Introduction

The 2024 US presidential election was the first US national election contest to take place in the age of generative artificial intelligence (AI).Footnote 1 Generative AI platforms rely on vast amounts of text to train algorithms to generate virtually instantaneous responses to user-inputted queries. As Romero, Reyes, and Kostakos explain, “This technology processes human inputs, commonly known as prompts, and generates outputs that closely mimic human-generated content, predominantly in the form of text and images.”Footnote 2 By late 2024, generative AI technology was seemingly everywhere, from stand-alone products such as ChatGPT; to embedded AI features in word-processing programs, web browsers, and search engines; to smartphones and apps with generative AI capabilities.

Despite its growing prevalence, relatively little is known about how effectively generative AI contributes to learning about politics. The 50 States or Bust! Project, data from which form the basis of this article, was launched in June 2023 in order to contribute to an understanding of the value of politically focussed AI-generated content for understanding subnational US politics. The question animating the project was, to what extent is ChatGPT useful as a research tool for exploring state- and territory-level US politics? To answer that question, in June 2023 politically focussed profiles were generated via standardized ChatGPT4 prompts for all US states and territories. Since then, the project team has conducted interviews with experts on the politics of nineteen US states. The interviews ask the experts to assess the content of the AI-generated profiles in order to gauge how effective ChatGPT is at analysing state-level politics.Footnote 3 With the caveat that efforts to secure interviews with experts from the remaining states and territories are ongoing, the project has thus far revealed that generative AI is not sophisticated enough to capture the nuances of state-level US politics. The project has further demonstrated the difficulty that generative AI has with accurately citing the sources that it references, including the propensity of AI to “hallucinate” – that is, to simply make up sources that do not exist – and the project has exposed a dearth of academic literature about most US states.Footnote 4

Notably, the expert interviews also reveal a prevalent nationalization bias in the state-level profiles, which has not previously been explored and is the focus of the remainder of this article. While the US Constitution established a federalized republic in which separate governments at the state and national levels would operate, today the distinction between these levels of government has been diminished by a half-century of nationalized US politics. Carson, Sievert, and Williamson define nationalization as “a phenomenon in which top-down forces, such as presidential vote choice or partisanship, inform voters’ decisions in subnational elections rather than candidate-specific factors or local forces.”Footnote 5 Recent scholarship finds that it is increasingly difficult to identify state and local interests as unique from national ones, particularly vis-à-vis US elections, with even local election results now affected by the public’s perception of the incumbent US President.Footnote 6 As Hopkins explains, “Since the 1970s, gubernatorial voting and presidential voting have become increasingly indistinguishable. What is more, Americans’ engagement with state and local politics has declined sharply, a trend that has unfolded more consistently over decades.”Footnote 7 The consequence of nationalization is not simply a benign shift away from parochial interests toward greater attention to national-level politics. Rather, recent scholarship reveals that nationalization exacerbates political polarization and upends the Madisonian state–federal balance of power upon which the US federal system rests.Footnote 8

Identifying the extent to which subnational political content produced by generative AI is biased toward national information is thus important for understanding the practical implications of nationalization and for evaluating the utility of generative AI to inform subnational political analysis. While questions about bias have animated previous studies of politically focussed AI-generated content, these have largely explored partisan and ideological bias or race and gender biases.Footnote 9 Previous studies have also demonstrated that it can be difficult to identify bias in the content produced by generative AI. As Zhou et al. explain,

Different from traditional AI models that are often used for classification or prediction, generative AI models are used to create new content based on patterns from the training data, making it difficult to measure the bias as there is no single “correct” output. Instead, one would need to evaluate a range of generated content for patterns that reflect bias. Moreover, new content generated by these models such as visual content can directly shape users’ perceptions, perpetuate harmful stereotypes, and even distort their beliefs, especially if the generated content is widely disseminated.Footnote 10

While documenting bias in generative AI output has been difficult in other contexts, the experts interviewed as part of the 50 States or Bust! Project had no problem identifying a nationalization bias as a feature of the AI-generated state-level political content they reviewed.

This article proceeds as follows: the next section describes the prospective risks and benefits that generative AI might pose in the context of US politics before turning to a fuller explanation of the problem of nationalized US politics. From there, this article describes the unique methodology of the 50 States or Bust! Project and discusses the experts’ assessments of the generative AI material, with a particular focus on the ways in which the state-level content is interspersed with national-level information. The article concludes by highlighting the anti-Madisonian challenge of highly nationalized political content in the context of the United States’s federal design.

