We describe a 61-year-old woman with an established diagnosis of seropositive generalized myasthenia gravis (MG) who presented with subacute profound visual loss in one eye, accompanied by severe optic disc edema. Orbital MRI demonstrated enhancement of the long segment of the orbital optic nerve, predominantly involving the optic nerve sheath. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody titers returned as clear positive (titer > 1:100). There are several previously described cases of MG associated with anti-MOG positive disease, which may be due to a shared pathogenetic mechanism involving activation of self-reactive T cells and the persistent presence of MOG-reactive T cells in the peripheral circulation. Reference Bates, Chisholm, Miller, Avasarala and Guduru1,Reference Hurtubise, Frohman and Galetta2 This case demonstrated that MG and MOG antibody-associated disease (MOGAD) may occur together and highlighted similarities in pathogenesis, necessitating the use of treatment modalities that can effectively manage both disorders.

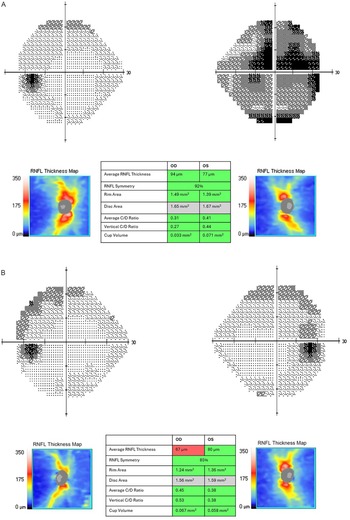

A 61-year-old woman with known history of seropositive MG, controlled with 240 mg of oral pyridostigmine daily and 5 mg of oral prednisone three times per week, presented with new worsening pain on extraocular movements and rapidly worsening vision in the right eye (RE). Visual acuity was light perception in the RE and 20/20 in the left eye (LE), with a marked right relative afferent pupillary defect and severe right disc edema, with several flame-shaped peripapillary hemorrhages. A presumptive diagnosis of severe atypical optic neuritis was made, and treatment with a three-day course of oral prednisone 1250 mg was commenced. Ten days later, the pain had resolved, but visual acuity remained hand motions only. Treatment with 1 g of intravenous Solu-Medrol for five days was commenced. Brain MRI with contrast demonstrated enhancement of the right optic nerve sheath and mild inflammatory stranding and enhancement of adjacent retrobulbar fat in the absence of convincing demyelinating lesions of the brain parenchyma (Figure 1). Vision had not improved; thus, therapy was escalated, and she received seven courses of plasma exchange (PLEX). MOG antibody titers assessed via fixed cell-based assay returned as positive at 1:10 and 1:100 dilutions; AQP4 antibody titers were negative. When examined two weeks after finishing PLEX, vision was 20/200 in RE and 20/30 in LE, with dense right central scotoma on Humphrey visual field testing (Figure 2A). Peripapillary optical coherence tomography (OCT)-measured retinal nerve fiber layer thickness was 94 microns in RE and 77 microns in LE.

Figure 1. Post-contrast axial T1-based image demonstrating long segment of enhancement of the right optic nerve sheath (arrow).

Figure 2. (A) Baseline visual field testing (Humphrey 24-2 algorithm) revealed dense central scotoma on the right with a mean deviation of −17.9 dB. Peripapillary optical coherence tomography (pOCT) showed average retinal nerve fiber thickness of 94 microns in RE and 77 microns in LE. (B) Follow-up visual assessment and imaging at 2 months. Visual field testing shows mild residual temporal defect on the right with a mean deviation of −6.7 dB. pOCT showed thickness of 67 microns in RE and 80 microns in LE.

She continued taking 50 mg of oral prednisone with a taper over the upcoming months, and therapy with azathioprine and monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusions were offered but declined by the patient. Two months later, vision improved to 20/25 in RE and 20/20 in LE. Formal perimetry reassessment demonstrated resolving temporal defect on the right (Figure 2B). Right optic disc edema had been replaced by mild residual pallor.

