Since “big data” entered our lexicon, it can sometimes feel like we live in a world governed by an inescapable “data imperative” driving us all to collect and exploit ever more information (Fourcade and Healy Reference Fourcade and Healy2024, 76–77). Law is part of this trend, and an emergent vein of American socio-legal scholarship investigates “the datafication of law” or the process by which real-time, high-volume granular legal information is collected, analyzed, and used.Footnote 1 Much of this scholarship shares a critical bent. It warns of the perils of intensified surveillance, algorithms that entrench racial discrimination, and loss of privacy (Pasquale Reference Pasquale2015; Eubanks Reference Eubanks2018; Lageson Reference Lageson2020; Brayne Reference Brayne2020; Lamdan Reference Lamdan2022).

This article complements these important normative debates by offering an empirical case study that deepens our understanding of the datafication of law in two ways. First, American scholars often overlook that the rise of big data, machine learning, and natural language processing in the 2010s is a global story, not a national one. Legal professions around the world are grappling with technological change and how deeply to embrace the rise of big legal data. This article offers a case study of a contentious public conversation over the perils and promise of big data in France, another democracy with a storied legal system. In 2016, France’s Law for a Digital Republic promised public access to all French judicial decisions, a seismic shift for a civil law country that had historically only published a limited set of cases.Footnote 2 The law sparked a heated debate, as coalitions inside the legal profession maneuvered to influence emerging policies over the process for anonymizing court decisions and the allowable conditions of data reuse. Second, France’s fight over what they called “open data” reminds us that the datafication of law is not an inexorable force. Instead, it is a process that legal professionals can guide, direct, and even stop. In 2019, France became the first country in the world to ban data analytics that reveal the identity of individual judges.

Looking comparatively is important because the public policy issues involved crisscross jurisdictions. The sentiment that “justice must be seen to be done” echoes across contexts,Footnote 3 and apex court decisions are widely available. The debate is over lower court decisions, specifically how many to release to the public, how much to redact, and whether large-scale data analysis of a now-huge corpus of court decisions should be allowable and by whom. On one level, these are technical issues typically debated among legal insiders. But on another level, what is at stake is a bedrock principle of broad public interest: what judicial transparency will mean in the twenty-first century and what kinds of legal information will be publicly available. After all, placing court decisions in a searchable online database dramatically increases their accessibility, potentially eliminating what is sometimes called practical obscurity. Court systems also face choices about whether to develop dashboards so that court administrators can distill trends from vast amounts of now-available judicial data or let private companies “access and capitalize on data minted by the state” (Fourcade and Gordon Reference Fourcade and Gordon2020, 81).Footnote 4 France was an early mover in this space, and the French debate offers insight into opportunities, tensions, and challenges likely to arise elsewhere as well.

More conceptually, France’s contentious struggle over judicial data reveals the critical, political role the legal profession plays as guardians and re-interpreters of cultural scripts related to law. The exogenous shock of the 2016 law exposed schisms within the legal profession between “entrepreneurs of innovation”Footnote 5 and traditionalists. It took years for the debate to calm, with France’s two high courts (the Conseil d’État and the Cour de cassation) eventually striking a balance between privacy and transparency strongly influenced by the rise of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) as a force in European politics. But this unsettled moment of norm contestation, which unfolded between 2016 and 2023, also had lasting ramifications for France’s understanding of itself. Debates largely internal to the legal profession became an arena to mete out France’s approach to some of the key developments of the twenty-first century: open data, privacy, technological innovation, and artificial intelligence. Many shared the goal of charting a distinctive French path forward, both to burnish France’s image in the world and to serve as a counterpoint to other centers of geopolitical gravity, especially America and China.

The Datafication of Law and the Role of the Legal Profession

This article bridges two scholarly conversations that have not yet had much to say to each other. Across law, sociology, and political science, an interdisciplinary literature has emerged over the past decade about the rise of big data and the implications for law and governance. Much of this work, especially its socio-legal strand, has been rightfully concerned about the relationship between information, technology, and power. The driving questions are who benefits and loses from the adoption of new technologies powered by big data, and the implications for inequality. In response, several finely drawn recent ethnographies detail how the combination of big data and technology is reshaping workplaces and the enforcement of law.Footnote 6

Much of the focus of existing scholarship has also been on the use and misuse of criminal justice data, particularly the use of algorithms to guide police surveillance and set bail (Brayne Reference Brayne2020; Lageson Reference Lageson2020), leaving a gap in our understanding of other types of judicial data.Footnote 7 In particular, information generated through civil and administrative litigation has received far less attention, even though such lawsuits reliably produce reams of documents. One reason for this omission in America is that not much judicial data is freely available to the public. PACER, the government-run federal courts database, is behind a paywall, as are the private databases most widely used by lawyers, Westlaw and Lexis Nexis.Footnote 8 As a result, American writing about non-criminal judicial data tends to focus on future ways that public access to large-scale data about litigation could reduce inequality (Johnson and Rostain Reference Johnson and Rostain2020; Clopton and Huq Reference Clopton and Huq2024). Yet elsewhere in the world, places like China, France, the UK, Canada, Vietnam and Belgium have begun experimenting with policies to expand access to lower court decisions--sometimes dramatically so–and to create free, national databases of court documents.Footnote 9

Research on the datafication of law has also yet to place the legal profession—defined as lawyers, judges, and legal scholars, and others who do legal work—at the center of political decisions about legal information.Footnote 10 “Data has politics,” as data and society scholars Jenna Burrell and Ranjit Singh write, and the legal profession is deeply involved in “contests … over whose interests the state aligns with” when it comes to legal information (Reference Burrell, Singh, Jenna Burrell, Singh and Davison2024, 30). By examining how the legal profession participates in data politics, this article adds to a long-running scholarly conversation about lawyers as political actors around the world. In the English language scholarship about France, lawyers are best known for a centuries-long commitment to political liberalism that influenced the development of the French state (Karpik Reference Karpik1999) and, more recently, for the emergence of an elite, Paris-based corps that rotates between high-level government jobs and corporate law firms (France and Vauchez Reference France and Vauchez2010).Footnote 11 The politics surrounding open judicial data, however, reveal a more diffuse pathway of political participation. Open data was an exogenous shock, which ruptured old ways of doing things and, by necessity, mobilized a wide swath of the legal profession to rearticulate core values and re-imagine new practices.Footnote 12

Conceptually, I frame the French legal profession as playing a political role as guardians of law-related cultural scripts, defined as “the background norms, templates, guidelines or models for ways of thinking, acting, feeling and speaking in a particular cultural context” (Goddard and Wierzbicka Reference Goddard and Wierzbicka2004, 157). In the case study presented here, the French legal profession bore collective responsibility for renegotiating a cultural script surrounding judicial transparency: an issue with implications for national priorities, national identity, and even geopolitical power. This fits the legal profession into a revitalized scholarly discourse about how geopolitical rivalries shape national legal institutions and vice versa. Work in this vein includes Mark Jia’s examination of how a growing rivalry between America and China is shaping American law (2024) and Anu Bradford’s framing of the US, the EU, and China as “digital empires” who jockey for world influence by promoting distinct models of how to regulate the digital economy (Bradford Reference Bradford2023). Yet for all the insights of this important, big picture, policy-adjacent scholarship, it can sometimes feel oddly devoid of the choices made by flesh-and-blood humans. The article suggests a way forward, which is to join socio-legal researchers who treat members of the legal profession as gatekeepers who stand at the intersection of global and national fields and collectively debate how to react to emergent technologies and transnational ideas (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth2021).

