Introduction

In times of crisis, the public gathers behind the current political leadership. This ‘rally effect’, which entered the political science vocabulary in the early 1970s (Mueller, Reference Mueller1970), is a persistent empirical regularity that is well-documented in numerous studies. Although originally developed with respect to the US presidency, research demonstrates that the effect generalizes beyond the United States (e.g., Dinesen & Jæger, Reference Dinesen and Jæger2013). Moreover, it does not only manifest in the context of intergroup conflicts such as wars or terrorist attacks (e.g., Edwards & Swenson, Reference Edwards and Swenson1997) but also in the aftermath of natural disasters (e.g., Boittin et al., Reference Boittin, Mo and Utych2020) or public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Yam et al., Reference Yam, Jackson, Barnes, Lau, Qin and Lee2020). Despite its persistence, generality and law-like character, we lack fine-grained knowledge on how cognitive and emotional mechanisms interplay to bring about rally effects in times of crisis (see also Hegewald & Schraff, Reference Hegewald and Schraff2022; Hintson & Vaishnav, Reference Hintson and Vaishnav2023).

It is crucial to generate insights into the underlying causal mechanisms, as the rally effect can have dramatic repercussions on policy outcomes in democracies. In cases where a crisis occurs during an election campaign, the rally effect can strongly influence election results (Leininger & Schaub, Reference Leininger and Schaub2023) and with it the central mechanism of granting democratic authority to rule. Almost more importantly, the observation of rally effects is often accompanied by increasing support for policies restricting civil and political liberties like pandemic lockdowns (in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, see Alsan et al., Reference Alsan, Braghieri, Eichmeyer, Kim, Stantcheva and Yang2023) or the US Patriot Act (in the context of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, see Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Khatib and Capelos2002; Huddy & Feldman, Reference Huddy and Feldman2011). As citizens are more willing to sacrifice freedom for security in the context of rally effects, it can become easier for governments to implement policies limiting fundamental rights (Page & Shapiro, Reference Page and Shapiro1983). This is all the more true because the opposition is typically reluctant to criticize the political leadership in times of crisis (Hetherington & Nelson, Reference Hetherington and Nelson2003). Moreover, after the crisis has been overcome and the rally effect has worn off, there is a risk that rights might not be regranted in full – especially in illiberal democracies.

In contrast to the literature's previous approaches regarding the underlying causal mechanisms, we are the first to argue that the rally effect is composed of two distinct and counteracting psychological mechanisms: a perceived threat mechanism as well as an anxiety mechanism. The literature has already shown that perceived threat and anxiety are different concepts (e.g., Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005; Miller, Reference Miller2000) that have different effects across many domains (e.g., Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Krosnick, Holbrook, Tahk, Dionne, Krosnick, Chiang and Stark2016). Perceived threat is the subjectively estimated risk posed by a crisis and thus a predominantly cognitive reaction to an external threat. Anxiety is a negative emotional response to a crisis and therefore a predominantly affective reaction to an external threat. We argue that considering the interplay between both effects is imperative to understanding the rally effect as they have very different substantive implications. Perceived threat should boost support for political leaders, in part because it triggers system-justifying reactions. On the contrary, anxiety should undermine support for the political leader by producing an assimilation effect by which the negative affective state of anxiety negatively colours the evaluation of the leader.

It is already known that both perceived threat and anxiety have distinct effects on the support of counter-terrorism policies in the aftermath of terrorist attacks. Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005) argue that individuals who perceive high levels of threat should be more supportive of hawkish military action, since perceived threat leads to demand for retaliation and elimination of the aggressor. On the contrary, they claim that individuals who exhibit high levels of anxiety should be less inclined to support aggressive (and potentially risky) military action, as anxiety leads to greater risk aversion (see also Huddy & Feldman, Reference Huddy and Feldman2011, for a discussion on the effect of perceived threat and anxiety in the context of terrorist attacks). Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005) provide evidence for these arguments employing a survey fielded in the United States after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Unlike previous research, we argue that perceived threat and anxiety should affect support for political leaders not only the support for specific policies or trust in the government, and that this should be observed in all types of crisis situations. Additionally, we argue that this effect is of direct nature and not, as, for instance, argued by Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005), necessarily mediated by government action. While the perceived threat mechanism has recently become well known in the literature on the rally effect (Feinstein, Reference Feinstein2018; Kritzinger et al., Reference Kritzinger, Foucault, Lachat, Partheymüller, Plescia and Brouard2021), the hypothesized anxiety mechanism is so far not established. It is well known that anxiety leads to risk aversion and, thus support for cautious government action in times of crisis (e.g., Erhardt et al., Reference Erhardt, Freitag, Filsinger and Wamsler2021; Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Schott and Scherer2011), but the effect of anxiety on political leadership support, however, remains rather unclear. In fact, we are the first to argue that anxiety directly shapes the rally effect via an assimilation effect. This assimilation effect should reduce support for the political leader – regardless of whether the government's response to the crisis is cautious or risky.Footnote 1

We provide robust evidence for the hypothesized anxiety and perceived threat mechanisms. First, we rely on panel data based on more than 32,000 interviews from the early COVID-19 pandemic in Germany to trace the causal mechanisms. The findings show that both mechanisms operate as theorized. Second, we demonstrate that the mechanisms are not only at work when citizens evaluate their heads of government, yet also when they rate ministers who manage key crisis portfolios.

Our findings have important theoretical implications as we challenge the view that crises automatically lead to an increase in approval of the political leader. This way, we inform the debate on the individual-level characteristics that lead citizens to change their evaluation of political leaders in times of crisis. While existing research shows that the rally effect is shaped by the emotion of anger (Small et al., Reference Small, Lerner and Fischhoff2006), pre-crisis support for the leader (Edwards & Swenson, Reference Edwards and Swenson1997; Malhotra & Kuo, Reference Malhotra and Kuo2008), political information (Sirin, Reference Sirin2011) or exposure to the crisis (Hintson & Vaishnav, Reference Hintson and Vaishnav2023), we suggest a novel duality of psychological mechanisms and provide robust empirical evidence that they are in fact at play. Consequently, our findings help to understand how the rally effect comes about.

Leadership approval as a function of two distinct mechanisms

In times of crisis, we can observe that citizens tend to increase their approval of the incumbent government and its leader. An extant literature has identified different mechanisms underlying the rally effect. For instance, one argument proposes that rally effects are rooted in increased in-group loyalty (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Jost and Sidanius2004) following external threats, that is emphasized patriotic feelings. Consequently, people support their government to increase their nation's chance of overcoming the crisis (Chowanietz, Reference Chowanietz2011; Mueller, Reference Mueller1970; Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Stewart and Curran2002). Another strand of the literature suggests that the government's information-monopoly combined with a lack of criticism by the opposition in times of severe crises renders the government as opinion leader, consequently boosting leadership approval (Brody & Shapiro, Reference Brody and Shapiro1989; Brody, Reference Brody1991; W. D. Baker & Oneal, Reference Baker and Oneal2001; Chowanietz, Reference Chowanietz2011; Groeling & Baum, Reference Groeling and Baum2008; Lee, Reference Lee1977).

