’ if their deputy voted for new taxes before imposing reforms. Aval insisted on their ‘right to demand … zeal, constancy and vigilance’ from those ‘honoured with the deposit of [their] trust’, while ‘expressly forbidding’ them from accepting any ‘grace, place, pensions or gratuities’ or other form of ‘seductions’.Footnote 107 Briey noted, as Agen had, that their deputy would be ‘formally disavowed and … stripped of his powers’ and, like Armagnac’s, ‘incapable of binding us by his consent’, as well as ‘forever unworthy of our trust’ if he did not hold out for reform.Footnote 108 Saumur enjoined its deputies at length over the ‘recognition of the rights of the nation, and the establishment of the constitution’: on these matters, deputies were ‘submitted to the conditions … imposed’ on them by the gathering, and could only ‘answer the trust of the order, and merit its esteem’ in holding to those principles and rights.Footnote 109

Other noble assemblies were less aggressive in their language. At Pont-à-Mousson, the deputies were told to ‘respond to [the king’s] trust by an absolute sacrifice of their own interests’.Footnote 110 Avesnes enjoined their deputy to proceed ‘by patience and firmness’ to secure their desired reforms, and in so doing he ‘will respond worthily to the trust of his constituents’.Footnote 111 Some gatherings went further: the Haute-Marche, ‘knowing the sentiments of honour, patriotism, wisdom and lumières’ of its deputies, was happy ‘to prove to them their trust’ in authorizing them to ‘deliberate, order and decree all that they shall judge necessary for the good of the State’.Footnote 112 While Nîmes, on the contrary, ‘enjoined’ its deputies to ‘hold themselves strictly’ to a mandate for specific listed reforms, ‘with which their honour and trust are charged’, Nancy instructed theirs that they were free to propose and request ‘all that they shall estimate to the advantage and greater good of the province and kingdom’, having placed ‘the most entire trust in their wisdom and in the activity of their zeal’.Footnote 113

For some, the process of choosing a deputy involved an even more direct surrender to his discretion. The Bourbonnais, giving their deputies ‘the most honourable mark of our trust, in putting our dearest interests in your hands’, were ‘convinced’ that they would honour this as ‘the most sacred law’ and in consequence ‘the only limits we give you, will be our sentiments’.Footnote 114 In Sens, the ‘noble order … placing the greatest trust in the deputy it has chosen’, yielded ‘entirely to his prudence regarding the part to take in discussion of objects concerning the public good’.Footnote 115 In Bar-sur-Seine the nobles observed that their cahier contained ‘rather instructions than orders’, and the deputies’ ‘powers were as extensive as the trust they have inspired; they must be unlimited, because nothing must halt the action of the Estates-General’.Footnote 116

Other approaches were more nuanced. The Nivernais affirmed that their deputies would ‘respond with zeal and integrity to the trust placed in them’, while also not forgetting ‘that they belong to France before belonging to their province, and they are citizens before being nobles’ – an inversion of many emergent attitudes in the months ahead.Footnote 117 Saintonge noted it was their deputies’ role to ‘establish the bases of the constitution and administration on solid foundations of justice and trust’, that they expected them to ‘justify by their conduct the trust we have honoured them with’, following the ‘patriotic spirit’ of their instructions, and that ultimately ‘on the manner in which they answer our trust depends the judgement that posterity will make of them’.Footnote 118 The Bas-Vivarais invoked their ‘most respectful trust’ in receiving justice from the nation, going on to charge their deputies to follow ‘after the most mature examination, the part that their wisdom and their conscience will make them prefer’, recognizing they were ‘charged with the sacred deposit of the trust of their order’. Uniquely in this context, they added a further requirement: ‘it is ordered to the deputies to bring themselves to Villeneuve-le-Berg, forty days after the closure of the Estates’, so that there the assembled order could ‘honour them with the testimony of their esteem’, or alternately ‘declare them forever unworthy of their trust, if they have betrayed the sanctity of their ministry’.Footnote 119