The diversity of the French legal profession is also front and center in this case study. In keeping with the insight from neo-institutional theory that advocates for change are often on the periphery where they are “less constrained by the industry’s way of doing and thinking” (Kellogg Reference Kellogg2011, 9), French legal technology firms jump out as an important new “aspiring quasi-elite” oriented toward disrupting the status quo (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth2021, 194). Beyond France, one implication of this article is that there will be—and should be—much more socio-legal scholarship on legal tech in the years to come. By virtue of both identity and incentives, legal tech companies are distinct from the traditional bar. As others are beginning to chronicle (Kronblad & Jensen, Reference Kronblad and Henning Jensen2023), legal tech companies are far more influenced by Silicon Valley than Big Law, and this distinctive professional identity makes them critical cross-national catalysts of change. The patterns of coalition politics present in France are likely to emerge elsewhere, with divisions over the value of technology and big data as a fault line running through the legal profession.

Data and Methods

France’s years-long debate over the public release of lower court decisions left an extensive public record. This article draws on this paper trail, which includes transcripts of legislative debates, government reports, news articles, and social media posts. The debate over open data also attracted attention from French scholars, and this article builds on first-rate qualitative research (in French) by Anne Bellon, Laurence Dumoulin, Camille Girard-Chanudet, Thomas Léonard, and Michel Moritz.Footnote 13

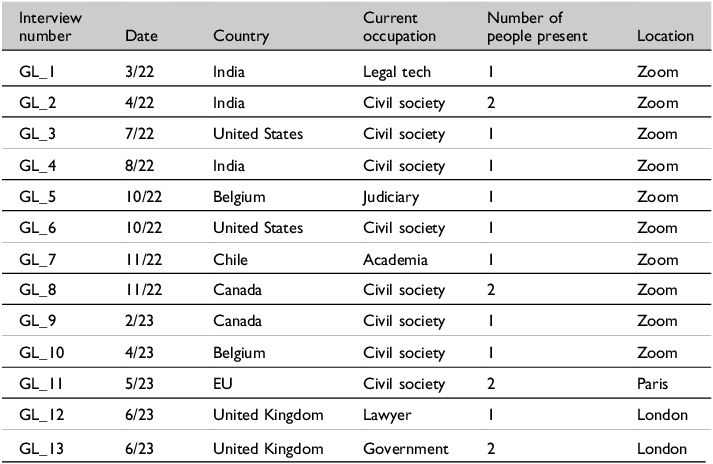

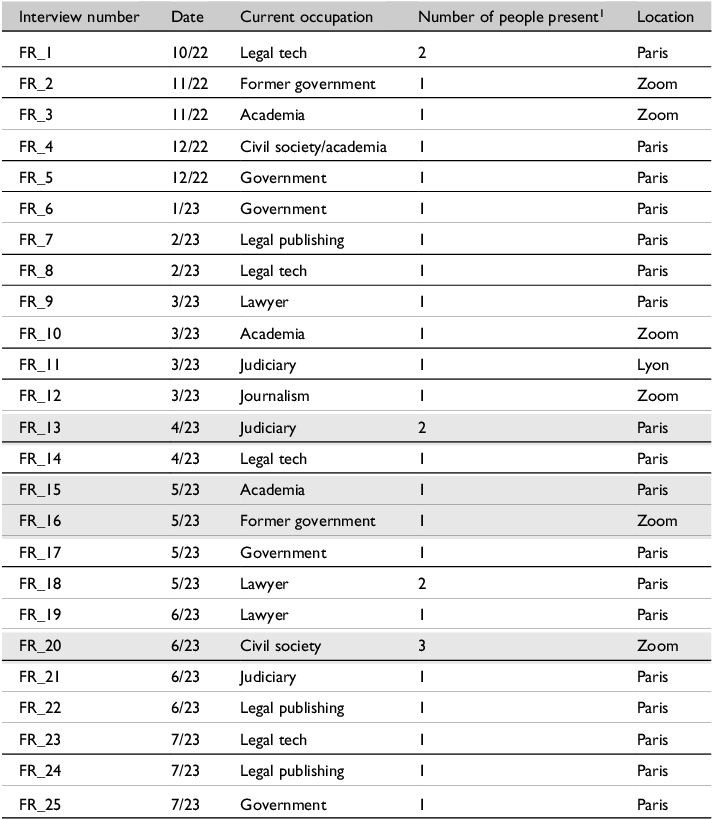

I also arrived in Paris in August 2022 and conducted fieldwork over the subsequent twelve months. This included twenty-five semi-structured elite interviews with judges, lawyers, legal academics, legal publishers, and data scientists involved in the conversations about open data (listed in Appendix A).Footnote 14 These conversations lasted between forty-five minutes and three hours and were mostly conducted in-person, either in English or with the help of a translator.Footnote 15 During these conversations, I typically asked interviewees about the risks and rewards of publicly releasing lower court decisions, their perceptions of how other actors felt about the issue, and how the French conversation had evolved since 2016. I either recorded interviews or took notes by hand, at the preference of the interviewee, and later coded either the transcript or my notes using Dedoose.Footnote 16 In addition, I learned a great deal from off-the-record discussions with knowledgeable observersFootnote 17 and benefited from a set of thirteen interviews about access to court decisions in India, Belgium, Canada, Chile, and the UK (listed in Appendix B).Footnote 18

