Introduction

Different citizens perceive and interpret political parties, candidates, messages, or phenomena differently (see, e.g., Krishnarajan, Reference Krishnarajan2023; Muraoka and Rosas, Reference Muraoka and Rosas2021; Vliegenthart et al., Reference Vliegenthart, Van Ham, Kruikemeier and Jacobs2024; Ward and Tavits, Reference Ward and Tavits2019). Where does this perceptual heterogeneity come from? We offer a new perspective to this question by bringing back the group aspect of political thinking (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Warren Miller and Stokes1960; Conover, Reference Conover1984; Miller, Wlezien and Hildreth, Reference Miller, Wlezien and Hildreth1991). We propose an analytical framework that links multiple group identifications, resulting from social profiles, ideological or cultural divides, to heterogeneity in platform perceptions. For example, a conservative citizen may perceive politics differently than one with liberal preferences, a Catholic may not interpret conservative parties like a non-Catholic, or the political views of territorial-rooted citizens may differ from globally-minded ones.

Our analytical framework draws on the well-established social identity theory (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981), which has been used to comprehend preferences, values, beliefs, trust and movements (Egan, Reference Egan2020; Gustavsson and Stendahl, Reference Gustavsson and Stendahl2020; Klandermans, Reference Klandermans2014; Shayo, Reference Shayo2009; Verhaegen, Hooghe and Quintelier, Reference Verhaegen, Hooghe and Quintelier2017; Zapryanova and Surzhko-Harned, Reference Zapryanova and Surzhko-Harned2016), campaigning, voting behavior and party strategies (Ansolabehere and Puy, Reference Ansolabehere and Puy2016; Bornschier et al., Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021; Sides, Tesler and Vavreck, Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2019; Tavits and Potter, Reference Tavits and Potter2015), or partisan affect and polarization (e.g., van Erkel and Turkenburg, Reference van Erkel and Turkenburg2022; Huddy, Mason and Aaroe, Reference Huddy, Mason and Aaroe2015; Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes, Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2018; Wagner, Reference Wagner2024; West and Iyengar, Reference West and Iyengar2022). We contribute to this literature by bringing identity-based reasoning into the study of party placement perceptions, where the key result is that citizens have no common perceptions (e.g., Aldrich et al., Reference Aldrich, Schober, Ley and Fernandez2018; Dahlberg, Reference Dahlberg2013; Meyer and Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2020; Potter and Dunaway, Reference Potter and Dunaway2017; Somer-Topcu, Reference Somer-Topcu2015; Ward and Tavits, Reference Ward and Tavits2019).

Our approach is based on the idea that membership in social groups has the potential to act as a social identity by systematically structuring divergence in political perceptions. The novel aspect of our framework is conceptualizing two manifestations of perceptual divergences among groups: ingroup and outgroup effects. We argue that a group membership translates into a group identity when citizens pull party placements to the preferred policy of the group they belong to (ingroup effect) or push them away (outgroup effect). Our main contribution lies in providing an empirical strategy to detect the group characteristics that divide citizens into identity groups, producing ingroups and outgroups. The framework comes with several advantages. It considers the directional perspective of group-based perceptual effects and their strengths, which permits uncovering what party activates what social identity to what extent. It allows the analysis of a wide range of group characteristics related to cultural, ideological, or socioeconomic aspects. It can be applied to multiparty systems using standard mass public opinion survey data and uncover the identity groups that produce perceptual polarization. We believe that conceptualizing group-based perceptual effects along with an empirical modeling strategy are crucial steps toward gaining a deeper understanding of how groups are tied to parties in perceiving and interpreting the political landscape.

We empirically apply our framework to the Basque region of Spain, exploring party placement perceptions in regional elections from 2009 to 2020. The Basque Country serves as a notable example of how national identities have created social divisions in recent decades (e.g., Arenas, Reference Arenas2021; McNeill, Reference McNeill2000). We focus on this case because, in addition to traditional societal divides based on class, religion, or ideology, the Basque Country also encompasses distinct national sentiments that contribute to social fragmentation. This case is not unique; similar nationalist sentiments can be found in other regions of Spain, such as Catalonia or Galicia, and in other countries, such as Belgium, Canada, Denmark, India, Italy, Pakistan, or the UK (e.g., Brancati, Reference Brancati2006; Hobsbawm and Kertzer, Reference Hobsbawm and Kertzer1992; Sniderman, Reference Sniderman2002). The Basque region demonstrates the insights that our analytical framework can obtain, as we expect the national component to yield divergent party placement perceptions. We study the perceptions of parties competing in the entire Spain and regional pro-independence parties, and investigate social groups related to national ideological and socioeconomic aspects.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section Linking Social Identity with Party Perceptions reviews previous research and outlines our contribution. Section Group-based Divergence and Perceptual Effects presents the analytical framework. Section Empirical Application provides the empirical application. Section Discussion provides a discussion, and Section Conclusion concludes.

Linking social identity with party perceptions

Understanding how citizens perceive party positions is an important aspect in the study of public opinion and representative democracies. While the literature agrees that citizens differ in their perceptions, it is still an open question how different groups are tied to parties in perceiving and interpreting the political landscape. There is also no consensus among existing studies on how to characterize and interpret this heterogeneity, yielding several notions with different implications. In the following, we review these studies and outline how our analytical framework on social identity theorizing contributes to understanding the link between social groups and political perceptions, which allows for uncovering the direction of perceptual effects toward parties in multiparty systems where citizens may not identify with a single party but with various parties to different degrees.

Some studies characterize heterogeneity in party platform perceptions as perceptual variability across citizens, based on measures of dispersion or concentration (e.g., Dahlberg, Reference Dahlberg2009; Somer-Topcu, Reference Somer-Topcu2015, Reference Somer-Topcu2017). We also understand it as variability but pay specific attention to the direction of such variations (e.g., to the left or the right). Other research refers to disagreement among citizens. When the individual perceptions deviate from some average perception, citizens are said to disagree on where to place parties (e.g., Dahlberg, Reference Dahlberg2013). Misperception is yet another notion linking it to an inability to locate parties accurately, understood as a perceptual bias that hampers political representation (e.g., Aldrich et al.,Reference Aldrich, Schober, Ley and Fernandez2018; Muraoka and Rosas, Reference Muraoka and Rosas2021; Potter and Dunaway, Reference Potter and Dunaway2017). When individuals deviate from expert locations, they are assumed to misperceive the party position. In contrast to these studies, we do not rely on a true or objective party position. Instead, we evaluate whether distinct groups differ in their perceptions to understand the diversity in interpreting politics.

Another prominent notion in the context of spatial voting (e.g., Calvo, Chang and Hellwig, Reference Calvo, Chang and Hellwig2014; Drummond, Reference Drummond2011; Merrill, Grofman and Adams, Reference Merrill, Grofman and Adams2001) is misestimation that comes in two forms: assimilation and contrast. They are projection effects that describe cognitive efforts voters employ to resolve inconsistencies between their ideological self-placements and the placement of the party they support.Footnote 1 Based on vote choices (or voting intentions), voters are grouped into supporters and non-supporters of each party. Assimilation is the tendency to overestimate the ideological similarity to the voted party. Contrast is the tendency to overestimate the ideological distance to non-voted parties. These effects account for the direction of variation but limit it to only two groups: party supporters and non-supporters. We build on the same idea of considering groups of citizens and generalize it to various group identifications that may not manifest in voting for the same party.

Unlike previous contributions, we use the classic notion of social groupings as lenses through which citizens perceive and interpret politics (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Warren Miller and Stokes1960; Conover, Reference Conover1984; Miller, Wlezien and Hildreth, Reference Miller, Wlezien and Hildreth1991), connect perceptual divergence among multiple groups with political parties and incorporate a directional perspective, helping to understand their manifold links. To do so, we draw on the social identity theory, where similarity in perceptions among group members and differences across groups are core theoretical components (e.g., Tajfel et al., Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell1987).Footnote 2

The basic idea is that many social groups have the potential to act as organizing cues that function as anchor points for interpreting the political world and, therefore, coloring party perceptions. We argue that group membership translates into a group identity when different perceptions surround different groups. The perceptual divergence among groups activates the group identity by establishing an affect between specific parties and groups, which can be positive or negative. A positive affect is expressed by pulling a party to the preferred group policy, and a negative affect by pushing away a party, defining what we call ingroup and outgroup effects. This conceptualization allows disentangling the potential of different social groupings to produce such directional effects toward several parties.

