Introduction

In recent years, the use of social media has increased and become an important platform for political communication. Although social media constitutes a key avenue for citizens to engage in public debates and criticize those in power, it also comes with the potential for online abuse of political actors. Recent research has demonstrated how politicians are subject to online abuse, often including slurs, insults, and sexism in comments on social media (Bjarnegård et al., Reference Bjarnegård, Håkansson and Zetterberg2022; Håkansson, Reference Håkansson2021; Theocharis et al., Reference Theocharis, Barberá, Fazekas and Popa2020; Ward & McLoughlin, Reference Ward and McLoughlin2020). These types of social media comments are highly problematic because they threaten core democratic processes by deterring politicians from expressing their views and engaging in political discussions. Research also indicates that online abuse negatively impacts politicians’ mental health and well-being (Collignon & Rüdig, Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020; James et al., Reference James, Sukhwal, Farnham, Evans, Barrie, Taylor and Wilson2016), and it affects women and marginalized groups disproportionately (Maier & Renner, Reference Maier and Renner2018), which may exacerbate unequal representation in politics. Although harassment in the street, during public debates or in other physical settings is important, online abuse on social media seem particularly problematic because it is the predominant form of abuse experienced by politicians (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Petersen, Kristensen, Houlberg and Pedersen2021) and because the online aspect of it amplifies the potential amount of bystanders observing the abuse. Thus, democratic societies face a key challenge in handling online abuse of politicians and developing effective strategies to counter it.

While researchers have provided some insights into how politicians perceive online abuse (Collignon & Rüdig, Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020; Kosiara-Pedersen, Reference Kosiara‐Pedersen2023), we know little about when negative messages that target politicians are perceived by citizens as being abusive. The lack of research in this field is surprising for at least three reasons. First, citizens can potentially play a direct role in countering online abuse. They can moderate online content either by reporting abusive messages to social media platforms or by engaging in counter-speech to support targeted politicians. In this way, citizens’ perceptions of what constitutes acceptable criticism or abusive messages partly help determine the tone in political debates on social media platforms. Second, citizens’ perception of online abuse and the state of public discourse may be important to politicians’ will to regulate against it. Thus, as with other political issues, public opinion plays a pivotal role in the decision making of political leaders (Burstein, Reference Burstein2003). Citizens’ perceptions about whether or not politicians should be able to tolerate insults, sexist remarks, and threats are therefore key to understanding whether, and by which means, politicians might seek to regulate online abusive behaviour. Finally, citizens are themselves potential participants in politics, and there may be noteworthy variations in how different groups of citizens perceive online abuse. If certain groups perceive negative messages as being more abusive than others, these groups may tend to refrain from political activities. In the long run, representation might be at stake, and examining how different groups of citizens perceive negative messages is therefore relevant when trying to identify potential causes for unequal representation in politics. Overall, studying citizens’ perceptions of negative messages targeting politicians is critical to our understanding of what citizens perceive as constituting acceptable language in political debates, when online abuse can (and should) be countered, and the consequences of online abuse for unequal representation in politics.

In this study, we examine citizens’ perceptions of negative messages targeting politicians on social media. Specifically, we focus on how citizens perceive Facebook and Twitter comments containing criticism, insults, threats and sexist remarks. Here, we contend that citizens’ reactions to online abuse may be fundamentally shaped by the citizens’ general outlook on politics. Specifically, we focus on three key variables, describing how citizens relate to the domain of politics; partisanship, ideology and political trust. Drawing on an extensive literature from psychological research on social identity theory and recent research on ideology and political trust, we therefore theorize and test how these three variables moderate citizens’ perceptions of online abuse directed towards politicians.

Furthermore, it is clear by now that online abuse of politicians, and harassment of politicians in general, are strongly intertwined with gender. Male and female politicians are subjected to different types of abuse and harassment, and they may also react differently when attacked (Collignon & Rüdig, Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020; Maier & Renner, Reference Maier and Renner2018). Based on recent research on gender in politics, we therefore test the expectation that citizens’ perceptions of online abuse are conditioned on the gender of the targeted politician and the gender of the citizen.

To test our hypotheses, we use a preregistered survey experiment on a sample of 2,000 Danish citizens.Footnote 1 In this experiment, citizens were provided with examples of social media comments in the form of criticism, insults, threats and sexist remarks targeting politicians. Moreover, the politicians’ party affiliation and gender were manipulated. This experimental setup allows us to test how citizens perceive different types of negative messages targeting politicians, depending on the politicians’ party and gender (experimental) and the citizens’ ideology, trust and gender (observational).

Our results show that citizens differentiate between simple criticism and the three types of abusive messages, and that they are clearly most averse to threats. Further, while we do not find substantial effects of partisanship, our results show that citizens’ political ideology moderates the extent to which insulting, sexist and threatening comments are considered abusive, with right-leaning citizens being less averse to such messages than left-leaning citizens. We also find a strong moderating effect of political trust. Across all types of negative messages, citizens with low political trust are less likely to perceive messages targeting politicians as being abusive. Finally, we find that gender matters. Women are generally more averse to all negative comments than men, and aversion to sexist comments is higher when female politicians, rather than male politicians, are targeted. We end our article with a discussion on how our findings deliver novel insights into citizens’ perceptions of online abuse, and of the theoretical and practical implications of our study.

Theory: What is abuse?

Pinpointing what exactly constitutes an abusive message is challenging, as scholars tend to define abusive messages by the intention of the sender. For instance, Ward and McLoughlin (Reference Ward and McLoughlin2020) define abusive messages as messages ‘directed at a specific person with the intent to cause harm or distress’ (ibid, 55). However, focusing on the intention of the sender does not inform us about whether the messages actually cause harm or distress on the receiving end (i.e., the targeted politician) or how the messages are perceived more generally by bystanders. Consequently, the ‘sender intentions’ perspective ignores the important point that people likely disagree on the extent to which a message or comment is in fact abusive. What might be considered abusive by one group is not necessarily abusive in the eyes of another. We therefore turn our attention away from focusing on the intention of negative messages and instead study how citizens perceive different types of negative messages in general and according to factors such as gender and partisanship.