Generative AI in political context

To the extent that generative AI has been the subject of study in the political context, most analysts have suggested that it poses unique dangers, especially including the potential to nefariously influence election and policy outcomes, as the platforms are able to quickly generate content that seems correct, even when it is false or misleading.Footnote 11 As one report put it, ‘Using fake, entertaining, often preposterous images to score political points is hardly new. But unlike cobbled-together Photoshop images or political cartoons, AI-generated images pack a stronger punch with their hyperrealism and can draw new attention to a political message.’Footnote 12 In a notable example, during summer 2024, when false and misleading images relating to the American presidential election appeared frequently on social-media platforms, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump posted an AI-generated endorsement by megastar singer Taylor Swift on his social-media accounts. Swift, in ultimately deciding to endorse Trump’s challenger, Kamala Harris, pushed back on the use of her likeness in this way, writing,

Recently I was made aware that AI of “me” falsely endorsing Donald Trump’s presidential run was posted to his site. It really conjured up my fears around AI, and the dangers of spreading misinformation. It brought me to the conclusion that I need to be very transparent about my actual plans for this election as a voter. The simplest way to combat misinformation is with the truth.Footnote 13

Leaders in government and industry have likewise raised red flags about generative AI and its potential to disrupt elections. For example, in mid-January 2024, the US Cyber and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) published a White Paper for US state election officials detailing the range of possible election security concerns posed by generative AI. Covering everything from “deepfake” images, to voice cloning, to social engineering, the report urged state officials to initiate processes and procedures to protect election integrity from the mischief of bad actors with access to generative AI tools.Footnote 14 That same month, the World Economic Forum issued its 2024 Global Risks Report, which listed “Misinformation and Disinformation” as the top global risk for the two years between 2024 and 2026. The report highlights upcoming elections in nations around the world, noting, “The presence of misinformation and disinformation in these electoral processes could seriously destabilize the real and perceived legitimacy of newly elected governments, risking political unrest, violence and terrorism, and a longer-term erosion of democratic processes.”Footnote 15

No one doubts that these are real risks, yet AI can also help election administrators to identify cyber threats and more efficiently manage elections.Footnote 16 Election administration in the US is decentralized and siloed. States and localities bear significant responsibility for administering not only their own elections, but also elections to Congress and the presidency. Consequently, even elections to national office, like the one held for US President in November 2024, consist of fifty separate elections (one in each state) that are managed by tens of thousands of localities.Footnote 17 AI has shown promise for helping election administrators to identify fraud and automate requests for public records.Footnote 18 Generative AI may one day soon power chatbots to answer questions at state boards of election or local voting registrars’ offices.Footnote 19

Generative AI also could provide additional, direct benefit to the electorate by helping voters to organize the significant amount of information that they need to make decisions. In the United States, all but four states – Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia, and New Jersey – hold elections for statewide offices concurrently with the quadrennial national elections.Footnote 20 This means that nearly all US voters must obtain and use both national- and state-level information when deciding their votes. Furthermore, local elections are often held on their own separate schedules, requiring voters to acquire local information at times outside the regular national election cycle. As the US Government Services Administration explains, “State and local elections can take place in any year at various times throughout the year … [H]ow the government works and who and what you can vote for depends on your state, county, or city.”Footnote 21 Generative AI might therefore be able to provide voters not only with important information about candidates and offices across the three levels of government, but also with information about where and how to participate in elections of all types.

The nationalization of US politics

Unfortunately, generative AI does not yet appear capable of providing high-quality information about subnational US politics.Footnote 22 What is more, generative AI demonstrates a bias toward national-level information, which reduces its utility for supporting state and local political engagement.

To understand why nationalized politics at the state and local levels poses a problem, it is essential to review the main features of the US constitutional system. The framers of the US Constitution created a federal system within which both state- and national-level political interests were to be represented. Constitutionally, for individuals to be able to serve in the US Congress – a national institution – they must be residents of the states they wish to represent. The states themselves are represented equally in the United States Senate, and Article II, Section 1 requires that electors selected in state-specific processes select the President. In addition, Article I, Section 4 of the Constitution grants state legislatures the power to determine the “time, place, and manner” of holding elections for Congress. In short, under the US Constitution, states play central roles in forming the national government. Moreover, the states control innumerable aspects of government power writ large. As James Madison explained in Federalist Paper #39, the national government’s “jurisdiction extends to certain enumerated objects only, and leaves to the several States a residuary and inviolable sovereignty over all other objects.”Footnote 23 In short, the framers of the Constitution expected that the national interest would emerge from the aggregation of state interests – and that the state interest itself would arise out of the multiplicity of local interests.Footnote 24

Today, there are nearly 91,000 state and local governments in the United States,Footnote 25 and estimates of the number of officials elected to serve in state and local government top 500,000.Footnote 26 State and local governments are responsible for carrying out the government functions that people are most likely to encounter in their daily lives: utility regulation, refuse pickup, traffic safety, and police and fire protection, to name just a few. Yet turnout rates in local elections are low – less than 25 percent of eligible voters in many cases – and falling.Footnote 27 In contrast, just 537 individuals are elected to the United States’ national government. And while turnout in US national elections remains low by international standards, it has risen over the last few election cycles.Footnote 28 Today, far more voters participate in national elections that have fewer direct consequences for their daily lives than participate in their state and local elections.