In terms of timing, the public debate over opening lower court decisions was subdued in August 2022 compared to a few years earlier. The high tide of controversy was plainly past—the phrase “predictive justice” peaked in the media and on Twitter in 2017 (Dumoulin Reference Dumoulin2022, 100–102)—and most players were simply waiting to see if the courts would release the first tranche of civil lower court decisions in 2023 on the promised timetable. Although this quieter implementation phase afforded fewer opportunities to observe fiery public debates, I attended events at places like the Maison du Barreau (home of the Paris bar), the Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés (the French data protection authority) and le grand RDV des transformations du droit (an annual legal tech exhibition) that offered insight onto the political and technical difficulties of placing lower court decisions online and how norms surrounding transparency and privacy were being discussed.Footnote 19

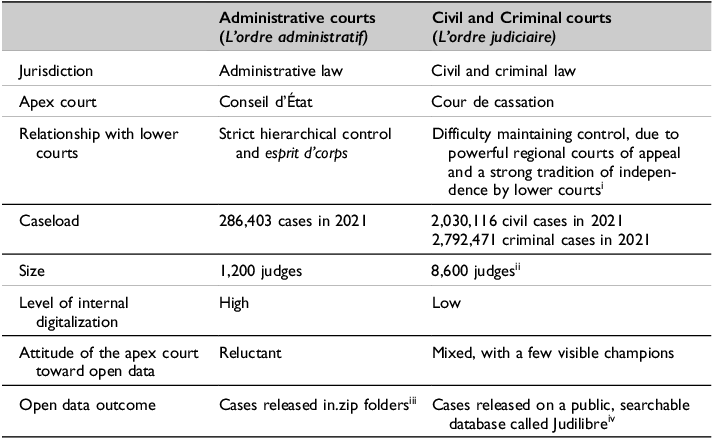

I had envisioned France as a single case, and an unexpected turn was that it turned out to be two case studies. The French administrative courts (l’ordre administratif) are separate from the civil and criminal courts (l’ordre judiciaire), and these two legal orders responded differently to the 2016 mandate that they put their decisions online. The Conseil d’État (the apex administrative court) was much more wary of releasing court decisions than the Cour de cassation (the apex civil and criminal court), where visible champions tied their careers to the success of the open data initiative. Like others, I found comparing the two sides of the court system “surprisingly productive” in understanding the dynamics of reform and resistance in a single national context (Pavone Reference Pavone2022, 97).

The Magic Moment: The 2016 Law for a Digital Republic

Articles 20 and 21 of the Law for a Digital Republic, which committed France to “releasing court decisions to the public, free of charge, with respect to the privacy of the people involved,” were a shock to the legal profession.Footnote 20 These articles were a last-minute amendment to a broader bill on open dataFootnote 21 and information technology spearheaded by the (then) Minister of Digital Affairs, Axelle Lemaire.Footnote 22 Although selected court decisions had been available on the government-run Légifrance website since 2002, the suddenness and scale of the shift made it a sea change. Moreover, it was a sea change wrought from outside, imposed by a bill introduced by the Finance Ministry rather than originating inside the legal profession (Girard-Chanudet Reference Girard-Chanudet2023, 246).

Like many exogenous shocks, the move to publicly release court decisions was the result of “a transformative event” in a “proximate field,” France’s embrace of the open data movement (Edelman et al. Reference Edelman, Leachman and McAdam2010, 671). The idea that states should publicly release data by default swept the globe in the 2010s, powered by the notion that access to information could improve government accountability, boost civic participation, and spur innovation.Footnote 23 It was a global movement embraced by conservative governments and liberal governments alike, and which was strongly associated with the Obama administration and America.Footnote 24 “Open data represents a major governing innovation,” Beth Noveck, the director of the White House Open Government Initiative from 2009 to 2011, wrote in 2017. It is “a potentially important tool for advancing human rights and saving lives … a distinctly twenty-first century approach borne out of the potential of big data to help solve society’s biggest problems” (4).Footnote 25 On the international stage, the United States became a founding member of the Open Government Partnership in 2011, a voluntary association aimed at getting governments to release information “to promote transparency, empower citizens, fight corruption, and harness new technologies to strengthen governance” (quoted in Piotrowski et al. Reference Piotrowski, Berliner and Ingrams2022, 1). France was swept up in these broader global currents, creating data.gouv.fr to release government datasets in 2011 and joining the Open Government Partnership in 2014 (Dumoulin Reference Dumoulin2022, 146).Footnote 26

Inside the French state, a group of “digital reformers” joined the Socialist government after François Hollande’s 2012 election and emerged as key advocates of open data (Bellon Reference Bellon2021, 32). In contrast to the elite corps of École nationale d’administration (ENA), graduates who formed the backbone of the French bureaucracy after the Second World War,Footnote 27 the digital reformers had a different trajectory into government (Bellon Reference Bellon2022, 277). They had not necessarily graduated from the ENA and had closer ties to business, often rotating into government jobs after time in the private sector. What they shared was a distinct worldview: an interest in combating “bureaucratic rigidity” and making a “digital republic” real, as well as a shared sense of being marginalized inside government (Bellon Reference Bellon2022, 25–26). It was this group who championed the 2016 Law for a Digital Republic,Footnote 28 a law they remember as an uphill battle. George-Etienne Faure, one of Axelle Lemaire’s key advisors in drafting the law, recalled that “[it was] the digital people against the rest of the world. I was very, very alone” (quoted in Bellon Reference Bellon2022, 263). It took significant political maneuvering to get the law passed,Footnote 29 aided by external pressure from pro-transparency civil society groups such as Regards Citoyens (FR_2; FR_4).Footnote 30 “It was a magic moment we had in 2015, 2016,” one self-identified digital reformer told me. “A perfect matching of ideas and hopes” (FR_6; see also FR_2).

Part of the magic moment was that the idea of opening government data held appeal across the political spectrum, such that the Law for a Digital Republic passed with an overwhelming majority in both the Senate and the National Assembly. “Everyone could find something [in the law] for them,” a bureaucrat later said. This “matter was not all that political” (FR_6). For the French right, releasing government data was a way to fuel economic growth by creating business opportunities to analyze it.Footnote 31 And for Hollande, and more broadly for the French left, the “right to knowledge” was a “fundamental principle of democracy.”Footnote 32 Making more information available to citizens was also meant to usher in a new era of democratic engagement and public participation.Footnote 33 In fact, Articles 20 and 21 on access to court decisions were introduced in the Senate by the French left—Corinne Bouchoux (Ecologist Party) and Axelle Lemaire (on behalf of the Socialist government)Footnote 34 —passed in the slipstream of the broader law.

