Introduction

Public attitudes towards subnational government have become more important in an era of multilevel governance. A significant rise of regional and local authority has re‐allocated decision‐making powers and policy responsibilities from the national towards subnational governments (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Niedzwiecki, Chapman Osterkatz and Shair‐Rosenfield2016; Ladner et al. Reference Ladner, Keuffer, Baldersheim, Hlepas, Swianiewicz, Steyvers and Navarro2019). Public support for decentralisation is crucial for the legitimacy of any multilevel governance system yet surprisingly little research has been devoted to exploring citizen's preferences regarding the allocation of authority and responsibilities between national and subnational governments (Jeffery Reference Jeffery, Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014). The few studies that have surveyed public opinion towards regional authority in Europe, North America and Australia point towards a ‘devolution paradox’ among citizens who have clear preferences for regional government to do more but are less keen on the idea of policy diversity across regions (Henderson et al. Reference Henderson, Jeffery, Wincott and Wyn Jones2013, Reference Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014; Henderson & Weissert Reference Henderson and Weissert2012; Jeffery & Pamphilis Reference Jeffery and Pamphilis2016; Weissert & Jones 2015). This constitutes a paradox because a preference for having more regional government is not matched by openness to its logical corollary: that what regional governments with more powers do is likely to vary from place to place (Jeffery Reference Jeffery, Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014: 24–28; see also Brown Reference Brown2013 and Brown & Deem Reference Brown, Deem, Jedwab and Kincaid2018).

This paper makes two contributions that provide an answer to the ‘devolution paradox’, drawing upon the unique International Constitutional Values Survey (ICVS), which includes 4,930 respondents from 141 regions in eight countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States) (see Brown et al. Reference Brown, Deem, Jedwab and Kincaid2016, 2018). The first contribution is to show that citizens’ preferences for greater regional authority are not all the same: they can be broken down into preferences for more self‐rule – that is, for an autonomous sphere for regional government – and preferences for more shared rule – that is, for collaboration between national and regional governments. The ICVS data reveal that citizens differentiate between preferences for self‐rule and preferences for shared rule.

The second contribution is to reveal that preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule drive citizens’ preferences for different policy outcomes central to the devolution paradox. The empirical analysis clearly shows that preferences for self‐rule are strongly associated with support for stronger regional government, whereas preferences for shared rule have no impact at all on attitudes towards the strength of regional government. In contrast, while preferences for self‐rule and shared rule are both correlated with favourable preferences for fiscal transfers from richer to poorer regions, the impact of preferences for shared rule is almost twice as large than the impact of preferences for self‐rule on support for fiscal transfers.

Taken together, these results suggest an important way in which the ‘devolution paradox’ may appear larger than it actually is. Positive attitudes towards more regional government are driven by preferences for self‐rule, whereas positive attitudes towards inter‐regional fiscal transfers to ensure policy uniformity across the state‐wide territory are mainly driven by preferences for shared rule. This helps to unravel the ‘devolution paradox’ because preferences for self‐rule and shared rule are variations of a preference for more regional authority and each variation is associated with support for a logically consistent policy outcome.

The next section of this paper reviews previous literature on public attitudes towards regional government. The third section explains the relationships between self‐rule, shared rule and the devolution paradox and develops hypotheses about how preferences for self‐rule and shared rule have different impacts on preferences for regional reform and inter‐regional fiscal transfers. The fourth section introduces the ICVS and discusses the main independent variables (preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule) and the main dependent variables (preferences for regional reform and for inter‐regional fiscal transfers). Method and control variables are discussed in the fifth section and the results are presented in the sixth section. The final section concludes with a discussion of the implications of the results for understanding the devolution paradox.

Previous research on public attitudes towards regional government

Public opinion regarding regional government is rarely studied (Jeffery Reference Jeffery, Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014; Weissert & Jones 2015). This is surprising, considering the omnipresence and increasing relevance of regional governments (Hendriks et al. 2010; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Niedzwiecki, Chapman Osterkatz and Shair‐Rosenfield2016). Moreover, research indicates that citizen support for subnational governments constitutes an important dimension of diffuse support for the overall constitutional regime of a country. Diffuse support refers to the evaluation of the overall regime, broadly defined by Hobolt and De Vries (Reference Hobolt and De Vries2016: 415) as ‘the system of government and the constitutional arrangements underlying it’.

Survey research in federal countries typically taps into specific support of citizens. That is, public opinion regarding binding collective decisions and actions taken by political actors operating within the system of government (Norris Reference Norris1999). Examples of such questions gauge which levels of government provide most value for money, the perceived effectiveness of government levels, the popularity of the taxes raised by different tiers of government, the desirability of intergovernmental fiscal transfers and perceived federal government interference with regional decision making (Brown & Deem Reference Brown and Deem2016; Cole & Kincaid Reference Cole and Kincaid2006; Cole et al. Reference Cole, Kincaid and Parkin2002; Jedwab Reference Jedwab, Jedwab and Kincaid2018; Kincaid & Cole Reference Kincaid and Cole2011, Reference Kincaid and Cole2016). Questions tapping into diffuse citizen support for regional governments are lacking, despite the fact that specific support for policies decided and implemented by regional governments is likely to first and foremost depend on the desirability of having a regional government (Brown & Deem Reference Brown, Deem, Jedwab and Kincaid2018: 231; McGrane & Berdahl Reference McGrane and Berdahl2020: 3–4).