Recent scholarship has identified several causes for the nationalization of US politics: Americans’ identities as Americans, rather than as residents of the states in which they live; negative partisanship and affective polarization, both of which frame politics as a zero-sum partisan game; and a changing media landscape that reduces the public’s ability to follow state and local politics. Hopkins finds, for example, that people identify more strongly with America than with their home states, and that the content of their attachments is more overtly political at the national level.Footnote 29 Carson, Sievert, and Williamson likewise find that partisanship now drives election outcomes at all levels. They find that elections as local as those for the local school board have been nationalized and that “voters tend to support the same party in presidential and most subpresidential elections.”Footnote 30

Political identity and increased partisanship are both closely connected with a third phenomenon contributing to nationalization: the sharp decline in local news outlets. Multiple problems result from the diminishing number of local media outlets. These include more polarized political discourse and a lack of high-quality information to assist individuals with making political decisions.Footnote 31 However, not only has the number of total local news outlets declined precipitously over the course of the last decade, but also many of those local newsrooms that still exist are now so-called “ghost” newsrooms “existing in name only and failing to produce much original reporting.”Footnote 32 Instead, they rely on national and international wire services such as the Associated Press and Reuters to provide the content that they deliver to their readers and viewers. The 2023 report of the Medill Local News Initiative at Northwestern University offered a stark assessment of the problem:

Today, residents in more than half of all the country’s 3,100 counties either do not have a local news outlet or have only a single surviving outlet – almost always a weekly paper. These counties are often referred to as “news deserts” – defined as a community where residents have very limited access to critical news and information that nurtures both grassroots democracy and social cohesion. Three million residents live in the 204 counties without a single news source.Footnote 33

In addition, an increasing number of online news providers are now putting content behind paywalls or requiring subscriptions to access it. According to one recent study, this is especially true for local news content, including content about government; because this content is particularly of interest to readers, editors and publishers see these stories as potentially more lucrative and therefore are more likely to put them behind a paywall.Footnote 34 This paywalled content then becomes inaccessible to many people, particularly those faced with economic hardship.

In short, several factors make subnational US politics vulnerable to national-level forces. As Hopkins explains,

in a transforming media market characterized by growing consumer choice, the structure of Americans’ identities means that they are unlikely to go out of their way to seek out information about state or local politics. The interplay of Americans’ identities and changes in media markets explains the declining engagement with state and local politics.Footnote 35

Methodology

Because American politics has become increasingly nationalized over the last half-century, our expectation is that the state-level information that ChatGPT provides will likewise reflect a bias toward national-level political information. As briefly noted above, to assess ChatGPT’s utility as a research tool for understanding US subnational politics, the research team engaged in two distinct activities during 2023 and 2024. First, in June 2023, the research team generated profiles on all US states and territories using standardized prompts in ChatGPT4. These prompts were designed to provide insight into how ChatGPT would respond to inquiries about the history and politics of US states and territories. In all cases, the prompts asked ChatGPT to cite relevant academic sources. In all, this process generated fifty-six profiles.Footnote 36 The resultant profiles ranged in length from 128 words (New Hampshire) to 705 words (Alabama), with an average length of 456 words. There does not appear to be anything systematic about the length of the profiles; New Hampshire, for example, has long played an important role in presidential nominating politics, but its AI-generated profile was the shortest of all those generated by ChatGPT4, and the profile did not respond to the prompts it was given.Footnote 37 Similarly, there was also no standard format for the responses that ChatGPT generated. For example, although the prompts included seven separate questions, in the Virginia profile the questions were answered collectively; for the Missouri profile the responses were not numbered as they were in most of the other profiles.

Concurrent with the creation of the profiles, the research team solicited interviews with experts in state politics from all US states and territories.Footnote 38 The solicitation consisted of standardized-approach materials, including an email template, a list of interview questions, and informed-consent resources. “Experts” were defined as including academics, practitioners, and journalists, although, to date, all interviewees are affiliated with an academic institution. To identify experts to approach in each of the fifty states and territories, searches of newspaper articles about state politics, reviews of the state politics literature in political-science journals, and standard Google searches were used. When an expert agreed to participate, an interview with a member of the research team was scheduled at a mutually convenient time. With the experts’ permission, these interviews were recorded for analysis.

All interviews consisted of two parts. In Part 1, participants were interviewed about the politics of the respective state, using the same prompts fed into ChatGPT to guide, but not limit, the semi-structured interviews. Neither ChatGPT in general, nor the state profiles, were discussed in Part 1. The aim for Part 1 was to have a point of comparison for the state profiles generated by AI. In Part 2, participants were asked to reflect on the ChatGPT state profiles regarding the details they provided on state history and politics, and to the profiles’ engagement with academic work. The participants were also asked to provide numerical ratings between 1 (low) and 10 (high) for three dimensions of the ChatGPT profiles for their states: how well ChatGPT captured the history of the state, how well ChatGPT captured the politics of the state, and how well ChatGPT incorporated extant academic literature about the state.