In hindsight, there were signs of why extending open data to court decisions would prove controversial. Articles 20 and 21 came into law the same year the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was passed, a harbinger that privacy was an ascendant priority in Europe. Article 21 was caught on the cusp of this transition. It laid down a principle of releasing court decisions “to the public free of charge, while respecting the privacy of the persons concerned,” which teed up a tension between privacy and transparency without resolving it (Dumoulin Reference Dumoulin2022). Yet privacy was already very much present in the political conversation. It was a recurrent theme of the Senate debate, which became heated enough that Bouchoux implored her colleagues not to give in to “false fears” (Senate 2016).Footnote 35 Perhaps even more significant, making court decisions freely and publicly available was an ambitious commitment made without assigning responsibility for implementation to anyone in government. And even though the first President of the Cour de cassation publicly hoped that “one day all French case law will be online and accessible to all” several months before the passage of the law (“Interview de Bertrand Louvel” 2016), no such support was forthcoming from the Council of State (Dumoulin Reference Dumoulin2022, 168).

The Fight Over Predictive Justice: 2016-2019

Following the passage of the Law for a Digital Republic, debate raged within the French legal profession between 2016 and 2019 over the merits and risks of predictive justice (justice prédictive).Footnote 36 As futuristic as predictive justice sounds, what it referred to was simply the use of data analytics to analyze patterns in past, similar court decisions and offer statistical predictions of likely judicial outcomes. In fact, it was start-ups who popularized the term “predictive justice” to attract attention to raise money, and sell their product.Footnote 37 As one interviewee explained, “launching a start-up, it’s also about being heard … with the term predictive justice, at that time, you [could get] an hour with a major lawyer, the managing partner of a huge firm, and then sell something” (FR_14).

The phrase “predictive justice” provoked strong emotions, especially fear, fueling what social movement scholars call a “contentious episode” between 2016 and 2019. These three years were a period marked by a “shared sense of uncertainty/crisis regarding the rules and power relations” inside the legal profession as well as “sustained mobilization by incumbents and challengers” (Edelman et al. Reference Edelman, Leachman and McAdam2010, 671). As one civil society transparency activist remembered, “it was 2016, and we were waiting for the decrees (décrets) of how to apply this law, which never came.” (FR_4).Footnote 38 Instead, the Ministry of Justice enlisted a law professor named Loïc Cadiet to lead a task force on how best to “balance the logic of opening data to the public” with “the imperative of protecting the privacy of individuals” (Cadiet Reference Cadiet2017, 7). As Cadiet and his team worked, different parts of the legal profession began mobilizing to influence the outcome.

Two loose-knit coalitions emerged, pitting “entrepreneurs of innovation” against small-c conservatives, committed to preserving the status quo. Although French sociologists differ slightly in where they draw the boundary between the two groups,Footnote 39 there was a coalition in support of change that shared an ideological commitment to transparency, an interest in technology, or both. Technophiles and transparency advocates could be found in the business bar and legal academia (Moritz and Léonard Reference Moritz and Léonard2020), though the core of this coalition was comprised of the digital reformers inside the state, the OpenLaw association,Footnote 40 and a handful of legal technology start-ups. In contrast, the status quo coalition included most lawyers outside of Paris or serving individual clients, the Conseil national des barreaux (the national bar association or CNB), legal publishers, a good number of legal academics, and many (though not all) judges.

Why were relations between these two coalitions so contentious that the French media would call it “an open war?” (Iweins and Loye Reference Iweins and Loye2019)? One answer is that there were significant economic interests at stake. New legal technology start-ups self-consciously set out to “disrupt the old world” (FR_22), including a long-standing relationship of trust and mutual economic advantage between legal publishers and the courts.Footnote 41 Before 2016, legal publishers paid a licensing fee to courts to select and publish the most important decisions and would sell the resulting volume, often alongside commissioned commentary from legal academics. As one legal publisher put it:

The publisher is like a go-between, he’s the one who puts things in perspective … the word “publisher” means knowledge transformer. So when it comes to law, the incoming flow is legislation and rulings, and you have to give meaning to all this incoming mass. The publisher’s job is to give meaning, to select what’s important, and to discard what isn’t (quoted in Girard-Chanudet Reference Girard-Chanudet2023, 217–18).

The creation of a free, comprehensive, publicly available database of court decisions would fundamentally transform this model in which for-profit companies were the primary distributors of legal decisions. Nor did it take long for tensions between old commercial interests (legal publishing) and new commercial interests (legal tech start-ups) to enter the legal system. As an employee at a start-up recalled, “we were two months old when we started receiving the first cease-and-desist letters [from legal publishers]. … In August 2016, we had zero clients, but we were receiving cease-and-desist letters.” (FR_1).

Many lawyers also feared that legal tech products capable of analyzing vast numbers of court decisions would threaten their livelihood. Outside Paris, the practice of law was noticeably less lucrative,Footnote 42 and talk of “predictive justice” fueled anxieties that new technologies would deepen inequality in the profession if only rich lawyers could afford advanced analytical tools. At the extreme end of these anxieties, there were concerns about being replaced by robot lawyers. “For the CNB [the French bar association] at that time, it was already the big replacement issue,” one lawyer remembered. “That is to say that if there is some predictive justice, that is the end of the lawyers” (FR_19; see also Girard-Chanudet Reference Girard-Chanudet2023, 112).Footnote 43 Certainly, the stakes felt high. Christiane Féral-Schuhl, the President of the CNB between 2018 and 2020, publicly declared that “the future of justice [was] at stake” (Marraud des Grottes, Reference Marraud des Grottes2020).

In this period of data scarcity, when the first court decisions had yet to be publicly released, a few high-profile start-ups moved aggressively to establish themselves in the marketplace. Particular controversy swirled around a company named Doctrine, as observers wondered how a recent market entrant could advertise access to 9 million court decisions compared to just 2 million decisions on Dalloz and 2.9 million on Lexis Nexis, two of the biggest legal publishers (Iweins and Loye Reference Iweins and Loye2019). A 2018 investigative report in Le Monde revealed that Doctrine had been using fictitious email addresses oddly similar to those of law firms or academic institutions to request decisions directly from the courts (Chaperon Reference Chaperon2018).Footnote 44 Although Doctrine’s founders publicly blamed the made-up email addresses on low-level staff, reporters dubbed the approach a “pirate strategy” and noted that it raised hackles among many legal professionals (Iweins and Loye Reference Iweins and Loye2019).

