Introduction

Scholars of the history of science, especially chemistry, will be familiar with the phenomenon illustrated in this Element.Footnote 1 I refer here to what they often called the “Geber problem.”Footnote 2 As part of the grand narrative of the history of science(s), it is well known that Greek sciences were adopted by Arab scientists, who allowed their penetration into the so-called Latin West through Latin authors who translated these scientific works. This chain of transmission is part and parcel of the historiography of science, and while it is undoubtedly a fair description of how Greek and Arabic sciences were transmitted and traveled, it should not stand as an uncontested paradigm when it comes to the examination of certain specific works. The “Geber problem” can be seen as revolving around this specific issue. It expresses the apparent tension between the grand narrative of the scientific works’ mode of transmission and the facts that can be extracted from the actual texts.

Geber is the Latin name for Jābir (hence, Geber) ibn Ḥayyān, who is known from several works as an alchemist who was presumably active during the eighth century in Baghdad.Footnote 3 When Geber’s texts appeared in the Latin West, they were regarded by their readers as translations of Jābir’s alchemical works. They were also considered as such by nineteenth-century scholars, who were familiar with the figure of Jābir and his works. Holding the grand narrative of the Greek–Arabic–Latin direction of transmission, it was only reasonable for them to ascribe to Jābir the authorship of Geber’s works, arguing that the Geberian corpus is, indeed, a body of translated texts from Arabic into Latin. The fact that the assumed original works, which were supposed to represent Geber’s sources, could not be found was attributed to their loss or a yet-to-be-discovered piece of history. All these views were later revised, based on a close reading of the Geberian texts. Today, there is almost a consensus about Geber: not Jābir, and not even an Arab, but an Italian Franciscan friar, who promoted his work by ascribing it to Geber, that is, Jābir, whose status as the historical figure behind Arabic sources that have survived has been contested since then. It is commonly accepted that those sources represent not a single author but a group of Shiʿi (sometimes more specifically Ismāʻīlī) scholars who were active during the eighth and ninth centuries.Footnote 4 The works of Geber were not translations of Arabic texts but rather original pieces by the Italian friar, whose name might also be a pseudonym – Paul of Taranto, presumably a lecturer in Assisi.Footnote 5

The “Geber problem” is much more than an interesting anecdote in the historiography of science. It is a thought-provoking and tantalizing case that calls for our caution and hesitation when describing the texts we are working on. Why and how do we assume that the text in front of us originated in a different cultural or linguistic context? What kind of evidence do we possess that supports our thesis? What is the impact of grand narratives on our philological sense? To what extent can we trust our medieval authors, not in terms of falsehood but in their perception of authority and attribution? These are only some of the questions that the Geber problem poses to historians seeking to understand the development of knowledge within its historical, social, and cultural context. This Element calls for reflection on these questions when interpreting magical texts to better situate them in the history of knowledge transmission.

Earlier generations of scholarship, shaped by Orientalist assumptions, sometimes attributed works to “the Arabs” or posited a lost Arabic source. Consider, for example, the following citation of the late great scholar of Jewish studies Gershom Scholem:

Nothing in the content of these traditions prevents us from asserting that their origin is in the East … The imagination of the Arabs concerning demons was rich, as is well known, while this is not the case for the imagination of the people of the West in the Middle Ages. These demonological methods, with all their fantasies, result from the winds that blow in the air in which their creators lived; [that is,] in the Eastern air.Footnote 6

Contrary to his assumption, Scholem, writing in the mid twentieth century, lacked a firm basis for positing an “Eastern” origin. The traditions he refers to – attested in anonymous sources used by the medieval thinker Isaac HaKohen – show no signs of a translation process, nor is there any comparable source to suggest such a lineage.Footnote 7 “It is very difficult to perceive them as formatted in the West,” noted Scholem concerning the demonological materials, without giving any textual evidence to support his claim, nor citing a related “Eastern” (let alone Arabic) work that might have served as the basis for his argument. Writing about the imagination of the Arabs, as opposed to the (“rationalistic”) imagination of the West, Scholem proposed no less imagined connections between the materials that circulated in the West and Arabic demonology – a field with which he was familiar and about which he wrote in other publications.Footnote 8

Even setting aside the lack of textual evidence, Scholem’s reasoning reflects an early twentieth-century Orientalist perspective, locating imaginative power in the “East” and explanatory deficiency in the “West.”Footnote 9 In certain strands of Jewish studies scholarship, such assertions led to a sharp emphasis on Arabic elements, primarily onomastics, as markers of an Arabic textual source. Latin counterparts, on the other hand, have not received such treatment. When Scholem read a magical work with Latin terms, he did not necessarily assume a Latin source behind it and sometimes completely ignored it. That is the case with a late thirteenth-century or early fourteenth-century Hebrew work circulated under the title Berit Menuḥa (The Covenant of Serenity). Berit Menuḥa is a treatise on divine cosmology and angelology which also contains detailed magical recipes for finding water in the desert, triumphing in war, healing, bringing about an enemy’s downfall, and other purposes. In some parts of the work, the names of famous demonic kings – known already from Arabic sources – are listed, after being explicitly described as originating from Arabic sources: “And in Arabic they are called ʾLMWDHB the ruler of Sunday, ʾLḤʾRT – and this is ʾBW MWRʾ – the ruler of Monday, ʾLʾḤMR the ruler of Tuesday, BRQʾN the ruler of Wednesday, ŠMHWRYŠ the ruler of Thursday, ʾLʾBYṢ the ruler of Friday, MYMWN ʾLSḤʾBY the ruler of Saturday, [and] MYMWN son of NḤ rules them all.”Footnote 10

While Scholem commented on such appearances of Arabic materials in the text,Footnote 11 he completely ignored the preceding words in this list: “Enhance the power of these eight kings who are named Kheshalshun Ḥadlimon Qantefit Tarfit Shadrakh Meishakh ‘Avidinno ’Alfa’eiro.” Without attempting to clarify all the figures named here, one can readily identify the three children from Daniel 1:7 – frequently mentioned in Latin adjurations – by their Aramaic names: Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego.Footnote 12 The last name is also noteworthy as it appears to derive from the Christian phrase “Alpha et O[mega],” which is likewise common in Latin magical sources.Footnote 13 In this instance, the working assumption of an Arabic provenance may have diverted attention from the equally significant Latin and Christian resonances, narrowing the analytical lens applied to the text’s composite character.

A residual form of this narrow lens, I argue, can still be detected in a few modern scholarly works. For example, a recent critical edition of Berit Menuḥa, working closely with Scholem’s notes, again invokes the Arabic strata, situating the treatise within broader “Eastern” currents and, via phenomenological rather than philological comparison, juxtaposes certain notions with those of Kashmiri Śaivism.Footnote 14 However, all these formulas point to an author who combined various materials into his own system of magic, explicitly equating the Latin names (whether or not he understood them – this remains open to debate) with Arabic ones. This reflects a multicultural environment rather than a specific lost Arabic or Latin urtext.

Scholem’s case is an extreme example, and it does not accurately reflect contemporary scholarship.Footnote 15 Yet, in studying the history of magic, we sometimes seek out the foreign to pinpoint a (textual) source. The remote origin is sometimes assumed to lie elsewhere, in another language and cultural framework. When it erupts into the text – often in the form of untranslated short formulas or nomina magica – we take this as evidence that another original layer, obscured by processes of cultural translation, has now been revealed, resisting efforts to render it into a different linguistic or cultural context. Yet the assumption that scribes were skilled enough to translate most of a text but somehow unable to handle parts of it is more often asserted than demonstrated. When Scholem encountered a Hebrew magical work that included a paragraph in Judeo-Arabic, he concluded that this confirmed the work’s Arabic origin.Footnote 16 But, if this is indeed the case, is it not strange that the scribe could translate some sections but not others that pose no apparent difficulty? In the case in question, it is more plausible that the author inserted the paragraph from another source, rather than being unable – or, as Scholem suggested, simply unwilling – to translate it.Footnote 17 In any case, it may be more productive to refrain from assuming our authors’ inability to work with a language they otherwise seem able to translate.