We argue that the rally effect is composed of two distinct mechanisms because such crises induce two responses among citizens: perceived threat – a cognitive response to the crisis – and anxiety – an emotional response. Moreover, we expect that the perceived threat mechanism and the anxiety mechanism are counteracting with regard to leadership approval. While threatened citizens should tend to approve, anxious citizens should tend to disapprove of their political leaders.

Perceived threat and anxiety are different concepts. The distinction is based on the conceptual separation of cognitive and affective reactions to an external threat (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005; Huddy & Feldman, Reference Huddy and Feldman2011; Miller, Reference Miller2000; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Krosnick, Holbrook, Tahk, Dionne, Krosnick, Chiang and Stark2016). Perceived threat is defined as a predominantly cognitive response: the subjectively calculated risk posed by a crisis. For example, regarding a terrorist threat, the level of perceived threat depends on the estimated risk of becoming a victim of a terrorist attack, whereas concerning a pandemic it is governed by the estimated risk of becoming infected. Anxiety, however, is defined as a predominantly affective response: a negative emotional reaction to a crisis, such as terrorist threats or a pandemic. Although conceptually clearly distinct, perceived threat and anxious arousal naturally correlate (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005; Miller, Reference Miller2000).Footnote 2

Existing empirical evidence reveals that perceived threat and anxiety have different effects, confirming the distinctness of both responses. Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005) have shown that perceived threat and anxiety have different repercussions in many domains: First, anxiety promotes risk avoidance (see also Lerner & Keltner, Reference Lerner and Keltner2001), while on the contrary, perceived threat fosters support for potentially risky and dangerous actions to eliminate the threat. Second, anxiety inhibits performance on cognitively demanding tasks (see also Maloney et al., Reference Maloney, Sattizahn and Beilock2014), such as political knowledge, while perceived threat has no such effect. Third, anxiety is associated with symptoms of depression (see also Clark & Watson, Reference Clark and Watson1991), such as sleep disorders, while this is not the case for perceived threat. In addition, there is evidence of differential effects on political attitudes. Information about the costs of immigration shape attitudes toward immigrants – not because of changes in perceived threat, but because of changes in anxiety (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008). An imminent policy change in an undesired direction fosters political activism – not because of changes in anxiety but because of changes in perceived threat (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Krosnick, Holbrook, Tahk, Dionne, Krosnick, Chiang and Stark2016).

Perceived threat mechanism

Perceived threat is the perceived risk posed by a crisis (cognitive Footnote 3 response to a crisis), and we argue that it is one driver of the rally effect. A number of theoretical arguments expect an increase in perceived threat to boost support for political leaders in times of crises. The first originates from what is known as the opinion leadership school of research on the rally effect (Baekgaard et al., Reference Baekgaard, Christensen, Madsen and Mikkelsen2020, p. 3). The argument builds on the notion that, when evaluating political leaders, an increase in perceived threat enhances the salience of considerations related to the crisis while it reduces the salience of other relevant issues. As opinion leaders from opposition parties typically refrain from criticizing the leader's crisis management in the wake of a threat, individuals are mostly exposed to public comments supportive of the leader with respect to the salient considerations (Brody & Shapiro, Reference Brody and Shapiro1989; Hetherington & Nelson, Reference Hetherington and Nelson2003, pp. 37–39). Hence, the evaluation of political leaders should improve as perceived threat increases. Somewhat consistent with this argument, Schraff (Reference Schraff2021) found in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic that considerations like economic evaluations become less important determinants of political trust as COVID-19 infection numbers increase.

System justification theory provides us with another argument (Jost & Banaji, Reference Jost and Banaji1994). This theory states that people show a tendency to defend and justify the political, economic or social system (even if it is contrary to self-interest). Times of crisis should amplify these tendencies since exposure to ‘threat can increase system-justifying responses in a variety of ways’ (Jost, Reference Jost2019, p. 267) in order to reduce feelings of uncertainty. Empirical evidence shows support for the notion that perceived dependence on a system is positively related to perceived legitimacy of the system's authorities. In fact, experimental evidence indicates that feelings of political powerlessness result in greater legitimization of governmental authorities (van der Toorn et al., Reference van der Toorn, Feinberg, Jost, Kay, Tyler, Willer and Wilmuth2015, Study 5, pp. 104–106).

Moreover, Gelfand et al. (Reference Gelfand, Raver, Nishii, Leslie, Lun, Lim, Duan, Almaliach, Ang, Arnadottir, Aycan, Boehnke, Boski, Cabecinhas, Chan, Chhokar, D'Amato, Ferrer, Fischlmayr, Fischer, Fülöp, Georgas, Kashima, Kashima, Kim, Lempereur, Marquez, Othman, Overlaet, Panagiotopoulou, Peltzer, Perez‐Florizno, Ponomarenko, Realo, Schei, Schmitt, Smith, Soomro, Szabo, Taveesin, Toyama, Van De Vliert, Vohra, Ward and Yamaguchi2011) formulated a cultural evolutionary theory according to which nations that are exposed to threats need strong social coordination in order to survive. This would lead to strong social norms and a low tolerance of deviant behaviour and could perhaps also lead to greater support for political leaders. Gelfand et al. (Reference Gelfand, Raver, Nishii, Leslie, Lun, Lim, Duan, Almaliach, Ang, Arnadottir, Aycan, Boehnke, Boski, Cabecinhas, Chan, Chhokar, D'Amato, Ferrer, Fischlmayr, Fischer, Fülöp, Georgas, Kashima, Kashima, Kim, Lempereur, Marquez, Othman, Overlaet, Panagiotopoulou, Peltzer, Perez‐Florizno, Ponomarenko, Realo, Schei, Schmitt, Smith, Soomro, Szabo, Taveesin, Toyama, Van De Vliert, Vohra, Ward and Yamaguchi2011) show that nations which historically experienced great environmental threats (e.g., natural disasters) and health-related threats (e.g., prevalence of pathogens) have stronger social norms than those nations that encountered these threats to a lesser extent.

There is also empirical evidence supportive of these arguments claiming that perceived threat drives the rally effect. Analysing the public reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic in Austria using a panel data design, Kritzinger et al. (Reference Kritzinger, Foucault, Lachat, Partheymüller, Plescia and Brouard2021) show that perceived threat to public health increased trust in the Austrian government.

