Management Implications

Land managers, homeowners, farmers, municipalities, and other resource professionals need reliable tools to efficiently manage Pyrus calleryana (Callery pear). No herbicide manufacturers have specifically included P. calleryana in labeling. While the stem treatments in this study are well established for woody species, there are few comparative efficacy studies that managers and applicators can refer to for P. calleryana management. Ongoing development of effective management strategies is imperative, as the species continues to spread and ecological costs of invasion and economic costs of invasive species removal continue to rise. Results indicate that cut stump applications of glyphosate, imazapyr, and triclopyr yielded the most consistent and greatest efficacy, closely followed by hack-and-squirt applications of triclopyr and glyphosate. Hack-and-squirt application of imazapyr and soil application of hexazinone resulted in less consistent control, with approximately 20% to 25% probability of mortality, respectively. Although cut stump applications can be labor-intensive, thorny spur shoots on P. calleryana can limit access to the trunk and pose risk to applicators when using the hack-and-squirt technique, as well as posing a risk to tractor tires and other equipment, which limits mechanical control. All of these control methods leave land managers with standing dead or felled trees to deal with. These data contribute to existing recommendations of P. calleryana management and support the ongoing development of robust integrated pest management strategies to ultimately provide a greater number of efficient and applicable treatment options for land managers.

Introduction

Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana Decne.) was first introduced to the United States more than a century ago from China to provide fire-blight resistance in European pear (Pyrus communis L.) (Creech Reference Creech1973; Culley and Hardiman Reference Culley and Hardiman2007; Cunningham Reference Cunningham1984). After escaping cultivation, naturalized populations of P. calleryana were first documented in eastern Arkansas in 1964 (Vincent Reference Vincent2005), shortly after the first commercial cultivar (i.e., ‘Bradford’) was available. Many additional cultivars have been released since then, selected for desirable characteristics such as growth form and tolerance of a wide range of environmental conditions and widely planted in urban areas. While self-crosses and within-cultivar crosses are not compatible, crosses between cultivars are, making areas with a diversity of cultivars within crossing distance a source of viable seed. Culley and Hardiman (Reference Culley and Hardiman2007) provide an excellent review of this and many other issues that have contributed to P. calleryana’s success as a woody invasive. Pyrus calleryana is now widely distributed throughout the eastern half of North America, is expanding into several western states and Canadian provinces (Culley Reference Culley2017; Culley and Hardiman Reference Culley and Hardiman2007; EDDMapS 2024; iNaturalist 2024; Swearingen et al. Reference Swearingen, Slattery, Reshetiloff and Zwicker2014; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, MacGrath, Folley, Buck and Carpenter1996; Vincent Reference Vincent2005), and is considered a legally noxious weed in Pennsylvania, Ohio, South Carolina, and Minnesota (Bradley Reference Bradley2021; Clemson University 2025; Commonwealth of Pennsylvania 2025; Minnesota Department of Agriculture 2025; Ohio Department of Natural Resources 2023).

Pyrus calleryana has several characteristics that make it highly invasive and difficult to manage. As such, concern has grown among landowners and land managers as P. calleryana has proven to be a troubling woody invasive in fields, roadsides, edge habitats, natural areas, and forest understories (Coyle et al. Reference Coyle, Williams and Hagan2021; Swearingen et al. Reference Swearingen, Slattery, Reshetiloff and Zwicker2014; Woods et al. Reference Woods, Dietsch and McEwan2022). Pyrus calleryana can interfere with forest regeneration (Clabo and Clatterbuck Reference Clabo and Clatterbuck2020) and reforestation (Sundell et al. Reference Sundell, Thomas, Amason, Stuckey and Logan1999; EMP and DRC, personal observation), and its large, thorny spur shoots present a hazard to people, pets, livestock, and equipment (Coyle et al. Reference Coyle, Williams and Hagan2021). Few herbivores feed on this species (Clem and Held Reference Clem and Held2015; Hartshorn et al. Reference Hartshorn, Palmer and Coyle2022), and the fruits are readily dispersed by wildlife (Clark Reference Clark2022; Reichard et al. Reference Reichard, Chalker-Scott, Buchanan, Marzluff, Bowman and Donnelly2001). Additionally, the species and resulting leaf litter can alter soil ecology and nutrient cycling (Woods et al. Reference Woods, Attea and McEwan2021), which can aid in the species’ ecological dominance in natural areas. Pyrus calleryana possesses high genetic diversity, suggesting high evolutionary potential in the invaded range (Sapkota et al. Reference Sapkota, Boggess, Trigiano, Klingeman, Hadziabdic, Coyle, Olukolu, Kuster and Nowicki2021, Reference Sapkota, Boggess, Trigiano, Klingeman, Hadziabdic, Coyle and Nowicki2022); thus, its range is likely to continue to spread, threatening natural ecosystems (Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Brooks, Lakoba, Sharma, Heminger, Dickinson and Barney2019) and potentially increasing costs (Pimentel et al. Reference Pimentel, Zuniga and Morrison2005; Pyšek et al. Reference Pyšek, Jarošík, Hulme, Pergl, Hejda, Schaffner and Vilà2012) for land management, restoration efforts, and production forestry.

Despite the highly invasive nature of P. calleryana, few published management and control recommendations exist. Cutting down P. calleryana trees without treatment results in vigorous resprouting (Maloney et al. Reference Maloney, Borth, Dietsch, Lloyd and McEwan2023). Prescribed fire, while a commonly used management tactic for unwanted vegetation, will top-kill the plant; however, P. calleryana’s vigorous resprouting makes this strategy ineffective in isolation (Maloney et al. Reference Maloney, Borth, Dietsch, Lloyd and McEwan2023; Warrix and Marshall Reference Warrix and Marshall2018). Recommendations frequently suggest foliar sprays, basal bark sprays, cut stump applications, and/or hack-and-squirt or frill applications depending primarily on the size of the target trees (Elmore Reference Elmore2019; Maloney et al. Reference Maloney, Borth, Dietsch, Lloyd and McEwan2023; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Manning and Enloe2010; Quick Reference Quick2021; Templeton et al. Reference Templeton, Gover, Jackson and Wurzbacher2020; Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Coyle, Jenkins, Barnes, Crowe, Horn, Bates and Roesch2020). However, few empirical data exist regarding management options by tree size for P. calleryana. Our objective was to build upon current knowledge surrounding P. calleryana chemical control strategies by examining the efficacy of seven herbicide treatments utilizing four commonly used active ingredients against a wide variety of midstory P. calleryana in several different habitat types.