Borrowed from classical Lachmannism, close reading of an unexpected passage is sometimes treated as a chance to “catch the thief red-handed” and to sketch a stemma codicum. But a sudden “foreign” intrusion is not, by itself, proof of a lost foreign urtext or prototype. More often, it registers an encounter between our expectations and what the manuscript actually transmits. As scholars of magic acknowledge, a Hebrew formula inside a Latin treatise, for instance, need not point to an entire Hebrew original; it simply documents contact – direct or indirect, real or imagined – between Hebrew and Latin textual worlds. Such an encounter may be direct (e.g., an exchange of knowledge between experts, textually and orally) or indirect (e.g., a later borrowing resulting from such an exchange), actual or imagined.Footnote 18 Such cross-pollination is typical of learned magic, yielding a richly layered record of transmission and transformation.Footnote 19 Consider, for example, the transliterated (Hebrew to Latin) Jewish prayer Shema Yisrael, which appears in several magical works written in Latin. Such formulas are striking evidence of intercultural encounters but do not support the idea of a Hebrew urtext. Likewise, the modern Arabic Sifr Ādam reveals an equally complex trail of borrowings and adaptations.Footnote 20

The nuance of such a detailed and complex textual transmission, which modern scholarship broadly accepts, can be blurred when we rely on umbrella labels. As modern studies recognize, the use of broad categories such as “Jewish magic” does not convey the idea of a Jewish urtext, but rather a very concrete and specific case in which a Jewish scribe engaged with a magical text, whatever this text might include.Footnote 21 For that reason, the label “Jewish magic” is best reserved for these cases. Applying the same tag to compilations produced by non-Jewish scribes may inadvertently suggest that the work is inherently “Jewish” or that a Jewish intermediary must lie behind it. The same caution applies to the companion label “Arabic magic.” When a text is written in Arabic or demonstrably compiled by an Arabic-speaking author, the descriptor is perfectly transparent: It signals the language of composition and the compiler’s milieu, without implying a pristine original. But what exactly are we saying when labeling a Latin text as a work of “Arabic magic”? In what follows, I will use the term “multicultural magic” to refer to compilations that display precisely these layered encounters – texts in which Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, Greek, and other traditions intersect. This term makes it explicit that a foreign element signals contact, not necessarily a hidden, homogeneous urtext.

When considering that a text may have a lost Arabic origin, another aspect should be taken into account. In his famous and forceful critique of what he called “the classical narrative” in the historiography of science, George Saliba has shown how specific details challenge this narrative – namely, the view that the Arabs were merely recipients of Greek science, functioning as passive vessels without original contributions.Footnote 22 They were also portrayed as mere transmitters who, in the eyes of European Renaissance scholars, were sometimes considered defective and whose works were to be discarded.Footnote 23 Of course, these assumptions are no longer accepted today, and the attitudes of authors and practitioners of magic toward Arabic science (and magic) are taken into account when examining the works that serve as our research sources. Their perception of what they considered “Arabic” is crucial for our study, as we will see later.

It may surprise the reader that this study does not attempt to define, examine, or contribute directly to the field of “Arabic magic.” This field has grown considerably over the past decade, enriched by exceptional research grounded in close textual analysis. Recent studies by scholars such as Charles Burnett, Jean-Charles Coulon, Noah Gardiner, Matthew Melvin-Koushki, Liana Saif, Emilie Savage‐Smith, Emily Selove, and others have immensely contributed to our understanding of Arabic (Islamic and non-Islamic) magic, as well as the reception of Arabic magic in non-Arabic cultures and “the Latin West.”Footnote 24 While this Element will be based on this scholarship, we will not discuss the Arabic texts per se in what follows.Footnote 25 Instead, this study will center on what we might call “the imagined Arab magician” and how this notion may have shaped our understanding and historiography of certain magical (or scientific) works. Specifically, we will begin by examining how a fourteenth-century Christian magician viewed the Arabic language and Muslim practitioners. In doing so, we will ask whether the magician’s efforts to link certain magical practices to Arabs reflect genuine transmission – that is, his having actually learned them from Arab practitioners – or whether these are more a product of his own invention.

After exploring the role of the “imagined Arab magician” – the “magical Geber” – we will turn to a Latin work attributed to an Arabic figure, which scholars have regarded as a text of Arabic origin: The Seven Names. Interestingly, one of the first modern scholars to discuss this work, the late David Pingree – an eminent historian of science – was already well aware of the “Geber problem.”Footnote 26 A closer reading suggests that a lost Arabic original is not necessary to explain the text’s features, and presuming one may obscure its complex development, authorship, and context. More critically, it narrows the search for parallels to one cultural zone, when, as in the Geber case, relevant evidence may lie elsewhere.

In the past, a few influential mid twentieth-century scholars sometimes viewed such texts as products of a single “pure” tradition (for example, by positing an entirely Arabic provenance).Footnote 27 When applied uncritically, such an approach can overlook the reality that many medieval works were the result of ongoing intercultural and interreligious exchanges. In the case of The Seven Names, assuming an Arabic prototype quickly led to a second assumption: that the prototype entered Latin literature through a specific wave of translations. I do not contest that translation trend, but I suggest that combining these two suppositions risks creating an overly linear story.

We will conclude this Element with an especially challenging case: whether one can or should posit an Arabic origin for a text when the Latin sources clearly preserve traces of Arabic words. Rather than proposing a definitive answer, I offer a different approach. Instead of asking whether the Latin text is based on an original Arabic work, we should consider why Latin authors found an Arabic text suitable for their purposes, the historical context in which such adaptations might have occurred, and the sources available to these authors. This is not an effort to reassert an Arabic origin or resurrect the “imagined Arab magician” and his equally imagined works, but rather to highlight the breadth of intellectual activity generated through direct and indirect intercultural exchanges. Accordingly, this third section will propose another hypothesis regarding the history of the text.

Writing about these cases is difficult. Reexamining the assumptions regarding Arabic sources is no simple task, as it is deeply entangled with Orientalist perspectives and tendencies toward cultural appropriation. At the same time, such a revisiting can be interpreted as minimizing the significance of Arabic texts in shaping European learned magic – an impression I do not intend to convey. Nevertheless, caution is needed when using reductive categories to depict the transmission processes, avoiding overly broad strokes in works that merit more nuanced attention. The following discussion illustrates how sweeping generalizations can sometimes hinder our ability to recognize the more complex – and less stable – histories underlying texts that are sometimes described in terms that may imply, even unwillingly, a single, uniform (or monochromatic) framework. Such histories are inherent to multicultural magic.

1 The Wise Saracens: Berengar Ganell and His View on Islam

Berengar Ganell, a fourteenth-century Christian magician from Catalonia, is an important figure in the history of learned magic. This author, who collected and compiled materials from various sources to create his magnum opus, the Summa Sacre Magice, composed his work without being anonymous, demonstrating historical awareness, raising questions about the contradictions in the texts, and exhibiting transparency – albeit sometimes illusory – about the strategies of collection and compilation he employed.Footnote 28 We also know about his activities as a magician and advisor to other practitioners through legal documents in which he is mentioned, as well as his interactions with anonymous experts presented in his work.Footnote 29

Ganell completed the Summa Sacre Magice in 1346, following his stay in Perpignan, where he collected translations of works from Hebrew and Arabic into Latin.Footnote 30 The “sacred magic” he developed consciously and explicitly relied on the four languages that dominated the scientific discourse of the time – Latin, Greek, Arabic, and Hebrew – and he even compared his magical system to philosophy. Just as the sciences and the grammar of the philosophers rest on these four languages, he argued, so does magic rely on the same four languages.Footnote 31 Considering the fact that Ganell held a specific notion about the chronology of world religions – paganism came first, then Judaism, Christianity, and finally Islam – his comparison of his magic to philosophy draws on that same sense of historical awareness, enabling him to cast himself as a contemporary philosopher.Footnote 32 Situating himself in respect to others was important to Ganell, who often did so explicitly. He consistently compared “sects” (what we would call today “religions,” broadly speaking) in terms of their sources of power, authority, ability to work through the sacred magic, and the potential efficacy of their magic. In these points, we can learn about Ganell’s treatment of foreign sources and his complex approach toward non-Christian practitioners of magic.

While Ganell used Latin sources that, in turn, are based on Hebrew and Arabic works – and by that, I should also specifically state Jewish and Islamic – he had ambivalent sentiments toward non-Christian practitioners. In an attempt to situate himself and his “sect,” that is, Catholicism, in world history, he raised questions regarding the antiquity of his own materials, yet was still well aware of the multicultural nature of his sacred magic:

Also, know that this art, as mentioned above, is founded on four sects. However, since during Solomon’s time there was no Christian or Mohammedan sect, it seems impossible for it to have been founded on four sects at that time. On the other hand, this seems necessary because Solomon himself placed on his sacred table, which he worked with, the four alphabets of the four sects, as is evident to those who observe it. Therefore, there remains a great doubt.Footnote 33

Ganell is worried. King Solomon, to whom Ganell attributes many of his sources, lived in a world where no Christian or Islamic practitioners could be found. How, then, can this Solomonic magical art be so multicultural? How could Solomon use the alphabets of the Christian and Mohammedan – that is, the Latin and Arabic alphabets – in a pre-Christian and pre-Islamic world? The tension felt by Ganell here is clear, and he allowed himself to describe this as a “great doubt,” a phrase full of hesitation. He later offered a possible solution, which – in the presence of this magnum dubium – did not seem to convince him either: The alphabets existed even before the religions associated with them.