The clergy who addressed their deputies with a language of trust were generally less minatory about its implications. Bar-sur-Seine and Mirecourt, for example, both noted specifically that they were placing no limitation on deputies’ powers, trusting to their ‘zeal and … patriotism’ and their ‘honour and … patriotism’ respectively.Footnote 120 Parisian clerics asked their deputies to express their ‘respectful trust in their King’ while exercising ‘all power to propose, advise and consent’ that they granted them.Footnote 121 Other expressions slid towards commands: Beauvais ‘enjoined’ its deputy ‘in the name of the trust it places in him’ to use his zeal and ‘love of the patrie’ to stand up for the permanent existence of the Estates-General.Footnote 122 Melun pushed their deputy to ‘not forget that he will hold in his hands the sacred deposit of trust and the interests of the whole bailliage’.Footnote 123 Castelnaudary’s deputy ‘must always remember’ that the ‘order of the clergy has only given him their trust so that he may defend with all the zeal of which he is capable all the petitions contained in the present cahier, of which he may neglect absolutely none’.Footnote 124

Observations to their deputies from Third-Estate meetings rang the changes on many of these themes. Arles used the language of disavowal, and being ‘unworthy of our trust and unseated by the sole fact of our powers’ to warn, as various nobles had, against voting new taxes without embedding reforms. The Bourbonnais commoners invoked the ‘noble and decent firmness’ with which its deputies should ‘make heard our just complaints’ and thus ‘answer to our trust’.Footnote 125 Gueret, ‘full of trust in the wisdom and lumières’ of its deputies, gave them ‘general and sufficient powers to propose, remonstrate, advise and consent’ in all matters. The assembly at Limoux gave ‘absolute power’ to do likewise in expressing its ‘trust in those who will be its organs’, having somewhat contradictorily earlier ‘assured them of a trust without limits’, but also required them to ‘limit their ministry to being the defenders and organs’ of the ‘public voice’ – a ‘powerful voice that could not lead them astray’.Footnote 126

Reference to a wider public also appeared in Clermont-Ferrand, where ‘the trust of your fellow citizens’ imposed ‘great obligations’, but also the ‘great guides’ of conscience and honour. Nîmes offered an exhortation to deputies to ‘make themselves worthy of the trust of their fellow-citizens’.Footnote 127 Riom and the Pays de Caux, at opposite ends of the country, both noted that their deputies were ‘called by the esteem and trust’ of their fellow-citizens, and exhorted them to ‘recognise all the dignity of their mission’, and to agree to nothing ‘against the wishes or to the prejudice of the interest of all’.Footnote 128 The Nivernais assembly sternly reminded its deputies that if they yielded to ‘seduction’ and thus ‘basely abandon the defence of their constituents, they will be declared and reputed traitors to the patrie and henceforth unworthy of the trust of their [fellow-]citizens’.Footnote 129 The idea of responsibility to a national public was counterpointed sharply by the Third of Auch, who declared that their deputies were not to yield even ‘following the plurality of votes’ in the Estates-General itself without demanding sight of the cahiers that contradicted them, and should they ‘by condescension or weakness … join with contrary wishes’ to those expressed in their own text, ‘they will be declared unworthy of the trust with which they have been honoured, unfaithful to their mandates, [and] pursued even according to the rigour of the law, by reason of the faith they will have violated’.Footnote 130

IX

The cahiers of 1789 offer the reader an entire landscape of attitudes and desires, from a nation certain that it was in crisis, and that change was essential, but uncertain about almost everything else. It is a terrain so vast that it will always be difficult to map: there are approaching four million words of discourse in the cahiers collated by the Archives parlementaires alone.Footnote 131 Trust functions as one window onto this landscape. A few hundred mentions of the word confiance may seem insignificant amongst this mass. But this article has shown that, across more than four in five of the Estates-General’s electoral districts, gatherings of dozens, sometimes hundreds of individuals – many of them picked by their own communities to stand for them – chose to use confiance in a wide variety of ways that were clearly meaningful to them, and frequently bore an evident emotional charge in drawing together their identities, concerns, fears, and aspirations. Summoned into being with a language of unconditional and submissive confiance from the crown’s officials, these assemblies set out in detail how their trust was in fact conditional and assertive, a high standard and an exacting expectation. The documents they left behind manifest their desire to have and to keep political agency, and to actively maintain a relationship between their local wishes and the evolution of national structures.

