Introduction

The legislative activity of lawmakers is central to representative democracy, serving as a key mechanism for translating public preferences into policy outcomes. Among various legislative activities, bill sponsorship and floor voting represent critical junctures where lawmakers’ strategic choices become most visible. Bill sponsorship provides legislators opportunities for agenda-setting and position-taking (Riker Reference Riker1986; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1995), while voting decisions reveal how legislators balance competing pressures from their party, ideology, and constituents (Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal1991, Reference Poole and Rosenthal1997). Bill sponsorship also serves as an indicator of the legislature’s independence and autonomy from the executive branch (Choi Reference Choi2006) and demonstrates lawmakers’ professionalism and integrity in their work (Cox and Terry Reference Cox and Terry2008).

Of particular interest is the phenomenon of “waffling,” where legislators vote against or abstain from voting on bills they previously sponsored. This behavioral inconsistency offers a unique window into the strategic calculations legislators make when facing institutional constraints and political pressures. While extensive research has examined waffling in the US Congress (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1995; Miller and Overby Reference Miller and Overby2010, Reference Miller and Overby2014; Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013), our understanding of this phenomenon in different institutional contexts remains limited. The act of bill sponsorship implies not only support for the bill’s content but also a commitment to work towards its passage (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013). However, this commitment does not always extend to the floor vote, as lawmakers may choose to waffle for various reasons, including constituent pressure, party directives, or changes in the bill’s content through amendments.

Existing studies in South Korea have primarily focused on discrete aspects of legislative behavior, analyzing either co-sponsorship patterns (Choi Reference Choi2006; Kim Reference Kim2006; Lee Reference Lee2016), co-sponsorship networks (Lee and Youm Reference Lee and Youm2009; Chang Reference Chang2011), or voting behavior (Jeon Reference Jeon2006; Lee and Lee Reference Lee and Lee2011; Kim Reference Kim2014). While these studies have provided valuable insights, they fail to capture the dynamic nature of legislative behavior across different stages of the legislative process. Recent studies have begun to explore waffling in the Korean context (Ka et al. Reference Ka, Kang and Park2021; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022), but they are limited by their focus on single parliamentary terms or specific bills, and their uncritical application of US-based theoretical frameworks.

The South Korean National Assembly provides an excellent case for extending waffling theory beyond its US-centric origins. Its distinctive institutional features—including proportional distribution of committee chairs and mixed electoral system—create different incentive structures for legislative behavior. Unlike the US Congress, where electoral stability significantly influences waffling behavior, the impact of electoral factors in Korea varies depending on constituent engagement and political context. Furthermore, the Korean National Assembly’s consensus-based features and unique committee chair allocation system create different dynamics for majority–minority party interactions.

This study addresses these limitations by analyzing waffling behavior in the Korean National Assembly across four legislative terms (17th–20th, 2004–2020). We focus on conflict bills—defined as those receiving less than 90 percent approval in plenary votes—as these bills best reveal the strategic calculations underlying legislative behavior. We employ a two-stage analytical approach: first conducting a pooled analysis to identify broader patterns of waffling behavior, then examining three distinct types of waffling—dissent, abstention, and no-show—across different legislative terms. This disaggregated analysis allows us to capture how institutional and political contexts influence legislators’ strategic choices among different types of waffling.

This study makes a significant theoretical contribution to the literature by developing a novel taxonomy of waffling behavior and examining its determinants in a non-Western democratic context. While previous studies have treated waffling as a uniform phenomenon, we conceptualize it as three distinct types—dissent, abstention, and no-show waffling—each representing different strategic choices with varying political costs and implications. While these three types share a common trait—reneging on initial support—they differ significantly in their political signaling and strategic implications. Dissent, or voting against a bill one previously sponsored, is the most publicly visible form of defection and can signal clear opposition to party leadership or a shift in policy stance, often carrying the highest reputational cost. Abstention, by contrast, allows lawmakers to register discomfort without explicitly opposing the bill, serving as a middle-ground tactic that avoids antagonizing party leaders or co-sponsors. Finally, no-show behavior—being absent during the final vote—may be perceived as an even more ambiguous signal, potentially interpreted as strategic avoidance or circumstantial disengagement. Legislators may choose among these forms based on the intensity of intra-party conflict, constituent expectations, and the degree of political risk each option entails.

By analyzing how institutional features, bill characteristics, and legislator attributes differently influence these three types of waffling, we provide a more nuanced understanding of strategic position-taking in legislative politics. Furthermore, our analysis of the Korean National Assembly, with its unique consensus-based features and proportional distribution of committee chairs, demonstrates how institutional context shapes the strategic calculus behind different forms of waffling, thereby extending waffling theory beyond its US-centric origins. This theoretical refinement offers a more comprehensive framework for understanding legislative behavior across different democratic systems and institutional arrangements.

The role of party dynamics in waffling

Waffling is an interesting topic in the study of legislative politics because it is the behavior of changing a legislator’s position on a bill that one has supported and sponsored at the final stage of the legislative process, the floor vote. Krehbiel (Reference Krehbiel1995) defines waffling as participating in bill co-sponsorship but refusing to sign a bill’s discharge petition, while Kirkland and Harden (Reference Kirkland and Harden2016) define waffling as initially sponsoring or co-sponsoring a bill and then voting against the bill’s final vote. In particular, waffling is seen as a risky strategic choice that lawmakers make to ensure their own re-election (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974) amidst the many cross-pressures they face in the legislative process. As such, it is a good case study to understand how lawmakers weigh the importance of factors such as party affiliation, their own ideology, and the interests of their constituency.

The extensive literature on waffling in the US Congress, spanning several decades (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1995; Miller and Overby Reference Miller and Overby2010, Reference Miller and Overby2014; Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013; Kirkland and Harden Reference Kirkland and Harden2016), reveals a diverse range of factors that shape legislators’ waffling. First, studies on the impact of individual legislators’ traits on waffling indicate that legislators are more prone to waffling when they are part of the majority party, possess higher levels of player, lean towards extreme ideologies, and enjoy higher electoral stability (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013; Miller and Overby Reference Miller and Overby2010, Reference Miller and Overby2014). This suggests that all legislative behavior is a strategic choice aimed at ensuring their own re-election (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974), implying that the more a legislator is aligned with the majority party, the wider the vote margin, and the higher the seniority, the more likely they make waffling decisions due to their enhanced chances of re-election. Similarly, Bernhard and Sulkin (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) argue that waffling is a potentially risky behavior involving reneging on the promises of co-sponsors. They explain that the more electoral stability a legislator has, the more willing and able he or she is to absorb any internal and external consequences that may arise. Therefore, the authors argue that the more seniority and electoral stability a lawmaker has, the more likely they are to choose waffling.