Materials and Methods

In spring of 2021, six sites invaded by P. calleryana were identified in Georgia (two sites), Kansas (three sites), and South Carolina (one site) (Table 1). Five blocks, each consisting of eight individual P. calleryana with a diameter at breast height (dbh) ≥5 cm, were established at each of the sites. Study trees were at least 10 m apart to reduce the chances of intraspecific root grafting. After spring leaf-out (April and May), crown fullness (using a visual estimate of green foliage present, 0% to 100%), and dbh were measured before treatment applications. All P. calleryana ranged from 5- to 36-cm dbh and appeared healthy. One tree per block was randomly assigned to each herbicide treatment, which included three cut stump applications, three hack-and-squirt applications, a soil application (Table 2), and a non-treated control. To ensure consistent application of herbicides, trees that received cut stump treatments were cut 10 to 15 cm from the ground with a chainsaw or heavy-duty folding saw. All herbicides used with the cut stump application were sprayed to thoroughly wet the cambium of all stems until the point of runoff immediately following cutting. Glyphosate (478.73 g L−1), triclopyr (343.90 g L−1), and imazapyr (22.47 g L−1) were applied to cut stumps. Hack-and-squirt treatments were administered with a heavy machete by making downward-angled evenly spaced cuts through the bark and into the cambium approximately 2.5 cm apart around the stem at breast height for glyphosate and imazapyr or slightly overlapping for triclopyr. Herbicide was then immediately sprayed into the cuts. Glyphosate (478.73 g L−1) and triclopyr (343.90 g L−1) were applied using 1 ml per 5.0 cm dbh and 0.5 ml in each cut, respectively. Imazapyr (22.47 g L−1) was applied at 1 ml per cut. We were interested in efficacy of the dilute solution for imazapyr application (22.47 g L−1) over the concentrate solution (159.77 g L−1) given the large difference between them. For the soil treatment, hexazinone (287.58 g ai L−1) was applied within 0.9 m of the stem or root collar using an exact-delivery handgun applicator (Simcro Velpar® L VU Spotgun Applicator, https://www.cckoutfitters.com/products/datamars-syringe-simcro-velpar-applicator-15ml-spray-nozzle-large-draw-off-cap) or a syringe. All other herbicides were applied using a handheld plastic sprayer with a spray trigger at low pressure.

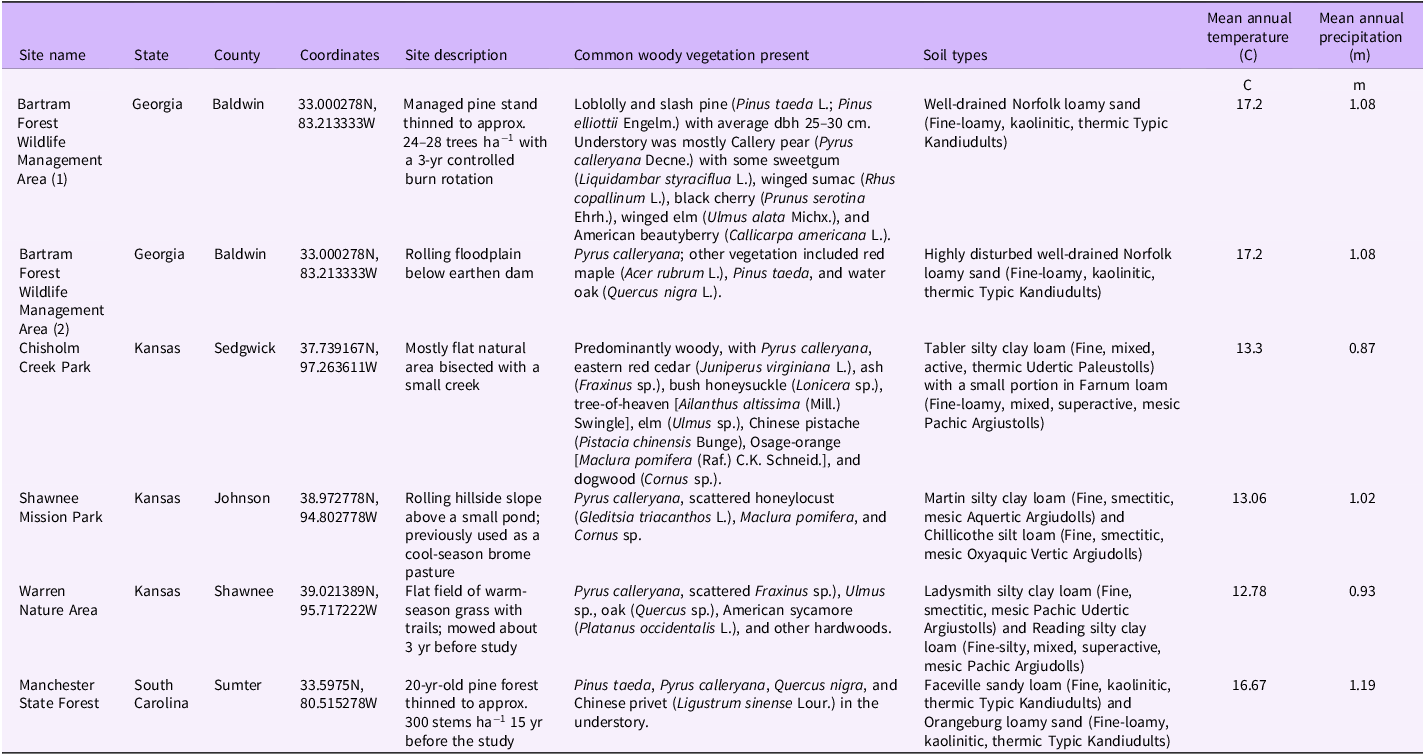

Table 1. Site descriptions for a midstory Pyrus calleryana management study a .

a Climate data for county-level mean annual temperature and precipitation were obtained from National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, National Centers for Environmental Information (2023), and soil types were obtained from U.S. Department of Agriculture–Natural Resources Conservation Service (2020).