Constructing his spells, Ganell used the sources available to him. Thus, he found the Arabic names of the lunar mansions appropriate for certain spells, interweaving them with angelic names he found in other sources. Consider, for example, this part of a long conjuration:

Also, I conjure, adjure, and compel you, N., to come, appear, and render according to the names of the 28 mansions of the moon: Alnath, Albuthah … And by the angels dwelling therein, with those 7 front liners [acierum], whom I call to my aid by the power of your name, God Eyeassereye, whom I name by their letters: Horpenyel, Tyggara, Danael, Kalamya, Acymor, Paschar, Boel.Footnote 34

In a single spell, we can see the use of the Arabic lunar mansions (Alnath and Albuthah being the first ones, النطح and البطين) and the seven Hebrew angelic figures that were known to Ganell through Liber Razielis, the Book of Raziel.Footnote 35 The Arabic lunar mansions have long been available in Latin sources, and Ganell needed them to complete his system of magic.Footnote 36 Thus, he did not ignore the Arabic sources that he, in fact, could not access without the Latin mediator. It was important to him to mention that the sacred magic is based on languages and sources, even though he could not read them. He knew no Arabic or Hebrew, except for some basics: the direction of writing/reading (that is, from right to left), the alphabet, and a few words, some of which do not necessitate any serious Arabic proficiency whatsoever (e.g., Allah). While he could not read the Arabic and Hebrew sources directly and felt “a great doubt” when he compared his theory of the development of this multicultural magic with his view on world history, he still insisted on incorporating them.

Let us make this case even more complicated: Ganell did not appreciate Jewish or Muslim practitioners, to whom he ascribed some of his sources. In his Summa, he attacks Jewish practitioners, whom he accused of acting against God’s will and practicing nigromancy, as opposed to the Christian practitioners who practiced the perfect sacred magic.Footnote 37 While he does not explicitly mention here Jewish practitioners, he refers to them as those who ask God or His name things, as “this art presupposes that God is in His name, and His name is in Him.”Footnote 38 The presupposition that Ganell refers to is actually a translation of a Hebrew phrase with which he was familiar through a Latin translation.Footnote 39

Both Muslims and Jews, according to Ganell, hold false beliefs, which makes their magic less effective.Footnote 40 When describing world religions, he criticizes both Jews (for not believing in the Trinity) and Muslims (for following Muḥammad):

And of these religions, the first was paganism, which worshipped the planets and called them gods … The second was the Hebrew [religion]. And these [Hebrews] believe in one true God, but not that He is triune. The third is Christianity, which confesses the Trinity and the unity. The fourth is the Mohammedan [religion], which, despite believing in God, still believes the scoundrel (ribaldum) Muḥammad to be a prophet of God.Footnote 41

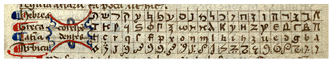

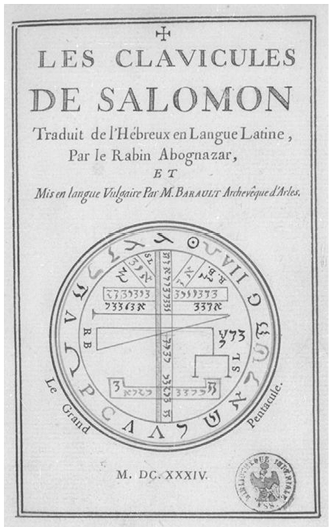

None of these harsh words brought Ganell to the conclusion that Hebrew and Arabic sources – which he identified as Jewish and Islamic, respectively – are useless or fraudulent. As practitioners, their magic is less effective. But they are great as transmitters of knowledge, which goes back to (at least) King Solomon. Furthermore, the Hebrew and Arabic alphabets played an important role in Ganell’s system of magic, as noted, and the equation between them is made explicitly in the Summa. One only needs to observe his alphabetic tables to see how Ganell perceived them as comparable (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Alphabets correspondences (Kassel, Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel, 4° MS. astron. 3, 131v).

While Ganell did not appreciate the beliefs of the Jews or the Muslims, he did not treat their magic at the same level. I suggest that his comparison of the sacred magic to “the grammar of the philosophers” is highly revealing in that context: Ganell wanted his sacred magic to be seen as transmitted through the same channels. We have already seen his historical awareness and how he situated his magic within a religious framework, while also considering world history. It should not surprise us that he was also aware of the transmission of scientific knowledge by Christian scientists (that is, philosophers), some of whose works he evidently used. For example, he drew from Ptolemy’s Quadripartitum to explain some basic astronomical concepts for those who could not access institutional education: “Therefore, you should at least learn the principles of astrology when you want to involve yourself with magic. But if you do not find a school of astrology, at least know these few rudiments that I will tell you.”Footnote 42 He then describes the cosmos with its immovable (empyrean and crystalline) and movable heavens and offers explanations on several topics, including, for example, the various houses and their characteristics, the astrological faces, and the exaltations of the planets. Interestingly, the most popular Latin translation of the Ptolemaic work was made in the same court in which other works possessed by Ganell were made – Alfonso X’s court.Footnote 43 That is to say, Ganell was well aware of the philosophers who granted him access to the knowledge he deemed part of his system of magic, and he had the clear motivation to make his magic appear as (at least partially) their product.

With this in mind, let us examine an interesting case that appears in the fifth book of his Summa, in which he copied – but also reworked extensively – a series of recipes from different sources, under the fifth chapter that he entitled “On the art of enchanting and disenchanting” (De Arte incantandi et disincantandi).Footnote 44 Ganell presents several recipes there, sometimes explicitly referring to the sources, even in cases where he reworked them. For example, he referred to Liber Saturni (the book of Saturn) as the source of some recipes for creating astrological images. Liber Saturni is a treatise that was famous during the Middle Ages and early modern period, circulating with other treatises that together were known as Liber septem planetarum ex scientia Abel.Footnote 45 The following recipes in the list, although formulated similarly to those of the Liber Saturni, are not from this work. Like the recipes of the Liber Saturni, they also require the magician to prepare an image at a precise and detailed astrological time. However, on this image, we can find names that are not found in Liber Saturni, such as the “seal of the air” that needs to be engraved on the back of the image. This seal is essentially a formula that originated from another work held by Ganell – Liber Iuratus Honorii (The Sworn Book of Honorius). It also had an important role in Ganell’s Summa and subsequently found expression in the astro-magical practices that Ganell developed.Footnote 46

The last recipe in this part is most interesting for us since it reveals how Ganell ascribes texts to different authors or practitioners. This recipe, as mentioned, is part of a series of recipes that mainly discuss astrological images, with some explicit references. However, this method is different, based not on Liber Saturni or other known manuals on astrological images. According to Ganell, this is a method for enchanting everything (ad omnia incantanda):

