1 Introduction

All spaces in this article, if not said otherwise, are Tychonoff spaces and all maps are continuous. By

![]() $C(X)$

(resp.,

$C(X)$

(resp.,

![]() $C^*(X)$

), we denote the set of all continuous (resp., continuous and bounded) real-valued functions on a space X. We write

$C^*(X)$

), we denote the set of all continuous (resp., continuous and bounded) real-valued functions on a space X. We write

![]() $C_p(X)$

(resp.,

$C_p(X)$

(resp.,

![]() $C_p^*(X)$

) for the spaces

$C_p^*(X)$

) for the spaces

![]() $C(X)$

(resp.,

$C(X)$

(resp.,

![]() $C^*(X)$

) endowed with the pointwise topology. More information about the spaces

$C^*(X)$

) endowed with the pointwise topology. More information about the spaces

![]() $C_p(X)$

can be found in [Reference Tkachuk20]. By dimension, we mean the covering dimension

$C_p(X)$

can be found in [Reference Tkachuk20]. By dimension, we mean the covering dimension

![]() $\dim $

defined by finite functionally open covers (see [Reference Engelking2]). According to that definition, we have

$\dim $

defined by finite functionally open covers (see [Reference Engelking2]). According to that definition, we have

![]() $\dim X=\dim \beta X$

, where

$\dim X=\dim \beta X$

, where

![]() $\beta X$

is the Čech–Stone compactification of X.

$\beta X$

is the Čech–Stone compactification of X.

After the striking result of Pestov [Reference Pestov18] that

![]() $\dim X=\dim Y$

provided that

$\dim X=\dim Y$

provided that

![]() $C_p(X)$

and

$C_p(X)$

and

![]() $C_p(Y)$

are linearly homeomorphic, and Gul’ko’s [Reference Gul’ko7] generalization of Pestov’s theorem that the same is true for uniformly continuous homeomorphisms, a question arose whether

$C_p(Y)$

are linearly homeomorphic, and Gul’ko’s [Reference Gul’ko7] generalization of Pestov’s theorem that the same is true for uniformly continuous homeomorphisms, a question arose whether

![]() $\dim Y\leq \dim X$

if there is continuous linear surjection from

$\dim Y\leq \dim X$

if there is continuous linear surjection from

![]() $C_p(X)$

onto

$C_p(X)$

onto

![]() $C_p(Y)$

(see [Reference Arkhangel’skii, van Mill and Reed1]). This was answered negatively by Leiderman–Levin–Pestov [Reference Leiderman, Levin and Pestov14] and Leiderman–Morris–Pestov [Reference Leiderman, Morris and Pestov15]. On the other hand, it was shown in [Reference Leiderman, Levin and Pestov14] that if there is a linear continuous surjection

$C_p(Y)$

(see [Reference Arkhangel’skii, van Mill and Reed1]). This was answered negatively by Leiderman–Levin–Pestov [Reference Leiderman, Levin and Pestov14] and Leiderman–Morris–Pestov [Reference Leiderman, Morris and Pestov15]. On the other hand, it was shown in [Reference Leiderman, Levin and Pestov14] that if there is a linear continuous surjection

![]() $C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

such that X and Y are compact metrizable spaces and

$C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

such that X and Y are compact metrizable spaces and

![]() $\dim X=0$

, then

$\dim X=0$

, then

![]() $\dim Y=0$

. The last result was extended for arbitrary compact spaces by Kawamura–Leiderman [Reference Kawamura and Leiderman10] who also raised the question whether this is true for any Tychonoff spaces X and Y. In this article, we provide a positive answer to that question and discuss the situation when the surjection

$\dim Y=0$

. The last result was extended for arbitrary compact spaces by Kawamura–Leiderman [Reference Kawamura and Leiderman10] who also raised the question whether this is true for any Tychonoff spaces X and Y. In this article, we provide a positive answer to that question and discuss the situation when the surjection

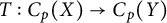

![]() $T:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

is uniformly continuous. Let us note that the preservation of dimension under linear homeomorphisms doesn’t hold for function spaces with the uniform norm topology. Indeed, according to the classical result of Milutin [Reference Milutin17] if X and Y are any uncountable metrizable compacta, then there is a linear homeomorphism between the Banach spaces

$T:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

is uniformly continuous. Let us note that the preservation of dimension under linear homeomorphisms doesn’t hold for function spaces with the uniform norm topology. Indeed, according to the classical result of Milutin [Reference Milutin17] if X and Y are any uncountable metrizable compacta, then there is a linear homeomorphism between the Banach spaces

![]() $C(X)$

and

$C(X)$

and

![]() $C(Y)$

.

$C(Y)$

.

Suppose

![]() $E_p(X)\subset C_p(X)$

and

$E_p(X)\subset C_p(X)$

and

![]() $E_p(Y)\subset C_p(Y)$

are subspaces containing the zero functions on X and Y, respectively. Recall that a map

$E_p(Y)\subset C_p(Y)$

are subspaces containing the zero functions on X and Y, respectively. Recall that a map

![]() $\varphi : E_p(X)\to E_p(Y)$

is uniformly continuous, if for every neighborhood U of the zero function in

$\varphi : E_p(X)\to E_p(Y)$

is uniformly continuous, if for every neighborhood U of the zero function in

![]() $E_p(Y),$

there is a neighborhood V of the zero function in

$E_p(Y),$

there is a neighborhood V of the zero function in

![]() $E_p(X)$

such that

$E_p(X)$

such that

![]() $f,g\in E_p(X)$

and

$f,g\in E_p(X)$

and

![]() $f-g\in V$

implies

$f-g\in V$

implies

![]() $\varphi (f)-\varphi (g)\in U$

. Evidently, if

$\varphi (f)-\varphi (g)\in U$

. Evidently, if

![]() $E_p(X)$

and

$E_p(X)$

and

![]() $E_p(Y)$

are linear spaces, then every linear continuous map between

$E_p(Y)$

are linear spaces, then every linear continuous map between

![]() $E_p(X)$

and

$E_p(X)$

and

![]() $E_p(Y)$

is uniformly continuous. If

$E_p(Y)$

is uniformly continuous. If

![]() ${f\in C_p(X)}$

is a bounded function, then

${f\in C_p(X)}$

is a bounded function, then

![]() $||f||$

stands for the supremum norm of f. The notion of c-good maps was introduced in [Reference Gorak, Krupski and Marciszewski6] (see also [Reference Gartside and Feng5]), where c is a positive number. A map

$||f||$

stands for the supremum norm of f. The notion of c-good maps was introduced in [Reference Gorak, Krupski and Marciszewski6] (see also [Reference Gartside and Feng5]), where c is a positive number. A map

![]() $\varphi : E_p(X)\to E_p(Y)$

is c-good if for every bounded function

$\varphi : E_p(X)\to E_p(Y)$

is c-good if for every bounded function

![]() $g\in E_p(Y)$

there exists a bounded function

$g\in E_p(Y)$

there exists a bounded function

![]() $f\in E_p(X)$

such that

$f\in E_p(X)$

such that

![]() $\varphi (f)=g$

and

$\varphi (f)=g$

and

![]() $||f||\leq c||g||$

.

$||f||\leq c||g||$

.

Everywhere below, by

![]() $D(X),$

we denote either

$D(X),$

we denote either

![]() $C^*(X)$

or

$C^*(X)$

or

![]() $C(X)$

. Here is one of our main results.

$C(X)$

. Here is one of our main results.

Theorem 1.1 Let

![]() $T:D_p(X)\to D_p(Y)$

be a c-good uniformly continuous surjection for some

$T:D_p(X)\to D_p(Y)$

be a c-good uniformly continuous surjection for some

![]() $c>0$

. Then ,Y is zero-dimensional provided so is X.

$c>0$

. Then ,Y is zero-dimensional provided so is X.

Corollary 1.2 Suppose there is a linear continuous surjection from

![]() $C_p^*(X)$

onto

$C_p^*(X)$

onto

![]() $C_p^*(Y)$

. Then, Y is zero-dimensional provided that so is X.

$C_p^*(Y)$

. Then, Y is zero-dimensional provided that so is X.

Corollary 1.2 follows from Theorem 1.1 because every linear continuous surjection between

![]() $C_p^*(X)$

and

$C_p^*(X)$

and

![]() $C_p^*(Y)$

is c-good for some

$C_p^*(Y)$

is c-good for some

![]() $c>0$

(see Proposition 3.3). Moreover, as one of the referees observed, it is not always possible to have a continuous linear surjection

$c>0$

(see Proposition 3.3). Moreover, as one of the referees observed, it is not always possible to have a continuous linear surjection

![]() $T:C_p^*(X)\to C_p(Y)$

with

$T:C_p^*(X)\to C_p(Y)$

with

![]() $C_p(Y)\neq C_p^*(Y)$

. Indeed, we consider the composition

$C_p(Y)\neq C_p^*(Y)$

. Indeed, we consider the composition

![]() $T\circ i$

, where

$T\circ i$

, where

![]() $i:C_p(\beta X)\to C_p^*(X)$

is the restriction map. Then, according to [Reference Uspenskii21, Proposition 2], Y is pseudocompact and

$i:C_p(\beta X)\to C_p^*(X)$

is the restriction map. Then, according to [Reference Uspenskii21, Proposition 2], Y is pseudocompact and

![]() $C_p(Y)=C_p^*(Y)$

.

$C_p(Y)=C_p^*(Y)$

.

We consider properties

![]() $\mathcal P$

of

$\mathcal P$

of

![]() $\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces such that:

$\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces such that:

-

(a) if

$X\in \mathcal P$

and

$X\in \mathcal P$

and

$F\subset X$

is closed, then

$F\subset X$

is closed, then

$F\in \mathcal P$

;

$F\in \mathcal P$

; -

(b) if X is a countable union of closed subsets each having the property

$\mathcal P$

, then

$\mathcal P$

, then

$X\in \mathcal P$

;

$X\in \mathcal P$

; -

(c) if

$f:X\to Y$

is a perfect map with countable fibers and

$f:X\to Y$

is a perfect map with countable fibers and

$Y\in \mathcal P$

, then

$Y\in \mathcal P$

, then

$X\in \mathcal P$

.