Turning to the influence of party on the waffling decision, Kirkland and Harden (Reference Kirkland and Harden2016) show that waffling often occurs when a legislator’s preferences and party preferences conflict, and that legislators in the majority party are more likely to choose waffling. Expanding on this argument, Kirkland and Harden (Reference Kirkland and Harden2018) provide a more comprehensive theoretical framework by reframing waffling as a manifestation of “legislative indecision” that arises from competing demands by multiple principals—primarily constituents and party leaders. Rather than viewing waffling purely as an individual strategic behavior, they argue that legislators often navigate a cross-pressure environment in which they must reconcile conflicting expectations. This framework highlights that waffling can be a rational adaptation to new information or shifts in the political salience of a bill, rather than simply the result of ideological extremity or electoral security.

Importantly, this framework also helps explain why majority-party members might exhibit especially high levels of waffling. As the agenda setter, majority-party leadership frequently initiates amendments to bills during the legislative process to align them with broader party goals or shifting priorities (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005). These amendments can substantially alter the original content of a bill, particularly in high-salience cases, creating distance between the final version and the preferences of the bill’s original sponsors—even when those sponsors belong to the majority party. In such cases, majority-party legislators may find themselves at odds with their own leadership, especially if they represent constituencies with different ideological leanings. Moreover, majority-party members often face lower electoral costs for inconsistency due to stronger institutional positions, greater access to resources, and a higher likelihood of reelection (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013). This relative insulation from political risk allows them greater flexibility to adapt or reverse course when party pressures diverge from original intentions. Thus, waffling among majority-party legislators is not necessarily anomalous but reflects the strategic recalculations that arise from intra-party tension and institutional authority.

In addition to party dynamics, ideological orientation has also been shown to influence waffling behavior. Studies using DW-NOMINATE scores demonstrate that legislators with more extreme ideological positions are more prone to waffling. Miller and Overby (Reference Miller and Overby2010), for instance, argue that the more extreme the ideology of a legislator, the more likely they choose waffling because waffling is about prioritizing vote outcomes over the risk of the consequences of such behavior.

In addition to lawmakers’ personal attributes, the bill’s characteristics are important factors in their waffling decisions. Bernhard and Sulkin (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) explain that policy considerations are an important factor influencing lawmakers’ waffling, and that bills with a large number of cosponsors are considered “commemorative” by voters and lawmakers, which influences lawmakers’ waffling decisions because these bills have greater policy significance. The authors also explain that lawmakers are more likely to choose to waffle when the content of a bill has changed throughout the legislative process, from the time the cosponsor agrees to sign on to the bill. In other words, if the original content of the bill is not significantly modified, the decision to waffle is influenced by whether or not the bill is amended, as lawmakers do not have to take on the risk of violating trust among their colleagues.

Why is analyzing lawmakers’ waffling in South Korea important?

Analyzing waffling behavior among lawmakers in the South Korean National Assembly provides crucial insights into representative behavior and strategic legislative behavior. The institutional structure and political culture of South Korea present both contrasts and parallels with the US Congress, providing a unique context for extending and refining theories of waffling.

First, the Korean National Assembly operates under a mixed system of district-based and proportional representation, a structural feature that allows for comparative analysis of waffling behavior across two distinct types of lawmakers. District-based lawmakers are typically more responsive to the pressures of their local constituencies, while proportional representatives often act in alignment with party platforms. This dual system creates a valuable opportunity to examine how different institutional incentives shape legislative strategies and patterns of waffling, particularly in their approach to balancing local accountability and partisan loyalty.

Second, another distinctive feature is South Korea’s committee chair allocation system. In Korea, committee chairs are allocated based on inter-party negotiations reflecting the proportional distribution of legislative seats. Consequently, both majority and minority parties hold committee leadership positions, offering a distinctive opportunity to analyze how variations in committee control influence waffling behavior. For instance, lawmakers’ strategic shifts may differ depending on whether the committee is led by the majority or the minority party, illuminating the role of institutional authority in shaping legislative decision-making.

At the same time, the political systems of South Korea and the United States share notable similarities. Both countries exhibit increasingly polarized party systems dominated by two major parties, where partisan loyalty often overshadows individual lawmakers’ autonomy. Furthermore, just as US politics is marked by state-level partisan alignments, South Korean politics is heavily influenced by region-based partisan divides. These regional cleavages exert substantial influence on lawmakers’ behavior, particularly in balancing national party interests and regional demands.

In this context, studying lawmakers’ behavior in South Korea has two significant implications. First, as the US debates various reforms to enhance legislative representation and efficiency, South Korea’s experience offers meaningful comparative insights. Second, applying waffling theory—predominantly developed in the US context—to South Korea’s institutional environment can reveal how lawmakers’ strategic behaviors adapt to different institutional contexts, potentially leading to variations in both the frequency and nature of waffling behavior.

Theoretical Expectations

Previous studies have analyzed that main sponsors of bills are less likely to waffle than co-sponsors (Kirkland and Harden Reference Kirkland and Harden2016; Kang and Park 2022). This is because main sponsors are more responsible and committed to the passage of the bill than co-sponsors, and their attachment to the bill is greater. The act of main sponsorship implies not only support for the bill’s content but also a commitment to work towards its passage, creating stronger incentives for maintaining consistent positions throughout the legislative process (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013). Co-sponsors, on the other hand, often align themselves strategically rather than substantively, making their support more contingent and less stable (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1995). This distinction highlights the structural incentives behind sponsorship roles in shaping legislative behavior. Therefore, we set the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Main sponsors of bills will be less likely to engage in waffling than co-sponsors.

Previous studies that have analyzed the relationship between bill amendments and waffling have found that the likelihood of waffling increases when a bill is amended at the committee stage compared to when it is not (Kirkland and Harden Reference Kirkland and Harden2016; Kang and Park 2022). We argue that the likelihood of waffling is lower when a bill is passed out of committee as originally introduced by the legislator, and the likelihood of waffling is higher when it is amended or substituted and sent to the floor as a chairman’s substitute because the original text is amended. Such amendments often reflect competing priorities within the legislative process, leading to a loss of attachment and reduced accountability for the bill’s original sponsors (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013). Also, empirical evidence from the Korean National Assembly demonstrates that substantial modifications at the committee stage, particularly through chairman’s substitutes, significantly increase the likelihood of both dissent waffling and strategic waffling through abstention or absence (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022; Kang and Park 2022).