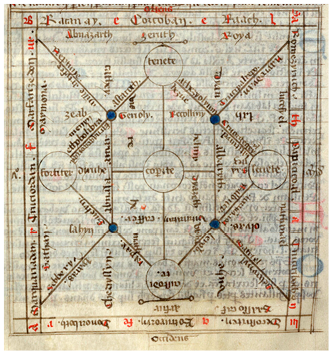

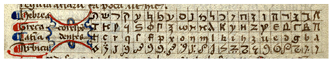

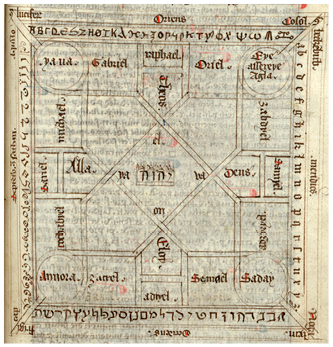

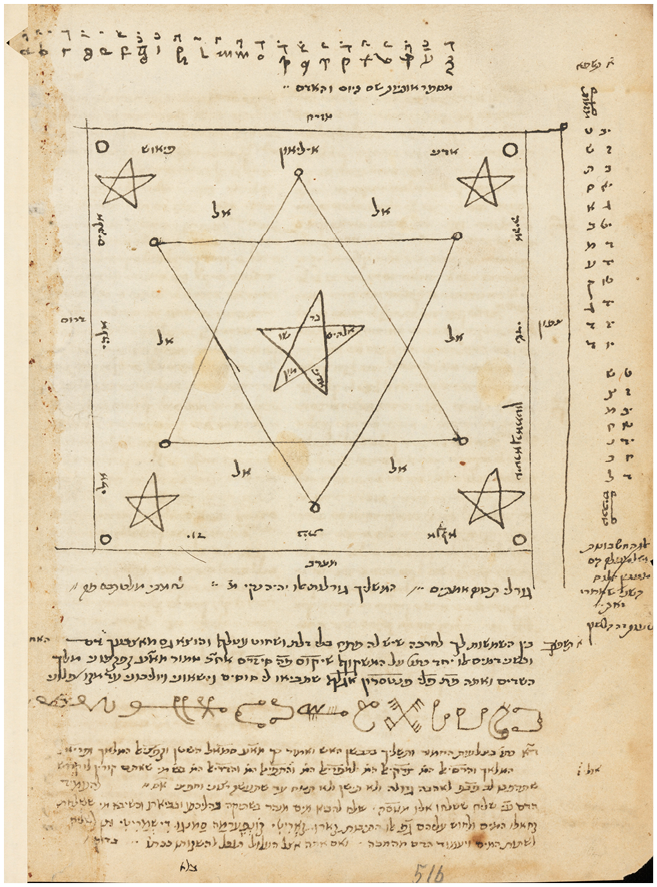

Make the following figure [Figure 2] in any metal and place it over the cause while reading the following words. Therefore, when you have made this figure, you will encircle your cause or a person with it. And, in the center, burying [it] from above or below while saying: “O spirits and demons, masters and barons, fathers of principal malice, powerful, secret, and universal. I conjure you by the power of the Creator and by his secret deeds and words, by the sun and the moon, and by all the lunar bodies of the sky, you, who are sealing the parts by the seal of Sememphorash that dominates over you. By Yaua Eyeassereye Saday Annora Theos Eloy Alla El On, our God (deus). Whenever you whom I have sealed over this matter in this seal of such metal, I command you, whenever you seal this matter, compel, preserve, and strongly guard [it], remembering your names thus.” In the circle of the world [say]:Footnote 47 “Sathan, Maymona, Zeab, Abnalaamar, Amtanasfar, Amnazart, Roya, Lucefyel.” In the East: “Rachanay, Corcoban, Rahach.” … [And] Nine times toward all the parts: “Baassocaf, Lucifer, Bethala, Beelzebub. Carry out the command, servants of God Adonai. For I, N., commend you under a pledge to keep this N. and to enchant [it] so that by itself, nor through another, nor through any of the creatures that are under the sky, can it be removed from this place.” Footnote 48

Here we witness a kind of magical recipe that aims to harness the power of spiritual entities to protect, compel, or guard a particular object or person. This procedure starts with the creation of a specific figure, crafted from any metal, which is then placed over (or under) the object or person it is meant to influence. Once the figure is positioned, the practitioner encircles the intended object with the metal figure. The practice involves a series of invocations and names of spirits and demons, calling upon entities across different cardinal directions. In each direction on the figure, there are specific names of spirits that the practitioner commands to bind and guard the object. The names vary from recognizable ones, such as “Lucifer” and “Beelzebub,” to less familiar ones. Finally, the practitioner seals the ritual by repeating a command nine times, directing it toward all parts of the world.

Figure 2 ad omnia incantanda (Kassel, Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel, 4° MS. astron. 3, 142v).

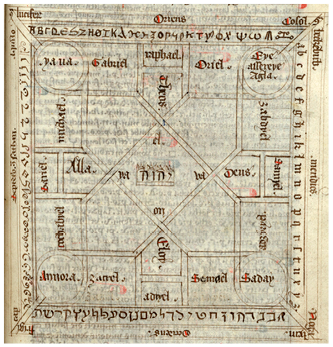

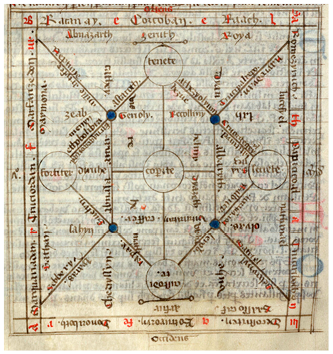

The recipe is full of interesting elements, but since our discussion here has revolved around Arabic sources and the attribution of magical knowledge to the Arabs, our focus will be on such markers of multicultural magic. First and foremost, one can easily observe how important it was for Ganell to mention the names of God in all four languages of magic: Greek (Theos), Hebrew (Eloy), Arabic (Alla), and Latin (Deus). This is a hallmark of Ganell’s system of magic, and he created a whole Tabula that expresses the idea that the four languages of magic, through these godly names, drew their power from the tetragrammaton (Figure 3). The spatial aspect of the Tabula was also used in this magical figure, which – as the Tabula – is not a magical circle (in which we expect to find the labels that signify the four cardinal directions), but an instrument. For all these reasons, the shaping of the whole figure is undoubtedly of his own pen, as well as the formula “By Yaua Eyeassereye Saday Annora Theos Eloy Alla El On, our God”; this is Ganell’s signature.

Figure 3 Tabula Semamephoras (Kassel, Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel, 4° MS. astron. 3, 38r).

Yet we can find several names in the recipe that seemingly derive from non-Latin, and even specifically Arabic, sources. Consider, for example, the names “Maymona, Zeab, Abnalaamar, Amtanasfar,” which correspond at least partially with Arabic demonological knowledge that existed before the fourteenth century, in which demonic kings are often named after colors.Footnote 49 I refer here to the demons Maymūn (ميمون), al-Maḏhab (المذهب, possibly through the Hebrew zahav, transliterated as Zeab), ibn al-Aḥmar (ابن الأحمر), and possibly a lesser-known ibn al-Aṣfar (ابن الأصفر). Relying on these Arabic names, one can see why Ganell attributed this recipe to none other than the wise Saracens: “Alternative [method], a most skilled work for enchanting everything, which was used extensively by philosophers and wise Saracens.”Footnote 50 As mentioned earlier, Ganell tried to posit his magic among the contemporaneous philosophers’ knowledge. The attribution of this recipe to the Saracens – a pejorative for Arab Muslims during the Middle Ages – seems to be derived from the same motivation.Footnote 51

The reader who comes across the attribution of this recipe to the Saracens might believe it is genuine; perhaps Ganell somehow met with Muslims who helped him develop his practice, a possibility that should not be ruled out. He, after all, does not seem to use “Saracens” as a pejorative, and in this specific case he described them as wise (Sarraceni sapientes). However, as we have already seen, at least one formula in the recipe is his own, and so is the figure’s design. Thus, there is no reason to see this attribution as a historical record of an actual encounter. I suggest it is rather an encounter with the imagined Arab magicians, whose knowledge Ganell was eager to access. Interestingly, the Arabic names recorded in this recipe were available to Ganell through a Latin work, an appendix to Liber Razielis that he owned. That is, the intercultural encounter here is indirect, mediated by a Latin source. This appendix, Liber Theysolius, is attributed to Theyzelius (or Theysolius) the philosopher, who apparently wrote a commentary on Liber Razielis.Footnote 52 All the Arabic names that Ganell employed were already in Liber Theysolius, suggesting that Ganell derived these names from this source to craft his distinctive “Saracen” recipe.

In essence, Ganell concocted an entire recipe but attributed it to imagined philosophers and wise Saracens, whom he perceived as part of his magical-intellectual milieu. These figures are portrayed as reliable and authoritative, and their knowledge is not only trusted but also valued highly. This aligns with the medieval notion among philosophers that truth should be sought in the original language of translated texts, which is often Arabic.Footnote 53 Yet Ganell’s scribal strategy is by no means new or innovative, and he was probably also inspired by his sources.

Liber Theysolius, as its name suggests, indicates a Greek source. Theysolius the Greek, as already suggested by Gentile and Gilly, is probably an alias of Toz Graecus, who is often mentioned as the source for other Hermetic texts.Footnote 54 Yet a closer examination of the contents of Liber Theysolius reveals that Greek influence is, in fact, minimal, and the Hermetic and image-magic materials so closely associated with Toz are notably absent.Footnote 55 I would therefore argue that this attribution, too, belongs to the type discussed earlier: a deliberate effort to anchor the knowledge within a particular tradition, guided by a sharp awareness of how such knowledge circulated – along with the names and authorities that lent it legitimacy, authorial voice, and stable ground for the emergence of this multicultural magic.

For a modern reader, such shifting attributions can appear like a sleight of hand. Medieval compilers, however, were operating within what Michel Foucault called the author function: a device that groups texts, differentiates them from others, and signals the status a discourse should enjoy within its community.Footnote 56 For medieval and early modern scholars, as widely acknowledged by modern scholarship, such attributions were necessary navigational aids through a labyrinth full of different works. Attributing texts to well-known figures, or to names that “sound like” nonspecific figures of a specific “kind,” as we will see later, enabled practitioners to quickly evaluate the materials in their hands and place them within their own intellectual endeavors.Footnote 57 In other words, the nomen auctoris acted as a pragmatic tool of “thrift” that channeled the potentially “cancerous and dangerous proliferation of significations” which Foucault identifies as the motivation for maintaining the author function at all.Footnote 58

Ganell’s creation of his Summa exemplifies this practice; he referred to it as a Summa because it synthesized various stands, aiming to reconcile differences among authorities or propose intermediary solutions.Footnote 59 In this context, attributions were more than mere labels; they were vital to the scholarly discourse, acting as markers within the established literary conventions.Footnote 60 In Foucault’s terms, the names did not pass “from the interior of a discourse to the real and exterior individual who produced it,” but remained on the edge of the text, characterizing its mode of being and the conditions under which it should be received.Footnote 61 Recognizing this economy of names helps us avoid both anachronistic suspicions of forgery and uncritical acceptance of single-lineage origin stories.

