Legalities of the Authorial Name

Perhaps attesting to the global dominance of the myth of proprietary authorship, it is rare to find contemporary print publications that do not bear the name of their authors. Writers have tended to assert their moral right to be identified as authors of their works.Footnote 1 Often foregrounded on the front cover and title page of the book, the authorial name affixed to the text is of evidentiary significance to contemporary copyright systems.Footnote 2 Not only may the authorial name be relied upon as probative proof of literary ownership; it further places the burden of proof on any party seeking to dispute ownership in jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom, Australia and many civil law and European nations.Footnote 3 For instance, section 104(2)(a) of the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988 (‘CDPA 1988)’ provides that the person whose name appears on the publication ‘shall be presumed, until the contrary is proved—to be the author of the work’.Footnote 4 Similarly, article 15(1) of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works 1886 states that the appearance of the author’s name on the literary work ‘in the usual manner’ is sufficient for the author to enforce the protected rights ‘in the absence of proof to the contrary’.Footnote 5 Though no equivalent presumption of authorship operates in the United States and Canada, the authorial name printed in the certificate of registration of copyright issued by their respective copyright and intellectual property offices is similarly presumed to be a valid index of authorship.Footnote 6

Whilst of evidentiary value, the authorial name affixed to the text is neither determinative of the work’s authorship nor a requirement for copyright to subsist in the work. The doctrine of joint authorship, for instance, may be invoked to contest a claim to exclusive authorship.Footnote 7 In the United Kingdom, an unnamed participant in the creation of the literary work may argue that the work is a product of ‘collaboration’Footnote 8 with the named author, in which the former’s contribution ‘is not distinct from that of the other author’,Footnote 9 to qualify for joint authorship under section 10(1) of the CDPA 1988. Kogan v MartinFootnote 10 was a recent case before the Court of Appeal that addressed the question of joint authorship in a screenplay, a text that straddled the literary and dramatic categories of the copyright work. Beyond its doctrinal significance,Footnote 11 Kogan v Martin registers the law’s treatment of the authorial name as a potential screen that obscures the truth of the work’s creation. The claimant, whose name had appeared as the sole screenwriter in all typed versions of the screenplay, had sought a declaration that he was, indeed, the sole author of the work.Footnote 12 Conversely, the defendant, who had been romantically involved with the claimant during the writing of the first three drafts and allegedly made pertinent contributions to their writing that accrued to the final version, made a counterclaim for copyright infringement on the basis of her alleged ownership of a share of the copyright in the screenplay as its joint author. Though the court of first instance ruled in favour of the claimant, the Court of Appeal ordered a retrial of the case on several grounds of error, including the trial judge’s failure to see that the dramatic genre of the work called for a recognition of the defendant’s ‘non-textual input’,Footnote 13 ranging from the inclusion of a song performance to ideas relating to character and plot development, as possibly yielding joint authorship. Subsequently, in the second trial, the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court held that the defendant’s devising of those musical, character and plot elements of the screenplay indeed entailed the ‘creation, selection, and gathering together of concepts and emotions which the words have fixed in writing’Footnote 14 so as to constitute original authorial contributions amounting to one-fifth of the screenplay’s creation. Against the statutory presumption of authorship provided under section 104(2) of the CDPA 1988, Kogan v Martin suggests that copyright law may not trust claims to sole intellectual proprietorship performed by authorial names, but rather seeks to look behind the material façade and assess the actual authorial contributions to the creative process. Notwithstanding the appearance of the claimant’s name in every version of the screenplay and in its various institutional and public forms, both the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court and the Court of Appeal were willing to recognise the possibility of there being an uncredited joint author to whom the work was originally indebted.

Let us add that the absence of specification of the authorial name on the material form of the work does not preclude the subsistence of copyright. Under the doctrine of unknown authorship,Footnote 15 which applies where the authorial identity is not known, the duration of copyright in a literary work takes as its reference point not the year in which the author dies but that in which the work was made or first made available to the public.Footnote 16 As presently provided, the copyright term ends seventy years thereafter.Footnote 17 Where only the publisher’s name appears on the work when it was first published somewhere that qualifies it for copyright protection, the law presumes the publisher to be the copyright owner.Footnote 18 Despite the importance of authors to copyright law as one of the pillars on which its doctrinal edifice stands, the law recognises and provides for situations of authorial anonymity. First an index, then a screen, the authorial name is now shown to be entirely dispensable to contemporary regimes of copyright.

The practice of affixing authorial names to publications, I suggest, has mostly been treated by copyright law and discourse in ways that presuppose, rather than detract from, the myth of proprietary authorship. Where collaboration in the making of works is affirmed (as under the doctrine of joint authorship), it is done only to determine which individuals have been assigned ownership rights on their grounds of their creation of such works. The extent to which the printed authorial name might have materially constituted, even undermined, the proprietary paradigm of literature is left unnoticed and undiscussed. It is as if the authorial name were but one of its inert objects of regulation.

The potential agency of the authorial name, likewise, goes unheeded in literary studies of anonymous and pseudonymous publishing. Authorial anonymity has persisted as a legal possibility in England since at least the latter half of the seventeenth century.Footnote 19 This has led some literary scholars, such as Robert Griffin, to question the apparent priority that Foucault granted to the authorial name.Footnote 20 Foucault’s theorisation of the ‘author-function’ – that is, the role of the authorial figure in discourse – opens by differentiating the author’s name from the proper name, the distinction of which invites a close association of the figure of the author with the author’s name. Whereas the proper name ‘Pierre Dupont’ more simply designates and describes a particular person, the author’s last name ‘Shakespeare’ further classifies a number of texts as being written by that author and him alone, establishing between these texts relationships of ‘homogeneity, filiation, reciprocal explanation, authentification, or of common utilization’.Footnote 21 Against the tendency to equate the authorial name with the authorial figure, Griffin argues that the author-function could just as well operate in anonymous and pseudonymous texts, where the legal name of the author is not printed on the title page.Footnote 22 By the mid-eighteenth century, for instance, it had become commonplace to use the phrase ‘by the author of’ in publications following earlier unattributed works, which just as effectively grouped those texts as a set to be read as written by the same author.Footnote 23 Relatedly, the phrase ‘by a lady’, which was mostly used in Jane Austen’s novels in the early nineteenth century, brought the pertinent texts under the authorship of a particular gender and class, regardless of the actual identities of the authors.Footnote 24 De-linking the author’s name and the author-function allows Griffin to observe the thriving of anonymous publishing during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (despite the commodification of the author’s name),Footnote 25 and certain advantages the practice granted to writers, including those of social and political protection.Footnote 26 He further notes that copyright could subsist in both onymous and anonymous literary publications, which might or might not be held by the authors.Footnote 27

Griffin’s commentary on the history of anonymous publishing in England demonstrates a distrustful and diminishing take on the printed authorial name that eventually coincides with that of copyright law.

The conclusion is inescapable. Naming and copyright protection operate on separate levels of discourse and involve separate decisions on the part of the writer (if indeed the writer is consulted). When copyright historians discuss the author as owner, the author is an abstract legal identity which does not need to have a specific name for it to function in legal discourse.Footnote 28

Whilst at times helpfully indicating the identities of authors as potential first owners of copyright, the printed authorial name is ultimately seen to be an expendable product of commercial publishing that distracts us from the deeper questions of authorship that warrant attention. For the Court of Appeal in Kogan v Martin, it is the potential reality of a second feminine author suppressed beneath the established screenwriter’s name that the copyright doctrine of joint authorship must evolve to uncover. As for Griffin, it is the existence of publishing practices conducted in the absence of the author’s name – or, better yet, in the play of ‘masks’Footnote 29 or ‘faces of anonymity’,Footnote 30 phenomena no less concrete than those surrounding the author’s name – that must now be accounted for in histories of professional authorship.Footnote 31 The author-function may operate without the authorial name, the fact of which potentially contests studies that assume synonymity between them.