Yet the politics of backlash, defined as resistance by those “declining in a felt sense of power,” ran deeper than divergent economic interests (Mansbridge & Shames, Reference Mansbridge and Shames2008, 625) A clash of “deep core beliefs” divided the two coalitions, as the French sociologist Laurence Dumoulin astutely points out, and these beliefs were intertwined with both personal and professional identity (Reference Dumoulin2022, 184–191).Footnote 45 The status coalition believed deeply in “the importance of statutes, tradition and the sacredness of institutions,” valorized moving slowly, and subscribed to the notion that judicial data belongs to, and thus should be managed by, legal professionals (Dumoulin Reference Dumoulin2022, 184). In contrast, the coalition in favor of change saw court decisions as public data and valued innovation, the market economy, and speed. The election of Emmanuel Macron in 2017 gave momentum to the change-makers, as Macron himself exemplified the power of neophytes, disruptors, and “the qualities associated with youth: audacity, ambition, dynamism and energy” (Dumoulin Reference Dumoulin2022, 156). From the start, start-ups were core to Macron’s economic strategy and political vision (FR_6). “I want France to be a start-up nation,” he told the country in 2017, meaning “both a nation that works with and for start-ups and a nation that thinks and moves like a start-up” (quoted in Dumoulin Reference Dumoulin2022, 156).Footnote 46 Because Silicon Valley is the worldwide capital of start-up culture, contention over court decisions soon became a proxy for a deeper fight over the “degree to which France wants to be part of a globalized world in which people express themselves in English” (Dumoulin Reference Dumoulin2022, 194). Bilingual legal professionals accustomed to working across borders, such as Paris-based business lawyers or legal tech-entrepreneurs,Footnote 47 were the most audible champions of open data. By contrast, French-speaking lawyers and judges with domestic careers tended toward skepticism.

The emotional valence of the two coalitions was also quite different. In contrast to the excitement expressed by start-up founders about a big data revolution, the status quo coalition was bound together by fears about what a new world of predictive justice might entail (FR_6). Rank-and-file judges were particularly intimidated by the prospect of judicial profiling (Benesty Reference Benesty2019; Moritz and Léonard Reference Moritz and Léonard2020; FR_14; FR_19), which felt close at hand. A tech-savvy lawyer had published a blog post in 2016 documenting substantial differences in deportation rate between administrative judges,Footnote 48 and the choice to call out individual judges by name and to raise questions about judicial bias sent shock waves through the profession. “The shitstorm started,” he later wrote, a few hours after the post went live, as he stated to receive angry emails from judges across France (Benesty 2019).Footnote 49 Being a judge in France had traditionally been a low-profile, private occupation, as is true in many civil law systems, and judges were by-and-large wary of intense public scrutiny of their records.Footnote 50

Professor Cadiet’s task force, then, faced the delicate task of mediating a high-stakes conversation between different segments of the legal profession with divergent worldviews.Footnote 51 However, its composition was heavily stacked toward “the main institutional players in the world of justice,” especially judges and officials from the Ministry of Justice (Girard-Chanudet Reference Girard-Chanudet2023, 251).Footnote 52 This committee composition led to a report that stresses the need to balance privacy and transparency, foreshadowing limitations on open data to come (Dumoulin Reference Dumoulin2022, 170). Following what some called a “lobbying campaign” by the Cour de cassation,Footnote 53 the report also recommends that the Cour de cassation and the Conseil d’État implement the 2016 law (Girard-Chanudet Reference Girard-Chanudet2023, 255).Footnote 54 Yet the Cadiet report was only advisory. Legally, the key turning points came in 2019 and 2020 when the open-ended commitment to opening up court decisions made in the Law for a Digital Republic became concretized through follow-up laws and décrets.

Rollback and The Road to Implementation: 2019–2021

In 2019, Article 33 of the Justice Reform Act, a major omnibus piece of judicial reform legislation, wrote the first limits on judicial transparency into law. Specifically, Article 33 prohibited any type of data analytics that reveals the identity of individual judges to compare or predict case outcomes. This was the first example of such a ban anywhere in the world, and sufficiently unusual the American legal press called it “coercive censorship” (“France Bans Judicial Analytics” 2019). Within France, too, some advocates of open data saw the 2019 shift as a reduction of ambitions and “a real step back” (FR_6; see also FR_21). The co-founder of the start-up Predictice publicly fulminated that “these kinds of kind of laws are a disgrace for a democracy … A lot of [French] congressmen claim to be pro start-ups, it’s time to prove it” (quoted in “France’s Controversial Data Ban” 2019). In addition, a group of French deputies and Senators filed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Article 33. They argued that better knowledge about judges would promote equality between litigants and was in keeping with the principle of an open court. However, the lawsuit was unsuccessful, and the ban remained in place.Footnote 55

Rolling back the broad commitment to judicial transparency made in 2016 was a victory for those who wanted to preserve the status quo, especially judges. Interviewees agreed that a ban on judicial analytics was seen as necessary to alleviate pressure from the judiciary, many of whom felt strongly about the need to protect their private lives (vie privée), prevent forum shopping, and maintain their independence (FR 14; FR_15; FR_21; FR_1).Footnote 56 By the time I was conducting interviews in 2022, even some supporters of open data saw limits on analyzing judges’ records as a reasonable step toward fixing a “badly written” law which was “a failure from the beginning” (FR_7; see also FR_11).

By 2019, the zeitgeist in France had also shifted toward prioritizing privacy. The GDPR came into force in 2018, with a great deal of publicity, and was widely feted as a success story.Footnote 57 Protecting privacy quickly became a central thread of the EU’s identity as a “regulatory hegemon,” as many in Europe leaned into the idea that the “EU’s greatest global influence [would be] accomplished through the norms it has the power to promulgate” (Bradford Reference Bradford2020, 24).Footnote 58 Meanwhile, on the ground, the GDPR created such “an anxious situation within the [French] administration” that “everyone is afraid” (FR_6). “The GDPR is paranoia here,” another interviewee added. Failure to protect privacy and to prevent “re-identification will take you straight to I don’t know where … prison. Nobody wants to go to the penitentiary” (FR_22). Open data activists felt the shift in the political mood acutely.Footnote 59 “We are being hit left and center with the data protection privacy act,” a transparency activist with a Europe-wide focus observed. “It’s now our biggest challenge. By far. It’s resulted in court documents being taken offline. It is resulting in a huge backtracking across the board on transparency” (GL_11).

