Introduction

Life-threatening childhood conditions, such as a cancer diagnosis, profoundly affect the ill child and their families (Heath et al. Reference Heath, Lintuuran and Rigguto2006; Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Holm and Gurney2004; Woodgate Reference Woodgate2006). Siblings of children with cancer are particularly exposed to tremendous stress, uncertainty, and changes in family routines (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Mu and Sheng2016). Existing studies have explored the overall sibling experience, their quality of life, and their psychosocial functioning and adjustment (Long et al. Reference Long, Lehmann and Gerhardt2018). These studies have found elevated distress and unmet needs across emotional, social, and family domains (Alderfer et al. Reference Alderfer, Long and Lown2010; Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, McDonald and White2017, Reference Patterson, Medlow and McDonald2015). A systematic review found siblings experience the disintegration of life and marginalization within their family relationships (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Mu and Sheng2016). Despite these feelings and experiences, most do not confide in caregivers or medical staff during their sibling’s cancer treatment (Pariseau et al. Reference Pariseau, Chevalier, Muriel and Long2020), which can contribute to siblings’ sense of loneliness and disconnection (Tay et al. Reference Tay, Widger and Stremler2022).

One of the 15 evidence-based psychosocial standards of care in pediatric oncology (Wiener et al. Reference Wiener, Kazak and Noll2015) highlights the benefit of supporting siblings and strongly recommends availability of psychosocial support for siblings (Gerhardt et al. Reference Gerhardt, Lehmann and Long2015); yet, this standard tends to be the least implemented due to multiple interacting barriers (Brosnan et al. Reference Brosnan, Davis and Mazzenga2022; Kazak et al. Reference Kazak, Scialla, Canter, Sardi-Brown, Buff, Arasteh, Pariseau, Sandler and Wiener2025). Clinical evaluation throughout a patient’s cancer therapy does not adequately acknowledge siblings and their needs. The negative experiences of siblings often go unnoticed by the medical team unless a crisis arises (Long and Muriel et al. Reference Long and Muriel2017). The grief of bereaved siblings has been marginalized by medical systems (Weaver et al. Reference Weaver, Nasir and Lord2023).

It is accepted that children undergoing cancer treatment experience suffering – physical, psychological, social, and spiritual – and significantly at end of life (Fochtman Reference Fochtman2006; Wolfe et al. Reference Wolfe, Grier and Klar2000), which remains a primary focus within the field of palliative care. While siblings may not experience pain or physical symptoms (sensation-based suffering) like the child with cancer may, there are other forms of suffering (e.g., psychosocial, academic, relational, existential, familial, financial) that one could experience (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Kious and Largent2024). The field of palliative care has long recognized total pain concepts for the child with cancer and now may consider the concept of suffering for siblings. While their overall experience has been documented, the concept of suffering for siblings has not yet been specifically explored.

Parents are in the unique position to view the experiences of both their child with cancer and their child(ren) without cancer. Family caregiver reports of suffering in their child with cancer have been described (Wolfe et al. Reference Wolfe, Grier and Klar2000), yet their perspectives on the suffering of their child(ren) without cancer (siblings) have not. Considering the long-term impact from the experience of having a brother or sister with cancer, specific knowledge about suffering can potentially lead to supportive interventions. As a part of a larger study exploring how health care providers and caregivers define suffering of children, adolescents, and young adults (AYA) with cancer, we explored whether caregivers perceive their child(ren) without cancer to have suffered throughout the treatment course and considered differences in recounts by bereaved caregivers compared to those whose child with cancer remains living. Our aims were to determine whether parents perceive that their child(ren) without cancer suffered and, if so, to understand how through caregiver descriptions of this suffering.

Methods

The data for this publication was collected as a part of a larger study, titled VIews on the concept of Suffering – undersTAnding perspectives of children and young people, caregivers, and health professionals (VISTA Study). This study explores the perspectives of AYA oncology patients, as well as caregivers and healthcare professionals of children and AYA oncology patients on the concept of suffering and unbearable suffering. This research was exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, USA. In this manuscript, caregiver data is presented with a specific focus on their perceptions of suffering as experienced by their child(ren) without cancer which was obtained by the specific portion of survey questions that focused on sibling suffering. We report methods and findings in accordance with the COnsolidated Criteria for REporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (Supplemental Information 1).

Study design

Participants were invited to complete a short survey. This survey was available digitally, and a link was provided with all communication.