Based on this review of the literature, we expect an increase in perceived threat during times of crisis to boost support for the political leader. Note that all of the arguments above expect that an increase in perceived threat boosts support for political leaders – independent of enacted policies and the leader's crisis management. This is broadly consistent with the findings of Schraff (Reference Schraff2021, p. 9), suggesting that the increase in political trust during the COVID-19 pandemic ‘is driven by the pandemic intensity of the crisis and not [by] the specific government measures’ like lockdowns. However, it is conceivable that the leader's performance and emergency responses affect the perceptions of threat. For instance, the imposition of a pandemic lockdown likely reduces the perceived threat originating from the spread of a virus. This way, government measures could indirectly influence support for the leader.

Anxiety mechanism

In addition to the perceived threat mechanism that is likely to increase the approval of political leaders, we propose that the rally effect is driven by another mechanism – the anxiety mechanism – that disadvantages political leaders. Anxiety is a negative emotional response to a crisis (affective response to a crisis). We argue that if times of crisis induce anxiety among citizens, then they will be less likely to support their political leaders.

Times of crisis typically induce anxious arousal. In the context of terrorist attacks, the physical proximity to the 9/11 attacks fuelled anxieties (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005). We also know that the COVID-19 pandemic induced higher levels of anxiety, based on cumulating evidence obtained in countries such as the United States (Tabri et al., Reference Tabri, Hollingshead and Wohl2020), Canada (Robillard et al., Reference Robillard, Dion, Pennestri, Solomonova, Lee, Saad, Murkar, Godbout, Edwards, Quilty, Daros, Bhatla and Kendzerska2020), Austria (Pieh et al., Reference Pieh, Budimir and Probst2020), China (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, Ho and Ho2020), Italy (Mazza et al., Reference Mazza, Ricci, Biondi, Colasanti, Ferracuti, Napoli and Roma2020) or Spain (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., Reference Ozamiz‐Etxebarria, Dosil‐Santamaria, Picaza‐Gorrochategui and Idoiaga‐Mondragon2020). Research suggests that not only health-related considerations but also economic concerns fuelled anxieties during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fetzer et al., Reference Fetzer, Hensel, Hermle and Roth2021).

What are the consequences of increasing levels of anxiety during times of crisis on support for political leaders? A number of psychological theories claim the existence of an assimilation effect according to which an adverse affective state, such as anxiety, negatively influences the evaluation of (political) objects, such as political leaders. The affective contagion hypothesis originating from a motivated political reasoning argues that the process of making a political evaluation is shaped by the feelings that were evoked at the beginning of this process (Erisen et al., Reference Erisen, Lodge and Taber2014). These feelings bias the kind of considerations that enter the evaluation process: positive feelings tend to induce positively charged considerations while negative feelings arouse negatively charged considerations. Similarly, according to the affect infusion hypothesis, negative affect can serve as a heuristic cue when making a (political) evaluation of an object (Forgas, Reference Forgas1995). This way, the evaluation is negatively coloured – even if the origin of the affect is unrelated to the object. Compliant with the affect-as-information hypothesis, assimilation effects can occur if individuals are not aware of the source of their affective state (Schwarz & Clore, Reference Schwarz and Clore1983). In these cases, feelings may be misattributed to an unrelated object inducing a more negative evaluation of that particular object. In similar fashion, the affect transfer hypothesis (Ladd & Lenz, Reference Ladd and Lenz2008, Reference Ladd and Lenz2011) expects emotional reactions to political candidates to directly shape the evaluations of those candidates: ‘[I]f someone makes you feel anxious, you like him or her less; if someone makes you feel enthusiastic, you like him or her more’ (Ladd & Lenz, Reference Ladd and Lenz2008, p. 276).

Based on this line of literature, we hypothesize that the specific phenomenon under consideration, the rally effect, is governed by such an assimilation effect: anxieties induced by situations of crisis should negatively influence support for political leaders. Referring to the affective contagion hypothesis above, anxious arousal should emphasize negative thoughts concerning the leader, such as problems related to the management of the crisis. Also, the affect infusion, affect-as-information and affect transfer hypotheses suggest anxiety to negatively affect the evaluation of the leader, especially because individuals might not be able to precisely localize the origin of their anxious arousal in turbulent times of crisis.Footnote 4

We also argue that increased information seeking, as expected by affective intelligence theory (Marcus & MacKuen, Reference Marcus and MacKuen1993; Marcus, Reference Marcus1988; Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000), can go hand in hand with anxiety's assimilation effect. A plethora of existing studies on the effects of anxiety indicate that anxious arousal promotes information seeking (Albertson & Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015; Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Hutchings, Banks and Davis2008) and a more thorough information processing (Albertson & Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015; Mehlhaff et al., Reference Mehlhaff, Ryan, Hetherington and MacKuen2024). According to affective intelligence theory (Marcus & MacKuen, Reference Marcus and MacKuen1993; Marcus, Reference Marcus1988; Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000), this is induced by anxious individuals' aim at reducing uncertainty. Intuitively, this might contradict the mechanism of anxiety and associated emotional arousal driving people to perform below their cognitive abilities (Maloney et al., Reference Maloney, Sattizahn and Beilock2014). However, we argue that anxious arousal has, in line with the affective contagion and affect infusion hypotheses, the effect of negatively tainting such gathered information; high quantity and depth of consumed information do not avoid or erase it being negatively tainted by anxious arousal. Thus, it is likely that anxious individuals have more negative stances towards the government and political leaders, even if they held more detailed knowledge of the crisis and related government action. Existing studies provide support for this mechanism: Civettini and Redlawsk (Reference Civettini and Redlawsk2009) find that even under increased information-seeking efforts, high anxiety levels inhibit the learning process associated with gathering information. Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005) find that after 9/11, individuals who were most anxious about terrorism claimed to be most attentive to politics while at the same time retaining less factual information than their non-anxious counterparts. Similarly, the anxious tend to seek predominantly threatening information (Gadarian & Albertson, Reference Gadarian and Albertson2014) which may reinforce anxious arousal and increase the likelihood of evaluating political leaders through a negative lens. This likely decreases leadership approval, especially among the anxious.

From an empirical point of view, anxiety effects were predominantly assessed employing slightly different items than used in our study. The majority of studies, especially those finding positive effects of anxiety on political support (Baekgaard et al., Reference Baekgaard, Christensen, Madsen and Mikkelsen2020; Dietz et al., Reference Dietz, Roßteutscher, Scherer and Stövsand2023; Eggers & Harding, Reference Eggers and Harding2022; Erhardt et al., Reference Erhardt, Freitag, Filsinger and Wamsler2021; van der Meer et al., Reference van der Meer, Steenvoorden and Ouattara2023; Vasilopoulos et al., Reference Vasilopoulos, McAvay, Brouard and Foucault2023), subsume anxiety by the two concepts we divide into perceived threat and anxiety.Footnote 5 Thus, their isolated positive effects of anxiety on leadership approval may mask the negative effect anxious arousal may impose if disentangled from the cognitive mechanisms of threat perception. Our study, therefore, provides a more fine-grained assessment of the underlying cognitive and emotional effects of crises on leadership approval.