Hypothesis 2: Legislators will be more likely to engage in waffling when a bill is amended in a standing committee and sent to the floor than when it is not.

Legislator’s personal attributes

In the United States, waffling often occurs when a lawmaker’s preferences conflict with their party preferences, and is particularly prevalent among members of the majority party (Kirkland and Harden Reference Kirkland and Harden2016). They attribute this to the fact that the majority party leadership wields significant power and agenda-setting authority. Since majority party leaders frequently amend or restructure bills to reflect party-wide priorities (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005), majority party sponsors may become dissatisfied if the revised version no longer aligns with their policy views or their constituents’ interests. Compared to minority party sponsors, majority party sponsors are more directly implicated in the policy output and therefore bear greater reputational risk for supporting legislation that has significantly changed. At the same time, majority party legislators often enjoy stronger electoral security and institutional support, giving them more latitude to reverse course without facing immediate electoral punishment (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013).

On the other hand, Kang et al. (Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022) found that in the 20th National Assembly, members of the minority party (Liberty Korea Party and the National People’s Party) were more likely to engage in waffling than members of the majority party (Democratic Party). This is because, unlike the US Congress, the Korean National Assembly does not allow the majority party to dominate the standing committee chairs and thus has less agenda-setting power. Kang and Park (2022) also find that bills are often amended at the standing committee stage to closely match the majority party’s preferences and that minority lawmakers are more likely to engage in waffling as a sign of dissatisfaction and consensus. Additionally, minority legislators often use waffling as a strategy to voice opposition to majority-led legislative outcomes, reflecting an institutional imbalance in power (Ka et al. Reference Ka, Kang and Park2021). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 3: Minority party’s legislator will be more likely to engage in waffling than majority party’s legislator.

Existing studies show that lawmakers with extreme ideology are more likely to engage in waffling than lawmakers with moderate ideology that are likely to compromise policies (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022). Extremist lawmakers are likely to withdraw their support if the bill is revised differently from their preferences at the standing committee stage. Therefore, the following hypothesis is established. The higher propensity of ideological extremists to waffle reflects their prioritization of policy purity over legislative compromise, even when it undermines coalition-building efforts (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1995). Furthermore, Miller and Overby (Reference Miller and Overby2010) argue that waffling by ideologically extreme legislators reflects a strategic focus on securing favorable vote outcomes, despite the potential risks of appearing inconsistent. Therefore, we set the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: The more ideologically extreme lawmakers will be more likely to engage in waffling.

According to studies in Korea and the United States, the influence of seniority on the legislative behavior of lawmakers appears in different directions. While American lawmakers participate more in bill proposals the higher their seniority (Hibbing Reference Hibbing1991), Korean lawmakers participate less in bill proposals the higher their seniority (Choi Reference Choi2006). Likewise, in the case of waffling, the higher the seniority of a member of the US House of Representatives, the higher the possibility of waffling (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013), but in South Korea, the lower the seniority of a member of the National Assembly, the higher the possibility of (strategic) waffling (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022). Kang et al. (Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022) argue that this result is because lower-ranked lawmakers are mobilized for co-sponsorship at the request of their fellow lawmakers, but avoid supporting burdensome bills at the voting stage. Junior lawmakers are often more vulnerable to external pressures, including requests for co-sponsorship from senior colleagues, making their support for controversial bills more conditional (Chang Reference Chang2011; Kang and Park 2022). These dynamics underscore the interplay between institutional hierarchies and legislative decision-making.

Hypothesis 5: The lower the seniority of lawmakers, the more likely they are to choose waffling.

Waffling is most likely to occur when there is pressure from the party leadership or when personal preferences conflict with party preferences (Miller and Overby Reference Miller and Overby2010, Reference Miller and Overby2014; Kirkland and Harden Reference Kirkland and Harden2016). Leadership positions could require greater accountability and alignment with the party’s legislative priorities, which discourages inconsistent behavior during roll-call votes. This consistency could be reinforced by the visibility of leadership members in shaping legislative outcomes. Thus, we argue that members of the party standing leadership are less likely to engage in waffling because they are more likely to be close to the party’s preferences. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 6: Lawmakers who hold standing positions in the National Assembly will be less likely to engage in waffling compared to lawmakers who do not hold leadership positions.Footnote 1

Research Design

Data

This study focuses on conflict bills introduced in plenary sessions from the 17th to the 20th National Assembly. The 17th National Assembly is the first National Assembly for which plenary votes are publicly available from the beginning of the session. The comprehensive analysis allows us to examine the difference between waffling when a party is in the majority and when it is in the minority. We can also show differences in waffling behavior across party systems. Existing studies have argued that legislators’ voting behavior differs between multiparty systems and a two-party systems (Moon Reference Moon2011), and that compromise in the legislative process also differs (Lijphart et al. Reference Lijphart, Pintor, Sone, Grofman and Lijphart1986; Park and Lee Reference Park and Lee2019). In addition, this study limits the scope of analysis to conflict bills with less than 90 percent approval in the plenary vote. The definition of conflict bills varies from researcher to researcher, but looking at previous studies on conflict bills, Jeon (Reference Jeon2006) defines conflict bills as bills with less than 95.8 percent of votes in favor of individual bills. In addition, recent studies that analyzed the waffling behavior of lawmakers through conflict bills in the 20th National Assembly (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022; Kang and Park 2022) defined conflict bills as bills with an approval rate of less than 90 percent, arguing that bills that are sent to the plenary from standing committees are usually passed with a high approval rate in the plenary because they are generally agreed upon at the standing committee stage.Footnote 2

As defined in this study, the number of conflict bills was 101 in the 17th National Assembly, 90 in the 18th National Assembly, 153 in the 19th National Assembly, and 180 in the 20th National Assembly. The unit of analysis was set as a bill-legislator. By multiplying the number of conflict bills in each National Assembly by the number of lawmakers who co-sponsored each bill, the final number of cases (N) for this study was 6222 for the 17th National Assembly, 3577 for the 18th National Assembly, 6195 for the 19th National Assembly, and 5522 for the 20th National Assembly.

This study employs a multilevel analytical approach to comprehensively examine waffling behavior in the Korean National Assembly. We utilize multilevel logistic regression with random intercepts for legislators, bills, and legislative terms to account for the hierarchical structure of our data across all four legislative terms (17th–20th). This methodological approach allows us to properly handle the nested nature of the data—where multiple observations are clustered within legislators, bills are processed across different periods, and legislators serve across multiple terms—while providing more accurate standard errors and richer insights into the sources of variation in waffling behavior.

Our analysis examines four distinct outcome variables: overall waffling and its three component types—dissent waffling (voting against), abstention waffling, and no-show waffling (strategic absence). This disaggregated approach allows us to uncover how different forms of waffling represent distinct strategic choices with varying political costs and signals. The multilevel framework enables us to partition variance across different levels of analysis, revealing the relative importance of individual legislator characteristics, bill-specific factors, and period effects in shaping waffling decisions.

Furthermore, we conduct subsample analyses examining waffling patterns in majority-controlled versus minority-controlled committees to investigate how institutional power arrangements influence legislative behavior. These focused analyses isolate the effects of committee control and provide crucial insights into how the distribution of institutional authority shapes different forms of waffling. Additionally, period-specific analyses examining each National Assembly term separately are provided in the Appendix (Table A-4, A-5, and A-6) to capture temporal variations and evolving political contexts. By employing this comprehensive analytical strategy, we can identify general patterns of waffling behavior while accounting for the complex, nested structure of legislative decision-making in the Korean context.

Variables

The dependent variable in this study is whether legislators make waffling decisions on conflict bills. Waffling can be strongly manifested in the form of a negative vote in a plenary vote, but it can also be manifested in the form of strategic waffling through abstention or no-show. Therefore, we categorize waffling through ‘nay’ into waffling, strategic waffling (abstention), and strategic waffling (no-show), and set these three as the dependent variables. We measure ‘waffling’ as 1 if a legislator sponsored (or co-sponsored) an individual bill but voted against it on the floor, and 0 otherwise. Strategic waffling (abstention) is measured as 1 if a legislator participated in the (co)sponsorship but abstained from the vote, and 0 otherwise. The strategic waffling (absent) variable is measured as 1 if the legislator participated in the (co)sponsorship but did not participate in the floor vote and 0 otherwise. The bill sponsorship and voting records of legislators are collected from the National Assembly Bill Information System. Since the dependent variable is measured as binary, we use logistic regression to analyze the determinants of legislators’ waffling behavior.

In order to test the hypotheses of the study, legislators’ party affiliation, ideological extremity, seniority, and standing committee leadership are included in the models. Party affiliation is measured by the time the lawmaker participated in the bill, and the reference category is the minority party in each National Assembly. Ideological extremity is measured by estimating W-NOMINATE, a measure of legislators’ ideology based on their plenary voting records in the US Congress and the Korean National Assembly (Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal1991, Reference Poole and Rosenthal1997; Lee and Lee Reference Lee and Lee2015; Koo et al. Reference Koo, Choi and Kim2016). It is a continuous variable with a value of -1 for the most liberal legislator and +1 for the most conservative legislator and takes an absolute value to measure the ideological extremity of the legislator. The seniority measures the number of times a legislator has been elected. Standing committee leadership position is measured as 1 if the sponsor of the bill is a standing committee chairman, or standing committee secretary at the time of the bill’s introduction, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 3

At the bill level, the independent variables are whether the bill was amended in committee, main sponsorship, and whether the sponsor’s standing committee is the same as the standing committee in charge of the bill. Committee amendment is measured by whether the bill was passed in committee as original (Approved), passed with amendments (Amendment), and was moved to the floor by the chair as a consolidated bill (Alternative). The data is collected through the National Assembly Bill Information System and is measured as 1 if the bill is in one of the three cases and 0 otherwise. In the regression model, the reference category is set to pass the original draft. Main sponsorship is measured as 1 if a member of the National Assembly takes the lead in proposing a bill, and 0 otherwise. Standing committee congruence is measured as 1 if the sponsor’s committee is the same as the committee in charge of the bill, and 0 otherwise.

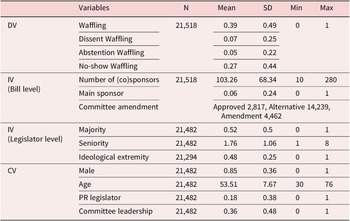

Control variables: To estimate more robustly the impact of the independent variables on legislators’ waffling behavior, the gender, age, and elected type of legislators are set as control variables (Choi Reference Choi2006; Kang and Ka Reference Kang and Ka2020; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022). Using information from the Constitutional Assembly of the Republic of Korea website, gender is measured as 1 for male legislators and 0 for female legislators. Age is measured as the age of the legislator at the time of the opening of the National Assembly. Elected type is measured as 1 for district legislators and 0 for proportional representation legislators. Descriptive statistics of the study variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (17th~20th)

Results

Multilevel Analysis of Waffling Behavior

The multilevel analysis of waffling behavior across the four National Assemblies (17th–20th) reveals several significant patterns that both support and extend our theoretical expectations. Using multilevel logistic regression with random intercepts for legislators, bills, and legislative terms, we account for the hierarchical structure of our data while examining four distinct types of waffling behavior: overall waffling, dissent waffling (nay votes), abstention waffling, and no-show waffling.Footnote 4

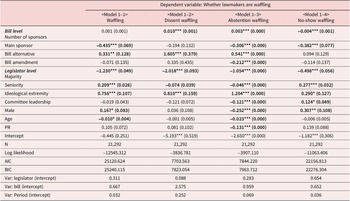

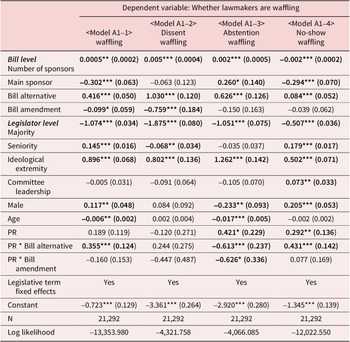

Table 2 presents the multilevel regression results examining how bill and legislator characteristics affect different types of waffling behavior. At the bill level, we find nuanced variations in how bill characteristics affect different types of waffling. The number of sponsors shows a positive relationship with dissent (p<0.001) and abstention waffling (p<0.001), but a negative relationship with no-show waffling (p<0.001). This pattern contradicts Bernhard and Sulkin’s (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) expectation that bills with more cosponsors would be considered more “commemorative” and thus less likely to provoke waffling. Instead, our findings suggest that in the Korean context, widely supported bills may undergo more substantial modifications during committee deliberations to accommodate diverse interests, thereby increasing the likelihood of explicit forms of waffling. The negative relationship with no-show waffling aligns with theoretical expectations about reputational costs—legislators appear reluctant to be absent from votes on highly visible, widely supported legislation.

Table 2. Multilevel logistic regression results for waffling

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Standard errors in parentheses. Three-level hierarchical models with random intercepts estimated for legislators (Level 1: n=790), bills (Level 2: n=413), and National Assembly periods (Level 3: n=4). N=21,292 observations.

Main sponsorship significantly reduces overall waffling (p<0.001) and no-show waffling (p<0.001), while also decreasing abstention waffling (p<0.001), strongly supporting our first hypothesis and confirming findings from both US studies (Kirkland and Harden Reference Kirkland and Harden2016) and recent Korean research (Kang and Park 2022). This indicates that primary sponsors maintain stronger commitment to their bills throughout the legislative process, consistent with Bernhard and Sulkin’s (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) argument that main sponsorship implies not only support for the bill’s content but also a commitment to work towards its passage.

The treatment of bills in committee reveals critical insights that strongly support our second hypothesis. Bills passed as alternatives significantly increase the likelihood of overall waffling (p<0.01) and are particularly influential for dissent waffling (p<0.001) and abstention waffling (p<0.001). This finding aligns with both US research (Kirkland and Harden Reference Kirkland and Harden2016) and Korean studies (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022; Kang and Park 2022), confirming that substantial bill modifications through chairmans’ substitutes create distance between sponsors’ original intentions and the final legislative product. The magnitude of the effect on dissent waffling is particularly striking, supporting Bernhard and Sulkin’s (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) argument that changes to bill content throughout the legislative process significantly influence waffling decisions. Interestingly, bill amendments show no significant effects across most models, with only abstention waffling showing a negative relationship (p<0.001), suggesting that minor modifications may be better tolerated by sponsors than wholesale replacements—a nuance not captured in previous studies that often treat all modifications uniformly.

At the legislator level, our findings provide robust support for the distinctive characteristics of waffling in the Korean institutional context while challenging US-based theories. The majority party variable shows consistently strong negative coefficients across all models (p<0.001), confirming our third hypothesis and supporting recent Korean studies (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022; Kang and Park 2022) that minority party members are significantly more likely to engage in all forms of waffling behavior. This finding stands in stark contrast to US congressional studies where Kirkland and Harden (Reference Kirkland and Harden2016) found that majority party members waffle more frequently due to their agenda-setting power and the pressures that come with it. The reversal in the Korean context underscores how different institutional arrangements—particularly the proportional distribution of committee chairs and the lack of negative agenda control by the majority party—create fundamentally different incentive structures for legislative behavior.

Ideological extremity maintains strong positive relationships with most types of waffling (p<0.05), providing robust support for our fourth hypothesis and confirming findings from both US (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013; Miller and Overby Reference Miller and Overby2010) and Korean contexts (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022). The effect is particularly pronounced for abstention waffling (p<0.001), extending Miller and Overby’s (Reference Miller and Overby2010) argument that extreme legislators prioritize vote outcomes over consistency concerns. Our findings suggest that ideologically extreme legislators in Korea strategically choose abstention as a middle-ground option that registers dissatisfaction without the reputational costs of direct opposition—a strategic nuance not fully explored in previous literature.

The seniority variable presents a theoretically interesting pattern that supports our fifth hypothesis about the reverse seniority effect in Korea. It significantly increases overall waffling (p<0.001) and no-show waffling (p<0.001), while showing a small negative effect on abstention waffling (p<0.001). This pattern contrasts sharply with US findings, where Bernhard and Sulkin (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) found that higher seniority increases waffling due to greater electoral security. Instead, our results align with Kang et al.’s (Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022) findings that Korean junior legislators are mobilized for co-sponsorship at the request of their colleagues but avoid supporting burdensome bills at the voting stage. The positive effect on no-show waffling among senior members suggests they leverage their institutional security differently than their US counterparts—choosing strategic absence over explicit opposition.

Committee leadership shows limited effects, partially supporting our sixth hypothesis. The negative effect on abstention (p<0.001) and positive effect on no-show waffling (p<0.05) suggest that committee leaders navigate their dual roles carefully, avoiding ambiguous signals like abstention while potentially using absence as a less visible form of protest. This finding extends the literature on leadership positions and legislative behavior by revealing how institutional positions create different strategic options for expressing dissent.

Control variables reveal additional insights that complement existing research. Male legislators show a higher propensity for overall waffling (p<0.05) and no-show waffling (p<0.01) but significantly lower likelihood of abstention waffling (p<0.001), suggesting gender-based differences in strategic choice among waffling options not previously explored in the waffling literature. Age shows negative relationships with overall waffling (p<0.05) and abstention waffling (p<0.001), aligning with general expectations about established legislators maintaining more consistent voting patterns due to clearer policy positions and established reputations.

The variance components reveal important insights into the hierarchical structure of waffling behavior that extend methodological approaches in legislative studies. The relatively high variance at the bill level (ranging from 0.652 to 2.575) indicates substantial bill-specific factors influencing waffling decisions, particularly for dissent waffling, supporting the importance of examining bill characteristics as emphasized by Bernhard and Sulkin (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013). The moderate legislator-level variance confirms individual heterogeneity in waffling propensity, while the lower variance at the legislative term level suggests that period effects, while present, are less influential than individual and bill-specific factors—a finding that validates our pooled analysis approach while accounting for temporal variations.

These findings provide strong empirical support for our theoretical framework while revealing the complex, multifaceted nature of waffling behavior in the Korean National Assembly. By demonstrating that waffling is not a monolithic phenomenon but rather a strategic choice among distinct options, each carrying different political costs and signals, we extend Kirkland and Harden’s (Reference Kirkland and Harden2018) conceptualization of waffling as legislative indecision. The stark contrast with US findings, particularly regarding majority party behavior, highlights the importance of institutional context in shaping legislative strategies and supports calls for more comparative research on legislative behavior across different democratic systems. Our multilevel approach successfully captures the nested structure of the data while providing more conservative estimates that strengthen confidence in our conclusions about the systematic nature of waffling behavior in Korean legislative politics.

Waffling Dynamics Under Majority-Controlled Committee

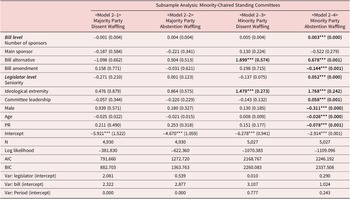

Table 3 presents the results of subsample analyses examining how waffling behavior differs between majority and minority party legislators specifically within majority-chaired standing committees. This focused analysis allows us to isolate the effects of committee control on legislative behavior and provides crucial insights into how institutional power dynamics shape different forms of waffling, extending the work of Cox and McCubbins (Reference Cox and McCubbins2005, Reference Cox and McCubbins2007) on majority party agenda control to the Korean context.