Participant inclusion criteria and recruitment

Eligible participants were parents of a child or AYA (0–39 years old) with cancer, who was undergoing treatment at the time of recruitment, had completed treatment, or had not survived treatment (bereaved parents). The present analysis was limited to parents who had one or more additional children without cancer (referred to here as “sibling(s)” or “children without cancer”).

Parents were recruited via two recruitment emails and a one-time social media posting from the American Childhood Cancer Organization (ACCO). ACCO is one of the largest grassroots organizations dedicated to childhood cancer in the United States. Agreement to participate was obtained in the introductory portion of an electronic survey instrument that was delivered via an encrypted version of SurveyMonkey. Participants completed the survey one time only. Recruitment took place from January to April 2025.

Survey

The parent/caregiver survey was developed by the research team based on literature and expert interdisciplinary input. It was pilot tested by caregivers of a child with cancer and bereaved caregivers of a child previously treated for cancer. Seven caregivers provided feedback that was included in final survey development. The survey (Supplemental Information 2) contains a total of 4–10 items, depending on the responses provided, which included multiple choice and free text questions asking respondents to describe the suffering of their child with cancer, aspects of that suffering that might be unbearable, and ways others could ease that suffering.

The survey additionally asks participants if they care for other children and if they do, whether they perceive those child(ren) to have suffered from the time the child with cancer was diagnosed. If suffering was endorsed, parents/caregivers were asked, “If you were to describe your other child(ren)’s suffering to someone close to you, what would you say?” There was unlimited space provided for free text responses. The survey took an average of 10 minutes to complete.

Data analysis

Data was analyzed using a six-step reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2024; Nowell and White et al. Reference Nowell and White2017): (1) Researchers familiarized themselves with the data by reviewing participant responses. The preliminary notes were then organized into mind maps and (2) initial codes were generated. The researchers discussed these initial codes to draw relationship between them and (3) generate initial themes. (4) The themes, sub-themes, and codes were compiled into a code dictionary (Supplemental Information 3) by PK, which was discussed with and reviewed by AKV and DC for agreement; LW was involved to find consensus when discrepancies were present. The themes were then further defined (5) and discussed among the researchers. This written report serves as the final (6) step. This was an iterative process; data was revisited at each step to allow for engagement, comparison, and reflection.

Differences in responses from parents whose child with cancer remains alive, either actively undergoing treatment or in survivorship, were compared to those parents whose child with cancer has died. Descriptive information was also presented for mothers and fathers separately.

Results

Of the 279 survey participants, 202 (72.4%; 93 mothers whose child with cancer remains alive, 28 fathers whose child with cancer remains alive, 57 bereaved mothers, and 24 bereaved fathers) had other children without cancer and were therefore included in this analysis. No opt-in rate can be calculated due to the open advertisements method of recruitment. Demographics are available in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic information of eligible parents and their child with cancer

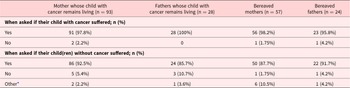

As detailed in Table 2, across participant groups – mothers versus fathers and parents of children who had survived versus died from their cancer – nearly all (198 of the 202 participating parents; 98%) felt their child with cancer suffered. Most (182 parents, 90%) additionally perceived that their child(ren) without cancer had also suffered. It is from these views that the following themes were derived.

Table 2. Parental perceptions of their children’s suffering

* Other included comments of not born yet and too young to understand.