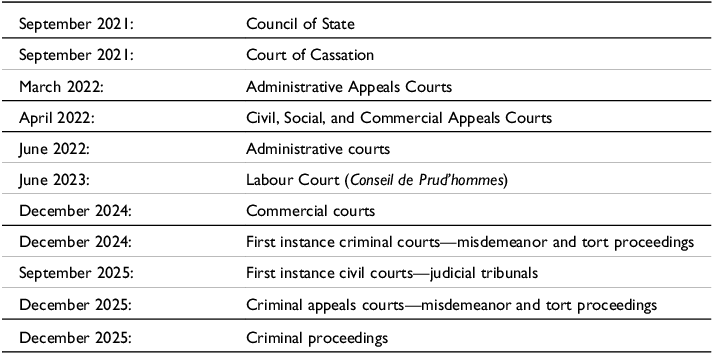

Against the backdrop of the GDPR and intensifying public criticism over the delayed release of court decisions (Bourdon et al. Reference Bourdon, Richer and Stirn2020; Perroud et al. Reference Perroud, Bourdon, Cluzel and Renaudie2020), the French bureaucracy began to act. Following the Cadiet report’s recommendations, the Ministry of Justice released a decree in June 2020 officially placing the Cour de Cassation and Conseil d’État in charge of open data.Footnote 60 Even after this initial step, the Ministry of Justice continued to face criticism for “giving an impression of disinterest” in open data (Mathis Reference Mathis2021). The turning point was a lawsuit filed by Ouvre-boîte, an open data advocacy NGO, which culminated in a 2021 Conseil d’État decision faulting the Ministry of Justice for failing to release a timely implementation schedule (Adam Reference Adam2021).Footnote 61 Under pressure on multiple fronts, the Ministry then released a publication schedule for court decisions in April 2021 (Table 1).

Table 1. April 2021 Timeline for the Release of Court Decisions (Ministry of Justice 2021)

Five years after the Law for a Digital Republic, then, a plan was finally in place, detailing who would oversee implementation and setting milestones along the way. Still, a great deal of work lay ahead for the courts to work out the mechanics of how to collect and release mass quantities of decisions, and to determine how much to redact each document to protect litigants’ privacy. The accountability imposed by the timeline also amplified fear of failure, at least in some quarters. “I’m really worried that it won’t work, that’s obvious,” a judge at the Cour de cassation told a French researcher in 2021. “Because there’s a lot at stake. That we won’t make it in terms of schedule, and also that we won’t make it in terms of volume, that we won’t meet our targets. Because we could really fall on our faces” (quoted in Girard-Chanudet Reference Girard-Chanudet2023, 257).

Variation in Implementation: 2022–2023

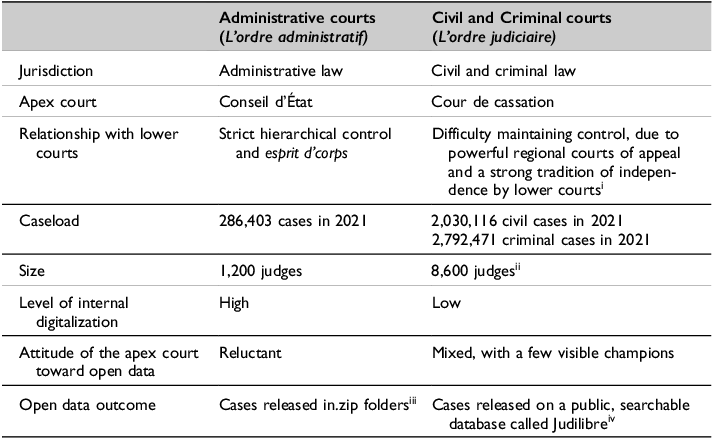

The publication of the timeline ushered in a less fraught phase of implementation as the Conseil d’État and the Cour de cassation accepted that continued inaction was untenable and legal tech companies evolved into established players. At some point, it is “just business as usual,” one start-up employee observed (FR_14). The first deadlines were also met, with decisions from both apex courts and the courts of appeals placed online by the end of 2022. By the time of my fieldwork in 2022–2023, however, it was clear that the administrative and judicial branches of the court system had taken markedly different approaches to implementation (Table 2).

Table 2. Open Data and the Two Sides of the French Court System

iOn how lower court judges prize their independence, see Pavone (Reference Pavone2022, 113). Some of this institutional culture is surely transmitted through education. Judges in the civil and criminal courts share the experience of being trained at the École nationale de la magistrature after passing a national judicial entrance exam. In contrast, administrative judges have typically attended the Institut national du service public (formerly ENA) or were recruited from a local law school.

ii Girard-Chanudet (Reference Girard-Chanudet2023, 181-82).

iii Available at https://opendata.justice-administrative.fr/

iv Available at https://www.courdecassation.fr/acces-rapide-judilibre

The Conseil d’État released lower court decisions as a data dump, putting them online as individual .xml documents organized in .zip folders by administrative court and by month. The lack of a search engine or user interface, however, made these decisions hard to use for anyone without significant technical skills. Interviewees suggested that there was “a will behind” this approach (FR_10), specifically “it was done on purpose to make [the information] difficult to use” (FR_11). One reason why people think this is that other options were available. Judges in the administrative courts have access to an internal database of cases called Ariane Archives, which they routinely use for legal research, and which could have been made public.Footnote 62 It is also hard to tell if what is online represents the entirety of the administrative docket or if decisions might be missing. As law professor Frédéric Rolin wrote on LinkedIn in July 2023, “I have a feeling that only a very partial selection of judgments is published … decidedly, when it comes to open data, we can do better.”Footnote 63 Although it is possible that future projects could improve usability or assuage concerns about the completeness of the public record, observers agree that the administrative courts see themselves as having finished complying with the 2016 law (FR_11; FR_21).

By contrast, the Cour de cassation took a more ambitious approach. They created an open data group of about twenty staff within the court and gave them responsibility for building a public-facing database.Footnote 64 For the constituency waiting for new data, especially legal technology firms, the open data group worked impossibly slowly.Footnote 65 They had to wait six years after the 2016 law for the first significant expansion of the public record: the release of appeals court decisions in 2022. From the court’s perspective, however, the pace was deliberate rather than slow and reflected a choice to proceed with maximum caution (FR_13). As an academic with close ties to the courts put it, “Rome wasn’t built in a day. And France is not China. It isn’t a military-style administrative culture” (FR_15).

There were technical, organizational, and intellectual reasons for the Cour de cassation’s considered pace, all of which are likely to surface in other court systems as well. First, the Cour de cassation faced significant technical challenges in collecting and anonymizing millions of court decisions a year. Unlike the administrative courts, the civil and criminal courts did not have their own internal database of court decisions, so they had to build the capacity to manage large amounts of information from scratch.Footnote 66 Second, the judges seconded to the open data group regularly rotated back to other work, and it was hard to sustain momentum and transfer technical knowledge across personnel changes (FR_22; FR_23). At times, there were also shifts in approach depending on who was in charge (FR_25). Finally, the Cour de cassation agonized over the proper balance between privacy and transparency. For them, these were competing values and, as the apex court, they were the actor with the remit and legitimacy to balance them. There was a massive discussion inside the court about how deeply to redact cases and how to do it. They had relied on a team of about fifteen annotators, mostly female civil servants at the end of their careers, to add a layer of human review to the anonymization process for the decisions from courts of appeal.Footnote 67 But this strategy had obvious scale limitations, and they were still debating how to manage lower court decisions during my fieldwork in 2022–2023.