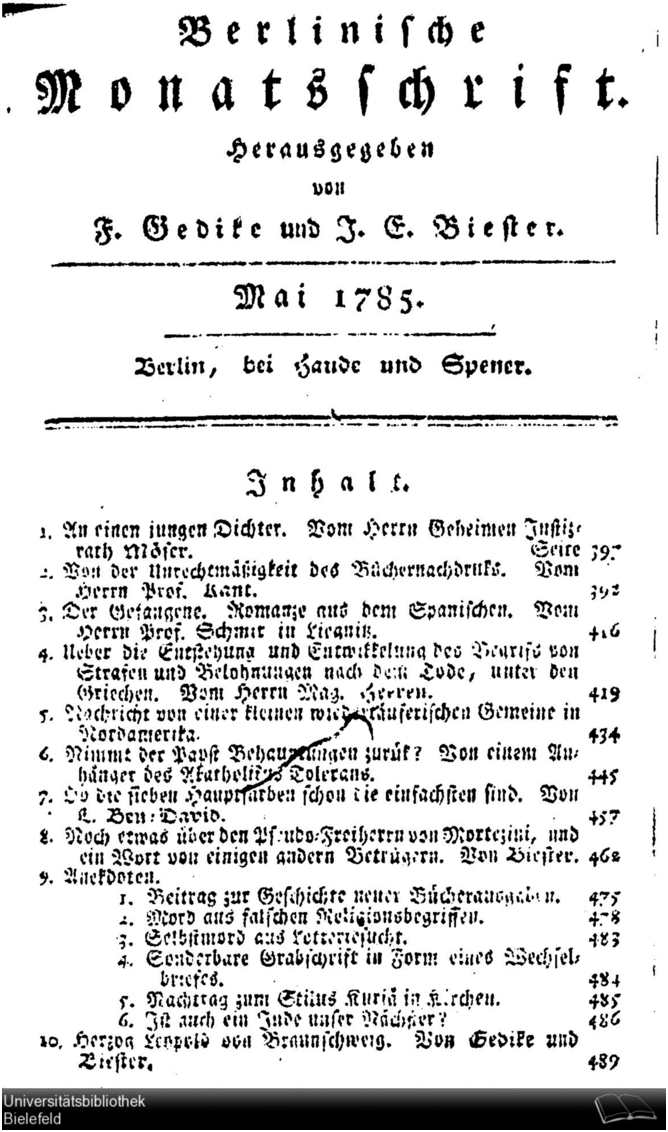

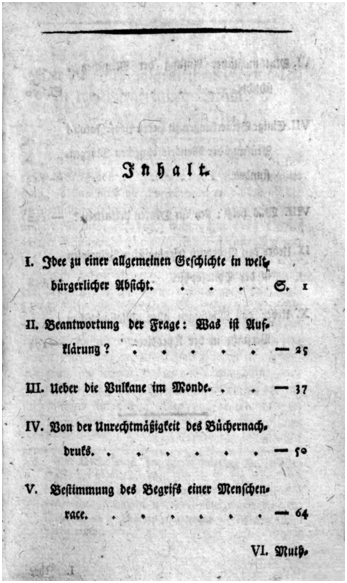

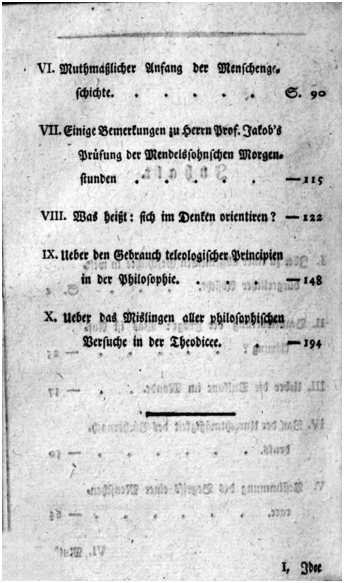

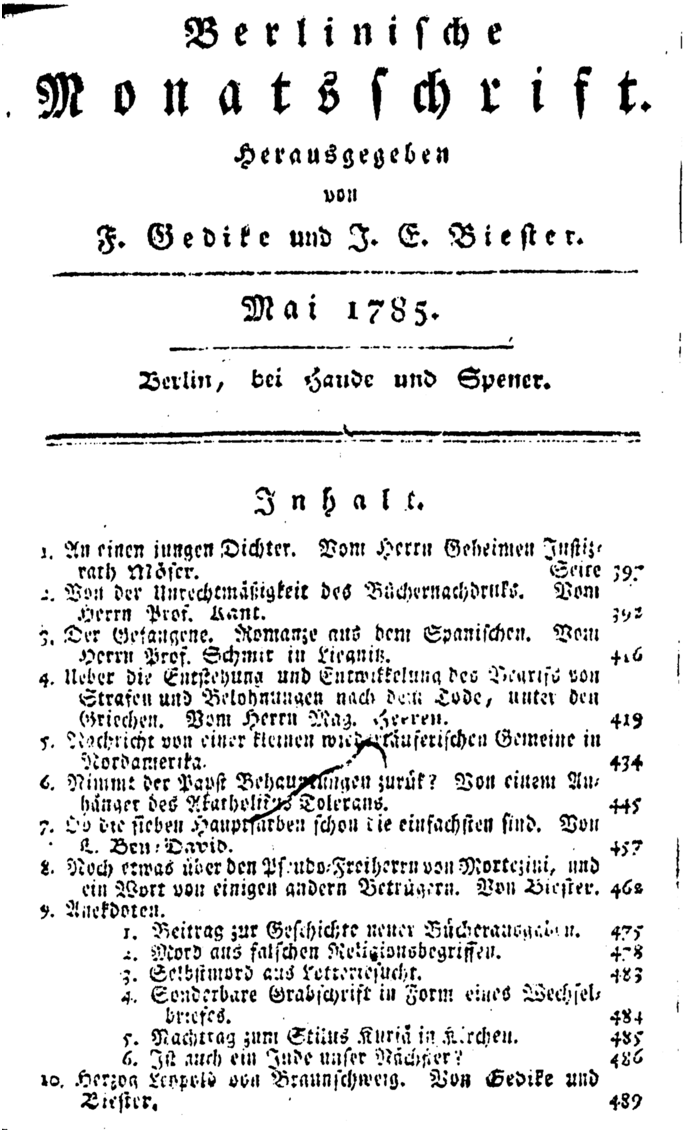

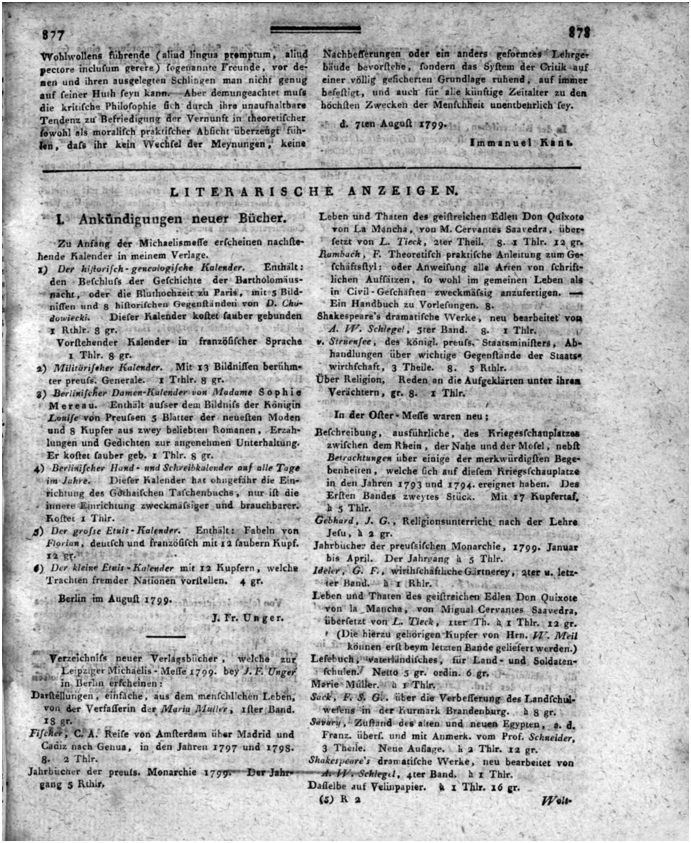

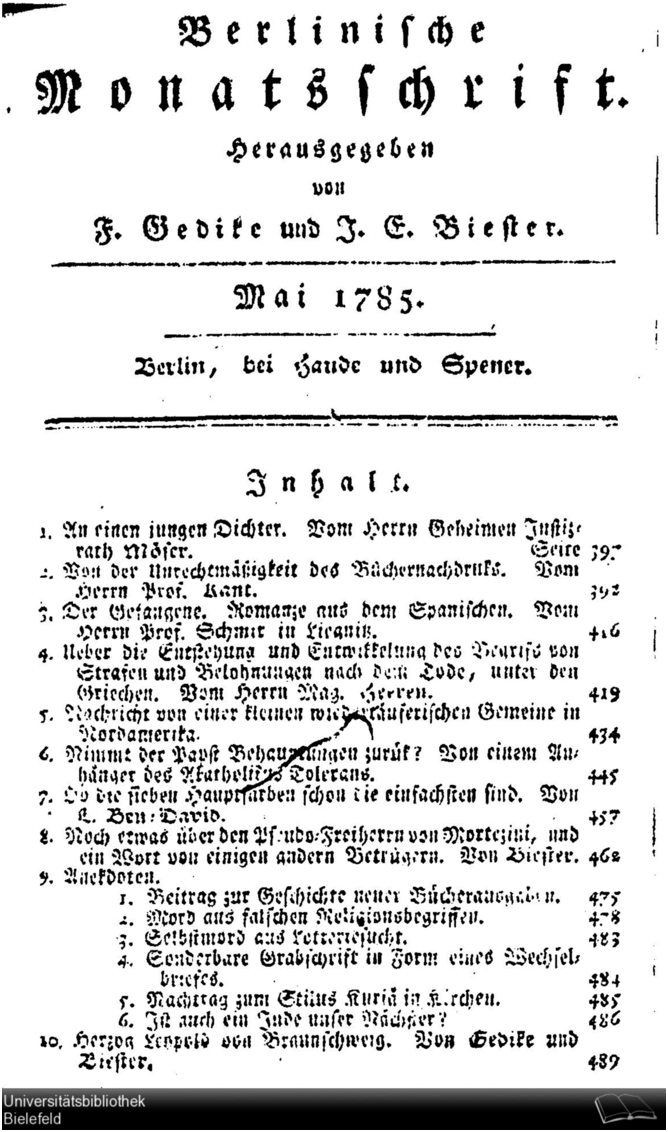

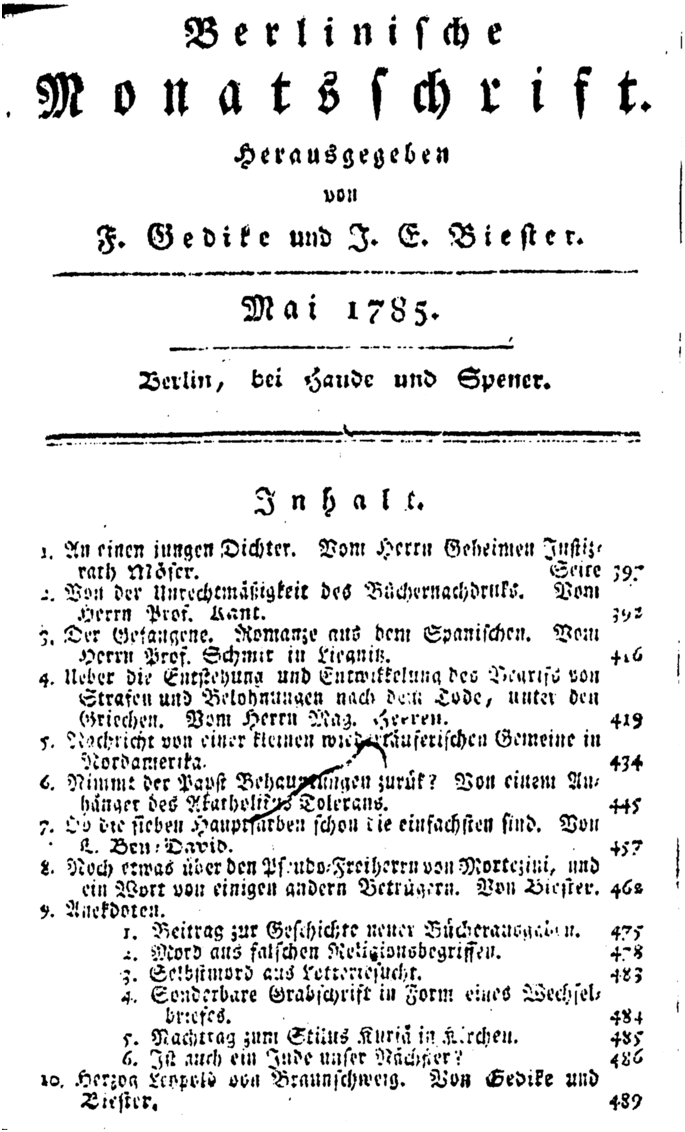

Against the tendency to diminish the authorial name as a material practice involved in the historical (de)constitution of the proprietary author, this chapter seeks to reconstitute the materiality of the authorial name and its implications on authorship in reference to Kant’s 1785 essay in the Berlinische Monatsschrift. My argument is that Kant’s authorial name, ‘I. Kant’, implemented an ethical author-function, one responsive to the demands of enlightenment practice, that well exceeds the perspectives under copyright law and literary studies of anonymous publishing. I begin by revisiting Foucault’s 1969 essay on authorship, attending to both its textual ambiguities and four-part theorisation of the author-function for guidance on approaching Kant’s treatment of the authorial name. Then, I examine Kant’s 1785 essay for what it indicates about the author-function in late eighteenth-century Germany, considering not only the deployment of the authorial name at the rhetorical level of the text but also the textual and typographical (dis)placements of Kant’s name, both within and outside the May 1785 issue of the periodical, and during and beyond the author’s lifetime. In so following the anthumous and posthumous movements of ‘I. Kant’, I chart a biography of Kant’s authorial name that clarifies his interventions as a media theorist and practitioner.

Materialities of the Author-Function

The textual ambiguities surrounding Foucault’s ‘What Is an Author?’ (1969), a work divided into two or more versions, presuppose a literary apparatus not unlike the print machinery that had produced Kant’s 1785 essay.Footnote 32 Despite the apparent ease with which we cite the title and its accompanying date, it is as yet unclear to which text we are, and should be, referring. One of the basic functions of the title is to identify a text.Footnote 33 By naming the text the title works to ‘designate it as precisely as possible and without too much risk of confusion’.Footnote 34 In print publishing, the title usually appears at the time of the publication of the first edition of the text.Footnote 35 With respect to Foucault’s text, it was in 1969 when the original French essay entitled Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur was published in the year’s third issue of the Bulletin de la Société française de Philosophie.Footnote 36 Earlier that year, on 22 February 1969, Foucault had delivered a version of the text as a lecture before the French Society of Philosophy in Paris. The original published essay was later edited, translated into English under the title, ‘What Is an Author?’, and published in a collection of Foucault’s essays, Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews (1977).Footnote 37 By citing the English title and the year of appearance of the original French essay, I purport to refer to the translated text while recognising the original date of its appearance and reserving the possibility of returning to the original text, lecture and their constitutive paratexts as might be helpful.Footnote 38

The situation is complicated by the presence – and, indeed, absence – of other texts against which the identity of our chosen text is defined. Another version of ‘What Is an Author?’, or another translated text that bears the same title, authorial name and other close resemblances to the first, has been published and reprinted in other anthologies. The first known printed collection in which the other text appeared was Textual Strategies: Perspectives in Post-Structuralist Criticism (1979).Footnote 39 Some key differences between the two texts include the second text’s omission of the first’s contextual introduction,Footnote 40 and the inclusion of a new part towards the end of the second text that specified the author’s ideological operation as a ‘principle of thrift in the proliferation of meaning’.Footnote 41 One of the explanations given for this difference in the second text is premised on another talk on the author-function given by Foucault at SUNY Buffalo in March 1970. According to the editor’s preface to Textual Strategies, the second text was his own translation of Foucault’s second talk, the latter of which was identified as a ‘version’Footnote 42 of the first given at the French Society of Philosophy and later published in its bulletin. The translation was not only published with the ‘permission’Footnote 43 of both the author Foucault and the French Society of Philosophy but also edited with an ‘American readership in mind’Footnote 44; the author having given the editor a ‘free hand’Footnote 45 to do so. That the second version of Foucault’s text ends on an apparently more ‘political note’Footnote 46 than the first version is understood by the editor-translator to be indicative of a broader shift in Foucault’s research interests from questions of language to those of history and politics.

Whereas the existence of two published texts does not necessarily impede analysis but could, on the contrary, enable it, the discovery of a third unpublished text still in manuscript form, one that might unsettle prior assumptions and findings, would complicate the matter further. The front matter of Textual Strategies presents the second Foucault text as an edited and translated version of the second talk. This textual identity is co-legitimated by Dits et écrits, probably the leading edition of Foucault’s oeuvre, whose copy of Foucault’s Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur gives an editorial introductory nod to the translated version of ‘What Is an Author?’ in Textual Strategies and its reprint in The Foucault Reader.Footnote 47 Specifically, it is claimed there that Foucault ‘equally authorises’ (autorisa indifféremment)Footnote 48 the first French text and the English translation of what purports to be the Buffalo lecture. Stuart Elden notes that what appears as #69 in Dits et écrits is a composite edition of Foucault’s essay, one consisting of the first French text and some passages purportedly from the original Buffalo lecture.Footnote 49 However, Elden suggests that the second Foucault text in Textual Strategies might in fact have been based on the first lecture delivered in Paris, more so than on the lecture delivered at SUNY Buffalo.Footnote 50 In Elden’s words, ‘what claims to be the Buffalo text was actually something else – essentially a version of the Paris lecture, in a different translation, with some edits and a little of the actual Buffalo lecture appended’.Footnote 51 The insertions in #69 of Dits et écrits are, rather, French translations of the English translated text in Textual Strategies. The ‘actual Buffalo lecture’ or ‘full Buffalo lecture’, as Elden has more recently brought to our attention in November 2021, ‘exists in the archive, and has not been published’.Footnote 52 At least until the original Buffalo lecture has been made publicly available, it would remain unclear whether – and if so, how far – the first and second texts depart from the Buffalo manuscript, and what could be made of these differences.