$X\in \mathcal P$

.

For example, zero-dimensionality, strongly countable-dimensionality, and C-space property are finitely multiplicative properties satisfying conditions (a)–(c). Another two properties of this type, but not finitely multiplicative, are weakly infinite-dimensionality, or

![]() $(m-C)$

-spaces in the sense of Fedorchuk [Reference Fedorchuk4]. The definition of all dimension-like properties mentioned above, and explanations that they satisfy conditions (a)–(c) can be found at the end of Section 2.

$(m-C)$

-spaces in the sense of Fedorchuk [Reference Fedorchuk4]. The definition of all dimension-like properties mentioned above, and explanations that they satisfy conditions (a)–(c) can be found at the end of Section 2.

For

![]() $\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces, we have the following version of Theorem 1.1 (actually Theorem 1.3 below is true for any topological property

$\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces, we have the following version of Theorem 1.1 (actually Theorem 1.3 below is true for any topological property

![]() $\mathcal P$

satisfying conditions (a)–(c)).

$\mathcal P$

satisfying conditions (a)–(c)).

Theorem 1.3 Suppose X and Y are

![]() $\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces and let

$\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces and let

![]() $T:D_p(X)\to D_p(Y)$

be a c-good uniformly continuous surjection for some

$T:D_p(X)\to D_p(Y)$

be a c-good uniformly continuous surjection for some

![]() $c>0$

. If all finite powers of X are weakly infinite-dimensional or

$c>0$

. If all finite powers of X are weakly infinite-dimensional or

![]() $(m-C)$

-spaces, then all finite powers of Y are also weakly infinite-dimensional or

$(m-C)$

-spaces, then all finite powers of Y are also weakly infinite-dimensional or

![]() $(m-C)$

-spaces.

$(m-C)$

-spaces.

Krupski [Reference Krupski11] proved similar result for

![]() $\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces: if

$\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces: if

![]() $T:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

is a continuous open surjection and all powers of X are weakly infinite-dimensional or

$T:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

is a continuous open surjection and all powers of X are weakly infinite-dimensional or

![]() $(m-C)$

-spaces, then Y is also weakly infinite-dimensional of has the property

$(m-C)$

-spaces, then Y is also weakly infinite-dimensional of has the property

![]() $m-C$

. Theorem 1.3 was established in [Reference Gorak, Krupski and Marciszewski6] in the special case when

$m-C$

. Theorem 1.3 was established in [Reference Gorak, Krupski and Marciszewski6] in the special case when

![]() $X,Y$

are compact metrizable spaces and the property is either zero-dimensionality or strong countable-dimensionality.

$X,Y$

are compact metrizable spaces and the property is either zero-dimensionality or strong countable-dimensionality.

The notion of c-good maps is crucial in the proof of the above results. One of the referees observed that if

![]() $X=Y$

is the space of natural numbers, then the continuous linear surjection

$X=Y$

is the space of natural numbers, then the continuous linear surjection

![]() $T:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

,

$T:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

,

![]() $T(f)(n)=\frac {1}{n+1}f(n)$

, is not c-good for any c. Therefore, as the referee suggested, the more interesting question is whether the existence of a linear continuous surjection

$T(f)(n)=\frac {1}{n+1}f(n)$

, is not c-good for any c. Therefore, as the referee suggested, the more interesting question is whether the existence of a linear continuous surjection

![]() $T:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

implies the existence of another linear continuous surjection

$T:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

implies the existence of another linear continuous surjection

![]() $S:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

which is c-good for some

$S:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

which is c-good for some

![]() $c>0$

. In that connection, let us note that more general notion was considered in our recent paper [Reference Eysen, Leiderman and Valov3]:

$c>0$

. In that connection, let us note that more general notion was considered in our recent paper [Reference Eysen, Leiderman and Valov3]:

![]() $T:D_p(X)\to D_p(Y)$

is inversely bounded if for every norm bounded sequence

$T:D_p(X)\to D_p(Y)$

is inversely bounded if for every norm bounded sequence

![]() $\{g_n\}\subset C^*(Y)$

there exists a norm bounded sequence

$\{g_n\}\subset C^*(Y)$

there exists a norm bounded sequence

![]() $\{f_n\}\subset C^*(X)$

with

$\{f_n\}\subset C^*(X)$

with

![]() $T(f_n)=g_n$

for all n. Evidently, every c-good map is inversely bounded. It was established in [Reference Eysen, Leiderman and Valov3] that uniformly continuous inversely bounded surjections

$T(f_n)=g_n$

for all n. Evidently, every c-good map is inversely bounded. It was established in [Reference Eysen, Leiderman and Valov3] that uniformly continuous inversely bounded surjections

![]() $T:D_p(X)\to D_p(Y)$

, where X and Y are metrizable, preserve any one of the properties zero-dimensionality, countable-dimensionality, or strong countable-dimensionality. Most probably Theorem 1.1 remains true if the surjection T is uniformly continuous and inversely bounded.

$T:D_p(X)\to D_p(Y)$

, where X and Y are metrizable, preserve any one of the properties zero-dimensionality, countable-dimensionality, or strong countable-dimensionality. Most probably Theorem 1.1 remains true if the surjection T is uniformly continuous and inversely bounded.

Finally, here is the theorem which provides a positive answer to the question of Kawamura–Leiderman [Reference Kawamura and Leiderman10, Problem 3.1] mentioned above.

Theorem 1.4 Let

![]() $T:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

be a linear continuous surjection. If

$T:C_p(X)\to C_p(Y)$

be a linear continuous surjection. If

![]() $\dim X=0$

, then

$\dim X=0$

, then

![]() $\dim Y=0$

.

$\dim Y=0$

.

2 Preliminary results

In this section, we prove Proposition 2.1 which is used in the proofs of Theorems 1.1 and 1.3. Our proof is based on the idea of support introduced by Gul’ko [Reference Gul’ko7] and the extension of this notion introduced by Krupski [Reference Krupski12].

Let

![]() $\mathbb Q$

be the set of rational numbers. A subspace

$\mathbb Q$

be the set of rational numbers. A subspace

![]() $E(X)\subset C(X)$

is called a

$E(X)\subset C(X)$

is called a

![]() $QS$

-algebra [Reference Gul’ko7] if it satisfies the following conditions: (i) if

$QS$

-algebra [Reference Gul’ko7] if it satisfies the following conditions: (i) if

![]() $f,g\in E(X)$

and

$f,g\in E(X)$

and

![]() $\lambda \in \mathbb Q$

, then all functions

$\lambda \in \mathbb Q$

, then all functions

![]() $f+g$

,

$f+g$

,

![]() $f\cdot g$

, and

$f\cdot g$

, and

![]() $\lambda f$

belong to

$\lambda f$

belong to

![]() $E(X)$

and (ii) for every

$E(X)$

and (ii) for every

![]() $x\in X$

and its neighborhood U in X there is

$x\in X$

and its neighborhood U in X there is

![]() $f\in E(X)$

such that

$f\in E(X)$

such that

![]() $f(x)=1$

and

$f(x)=1$

and

![]() $f(X\backslash U)=0$

.

$f(X\backslash U)=0$

.

We are using the following facts from [Reference Gul’ko7].

-

(2.1) If X has a countable base and

$\Phi \subset C(X)$

is a countable set, then there is a countable

$\Phi \subset C(X)$

is a countable set, then there is a countable

$QS$

-algebra

$QS$

-algebra

$E(X)\subset C(X)$

containing

$E(X)\subset C(X)$

containing

$\Phi $

. Moreover, it follows from the proof of [Reference Gul’ko7, Proposition 1.2] that

$\Phi $

. Moreover, it follows from the proof of [Reference Gul’ko7, Proposition 1.2] that

$E(X)\subset C^*(X)$

provided that

$E(X)\subset C^*(X)$

provided that

$\Phi \subset C^*(X)$

.

$\Phi \subset C^*(X)$

. -

(2.2) If U is an open set in X,

$x_1,x_2,\ldots ,x_k\in U$

and

$x_1,x_2,\ldots ,x_k\in U$

and

$\lambda _1,\lambda _2,\ldots ,\lambda _k\in \mathbb Q$

, then there exists

$\lambda _1,\lambda _2,\ldots ,\lambda _k\in \mathbb Q$

, then there exists

$f\in E(X)$

such that

$f\in E(X)$

such that

$f(x_i)=\lambda _i$

for each i and

$f(x_i)=\lambda _i$

for each i and

$f(X\backslash U)=0$

.

