Introduction

‘Banlieues’, ‘Ghettos’, ‘Vulnerable areas’, ‘Moellenbeek’ and ‘No-go zones’: These are official labels, names proper and derogatory terms that jointly identify a group of politized neighborhoods in contemporary Europe. The neighborhoods share two characteristics. Firstly, they are disadvantaged in terms of crime rates, labour market performance, reputation and other factors associated with wellbeing and prosperity. Secondly, a high proportion of residents are immigrants of non-Western origin (Arbaci, Reference Arbaci2007; Cassiers & Kesteloot, Reference Cassiers and Kesteloot2012; Escafré-Dublet & Lelévrier, Reference Escafré‐Dublet and Lelévrier2019). Socially disadvantaged neighborhoods are not new to Europe (Wacquant, Reference Wacquant1993), but the combination of social challenges and migration-driven ethnic diversity has generated a new political dynamic. Following debates on immigration and its consequences (Dancygier & Margalit, Reference Dancygier and Margalit2020; Green-Pedersen & Otjes, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Otjes2019; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010), the neighborhoods in question have become focal points for contentious issues such as interethnic relationships, parallel societies, spatial stigmatization, structural discrimination, social inequalities and, ultimately, social cohesion (Cantle, Reference Cantle2001; Neal et al., Reference Neal, Bennett, Cochrane and Mohan2013; Pinkster et al., Reference Pinkster, Ferier and Hoekstra2020; Stehle, Reference Stehle2012; Wacquant et al., Reference Wacquant, Slater and Pereira2014).

When political scientists examine conditions in vulnerable urban neighborhoods, they often address themes such as clientelism, policing, and the provision of public goods by the state, particularly in countries of the global south (Post, Reference Post2018). While these themes are also relevant in established European democracies (Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2017), they do not fully capture the essence of the political conflict under discussion. Ultimately, certain neighborhoods in contemporary Europe are perceived by central political actors to operate differently from the rest of society. From the perspective of the majority society, these places represent ‘areas of limited statehood’ (Risse & Stollenwerk, Reference Risse and Stollenwerk2018), prompting questions about the formation, maintenance and disruptions of local social order (Enroth, Reference Enroth2022).

This paper aims to contribute to the understanding of social order within politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods. Focusing on Sweden, where the discourse surrounding social order in such neighborhoods has long been a focal point (Gerell et al., Reference Gerell, Puur and Guldåker2022), we examine the group most affected by these conditions: the residents themselves.

Given the absence of established empirical indicators (Hechter & Horne, Reference Hechter and Horne2003; Schiefer & van der Noll, Reference Schiefer and van der Noll2017), we assess local social order indirectly by examining residents’ preferences for reforms aimed at improving conditions on the ground. In the political discussion at the national level, there is a consensus on the necessity for reform in these neighborhoods. However, the left-leaning, right-leaning and populist camps espouse differing perspectives on the root causes of these issues, leading to divergent opinions on the most pressing reforms. As we will demonstrate, disciplines within neighboring social sciences reflect the contentious nature of the political discourse, offering disparate explanations for the observed deviations in these neighborhoods.

Our contribution is grounded in the observation that there has been limited quantitative research soliciting residents’ opinions on reforms for their neighborhoods or the urgency of such reforms (cf. Friedrichs & Blasius, Reference Friedrichs and Blasius2003). To address this gap, we formulate two descriptive research questions: What reforms are most urgently sought by residents to enhance social order? (RQ1) How do resident preferences for these reforms vary and overlap? (RQ2)

To answer RQ1 regarding reform preferences among residents, we address two inherent challenges of descriptive analysis: measurement and the identification of observations that contradict proposed assertions (Gerring, Reference Gerring2012). We conducted repeated surveys among samples of residents to determine which reforms are deemed most urgent for improving the neighborhood. The reform proposals included in the survey are grounded in the everyday experiences of the neighborhood's residents and reflect themes aligned with left-wing, right-wing and populist ideologies prevalent in national elite discourse. The measurement instrument enables residents to both endorse and reject the necessity of improving social order in their neighborhood while also allowing them to express support for various political orientations. To provide further analytical leverage, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of Swedes to ascertain their reform preferences for their own, presumably better-functioning local neighborhoods.

Opinion research provides multiple potential answers to RQ2 concerning the structure of reform preferences. One possibility is that reform preferences align closely with ideological divisions, mirroring elite discourse. In such a scenario, residents favouring left-leaning reforms, such as job training programs and after-school activities, may show less enthusiasm for right-leaning proposals focusing on policing and crime, and vice versa. Another potential answer is that residents, overwhelmed by the challenges of navigating life in a difficult context, exhibit largely random preferences for neighborhood reforms, as suggested by some theories on public opinion quality and attitudinal structures (Achen & Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2017; Converse, Reference Converse and Apter1964; Jackson & Marcus, Reference Jackson and Marcus1975). A third option is that preferences are shaped by the unique lived experiences revealed in qualitative studies of marginalized groups in the US context (Cramer & Toff, Reference Cramer and Toff2017; Weaver et al., Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2019). In this case, residents’ preferences may remain stable but less aligned with traditional ideological frameworks.

We find that residents in Sweden's politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods see a great need for local reforms, and that reform preferences are structured, stable, meaningful, largely homogenous and independent of elite discourse. Importantly, residents have an ideologically balanced view of reform agendas. In line with a left-oriented perspective on what generates local social order, they see a need for more resources and institutional support, but there is equally strong support for the right-oriented perspective that people in the neighborhood should take greater personal responsibility and ‘shape up’. Compared to the nationally representative reference sample, residents perceive larger problems in their neighborhood, but they agree on what constitutes a well-functioning neighborhood. Overall, we find more that unites than separates residents in politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods from the rest of the population.

We make two additional contributions, one of which is methodological. Surveying residents in vulnerable neighborhoods has traditionally posed challenges for researchers (Tourangeau et al., Reference Tourangeau, Edwards, Johnson, Wolter and Bates2014). However, we demonstrate the feasibility of conducting high-quality surveys in these areas. Through the establishment of local contacts, our physical presence on-site, the formulation of questions relevant to residents' experiences, the provision of monetary incentives and the simplification of participation procedures, we have successfully conducted a multiwave survey panel with representative samples of residents in two Swedish politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods. In a field predominantly reliant on qualitative methods (e.g., Doucet & Koenders, Reference Doucet and Koenders2018; Kallin & Slater, Reference Kallin and Slater2014; Kurtenbach, Reference Kurtenbach2017; Wekker, Reference Wekker2019), the expansion of data collection methods represents a significant advancement.Footnote 1

Another contribution is conceptual. Through a synthesis of research from urban politics and consultations with country experts, we delineate the contours of a population comprising of politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods in European welfare states. By identifying common characteristics of these targeted neighborhoods, we enable future systematic comparisons and establish a foundation for generalizing our country-specific empirical findings.

