Introduction

Candida auris is an emerging fungus that is highly transmissible in healthcare settings and frequently multidrug-resistant. Reference Benedict, Forsberg, Gold, Baggs and Lyman1–Reference Lionakis and Chowdhary3 Healthcare-associated outbreaks with C. auris are increasingly reported, and invasive infections are associated with substantial mortality. Reference Lyman, Forsberg, Sexton, Chow, Lockhart and Jackson2,Reference Lionakis and Chowdhary3 The World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Public Health Agency of Canada have identified C. auris as a critical and urgent threat. 4–6 As emphasized in several recent national guidelines, effective infection prevention and control (IPAC) practices and laboratory capacity for surveillance, identification and management of colonized/infected patients are vital to prevent transmission in healthcare facilities. 7–9

In Canada, C. auris was first identified in 2012. The first multidrug-resistant case was reported in 2017, and hospital transmission was first reported in 2018. Reference De Luca, Alexander and Dingle10–Reference Eckbo, Wong, Bharat, Cameron-Lane, Hoang, Dawar and Charles12 In 2018, the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP), a national collaboration between the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Canada that represents approximately 37% of acute care hospital beds in the country, surveyed member hospitals to assess preparedness for C. auris, and identified significant gaps in both IPAC and microbiology laboratory capacity. 13,Reference Garcia-Jeldes, Mitchell, Bharat, McGeer and Group14 As of September 2024, a total of 62 patients colonized/infected with C. auris have been identified in Canada, with evidence of clonal transmission within hospitals. Reference Eckbo, Wong, Bharat, Cameron-Lane, Hoang, Dawar and Charles12,15 Given the increasing recognition of C. auris in Canadian hospitals, CNISP hospitals were re-surveyed in 2024 to evaluate progress in C. auris preparedness.

Methods

The 2018 surveys were updated, resulting in 14 IPAC and 15 microbiology laboratory questions (see Supplementary Material). The surveys were emailed to the 109 CNISP hospitals and the 33 microbiology laboratories that serve them in June 2024, with a link via LimeSurvey (https://www.limesurvey.org/), followed by three reminders. Responses were described using medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables and counts with percentages for categorical variables. Responses were compared between pediatric specialty and adult/mixed hospitals, across geographic regions, and between hospitals with and without identified cases of C. auris, using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Among hospitals and laboratories completing both the 2018 and 2024 surveys, responses from the two surveys were compared using McNemar’s test. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) and R version 4.4.2 (Vienna, Austria).

Results

Completed IPAC surveys were received from all 109 CNISP hospitals, 12 (11%) of which were pediatric specialty hospitals. With regard to geographic distribution, 40% (44/109) were in Western Canada (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba), 36% (39/109) were in Central Canada (Ontario, Québec, Nunavut), and 24% (26/109) were in Eastern Canada (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland, and Labrador). Median hospital bed size was 178 beds (range <5 to 1105). Most hospitals have not encountered a patient colonized/infected with C. auris: between January 1, 2012 and September 30, 2024, 27 patients (median 1 per hospital, range 1 to 4) colonized/infected with C. auris had been identified in 17 (16%) CNISP hospitals. Information on receipt of healthcare abroad was available for 16 of the 19 cases identified after January 2019, when active surveillance for C. auris was implemented across CNISP hospitals. Of these cases, 11 (69%) reported recent hospitalization outside of Canada.