Table 2. Trade names, active ingredients, and treatment application methods used to evaluate Pyrus calleryana control at sites in Georgia, Kansas, and South Carolina, USA.

a Grams active ingredient L−1.

Data from nearby weather stations were used to estimate rainfall at sites in the 7 d before and 14 d after treatment (CoCoRaHS 2023; Georgia Forestry Commission Automated Weather Data 2024; Kansas Mesonet Reference Mesonet2021). These data were of particular interest, because hexazinone labels recommend applying product when soil is moist.

Following herbicide applications, the condition of each tree was assessed periodically, including an estimate of crown fullness and an assessment of mortality. Crown fullness was a visual estimate of expected live foliage based on branching minus dead foliage present, expressed as percent crown remaining. Two observations were made from two locations at a 90º angle and averaged. In addition, trees were considered alive if any green or subapical sprouting was present or if new growth was evident, and dead trees were confirmed with easily snapped twigs and scraping the bark to confirm brown, dead cambium where the bole was easily accessible. Measurement occasions, shown in Table 3, varied by site.

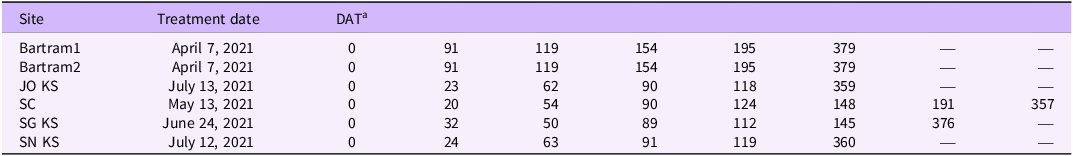

Table 3. Measurement occasions for Pyrus calleryana assessments following herbicide treatments at six sites in Georgia, Kansas, and South Carolina, USA.

a DAT, days after treatment.

The experimental design was a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with repeated measures over time, replicated across six sites. As such, the design across all sites can be considered an RCBD with two blocking factors: site and block within site. Data were analyzed separately at two temporal endpoints: approximately 17 wk after treatment (17 WAT, corresponding to days 119, 119, 118, 124, 112, and 119 for sites Bartram1, Bartram2, JO KS, SC, SG KS, and SN KS, respectively) and at approximately 1 yr after treatment (1 YAT, corresponding to days 379, 379, 359, 377, 376, and 360 for sites Bartram1, Bartram2, JO KS, SC, SG KS, and SN KS respectively).

At each endpoint, crown percentage (crown%) was analyzed using linear mixed-effects models with a specification reflecting the experimental design. In particular, the models included fixed effects of site and treatment, as well as random block-within-site effects. Because there was considerable variability in stem size among the trees used in this study, the model also included dbh and an interaction between treatment and dbh to consider the possibility of stem size–dependent treatment effectiveness. Assumptions of the model were standard; random effects for blocks and errors were assumed mutually independent with separate variance components. Models were fit with restricted maximum likelihood, and Kenward-Roger approximate F- and t-tests were used for inference. In the presence of a significant treatment by dbh interaction, marginal treatment means were estimated and contrasted at low, medium, and high values of dbh (specifically, at the quartiles of dbh). Contrasts included all pairwise comparisons using Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) approach to adjust for multiple comparisons.

At each endpoint, mortality was analyzed using logistic regression. However, because there were treatments with both 0% and 100% mortality, quasi-complete separation (Agresti Reference Agresti2013) was encountered when fitting the logistic model with standard maximum-likelihood estimation, causing parameter estimates to diverge to plus or minus infinity and preventing valid model-based inference. Therefore, logistic regression models were fit using penalized maximum likelihood estimation (aka Firth regression) (Firth Reference Firth1993). This approach is a widely recommended alternative to standard logistic regression that provides finite parameter estimates and valid inference under quasi-complete separation (QCS) scenarios. The specification of the model was similar to the linear mixed-effects models used for crown%. However, because random effects cannot be accommodated in Firth regression, site, block, treatment, and dbh were modeled with fixed effects. A treatment by dbh interaction was dropped when nonsignificant. From the fitted model, marginal estimates of mortality probability were estimated for each treatment or, when the treatment by dbh interaction was significant, for each treatment at the quartiles of dbh. Pairwise contrasts between the treatments were tested yielding odds ratios comparing the odds of mortality across pairs of treatments. Tukey’s HSD was used for inferences on pairwise odds ratios. Inferences from the Firth logistic regression model were based on penalized likelihood ratio statistics, which yield chi-square tests and intervals and Wald z-tests.

All analyses were performed using R (R Core Team 2025). Models were fit using the packages lme4 (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) and logistf (Heinze et al. Reference Heinze, Ploner, Jiricka and Steiner2025). Post hoc inferences and plots were produced using the lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al. Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017), emmeans (Lenth Reference Lenth2025), and ggplot2 (Wickham Reference Wickham2016) packages. All hypothesis tests were conducted at significance level alpha = 0.05, and confidence intervals were formed with a 95% confidence coefficient.