In the following sections, we first present our conceptualization of the population under study. Next, we discuss our case selection, aligning our measurement strategy with theory, and detailing our data collection efforts. Proceeding to the results, we initially focus on substantive preferences (RQ1) before delving into the underlying attitudinal structures (RQ2). The final section concludes.

Background and theory

Politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods in Europe

The debate over neighborhoods that stand out negatively in relation to the rest of society endures in urban politics (Wacquant, Reference Wacquant2008). On an abstract level, these neighborhoods have common characteristics, such as being poor and of ill-repute, but, when they are more closely observed, heterogeneity can be seen within the population. Importantly, for our purposes, urban scholars have shown that European neighborhoods that qualify as vulnerable differ from corresponding neighbouhoods in the United States (US). In comparison, European neighborhoods are typically smaller, have higher (but deteriorating) housing standards, are more ethnically heterogenous and are often (but not always) located in the outskirts of cities and not in run-down inner-city areas (E.K. Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Lyngstad and Sleutjes2018; Costa & De Valk, Reference Costa and Valk2018; Musterd, Reference Musterd2005; Quillian & Lagrange, Reference Quillian and Lagrange2016).

For a long time, the European discourse on these neighborhoods centred on social inequalities, or ‘disadvantages’ (Veldboer et al., Reference Veldboer, Kleinhans and Duyvendak2002). However, since the beginning of the millennium, ethnic diversification has played an increasingly prominent role in the political debate. Political elites express concerns that large scale immigration from non-Western countries undermines social cohesion and unity (Escafré-Dublet & Lelévrier, Reference Escafré‐Dublet and Lelévrier2019). The ethnic turn of the debate can be seen against the background of growing global migration. Urban geographers have documented increasing levels of ethnic residential segregation in cities across Europe (Lichter et al., Reference Lichter, Parisi and Ambinakudige2020). Tumultuous events – violent conflicts between natives and persons of immigrant backgrounds in Britain; occasional riots in France, Britain, Denmark, Germany and Sweden; and religiously motivated terrorist attacks in Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Sweden and the US – are commonly viewed as triggering factors (Cantle, Reference Cantle2001; Stehle, Reference Stehle2012).

From some theoretical perspectives, the debate about ethnic diversity is misguided. The fact that many residents in vulnerable neighborhoods are global migrants does not, in itself, make those neighborhoods function differently (Sisson, Reference Sisson2021). Rather, neighborhood problems are rooted in social inequalities, structural discrimination and processes of territorial stigmatization (Hancock & Mooney, Reference Hancock and Mooney2013; Kirkness & Tijé-Dra, Reference Kirkness and Tijé‐Dra2017). In this line of reasoning, ethnic diversification is exploited by political leaders taking advantage of the majority population's prejudices (Slater, Reference Slater2018).

However, other theoretical perspectives suggest that migration-driven ethnic diversity may introduce neighborhood dynamics that are unprecedented in Western democracies. One contributing factor is the compositional difference of these neighborhoods. Compared to other disadvantaged areas, a disproportionate number of residents have experienced corrupt governments in their countries of origin (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Bowen and Nielsen2015; Sapiro, Reference Sapiro2004), adhere to differing cultural codes and political values (Inglehart & Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005), possess limited human capital in the new country (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Dagevos and Engbersen2017) and are more likely to encounter discriminatory behaviour (Zschirnt & Ruedin, Reference Zschirnt and Ruedin2016).

Other potentially differential factors are contextual and tied to the specific place. Differences from other neighborhoods may arise from inequalities in public goods provision, the behaviours of neighbors and subcultures that develop due to the neighborhood being a partly isolated arena of social interaction (Graham, Reference Graham2018; Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Morenoff and Gannon‐Rowley2002). For example, global migration can bring together groups with a shared but conflictual history in their region of origin (e.g., Muslims and Christians from the Middle East) as well as groups with no previous experience of co-existence (e.g., Somalis and Poles). Research on diversity and local social trust demonstrates that achieving cohesion in such contexts is challenging (Dinesen et al., Reference Dinesen, Schaeffer and Sønderskov2020).

Based on our review of the literature and consultations with country experts,Footnote 2 we propose that the ethnically charged political discourse on vulnerable neighborhoods is most pronounced in eight European countries, many of which belong to the group referred to as ‘old host countries’ (Zapata-Barrero & Triandafyllidou, Reference Zapata‐Barrero and Triandafyllidou2012): Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the UK. In other countries with recent inflows of non-Western immigrants, such as Austria (Friesenecker & Kazepov, Reference Friesenecker and Kazepov2021) and Italy (Costarelli & Mugnano, Reference Costarelli and Mugnano2018), the ethnic turn of the debate is less pronounced.

There is currently no objective criterion universally accepted for identifying politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods within a country. Wacquant (Reference Wacquant2008) offers illustrative examples such as the Mirail housing complex in Toulouse, Neukölln in Berlin, Saint Paul in Bristol and Bijlmer in Amsterdam. According to Pinkster et al. (Reference Pinkster, Ferier and Hoekstra2020), these neighborhoods constitute a ‘shortlist’ that are nationally – and sometimes internationally – recognized. A more concrete guideline proposed by Ireland (Reference Ireland2008) involves the presence of government support programs aimed at neighborhood development. While not all neighborhoods receiving government assistance fit our conceptualization of politicized and vulnerable, those that do are consistently targeted by such programs.

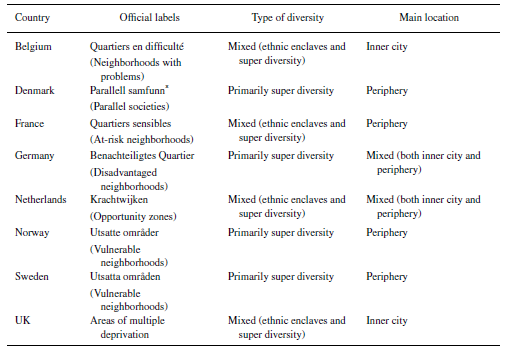

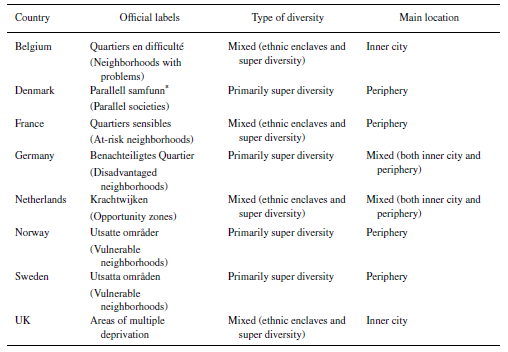

Table 1 lists the official labels for neighborhoods from the countries characterized by the most pronounced ethnically coloured debates on vulnerable neighborhoods. All labels indicate the outsider status of the neighborhoods, which is another distinguishing factor.