$f(X\backslash U)=0$

. -

(2.3) We consider the following condition for a

$QS$

-algebra

$QS$

-algebra

$E(X)$

on X: For every compact set

$E(X)$

on X: For every compact set

$K\subset X$

and an open set W containing K there exists

$K\subset X$

and an open set W containing K there exists

$f\in E(X)$

with

$f\in E(X)$

with

$f|K=1$

,

$f|K=1$

,

$f|(X\backslash W)=0$

and

$f|(X\backslash W)=0$

and

$f(x)\in [0,1]$

for all

$f(x)\in [0,1]$

for all

$x\in X$

. Note that if X has a countable base

$x\in X$

. Note that if X has a countable base

$\mathcal B$

, then there is a countable

$\mathcal B$

, then there is a countable

$QS$

-algebra

$QS$

-algebra

$E(X)$

on X satisfying that condition. Indeed, we can assume that

$E(X)$

on X satisfying that condition. Indeed, we can assume that

$\mathcal B$

is closed under finite unions and find

$\mathcal B$

is closed under finite unions and find

$U,V\in \mathcal B$

such that

$U,V\in \mathcal B$

such that

$K\subset V\subset \overline V\subset U\subset \overline U\subset W$

. Then, consider the set

$K\subset V\subset \overline V\subset U\subset \overline U\subset W$

. Then, consider the set

$\Phi $

of all functions

$\Phi $

of all functions

$f_{U,V}:X\to [0,1]$

, where

$f_{U,V}:X\to [0,1]$

, where

$\overline V\subset U$

with

$\overline V\subset U$

with

$U,V\in \mathcal B$

, such that

$U,V\in \mathcal B$

, such that

$f_{V,U}|\overline V=1$

and

$f_{V,U}|\overline V=1$

and

$f_{V,U}|(X\backslash U)=0$

. According to

$f_{V,U}|(X\backslash U)=0$

. According to

$(2.1)$

,

$(2.1)$

,

$\Phi $

can be extended to a countable

$\Phi $

can be extended to a countable

$QS$

-algebra

$QS$

-algebra

$E(X)$

on X.

$E(X)$

on X.

Everywhere below, we denote by

![]() $\overline {\mathbb R}$

the extended real line

$\overline {\mathbb R}$

the extended real line

![]() $[-\infty ,\infty ]$

.

$[-\infty ,\infty ]$

.

Proposition 2.1 Let

![]() $\overline X$

and

$\overline X$

and

![]() $\overline Y$

be metrizable compactifications of X and Y, and

$\overline Y$

be metrizable compactifications of X and Y, and

![]() ${H\subset \overline X}$

be a

${H\subset \overline X}$

be a

![]() $\sigma $

-compact space containing X. Suppose

$\sigma $

-compact space containing X. Suppose

![]() $E(H)$

is a

$E(H)$

is a

![]() $QS$

-algebra on H satisfying condition (2.3),

$QS$

-algebra on H satisfying condition (2.3),

![]() $E(X)=\{\overline f|X:\overline f\in E(H)\}$

and

$E(X)=\{\overline f|X:\overline f\in E(H)\}$

and

![]() $E(Y)\subset C(Y)$

is a family such that every

$E(Y)\subset C(Y)$

is a family such that every

![]() $g\in E(Y)$

is extendable to a map

$g\in E(Y)$

is extendable to a map

![]() $\overline g:\overline Y\to \overline {\mathbb R}$

and

$\overline g:\overline Y\to \overline {\mathbb R}$

and

![]() $E(\overline Y)=\{\overline g:g\in E(Y)\}$

contains a

$E(\overline Y)=\{\overline g:g\in E(Y)\}$

contains a

![]() $QS$

-algebra on

$QS$

-algebra on

![]() $\overline Y$

. Let also

$\overline Y$

. Let also

![]() $\varphi :E_p(X)\to E_p(Y)$

be a uniformly continuous surjection which is c-good for some

$\varphi :E_p(X)\to E_p(Y)$

be a uniformly continuous surjection which is c-good for some

![]() $c>0$

.

$c>0$

.

If all finite powers of H have a property

![]() $\mathcal P$

satisfying conditions (a)–(c), then there exists a

$\mathcal P$

satisfying conditions (a)–(c), then there exists a

![]() $\sigma $

-compact set

$\sigma $

-compact set

![]() $Y_\infty \subset \overline Y$

containing Y such that all finite powers of

$Y_\infty \subset \overline Y$

containing Y such that all finite powers of

![]() $Y_\infty $

have the same property

$Y_\infty $

have the same property

![]() $\mathcal P$

.

$\mathcal P$

.

Proof We fix a countable base

![]() $\mathcal B$

of H which is closed under finite unions, and denote by f the restriction

$\mathcal B$

of H which is closed under finite unions, and denote by f the restriction

![]() $\overline f|X$

of any

$\overline f|X$

of any

![]() $\overline f\in E(H)$

. For every

$\overline f\in E(H)$

. For every

![]() $y\in \overline Y$

, there is a map

$y\in \overline Y$

, there is a map

![]() $\alpha _y:E(H)\to \overline {\mathbb R}$

,

$\alpha _y:E(H)\to \overline {\mathbb R}$

,

![]() $\alpha _y(\overline f)=\overline {\varphi (f)}(y)$

. Since

$\alpha _y(\overline f)=\overline {\varphi (f)}(y)$

. Since

![]() $\varphi $

is uniformly continuous, so is the map

$\varphi $

is uniformly continuous, so is the map

![]() $\beta _y:E_p(X)\to \mathbb R$

,

$\beta _y:E_p(X)\to \mathbb R$

,

![]() $\beta _y(f)=\varphi (f)(y)$

. Let

$\beta _y(f)=\varphi (f)(y)$

. Let

![]() $H=\bigcup _kH_k$

be the union of an increasing sequence

$H=\bigcup _kH_k$

be the union of an increasing sequence

![]() $\{H_k\}$

of compact sets. Following Krupski [Reference Krupski12], for every

$\{H_k\}$

of compact sets. Following Krupski [Reference Krupski12], for every

![]() $y\in \overline Y$

and every

$y\in \overline Y$

and every

![]() $p,k\in \mathbb N$

, we define the families

$p,k\in \mathbb N$

, we define the families

and

where

Possibly, some or both of the values

![]() $\alpha _y(\overline f),\alpha _y(\overline g)$

from the definition of

$\alpha _y(\overline f),\alpha _y(\overline g)$

from the definition of

![]() $a(y,K)$

could be

$a(y,K)$

could be

![]() $\pm \infty $

. That’s why we use the following agreements:

$\pm \infty $

. That’s why we use the following agreements:

-

(2.4)

$\infty +\infty =\infty , \infty -\infty =-\infty +\infty =0, -\infty -\infty =-\infty .$

$\infty +\infty =\infty , \infty -\infty =-\infty +\infty =0, -\infty -\infty =-\infty .$

Note that

![]() $a(y,\varnothing )=\infty $

since

$a(y,\varnothing )=\infty $

since

![]() $\varphi $

is surjective.

$\varphi $

is surjective.

Using that

![]() $E(X)$

and

$E(X)$

and

![]() $E(H)$

are

$E(H)$

are

![]() $QS$

-algebras on X and H, and following the arguments from Krupski’s paper [Reference Krupski12] (see also the proofs of [Reference Gul’ko7, Proposition 1.4] and [Reference Marciszewski and Pelant16, Proposition 3.1]), one can establish the following claims (for the sake of completeness, we provide the proofs).

$QS$

-algebras on X and H, and following the arguments from Krupski’s paper [Reference Krupski12] (see also the proofs of [Reference Gul’ko7, Proposition 1.4] and [Reference Marciszewski and Pelant16, Proposition 3.1]), one can establish the following claims (for the sake of completeness, we provide the proofs).

Claim 1 For every

![]() $y\in Y$

, there is

$y\in Y$

, there is

![]() $p,k\in \mathbb N$

such that

$p,k\in \mathbb N$

such that

![]() $\mathcal A_p^k(y)$

contains a finite nonempty subset of X.

$\mathcal A_p^k(y)$

contains a finite nonempty subset of X.

This claim follows from the proof of [Reference Krupski12, Proposition 2.1]. Indeed, since

![]() $\varphi $

is uniformly continuous there is

$\varphi $

is uniformly continuous there is

![]() $p\in \mathbb N$

and a finite set

$p\in \mathbb N$

and a finite set

![]() $K\subset X$

such that if

$K\subset X$

such that if

![]() $f,g\in E(X)$

and

$f,g\in E(X)$

and

![]() $|f(x)-g(x)|<1/p$

for every

$|f(x)-g(x)|<1/p$

for every

![]() $x\in K$

, then

$x\in K$

, then

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|=|\varphi (f)(y)-\varphi (g)(y)|<1$

. Take arbitrary

$|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|=|\varphi (f)(y)-\varphi (g)(y)|<1$

. Take arbitrary

![]() $\overline f,\overline g\in E(H)$

with

$\overline f,\overline g\in E(H)$

with

![]() $|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for every

$|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for every

![]() $x\in K$

and consider the functions

$x\in K$

and consider the functions

![]() $\overline f_m=\overline f+ \frac {m}{p}(\overline g-\overline f)\in E(H)$

for each

$\overline f_m=\overline f+ \frac {m}{p}(\overline g-\overline f)\in E(H)$

for each

![]() $m=0,1,\ldots ,p$

. Obviously

$m=0,1,\ldots ,p$

. Obviously

![]() $|f_m(x)-f_{m+1}(x)|<1/p$

for all

$|f_m(x)-f_{m+1}(x)|<1/p$

for all

![]() $x\in K$

, so

$x\in K$

, so

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline f_m)-\alpha _y(\overline f_{m+1})|<1$

. Consequently,

$|\alpha _y(\overline f_m)-\alpha _y(\overline f_{m+1})|<1$

. Consequently,

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|\leq \sum _{m=0}^{p-1}|\alpha _y(\overline f_m)-\alpha _y(\overline f_{m+1})|<p$

. Because K is finite, there is

$|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|\leq \sum _{m=0}^{p-1}|\alpha _y(\overline f_m)-\alpha _y(\overline f_{m+1})|<p$

. Because K is finite, there is

![]() $k\in \mathbb N$

with

$k\in \mathbb N$

with

![]() $K\subset H_k$

. Hence,

$K\subset H_k$

. Hence,

![]() $K\in \mathcal A_p^k(y)$

.

$K\in \mathcal A_p^k(y)$

.

Consider the sets

![]() $Y_p^k=\{y\in \overline Y:\mathcal A_p^k(y)\neq \varnothing \}$

,

$Y_p^k=\{y\in \overline Y:\mathcal A_p^k(y)\neq \varnothing \}$

,

![]() $p,k\in \mathbb N$

.

$p,k\in \mathbb N$

.