The term online abuse is closely related to other concepts such as online political hostility and hate speech. While there are different definitions of these related concepts in the literature, generally speaking, both terms are often defined based on the intentions of the sender. For instance, online political hostility focusses on abusive language that is aimed toward actively undermining democratic norms, while hate speech is abusive language targeting specific groups because of these groups’ innate group characteristics (Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2023). Our concept of online abuse is a somewhat broader concept, because it moves the focus from the intention of the sender to the experience of the receiver (or bystander in our case). This means messages that qualify as online political hostility or hate speech may not be perceived as online abuse, while other messages may be perceived as abusive, but not qualify as political hostility or hate speech. Naturally, in most cases, there will be considerable overlaps between the intention(s) of the sender and the perception(s) of the receiver. For instance, messages containing derogatory language or threats will often have hostile intentions and may be hard to perceive as anything but abusive.

Building on Ward and McLoughlin's (Reference Ward and McLoughlin2020) definition, we examine online abuse as the extent to which messages are perceived as being clearly transgressive. Specifically, we focus on four types of negative messages targeting politicians: criticism of their politics, personal insults, outright threats and sexist remarks. Although criticism is not typically characterized as abuse, we still include criticism in our study, as it provides us with a useful reference point against which to compare the other (potentially) abusive messages. Specifically, criticism concerns comments that target the politicians’ politics, but not their character. Some harsh criticism may of course be perceived as insulting. In this sense, the categories may overlap at the perceptual level, which is part of the empirical question that we address. Personal insults concern comments that target politicians using derogatory language, name-calling or slurs, while threats involves threats of physical violence or incitement of violence against the politician or the politician's family (Ward & McLoughlin, Reference Ward and McLoughlin2020). Finally, sexist remarks concern comments that objectify the politician sexually, contains unwelcome sexual propositions or in other ways convey a belief that the politician is subordinate or incapable due to his or her gender. Typically, research indicates that women are most frequently the subject of this kind of comment (Erikson et al., Reference Erikson, Håkansson and Josefsson2023).

While these four types of negative messages do not constitute an exhaustive list of all the different types of negative messages that politicians are exposed to on social media (our list does not include abusive messages containing, for example, racial or religious slurs), the four types of messages capture some of the most prevalent categories identified by previous scholars (Gorrell et al., Reference Gorrell, Greenwood, Roberts, Maynard and Bontcheva2018; Theocharis et al., Reference Theocharis, Barberá, Fazekas, Popa and Parnet2016; Ward & McLoughlin, Reference Ward and McLoughlin2020).

While we do not specify hypotheses about how citizens perceive the different types of negative messages, we know from research on online hostility that perceptions vary depending on the severity of the messages. For instance, Rasmussen (Reference Rasmussen2022) shows that citizens are more willing to impose restrictions on hate speech when confronted with negative messages containing degrading language or threats of violence. Recent studies on incivility also find that citizens notice and distinguish between degrees of uncivil behaviour in politics, and further show that sufficiently unpleasant and rude behaviour can alienate even people that identify with the misbehaving party, thus trumping the partisan bias that usually drives political views (Skytte, Reference Skytte2022). Our focus on criticism, insults, threats and sexism aims to capture some of the variation in severity of online abuse, and allows us to see if the impact of factors such as partisanship, ideology, trust in politicians and gender holds across messages, which presumably vary in severity.

Online abuse through a partisan lens

We start our theoretical discussion of the factors that moderate perceptions of abuse by focusing on partisanship. A key finding in the social identity theory literature is that human beings tend to display ingroup favouritism and outgroup scepticism in behaviours and attitudes (Spears, Reference Spears, Schwartz, Luyckx and Vignoles2011; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979). This is clearly also the case within the domain of politics, where partisanship – adherence to a specific political party – serves as an important part of the social identity of many citizens (Iyengar & Krupenkin, Reference Iyengar and Krupenkin2018; Kirkland & Coppock, Reference Kirkland and Coppock2018; Klar, Reference Klar2014; Odegard, Reference Odegard1960). We know that party identity powerfully colours individuals’ information processing, opinion formation and decision making in politics (Huddy & Bankert, Reference Huddy and Bankert2017). Most relevant to our purposes, several studies show that partisanship biases citizens’ views on democratically problematic behaviours. For example, incivility by political elites is seen by citizens as more acceptable if the misbehaving politician is from a citizen's in-party (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Gubitz, Levendusky and Lloyd2019; Skytte, Reference Skytte2021), while election fraud and dirty campaign tricks are more concerning to citizens if the fraudsters and dirty campaigners are from a political camp the citizen is opposed to (Claassen & Ensley, Reference Claassen and Ensley2016). Further, citizens view moral wrongdoings by co-partisans as less severe than if the perpetrator belongs to another party (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Briggs, Chahal, Fried, Garg, Kriz, Lei, Milne and Slayton2020). Even people's tolerance of very serious actions such as politically motivated violence and censorship has been found to vary according to whether it concerns people's own preferred party or not (Ashokkumar et al., Reference Ashokkumar, Talaifar, Fraser, Landabur, Buhrmester, Gómez, Paredes and Swann2020; Jakli, Reference Jakli2023).

Based on this tendency for partisanship to motivate citizens to express favour for in-partisans and disregard for out-partisans (Lelkes & Westwood, Reference Lelkes and Westwood2017), particularly in situations where politics are polarized (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012), we suggest that citizens’ perceptions of negative messages targeting politicians are likely to be biased by partisanship. We thus propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Citizens are more averse to negative messages directed at a politician from their preferred party than negative messages directed at a politician from another party.

Note that while we are interested in the impact of partisanship, we use the more encompassing term preferred party in Hypothesis 1, as the hypothesis is tested with several different measures of support for parties.