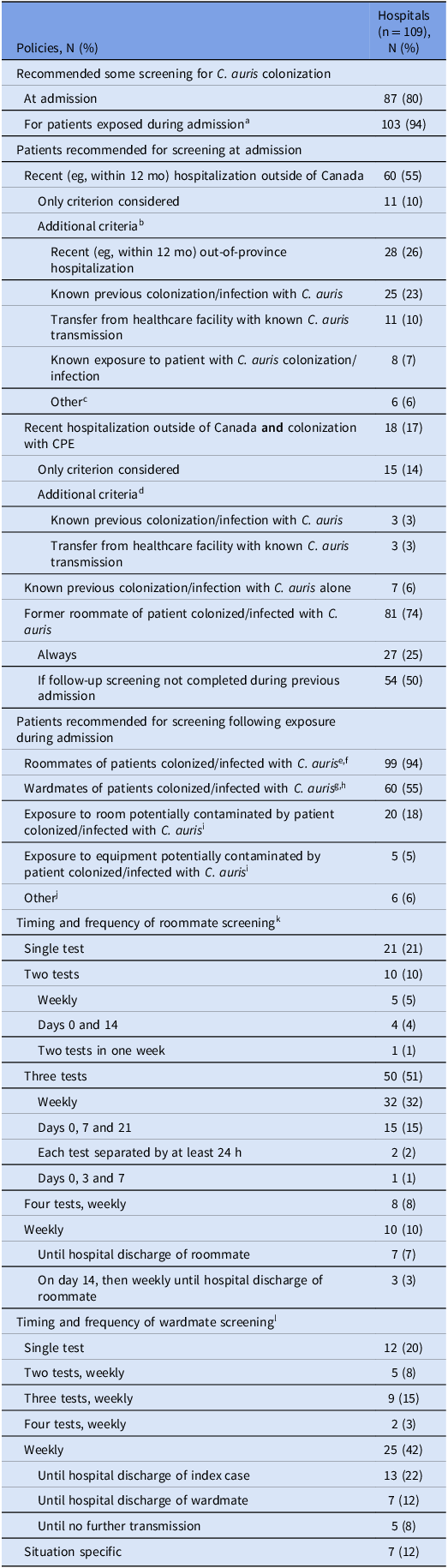

Overall, 80% (87/109) of CNISP hospitals had a policy for screening for C. auris colonization at hospital admission. The majority (69%, 60/87) recommended screening for patients recently (eg, in the past 12 months) hospitalized outside of Canada. Among these, 82% (49/60) recommended screening of additional patient groups (Table 1). Twenty-five hospitals (29%, 25/87) were more restricted in admission screening, most commonly recommending screening for patients with recent hospitalization outside of Canada who were also colonized with carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales. All but two hospitals that did not screen for out-of-country hospitalization reported they would do so if there were no resource limitations, and 12 hospitals (11%, 12/109) indicated they would screen all admissions if they had sufficient resources.

Table 1. Policies related to patient screening to detect Candida auris colonization in Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program hospitals, 2024

Abbreviations: CPE, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales.

a Of the 103 hospitals that recommended screening for patients exposed during admission, 93 had a policy and 10 did not have a policy but described a specific plan for screening. 1 hospital had a policy but did not recommend post-exposure screening, and was therefore not included.

b Of the 49 hospitals that recommended screening for additional criteria, 29 recommended screening for 1 additional criterion, 9 for 2 additional criteria, and 11 for 3 additional criteria. Sum of additional criteria considered is therefore greater than 49.

c Other included colonization/infection with CPE (4), admission to intensive care unit (1), receipt of healthcare not requiring hospitalization (eg, hemodialysis, day surgery) outside of Canada (1).

d All 3 hospitals that recommended screening for additional criteria performed screening for both criteria listed. Sum of additional criteria considered is therefore greater than 3.

e Denominator of 105, excluding 4 hospitals that had exclusively private rooms.

f Of the 99 hospitals that screened roommates, 89 had a policy and 10 did not have a policy but described a specific plan for screening.

g Of the 60 hospitals that screened wardmates, 51 had a policy and 9 did not have a policy but described a specific plan for screening.

h 7 hospitals only screened wardmates in rooms directly beside and across hall from index case.

i Numbers may be underestimated as these options were not listed specifically on the survey, but written in by respondents as “Other”.

j Other included point prevalence surveys in high-risk units (eg, intensive care unit, hematology-oncology unit) (4), at discretion of infection prevention and control (2).

k Denominator of 99, excluding 6 hospitals that did not screen roommates and 4 hospitals with only private rooms.

l Denominator of 60, excluding 49 hospitals that did not screen wardmates.

Most (86%, 94/109) hospitals had a policy for screening patients exposed to C. auris during hospitalization, one of whom did not recommend doing so. An additional 9% (10/109) reported not having a formal policy, but having specific plans for screening in the event that exposure occurred. Cumulatively, 94% (99/105: excluding four hospitals with only private rooms) of hospitals recommended screening roommates and 55% (60/109) recommended screening wardmates. Hospital policies varied widely in the number and frequency of follow-up screening tests recommended for both roommates and wardmates (Table 1). Most hospitals (61%, 64/105; excluding four hospitals with only private rooms) recommended roommates be managed with transmission-based precautions until at least two follow-up screens were negative or until hospital discharge (Table 2). Overall, among 56 hospitals completing both 2018 and 2024 surveys, the presence of any screening policy increased from 18% to 73% (P < 0.001).