Claim 2 Each

![]() $Y_p^k$

is a closed subset of

$Y_p^k$

is a closed subset of

![]() $\overline Y$

.

$\overline Y$

.

We use the proof of [Reference Krupski12, Lemma 2.2]. Suppose

![]() $y\not \in Y_p^k$

. Since

$y\not \in Y_p^k$

. Since

![]() $y\in Y_p^k$

iff

$y\in Y_p^k$

iff

![]() $H_k\in \mathcal A_p^k(y)$

,

$H_k\in \mathcal A_p^k(y)$

,

![]() $H_k\not \in \mathcal A_p^k(y)$

. So, there exist

$H_k\not \in \mathcal A_p^k(y)$

. So, there exist

![]() $\overline f,\overline g\in E(H)$

with

$\overline f,\overline g\in E(H)$

with

![]() $|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

$|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

![]() $x\in H_k$

and

$x\in H_k$

and

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|>p$

. Then,

$|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|>p$

. Then,

![]() $V=\{z\in \overline Y: |\alpha _z(\overline f)-\alpha _z(\overline g)|>p\}$

is a neighborhood of y with

$V=\{z\in \overline Y: |\alpha _z(\overline f)-\alpha _z(\overline g)|>p\}$

is a neighborhood of y with

![]() $V\cap Y_p^k=\varnothing $

.

$V\cap Y_p^k=\varnothing $

.

Claim 3 Every set

![]() $Y_{p,q}^k=\{y\in Y_p^k: \exists K\in \mathcal A_p^k(y){~}\mbox {with}{~}|K|\leq q\}$

,

$Y_{p,q}^k=\{y\in Y_p^k: \exists K\in \mathcal A_p^k(y){~}\mbox {with}{~}|K|\leq q\}$

,

![]() $p,q,k\in \mathbb N$

, is closed in

$p,q,k\in \mathbb N$

, is closed in

![]() $Y_p^k$

.

$Y_p^k$

.

Following the proof of [Reference Krupski12, Lemma 2.3], we first show that the set

![]() $Z=\{(y,K)\in Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}:K\in \mathcal A_p^k(y)\}$

is closed in

$Z=\{(y,K)\in Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}:K\in \mathcal A_p^k(y)\}$

is closed in

![]() $Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}$

, where

$Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}$

, where

![]() $[H_k]^{\leq q}$

denotes the space of all subsets

$[H_k]^{\leq q}$

denotes the space of all subsets

![]() $K\subset H_k$

of cardinality

$K\subset H_k$

of cardinality

![]() $\leq q$

endowed with the Vietoris topology. Indeed, if

$\leq q$

endowed with the Vietoris topology. Indeed, if

![]() $(y,K)\in Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}\backslash Z$

, then

$(y,K)\in Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}\backslash Z$

, then

![]() $K\not \in \mathcal A_p^k(y)$

. Hence,

$K\not \in \mathcal A_p^k(y)$

. Hence,

![]() $a(y,K)>p$

and there are

$a(y,K)>p$

and there are

![]() $\overline f,\overline g\in E(H)$

such that

$\overline f,\overline g\in E(H)$

such that

![]() $|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

$|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

![]() $x\in K$

and

$x\in K$

and

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|>p$

. Let

$|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|>p$

. Let

![]() $U=\{z\in Y_p^k: |\alpha _z(\overline f)-\alpha _z(\overline g)|>p\}$

and

$U=\{z\in Y_p^k: |\alpha _z(\overline f)-\alpha _z(\overline g)|>p\}$

and

![]() $V=\{x\in H_k:|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1\}$

. The set

$V=\{x\in H_k:|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1\}$

. The set

![]() $U\times <V>$

is a neighborhood of

$U\times <V>$

is a neighborhood of

![]() $(y,K)$

in

$(y,K)$

in

![]() $Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}$

disjoint from Z (here

$Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}$

disjoint from Z (here

![]() $<V>=\{F\in [H_k]^{\leq q}: F\subset V\}$

). Since

$<V>=\{F\in [H_k]^{\leq q}: F\subset V\}$

). Since

![]() $Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}$

is compact and

$Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}$

is compact and

![]() $Y_{p,q}^k$

is the image of Z under the projection

$Y_{p,q}^k$

is the image of Z under the projection

![]() $Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}\to Y_p^k$

,

$Y_p^k\times [H_k]^{\leq q}\to Y_p^k$

,

![]() $Y_{p,q}^k$

is closed in

$Y_{p,q}^k$

is closed in

![]() $Y_p^k$

.

$Y_p^k$

.

For every k, let

![]() $Y_k=\bigcup _{p,q}Y_{p,q}^k$

. Obviously,

$Y_k=\bigcup _{p,q}Y_{p,q}^k$

. Obviously,

![]() $Y_k\subset \{y\in \overline Y:\mathcal A^k(y)\neq \varnothing \}$

. Since

$Y_k\subset \{y\in \overline Y:\mathcal A^k(y)\neq \varnothing \}$

. Since

![]() ${H_k\subset H_{k+1}}$

for all k, the sequence

${H_k\subset H_{k+1}}$

for all k, the sequence

![]() $\{Y_k\}$

is increasing. It may happen that

$\{Y_k\}$

is increasing. It may happen that

![]() $Y_k=\varnothing $

for some k, but Claim 1 implies that

$Y_k=\varnothing $

for some k, but Claim 1 implies that

![]() $Y\subset \bigcup _{k}Y_{k}$

.

$Y\subset \bigcup _{k}Y_{k}$

.

Claim 4 For every

![]() $y\in Y_k$

, the family

$y\in Y_k$

, the family

![]() $\mathcal A^k(y)$

is closed under finite intersections and

$\mathcal A^k(y)$

is closed under finite intersections and

![]() $a(y,K_1\cap K_2)\leq a(y,K_1)+a(y,K_2)$

for all

$a(y,K_1\cap K_2)\leq a(y,K_1)+a(y,K_2)$

for all

![]() $K_1,K_2\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

.

$K_1,K_2\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

.

We follow the proof of [Reference Krupski12, Lemma 2.5] to show that

![]() $K_1\cap K_2\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

for any

$K_1\cap K_2\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

for any

![]() $K_1,K_2\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

. Let

$K_1,K_2\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

. Let

![]() $\overline f,\overline g\in E(H)$

with

$\overline f,\overline g\in E(H)$

with

![]() $|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

$|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

![]() $x\in K_1\cap K_2$

and

$x\in K_1\cap K_2$

and

![]() $U=\{x\in H:|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1\}$

. Take an open set W in H containing

$U=\{x\in H:|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1\}$

. Take an open set W in H containing

![]() $K_1$

with

$K_1$

with

![]() $W\cap K_2\subset U$

and choose

$W\cap K_2\subset U$

and choose

![]() $\overline u\in E(H)$

such that

$\overline u\in E(H)$

such that

![]() $\overline u|K_1=1$

,

$\overline u|K_1=1$

,

![]() $\overline u|(H\backslash W)=0$

and

$\overline u|(H\backslash W)=0$

and

![]() $\overline u(x)\in [0,1]$

for all

$\overline u(x)\in [0,1]$

for all

![]() $x\in H$

(see condition (2.3)). Then,

$x\in H$

(see condition (2.3)). Then,

![]() $\overline h=\overline u\cdot (\overline f-\overline g)+\overline g\in E(H)$

,

$\overline h=\overline u\cdot (\overline f-\overline g)+\overline g\in E(H)$

,

![]() $\overline h|K_1=\overline f|K_1$

,

$\overline h|K_1=\overline f|K_1$

,

![]() $\overline h|(K_2\backslash W)=\overline g|(K_2\backslash W)$

, and

$\overline h|(K_2\backslash W)=\overline g|(K_2\backslash W)$

, and

![]() $|\overline h(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for

$|\overline h(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for

![]() $x\in K_2$

. Since

$x\in K_2$

. Since

![]() $K_1\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

and

$K_1\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

and

![]() $\overline h|K_1=\overline f|K_1$

, we have

$\overline h|K_1=\overline f|K_1$

, we have

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline h)|\leq a(y,K_1)<\infty $

. Similarly,

$|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline h)|\leq a(y,K_1)<\infty $

. Similarly,

![]() $K_2\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

and

$K_2\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

and

![]() $|\overline h(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for

$|\overline h(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for

![]() $x\in K_2$

imply

$x\in K_2$

imply

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline h)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|\leq a(y,K_2)<\infty $

. Therefore,

$|\alpha _y(\overline h)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|\leq a(y,K_2)<\infty $

. Therefore,

Note that the last inequality is true if some of

![]() $\alpha _y(\overline f), \alpha _y(\overline h), \alpha _y(\overline g)$

are

$\alpha _y(\overline f), \alpha _y(\overline h), \alpha _y(\overline g)$

are

![]() $\pm \infty $

. Indeed, if

$\pm \infty $

. Indeed, if

![]() $\alpha _y(\overline f)=\pm \infty $

, then

$\alpha _y(\overline f)=\pm \infty $

, then

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline h)|<\infty $

implies

$|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline h)|<\infty $

implies

![]() $\alpha _y(\overline h)=\pm \infty $

. Consequently,

$\alpha _y(\overline h)=\pm \infty $

. Consequently,

![]() ${\alpha _y(\overline g)=\pm \infty} $

because

${\alpha _y(\overline g)=\pm \infty} $

because

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline h)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|<\infty $

. Similarly, if

$|\alpha _y(\overline h)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|<\infty $

. Similarly, if

![]() $\alpha _y(\overline h)=\pm \infty $

or

$\alpha _y(\overline h)=\pm \infty $

or

![]() $\alpha _y(\overline g)=\pm \infty $

, then the other two are also

$\alpha _y(\overline g)=\pm \infty $

, then the other two are also

![]() $\pm \infty $

. Hence,

$\pm \infty $

. Hence,

![]() $a(y,K_1\cap K_2)\leq a(y,K_1)+a(y,K_2)$

, which means that

$a(y,K_1\cap K_2)\leq a(y,K_1)+a(y,K_2)$

, which means that

![]() $K_1\cap K_2\neq \varnothing $

(otherwise,

$K_1\cap K_2\neq \varnothing $

(otherwise,

![]() $a(y,K_1\cap K_2)=\infty $

) and

$a(y,K_1\cap K_2)=\infty $

) and

![]() $K_1\cap K_2\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

.