Note also that the survey fielded by Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005) in the United States in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks found anxiety to be negatively related to support for president George W. Bush, which is in line with our expectations. However, Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005) attributed this finding to anxious individuals' reluctance to support the potentially risky military response to the 9/11 attacks promoted by Bush. The same is true for the study of Erhardt et al. (Reference Erhardt, Freitag, Filsinger and Wamsler2021), which attributes an observed effect of anxiety on trust in the Swiss government to the risk aversion of anxious people. We, in turn, expect that the effect of anxiety is more general and should be found also when there is no risky government response to a crisis. In fact, the empirical analysis employs a case in which government response was not risky, but greatly cautious (the COVID-19 pandemic), that is, a case for which our theory has different expectations than the theory of Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005).

To sum up, our expectation regarding the effects of the anxiety mechanisms to bring about the rally effect is, thus, opposite to the expectation regarding the perceived threat mechanisms we discussed previously.

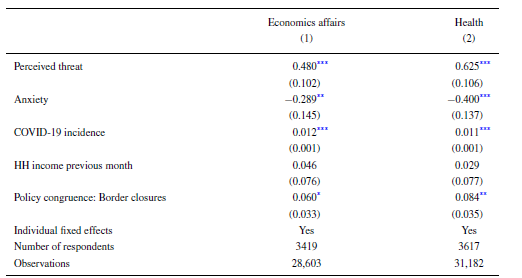

Research design

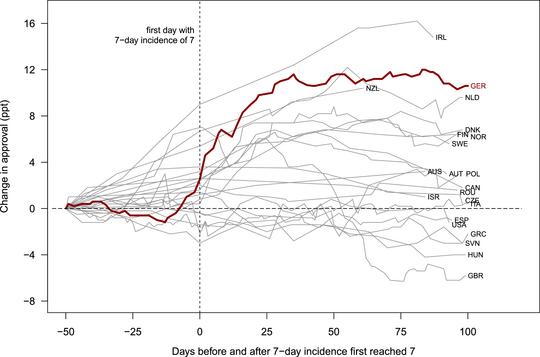

We test the hypotheses that perceived threat and anxiety have opposed effects on leadership approval in times of crises with data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, a public health crisis. As Figure 1 indicates, citizens approval of leaders' parties increased substantially when the pandemic first hit their respective countries.Footnote 6 In fact, there is cumulating evidence indicating that the COVID-19 pandemic boosted leadership approval. At the outset of the pandemic, COVID-19 infection numbers were positively associated with approval for the political leader (Yam et al., Reference Yam, Jackson, Barnes, Lau, Qin and Lee2020), trust in the government (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Sohlberg, Ghersetti and Johansson2021), trust in the national parliament (Hegewald & Schraff, Reference Hegewald and Schraff2022; Schraff, Reference Schraff2021), and incumbent's vote shares in elections (Leininger & Schaub, Reference Leininger and Schaub2023). Other studies revealed that the imposition of pandemic lockdowns boosted trust in the political leader (Baekgaard et al., Reference Baekgaard, Christensen, Madsen and Mikkelsen2020; Bol et al., Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021), the intention to vote for the political leader's party (Bol et al., Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021) and attachment to government parties (De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Bakker, Hobolt and Arceneaux2021). Therefore, we are confident that the COVID-19 pandemic serves as a valid case to study the composition of rally effects.

To isolate the diverging effects of perceived threat and anxiety on leadership approval, we require detailed individual-level data. Such data were collected by the German Internet Panel (GIP). The GIP is a high-quality online panel survey that surveys the same several thousand respondents six times a year. GIP respondents were randomly recruited offline from the German population (16–75 years) and, if needed, the GIP team provided respondents with Internet access, hardware and IT training to facilitate the participation of all sampled citizens in the survey. Thanks to these enormous efforts, the GIP marries the advantages of online surveys (e.g., flexibility and privacy) with the sampling standards researchers appreciate in high-quality offline surveys (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Gathmann and Krieger2015, see also https://www.uni-mannheim.de/en/gip/using-gip-data/methodology for more information on the GIP methodology and sample accuracy). A key advantage is relevant to studying the rally effect: The Mannheim Corona Study (MCS) was able to collect data from a high-quality sample online at a time when, to our knowledge, virtually all other high-quality survey projects had halted their data collection because interviewers could not meet respondents in person. Further, since the GIP had been collecting data for several years when the pandemic hit, it includes multiple measurements of relevant variables prior to the pandemic which we can exploit to test our hypotheses.

Figure 1. Change in government party approval around the week that the first 7 of 100,000 inhabitants tested positive for COVID-19. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The data we used for this article were collected in the GIP's MCS. The MCS is a special series of surveys that GIP respondents were invited to on top of their regular GIP participation. The MCS started when Germany was first approaching a COVID lockdown in late March 2020 and lasted a total of 16 weeks until July 2020. Hence, the MCS was in the field throughout most of Germany's first wave of COVID-19 infections, and a substantial period after the wave had ebbed away. At the survey's start, German schools had been shuttered for a week but more severe lockdown measures were yet to follow. During the period, the MCS applied a daily rotating individual-level panel design of the general adult population in Germany. Effectively, the GIP sample of about 4400 German residents was split into groups, each of which was invited to participate in the MCS on a given weekday (or the following day) in each of the 16 MCS weeks. The last round of recruitment into the sample was conducted about 18 months prior to the MCS. Hence, each MCS respondent was invited to answer at least 10 regular GIP surveys (and potentially many more if recruited earlier) before the MCS started. The MCS questionnaire changed each week and includes items on respondents' attitudes and behaviour in the context of the pandemic. The MCS also encompasses several panel items that were asked at different times (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Cornesse, Friedel, Krieger, Fikel, Rettig, Wenz, Juhl, Lehrer, Möhring, Naumann and Reifenscheid2020).

Our dependent variable is based on an MCS item which asked respondents to what extent they are dissatisfied or satisfied with the work of Chancellor Angela Merkel.Footnote 7 Respondents replied on an 11-point scale. This survey item reflects our theoretical point of interest well since it taps into the theoretical concept of leadership approval. It is also very similar to survey items that researchers use to learn about rally effects in other countries (Seo & Horiuchi, Reference Seo and Horiuchi2024, p. 278). The survey item was included in 11 of the 16 MCS weeks.