Table 1. Country-specific characteristics of European politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods

Before 2021, the official label was Gettos (Ghettos).

Note: Experts are listed in Appendix 1 in the Supporting Information

Our aim is to outline four key factors that characterize politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods across Europe: low socio-economic status, a significant proportion of ethnic minorities, targeted government programs and neighborhood labels that carry outsider connotations. While these factors are central, it is essential to acknowledge two key points. Firstly, there is a need for further research to develop precise measures that accurately capture the politicized and vulnerable nature of neighborhoods.

Secondly, European neighborhoods exhibit significant diversity. Table 1 identifies two potentially influential neighborhood characteristics that vary between countries: the type of diversity and the location. ‘Super diversity’ refers to neighborhoods with a high presence of multiple ethnic groups, while ‘ethnic enclaves’ are dominated by specific ethnic communities (Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2017; Vertovec, Reference Vertovec2007). Location distinguishes between neighborhoods situated in historic city centres with aged infrastructure and those developed in the outskirts during the 1960s and 1970s (Sisson, Reference Sisson2021; Vanneste et al., Reference Vanneste, Thomas and Vanderstraeten2008).

Politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods in Sweden

The empirical study covers Sweden. Given the country's long-standing reputation as ethnically homogeneous, the case selection may seem surprising. However, because of liberal migration policies, the rapidly growing Swedish population – up from 9 million to 10.5 million since the turn of the millennium – has become one of Europe's most ethnically heterogenous. Currently, 20 per cent of the population is foreign-born, half of which originates from non-European countries. Syria, Iraq, Iran and Somalia are the most common non-European countries of origin; former Yugoslavia, Finland and Poland are the most common European sender nations.

In the diversifying Swedish population, levels of ethnic and socioeconomic residential segregation are high (E.K. Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Lyngstad and Sleutjes2018). Many immigrants with limited socioeconomic resources reside in anonymous and standardized neighborhoods built under the Million Homes Program that ran from 1965 to 1974 (R. Andersson, Reference Andersson2007). These neighborhoods are typically diverse in the backgrounds that underlie traditional groups: in addition to nationality, they are also heterogenous in terms of ethnicity (e.g., Kurds and Assyrians), religion (Sunni and Shia Muslims, and Orthodox Christians) and race (visible and non-visible minorities). Native Swedes have a limited and declining presence in the neighborhoods (Bråmå, Reference Bråmå2006). In many neighborhoods, ‘Swedish-Swedes’ are not even the largest ethnic group. It is among these places that Sweden's politicized and vulnerable are found.Footnote 3

Compared to most other countries, Sweden has transparent criteria for exactly which neighborhoods qualify. Since 2015, the Swedish Police Authority has listed which specific neighborhoods are characterized by socioeconomic disadvantage, ethnic segregation and high levels of criminal activity.Footnote 4 Neighborhoods on the list are classified as ‘vulnerable’, ‘at risk’ or ‘particularly vulnerable’. In the last category, the problems are so severe that residents refuse to testify in criminal cases and there are parallel social governance structures, all of which hinder everyday policing. The police list has been criticized for relying on subjective criteria, for being stigmatizing and for neglecting other disadvantaged neighborhoods, but it undoubtedly plays a central role in the national political discourse (Gerell et al., Reference Gerell, Puur and Guldåker2022).

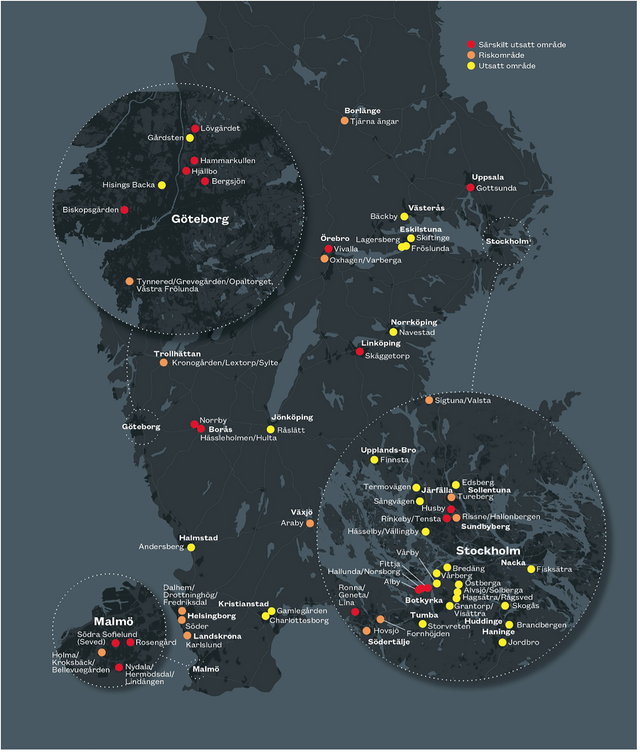

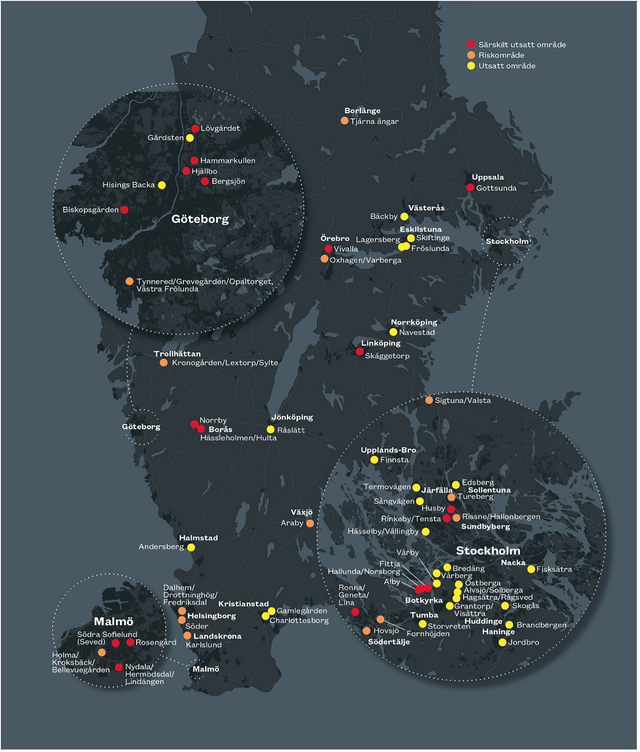

The list from 2021 identifies 61 vulnerable neighborhoods, 19 of which are ‘particularly vulnerable’.Footnote 5 Most places on the list are in the metropolitan areas of Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö but are also found in smaller cities in southern and central Sweden (see Figure 1). About 6 per cent (600,000 individuals) of the Swedish population resides in these neighborhoods (Global Village, 2019).