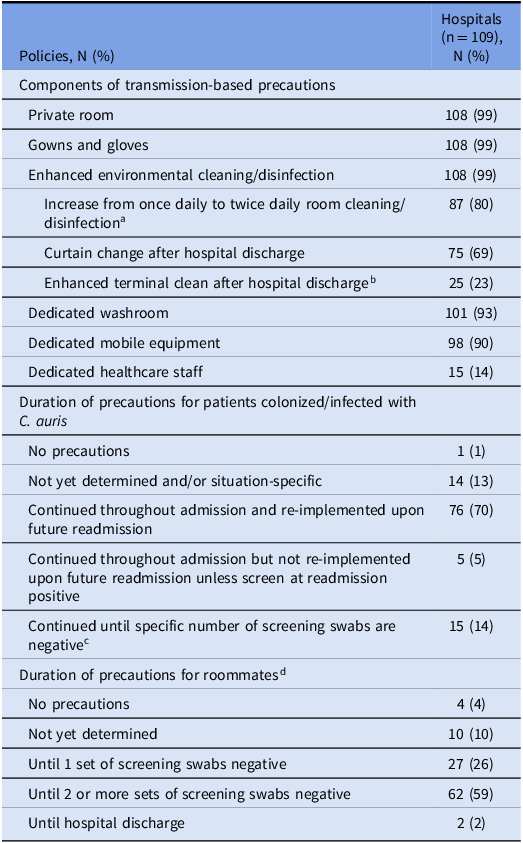

Table 2. Policies related to transmission-based precautions for patients colonized/infected with or exposed to Candida auris in Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program hospitals, 2024

a In addition to twice daily room cleaning/disinfection, 7 hospitals changed from alcohol-based hand rub to sporicidal wipes and soap/water, and 1 hospital added steam cleaning of drains.

b Among hospitals that specified components of enhanced terminal clean, 9 used hydrogen peroxide fogging or ultraviolet light disinfection, 3 performed double cleaning/disinfection, 3 performed triple cleaning/disinfection, 1 required environmental services supervisor inspection after terminal clean, and 1 performed environmental sampling before room was re-opened.

c 1 negative set (2), 2 negative sets (5), 3 negative sets (8).

d Denominator of 105, excluding 4 hospitals that only had private rooms.

All but one small, rural hospital (<30 beds) reported recommending transmission-based precautions for patients colonized with C. auris, including private room, donning of gowns and gloves, and enhanced cleaning/disinfection. Dedicated washroom and dedicated mobile equipment were required by 93% (101/109) and 90% (98/109) of hospitals, respectively. Either accelerated hydrogen peroxide or sodium hypochlorite-based products were used for environmental disinfection by 94% (103/109) of hospitals. For C. auris colonized/infected patients, 70% (76/109) of hospitals recommended continuing transmission-based precautions indefinitely (Table 2).

Pediatric hospitals were less likely than adult/mixed hospitals to perform any screening at admission (33% (4/12) vs 86% (83/97), P < 0.001), to screen at admission for recent out-of-country hospitalization (25% (3/12) vs 59% (57/97), P = 0.03), to screen wardmates (33% (4/12) vs 58% (56/97), P = 0.04), to continue transmission-based precautions indefinitely for patients colonized/infected with C. auris (42% (5/12) vs 73% (71/97), P = 0.04), and to continue precautions for roommates until one or more screening swabs were negative or until hospital discharge (55% (5/9) vs 90% (86/96), P = 0.04) (Supplementary Table 1). Hospitals in Western Canada were less likely to screen wardmates than hospitals in Central and Eastern Canada (32% (14/44) vs 82% (32/39) and 54% (14/26), respectively, P < 0.001). They were also less likely to screen at admission for recent out-of-country hospitalization (23% (10/44) vs 69% (27/39) and 88% (23/26), respectively, P < 0.001). Hospitals in Western and Central Canada were more likely to collect multiple sets of post-exposure screening swabs for roommates compared to hospitals in Eastern Canada, the majority of which collected a single set (95% (40/42) and 94% (32/34), respectively vs 26% (6/23), P < 0.001). Hospitals in Central Canada were more likely to require multiple sets of negative screening swabs to discontinue precautions for roommates than hospitals in Western and Eastern Canada (95% (35/37) vs 67% (29/43) and 56% (14/25), respectively, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 2). Hospitals with previously identified cases of C. auris were more likely than hospitals without previous cases to continue post-exposure screening for roommates until discharge (29% (5/17) vs 6% (5/82), P = 0.02) and to collect multiple sets of post-exposure screening swabs for roommates (94% (16/17) vs 76% (62/82), p = 0.02) (Supplementary Table 3).