Results and Discussion

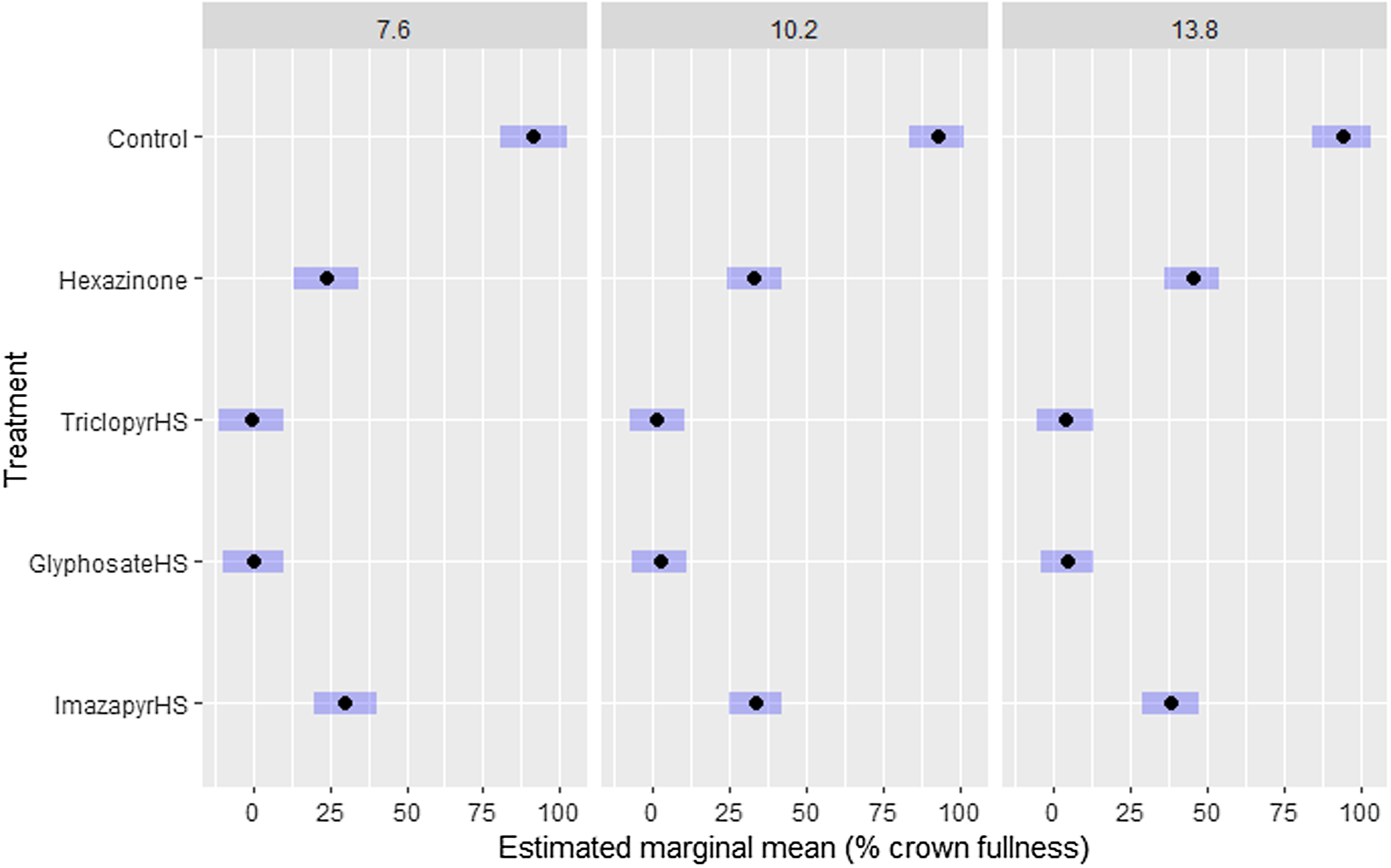

At 1 YAT, the analysis of crown% revealed a significant interaction between treatment and dbh (F(4, 133.4) = 3.26, P = 0.014), as well as a significant main effect of treatment (F(4, 131.0) = 75.19, P < 0.001), representing non-equality of mean crown% at the mean dbh. Estimated marginal treatment means at the quartiles of dbh are displayed in Figure 1. Pairwise contrasts in estimated marginal treatment means at the quartiles of dbh are shown in Table 4. At the median dbh, all pairs of treatments have significantly different marginal mean crown%, except imazapyr hack and squirt versus hexazinone soil treatment and glyphosate hack and squirt versus triclopyr hack and squirt.

Figure 1. Estimated marginal means and 95% confidence intervals for percent crown fullness of Pyrus calleryana at approximately 1 yr after application of four herbicide treatments; imazapyr, glyphosate, and triclopyr hack-and-squirt applications (appended with -HS), a hexazinone soil treatment, and a non-treated control. Means are estimated across quartiles of diameter at breast height (dbh; 7.6, 10.2, and 13.8 cm).

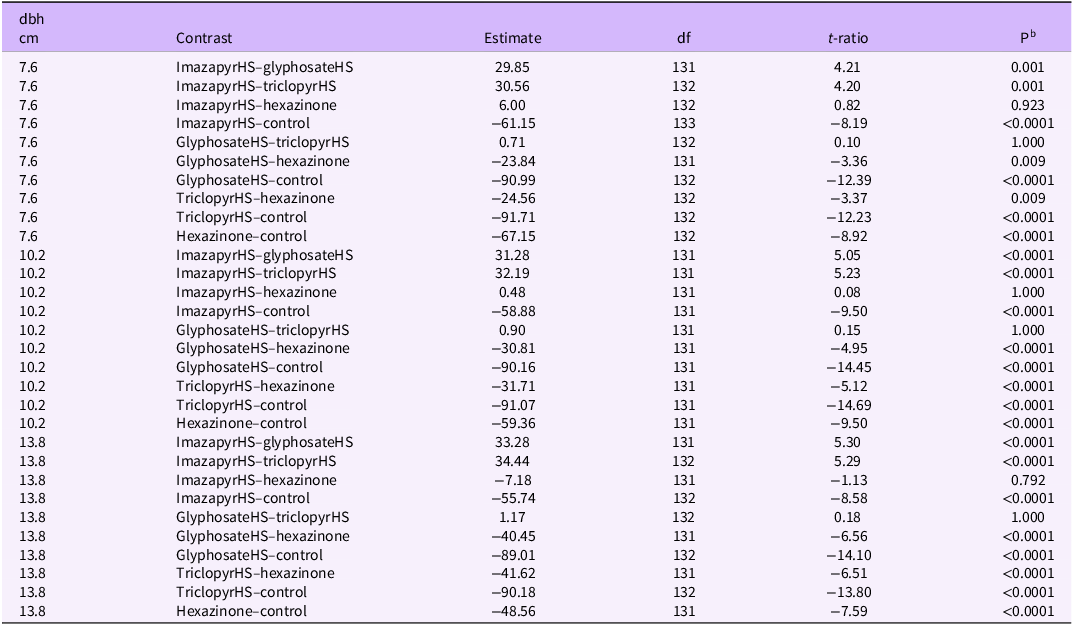

Table 4. Results for percentage crown fullness (crown%) at approximately 1 yr after treatment (1 YAT) for Pyrus calleryana following application of four herbicidal treatments plus non-treated control at sites in Georgia, Kansas, and South Carolina, USA a .

a Pairwise contrasts among estimated marginal treatment means at the quartiles of diameter at breast height (dbh).

b P-values are adjusted for multiplicity with Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) method.