Online abuse through an ideological lens

Politics is not just about partisanship, however. Different ideological positions may also lead to different perceptions of online abuse. While the hypothesis above on partisanship suggests that citizens are generally biased by partisan considerations, citizens with different ideological positions on the political spectrum may differ in how they perceive online abuse. In other words, regardless of whether online abuse is directed at a co-partisan or not, people's reactions to such abuse may also depend on their own ideological leaning. Decades of electoral research shows that voters’ ideological left–right orientation is a fundamental predictor of policy opinions (Thomassen, Reference Thomassen2005). This does not, of course, mean that ideology necessarily matters for opinions on online abuse, as this issue is not a traditional dividing issue across the political spectrum (unlike, e.g., economic policies, which has traditionally separated the left and right on the political spectrum). Empirically, however, research has found a clear association between ideology and reactions to one particular type of harassment. Citizens with a conservative ideology are less likely than citizens with a liberal ideology to label behaviour as sexual harassment (Gothreau et al., Reference Gothreau, Warren and Schneider2022). Similarly, conservative citizens, at least in the United States (US), consider sexual harassment to be less of a problem than liberals do (Craig & Cossette, Reference Craig and Cossette2022; van der Linden & Panagopoulos, Reference van der Linden and Panagopoulos2019). While it can be difficult to disentangle ideology from partisanship in the US context, these finding may reflect deeper distinctions between political ideologies, rather than just partisan reactions. Even outside of the US context, conservatives generally exhibit higher levels of social dominance orientation compared to liberals, and individuals scoring high on this trait are more inclined to downplay sexual harassment (Kugler et al., Reference Kugler, Jost and Noorbaloochi2014). While these studies speak more broadly to sexual harassment, we contend that citizens’ aversion specifically to sexist messages may similarly depend on their political ideology. We therefore propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a: Aversion to sexist messages is stronger among citizens on the political left than among citizens on the political right.

More generally, since ideology is a dominant force in political opinions, citizens across the political spectrum may also differ in their assessment on other types of negative messages on social media than just sexism. There is not a strong theoretical basis for formulating hypotheses about this, however. On the one hand, right-leaning citizens tend to be more authoritarian (Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Costello, Duckitt and Sibley2023) and may thus be less tolerant of abuse of politicians, if abuse is perceived as culturally deviant or system-threatening behaviour. On the other hand, research shows that left-leaning citizens in Denmark and in the US are slightly more supportive of online hostility regulations than right-leaning citizens (Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2022). As this line of reasoning remains speculative, due to a lack of studies, we do not take a one-sided theoretical position here. Instead, we propose a non-directional hypothesis about such general left-right differences:

Hypothesis 2b: Aversion to negative messages differs between citizens on the political left and citizens on the political right.

Online abuse through a lens of political trust (or distrust)

Apart from partisanship and ideology, citizens’ political outlook may also affect perceptions of abuse in yet another way. Specifically, citizens’ trust in politicians may play an important role when citizens assess the abusiveness of negative comments directed at politicians. Here, trust in politicians refers to general trust towards politicians, not just trust towards specific politicians sharing one's own partisanship or ideology (or other characteristics such as social background). This more general trust in politicians correlates strongly with trust in political institutions (Hooghe & Marien, Reference Hooghe and Marien2013; Turper & Aarts, Reference Turper and Aarts2017). A low level of trust in politicians is not only associated with a lower likelihood of voting in elections (Grönlund & Setälä, Reference Grönlund and Setälä2007; Hooghe & Marien, Reference Hooghe and Marien2013), it is also associated with citizens’ attitudes on how politicians should be treated. For example, recent research has shown a link between citizens’ political distrust and their acceptance and intention to participate in collective violent action (Gulliver et al., Reference Gulliver, Chan, Tam, Lau, Hong and Louis2023). Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3: Aversion to negative messages is stronger among citizens with high trust in politicians compared to citizens with low trust in politicians

Online abuse through a gendered lens

Finally, we turn to a (ostensibly) non-political factor that may also play a role in citizens’ perceptions of online abuse, namely gender. Gender is not only associated with stereotypical expectations about the proper behaviour of men and women, it is also associated with normative expectations about how one should behave towards men and women. This includes benevolent sexism (Glick & Fiske, Reference Glick and Fiske2001) or the norm about protecting women, which denotes a stronger moral condemnation and willingness to intervene when a woman is a victim, as opposed to a man (Felson, Reference Felson2000; Felson & Feld, Reference Felson and Feld2009). On the other hand, we may also imagine that other attitudes such as hostile sexism (Leaper & Gutierrez, Reference Leaper and Gutierrez2024) exist among citizens. This would have the opposite effect and increase citizens’ acceptance of abusive language directed at women in politics. On balance, however, we expect that the norm about protecting women will dominate public opinion in the case of online abuse of politicians for at least two reasons. First, across various transgressions, particularly those involving some aggression, a classic finding in social psychological research is that ‘the normal victim’ tends to be stereotyped as being a woman (Howard, Reference Howard1984). Such broad social intuitions are likely to spill over and manifest themselves also in specific instances like abuse towards politicians. Second, as previously discussed, this intuition has been substantiated in several studies on women in politics, and abuse or violence against female politicians are now on the policy and media agendas in many countries (Erikson et al., Reference Erikson, Håkansson and Josefsson2023). Thus, as public perceptions are generally geared to expect female politicians being victims of abuse, we expect that citizens, on average, will also be more averse to online abuse against women. We therefore suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Citizens are more averse to negative comments directed at female politicians than negative comments directed at male politicians

While Hypothesis 4 suggests that citizens may react differently to attacks on male and female politicians, the citizen's own gender may also play a role. Gender has become increasingly important in structuring politics (Sass & Kuhnle, Reference Sass and Kuhnle2023), and it is a key predictor of several different policy attitudes (Eagly et al., Reference Eagly, Johannesen‐Schmidt, Diekman and Koenig2004). Of particular relevance to our study, recent evidence shows that women generally consider sexual harassment as a more serious problem than men do (Arya & Schwarz, Reference Arya and Schwarz2023). In addition, gender may also matter to perceptions of online abuse more broadly, not just sexist abuse. Research on conflict avoidance indicates that men – on average – are less conflict avoidant than women (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016), particularly when it comes to public conflicts (Mutz, Reference Mutz2015). These differences in conflict aversion between men and women may be a result of the socialization of women and men into distinct gender roles. Women are traditionally expected to be cooperative and consensus-seeking, while men are expected to be competitive and not shy away from conflicts (Wolak, Reference Wolak2022). These expectations mean that women and men react differently to conflicts already early in life, and this general difference in reactions to conflict may also affect how they respond to online abuse even as adults. Thus, as online abuse involves blatant political conflict in a public forum, we argue that women are generally more averse to abusive online behaviour than men, as summarized in the hypothesis below:

Hypothesis 5: Women are more averse than men to negative comments.