Of the 83% (90/109) of hospitals that provided data on specimen types recommended for screening, 44% (40/90) recommended pooled axilla and groin swabs, 40% (36/90) recommended separate axilla and groin swabs, and 16% (14/90) recommended pooled axilla, groin and nares swabs. Among these hospitals, 29% (26/90), 17% (15/90), 16% (14/90), and 8% (7/90) also recommended screening wounds and exit sites (if present), urine, nares and rectum, respectively.

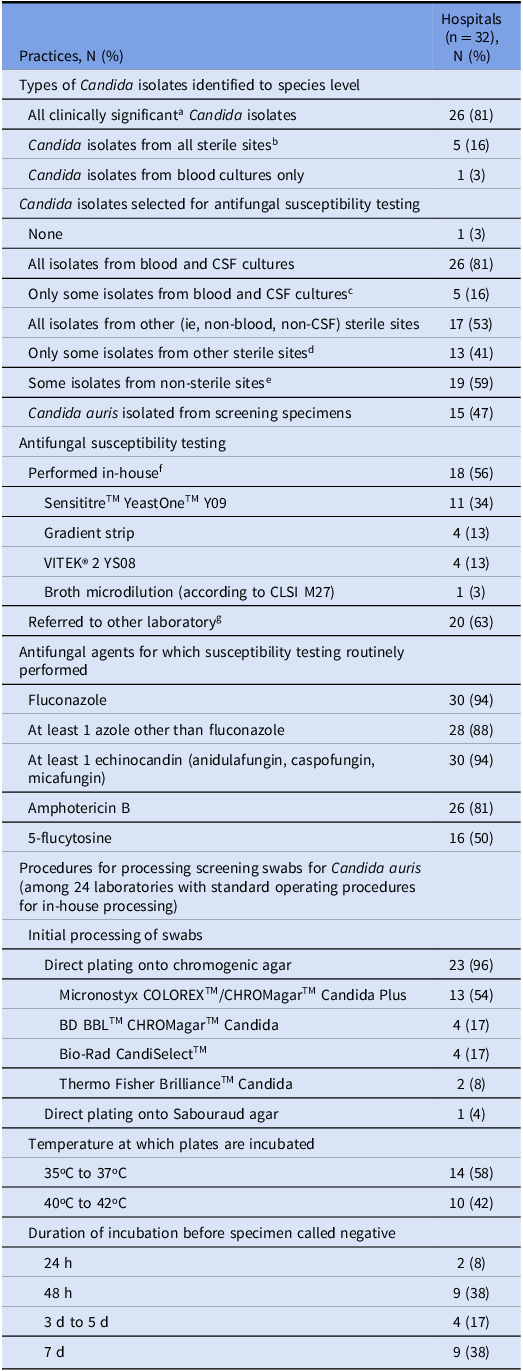

Microbiology laboratory surveys were completed by 97% (32/33) of CNISP laboratories. The results of the microbiology survey are summarized in Table 3. All clinically significant Candida isolates were identified to the species level by 81% (26/32) of laboratories; this increased from 48% to 85% (P < 0.001) in the 27 laboratories that completed both 2018 and 2024 surveys. The remaining laboratories identified isolates to the species level for at least all sterile sites (16%, 5/32) or all blood cultures (3%, 1/32).