$K_1\cap K_2\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

.

Since each family

![]() $\mathcal A^k(y)$

,

$\mathcal A^k(y)$

,

![]() $y\in Y_k$

, consists of compact subsets of

$y\in Y_k$

, consists of compact subsets of

![]() $H_k$

,

$H_k$

,

![]() $K(y,k)=\bigcap \mathcal A^k(y)$

is nonempty and compact.

$K(y,k)=\bigcap \mathcal A^k(y)$

is nonempty and compact.

Claim 5 For every

![]() $y\in Y_{k}$

, the set

$y\in Y_{k}$

, the set

![]() $K(y,k)$

is a nonempty finite subset of

$K(y,k)$

is a nonempty finite subset of

![]() $H_k$

with

$H_k$

with

![]() $K(y,k)\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

. Moreover, if

$K(y,k)\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

. Moreover, if

![]() $y\in Y$

, then there exists k such that

$y\in Y$

, then there exists k such that

![]() $y\in Y_k$

and

$y\in Y_k$

and

![]() ${K(y,k)\subset X}$

.

${K(y,k)\subset X}$

.

Let

![]() $y\in Y_k$

. We already observed that

$y\in Y_k$

. We already observed that

![]() $K(y,k)$

is compact and nonempty. Since

$K(y,k)$

is compact and nonempty. Since

![]() $y\in Y_{p,q}^k$

for some

$y\in Y_{p,q}^k$

for some

![]() $p,q$

,

$p,q$

,

![]() $\mathcal A^k(y)$

contains finite sets. Hence,

$\mathcal A^k(y)$

contains finite sets. Hence,

![]() $K(y,k)$

is also finite and

$K(y,k)$

is also finite and

![]() $K(y,k)\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

because it is an intersection of finitely many elements of

$K(y,k)\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

because it is an intersection of finitely many elements of

![]() $\mathcal A^k(y)$

. If

$\mathcal A^k(y)$

. If

![]() $y\in Y$

, then by Claim 1, there is k such that

$y\in Y$

, then by Claim 1, there is k such that

![]() $\mathcal A^k(y)$

contains a finite subset of X. Since

$\mathcal A^k(y)$

contains a finite subset of X. Since

![]() $K(y,k)$

is the minimal element of

$K(y,k)$

is the minimal element of

![]() $\mathcal A^k(y)$

, it is also a subset of X.

$\mathcal A^k(y)$

, it is also a subset of X.

Following [Reference Gul’ko7], for every k, we define

![]() $M^k(p,1)=Y_{p,1}^k$

and

$M^k(p,1)=Y_{p,1}^k$

and

![]() $M^k(p,q)=Y_{p,q}^k\backslash Y_{2p,q-1}^k$

if

$M^k(p,q)=Y_{p,q}^k\backslash Y_{2p,q-1}^k$

if

![]() $q\geq 2$

.

$q\geq 2$

.

Claim 6

![]() $Y_k=\bigcup \{M^k(p,q):p,q=1,2,\ldots \}$

and for every

$Y_k=\bigcup \{M^k(p,q):p,q=1,2,\ldots \}$

and for every

![]() $y\in M^k(p,q)$

, there exists a unique set

$y\in M^k(p,q)$

, there exists a unique set

![]() $K_{kp}(y)\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

of cardinality q such that

$K_{kp}(y)\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

of cardinality q such that

![]() $a(y,K_{kp}(y))\leq p$

.

$a(y,K_{kp}(y))\leq p$

.

Since

![]() $M^k(p,q)\subset Y^k_{p,q}\subset Y_k$

,

$M^k(p,q)\subset Y^k_{p,q}\subset Y_k$

,

![]() $\bigcup \{M^k(p,q):p,q=1,2,\ldots \}\subset Y_k$

. If

$\bigcup \{M^k(p,q):p,q=1,2,\ldots \}\subset Y_k$

. If

![]() $y\in Y_k$

, then

$y\in Y_k$

, then

![]() $K(y,k)\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

is a finite subset of

$K(y,k)\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

is a finite subset of

![]() $H_k$

. Assume

$H_k$

. Assume

![]() $|K(y,k)|=q$

and

$|K(y,k)|=q$

and

![]() $a(y,K(y,k))\leq p$

for some

$a(y,K(y,k))\leq p$

for some

![]() $p,q$

. So,

$p,q$

. So,

![]() $y\in Y_{p,q}^k$

. Moreover,

$y\in Y_{p,q}^k$

. Moreover,

![]() $y\not \in Y_{2p,q-1}^k$

, otherwise, there would be

$y\not \in Y_{2p,q-1}^k$

, otherwise, there would be

![]() $K\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

with

$K\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

with

![]() $a(y,K)\leq 2p$

and

$a(y,K)\leq 2p$

and

![]() $|K|\leq q-1$

. The last inequality contradicts the minimality of

$|K|\leq q-1$

. The last inequality contradicts the minimality of

![]() $K(y,k)$

. Hence,

$K(y,k)$

. Hence,

![]() $y\in M^k(p,q)$

which shows that

$y\in M^k(p,q)$

which shows that

![]() $Y_k=\bigcup \{M^k(p,q):p,q=1,2,\ldots \}$

.

$Y_k=\bigcup \{M^k(p,q):p,q=1,2,\ldots \}$

.

Suppose

![]() $y\in M^k(p,q)$

. Then, there exists a set

$y\in M^k(p,q)$

. Then, there exists a set

![]() $K\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

with

$K\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

with

![]() $a(y,K)\leq p$

and

$a(y,K)\leq p$

and

![]() $|K|\leq q$

. Since,

$|K|\leq q$

. Since,

![]() $y\not \in Y_{2p,q-1}^k$

,

$y\not \in Y_{2p,q-1}^k$

,

![]() $|K|=q$

. If there exists another

$|K|=q$

. If there exists another

![]() $K'\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

with

$K'\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

with

![]() $a(y,K')\leq p$

and

$a(y,K')\leq p$

and

![]() $|K'|=q$

, then

$|K'|=q$

, then

![]() $K\cap K'\neq \varnothing $

,

$K\cap K'\neq \varnothing $

,

![]() $|K\cap K'|\leq q-1$

and, by Claim 4,

$|K\cap K'|\leq q-1$

and, by Claim 4,

![]() $a(y,K\cap K')\leq a(y,K)+ a(y,K')\leq 2p$

. This means that

$a(y,K\cap K')\leq a(y,K)+ a(y,K')\leq 2p$

. This means that

![]() $y\in Y_{2p,q-1}^k$

, a contradiction. Hence, there exists a unique

$y\in Y_{2p,q-1}^k$

, a contradiction. Hence, there exists a unique

![]() $K_{kp}(y)\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

such that

$K_{kp}(y)\in \mathcal A^k(y)$

such that

![]() $a(y,K_{kp}(y))\leq p$

and

$a(y,K_{kp}(y))\leq p$

and

![]() $|K_{kp}(y)|=q$

.

$|K_{kp}(y)|=q$

.

For every q, let

![]() $[H_k]^q$

denote the set of all q-points subsets of

$[H_k]^q$

denote the set of all q-points subsets of

![]() $H_k$

endowed with the Vietoris topology.

$H_k$

endowed with the Vietoris topology.

Claim 7 The map

![]() $\Phi _{kpq}:M^k(p,q)\to [H_k]^q$

,

$\Phi _{kpq}:M^k(p,q)\to [H_k]^q$

,

![]() $\Phi _{kpq}(y)=K_{kp}(y)$

, is continuous.

$\Phi _{kpq}(y)=K_{kp}(y)$

, is continuous.

Because

![]() $K_{kp}(y)\subset H_k$

consists of q points for all

$K_{kp}(y)\subset H_k$

consists of q points for all

![]() $y\in M^k(p,q)$

, it suffices to show that if

$y\in M^k(p,q)$

, it suffices to show that if

![]() $K_{kp}(y)\cap U\neq \varnothing $

for some open

$K_{kp}(y)\cap U\neq \varnothing $

for some open

![]() $U\subset H$

, then there is a neighborhood V of y in

$U\subset H$

, then there is a neighborhood V of y in

![]() $\overline Y$

with

$\overline Y$

with

![]() $K_{kp}(z)\cap U\neq \varnothing $

for all

$K_{kp}(z)\cap U\neq \varnothing $

for all

![]() $z\in V\cap M^k(p,q)$

. We can assume that

$z\in V\cap M^k(p,q)$

. We can assume that

![]() $K_{kp}(y)\cap U$

contains exactly one point

$K_{kp}(y)\cap U$

contains exactly one point

![]() $x_0$

.

$x_0$

.