Of course, Ganell was far from being the first medieval author to collect magical texts from different languages, and one of the compositions that most influenced him – that is, the Latin Liber Razielis – was precisely this type of compilation. This work – a collection of various texts explicitly combined into a “book” – was created at the request of Alfonso X, king of Castile, whose translation project also included magical texts.Footnote 62 In several places in Liber Razielis – as well as in the Picatrix, another magical work translated at the king’s court – we find references to the Arabic and Indian languages, and in the case of the Picatrix, occasional mentions of Indian sages. The extent to which these references reflect a historical account or draw on a specific textual tradition remains an open question that still calls for further research. Yet, as Attrell and Porreca noted, such references might as well be read as “an example of a sort of medieval Arabic ‘Orientalism,’ whereby the Indians are thought to be an inherently more mystical people by virtue of being a distant (but not too distant) ‘Other.’”Footnote 63

Given that Ganell was well acquainted with Liber Razielis and the Picatrix, it is likely that he embraced the rhetorical style of his Latin predecessors. Attributing knowledge to distant and sometimes exotic sages was a literary strategy that not only helped authors disseminate their works but also positioned them within a wider intellectual discourse. This was the case for Geber, and it equally applies to Ganell’s references to the wise Saracens. This would not be the first time Ganell employed such attributions for this purpose. Elsewhere in the Summa, we find none other than Rabbi Akiva presented as the authority behind a calculative method – a name Ganell had encountered in Liber Theysolius.Footnote 64

Attributing magical texts to distant or legendary figures is a long-standing practice, dating back to antiquity through the medieval and early modern periods.Footnote 65 In the early modern period, as in the Middle Ages, such attributions could be linked to stories of recovering lost or stolen wisdom.Footnote 66 In other cases, they serve as a tool for drawing boundaries between illicit and licit forms of magic. Consider, for instance, a recipe for summoning omniscient entities that circulated between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, and which, in the eighteenth century, was prefaced with a prologue recounting the story of Rabbi Eliezer, who received a book from his father, Isaac:

And our Rabbi, Isaac, his father, went to wander in the world because he was hard-pressed for money, and he studied in several places in Babylon and Egypt. When he returned to his land, he brought a book known to the sages of Babylon and the knowledgeable sages of Egypt as “Anigryon,” which in the Egyptian language means “Book of Hours.”Footnote 67 Rabbi Eliezer, his son, seeing that his fortune was favorable, began to engage with it, and he prospered with it for many days until one time, his luck turned, and he almost endangered his life and body. Immediately, when the harmful spirits overpowered him, they did not leave him until he swore to them that he would no longer endeavor in this matter, and so he did.Footnote 68

After this risky attempt, Eliezer received a revelation from Elijah the prophet, who revealed to him the secrets of the following recipe, that is, the recipe that circulated for four hundred years before without mentioning this whole story. The function of the Egyptian and Babylonian imagined sages here is quite different from what we have seen. They are here to mark the illicit, or even defective, and risky practice, in contrast to the recipe that the author offers to the reader. They are not less imaginative, as is the revelation of Elijah, who gives the authoritative voice to the recipe.

Attributing a recipe to an “Arab magician” does not, by itself, prove a specifically Arabic source; the name can be a literary tool even when Arabic elements are present. In cases like these, the emerging picture is sometimes complex and ambivalent. Ganell’s Summa illustrates the ambiguity: He attacks Islam and Judaism yet eagerly borrows Arabic lunar mansions and Hebrew angelic lore, sometimes presenting this appropriation as the recovery of ancient wisdom. He denounces their prophet and accuses them of practicing nigromancy in defiance of God but still draws upon what he perceived as their wisdom. This act of appropriation could at times be framed as the recovery of lost or stolen knowledge – though, as Ganell’s Summa and the “Geber problem” show, this was not always the case.Footnote 69 With this in mind – that attributions to Arab sources could function as literary tools for shaping an author’s work within particular historical and cultural contexts, and that attitudes toward the “Other” were often layered and shifting – let us turn to a case in which an Arab author is credited as the source of a Latin magical text typically regarded as an “Arabic work.”

2 The Seven Names: Revisiting an “Arabic Magic” Work

In 1987, the late David Pingree published a programmatic article entitled “The Diffusion of Arabic Magical Texts in Western Europe.” In it, Pingree offered a systematic survey of more than fifty Latin manuscripts containing works translated from Arabic before 1300.Footnote 70 According to him, these magical texts were transmitted across medieval Europe in several phases.Footnote 71 The earliest phase can be traced to the late eleventh century, when a small number of Arabic texts were first translated into Latin in Italy, and from there made their way to France and England by the early twelfth century. During the twelfth century, additional works translated in Spain reached France and England, attracting considerable interest within intellectual circles in Paris, particularly among figures such as William of Auvergne (d. 1249).Footnote 72 The next major phase took place at the court of Alfonso X – a figure we have already encountered – and involved translations from Arabic and Hebrew sources, which spread into Southern France, especially Montpellier. With this article, Pingree established what we might call the “classical narrative” of the diffusion of magical texts.

In another groundbreaking article, Pingree analyzed a fifteenth-century Latin manuscript preserved at the National Library in Florence, building on his previous research. He compared the works contained in this manuscript with the descriptions – often polemical – provided by William of Auvergne and the author of the Speculum Astronomiae.Footnote 73 According to Pingree, this manuscript represents one of the most complete extant copies of the new magical texts that reached France from Spain, offering scholars like William an opportunity to encounter them. Thus, the descriptions offered by these theologians are regarded as historical evidence for the circulation of these texts. Indeed, the resemblance is striking – down to the sequence of titles mentioned by the critics, namely William and the author of the Speculum – and supports Pingree’s argument. This alignment reinforces the historical credibility of their descriptions as evidence of the texts’ circulation.

Pingree’s identification of this Florentine manuscript remains, thus, persuasive. What it does not establish, however, is that every tract the critics saw had followed a linear route from an Arabic original into Latin. This also does not necessarily mean that the texts encountered by these two critics followed precisely the pathways outlined in Pingree’s “classical narrative,” nor does it attempt to describe the complex transmission process. In the following sections, I will question the assumption that all these texts were translated directly from Arabic into Latin. Instead, I will explore alternative possibilities that view intercultural encounters not simply as exchanges between passive (recipients) and active (creators or transmitters) agents but as dynamic processes that may have shaped these texts already in their formative stages.

The following discussion would not be the first to question the generalized argument. Following studies on specific texts, the conclusions of Pingree’s articles were recently revised and updated by Jean-Patrice Boudet, who also pointed to works that Pingree assumed to be Arabic in origin but are probably not (e.g., De lapidibus).Footnote 74 It is my attempt here to follow this direction but also to suggest that the imagined Arab magician might have contributed to the articulation of such arguments in the first place. It is essential to state, however, that nothing here challenges Pingree’s entire list: Many texts he treated as Arabic derive demonstrably from Arabic exemplars. The discussion that follows concerns only those pieces for which the putative Arabic source is lost, and no internal evidence points to a full, word-for-word translation that can support the use of the “Arabic magic” category to describe the (lost) origin. In such cases, a more complex chain of compilation – spanning Hebrew, Latin, and perhaps Greek inputs – remains a real possibility, and tracing that complexity is the chief purpose of the sections that follow.

Since Pingree’s examination of this codex – and Lynn Thorndike’s before himFootnote 75 – the Florentine manuscript has become well-known among scholars of medieval magic, who have examined various parts of it. As noted, Boudet studied several of its treatises, as did Charles Burnett, Lauri Ockenström, Vajra Regan, Julien Véronèse, and others.Footnote 76 The manuscript’s remarkable diversity of sources has drawn particular attention, and the fact that it appears to incorporate treatises known to have circulated together – that is, within close geographical proximity – has made it a compelling case study, often understood as preserving a textual tradition that stretches back at least two centuries. Indeed, some of its sections correspond to eleventh-century Hebrew and Aramaic texts, while others align with known earlier Arabic works.Footnote 77 In what follows, I wish to discuss another work that Pingree classified as Arabic, primarily based on its short prologue.

The treatise under discussion, which is untitled in the manuscript but which I will refer to as The Book of Seven Names (Liber septem nominum), or simply The Seven Names, following Thorndike’s identification,Footnote 78 has received little scholarly attention and was only recently discussed in detail by Burnett in an article devoted to writing materials and processes in magical texts.Footnote 79 Unlike Pingree, who argued for a lost Arabic origin of the work, Burnett has proposed an ultimate Hebrew origin – an argument I wish to develop further through a close examination of the text itself, presented here with an edition and translation in the appendix of this Element.