Table 3. Laboratory practices related to Candida auris in microbiology laboratories serving Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program hospitals, 2024

a Clinically significant isolates are those for which laboratory standard operating procedures would require isolate species being reported as present.

b Of the 5 hospitals that identified Candida isolates from all sterile sites to species level, 2 also did so for isolates from some non-sterile sites: 1 on request and 1 for all C. auris isolates or on request.

c Included all non-albicans species (4), persistent candidemia/suspected treatment failure (1), all C. glabrata isolates (1), on request (1).

d Included all non-albicans species (6), on request (4), persistent infection/suspected treatment failure (2), all C. auris isolates (2), all biopsy specimens (1), prosthetic joints (1), brain (1), intraabdominal (1), depending on Candida species (1).

e Included on request (13), all C. auris isolates (2), suprapubic urine (1), ureteric stents (1), deep wounds (1), vaginal (1), vaginal with treatment failure only (1), depending on Candida species (1).

f 1 laboratory used both SensititreTM YeastOneTM Y09 and gradient strips, and 1 laboratory used both VITEK® 2 YS08 and gradient strips. Sum of laboratories is therefore greater than 18.

g 6 laboratories performed both in-house susceptibility testing and referred to other laboratories. Sum of laboratories is therefore greater than 32.

Susceptibility testing for at least some Candida isolates was performed by 97% (31/32) of laboratories, with 53% (17/32) having in-house capacity. Most laboratories (75%, 24/32) processed screening swabs in-house and had a standard operating procedure to identify C. auris colonization, while 3% (1/32) sent screening specimens to a referral laboratory. In the 27 laboratories responding to both 2018 and 2024 surveys, the number that reported having procedures to process screening specimens to detect C. auris increased from 11% to 81% (P = 0.003). Of the 24 laboratories that processed screening swabs in-house, ESwabsTM and Opti-Swabs® were the most commonly used swabs (75%, 18/24), and Liquid Amies was the most commonly used transport medium (58%, 14/24). The majority (96%, 23/24) of laboratories plated swabs directly onto chromogenic agar; one (4%) used Sabouraud agar. No laboratories used dulcitol broth enrichment or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods for detection. Plates were incubated for 24 hours to 7 days, with 54% (13/24) of laboratories requiring incubation periods of 72 hours or greater before reporting a screening specimen as negative.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that since 2018, CNISP hospitals and their microbiology laboratories have made substantial progress in preparedness for C. auris. In 2018, only 18% of hospitals had a policy for C. auris screening, and 63% did not recommend patient screening; Reference Garcia-Jeldes, Mitchell, Bharat, McGeer and Group14 by 2024, 80% reported having a policy for admission screening and 86% for post-exposure screening (with an additional 9% not having a policy but having a specific plan for post-exposure screening). Furthermore, the majority of hospitals implemented transmission-based precautions and enhanced environmental disinfection with appropriate agents for cases and exposed roommates.

In the Canadian federation, health is a provincial/territorial responsibility. To date, only three provinces have designated C. auris a reportable pathogen (one each in 2021, 2024 and 2025). 16–18 Nonetheless, provincial/territorial public health laboratories have been requesting all C. auris isolates to be submitted to them for at least the past decade. Furthermore, many laboratories refer isolates of all Candida species requiring susceptibility testing to their provincial/territorial public health laboratories, and for this project, we asked CNISP hospitals to report all patients identified as colonized/infected with C. auris, including before CNISP surveillance started in 2019. This information suggests that C. auris remains uncommon in Canada, and that the 62 cases reported since 2012 represent a majority of identified cases, although it is very likely that some colonized cases were not identified due to lack of screening.

Where data are available, most cases have occurred in persons with out-of-country healthcare exposure. Based on similar data in other jurisdictions, national guidance in the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada all recommend C. auris screening for patients who have been hospitalized in other countries. 7–9 Therefore, the 45% of Canadian hospitals that currently do not recommend screening for out-of-country hospitalization alone or have more restricted screening criteria may miss introductions of C. auris. For Canadian hospitals, this is particularly important given the dramatic increase in C. auris colonization and infection that has been observed in the United States. Reference Lyman, Forsberg, Sexton, Chow, Lockhart, Jackson and Chiller19

The purpose of the CNISP C. auris working group is to provide surveillance data for C. auris in Canadian hospitals, and to share information to support an early and effective response to this emerging pathogen, with the aim of preventing progression to endemicity. However, the variability in screening practices and duration of transmission-based precautions used for colonized/infected patients identified in our survey highlights the absence of evidence to inform policy. Although national and provincial guidance have been developed, much of this is based on expert opinion. 7–9 Building an evidence base to support transmission control programs is therefore both essential and urgent. The recent United States Department of Veterans Affairs research agenda for prevention of transmission of antimicrobial resistant organisms in hospitals highlights the evidence gaps that need to be addressed. Reference Smith, Crnich and Donskey20 One critical question is how and when to expand admission screening as the epidemiology of C. auris changes. Studies for other antimicrobial resistant organisms (such as carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales) suggest that expanding admission screening may be cost-effective even at prevalence rates well below 1%, although budgetary pressures on microbiology laboratories make expansion uniformly challenging. Reference Lapointe-Shaw, Voruganti, Kohler, Thein, Sander and McGeer21,Reference Ho, Ng, Ip and You22 Additional evidence to support decision-making about epidemiologic thresholds to increase screening for C. auris colonization are urgently needed. Other important questions include the frequency and duration of contact screening, criteria for discontinuing transmission-based precautions in exposed and colonized patients, how to balance the negative consequences of precautions and patient/family preferences against the benefits of reduced transmission, and strategies to incorporate the environmental costs of precautions into decisions about transmission prevention.

Laboratory capacity for Candida species identification and screening to detect C. auris colonization were identified as challenges in the 2018 version of this survey. Substantial gains have been made: 81% of CNISP microbiology laboratories identified all clinically significant Candida isolates to species level, and 75% process screening swabs to detect C. auris colonization in-house, compared to 48% and 11% in 2018, respectively. Reference Garcia-Jeldes, Mitchell, Bharat, McGeer and Group14 Improved identification of C. auris is primarily the result of widespread adoption of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry for organism identification, now employed by all 32 responding CNISP microbiology laboratories, as well as improvements to prior limitations in C. auris spectra in MALDI-TOF databases.

The improved ability of laboratories to process screening swabs for C. auris colonization is valuable progress. However, all laboratories used direct plating and culture (ie, no broth enrichment or PCR-based methods), and 6% incubated specimens for only 24 hours, raising the possibility that cases of C. auris may be missed. Reference Lapointe-Shaw, Voruganti, Kohler, Thein, Sander and McGeer21 The limited sensitivity of screening and prolonged incubation times required to properly process screening swabs remain significant challenges, with some guidelines now recommending PCR-based methods. 8,23 Data evaluating different laboratory approaches to detect C. auris colonization are an immediate priority. In addition, increased availability of external quality assessment programs for both culture and PCR-based methods for C. auris detection are needed to evaluate current laboratory practices for C. auris screening and to support the adoption of best practices as evidence evolves. 24,25

This survey has limitations. Although it was pilot tested, misinterpretation of questions may have occurred. The generalizability of the practices described may also be limited. Although CNISP member hospitals include approximately 37% of all hospital beds in Canada, 13,26 with representation in 11 of 13 Canadian provinces and territories, larger academic hospitals are overrepresented, comprising more than half of participating hospitals. CNISP member hospitals may also have greater existing resources and capacity for IPAC than other hospitals.

In conclusion, CNISP hospitals and their microbiology laboratories have significantly improved capacity to detect and control transmission of C. auris since 2018. However, gaps remain, and continued efforts to identify risk factors for acquisition and best practices to prevent transmission of this emergent pathogen should be prioritized. Mandatory reporting in all provinces and territories, provincial/territorial and federal collaboration in providing continuing updates and disseminating evidence related to C. auris transmission control, research funding to fill gaps in knowledge, and standardized quality assessments of laboratory processes would all help to support the goal of preventing endemicity and optimizing patient care.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2025.10228

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the essential contributions of IPAC at all CNISP hospitals, the laboratories that support them, and the staff of the CNISP secretariat and the National Microbiology Laboratory.

Financial support

This survey was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Competing interests

MKC reports receiving speaker fees from bioMérieux, Bruker, Hologic. PJD reports receiving speaker fees and/or free consumables from Roche Diagnostics, bioMérieux, Thermo/Oxoid Micronostyx and Diasorin. SMP reports receiving speaker fees and/or honoraria for advisory boards from bioMérieux, Endo, Ferring, Pfizer and Xedition. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.