Results: generative AI and nationalized state politics

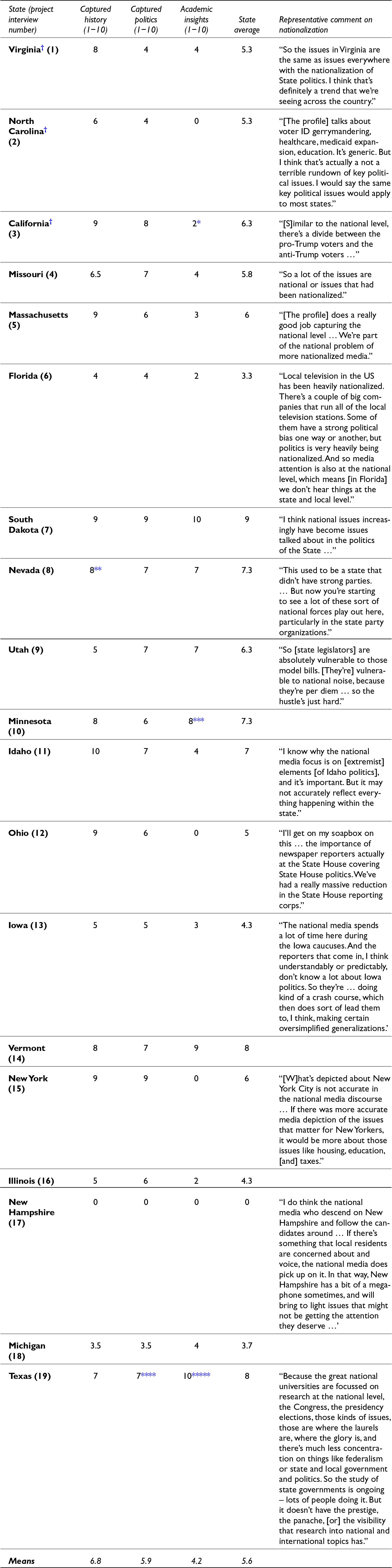

Table 1 presents summaries of the expert assessments of the ChatGPT4 profiles generated for this project. The numerical values presented in Table 1 suggest that most of the experts participating in the 50 States or Bust! Project were less than impressed with the profiles of their states produced by ChatGPT. Their ratings of the profiles’ ability to capture the history and politics of the states were on balance quite low. While the experts collectively gave ChatGPT the equivalent of a D+ grade for capturing state-level histories, their ratings on ChatGPT’s ability to provide insights about state politics – both generally and from the academic literature specifically – received failing grades from the experts. The experts overall complained that the profiles did not generally capture the nuance of US state-level politics, but in two cases – the profiles for Iowa and New Hampshire – the ChatGPT profiles truly stood out. These two states are among the best-covered by scholars and journalists given their central roles in the presidential nominating process, which should have provided ChatGPT with a large quantity of information to synthesize in generating profiles for these two states. Yet in the profile for Iowa, ChatGPT indicated that the state’s borders were established five years after statehood, a fact that is “not just counterintuitive [but] wrong.”Footnote 39 Worse still, the New Hampshire response did not engage at all with the rich political history of the state. Although University of New Hampshire elections scholar Dante Scala accepted that the state is “a bit of a niche in the political-science literature,” he would have expected something “with regard to our role in presidential nomination politics, for example, or perhaps something about the politics of New England. But no such luck.”Footnote 40

Table 1. Expert assessments of ChatGPT profiles

† The interviewee participated in the pilot phase of the study.

* Author P. Finn did not ask for this score in the initial interview, but in a later email. Email chain on file.

** Extrapolated from the interviewee’s verbal response. If this value is omitted, the average score increases to 7.5, which is not substantively different from the current value.

*** Extrapolated from the interviewee’s verbal response. If this value is omitted, the average score is reduced to 7.0, which is not substantively different from the current value.

**** Extrapolated from the interviewee’s verbal response.

***** Profile cited the work of the interviewee. High score was also tempered by the fact that “there is a good bit of research out there that I think ChatGPT could be driven to” that is not cited in the profile.

While these two examples are relatively egregious instances of the failure by ChatGPT to accurately describe the politics and governments within the US states, many other profiles likewise offered a lack of nuance when describing state-level conditions. When the scholars in the project were asked to provide commentary about how well ChatGPT covered their home states’ histories, they typically noted the general nature of the information provided. For instance, Virginia scholar Rich Meagher of Randolph-Macon College described the profile as “very much incomplete, even for a brief overview,” because “I think there’s more about that story that even a kind of generic, very introductory overview of Virginia might touch” that is not included, such as the “outsized role [the state played] in the … founding of the country.”Footnote 41