Some surveys include questions that ask citizens about their preferences for regional government and most of them tap into the desired level of autonomy for regional government. These questions ask respondents two questions: first, whether a federal form of government (in which power is constitutionally divided between a national and regional governments) is preferable to any other kind of government; and second, which level of government has too much power or needs more power (Jedwab Reference Jedwab, Jedwab and Kincaid2018; Kincaid & Cole Reference Kincaid and Cole2005, Reference Kincaid and Cole2016). Most frequently, respondents are asked to indicate whether they prefer no regional government at all, the status quo of decentralisation, fewer or more powers for their regional government, or independence for their region (Henderson et al. Reference Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014; Jedwab & Kincaid Reference Jedwab and Kincaid2018). This kind of question features often in regional election surveys and public opinion polls fielded in regions where there is broad support for more regional autonomy and independence, such as the Basque Country, Catalonia, Scotland and Quebec (Liñeira & Cetrà Reference Liñeira and Cetrà2015).

A serious limitation of these questions is that they tend to conceive preferences for regional government as one dimensional, whereby the allocation of authority between national and subnational governments is a zero‐sum trade‐off. That is, more authority for one level of government implies less authority for another level of government. This conceptualisation is at odds with how scholars think of regional authority and how regional authority is exercised in practice. Scholars of federalism have long argued that a federal constitution implies both self‐rule – that is, the authority that is exercised within a region – and shared rule – that is, the authority co‐exercised between regional and federal governments in the country as a whole (Elazar Reference Elazar1987; Riker Reference Riker1964). Importantly, Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Niedzwiecki, Chapman Osterkatz and Shair‐Rosenfield2016) have revealed that the concepts of self‐rule and shared rule travel well to non‐federal countries where they help to describe regional authority in unitary and regionalised states.

Self‐rule, shared rule and the devolution paradox

Do citizens actually perceive regional government in terms related to the concepts of self‐rule and shared rule? Most of the above‐mentioned survey questions are geared only towards measuring preferences for self‐rule and do not tap into preferences for shared rule. An important exception is the research by A. J. Brown and his co‐authors, who have made considerable progress in developing survey questions that measure citizens’ diffuse support for a federal constitution through the concept of federal political culture (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Deem, Jedwab and Kincaid2016, Reference Brown, Deem and Kincaid2018). Federal political culture can be understood as ‘the extent to which the political attitudes and beliefs of a population reflect attachment to key values associated with federalism’ (Brown Reference Brown2013: 297). It incorporates public attitudes that span diffuse sociological considerations to more specific judgments about institutional design and constitutional structures (Brown & Deem Reference Brown, Deem, Jedwab and Kincaid2018: 226–232). Using a battery of survey questions, Brown (Reference Brown2013) and Brown and Deem (Reference Brown, Deem, Jedwab and Kincaid2018) classify most respondents in Australia as clear federalists because they see desirability in both the division of power between federal and state government and legal diversity across the states. However, around a third of the respondents are ‘conflicted’ because they combine a high preference for a division of power with a low preference for legal diversity or vice versa. These respondents are ‘paradoxical’ because ‘legal diversity largely presupposes at least some division of power, and division of power largely guarantees at least some legal diversity’ (Brown Reference Brown2013: 302–303; see also Brown & Deem Reference Brown, Deem, Jedwab and Kincaid2018: 236–239).

Brown's approach draws on the ‘devolution paradox’ developed by Henderson and others to summarise their observations that ‘… citizens in federal and regionalized states typically want their regional institutions of government to do more than they do now, and central government institutions less; yet at the same time they appear reluctant to embrace what would appear to be logical consequences, namely more inter‐regional variation, and less intervention to secure state‐wide equity, in public policy provision’ (Henderson et al Reference Henderson, Jeffery, Wincott and Wyn Jones2013: 304). The idea of a devolution paradox built conceptually on Jeffery's earlier analysis of a ‘tension’ among citizens in the post‐devolution United Kingdom ‘between shared values and policy preferences that barely vary … and a desire for even fuller “ownership” of politics at the devolved level’ (Jeffery Reference Jeffery, Adams and Schmueker2006: 11) or, more simply, a ‘tension between equity and diversity’ (Jeffery Reference Jeffery and Greer2009: 73).

While much of the impetus for exploring the devolution paradox came from British political developments (Henderson et al Reference Henderson, Jeffery, Wincott and Wyn Jones2013: 304), evidence of the same tension between regional autonomy and national uniformity was soon found elsewhere. Henderson, for example, surveyed 14 regions in five countries (Austria, France, Germany, Spain and the UK). To the question whether a respondent felt that the state or the region should have greater control over political affairs, a clear majority across all regions in both unitary and federal states indicates that the region should have the most influence. At the same time, citizens who desire greater control by the region over political affairs often also indicate that they desire less regional control over various policy areas and that they support policy uniformity across the state‐wide territory (Henderson Reference Henderson, Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014).