Results for crown% at 17 WAT were similar: a significant interaction between treatment and dbh (F(4, 133.2) = 3.93, P = 0.005), as well as a significant main effect of treatment (F(4, 131.0) = 65.54, P < 0.001) were found. These data highlight differences in the speed of defoliation from our treatments. Estimated marginal treatment means and contrasts among those means were similar to those at 1 YAT. These results are plotted and tabulated in Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1, respectively.

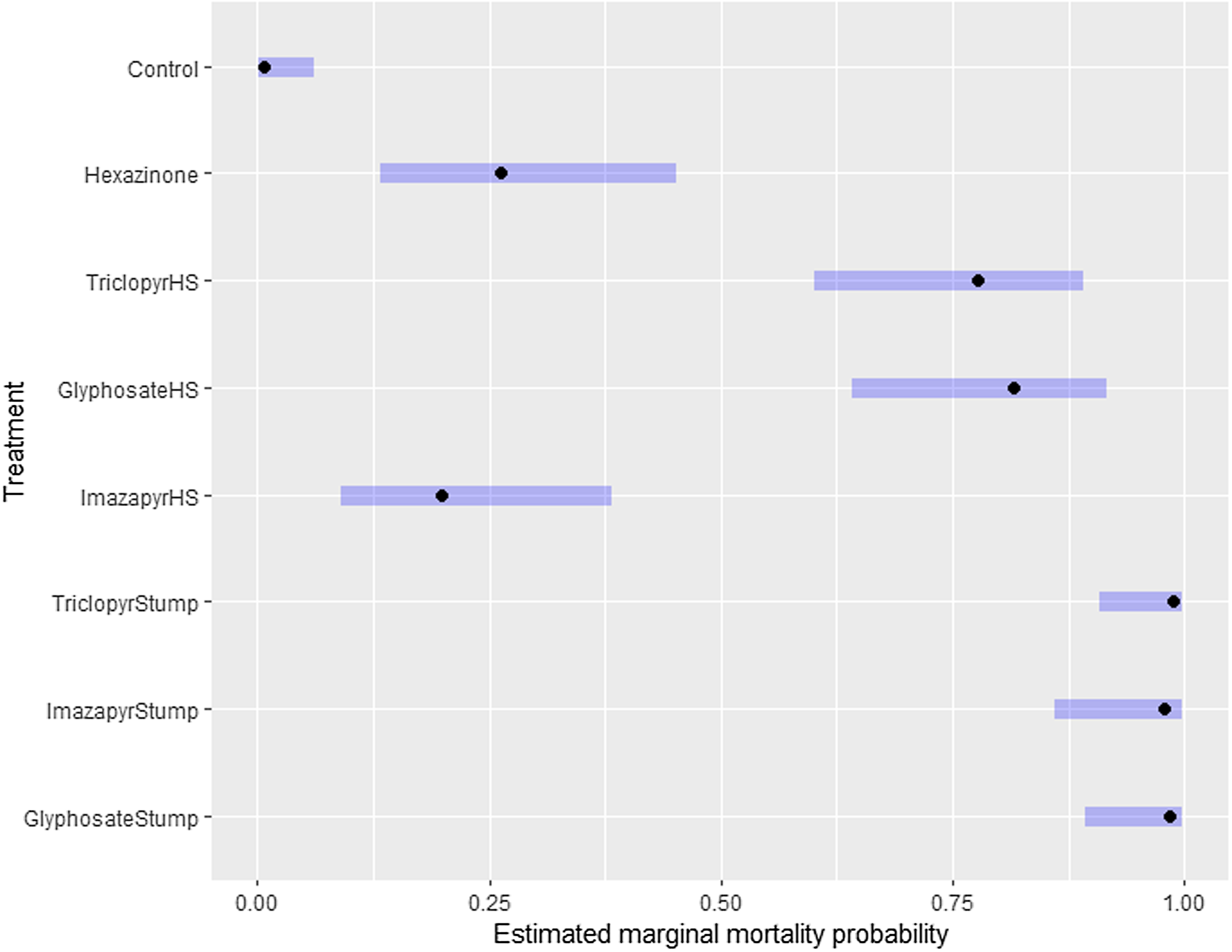

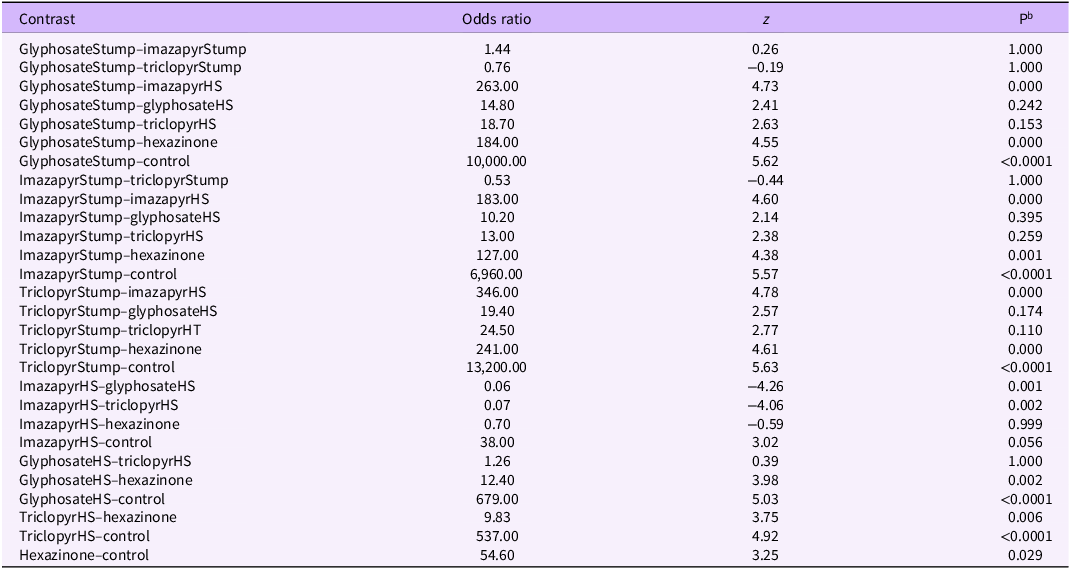

At 1 YAT, an initial model for mortality revealed a nonsignificant interaction between treatment and dbh (χ2(7) = 6.12, P = 0.526), which was dropped from the model before re-fitting. The resulting model yielded significant effects of dbh (χ2(1) = 12.44, P < 0.001) and treatment (χ2(7) = 166.81, P < 0.001). Estimated marginal mortality probabilities for each treatment are plotted in Figure 2. Pairwise odds ratios comparing the odds or mortality for each pair of treatments are tabulated in Table 5. The odds of mortality were not found to differ significantly among any of the stump treatments plus the triclopyr and glyphosate hack-and-squirt treatments, which were all quite effective. The odds of mortality were also not found to differ significantly among the imazapyr hack-and-squirt, hexazinone soil, and control treatments, which were not effective.