My interest is not in identifying any ‘true’ nor ‘definitive’ textual expression of Foucault’s ideas on authorship, but in foregrounding the literary machinery behind these textual ambiguities surrounding Foucault’s work. Despite the prevailing juridical emphasis on the author as creator and owner of the original literary work, the literary artefact arises only pursuant to the interactions between multiple actors, including editors, translators, publishers and scholars. In Chapters 2 and 3, we considered the assemblage of print actors, technologies, and practices that produced Kant’s 1785 essay in the Berlinische Monatsschrift periodical.Footnote 53 Kant’s authorial ‘speech’, which presented the printed text as a speech articulated in the author’s name, depended on this very machinery for its presentation before the late eighteenth-century German public. In the instance of Foucault’s 1969 essay, we see in operation a similar literary apparatus on which the making, distribution and reading of the text is materially dependent. The two published versions of ‘What Is an Author?’, not to mention the third unpublished manuscript in the archive and the other ‘original’ French texts, all depend on a plurality of actors, objects and practices for their public appearance. This non-exhaustive series of (con)textual elements, which Genette federated under the abyssal category of the paratext, well exceed the proprietary paradigm of authorship.

Yet, the discourse involving ‘What Is an Author?’ – including my earlier analysis – has continuously sought recourse to the author Foucault as the figure authorising each text that bears the original or translated title, in each instance authenticating the text as written by, or in some other way associated with, the author. My citation of each version of the text doubly depends on its title and the name of the author affixed to it. The relevant editors and translators of Foucault’s essay, particularly those of Textual Strategies and Dits et écrits, cite Foucault as the personal authorial figure who consented to the making of the text at hand, legitimating it as reflecting, or at least originating from, the lectures he had given in Paris and New York. Elden’s careful mapping of the different versions of the text, the appended editorial comments and the inconsistencies between them has proceeded on the basis that there is an original manuscript, the ‘full Buffalo lecture’Footnote 54 in the Foucault archive, against which any claim to textual veracity and accuracy is to be measured. Both the authorial name and the individual person it purportedly designates are summoned, expressly or implicitly, to identify, describe, classify and evaluate the text in each instance.

At play in this discourse is the basic classificatory operation of the authorial figure that Foucault has conceptualised as the author-function. As previously discussed, Foucault’s initial discussion of the author-function proceeded by distinguishing the modern understanding of the authorial name from the proper name. Whereas the proper name conventionally serves to identify and describe some individual, the author’s name goes further to ‘group together a number of texts and thus differentiate them from others’.Footnote 55 This classification also entails the establishing of various relationships between the included texts: in the instance of those different versions of Foucault’s ‘What Is an Author?’, the author is deployed as a figure of ‘authentification’,Footnote 56 inviting them to be accepted as legitimate specimens of the author’s oeuvre, and to be read alongside one another as kindred texts affording ‘reciprocal explanation’.Footnote 57 The third and perhaps most crucial point is that the recognition of there being a particular author to a text, most obviously through the authorial name affixed to it, defines the being (or ‘manner of existence’Footnote 58) of the text and the discourse in which it participates. An essay bearing an authorial name, and Foucault’s canonised name in particular, tends to spare it the fate of cultural oblivion. ‘Discourse that possesses an author’s name is not to be immediately consumed and forgotten; neither is it accorded the momentary attention given to ordinary, fleeting words. Rather, its status and its manner of reception are regulated by the culture in which it circulates.’Footnote 59 Elden’s careful reading of those works bearing Foucault’s name attests to the present endurance of the author-function in the given sense.

Whilst recognising there could be multiple author-functions, or differences in the author-function as it operates in various discourses at any given time, Foucault outlines what he considers to be four of ‘the most obvious and important’Footnote 60 features of the author-function in ‘books or texts with authors’.Footnote 61 In what follows, I review these four features of the author-function, which collectively present an alternative way of approaching the authorial name to copyright doctrine. My suggestion is that Foucault’s second and third suggestions, when considered alongside Chartier’s critical commentary, direct us to the materialities of the author-function, which would guide my subsequent analysis of Kant’s authorial name.

The first aspect of the author-function discussed by Foucault is its historical legalities, specifically its evolved proprietary and penal characteristics. He relates the author-function in modern discourse to the legal-institutional order of Western civilisation, suggesting that the law both reflects and entrenches our modern understanding of authors as owners of property in books. Alluding to the first copyright laws of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Foucault notes that the present status of books as objects of property owned by authors is a result of ‘legal codification … accomplished some years ago’.Footnote 62 Prior to ratifying the myth of the proprietary author, Foucault adds, the law had first inducted the author as a penal subject – one who was ‘subject to punishment … to the extent that his discourse was considered transgressive’.Footnote 63 Though Foucault does not specify a date for this initial penal subjectivation of the author, the English laws providing for the (non-)printing of authorial names suggests that it dates back to at least the mid-sixteenth century.Footnote 64 Foucault’s identification of two historically successive senses of the author reflects his acute recognition of the historicity of the author-function and its co-evolution with law. In copyright history, there have been many incisive responses to Foucault’s call to study the juridical correlate of the author, including key classics of the early 1990s focusing on localities in eighteenth-century Europe, which have in turn attracted their share of critical replies.Footnote 65

The second aspect of the author-function concerns its discursive and historical specificity: ‘it does not operate in a uniform manner in all discourses, at all times, and in any given culture’.Footnote 66 This proposition is, to some extent, continuous with Foucault’s opening suggestion about the historical transformation of the author from a penal subject into an owner of literary property. Whereas the emphasis in the first is on coincidences between the cultural and juridical expressions of authorship, that in the second is on potential divergences in the significance of authors in specific discourses. By way of illustration, Foucault posits a reversal or chiasmus concerning the organisation of so-called scientific texts (‘dealing with cosmology and the heavens, medicine or illness, the natural sciences or geography’Footnote 67) and literary texts (‘stories, folk tales, epics and tragedies’Footnote 68) around the practice of (not) naming the author, which supposedly occurred during the early modern period. According to Foucault, in the Middle Ages, literary texts were disseminated without interest in their authors’ identities, whilst scientific texts required the validation of their authors, whose names had to be therein indicated. However, by early modernity, the two positions had reversed: scientific texts relied instead on impersonal conceptual systems for the validation of their truth-claims, whilst the demand for disclosing the identities of literary authors arose, with each anonymous literary publication becoming ‘a puzzle to be solved’.Footnote 69

Chartier casts doubt on Foucault’s chiasmus of literary and scientific authorship by citing countervailing examples from book history. Contrary to Foucault’s claim of medieval indifference to authorial identities in literary texts, Chartier notes particular strategies adopted by the Parisian rhétoriqueurs (including Jean Molinet, André La Vigne and Pierre Gringore) between 1450 and 1530 to establish their presence as individual owners and controllers of their literary texts.Footnote 70 On top of relying on the limited system of privileges to control the publication and distribution of their books, the Parisian authors had their identities indicated in title pages, colophons and frontispieces, including in the form of a portrait of the author writing the work.Footnote 71 These material methods of authorial self-promotion evidence the operation of the author-function well before early modernity. Foucault’s claim about the impersonality of early modern scientific texts is similarly undermined in Chartier’s reference to the widespread textual practice of dedications to patrons whose superior socio-economic status to some extent assured the credibility of scientific truth-claims.Footnote 72 Consider, for instance, Galileo Galilei’s Sidereus nuncius, whose account of astronomical discoveries, including the Medicean Stars, was dedicated to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo II de’ Medici, celebrating the latter as ‘the primordial inspiration and the first author of the work presented to him’.Footnote 73 Rather than indicating any absence or diminution of the author-function, the dedication reflected its enduring operation by way of transfer to the sovereign as ‘the discoverer and owner of the natural reality’.Footnote 74 The insistence of the author-function across the medieval and early modern periods, with respect to both literary and scientific texts, and as mediated and evidenced by their material forms, would seem to refute Foucault’s historical claim, or at least necessitate further qualification.Footnote 75

Chartier’s attention to the material form of the book and its deep involvement in the author-function attests to both an acceptance and sharpening of Foucault’s third observation about the author-function’s reliance on particular methods and procedures. Foucault understood that the attribution of books to authors did not happen ‘spontaneously’Footnote 76 (that is, without identifiable cause), but instead depended on ‘a series of precise and complex procedures’.Footnote 77 Specifically, Foucault noted that the modern recognition of authors as individuals whose ‘“profundity’ and “creative” power’Footnote 78 gave rise to the literary work is, in fact, an aspect or extension of a contingent textual practice. This individualisation of the author is but one of the ‘projections, in terms always more or less psychological, of our way of handling texts … [which] vary according to the period and the form of discourse concerned’.Footnote 79 In so connecting our understanding of authorship with our textual dealings, Foucault already recognised the essential involvement of books in the author-function. Through his book-historical contributions to the discourse on authorship Chartier goes further to foreground the material form of the book as an index of those textual practices and understandings of authorship. In other words, the author-function is evidenced in the materiality of books – title pages, colophons, front pages, dedications and so forth – by which it operates. Whereas copyright historians tend to focus on the juridical conditions for authorship, Chartier calls attention to the evolving material conditions on which our correlative understandings of the author have been, and continue to be, based.

Despite the historical importance of title pages and other preliminary materials in defining the reception of texts and their connection with authors, these original paratextual matter tend not to be reproduced in contemporary translations and editions of texts. In Chapters 2 and 3, I noted the exclusion of catchwords, signature marks and the various front matter of Kant’s 1785 essay in the Berlinische Monatsschrift from the Cambridge Edition, and on its typographical shift from the Breitkopf Fraktur typeface to the Times New Roman font. Chartier has observed a similar publishing practice in respect of medieval and early modern texts, including the two parts of Cervantes’s Don Quixote, originally entitled El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de La Mancha.Footnote 80 Contemporary French translations of these texts have tended not to reprint their original title pages and other preliminary materials (first published in 1605 and 1615), as if these front matter were inconsequential to our understanding of the work.Footnote 81 Consequent to such exclusions, contemporary readers are separated from some of the key paratextual indices of the author-function as it had operated in the early seventeenth century, including the typographical placement of the authorial name on the original title pages, thereby contributing to the work’s de-historicisation and our limited engagement with the history of authorship.

The fourth and last feature of the author-function noted by Foucault entails a methodological differentiation of the actual person of the author from the author as a product of discourse. On the one hand, there is the writer-in-the-flesh whose actions at a particular place and time contributed to the production of the text. But on the other, there is the discursive author, the meaningful figure of discourse whose conditions of possibility Foucault calls attention to with the term ‘author-function’. Maintaining this distinction allows us to see a ‘variety of egos’,Footnote 82 or plurality of authors, that may arise in a single text. Foucault offers the example of a generic mathematical treatise, where it is possible to find at least three authorial egos attached to its different parts. In the preface, there is the ‘I’ who factually outlines ‘the circumstances of composition’Footnote 83; in the body, we find an ‘I’ performing the pertinent ‘demonstration’Footnote 84; and, perhaps towards the end of the book, there might be a reflective self looking back on ‘the goals of his investigation, the obstacles encountered, its results, and the problems yet to be solved’.Footnote 85 Similarly, Chartier cites the literary example of Don Quixote, in which a reader may find at least four authors.

The ‘authors’ of the novel multiply: there is the ‘I’ of the prologue who announces that the work is his; then there is the author of the first eight chapters who upsets the ‘I-reader’ inscribes in the text when he suddenly interrupts his narration (‘This caused me great annoyance’); there is also the author of the Arabic manuscript; finally, there is the Morisco author of the translation that is the text read by the ‘I-reader’ and by the reader of this novel.Footnote 86

In each of these instances, the ‘author’ is cited as a unifying figure that ensures the integrity of the discourse, even though the dispersion of authors points to the instability of the authorial identity named on the title page – the person of whom copyright law now recognises to be the owner and creator of the literary work.