We note that there could also be an interplay between the respondent's gender and the gender of the targeted politician. For example, women might be extra averse to abuse targeting female politicians because there is a social affinity, or even identification, with the politician (Herry & Mulvey, Reference Herry and Mulvey2023). We did not preregister any hypotheses about such interactions, but offer some explorative analyses in the results section.

Methods and data

We test our hypotheses in a survey experiment, conducted within the context of Danish politics. Previous studies have found substantial levels of online abuse directed against Danish politicians. For example, in a recent survey, more than 72 per cent of the surveyed politicians stated that they had received insults through digital media, and 30 per cent had received threats (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Bjørn Grund Petersen and Thau2024).

Prior to our data collection, all hypotheses were preregistered along with a pre-analysis plan at the Open Science Framework.Footnote 2 The experiment was conducted in a commercial web panel (YouGov). Our survey was completed by 2,023 participants (with 2,050 individuals starting the survey, completion rate was 98.7 per cent; only 9 participants exposed to the experimental stimuli failed to complete the entire survey). Our final sample is a demographically diverse sample: 51.7 per cent of the sample is female, and age ranges from 18 to 93 years old (mean age is 51 years). The sample also shows substantial variation on political attitudes (see online Appendix A for additional details on sample characteristics). Furthermore, while our sample is not a probability sample, treatment effects in survey experiments are generally very consistent across probability and nonprobability samples (Coppock et al., Reference Coppock, Leeper and Mullinix2018).

Prior to the experiment, participants were asked background questions regarding demographics and various political attitudes, including trust in politicians and party preferences.

As noted, we measure party preferences with several different measures. As our first, most encompassing measure, we measure party preference simply as vote choice (specifically, q1 in Appendix B). Next, we use the traditional measure of partisan identity, asking whether people see themselves as a supporter of one particular party (q4_a). If they did not indicate that they supported a party initially, we asked if there was a party that they feel closer to than others (q4_b). Participants choosing a party in either of these two questions, were coded as identifying with the party. Finally, as an additional measure of party preferences, we measure party sympathy for each individual party on a 0–10 scale (see q6 in Appendix B). To measure the respondents’ ideological position, we also used a 0–10 scale of people's left-right position. Finally, trust in politicians was measured by an index composed of three items, respectively, general trust in politicians on a 0–10 scale (‘On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means no trust and 10 means complete trust, how much trust do you generally have in Danish politicians?’) and the level of agreement with two statements regarding the politicians (‘Most politicians are competent people who know what they are doing’ and ‘Most politicians are in politics only for what they can get out of it personally’ [reversed]). These three items have previously been found to form a reliable index for trust in politicians (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Hansen and Pedersen2022), and this was also the case in our data (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.80).

Our experiment uses the same design, including the experimental stimuli and measurement of the dependent variable, as developed in Pedersen et al. (Reference Pedersen, Bjørn Grund Petersen and Thau2024), which was used to assess politicians’ perceptions of online abuse. Similar to that study, the participants in our study were asked to assess different fictitious social media comments to politicians. Concretely, each participant was asked to assess four social media comments, respectively a comment containing criticism, insults, threats and sexist remarks. Importantly, we randomized the order in which the different types of comments were presented. For example, participants could be shown the following sexist comment directed at a (fictitious) politician: ‘Seriously, only a woman can say something so stupid’. The comments were randomly drawn from a total of 20 different comments, five within each type of comment. All 20 comments are included in the Supporting Information Appendix. By sampling experimental stimuli from a larger corpus of comments, the design aims to minimize the risk that idiosyncratic characteristics of one specific comment drive the results (Wells & Windschitl, Reference Wells and Windschitl1999).

In the experiment, we also randomized the fictitious politician's gender and party. We manipulated gender by changing the name and associated pronoun of the politician. We randomly drew a name from a pool of the 20 most common male names and 20 most common female names in Denmark (shown in the Appendix).Footnote 3 The party of politicians was drawn from the 12 political parties represented in the Danish parliament at the time of the experiment. As Hypothesis 1 concerns the effects of politicians being in-party versus out-party, randomization of the party was stratified so that the participant had a 50 per cent chance of being exposed to a fictitious politician from their own preferred party. Here, we used vote choice as measure of party preference (we did this because, in a Danish context, participants are more likely to provide a specific party when asked about vote choice as opposed to party identity). To increase generalizability of our results, we also randomized whether the comment occurred on Facebook or Twitter. We did not expect any differences between the two social media sites, and an exploratory analysis confirmed that there were no significant differences in the participants’ perceptions toward negative comments depending on the social media site.