Similarly, the North Carolina profile dispenses with pre-settler history very quickly, correctly noting that it was “the last State to join the Confederacy in the Civil War” but neglecting to “really talk about the meaning of that.”Footnote 42 University of Nottingham lecturer Kevin Fahey noted that the Florida profile also skirted over pre-settler history, while simultaneously failing to mention the importance of the indigenous population in contemporary politics;Footnote 43 while for Michigan, Marjorie Sarbaugh-Thompson of Wayne State University said the profile “felt like the sort of history that you might use for an elementary-school classroom.”Footnote 44 Finally, in the case of Utah, political scientist Leah Murray thought that while in the history of the state the profile does highlight the role of the Mormon pioneers seeking religious freedom, it could have done a better job to “capture that fight” of a group of “religious refugees” suffering from “persecution” that included being “kicked out” of Ohio and being subject to an “extermination order” in Missouri. Reflecting this history better is important, in Murray’s view, because the legacy of Mormon religious persecution “casts a shadow on every policy” created by the Utah state government and continues to affect “their interaction with the federal government.”Footnote 45

Similar critiques emerged when the experts reviewed the profiles’ descriptions of state-level politics. In the case of Idaho, for example, while Boise State University political scientist Jaclyn Kettler found the profile generally factually “accurate” in capturing Idaho’s political history, the information was presented at the “surface level” and was “missing some of the … context or the explanation beyond a timeline,” particularly regarding why it ought to be considered a “red state.”Footnote 46 Speaking to the Ohio profile, Miami University of Ohio professor of political science John Forren said that the politics of the state were not accurately represented, even if one takes into account the September 2021 knowledge cutoff of ChatGPT4. In particular, the state is labelled a swing state three times (one in terms of historic elections, and twice in the present tense) in the profile, which “leaves a misimpression” because “recent elections don’t suggest that it is.”Footnote 47 Likewise, the labelling of Virginia as a “purple state or swing state” is not quite correct and ignores the role of “racial politics and the suburban-versus-rural divide,” so a reader is “not gonna [sic] get a good sense of what’s going on here,” Meagher said.Footnote 48 Finally, speaking to North Carolina, Cooper noted that the profile “really missed the boat” on state-level officials, because the profile “doesn’t talk at all about the leaders who have the real power,” such as president pro tempore of the North Carolina Senate Phil Burger and speaker of the North Carolina House of Representatives Tim Moore, who control matters “in terms of key political issues.”Footnote 49

Although most of the project scholars were unimpressed with ChatGPT’s output, on occasion there were positive comments made about the profiles, with Vermont being the best example. Despite having some outdated information because of ChatGPT4’s knowledge cutoff of September 2021, and despite identifying some areas where the profile could be more specific, Middlebury College political scientist Bert Johnson said that the profile provided a “pretty good description” of the politics of Vermont.Footnote 50 However, as the foregoing discussion makes clear, to the extent that the Vermont profile provides sufficient and accurate information about the state, it is quite clearly the exception.

The scholar interviews suggested that ChatGPT was far better at making accurate claims about national-level political phenomena than at providing high-quality state-level information. The profile of Massachusetts, for instance, did a “really good job capturing the national level,” but depth was missing at the state level, according to professor of political science Samantha Pettey of Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts, as, although the state certainly is heavily Democratic, and has voted Democratic at the presidential level in recent decades, it does occasionally have a “flare of … statewide Republicans” gaining office. As such, while the state is “very, very strongly blue,” as the ChatGPT profile suggested, the nationalized focus of the profile “almost doesn’t leave room for that nuance.”Footnote 51 Similarly, in the case of North Carolina, the profile mentions “voter ID, gerrymandering, healthcare, Medicaid expansion, [and] education,” which Western Carolina University professor Chris Cooper notes is “not a terrible rundown of key political issues.” However, he also described the list of issues as “generic” and added, “I would say the same key political issues would apply to most states.”Footnote 52

Although the scholars were not asked about the nationalization of state politics and were not otherwise prompted to consider the issue, fifteen out of nineteen made comments during the interviews that spoke to a nationalization bias as being present within the state-level profiles. Representative examples of these comments are highlighted in the right-hand column of Table 1. As the research team parsed the expert commentary, three main themes emerged from interviews with the state-level experts that allow us to gain some purchase on understanding the bias toward nationalization in the ChatGPT profiles: the prevalence of claims of congruent policy behaviour between national and state co-partisans, even when voters within the state hold more nuanced positions; the effect of larger states in controlling the information available regarding subnational US politics; and the decline of state and local news media.