In the same study, Henderson (Reference Henderson, Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014: 171–173) suggests that a solution to the devolution paradox may lie in how citizens perceive ‘increased regional influence’ whereby some citizens think about increased self‐rule for their region, whereas other citizens have an elevated level of shared rule in mind (see also Jeffery Reference Jeffery, Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014 and Wincott & Wyn Jones Reference Wincott, Wyn Jones, Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014). There is more survey evidence that implies that citizens differentiate between preferences for self‐rule and preferences for shared rule. Kincaid and Cole (Reference Kincaid and Cole2016) perform a factor analysis on respondent scores on six survey items in Canada, Germany, Spain and the US and they retrieve two dimensions which they label ‘feelings of regional equity’ and ‘feelings of regional subordination’.1 The former relates to feelings related to fairness, equity, and respect in the treatment of regions, whereas the latter tap opinions about regional control and independence.

As Kincaid and Cole (Reference Kincaid and Cole2016: 63) note, the theoretical importance of the finding that two latent components underly responses is that ‘Citizens consider at least these two dimensions of the region's position in their federation, suggesting that citizens can make somewhat complex distinctions’. The latent dimensions identified by Kincaid and Cole (Reference Kincaid and Cole2016) could tap into preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule considering that self‐rule is about regional control and independence (‘feelings of regional subordination’), whereas shared rule concerns collaboration between regional and national governments who perceive each other as equal partners (‘feelings of regional equity’).

Assuming that citizens differentiate preferences for self‐rule from preferences for shared rule, another question is whether these indicators – as proxies for diffuse regime support – drive perceptions on specific policy outcomes (Brown & Deem Reference Brown, Deem, Jedwab and Kincaid2018: 226–232). In other words, do preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule underlie opinions towards different policy outcomes? Jeffery and Pamphilis (Reference Jeffery and Pamphilis2016) provide compelling arguments that this is the case in Germany. They find that citizens in Bavaria are less in favour of fiscal transfers from rich to poor regions than citizens from Thuringia and these preferences are boosted by stronger regional attachments. Citizens in both German Länder also think ‘paradoxically’ because citizens with strong attachments to their Land also believe that their Land government ought to be more influential nationally. Jeffery and Pamphilis (Reference Jeffery and Pamphilis2016: 188–189) explain this as follows:

… Thuringians wanted a strong influence for their Land government in state‐wide decision making, seeing this as the best means of securing policies like fiscal equalisation that benefit their Land. Bavarians by contrast were more divided, with a substantial proportion seeing disadvantage accruing from state‐wide policies like fiscal equalisation and looking to the Land government to work more at Land level to secure their interests. To put this into the language of comparative federalism research, Thuringians appeared to favour shared rule involving cooperation of federal and Länder governments in setting state‐wide policy standards, while Bavarians appeared divided between those favouring shared rule and those favouring a more autonomous form of self‐rule.

This is an important observation because it implies that citizens differentiate between preferences for self‐rule and preferences for shared rule, that they can do so differently across regions within the same county, and that these preferences are differently linked to the desirability of specific policy outcomes. Bavarians are more in favour of self‐rule for their Land and are therefore inclined to dislike the idea of inter‐regional fiscal transfers, whereas Thuringians are more in favour of inter‐regional fiscal transfers because they tend to be more supportive of shared rule between Land and federal governments.

In the next section, we develop two indicators that tap into preferences for self‐rule and preferences for shared rule and provide evidence that citizens differentiate between these preferences. Then we discuss the two questions that are used to tap into preferences for regional reform and for inter‐regional fiscal transfers. These four measurements enable an empirical test of two propositions suggested by Jeffery and Pamphilis (Reference Jeffery and Pamphilis2016) that will guide the empirical analysis in the results section:

Hypothesis 1: A preference for self‐rule is positively related to a preference for regional reform that empowers regional government.

Hypothesis 2: A preference for shared rule is positively related to a preference for inter‐regional fiscal transfers from richer to poorer regions.

The ICVS dataset: Self‐rule, shared rule, regional reform and inter‐regional fiscal transfers

This paper relies on the ICVS, which includes questions that tap into citizen preferences for preferences for self‐rule and shared rule as well as regional reform and inter‐regional fiscal transfers. We use the second wave of the ICVS (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Deem and Kincaid2018) because it adds three countries (Belgium, France and Switzerland) to the five in the first wave (Australia, Canada, Germany, United Kingdom and United States). A stand‐alone survey in Australia was fielded online between 3 and 10 August 2017 by OmniPoll through panels managed by LightSpeed Research. The other seven countries were surveyed by KantarTNS who used the Ncompass internet omnibus survey between 19 and 24 April 2018. To achieve maximum representativeness, sample quotas were set for each state/region, gender and age. More detail on the ICVS is provided by Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Kincaid, Deem and Cole2016, Reference Brown, Deem and Kincaid2018).