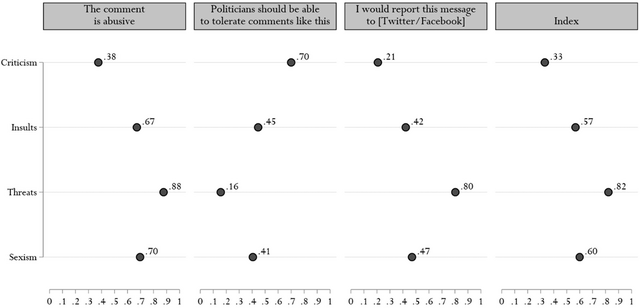

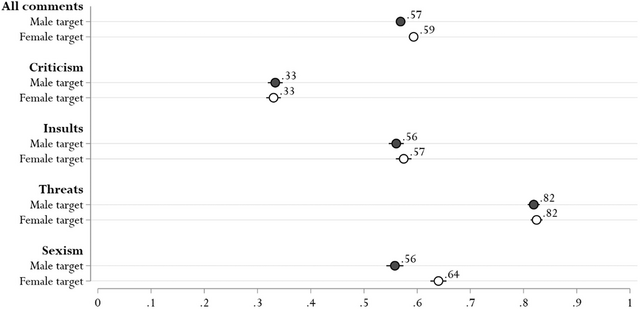

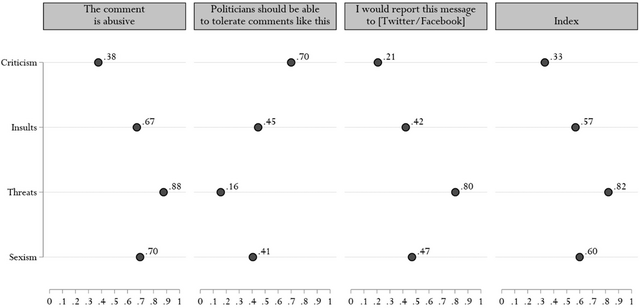

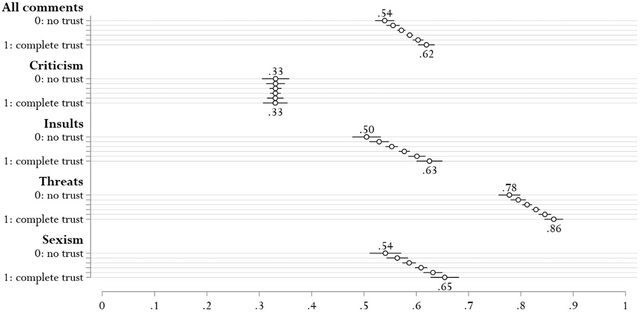

As previously noted, the dependent variable in our experiment is aversion to negative comments. We measured aversion to the specific comments, by asking participants about their level of agreement with the three following statements regarding the comments: (1) ‘The comment is abusive’, (2) ‘Politicians should be able to tolerate comments like this’ [reversed] and (3) ‘I would report this message to [Twitter/Facebook]’.Footnote 4 Following our pre-analysis plan, an index for aversion was constructed from replies to these three items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.83). The aversion index was scaled to range from 0 to 1. Below, Figure 1 displays estimates for each of the three individual items in the aversion index, as well as the aversion index estimates across all four types of negative comments. Interestingly, Figure 1 reveals that citizens have the most pronounced aversion for abusive comments targeting politicians when the comments contain threats. Citizens have a slightly higher aversion toward sexist remarks compared to insults. Unsurprisingly, citizens clearly have the least aversion towards criticism. In the Appendix, we display estimates for each individual comment on the aversion index (Figure A1), as well as the distribution of the three aversion items across all types of negative comments (Figure A2).

Figure 1. Mean aversion by outcome measures and the type of negative comments

Results

In line with our preregistered analysis plan, we test our hypotheses using regression models. We test the hypotheses separately for all four types of negative messages (i.e., criticism, insults, threats and sexist remarks as well as for all types of comments combined). In all tests, our index of aversion is the dependent variable, and standard errors are clustered at the level of the respondent. Our primary and preregistered models for testing the hypotheses are simple models that only include the variables specifically needed to test each hypothesis. In addition to these primary models, we also conduct supplementary analysis where we add the following covariates to the simple models (provided that the covariate is not already included in the primary model): gender of respondent, age of respondent, the left–right position of the respondent and the respondent's level of trust in politicians. All models are shown in Appendix C.

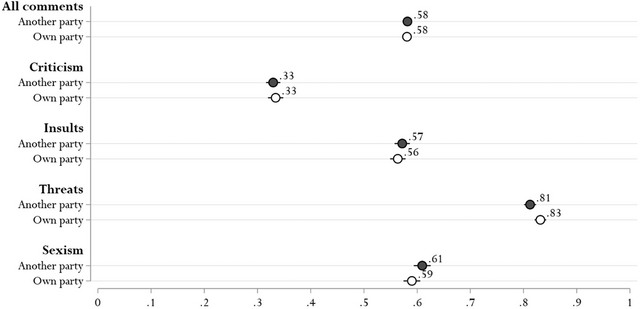

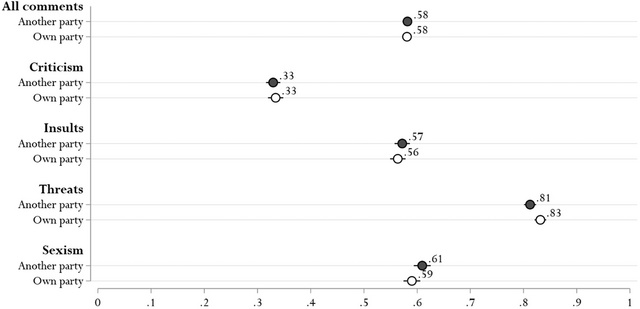

As the first step in our analysis, we investigate the degree to which citizens’ perceptions of online abuse depend on their party preferences, as predicted by Hypothesis 1. Overall, we do not find support for the hypothesized effect, as citizens’ perception of what constitutes online abuse does not generally depend on whether the targeted politician is an in- or out-party member.

Following the preregistration, our first analyses distinguishes between in- and out-party, based on vote choice. Measured across all comment types, mean aversion to the negative messages is 0.58 on the scale both when the targeted politician is in-party and when the targeted politician is out-party. More precisely, mean aversion is 0.0009 points lower when directed at an in-party politician compared to an out-party politician, and this tiny difference is clearly insignificant (p = 0.858). As illustrated in Figure 2, partisan differences are also generally not found when looking at the four different types of negative comments. The differences in reactions are insignificant for criticism (p = 0.642), insults (p = 0.419) and sexism (p = 0.087). Only in the case of threats do we observe a significant difference. Aversion to threats against an out-party politician is 0.81, while aversion to threats against an in-party politician is 0.83, and this difference is statistically significant (p = 0.016). However, while statistically significant, the difference between out-party and in-party is substantially small, and in both cases, aversion to threats is very high. An exploratory analysis shows that when exposed to a comment containing a threat directed at an out-party politician, 85.0 per cent of respondents agreed ‘strongly’ or ‘very strongly’ that such a threat was abusive. When the politician was from an in-party, the corresponding share was 87.2 per cent. Thus, the vast majority of citizens considers threats to be abusive, regardless of partisanship.

Figure 2. Partisanship and aversion to negative comments (Estimates with 95% CI)

These results are generally very robust to other models and measures of party preferences. In the supplementary models with additional covariates, citizens’ level of aversion to sexist messages is significantly lower when directed at in-partisans rather than out-partisans, that is, in the opposite direction of the hypothesized effect (p = 0.021). However, the substantial difference is small (aversion is 0.61 for out-partisans and 0.59 for in-partisans). This is also the case when we base our analyses on party identity. As shown in the Appendix (Table A4 and Figures A3-A4), partisan identity is a weak and generally insignificant moderator, only showing statistically significant, albeit still small, differences in reactions to threats and sexism. Finally, analyses based on party sympathy yield similar results. As shown in Figure A5, there are generally no effects of party sympathy, except in cases where the comments contain threats. Consequently, both our preregistered and exploratory analysis offers support for the conclusion that there is a general absence of a partisan bias, but also underscores the possibility that the partisan effect may be activated when the negative comments involve threats.