Partisan congruence

Across multiple interviews, the experts indicated that national-level phenomena have “trickled down” to dominate state politics, but that this process is often more complex than might first be assumed.Footnote 53 In many cases, the incorporation of national-level issues at the state level is a consequence of partisanship and the presence of co-partisans at the state level of government whose party loyalty drives their policy positions toward those of their national party peers. For instance, some scholars noted that nationalized political coverage was linked to state-level political divisions around “big-ticket … wedge issues” such as transgender rights, reproductive rights, immigration, and critical race theory.Footnote 54 While many of the ChatGPT profiles suggested that congruent partisanship at the national and state levels explained state-level politics, expert Robynn Kuhlmann of the University of Central Missouri cautioned that it is important not to conflate the activities of co-partisans within the state legislatures as reflecting the popular sentiment within their own states. On the issue of reproductive rights, for example, Kuhlmann advised that the activities of the Republican-dominated Missouri state legislature – while consistent with national Republicans’ attitudes – “don’t necessarily … reflect the opinion of the people who live here,” because if one looks “at some of the polls, it seems like there’s a policy incongruence.”Footnote 55 Indeed, multiple expert interviews touched on the manner in which nationalization has shaped the tenor of state Republican parties, although not always in the same direction as the national Republican Party. The experts pointed to a key “divide between the pro-Trump voters and the anti-Trump voters” within their states, noting further that the anti-Trump voters tended to be “establishment Republicans who tend to be more moderate”; these trends were identified by experts in states as diverse as California, South Dakota and Ohio.Footnote 56

Utah offers an example of a state in which Republican co-partisans have tended to promote somewhat different policy positions than their national counterparts. The particularistic history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the legacy of Mormon persecution that drove the state’s development sometimes lead to a dissident political mind-set among Republican partisans at the state level that often differs from national trends. An illustrative example highlighted by Weber State University political scientist Leah Murray was a resolution passed in the wake of the 7 October 2023 attack on Israel by Hamas. Given Republican state legislative dominance, it would have been possible to pass a resolution that focussed solely on supporting Israel. However, the Republican majority took pains to ensure that the state Democratic Party was able to support the resolution, and in the end this led to a resolution that was “pro Israel, pro Palestinian people, pro Muslim,” which emerged from the legislature because “they had a very good conversation around: ‘what are the voices that we want to make sure we don’t leave out when we have this resolution?’”Footnote 57

The impact of large states

Another dimension of nationalization that was highlighted by the project experts is the ability of certain larger states, in particular Texas, California, and New York, to themselves shape national politics. Speaking to the partisan roles of Texas and California as the largest Republican and Democratic states respectively, Calvin Jillson of the Southern Methodist University noted that “whenever there’s a Democrat administration in Washington, Texas leads the resistance to that administration. Whenever there’s … a Republican administration in Washington [DC], California, which is the largest blue or Democrat State, leads the resistance to that Republican administration.”Footnote 58 On the other hand, Jeffrey Cummins of Fresno State commented that as the US’s largest state, “California is often looked to as kind of the image of what the rest of the country is going to look like. So a lot of things that happen here end up being reflected nationally as well.”Footnote 59 At the same time, one potential consequence of the outsize influence of large states is the potential they have to influence smaller states that are in close proximity. Political scientist David Damore of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas commented that California’s proximity influences Nevada politics, noting “a California influence that plays in our politics, and in our policy here, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse.” This influence, Damore notes, means that Nevada has a “love–hate relationship with California.”Footnote 60 On the East Coast, meanwhile, Wendy Martinek of Binghamton University, part of the State University of New York system, pointed to the “policy diffusion” role of New York among Democratic-leaning states, where it is “often seen as sort of a leader or innovator.”Footnote 61

This outsized policy influence of large states has led in part to efforts by think tanks and interest groups to promote so-called “model legislation” to smaller states that may lack the capacity of their larger neighbours. Such legislation is typically drafted by an interested third party and then offered to state legislators across the country, in an effort by these groups to secure their preferred policy positions – generally by relying on partisanship to carry them through the state legislative process. As Christopher A. Cooper notes while discussing North Carolina, “you can imagine a mad-libs [where you] just fill in the blanks,” rather than taking any state-level differences into account.Footnote 62 A slightly more nuanced version of this process, meanwhile, was described in Utah, which is “vulnerable to those model bills … and national noise, because [members of the state legislature are paid a modest] … per-diem,”Footnote 63 and do not have the capacity or the staff to “write a bill,” although the introduction of such bills sometimes leads to a “conversation” that “tends to moderate” these initial proposals.Footnote 64 Nevertheless, the point here is that the legislative process within the states has nationalized, as well, in large part because of the role that large states and interest groups now play in shaping legislative outcomes.