Table 3. Differential waffling patterns by party affiliation in majority-chaired standing committees

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Standard errors in parentheses. Three-level hierarchical models with random intercepts estimated for legislators (Level 1: n=519; 518), bills (Level 2: n=174; 182), and National Assembly periods (Level 3: n=4).

At the bill level, we observe stark contrasts in how bill characteristics influence waffling behavior across party lines. The number of sponsors variable shows a significant positive effect on dissent waffling for minority party members (p<0.001) but no significant effect for majority party members. This finding contradicts Bernhard and Sulkin’s (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) expectation about “commemorative” bills with many cosponsors showing less waffling, but aligns with Kang and Park’s (2022) findings in the Korean context. The pattern suggests that minority party legislators are more likely to vote against bills with broader sponsorship when those bills are processed through majority-controlled committees, possibly reflecting their frustration with modifications that align with majority preferences despite widespread initial support—a dynamic not present in the US Congress where majority party control is more absolute.

The impact of bill modifications reveals particularly illuminating patterns that extend existing theoretical frameworks. For minority party members, bills passed as alternatives show a dramatically strong positive effect on dissent waffling (p<0.001), while no significant effect is observed for majority party members. This finding powerfully demonstrates how chairman’s substitutes in majority-controlled committees create substantial distance between minority sponsors’ original intentions and the final legislative product, strongly supporting both our hypothesis and recent Korean studies (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022; Ka et al. Reference Ka, Kang and Park2021). The magnitude of this effect—among the largest in our entire analysis—goes beyond what Kirkland and Harden (Reference Kirkland and Harden2016) observed in the US context, underscoring the profound impact of committee control on minority party legislative behavior in consensus-based systems. Similarly, bill amendments show a significant positive effect on minority party dissent waffling (p<0.001) but no effect for majority party members, further reinforcing Kang and Park’s (2022) argument that bills are often amended at the standing committee stage to closely match majority party preferences.

Main sponsorship shows a significant negative effect only for minority party dissent waffling (p<0.001), confirming our first hypothesis and extending findings from both US (Kirkland and Harden Reference Kirkland and Harden2016) and Korean contexts (Kang and Park 2022). This indicates that minority party members who serve as main sponsors maintain stronger commitment to their bills even when processed through majority-controlled committees, aligning with Bernhard and Sulkin’s (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) theoretical expectations about the heightened accountability associated with primary sponsorship.

At the legislator level, the results reveal how individual characteristics differently influence waffling behavior depending on party affiliation within majority-controlled committees, providing new insights into Kirkland and Harden’s (Reference Kirkland and Harden2018) framework of competing principals. Ideological extremity shows significant positive effects for both parties’ abstention waffling (majority: β=1.541, p<0.1; minority: β=1.629, p<0.001), but only affects minority party dissent waffling (p<0.001). This pattern extends Miller and Overby’s (Reference Miller and Overby2010) findings about ideological extremists prioritizing vote outcomes, suggesting that while ideological extremists in both parties may choose abstention as a moderate form of protest, only minority party extremists resort to explicit opposition through negative votes when their bills are processed through majority-controlled committees—a nuance not captured in US studies where majority party control is more comprehensive.

The seniority variable shows a significant negative effect only for minority party dissent waffling (p<0.001). This contrasts sharply with Bernhard and Sulkin’s (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) US findings where senior legislators waffle more due to electoral security. The Korean pattern indicates that junior minority party members are more likely to vote against their sponsored bills in majority-controlled committees, supporting the argument that they face greater cross-pressures and may be mobilized for co-sponsorship without genuine commitment to the bill’s passage (Chang Reference Chang2011).

Committee leadership presents an intriguing asymmetry that extends our understanding of institutional positions and legislative behavior: it significantly reduces dissent waffling for majority party members (p<0.05) but shows a positive effect for minority party members (p<0.001). This reversal goes beyond existing theories about leadership positions (Cox and Terry Reference Cox and Terry2008) and suggests that committee leadership positions function differently across party lines within majority-controlled committees. Majority party committee leaders appear to maintain party discipline and avoid explicit opposition, consistent with Cox and McCubbins’s (Reference Cox and McCubbins2005) arguments about party leadership roles, while minority party committee leaders may use their institutional position to voice dissent more freely—a dynamic unique to consensus-based systems.

Demographic variables reveal additional nuances not previously explored in the waffling literature. The gender effect is significant only for majority party abstention waffling (p<0.05), with male majority party legislators being less likely to abstain, suggesting gender-based differences in strategic choices that warrant further investigation. The absence of significant age and PR effects contrasts with some findings in the pooled analysis, indicating that these factors’ influence may be context-dependent.Footnote 5

These findings provide compelling evidence for how institutional power dynamics shape legislative behavior in the Korean National Assembly, extending and challenging existing theoretical frameworks. The dramatic differences in waffling patterns between majority and minority party members within majority-controlled committees underscore Cox and McCubbins’s (Reference Cox and McCubbins2007) arguments about the importance of committee control in legislative politics, but in ways that differ from their US-based predictions. Unlike the US Congress, where majority party members face higher waffling pressures due to their agenda-setting responsibilities (Kirkland and Harden Reference Kirkland and Harden2016), Korean minority party members face substantially higher incentives to waffle, particularly through dissent voting, when their bills are modified in committees controlled by the majority party.

The results also demonstrate that party affiliation fundamentally alters how individual legislator characteristics influence waffling behavior, supporting Kirkland and Harden’s (Reference Kirkland and Harden2018) argument about the complexity of legislative decision-making under competing pressures. While some factors like ideological extremity show similar effects across parties as predicted by existing theory (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013; Miller and Overby Reference Miller and Overby2010), others like committee leadership and seniority operate in opposite directions, highlighting the complex interplay between institutional position and individual attributes in shaping legislative strategies. These findings contribute to our theoretical understanding of how consensus-based institutional features, such as proportional committee chair distribution, create unique dynamics for legislative behavior that differ markedly from majoritarian systems like the US Congress, calling for more nuanced theoretical frameworks that account for institutional variation across democratic systems.

Waffling Dynamics Under Minority-Controlled Committees

Table 4 presents the results of subsample analyses examining waffling behavior in minority-chaired standing committees. This analysis reveals markedly different patterns from those observed in majority-controlled committees, offering important insights into the strategic calculations legislators make under varying institutional power arrangements and extending the theoretical frameworks developed by Cox and McCubbins (Reference Cox and McCubbins2005, Reference Cox and McCubbins2007) to consensus-based legislative systems.

Table 4. Differential waffling patterns by party affiliation in minority-chaired standing committees

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Standard errors in parentheses. Three-level hierarchical models with random intercepts estimated for legislators (Level 1: n=503; 509), bills (Level 2: n=196; 193), and National Assembly periods (Level 3: n=4).

At the bill level, the effects of bill characteristics show notable contrasts between majority and minority party members within minority-controlled committees. The number of sponsors variable shows a significant positive effect only for minority party abstention waffling (p<0.001), while showing no significant effects for other models. This selective impact contrasts with Bernhard and Sulkin’s (Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) expectations about broadly supported bills but aligns with the complexity of coalition-building in consensus systems described by Lijphart et al. (Reference Lijphart, Pintor, Sone, Grofman and Lijphart1986). Within their own committee domains, minority party members may use abstention as a strategic tool when bills gain broader support, possibly reflecting internal party disagreements about widely supported legislation—a dynamic not captured in US studies where committee control typically ensures party cohesion.

The impact of bill modifications reveals particularly striking patterns that extend Kirkland and Harden’s (Reference Kirkland and Harden2016, Reference Kirkland and Harden2018) findings about bill amendments and waffling. For minority party members, bills passed as alternatives show a strong positive effect on dissent waffling (β=1.899, p<0.001) and abstention waffling (β=0.678, p<0.001), while no significant effects are observed for majority party members. This finding challenges the conventional wisdom that committee control ensures favorable outcomes for the controlling party, as suggested by Cox and McCubbins (Reference Cox and McCubbins2005). Even within minority-controlled committees, minority party sponsors face challenges when their bills undergo substantial modifications through chairman’s substitutes. The persistence of this effect even in committees they control indicates that the consensus-building process inherent in the Korean legislative system may still favor majority party preferences during bill consolidation.

Interestingly, bill amendments show a significant negative effect only for minority party members’ abstention waffling (p<0.05), contrasting with findings from both US studies (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) and majority-controlled committees in Korea. This suggests that minor modifications in minority-controlled committees may actually help maintain minority party support by incorporating their concerns without fundamentally altering the bill’s direction—a nuance that extends our understanding of how different types of amendments affect legislative behavior differently across institutional contexts.

At the legislator level, the results reveal how individual characteristics operate differently under minority committee control, providing new insights into the competing principals framework developed by Kirkland and Harden (Reference Kirkland and Harden2018). Ideological extremity maintains its strong positive effect on minority party waffling behavior (dissent: β=1.479, p<0.001; abstention: β=1.768, p<0.001) but shows no significant effects for majority party members. This asymmetry extends Miller and Overby’s (Reference Miller and Overby2010) findings about ideological extremists prioritizing policy outcomes, suggesting that ideological considerations primarily drive minority party behavior even within committees they control. The lack of effect for majority party members contrasts with US findings where ideological extremity consistently predicts waffling (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013). It indicates that majority party members in minority-controlled committees may be more influenced by strategic calculations about maintaining working relationships across committee boundaries.

The seniority variable shows an interesting pattern unique to minority-controlled committees: it significantly increases abstention waffling for minority party members (p<0.001) while showing no effects for other groups. This positive relationship directly contradicts both US findings where senior legislators waffle more across all contexts (Bernhard and Sulkin Reference Bernhard and Sulkin2013) and the negative relationship found in majority-controlled committees. This suggests that senior minority party members may use abstention as a face-saving mechanism when bills processed through their own committees still fail to fully reflect their preferences—a strategic calculation unique to consensus-based systems where maintaining cross-party relationships is crucial for future legislative success.

Committee leadership shows a significant positive effect only for minority party abstention waffling (p<0.001), extending our understanding of how leadership positions influence legislative behavior. Unlike in majority-controlled committees where leadership positions constrain waffling, minority party committee leaders are more likely to abstain from voting on bills processed through minority-controlled committees. This finding suggests a complex dynamic absent from US studies, where committee leaders must balance their institutional responsibilities with party or personal preferences in a system that requires broader consensus-building.

These findings provide compelling evidence that committee control structures create fundamentally different incentive systems for legislative behavior, challenging the straightforward application of US-based theories to other contexts. Unlike Cox and McCubbins’s (Reference Cox and McCubbins2007) predictions about committee control ensuring favorable outcomes for the controlling party, even when minority parties control committees in Korea, they face significant challenges in maintaining party cohesion, particularly when bills undergo substantial modifications. This suggests that the proportional distribution of committee chairs noted by previous studies (Ka et al. Reference Ka, Kang and Park2021; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Park and Ka2022) creates more complex dynamics than simple reversal of majority-minority patterns.

The analysis also demonstrates that the Korean National Assembly’s consensus-based features, as described by Park and Lee (Reference Park and Lee2019), create persistent pressures for accommodation even within minority-controlled committees. The continued tendency for minority party members to waffle on bills processed through their own committees contradicts expectations from majoritarian theories and suggests that institutional control alone cannot overcome the broader dynamics of majority-minority relations in the legislature. These findings extend Kirkland and Harden’s (Reference Kirkland and Harden2018) framework of legislative indecision by showing how consensus-based institutional arrangements create unique patterns of competing pressures that are not present in majoritarian systems, contributing to our understanding of how different institutional arrangements shape legislative behavior and highlighting the importance of developing context-specific theories for comparative legislative studies.

Conclusion

This study makes several significant theoretical and empirical contributions to our understanding of legislative behavior, particularly focusing on the phenomenon of waffling in the context of the South Korean National Assembly. Our findings challenge the direct application of US-based theories of legislative behavior to other institutional contexts and suggest the need for more nuanced, context-specific theoretical frameworks. First, our most striking finding reveals a fundamental difference in waffling patterns between the US Congress and the South Korean National Assembly. While US congressional studies consistently show that majority party members are more likely to engage in waffling behavior (Kirkland and Harden Reference Kirkland and Harden2016), our analysis of the Korean context demonstrates the opposite pattern: minority party members exhibit a higher propensity for waffling. This divergence can be attributed to distinct institutional arrangements and power dynamics. In the US Congress, the majority party’s strong agenda-setting authority and negative agenda control, manifested through their command of all standing committee chairs, creates conditions where majority party members face more pressure points that could lead to waffling (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2007). In contrast, the Korean National Assembly operates under a more consensual system, where committee chairs are distributed proportionally across parties, and the opposition party traditionally holds the chair of the influential Judiciary Committee. This institutional arrangement allows minority parties greater access to the legislative process but simultaneously increases their exposure to potential waffling situations when their bills are substantially modified to align with majority preferences during committee deliberations.

Second, our multilevel analysis provides robust empirical evidence for the systematic nature of waffling behavior in Korean legislative politics. By employing a hierarchical modeling approach that accounts for legislator, bill, and period-level variations, we demonstrate that waffling is not merely an idiosyncratic phenomenon but a systematic feature of legislative behavior that varies predictably with both individual legislator characteristics and institutional factors. The significant variance components at different levels of analysis validate our methodological approach and reveal the complex, nested structure of legislative decision-making.

Third, our comparative analysis of waffling patterns in majority versus minority-controlled committees reveals how committee control structures fundamentally shape legislative behavior. The dramatic differences in waffling patterns between these two institutional contexts—particularly the heightened waffling among minority party members in majority-controlled committees—demonstrate that committee control serves as a critical mechanism through which institutional power translates into legislative outcomes. Notably, even when minority parties control committees, they continue to face challenges in maintaining party cohesion, suggesting that formal institutional control cannot fully overcome the broader dynamics of majority-minority relations in consensus-based systems.

Fourth, our findings regarding the relationship between ideological extremity and waffling behavior contribute to the broader theoretical discussion about the role of ideology in legislative decision-making. The consistent positive correlation between ideological extremity and waffling across all three types suggests that ideological positioning plays a crucial role in legislative behavior, even in a political system that is often characterized as being more focused on regional and personal networks than ideological divisions.

The study also offers several important implications for understanding comparative legislative politics. Our findings suggest that the relationship between institutional structure and legislative behavior is more complex than previously theorized. The contrasting patterns of waffling behavior between the US and South Korean legislatures indicate that similar institutional features (such as committee systems) may function differently depending on the broader political context and institutional arrangements. The persistent challenges minority parties face even in committees they control highlight the importance of considering both formal institutional rules and informal power dynamics in understanding legislative behavior.

These contributions not only advance our theoretical understanding of legislative behavior but also have practical implications for institutional design in democratic systems. The findings suggest that efforts to enhance legislative effectiveness should consider how institutional arrangements influence strategic behavior patterns among legislators, particularly in the context of majority–minority party dynamics. The complex patterns of waffling behavior revealed in our analysis indicate that institutional reforms aimed at improving legislative representation and accountability must account for the multifaceted ways in which legislators navigate competing pressures and strategic considerations.

For future research, our findings open several promising avenues. First, there is a need for more comparative studies of waffling behavior across different legislative systems, particularly in non-Western democracies. Second, the relationship between different types of waffling and electoral consequences deserves further investigation, especially in systems where voters’ access to legislative information differs from the US context. Finally, the role of committee power distribution in shaping legislative behavior could be examined in other consensus-based systems to test the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, this study significantly advances our understanding of legislative behavior by demonstrating how institutional contexts shape strategic choices of legislators. It challenges the universal application of US-based theoretical frameworks and suggests the need for more nuanced, context-sensitive approaches to studying legislative behavior in different political systems. By revealing the complex interplay between institutional structures, party dynamics, and individual legislator characteristics in shaping waffling behavior, these findings contribute to both the theoretical literature on legislative politics and practical discussions about institutional design in democratic systems.

Acknowledgments

This research was presented at the 2024 Spring Conference of the Korean Association of Party Studies. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Professor Woo Chang Kang for his insightful comments during the conference. We are especially indebted to Professor Sangjoon Ka, who originally suggested the idea of studying waffling behavior in the Korean National Assembly. Without his pioneering insights and generous sharing of this research concept, this study would not have been possible. His continuous guidance and unwavering support throughout this project have been invaluable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (No. 2022S1A5B5A17044493).

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix

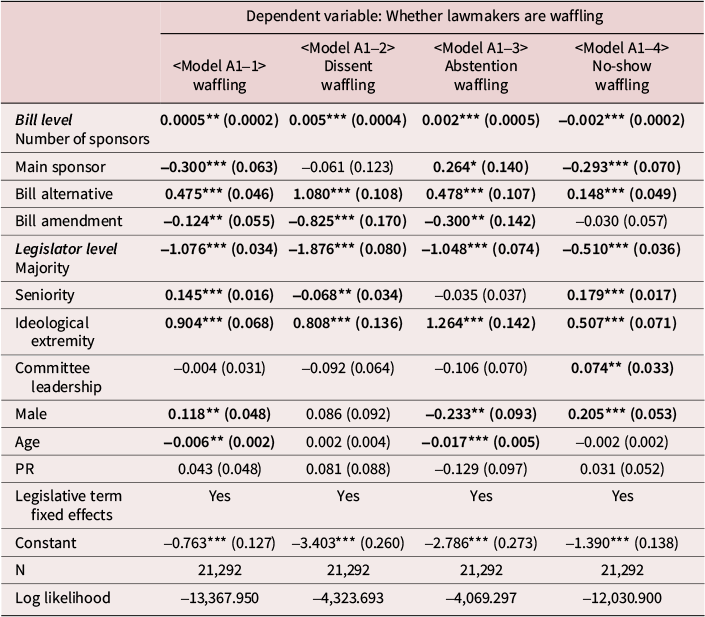

Table A-1. Pooled logistic regression results for waffling

Note: *p<0.1, **p<0.5, ***p<0.01.

Table A-2. Interaction effects between PR status and ideological extremity on legislative waffling

Note: *p<0.1, **p<0.5, ***p<0.01.

Table A-3. Interaction effects between PR status and bill-level variables on legislative waffling

Note: *p<0.1, **p<0.5, ***p<0.01.

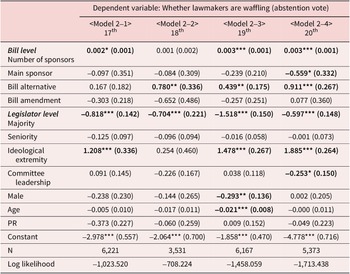

Table A-4. Logistic regression results for dissent waffling by national assembly period: individual analysis of 17th–20th National Assembly (2004–2020)

Note: *p<0.1, **p<0.5, ***p<0.01.

Table A-5. Logistic regression results for strategic waffling through abstention by National Assembly Period: Individual analysis of 17th–20th National Assembly (2004–2020)

Note: *p<0.1, **p<0.5, ***p<0.01.

Table A-6. Logistic regression results for strategic waffling through non-participation by National Assembly period: Individual analysis of 17th–20th National Assembly (2004–2020)

Note: *p<0.1, **p<0.5, ***p<0.01.