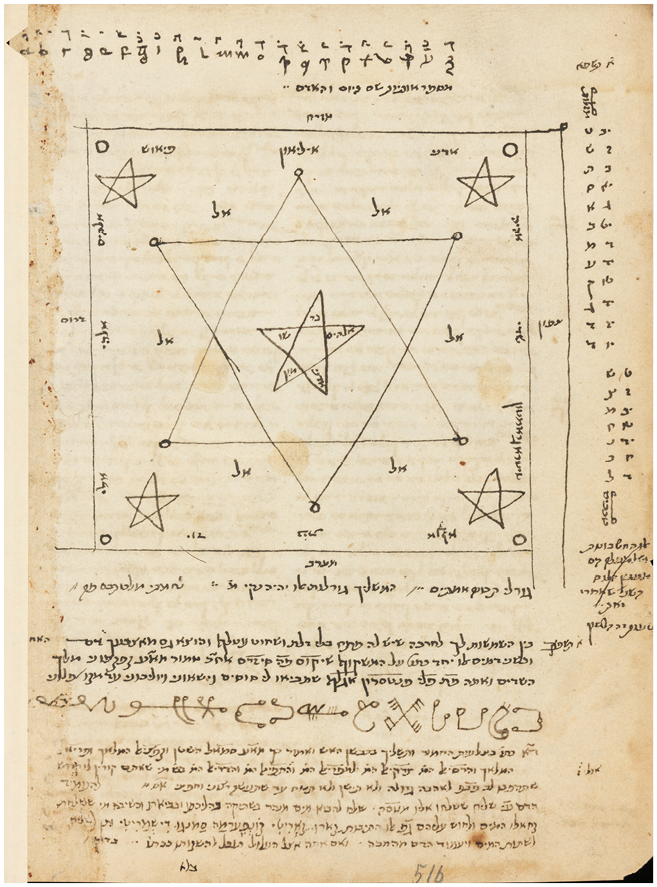

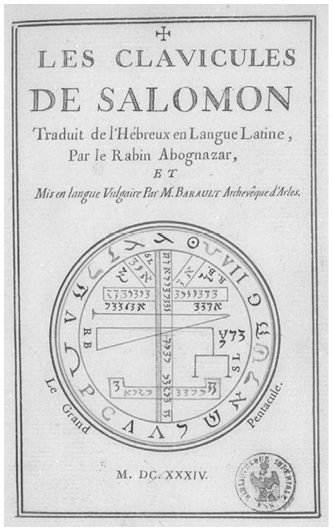

The Seven Names is a short work attributed to a figure with an Arabic – and more specifically, Islamic – name: Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan ibn al-Maʾmūn (given in Latin as Muhamet filius Alhascen et filius Amoemen, § 1).Footnote 80 The name appears within a long chain of transmission, a literary feature typical of Arabic literature. Such chains, attributing the work to a sequence of named authorities, are known in Islamic literature as isnād. A work that opens with such an extended list of names – all are clearly transliterations of common Arabic names – could almost automatically be classified as an “Arabic work,” as Pingree indeed considered it.Footnote 81

Mindful of the “Geber problem” – and of medieval compilers’ habit of crediting their own work to renowned authoritiesFootnote 82 – we should approach apparent authorial attributions with caution. When a Latin treatise is called an “Arabic work,” even though no Arabic exemplar survived, that label signals a hypothesis rather than a documented process of transmission. Because attributions were shaped by the compiler’s historical and cultural setting, each case should be tested on three levels: (1) the manuscript’s provenance, (2) the intellectual milieu that encouraged a given ascription, and (3) a close reading of the text itself. In the absence of an Arabic witness, I would prefer to use “multicultural magic” that signals the presence of several traditions without implying a homogeneous Arabic source that cannot be demonstrated at the present time.

The label “Arabic work” can be helpful as shorthand, yet – if left undefined – it may blur the very historical, cultural, and religious contexts we hope to illuminate. Does “Arabic” in a given case refer to a pre-Islamic setting, an Islamic milieu, a linguistic layer, or something else? In a Latin manuscript, the term cannot describe the script itself; it signals a presumed Arabic-language source. Unless we also specify where, when, by whom, and for whom that putative source was produced, the label remains hypothetical rather than evidentiary. In the case of The Seven Names, I suggest that a close reading of the text may reveal a complex history of transmission. A careful examination – particularly one that considers the introduction as an integral part of the text itself, rather than treating it as a piece of metadata or a historical record – allows us to reflect on the possible historical and geographical context in which this work was composed. Yet, inevitably, this hypothesis must remain a hypothesis until further evidence comes to light, as research continues to progress.

Before turning to the text itself, it is worth pausing to consider the function of prologues and attributions within this codex, where such features appear. The Florentine manuscript comprises approximately forty-nine treatises and experiments, some of which are explicitly attributed to specific figures, while others are not. Generally speaking, short recipes and experiments tend to lack such attributions, while longer treatises are more likely to include them.Footnote 83 For example, the Liber de locutione cum spiritibus planetarum (Book on Conversation with the Spirits of the Planets) is presented as the sayings of “Abuelabec Altanarani, a certain philosopher and astrologer, [who] spoke about what he found in the books of the ancients.”Footnote 84 Pingree discussed this attribution to Abuelabec Altanarani, whom he identified as al-Ṭabarānī, noting that this figure is also cited in the Picatrix. Although in that context the material is incorporated alongside other sources, it is still attributed to al-Ṭabarānī.Footnote 85

Other treatises in the Florentine Codex are attributed to more “distant” figures – some biblical, others divine. Consider, for example, the Liber de secretis angelorum (The Book on the Secrets of the Angels), which is said to have been given to Adam by the angel Rachael (that is, Raziel).Footnote 86 Such an attribution plays a role in the history of the text, as well as its cultural context.Footnote 87 Another example is a treatise often classified as “Solomonic,” but is in fact attributed to the disciples of Solomon: “Here begins the treatise of the disciples of Solomon, that is, Fortunatus, Eleazarus, Macarus, and Toz Grecus.”Footnote 88 It seems evident here that the author – possibly inspiring Berengar Ganell, who was familiar with this work – sought to signal the different sources upon which he drew: Latin (Fortunatus, Macarus), Hebrew (Eleazar), and Greek (Toz). In another version of this treatise, preserving the same attribution, we indeed find ritual formulas composed of Hebrew liturgical phrases alongside Greek nomina magica.Footnote 89 As we have already seen, authors were aware of the nature of their sources, and attributions were often employed to frame a work in a particular way. In the case of Ganell, this is reflected in the Saracen recipe he invented; in the case of the Ydea Salomonis, it is reflected in the author’s prologue and deliberate incorporation of different traditions – Latin, Hebrew, and Greek – to construct a ritual.

This is not the only instance in which the Florentine Codex reflects this somewhat “inclusive” approach by hinting at or mentioning foreign sources. Another treatise, the Liber Bileth (The Book of Bileth), which instructs practitioners on how to summon the demonic king Bileth, contains an interesting formula that may offer insight into the author’s identity and cultural background – or at least into his proficiency in different languages: “And for this reason we sit in this circle, and so that you may reveal to us everything present, past, and future – in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin – with the most perfect and wholly intelligible knowledge.”Footnote 90 Here, the author seems to associate himself, and perhaps those with whom he shared this knowledge, with individuals capable of communicating in one or more of these languages. Of course, this gesture of inclusion is simultaneously an act of exclusion: We might wonder why Arabic is absent from a text that elsewhere refers to figures well-known from Arabic literature, such as Hārūt and Mārūt.Footnote 91 In any case, the awareness of foreign languages (as both relevant to the practitioner and as markers of written traditions) left clear traces in the text. This often contributed to the creation of genesis narratives, or to the attribution of a text to particular figures, shaping the work’s structure and reception.

Having considered some of the prologues and attributions found in various treatises within this codex, let us now turn to The Seven Names and its content. The treatise sets out a relatively straightforward theory: God assigned one of His seven names to each day of the week, making each day distinct and uniquely suited to specific forms of magical practice. In other words, ritual activity performed on a particular day – by invoking its corresponding divine name – will produce a specific, well-defined result. This is presented as grounded in the cosmic structure organized around the number seven: God created seven seas, seven heavens, and seven earths. He also created seven spheres, or circles (VII circuli), each governed by a specific angel. By that, the introduction argues for a connection between the seven names of God and this cosmic system of seven, which “all time runs through” (§ 1). Properly using each name requires specific ritual actions (writing on specific materials, fasting, bathing, suffumigation, and exorcism) to harness its power. Aligned with the sacred order of the days, triplicities, angels, winds, and stars, these rituals aim to invoke miracles, from healing and protection to love, war, and other concerns.

Following the brief prologue, the treatise proceeds systematically: Each of the seven names is discussed in relation to the specific day on which it must be used, beginning with the Sabbath (Saturday). Sometimes, the cosmological framework introduced in the prologue is recalled. For example, the second name is to be used on Sunday, and the text notes that it “is placed in the sixth heaven, and its angel is in the sixth heaven, who, with this name, adores the Creator” (§ 3). This return to the cosmological structure outlined in the introduction, however, gradually disappears. In the case of the fourth, fifth, and sixth names, there is no further mention of their placement within the heavens.