Our first central independent variable of interest is perceived threat. An item that asks respondents to assess the degree to which they perceive the COVID-19 pandemic as a personal threat was included in all MCS weeks. It serves well to test the perceived threat mechanism because it measures respondents' perceptions of the pandemic threat directly. We rescale responses from an 11-point scale to the unit interval.

To empirically test the anxiety mechanism, we need to quantify how anxious respondents are. To this end, we use the MCS version of a state anxiety measure which was initially suggested by Englert et al. (Reference Englert, Bertrams and Dickhäuser2011). It is a simple additive index based on two survey items: the first item asks whether respondents feel worried, and the second is whether they feel nervous. Respondents indicate their feelings using a 4-point scale for each item. After summing up and rescaling, the resulting anxiety index ranges from 0 (no anxiety) to 1 (severe anxiety). It is available for all 16 MCS weeks.Footnote 8

We exploit the MCS panel design and additional MCS items to control for possible confounders. First, we estimate a linear respondent fixed effects model that removes all time-invariant differences between respondents by demeaning. To control for time-variant factors such as the state of the pandemic, we include the contemporary COVID-19 incidence rateFootnote 9 and per capita household income in the previous month. Finally, we add a dummy variable that indicates whether the respondent agrees with the federal government's policy to (not) close national borders on the day of the interview. Overall, we obtain a sample of 32,187 interviews by 3680 respondents. Each interview includes all the information we require, and each respondent participated in the MCS at least twice as required for the estimation of fixed effects models. To address potential issues of serial correlation and heteroscedastic errors, we compute clustered panel standard errors. We present summary statistics in Supporting Information SI.2.

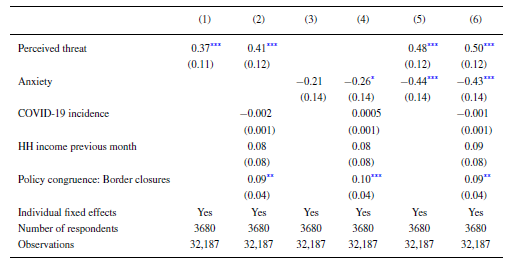

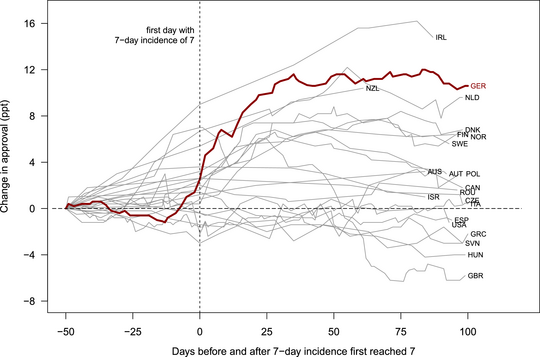

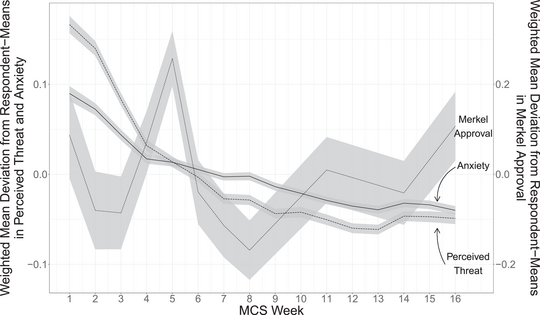

As an empirical test of the proposed individual-level mechanisms, we regress the approval of Chancellor Angela Merkel on perceived threat, the anxiety index and the mentioned controls. We apply weights as provided by the MCS team, which make the MCS data correspond to German census data with respect to several socio-economic dimensions (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Cornesse, Friedel, Krieger, Fikel, Rettig, Wenz, Juhl, Lehrer, Möhring, Naumann and Reifenscheid2020). We expect perceived threat to increase approval of Chancellor Merkel and anxiety to depress it. Table 1 reports the results of our fixed effects panel regression.

Table 1. The effect of perceived threat and anxiety on Merkel approval

Note:

![]() $^{*}$p

$^{*}$p

![]() ${}<{}$0.1; **p

${}<{}$0.1; **p

![]() ${}<{}$0.05; ***p

${}<{}$0.05; ***p

![]() ${}<{}$0.01.

${}<{}$0.01.

Please note that data collection for the MCS began only after the Corona pandemic had reached Germany (see below), and approval of Chancellor Angela Merkel in Germany had already risen sharply. Thus, the beginning of the Corona pandemic, when the rally effect had its strongest impact, eludes our analysis. Therefore, we expect the effect sizes to be smaller than in other cases.

Results: Threat and anxiety affect leadership approval

The findings lend strong support to both theorized mechanisms. Respondents rally around Chancellor Merkel as the head of the German federal government when feeling exposed to an external threat. The more pronounced threat perceptions are, the stronger the rally effect becomes which is in line with our perceived threat mechanism. When respondents feel anxious about the pandemic, however, we observe the opposite effect on Merkel's approval. In accordance with our anxiety mechanism, the data show that anxiety undermines the support for the head of government.Footnote 10 Models 1–4 in Table 1 indicate that these mechanisms operate independently of one another.

Both effects become particularly pronounced when tested simultaneously (Models 5 and 6): When perceived threat increases from 0 to 1, Germans' approval of Angela Merkel increases on average by about 0.5 units on an 11-point scale. As anxiety increases from 0 to 1, a respondent's approval of Chancellor Merkel decreases by about 0.4 units.Footnote 11

Turning to the control variables, we observe that neither an increasing COVID-19 incidence nor more household income has an effect on leadership approval once perceived threat and anxiety are accounted for. By contrast, approval of the government's containment strategy increases approval of Angela Merkel. Most importantly, the effects of perceived threat and anxiety remain substantially unaffected by the inclusion of the control variables. All else equal, the empirical evidence provided here suggests that the rally effect is related to an increase in individuals' threat perceptions. At the same time, the positive effect of perceived threat on the approval ratings of political leaders vanishes and, in fact, gets reversed once perceived threat is overshadowed by anxiety. In this situation, negative feelings dominate the assessment of political leaders during an emergency situation such as the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Two distinct mechanisms or multicollinearity?

From a theoretical point of view, perceived threat is a cognitive response to crises, whereas anxiety is an affective response (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005; Huddy & Feldman, Reference Huddy and Feldman2011; Miller, Reference Miller2000; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Krosnick, Holbrook, Tahk, Dionne, Krosnick, Chiang and Stark2016). Despite their theoretical distinctiveness, they are likely to correlate empirically when crises hit (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005; Miller, Reference Miller2000). This raises the concern that the results we present could be artefacts of the (potentially wrong) assumption that perceived threat and anxiety are independent from one another when they are not. Put more technically, we may deal with variables that are multicollinear, that is, perceived threat and anxiety may be highly, yet not perfectly correlated (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2009, p. 96). In the following, we search for patterns that one would expect to find if multicollinearity biased our conclusions about the perceived threat and anxiety mechanisms. We show that none of these patterns can be observed. This is strong evidence that the effects of perceived threat and anxiety are due to two distinct causal mechanisms rather than due to multicollinearity.

First, we turn to the pairwise correlation between respondents' perceived threat and anxiety. If perceived threat and anxiety were strongly correlated, the correlation coefficient should be statistically significant and of substantial size. As we seek to rule out that multicollinearity distorts the results of fixed effects regressions, we need to compute the correlation of the (two-way) demeaned perceived threat and anxiety variables within respondents. The corresponding weighted correlation coefficient is

![]() $r=0.31, p<0.001$. As expected, (demeaned) perceived threat and anxiety are positively correlated. However, the correlation is rather weak.

$r=0.31, p<0.001$. As expected, (demeaned) perceived threat and anxiety are positively correlated. However, the correlation is rather weak.

Second, we compute the variance inflation factors for Model 6 in Table 1 (full model). It provides a direct indication to what extent a regression model may (not) suffer from multicollinearity. We find that

![]() $VIF_{\text{Perceived Threat}}=1.27$ and

$VIF_{\text{Perceived Threat}}=1.27$ and

![]() $VIF_{\text{Anxiety}}=1.17$, which are both far below conventional thresholds for problematic levels of multicollinearity.

$VIF_{\text{Anxiety}}=1.17$, which are both far below conventional thresholds for problematic levels of multicollinearity.

Third, the patterns of the standard errors speak against multicollinearity. Consider a regression model with a single independent variable,

![]() $X_1$, which finds that

$X_1$, which finds that

![]() $X_1$ exerts a statistically significant effect on

$X_1$ exerts a statistically significant effect on ![]() $Y$. Next, suppose that a second independent variable

$Y$. Next, suppose that a second independent variable ![]() $X_2$ is added to the regression model. Importantly,

$X_2$ is added to the regression model. Importantly, ![]() $X_1$ and

$X_1$ and ![]() $X_2$ suffer from multicollinearity. Econometric theory teaches us that the standard errors of

$X_2$ suffer from multicollinearity. Econometric theory teaches us that the standard errors of ![]() $X_1$ should increase when

$X_1$ should increase when ![]() $X_2$ is added to the model (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2009, pp. 96–99). As Table 1 shows, this is neither the case when anxiety is added to a model that previously only included perceived threat (Model 1 to Model 5), nor when perceived threat is added to a model of anxiety (Model 3 to Model 5). Standard errors remain also unchanged when controlling for potential confounders (Model 2 to Model 6 and Model 4 to Model 6, respectively).

$X_2$ is added to the model (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2009, pp. 96–99). As Table 1 shows, this is neither the case when anxiety is added to a model that previously only included perceived threat (Model 1 to Model 5), nor when perceived threat is added to a model of anxiety (Model 3 to Model 5). Standard errors remain also unchanged when controlling for potential confounders (Model 2 to Model 6 and Model 4 to Model 6, respectively).

Overall, the results presented here suggest that perceived threat and anxiety are somewhat correlated. However, there is no evidence that this rather weak correlation drives the results we obtain. They rather support our theoretical claim that the two mechanisms operate independently from one another.

Reverse causality: Does Merkel propagate threat and anxiety?

Since our estimators are correlational in nature, their results reveal that Merkel approval on the one hand and perceived threat and anxiety on the other are associated. Since correlations are symmetric, the results do not immediately reveal whether changes in perceived threat and anxiety cause changes in Merkel approval or the other way around (reverse causality). In the following, we test additional empirical expectations that should be true if the article's main hypotheses were in fact reversed. We find no evidence for these expectations and conclude that our results do not mistake causes (perceived threat and anxiety) for effects of leadership approval.

If our hypotheses were in fact reversed, then leadership approval should lead to more perceived threat during the pandemic and at the same time to less anxiety. Playing devil's advocate to our own hypotheses, we note potential arguments why this may be the case: Suppose individuals who approve of Angela Merkel are more likely to believe her statements that the pandemic is a serious threat than individuals who oppose her. Then, Merkel supporters should feel more threatened by the pandemic than Merkel opposers.

With respect to Merkel approval's effect on anxiety a similar argument can be made: Suppose that citizens who oppose Angela Merkel believe that she is an incompetent Chancellor who cannot be trusted to deal with crises. The fact that she has to oversee the response to arguably the most severe crisis Germany faced in decades is likely to make these citizens anxious.

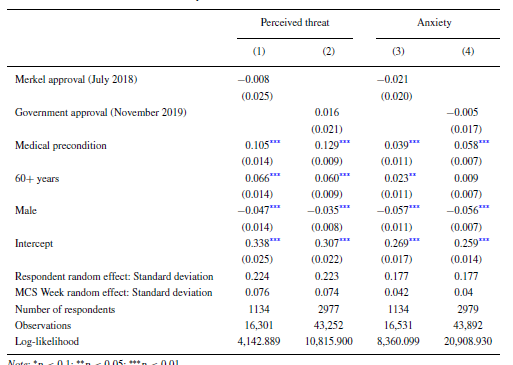

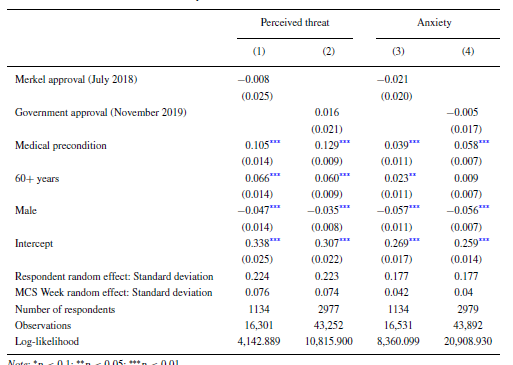

Even though we believe that these theoretical stories are implausible, they are valid theories with clear observable implications which we can test empirically. In fact, since the GIP collected data on the respondents already several months before the pandemic hit, we can exploit pre-pandemic leadership approval data to support or refute the claims the reversed arguments make. In particular, we test two hypotheses: First, the more satisfied a respondent was with Merkel before the pandemic, the more she feels threatened during the pandemic (because she is more likely to believe Merkel's warning that the pandemic is a serious threat). Second, the more a respondent was unsatisfied with Angela Merkel's performance prior to the pandemic, the more anxious she was during the pandemic (because she is more likely to fear Angela Merkel managing the crisis). In the following, we demonstrate that these ‘reverse’ hypotheses receive no empirical support.

We test for these patterns by estimating a set of hierarchical regressions on two different dependent variables: respondents' perceived threat and their anxiety during the pandemic. We acknowledge the fact that respondents provide multiple threat and anxiety ratings during the pandemic and add random intercepts at both the respondent and the MCS week levels. As a key independent variable, we use a (pre-pandemic) evaluation of Angela Merkel from July 2018. Since many MCS respondents were recruited to the GIP only later that year, roughly 50 per cent of respondents dropped out from this analysis. We, thus, also present evidence based on respondents' evaluations of the federal government in November 2019. While replacing evaluations of Angela Merkel by government evaluations does not immediately measure our theoretical point of interest, it allows us to use a more contemporary measurement and draw on the full sample of MCS respondents. Both measurements were collected on an 11-point scale which we recode to the unit interval. To corroborate the claim that Angela Merkel increased threat perceptions during the pandemic, either of these measurements (or both) should be positively correlated with perceived COVID-19 threat. To support the hypothesis that Angela Merkel triggers anxiety in citizens, they should be negatively correlated with anxiety.Footnote 12

To control for the most basic reasons why someone might feel threatened by or anxious because of COVID-19, we include a set of dummy variables each of which indicates that a respondent has a characteristic which is directly linked to a more severe course of COVID-19. These include an indicator variable for each male respondent, respondents with at least one of a list of specific medical preconditionsFootnote 13 and respondents who are more than 60 years of age (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Zheng, Gou, Pu, Chen, Guo, Ji, Wang, Wang and Zhou2020).

As Models 1 and 2 in Table 2 show, the effects of neither pre-pandemic Merkel approval nor pre-pandemic satisfaction with the federal government are significantly associated with the threat levels respondents report. Models 3 and 4 indicate that these factors are also not significantly associated with anxiety. Unsurprisingly, we find consistent effects that a medical precondition and gender are related to higher threat and anxiety levels. Further, high age increases perceived threat, yet results for anxiety levels are mixed. Overall, this analysis strongly suggests that Merkel supporters did neither heighten their perceived threat levels more than the average population nor were they more anxious during the early pandemic. These findings clearly refute the alternative mechanisms and substantially increase our confidence that anxiety and perceived threat drive approval of Angela Merkel and not the other way around.Footnote 14

Table 2. Does Merkel cause threat or anxiety?

Note: ![]() $^{*}$p

$^{*}$p ![]() ${}<{}$0.1;

${}<{}$0.1; ![]() $^{**}$p

$^{**}$p ![]() ${}<{}$0.05;

${}<{}$0.05; ![]() $^{***}$p

$^{***}$p ![]() ${}<{}$0.01.

${}<{}$0.01.

Ruling out parallel time trends

One may argue that our analyses pick up a set of parallel time trends rather than a causal pattern. Specifically, anxiety may have exceeded perceived threat at the onset of the pandemic. As Germans understood that the pandemic was something they could cope with, perceived threat may have become more dominant than anxiety. At the same time, yet for unrelated reasons, Angela Merkel's approval rating may have gone up over time. In the following, we refute this argument.

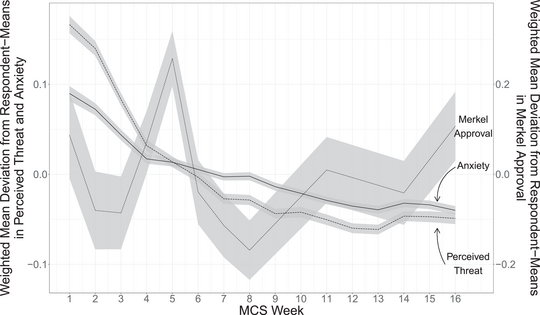

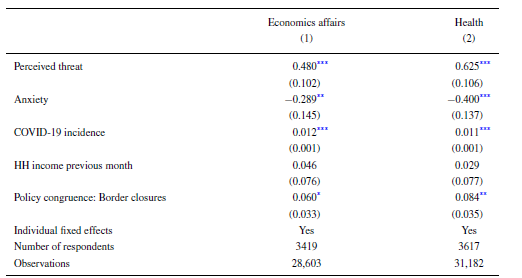

Since we utilize a fixed-effect framework, it would be misleading to evaluate the above claim by assessing absolute levels in perceived threat and anxiety.Footnote 15 Instead, we need to check whether deviations from respondent-means display the suspected patterns. Therefore, Figure 2 displays the mean deviations from respondent means in perceived threat, anxiety and Merkel approval in course of the MCS. All values are weighted according to the above-mentioned survey weights. In the first weeks, the weighted mean deviations from anxiety respondent means are smaller than the corresponding deviations with respect to perceived threat. Only later on, this pattern is reversed, while Merkel approval is more variable than expected and includes upward and downward spikes. These observations provide strong evidence that our estimates do not simply pick up a specific time trend.

Figure 2. Weighted mean deviations from respondent means in perceived threat, anxiety and Merkel approval throughout the MCS. Shaded areas depict corresponding 95 per cent confidence intervals.

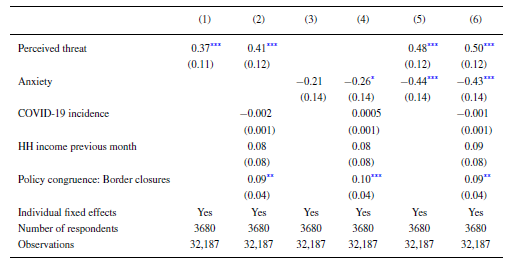

Increasing the scope: Approval of key ministers

Prior research suggests that the rally effect is not limited to the head of government but that it also affects government ministers (Gaines, Reference Gaines2002). In the following, we demonstrate that minister approval during times of crisis depends on the perceived threat mechanism and the anxiety mechanism. We focus on the German Minister of Health, Jens Spahn, and the Minister for Economic Affairs, Peter Altmaier. Both of them are members of Angela Merkel's Christian Democrats (CDU).Footnote 16 We replicate the above analyses on Angela Merkel's approval, yet we replace her approval ratings with respondents' evaluations of the corresponding ministers. The results appear in Table 3.

Table 3. The effect of perceived threat and anxiety on minister approval

Note: ![]() $^{*}$p

$^{*}$p ![]() ${}<{}$0.1;

${}<{}$0.1; ![]() $^{**}$p

$^{**}$p ![]() ${}<{}$0.05;

${}<{}$0.05; ![]() $^{***}$p

$^{***}$p ![]() ${}<{}$0.01.

${}<{}$0.01.

As expected, while the effects of some control variables differ slightly, we find similar effects for our main explanatory variables on satisfaction with Minister of Health Spahn and Minister for Economic Affairs Altmaier. Even the magnitude of the effects is comparable in size to the ones reported with respect to Angela Merkel's approval ratings. While an increase in threat perceptions boosts approval, anxiety decreases it. As a result, these analyses confirm that the anxiety mechanism and the perceived threat mechanism are not restricted to the head of government. Instead, we provide evidence that key ministers, who are also immediately involved with crisis responses, are also subject to them.

Conclusion and discussion

We present theoretical reasoning and robust empirical evidence that perceived threat and anxiety have distinct effects on leadership approval in times of crises. Using German individual-level panel data from the early COVID-19 pandemic, we causally identify that perceived threat increases citizens' support of their leader, and anxiety decreases it. Moreover, we show that perceived threat and anxiety also have the expected effect on the approval of ministers who manage key crisis portfolios. Our findings yield highly important implications for our understanding of how the so-called rally effect evolves, and how it shapes the politics of crises in democracies.

Our finding that perceived threat and anxiety have distinct and opposed effects on leadership support has striking implications for democratic crises politics. It suggests that politicians and political parties face strategic incentives to exploit crises to their advantage. Based on our two counteracting mechanisms, we would expect that politicians affiliated with the government or the opposition strategically frame crises as threatening or frightening to advance their political goals and to exploit how times of crises play out in public opinion. Previous research suggests that government and opposition develop different crisis exploitation strategies and that contextual features condition whether a government is likely to gain additional support from crisis exploitation or not (Boin et al., Reference Boin, 't Hart and McConnell2009). Future research should, thus, scrutinize how government and opposition crisis rhetoric aim at threat perceptions and anxiety, under what circumstances their crisis rhetoric affects individual levels of perceived threat and anxiety, and when and why corresponding effects are strong and durable enough to influence election results, government stability and crises policy-making.

Similarly, our theory provides a route for understanding leadership approval in the context of crises at the macro-level: At the individual level, we find that perceived threat increases leadership approval, while anxiety depresses it. A logical implication is that if the perceived threat-to-anxiety ratio increases, leadership approval should increase while it should decrease if the ratio decreases. It is beyond this article to investigate these and additional macro-level implications. Nevertheless, future research should evaluate these hypotheses.

In substantive terms, this also implies that the type of crisis (e.g., natural disasters vs. wars), the nature of responses both with regard to policy action (e.g., risk-taking or risk-averse government action) as well as framing (e.g., by the government or the opposition), and various individual level and contextual factors (e.g., an individual's geographical proximity to the centre of crisis, individuals' perceived problem-solving competence of political leaders) influence the extent to which crises shift political support on the individual and the mass level. For instance, it stands to reason that a crisis framed as threatening paired with an effective crisis management by the government lends greater levels of political support than a similar crisis that is framed as less severe and ineffectively tackled. Investigating individual-level and mass-level shifts of political support under changing compositions of these factors opens various paths for future research. Moreover, similar effects on other critical aspects, including trust in the political system or politicians in general, should be studied.

Our study also makes significant contributions to our understanding of the rally effect's scope. We delivered evidence indicating that the effects of perceived threat and anxiety are not limited to the political leader but also pertain to other members of the government. In fact, also in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, not only President George W. Bush received a boost in support but also Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and Secretary of State Colin Powell (Gaines, Reference Gaines2002). Unfortunately, our study has to stop short of studying the rally effect's partisan scope. For multi-party systems with coalition governments, it would be interesting to study whether the perceived threat effect also translates to ministers of the junior coalition partners. There is some evidence from The Netherlands indicating that this is not the case (Beijen et al., Reference Beijen, Otjes and Kanne2022). It is conceivable that the perceived threat mechanism first and foremost boosts support for the head of government as the most prominent figure of the nation's political leadership. Then, there might be spillover of this effect to ministers of the same party of the government's head but not, or to a lesser extent, to ministers of other parties. Similarly, with regard to vote choice, the perceived threat mechanism can be expected to increase electoral support for the party of the head of government while junior coalition parties, which have a less apparent association with the political leadership and also less media attention than the senior party (Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2020) might profit to a lesser degree.

Finally, our results also yield implications for crises' ability to harm democratic principles. The findings that anxiety and perceived threat have opposing effects on leadership approval add a new layer to other crisis-related research. Prior scholarship reports a tendency for more anxious citizens to value stability and maintain their prior behaviour, whereas citizens who feel more threatened demand action and are willing to change. For instance, anxiety is related to opposing a foreign intervention after 9/11 (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005), a smaller probability to use a mobile phone application that traces contacts during the COVID pandemic (Witteveen et al., Reference Witteveen and de Pedraza2021) and a preference for less disrupting electoral candidates (Bisbee & Honig, Reference Bisbee and Honig2022). Citizens who felt more threatened, by contrast, were more likely to support a foreign intervention following 9/11 (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005), more likely to allow their smartphone to trace their contacts (Wnuk et al., Reference Wnuk, Oleksy and Maison2020), and more likely to vote for robust responses to terror (Getmansky & Zeitzoff, Reference Getmansky and Zeitzoff2014). Adding leadership support to the list of perceived threat's consequences, thus, raises concerns with respect to democratic theory: The fact that the rather change-driven share of the population is also likely to lend additional support to the government may open a window of opportunity for the government to alter systems of checks and balances. When crisis support for the government wanes, these changes are often locked in so that they will not be fully reversed. The Patriot Act passed by the US Congress in the aftermath of 9/11 serves as a prime example.

Acknowledgements

This paper uses data from the German Internet Panel (GIP) and the Mannheim Corona Study (MCS). The GIP and the MCS infrastructure were funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) through the Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 884 ‘Political Economy of Reforms’ (SFB 884; Project-ID: 139943784). The later data collection waves of the MCS were funded by the German Federal Ministry for Work and Social Affairs (BMAS; Project-ID: FIS.00.00185.20). Roni Lehrer and Sebatisan Juhl would like to thank these funding agencies for supporting their work on these projects.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Table SI1: Summary Statistics: German Panel Data

Table SI2: First Difference Evidence: Perceived Threat and Anxiety

Table SI3: First Difference Models

Figure SI1: Weighted Means of Perceived Threat, Anxiety and Merkel Approval over time

Table SI4: The Effect of Perceived Threat and Anxiety on Merkel Approval (Standardized Variables)

Figure SI2: MCS response rates (solid line) and AARBs (dashed line) over time

Table SI5: The Effect of Perceived Threat and Anxiety on Merkel Approval (Lagged Dependent Variable Model)

Table SI6: Cross-lagged panel model

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the GESIS data archive at https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13700.