Despite these challenges, the Cour de cassation celebrated a significant milestone when the first lower court decisions went online in December 2023. In contrast to the silence that accompanied the release of administrative lower court decisions, Edouard Rottier, a Cour de cassation judge who had served multiple stints in the open data group, publicly celebrated the achievement, saying, “I’d simply like to emphasize that this French model and on this scale is unique in Europe. … In Europe, most countries choose to publish a selection of their case law…. to our knowledge [this] is the only one of its kind [database] in the world, free of charge and easy to use” (Rottier et al., Reference Rottier, Talon and Wachenheim2023).

Why was open data more of a priority for France’s civil and criminal courts than for the administrative courts? Quite simply, there were champions of open data at the Cour de cassation who saw the benefits for the institution, and no one comparable at the Conseil d’État. Recall that the first President of the Cour de cassation, Bertrand Louvel, expressed support for the principle of releasing court decisions to the public even ahead of the 2016 Law for a Digital Republic. Louvel and other advocates for open dataFootnote 68 viewed it as a way to promote legal uniformity across France, ensuring that cases would be consistently decided regardless of where they were heard. Louvel talked publicly about the court’s “mission to harmonize jurisprudence” (quoted in Léonard and Moritz 2020, 118). This theme routinely resurfaces as one of the primary advantages of releasing lower court decisions, including in a 2022 report commissioned by the Cour de cassation (Cadiet et al. Reference Cadiet, Chainais and Sommer2022).Footnote 69 Indeed, the Cour de cassation has long seen legal uniformity as central to its role as “guardians of the temple” responsible for ensuring the equality of all before the law (Léonard and Moritz 2020, 118).

Beyond the pursuit of legal consistency, advocates for open data at Cour de cassation also saw an opportunity to strengthen their authority over a judicial hierarchy in which lower judges and powerful courts of appeal have a long history of independence (Pavone Reference Pavone2022, 113). At times, the goal of bringing lower court judges into line has been explicit. For example, the 2022 report commissioned by the Cour de cassation points out that open data could help quantify how often lower court judges resist following Cour de cassation decisions (Cadiet et al. Reference Cadiet, Chainais and Sommer2022, 117). Last, open data was seen within the Cour de cassation as a spur to an overdue process of digitalization. The civil and criminal court system did not have anything comparable to Ariane Archives, so open data was an opportunity to develop a comprehensive case database for the Cour de cassation and the Ministry of Justice’s own use as well (FR_17).Footnote 70 Analyzing court decisions could help identify disagreements, silences, and ambiguities in the law (Cadiet et al. Reference Cadiet, Chainais and Sommer2022), with the idea that the Cour de cassation could then address them.Footnote 71

By contrast, the Conseil d’État was widely acknowledged to be reluctant to release administrative court decisions (FR_1; FR 6; FR_10; FR_16; FR_21; FR_22). As one judge told me, “we were very happy in our world with everyone not knowing all of our decisions” (FR_21). Unlike the Cour de cassation, the institutional opportunities presented by open data had no analogue at the Conseil d’État. The administrative courts already had an internal database, Ariane Archives, and there was no need to cement the authority of the high court. On the contrary, the administrative courts are known for strict hierarchical control and a system in which “the Conseil d’Etat manages everything … it’s an army” (FR_22; see also Pavone Reference Pavone2022, 100). In such a hierarchical system, there were concerns that making lower court decisions widely accessible would upset a hierarchy of jurisprudence in which higher court decisions were seen as inherently more important.Footnote 72

In addition, open data ran into the Conseil d’Etat’s conservative organizational culture.Footnote 73 As socio-legal scholars have observed, courts “that prioritize the past over the present … [and where] innovation or change is discouraged” rely on tradition as a key source of legitimacy (Grisel and Shirlow Reference Grisel and Shirlow2025, 151). Conservative court cultures require good reasons for deviating from past practices and, in the case of open data, an innate conservativism at the Conseil d’État was amplified by the feeling that reforms were being foisted upon the court. The Law for a Digital Republic “came from the outside,” one judge told me, pushed by “actors who were … very badly perceived” inside the Conseil d’État (FR_21). After all, the Conseil d’État is an elite institution accustomed to being the “engine of the French state” and at the heart of the law-making process (FR_10). Being sidelined in 2016 had lasting consequences, in the sense that open data never felt like a homegrown idea and struggled to win support inside the court.

In lieu of public credit-claiming, representatives of the Conseil d’État can instead be heard articulating a vision of justice as a humanistic craft that justifies existing practices. The central plank of this narrative is that justice needs to center on human judgment. Here is how Thierry Tuot from the Conseil d’État put it in October 2023: “Justice is not a mechanical science, it’s a craft … [that] can never, ever be entrusted to a mechanized third party.” Implicit in the notion that justice is a craft is the idea that legal expertise remains critical, especially compared to math or computer science. As Tuot goes on to say, “there isn’t science in our business … it can’t be mathematized … [or] reduced to equations.” A certain wariness about technology is also embedded in this worldview, or at least the idea that technology is primarily useful if it saves humans time. Artificial intelligence can “rehumanize us” rather than “dehumanize us,” in Tuot’s formulation, by giving judges more time to dispense justice (Conseil d’État Reference d’État2023).

Reinventing Cultural Scripts and French Legal Identity

Beneath seven years of debate over open data lies a deeper contestation over what the French way of justice entails. As in many countries, France is a place where legal institutions are a treasured part of the national heritage (patrimoine). It is also a place where a persistent strand of political culture emphasizes the importance of leading rather than following and, particularly, not following America. Although anti-Americanism waxes and wanes, one impulse is to define the “French way” forward in opposition to what America is doing. In her investigation of diversity in the French judiciary, for example, legal scholar Mathilde Cohen observes that “American has become a shorthand for ‘un-French,’ a rhetorical tool to keep an uncomfortable thought at a safe distance” (Reference Cohen2018, 1567).

Predictive justice cut to the core of France’s legal identity because what was at stake, at least for some people, was the future of civil law itself. One judge from the Conseil d’État framed “the issue of predictive justice” in 2023 as a “confrontation of models between … our continental law model and the common law model.”Footnote 74 The fear was that making lower court decisions widely available would push France toward common law because precedents would be increasingly cited and taken seriously.Footnote 75 Predictive justice was also strongly associated with America. “For the record,” a report commissioned by the Cour de cassation noted in 2022, “predictive justice … comes from American legal practitioners who have evolved in a legal system where court decisions [are] the main source of law [and] particularly unpredictable … consequently, there is a strong need for prediction” (Cadiet et al. Reference Cadiet, Chainais and Sommer2022, 92).Footnote 76

The 2019 ban on judicial analytics, seen from this perspective, was a course correction designed to defend and reassert Frenchness. Indeed, observers considered it “very typically French” (FR_17; see also FR_1) in the sense that it reflected a long tradition of imagining the identity of individual judges to be unimportant. This idea is typically traced back to the eighteenth-century French political philosopher Montesquieu, particularly his famous quote that judges should be “the mouth that pronounces the words of the law” (quoted in Lasser Reference Lasser2004, 37). By 2022, even some start-ups had accepted that data analytics were somehow “un-French,” or at least had come to the pragmatic conclusion that casting themselves as part of a homegrown tradition was key to their success. In their words, “we’re not that interested in statistics, it’s just not the French way, I guess. … Today, I think our role is to ease tempers and calm everyone down, and show that what we are doing is providing high value-added services…with respect to French traditions, customs and fears” (FR_1).

Debates over how the rise of big data and artificial intelligence will (or should) shift the French way of law did not end in 2019. Instead, discussion inside the legal profession has evolved to echo a broader national dialogue about whether France should lead through regulation or innovation. This topic fractures the legal profession along similar lines as the earlier debate over predictive justice, with traditionalists often championing regulation. Thierry Tuot from the Conseil d’État made the case for leading through regulation strongly in 2023:

We don’t have Silicon Valley, but we do have the GDPR … we don’t say it enough, European normative imperialism works. … And that’s the part we have to play today, to show the world that the European standard of humanism and mastery in artificial intelligence can become the world standard. It’s not optimistic, it’s ambitious, but it’s proud and it’s up to the French” (Conseil d’État, Nuit du Droit 2023).

The other side sees it as a mistake to over-emphasize regulation.Footnote 77 As one legal tech founder told me, “this is a problem with Europe … they are so cautious. And this is why we lag behind America and China because [whew] a lot of rules and finally nothing happens” (FR_8). Central to this debate is the question of how France can best assert global power and influence in the twenty-first century. Leading through regulation is a strategic choice under consideration, even one that has become the prevailing European approach, making law a key part of soft power as well as an arena for competition and differentiation.Footnote 78 This places legal professionals at the center of a critical national conversation about French national identity and geopolitical strategy.

Conclusion

On one level, France’s fight over open data is the story of an arrested revolution in which defenders of tradition effectively protected existing practices and status hierarchies. Despite consternation over dystopic future possibilities, the French legal profession came through the kerfuffle over predictive justice with the legal hierarchy intact. Life for most French legal professionals has continued as usual, albeit with a few new tools for legal research provided by a handful of legal tech companies. To some extent, this is no surprise. Professions are adept at defending their turf from interlopers and, as socio-legal scholars Yves Dezalay and Bryant Garth point out, legal revolutions often start out attacking legal hierarchies and end up reproducing them (Reference Dezalay and Garth2021). Backlash is also endemic to transparency, especially when what is being made public threatens the reputation or interests of powerful people. In the French case, the backlash was supercharged by the post-GDPR rise of privacy as part of the EU’s geopolitical brand. Privacy proved a flexible frame, sometimes reflecting genuine concern about the need to protect private life and other times used strategically to shield powerful political and economic actors from public scrutiny.

Yet a deeper, slower transformation may be ongoing. First, we need grassroots research investigating how French lawyers use the judicial decisions already at their disposal. Do they primarily search for cases individually, mirroring how they would have used reference books, or are they beginning to use statistics to facilitate forum shopping, shape client expectations about case outcomes, or decide which legal arguments are most likely to be effective? Equally important is investigating the oft-invoked (and little tested) argument that greater transparency will improve the public standing of courts, a particularly pressing question at a time of declining public trust in many court systems.

Second, France’s approach to judicial transparency continues to evolve. As of this writing, many more lower court decisions are scheduled to be released in December 2025, at which point the Cour de cassation’s Judilibre database will expand by a million decisions annually (Cour de cassation 2025, 27). A key unresolved question is how deeply these decisions should be redacted. Even as a 2024 Senate report on artificial intelligence and the legal profession celebrated open data as a “valuable achievement,” it also recommended anonymizing the names of judges and court clerks before publicly releasing court decisions (Frassa and La Gontrie Reference Frassa and de La Gontrie2024, 17 and 14).Footnote 79 Meanwhile, some would also like to expand public access to other types of judicial documents beyond court decisions, an idea floated in a bill proposed to the National Assembly in 2025 (Latombe Reference Latombe2025). These debates show that the boundaries of judicial transparency are not entirely settled, and that further negotiation lies ahead for the French legal profession.

Beyond France, this episode highlights the challenges that technological change will pose to legal professions around the world. This is especially true in the era of generative AI, which decisively arrived at the end of my fieldwork with the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022. We can expect to see technology expose and catalyze schisms in the legal professions that echo, if not directly mirror, some of the fissures we saw in France over open data. Tensions between upstart versus establishment players, or between a domestic-oriented wing of the profession and a globalized one, seem likely to recur. And wherever competing values face off, such as privacy and transparency in the French case, an underlying clash of both interests and identity may lie underneath. Mapping these cross-cutting coalitions reminds us that countries are rarely centralized and unitary, even if researchers often treat them that way for convenience, and that the legal profession itself is an important arena for determining how (and how much) technology should change society.

France’s experience also illuminates a set of policy challenges that legal systems worldwide increasingly face: how many court decisions to make publicly available, how much to redact them, and who should get bulk access to them. These decisions are made by people in the legal profession, often under pressure from legal technology firms who see a business opportunity in legal data. An emergent cross-national theme is that courts often want to control data they see as “theirs,”Footnote 80 a stance which pushes them beyond adjudication into a new role as managers of information. Despite the open data movement’s American origins, it is worth underscoring that this is not an arena where America leads. Although access to legal information is only one issue area, it aligns with a broader observation that the era in which legal ideas and institutions were a key American export may be giving way to a more decentralized and multicultural twenty-first century (Liu Reference Liu2023, 697). Reminding ourselves that law is a key component of soft power also lends within-the-profession debates over judicial transparency and the datafication of law a larger geopolitical significance as sites where cultural scripts about law are challenged and reimagined.

Appendix A. List of Interviewees (France)

Appendix B. List of Interviewees (Global)