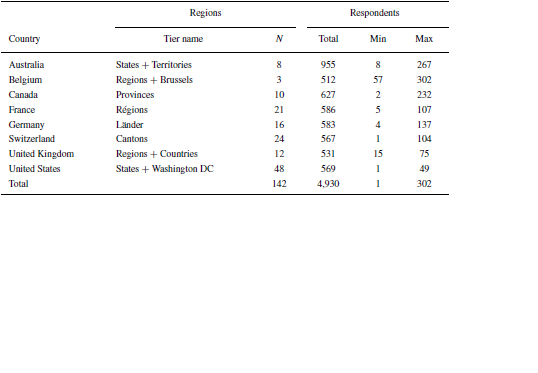

Table 1 provides an overview of the included regions and number of respondents for each of the eight countries. The ICVS includes 4,930 respondents from almost all regions of the eight countries. The few exceptions that are not included are three territories in Canada, one region in France, two cantons in Switzerland and two states in the United States. The number of respondents varies widely across regions and this is taken into account by employing multilevel regression models (which are discussed in more detail below).

Table 1. Included countries, regions and number of respondents

Source: International Constitutional Value Survey (Brown et. al Reference Brown and Deem2016, Reference Brown, Deem and Kincaid2018).

The main independent variables: Preferences for self‐rule and shared rule

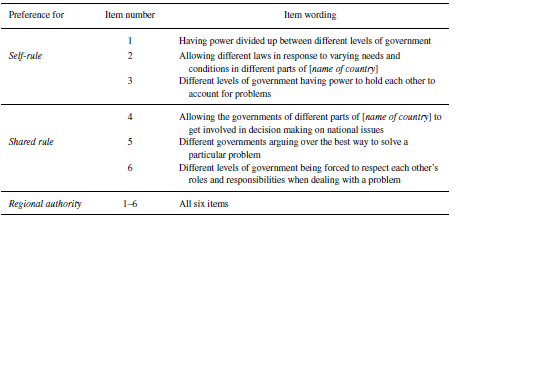

The ICVS is particularly useful to explore citizen's preferences towards regional government because, to the best of our knowledge, it is the only cross‐national survey that taps into preferences for self‐rule and shared rule instead of preferences for regional authority in general. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they found the six features of multilevel government displayed in Table 2 desirable or undesirable. The question reads: ‘Please state if you think each of these is a desirable feature, or an undesirable feature of having different levels of government’. The survey questions and items deliberately did not include the terms ‘federal’, ‘regional authority’, ‘self‐rule’, or ‘shared rule’ to avoid complications arising from a lack of familiarity with these terms among respondents and to allow for comparisons between federal and non‐federal countries (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Deem, Jedwab and Kincaid2016, 2018).

Table 2. Survey items used to measure preferences for regional authority, self‐rule and shared rule

Note: The items were preceded with the following question: ‘Please state if you think each of these is a desirable feature, or an undesirable feature of having different levels of government’. Respondents could indicate whether these features were very desirable (score of 4), desirable (3), undesirable (2) or very undesirable (1). The order of the statements was randomised. Respondents who opted for ‘can't say’ are excluded from the analysis.

Items 1, 2 and 3 tap into preferences for having divided powers, legal diversity and governmental accountability. These items are measures of the concept of self‐rule, that is, the extent to which regional governments exercise authority over citizens who live in the region. Items 4, 5 and 6 measure aspects of a preference for shared rule, that is, the extent to which regional governments exercise authority in the country as a whole through collaboration.

Explanatory and confirmatory factor analysis (see Table A1 and Figure A1 in the Appendix in Supplementary Information) provides strong evidence that these six survey items validly and reliably tap into preferences for regional authority, self‐rule and shared rule. All six items clearly tap into one single dimension (Cronbach's alpha 0.73; all item factor loadings above 0.58; explained variance of 44 per cent). Although the Cronbach's alphas decrease to 0.60 when separate factor analyses are run for items 1–3 (self‐rule) and 4–6 (shared rule), the factor loadings (above 0.71) and explained variances (56 per cent) are both higher. A more detailed discussion can be found in the Appendix in Supplementary Information. Scores have been averaged across all six items (preferences for regional authority), across items 1–3 (preferences for self‐rule) and across items 4–6 (preferences for shared rule). The averages have been subsequently re‐scaled so that they vary between a minimum of 0 – very undesirable across all items – to a maximum of 1 – very desirable across all items (means and standard deviations are provided in Table A2 in the Appendix in Supplementary Information).

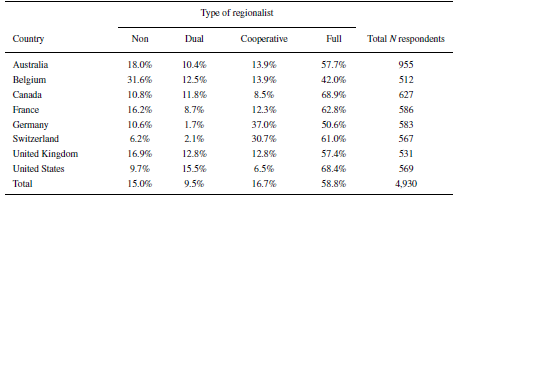

In Table 3, we display percentages of types of regionalists found in each of the eight countries. Respondents are classified according to type of regionalist according to their combined preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule. Non‐regionalists prefer neither (scores below 0.5), whereas full regionalists prefer both (scores above 0.5). Dual regionalists have a preference for self‐rule (scores above 0.5) but not for shared rule (scores below 0.5), whereas cooperative regionalists have a preference for shared rule (scores above 0.5) but not for self‐rule (scores below 0.5).

Table 3. Type of regionalist per country

Table 3 reveals that, except for Belgium, an absolute majority of respondents are full regionalists who prefer both self‐rule and shared rule (in Germany this majority is very slim). Thus, most citizens have the potential to behave ‘paradoxically’ if these preferences for full regionalism are linked to an inconsistent set of preferred policy outcomes. However, considerable shares of respondents are likely not to behave ‘paradoxically’ because they are non‐regionalists, or prefer self‐rule over shared rule (dual regionalists) or prefer shared rule over self‐rule (cooperative regionalists). Belgium stands out with a relatively high share of non‐regionalists (31.6 per cent), whereas the highest shares of cooperative regionalists can be found in Germany (37.0 per cent) and Switzerland (30.7 per cent). The United States has the highest share of dual regionalists (15.5 per cent), although the difference with most other countries in the study is relatively small. These country differences can be largely explained by various levels of decentralisation across the countries (Schakel & Brown Reference Schakel and Brown2021). In the models presented below, we control for differences in decentralisation across regions and countries by including self‐rule and shared rule scores for all regions taken from the Regional Authority Index (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Niedzwiecki, Chapman Osterkatz and Shair‐Rosenfield2016), as well as country dummies. We also use the country dummies to account for differing countrywide levels of preference for self‐rule and for shared rule.

The dependent variables: Preferences for regional reform and inter‐regional fiscal transfers

The ICVS contains two items that can be used to capture the two arms of the devolution paradox: preference for stronger regional power and preference for uniformity of public provision. We use the following question to tap into citizens’ preferences regarding the powers of regional government.

Now a question about [INSERT COUNTRY]’s system of government in the future – say, 20 years from now.

Thinking about the structure of [INSERT COUNTRY]’s system of government, which one of the following systems do you personally think would be the best system in the future?

0 = A system with a single national government but no [state] governments.

1 = A system in which [state] governments have fewer powers than they do now.

2 = A system where the [state] governments have the same powers as they do now.

3 = A system in which [state] governments have more powers than they do now.

4 = A system that allows a [state] to become an independent nation.

5 = Can't say.

The word ‘state’ was replaced by the appropriate regional label in the preferred language opted by the respondent. Respondents who opted for option 5 ‘can't say’ are excluded.

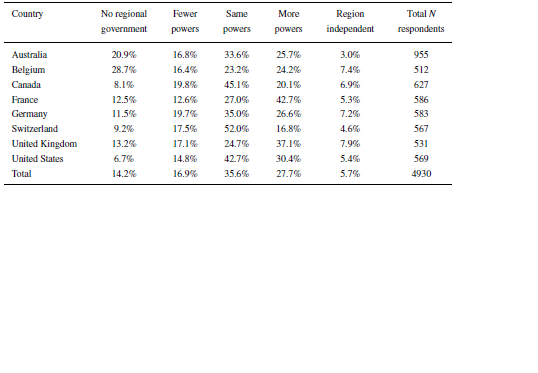

Table 4 provides an overview of how respondents answered this question in each of the eight countries. The highest support for weak or no regional government is found in Australia (37.7 per cent) and Belgium (45.1 per cent), while respondents in the unitary countries of France (48.0 per cent) and the United Kingdom (45.0 per cent) are strongest in favour for more regional authority (more regional powers or regional independence). Respondents in the decentralised federations of Canada (45.1 per cent), Switzerland (52.0 per cent) and the United States (42.7 per cent) have the highest proportions of citizens who are happy with the status quo (regions should have their current powers).

Table 4. Preferences on regional reform in eight countries

Note: Shown are the percentages of respondents who indicated their preference on the system of government in 20 years time.

Preferences for inter‐regional fiscal transfers to ensure equality of public services are measured by the following question.

To what extent do you agree or disagree with each of these statements?

Money should be transferred from the richer parts of [NAME OF COUNTRY] to the poorer parts to ensure that everyone can have similar levels of public services.

0 = Strongly disagree

1 = Somewhat disagree

2 = Somewhat agree

3 = Strongly agree

4 = Can't say

Respondents who opted for option 4 ‘can't say’ are excluded.

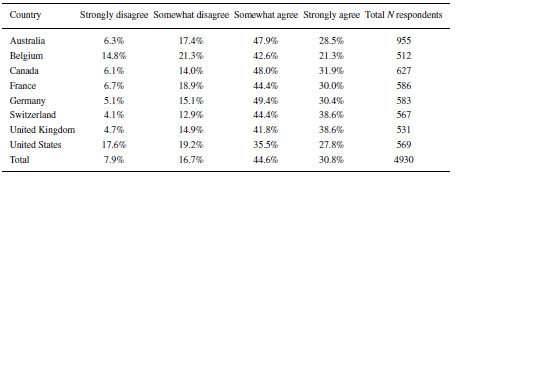

Table 5 provides an overview of how respondents answered this question in each of the eight countries. Three‐quarters of the respondents somewhat agree or strongly agree with the statement that inter‐regional fiscal transfers should be used to ensure similar levels of public services, while a quarter of the respondents somewhat disagree or strongly disagree with this statement. Respondents from Belgium (63.9 per cent) and the United States (63.3 per cent) are least in favour of transfers to ensure similar public services, whereas respondents from Switzerland (83.1 per cent) and the United Kingdom (80.4 per cent) are most in favour for fiscal solidarity to ensure equal public services across the country.

Table 5. Preferences on inter‐regional fiscal transfers in eight countries

Note: Shown are the percentages of respondents who indicated their level of agreement on the statement that money should be transferred from the richer parts of their country to the poorer parts to ensure that everyone can have similar levels of public services.

Method and control variables

The impact of preferences for regional authority on preferences for regional reform and inter‐regional fiscal transfers are analysed with multilevel regression models whereby 4,930 respondents are clustered in 142 regions. Country dummies are included to account for clustering of regions by country. In addition, country dummies account for other country‐level factors that impact on preference scores but are not included in the model. This model specification is chosen because variance decomposition models reveal that the variances in the scores on the dependent variables (preferences for regional reform and preferences for inter‐regional transfers) as well as on the main independent variables (preferences for regional, authority, for self‐rule and for shared rule) are statistically significant at the country (3–8 per cent), regional (1–2 per cent) and respondent (above 90 per cent) level (Tables A3 and A4 in the Appendix in Supplementary Information). We run two types of models to provide empirical evidence that preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule have a different impact on preferences for regional reform and for inter‐regional fiscal transfers. The first model includes preference scores for regional authority, whereas the second model includes preference scores for self‐rule and for shared rule.

The models include several control variables, six of which vary at the region level. Self‐rule is the authority exercised by a regional government over those living in its territory, measured on a scale of 0 to 18. Shared rule is the authority exercised by a regional government or its representatives in the country as a whole, measured on a scale ranging from 0 to 12 (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Niedzwiecki, Chapman Osterkatz and Shair‐Rosenfield2016). Citizens from regions with higher regional self‐rule scores might have less appetite for regional reform, whereas citizens from regions with higher regional shared rule scores could be more supportive of inter‐regional fiscal transfers. We include country dummies in the models because most variation in regional self‐rule and shared rule scores occurs between rather than within countries. Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Niedzwiecki, Chapman Osterkatz and Shair‐Rosenfield2016) classify regions on the basis of whether a region has an authority arrangement that sets it apart from the other regions within the country. The models below include a differentiated dummy when a region has such an authority arrangement.2 Citizens from differentiated regions might be expected to want stronger regional autonomy and fewer fiscal transfers.

To capture the impact of the socio‐economic context of a region we include three variables. First, a language region dummy variable scores positive when a majority of the citizens within a region speaks a different language from the dominant national language (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe and Marks2016; Shair‐Rosenfield et al. Reference Shair‐Rosenfield, Schakel, Niedzwiecki, Marks, Hooghe and Chapman‐Osterkatz2020).3 Citizens from a linguistically distinctive region may be more supportive of regional reform that strengthens regional autonomy and they could have lower preferences for inter‐regional fiscal transfers. Second, we include a fiscal donor region dummy variable that scores positive when – in 2017 or a previous year close to 2017 – a region contributes more to than it receives from fiscal equalisation (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Germany and Switzerland) or pays more federal/central government tax than it receives in fiscal transfers from the federal/central government (France, the United Kingdom and the United States; Brenton Reference Brenton2020; Office for National Statistics 2021; Rockefeller Institute of Government 2017; Siliverstovs & Thiessen Reference Siliverstovs and Thiessen2015; Van Rompuy Reference Van Rompuy, Bosch, Espasa and and Solé Ollé2010).4 Third, a regional economy ratio variable measures regional per capita economic wealth relative to the national average in GDP per capita in 2017 (OECD 2021). Citizens from donor regions and economically richer regions within any country may prefer more regional autonomy and lower inter‐regional fiscal transfers.

The models below also include a battery of control variables at the individual level which are generally included in models analysing public opinion on regional government (Henderson et al. Reference Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014; Kincaid & Cole Reference Kincaid and Cole2016): gender (0 = male; 1 = female), age category (1 = below 30; 2 = 30–39; 3 = 40–49; 4 = 50–59; 5 = 60 and above), university education (0 = less than university education; 1 = university education), household income category (1 = first quartile; 2 = second quartile; 3 = third quartile; 4 = fourth quartile within a country), political interest,5 ideological self‐placement,6 relative trust in regional government7 and satisfaction with democracy.8 Respondents who opted for the ‘can't say’ option are excluded. As noted earlier, the models include country dummies to control for varying overall levels of preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule between countries (Table 3). Descriptive statistics for the dependent and independent variables are provided in Table A5 in the Appendix in Supplementary Information.

Results

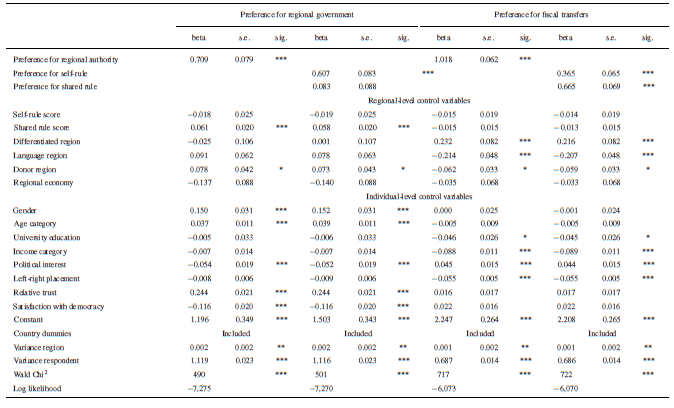

Table 6 displays the results of four multilevel regression models. In the first two models, shown on the left side of the table, preferences for regional reform is the dependent variable, whereas the third and fourth models on the right side use preferences for inter‐regional fiscal transfers as the dependent variable. The first model for each dependent variable uses preferences for regional authority as the main independent variable, whereas the second model in each set adopts preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule as the main independent variables.

Table 6. Explaining preferences for regional government reform and for inter‐regional fiscal transfers from rich to poor regions

Note: *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. Shown are the results of a multilevel regression model whereby 4,930 respondents are clustered within 142 regions. Preferences for regional government vary from 0 (no regional government) to 4 (region should become an independent nation). Preferences for fiscal transfers from rich to poor regions vary from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree).

Preference for regional authority is strongly associated with both preferences for regional reform and for inter‐regional fiscal transfers. An increase of 0.10 in the preference score for regional authority leads to an increase of 0.07 in the preference score for regional reform and to a 0.10 increase in the preference score for inter‐regional fiscal transfers.9

When preference scores for self‐rule and shared rule are used in the models, the results provide strong empirical evidence for the two hypotheses set out in this paper. Preferences for self‐rule are positively related to preferences for regional reform that strengthen regional government, while preferences for shared rule are positively related to fiscal transfers from poorer to richer regions. It appears that preferences for reform to strengthen regional powers relate only to preferences for self‐rule. An increase of 0.10 in the preference score for self‐rule is associated with an increase of 0.06 in the preference score for regional reform. In stark contrast, preference scores for shared rule does not relate to preferences scores for regional reform. On the other hand, support for inter‐regional fiscal transfers to achieve uniform public services appears to relate to both preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule; however, the size of the beta coefficient of the latter is almost twice as large than that of the former. An increase of 0.10 in the shared rule preference score is correlated with an increase of 0.07 in the preference score for inter‐regional fiscal transfers, compared with an increase of just 0.04 when self‐rule preference scores rise by the same amount. These contrasting relationships are robust across different model specifications, that is, an OLS specification with region dummies, a multilevel ordinal logit model specification, and a ‘jack‐knife’ assessment whereby a different country is excluded each time the model is run (Tables A6, A7, A8a and A8b in the Appendix in Supplementary Information).

The results for the individual level control variables contribute to the validity of the overall model results. As expected, respondents with higher household incomes and those who place themselves on the right tend to be less in favour of inter‐regional fiscal transfers from richer to poorer regions. Respondents who have a household income in the first quartile within their country (score of 1) have a 0.36 higher preference for inter‐regional fiscal transfers than respondents who have a household income in the fourth quartile (score of 4). A respondent who places herself at the extreme left (score of 1) has a 0.55 higher preference score for inter‐regional transfers compared with a respondent who places herself at the extreme right (score of 11). Similarly, respondents who place more trust in their regional than in their national governments and respondents who are dissatisfied with how democracy functions are more supportive of regional reform that strengthens regional autonomy. Respondents who have full confidence in regional government but no confidence in national government (score of 3) have a 0.73 higher score for regional reform compared to a respondent who places equal confidence in both regional and national government (score of 0). Respondents who are very dissatisfied with how democracy works in their country (score of 4) have a 0.35 higher preference score for regional reform than respondents who are very dissatisfied (score of 1).

The results also reveal relationships that are more difficult to explain. On regional reform, women have a 0.15 higher score than men and respondents who are 60 years or older (score of 5) have a 0.15 higher score than respondents who are younger than 30 years (score of 1). A respondent who is very interested in politics (score of 4) has a 0.16 lower preference score for regional reform but a 0.13 higher preference score for inter‐regional fiscal transfers compared with a respondent who is not interested in politics at all (score of 1).

In a similar vein, some results for the regional level variables are in line with our expectations, whereas other results are more puzzling. As expected, respondents from donor regions have stronger preferences for regional reforms (0.08 higher preference score) and weaker preferences for inter‐regional fiscal transfers (0.06 lower preference score). Respondents from language regions do not differ from others on regional reforms and are less supportive of fiscal transfers from richer to poorer regions (0.19 lower preference score).

Interestingly, respondents from regions with more shared rule favour regional reform that strengthens regional autonomy and respondents from differentiated regions tend to be more supportive of inter‐regional fiscal transfers from richer to poorer regions. Since the models include country dummies, the shared rule score of a region and the differentiated region dummy explain variation in public opinion across regions within the same country. The preference score for regional reform that strengthens regional autonomy increases with 0.06 points for each additional point on a region's shared rule score. This results, for example, in a 0.36 higher preference score for respondents from Wales or Scotland (shared rule score of 6.5) when compared to respondents from London (shared rule score of 0.5) and from regions in the UK (shared rule score of 0). However, regions with higher shared rule scores than other regions within the country are also differentiated regions (e.g. Quebec, Scotland and Wales). Thus, respondents from these regions are also more supportive towards inter‐regional fiscal transfers from richer to poorer regions and have a 0.22 higher preference score for inter‐regional fiscal transfers compared to respondents from ‘standard’ regions within their country.