Declining state and local news media

Reflecting the work of Medill Local News Initiative discussed above, the project scholars also highlighted a decline in media coverage at the state and local levels as a contributing factor to nationalized coverage of their respective states, despite the existence of some counterexamples. For example, Western Carolina University scholar Christopher A. Cooper notes that “state house journalists are declining across the country, and we’re no exception,” although thankfully the state still has “a good cadre of state house journalists. And we also have the traditional outlets like the News and Observer, which is the paper of record in the state. And then we also have some upstarts, such as The Assembly.”Footnote 65

More stark, when discussing Florida, Kevin Fahey of the University of Nottingham stated, “Local news is dying, and local issues are not receiving attention as a result.”Footnote 66 The consequence, according to Fahey, is that even when state-level issues reflect national trends, it becomes impossible to gain any purchase on the more local impacts. Using the example of political polarization, Fahey responded to the ChatGPT profile with mock surprise: “Wow! Politics are more polarised!” he exclaimed. “But,” he went on, “that doesn’t tell you if politics are more polarized or less polarized in Florida than elsewhere, it doesn’t tell you on which issues, doesn’t even tell you if voters are becoming more polarized, or if it’s just elites becoming more polarized.”Footnote 67

Finally, squaring the circle between the decline in media coverage and the vacuum being filled with nationally focussed content, the University of South Dakota’s Michael Card, when asked whether the concerns of voters in South Dakota were reflected in the media coverage of South Dakota, stated, “They are reflected in the media coverage” because “national issues increasingly have become issues talked about in the politics of the state, [including] issues of minority rights such as LGBTQ individuals.”Footnote 68

Analysis: generative AI and the inevitability of national bias

As the project interviews demonstrate, ChatGPT’s responses to state-level prompts are biased toward US national politics. Two factors are likely responsible for this bias, each of which is explained below. The first is the lack of state and local news sources to use to train AI; without substantial state-level information available for training it is far less likely that AI can identify relevant differences between and among US subnational political units. The second is the recursive nature of AI-generated content. Because generative AI often “learns” from material that was itself generated by AI, there is significant likelihood that factual errors or biases – including toward national-level rather than state- or local-level information – will be compounded over time. As a 2022 study that investigated the ways in which political biases interact with AI algorithms explains, once political biases are embedded in algorithms and AI they are “harder to detect and eradicate.”Footnote 69 This is at least in part because the next iteration of AI-generated responses will incorporate previous outputs into its new responses. To put it bluntly, as the title of a July 2024 article in Nature declares, “AI Models Collapse When Trained on Recursively Generated Data.”Footnote 70

Lack of state-level information

When asked, for the purposes of this analysis, whether it was trained on state or local news sources, ChatGPT responded,

My training involved a broad range of publicly available information, which likely included some content from state and local news sources, as long as it was publicly accessible and met the quality and safety standards set during the training process. This might include news articles, blog posts, and other regional reporting that was available on public websites or through licensed datasets. However, my training data was not specifically focused on collecting information from state or local news sources alone. Instead, it aimed to gather a wide variety of information from many different kinds of sources to provide a balanced and general understanding of language and knowledge. As a result, while I may have some knowledge derived from state or local news reporting, my responses are more likely to reflect general patterns and insights from a diverse array of information sources rather than specific local or state-focused news coverage.Footnote 71

This response highlights two separate, but related, conditions that are expected to promote responses biassed to the national level. The first and most straightforward condition is that ChatGPT is trained to “reflect general patterns and insights … rather than specific local or state-focussed news coverage.” The second condition is that to the extent that ChatGPT incorporates state or local news, its doing so depends on such news being “publicly available.” As noted previously, however, state and, especially, local news outlets are diminishing rapidly, which reduces the possibility of incorporating local news into the large-language models that are used to train these generative content producers.Footnote 72 Moreover, like many news consumers, generative AI cannot access paywalled content. What AI algorithms can read is what is left behind: the often inferior, publicly available information. As a recent article in The Atlantic (itself ironically and frustratingly paywalled) explained, “The problem is not just that professionally produced news is behind a wall; the problem is that paywalls increase the proportion of free and easily available stories that are actually filled with misinformation and disinformation.”Footnote 73 In short, politically focussed generative AI content has nationalized in large part because the large-language models used to train these algorithms are biassed toward more general – and thus almost certainly more national – content and because to the extent that localized content is available for training, it is likely less thorough and less accurate.

Notably, several experts also pointed to the lack of scholarly focus on states to explain the national emphasis rampant throughout the state profiles. Among others, Leah Murray (Utah) and Jaclyn Kettler (Idaho) both noted the tendency for academia to focus on national politics and a few large states, to the detriment of public learning about smaller states. Murray, for example, noted that “flyover states” and rural areas “don’t get a lot of love” mainly because, as she put it, “political science likes urban–coastal.”Footnote 74 Concerningly, however, such a focus likely leaves a dearth of understanding not only about state politics, but also about rural politics, which was highlighted in interviews on Iowa, Minnesota, Nevada, Florida, North Carolina, and New Hampshire.Footnote 75 As University of New Hampshire’s Dante Scala noted,

typically, we talk about the United States in terms of rural America versus urban America. But it’s interesting. If you look more closely at rural America … [it] is made up of different parts that differ from each other to some degree. And New Hampshire is a good example of that [because it is] typically … chalked up … as a rural state, [which is] shorthand for … rural equals Republican. But New Hampshire … doesn’t fit that description very well.Footnote 76

Explaining how the career structure in academia incentivizes a focus on the national picture, Southern Methodist’s Calvin Jillson explains that

the great national universities are focussed on research and focussed on research at the national level: the Congress, the Presidency elections, those kinds of issues, those are where the laurels are, where the glory is. And there’s much less concentration on things like federalism or state and local government and politics.