This cosmological framing returns only with the seventh and final name, which is said to be established in the highest heaven. On the surface, this structure might suggest a gradual ascent or hierarchy of names, increasing in power. Yet the organization of the treatise does not consistently support this reading. It even appears to contradict it, since the first name is described as the greatest of all (§ 2), without any reference to its location within the cosmic order.

In each of the initial sections on the seven names (§§ 2–8), the names themselves are conspicuously absent. Instead, the text instructs practitioners on their ritual use, typically to write them on surfaces like parchment or clay with natural materials, some of which appear in Latinized Arabic forms, as Burnett has noted.Footnote 92 In some cases, the names also require specific suffumigation. For example, the seventh name, associated with Venus, must be written on sheep parchment using ink made of egg, and suffumigated with aloe and sandalwood (§ 8). These kinds of instructions are typical of magical recipes circulating in the period. What sets The Seven Names apart, however, and distinguishes it from other recipe collections, is the overarching narrative and theoretical framework concerning the divine names.

As a practical manual, this treatise is certainly not a beginner’s guide. While some instructions are given in considerable detail, the intended purpose of each operation is not always explicitly stated, and is sometimes only implied. For instance, a recipe is described as merely “pertaining to the name of the Sabbath day” (§ 2). For a student of astrology, this would not be difficult to infer; Saturday is governed by Saturn, and thus familiarity with the Saturnian qualities would enable the practitioner to discern which operations were appropriate for that day. This principle is made explicit in some instances. For example, the seventh name, associated with Friday, is connected to the qualities of Venus: “But this name is especially granted to womanly love” (§ 8). Yet the application of this logic is far from consistent: Other names are also linked to “womanly love” (§ 5, § 12).

It is precisely this overarching theory and its characteristic “bundling” of practices that call for careful examination. A close reading of the text reveals that the treatise – a compilation of scattered recipes – bears traces of editorial intervention. The inconsistencies throughout the work are often striking and sometimes confusing, suggesting that we are dealing with a text that has been edited, reworked, and possibly left incomplete. This would also help explain the most conspicuous absence: The seven names themselves – the very foundation of the treatise – are never actually provided within the text.Footnote 93

The inconsistencies within the treatise become most apparent when we compare its first part (§§ 2–8), which describes the seven names and their ritual use, with its second part (§§ 9–15) and third part (§§ 16–30). The second part focuses primarily on the exorcisms that must accompany the use of each of the seven names. Structurally, it corresponds to the first part: Each of the seven paragraphs provides the exorcism associated with the respective name introduced earlier. However, this part also introduces entirely new elements – sometimes contradictory to what has been previously described – that were not mentioned in the first part. For instance, the practitioner is now instructed to inscribe a set of “rings” as part of the writing process (§ 9). In several cases, these additions contrast with the material introduced in the first section, raising further questions about the treatise’s coherence and transmission history. Let us examine such a case more closely.

According to the first part of the treatise, the third name, which corresponds to the moon, “presides over those crossing roads and those who become lost in the sea, or crossing it, and merchants” (§ 4). The figures listed here share a common theme – movement and travel. While this passage does not explicitly state when the name should be written, it is implied (in line with the treatise’s general structure) that it should be inscribed on the corresponding day, that is, Monday. Such instructions are either explicitly stated (§ 3, § 6, § 7) or implied (§ 2) for most of the names in the first part.

However, the second part of the treatise, which discusses the exorcism associated with the third name, introduces entirely different purposes. Here, the third name is said to be effective in addressing kings or for use in war. Most strikingly, the exorcism itself functions as a love spell: “That the heart of that N., daughter of that N., may serve me” (§ 11). Moreover, the text states that the third name may also be written on the day of Venus (Friday) to be used for love magic – a clear departure from the cosmological framework laid out in the first part.

This inconsistency is not limited to the third name. The treatment of the fourth name offers another striking example of the contradiction between the two parts of the work. In the first part, the reader is instructed to write this name – associated with Mars – using the blood of a dove (§ 5). Yet, in the second part, the practitioner is told to write it with saffron, musk, and aloe (§ 12). Such inconsistencies are scattered throughout the treatise, with some of the most significant differences appearing between its first and second parts.

The third part of the treatise continues along the lines of these phenomena, further complicating the structure and coherence of the work. It begins with general preparatory requirements expected of any practitioner of this art (magisterio), which include bathing, fasting, and suffumigating (§ 16). Similar instructions already appeared in the first part of the treatise, but they are not always consistent. For instance, while the third part instructs practitioners to fast and bathe for three days before any operation, the second part prescribes, in the case of the fifth name, only a single day of preparation (§ 13).

The third part of The Seven Names goes beyond general instructions, offering name-specific rites (§§ 17–22). Its content raises questions about whether it was part of the treatise’s original design. It introduces a different theoretical framework, one that is briefly echoed in the second part, centered on the triplicities (the year’s four seasons, each with three months). Unlike the first part, which is structured around the number seven, this section emphasizes the seasons as the cosmic forces behind the recipes and their efficacy.

Perhaps the most striking indication that this third part may represent a text of separate origin is the explicit reference to another book: “And this is the book of Heh’eben, son of Joseph, the greatest sage, and through this divine knowledge he knew the days and wet years” (§ 16). Here, the author explicitly attributes the theory of triplicities and the associated knowledge to an otherwise unidentified sage, Heh’eben son of Joseph (Yaḥyā ibn Yūsuf ?) – a figure that is entirely absent from the earlier parts of the treatise.

The striking inconsistencies found throughout the treatise – on practical, theoretical, and structural levels – strongly suggest that we are dealing with distinct traditions that were brought together. Unlike the first part, the second and third parts of the treatise appear to share more in common, particularly in their use of the theory of triplicities. Before turning to this aspect, however, I would like to highlight some of the explicit Arabic references within the text.

Beyond the Arabic isnād found in the prologue, The Seven Names mentions other well-known Arabic figures. In the second part, specifically in the paragraph concerning the first name (§ 9), there is a clear allusion to the Abbasid caliph Hārūn ar-Rashīd, here referred to as “King Aron [or Haaron] in the East.” The same passage states that a philosopher and astrologer named Algorismus (the common Latin form of the name of the renowned mathematician Al-Khwārizmī)Footnote 94 attributed the first name to one of Hārūn’s prisoners. While Al-Khwārizmī is known to have worked in the Abbasid House of Wisdom, this activity took place after Hārūn’s death.Footnote 95 It remains unclear whether this passage draws on any existing tradition in either Latin or Arabic sources, but its central logic relies on two notions: Al-Khwārizmī’s reputation as a scholar and the prisoner’s power to overcome or influence the king who imprisoned him. Interestingly, this theme does not align consistently within the treatise itself: According to the first part (§ 7), the sixth name is associated with influencing kings, while in the second part (§ 11), it is the third name that is linked to this power. This again underscores the internal inconsistencies between the different sections of the work.

As previously noted, several of the ingredients mentioned in The Seven Names appear in Latin transliteration from Arabic, with varying degrees of clarity and accuracy. For instance, the reference to parchment made of areignum likely derives from al-ḡanam (“sheep”), while the day Alcoara seems to stem from az-zuhara (“Venus”). This pattern is not limited to termini technici or materia magica, but also extends to certain verbal formulas. For example, the exorcism of the fourth name (§ 12) opens with unmistakably Arabic words: “Bisam Yley Eulum Escelectum” – the first words being a transliteration of the well-known Islamic formula bi-smi ʾllāh (“in the name of Allah”). Moreover, some of the angelic names that appear in the text also seem to reflect Arabic forms. One notable case is “Scellim L’eli Acimaleycum,” where the author presents them as names of angels. Yet their linguistic form suggests otherwise, particularly the -aleycum ending in the third name, which echoes the Arabic ʿalaykum (“upon you”). This may point to a greeting formula, with Scellim deriving from as-salāmu (“peace”), a not uncommon formula in rituals involving encounters with angelic or demonic figures.Footnote 96

The exorcism of the sixth name (§ 14) further supports this observation, as it contains a formula that again draws directly on Arabic. The phrase “Bis Mellah” is another transliteration of bi-smi ʾllāh, followed by the invocation of angels whose names correspond to Mīkāʾīl (Uuremich’l) and ʾIsrāf īl (Uuescerafil). This Arabic resonance is reinforced not only by the names of the angels but also by the description of their appearance in the same passage: “Their heads are in the heavens, and their feet touch the ends and boundaries of the earth, and their wings touch the East and the West.” Such imagery is well attested in Islamic tradition. Consider, for example, Abū Manṣūr al-Daylamī’s Musnad al-Firdaws, a collection of hadiths, where one finds a similar description of an angelic figure (the “cockerel”): “Its feet are on the boundaries of the lowest [earth] and its folded neck is under the Throne; its wings are in the East and the West.”Footnote 97

What can we learn from this intercultural encounter, in which a Latin-writing author, most likely Christian, incorporates Islamic formulas? Is it merely an isolated case? Moreover, is there evidence to determine whether this interaction is direct or indirect? The presence of Arabic terms and formulas strongly suggests that an Arabic treatise may have been translated here, possibly inspiring Pingree’s view that The Seven Names originated in Arabic. Yet, as I have argued, such an assumption may overshadow other clues indicating a more complex process of cultural exchange that shaped The Seven Names. One might wonder why, if the author was a skilled translator, certain formulaic passages fail so noticeably. Copying errors could explain some instances, such as the transformation of bi-smi llāh into “Bisam Yley,” but that rationale falters when we consider examples like “Scellim L’eli Acimaleycum,” which the author interpreted as angels. Indeed, at least some aspects of The Seven Names – already identified as comprising two or perhaps three different parts – complicate the notion of a straightforward, complete translation from Arabic into Latin. Further evidence of intercultural exchange, this time likely reflecting Jewish traditions, challenges the notion of a straightforward translation and invites a more nuanced reading of The Seven Names. These traces not only complicate the idea of a wholly Arabic (Islamic) source but also offer clues about the cultural environment, and perhaps even the time and place, in which this work took shape.