Figure 2. Estimated marginal means and 95% confidence intervals for probability of mortality in Pyrus calleryana at approximately 1 yr after application of seven herbicide treatments; a hexazinone soil treatment, triclopyr, glyphosate, and imazapyr hack-and-squirt applications (appended with -HS), triclopyr, imazapyr, and glyphosate cut stump applications (appended with -Stump), and a non-treated control.

Table 5. Estimated marginal mortality probabilities at approximately 1 yr after treatment (1 YAT) for Pyrus calleryana following application of four herbicidal treatments plus a non-treated control at sites in Georgia, Kansas, and South Carolina, USA a .

a Tests correspond to the null hypothesis that the odds ratio is 1.

b P-values are adjusted for multiplicity with Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) method.

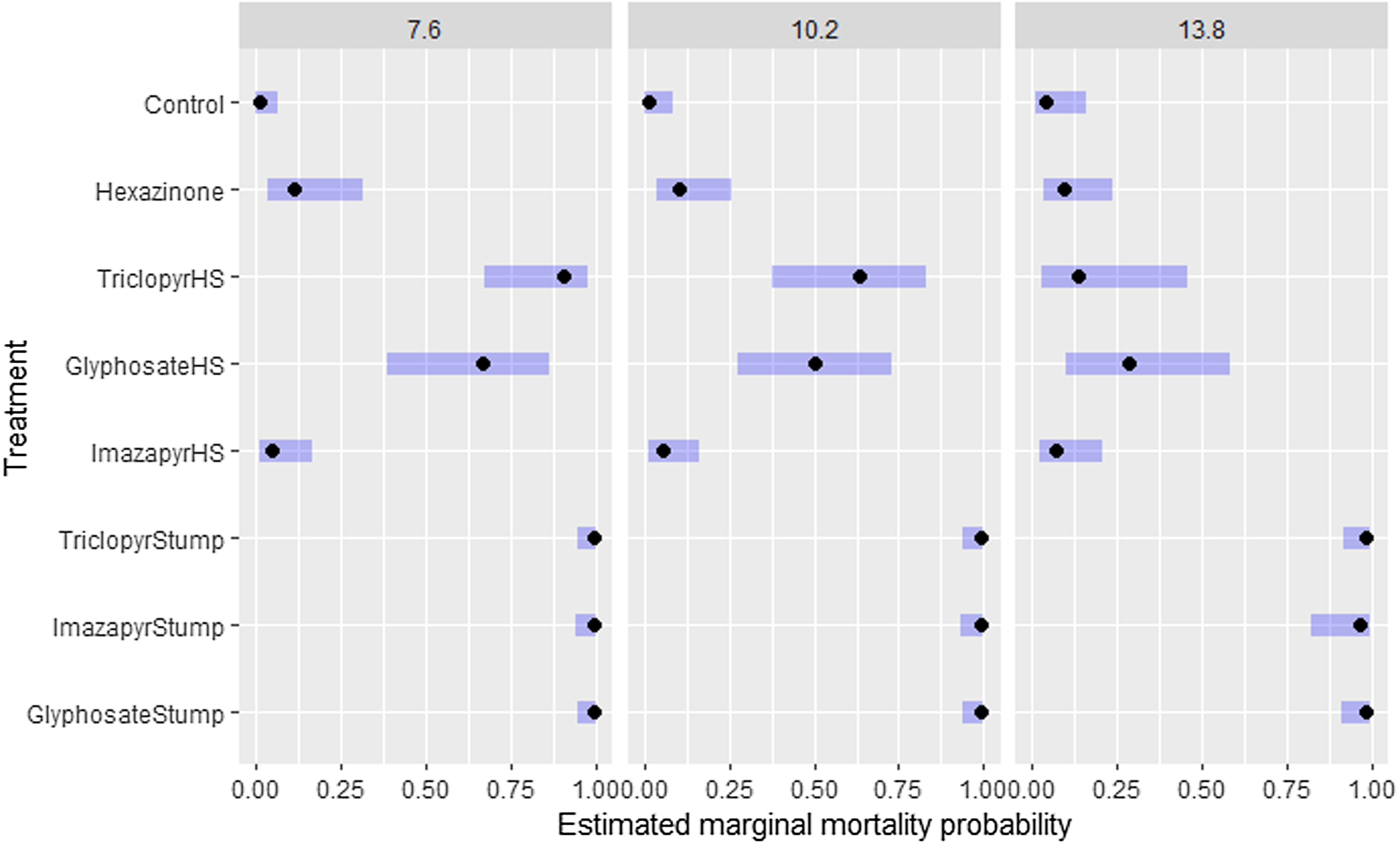

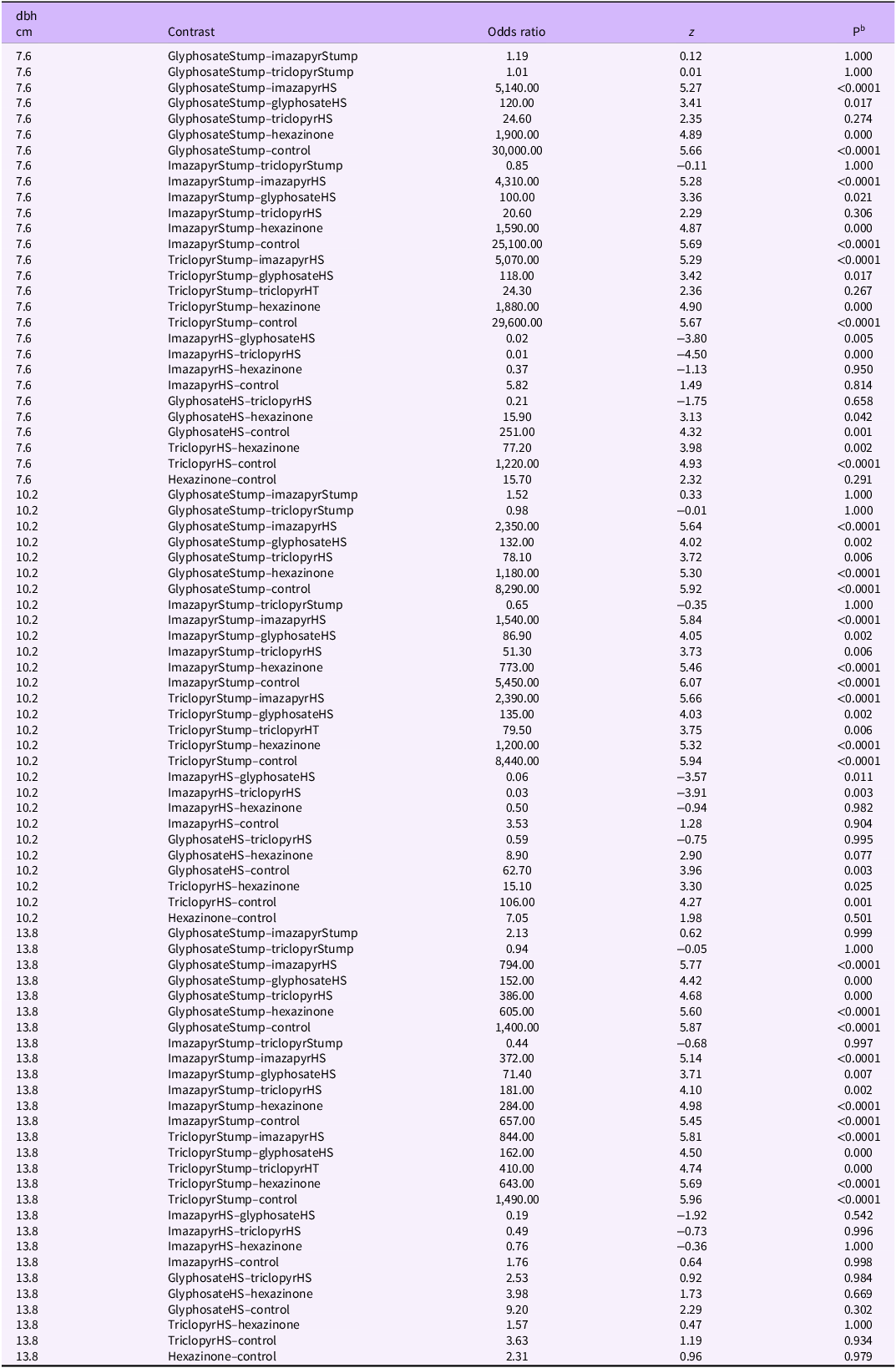

An initial model for mortality at 17 WAT revealed a significant interaction between treatment and dbh (χ2(7) = 14.21, P = 0.048), as well as a significant main effect of treatment (χ2(7) = 143.54, P < 0.001), implying non-homogeneity of mortality probability across treatments at the mean dbh. Estimated marginal mortality probabilities for each treatment are plotted at the quartiles of dbh in Figure 3. Smaller plants succumbed to hack-and-squirt treatments with glyphosate and triclopyr more quickly than larger plants at 17 WAT (Figure 3), but these treatments ultimately resulted in roughly 80% mortality at 1 YAT (Figure 2). Pairwise odds ratios comparing the odds of mortality for each pair of treatments at 17 WAT are tabulated separately at the quartiles of dbh in Table 6.