By investigating perceptual patterns and group attachments to multiple identity-based (e.g., van Erkel and Turkenburg, Reference van Erkel and Turkenburg2022; Greene, Reference Greene2004; Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes, Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Iyengar and Westwood, Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2018; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021; West and Iyengar, Reference West and Iyengar2022). The rationale of these studies is that individuals identify with a political party, and the identification causes ingroup favoritism and outgroup animosity. The preferred party and its fellows form the ingroup toward which they hold a positive affect; the other parties are the outgroups associated with a negative affect. Citizens are very likely to interpret the political landscape as more diverse than by ideological labels, and partisanship can reflect other group identities related to several socio-political or ideological cleavages, which becomes especially relevant in multiparty systems with coalition governments (see Bankert and Huddy Rosema, Reference Bankert, Bankert, Alexa, Huddy and Rosema2017; Garry, Reference Garry2007; Gonzalez et al., Reference Gonzalez, Manzi, Saiz, Brewer, Tezanos-Pinto, Torres, Aravena and Aldunate2008; Hagevi, Reference Hagevi2015). In such contexts, citizens may not identify with one single party but with various. Depending on the specific group membership, based on cultural, socioeconomic, or ideological labels, these identifications can be conflicting, point in different directions, or differ in degree. We introduce a framework that permits studying the potential of these multiple groups, where ideological labels are one of them, to produce affects toward several parties by investigating perceptual patterns and how they differ across parties and social groups in direction and intensity.

Our approach is embedded in the likeability heuristic by Brady and Sniderman (Reference Brady and Sniderman1985) who propose a “model of attitude attribution explaining how citizens draw an accurate map of politics by relying on their political affects, their likes and dislikes of politically strategic groups” (1061); see also Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock (Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991). The perceived issue positions of a group (party placements in our setting) are deduced as a function of personal beliefs and feelings, where observable individual characteristics determine these beliefs and feelings. Our theory perfectly fits into their model by emphasizing the group affect aspect as a determinant of party placement perceptions. Unlike Brady and Sniderman (Reference Brady and Sniderman1985), we empirically test our framework by identifying which groups are salient and impact political perceptions.Footnote 3

Our framework is based on a cross-sectional observational design, which is very general and straightforward to apply to multiparty settings. It does not impose any restriction on the number of identity-based attributes or competing parties. At the same time, it is parsimonious. It only requires individual self-classifications (or self-reports) in mutually exclusive groups on potentially salient identity attributes and an ideological dimension (or specific policy issues) where the individuals place themselves and the parties, information that standard electoral survey data contains. Thus, the implementation is in line with existing studies on social identities that use standard survey data to categorize individuals along identity-based features (e.g., Egan, Reference Egan2020; Ward and Tavits, Reference Ward and Tavits2019). It does not tap directly into the emotional elements of group attachments but indirectly deduces them from group-based divergences and the direction of the resulting perceptual effects. Earlier work in social psychology simultaneously considered cognitive or evaluative aspects (e.g., commitment and self-esteem, see Stets and Burke, Reference Stets and Burke2000). Our approach follows more recent work that separates these components.Footnote 4 It also cannot establish the direction of the causal relationship between social identity groups and party placement perceptions, as it does not incorporate a temporal (or experimental) dimension. We could argue that group membership shapes the nature of perceptual patterns as many identity categories are impossible or hard to change (e.g., race, gender, ethnicity) or only slowly change (e.g., social class, religion, language). However, other identities might be more easily changed (e.g., ideological preferences) so that reversed or reciprocal causation is reasonable as well. Technically, such causal issues can only be addressed by a panel or experimental design.

Group-based divergence and perceptual effects

The social psychology literature (e.g., Tajfel et al., Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981) coined the term social identity to refer to the individuals’ sense of who they are based on membership in social groups or categories. Our analytical framework operates within the terminology of social identity theory, where the group is the base of identity and not the role as in identity theory. However, we are aware of the significant overlaps and similarities between both theories (see, e.g., Stets and Burke, Reference Stets and Burke2000). The formation of social identities is the result of two processes: self-categorization and social comparison. Self-categorization means that individuals can classify themselves in relation to other social groups. Social comparison produces ingroups and outgroups: individuals categorize others who are similar to them as the ingroup and those who are different as the outgroup. Self-categorization causes accentuation of the perceived similarity to members of the ingroup and the perceived difference to members of the outgroup. Social comparison causes to evaluate the ingroup positively and the outgroup negatively.

In the following, we outline how our framework on group-based perceptual divergence incorporates social identity theorizing into the study of political perceptions. It enables the detection of which social comparisons produce ingroups, outgroups, or neither. The proposed framework does not require coherent groups as a precondition; rather, the empirical modeling strategy detects group coherence.Footnote 5 We draw on the traditional left-right dimension, which is analyzed in the vast majority of existing research (e.g., Aldrich et al., Reference Aldrich, Schober, Ley and Fernandez2018; Dahlberg, Reference Dahlberg2009, Reference Dahlberg2013; Merrill, Grofman and Adams, Reference Merrill, Grofman and Adams2001; Meyer and Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2020; Muraoka and Rosas, Reference Muraoka and Rosas2021; Somer-Topcu, Reference Somer-Topcu2015). However, it can be easily applied and extended to several ideological dimensions or specific issues (e.g., Adams, Merrill III and Grofman, Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005; Mauerer, Thurner and Debus, Reference Mauerer, Thurner and Debus2015; Mauerer and Schneider, Reference Mauerer, Schneider, Debus, Tepe and Sauermann2019).

The mere self-categorization into groups is a necessary but insufficient condition for activating social identities in our conceptualization. The rationale is that group membership translates into a group identity when it systematically structures party perceptions so that there is similarity in perceptions among group members and heterogeneity across groups, which is in line with social identity reasoning: “In general, we find uniformity of perceptions and action among persons when they take on a group-based identity” (Stets and Burke, Reference Stets and Burke2000, 226). Based on pairwise group comparisons, distinct groups and their perceptions act as anchor points to define the perceptual effects. It requires the ingredients we describe next.

Group Membership. Each individual

![]() $ i\in \left\{1,\ldots, n\right\}$

can be characterized by a set of potentially salient group-based attributes, such as gender, religion, or ideological cleavages. On each attribute, the individual self-categorizes itself into one group in relation to other groups. Following the social identity theory, we assume that only categorical attributes permit self-categorization and, thus, can induce group-based perceptual effects.Footnote

6

On each attribute, the groups are mutually exclusive (i.e., self-categorizing in one group implies not being in another group that belongs to the same attribute). However, individuals can have multiple group memberships on many different identity-based features. For example, they can classify themselves as Catholic (attribute: religion), female (attribute: gender), and ideologically Liberal (attribute: ideology).

$ i\in \left\{1,\ldots, n\right\}$

can be characterized by a set of potentially salient group-based attributes, such as gender, religion, or ideological cleavages. On each attribute, the individual self-categorizes itself into one group in relation to other groups. Following the social identity theory, we assume that only categorical attributes permit self-categorization and, thus, can induce group-based perceptual effects.Footnote

6

On each attribute, the groups are mutually exclusive (i.e., self-categorizing in one group implies not being in another group that belongs to the same attribute). However, individuals can have multiple group memberships on many different identity-based features. For example, they can classify themselves as Catholic (attribute: religion), female (attribute: gender), and ideologically Liberal (attribute: ideology).

Pairwise Group Comparisons. Each group

![]() $ g\in \{1,\ldots, G\}$

is compared to a reference group, denoted by

$ g\in \{1,\ldots, G\}$

is compared to a reference group, denoted by

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

. Consider the attribute religion and suppose a simple binary self-categorization yielding two groups: Catholics and non-Catholics. We use the terms group (e.g., Catholics) and reference group (e.g., non-Catholics) to indicate a pair, which helps to highlight the pairwise comparisons aspect of our analytical framework, where distinct groups and their perceptions are the anchor points to define perceptual effects.

$ {g}_{0}$

. Consider the attribute religion and suppose a simple binary self-categorization yielding two groups: Catholics and non-Catholics. We use the terms group (e.g., Catholics) and reference group (e.g., non-Catholics) to indicate a pair, which helps to highlight the pairwise comparisons aspect of our analytical framework, where distinct groups and their perceptions are the anchor points to define perceptual effects.