Let

![]() $q\geq 2$

, so

$q\geq 2$

, so

![]() $K_{kp}(y)=\{x_0,x_1,\ldots ,x_{q-1}\}$

. Since

$K_{kp}(y)=\{x_0,x_1,\ldots ,x_{q-1}\}$

. Since

![]() $y\not \in Y_{2p,q-1}^k$

we have

$y\not \in Y_{2p,q-1}^k$

we have

![]() $a(y,K)>2p$

, where

$a(y,K)>2p$

, where

![]() $K=\{x_1,\ldots ,x_{q-1}\}$

. Hence, there are

$K=\{x_1,\ldots ,x_{q-1}\}$

. Hence, there are

![]() $\overline f, \overline g\in E(H)$

such that

$\overline f, \overline g\in E(H)$

such that

![]() $|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

$|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

![]() $x\in K$

and

$x\in K$

and

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|>2p$

. The last inequality implies

$|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|>2p$

. The last inequality implies

![]() $\overline f(x_0)\neq \overline g(x_0)$

, otherwise,

$\overline f(x_0)\neq \overline g(x_0)$

, otherwise,

![]() $a(y,K_{kp}(y))$

would be greater than

$a(y,K_{kp}(y))$

would be greater than

![]() $2p$

(recall that

$2p$

(recall that

![]() $y\in M^k(p,q)$

implies

$y\in M^k(p,q)$

implies

![]() $a(y,K_{kp}(y))\leq p$

). So, at least one of the numbers

$a(y,K_{kp}(y))\leq p$

). So, at least one of the numbers

![]() $\overline f(x_0), \overline g(x_0)$

is not zero. Without loss of generality, we can assume that

$\overline f(x_0), \overline g(x_0)$

is not zero. Without loss of generality, we can assume that

![]() $\overline f(x_0)>0$

, and let r be a rational number with

$\overline f(x_0)>0$

, and let r be a rational number with

![]() $\frac {-1+\delta }{\overline f(x_0)}<r<\frac {1+\delta }{\overline f(x_0)}$

, where

$\frac {-1+\delta }{\overline f(x_0)}<r<\frac {1+\delta }{\overline f(x_0)}$

, where

![]() $\delta =\overline f(x_0)-\overline g(x_0)$

. Then,

$\delta =\overline f(x_0)-\overline g(x_0)$

. Then,

![]() $-1<(1-r)\overline f(x_0)-\overline g(x_0)<1$

, and choose

$-1<(1-r)\overline f(x_0)-\overline g(x_0)<1$

, and choose

![]() $\overline h_1\in E(H)$

such that

$\overline h_1\in E(H)$

such that

![]() $\overline h_1(x_0)=r$

and

$\overline h_1(x_0)=r$

and

![]() $\overline h_1(x)=0$

for all

$\overline h_1(x)=0$

for all

![]() $x\not \in U$

. Consider the function

$x\not \in U$

. Consider the function

![]() $\overline h=(1-\overline h_1)\overline f$

. Clearly,

$\overline h=(1-\overline h_1)\overline f$

. Clearly,

![]() $\overline h(x_0)=(1-r)\overline f(x_0)$

and

$\overline h(x_0)=(1-r)\overline f(x_0)$

and

![]() $\overline h(x)=\overline f(x)$

if

$\overline h(x)=\overline f(x)$

if

![]() $x\not \in U$

. Hence,

$x\not \in U$

. Hence,

![]() $\overline h\in E(H)$

and

$\overline h\in E(H)$

and

![]() $|\overline h(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

$|\overline h(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

![]() $x\in K_{kp}(y)$

. This implies

$x\in K_{kp}(y)$

. This implies

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline h)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|\leq p$

. Then,

$|\alpha _y(\overline h)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|\leq p$

. Then,

Observe that it is not possible

![]() $\alpha _y(\overline f)=\alpha _y(\overline h)=\pm \infty $

because

$\alpha _y(\overline f)=\alpha _y(\overline h)=\pm \infty $

because

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline h)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|\leq p$

would imply

$|\alpha _y(\overline h)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|\leq p$

would imply

![]() $\alpha _y(\overline g)=\pm \infty $

. Then,

$\alpha _y(\overline g)=\pm \infty $

. Then,

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|=0$

, a contradiction.

$|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|=0$

, a contradiction.

The set

![]() $V=\{z\in \overline Y:|\alpha _z(\overline f)-\alpha _z(\overline h)|>p\}$

is a neighborhood of y. Since

$V=\{z\in \overline Y:|\alpha _z(\overline f)-\alpha _z(\overline h)|>p\}$

is a neighborhood of y. Since

![]() $\overline h(x)=\overline f(x)$

for all

$\overline h(x)=\overline f(x)$

for all

![]() $x\not \in U$

,

$x\not \in U$

,

![]() $K_{kp}(z)\cap U=\varnothing $

for some

$K_{kp}(z)\cap U=\varnothing $

for some

![]() $z\in V\cap M^k(p,q)$

would imply

$z\in V\cap M^k(p,q)$

would imply

![]() $|\alpha _z(\overline h)-\alpha _z(\overline f)|\leq p$

, a contradiction. Therefore,

$|\alpha _z(\overline h)-\alpha _z(\overline f)|\leq p$

, a contradiction. Therefore,

![]() $K_{kp}(z)\cap U\neq \varnothing $

for

$K_{kp}(z)\cap U\neq \varnothing $

for

![]() $z\in V\cap M^k(p,q)$

.

$z\in V\cap M^k(p,q)$

.

If

![]() $q=1$

, then

$q=1$

, then

![]() $K_{kp}(y)=\{x_0\}$

and

$K_{kp}(y)=\{x_0\}$

and

![]() $K(y,k)=K_{kp}(y)$

. So,

$K(y,k)=K_{kp}(y)$

. So,

![]() $H_k\backslash U\not \in \mathcal A^k(y)$

(otherwise,

$H_k\backslash U\not \in \mathcal A^k(y)$

(otherwise,

![]() $K(y,k)\subset H_k\backslash U$

). Hence, there exist

$K(y,k)\subset H_k\backslash U$

). Hence, there exist

![]() $\overline f,\overline g\in E(H)$

such that

$\overline f,\overline g\in E(H)$

such that

![]() $|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

$|\overline f(x)-\overline g(x)|<1$

for all

![]() $x\in H_k\backslash U$

and

$x\in H_k\backslash U$

and

![]() $|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|>2p$

. Define

$|\alpha _y(\overline f)-\alpha _y(\overline g)|>2p$

. Define

![]() $\overline h\in E(H)$

as in the previous case and use the same arguments to complete the proof.

$\overline h\in E(H)$

as in the previous case and use the same arguments to complete the proof.

Since

![]() $Y_{p,q}^k$

are compact subsets of

$Y_{p,q}^k$

are compact subsets of

![]() $\overline Y$

, each

$\overline Y$

, each

![]() $M^k(p,q)$

is a countable union of compact subsets

$M^k(p,q)$

is a countable union of compact subsets

![]() $\{F_n^k(p,q):n=1,2,\ldots \}$

of

$\{F_n^k(p,q):n=1,2,\ldots \}$

of

![]() $\overline Y$

. So, by Claim 6,

$\overline Y$

. So, by Claim 6,

![]() $Y_k=\bigcup \{F_n^k(p,q):n,p,q=1,2,\ldots \}$

. According to Claim 7, all maps

$Y_k=\bigcup \{F_n^k(p,q):n,p,q=1,2,\ldots \}$

. According to Claim 7, all maps

![]() $\Phi _{kpq}^n=\Phi _{kpq}|F_n^k(p,q):F_n^k(p,q)\to [H_k]^q$

are continuous. Moreover, since

$\Phi _{kpq}^n=\Phi _{kpq}|F_n^k(p,q):F_n^k(p,q)\to [H_k]^q$

are continuous. Moreover, since

![]() $Y\subset \bigcup _kY_k$

,

$Y\subset \bigcup _kY_k$

,

![]() $Y\subset \bigcup \{F_n^k(p,q):n,p,q,k=1,2,\ldots \}$

.

$Y\subset \bigcup \{F_n^k(p,q):n,p,q,k=1,2,\ldots \}$

.

Claim 8 The fibers of

![]() $\Phi _{kpq}^n:F_n^k(p,q)\to [H_k]^q$

are finite.

$\Phi _{kpq}^n:F_n^k(p,q)\to [H_k]^q$

are finite.

We follow the arguments from the proof of [Reference Gorak, Krupski and Marciszewski6, Theorem 4.2]. Fix

![]() $z\in F_n^k(p,q)$

for some

$z\in F_n^k(p,q)$

for some

![]() $n,p,q, k$

and let

$n,p,q, k$

and let

![]() $A=\{y\in F_n^k(p,q):K_{kp}(y)=K_{kp}(z)\}$

. Since

$A=\{y\in F_n^k(p,q):K_{kp}(y)=K_{kp}(z)\}$

. Since

![]() $\Phi _{kpq}^n$

is a perfect map, A is compact. Suppose A is infinite, so it contains a convergent sequence

$\Phi _{kpq}^n$

is a perfect map, A is compact. Suppose A is infinite, so it contains a convergent sequence

![]() $S=\{y_m\}$

of distinct points. Because

$S=\{y_m\}$

of distinct points. Because

![]() $E(\overline Y)$

contains a

$E(\overline Y)$

contains a

![]() $QS$

-algebra

$QS$

-algebra

![]() $\Gamma $

on

$\Gamma $

on

![]() $\overline Y$

, for every

$\overline Y$

, for every

![]() $y_m$

there exist its neighborhood

$y_m$

there exist its neighborhood

![]() $U_m$

in

$U_m$

in

![]() $\overline Y$

and a function

$\overline Y$

and a function

![]() $\overline g_m\in \Gamma $

,

$\overline g_m\in \Gamma $

,

![]() $\overline g_m:\overline Y\to [0,2p]$

such that:

$\overline g_m:\overline Y\to [0,2p]$

such that:

![]() $U_m\cap S=\{y_m\}$

,

$U_m\cap S=\{y_m\}$

,

![]() $\overline g_m(y_m)=2p$

, and

$\overline g_m(y_m)=2p$

, and

![]() $\overline g_m(y)=0$

for all

$\overline g_m(y)=0$

for all

![]() $y\not \in U_m$

. Since

$y\not \in U_m$

. Since

![]() $\varphi $

is c-good, for each m, there is

$\varphi $

is c-good, for each m, there is

![]() $f_m\in E(X)$

with

$f_m\in E(X)$

with

![]() $\varphi (f_m)=\overline g_m|Y=g_m$

and

$\varphi (f_m)=\overline g_m|Y=g_m$

and

![]() $||f_m||\leq c||g_m||$

. So,

$||f_m||\leq c||g_m||$

. So,

![]() $||\overline f_m||\leq 2pc$

,

$||\overline f_m||\leq 2pc$

,

![]() $m=1,2,\ldots $

and the sequence

$m=1,2,\ldots $

and the sequence

![]() $\{\overline f_m\}$

is contained in the compact set

$\{\overline f_m\}$

is contained in the compact set

![]() $[-2pc,2pc]^{H}$

. Hence,

$[-2pc,2pc]^{H}$

. Hence,

![]() $\{\overline f_m\}$

has an accumulation point in

$\{\overline f_m\}$

has an accumulation point in

![]() $[-2pc,2pc]^{H}$

. This implies the existence of

$[-2pc,2pc]^{H}$

. This implies the existence of

![]() $i\neq j$

such that

$i\neq j$

such that

![]() $|\overline f_i(x)-\overline f_j(x)|<1$

for all

$|\overline f_i(x)-\overline f_j(x)|<1$

for all

![]() $x\in K_{kp}(z)$

. Consequently, since

$x\in K_{kp}(z)$

. Consequently, since

![]() $K_{kp}(y_j)=K_{kp}(z)$

,

$K_{kp}(y_j)=K_{kp}(z)$

,

![]() $|\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_j)-\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_i)|\leq p$

. On the other hand,

$|\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_j)-\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_i)|\leq p$

. On the other hand,

![]() $\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_j)=\overline {\varphi (f_j)}(y_j)=\overline g_j(y_j)=2p$

and

$\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_j)=\overline {\varphi (f_j)}(y_j)=\overline g_j(y_j)=2p$

and

![]() $\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_i)=\overline {\varphi (f_i)}(y_j)=\overline g_i(y_j)=0$

, so

$\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_i)=\overline {\varphi (f_i)}(y_j)=\overline g_i(y_j)=0$

, so

![]() $|\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_j)-\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_i)|=2p$

, a contradiction.

$|\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_j)-\alpha _{y_j}(\overline f_i)|=2p$

, a contradiction.

Now, we can complete the proof of Proposition 2.1. Suppose H has a property

![]() $\mathcal P$

satisfying conditions (a)–(c). Then so does

$\mathcal P$

satisfying conditions (a)–(c). Then so does

![]() $H_k^q$

for each

$H_k^q$

for each

![]() $k,q$

because

$k,q$

because

![]() $H_k^q$

is closed in

$H_k^q$

is closed in

![]() $H^q$

. We claim that the space

$H^q$

. We claim that the space

![]() $[H_k]^q$

also has the property

$[H_k]^q$

also has the property

![]() $\mathcal P$

. Indeed, let

$\mathcal P$

. Indeed, let

![]() $\mathcal C$

be a countable base of

$\mathcal C$

be a countable base of

![]() $H_k$

. For every q-tuple

$H_k$

. For every q-tuple

![]() $(U_1,\ldots ,U_q)$

of elements of

$(U_1,\ldots ,U_q)$

of elements of

![]() $\mathcal C$

with pairwise disjoint closures, the closed set

$\mathcal C$

with pairwise disjoint closures, the closed set

is homeomorphic to the closed subset

![]() $\overline U_1\times \cdots \times \overline U_q$

of

$\overline U_1\times \cdots \times \overline U_q$

of

![]() $H_k^q$

. Hence,

$H_k^q$

. Hence,

![]() $W(U_1,\ldots ,U_q)\in \mathcal P$

. Clearly, the space

$W(U_1,\ldots ,U_q)\in \mathcal P$

. Clearly, the space

![]() $[H_k]^q$

can be covered by countably many sets of the form

$[H_k]^q$

can be covered by countably many sets of the form

![]() $W(U_1,\ldots , U_q)$

, therefore, it belongs to

$W(U_1,\ldots , U_q)$

, therefore, it belongs to

![]() $\mathcal P$

. Finally, since the maps

$\mathcal P$

. Finally, since the maps

![]() $\Phi _{kpq}^n:F_n^k(p,q)\to [H_k]^q$

are perfect and have finite fibers, each

$\Phi _{kpq}^n:F_n^k(p,q)\to [H_k]^q$

are perfect and have finite fibers, each

![]() $F_n^k(p,q)$

has the property

$F_n^k(p,q)$

has the property

![]() $\mathcal P$

. Therefore, by condition (b),

$\mathcal P$

. Therefore, by condition (b),

![]() $Y_\infty =\bigcup \{F_n^k(p,q):n,p,q,k=1,2,\ldots \}$

has the property

$Y_\infty =\bigcup \{F_n^k(p,q):n,p,q,k=1,2,\ldots \}$

has the property

![]() $\mathcal P$

.

$\mathcal P$

.

It remains to show that all powers of

![]() $Y_\infty $

also have the property

$Y_\infty $

also have the property

![]() $\mathcal P$

. Simplifying the notations, we observed that

$\mathcal P$

. Simplifying the notations, we observed that

![]() $Y_\infty =\bigcup _{m=1}^\infty F_m$

, where every

$Y_\infty =\bigcup _{m=1}^\infty F_m$

, where every

![]() $F_m$

is a compact set admitting a map

$F_m$

is a compact set admitting a map

![]() $\Phi _m$

with finite fibers onto a compact subset of

$\Phi _m$

with finite fibers onto a compact subset of

![]() $H^m$

. Then, for every k, we have

$H^m$

. Then, for every k, we have

Consequently,

![]() $\prod _{i=1}^k\Phi _{m_i}:\prod _{i=1}^kF_{m_i}\to H^{m_1+m_2+\cdots +m_k}$

is a map which fibers are products of k-many finite sets. Hence, the fibers of

$\prod _{i=1}^k\Phi _{m_i}:\prod _{i=1}^kF_{m_i}\to H^{m_1+m_2+\cdots +m_k}$

is a map which fibers are products of k-many finite sets. Hence, the fibers of

![]() $\prod _{i=1}^k\Phi _{m_i}$

are finite. Because

$\prod _{i=1}^k\Phi _{m_i}$

are finite. Because

![]() $H^{m_1+m_2+\cdots +m_k}\in \mathcal P$

, so is

$H^{m_1+m_2+\cdots +m_k}\in \mathcal P$

, so is

![]() $\prod _{i=1}^kF_{m_i}$

. Finally, by property

$\prod _{i=1}^kF_{m_i}$

. Finally, by property

![]() $(b)$

,

$(b)$

,

![]() $Y_\infty ^k\in \mathcal P$

.

$Y_\infty ^k\in \mathcal P$

.

All definitions below, except that one of

![]() $(m-C)$

-spaces, can be found in [Reference Engelking2]. A normal space X is called strongly countable-dimensional if X can be represented as a countable union of closed finite-dimensional subspaces. Recall that a normal space X is weakly infinite-dimensional if for every sequence

$(m-C)$

-spaces, can be found in [Reference Engelking2]. A normal space X is called strongly countable-dimensional if X can be represented as a countable union of closed finite-dimensional subspaces. Recall that a normal space X is weakly infinite-dimensional if for every sequence

![]() $\{(A_i,B_i)\}$

of pairs of disjoint closed subsets of X there exist closed sets

$\{(A_i,B_i)\}$

of pairs of disjoint closed subsets of X there exist closed sets

![]() $L_1,L_2,\ldots $

such that

$L_1,L_2,\ldots $

such that

![]() $L_i$

is a partition between

$L_i$

is a partition between

![]() $A_i$

and

$A_i$

and

![]() $B_i$

and

$B_i$

and

![]() $\bigcap _iL_i=\varnothing $

. A normal space X is a C-space if for every sequence

$\bigcap _iL_i=\varnothing $

. A normal space X is a C-space if for every sequence

![]() $\{\mathcal G_i\}$

of open covers of X there exists a sequence

$\{\mathcal G_i\}$

of open covers of X there exists a sequence

![]() $\{\mathcal H_i\}$

of families of pairwise disjoint open subsets of X such that for

$\{\mathcal H_i\}$

of families of pairwise disjoint open subsets of X such that for

![]() $i=1,2,\ldots $

each member of

$i=1,2,\ldots $

each member of

![]() $\mathcal H_i$

is contained in a member of

$\mathcal H_i$

is contained in a member of

![]() $\mathcal G_i$

and the union

$\mathcal G_i$

and the union

![]() $\bigcup _i\mathcal H_i$

is a cover of X. The

$\bigcup _i\mathcal H_i$

is a cover of X. The

![]() $(m-C)$

-spaces, where

$(m-C)$

-spaces, where

![]() $m\geq 2$

is a natural number, were introduced by Fedorchuk [Reference Fedorchuk4]: A normal space X is an

$m\geq 2$

is a natural number, were introduced by Fedorchuk [Reference Fedorchuk4]: A normal space X is an

![]() $(m-C)$

-space if for any sequence

$(m-C)$

-space if for any sequence

![]() $\{\mathcal G_i\}$

of open covers of X such that each

$\{\mathcal G_i\}$

of open covers of X such that each

![]() $\mathcal G_i$

consists of at most m elements, there is a sequence of disjoint open families

$\mathcal G_i$

consists of at most m elements, there is a sequence of disjoint open families

![]() $\{\mathcal H_i\}$

such that each

$\{\mathcal H_i\}$

such that each

![]() $\mathcal H_i$

refines

$\mathcal H_i$

refines

![]() $\mathcal G_i$

and

$\mathcal G_i$

and

![]() $\bigcup _i\mathcal H_i$

is a cover of X. The

$\bigcup _i\mathcal H_i$

is a cover of X. The

![]() $(2-C)$

-spaces are exactly the weakly infinite-dimensional spaces and for every m we have the inclusion

$(2-C)$

-spaces are exactly the weakly infinite-dimensional spaces and for every m we have the inclusion

![]() $(m+1)-C\subset m-C$

. Moreover, every C-space is

$(m+1)-C\subset m-C$

. Moreover, every C-space is

![]() $m-C$

for all m.