Discussion and conclusion

This article makes two important contributions towards better understanding the devolution paradox and, more generally, citizens’ attitudes regarding multilevel governance. First, it develops two indicators that tap into diffuse regime support regarding regional government across federal and non‐federal countries: citizens’ preferences for self‐rule and their preferences for shared rule. Second, the paper presents strong empirical evidence that preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule both drive public opinion towards specific policies related to the devolution paradox in different ways. Preferences for self‐rule are strongly related to positive attitudes towards reforms that strengthen regional government, whereas preferences for shared rule are most strongly associated with favourable opinions towards fiscal transfers from rich to poor regions.

A large number of citizens combine a preference for self‐rule with a preference for shared rule (see Table 3). This combination does not affect citizens’ attitudes to the powers of regional governments, since variations in preferences for regional powers are not associated with variations in shared rule preferences. Self‐rule is doing all the work here (see Table 6). Those respondents who highly favour both self‐rule and shared rule may well think that increased regional autonomy should go hand‐in‐hand with increased regional participation in state‐wide decision making, or with stronger coordination between regional governments, or both (Galais et al. Reference Galais, Martnez‐Herrera, Pallarés, Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014). Why does increased support for self‐rule also increase support for fiscal equalisation, albeit more weakly than support for shared rule? A speculative but plausible answer may be that supporters of more regional power may see fiscal transfers from wealthier to poorer regions as necessary to ensure that regions have the resources to exercise their expanded powers.

Focusing on the devolution paradox from a different angle to ours, Henderson et al (Reference Henderson, Jeffery, Wincott and Wyn Jones2013: 319) noted that ‘a paradox can refer to an apparent contradiction that dissolves on closer or deeper analysis’. That is also the main lesson of our analysis. The devolution paradox is less of a contradiction than it first appears because its two arms – more regional power and policy uniformity – must be understood as resting on more complex and nuanced attitudes toward self and shared rule. Our findings, like those of other researchers, reveal ‘a sophisticated form of multilevel citizenship’ whose assumptions vary between individuals across different social groups, regions and countries (Wincott & Wyn Jones Reference Wincott, Wyn Jones, Henderson, Jeffery and Wincott2014: 185; see also Henderson et al. Reference Henderson, Jeffery, Wincott and Wyn Jones2013: 319).

The results presented in this paper also reveal that there is still much to be learned regarding the causal drivers of citizen preferences towards regional government. Most importantly, the results imply that for a better understanding of citizen attitudes towards regional government, one needs to gauge preferences for self‐rule and for shared rule separately, rather than focusing on regional authority in general.

In addition, researchers would be well advised to investigate the combined impact of preferences for self‐rule and shared rule to understand how these preferences may affect different sets of policy outcomes or have competing impacts on a single policy outcome (Weissert & Jones 2015). This paper hints at one example of these possible policy specific effects. Almost 13 per cent of the respondents (634 out of 4,930) are strong supporters of regional reform (their region should have more powers or should become independent) and intergovernmental transfers (agree or strongly agree) but they prefer regions not to have shared rule (preference score below 0.5). These respondents may appear ‘paradoxical’ because interregional fiscal transfers are often negotiated between regional and central governments, but these respondents may turn out not to be ‘paradoxical’ when they think that central governments are best equipped to redistribute tax revenues across the territory and that regional involvement is not necessary or desirable.

Acknowledgements

The ICVS was funded by the Australian Research Council through ARC Discovery Project 14102682, led by Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia. Analysis was supported by the Trond Mohn Foundation (grant number TMS2019REK01) and the University of Bergen (grant number 812468). We thank project colleagues from Griffith University, University of Sydney, University of NSW, Australian National University, and Lafayette College for collaboration on use of these data; and thank Michael Alvarez, Kiran Auerbach, Claire Dupuy, Anne Lise Fimreite, Rune Dahl Fitjar, Ailsa Henderson, Achim Hildebrandt, Mike Medeiros, Christoph Niessen, Yvette Petersen and Michael A. Strebel for their comments and feedback on previous versions of this paper.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1a. Exploratory factor analysis on six survey items tapping into preferences for regional authority

Figure A1. Measurement model of self‐rule and shared rule

Figure A2. Distributions of the preference scores

Table A2. Citizen preferences for regional authority, self‐rule, and shared rule by country

Table A3. Variance decomposition of citizen preference scores for regional authority, self‐rule, and shared rule

Table A4. Variance decomposition of citizen preference scores for regional government and for intergovernmental transfers

Table A5. Descriptive statistics

Table A6. Robustness Table 6: OLS and including region dummies

Table A7. Robustness Table 6: Multilevel ordinal logit specification

Table A8a. Robustness Table 6: Exclusion of one country at a time; preferences for regional government

Table A8b. Robustness Table 6: Exclusion of one country at a time; preferences for fiscal transfers from rich to poor regions