Themes

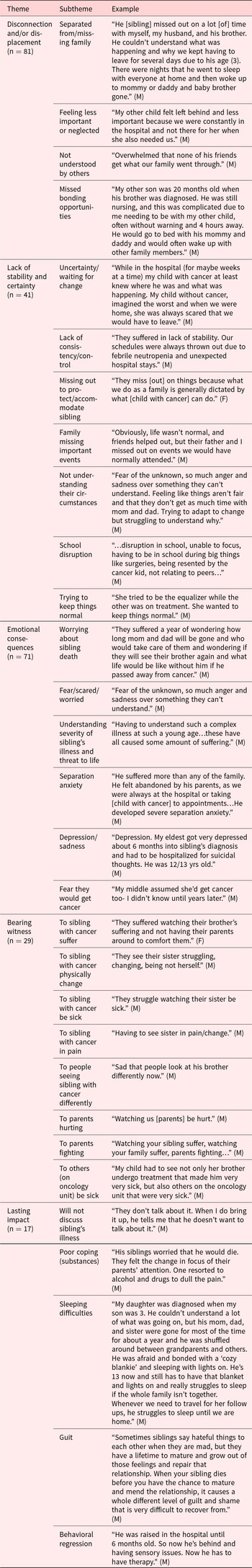

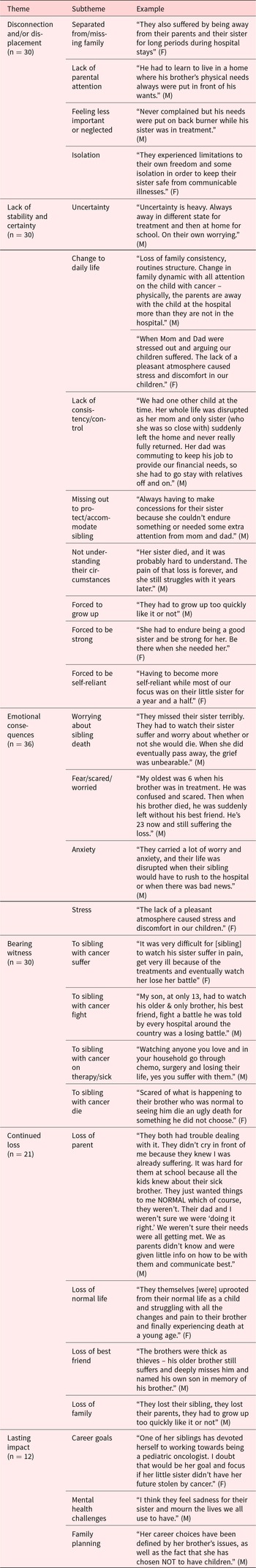

Analysis of responses from parents revealed five themes common to the suffering of both siblings of living and deceased children with cancer. These are: suffering as disconnection and/or displacement, suffering as lack of stability and certainty, suffering as emotional consequences, suffering as bearing witness, and lasting impact. One distinct theme was present from the perspectives of bereaved parents: suffering as continued loss. Each theme is described with a few exemplary quotes within the results with additional illustrations from mothers (M) and fathers (F) in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3. Themes on the suffering of siblings as perceived by caregivers of living children with cancer. Examples include (M) or (F) if quote stated by mother or father, respectively

Table 4. Themes on the suffering of siblings as perceived by bereaved caregivers. Examples include (M) or (F) if quote stated by mother or father, respectively

Suffering as disconnection and/or displacement

All parents endorsed their children without cancer suffered by missing their family during prolonged or frequent times apart. Parents described siblings feeling abandoned by being apart from their family or having to stay with others in place of their immediate family. While this separation was necessary for the care of the child with cancer, parents describe this forced separation made siblings feel left behind and disconnected from their family.

The time apart from loved ones could lead to lack of attention for siblings, which was endorsed by parents as a form of suffering. Other reported forms of suffering included feeling invisible, ignored, less important, and neglected. These feelings of less importance led to siblings withholding their feelings, worries, and experiences from their families, further disconnecting them from their support system. In efforts to allow parents to provide the necessary attention to the child with cancer, parents reported that the siblings withdrew their own need for attention.

Parents also perceived siblings suffered by feelings of isolation. Not feeling understood by others, not relating well to peers, and experiencing changes in their relationship with their sibling with cancer contributed to the feelings of disconnection. Physical separation from peers and community to accommodate the infection risks of the child with cancer as well as deeper social/emotional disconnection were described. Parents perceived siblings felt misunderstood by friends and classmates. Having withdrawn their need for attention at home, parents reported that siblings did not receive the necessary attention and understanding from their peer support either.

While even very young siblings were reported to face challenges of disconnection, some parents endorsed siblings’ younger age as a protective factor (“too young to understand/know”). Others highlighted missed bonding opportunities as a way younger siblings (and parents alike) suffered. Usual acts of connection, such as mothers breastfeeding their infant children, were disrupted.

Suffering as lack of stability and certainty

Parents of living children described the disconnection and displacement during the cancer trajectory produced periods of instability in siblings’ lives. They also shared being unable to keep home life the same due to their many new responsibilities and perceived that the siblings, remaining at home where routine had changed, felt unstable. Parents further described how changes in family dynamics, often a change in primary caretaker present at home, contributed to these feelings of instability. Bereaved parents, too, noted change in family dynamic and loss of routine and normalcy were upsetting to siblings. Difficulty in school due to altered home life further complicated the sense of stability for siblings.