I have been suggesting alongside Chartier that the history of authorship co-evolves with the history of the book. ‘Such a perspective allows us to understand that the author-function is not only a discursive function, but also a function of the materiality of the text.’Footnote 87 The materialities of the book, including that of the placement of the authorial name on the title page and its other parts, are some of the key conditions through which the author-function operates. As the original 1605 title page of part I of Don Quixote indicates,Footnote 88 the printed authorial name may anticipate the juridical recognition of the author as proprietary creator of the literary work under copyright law. But it may also subvert the myth by directing us to the adjoining historical conditions that are processually constitutive of the book, including the contributions of other print actors and practices relating to the book’s financial support, publication and dissemination. The book itself, and the visual space it presents, is shown to be involved in the configuration and transmission of authorship, mediating its ascription to the author as creator. What the book affords, also, as a material index of the historical conditions and processes of literary production is a de-constitution of the myth of proprietary authorship. In so recording some potential tensions between the juridical and historical accounts of literary production, the authorial name and its analysis paves the way for an alternative mode of dealing with texts that de-prioritises authors, which is a possibility that Foucault suggests to have long been posed in literary modernism and intimated in Beckett’s question, ‘What matter who’s speaking?’Footnote 89

Whilst useful in pointing to the discursive specificity and historical contingency of authorship, Foucault’s differentiation of the discursive author from the authorial person inadvertently screens the transactions between them. The person of the author – that is, the writer who wrote the manuscript to be fed into the print machinery – could well be part of the process that shaped the book and its articulation of authorship. Vice versa, the discursively and materially constituted sense of authorship might likely be involved in the formation of the author’s self-understanding. If the book depends on the person of the author and other agents of literary production for its emergence, then this relationship remains relevant to our understanding of authorship. As a book historian aware of the sociality of texts, Chartier does not exclude the person of the author and other human bodies from his analysis of the materialities of the author-function. For instance, in the chapter after Chartier’s analysis of the prefatory materials of Don Quixote, Cervantes returns as a body engaged in a series of interactions with and within the print machinery of the Spanish Golden Age, including his writing of the autograph manuscript for the printing of the first part of Don Quixote in the print shop of Jean de la Cuesta in 1604, his probable revisions of the fair copy and his introduction of certain modifications into the subsequent textual editions of 1605 and 1608.Footnote 90 Chartier’s point is that early seventeenth-century books such as Don Quixote were not identical to the so-called original autograph manuscripts, but instead were products of a complex publishing apparatus – hence the title ‘Publishing Cervantes’. Not always respected, the writer’s wishes were constantly threatened by the fragility and complexity of the publishing process, including but not limited to editorial interventions. Consistent with Kittler’s observation about the alphabetisation of eighteenth-century German and European authors,Footnote 91 I would suggest that Cervantes probably had to be trained to act like a seventeenth-century Spanish author. This training would have included not only his own alphabetisation but also his induction into the socio-technological systems of print and patronage. It might be that any adequate analysis of the materialities of the author-function would have to take account of the interaction between textual and human bodies. The person of the author, I contend, is far from irrelevant to the author-function.Footnote 92

In the Name of Dignity

Examined at the rhetorical level of Kant’s 1785 essay, the author’s name and related idiom of acting in one’s or another’s name disclose the importance of the personal author to Kant’s argument for the wrongfulness of reprinting. These nominal figures, which drew upon Kant’s secular humanist philosophy and concept of personal dignity, were the basis on which Kant defined and advanced a non-proprietary understanding of enlightenment authorship. Not so much the author-creator of contemporary copyright law bearing exploitable economic rights in their work, it was the dignified human being with an inalienable right in their own person and speech that defined the possessive determiner ‘my’ in Kant’s account of literature.

Kant eschewed the proprietary idiom in his 1785 essay. As discussed in Chapter 3, Kant’s proof opened with a scathing dismissal of the perspective on publishing as involving the exercise of some property right in a text, be it a handwritten manuscript or a print copy.Footnote 93 Not unlike Fichte, Kant did not consider it to be possible for the author to so alienate his thoughts as to give rise to any owned commodity.Footnote 94 Whereas Fichte still deployed the language of property and ownership (in the sense of literary property forever owned by the author whose mind had given form to it) to justify the wrongfulness of reprinting, Kant relied instead on a communicative account of publishing that utilised the rhetoric of names. ‘But I believe there are grounds for regarding publication not as dealing with a commodity in one’s own name [in seinem eigenen Namen], but as carrying on an affair in the name of another [die Führung eines Geschäftes im Namen eines andern], namely the author, and that in this way I can easily and clearly show the wrongfulness of unauthorized publication.’Footnote 95 Kant’s construal of the book as a visual record of speech necessarily spoken in the author’s name was the conceptual basis on which the rights of the legitimate publisher against unauthorised reprinting were vindicated.

The phrases ‘in one’s own name’ and ‘in the name of another’ lent support to Kant’s case for author’s and publisher’s rights through their semantic associations with theological and secular law. As recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary, the expression ‘in –– ‘s name (in the name of ––)’ has been a means of ‘invoking or expressing reliance on or devotion to a divine being’Footnote 96 since at least the early medieval period. The earliest quotation consists of the Trinitarian formula of baptism from the Lindisfarne Gospels, which dates back to the early seventh century: ‘Baptizantes eos in nomine patris et fili et spiritu sancti: fulwuande hia in noma fadores & sunu & halges gastes.’Footnote 97 Relatedly, the phrase has been used as part of ‘solemn adjurations’,Footnote 98 where Christian figures (‘God, Christ, the saints, the Devil or hell’Footnote 99) or else personifications of more secular phenomena (‘mercy’,Footnote 100 ‘goodness’,Footnote 101 ‘Wisdom’Footnote 102) have been called to witness the situation at hand, attesting to its seriousness and importance. Whereas these definitions have relied on divine or abstract figures to authorise the pertinent context or action, the third sense of the phrase that most closely resembles its use in Kant’s essay invokes the authority of human individuals, whether that for whom one is ‘acting as deputy’Footnote 103 or oneself. To act ‘in one’s own name’ is to act ‘on one’s own behalf, independently, without the authority of another’.Footnote 104 Previously dependent on theological figures of authority, the individual is now capable of authorising themselves to act in some manner, and of authorising another to act on their behalf. Notwithstanding such a definitional claim to self-sufficiency and independence, the textual examples given have tended to suppose the existence of some underpinning socio-juridical order that legitimates the said individuals as proper name bearers: ‘To sue an Action of dette in his own name’ (1444)Footnote 105; ‘You who in the name of the rest were Solliciters in this business’ (1631).Footnote 106 Similarly, Kant grounded his agential account of the publisher in what Kant considered to be the properly juridical understanding of the author as a rights-bearing individual ‘with an innate right in his own person’.Footnote 107 From the personhood of the author extended the author’s ‘inalienable right … always himself to speak through anyone else, the right, that is, that no one may deliver the same speech to the public other than in his (the author’s) name’.Footnote 108 Kant noted that with the author’s right in relation to the book came at least three obligations: the author ‘[was] bound as if he were doing it [i.e., publishing the book] himself’Footnote 109; the publisher who had been contractually empowered to relay this speech to the public must fulfil this obligation, even after the author’s death; and the unauthorised printer was barred from reprinting the book, the doing of which wronged both the publisher and author. Thus, a system of rights and obligations surrounding the person of the author purportedly underpinned, structured and ratified Kant’s definition of publishing. By the essay’s conclusion, Kant would align his case against wrongful reprinting with the Roman legal tradition, suggesting that it extended from the latter: ‘If the idea of publication of a book as such, on which this is based, were firmly grasped and (as I flatter myself it could be) elaborated with the requisite eloquence of Roman legal scholarship, complaints against unauthorised publishers could indeed be taken to court without it being necessary first to wait for a new law.’Footnote 110 First semantically authorising Kant’s account, the theological inheritance of naming soon ushered in and subsisted alongside the latter’s secular perspective on print publishing and its involved persons.

Kant’s proposed system of rights and obligations with respect to publishing, which affirmed the personhood and authority of the author, cohered with his preceding account of enlightenment as involving the public use of reason: that is, the exercise of ‘an unrestricted freedom to make use of his own reason and to speak in his own person’Footnote 111 before ‘the entire public of the world of readers’.Footnote 112 As noted in Chapter 1’s review of Kantian copyright scholarship, it is possible to see Kant’s account of author’s and publisher’s rights as the legal arrangement to protect the ‘communicative freedom’Footnote 113 of persons (in late eighteenth-century Germany, and perhaps even today), including both the right to speak publicly and to do so in one’s capacity as a rational being unencumbered by civil or religious duties. The two main examples Kant gave of speakers divided in their capacities as (passive) institutional subjects and (active) rational discussants were those of the clergyman and the citizen.Footnote 114 As employee of the church, the clergyman was bound to instruct his congregation according to the church’s teachings. Similarly, as legal (and, in eighteenth-century Germany, monarchical) subject, the citizen was obligated to obey the prevailing laws. But neither position should prevent the individual from critiquing the doctrines and practices in their capacity as scholar addressing the public by one’s writings. The authority to reason publicly derived from no higher source than the very dignity of the person: the ‘government … finds it profitable to itself to treat the human being, who is now more than a machine, in keeping with his dignity’.Footnote 115 Personal dignity, which in Kant’s moral philosophy was inseparable from the rationality of persons,Footnote 116 acted as the common basis that founded both enlightenment practice and the legal arrangement that secured it. As Barron has suggested, Kant’s proposed regime of rights for publishers and authors promoted the public use of reason by ensuring the continuing willingness of publishers to purchase authorial manuscripts for profitable printing.Footnote 117 Presenting the author as an authoritative figure capable of authorising the public communication of the author’s speech – that is, the printing of a book by which a speech to the public was made ‘simply and solely in the author’s name’Footnote 118 – could be situated within and alongside Kant’s critical humanist philosophy, supporting and deriving support from it. Naming authors as bearers of dignity at the heart of enlightenment practice was the rhetorical strategy by which Kant advanced his account of enlightenment authorship.