Group Preferences and Group Party Placement Perceptions. Each group can be characterized by a preferred policy on the left-right scale that acts as an anchor point and is defined by some average preference across group members. Let

![]() ${\overline x_g}$

denote the average preferred policy of group

${\overline x_g}$

denote the average preferred policy of group

![]() $ g$

. Consider a political party that stands for a policy position on the left-right scale. We also take average perceptions as anchor points, where

$ g$

. Consider a political party that stands for a policy position on the left-right scale. We also take average perceptions as anchor points, where

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

and

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

and

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

denote them for group

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

denote them for group

![]() $ g$

and reference group

$ g$

and reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

, respectively.

$ {g}_{0}$

, respectively.

Perceptual Group Divergence. We say there is perceptual group divergence when party placement perceptions differ across groups,

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}\ne {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

. To ascertain perceptual group divergence, we perform multivariate linear regressions. This type of regression is an extension of the standard linear regression that allows studying multiple parties simultaneously.Footnote

7

Let

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}\ne {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

. To ascertain perceptual group divergence, we perform multivariate linear regressions. This type of regression is an extension of the standard linear regression that allows studying multiple parties simultaneously.Footnote

7

Let

![]() $ {y}_{i1},\ldots, {y}_{iq}$

be a

$ {y}_{i1},\ldots, {y}_{iq}$

be a

![]() $ q$

-dimensional vector that contains where individual

$ q$

-dimensional vector that contains where individual

![]() $ i\in \left\{1,\ldots, n\right\}$

perceives each party

$ i\in \left\{1,\ldots, n\right\}$

perceives each party

![]() $ j\in \left\{1,\ldots, q\right\}$

on the left-right scale. The party placement perceptions are a function of multiple group memberships on different attributes

$ j\in \left\{1,\ldots, q\right\}$

on the left-right scale. The party placement perceptions are a function of multiple group memberships on different attributes

$$ E\left[{y}_{ij}\right|g,{\mathbf{z}}_{i}\Big ]={\beta }_{0\left(j\right)}+\sum _{g=1}^{G}\,{\mathbb{I}}_{g}{\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}+{\mathbf{z}}_{i}^{T}{\mathit{\beta }}_{\left(j\right)},$$

$$ E\left[{y}_{ij}\right|g,{\mathbf{z}}_{i}\Big ]={\beta }_{0\left(j\right)}+\sum _{g=1}^{G}\,{\mathbb{I}}_{g}{\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}+{\mathbf{z}}_{i}^{T}{\mathit{\beta }}_{\left(j\right)},$$

where

![]() $ {\beta }_{0\left(j\right)}$

are intercepts,

$ {\beta }_{0\left(j\right)}$

are intercepts,

![]() $ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}$

are group-specific parameters, and the indicator functions

$ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}$

are group-specific parameters, and the indicator functions

![]() $ {\mathbb{I}}_{g}$

define group membership

$ {\mathbb{I}}_{g}$

define group membership

Thus, all group-specific parameters are estimated in one single model that considers all party perceptions simultaneously.Footnote

8

We include continuous attributes, collected in

![]() $ {\bf{z}}_{i}$

, to avoid overestimating group effects. One group serves as the reference group

$ {\bf{z}}_{i}$

, to avoid overestimating group effects. One group serves as the reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

by imposing the restriction

$ {g}_{0}$

by imposing the restriction

![]() $ {\beta }_{{g}_{0}}=0$

for all

$ {\beta }_{{g}_{0}}=0$

for all

![]() $ j$

, and any group can be selected as the reference. The particular selection determines the pairwise group comparisons. Since the parameters

$ j$

, and any group can be selected as the reference. The particular selection determines the pairwise group comparisons. Since the parameters

![]() $ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}$

indicate divergence between group

$ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}$

indicate divergence between group

![]() $ g$

and reference group

$ g$

and reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

in perceiving party

$ {g}_{0}$

in perceiving party

![]() $ j$

, we detect perceptual group divergence when

$ j$

, we detect perceptual group divergence when

![]() $ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}\ne 0$

at conventional significance levels (5 percent or less). The parameter sign indicates the direction of divergence. If

$ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}\ne 0$

at conventional significance levels (5 percent or less). The parameter sign indicates the direction of divergence. If

![]() $ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}\gt 0$

, group

$ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}\gt 0$

, group

![]() $ g$

perceives party

$ g$

perceives party

![]() $ j$

more to the right than reference group

$ j$

more to the right than reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

, implying

$ {g}_{0}$

, implying

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g\left(j\right)}\gt {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}\left(j\right)}$

; if

$ {\overline{y}}_{g\left(j\right)}\gt {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}\left(j\right)}$

; if

![]() $ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}\lt 0$

, group

$ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}\lt 0$

, group

![]() $ g$

perceives the party more to the left than reference group

$ g$

perceives the party more to the left than reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

, i.e.,

$ {g}_{0}$

, i.e.,

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g\left(j\right)}\lt {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}\left(j\right)}$

, ceteris paribus.

$ {\overline{y}}_{g\left(j\right)}\lt {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}\left(j\right)}$

, ceteris paribus.

Perceptual Effects: Ingroup and Outgroup Effects. Once the existence and direction of group-based perceptual divergence is evaluated, the next step is to assess the distances between group preferences and party placement perceptions to determine the perceptual effects. For simplicity, we suppress the party subindex

![]() $ j$

in the following and consider one party only.

$ j$

in the following and consider one party only.

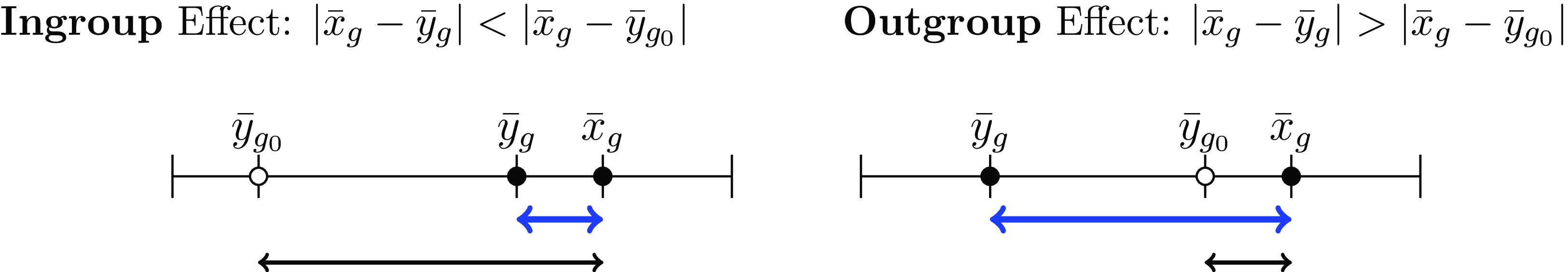

An ingroup effect brings a party closer to the preferred policy of the group. Consider the Catholic versus non-Catholic example again. If the Catholics pull or align the party to their preferred policy, they exhibit an ingroup effect. The left panel in Figure 1 illustrates such an effect. The average group preferred policy

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is closer to the average group party placement

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is closer to the average group party placement

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

than to the average party placement of the reference group

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

than to the average party placement of the reference group

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

. Hence, group

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

. Hence, group

![]() $ g$

exhibits an ingroup effect when

$ g$

exhibits an ingroup effect when

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is closer to

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is closer to

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

than

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

than

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

. Analytically,

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

. Analytically,

![]() $ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|\lt |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|$

, using the arithmetic mean to define the average and the absolute value to measure distance.Footnote

9

$ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|\lt |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|$

, using the arithmetic mean to define the average and the absolute value to measure distance.Footnote

9

Figure 1. Illustration of Ingroup and Outgroup Effects for Group

![]() $ g$

.

$ g$

.

Note:

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is the average preferred policy of group

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is the average preferred policy of group

![]() $ g$

.

$ g$

.

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

and

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

and

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

are the average party placement of group

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

are the average party placement of group

![]() $ g$

and reference group

$ g$

and reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

. Thick arrows give the distance

$ {g}_{0}$

. Thick arrows give the distance

![]() $ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|$

, thin arrows the distance

$ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|$

, thin arrows the distance

![]() $ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|$

.

$ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|$

.

The reversed rationale applies for an outgroup effect. When the Catholic group pushes the party away from its preferred policy, it exhibits an outgroup effect, requiring that the Catholics perceive the party more distant than non-Catholics, as the right panel in Figure 1 illustrates. Here, the preferred average group policy

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is closer to

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is closer to

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

than

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

than

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

. Thus, group

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

. Thus, group

![]() $ g$

exhibits an outgroup effect when

$ g$

exhibits an outgroup effect when

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is more distant to

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is more distant to

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

than

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

than

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

. Analytically,

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

. Analytically,

![]() $ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|\gt |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|$

. In case of equal distance,

$ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|\gt |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|$

. In case of equal distance,

![]() $ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|=|{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|$

, we say that there is neither ingroup nor outgroup effect.

$ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|=|{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|$

, we say that there is neither ingroup nor outgroup effect.

Since the framework is based on pairwise group comparisons, the same logic applies to reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

. The anchor point is then the average preferred policy of the reference group,

$ {g}_{0}$

. The anchor point is then the average preferred policy of the reference group,

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}$

. Thus, when perceptual divergence between two groups is observed, there are two group effects, one for group

$ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}$

. Thus, when perceptual divergence between two groups is observed, there are two group effects, one for group

![]() $ g$

and one for reference group

$ g$

and one for reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

. These effects may not be symmetric; for instance, if Catholics exhibit an ingroup effect, non-Catholics can exhibit as well an ingroup effect if both groups pull the same party to their average preferred policies

$ {g}_{0}$

. These effects may not be symmetric; for instance, if Catholics exhibit an ingroup effect, non-Catholics can exhibit as well an ingroup effect if both groups pull the same party to their average preferred policies

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

and

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

and

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}$

, respectively. Furthermore, the perceptual effects are not mutually exclusive conditions, an assumption that is reasonable in multiparty systems. For example, when Catholics align with a party, this does not necessarily imply that they push away all the remaining parties. In addition, several groups can exhibit ingroup or outgroup effects for the same party. For example, Catholics and females might exhibit ingroup effects for the same party but to different degrees in each case. The framework allows studying such perceptual patterns and how they differ across parties. It also permits pinpointing the groups that produce perceptual polarization, understood as pushing parties to the ideological extremes.

$ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}$

, respectively. Furthermore, the perceptual effects are not mutually exclusive conditions, an assumption that is reasonable in multiparty systems. For example, when Catholics align with a party, this does not necessarily imply that they push away all the remaining parties. In addition, several groups can exhibit ingroup or outgroup effects for the same party. For example, Catholics and females might exhibit ingroup effects for the same party but to different degrees in each case. The framework allows studying such perceptual patterns and how they differ across parties. It also permits pinpointing the groups that produce perceptual polarization, understood as pushing parties to the ideological extremes.

Empirical Application

We apply our analytical framework to the Basque Country to explore how social groupings influence political perceptions and manifest themselves in ingroup and outgroup effects. The Basque Country presents an insightful setting for several reasons. First, it demonstrates the applicability of our approach to multiparty systems, moving beyond the predominantly studied US two-party system. Second, it allows for emphasizing the importance of context in shaping social group formation. A profound divide exists in Basque politics as the Spanish nation struggles to integrate diverse regional cultures within a single country. This feature has defined distinct national groups around the Basque flag in opposition to the Spanish flag (Olivieri, Reference Olivieri2015), and separatist movements in the region have cultivated strong regional identities (Conversi, Reference Conversi1997; Díez Medrano, Dez Medrano, Reference Dez Medrano1995). Third, several other ideological and socioeconomic divisions (along religion, gender, or social class) can also act as social identities that our approach can explore. Thus, many group attributes have the potential to act as social identities by systematically structuring party placement perceptions in the Basque Country.

Since the approval of the 1978 Spanish Constitution, various national and regional parties with considerable ideological variation have competed there. National parties run throughout Spain and oppose the decentralization of power to the Basque Country, whereas regional parties compete in the Basque Country only and are pro-independence. We study the perceptions of three national and two regional parties and consider social groups related to national, ideological, and socioeconomic aspects.

Two divided national identities coexist in the region, Basque and Spanish, supporting different cultures, languages, and symbolism.Footnote 10 Since the Basques aspire further decentralization of power to the region, we hypothesize that they exhibit outgroup effects on national parties, which are against further decentralization, and ingroup effects on regional pro-independence parties. For the Spanish group, we expect the opposite pattern.

The ideological groups we study include Nationalists and Conservatives, among others. Conservatives, in contrast to Nationalists, defend the integrity of Spain. Therefore, we expect large perceptual divergences among these groups, with the Conservatives exhibiting outgroup effects on regional parties while the Nationalists align with these parties.

The socioeconomic groups are based on gender, social class, or Catholic denomination. Given the combined Catholic tradition and incipient secularization of the region (Molina, Reference Molina2011), we expect the Catholics to be a crucial social group in producing perceptual divergence and aligning with historically dominant parties in the region. Next, we describe the data we use to implement the framework and test these hypotheses.

Data

The implementation does not require specific survey item batteries but only self-categorizations (or self-reports) on potentially salient identity features along with party placement perceptions. We use cross-sectional survey data on the four recent Basque regional elections (2020, 2016, 2012, 2009) from the Spanish Center for Sociological Research (CIS); study numbers: 3293, 3154, 2964, 2795. We opt not to pool the data across election cycles to examine whether persistent relationships exist between social identities and placement perceptions.Footnote 11 We base our analysis on roughly 5,000 interviewed citizens distributed across four post-electoral surveys. Drawing on the three types of social groups related to national, ideological, and socioeconomic aspects, we investigate ten pairwise group comparisons and their perceptual effects on five parties, yielding a total of 50 group-by-party perception comparisons. To avoid overestimating group effects, we also consider continuous attributes such as Basque language usage or left-right self-placement.

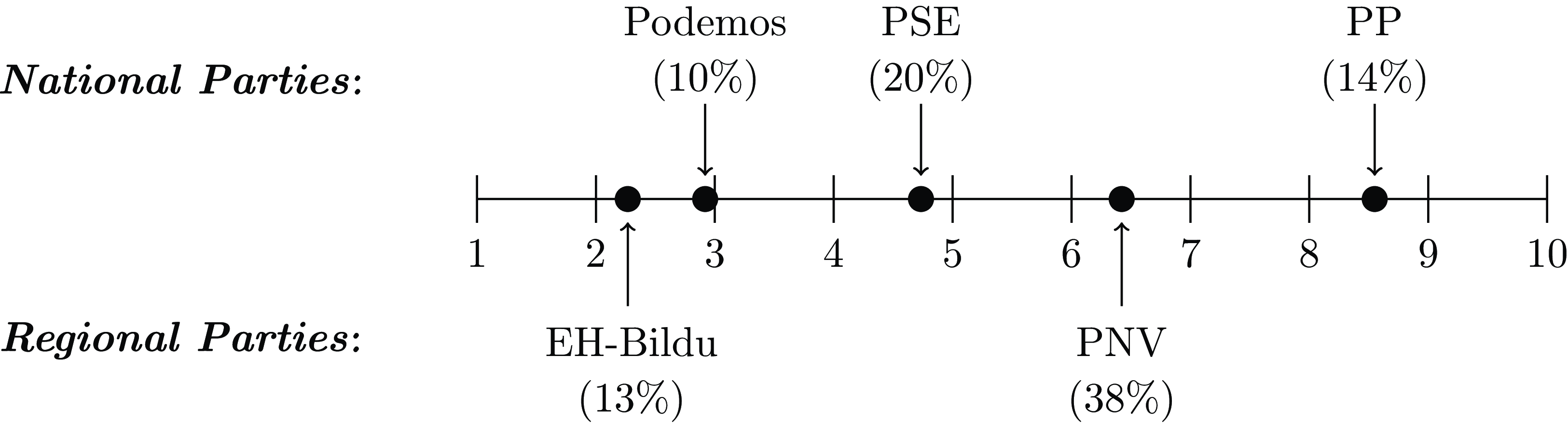

Our dependent variables are individual party placement perceptions on a 10-point left-right scale (1 extreme left, 10 extreme right). We study the parties gaining 95 percent of the votes in the Basque Country over the last two decades: three national parties that compete throughout Spain (social-democratic PSE with an average vote share of 20%, right-wing PP with 14%, and left-wing popular Podemos with 10%) and two regional pro-independence parties running in the Basque Country only (PNV with 38% and EH-Bildu with 13%). The parties show considerable left-right divisions that are stable over time. Figure 2 depicts the mean placement perceptions for the 2020 election (Online Appendix B reports the values for all years). On average, Podemos and EH-Bildu are viewed as left-wing, PP as right-wing, and the two dominant parties in the region, PSE and PNV, as moderate, with PSE tending to the left and PNV to the right.

Figure 2. Mean Party Placement Perceptions, 2020 Election.

Note: Left-right divisions of the political landscape (1 left, 10 right). Average vote shares in parentheses.

As explanatory variables, we study group-based attributes related to national, ideological, and socioeconomic features that individuals self-categorize into.

National Groups. We operationalize national groups by national sentiments, which tap into the subjective aspect of national identities (Ansolabehere and Puy, Reference Ansolabehere and Puy2016, Reference Ansolabehere and Puy2023). Based on self-reports, we establish three groups we label Spanish, Basque, and Neutral. The Spanish group includes respondents who “feel only Spanish” or “feel more Spanish than Basque”. The Basque group consists of respondents who “feel only Basque” or “feel more Basque than Spanish”. The Neutral group comprises those who “feel equally Spanish and Basque”, and serves as the reference group, allowing us to study how Spanish and Basque differ from this group in their perceptions.Footnote 12 Over the last two decades, about 50 percent feel Basque, 10 percent Spanish, and 40 percent feel equally Spanish and Basque.

Ideological Groups. We define ideological groups based on divisions produced by traditional ideological preferences (Abramowitz and Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2006; Bougher, Reference Bougher2017; Devine, Reference Devine2015; Egan, Reference Egan2020; Mason, Reference Mason2018). Drawing on self-categorizations, we consider membership in five main ideological groups: Conservative, Socialist, Feminist/Ecologist, Liberal, and Nationalist.Footnote 13 Across our analysis period, about 20 to 40 percent of the population self-categorizes as Nationalist, 30 to 45 percent as Socialist, and the three remaining categories capture about 10 percent each. The Nationalist group serves as the reference group, providing meaningful comparisons with the other non-Nationalist groups in our empirical context.

Socioeconomic Groups. Many socioeconomic attributes can affect party placement perceptions (e.g., Aldrich.et al., Reference Aldrich, Schober, Ley and Fernandez2018, Bornschier.et al., Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and Colombo2021, Conover, Reference Conover1984, Dahlberg, Reference Dahlberg2013, Helbling. and Jungkunz, Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020, Muraoka. and Rosas, Reference Muraoka and Rosas2021, Westheuser and Zollinger, Reference Westheuser and Zollinger2024). Based on self-reports, we study three socioeconomic groups and their potential to act as social identities: Catholics (reference group: non-Catholic), gender (females, reference group: males), and social class (low, high; reference group: middle). Catholics encompass about 50 percent of the population in the studied period.Footnote 14 The share of females and males is also about 50 percent. The majority reported as belonging to the middle class, a moderate number to the low class, and a small number to the high class.Footnote 15

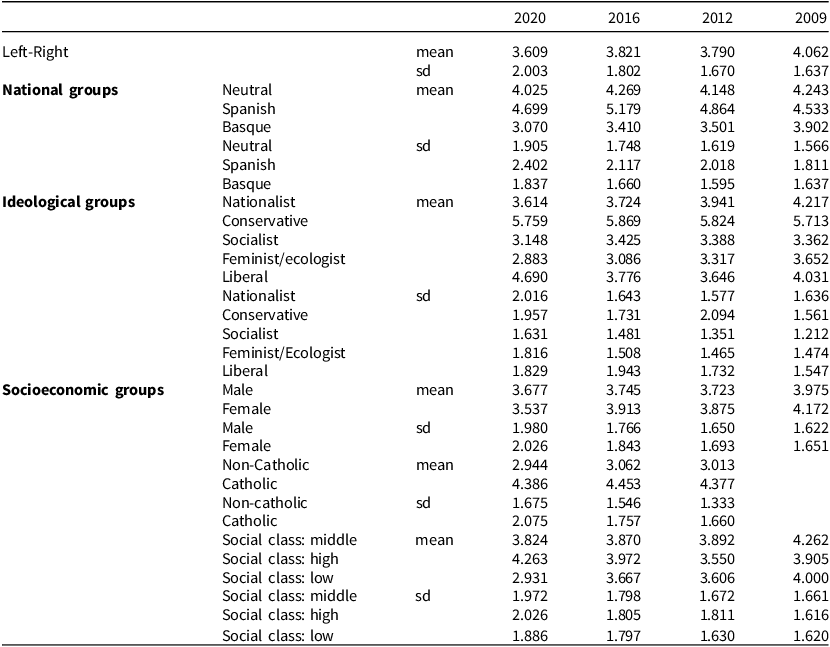

Table 1 reports mean left-right self-placements and standard deviations (as a measure of coherence) by groups. Regarding the national groups, the Basque is the most left-wing (around 3.5), and the Spanish is the most centrist (around 4.8). The corresponding standard deviations, which measure the spread or dispersion, indicate the lowest variability in the self-placements of the Basques and considerably higher variability in those of the Spanish group. Among the ideological groups, the Feminist/Ecologist and Socialist are the most left-wing, followed by the Nationalist and Liberal groups, with the Conservative group reporting more right-wing preferences (close to 6). The spreads around these mean values are very similar, with the Socialists showing the lowest variability. There are almost no differences between males and females. By contrast, Catholics report much more centrist preferences than non-Catholics, whose variability is considerably lower than that of Catholics. We also observe apparent differences between social classes in 2020, with the low social class being more leftist than the middle and high social classes; this difference is not present in the remaining years. The low social class has the smallest spread.

Table 1. Left-right self-placements by groups

Note: 10-point scale (1 extreme left, 10 extreme right). First row gives mean values across all groups, followed by standard deviations (sd). 2020–2009 Basque Regional Elections. We miss information on Catholics in 2009.

In addition to the group-based attributes, we include five continuous attributes to avoid overestimating group effects.

Continuous Attributes. The first is the Basque language usage, which encompasses more of an objective aspect of national identities (e.g., Clots-Figueras and Masella, Reference Clots-Figueras and Masella2013) and is operationalized by an additive index based on reports of understanding, speaking, reading, or writing the regional language Euskera. About 50 percent speak, understand, read, and write Euskera in our analysis period. The second is the left-right self-placement, which is a key explanatory variable in the study of assimilation and contrast effects (e.g., Calvo, Chang and Hellwig, Reference Calvo, Chang and Hellwig2014; Drummond, Reference Drummond2011; Merrill, Grofman and Adams, Reference Merrill, Grofman and Adams2001); measured on the same scale as the party placement perceptions (1 extreme left, 10 extreme right). Finally, we account for divisions along the lines of age, urban-rural location, and the assessment of the economic situation in the Basque Country. The latter helps us to capture economic discontent in the economically strong autonomous community, which constitutes about six percent of the Spanish GDP and occupies the second position in per capita GDP after the community of Madrid.

Empirical results

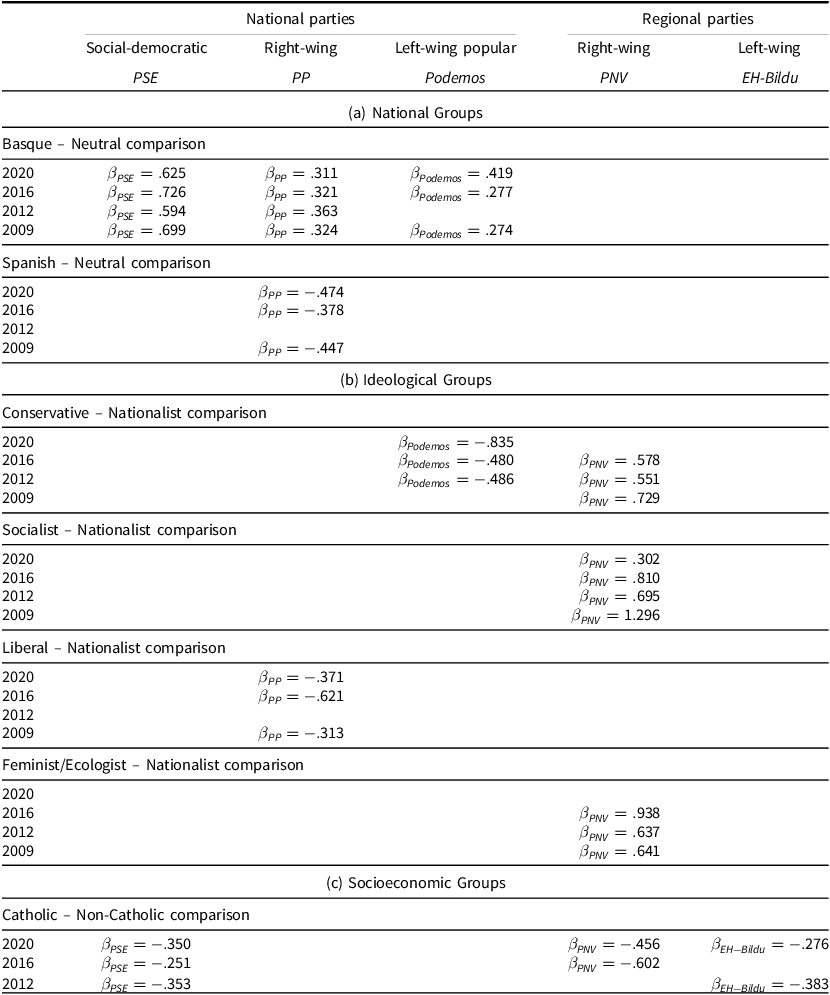

We estimate the multivariate linear regression model in Equation (1) for each election year, which includes five parties, ten group-specific variables, and five continuous attributes. Thus, we simultaneously examine the impact of group-based and continuous attributes on the placement perceptions of all national and regional parties. The results discussion proceeds as follows. For each type of social groups (national, ideological, and socioeconomic), we first present the estimates for perceptual group divergences. Second, we discuss the associated ingroup and outgroup effects. We focus on persistent results, defined by significant estimates (at the 5 percent significance level or less) in three out of four elections.Footnote 16 Online Appendix D reports complete estimation tables.

Perceptual group divergences

We analyze ten pairwise group comparisons and the perception of five parties, yielding 50 group-by-party perception comparisons. Table 2 summarizes the persistent results. The estimates

![]() $ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}$

give the divergence between group

$ {\beta }_{g\left(j\right)}$

give the divergence between group

![]() $ g$

and reference group

$ g$

and reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

in perceiving party

$ {g}_{0}$

in perceiving party

![]() $ j$

based on multivariate linear regressions. Positive (negative) estimates suggest that group

$ j$

based on multivariate linear regressions. Positive (negative) estimates suggest that group

![]() $ g$

perceives party

$ g$

perceives party

![]() $ j$

more to the right (left) than reference group

$ j$

more to the right (left) than reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

, ceteris paribus. The vertical line separates national and regional parties, and subindexes refer to parties only. Panel (a) reports the perceptual divergences for the national groups, panel (b) for the ideological groups, and panel (c) for the socioeconomic groups.

$ {g}_{0}$

, ceteris paribus. The vertical line separates national and regional parties, and subindexes refer to parties only. Panel (a) reports the perceptual divergences for the national groups, panel (b) for the ideological groups, and panel (c) for the socioeconomic groups.

Table 2. Persistent perceptual group divergences

Note: Dependent variables are party placement perceptions on the left-right scale. Entries report multivariate linear regression estimates that are significant in three out of four elections ( p -val.<0.05), except for Catholic denomination (not available for 2009). No persistent divergences for gender and social class. See Online Appendix D for complete estimation tables.

Ten of the 50 group-by-party comparisons belong to the national groups (Basque–Neutral, Spanish–Neutral). Since strong national divisions characterize the Basque Country, we expect substantial perceptual divergences among the national groups. The Basque group favors further decentralizing power to the region, which national parties oppose. The Spanish group favors further centralization of power to the Spanish state, which regional parties oppose. As reported in panel (a), four of the ten group-by-party comparisons are persistent: three for the Basque–Neutral comparison and one for the Spanish–Neutral comparison. All these perceptual divergences are for national parties and none for regional parties. The positive estimates for the Basque–Neutral comparison indicate that the Basques place all three national parties more to the right than the Neutral group, and the largest divergence is observed for the social-democratic PSE. The Spanish–Neutral comparison yields weaker patterns in the opposite direction. The estimates are negative here, and there is only one persistent divergence in the placement of the national right-wing PP. As expected, national groups do structure placement perceptions. However, the results suggest that they only diverge in perceiving national parties that oppose further decentralization of power to the region. In addition, perceptual divergences are primarily observed for the Basques that push all national parties to the right. Thus, it appears the Basque group membership acts as a social identity when it comes to parties that represent the entire Spanish state. By contrast, group membership does not systematically structure how they perceive pro-independence regional parties. Likewise, the Spanish group membership only translates into a group identity when placing the national right-wing PP, which takes the most rigid position against decentralization.

The results for the ideological groups are contained in panel (b). We analyze four group comparisons (Conservative–Nationalist, Socialist–Nationalist, Liberal–Nationalist, Feminist/Ecologist–Nationalist), resulting in twenty group-by-party perception comparisons. We mainly expect perceptual divergences between Conservatives and Nationalists because Conservatives, in contrast to Nationalists, defend the integrity of Spain. Five group-by-party comparisons show persistent perceptual divergences: two for the Conservative–Nationalist, one for the Socialist–Nationalist, one for the Liberal–Nationalist, and one for the Ecologist/Feminist–Nationalist comparisons. The estimates are negative for two national parties (Podemos and PP) and positive for one regional party (PNV). Thus, non-Nationalist groups tend to locate the national parties more to the left and the regional party PNV more to the right than the Nationalists. In line with our expectation, the major ideological division seems to be between Conservatives and Nationalists, for whom we observe large perceptual divergences. The results also suggest that the ideological groups mainly differ in how they perceive the largest party in the region, the pro-independence PNV.

The results for the socioeconomic groups with four pairwise comparisons (between Catholics and non-Catholics, females and males, and three social classes) are reported in panel (c). Thus, we also study twenty group-by-party perception comparisons here. Since a strong Catholic tradition characterizes the Basque Country, we expect particularly the Catholics to be a crucial social group in producing perceptual divergences. Indeed, the results suggest that the Catholics are the only socioeconomic group yielding persistent perceptual divergences, and they do so for three out of five parties: the national social-democratic PSE and both regional parties (PNV, EH-Bildu). As the negative estimates indicate, Catholics perceive these parties as taking more leftist stances than non-Catholics. This finding supports our expectation that religion is a crucial divide in the Basque Country. By contrast, divisions along the lines of gender or social status do not systemically structure party perceptions in the region. Only religion appears to act as a social identity by producing perceptual divergence among the three largest parties in the region.

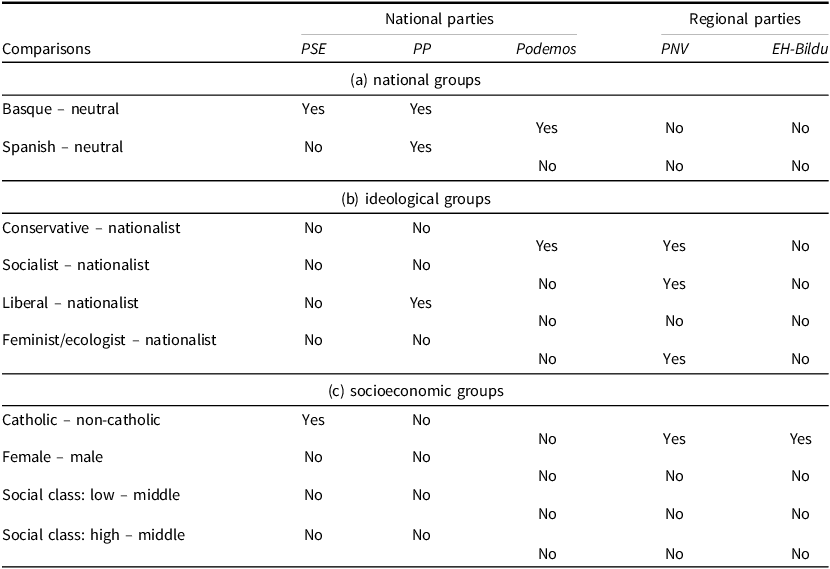

Table 3 completes the results presented in Table 2 by summarizing all comparisons: the obtained perceptual group effects and the null effects. When two groups perceive the parties as divergent in opposed directions, we write “Yes,” meaning that group membership has become a social identity in shaping political perceptions. Otherwise, we write “No,” referring to null effects. It reports that national, ideological, and socioeconomic groups act as identity groups, albeit with some differences. National sentiments structure how individuals interpret national politics. The stronger the Basque sentiment contrasts with those who feel equally Spanish and Basque or more Spanish than Basque, the more the party placement perceptions diverge. The table also shows subtle divergent perceptions among ideological groups; those identifying as Nationalists perceive the regional PNV differently from those with other ideological categories. Finally, socioeconomic characteristics barely manifest as social identity; only religious identification produces distinct perceptions of the regional parties and the Socialist party. Interestingly, social class and gender do not induce distinct perceptions of party placement in the Basque region. These social divides do not structure how citizens interpret the political landscape. While Basques, Socialists, non-Catholics and the low social class show small dispersion in self-placements (see Table 1), which can indicate group coherence, we find that only the first three of these groups exhibit perceptual divergence and social class does not. Thus, group coherence appears to be related to group effects, see (Douglas, Reference Douglas1970).

Table 3. Summary of obtained perceptual group effects and null effects

Note: ‘Yes’ means that multivariate linear regression estimates are significant in at least three out of four elections (p-val.<0.05), or in at least two out of three elections for Catholic denomination (not available for 2009). ‘No’ means that group membership does not structure perceptual divergence among the compared groups. See Online Appendix D for complete estimation tables.

Ingroup and outgroup effects

Next, we discuss ingroup and outgroup effects for the persistent group divergences (reported in Tables 2 and 3) by comparing the distances between group preferences and party placement perceptions. Figure 3 displays for each pairwise comparison the mean group preferences (

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

and

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

and

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}$

) and party placement perceptions (

$ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}$

) and party placement perceptions (

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

and

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

and

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

). Black circles refer to group

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

). Black circles refer to group

![]() $ g$

, white circles to reference group

$ g$

, white circles to reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

. For the sake of illustration, we use the mean values from the 2020 election (Online Appendix B reports values for all years).

$ {g}_{0}$

. For the sake of illustration, we use the mean values from the 2020 election (Online Appendix B reports values for all years).

Figure 3. Ingroup and Outgroup Effects.

Note: Left-right scale (1 left, 10 right). Black circles refer to group

![]() $ g$

, white circles to reference group

$ g$

, white circles to reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

. Mean group self-placements (

$ {g}_{0}$

. Mean group self-placements (

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

and

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

and

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}$

) and mean group party placement perceptions (

$ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}$

) and mean group party placement perceptions (

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

and

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

and

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

).

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

).

Take the Basque–Neutral comparison and the perception of the PSE to see how to read Figure 3. Since the framework is based on pairwise group comparisons, there are two perceptual effects: one for the Basques (group

![]() $ g$

) and one for the Neutrals (reference group

$ g$

) and one for the Neutrals (reference group

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

). Consider first the Basque group

$ {g}_{0}$

). Consider first the Basque group

![]() $ g$

with left-wing preferences (

$ g$

with left-wing preferences (

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}=3.07$

). Combining this group self-placement with the party placements (

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}=3.07$

). Combining this group self-placement with the party placements (

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

and

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

and

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

) and evaluating their distances determines the perceptual effects. The Basques perceive the PSE (

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

) and evaluating their distances determines the perceptual effects. The Basques perceive the PSE (

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}=5.17$

) more to the right than the Neutrals (

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}=5.17$

) more to the right than the Neutrals (

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}=4.33$

). Thus, the Basques exhibit an outgroup effect on the PSE because

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}=4.33$

). Thus, the Basques exhibit an outgroup effect on the PSE because

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is more distant to

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}$

is more distant to

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

than to

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}$

than to

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

, that is,

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}$

, that is,

![]() $ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|\gt |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|$

.

$ |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|\gt |{\overline{x}}_{g}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|$

.

Next, consider the perceptual effect for the Neutrals

![]() $ {g}_{0}$

, who are more centrist (

$ {g}_{0}$

, who are more centrist (

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}=4.03$

) than the Basques. They perceive the PSE closer to them (

$ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}=4.03$

) than the Basques. They perceive the PSE closer to them (

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}=4.33$

) than the Basques do (

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}=4.33$

) than the Basques do (

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}=5.17$

), reflecting an ingroup effect,

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}=5.17$

), reflecting an ingroup effect,

![]() $ |{\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|\lt |{\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|$

.

$ |{\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}-{\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}|\lt |{\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}-{\overline{y}}_{g}|$

.

Panel (a) of Figure 3 visualizes all ingroup and outgroup effects for the national groups. We expect that the Basque group, which favors further decentralization of power to the region, exhibits outgroup effects on national parties, which oppose further decentralization. For the Spanish group, which favors further centralization of power to the Spanish state, we expect ingroup effects on national parties. The Basques push away the two largest national parties (the social-democratic PSE and the right-wing PP), reflecting an outgroup effect. However, the Basques, which are the most left-wing, exhibit an ingroup effect on the national left-wing Podemos by placing the party very close to them. The Spanish group, reporting the most right preferences (close to 5), aligns with the national right-wing PP. The Neutral group shows the reversed effects.

The results fit our expectations to a large extent regarding the Basque group and national parties. National parties have yet to meet the Basques’ aspirations for further decentralization of power to the region, indicated by the Basques pushing away two out of three national parties. By contrast, they do not align with any regional parties but the left-wing popular national party Podemos. It appears that only Podemos and the left parties included under this party label have successfully followed an inclusive strategy toward the regional traditions and culture. Likewise, the Spanish group does not push away any regional parties. It only aligns with the national right-wing PP, which puts the strongest emphasis on the Spanish flag and language symbols among the national parties.

Panel (b) displays the perceptual effects for the ideological groups. The Nationalist group is the reference group for which we expect ingroup effects on the pro-independence regional parties. The Conservatives defend the integrity of the Spanish state and are expected to align with the national parties that represent the entire Spanish state. We observe ingroup effects for the Nationalists (compared to Conservatives or Socialists) and the regional PNV. This result indicates a major schism between Nationalists and the two other major groups, Conservatives and Socialists, in perceiving the region’s largest party, the pro-independence PNV. Nationalists with strong left-wing preferences (

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}=3.61$

) push away the national right-wing PP but align with the national left-wing popular Podemos. The Conservatives (

$ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}=3.61$

) push away the national right-wing PP but align with the national left-wing popular Podemos. The Conservatives (

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}=5.76$

), which report the most right preferences, push away not only the regional pro-independence PNV but also the national left-wing popular Podemos. Similar to the Conservatives, the Socialists with left-wing preferences (

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}=5.76$

), which report the most right preferences, push away not only the regional pro-independence PNV but also the national left-wing popular Podemos. Similar to the Conservatives, the Socialists with left-wing preferences (

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}=3.15$

) exhibit an outgroup effect on the regional PNV, whereas the Liberals with centrist preferences (

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}=3.15$

) exhibit an outgroup effect on the regional PNV, whereas the Liberals with centrist preferences (

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}=4.69$

) show an ingroup effect on the national right-wing PP.

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}=4.69$

) show an ingroup effect on the national right-wing PP.

Finally, panel (c) displays the perceptual effects of the Catholic–non-Catholic comparison, the only one among the socioeconomic groups producing persistent divergences. The Basque Country has a strong and longstanding Catholic tradition. Therefore, we expect that the Catholics align with the historically dominant parties in the region, PSE and PNV. The perceptual effects support this expectation. Catholics, with clear centrist preferences (

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{g}=4.39$

), place PSE close to them (

$ {\overline{x}}_{g}=4.39$

), place PSE close to them (

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{g}=4.45$

), reflecting an ingroup effect. They also perceive PNV closer to them than non-Catholics. These ingroup effects suggest both historically dominant parties succeeded in preserving the Catholic tradition in the Basque Country, whereas the regional extreme-left EH-Bildu did not, which Catholics perceive as even more extreme. By contrast, non-Catholics with way more left-wing preferences (

$ {\overline{y}}_{g}=4.45$

), reflecting an ingroup effect. They also perceive PNV closer to them than non-Catholics. These ingroup effects suggest both historically dominant parties succeeded in preserving the Catholic tradition in the Basque Country, whereas the regional extreme-left EH-Bildu did not, which Catholics perceive as even more extreme. By contrast, non-Catholics with way more left-wing preferences (

![]() $ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}=2.94$

) than Catholics place EH-Bildu (

$ {\overline{x}}_{{g}_{0}}=2.94$

) than Catholics place EH-Bildu (

![]() $ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}=2.39$

) very close to them and push away PNV and PSE.

$ {\overline{y}}_{{g}_{0}}=2.39$

) very close to them and push away PNV and PSE.

For every comparison producing perceptual divergence, all effects are symmetric in our application: the groups forming a comparison never align with the same parties; when a group aligns with a party, the reference group pushes it away (and vice versa), suggesting pronounced perceptual polarization. Inspecting the two extreme parties, the left-wing EH-Bildu and the right-wing PP, we can determine what groups push these parties to the extremes. And once again, it is the Catholics and the Basques. Catholics perceive the regional EH-Bildu as more extreme left-wing, and the Basques perceive the national PP as more extreme right-wing (see Figure 3).Footnote 17

Our approach detects which groups produce perceptual divergence and which do not. Thus, it provides an empirical strategy that tells when social identity theorizing applies to political perceptions and when it does not. We observe various identity groups that systematically produce divergent perceptions, and we can also discard certain groups that do not produce any division. Investigating ten pairwise comparisons (related to national, ideological, and socioeconomic aspects) and five parties over two decades suggests that perceptual divergence is not omnipresent: only a subset of groups differs in perceiving a subset of parties. The results indicate that two attributes are key in forming social identities in the Basque Country: national sentiments and religion. These attributes give rise to divergent perceptions of the most influential parties in the region. Citizens who feel more Basque than Spanish tend to view all national parties as further to the right compared to those who feel equally Basque and Spanish. Additionally, Catholics regard regional parties as more left-leaning than their non-Catholic counterparts. This case study illustrates how the population in the region is divided and how different social groups hold divergent perceptions of the political landscape.