$m-C$

for all m.

It is well known that the class of metrizable strongly countable-dimensional spaces contains all finite-dimensional metrizable spaces and is contained in the class of metrizable C-spaces. The last inclusion follows from the following two facts: (i) every finite-dimensional paracompact space is a C-space [Reference Engelking2, Theorem 6.3.7] and (ii) every paracompact space which is a countable union of its closed C-spaces is also a C-space [Reference Gutev and Valov8, Theorem 4.1]. Moreover, every C-space is weakly infinite-dimensional [Reference Engelking2, Theorem 6.3.10].

In the class of

![]() $\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces, the zero-dimensionality satisfies all conditions (a)–(c), see Theorems 1.5.16, 1.2.2, and 1.12.4 from [Reference Engelking2]. The strong countable-dimensionality also satisfies all these conditions, condition (c) follows easily from [Reference Engelking2, Theorem 1.12.4]. For C-space, this follows from mentioned above fact that a countable union of closed compact C-spaces is a C-space [Reference Gutev and Valov8, Theorem 4.1] and the following results of Hattori–Yamada [Reference Hattori and Yamada9]: the class of compact C-spaces is closed under finite products any perfect preimage of a C-space with C-space fibers is a C-space. Finally, if a

$\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces, the zero-dimensionality satisfies all conditions (a)–(c), see Theorems 1.5.16, 1.2.2, and 1.12.4 from [Reference Engelking2]. The strong countable-dimensionality also satisfies all these conditions, condition (c) follows easily from [Reference Engelking2, Theorem 1.12.4]. For C-space, this follows from mentioned above fact that a countable union of closed compact C-spaces is a C-space [Reference Gutev and Valov8, Theorem 4.1] and the following results of Hattori–Yamada [Reference Hattori and Yamada9]: the class of compact C-spaces is closed under finite products any perfect preimage of a C-space with C-space fibers is a C-space. Finally, if a

![]() $\sigma $

-compact space X is weakly infinite-dimensional, then obviously every closed subset of X, as well as any countable union of closed subsets of X have the same property (see [Reference Engelking2, Theorem 6.1.6]). Condition (c) follows from the following result of Pol [Reference Pol19, Theorem 4.1]: If

$\sigma $

-compact space X is weakly infinite-dimensional, then obviously every closed subset of X, as well as any countable union of closed subsets of X have the same property (see [Reference Engelking2, Theorem 6.1.6]). Condition (c) follows from the following result of Pol [Reference Pol19, Theorem 4.1]: If

![]() $f:X\to Y$

is a continuous map between compact metrizable spaces such that Y is weakly infinite-dimensional and each fiber

$f:X\to Y$

is a continuous map between compact metrizable spaces such that Y is weakly infinite-dimensional and each fiber

![]() $f^{-1}(y)$

,

$f^{-1}(y)$

,

![]() $y\in Y$

, is at most countable, then X is weakly infinite-dimensional. The validity of conditions (a)–(c) for

$y\in Y$

, is at most countable, then X is weakly infinite-dimensional. The validity of conditions (a)–(c) for

![]() $(m-C)$

-spaces in the class of

$(m-C)$

-spaces in the class of

![]() $\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces follows from the following results [Reference Fedorchuk4]: The

$\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces follows from the following results [Reference Fedorchuk4]: The

![]() $(m-C)$

-space property is hereditary with respect to closed subsets, a countable union of closed

$(m-C)$

-space property is hereditary with respect to closed subsets, a countable union of closed

![]() $(m-C)$

-spaces is also

$(m-C)$

-spaces is also

![]() $m-C$

. Moreover, for

$m-C$

. Moreover, for

![]() $(m-C)$

-spaces, Krupski [Reference Krupski11, Lemma 4.5] established an analog of the cited above Pol’s result. Therefore, condition (c) holds for the property

$(m-C)$

-spaces, Krupski [Reference Krupski11, Lemma 4.5] established an analog of the cited above Pol’s result. Therefore, condition (c) holds for the property

![]() $m-C$

in the class of

$m-C$

in the class of

![]() $\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces.

$\sigma $

-compact metrizable spaces.

3 Uniformly continuous surjections

In this section, we prove Theorems 1.1 and 1.3.

For every space X, let

![]() $\mathcal F_X$

be the class of all maps from X onto second countable spaces. For any two maps

$\mathcal F_X$

be the class of all maps from X onto second countable spaces. For any two maps

![]() $h_1,h_2\in \mathcal F_X$

, we write

$h_1,h_2\in \mathcal F_X$

, we write

![]() $h_1\succ h_2$

if there exists a continuous map

$h_1\succ h_2$

if there exists a continuous map

![]() $\theta :h_1(X)\to h_2(X)$

with

$\theta :h_1(X)\to h_2(X)$

with

![]() $h_2=\theta \circ h_1$

. If

$h_2=\theta \circ h_1$

. If

![]() $\Phi \subset C(X)$

, we denote by

$\Phi \subset C(X)$

, we denote by

![]() $\triangle \Phi $

the diagonal product of all

$\triangle \Phi $

the diagonal product of all

![]() $f\in \Phi $

. Clearly,

$f\in \Phi $

. Clearly,

![]() $(\triangle \Phi )(X)$

is a subspace of the product

$(\triangle \Phi )(X)$

is a subspace of the product

![]() $\prod \{\mathbb R_f:f\in \Phi \}$

, and let

$\prod \{\mathbb R_f:f\in \Phi \}$

, and let

![]() $\pi _f:(\triangle \Phi )(X)\to \mathbb R_f$

be the projection. Following [Reference Gul’ko7], we call a set

$\pi _f:(\triangle \Phi )(X)\to \mathbb R_f$

be the projection. Following [Reference Gul’ko7], we call a set

![]() $\Phi \subset C(X)$

admissible if the family

$\Phi \subset C(X)$

admissible if the family

![]() $\pi (\Phi )=\{\pi _f:f\in \Phi \}$

is a

$\pi (\Phi )=\{\pi _f:f\in \Phi \}$

is a

![]() $QS$

-algebra on

$QS$

-algebra on

![]() $(\triangle \Phi )(X)$

. We are using the following facts:

$(\triangle \Phi )(X)$

. We are using the following facts:

-

(3.1)

$\dim X\leq n$

if and only if for every

$\dim X\leq n$

if and only if for every

$h\in \mathcal F_X$

, there exists a

$h\in \mathcal F_X$

, there exists a

$h_0\in \mathcal F_X$

such that

$h_0\in \mathcal F_X$

such that

$\dim h_0(X)\leq n$

and

$\dim h_0(X)\leq n$

and

$h_0\succ h$

[Reference Pestov18].

$h_0\succ h$

[Reference Pestov18]. -

(3.2) If

$\dim X\leq n$

and

$\dim X\leq n$

and

$\Phi \subset C(X)$

is countable, then there exists a countable set

$\Phi \subset C(X)$

is countable, then there exists a countable set

${\Theta \subset C(X)}$

containing

${\Theta \subset C(X)}$

containing

$\Phi $

with

$\Phi $

with

$\dim (\triangle \Theta )(X)\leq n$

. Moreover, it follows from the proof of [Reference Gul’ko7, Lemma 2.2] that we can choose

$\dim (\triangle \Theta )(X)\leq n$

. Moreover, it follows from the proof of [Reference Gul’ko7, Lemma 2.2] that we can choose

$\Theta \subset C^*(X)$

provided that

$\Theta \subset C^*(X)$

provided that

$\Phi \subset C^*(X)$

.

$\Phi \subset C^*(X)$

. -

(3.3) For every countable

$\Phi '\subset C(X)$

, there is a countable admissible set

$\Phi '\subset C(X)$

, there is a countable admissible set

$\Phi $

containing

$\Phi $

containing

$\Phi '$

such that

$\Phi '$

such that

$(\triangle \Phi )(X)$

is homeomorphic to

$(\triangle \Phi )(X)$

is homeomorphic to

$(\triangle \Phi ')(X)$

. According to the proof of [Reference Gul’ko7, Lemma 2.4],

$(\triangle \Phi ')(X)$

. According to the proof of [Reference Gul’ko7, Lemma 2.4],

$\Phi $

could be taken to be a subset of

$\Phi $

could be taken to be a subset of

$C^*(X)$

if

$C^*(X)$

if

$\Phi '\subset C^*(X)$

. Moreover, we can assume that

$\Phi '\subset C^*(X)$

. Moreover, we can assume that

$\Phi '$

satisfies condition (2.3), so

$\Phi '$

satisfies condition (2.3), so

$\pi (\Phi )$

also satisfies that condition.

$\pi (\Phi )$

also satisfies that condition. -

(3.4) If

$\{\Psi _n\}$

is an increasing sequence of admissible subsets of

$\{\Psi _n\}$

is an increasing sequence of admissible subsets of

$C(X)$

, then

$C(X)$

, then

${\Psi =\bigcup _n\Psi _n}$

is also admissible (see [Reference Gul’ko7, Lemma 2.5]).

${\Psi =\bigcup _n\Psi _n}$

is also admissible (see [Reference Gul’ko7, Lemma 2.5]).

We also need the following lemmas.

Lemma 3.1 Let X be a zero-dimensional separable metrizable space and

![]() $E(X)$

be a countable subfamily of

$E(X)$

be a countable subfamily of

![]() $C^*(X)$

. Then, there exists a metrizable zero-dimensional compactification

$C^*(X)$

. Then, there exists a metrizable zero-dimensional compactification

![]() $\overline X$

of X such that each

$\overline X$

of X such that each

![]() $f\in E(X)$

can be extended over

$f\in E(X)$