Kant qua Media Theorist and Practitioner

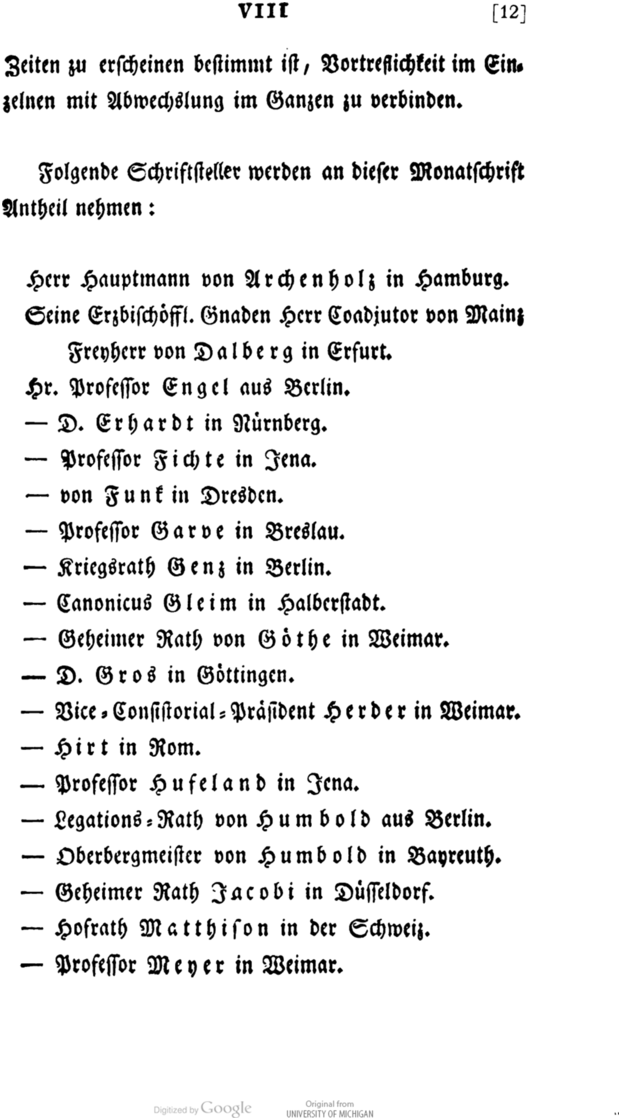

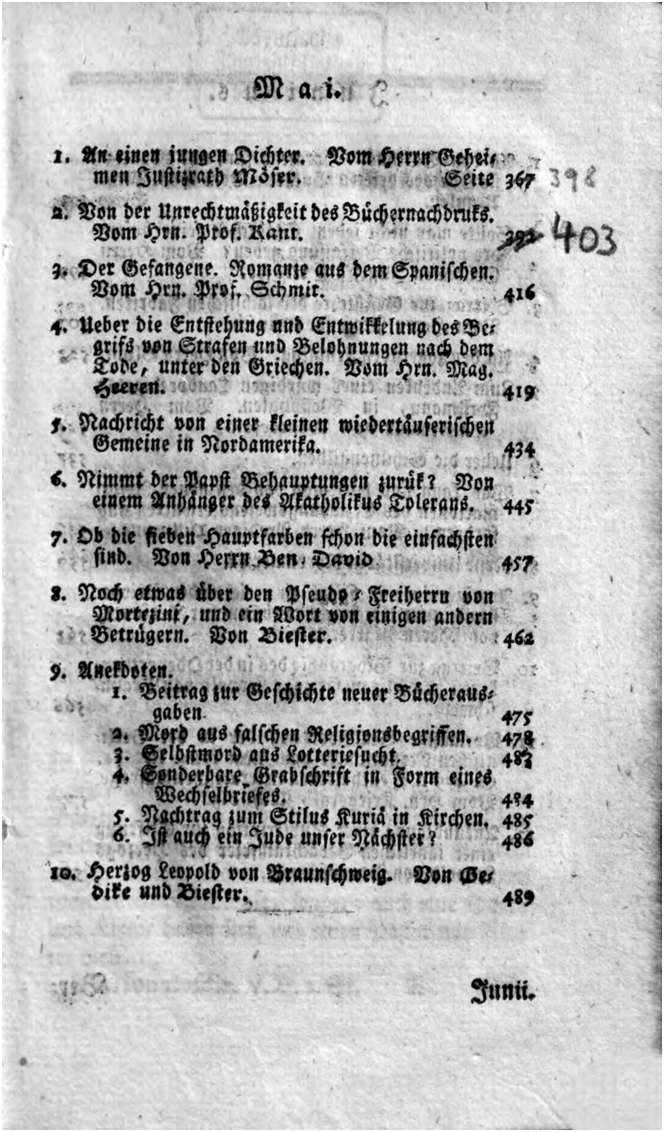

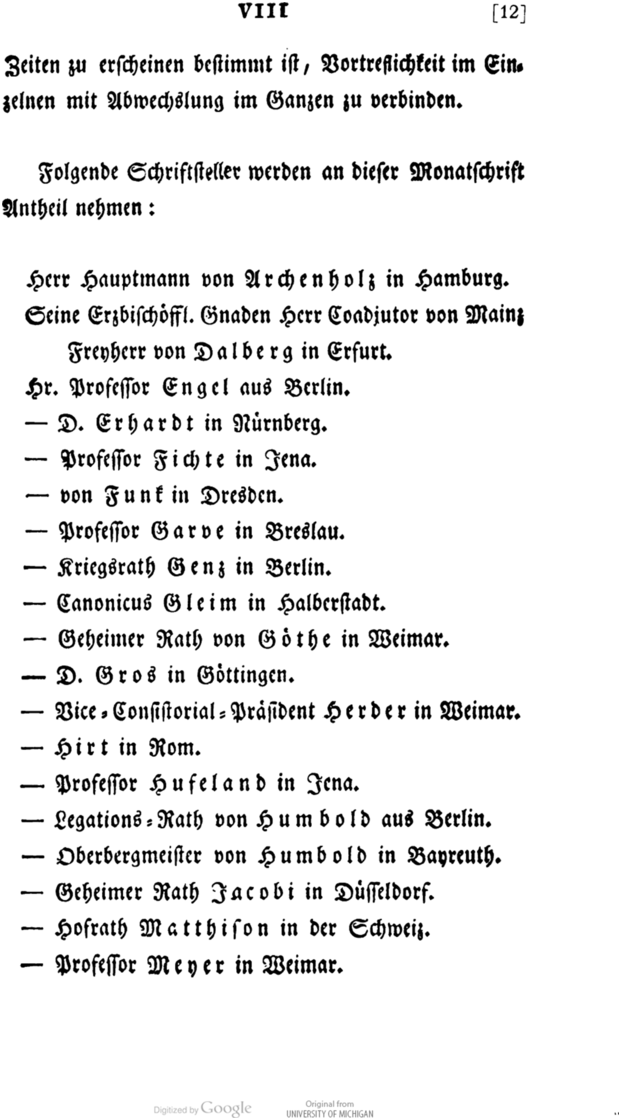

Beyond the rhetorical significance of names in enlightenment authorship, Kant understood the printing of authorial names in publications to be the material basis on which authors could be made responsible for their public speech. It is this idiom of authorial responsibility, I suggest, that distinguishes Kant’s account of authorship from that of copyright law. Kant advocated for onymous publishing: the actual affixing of authorial names to works. In his March 1795 letter to Friedrich Schiller, Kant advised Schiller to disclose the names of the authors who contributed to Die Horen, a newly launched monthly literary magazine edited by the latter.Footnote 119 In an earlier letter enclosed with two issues of the periodical, Schiller had asked Kant to contribute to it.Footnote 120 Instead of printing the authorial name on each piece constitutive of each issue of Die Horen, Schiller released a list of contributors to the periodical in his opening editorial foreword (see Figure 4.1).Footnote 121 Included in the name list was Fichte, who had not only contributed a piece to the first issue of Die Horen but also written to Kant supporting Schiller’s request.Footnote 122 Schiller’s decision to publish individually authored writings as the undifferentiated output of a ‘society’ [Gesellschaft] involved in the making of the periodical cohered with his aim of ‘combining several of the most deserving writers in Germany into one continuous work’.Footnote 123 While politely declining to contribute to the periodical, Kant suggested that the periodical was better off disclosing the authorial identity of each piece on the grounds of promoting individual accountability and meeting the demands of the reading public: ‘I feel that it may harm your magazine not to have the authors sign their names, to make themselves thus responsible for their considered opinions; the reading public is very eager to know who they are.’Footnote 124

Figure 4.1 List of contributors in Schiller’s foreword to the first issue of Die Horen.

In Kant’s 1785 description of the publishing apparatus, the author was identified as the speaker who, though dependent on the publisher and the print machinery, was ultimately responsible for the speech relayed in and by the book. Authorised to relay the speech in the author’s name, the publisher was not responsible for the speech’s content: ‘if he can do something only in another’s name, he carries on this affair in such a way that by it the other is bound as if he were doing it himself’.Footnote 125 Notice that in Kant’s later advice to Schiller, the author was similarly seen to be the personal speaker accountable for the opinions expressed in the periodical. Crucially, Kant identified the practice of having authors affix their names to their respective textual contributions, ‘to have the authors sign their names’,Footnote 126 to be the means by which authors were held responsible for their texts. Indicating the authorial name within the individual text was seen to be the technique by which accountability for the text was ensured. Kant accepted the practice to be a way of enforcing the borders of each text and individualising each contribution as a distinct speech traceable to some authorising person. Well before Foucault and Chartier, Kant understood the authorial name to be the material means of implementing the author-function.

Other than evincing the author’s recognition of the materiality of the author-function, Kant’s letter to Schiller recorded the autographic signing of Kant’s authorial name. To be sure, Foucault did not consider private letters to be material forms organised around the figure of the author: unlike an essay or a book, ‘a private letter may have a signatory, but it does not have an author’.Footnote 127 Yet, it has been a practice for the private correspondence of writers and other intellectuals to be later made public in the form of the printed book, which attests to the fluidity of texts as they migrate between genres, media and forms across time, potentially attracting and executing the author-function. In the case of Kant, it was after the author’s death that his epistolary communications with other participants in the German print machinery and book trade came to be compiled and published as printed books.Footnote 128 The presentation of Kant’s private letters to the public had not been authorised by Kant.Footnote 129 A print translation of Kant’s letter to Schiller may be found in Immanuel Kant: Correspondence (1999), a selection of letters pertinent to philosophy, similarly published in The Cambridge Edition of The Works of Immanuel Kant.Footnote 130 At the bottom of the letter, typographically centred and split into two lines, is the author’s sign-off: ‘Your most devoted, loyal servant / I. Kant’.Footnote 131 In the original letter, Kant’s signature served to identify the letter’s sender through the abbreviated proper name and its handwritten form, whilst also forming part of the sender’s best wishes to the recipient and affirming their friendship.Footnote 132 But Kant’s name also acted as one of the mechanically – and, later, digitally – reproducible forms by which particular texts were included in the author’s oeuvre.

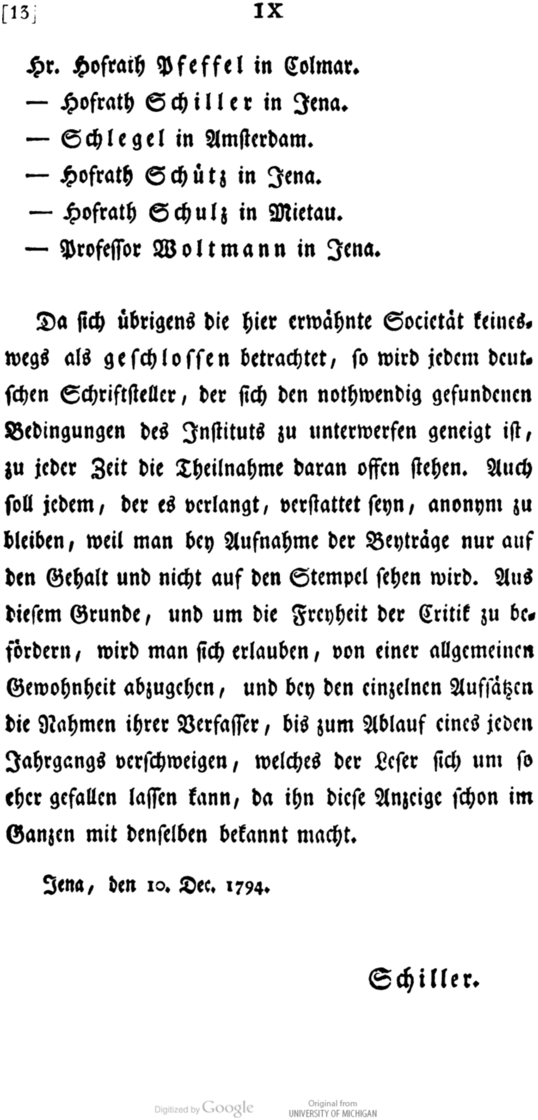

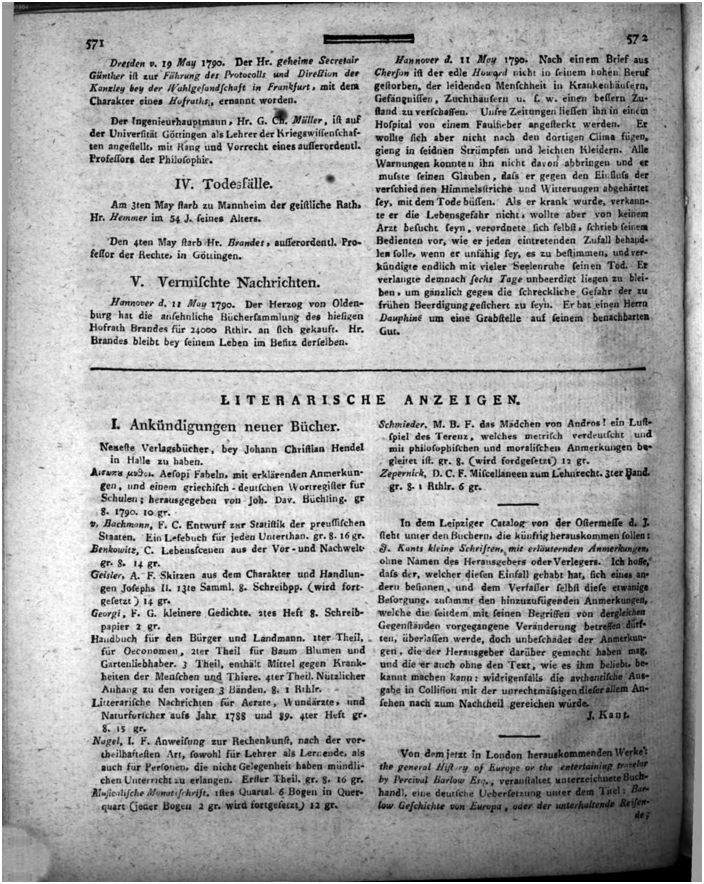

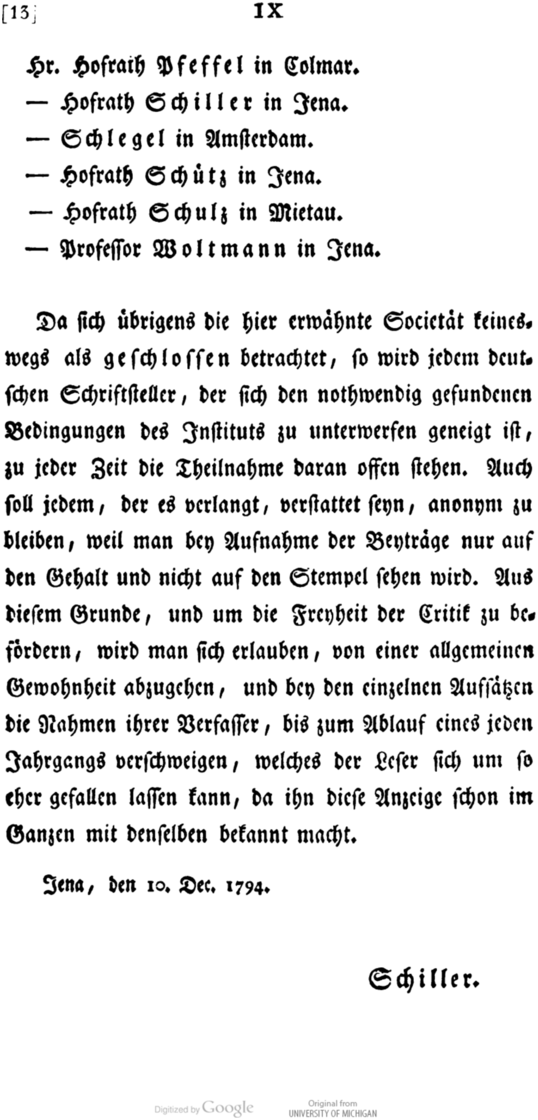

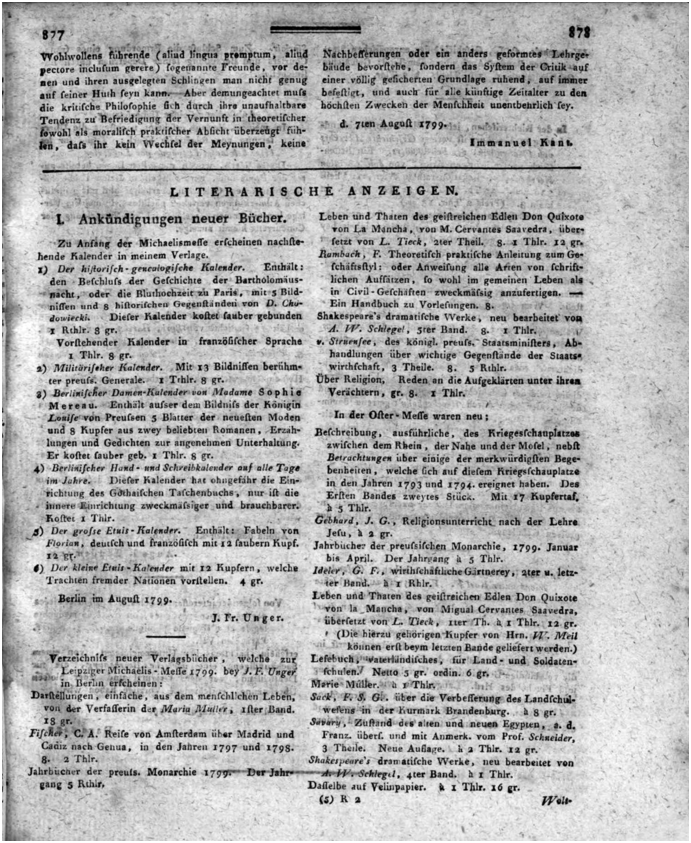

If we return to Kant’s essay as it was originally published in the May 1785 issue of the Berlinische Monatsschrift (and subsequently bound in the fifth volume of the periodical), we shall find that the text concludes with a similar imprint of the author’s name (see Figure 4.2). At the last line of the essay, near the bottom-right of the leaf bearing the page number ‘417’, we find ‘I. Kant’ printed in the same Breitkopf Fraktur typeface in which the essay was set. Notice that both the alphabetical form of the author’s name and its placement at the end of the text are all but identical to those of the letter. Despite the printed format, it is as if Kant had signed the essay. In both instances the author’s name acts to identify the body of text that came before as a distinct record of a speech for which the named author is held accountable. Having received and read the letter signed by Kant, Schiller could write back to Kant and resume the ‘literary discussions’Footnote 133 with which Kant had been ‘delighted’Footnote 134 to engage. Readers of Kant’s essay in the Berlinische Monatsschrift could comment on the argument in some format, whether in a private letter or in some publication like the periodical. For instance, Fichte could claim in a footnote to his own essay to have written it before reading Kant’s and, having read it, to find it ‘very encouraging to find [himself] on the same road as [Kant]’Footnote 135 (even though their arguments substantially differed).Footnote 136 Set in Breitkopf Fraktur, Kant’s signature in the essay underwent depersonalisation in that it was no longer handwritten by the signatory but rather a product of the printing press operated by other workmen. Nonetheless, its newly acquired mechanical reproducibility within and alongside the essay facilitated the essay’s dissemination to the public as a text with a known author.

Figure 4.2 Last page of Kant’s 1785 essay.

In its categorisation of works under a single author, the authorial name ‘I. Kant’ might well have been involved in the propagation of proprietary authorship, both in and beyond Kant’s time. The absence of copyright legislation in Germany until 1837 would not have precluded the existence of the perspective on authors as owners and creators of their works before then.Footnote 137 Though it was in eighteenth-century Britain where the earliest copyright statute arose and the ensuing literary property debate involving London and Scottish booksellers took place,Footnote 138 the contemporaneous circulation in Germany of certain cultural texts that legitimated and rhetorically echoed the British literary property debate suggests that there probably was a ‘transnational flow of ideas in this period’.Footnote 139 Edward Young’s Conjectures on Original Composition in a Letter to the Author of Sir Charles Grandison (1759), whose account of the author as creator, genius and owner of property in their original work has been observed to underpin and anticipate copyright law’s account of the proprietary author.Footnote 140 For Young, authorship was indissociable from genius and ownership: the original work ‘rises spontaneously from the vital root of Genius’,Footnote 141 organically extending from the writer himself; against the backdrop of merely imitative writings, the writer’s original works ‘will stand distinguished; his the sole Property of them; which Property alone can confer the noble title of an Author’.Footnote 142 Young’s work did not receive much attention in England when it was first published in 1759, and so was of little direct influence on the contemporaneous literary property debate.Footnote 143 Nonetheless, Young’s ‘mystification of the author … served the purposes of the ultimate proprietors of copyrights, the booksellers’.Footnote 144 Recognising the nobility of authors as owners of literary property legitimated transfers of title to the booksellers for exploitation in the book trade. Other than supporting the debate’s commodification of literature, Young’s work acceded to the terms of the debate by deploying the property idiom relied upon by both the proponents and opponents of perpetual copyright at common law in the British debate.Footnote 145 As Woodmansee has noted, in contrast to its mild English reception, two translations of Young’s book appeared in Germany within two years of its original publication, which had a ‘profound impact’Footnote 146 on the German debate on the book between 1773 and 1794. Young’s theory of the author as original genius might have shaped Fichte’s view on the author’s mind as that which granted singular form to ideas in the book, such form being inalienable property forever owned by the author.Footnote 147 The criterion of inalienability, or the impossibility of appropriation, distinguishes Fichte’s account of literary property from English accounts that drew on Locke’s possessive individualism. Thus, the understanding of books as original creations of proprietary authors was likely to have been present in some form in late eighteenth-century Germany. The practice of affixing an authorial name to a text, which perceptually groups the text with the named author, may well have perpetuated the myth of proprietary authorship.

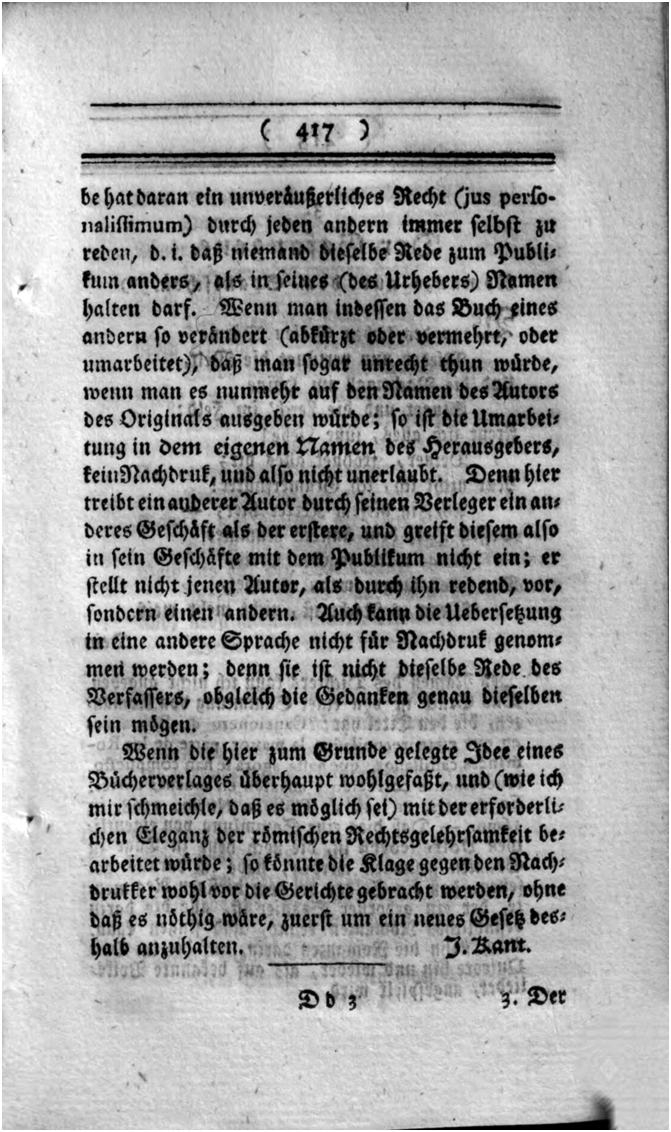

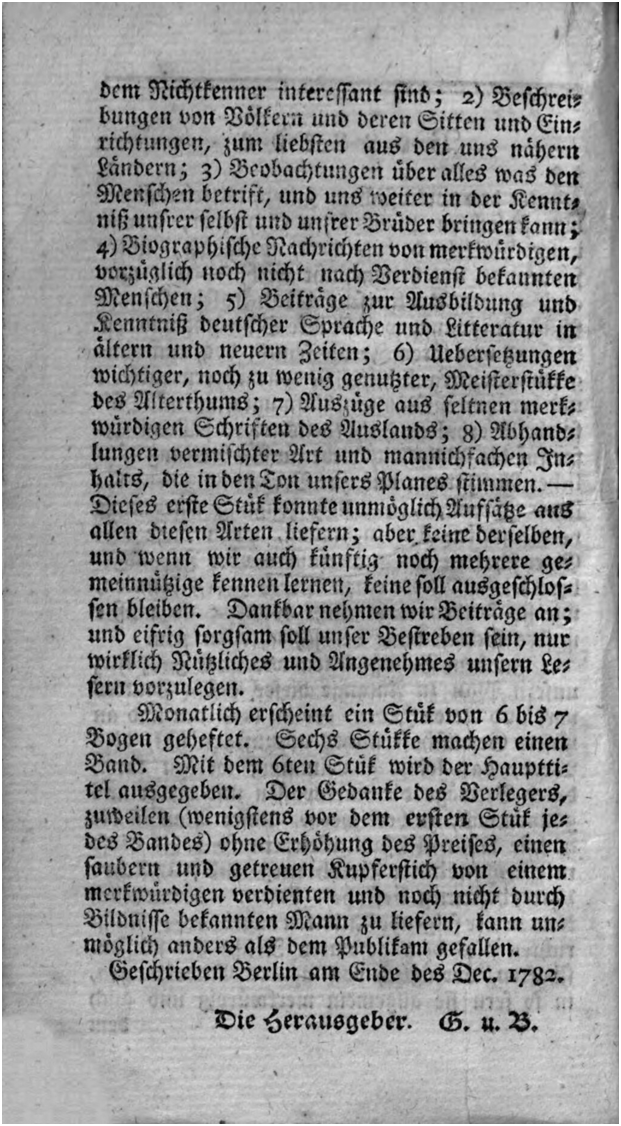

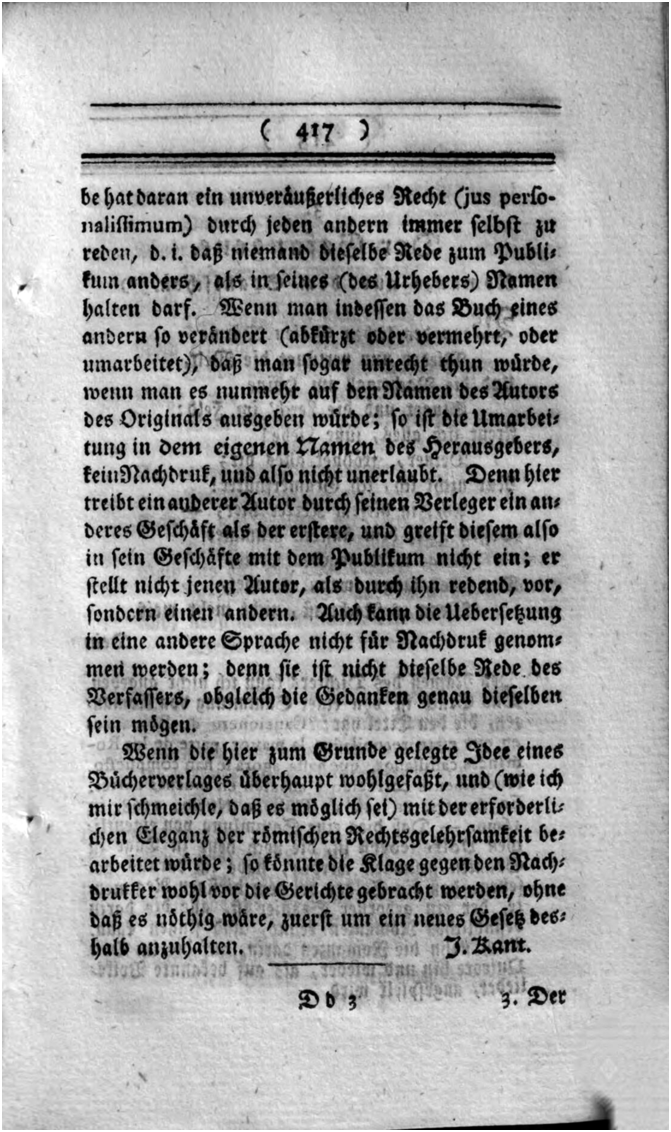

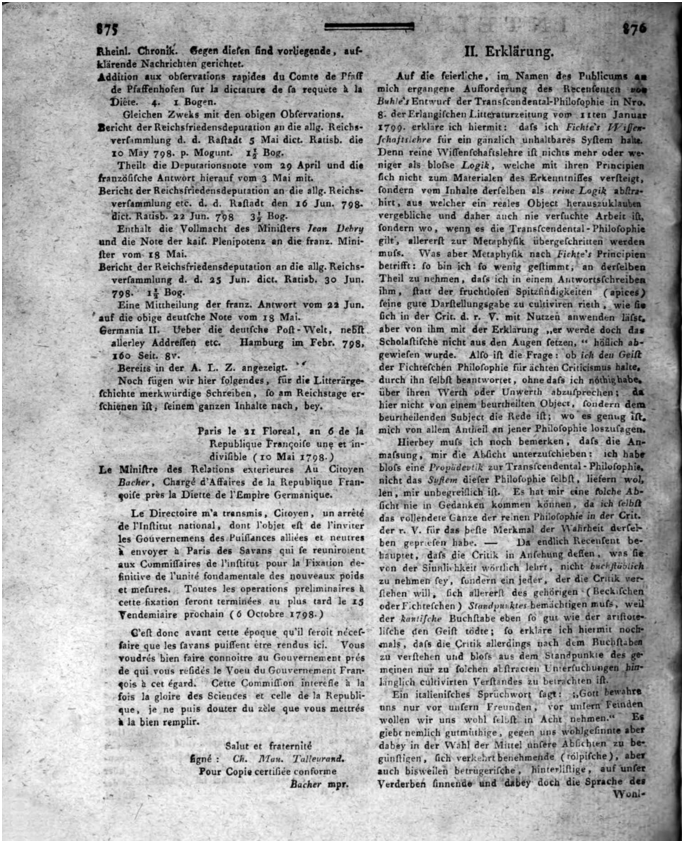

Despite its probable propagation of the proprietary paradigm, the material form and placement of ‘I. Kant’ in the Berlinische Monatsschrift also afforded and supported Kant’s theorisation of the book in non-proprietary terms. Read alongside Kant’s argument, the nominal peritexts in the periodical’s front matter and its contributing texts supported Kant’s ascription of responsibility for the latter to their authors. Included in the title pages of the fifth volume and the May 1785 issue were the names of the editor-publishers, ‘F. Gedike und J. E. Biester’ (see Figures 2.2 and 4.3). Their roles in editing and publishing the periodical was posited and foregrounded in both the title wording, ‘Berlinische / Monatsschrift / herausgegeben / von / F. Gedike und J. E. Biester’, and the preface to each issue. For instance, in the preface to the first issue, Gedike and Biester presented not only their ‘plan’Footnote 148 for the periodical, including the types of contributions pertinent to ‘pleasant instruction and useful enlightenment’Footnote 149 they would ‘gratefully accept’,Footnote 150 but also their projected publishing of six to seven pieces in each monthly issue. Not unlike Kant’s, their names were printed at the end of the text as its speaker, though the line further specified their roles as editor-publishers, ‘Die Herausgeber. G. u. B’ (see Figure 4.4).Footnote 151 Read alongside these other nominal peritexts that assert and disclose the publishers’ identities, ‘I. Kant’ affirmed Kant’s characterisation of the printed book as a speech to the public made by the publisher ‘in the author’s name’.Footnote 152 In other words, the printed authorial name formed part of the material basis for Kant’s communicative account of the book. The book could be imagined as consisting in a reflexive ventriloquy where the puppet-publisher disavowed his responsibility for the authorial speech he transmited precisely because the book bore the names of the two pertinent actors: ‘Through me a writer will by means of letters have you informed of this or that, instruct you, and so forth. I am not responsible for anything, not even for the freedom which the author assumes to speak publicly through me: I am only the medium by which it reaches you.’Footnote 153 With respect to Kant’s 1785 essay, it was by means of the authorial name ‘I. Kant’ printed in the last line of the essay that responsibility for the essay qua speech was attributed to Kant.

Figure 4.3 Title page of the May 1785 issue of the Berlinische Monatsschrift.

Figure 4.4 Last page of the editors’ preface to the first issue of the Berlinische Monatsschrift.

It is my claim that Kant at once understood the medial-materiality of the printed book and insistently anchored it to the two involved persons of publisher and author. For Kant, the book was a visual-corporeal medium that depended on the manifold bodies of texts and humans for its making, distribution and use. Kant’s description of the book as a ‘mute instrument’Footnote 154 composed of ‘letters’,Footnote 155 along with his comments in Der Streit der Fakultäten (‘The Conflict of Faculties’) on typefaces such as Breitkopf Fraktur,Footnote 156 reflected his acute recognition of the book’s opticality and artifice. At the same time, he declined to see it as some autonomous thing whose physical independence marked a space devoid of responsibility. Rather, aided by the convention of printing the names of the publisher and author on the book, Kant identified the publisher as a human ‘medium’ whose control of the publishing apparatus enabled the transmission of another’s speech to the public, and the author as that human speaker accountable for the speech appearing in print. The objecthood of the book was, as it were, accompanied and ultimately circumscribed by the personal figures of the publisher and author and their perceived roles in producing it. Kant was a media theorist who recognised the dependence of authors on the print machinery, but also a humanist who affirmed human freedom and responsibility in his deployment of the authorial name.

Without delving into the personal and reputational reasons behind Kant’s preference for onymous publishing,Footnote 157 let us note that Kant’s attribution of responsibility for books (as printed matter and as speech) to publishers and authors in 1785 cohered with his epitextual observations about the burgeoning book trade and the ethics of authorship and publishing in the German Enlightenment. As discussed in Chapter 2, the phenomenon of print proliferation in eighteenth-century Germany, indexed in the catalogues of the Leipzig and Frankfurt book fairs and other quantitative records, gave rise to considerable anxiety amongst scholars and writers. In 1794 and 1795, the practices of indiscriminate reading and trifling chatter about books were condemned by critics as facets of a ‘reading addiction’Footnote 158 and ‘the plague of German literature’.Footnote 159 In the transcripts of Kant’s Vorlesungen über Philosophische Enzyklopädie (‘Lectures on the Philosophical Encyclopaedia) given sometime between 1767 and 1782,Footnote 160 Kant himself had described the reading public’s excessive reading habits as a pathology, Belesenheit, a condition of overexposure to print without the requisite ability to separate the wheat from the chaff.Footnote 161 Accordingly, a book was first characterised as a threat to individual autonomy and the emancipatory practice of enlightenment in Kant’s 1784 essay: ‘If I have a book that understands for me, a spiritual advisor who has a conscience for, a spiritual advisor who has a conscience for me, a doctor who decides upon a regimen for me, and so forth, I need not trouble myself at all.’Footnote 162 For Kant, the surfeit of books, ceaselessly produced by the print machinery of the eighteenth century, was overwhelming the human being and preventing the use of one’s own understanding to emerge from immaturity.

No less than authors who uncritically contributed to the clutter, publishers who financed and directed the assembly of books more for reasons of profit than for public enlightenment were censured by Kant. Unlike Kant’s correspondence with Schiller, Kant’s two letters addressed to Friedrich Nicolai entitled Über die Buchmacherei (‘On Turning Out Books’) (1798) were open letters made for the public’s reading, first published as a pamphlet in Königsberg and then as part of a collection of Kant’s shorter works in Leipzig and Jena in the same year.Footnote 163 As specified in the opening line identifying the addressee, each letter targeted one of two roles Nicolai played in the print machinery: the first reads, ‘To Mr. Friedrich Nicolai, the author’; the second, ‘To Mr. Friedrich Nicolai, the publisher’. With respect to the first, the very nomination of Nicolai as author might well have been derisive, for it was instead a text bearing Justus Möser’s authorial name that occasioned Kant’s reply. Möser was a German jurist and writer who contributed the letter to a young poet that immediately preceded Kant’s 1785 essay in the same periodical issue (see Figure 2.1). In 1796, two years after Möser’s death, the fragment Über Theorie und Praxis (‘On Theory and Praxis’) appeared in a posthumous collection of Möser’s writings published by Nicholai.Footnote 164 Alluding in its title to another of Kant’s essays first published in the Berlinische Monatsschrift, Über den Gemeinspruch: Das mag in der Theorie richtig sein, taugt aber nicht für die Praxis (‘On the Common Saying: That May Be True in Theory, but It Is of No Use in Practice’) (1793),Footnote 165 Möser’s fragment opposed Kant’s trenchant critique of hereditary nobility. Whereas Kant had argued in the essay that no people would freely agree to be ruled by higher fellow subjects with inherited prerogatives (‘the hereditary privilege of ruling rank’Footnote 166), Möser wrote a fictional counternarrative where persons consented to serfdom to meet their practical needs.Footnote 167 In the letter, Kant reasserted the primacy of reason as the faculty and principle that governed the question of which political arrangement people ought to agree to over and above any pragmatic or other empirical consideration.

For this whole problem is to be judged (in the Metaphysical First Principles of the Doctrine of Right, p. 192), as a question belonging to the doctrine of right: whether the sovereign is entitled to found a middle estate between itself and the remaining citizens of the state; and hence the verdict is then that the people will not and cannot rationally resolve on such a subordinate authority, because otherwise it would be subject to the whims and crotchets of a subject that itself needs to be governed, which contradicts itself.Footnote 168

After having ‘parodied into ridicule’Footnote 169 Möser’s counternarrative, Kant concluded by returning to Nicolai as the individual most implicated by his critique. ‘Mr Friedrich Nicolai, therefore, has come to misfortune with his interpretation and defense in the alleged concern of another (namely, Möser)’.Footnote 170 By using the adjective ‘alleged’ to describe Möser’s fragment, Kant casted doubt on the authenticity of its authorship, suggesting that Nicolai himself might have written or substantially rewritten it while misattributing it to his late friend. Kant noted in the beginning of the letter the ambiguous origins of the fragment, it having been ‘communicated to the latter [Mr. Nicolai] in manuscript, and as Mr. Nicolai assumed that Möser himself would have communicated it if he had brought it entirely to an end’.Footnote 171

Read alongside these comments implicating Nicolai despite the letter’s focus on the fragment bearing Möser’s name, Kant’s identification of Nicolai as author in the addressee line could be Kant’s way of making the latter accountable for a speech made in Möser’s name, but in fact was simply his own. For Kant, the printed authorial name had been misused by Nicolai to disavow himself of responsibility for the text, and was now redeployed by Kant to hold Nicolai to account before the reading public. The nomination may also be understood as Kant’s negative appraisal of Nicolai’s authorship to be merely derivative or imitative. Not only was Nicolai’s ‘completion’ of Möser’s work poor in the weakness of its argument, but Nicolai also proved incapable or afraid of exercising his own reason to produce any scholarly contribution to public enlightenment. His ‘interpretation and defense’Footnote 172 of Möser was more a cowardly act of mimicry than a scholar’s use of reason. In the terms of Kant’s enlightenment essay, Nicolai remained mired in a ‘self-incurred’Footnote 173 state of immaturity, defined by a ‘lack in resolution and courage to use [his own understanding] without direction from another’.Footnote 174 Under this latter reading, ‘author’ was deployed ironically to disclose and deride the insufficiency of Nicolai’s contribution. In both instances, regardless of any personal feud Kant might have had with Nicolai,Footnote 175 the printed authorial name was understood by Kant to be materially connected to the assumption and attribution of scholarly responsibility in the practice of enlightenment.

Whereas the first letter dealt with the poverty of Nicolai’s authorship, the second dwelt on the profitability of literary publishing that Nicolai had, on Kant’s view, prioritised over other societal gains. A neat distinction on which Kant relied to criticise Nicolai’s commercialism and at the same time clarify the ethics of publishing was that between ‘prudence in publication’Footnote 176 and ‘soundness of publication’.Footnote 177 A ‘self-seeking’Footnote 178 publisher such as Nicolai pandered to and shaped the ‘market’Footnote 179 and ‘fashion’Footnote 180 of the book trade without regard for the ‘inner worth and content of the commodities he publishes’.Footnote 181 As a result, the reading public was allowed to remain ‘deceived’Footnote 182 and blind to the importance of theoretical works that sought to clarify and demonstrate ‘judgements of reason’.Footnote 183 For Kant, it was instead the publication of ‘labors in the sciences which [were] all the more serious and well-grounded’Footnote 184 than the farcical commodities turned out by Nicolai that truly mattered. By Kant’s logic, it was Kant’s Königsberg publisher, Friedrich Nicolovius, who instead materially advanced the German enlightenment by publishing the two open letters and Kant’s other works such as Die Metaphysik der Sitten (‘The Metaphysics of Morals’).

Consistent with Kant’s essays in the Berlinische Monatsschrift, the two open letters concluded with the printed authorial name ‘I. Kant’, at once identifying Kant as their responsible ‘speaker’ and affirming Kant’s 1785 understanding of the ethics of authorship and its material basis. The proper names ‘Justus Möser’ and ‘Friedrich Nicolai’, printed on Möser’s posthumous collection as the names of the author and publisher respectively, allowed Kant to identify and hold accountable the ‘speaker(s)’ whose speech and action, in his view, obstructed the advance of enlightenment. If their texts and activities were to contribute to the process of enlightenment, they had to be critically appropriated as materials with which to clarify the primacy of reason in questions of politics, authorship and publishing. Kant’s own authorial name, ‘I. Kant’, rendered himself accountable for his 1798 intervention into the discourse while also inviting eighteenth-century German readers and us today to read those letters alongside his periodical essays and other writings. Those interventions reflected Kant’s media-theoretical understanding of the authorial name as the material means by which responsibility was assumed and ascribed to individual participants in the German Enlightenment. The public use of reason materially depended on the printing of authorial names in textual publications. Rather than simply consolidating the myth of proprietary authorship (though that might well have been one of its effects), the authorial name was bound up in an ethics of authorship that Kant understood to be central to enlightenment practice.

Kant qua Proprietary Author?

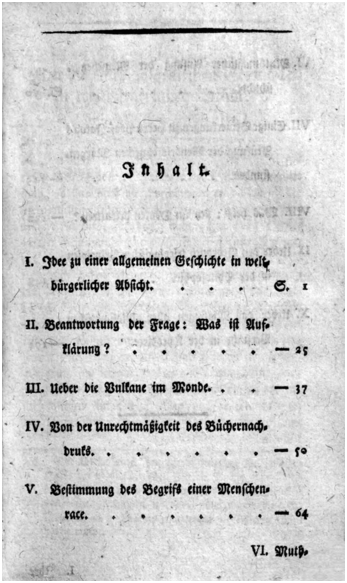

Kant’s argument for the wrongfulness of reprinting did not prevent his works from being reprinted and sold by illegitimate publishers and booksellers. In 1793, there appeared in Frankfurt and Leipzig an unauthorised edition of Kant’s writings, Zerstreute Aufsätze (‘Scattered Essays’), which included versions of both his 1784 and 1785 essays from the Berlinische Monatsschrift (see Figures 4.5 and 4.6).Footnote 185 The illegitimacy of the text’s reprinting is suggested by its title page that excluded the names of its editor, publisher and printing house. Such anonymity not only undermined the enforcement of the already limited system of print privileges in eighteenth-century Germany but also worked against the system of rights that Kant had conceived and attached to the printed book.

Figure 4.5 Title page of Kant’s Zerstreute Aufsätze.

Figure 4.6 Contents of Kant’s Zerstreute Aufsätze.

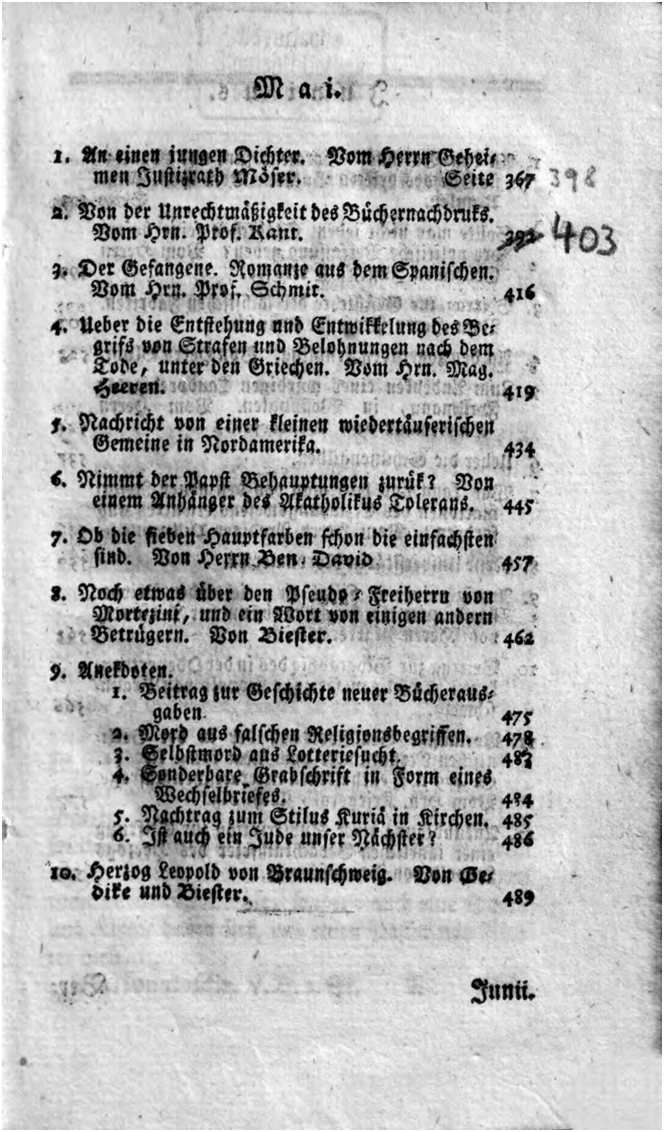

Though Kant’s authorial name did appear in the 1793 edition, its form and placement so departed from that in the Berlinische Monatsschrift as to effect a subtle variation of the author-function as Kant had understood it. As previously noted, the authorial name in Kant’s 1785 essay, ‘I. Kant’, was a print remake of Kant’s autograph. In both the original contents of the May 1785 issue and the master contents of the fifth volume of the periodical, Kant’s authorial name was printed after and alongside the essay title in a more formal fashion that included his gendered and academic titles while omitting his forename entirely: ‘Vom herrn Prof. Kant’; ‘Vom hrn. Prof. Kant’ (see Figures 4.7 and 4.8). Whereas the title pages of the periodical had foregrounded the names of the editor-publishers and printing house, the 1793 reprint instead designated the title ‘scattered essays’ as a single-authored collection re-grouped under the formal appellation adopted in those earlier content pages: ‘Von / herrn Professor / Kant’.Footnote 186 The more ‘personal’ figure of ‘I. Kant’ (already to an extent depersonalised by the nominal abbreviation and the signature’s remediation) gave way to the formal, revered figure of scholarly authority. Kant’s interest in making authors responsible for their speech was subordinated to the more commercially relevant interest of securing the marketability of the literary commodity by attaching to it a brand name of an authoritative figure with institutional and gendered credentials. The eighteenth-century print machinery reworked the authorial name in accordance with the commercial imperative. Enclosed within a single-authored collection reprinted and sold for profit without the author’s consent, Kant’s essays on enlightenment and author’s rights need not affirm the author’s intended sign-off in the periodical whose typography he respected and recommended.Footnote 187

Figure 4.7 Original contents of the May 1785 issue of the Berlinische Monatsschrift.

Figure 4.8 Master contents of the May 1785 issue of the Berlinische Monatsschrift.

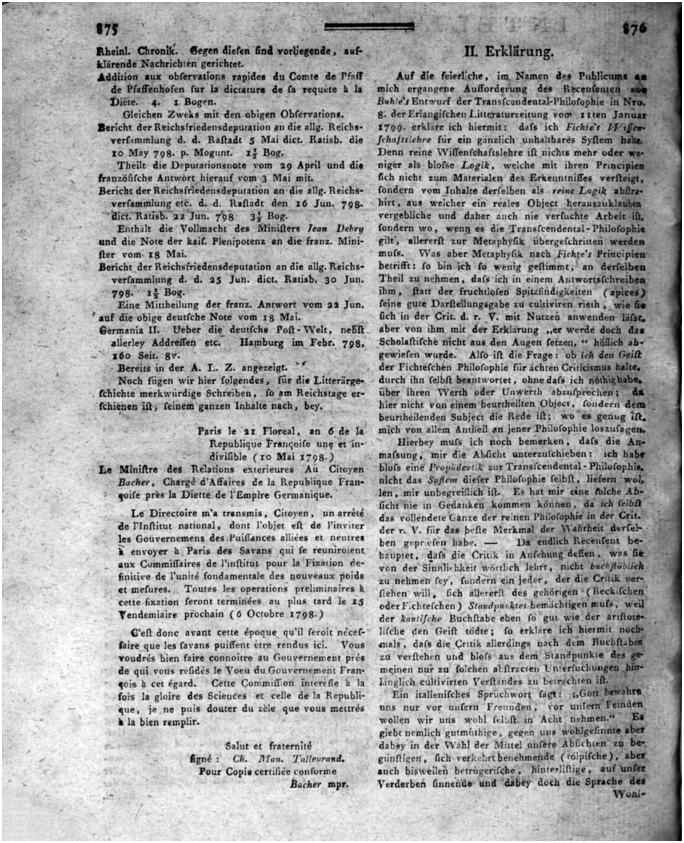

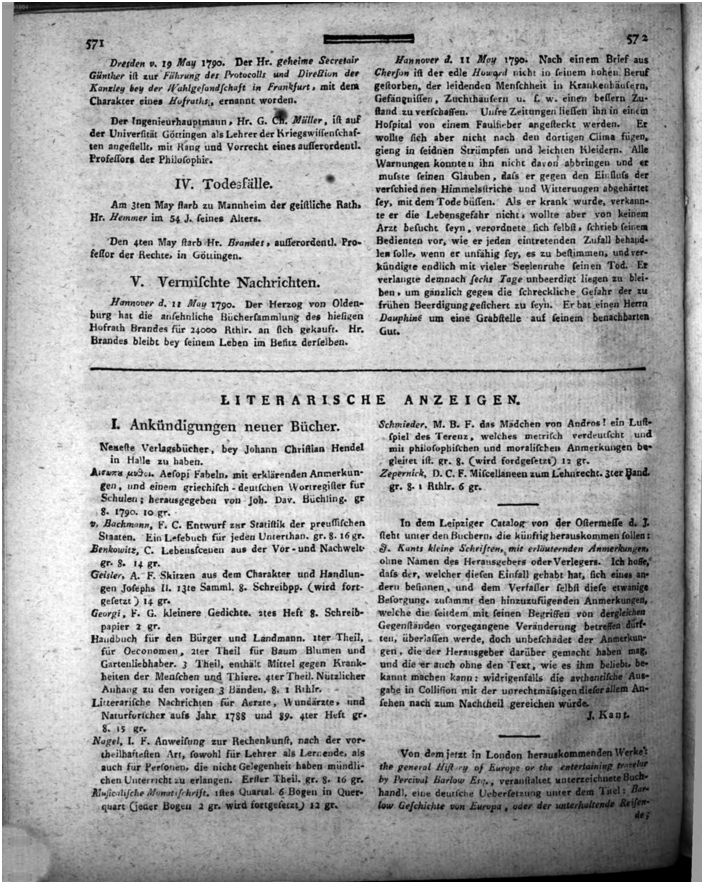

Critical of the unauthorised reprinting of his own works, Kant relied on reputable daily periodicals to denounce and discredit pirated editions that came to his awareness, asserting his authorship in, and authority over, the original works through public notices that bore his authorial name. In the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, a respected and prolific daily that rivalled Nicolai’s Allgemeine Deutsche Bibliothek, there appeared at least two such notices in which the authority of ‘I. Kant’ was asserted to disavow the reprints.Footnote 188 On 12 June 1790, under the section Literatur Zeigen (‘Literature Advertisements’), Kant posted an anti-advertisement of a reprint of his works indexed in a recent book catalogue (see Figure 4.9). The translation reads:

In the Leipzig Catalogue of this year’s Easter Fair, it is stated that amongst the books to be published is I. Kant’s Minor Writings, with Explanatory Notes [I. Kants kleine Schriften, mit erlaüternden Anmerkungen] without the name of the editor or publisher. I hope that the person behind this idea would think of something else, and leave to the author the possibility of such arrangement along with the additional notes, which may concern the changes in such concepts that have since happened, but without prejudice to the notes that the editor might have made and which he could also make known without the text as he saw fit: otherwise, the authentic edition in collision with the illegitimate one would be detrimental to the latter in all respects.

In its title appropriation of ‘I. Kant’ the pirated edition of Kant’s texts masqueraded as a publication authorised by Kant himself. Given the non-disclosure of editor’s and publisher’s names, neither Kant nor the reading public at large would have been able to hold those print actors to account for the quality of its printing and the accompanying notes. It was left to Kant to reclaim his technologised autograph and assert his authority to comment on and update his writings. The presence of the author as a living being who evolved alongside and beyond the original publication, able to look back at different editions and assess their authenticity and limits, is critically staged in and by Kant’s onymous note. In Kant’s time, ‘I. Kant’ at once contributed to the problem of print proliferation as an exploitable brand name and acted as the material basis of the author’s proffered solution, enabling the latter’s assertion of authority to (dis)authenticate and (dis)avow textual publications.

Figure 4.9 Kant’s 1790 public notice in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung.

Today, an Anglophone reader of Kant’s essay on author’s rights is likely to refer to Mary J. Gregor’s English translation in Practical Philosophy of The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant.Footnote 190 Between the publication of the contemporary translation and that of the late eighteenth-century German text is a supervening period of more than two hundred years with attendant transformations in, and transactions between, German, American, European and global Anglophone culture. With respect to legal culture, both Germany and the United States have established national traditions of copyright law with their pertinent statutes. Notwithstanding some evident differences between these regimes of author’s rights and copyright, they partake in and reproduce a shared proprietary perspective on the literary work as the original creation of its author.Footnote 191 Under sections 2(1) and 2(2) of the Urheberrechtsgesetz (‘Act on Copyright and Related Rights’), Sprachwerke (‘literary works’) and other Werke (‘works’) protected under the Act are defined as persönliche geistige Schöpfungen (‘personal intellectual creations’), which coheres with the European standard of originality.Footnote 192 Section 7 clarifies that the Urheber (‘author’) is the Schöpfer des Werkes (‘creator of the work’). The author has das ausschließliche Recht, sein Werk in körperlicher Form zu verwerten (‘the exclusive right to exploit the work in its material form’), including das Vervielfältigungsrecht (‘the right of reproduction’). Similar to UK copyright law, the German statute provides for a presumption of authorship based on the conventional appearance of the author’s name on the published work.Footnote 193 As discussed in Chapter 1, section 102(a)(1) of Title 17 of the United States Code provides that ‘[copyright] protection subsists … in original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression’, including ‘literary works’.Footnote 194 The US Supreme Court has clarified that authorship presupposes originality in the sense of ‘independent creation plus a modicum of creativity’.Footnote 195 Similar to in Germany, the owner of literary copyright in the United States is able to exercise a number of proprietary rights, including the right to reproduce it.Footnote 196 In both jurisdictions, the literary work is apprehended to be its author’s original creation. Though Kant dismissed uses of the property idiom to describe and regulate print publishing during the late eighteenth century, the myth of the proprietary author now prevails across copyright regimes.