Figure 3. Estimated marginal means and 95% confidence intervals for probability of mortality in Pyrus calleryana at approximately 17 wk after application of seven herbicide treatments; a hexazinone soil treatment, triclopyr, glyphosate, and imazapyr hack-and-squirt applications (appended with -HS), triclopyr, imazapyr, and glyphosate cut stump applications (appended with -Stump), and a non-treated control. Means are estimated across quartiles of diameter at breast height (dbh; 7.6, 10.2, and 13.8 cm).

Table 6. Estimated marginal mortality probabilities at approximately 17 wk after treatment (17 WAT) for Pyrus calleryana following application of four herbicidal treatments plus a non-treated control at sites in Georgia, Kansas, and South Carolina, USA a .

a Pairwise contrasts among estimated marginal mortality probabilities for each treatment at the quartiles of diameter at breast height (dbh). Tests correspond to the null hypothesis that the odds ratio is 1.

b P-values are adjusted for multiplicity with Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) method.

At 1 YAT, cut stump treatments using glyphosate, imazapyr, and triclopyr were the most effective method for killing P. calleryana, as all trees that received these treatments did not resprout and died, regardless of active ingredient. Additional observations at Bartram1 and Bartram2 in May 2025 (approximately 4 yr posttreatment) found no signs of stump resprouts (CC and EMP, personal observation), which suggests success for long-term control. Glyphosate and triclopyr applied with the hack-and-squirt technique provided intermediate control (approximately 80% mortality), while results were comparatively poor using imazapyr hack and squirt and the soil application of hexazinone (approximately 20% and 25% mortality, respectively). Overall, our findings indicate that all tested herbicide treatments can kill P. calleryana, and the efficacy of the different treatments varies widely (20% to 100% mortality).