Moreover, Jillson notes, faculty members’ “research reputations are national,” which causes a bias in favour of research that explores national trends and issues.Footnote 77

Deficits in scholarship on subnational US politics are likely to exacerbate the problem of nationalized AI-generated content about politics in states and localities. Just as is true with paywalled journalism, much of the academic research that does exist – whether it explores the states, the national government, or both the state and federal levels – can only be accessed via paywalled journals. As ChatGPT and other generative AI algorithms have less access to both high-quality journalism and scholarship, there are consequences for these algorithms’ development, training, and outputs.

AI’s recursive training

The second reason why generative AI is expected to produce more nationalized content is the fact that generative AI algorithms “learn” from themselves and from other AI-generated content. This has a baking-in effect; having noted above that local newspapers over-rely on national wire services to provide content, the iterative and recursive nature of generative AI “learning” creates a situation in which the information used to train generative AI algorithms likewise over-relies on national content. As Shumailov et al. explain in their piece on AI model collapse, while initial AI algorithms were trained on human-generated content, future training is likely to include substantial information generated by the algorithms themselves. This “degrades” the quality of the models over time.Footnote 78 In theory, the possibility exists for state and local content to be wholly absent from future generative responses to AI prompts seeking information about subnational US political units.

Conclusion: The anti-Madisonian problem of nationalized content

This study is the first to raise the problem of nationalization bias in the context of politically focussed AI-generated content. As the results presented here have demonstrated, generative AI is not able to provide meaningful or distinct information about subnational US politics. Furthermore, US national elections are conducted by the states and, as such, there are potential consequences, as well, for election administration, candidate recruitment, and voter turnout. There are also real risks that, in the future, generative AI’s nationalization bias will cause scholars and practitioners to misunderstand these aspects of American elections. Alarmingly, the quality of political information that AI provides is likely to get poorer over time, even as the technology’s ability to present that information in realistic ways will continue to improve.

The experts interviewed as part of the 50 States or Bust! Project found that the ChatGPT-generated profiles better described national-level phenomena than they explained what goes on at the state level. This reinforces findings published elsewhere that ChatGPT is of limited utility for helping people to learn about state-level politics and government.Footnote 79 While it is undoubtedly beneficial for those in the US (and elsewhere) to understand US national politics, the complaint among many of the scholar-participants in the 50 States or Bust! Project is that the general trend toward a national-level focus by citizens, politicians, and the media comes at the expense of these same groups’ engagement with, and understanding of, state-, territory- and local-level politics and policy. When partisanship is added to the mix, state and local distinctions may cease to become a focus of political discourse.

This is a particularly worrisome possibility. Nationalization, and the consequent diminishment of state and local politics, upends the principles of federalism upon which the US system of government is based. In Federalist Paper #51, James Madison explains the safeguards that a federal system provides to the rights of the people, writing,

In the compound republic of America, the power surrendered by the people is first divided between two distinct governments, and then the portion allotted to each subdivided among distinct and separate departments. Hence a double security arises to the rights of the people. The different governments will control each other, at the same time that each will be controlled by itself.Footnote 80

The nationalization of US politics, which both contributes to the difficulty generative AI has of producing meaningful subnational political information and is exacerbated by the same, reduces the distinctions between the two levels of the “compound republic” that Madison and the other framers created. It is beyond the scope of this study to consider whether there might be benefits from the more unitary system that results from the trend toward nationalization; what is clear is that this is not the system the framers intended, and that as generative AI increases in prevalence, the separation between the national and state levels of government will become even less distinct.

Dr. Lauren C. Bell is James L. Miller Professor of Political Science at Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Virginia. Her research focusses on American institutions, especially Congress and the federal courts. Her latest book, Transatlantic Majoritarianism: How Migration, Murder, and Modernity Transformed Nineteenth-Century Legislatures, is forthcoming from Clemson University Press.

Dr. Peter Finn is Senior Lecturer in Politics at Kingston University, London. His research broadly focusses on democracy and national security. His work has appeared in Political Studies Review, Critical Military Studies, and Critical Studies on Terrorism. His coedited volume, The Official Record: Oversight, National Security and Democracy, was published by Manchester University Press in 2024.

Dr. Caroline V. Leicht is Tutor in Media, Culture, and Society at the University of Glasgow, where her research focusses on gender, media, and politics. A former journalist, she is a regular media commentator and has published in Politics, the European Journal of Politics and Gender, and Political Studies Review.

Dr. Amy Tatum is Lecturer in Communication and Media at Bournemouth University. Her work focusses on gender, leadership, and politics, and has been featured in Political Studies Review, the Journal of Psychosocial Studies, the International Feminist Journal of Politics, and Cultural Sociology.