Figure 1. Swedish vulnerable neighborhoods as identified by the police authority

Note: Yellow = Vulnerable; Orange = At risk; Red = Particularly vulnerable.

Source: The Swedish Police Authority

Preferences for local social order

Social order refers to the way that society is organized; the social structures that members of a society maintain, and the expectations people have about other people's behaviour (Elster, Reference Elster1989; Hechter & Horne, Reference Hechter and Horne2003; Wrong, Reference Wrong1994). As with the related concept ‘social cohesion’, there is no generally accepted set of survey indicators that captures beliefs about the phenomenon (Schiefer & van der Noll, Reference Schiefer and van der Noll2017). In the absence of standardized measures, we have developed an original survey instrument intended to capture residents’ preferences for local social order.

To function in our hard-to-reach-population, we wanted the survey instrument to fulfil several side conditions: items should be relevant to residents; items should cover conditions on the ground in the neighborhood and at the same time connect to the national political discourse; and, to motivate participation in the survey, items should be solution-oriented and not contribute to respondents’ feelings of living in a stigmatized place.

Our suggested survey instrument captures beliefs about local social order in an indirect way. Respondents are asked to evaluate a set of reform proposals for neighborhood development with the following prompt: ‘How important would you consider the following in making [name of the neighborhood] a better place?’ The logic is that residents’ preferences for reform proposals will reflect the gravity of the problem being addressed; serious problems in the neighborhood are given higher priority, while problems perceived as less serious are given lower priority.

The validity of the measurement depends on the reform proposals giving a comprehensive picture. In a pilot survey, we included a list of reform proposals raised during our initial contacts with civil society organizations and authorities in one of the neighborhoods (see below).

To ensure that reform proposals connected with the neighborhood's issues, we invited further reflections with an open-ended question, which was repeated in most subsequent survey waves: ‘In your view, what would be the most important improvement in [name of neighborhood]?’ We used responses to the open-ended question to incrementally adjust the list of reform proposals. As documented in the online Supporting Information (Appendix 4), each proposal is matched by the residents’ reflections captured in response to the open-ended question. We also created a word cloud based on the open-ended responses, which is available in the SI (Appendix 5). The topics raised in the open-ended responses show considerable overlap with the concerns expressed in response to the closed-ended questions.

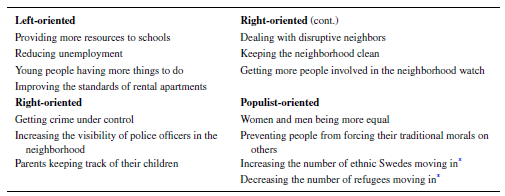

To connect the local with the national, we tie each reform proposal on the elite political discourse on vulnerable neighborhoods. Precisely, we associate each proposal with stylized left-oriented, right-oriented and populist-oriented ideological views on neighborhood reform (Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2017, 82–83; Sisson, Reference Sisson2021; Wacquant et al., Reference Wacquant, Slater and Pereira2014).

Left-oriented policy proposals stress government interventions to help residents overcome the consequences of social inequalities, territorial stigmatization and structural discrimination. Right-oriented policy proposals emphasize interventions that help residents take personal responsibility for neighborhood changes (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Nie & Andersen, Reference Nie and Andersen1974; Treier & Hillygus, Reference Treier and Hillygus2009). Populist-oriented proposals attribute neighborhood problems to cultural differences arising from large-scale migration related to honor cultures and clan-based societies. These proposals underline the need to reject traditional cultural patterns and embrace a modern European lifestyle.Footnote 6

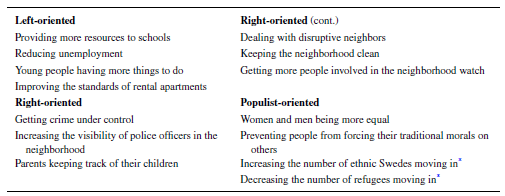

The full set of reform proposals that were put to the vulnerable neighborhood sample and to the nationally representative reference sample is shown in Table 2. Four proposals are associated with the idea that government should intervene to improve social infrastructures in the neighborhood (left-oriented proposals, in our classification). Items stress the importance of providing job opportunities and more resources to local schools, of improving the standard of rental apartments, and of ensuring that young people have meaningful things to do in their free time.

Table 2. Proposals to improve the neighborhood

Note: Question wording: ‘How important would you consider the following to make [Hjällbo/Bergsjön] a better place?’ (In the national sample, the reference object is ‘your neighborhood’). Response options: ‘Very important’, ‘Somewhat important’, ‘Neither important nor unimportant’, ‘Somewhat unimportant’, ‘Very unimportant’. Appendix 8 in the SI includes information on when specific items were asked.

* Item not asked in the national sample.

Six proposals represent ideas about personal responsibilities (right-oriented proposals). Items include ‘Keeping the neighborhood clean’, and ‘Parents keeping track of their children’. Under this heading, we have also placed the proposal ‘Getting crime under control’ with reference to that law and order is commonly regarded as a right-oriented value (Green-Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2007).

Finally, four proposals intend to capture concerns about cultural conflicts (populist-oriented proposals). Two items target the ethnic composition of the neighborhood and the need to reduce segregation (so that more native Swedes and fewer refugees move in). The two other items pertain to gender equality: ‘Preventing people from forcing their traditional morals on others’, a.k.a. morality policing, and the same underlying value expressed in positive terms: ‘Women and men being more equal’.

Structure of reform preferences

To answer our second research question about the structure of reform preferences, we draw on previous research on attitude structures and make inferences based on a set of complementary criteria: (i) dimensionality in support of reform proposals; (ii) over-time stability at the individual level; (iii) agreement across social groups; and (iv) comparison with a reference group. The complementary criteria have the additional benefit of identifying outcomes that disprove certain descriptive arguments, an intrinsic challenge for descriptive analysis (Gerring, Reference Gerring2012).

With dimensionality, we look for two alternative response patterns: either that support for reform proposals reflect the ideological divide in elite discourse (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992), or that support for reform proposals are a pragmatic reflection of lived reality in the neighborhood (Lane, Reference Lane1962; Wekker, Reference Wekker2019).

