1. Introduction

The pursuit of effective healthcare policy occupies a central position in global public policy discourse, driven by the significant economic and political ramifications of inadequate systems (Bayat et al., Reference Bayat, Kashkalani, Khodadost, Shokri, Fattahi, Seproo, Younesi and Khalilnezhad2023). While the fundamental objectives of any health system – improving population health, meeting public expectations, and providing financial protection against illness – remain universal, their realisation often proves elusive. Lofty ambitions to transform healthcare systems often founder due to policy design flaws, ineffective implementation, and stakeholder opposition (Hafner and Shiffman, Reference Hafner and Shiffman2013; McConnell, Reference McConnell2010a; Reich, Reference Reich2020). Health reform is a protracted and inherently complex process, susceptible to reversals, policy drift, and governance failures. Despite these persistent challenges, some countries such as Thailand and Singapore have demonstrated notable success in specific reform areas, achieving improved health outcomes at comparatively low cost (Tangcharoensathien et al., Reference Tangcharoensathien, Witthayapipopsakul, Panichkriangkrai, Patcharanarumol and Mill2018; Tan and Lee, Reference Tan and Earn Lee2019). These successes raise crucial questions about the factors that differentiate effective reforms from those that fall short. The existence of successful health reform initiatives points to the need for exploring the factors underlying successful reform.

This paper argues that active government stewardship is a pivotal factor in health policy success. Stewardship refers to the government’s role in providing oversight, direction, and vision for the health system (Brinkerhoff et al., Reference Brinkerhoff, Cross, Sharma and Williamson2019; WHO, 2000). Active stewardship transcends passive oversight by proactively shaping policy design and driving implementation (He et al., Reference He, Bali and Ramesh2022). By integrating political, analytical and operational components, active stewardship enables governments to craft contextually appropriate policies, build coalitions of support, and adapt to changing circumstances. This paper posits that active stewardship, encompassing both astute policy design and robust implementation, is essential for navigating the complexities of healthcare reform and achieving desired outcomes.

To illustrate the mechanisms through which active stewardship operates, this paper examines the case of healthcare reform in Sanming, China. Despite its relatively constrained economic and institutional conditions, Sanming launched ambitious reforms in 2011 to control costs, improve quality of care, and reallocate healthcare resources. Through strong government stewardship, Sanming achieved notable successes in producing better health outcomes (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Li, Li, Yang and Hsiao2017). In 2023, Sanming achieved a life expectancy at birth of 80.2 years, exceeding the national average of 78.6 years. The city also demonstrated superior health outcomes across key indicators, including lower maternal, infant, and child mortality rates. In recognition of these achievements, the Chinese central government formally adopted Sanming’s approach as the core model for health system reform nationwide, advocating its adoption to extend benefits and ensure sustainability (Song and Li, Reference Song and Li2024a). Studying Sanming therefore extends beyond a local pilot case as it offers valuable insights into how the world’s most populous nation is advancing health system reform. The case also serves as a compelling illustration of how active stewardship can overcome constraints to translate policy aspirations into tangible improvements in health system performance, offering a transferable framework for other settings facing similar governance and financing challenges.

The paper begins by reviewing relevant literature on policy design, health system stewardship, and policy implementation. It then introduces an analytical framework encompassing six core stewardship functions: formulating strategic direction, aligning system structures, establishing appropriate policy instruments, building partnerships, ensuring accountability, and generating intelligence (Brinkerhoff et al., Reference Brinkerhoff, Cross, Sharma and Williamson2019; Veillard et al., Reference Veillard, Cowling, Bitton, Ratcliffe, Kimball, Barkley, Mercereau, Wong, Taylor, Hirschhorn and Wang2017). The Sanming case is presented to illustrate how the local government exercised these stewardship functions to achieve successful reform. This paper presents a generalisable analytical framework for understanding how active stewardship drives successful health system. Through an empirically grounded case study of Sanming, we demonstrate how this framework can be applied in practice, providing concrete evidence that active government stewardship can achieve substantial health improvements, even in environments with limited resources. The study offers a validated approach to analysing health reform governance and provides policymakers facing similar challenges with transferable implementation lessons.

2. Stewardship functions and components: a framework for analysis

Designing effective health policies is a complex endeavour, as health systems are characterised by numerous market failures, competing stakeholder interests, and multidimensional performance objectives (Roberts, Reference Roberts, Hsiao, Berman and Reich2004). Policymakers must balance the often-conflicting goals of expanding access, controlling costs, and assuring quality. Given this complexity, policy failures frequently stem from design flaws such as unrealistic assumptions, insufficient evidence, lack of specificity, and poor targeting (Béland et al., Reference Béland, Rocco and Waddan2018; McConnell, Reference McConnell2010b), as well as ineffective implementation, including poor coordination, mistakes in the use of discretion, and inefficient regulation (Bayat et al., Reference Bayat, Kashkalani, Khodadost, Shokri, Fattahi, Seproo, Younesi and Khalilnezhad2023; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Christensen and Painter2014; Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Hunter and Peckham2019).

Overcoming these design and implementation challenges requires robust government stewardship. The notion of stewardship positions the government as the ‘trustee’ of public health, emphasising its duty to act in the interest of the population rather than just its own bureaucratic imperatives (Saltman and Ferroussier-Davis, Reference Saltman and Ferroussier-Davis2000). Effective stewardship enables the government to establish a strategic direction for the health system, mobilise stakeholders, and formulate workable policies in the design process. It also facilitates the identification of various deficiencies that impede health reforms (Brinkerhoff et al., Reference Brinkerhoff, Cross, Sharma and Williamson2019).

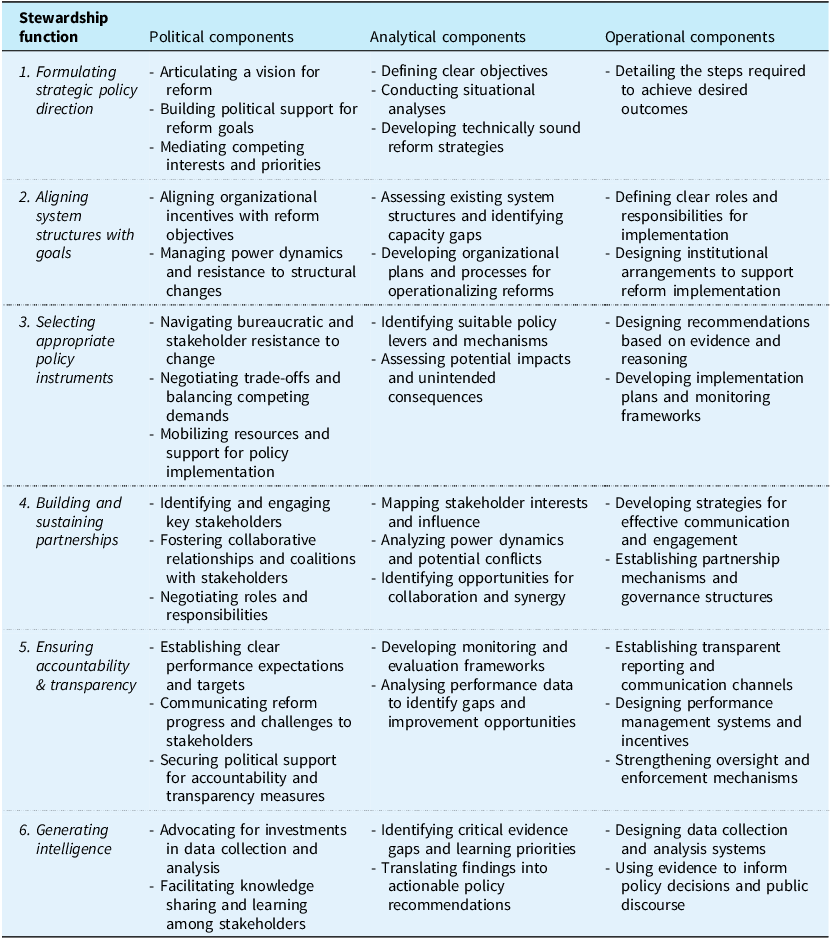

However, effective health system stewardship is a complicated undertaking that requires intricate coordination of various functions spanning policy design and implementation. Veillard et al. (Reference Veillard, Cowling, Bitton, Ratcliffe, Kimball, Barkley, Mercereau, Wong, Taylor, Hirschhorn and Wang2017) and Brinkerhoff (Reference Brinkerhoff, Cross, Sharma and Williamson2019) provide foundational works that illuminate the core aspects of stewardship in the healthcare sector. Building upon their insights and the work of Cross et al. (Reference Cross, Sayedi, Irani, Archer, Sears and Sharma2017, Reference Cross, De La Cruz and Dent2019), this paper proposes six essential stewardship functions that are instrumental in realising the transformative potential of health reform. These essential functions include (1) formulating strategic policy direction, (2) ensuring the alignment of system structures with strategy and policy goals, (3) establishing the legal, regulatory, and policy instruments to guide performance, (4) building and sustaining relationships, coalitions, and partnerships, (5) ensuring accountability and transparency, and (6) generating intelligence. To successfully carry out these functions, governments must cultivate and employ capacities to carry out a mix of tasks across three core components: political, analytical, and operational.

Table 1 presents a framework that integrates the six essential stewardship functions to their respective political, operational, and analytical requirements. This framework serves as a tool for assessing the effectiveness of stewardship in the context of health reform. By systematically examining each function and its associated components, policymakers and researchers can identify strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for improvement in the stewardship of health systems.

Table 1. Stewardship functions and the requisite political, analytical, and operational components

Note: authors, based on Cross et al. (Reference Cross, Sayedi, Irani, Archer, Sears and Sharma2017, Reference Cross, De La Cruz and Dent2019).

The first function involves setting a strategic policy direction for the health system. This requires establishing a clear, compelling vision for reform that articulates the rationale, goals, and pathways for change (Reich, Reference Reich2020). Crafting a purposeful reform agenda demands robust situational analysis to diagnose health system shortcomings, identify windows of opportunity, and assess political feasibility (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Hsiao, Berman and Reich2004). Equally important is the ability to mobilise diverse stakeholders around a shared reform narrative.

The second key function is aligning system structures with reform objectives. Health systems are inherently complex, with multiple actors with divergent interests operating across different levels of governance (Frenk et al., Reference Frenk, Chen, Bhutta, Cohen, Crisp, Evans, Fineberg, Garcia, Ke, Kelley, Kistnasamy, Meleis, Naylor, Pablos-Mendez, Reddy, Scrimshaw, Sepulveda, Serwadda and Zurayk2010). Implementing reforms requires reconfiguring institutional arrangements and organisational incentives to orient behaviour toward desired outcomes. Structural alignment may involve changes to authority hierarchies, service delivery models, financing flows, and accountability relationships (Figueras, Reference Figueras, Robinson and Jakubowski2005).

Selecting appropriate policy instruments to guide health system performance is the third critical stewardship function. Policy instruments refer to the specific rules, standards, incentives and nudges that shape actor behaviour within a given health system (McDonnell and Elmore, Reference McDonnell and Elmore1987). Designing effective instruments requires a keen understanding of how different policy levers interact with each other and with local contexts to produce intended and unintended consequences. This complexity also makes it imperative to complement policy design with robust, evidence-based implementation strategies that can navigate competing priorities while operating within resource constraints.

The fourth function, stewarding health reforms, demands active coalition-building and partnership management. Engaging diverse stakeholders – including providers, payers, patients, and civil society organisations – is essential for mobilising resources, fostering collective action, and generating reform legitimacy (Rasanathan et al., Reference Rasanathan, Atkins, Mwansambo, Soucat and Bennett2018). The process begins with a careful analysis of the stakeholder landscape, power dynamics and potential points of conflict, which informs the development of collaboration frameworks. Nurturing such multi-sectoral collaborations can enhance policy coherence, implementation coordination, and mutual accountability (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Glandon and Rasanathan2018).

The fifth key function involves institutionalising accountability and transparency mechanisms. Accountability refers to the processes by which health system actors are held responsible for their actions and outcomes (Brinkerhoff, Reference Brinkerhoff2004). Effective accountability systems combine top-down oversight tools with bottom-up feedback channels and operate across three broad areas: financial, system performance, and political (Cross et al., Reference Cross, Sayedi, Irani, Archer, Sears and Sharma2017; Joshi, Reference Joshi2013). Transparency, applied both within health ministries and in their public interactions, entails the proactive disclosure of health system information to enable improvement opportunities and public scrutiny and promote trust (Paschke et al., Reference Paschke, Dimancesco, Vian, Kohler and Forte2018).

Finally, stewarding health reforms requires continuous intelligence-gathering to inform adaptation. Generating timely, relevant data on health system performance is crucial for surfacing implementation challenges, identifying course corrections, and demonstrating progress (Wyber et al., Reference Wyber, Vaillancourt, Perry, Mannava, Folaranmi and Celi2015). This may include investing in health information systems, commissioning targeted evaluations, and institutionalising learning feedback loops. Equally important is how this evidence is translated into action – informing both policy decisions and public dialogue to drive meaningful change.

While the specific manifestations of stewardship may vary across contexts, the core functions identified in this framework serve as a generalisable template for assessing and strengthening reform processes. The following section outlines the methods employed in this study before applying the analytical framework to examine how stewardship operated in practice during China’s Sanming health reform. By tracing stewardship activities across each functional domain, the case analysis generates transferable lessons for reform practitioners grappling with similar challenges in other settings.

3. Research methods

This study employs a qualitative case study approach to examine how active stewardship shapes health reform outcomes, using Sanming as an illustrative example. Sanming, a prefecture-level city in China’s Fujian province, provides an ideal case for analysis given its significant reform achievements in curbing cost growth, strengthening primary care, and improving public hospital performance.

The investigation is guided by an analytical framework derived from health systems and public policy literature, which identifies six core stewardship functions: strategic visioning, institutional alignment, instrument design, partnership management, accountability reinforcement, and learning facilitation. This framework structures the analysis of how specific stewardship practices influenced both the design and implementation of Sanming’s reforms.

To ensure methodological rigour, we employed a triangulated research approach combining document analysis with primary data collection. The document analysis encompassed a comprehensive review of published research, policy documents, and government reports concerning Sanming’s reforms. We systematically searched PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Science databases, alongside grey literature repositories, using keywords including ‘Sanming’, ‘health reform’, ‘health policy’, ‘stewardship’, and ‘China’. Both English and Chinese materials analysing governance factors within the Sanming reform context were included, providing detailed insights relevant to each of the six framework domains.

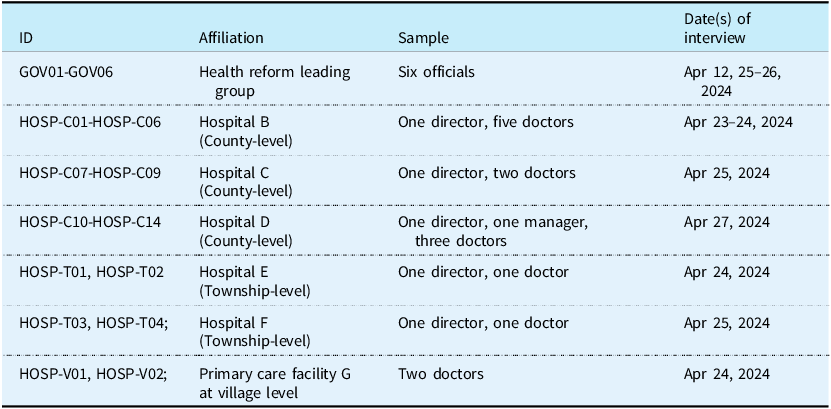

Primary data collection involved semi-structured interviews conducted in April 2024. With local government facilitation, we interviewed 26 stakeholders directly involved in Sanming’s healthcare reform. This sample comprised six senior health policy officials from Sanming’s government, fourteen hospital administrators and doctors from three county hospitals, and six healthcare professionals from township and village facilities (Table 2). Purposive sampling ensured representation across key stakeholder groups, including policymakers from departments responsible for finance and public health policy formulation, and healthcare providers from the three-tier medical conglomerates through which reforms were implemented. To accurately capture the evolution of the Sanming reform, our methodology engaged key participants who had demonstrated exceptional continuity despite the reform spanning a decade. The core government policymakers have provided continuous leadership since the reform’s inception, while senior hospital administrators and doctors have implemented the reforms throughout this period. This approach ensures that our data provides a consistent, longitudinal, and authoritative perspective on the evolution of the reform.

Table 2. Interview respondents

Note: Hospitals B and E, along with primary care facility G, belong to the same medical conglomerate; Hospitals C and F belong to the same medical conglomerate.

The semi-structured interview format balanced consistency with flexibility. We provided core topics while encouraging participants to explore issues they deemed significant through follow-up questions. Government officials discussed their decision-making processes, implementation challenges, and policy considerations. Healthcare providers at county, township, and village levels shared their interpretations of reforms, described practical implementation experiences, and reflected on operational difficulties. Interviews ranged from 20 to 60 minutes and, with participant consent, were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis followed an iterative process of extraction, synthesis, and interpretation. Interview transcripts were analysed within the six-function stewardship framework to understand how these functions interact to shape reform success. Information on reform context, objectives, strategies, and outcomes was systematically organised according to each stewardship function. Through comparative analysis, key patterns and themes emerged, with illustrative examples selected to demonstrate practical application of stewardship functions. The analysis also examined interactions and tensions between different stewardship practices and their evolution over time. Interview excerpts were systematically integrated to substantiate key findings.

The following section reviews Sanming’s health reforms and analyses its experience through the developed framework, focusing on the core components of stewardship functions. The concluding section then discusses the active stewardship required for successful health reform.

4. Background and extant knowledge

Market-oriented reforms in China during the 1990s led to the dismantling of the rural cooperative medical system which in turn caused rising out-of-pocket costs and widening health inequities. In response, China launched a series of reforms in the early 2000s aimed at expanding insurance coverage, strengthening primary care, and improving service delivery (Ramesh and Bali, Reference Ramesh and Bali2021). Reforms in 2009 further expanded insurance coverage, increased government subsidies, and introduced a national essential medicines system. Despite progress, challenges related to quality, efficiency, and integration persisted. In recent years, China has scaled up the reforms by adopting broader and deeper reforms aimed at promoting value-based care, strengthening provider payment systems, and leveraging digital technologies. In Sanming, similar to many other cities, the reforms were distinguished by extensive piloting before being scaled up and expanded. What distinguished Sanming was the notable success its reforms centred on active government stewardship achieved, making it a fruitful case for study and emulation (He, Reference He2023).

Beginning in 2011, the Sanming municipal government embarked on an ambitious reform agenda aimed at controlling cost growth, improving service delivery, and improving the performance of public hospitals. The immediate cause of the reform was the bankruptcy of its medical insurance fund, with the medical insurance schemes together owed the public hospitals 17.5 million yuan (He, Reference He2018). Sanming has a seriously ageing population, with a large number of retired workers. This puts significant strain on the financial sustainability of the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) and Urban and Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URRBMI). In 2023, Sanming’s UEBMI dependency ratio was 1.47:1, meaning 1.47 active workers supported each retiree who had not contributed to the UEBMI system. This was far below the national average of 2.71:1, and the ratio continued to deteriorate, dropping to 1.40:1 in 2024. Furthermore, Sanming city lags behind in terms of economic development, ranking seventh out of the nine prefecture-level cities in Fujian Province. Consequently, the financing level of its funds remains relatively low, with per capita funding for medical insurance schemes for employees and residents falling below the national average. UEBMI stands at 4,204 yuan and URRBMI at 990 yuan per year, compared to national figures of 6,182 yuan and 1,098 yuan, respectively.

Despite these limitations, Sanming’s reforms have achieved notable success in ensuring the sustainability of the insurance fund and reducing out-of-pocket costs for patients. Since 2012, the UEBMI and URRBMI funds in Sanming have remained in surplus, while inpatient reimbursement rates have increased substantially, from 72.26 per cent to 76.63 per cent for urban employees and from 46.25 per cent to 68.63 per cent for residents, between 2011 and 2023 (Sanming Municipal Health Commission, 2024). Significant progress has also been made in chronic disease management, with control rates for hypertension and diabetes reaching 88.04 per cent and 87.54 per cent, respectively. Furthermore, provider prescription behaviours also shifted, with a notable decline in antibiotic prescription rate in county-level hospitals (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Fu, Wushouer, Ni, Li, Guan and Shi2022).

These achievements affirmed the local success of the reform and captured the attention of the central government, which played a crucial role in scaling up the Sanming pilot innovation. The Ministry of Finance initiated this state-led diffusion process when it identified the model’s potential to alleviate systemic financial strain. Subsequently, the National Health Commission encouraged the nationwide adoption of Sanming’s experience within five years to magnify the impacts of its pilots. (Song and Li, Reference Song and Li2024a; The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2024). To support this initiative, the central government has developed an integrated set of policy instruments spanning four key areas: governance, drug procurement, medical insurance, and service provider (Song and Li, Reference Song and Li2024b). This coordinated, top-down promotion has led to widespread, though uneven, adoption across China. Many municipalities have implemented selected components of the reform, particularly those with politically ambitious leadership or those experiencing fiscal pressures similar to Sanming’s initial situation. However, some local governments have adopted a cautious wait-and-see approach, observing the outcomes in regions that adopted the reform early before committing to full implementation (Li and Song, Reference Li and Song2023).

Overall, Sanming’s experience demonstrate that systemic reform can yield substantial gains even under constrained fiscal and demographic conditions. While the specific contours of Sanming’s reform reflect the idiosyncrasies of the local context, the underlying stewardship practices offer transferable lessons for policymakers in other settings, particularly in middle – and low-income countries. In the discussion below, we examine Sanming’s reforms in relation to six core stewardship functions to reveal how these stewardship practices contributed to significant improvements in health system performance (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Mao, Li and Du2015; Zhan, Reference Zhan2021).

5. The Sanming healthcare reform: active stewardship in practice

5.1. Formulating strategic policy direction

Sanming’s reform started with a clear articulation of strategic policy direction, which aimed to transform the local healthcare system from a fragmented, volume-driven model to one that prioritised efficiency, equity, and long-term population health. The overarching vision was to reduce unnecessary waste, redesign incentive mechanisms, and refocus healthcare delivery on health. This vision evolved in three distinct but interrelated phases, each building on the achievements of the previous phase while expanding the scope and ambition of the reform.

The first phase focused on reforming drug pricing, which was a major source of waste and public dissatisfaction. By implementing centralised drug procurement and a zero-mark-up policy, Sanming eliminated profit-driven prescribing and redirected savings to fund deeper structural reforms. Building on this foundation, the second phase comprehensively reformed public hospitals while strengthening primary care. Service price adjustments, in particular the increased valuation of doctors’ work, reoriented incentives towards patient-centred care rather than revenue generation.

The third phase was even more ambitious, aiming to build a health system centred around the concept of ‘health-centred development’. This framework shifted reform goals from a narrow focus on treating disease to a more holistic emphasis on promoting population health. The change in strategic focus was informed by thorough situational assessments that revealed the significant burden of chronic disease, the fragmentation of service delivery, and the perverse incentives driving cost escalation (Fujian Province Health Commission, 2025). By this time, Sanming’s goals had expanded beyond cost containment to include broader societal health outcome.

Throughout these phases, Sanming’s reform objectives were progressively expanded and refined. The first phase prioritised reducing waste and rationalising drug expenditure. The second phase used these savings to create the conditions for public hospital reform, ensuring financial sustainability while realigning incentives. The final phase elevated the ultimate health-centred goal, integrating lessons from earlier phases into a cohesive, forward-looking strategy. This phased approach allowed for adaptive policymaking and the gradual consolidation of political and public support, ultimately positioning Sanming as a pioneering model for healthcare reform.

5.2. Aligning system structures with goals

To translate the strategic vision into action, the government restructured institutional arrangements to facilitate policy coordination and implementation oversight. At the centre of this realignment was the establishment of a dedicated Health Reform Leading Group in 2012, which brought together multiple departments involved in administering medical insurance. Chaired by the vice-mayor and comprising representatives from key municipal agencies, the Leading Group served as the primary decision-making body for reform design and implementation. This high-level institutional structure enabled streamlined policy development, reduced bureaucratic fragmentation, and concentrated accountability for reform outcomes (Li, Reference Li2024; Yue and Wang, Reference Yue and Wang2017). In addition to the Leading Group, Sanming further institutionalised the functions of the decentralised departments in 2016, which was endorsed by the central government and further entrenched with the establishment of the National Health Security Administration (NHSA) in 2018. These institutional changes transformed the fragmented landscape of medical insurance institutions and promoted cohesion and coordination across the system.

The creation of the Leading Group highlights the value of institutional adaptation in fostering the political and managerial conditions for effective stewardship. Health governance in China is characterised by a ‘dual steward’ structure, in which the National Health Commission (NHC) and its local branches are responsible for supervising public and private medical institutions, while the local Health Security Administration (HSA) administers medical insurance funds and acts as a third-party purchaser of health services (He et al., Reference He, Bali and Ramesh2022). The two departments are not well connected (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Ma, Fang and Yang2019), but this was considerably reduced in Sanming following the establishment of the Leading Group.

This is exemplified by the vertical integration of the county-level medical conglomerate. In Sanming, the medical conglomerate has promoted integration and convergence of interests among service providers at different levels. Township hospitals and village clinics act as branches of the county hospital. The hospital’s centralised management coordinates their setup and staffing based on the local population and other factors. This achieves vertical integration of human resources and resource sharing. Mr. Z, a key official involved in Sanming’s reform, explains:

Township-level staff were originally managed by the local NHC, which caused a lot of inconvenience. Through Leading Group negotiations, we eventually transferred the management of township-level staff to the county hospital, creating a true conglomerate with common interests. While there may be disagreements between departments in other places, there is no discord among the members of our Leading Group. All departments work together to overcome difficulties.

5.3. Selecting appropriate policy instruments

Sanming’s reform also entailed the introduction of new policy instruments to steer health system performance. A centrepiece of this effort was the restructuring of provider payment mechanisms away from fee-for-service reimbursement which incentivised volume-driven care. To realign incentives, the government shifted to a combination of diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) payments and global budgets in 2016 (Sanming Municipal Government, 2021). These alternative payment models sought to decouple hospital revenues from service volume and encourage cost-conscious clinical decision-making.

Under this system, the local HSA annually allocates capitated medical insurance funds to ten county-level medical conglomerates in Sanming, allowing them to retain surpluses while taking financial responsibility for deficits. This strategic purchasing approach incentivises each conglomerate to allocate resources more efficiently, including to facilities at the township and village levels, while also expanding preventive services to reduce the incidence of major, costly diseases (Liu and He, Reference Liu and He2017). Mr. L, the director of a county-level hospital, explained:

In order to achieve a surplus in the insurance fund, we have an intrinsic motivation to improve the health of the population. Healthier populations require less acute care, which translates into greater savings. This is why we provide services such as free vaccinations, disease screening, and chronic disease management. If we have a surplus, we can use some of it to reward high-performing doctors and staff, aligning their motivation with our population health goals.

However, the success of this approach depends on the management skills and strategic vision of county-level hospital administrators. Inadequate governance can lead to financial deficits, destabilising hospital operations and affecting doctors’ incomes. There is also a potential misalignment of incentives, as hospital leaders might prioritise the expansion of their own facilities over facilitating the allocation of resources to lower-level healthcare providers. Additionally, the financial equilibrium of the medical conglomerate is highly vulnerable to external disruptions, particularly the recent policy improvements to cross-regional reimbursement, which have diverted patients to higher-level hospitals. The bundled payment system for medical insurance funds means that patient transfers divert these funds to other regions. While patients without referral approval face lower reimbursement rates, this exacerbates the financial pressures on county-level systems.

Since the beginning of the Sanming reform, the government has implemented complementary policy instruments to further strengthen the system. These include a centralised procurement system for drugs and medical supplies, which has lowered prices and curbed overprescribing (Li and Song, Reference Li and Song2023). In addition, the government has regularly updated medical service pricing to better compensate physicians. These instrumental reforms highlight the importance of designing incentive structures that can guide the behaviour of healthcare providers to achieve desired outcomes.

5.4. Building and sustaining partnerships

The success of Sanming’s healthcare reforms depended on deliberate and strategic coalition building to ensure that key stakeholders were not only identified but actively involved in shaping and implementing policy changes. A critical early step was to map stakeholder interests and influence, recognising that hospitals, primary care institutions, and public health authorities each had different priorities. By analysing these dynamics, reformers were able to anticipate potential conflicts and identify opportunities for collaboration. For example, while public hospitals initially resisted changes to revenue-based practices, their dependence on medical insurance funding created leverage for negotiations.

To build trust and alignment, Sanming adopted a dual approach, combining vertical integration with horizontal partnership structures. Vertically, the reform established a well-integrated medical conglomerate, bringing together county – and township-level hospitals and village-level primary care facilities under a unified management system. Under this structure, the county hospital centrally managed the human resources and salary disbursements of the three-tier institution, fundamentally transforming the previously independent institutions into a community with shared interests and aligned performance goals. This was particularly evident in the joint retention of surplus medical insurance funds, which was in contrast to the previous practice of competing for patients for their own benefit. This integration clarified roles and responsibilities while incentivising collaboration across levels of care through unified accountability and financial incentives.

Horizontally, innovative service purchasing mechanisms bridged the gap between preventive and curative care. A notable change was the reallocation of funds for basic public health services from direct grants to primary care facilities to centralised management by county hospitals. These hospitals then distributed funds based on performance by purchasing services from primary care facilities and public health agencies such as the local Centers for Disease Control (CDC). This approach not only allowed county-level hospitals to dynamically adjust purchased services in response to changing health priorities but also created interdependence between stakeholders, as hospitals relied on the local CDCs and primary care facilities for preventive care, while these facilities received stable funding linked to measurable outcomes.

Nevertheless, some criticism regarding insufficient collaboration has been acknowledged. While the alliance model strengthened operational integration, decision-making remained relatively centralised within the leadership of county-level hospitals. Although this top-down structure enhanced the agility of reforms, it sometimes limited the systematic involvement of grassroots clinical and public health staff in planning and adaptation processes. There were no formal mechanisms for structured consultation, such as regular feedback sessions with frontline health workers. This occasionally led to the perception that reform strategies reflected managerial priorities. Despite these challenges, Sanming’s reforms showed that continuously negotiated partnerships, even if not fully inclusive, can maintain momentum throughout complex systemic change. The evolving governance approach strikes a pragmatic balance between centralised steering and participatory adaptation, thereby contributing to stability and learning in coalition building.

5.5. Ensuring accountability and transparency

Promoting accountability and transparency was another critical facet of Sanming’s reform stewardship. In Sanming, county hospital directors were paid from the general budget, which broke the incentive link between their annual salary and the hospitals’ patient load. To address this problem, the government introduced a performance management system that linked hospital director’s remuneration to hospital efficiency and quality indicators. This fundamental shift created powerful incentives for hospital management to focus on delivering better care rather than simply increasing the volume of services. Directors of facilities that failed to meet established benchmarks faced financial penalties, while high performers received bonus payments. Mr. X explained the accountability design in a detailed manner:

The hospital director knows the county hospital best and knows how to run it effectively. That’s why we are using their performance evaluation to guide health reform - setting clear targets in their evaluation indicators, redesigning their incentives, and leveraging their leadership to align the entire health system with broader health goals. Since 2013, the evaluation indicators for hospital directors have evolved significantly. In the early stages of the reform, more attention was paid to indicators such as inpatient expenditure per capita to ensure the social responsibility of public hospitals. By 2024, the focus had shifted to improving the quality of medical services and integrated healthcare systems.

To increase public accountability, the government also began publishing hospital-level performance data through an online portal. Performance data was systematically collected and analysed to identify gaps in service delivery and opportunities for improvement. These transparency mechanisms also enable patients to make informed care-seeking decisions while pressuring underperforming facilities to improve. The combination of these measures created a closed-loop accountability system in which performance expectations were clearly defined, progress was continuously monitored, and results were transparently communicated. Sanming’s approach illustrates the mutually reinforcing nature of top-down and bottom-up accountability channels in incentivising responsiveness to reform goals.

5.6. Generating intelligence

Finally, the Sanming government prioritised continuous learning and adaptation throughout the reform process. The Leading Group established a robust monitoring and evaluation system to track key performance indicators and identify implementation gaps. Regular reviews were convened to assess progress, address troubleshoot challenges, and share best practice across facilities. The local HSA conducted monthly analyses of the performance of medical insurance fund, while the local NHC regularly assessed the composition of medical revenue in public hospitals. Similarly, public hospitals conducted internal operational reviews on a monthly basis. When data revealed unintended consequences, the government and hospitals rapidly adjusted policies to mitigate adverse effects. For instance, monthly analyses of medical insurance fund operations enabled county hospitals to pinpoint critical shortcomings in local diagnostic and treatment capabilities. One such example was the identification of persistently high referral rates for major diseases such as malignant tumours, which prompted a quick policy adjustment. In response, a collaborative diagnosis-and-treatment programme was established between county hospitals and provincial tertiary centres, significantly enhancing local capacity for treating these conditions. Under the medical insurance fund package, county hospitals are required to pay for referred patients. This meant that patients could receive high-quality care in their home counties, resulting in a marked reduction in referrals elsewhere and greater retention of insurance funds within the local health system. This agile, data-driven approach to governance enabled Sanming to maintain implementation fidelity while adapting to dynamic contextual realities.

6. Conclusion: active stewardship for health reform success

Health systems worldwide face mounting pressures from epidemiological, technological, and sociopolitical shifts, making effective reform increasingly urgent. This paper demonstrates that active government stewardship across six core functions – strategic visioning, institutional realignment, instrumental calibration, coalition-building, accountability reinforcement, and adaptive learning – critically determines healthcare reform success. The Sanming experience illustrates how these functions interact to transform a fragmented, inefficient system into one that delivers higher quality, equitable, and affordable care.

Sanming’s reform succeeded through integrated active stewardship. A clear strategic vision aligned with local priorities was operationalised through institutional restructuring that enabled rather than constrained change. Calibrated policy instruments – payment reforms, incentive mechanisms, and service delivery models – provided behavioural change levers, while coalition-building across levels and sectors created alliances with both motivation and influence to sustain momentum. Accountability systems combining top-down oversight with bottom-up transparency ensured alignment, while continuous learning enabled adaptive refinement. These components formed a self-reinforcing cycle: strategic direction shaped institutional design, facilitating policy development and implementation, strengthened through stakeholder engagement, maintained through accountability, and refined through ongoing learning.

Sanming operates within China’s distinct political-institutional context, where centralised hierarchy may have facilitated decisive reform leadership. More pluralistic settings with diffused power would likely face greater implementation challenges. Yet China’s bureaucracy itself presents obstacles – its fragmented architecture creates coordination challenges (He, Reference He2018). Sanming addressed this by establishing a leading group consolidating authority across healthcare departments, demonstrating how active stewardship overcomes structural diffusion.

Framework transferability depends on adapting core functions to different governance architectures. Federal systems with distributed health governance require enhanced institutional alignment through intergovernmental agreements or joint committees. Mixed public-private systems can adapt strategic purchasing and performance accountability through regulatory rather than direct control mechanisms. The phased approach – cost containment, provider incentive realignment, then integrated delivery systems – offers a sequenced pathway calibrated to varying starting conditions.

The findings significantly impact health systems struggling with market-led or network-based governance limitations. Active government stewardship provides a viable alternative where fragmentation and marketisation undermine equity and efficiency, particularly relevant for decentralised, market-driven systems like India’s. China’s strengthened hierarchical governance through Sanming yielded tangible improvements in cost control and performance (Ramesh et al., Reference Ramesh, Wu and He2014; Ramesh et al., Reference Ramesh, Wu and Howlett2015).

The framework can be applied to diverse typologies. Middle-income countries pursuing universal coverage learn that resource constraints need not preclude ambitious reform when stewardship functions align properly. Systems with expanded insurance but persistent quality and sustainability challenges benefit from understanding how procurement reforms, provider realignment, and integrated delivery work synergistically. Intelligence generation through continuous monitoring particularly aids systems with robust information infrastructure but underutilised adaptive policymaking capacity.

Government involvement alone is insufficient, as sustainable reform requires integrating all six functions. This especially applies where universal coverage guarantees remain hampered by misaligned incentives and fragmented governance, resulting in uncoordinated implementation and inequitable quality, as exemplified by Brazil’s Unified Health System (Paim et al., Reference Paim, Travassos, Almeida, Bahia and Macinko2011; Coelho and Szabzon, Reference Coelho and Szabzon2024). Sanming’s coherent function alignment created reform-enhancing synergies.

Mature systems facing sustainability challenges can adapt Sanming’s approach. The medical conglomerate model shows how vertical integration addresses care fragmentation in coordinating primary-secondary care. Balancing centralised procurement with performance incentives informs pharmaceutical expenditure control while maintaining provider autonomy. Success requires thoughtful adaptation to existing architectures rather than wholesale adoption.

The framework transcends specific contexts by identifying fundamental governance capabilities. Whether in unitary or federal states, tax-funded or insurance-based systems, public or mixed delivery models, the six functions provide diagnostic tools for identifying gaps and designing interventions. This coordinated governance approach extends to education, social protection, and other complex domains requiring multi-level coordination.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The sampling strategy, which focused on government officials, hospital administrators, and medical professionals at county, township, and village levels, may have introduced self-selection bias. Moreover, the perspectives of external stakeholders – including patients, pharmaceutical firms, and private insurers – were not incorporated, potentially limiting the comprehensiveness of our findings. While triangulation with policy documents and official reports helped enhance validity and mitigate these biases, future research would benefit from incorporating these broader stakeholder perspectives. Comparative studies examining how different institutional contexts adapt stewardship functions would be particularly valuable, helping to distinguish which reform elements are universally transferable from those that remain context-specific.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgements to declare.

Financial support

This article is a result of the Fujian Province Social Science Fund project, with approval number FJ2025C071, and is also funded by Fuzhou University (grant number XRC202419).

Competing interests.

The authors declare none.

Authors’ contributions

Haochen was responsible for research and preparing written drafts. Ramesh was responsible for conceptualising the paper and substantially editing the drafts. Both authors have approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not required by for this type of article.