Despite evidence of a small partisan effect when the comments concern threats, the lack of a general partisan effect is quite noteworthy, given the theoretical expectations, and the previous studies showing partisan biases in comparable situations (Lelkes & Westwood, Reference Lelkes and Westwood2017). It is important to keep in mind that our survey was conducted in a Danish context, where the level of affective polarization is relatively modest compared to other countries (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2022; Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). We return to and discuss this finding in the concluding discussion.

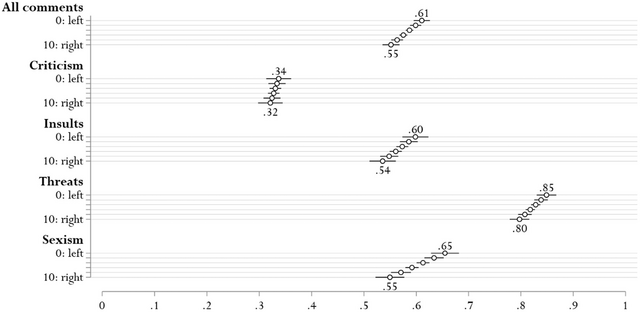

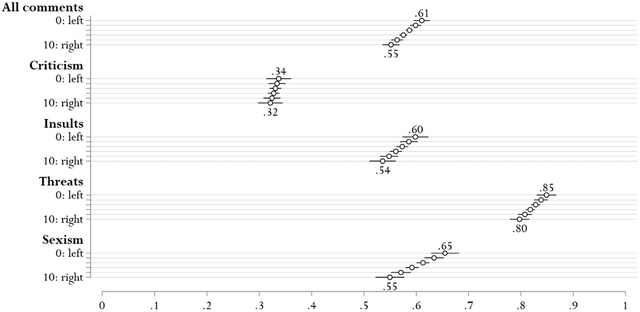

Concerning Hypothesis 2, which predicts that aversion to sexist messages is stronger among citizens on the political left than among citizens on the political right, the bottom of Figure 3 reveals that this is indeed the case. Citizens on the left are clearly more averse to sexist messages than citizens on the right (p < 0.001). For example, a citizen at the far left of the political spectrum has a predicted aversion of 0.65, while a citizen on the far right of the political spectrum has a predicted aversion of 0.55. The more general hypothesis H2b, predicting that aversion to negative messages differs between citizens on the political left and citizens on the political right, is also clearly confirmed. As illustrated in Figure 3, left-leaning citizens are also significantly more averse to insults (p = 0.007) and threats (p = 0.003). Only when reacting to criticism are the differences between left and right insignificant (p = 0.465)

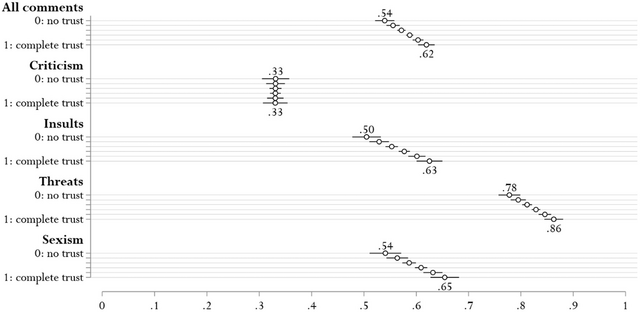

Figure 4. Political trust and aversion to negative comments (Estimates with 95% CI)

Figure 3. Political left-right position and aversion to negative comments (Estimates with 95% CI)

When interpreting these results, it is important to note that the left-right positions of citizens are obviously not an exogenous variable in the experiment. Therefore, the results reflect effect modification (Keele & Stevenson, Reference Keele and Stevenson2021), not necessarily a causal effect of left-right position. However, in our supplementary models, we add covariates for gender, age and political trust, and the associations between ideology and aversion to negative messages remain significant and substantial (cf. Model 7 in the Appendix).

Next, according to Hypothesis 3, we expect that aversion to negative messages is stronger among citizens with a high level of trust in politicians compared to citizens with a low level of trust in politicians. Figure 4 shows strong support for this hypothesis (p < 0.001). Curiously, when looking specifically at the four types of negative comments, criticism stands out as being completely unaffected by citizens’ level of trust (p = 0.978). In contrast, citizens’ level of trust is markedly and significantly associated with citizens’ aversion to insults, sexist remarks and threats (all p<0.001). Our supplementary models yield substantively similar results (c.f. Table A3 in the Appendix C).

In addition, in an exploratory analysis, we disaggregate our index of trust, and look individually at the three items used to construct the index. This exploratory analysis shows, that the patterns are consistent across all three items (c.f. Table A4 and Figure A4 in the Appendix).

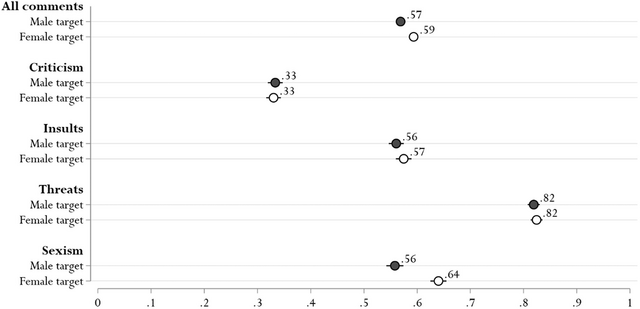

Hypothesis 4 predicted that citizens are more averse to negative comments directed at female politicians than negative comments directed at male politicians. This hypothesis is also confirmed. When looking across all types of comments, aversion is indeed significantly higher when a female politician is targeted compared to a male politician (p < 0.001). The difference, however, is not large, as the mean aversion to negative messages directed at male politicians is 0.57, while the mean aversion to negative messages directed at female politicians is 0.59. Moreover, the effect of the politician's gender is clearly heterogeneous across the four different types of negative comments. As illustrated in Figure 5, the general difference in citizens’ aversion to negative comments directed at male and female politicians is entirely driven by comments containing sexist remarks. Aversion to sexist comments is 0.08 points higher when the target is a female politician rather than a male politician (p < 0.001). In contrast, citizens’ aversion to the comments is not significantly affected by the gender of the politician when the comments concern criticism (p = 0.747), insults (p = 0.176) and threats (p = 0.504). Our supplementary models yield substantively similar results (c.f. Table A3 in the Appendix C). Thus, rather than being broadly applicable to abuse in general, it appears that the norm about protecting women applies specifically to sexist attacks, where female politicians are known to actually suffer the most exposure.