The elite reflection pattern prevails if reform proposals associated with the respective ideological camp goes together along one or more dimensions (e.g., Nie & Andersen, Reference Nie and Andersen1974). By implication, it means that the elite debate could account for reform preferences among residents. If the left-right perspective is dominant, proposals that stress state interventions likely will receive the strongest support because residents overwhelmingly vote for left parties (Oscarsson & Holmberg, Reference Oscarsson and Holmberg2013).Footnote 7

The alternative response pattern of lived reality prevails to the extent that residents align reform proposals from two or more elite camps. It would suggest that residents are pragmatic in their wish to solve a difficult local reality, and the contentious ideological debates are less relevant. This response pattern would be in line with qualitative studies from the US context, which finds that marginalized members of a society have meaningful and consistent policy attitudes but that these attitudes do not need to align with elite perspectives (Weaver et al., Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2019; Cramer & Toff, Reference Cramer and Toff2017).

Over-time stability in support of reform proposals evaluates attitude coherence temporally (Converse, Reference Converse and Apter1964). Individual level-stability is a demanding test considering that residents’ social and political characteristics – low socioeconomic status (SES) and low levels of political involvement – are well-known predictors of non-attitudes (Achen & Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2017; Converse, Reference Converse and Apter1964). The panel component in our data collection allows for an empirical investigation of this aspect.

Agreement between residents’ prioritizations shows whether there is a common understanding of local social order, or whether residents belonging to different social groups have different reform preferences. The analysis is descriptive, not explanatory. The key statistic is the predictive power of social characteristics that entails different social experiences. Precisely, if native origin, religious affiliation (Muslim or other), visible minority status (operationalized as Somali background) and gender strongly predict support for reform proposals, that will indicate that residents perceive local social order differently. For this paper, we focus on bivariate relationships and leave questions about intersectionality to future studies.

The comparison with a reference group provides further nuance to the description. By comparing levels of support for reform proposals between our target sample and residents in presumably better-functioning neighourhoods elsewhere in the country, we can determine whether concerns about local social order are more pronounced in politicized neighborhoods and identify specific aspects that deviate the most. Additionally, comparing the rank-ordering of reform proposals allows us to assess whether residents in politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods share the same priorities for a well-functioning neighborhood as other residents across the country.

Method

The survey

Working locally with a personal presence was key in our efforts in overcoming the problems of surveying a hard-to-reach population. For practical reasons, this approach presupposes a concentration in a small number of geographical locations. We conducted our survey in Hjällbo and Bergsjön, two neighborhoods in Gothenburg that are classified by the Police Authority as ‘particularly vulnerable’, the most serious category. Figure 1 shows their location northeast of the city centre, together with six other neighborhoods in the city that are on the police list.

The criterion for case selection was practical. After consultation, local authorities suggested that Hjällbo was a suitable place to start since there were currently no other major studies taking place there. Following a stepwise sampling logic, theoretical sampling (Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967), after completing the Hjällbo-study, we moved on to Bergsjön, which differs by being governed by another local political unit. Results from the two neighborhoods are similar, and we have no reason to believe that Hjällbo and Bergsjön differ systematically from other ‘particularly vulnerable’ neighborhoods in Gothenburg and nationally. For instance, the demographic profile and voting patterns in local and national elections are similar in various parts of Sweden (Global Village, 2019).

A journey by tram from the city centre to Hjällbo takes 15 minutes and to Bergsjön 40 minutes. Each neighborhood has a registered population of about 8,000. In terms of diversity, more than 90 per cent of residents are foreign-born or have at least one foreign-born parent. Except for native Swedes, the largest national groups are Iraqi, Bosnians, Somali and Syrians, but, as in most diverse neighborhoods in Sweden, more than 20 other countries of origin are represented.

Proceedings

We conducted a mixed-mode panel survey between April 2017 and January 2020, targeting residents aged 16 and older in the two neighborhoods. Initial contacts with residents were face-to-face, where they were asked if they wanted to participate in a study about their neighborhood. About 40 per cent of the respondents were recruited through probability sampling and the rest through various types of convenience sampling. Just over 80 per cent of the interviews were conducted in Swedish, with Arabic as the second most common language (10 per cent of the interviews). The remaining interviews were conducted in Somali (5 per cent) and English (5 per cent). Appendix 2 in the SI provides an account of proceedings, which differed somewhat between the Hjällbo survey and the follow-up survey in Bergsjön.Footnote 8

At the end of the recruitment interviews (t1), respondents were invited to online interviews. Those who agreed provided us with contact information and were subsequently sent invitations to an online survey either as e-mails or text messages, depending on their preference. All in all, we made 3,473 personal contacts (which corresponds to 28 per cent of the registered target population), of whom 2,286 participated in the face-to-face interviews (66 per cent of the contacted); of these, 1,372 agreed to further online interviews (60 per cent of the interviewed), with 814 participating in at least one panel wave (36 per cent of the interviewed and 59 per cent of those who agreed to further interviews).

The questions about reform proposals for neighborhood development were asked in all surveys except the face-to-face recruitment survey (t1). In other words, we have measures on these opinions at t2, t3 and t4, and the 814 respondents in the online survey panels form the primary basis for this paper.

As documented in the SI, our total sample compares well with official register data from the Gothenburg municipality. Interestingly, we find no systematic difference based on sampling method (convenience versus probability). Looking at specific demographic categories, we succeeded in recruiting residents with foreign backgrounds whereas women and the middle aged are slightly overrepresented. The biggest discrepancy concerns education in the online sample (t2, t3 and t4), as residents with lower education levels are underrepresented (38 per cent in the register data compared to the 10 per cent in the online sample).Footnote 9

As can be expected given panel attrition, the web-survey sample is also younger, more native, and more male than the recruitment sample. However, there is only a small attrition bias. Importantly, there is no evidence that institutional trust, social trust or neighborhood identification as expressed in the recruitment interview are associated with the likelihood of dropping out of the panel (Appendix 6 in the SI).

In summary, the results presented below stem from a sample that skews towards individuals with higher education levels but is fairly representative regarding other crucial demographic factors. Data collection for the national reference sample was conducted by the private polling company Novus. This survey took place in April 2021 as part of the online Sweden Citizen Panel, which utilizes a probability sample of the voting-age population (n = 1,028; participation rate = 58 per cent).Footnote 10

Results

What is needed to improve the social order?

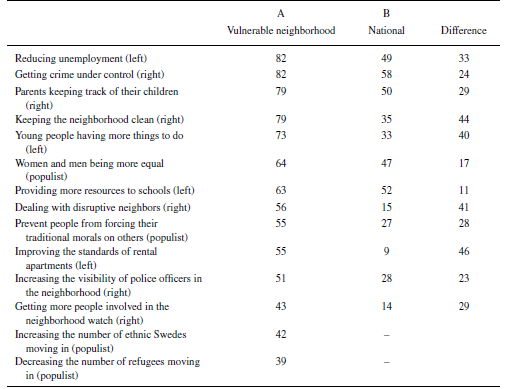

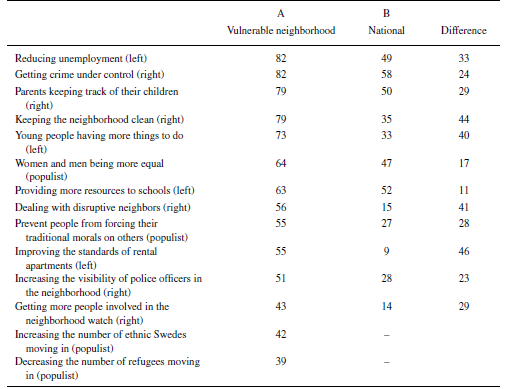

Column A in Table 3 presents the overall support for reform proposals in the local neighborhood sample. Five proposals are considered very important by a clear majority of respondents (73 to 82 per cent), three proposals are prioritized by less than half of the respondents (39 to 43 per cent selected very important) and support for the remaining six proposals fall between these two ranges (51 to 64 per cent selected very important). In other words, neighborhood residents are not mindlessly agreeing to all proposals. If they did, it would be an indication of either non-attitudes or a failing survey instrument.

Table 3. Support for improvement proposals in the vulnerable neighborhood sample and the nationally representative reference sample (percent very important)

Note: The number of pooled responses for the vulnerable neighborhood sample varies from 468 (‘Standard of rental apartments’) to 1,437 (‘Young people’). The national representative number of respondents is 1,028. Detailed information is available in the SI, Tables S7 and S8. Two-sample t tests show that all mean levels are higher in the vulnerable neighborhood sample compared to the national sample at p < 0.01.

Regarding substance, residents give priority to both left-oriented and right-oriented reform proposals. The five highest prioritized reform proposals concern unemployment (left), criminality (right), keeping it clean (right), parental control over kids (right) and young people having more things to do (left).

Proposals associated with populism are generally of lower priority. For example, having more ethnic Swedes and fewer refugees moving into the neighborhoods ranks lowest on the list. Thus, although these propositions would reduce ethnic segregation in society, there seems to be limited demand for more ethnic Swedes in the surveyed neighborhoods.Footnote 11 The two most supported populist-oriented proposals are, working towards increased gender equality and putting a stop to the morality police that try to force traditional values on others, which were ranked 6 and 9 out of the 14 measures, respectively.

Furthermore, a left-oriented reform proposal associated with physically deteriorating neighborhoods – improving the standards of rental apartments – has relatively low priority (55 per cent ‘very important’). This aligns with the observation from housing research that housing standards in Sweden's vulnerable neighborhoods are high in comparison with most other European countries (R. Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Bråmå and Hogdal2007).

Drawing inference from these observations to address our first research question, residents perceive the most significant issues in their neighborhood to be high unemployment and crime rates, parents’ inability to control unruly young people and a littered physical environment. This reflects a form of deficient social order reminiscent of disadvantaged neighborhoods throughout history (Wacquant, Reference Wacquant2008).

The structure of reform preferences

Dimensionality

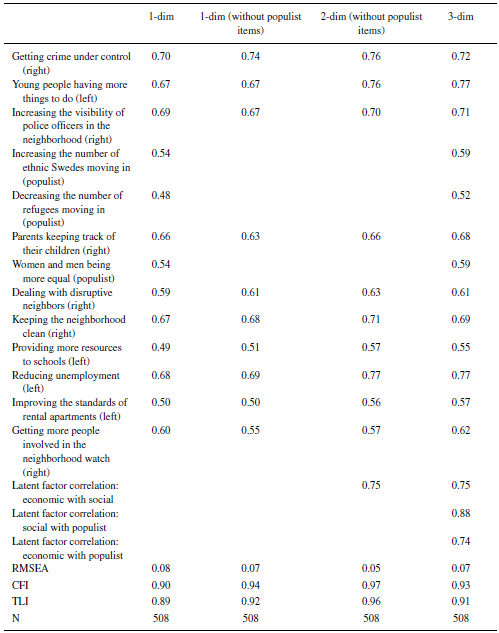

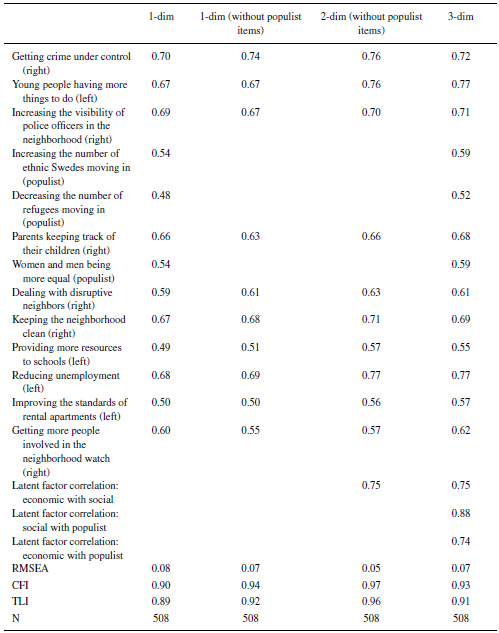

The pattern that both left-oriented and right-oriented reform proposals are highly prioritized is most compatible with the lived reality perspective, according to which residents’ perceptions of neighborhood problems are a pragmatic, non-ideological, reflection of conditions on the ground (Wekker, Reference Wekker2019; Lane, Reference Lane1962). We rely on confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess if the same pattern is found at the level of individuals.

Considering the polarized character of elite political discourse, we looked for evidence that support of reform proposals falls along a left-right dimension so that left-oriented proposals that involve broader government interventions are systematically differentiated from right-oriented proposals that put the onus on individuals. We also looked for evidence that populist-oriented proposals that stress migration based cultural differences form a separate dimension.

The results from a series of one-, two- and three-dimensional model specifications are presented in Table 4. The overall conclusion is that residents reject left-right thinking about the concerns of their neighborhoods. The best case for a left-right divide is a two-dimensional model that separates between the welfare proposals that are in the economic dimension and the proposals that fall into the social dimension like thoughts on crime (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Treier & Hillygus, Reference Treier and Hillygus2009).Footnote 12 The better fit statistics of the two-dimensional model compared to the one-dimensional indicates that people who agree to one type of items are not simply agreeing to both types. However, it is important to acknowledge that the two latent factors in the model are correlated at 0.75. This means that people who support proposals that we classify as left-oriented also tend to support right-oriented proposals, on average.

Table 4. Confirmatory factor analysis of improvement proposals, vulnerable neighborhood sample at t2

Note: Models are estimated in Mplus 8.7 using WLSMV. Of the proposals in Table 3, the following item was not asked at t2: Preventing people from forcing their traditional morals on others (populist). The general tendencies from t2 are also found at t3 and t4.