We describe a patient with longstanding MG who developed severe MOG-related optic neuritis. Concurrent MG and anti-MOG seropositivity have been previously reported in anti-AQP4 positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), and infrequently in MOGAD, which is a distinct entity. Reference Bates, Chisholm, Miller, Avasarala and Guduru1,Reference Roy, Joshi, Ali and Udani3,Reference Cobo-Calvo, Sepúlveda and Bernard-Valnet4 A systematic review conducted by Molazadeh et al. further suggested that immunological comorbidities such as MG occur less frequently in MOGAD than NMOSD, and this association may warrant further investigation into shared pathophysiologic mechanisms of these conditions, which we herein describe. Reference Molazadeh, Bose, Lotan and Levy5

MG is an autoimmune channelopathy that targets components of the neuromuscular junction, most commonly AChR. Autoimmunity is thought to be multifactorial, and contributory factors include human leukocyte antigen genetic predisposition and reduced autoimmune regulator transcription factor expression, medication-induced de novo autoimmunity (checkpoint inhibitors, penicillamine, interferon, some statins, etc.) and thymic abnormalities that impair negative selection, such as thymoma or thymic hyperplasia. Reference Dresser, Wlodarski, Rezania and Soliven6 Thymus cells are known to express AChR and other muscle tissue proteins, enabling aberrant presentation of autoantigens to naïve CD4+ T cells to generate autoreactive T cells, culminating in the activation of autoantibody-producing plasma cells.

Similar to MG, MOGAD is thought to be driven by a T cell-mediated process that generates peripheral autoantibodies against a CNS protein (MOG). Central tolerance to MOG may not be well-established in the thymus, enabling some autoreactive CD4+ T cells to evade negative selection. Reference Corbali and Chitnis7 Infectious prodromes have also been associated with MOGAD, as viral proteins may promote molecular mimicry of MOG and cause bystander activation of antigen-presenting and effector immune cells. Reference Corbali and Chitnis7 MG and MOGAD both arise from a breakdown of central and/or peripheral autoimmune tolerance mechanisms. Reference Hurtubise, Frohman and Galetta2 Centrally, thymic hyperplasia may cause aberrant negative selection of autoreactive CD4+ T cells. The most common autoimmune disease associated with thymic dysfunction is seropositive AChR-Ig MG, but MOGAD has also been reported in association with thymic dysfunction. Reference Hurtubise, Frohman and Galetta2,Reference Corbali and Chitnis7 As the mediastinum and thymus are not conventionally imaged in the management of central nervous system demyelinating diseases, the association between thymic abnormalities and MOGAD may be underreported. While impaired peripheral regulatory T cell function and increased expression of poly-/autoreactive B cell receptors contribute to MG pathogenesis, a failure of peripheral tolerance mechanisms is more commonly associated with MOGAD; aberrant regulatory T cells and interleukins and activation of autoreactive T and B cells occur due to peripheral self-antigen exposure, infectious prodrome and environmental triggers. Reference Dresser, Wlodarski, Rezania and Soliven6,Reference Corbali and Chitnis7 Following autoreactive activation of T cells, both MG and MOGAD feature a predominantly T cell-mediated antibody response. Autoantibody generation is orchestrated primarily in thymic ectopic germinal centers in seropositive AChR-Ig MG compared to peripheral lymphoid tissues in MOGAD. Reference Dresser, Wlodarski, Rezania and Soliven6,Reference Corbali and Chitnis7 Shared mechanisms of immune intolerance in MG and MOGAD may predispose patients with one disease to be at higher risk of another. While the use of satralizumab, a monoclonal antibody against IL-6, and rozanolixizumab, a monoclonal antibody against human neonatal Fc receptor, is currently being explored for treatment of MOGAD, these medications are approved for treatment of MG; thus, they might represent a good choice for patients with both diseases. In addition, while the use of IVIG in MOGAD has been supported by observational evidence, it is a well-known treatment for MG, and again can be considered as a unifying treatment for both diseases.

In summary, we describe a woman with MG who developed severe MOG-related optic neuritis while MG was well-controlled on a longstanding immunosuppression regimen. MG and MOGAD may share common features in pathogenesis and occur in the same patient concurrently. While several treatments for these conditions overlap, more potent combinations of therapies may be needed for immunologic quiescence when both diseases are present, compared to when either disease occurs in isolation.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the preparation/writing and editing of this manuscript.

Funding statement

This work did not receive any funding.

Competing interests

None of the authors.