In addition to changes to daily routine, parents also reported competing demands on parental attention while stressed from the sick child’s treatment. In this way, disconnection between parent and their child(ren) without cancer produced feelings of free-fall and instability. Moreover, parents’ descriptions depict a dichotomy between seeking attention (acting out) versus avoiding attention (acting perfect to avoid pulling attention from ill sibling). Siblings were unsure how to act and sought to normalize their home life as best they could.

Another form of instability described was living in a continuous state of uncertainty. Examples included being unsure when family will be home, the constant possibility of hospitalization, and the uncertainty of what is to come.

In addition to uncertainty that siblings live with, bereaved parents further highlighted an unsettling feeling of the world not making sense anymore as a form of suffering: “My 5.5- and 7-year-old don’t understand why [child with cancer], who would be 9, died from cancer. They don’t understand how we have rockets that go to space but incurable diseases that kill toddlers.” Their lived experiences made the world a place siblings could not understand.

Unique to the bereaved cohort, parents described sibling suffering as imposed early maturation which was unexpected and therefore unsettling to the sibling. Bereaved parents describe the parentification of their children without cancer throughout their sibling’s illness course. Both bereaved mothers and fathers share siblings suffered by being forced to grow up faster than typical in order to understand the complex diagnosis of their sibling with cancer and to care for themselves. Parents also report siblings being forced to be flexible, be strong, and be self-reliant.

Suffering as emotional consequences

What emerged from the data was how chronic uncertainty often manifests as fear and anxiety. Parents of living children as well as bereaved parents described anxiety, separation anxiety, depression, and sadness as aspects of suffering.

A frequent description of sibling suffering by parents was the profound fear of the death of their siblings with cancer. Siblings had to continue daily life despite the circumstances while fearing for their sibling with cancer – unsure and fearful whether their sibling with cancer would survive and come home again.

While siblings feared the death of the child with cancer, they also feared what life would be like if their sibling with cancer did die. Parents also described siblings’ fear that they themselves would get cancer and undergo the same experiences as their sibling with cancer. Bereaved parents further described a constant state of fear or worry, sadness, and anxiety in siblings that persist long after the death of their child with cancer.

Suffering as bearing witness

Parents described the unique process of siblings as witnesses to the suffering their sibling with cancer was enduring and specifically highlighted this as a form of sibling suffering. Siblings not only feared the process of their sibling with cancer being sick, but they also “had to watch.” Both bereaved parents and those whose child with cancer survived shared they felt siblings suffered by watching the child with cancer be sick, stuck with needles, physically change, and be in pain. Parents noted suffering to also include watching parents hurting, fighting, and stressed. One mother shared how her child without cancer suffered seeing other children on the oncology unit being very sick. Bereaved parents added suffering as witnessing the sibling fight, decline, and ultimately die.

Lasting impact

Parents reported the importance of noting the long-term suffering that siblings experience. Behavioral regression, developmental delays, separation anxiety, depression, poor coping skills with use of illicit substances, and suicidal ideation were described. Both mothers and fathers of living children described their children without cancer still being unwilling and unable to discuss the topic of their ill sibling’s health. Several parents reported that they were unaware siblings continued to struggle with feelings of anxiety and depression regarding the cancer experience until years later.

While this study focused on perceived suffering, both mothers and fathers described long term positive and negative effects, including siblings’ career goals being impacted positively by the cancer experience, specifically by ultimate pursuit of work in the field of pediatric oncology. A bereaved mother shared that her child without cancer had chosen not to have children of her own after witnessing the suffering of her sibling with cancer.

One additional theme emerged in the bereaved group

Suffering as continued loss

Unique to the bereaved group, parents describe suffering as loss – loss of a normal life and what was once known. This loss is also described in missing parents and their sibling with cancer during challenging treatment courses, and ultimately in the death of their sibling with cancer and loss of their best friend.

In the aftermath of the death of the child with cancer, parents described the ways in which surviving siblings experienced a persistent loss of their parents, and therefore their support, as parents were emotionally unavailable while managing their own personal grief. Following the death of a sibling, parents noted surviving siblings suffered from grief, guilt, and uncertainty about whether it was acceptable for them to move forward and be happy again.

Discussion

This study is the first known to specifically investigate and describe suffering in siblings of a child with cancer as perceived by their parents. This study is relevant to palliative clinicians in caring for children not only as individual patients but also as members of a family unit. Sibling suffering during the cancer trajectory include disruption of normal life, disconnection to loved ones and peer support, lack of stability in daily life, and lack of certainty over the projected short- and long-term course of their life and that of their sibling with cancer. As a result, siblings often experience profound emotional consequences, including fear and deep sadness. Parents described how bearing witness to illness, pain, loss of functioning, and sometimes death results in sibling suffering, that for many persists for years or life.

One hundred ninety-eight of the total 202 participating parents (98%) felt their child with cancer suffered, and, strikingly, 182 of these (90%) felt their children without cancer suffered as well. For parents to acknowledge both vastly different experiences as suffering is profound and further highlights how the sibling experience should not be overlooked.

Many of the sibling experiences described herein have been previously identified, both from the parent and sibling perspective, including disruption in family routine; changes in family environment; lack of parental attention; feeling overlooked and neglected; a sense of loss; fear and frustration; feelings of anxiety, anger, and isolation; and fear of death (Alderfer et al. Reference Alderfer, Long and Lown2010; Tay et al. Reference Tay, Widger and Stremler2022; Woodgate Reference Woodgate2006; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Mu and Sheng2016). We found that these challenging circumstances represent experiences of suffering and should be addressed and supported as such.

New in this report is the description of bearing witness, identified frequently by parents as a form of sibling suffering. While parents, too, bear witness to the struggles of their child with cancer, they are intimately intertwined in the child’s care in a channel for their attention and energy. Siblings are bystanders to the experiences of their sibling with cancer – not necessarily as privy to the details as parents yet unable to detach as a friend, neighbor, or classmate may. This act of bearing witness shapes the sibling experience. Previous work by Pariseau and colleagues recommended consistent inclusion of siblings into the care of the child with cancer to help provide medical clarity and mitigate unnecessary concerns (Pariseau and Davis et al. Reference Pariseau and Davis2025). A reported barrier to this had been parental concern for increasing sibling distress and worry (Pariseau and Davis et al. Reference Pariseau and Davis2025). The perceptions gleaned through our study show siblings are witnessing the experiences of their sibling with cancer – the changes, the symptoms, the suffering – regardless of parental well-meaning attempts to shield their other children from the suffering of their child with cancer. This act of witnessing – “seeing,” “watching” – should be noted and considered in the assessment and care of siblings.

Despite perhaps being labeled as the “well child,” siblings of children with cancer endure transitions that ultimately can affect them and could even cause them to become unwell in some ways. It is in the understanding of this sibling suffering that we can appreciate a specific concept of suffering – flourishing-based suffering (Kious Reference Kious2022). Flourishing-based suffering, as opposed to sensation-based suffering (e.g., pain, disagreeable feeling) is when a person suffers if they fail to achieve their own flourishing. (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Kious and Largent2024; Tate Reference Tate2020a; Reference Tate2020b). In this way, a person may suffer in being unable to fulfill their expected potential. While it is possible for one to suffer and still flourish, the flourishing-based suffering concept is one lens through which to appreciate sibling suffering.

Parents shared siblings endure disruption to most aspects of their daily life. A change in one’s life course may suggest one’s previous flourishing capacity has been altered. The time, travel, extended hospitalizations, frequent appointments, emotional investment, and attention necessary for pediatric cancer care may risk the function and flourishing of the sibling. In descriptions of the lasting impacts on siblings, parents describe behavioral and academic regression, developmental delays, poor coping skills with use of illicit substances, separation anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. These are all ways parents have perceived siblings’ flourishing to be stunted. Our survey specifically only inquired about suffering experiences ithout focus on the resilience of siblings, which is well highlighted in sibling literature.

Clinical implications

Overall, the experience of sibling suffering, so powerfully illustrated by parents, highlights the need for recognition within the palliative care community. Palliative teams should consider sibling support and sibling validation a part of comprehensive pediatric care. While every individual experience should inform the provided supportive care, this data suggests a foundation for shared supports across both sibling populations (bereaved siblings and those whose sibling with cancer remains alive) is a place to start.