Moreover, including populism as an additional dimension does not improve model fit (Caughey et al., Reference Caughey, O'Grady and Warshaw2019). In fact, the best fit (RMSEA = 0.05) is achieved when populist items are left out of the model entirely. This suggests that, while there is an elite-level discourse about culture, ethnicity, and adherence to Swedish norms, it has not taken hold among residents since such reform proposals are not integrated into their thinking about neighborhood problems.

Summing up, the analysis of dimensionality confirms previous findings: residents perceive differences between traditional left and right proposals, but they primarily care about whether a policy proposal will work in their neighborhood, not about being ideologically consistent. According to them, building a stronger social order in the neighborhood will require both government interventions and more orderly behaviour from the people living there.

Attitudinal stability

If reform preferences reflect genuine attitudes, over-time stability between panel waves should be noticeable. Since panel waves were separated by, on average, 6 months, there was time for various types of experiences to influence residents’ preferences. If the survey instrument picks up random or easily malleable preferences for reform, over-time stability will be low.

However, our analysis of stability of latent traits shows high levels of stability across panel waves. If we model the observed indicators as measuring one latent dimension (the lived reality dimension discussed above), the correlation is 0.87 (p < 0.001) between t1 and t2, 0.87 (p < 0.001) between t2 and t3, and 0.73 between t1 and t3 (p < 0.001). Results are identical if we instead assume the two-factor model that is the closest approximation of a viable left-right divide in our material. The over-time correlation for the economic dimension is 0.85 (p < 0.001) between t2 and t3, 0.80 (p < 0.001) between t3 and t4, and 0.68 (p < 0.001) between t2 and t4. The over-time correlation for the social dimension is 0.90 (p < 0.001) between t2 and t3, 0.87 (p < 0.001) between t3 and t4, and 0.78 (p < 0.001) between t2 and t4.

That is, regardless of how we measure the factors, the stability is high over time. Similarly, individual items (not just scales) also correlate predictably over time. Among the nine items that were asked in all three waves (see Table S7 in the SI), the average over time correlation is 0.38 (SD = 0.14). This includes correlations between t1 and t2, t2 and t3, and t1 and t3. The relative stability over time is further evidence that thoughts on what is needed to improve social order are not just made up on the spot.

Agreement across social groups

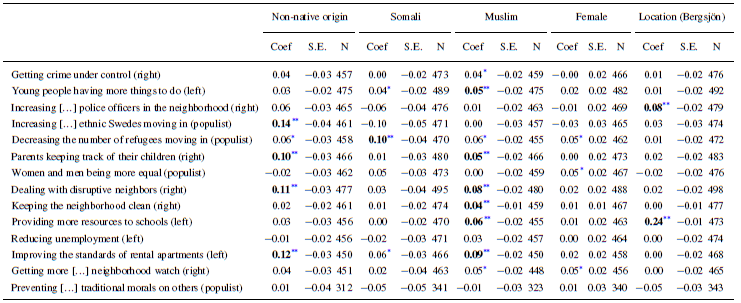

Are reform preferences homogenous among neighborhood residents? To answer this descriptive research question, we examine four social group characteristics that might lead to differential outlooks on problems in the neighborhood. Natives and non-natives differ in their social trust in others and might have been socialized into having different expectations about orderly behaviour (Dinesen et al., Reference Dinesen, Schaeffer and Sønderskov2020). Visible minority-status is often associated with experiences of discrimination, which might spill over on perceptions of the neighborhood (Hope et al., Reference Hope, Gugwor, Riddick and Pender2019). Correspondingly, Muslims face particular obstacles in countries of Christian heritage (Adida et al., Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016). Finally, the relationship between men and women often come to a head in vulnerable neighborhoods, which can impact preferences (Hojat et al., Reference Hojat, Shapurian, Foroughi, Nayerahmadi, Farzaneh, Shafieyan and Parsi2000).

Table 5 displays the bivariate relationship between social group characteristics and support of reform proposals using OLS regression. All variables are coded 0–1. The social characteristic variables are all dummy coded. To compensate for the risk that the many estimates will yield chance findings, we choose p < 0.01 as our threshold for statistical significance.Footnote 13 To evaluate how large a difference is, we rely on Cohen's d.

Table 5. Social group characteristics and support for reform proposals, bivariate analysis (OLS)

Note: Entries are bivariate OLS regression coefficients. All questions were asked at t2 except the question on morality police, which was asked at t3. Variables are scored 0–1. We measure non-native origin as having one or two parents who were born abroad. Somali is measured with a question about the respondent's ethnic background and signifies that the individual has Somali background. Muslim is operationalized with a question about the respondent's religious affiliation. Sex (female) is operationalized with interviewer observations at the face-to-face survey (t1). Location (Bergsjön) is a dummy variable for one of the two disadvantaged neighborhoods in the data. The other neighborhood, Hjällbo, is the baseline.

** p < 0.01 (and in bold), * p < 0.05. We focus on coefficients below the 0.01 threshold due to the risk of chance-findings. A multiple regression version of this table is available in the SI, Table S9.

In almost 20 percent of the bivariate relationships examined (13 of 70), we observe statistically significant group differences (p < 0.01). Out of those, nine are categorized as medium according to Cohen's d, two are large (Non-native origin and ‘Parents keeping track of their children’, and ‘Improving the standards of rental apartments’) and one is very large (neighborhood differences in the need to improve schools). Of the factors that seem to matter more frequently, Muslims differ from non-Muslims (6 of 14 cases) and non-natives from natives (4 of 14). There are fewer distinct differences related to neighborhood (2 of 14), visible minority status (1 of 14) and gender (0 of 14).

Regarding specific reform proposals, the most widespread disagreement concerns the need to provide more resources to schools (2 of 5 groups make different assessments) improve the standards of rental apartments (2 of 5) and parental responsibility (2 of 5), and dealing with disruptive neighbors (2 of 5).

Clearly, there are some noteworthy differences in residents’ support of reform proposals in the neighborhood. However, differences are hardly so profound as to reflect parallel perceived realities. It is a reasonable approximation, we maintain, that neighborhood residents share a similar understanding of what is needed to improve the local social order.

Comparison with a representative national sample

Column B in Table 3 shows how individuals from a nationally representative reference sample evaluate the same set of reform proposals with respect to their own residential neighborhoods. Comparing the two frequency distributions, residents in the vulnerable neighborhood sample see a greater need for local reform. Each reform proposal is ascribed more importance by these residents than by people living in supposedly better-functioning neighborhoods. The differences are particularly pronounced for the proposals to keep the neighborhood clean (a 44-percentage point gap), deal with disruptive neighbors (a 41 percentage-point gap) and provide meaningful activities for young people (a 40 percentage-point gap).Footnote 14 Thus, assuming that the point of providing meaningful activities to the youth is to keep them off the street, residents in politicized neighborhoods are particularly concerned with strengthening the local social control of people.Footnote 15

However, as important as emphasizing differences, the ranking of reform proposals is similar in both samples (Spearman's rho = 0.84; p < 0.01). That is, regardless of location, people have similar priorities about what their neighborhoods need the most. Overall, the results suggest that residents in vulnerable neighborhoods and in other areas have the same preferences for neighborhood development, with the primary difference being the perceived urgency for reform in their respective neighborhoods.