We experienced several hurdles with using hexazinone soil treatment. We speculate the negligible effect of hexazinone soil applications may have been a result of less than satisfactory soil moisture conditions. Rainfall estimates at sites in the 7 d before hexazinone application ranged from 2.0 to 4.7 cm, whereas the sites received approximately 0.01 to 1.8 cm of rainfall in the 2-wk period after application. Georgia and South Carolina received the least amount of rain postapplication, with 0.03 cm and 0.01 cm of rain in the 2 wk following hexazinone soil treatments, respectively. Manufacturers recommend the soil be moist at the time of application as well as during the following 2 wk, and per label recommendations, best results are seen when the soil receives approximately 0.64 to 1.27 cm of water in the 2 wk postapplication (Anonymous 2024). Yet excessive soil moisture following application may also hinder efficacy. The results from the hexazinone soil treatments were not entirely unexpected, as Vogt et al. (Reference Vogt, Coyle, Jenkins, Barnes, Crowe, Horn, Bates and Roesch2020) described similar hurdles when using hexazinone soil treatments against P. calleryana understory trees. Because there are specific moisture recommendations, soil applications of hexazinone are unlikely to generate consistent results without irrigation or optimal timing and may prove to be a challenging method to utilize when managing P. calleryana on a large scale. Additionally, there was noticeable non-target grass dieback around the base of P. calleryana treated with hexazinone soil treatments in Kansas (RA, personal observation). While the herbicide application method is attractive due to the reduced effort and speed of application, information is needed to determine whether timing of application may increase efficacy of this active ingredient.

Herbicide applications have proven to be an effective, efficient, and relatively inexpensive integrated plant management (IPM) tool (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Manning and Enloe2010; Terry Reference Terry2018) that has been widely utilized to combat many woody invasive species in North America (Pile Knapp et al. Reference Pile Knapp, Coyle, Dey, Fraser, Hutchinson, Jenkins, Kern, Knapp, Maddox, Pinchot and Wang2023). Treatments such as foliar, basal bark, and hack-and-squirt herbicide applications have been successful on P. calleryana trees (Quick Reference Quick2021; Terry Reference Terry2018; Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Coyle, Jenkins, Barnes, Crowe, Horn, Bates and Roesch2020), but the thorny spur shoots often present on P. calleryana can pose a substantial impediment to herbicide applicators. Deep incisions into the bark and cambium are needed for effective hack-and-squirt treatments, and the spur shoots, which can be several inches long, may serve as a physical risk to applicators and make the stems inaccessible or difficult to cut. Using a cut stump method can be physically demanding based on land parcel size and level of invasion and may require trimming of lower branches for access to the bole. As no cut trees showed signs of resprout after the 1-yr study period, cut stump interventions with glyphosate, imazapyr, or triclopyr appear to be promising options for long-term control of midstory individual trees, and this application method has been recommended for many other woody invasive species, such as camphortree [Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl], invasive olives (Elaeagnus umbellata Thunb.; Elaeagnus angustifolia L.), tallowtree [Triadica sebifera (L.) Small], and trifoliate orange [Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.] (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Manning and Enloe2010). Additionally, standing dead trees may not be desirable for some land managers’ objectives, so this factor along with efficacy may incentivize land managers to utilize cut stump interventions. It is important to note that any treatment method for midsized P. calleryana will leave landowners with either standing dead or downed trees to leave or dispose of, highlighting the importance of targeting P. calleryana before it is large and well established. Glyphosate and triclopyr applications resulted in faster mortality of smaller-diameter trees, which would allow further remediation (mulching, pile and burn) sooner than larger diameter trees, with less risk of sprouting. Furthermore, research on other woody species suggests cut stump treatments may be performed in a wide application window (Ballard and Nowack Reference Ballard and Nowack2006; Enloe et al. Reference Enloe, O’Sullivan, Loewenstein, Brantley and Lauer2018). Studies are needed to determine efficacy of cut stump treatments for P. calleryana during each season to potentially provide flexibility for treatment plans.

Due to the persistent and pervasive nature of P. calleryana, integrated pest management is needed to effectively target this invasive species. Herbicides are and will continue to be a critical component of IPM programs. Efforts are increasing to educate the public in hopes of reducing existing and future plantings of P. calleryana (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Ma, Snyder and Floress2019), which will help reduce the seed source on the landscape. However, nurseries and retailers are still selling Bradford pear and other P. calleryana cultivars (EMP and DRC, personal observation). Reducing and eliminating new plantings of P. calleryana is essential to a successful IPM program, especially because prior studies have found that its seeds are easily dispersed and can persist in the seedbank for many years (Serota and Culley Reference Serota and Culley2019). Warrix and Marshall (Reference Warrix and Marshall2018) have delineated the application of prescribed fire alone to fruits, seeds, and 1-yr-old seedlings in prairie ecosystems in the U.S. Midwest region. Efforts are ongoing to understand seed viability, germination rates, and potential use of prescribed fire for managing seedlings and saplings in the southeastern United States. However, even with other cultural interventions, we speculate that careful use of herbicides will still play a large role in the IPM approach for established P. calleryana (Flynn et al. Reference Flynn and Smeda2015; Warrix and Marshall Reference Warrix and Marshall2018), as seen with management of other woody invasive species like Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense Lour.) (Hanula et al. Reference Hanula, Horn and Taylor2009), invasive honeysuckles (Lonicera sp.), Chinaberry (Melia azedarach L.), and T. sebifera (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Manning and Enloe2010). Altogether, our study tested the effectiveness of seven herbicide treatments against P. calleryana in common habitats such as fields, pine stands, mixed stands, and floodplains. Although the study herein encompasses sites in the Southeast and Midwest, rather than the entire range of P. calleryana in the eastern half of the United States, we anticipate that results would be comparable in the northern extent of P. calleryana’s range. For a comprehensive IPM plan, additional research is needed to confirm long-lasting effects of these treatments in the full range of P. calleryana in the United States and to identify any potential synergistic effects when existing treatments are combined with other management strategies.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to personnel from the Georgia Forestry Commission, South Carolina Forestry Commission, and Kansas Forest Service for assistance in herbicide application and site selection. We thank the Great Plains Nature Center, Shawnee County Parks and Recreation, and Johnson County Parks and Recreation for site access in Kansas. Melissa L. Griffin with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources and Pam Knox with the University of Georgia provided weather data access. We also thank Melanie Taylor with USFS for statistical guidance. Victor Fitzgerald helped with figure formatting on an earlier draft. Finally, we thank two anonymous reviewers for comments that greatly improved the article. The findings and conclusions are solely those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/inp.2025.10027

Funding statement

Support was provided by grant 20-CS-11330160-086 from the USDA Forest Service–Southern Region to Clemson University, the Georgia Forestry Commission, the South Carolina Forestry Commission, the Kansas Forest Service, and the USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station. Trycera® and Velossa® were graciously provided by Helena Agri-Enterprises, LLC.

Competing interests

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

Disclaimer of non-endorsement

Reference herein to any specific commercial products, process, business, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes.