The Theoretical Limitations of Negative Partisanship (in Chile)

Let us begin with a comparative puzzle. Imagine an agnostic observer learning about the politics of Chile and Peru. In both countries, citizens distrust political institutions, reject political elites, and express deep dissatisfaction with political parties (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2005; Luna Reference Luna2014; Meléndez Reference Meléndez2019; Bargsted and Maldonado Reference Bargsted and Maldonado2018). Given these similarities, such an observer might expect equally chaotic political landscapes. Yet the outcomes diverge: Peru displays high volatility and limited ideological stability, whereas Chile exhibits ideological continuity from the 1988 “Sí” and “No” plebiscite to the 2025 presidential election, again featuring a left-wing and a right-wing frontrunner. We argue that this divergence arises because in Chile, a substantial portion of the electorate not only rejects but also belongs to an ideological group. Ideology, in other words, functions as an identity that provides stability to electoral competition.

In our article (Argote and Visconti Reference Argote and Visconti2025), we hold that ideology is the glue that sustains stable competition in Chile. In contrast to Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025), we argue that negative partisanship, by itself, is an insufficient explanation for long-term stability. Peru exhibits high levels of negative partisanship but lacks ideological stability, whereas in Chile, the presence of ideological identity, rather than rejection alone, anchors the political system. This comparative contrast is critical: if rejection were enough to maintain stability, then Peru should resemble Chile; yet, its persistent instability demonstrates the limits of negative partisanship as a stabilizing force.

Consider the 2025 presidential race. As of August 2025, polls place two candidates with a clear ideological base as frontrunners: Jeannette Jara and José Antonio Kast, at roughly 30 percent each, together capturing about 60 percent of the electorate. From a negative partisanship perspective, Jara’s voters would be motivated primarily by anti-Pinochet sentiment, whereas Kast’s voters would be anti-communists. If that is true, then we should observe a more equal distribution of the anti-Pinochet vote among anti-Pinochet candidates (e.g., Franco Parisi, Marco Enríquez-Ominami, and Harold Mayne-Nicholls), but that does not seem to be the case. This is a regular pattern: in every presidential election since 1989, the left and the right have concentrated preferences in the first round, when multiple choices are available, suggesting that positive attachments, rather than simple rejection, drive such consolidation. This distinction between first and second rounds is crucial: rejection may be decisive in runoffs, but identity has anchored the competition in multiparty first-round contests.

The lack of success of centrist parties and candidates also confirms our claim. If rejection alone were the primary force, we would expect more electoral success from movements that position themselves at the center of the ideological spectrum, such as Amarillos por Chile, Demócratas, and Ciudadanos. In practice, however, these projects struggle to gain traction, precisely because they lack an ideological anchor that makes them identifiable to the public (i.e., either left or right). In a context where political competition is interpreted through the left–right divide for a large share of the electorate, movements without a clear ideological label lack the capacity to consolidate durable support. On the contrary, new parties have emerged with clear ideological stances, such as Frente Amplio on the left and Republicanos on the right (Visconti Reference Visconti2021), and they have had electoral success precisely because they appeal to an electorate with ideological identities. In fact, to a large extent, these parties have displaced the old ones, as they now compete for the support of ideologically driven voters who previously backed other options.

While negative partisan identities such as anti-Pinochetismo and anti-comunismo have played a meaningful role in shaping political attachments in Chile (Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser2019; Meléndez Reference Meléndez2022), relying solely on this framework to explain ideological stability presents limitations. In our article (Argote and Visconti Reference Argote and Visconti2025), we provide evidence that even the 1988 plebiscite is losing explanatory power over time. While the plebiscite was indeed a critical juncture that aligned political identities along a clear democracy/authoritarian divide, its influence appears to fade with generational turnover (de la Cerda Reference de la Cerda2022). This suggests that ideological stability in Chile is no longer sustained by historical memory, but increasingly by ongoing social dynamics and identity formation rooted in communities, families, and symbolic group affiliations that were initially catalyzed by the plebiscite. In this sense, anti-Pinochetismo may have served as an entry point to ideological identification for many; however, its ability to account for ideological persistence in Chile in 2025 is limited. What endures is not Pinochet himself, but the social processes and group identities his figure set in motion, which have outlived his persona and taken root in broader affective and moral worldviews.

Negative partisan identities are historically contingent and rooted in specific conflicts. Ideological belonging, by contrast, has a greater temporal depth because it is reproduced through family transmission and symbolic boundaries. This capacity for renewal allows ideology to endure as a meaningful identity even as particular historical antagonisms fade or transform, providing a more durable anchor of political stability.

There is also an irony in applying the concept of negative partisanship to the Chilean case. This concept was developed in contexts with strong partisan traditions, such as the United States, where positive partisan attachments are well-established and negative identities emerge as their counterpart (Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2016). In Chile, however, partisan attachments are exceptionally weak: parties consistently rank among the least trusted institutions, and partisan identification is at a historic low. In such a setting, speaking of “negative partisanship” risks overstating the role of parties and underestimating the independent force of ideology.

Importantly, we recognize that both perspectives—ideology as a social identity and negative partisanship—capture key dimensions of Chilean political behavior. Negative partisanship is undeniably powerful, particularly in shaping second-round dynamics, referendums, and moments of intense polarization. However, we do not believe that rejection alone can sustain the long-term stability of electoral competition. What anchors the system are the more complex dimensions of ideological belonging, which explains why voters consistently align with candidates from their ideological family, why centrist projects fail, and why ideological attachments endure even as parties collapse. In our view, negative partisanship and ideological identities coexist; however, the latter provide a deeper and more durable foundation for stability, while the former reinforce and intensify electoral conflict within that structure.

Rejection and Identity: Points of Dialogue

In this section, we address several statements made by Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025) and use this opportunity to engage in an academic dialogue.

First, Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025) notes the absence of lifestyle sorting in Chile as evidence against the presence of ideological identities. We agree that Chile does not exhibit the levels of affective polarization observed in the United States, which drives lifestyle dimensions, such as cultural consumption, neighborhood choice, and even marriage patterns (Mason Reference Mason2018). However, affective polarization and social identity are distinct concepts. In this sense, our evidence of symbolic boundaries, in-group affect, and intergenerational transmission suggests that ideological attachments still operate as meaningful identities. Symbolic boundaries can exist without lifestyle sorting, especially when identities develop in a context of medium to low affective polarization among the mass public.Footnote 1

Second, Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025) comments on the weakness of partisan attachments and elite cues in Chile (Luna and Altman Reference Luna and Altman2011; Morgan and Meléndez Reference Morgan and Meléndez2016). This is not evidence against ideological identity. On the contrary, it is precisely because parties and coalitions have collapsed and reconfigured—from Concertación vs. Alianza in 2009 to Frente Amplio vs. Republicanos in 2021—that the persistence of a left–right divide is so striking. Parties may disappear, but ideological belonging remains. This endurance is consistent with our argument that ideology, not partisanship or rejection, provides stability.

Third, Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025) observes that our argument relies heavily on ideological consistency and suggests that consistency alone does not constitute identity. We agree that consistency is not sufficient. However, this comment overlooks additional evidence we provide in the article: intergenerational transmission of ideology, the presence of symbolic boundaries, and patterns of in-group affect. Together, these elements suggest that considering ideology as a social identity is a coherent interpretation of the various pieces of evidence we provide.

Fourth, Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025) claims that if our account were correct, nearly half of the electorate would carry a sense of ideological belonging. We believe this is indeed the case. In fact, the presence of people with a left-wing ideological identity helps explain, for example, the consistent 30 percent support President Boric has retained even during the most difficult moments of his presidency. If voters were guided solely by rejection or anti-Pinochet sentiment, it would be difficult to understand this steady support following controversial decisions, multiple scandals, and numerous changes in policy positions. The case of President Piñera provides a mirror opposite: his approval fell to around 10 percent when the right abandoned him following the Acuerdo Por la Paz Social y la Nueva Constitución that initiated the first constitutional process in 2019. The right did not leave him because he ceased to be anti-communist, but because he failed to embody what being on the right means as an ideological identity.Footnote 2

Fifth, Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025) uses the constitutional plebiscites (Apruebo/Rechazo and A favor/En contra) as examples of mobilization rooted in rejection. However, we argue that this interpretation captures only part of these elections. Conversely, there was a clear ideological alignment in the support for both proposals. The first process, which started in 2021 and concluded in September 2022, had a progressive imprint (Palanza and Valarezo Reference Palanza and Valarezo2024), whereas the second, in 2023, was clearly more conservative (Toro and Noguera Reference Toro and Noguera2024). As we show in the next section, there is also a strong correlation between ideology and the Apruebo/Rechazo vote in 2022. Importantly, the predictive power of affirmative ideology was larger than that of anti-right (Figure 2). While it is true that many voters rejected both proposals, these voters may be motivated by other factors, such as their acceptance or rejection of the political establishment.Footnote 3 However, our article focuses specifically on voters who have an ideology (a majority of the electorate), and, as we show next, they clearly voted in line with their ideological identity in the first constitutional process, even in a unique event such as a referendum.

Finally, Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025) comments on our measurement of ideology, noting that we rely on a scale rather than a direct question of left or right identification. Our decision was based on how ideology is traditionally measured in the region (Zechmeister Reference Zechmeister2015). Using a 10-point scale allows respondents to place themselves with nuance, enabling people to select a number indicating more extreme or moderate options. However, we do find high consistency in these measures when surveying the same people two years apart. In other words, if this measure were inaccurate, we should expect a lack of reliability, which was not the case. Thus, using this scale actually reinforces our argument: even when people have the option to position themselves flexibly, the divide between left and right endures. That said, we agree that including a direct identity question as a robustness check would have strengthened the article, and we appreciate this constructive suggestion.

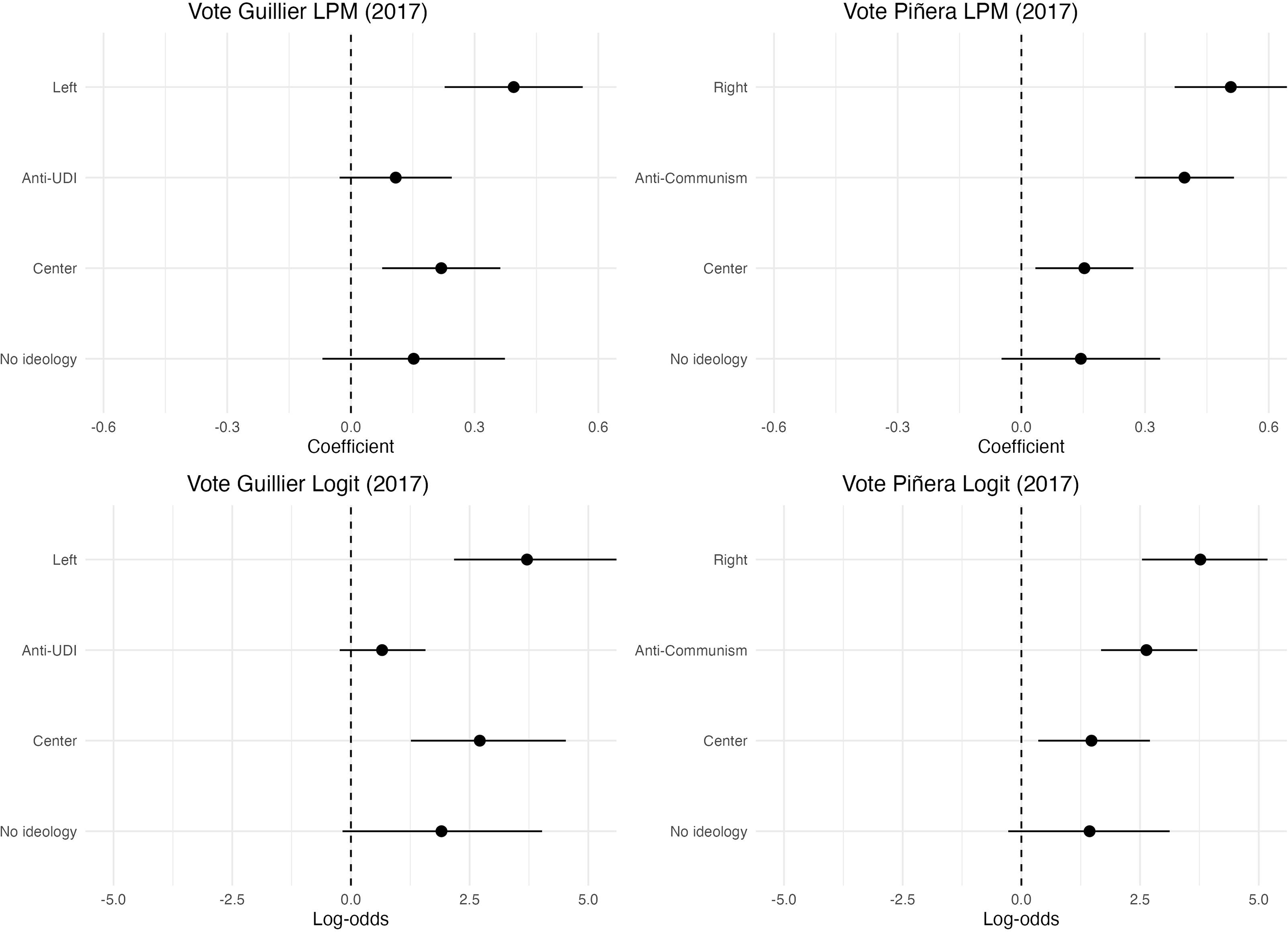

Figure 1. Ideology Versus Anti-Partisanship: LAPOP 2018.

Note: All models control for gender (categorical), education (categorical), socioeconomic status (categorical), and age.

The Empirical Limitations of Negative Partisanship

In addition to the theoretical points, Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025) provides empirical evidence to prove his point. Using the LAPOP 2018 survey and another non-public data source, it allegedly shows that anti-communism predicts voting for the right to a larger extent than affirmative ideological identification. This analysis is not correctly interpreted, because it compares coefficients of variables with different levels of measurement: one is continuous (ideology) and the other is categorical (anti-communism). Due to the nature of a marginal effect in a regression model, or a logistic regression model, the coefficient of a continuous variable will be, in most cases, smaller, because it is measuring the average effect of one additional unit on the probability of realizing the outcome (i.e., in the case of a linear probability model). If ideology is measured on a 10-point scale, where 1 is far-left and 10 is far-right, then the coefficient on ideology represents the average effect of, for instance, going from one to two, or from two to three, and so on. This approach is equivalent to comparing a coefficient for gender with one for age measured as a continuous variable, and then claiming that gender is more predictive simply because its coefficient is larger.

The more appropriate way to compare the predictive power of anti-partisanship versus affirmative ideology is by treating both variables as categorical. This also makes substantive sense because we consider ideology as a distinctive categorical variable. When doing the analysis correctly, with the same data used by Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025), a different picture emerges. We estimate the same models but with ideology included as a categorical variable. In particular we estimate how ideology, anti-communism, and a set of demographic covariates predict the reported vote for Piñera in 2017. We also added vote for the left-of-center candidate, Alejandro Guillier, as an outcome, and instead of using anti-communism as a predictor, we used “anti-UDI”; that is, respondents who do not like the party that was at the extreme right back then. We use a logistic regression and a linear probability model (LPM), which is equivalent to using OLS with a dichotomous outcome, for ease of interpretation.

When looking at the right panel of Figure 1, we observe that being right-wing is, at least, as important as anti-communism in explaining the vote for Piñera. The LPM shows that right-wing identification increases the vote for Piñera by about 55 percentage points. Even if the point estimate of right is larger, the confidence intervals of both variables overlap. In the case of Guillier, clearly left identification is more relevant than identifying as anti-UDI.

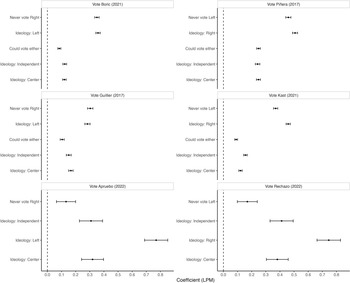

Figure 2. Ideology Versus Anti-Partisanship: Argote and Visconti (Reference Argote and Visconti2025) Data.

Note: All models control for gender (categorical), education (categorical), socioeconomic status (categorical), and age.

Fortunately, we can provide even more evidence supporting the relevance of ideology. In the data used in Argote and Visconti (Reference Argote and Visconti2025), we asked respondents the following question. “Which of the following statements do you most agree with?”: (i) I would never vote for a left-wing politician, (ii) I would never vote for a right-wing politician, and (iii) I could vote for someone from the left or the right if I like them as a candidate.”Footnote 4

We then use the answer “I would never vote for a left-wing politician” as a measure of anti- left, and “I would never vote for a right-wing politician,” as anti-right. We estimate analogous regression models with these predictors, together with ideology and demographic regressors. We used six different outcomes: vote for Guillier in 2017, for Boric in 2021, and for the Apruebo option in the 2022 referendum. All these represent a left-wing position. Likewise, we used the vote for Piñera in 2017, Kast in 2021, and the Rechazo option in 2022, as proxies of outcomes representing choices supported by the right.

Let us analyze the linear probability models (Figure 2). In the case of the left (Boric, Guillier, and Apruebo), ideology is, again, at least as important as negative partisanship in the case of Boric and Guillier, and clearly more important in the vote for Apruebo. Meanwhile, in the right-side panel, ideology is more relevant in all three models. When using a logistic regression specification in the Appendix, the results follow exactly the same pattern.

We acknowledge this is not definite proof that ideology matters more than negative partisanship. For starters, both measures are clearly correlated because identifying with the left often implies a dislike for the right. Indeed, we show in the supplementary material that the correlation between “Never Left” and “Right” is 0.59, and between “Never Right” and “Left” is 0.57. These numbers are somewhat high, but they also show that the two variables are not measuring the same construct. In sum, across several specifications and data sources, we confirm that ideology has equal or greater predictive power than either negative partisanship or negative ideology. Taken together with the evidence presented in the original article, these results strengthen our argument about the preeminence of ideology.

Common Ground

Although our perspectives diverge, there is more common ground than disagreement between the identity-based and negative partisanship approaches. Both perspectives highlight the affective and symbolic dimensions of politics, and both acknowledge that electoral competition cannot be reduced to issue preferences or programmatic coherence alone. Whether through rejection of an out-group or attachment to an in-group, citizens rely on heuristics that provide meaning, orientation, and stability in contexts of weak partisan structures. In this sense, our arguments are not mutually exclusive, as negative partisan identities may interact with and even reinforce ideological identities over time.

We also want to acknowledge and applaud Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2025) for his willingness to engage in this debate. By raising critical questions about the meaning and measurement of ideological identity, this rebuttal pushes us to clarify our conceptual framework and strengthen the empirical foundations of our claims. We share the conviction that understanding the nature of political attachments is central to explaining electoral behavior in Latin America, and we view this exchange as an important step in advancing that broader research agenda.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2025.10030

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.