Figure 5. Gender of target and aversion to negative messages (Estimates with 95% CI)

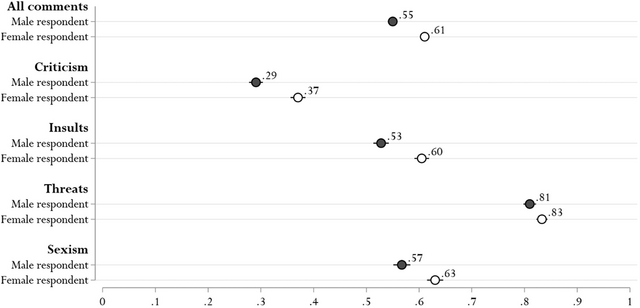

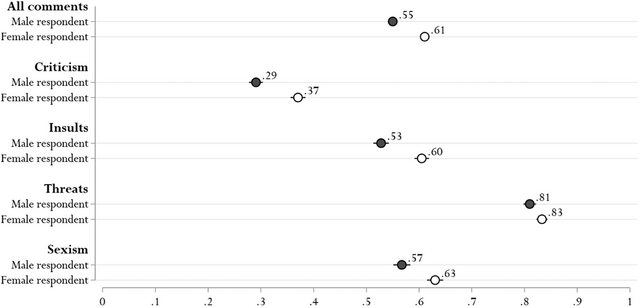

Finally, Hypothesis 5 predicts that women are more averse than men to negative comments. As illustrated in Figure 6 below, we find strong support for this hypothesis. In general, women exhibit a higher aversion to negative comments (p < 0.001). When examining the differences across our four types of comments, we also observe that women have a higher aversion to criticism (p < 0.001), insults (p < 0.001), threats (p = 0.004) and sexist remarks (p < 0.001). Our supplementary models yield substantively similar results (c.f. Table A3 in the Appendix C).

Figure 6. Gender of respondent and aversion to negative messages (Estimates with 95% CI)

Seeing these results on gender, one might also ask whether the gender of the respondent may interact with the gender of the targeted politician. An exploratory analysis indicates that this might be the case for sexist abuse, where the gender of the targeted politician affects responses from women more than men (p = 0.039). For other types of negative comments, these interactions are not statistically significant (c.f. Table A6 and Figure A7 in the Appendix). Thus, these results suggest that the gender of the respondent and the gender of the targeted politician may interact in some cases, although it is important to note that these results are exploratory.

Discussion and conclusion

Research has shown that online abuse directed towards politicians has serious democratic consequences (Collignon & Rüdig, Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020; James et al., Reference James, Sukhwal, Farnham, Evans, Barrie, Taylor and Wilson2016; Maier & Renner, Reference Maier and Renner2018). To effectively address this issue, it is important to understand the conditions under which citizens perceive negative messages targeting politicians as abusive. This study contributes to our understanding of citizens’ perceptions of online abuse by investigating how aversion to different types of negative comments on social media are influenced by partisanship, political ideology, trust and gender.

Contrary to our expectations, we do not find any evidence of a partisan bias when citizens assess negative messages targeting politicians from their own or oppositional parties (Hypothesis 1). However, we did observe strong and robust correlations between citizens’ political ideology and their perceptions of sexist remarks as being abusive (Hypothesis 2). Left-leaning citizens exhibited a greater aversion to sexist remarks compared to their right-leaning counterparts. Furthermore, political ideology also proved to be a significant predictor of citizens’ perceptions of insults and threats directed at politicians (Hypothesis 2b), with left-leaning citizens showing a stronger aversion to these types of negative messages compared to right-leaning citizens. Additionally, our study provides evidence supporting the notion that citizens’ level of trust in politicians affects their perceptions of negative messages (Hypothesis 3). Although this finding – similarly to our finding concerning political ideology – is correlational, it is nonetheless intriguing, as it suggests that low levels of trust in politicians may increase citizens’ tolerance towards online abuse directed at political elites.

Our results also show that the gender of the targeted politician matters to how citizens form perceptions of online abuse (Hypothesis 4). However, this effect was only significant in the context of sexist remarks. Thus, citizens only displayed a higher aversion towards sexist remarks targeting female politicians compared to those aimed at male politicians. We found no noteworthy effects when examining negative messages concerning criticism, insults or threats. Finally, our findings show that the gender of the observing citizen also matters (Hypothesis 5). Specifically, women exhibited a greater aversion to negative messages across all four categories than their male counterparts. If we compare our results to previous research on politicians’ perceptions of online abuse, we can see that politicians generally display the same biases as we have identified among citizens in our results. Thus, similar to our study, Pedersen et al. (Reference Pedersen, Bjørn Grund Petersen and Thau2024) did not identify a partisanship bias among politicians, which supports the idea that citizens’ perceptions of online abuse transcends partisanship – at least in the Danish context (we discuss the influence of the contextual setting below).

Before turning to the implications of our findings, it is important to address some limitations of our study. First, although our study contributes with new insights into how abusive messages targeting politicians are perceived by citizens, we also need to acknowledge that our focus on perceptions of messages on the receiving end (rather than the intention of the sender) comes with some limitations. Specifically, by disregarding the intention of the sender, we may overlook some abusive motives, even if the receiving end does not perceive it as such. For instance, what may appear as fair criticism on the receiving end may in fact be a result of sexist motives, if the comments were only raised due to the politician's gender. On the other hand, fair criticism may also in some cases be perceived as sexism. Some citizens may have experienced sexism in politics and these experiences may affect how they interpret certain comments. This may in particular be the case if the comments are targeting female politicians, as women are much more likely to have experienced online sexism (Erikson et al., Reference Erikson, Håkansson and Josefsson2023).