Conclusion and discussion

This paper draws attention to local neighborhoods that are the object of ethnically coloured political debates across European welfare states. We offer a definition of this population, demonstrate that it is possible to conduct quality surveys with residents in vulnerable neighborhoods, and develop a measurement that allows us to assess what residents in two Swedish neighborhoods think should be done to improve the social order in their neighborhood.

Inferring from this measurement, residents perceive that neighborhood problems are about unemployment, crime, littering, parents who do not take responsibility for their children and, generally, a lack of social control between people. These are problems that recur in discussions about disadvantaged neighborhoods (Wacquant, Reference Wacquant1993). However, problems emanating from immigration and cultural conflicts are given less attention and are less integrated into residents’ beliefs about their neighborhood. Thus, it appears that residents in Sweden's politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods are not very preoccupied with the issues of cultural clashes and failed integration that figure prominently in national debates in the age of global migration (Dancygier & Margalit, Reference Dancygier and Margalit2020; Green-Pedersen & Otjes, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Otjes2019).

In a direct comparison with a nationally representative reference sample who evaluate the same set of reform proposals about their own neighborhood, we find important similarities. Although vulnerable neighborhood residents see a much greater need for reform in their neighborhood, the ranking of reform proposals is close to identical in the two samples. The differences should not be denied – for example, questions about fighting morality police and having more natives moving into the neighborhood only apply to vulnerable neighborhoods – but in terms of respondents’ views about how neighborhoods should ideally function, the similarities are greater than the differences.

In terms of policy implications of the findings, it is notable that neighborhood residents Favor reform proposals associated with both left-oriented and right-oriented ideological views in our categorization. Specifically, residents see a need for both government intervention (for example, reducing unemployment) and for more personal responsibility (for example, increasing parental control over kids and reducing littering). We conclude that residents are more interested in what works in their neighborhood than in remaining ideologically consistent according to the traditional understanding of the left and right, and that an accurate summary of residents’ views on neighborhood development would include both left-oriented ‘do-something attitudes’ and right-oriented ‘shape-up attitudes’. These findings suggest that residents’ perceptions of social order differ from political and theoretical perspectives that exclusively attribute neighborhood problems to structural discrimination and social inequalities (Hancock & Mooney, Reference Hancock and Mooney2013; Kirkness & Tijé-Dra, Reference Kirkness and Tijé‐Dra2017).

Residents’ pragmatic stance is noteworthy, considering that residents in Sweden's vulnerable neighborhoods overwhelmingly support left-leaning parties; in the national elections in 2018, over 70 per cent voted for a party on the left. This discrepancy suggests that parties to the left are not fully responsive to their wishes and views and that, perhaps, parties to the right fail to capitalize on favourable public opinions (Dancygier, Reference Dancygier2017). More generally, the results raise questions about the lack of democratic responsiveness. Why does elite discourse fail to acknowledge the pragmatic character of public opinion among the residents?

In addition to the matters discussed this far, our findings have bearing on the long-standing debate on the quality of public opinion and public ignorance (Achen & Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2017; Converse, Reference Converse and Apter1964). Residents’ attitudes toward neighborhood development are not only pragmatic and solution-oriented but also structured and stable at the level of individuals. That attitudes are structured and stable may be surprising, as vulnerable neighborhoods are places where the traditional political science perspective would expect lower levels of citizen competence. After all, the residents are not as politically engaged and have comparatively low SES. But, by asking questions that connect to the neighborhoods’ issues, we can provide new evidence on a fundamental concern about democratic competency.

The most pressing limitation of our study concerns the generalizability of empirical findings. Because we only surveyed vulnerable neighborhoods in Sweden, we lack information on the conditions in other European countries. Since findings are recognizable from disadvantaged neighborhoods throughout history, there is reason to believe that the main features of the Swedish residents’ perceptions of social order can also be found in other country contexts, but more studies are needed, for example in neighborhoods with a clear character of ethnic enclaves rather than superdiversity as in the Swedish case.

Our study reveals ways to advance research in this field. The conceptualization of the population of Europe's politicized and vulnerable neighborhoods helps to identify relevant neighborhoods to study. And, to overcome the difficulty of surveying certain populations, we believe that our local approach characterized by a strong personal presence, monetary incentives, and surveys in several languages would be effective in other national contexts. Residents in Europe's vulnerable neighborhoods deserve attention in future research for both theoretical and substantive reasons. The neighborhoods in which they live are not only politicized places; they are also social laboratories for many urgent issues of our time.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript has been greatly improved thanks to the feedback from Henning Finseraas, Kristen Kao, Andrej Kokkonen, Nazita Lajevardi, Anders Lidström, Elin Naurin, Anders Sundell, and Kim Sønderskov. In addition, we were helped by the comments and suggestions from the reviewers and the editors. We are also thankful for the response at the research workshop of Management and Public Administration at the University of Konstanz in 2023 and at the ECPR general conference in 2021 where early drafts were presented. Sophie Cassel at the SOM Institute provided programming and data management expertise. Josefine Magnusson assisted with the Supplemental Material. Moreover, we want to express our gratitude to the following country experts on vulnerable neighborhoods: Igor Costarelli (Italy), Pascal De Decker (Belgium), Gabriella Elgenius (UK), Henning Finseraas (Norway), Helmut Hirtenlehner (Austria), Elisabeth Ivarsflaten (Norway), Bernhard Kittel (Austria), Clemens Kroneberg (Germany), Ann-Kristin Kölln (Germany), Lieven Pauwels (Belgium), Kim Mannemar Sønderskov (Denmark), Jacques Teller (Belgium), Frank Weerman (the Netherlands) and Per-Olof Wikström (UK).

Data availability statement

Replication files (data and code) are available under the online section Supporting Information. Five files are for Mplus and three for Stata.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix 1. Sources for the country classification in Table 1

Appendix 2. Proceedings vulnerable neighborhoods survey

Appendix 3. National origin of residents in the surveyed neighborhoods (register data)

Appendix 4. Policy proposals as reflected in open-ended responses

Appendix 5. A word cloud based on open-ended responses

Appendix 6. Representativity and panel attrition: vulnerable neighborhood sample

Appendix 7. Expressions of support for ethnic mixing in open-ended responses

Appendix 8. Policy proposals by survey

Appendix 9. Additional analysis

Appendix 10. Research ethics

Supporting Material