It is a staple of modern historiography to observe how the deputies of the Estates-General moved, before and after it became the National Assembly, towards positions of ideological polarization, where the detailed desires of the cahiers’ authors seemed to become irrelevant.Footnote 132 This is not to posit any moral failing in those deputies: their sense of duty towards their constituents, and of being actively engaged in dialogue with them, with their interests at heart, is palpable in the voluminous correspondence on which scholars such as Timothy Tackett have drawn. But in a context where the state appeared to be undergoing collapse from the top down, while social order seemed dangerously close to dissolving from the bottom up, the dynamic pressure to contemplate a reconstruction that would re-concentrate power usefully at that top came to be irresistible.Footnote 133 Especially as the enemies of all reform increasingly focused on a refusal based in historic provincial and sectional entitlements. To act in the general interests of all the French, deputies settled, by the end of the summer of 1789, on a mode of reform that left particular interests by the wayside.

The Assembly, while fervently adopting the language of the ‘rights of man’, used the concept of national sovereignty to build a constitutional structure that strove to make local political initiative difficult, if not impossible (because, seen idealistically, it should be unnecessary).Footnote 134 Even before debating the details of the franchise, deputies had agreed that all future official structures from the village upwards would be elective in their formation, but purely administrative in function. As such, they were all to be ‘subordinated directly to the King, as supreme administrator’, in a hierarchical apparatus where those below were bound by an ‘immediate submission’ to higher authority.Footnote 135 There was to be no political input from the kinds of gathering that had produced the cahiers, or any other. Debate on the details of this system, under the pressure of a constantly lurking counter-revolution, brought forth attitudes and resultant rulings that displayed significant distrust of the notional average voter, and a determination to hedge such men’s conduct around with defensive walls of centralizing authority.Footnote 136 These were impulses that would carry over, through the crisis of war, into the era of the First Republic, and beyond.Footnote 137

Yet, as we know from a whole field of historiography, local communities and their leaderships continued to strive for autonomy. This was clear in the relatively benign context of contestation for the placement of new local boundaries and capitals in 1790, as localities bombarded Paris with correspondence, and frequently with active lobbying delegations, desperately concerned to secure material and honorific advantages for their towns.Footnote 138 It remained a critical component of the increasingly agonizing struggles of 1791–4, when dissent and treason became indistinguishable, and two different civil wars almost tore the nation apart.Footnote 139 It was an essential underpinning of the grimly cynical relationship to state power and social order that marked the last years of the decade.Footnote 140 Political relationships amongst the French people – or peoples – were thrown into turmoil in 1789, and would take decades to settle into a stable new order. One reading of the cahiers is as a way to understand the rich complexity of political agency claimed by their thousands of collective authors – in particular here, their sense of their right to bestow and withhold trust from the ‘bottom’ to the ‘top’ of the national community – and to see this as a route to understanding more deeply why the drastic imposition of fictive national unity and unanimity from 1789 onwards was contested so strongly.

Acknowledgements

The support and guidance of the editors and reviewers for the Historical Journal are gratefully acknowledged, along with the encouraging interest of an assortment of audiences, online and in person, over the years 2021–4. Robert Blackman’s thoughtful comments on an early draft were particularly welcome, with many thanks.

Funding statement

Research underpinning this article was supported by the Leverhulme Trust, grant no. MRF–2020–108, whose flexibility and understanding of shifting possibilities through the continuing Covid crisis is very gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The author declares none.