Regarding the continuous attributes (see Online Appendix D for tabled estimation results and coefficient plots), only two of the five variables systematically affect placement perceptions: the Basque language usage and left-right self-placements.Footnote 18 Basque language usage persistently influences how citizens perceive the national party PSE. This result aligns with the findings in Ullan de la Rosa (Reference Ullan de la Rosa2022), who emphasizes that the Euskera language in the region has been used “as a symbolic instrument to construct a differential ideological identity” (234). We operationalize Basque language usage by an additive index, which does not allow for evaluating the presence of perceptual group effects. However, apart from the language aspect, our results show that the Basque national group, defined by national sentiments, is one of the most influential social groupings in shaping party placement perceptions.

Discussion

Our theoretical framework draws on social psychology and its development of the social identity theory (e.g., Tajfel et al., Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981), which is based on aspects of the individual self-concept influenced by socialization. We argue and demonstrate that social identities manifest themselves in ingroup and outgroup effects on party placement perceptions.

Our contribution emphasizes the specific role of context in shaping group identities. The range of social groups to be considered is context-specific. For instance, the distinction between Catholics and non-Catholics in the Basque Country effectively represents religious attributes. However, in contexts where significant portions of the population adhere to various non-Catholic religions, more groups may be necessary to capture the diversity of religious beliefs. Also, society is exposed to certain political or economic events that can trigger new social divisions along the lines of class, race, or other social factors. For example, the Black Lives Matter movement, which emerged in 2013 in the United States, highlighted racial issues, while the EU Migration Crisis brought cultural divisions to the forefront. Our empirical strategy detects whether group membership affects perceptions by assuming the presence of underlying social influence processes, such as sharing information sources or educational backgrounds, which we do not directly address.

The Basque region serves as a valuable case study for illustrating the applicability of our model. It can easily be applied to other contexts, provided there is a preexisting social structure with competing social groups that can be identified through specific survey questions. Our empirical strategy enables the detection of social divides that function as social identity groups by systematically shaping political thinking. We expect active identity groups to be more common in polarized societies; however, our approach systematically uncovers identity groups with divergent perceptions.

Conclusion

We introduced an analytical framework on group-based perceptual divergence that integrates identity-based reasoning into the study of party placement perceptions by conceptualizing two group-based perceptual patterns, ingroup and outgroup effects. These effects reflect the alignment with or distance between group policy preferences and party placement perceptions, thereby accounting for a directional perspective on perceptual divergence. The framework allows uncovering what social groups structure party perceptions, classifies such perceptual divergences into ingroup or outgroup effects, and permits detecting the identity groups that produce the most perceptual polarization. Using standard survey data, it can be applied in multiparty systems and to a wide range of identity-related groups. An empirical application to the Basque region of Spain demonstrates the insights that our approach can obtain. The empirical results show which context-specific social groups act as social identities. Divisions along the lines of national sentiments and religion have produced the most perceptual divergence and polarization, whereas gender or social class do not structure party perceptions in the region.

The framework complements previous research that conceptualizes heterogeneity in perceptions as perceptual variability, disagreement across citizens, or misperceptions (e.g., Aldrich et al., Reference Aldrich, Schober, Ley and Fernandez2018; Dahlberg, Reference Dahlberg2009, Reference Dahlberg2013; Muraoka and Rosas, Reference Muraoka and Rosas2021; Potter and Dunaway, Reference Potter and Dunaway2017; Somer-Topcu, Reference Somer-Topcu2015, Reference Somer-Topcu2017). Unlike these contributions, we do not refer to misperception, perception error, or inaccurate perception. Instead, we argue that identity group membership leads to divergent perceptions. That is, identity-based reasoning modifies how we interpret politics, and we do not define a “correct” perception from which individuals deviate. Our contribution also offers a different and broader perspective than the projection (e.g., Calvo, Chang and Hellwig, Reference Calvo, Chang and Hellwig2014; Drummond, Reference Drummond2011; Merrill, Grofman and Adams, Reference Merrill, Grofman and Adams2001) and affective polarization literature (e.g., Huddy, Mason and Aaroe, Reference Huddy, Mason and Aaroe2015; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2018; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021; West and Iyengar, Reference West and Iyengar2022) by investigating party platform perceptions and considering multiple group characteristics that can produce affects that are not necessarily related to a single preferred party, which is typically the case in multiparty systems (e.g., Bankert, Huddy and Rosema, Reference Bankert, Bankert, Alexa, Huddy and Rosema2017; Garry, Reference Garry2007; Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes, Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012).

Our framework also relates to Brady and Sniderman (Reference Brady and Sniderman1985) who validate two theoretical implications: first, individual characteristics produce affects on groups; second, such affects shape group perceptions. We provide a shortcut to their theory by directly validating whether specific group characteristics shape policy perceptions. Unlike these authors, our framework is grounded in social identity theory, as it emphasizes the presence of social identity groups and offers two key aspects: the directional perspective (ingroup and outgroup effects) and the strength in perceptual divergences.Footnote 19

The obtained results have relevant implications. The study of representative democracy relies on voting decisions, which are often determined by the ideological alignment of voters with the political parties. However, we showed that identitarian factors in divided societies also play a crucial role in shaping party placement perceptions. Traditionally, and starting with Downs (Reference Downs1957), models of electoral competition have not typically incorporated social identity factors, with few recent exceptions (Ansolabehere and Puy, Reference Ansolabehere and Puy2016; Bonomi, Gennaioli and Tabellini, Reference Bonomi, Gennaioli and Tabellini2021; Gennaioli and Tabellini, Reference Gennaioli and Tabellini2024). Our findings suggest that social identity aspects influence the direction of aversion and favoritism toward specific political parties, which is essential for understanding voting behavior. Consequently, electorates are influenced by context-specific social identities, making these identities important considerations when inferring voting decisions, party strategies and electoral campaigns (see, e.g., Lawall et al., Reference Lawall, Turnbull-Dugarte, Foos and Townsley2025).

Our findings suggest avenues for future research. We do not explore the socialization channels through which groups develop shared feelings, preferences, or aversions toward one another. Aspects such as family interactions, peer relationships, education, and media consumption remain to be investigated as potential socialization channels.Footnote 20 Future studies should also move beyond cross-sectional designs. Panel designs allow for temporal and within-individual analysis, while experiments isolate causal mechanisms, which complement regression-based techniques. Hybrid approaches, such as panel experiments, could unpack the complex interplay between social identities and political perception.

Our approach demonstrates that social identities influence how we perceive political parties. We provide evidence showing that heterogeneity in citizens’ identities can lead to feelings of favoritism and hostility, which serve as lenses through which we interpret the political landscape. We believe that further exploring how policy supply adjusts to these differing perceptions is essential for a comprehensive understanding of how identity factors shape election outcomes in modern democracies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773925100234.

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed, the code and documentation for the code are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository: Mauerer and Puy (Reference Mauerer and Socorro Puy2025). Replication data for: Ingroup and outgroup effects on party placement perceptions. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PJBO5S, Harvard Dataverse, Version 1.0.

Acknowledgments

We thank Luis Corchón, Ignacio Ortuno-Ortín, Gerhard Tutz, and Dimitrios Xefteris for their helpful comments. Previous versions of the manuscript were presented at the Multidisciplinary Research Workshop held at the European University Institute (Florence, 2022), the Workshop for Women in Political Economy at the Stockholm School of Economics (Stockholm, 2023), the Simposio de la Asociación Española de Economía-Spanish Economic Association (Salamanca, 2023). We also thank the audience of the workshops and seminars held at the University of Malaga for valuable suggestions.

Funding statement

Ingrid Mauerer acknowledges financial support from the program EMERGIA (EMC21-00256), Junta de Andalucía, and M. Socorro Puy from the project PID2020-114309GB-I00 financed by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Málaga / CBUA.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.