I would like to highlight three instances in The Seven Names that demonstrate an engagement with Jewish textual traditions. The first concerns the first name that is associated with the Sabbath, which is described here as the day on which Moses received the Torah (§ 2). In the Babylonian Talmud, Rava (a Babylonian amora) asserts that “everyone agrees that the Torah was given to the Jewish people on Shabbat.”Footnote 98 This notion recurs in Jewish sources from the Middle Ages onward, while both Muslims and Christians generally refuted the sanctity of Saturday as the holiest day of the week.Footnote 99

Naturally, proposing to perform a ritual (particularly one involving writing and suffumigation) on the Sabbath would raise halakhic concerns for Jewish practitioners. Yet, as is well-known, such internal debates did not always prevent the practice of magic, and the question of which actions were permissible remained open to interpretation.Footnote 100 Still, as Ortal-Paz Saar has shown, Jewish authors often took care to avoid prescribing actions that would explicitly desecrate the Sabbath.Footnote 101 I suggest that The Seven Names reflects a similar sensitivity. A close reading of the treatise, especially when considering its three parts together, indicates that – unlike the other days – there is no explicit instruction to perform any ritual act on the day of Saturn (Saturday). While the first part does not consistently specify that the name associated with each day must be written precisely on that day (e.g., Sunday in § 3, Wednesday in § 6), the third part adopts a more uniform and structured pattern – and omits Saturday altogether. This final part lists the days of the week alongside their associated powers but excludes any instructions for Saturday, suggesting a deliberate avoidance that aligns with Jewish concerns over Sabbath observance.

The second case that shows signs of an engagement with Jewish textual traditions appears in the second part of the treatise, which contains various exorcisms and verbal formulas to be used. As we have already seen, some of these formulas are undoubtedly Arabic, and there is at least one easily recognizable Greek word – Ἅγιον (§ 10). Another formula, found in the exorcism of the third name (§ 11), is composed of both Hebrew and Aramaic passages, drawing primarily on biblical texts, though not exclusively. The author’s transliteration practices complicate identification: Words are frequently merged or split, and vowels are commonly doubled, yet there is a certain consistency in the representation of specific Hebrew letters. For example, “uu” for ו, “sc,” “sh,” or “ss” for ש, and “x,” “xc,” or “xh” for כ/ח.Footnote 102 Because of this instability (the splitting or merging of words), identifying the Hebrew or Aramaic phrases can be difficult. Nonetheless, the formula (Ane Adonay formula) begins with what is clearly a prayer, though only partially recognizable at first glance:

The formula: Ane Adonay Jelohim Jeloy Ebraym and Ysaach and Israel Uueiloy Moyse Uuaharon Uueyloy …

Hebrew (transliterated): Ane Adonay ’elohim ’elohei ’avraham veyitzḥaq veyisra’el ve’elohei moshe ve’aharon ve’elohei …

Translation: Answer, O Lord God, God of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, and God of Moses and Aaron, and God of …

After this passage, not found in biblical sources but in liturgical and magical ones, The Seven Names continues with biblical verses (Adonay Bamar formula). The first one is Numbers 12:6–8:

The formula: Adonay Bamar Esloy Ydi Ydda Jeahalum and Deburbulohhun Abda Moyse Uahhol Batunamehun Uuefalel Faed Debir Uuebrai Uuelubabi Duth Uuetham Unet Adonay Iabieth

Hebrew (transliterated): Adonay bamar’a ’elav ’etvada‘ baḥalom ’adaber bo. Lo khen ‘avdi moshe bekhol beiti ne’eman hu. Pe ’el pe ’adaber bo umar’e velo veḥidot utemunat Adonay yabbit

Translation (NIV): I, the Lord, reveal myself to them in visions, I speak to them in dreams. But this is not true of my servant Moses; he is faithful in all my house. With him I speak face-to-face, clearly and not in riddles; he sees the form of the Lord.

In this case, we can observe how the author interpreted the letters “et” as the conjunction “and” rather than as part of a single word “[et]Debur[ ]bu” (that is, ’adaber bo),Footnote 103 reflecting both an oral transmission of the text and a splitting of what was originally a single word (adabber → atdaber → et daber), further merged with the next three words (“bulohhun,” that is, “bo Lo khen”). Following four words I was unable to identify at first (Uehuuegale Imilxate formula), the author cites the Aramaic of Daniel 2:22, and immediately afterward, Daniel 2:21:

The formula: Uehuuegale Imilxate Uemes Cetrethe Iedha Mebahsol’ia Udenaora Amisere. Uueh’scy Mehehtuete and Danie Uuethdimine Methe Adde Maichxcein Uueema Hal’um Mallxhim Ieib K’hohmethe Lethalxmin Uuemandaya Lyeydaa Bieteuuete

Aramaic (transliterated): Hu gale ‘amiqata umesatterata yada‘ ma vaḥashokha unehora ‘imeh shere. Vehu mehashne ‘idanaya vezimnaya meha‘de malkhin umehaqeim malkhin yahev ḥakhemeta leḥakimin umande‘a leyade‘ei bina

Translation (NIV): He reveals deep and hidden things; he knows what lies in darkness, and light dwells with him. He changes times and seasons; he deposes kings and raises up others. He gives wisdom to the wise and knowledge to the discerning.

The verses from Daniel seem to resonate with the aim mentioned in the same paragraph. According to this paragraph, the name can benefit those who address the king.Footnote 104 These biblical verses are commonly cited in recipes for dream requests.Footnote 105

These formulas raise the question of whether we are indeed dealing with a Hebrew, Aramaic, or Arabic recipe for dream requests, even though The Seven Names itself does not specify this purpose. The intersection of these three languages frequently appears in the Cairo Genizah, a vast collection of texts preserved in the attic of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat, Old Cairo.Footnote 106 While searching for a possible parallel in the Genizah, I came across a twelfth-century fragment – an amulet or spell for dream requests – written in Judeo-Arabic, yet quoting Hebrew and Aramaic biblical verses.Footnote 107 In light of this parallel, we can identify some of the Latin phrases. For instance, “Symenac Daniari Amacye Beuyaium” corresponds to the Hebrew shim‘u na devarai ’im yihye nevi’akhem, the beginning of Numbers 12:7, which is almost unrecognizable in the Latin transliteration. Still, the texts are not entirely alike: In the fragment, the order of the verses from Daniel is not reversed, as it is in The Seven Names. Moreover, some of the Judeo-Arabic passages in the Latin text are transliterations, whereas others are translations (see later in this section).Footnote 108 In any case, this would not be the first time that materials currently known exclusively (or almost exclusively) from the Cairo Genizah are attested in our Florentine Codex.Footnote 109

One might argue that the Genizah fragment represents an earlier form of The Seven Names. Yet this fragment includes a self-contained passage, lacking evidence that it belongs to a larger treatise like The Seven Names. Alternatively, it could reflect the work of a practitioner following instructions from an earlier version of the treatise. If so, the magician did not strictly follow those instructions, using paper instead of gazelle parchment and black ink instead of saffron-based ink. In either case, this parallel supports the earlier observation: The inconsistencies in The Seven Names reflect its composite nature, shaped by multiple recipes circulating in the same period and region.Footnote 110

The third indication of an encounter with Jewish texts concerns primarily the third part of the work, which, as discussed, presents a different cosmological theory. This theory of triplicities (not unrelated to the astrological notion of triplicities) holds that “the blessed God called the first season spring, the second summer, the third autumn, the fourth winter, and assigned three months to each, [and] to each triplicity [he assigned] an angel, and to each angel three other assisting angels, and to each month an angel, who, in his month, serves his Lord” (§ 23). The treatise continues by listing these angels along with the names of the sun, moon, and the winds for each season.