Reports of sibling post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), persistent mental and emotional stress due to the witnessing of a distressing event, is unsurprising given our participants’ accounts of the suffering to which these children bear witness. Previous studies have reported 29–60% of siblings experience moderate to severe PTSS (Alderfer et al. Reference Alderfer, Long and Lown2010; Kaplan et al. Reference Kaplan, Kaal and Bradley2013) with a more recent study showing 32–41% of siblings experienced PTSS within 6–24 months of diagnosis, depending on time of assessment (Alderfer et al. Reference Alderfer, Amaro and Kripalani2023). Identifying siblings with elevated PTSS and providing them with the necessary care is vital to the immediate and long-term impact on their psychological wellbeing. Helpful resources for providers to acknowledge and respond to the experience of suffering identified in this study include the Sibling Module of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Alderfer and Pariseau2023; Long et al. Reference Long, Davis and Pariseau2022) and the Sibling Blueprint (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Mazzenga, Hall, Buchbinder, Alderfer, Oberoi, Sharkey, Blakey and Long2024; https://childfam.wixsite.com/siblingblueprint, last accessed July 2, 2025).

The parental reports included here emphasize how parental witness of a child’s symptom burden impacts parental wellbeing. The “Good Parent” model explored the definition of a good parent to a seriously ill child (Weaver et al. Reference Weaver, October and Feudtner2020). In this model, being a good parent as defined by parents of seriously ill children includes remaining at their child’s side, providing basic needs and positivity, advocating for their ill child, and making certain their child knows they are loved by their parent. Responses to our survey suggests that to provide this for their ill child, parents perceived that they compromised providing similar care and support to their child(ren) without cancer. This begs the question: how can a parent be a good parent for their sick child and for the rest of their family?

The experiences of siblings, as perceived by their parents, rest heavily on the role and action of parents. For example, parents felt siblings suffered by being separated from their parents, lacking attention from their parents, and feeling unsupported by their parents. Though these responses are likely influenced by the parenting lens of our participant population, it does highlight the role of the parent as essential to both the care of their child with cancer as well as the siblings. While sibling support is essential, better support of parents may optimize parent, child, and family wellbeing.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study merit mention. First, acknowledging the suffering of one’s living or deceased child may be emotionally very challenging, and, as a result, it is likely that only those with the emotional capacity to answer our questions regarding their child’s suffering participated.

Second, while we had a robust response to the survey invitation via ACCO, this might have limited perspectives from parents engaged in another caregiver advocacy group. Our participant population was primarily White and Non-Hispanic and participants were required to read and respond in English to complete our survey.

Third, most research into the experience of siblings relies on caregivers’ rather than siblings’ perspectives (Houtzager et al. Reference Houtzager, Grootenhuis and Caron2005). Here, too, we rely on parent perception of the sibling experience. Our study did not include surveying siblings directly, though this is an avenue for a future study. In efforts to minimize survey burden and maximize anonymity, our survey did not inquire about age of siblings nor the age difference between child with cancer and siblings. Sibling understanding, due to age and development, likely contributes to their perceived and experienced suffering.

Finally, we are not sure our data was able to fully delineate causes of suffering versus manifestations of suffering. For example: is the uncertainty these siblings live with itself suffering or does the presence of uncertainty manifest to other forms of suffering? Does suffering change over time and are there specific timepoints when siblings suffer the most? Our data cannot answer how the perception of suffering may have altered the relationship between parents and their children without cancer. Changes in this relationship both during and after sibling’s cancer-directed therapy is worthy of further exploration.

Conclusion

Siblings of children with cancer face unique difficulties along the cancer trajectory. Many may flourish due to or despite their circumstances; yet others may not. Either at certain time points or longitudinally over the illness course, siblings may endure suffering. In the view of their parents, this suffering may take the form of disconnection, displacement, lack of stability and certainty, bearing witness, and continued loss. Recognizing the suffering of this often-bypassed group is the first step to developing preventative and palliative interventions to enhance coping and reduce the potential short- and long-term negative sequelae in this population.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951525100825.

Acknowledgments

Our deepest gratitude to all the parent participants who took the time to share their and their children’s experiences. We are tremendously grateful to Ruth Hoffman, Executive Director of the National Office of the American Childhood Cancer Organization, for her support of this study and dissemination through the American Childhood Cancer Organization that allowed us to capture these valuable insights.

Funding

This research study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA. Ursula Sansom-Daly is supported by an Early Career Fellowship from the Cancer Institute of New South Wales (ID: 2020/ECF1163). Anna Katharina Vokinger was supported by an UniLu Doc.Mobility Grant from the Graduate Academy, University of Lucerne, Switzerland. Devon Ciampa is supported by Teen Cancer America, Inc.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Institutional Review Board statement

This research was exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, USA.