Second, it should be noted that our study was conducted within the Danish context, where the level of affective polarization in the population is relatively modest compared to other countries (e.g., the US and the UK, see Boxell et al., Reference Boxell, Gentzkow and Shapiro2022; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). Denmark has a multiparty system, and the political culture is characterized by cross-party cooperation and compromises (Stubager et al., Reference Stubager, Hansen, Lewis‐Beck and Nadeau2021). These contextual factors should be taken into consideration when assessing the external generalizability of our findings. It is plausible that some of the results would have turned out differently in more politically polarized countries. For example, party identification constitutes one of the most important social identities in the US (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015; Iyengar & Westwood, Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018), which may well affect the likelihood of identifying partisan bias in effects on citizens’ aversion toward online abuse (Hypothesis 1). Therefore, we encourage researchers to examine the role of partisanship on citizens’ perceptions of online abuse in politically polarized countries to investigate whether our null effect of partisanship replicates under such circumstances.

The third limitation of our study concerns our experimental design. First, our list of negative messages does not contain an exhaustive list of all the types of negative messages encountered by politicians on social media. We should therefore be careful when attempting to extrapolate our results to other forms of negative messages. This may be particularly important regarding our finding that shows left-leaning citizens exhibiting a greater aversion to negative messages than right-leaning citizens do. We may well imagine that if the negative messages had included religious slurs, a different pattern may have emerged, with right-leaning citizens displaying a stronger aversion than left-leaning citizens toward the messages, as right-leaning citizens tend to be more religious (Hirsh et al., Reference Hirsh, Walberg and Peterson2013). In addition, while we primarily exposed the respondents in our study to abusive comments that – to a large extent – clearly fell into one of our four categories, abusive comments will often overlap the different categories. This is particularly the case, if we take the intention of the sender into account. For instance, an abusive comment that is meant to be an insult, might be perceived as a threat or as a sexist comment. Thus, we should not be blind to how abusive comments may simultaneously contain elements of insults, sexism and threats. Another limitation to our design is that we opted for using fictitious politicians rather than real politicians. We did this for methodological and ethical reasons. First, we were interested in a strong causal design that allowed us to isolate and test all our hypotheses. However, using real politicians would mean that more than just the politician's party and gender were manipulated (because citizens’ have priors about specific politicians). Second, we deemed it potentially problematic from an ethical standpoint to direct abusive comments towards real politicians (even if these politicians would not be exposed to these comments). Finally, it is important to emphasize that our findings concerning political ideology and trust in politicians are correlational in nature. Although our results remain robust even after accounting for a number of relevant confounding variables, we should be cautious of assuming a causal relation between the variables.

Our findings hold a number of important implications for both theory and practice. First, our study demonstrates that perceptions of what constitutes online abuse of politicians cannot solely be derived from the content and severity of the message itself. Instead, perceptions of abuse are substantially influenced by different factors, including citizens’ political ideology, trust in politicians, as well as the gender of both the citizen and the targeted politician. This suggests that we should be careful of only focusing on the intention of a message when discussing what constitutes abuse, as the perception of the message will differ significantly across individuals. Yet, it is noteworthy that despite the heterogeneity associated with political ideology, trust in politicians, and gender, we consistently observe some general patterns. For example, citizens have a strong aversion towards threatening comments. This finding suggests that there is a certain severity threshold that transcends political differences, where citizens collectively perceive threats as crossing the line. Similarly, the lack of a general partisan bias in the assessments of negative comments is encouraging from a democratic perspective, suggesting that citizens are able to look beyond the narrow interests of their own partisan ingroup, when adjudicating between valid criticism and abuse.

Second, our results concerning citizens’ political ideology and their aversion toward negative messages provide a potential explanation for why liberals are more supportive of restricting free speech on social platforms than conservatives (Skaaning & Krishnarajan, Reference Skaaning and Krishnarajan2021). This ongoing debate might not only reflect divergent ideological stances but also differing thresholds or tastes about what constitutes abusive language. In this way, our results help us understand different political viewpoints within the political debate that is currently unfolding in many Western countries. However, in addition to political ideology and trust in politicians, we may well imagine other important variables that affect citizens’ perceptions of online abuse of politicians. We encourage future research to examine how factors, such as citizens’ attitudes on gender and feminism, shape their perception of abusive messages.

Third, our results contribute to our understanding of the underlying causes of unequal representation in politics. Thus, we demonstrate that women, on average, are more averse than men to negative messages directed at politicians (even criticism). Given the prevalence and persistence of online abuse in politics, online abuse may potentially dissuade aspiring or emerging political candidates from entering politics. If women, as our findings suggest, tend to be more averse towards negative messages than men, they may be more inclined to abstain from entering politics. This could further exacerbate existing representational inequalities in a democracy such as Denmark.

Fourth, our findings may also be relevant to discussions on how initiatives against online abuse could be designed. Thus, interventions based on, for example, informational campaigns, could seek to mobilize citizens or users on social media by highlighting how politicians are exposed to threatening comments, since both left- and right-leaning citizens both exert high levels of aversion towards this type of comment. Similarly, as citizens are generally more averse to abuse directed at women, it may be useful to highlight that abuse is not just directed at the stereotypical male politicians. Further, as we found an association between higher levels of trust in politicians and citizens’ aversion towards abuse, it is not unlikely that increased trust in politicians may also at the same time increase citizens’ aversion towards abuse of politicians. Thus, any initiative aimed at increasing trust in politicians is also potentially an initiative which may decrease acceptance of abuse directed at politicians. However, trust in politicians are, of course, not necessarily easily improved.

Finally, it is worth contemplating whether our findings apply in situations where a fellow citizen rather than a politician is the targets of online abuse. On the one hand, we should probably not expect trust in politicians to be strongly associated with aversion towards abuse of ordinary citizens. On the other hand, however, it seems plausible that several of our results would be somewhat similar, for example our findings on the importance of gender. Future studies may want to further investigate the interactions of gender in assessments of online abuse, looking both at the gender of the observer and the gender of targeted person. As such, our results are not necessarily just about abuse of politicians, they may – at least to some degree – reflect more general patterns in how we react when fellow men and women are attacked.

Acknowledgements

This study was previously presented at the 2023 annual conference of the European Political Science Association and in a seminar at VIVE – The Danish Center for Social Science Research. The authors are grateful for the helpful and constructive comments from participants on these occasions. We also extend our sincere thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for their positive and detailed feedback, which greatly contributed to the improvement of this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and replication materials are available on the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LIXDR1.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: