INTRODUCTION

In contexts of conflict where the sovereign authority of the state is contested, civilians in opposition groups may boycott state-provided public goods and social services as a means to protest the state’s claim to sovereignty. Evidence from East Jerusalem suggests that civilians make different choices with respect to different goods and services. Namely, Palestinians in East Jerusalem—the majority of whom perceive the Israeli state to be illegitimately occupying the city—are willing to accept select state-provided goods and services, but will opt-out of engaging with others. If Palestinians opt-out of the state-provided option, they may instead seek a solution within the Palestinian community or simply go without. As a Palestinian civil society leader succinctly articulated when interviewed,

Going to court for example—people are not satisfied with it but sometimes they must do that. Calling the police is out of the question. The majority won’t do that. Health services? No questions. These are fine. The national insurance institute? People will go there. (Interviewee 28. 2022. Palestinian Civil Society Organization Employee. Interviewed by Author, East Jerusalem).

To unravel the puzzle of selective claim-making in East Jerusalem and beyond, in this article I ask two related questions. First, which services are most commonly engaged with and which are most likely to be avoided? Second, how do Palestinians in East Jerusalem determine which services to engage with and which to avoid?

Importantly, the puzzle of Palestinian engagement with the Israeli state highlights an underexplored dynamic within the literature on claim-making and quotidian political participation. While the claim-makingFootnote 1 literature has, both implicitly and explicitly, acknowledged that claim-making behavior is influenced by the type of good or service sought, additional theorizing is required to explain why individuals make different claim-making choices with respect to different sectors, as is seen in the East Jerusalem case. The majority of the claim-making literature has thus far focused on explanations for the propensity of particular individuals to make claims on the state, yet theoretical justifications for a single individual’s divergent choices across sectors remain underexamined. According to the extant literature, claim-making is thought to be made more likely by residing in socially homogeneous neighborhoods (Tsai Reference Tsai2007), a greater density of party brokers in one’s neighborhood (Auerbach Reference Auerbach2016), increased visibility of the state in one’s neighborhood (Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018), and positive policy feedbacks whereby individuals who gain from the state via distributive policies are more likely to become active citizen claimants in the future (Kumar Reference Kumar2022). Notably, the sociological literature on documented and undocumented immigrant help-seeking in the US cites fear, shame, and immigration status as key factors determining whether predominantly Latino/a/x individuals seek help from government agencies (Chavez Reference Chavez2012; Reina, Lohman, and Maldonado Reference Reina, Lohman and Maldonado2014; Zadnik, Sabina, and Cuevas Reference Zadnik, Sabina and Cuevas2016). Several works investigate the determinants of particular types of claim-making, such as filing legal claims in pursuit of social welfare goods (e.g., Taylor Reference Taylor2020), or making tax payments (e.g., Balán et al. Reference Balán, Bergeron, Tourek and Weigel2022; Bodea and LeBas Reference Bodea and LeBas2016; Masaki Reference Masaki2018). Others comparatively differentiate between manners of claim-making or the types of goods and services sought. Notably, Kruks-Wisner (Reference Kruks-Wisner2018) measures numerous “repertoires” of claim-making while Kramon and Posner (Reference Kramon and Posner2013) find that governments’ distributive targeting of ethnic groups varies depending on the good or service in question. Thus, the East Jerusalem case contributes to the literature’s burgeoning focus on sector-level differences in claim-making behavior by developing and testing a theory to explain variation in a single individuals’ claim-making behavior across sectors.

In this article, I draw on data from 55 in-depth interviews conducted during 11 months of fieldwork in 2022 as well as original survey data from a representative sample of East Jerusalem’s 19 neighborhoods to (a) quantify patterns of variation in individuals’ engagement with the state across sectors and (b) develop and test a theory concerning how individuals make choices between different types of goods, services, and institutions (hereafter, GSIs) in contexts of contested sovereignty. I argue that in contexts of contested sovereignty, civilians’ choices with respect to the state are a function of civilians’ perceptions of the state’s (il)legitimacy. Namely, civilians will avoid engagement wherever possible with state sectors that are perceived to explicitly affirm the state’s claim to sovereignty, without sacrificing essential services. In particular, civilians will avoid GSIs that reinforce the state’s claims to monopoly, such as a monopoly on the means of coercion in the case of the police and judiciary, or a claim to monopoly on the official historical narrative expressed in public school curricula. However, in the absence of viable local alternatives, civilians will accept necessary public services such as water and sanitation, having conferred upon the state a limited degree of legitimacy to provide basic resources. Further, civilians may go without non-essential services in an effort to avoid affirming the state’s claim to sovereignty. In sum, the degree and manner in which civilians engage with the state is colored by civilians’ perceptions of the state’s legitimacy, or right to rule, at the sector level, and whether engagement with a particular sector requires implicit or explicit recognition of the state’s claim to sovereignty over the disputed territory.

I evaluate this argument by considering the case of East Jerusalem. In East Jerusalem, Palestinians use the word normalization, or in Palestinian Colloquial Arabic tatbi‘a, to describe actions which legitimate the Israeli state’s sovereign presence in East Jerusalem and across all territories of historic Palestine. As the logic goes, engaging with any of the Israeli state’s GSIs legitimates the state’s authority to govern. However, while all manners of engagement may technically be classified as normalization, in practice only select forms of engagement merit withdrawal. Specifically, East Jerusalemites will, where possible, avoid engaging with the state in sectors that explicitly legitimate the state’s claim to sovereignty. Interviewees colloquially termed these sectors “political” sectors, in reference to sectors in which the state claims a monopoly on legitimate political authority and engagement would, by extension, affirm that claim. However, interviewees distinguished “political” GSIs from “technical” ones, the latter of which are the necessary public goods, services, and institutions provided by the state for which the state holds a limited degree of legitimacy as a recognized and incumbent purveyor. Thus, East Jerusalemites will accept a limited list of state services such as trash collection or healthcare, contending that engaging with these GSIs does not explicitly affirm or advance the state’s claim to permanent sovereign authority in the territory. Instead, engagement with these “technical” GSIs only implicitly acknowledges the state’s claim to sovereignty, while providing East Jerusalemites with necessary resources. Importantly, East Jerusalemites may also seek local alternatives where available or forego engagement with Israeli state GSIs, even at personal expense. In addition to the East Jerusalem case, this theory can be generalized to all cases where the sovereignty of the state is contested by at least a subset of the population. This includes but is not limited to cases of occupation (e.g., the post-2022 Russian occupation of Eastern Ukrainian oblasts), limited statehood (e.g., the rural peripheries of Chad and Libya), failed states (e.g. Somalia, Afghanistan), weak states (e.g., Mali, Haiti), post-conflict states (e.g., Syria, Lebanon), and separatist conflicts (e.g., the PKK/Turkey civil conflict).

I find that when individuals contend that the state lacks legitimacy in a particular sector, they are less likely to engage with the state in that sector. Further, I find that perceptions of state legitimacy affect not only individuals’ personal patterns of engagement, but also their attitudes toward their peers. Using a vignette style experimentFootnote 2 which measures whether engaging with particular GSIs affect one’s assessment of the likability and respectability of potential neighbors, I find that individuals will evaluate peers more negatively should those peers engage with sectors in which the state lacks legitimacy.

This article makes four main contributions to the literatures on quotidian political participation and claim-making, civilian agency in conflict settings, state legitimacy, and Palestinian politics. First, I present a theory to explain variation in a single individuals’ claim-making behavior across sectors, which builds on the literature’s extant focus on the propensity of particular individuals to engage, the recognition of numerous claim-making repertoires, and the behavior of individuals with respect to specific sectors. Second, the Palestinian case draws attention to the ways in which the setting of conflict and territorial contestation influences individuals’ interactions with the state. Here, I make a distinction between citizen-state relations, which is the predominant framing used in the literature, and civilian-state relations, which I introduce to more aptly capture dynamics present in the East Jerusalem case and in other cases of conflict. As is often the case in contexts of conflict, occupation, and territorial contestation, the individuals living in the disputed territory may not be citizens of the state with which they engage. This could be due to a lack of conferral of citizenship status by the state, the shifting of borders, or the displacement of persons from one sovereign territory into another. A shift in framing from citizen-state relations to civilian-state relations draws attention to one of the ways that the setting of conflict alters the choices made by individuals with respect to the state. As such, a major contribution of this article is its effort to bring the literature on claim-making into conversation with the conflict literature with the aim of understanding how conflict influences claim-making dynamics.

Third, this article contributes to the literature on state legitimacy by suggesting that in addition to sub-national variation in state legitimacy (e.g., Risse and Stollenwerk Reference Risse and Stollenwerk2018), state legitimacy can vary by sector. Namely, when the state is conceived of as a conglomerate of multiple actors who interface with society at several levels (e.g., Corbridge et al. Reference Corbridge, Williams, Srivastava and Véron2005; Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018; Migdal Reference Migdal, Migdal, Kohli and Shue1994), each distinct arm of the state may hold or lack legitimacy. My findings suggest that civilians’ perceptions of state legitimacy at the sector level can lead to divergent patterns of behavior with respect to the state. Finally, the majority of political science research on Palestinian political behavior has focused on the propensity of Palestinians to engage in protest, both violently and non-violently (Gade Reference Gade2020; Pearlman Reference Pearlman2011; Zeira Reference Zeira2019). Though this research question is no doubt worthy of the caliber of academic inquiry it has thus far received, the absence of a developed literature concerning the breadth of political behaviors undertaken by Palestinians reflects the implicit biases within the discipline related to Palestinians and the Israel/Palestine conflict. Namely, focusing exclusively on Palestinian violent and non-violent protest activity paints Palestinians as primarily belligerents and revolutionaries, obscuring their role as citizens and non-citizens deserving of civil liberties, equal citizenship rights, and access to state-provided goods and services. Thus, this article contributes to the political science scholarship on Palestinian political behavior by highlighting quotidian forms of Palestinian political participation in an attempt to correct for this implicit bias.

In the following section, I provide an overview of the history of East Jerusalem’s shifting geopolitical status (1948–present) and describe the implications of historic geopolitics for Palestinian claim-making in the contemporary context. I then review the literature concerning civilian engagement with governing authorities in conflict settings, with particular attention to how the legitimacy of governing authorities alters the behavior of civilians in conflict contexts. This is followed by a presentation of the theory and associated hypotheses, as well as three GSI types and three GSI dimensions, which are used to classify GSIs as “political” or “technical.” I then use original survey data to identify variation in patterns of engagement with different state sectors. This analysis serves to identify which sectors are widely engaged with, and which sectors are less commonly engaged with. In the subsequent section, I use regression analyses to establish a relationship between perceiving engagement with a sector to legitimize the state and individuals’ behavior with respect to that sector. This is followed by evidence from a vignette-style survey experiment to show how perceptions of state legitimacy influence not only individuals’ own patterns of engagement, but also attitudes toward their peers. I conclude with a discussion of the implications for policy in East Jerusalem and beyond, as well as directions for future research.

GEOPOLITICS AND CLAIM-MAKING IN EAST JERUSALEM 1948–PRESENT

For the past 100 years, the experiences of Palestinians in Jerusalem with respect to GSI access have been inextricably tied to the geopolitical status of the city. Following the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, or Al Nakba (the catastrophe) as it is termed by Palestinians, Jerusalem was divided and East Jerusalem fell under the administrative control of the Jordanians until 1967. At the time of this division, Jordanian East Jerusalem retained only 11.5% of the entirety of the pre-1948 Jerusalem Municipal territory, while 4.5% was swallowed by the cease-fire line itself and 84% was the self-designated capital of the newly created Israeli state (PASSIA 2023). One consequence of the division of the city was the loss of all administrative institutions and apparatuses to the Israeli side, as the majority of Jerusalem’s municipal institutions—such as post offices, hospitals, municipal council buildings, and sanitation facilities, among others—were located in West Jerusalem (Schleifer Reference Schleifer1972). In effect, all that was left of the pre-war Arab municipality was several high-ranking administrators, who did their best to respond to ensuing post-war crises while displaced from their offices and stripped of the resources necessary to effectively govern (Naamneh Reference Naamneh2019). As a result, the 1948–1967 period, sometimes referred to as the Jordanian Occupation of Jerusalem, did little toward the advancement of basic social welfare goods, services, and institutions for Palestinians in East Jerusalem. Importantly, after the division of Jerusalem in 1948, Palestinians living in East Jerusalem were granted Jordanian citizenship, which did not cohere with the burgeoning collective Palestinian national consciousness (Khalidi Reference Khalidi1997; Sa’di Reference Sa’di, Ahmad H.2002). Though the majority of Palestinians living in West Jerusalem were displaced from their homes during the 1948 war/Al Nakba, those that remained were granted Israeli citizenship along with the other Palestinians who remained between the armistice “Green Line” and the Mediterranean Sea.

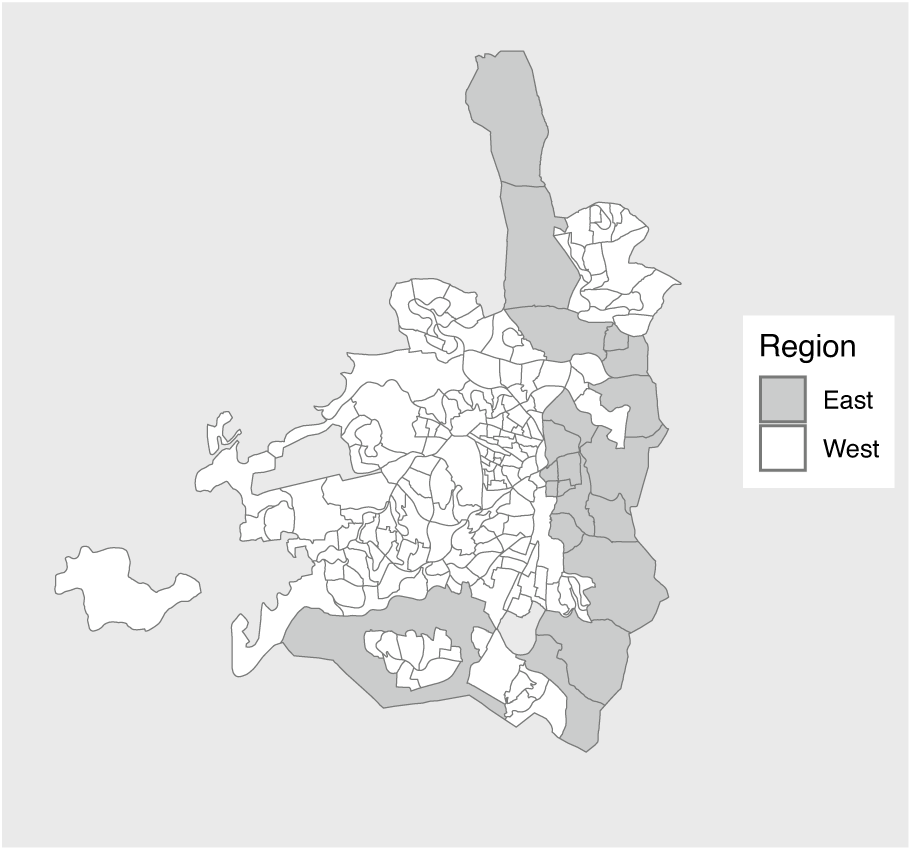

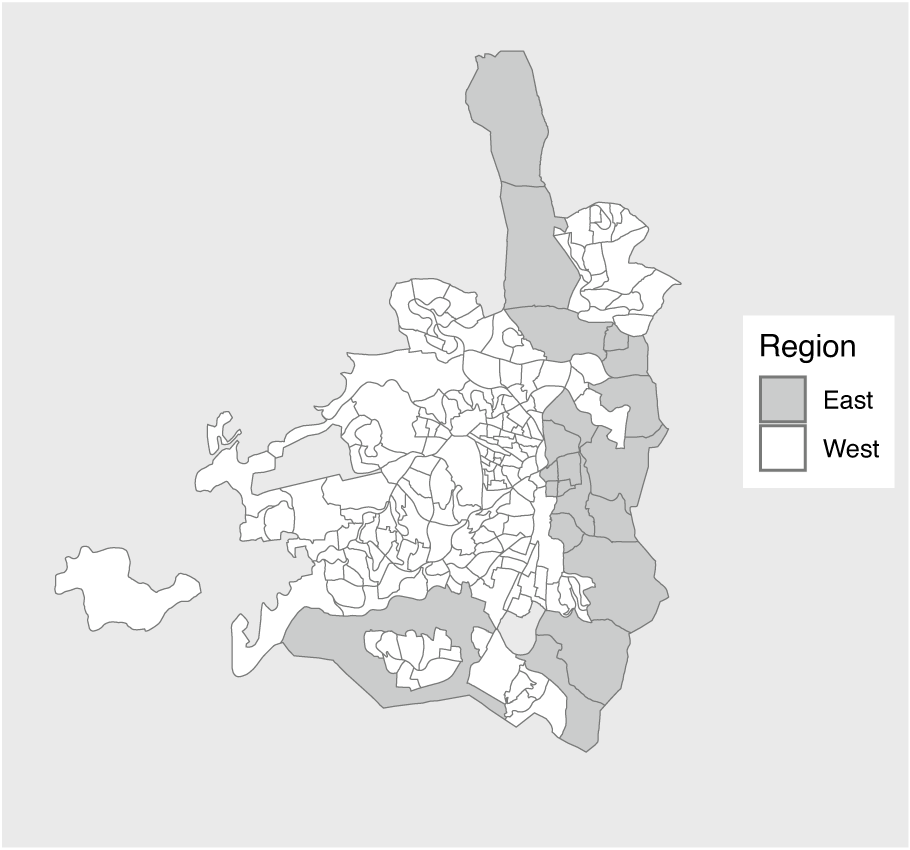

Following the Six Day War in 1967—or Al Naksa Footnote 3 as it is termed by Palestinians—in which the Jordanians were defeated, Israel extended the Jerusalem municipal boundaries to include East Jerusalem before formally annexing the area in 1980 with the passage of the Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel (State of Israel 1980). Figure 1 depicts the municipal boundaries established after Israel’s unilateral and still-contested annexation of East Jerusalem. Figure 1 also delineates between predominantly Palestinian East Jerusalem and predominantly Jewish Israeli West Jerusalem, as well as the boundaries of each neighborhood, which are also used as census district lines (i.e., statistical areas) and were most recently redrawn in 2011. The Israeli Defense Forces also conquered the West Bank, the Golan Heights, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Gaza Strip during the Six Day War/Al Naksa. At that time, the West Bank was placed under martial law and international law concerning belligerent occupation, while East Jerusalem was thereafter governed under Israeli domestic law. Importantly, international law stipulates that the jurisdictional distinction between the West Bank and East Jerusalem is void, and that Israel’s unilateral annexation of East Jerusalem does not change the status of East Jerusalem under international law, which is that of an occupied territory (Sasson et al. Reference Sasson, Klein, Maimon and Luster2012). This is significant for Palestinian East Jerusalemites as they navigate their interactions with the Israeli state, as it serves as external validation for decisions to challenge the Israeli state’s legitimacy through the selective use and non-use of state-provided goods and services.

Figure 1. Map of East and West Jerusalem (1967–Present)

The events of 1967 were a significant turning point in establishing the contemporary terrain of claim-making for Palestinian East Jerusalemites. Most consequentially, at the time of annexation Palestinian East Jerusalemites were granted permanent resident status, but not full and equal citizenship in the State of Israel (Halabi Reference Halabi1997). What began as an administrative question regarding the legality of imposing citizenship on an occupied population has since transformed into one of the most significant existential threats to Palestinian livelihood and well-being in East Jerusalem. While Palestinian East Jerusalemites may now apply for Israeli citizenship, the state has not unilaterally extended citizenship rights to the whole population. As a result, East Jerusalemites are barred from significant decision-making roles in city politics and the maintenance of a Jewish majority in the city is ensured, both of which serve the long term interests of the Israeli state with respect to the city albeit to the detriment of Palestinian East Jerusalemites (Sasson et al. Reference Sasson, Klein, Maimon and Luster2012). As non-citizen permanent residents and holders of Jerusalem “blue IDs,” East Jerusalemites must continually prove to the Ministry of the Interior that their “center of life” remains in Jerusalem in order to avoid deportation and/or residency status revocation.Footnote 4 Coupled with a housing crisis, the threat of home demolitions, and the extreme difficulty of obtaining building permits to expand existing homes, Palestinians in East Jerusalem face difficulties finding affordable and legal options to remain in the city once they marry, leave home, or outgrow their current dwellings. Further, permanent residents have only limited voting rights in Israeli elections; Palestinian East Jerusalemites are eligible to vote in municipal elections, but not national elections. Importantly, the most significant decisions concerning the status of Jerusalem are administered at the national level under the Ministerial Committee on Jerusalem Affairs, rather than by the Jerusalem Municipality (Sasson et al. Reference Sasson, Klein, Maimon and Luster2012).

In addition to concerns over the futility of voting, the vast majority of Palestinians abstain from voting in municipal elections because voting is thought to legitimate Israel’s claim to sovereignty over the city (Blake et al. Reference Blake, Bartels, Efron and Reiter2018; Prince-Gibson Reference Prince-Gibson2018). Further, only citizens of Israel are permitted to hold municipal office and thus the vast majority of East Jerusalemite would-be voters could not run in municipal elections even if they desired to. Based on Israel Central Bureau of Statistics Census data, the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research reports that there were 375,600 Palestinians living in Jerusalem in 2021, which amounts to 38.9% of the total population of the city and thus a significant block of non-voting eligible voters (Assaf-Shapira et al. Reference Assaf-Shapira, Haddad, Gefen and Yaniv2023).

Beyond rights to limited formal political participation, Palestinian East Jerusalemites with permanent resident status are eligible to access municipal and national state-provided public goods and social services. This includes goods and services such as membership in the state health insurance schema, social security and social welfare benefits, and the array of municipally funded services such as education, infrastructure maintenance, trash collection, and access to public parks, playgrounds, and municipal-run community centers. Indeed, the Israeli state has at different points in its history pursued explicitly integrationist policies with respect to the broader Palestinian Arab minority in Israel, notwithstanding the fact that such policies have not resulted in substantive equality between Arab and Jewish Israelis but instead what recent scholarship has deemed “subordinate integration” of Palestinians into Israeli society as its lowest ranking members (Degani Reference Degani2018; Reference Degani2020). These state efforts have been motivated in large part by concerns over security and separatism, aiming to provide sufficient services and incentives to the Arab minority to stave off anti-state protest and identification with Palestinians in the Occupied Territories on nationalist grounds (Lavie Reference Lavie2018). As such, when Palestinians in East Jerusalem and Israel withhold their claims-making and seek in-group alternatives, they are, in doing so, resisting state-led efforts toward a “subordinate integration” (Degani Reference Degani2018; Reference Degani2020).

Further, anyone who has visited both East and West Jerusalem will report the stark disparity between the level of development and public infrastructure in East Jerusalem as compared to most neighborhoods of West Jerusalem. The full extent of disparities in service provision between East and West Jerusalem are well documented, but are beyond the scope of this article. However, what is important to note is the twin problems of (a) inadequate municipal funding allocated for development in East Jerusalem and (b) the political sensitivity of municipal interventions in East Jerusalem. In 2018, the Jerusalem Municipality launched a half-billion dollar plan to invest in East Jerusalem’s schools and public infrastructure. However, the plan was controversial among both Palestinians and far-right ultra-nationalist Israeli lawmakers. Plans for its renewal and expansion were halted in 2023 (Hasson and Friedson Reference Hasson and Friedson2023).

Longtime Jerusalem city councilperson Meir Margalit describes the conundrum of development in the context of occupation,

The inauguration of a new municipal school is a positive event, but taking a broader view, we understand that it implies the insertion of hundreds of students into the Israeli school system, whose personal and family data will be catalogued, coded, and computed to become part of an Israeli control device…to a certain extent, the trap of Occupation lies in the fact that any service provided by the state for the benefit of the population becomes another pillar of the oppressive system. (Margalit Reference Margalit2020, 21–2)

Thus, it is in the context of scarcity, discrimination, and suspicion that Palestinians must make choices regarding which services they are willing to accept from the Israeli state. In the following section, I review the literature concerning civilian-state relations in contexts of conflict before presenting a theory to explain patterns of claim-making in conflicted and contested territories like East Jerusalem.

CIVILIAN-STATE RELATIONS IN CONFLICT SETTINGS

Absent conflict, individuals’ participation in politics and relations with the state can vary greatly in degree of formality and scope, ranging from formal political participation through activities like voting and lobbying, to quotidian forms of participation whereby individuals make claims on the state in pursuit of rights or resources (Auerbach Reference Auerbach2019; Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018). In contexts of conflict, individuals must continue to navigate their relations with governing authorities in order to meet their daily needs, and may even continue engaging in formal means of political participation. However, navigating one’s relationship with the state in contexts of conflict introduces added levels of complexity. For one, the fragmentation of territory and political authority can lead to the emergence of multiple local political or social “orders” such that civilians must interface with both state and non-state actors attempting to govern (Arjona Reference Arjona2014; Reference Arjona2016; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006; Scott Reference Scott2009; Staniland Reference Staniland2012; Wood Reference Wood2008). The now well-established rebel governance literature identifies the various choices civilians make when faced with rebel incursion and the transference of power to rebels or other non-state armed groups. Here scholars have distinguished between civilian collaboration and defection (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006), flight, support, and voice (Barter Reference Barter2014), cooperation, non-cooperation, and migration (Arjona Reference Arjona2017), civilian maintenance of autonomy from armed groups (Kaplan Reference Kaplan2017), and degrees of support (Wood Reference Wood2008) for non-state armed groups. This conceptual mapping of the choices of civilians in response to rebel rule represents a significant contribution of the rebel governance literature to the study of civilian political behavior in conflict.

In many intra-state conflicts, the state retains governing authority in some portion of the territory, even if fragmented, and thus it is also important to understand civilian political behavior with respect to the state and the dynamics of the civilian-state relationship in conflict. To this end, several studies identify determinants of civilian-state collaboration in conflict settings. One subset of this literature considers the impact of government repression and the use of force on civilian willingness to collaborate with government entities. Using the case of the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan (2013–2015), Condra and Wright (Reference Condra and Wright2019) find that civilians are less willing to collaborate with the state if they perceive the state to be carelessly wielding force, but more willing to collaborate with the state if they perceive insurgents to be doing so. Bateson (Reference Bateson2017) finds that the military’s use of repression, fear, and force in the Guatemalan civil war effectively socialized civilians into postures of pro-government support that persisted even after the conclusion of the conflict. Others question whether a “hearts and minds” approach, principally marked by the increase in clientelistic handouts to civilians by the government, increases cooperation between governments and civilians in conflict (Aldama Reference Aldama2022; Berman, Shapiro, and Felter Reference Berman, Shapiro and Felter2011). While Berman, Shapiro, and Felter (Reference Berman, Shapiro and Felter2011) find that increases in the provision of state services leads to a decrease in civilian support for insurgents, Aldama (Reference Aldama2022) argues that other factors, such as whether the state increases its use of hard power against civilians concurrent with the provision of aid, influence whether aid effectively increases civilian collaboration with the government in the face of insurgency. In addition to studies of cooperation between states, civilians, and rebels in conflict, studies of state legitimacy in conflict help to situate the theory presented here. This is the focus of the subsequent section.

State Legitimacy in Conflict Settings

In addition to questions of civilian-state cooperation and non-cooperation, whether the state possesses or lacks popular legitimacy is a significant dimension of civilian-state relations in conflict settings. State legitimacy can be defined as societies’ acceptance of the state’s right to rule (Gilley Reference Gilley2009; Risse and Stollenwerk Reference Risse and Stollenwerk2018). This and similar definitions are drawn from foundational works of classical legitimacy theory, which describe the relationship between citizens and the nation-states who govern them (Weber Reference Weber, Guenther, Claus and Ephraim1978; Zelditch Reference Morris, Jost and Major2001). Since the penning of these foundational works, state legitimacy has been studied as “a condition, a cause, and an outcome” across social science disciplines (Schoon Reference Schoon2022, 478). Several scholars have noted the difficulties in applying classical legitimacy theory to conflict settings, because common conditions of conflict—such as the fragmentation of political authority and territory, the weakness or failure of the state, and frequent changes in the actors and audiences that confer legitimacy—are incongruent with the conditions assumed of the modern nation-state from which theories of legitimacy were derived (Risse and Stollenwerk Reference Risse and Stollenwerk2018; Von Billerbeck and Gippert Reference Billerbeck, Sarah and Gippert2017). Despite these concerns, scholars continue to use the concept as both a cause and an outcome in studies of conflict, as evidenced by growing interest in at least two related research agendas; one that identifies factors that increase (or decrease) state legitimacy in conflict and post-conflict contexts (e.g., Mcloughlin Reference Mcloughlin2015; Sexton and Zürcher Reference Sexton and Zürcher2024), and another that uses legitimacy as an explanatory variable for outcomes of interest like the success of peacebuilding operations and post-conflict statebuilding efforts (e.g., Dagher Reference Dagher2018; Gippert Reference Gippert2016). This article contributes to the second stream of scholarship by asking how civilians’ conferral of legitimacy upon the state influences civilian-state engagement patterns in contexts of contested sovereignty. Importantly, this article empirically demonstrates that state legitimacy can vary by state sector; civilians may confer legitimacy upon the state in select sectors while contesting the state’s legitimacy in other sectors, and this affects patterns of civilian engagement at the sector level. This finding is a key contribution of the article to studies of state legitimacy in conflict.

State Legitimacy Discourses in East Jerusalem

Within the East Jerusalem context, Palestinians have adopted the “anti-normalization” discourses of the broader Palestinian National Movement to describe their opposition to the Israeli state’s claim to sovereignty and right to rule in East Jerusalem. Normalization and anti-normalization discourses emerged in the wake of the 1993 Oslo Accords to describe the new terms of relations set between the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Israeli state (Shlaim Reference Shlaim1994). The most significant feature of the shift in the post-Oslo status quo for the emerging normalization discourse was the PLO’s newfound recognition of the Israeli state, and the Israeli state’s reciprocal recognition of the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people (Albzour et al. Reference Albzour, Penic, Nasser and Green2019). Thus, the act of mutual political recognition was the first act of “normalization” whereby both parties consented to a nascent, limited, and oft-criticized as asymmetrical, form of political reciprocity for the first time in their histories.

The term “normalization,” or tatbi‘a in Arabic, has since been defined as “the process of building open and reciprocal relations with Israel in all fields, including the political, economic, social, cultural, educational, legal, and security fields” (Salem Reference Salem2005). Anti-normalization contingents, such as the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanction Movement (BDS), have instead focused on the negative valence of the term, and have defined normalization as a rejection of the premise that the Israeli state can be treated as a “normal” state so long as it engages in the oppression of Palestinians through occupation (+972 Magazine 2011). Though the term emerged in a particular context to describe the legitimization of the State of Israel at the highest political levels, as the definitions above suggest, it has since been adopted by Palestinians and others at all levels and of all political persuasions to describe many possible forms of relations with the Israeli state and with Israeli citizens (Albzour et al. Reference Albzour, Penic, Nasser and Green2019; El Kurd Reference El Kurd2022; Reference El Kurd2023; Rauch Reference Rauch2011; Scham and Lucas Reference Scham and Lucas2003). Importantly, in each distinct location of historic Palestine (East Jerusalem, Gaza, the West Bank, and Israel), within the Palestinian diaspora, and in the Arab world, normalization has taken on different meanings with different implications for those seeking to avoid it or engage in it (Albzour et al. Reference Albzour, Penic, Nasser and Green2019; El Kurd Reference El Kurd2022; Scham and Lucas Reference Scham and Lucas2003).

In East Jerusalem, “normalization” has come to refer to actions that legitimate the Israeli state’s claim to sovereignty over East Jerusalem, which is contested by the vast majority of Palestinian East Jerusalemites. In principle, all governance activities undertaken by the Israeli state in East Jerusalem legitimate the state’s claim to sovereignty, but in practice East Jerusalemites classify a more circumscribed set of state activities as normalizing ones. Though ultimately definitions of normalization are highly personal and specific to each individual, consensus has developed within the broader East Jerusalemite community concerning which state activities are considered normalizing ones and thus are most likely to be avoided, and which are instead widely engaged with. In the following section, I present a theory to explain the engagement choices of Palestinians in the context of contested East Jerusalem, which can also be generalized to other cases of contested sovereignty.

A THEORY OF CIVILIAN CLAIM-MAKING IN CONTEXTS OF CONTESTED SOVEREIGNTY

Here, I develop a theory concerning how civilians in contested and conflict-affected territories make everyday choices regarding their engagement with the state. Variation can be expected in civilians’ patterns of engagement with each discrete arm of the state. But what explains this variation? Why are civilians in contexts of contested sovereignty more likely to engage with select arms of the state as compared to others? These are the principal questions addressed in the article.

To date, much of the extant scholarship on claim-making has focused either on the citizens’ relations with the state in peacetime (e.g., Auerbach Reference Auerbach2019; Brass Reference Brass2017; Chazan Reference Chazan, Migdal, Kohli and Shue1994; Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018; Migdal Reference Migdal, Migdal, Kohli and Shue1994), or on other dyadic relationships in conflict settings, such as the rebel-civilian dyad, or the rebel-state dyad (Arjona Reference Arjona2017; Barter Reference Barter2014; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006; Kaplan Reference Kaplan2017; Staniland Reference Staniland2021; Wood Reference Wood2008). The focus of this article is instead on civilian-state relations in contexts of conflict where the sovereignty of the state is contested, and specifically on quotidian relations such as claim-making. In conflicts where the sovereign authority of the state is called into question, eroded in whole or in part, and/or fractured and ultimately shared with other actors, these situations can broadly be termed contexts of contested sovereignty. In all cases, a defining feature of contexts where state sovereignty is contested is that a significant contingent of the population, whether armed or civilian, perceives the state to be governing illegitimately.Footnote 5 In many cases, alternative governing authorities may compete with the state for legitimacy, as in the case of Hezbollah in Lebanon, and thus the state’s lack of legitimacy is a function of legitimacy being conferred on another actor. Additionally, the contingent contesting the state’s claim to sovereignty may be affiliated with an armed faction, or may instead be comprised of civilians committed to nonviolence. Cases of occupation are a subset of instances of contested sovereignty, whereby the occupied population may choose to contest the authority of the occupying power to govern within the occupied territory.Footnote 6 Beyond occupation, cases of limited statehood (e.g., Chad, Libya), failed states (e.g., Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo), weak states (e.g., Haiti), post-conflict states where active contestation over territory persists (e.g., Syria, Lebanon), and separatist conflicts (e.g., the PKK/Turkey civil conflict, the Hong Kong/China conflict) are cases of contested sovereignty to which the theory would readily apply.

I argue that in contexts of contested sovereignty, the degree to which civilians engage with the state is colored by civilians’ perceptions of the state’s legitimacy, or right to rule, in the disputed territory. If the state is assumed to be a conglomerate of agencies, actors, and institutions operating, as Migdal (Reference Migdal, Migdal, Kohli and Shue1994, 16) describes, from “the trenches” of daily bureaucracy to the “commanding heights,” then each disaggregated level of the state is an arena in which the sovereignty and legitimacy of the state can be contested by civilians. Thus, civilians’ choices regarding engagement with each discrete arm, actor, and institution of the state are a function of their appraisals of the state’s right to rule in that sector. Civilians will avoid engagement if at all possible in state sectors that are perceived to explicitly affirm the state’s claim to sovereignty in the disputed territory. Most importantly, civilians will avoid engagement with state goods, services, and institutions that reinforce the state’s claim to monopoly, in particular the state’s claim to monopoly on the means of coercion. As a result, civilians will avoid engagement with force-monopolizing institutions, such as the police and the judiciary. Large numbers will also avoid engagement with narrative-monopolizing institutions, such as state primary and secondary schools which teach state curricula. However, civilians will accept necessary public goods and services such as water, sanitation, and healthcare, having granted the state a limited degree of legitimacy to provide basic, though non-coercive, goods and services. Where possible, civilians in contexts of contested sovereignty will seek out non-state alternatives or may even forego engagement at personal cost if the good, service, or institution affirms the state’s claim to exclusive and permanent sovereign rule.

Having adopted and contextually appropriated the anti-normalization discourse of the Palestinian national movement, East Jerusalemites distinguish between GSIs that “normalize” or legitimate the Israeli state’s claim to permanent monopoly and sovereignty over East Jerusalem, and GSIs that are instead acceptable to engage with by virtue of having conferred upon the Israeli state a limited degree of legitimacy to provide for basic needs. As one interviewee succinctly stated, “things that are considered to be secondary are considered normalization…but demanding basic rights is outside of normalization.”Footnote 7 During interviews, Palestinian East Jerusalemites also used the terms “political” and “technical” to distinguish between activities that explicitly affirm the Israeli state’s claim to monopoly and sovereignty, and those that instead only implicitly affirm this claim. In describing GSIs such as infrastructure, sanitation, sewage, and electricity, one interviewee noted that,

There is a high level of willingness to work with these entities. They are not seen as political, but moreso as technical entities…these services don’t hold nearly as much of an emotional, ideological, or political weight. People feel like if they can do something to make a difference now, they will do it. (Interviewee 19. 2022. Israeli Human Rights Organization Employee. Interviewed by Author, East Jerusalem.)

The distinction being made between political and technical GSIs coheres with the generalizable theory presented here, which is that civilians in contexts of contested sovereignty are less likely to engage with state GSIs that are associated with the state’s claim to monopolized sovereign rule. East Jerusalemites colloquially term these GSIs “political,” in reference to the explicit manner in which engagement with these GSIs supports the Israeli state’s claim to sovereign political authority over East Jerusalem. By abstaining from engagement with “political” GSIs, East Jerusalemites openly reject this claim to sovereign political authority, and assert that the state lacks legitimacy conferred by the civilian population. However, East Jerusalemites are willing to accept “technical” GSIs, such as healthcare, infrastructure, water, and other basic public goods and services, based upon the dual contentions that (a) the Israeli state has a limited degree of performance legitimacyFootnote 8 as a belligerent occupying power under the Geneva Conventions to provide basic goods and services to peoples within the occupied territories and (b) engagement with these GSIs only implicitly affirms the state’s right to rule, but does not explicitly affirm the state’s claims to permanent, monopolized coercion.

Further, because the choices individuals make with respect to the state can be need-driven and complex, these choices are likely to be influenced by several factors at once, such as ease of access, affordability, and the presence or absence of alternative options. I do not rule out the likelihood that engagement with select technical services is especially high due to the high cost of alternatives (e.g., healthcare) or lack of alternatives altogether (e.g., infrastructure). However, interview data suggest that even amidst constraints of cost and availability, Palestinians still assign designations of political and technical to different service sectors and make choices with these distinctions in mind. As such, I acknowledge the possibility of equifinality, and that these factors could also be relevant for decision-making alongside perceptions of state legitimacy at the sector level.

Finally, it is important to note that this theory was developed both deductively and inductively. Recent work on iterative theory development recognizes the crucial role that fieldwork can play in helping to develop and refine theories before testing them using other qualitative or quantitative means (Kapiszewski, MacLean, and Read Reference Kapiszewski, MacLean and Read2022; Pérez Bentancur and Tiscornia Reference Bentancur, Verónica and Tiscornia2022). Having spent 14 total months in the field (three months “soaking and poking” in 2019 and 11 months in 2022), the theory was first derived deductively before arriving in the field and then iteratively refined inductively while in the field using interview evidence. By the end of the 11 months in the field in 2022, I was confident to have reached the point of “saturation.” Importantly, the theory presented in this article aims to explain variation in choices individuals make between different types of GSIs, but does not answer the question of what factors or characteristics make an individual more likely to engage with the state as compared to their peers. While this question is outside of the scope of this article, it is the topic of a larger ongoing project.

GSI Types and Dimensions

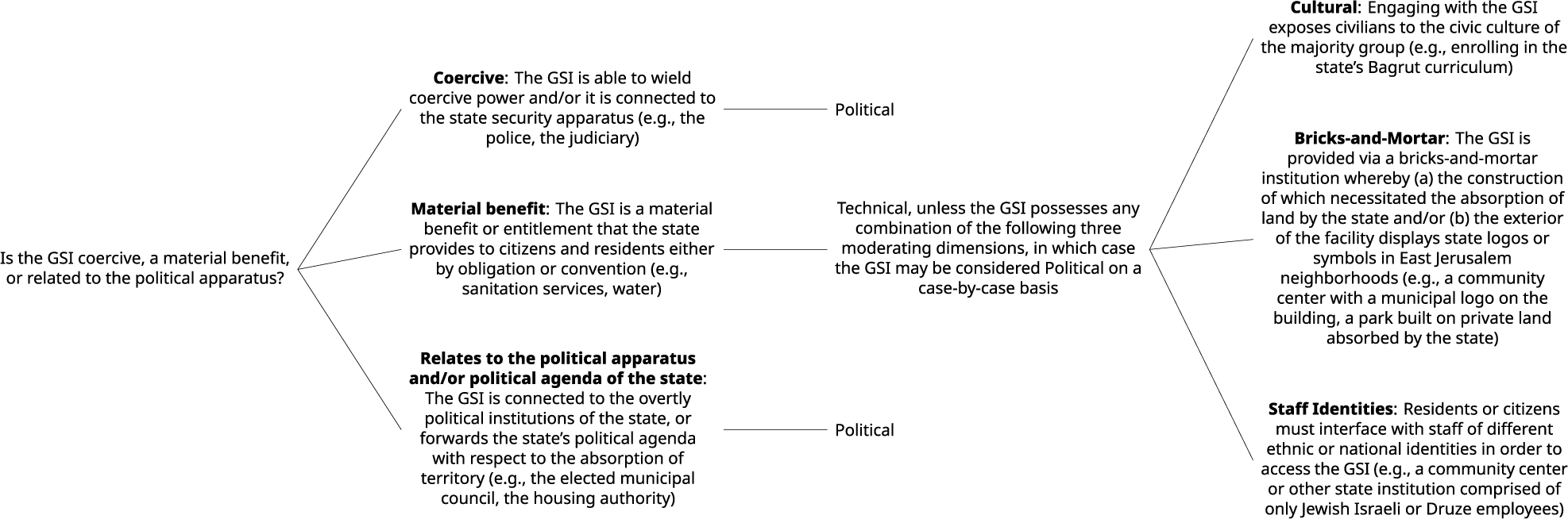

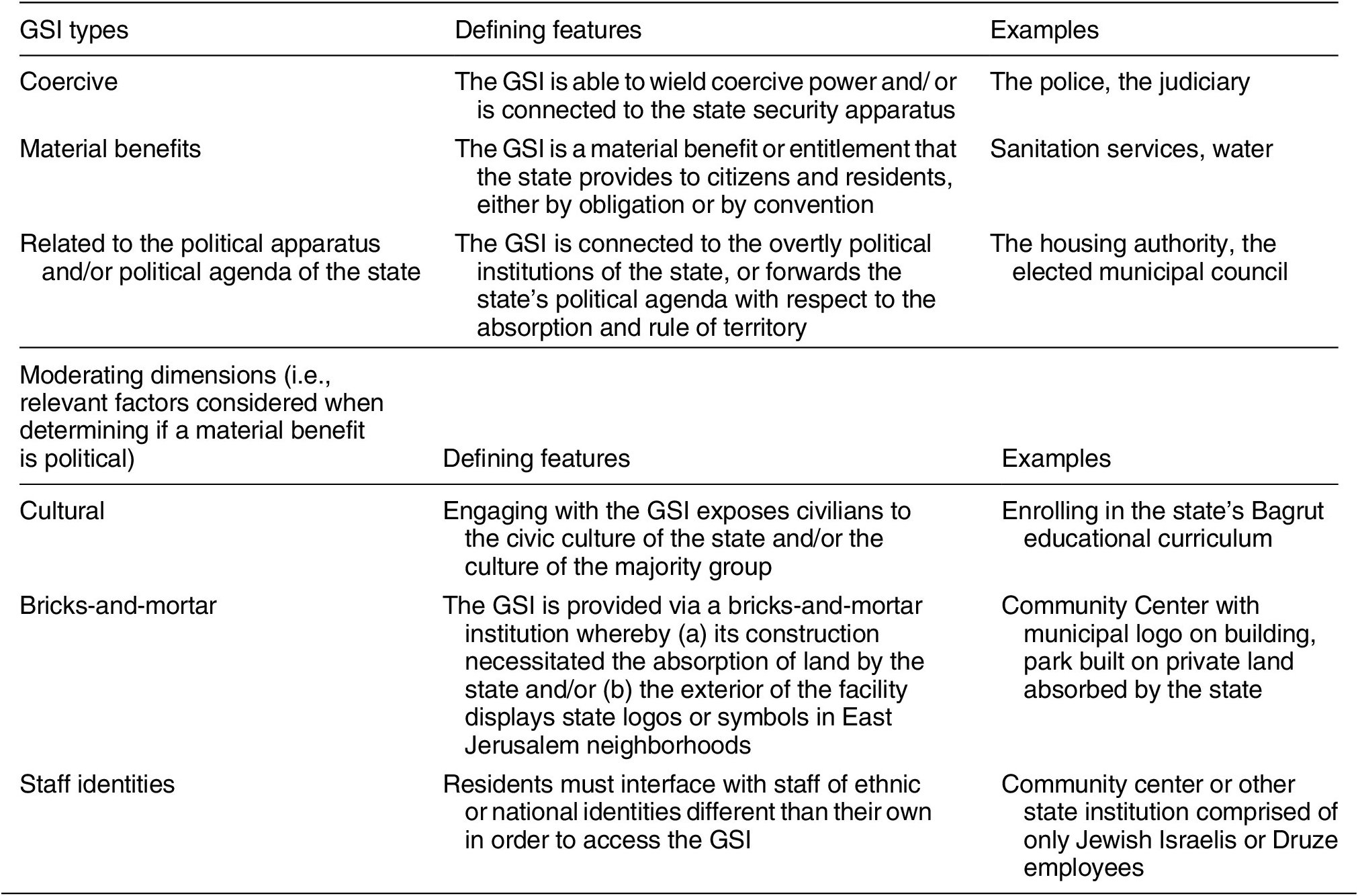

If the political/technical distinction is the relevant boundary line between GSIs that individuals engage with or abstain from due to perceptions of the state’s legitimacy, it is important to understand what features are associated with political GSIs and what features are associated with technical ones. Here, I identify three GSI Types and three Moderating Dimensions, outlined in Table 1 and Figure 2. In keeping with criteria often cited to evaluate typologies, the three GSI Types listed in Table 1 are meant to be “exhaustive”Footnote 9 and therefore all GSIs across cases should be able to be classified as one of the three types (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005, 238). Types are kept to a minimum for the sake of parsimony (Gerring Reference Gerring1999), but it should be noted that in Islamist regimes or other regimes with state religious institutions, “religious institutions” could be a fourth relevant GSI type in addition to the three types conceptualized here. The three Moderating Dimensions, also listed in Table 1, are features of select Material Benefits (GSI type 2) that, if present, suggest that a GSI should be considered a political GSI. In the absence of any or all Moderating Dimensions, a Material Benefit will be considered technical. Importantly, these types and dimensions are generated from interview data, and are the factors repeatedly mentioned when interviewees discussed how individuals navigate state engagement in light of anti-normalization considerations.Footnote 10 Table 1 provides an introductory description of each type and dimension and an extended discussion of each with citations of interview evidence is included in the Supplementary Materials Section C: Additional GSI Type and Dimension Explanations.

Table 1. GSI Types and Moderating Dimensions

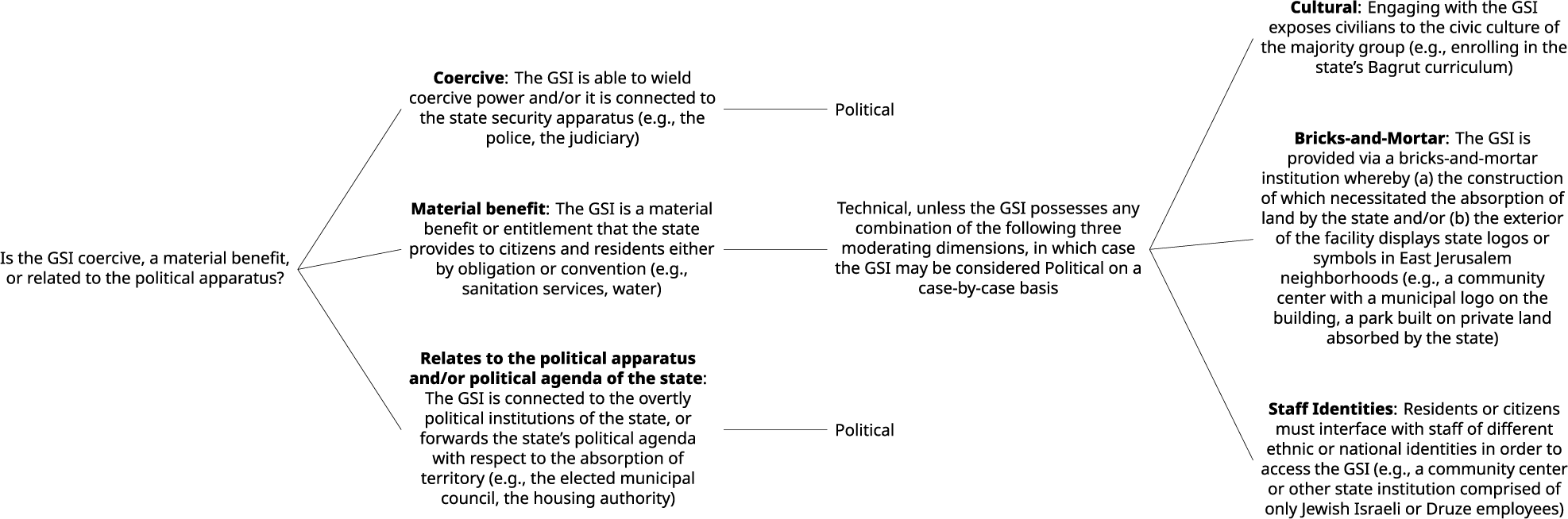

Figure 2. GSI Type and Dimension Decision Tree

As Table 1 outlines, GSIs are first sorted into three categories or types: coercive, related to the political apparatus or political agenda of the state, and material benefits. Two of the GSI types—Coercive and Related to the Political Apparatus—are sufficient conditions for a GSI to be considered “political,” such that all GSIs in these two categories are deemed political. However, they are not necessary conditions; GSIs that are not overtly coercive or connected to the political apparatus (i.e., Material Benefits) may still be considered political.

Figure 2 helps to clarify the distinctions and the relationships between GSI types and dimensions. Specifically, the decision tree reflects that if a GSI is not coercive or related to the political apparatus, it is considered a “material benefit.” Some material benefits are considered political if case-specific manifestations of the three moderating dimensions are invoked (staff-identities, cultural, bricks-and-mortar). If none of these three dimensions are relevant to the GSI, then the material benefit is considered a technical GSI. For example, while public parks and playgrounds are material benefits that are at base considered technical, if a new playground is slated to be built in East Jerusalem and its construction would necessitate the absorption of private land as state property, the “bricks-and-mortar” dimension would help East Jerusalemites to identify the newly constructed playground as a political GSI. Alternatively, if a dilapidated playground is renovated in an East Jerusalem neighborhood, the playground would likely be considered a material benefit lacking complications related to the three moderating dimensions and thus be designated as a technical GSI. This example reflects how the same GSI, a playground, can be considered political or technical based upon whether the moderating GSIs are invoked in its construction. In a similar way, select GSIs—such as community centers and the housing authority—are considered both political and technical, depending on the individual’s reason for usage.Footnote 11 Importantly, the logic of the decision tree and the terminal node designations of “political” and “technical” were inductively derived by the author as a summation of the logics elucidated by interviewees.

The identification of GSI types and dimensions is a key conceptual contribution of the article that can be used to help classify GSIs in contexts of contested sovereignty beyond East Jerusalem. While GSIs beyond East Jerusalem should all be able to be sorted into one of the three GSI types (or four if state religious institutions are present), in other contexts there may be additional moderating dimensions that are relevant. With these types and dimensions in mind, in the subsequent section I outline several hypotheses.

Hypotheses

Here, I outline my theoretical expectations for how perceptions of state legitimacy influence civilian claim-making in East Jerusalem. First, I expect variation in engagement with each discrete GSI, and that this variation is driven by civilians’ perceptions of whether the state holds the right to rule in that sector.

H1: If an individual perceives a GSI to legitimate or “normalize” the sovereign authority of the Israeli state, they are less likely to engage with the state concerning that GSI.

H1a: East Jerusalemites are less likely to engage with GSIs deemed “political,” such as policing, justice and dispute resolution, primary and secondary Municipal education and education using the Israeli Bagrut curriculum, higher education, voting, community centers, and housing.

H1b: East Jerusalemites are more likely to engage with GSIs deemed “technical,” such as healthcare, parks (parks, playgrounds, community gardens, soccer fields), sanitation services, transportation, and public infrastructure.

H1a and H1b outline my theoretical expectations concerning which specific GSIs are most likely to be engaged with and which are most likely to be avoided. Together, Hypotheses 1, 1a, and 1b reflect the expectation that perceptions of state legitimacy affect the behavior of East Jerusalemites with respect to each discrete GSI provided by the Israeli state. This leads to Hypothesis 2.

H2: East Jerusalemites will evaluate peers who engage in “political” GSIs more negatively than those who engage in “technical” GSIs.

Hypothesis 2 reflects the expectation that, in addition to behavior, perceptions of state (il-)legitimacy influence East Jerusalemites’ attitudes toward their peers. As such, Hypotheses 1 (1a, 1b) and 2 together test for the affect of individuals’ perceptions of the legitimacy of the state’s right to rule in each discrete sector on both their behavior with respect to the state and their attitudes toward fellow East Jerusalemites as a result of their engagement decisions.

DATA

To evaluate the influence of perceptions of state legitimacy on engagement with GSIs, I use both qualitative and quantitative data sources collected between January 2022 and August 2023 in East Jerusalem. The qualitative interview data were collected first and used to inform the creation of the survey instrument and the development of the theory. Specifically, I conducted 55 semi-structured in-depth interviews between February 2022 and November 2022 with Palestinian civilian society organization employees, academics, journalists, activists, Israeli human rights organization employees, current and former Jerusalem municipality employees, Mukhtars,Footnote 12 and other relevant community leaders. Interviews were conducted at the mid/expert level with societal leaders and public officials for the purposes of theory building, with the expectation that experts could identify and summarize society-wide trends and that hypotheses generated based on expert opinions would then be tested in the general population with the subsequent enumeration of the survey. Informed consent information was presented to all interviewees and interviewees were not paid. The interviews were conducted in English (31), Palestinian colloquial Arabic (21), and Hebrew (3), as chosen by the interviewee. Only the general category of organization or professional affiliation was recorded (e.g., Palestinian civil society organization employee, Israeli human rights organization employee) to protect interviewee privacy in a highly politically sensitive environment. Given that the experiences and decisions in question are those of Palestinian East Jerusalemites, I interviewed fewer Jewish Israelis (10) and foreign nationals (5) than Palestinians (40). Due to the sensitivity of the political environment and of the research question itself, additional information regarding research ethics, author positionality, and interview sampling procedures is available in the Supplementary Materials Section D: Additional Methods and Research Ethics Information.

The quantitative evidence relies upon original survey data from a randomly selected representative sample of 1,255 Palestinian East Jerusalemites conducted between June 2023 and August 2023 (Bagdanov Reference Hannah E2025). The survey was implemented by the Palestinian Center for Public Opinion (PCPO), a survey firm with its headquarters in the West Bank. I fielded a pilot survey (n = 50) in early June 2023 prior to the implementation of the survey (n = 1,255). The survey was administered using tablets and was conducted in-person in Palestinian Colloquial Arabic by Palestinian enumerators (Gengler, Le, and Wittrock Reference Gengler, Le and Wittrock2021), who drew a randomly generated representative sample from each of East Jerusalem’s 19 neighborhoods. Jewish Israelis living in these neighborhoods were excluded from the sample. The response rate for the survey was 77%. Informed consent was collected from all respondents prior to the start of the survey, and respondents were not paid for their participation. As will be detailed below, the survey included both experimental and observational components. To capture patterns of engagement with different service sectors, a large portion of the original survey was dedicated to what is referred to in the survey as a “Services Census.”Footnote 13 The Services Census captures whether individuals use, or would considering using, state GSIs across 21 different service sectors when in need of help in that area. Two example questions from the services census are listed in the Supplementary Materials Section A: Survey Question Examples, each representing one of the two main question types included in the services census.

RESEARCH DESIGN

I analyze the survey data in three ways. First, I use descriptive statistics to show basic patterns of engagement and abstention from a list of 21 distinct municipal and national GSIs. I then use logistic regression analyses to measure whether perceiving engagement with a particular GSI to be an act of normalization makes individuals more or less likely to engage with that GSI. The principal independent variable in these regressions is a binary “yes/no” answer to the question of whether engaging with a particular GSI should be considered normalization. This question wording was chosen because I was confident that all East Jerusalemites surveyed would be familiar with the concept and connotations of the term normalization or tatbi‘a. However, if the survey was replicated in another context, a direct question concerning state legitimacy would be more appropriate. The primary dependent variable used in the logit regressions is a composite binary “1/0” record of whether an individual has reported using or seeking help from the Israeli authorities concerning a given GSI.Footnote 14 It should be noted that questions concerning usage were asked before questions concerning normalization perception, so as not to introduce an anti-use prime before collecting usage information.

In addition to the binary explanatory variables which record whether the individual considers engaging with a particular GSI to be an act of normalization, the models also include control variables for respondent sex, age, neighborhood, education level, political apathy score, marital status, income, refugee status, political party affiliation, frequency of religious service attendance, and having spent time in an Israeli jail or prison. The variable for time spent in an Israeli jail or prison is included to account for spillover effects between the carceral face of the state and different forms of GSI engagement. As Zeira (Reference Zeira2019) illustrates, those whose friends or family have spent time in the disciplinary institutions of the Israeli state are more likely to engage in non-violent protest activity. Engagement spillover effects have been demonstrated in other contexts, such as increased demands for citizenship rights following the claiming of housing rights among citizens in Brazil (e.g., Holston Reference Holston2008), or a decreased willingness to engage with state social welfare apparatuses following contact with American law enforcement and carceral institutions (e.g., Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014; Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017). The variable for perceived State Responsiveness is included to test an alternative explanation, which is that individuals who perceive the state to be responsive are more likely to engage with the state. Example survey questions are included in the Supplementary Materials section A: Survey Question Examples as well as a description of all variables in Supplementary Materials Section E: Variable Descriptions.

Logistic regression models were chosen due to the binary structure of the dependent variable. Further, it is possible to compute predicted probabilities on a 0–1 scale using logistic regression models (as opposed to Ordinary Least Squares models), and predicted probabilities are among the most easily interpretable formulations of regression results, particularly given that the research question pertains to the likelihood that individuals would use discrete GSIs. Running ten models, each pertaining to a discrete sector, allows for the comparison of coefficients between sectors, which is a primary contribution of the article and a test of Hypotheses 1a and 1b.

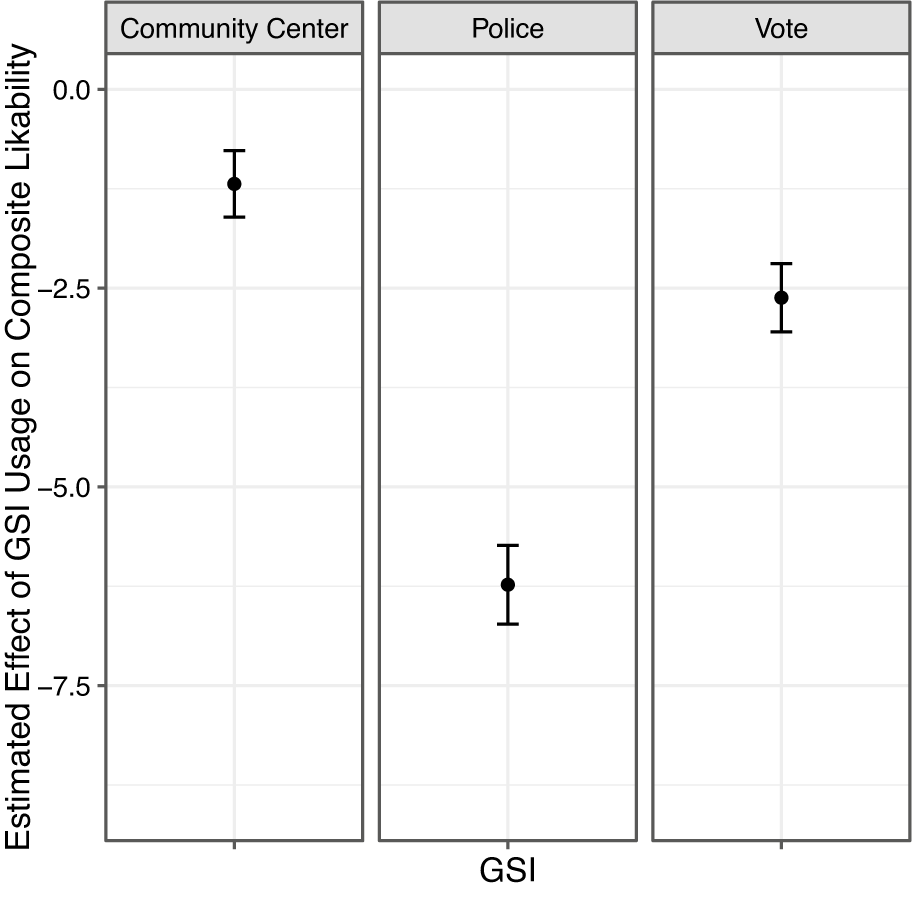

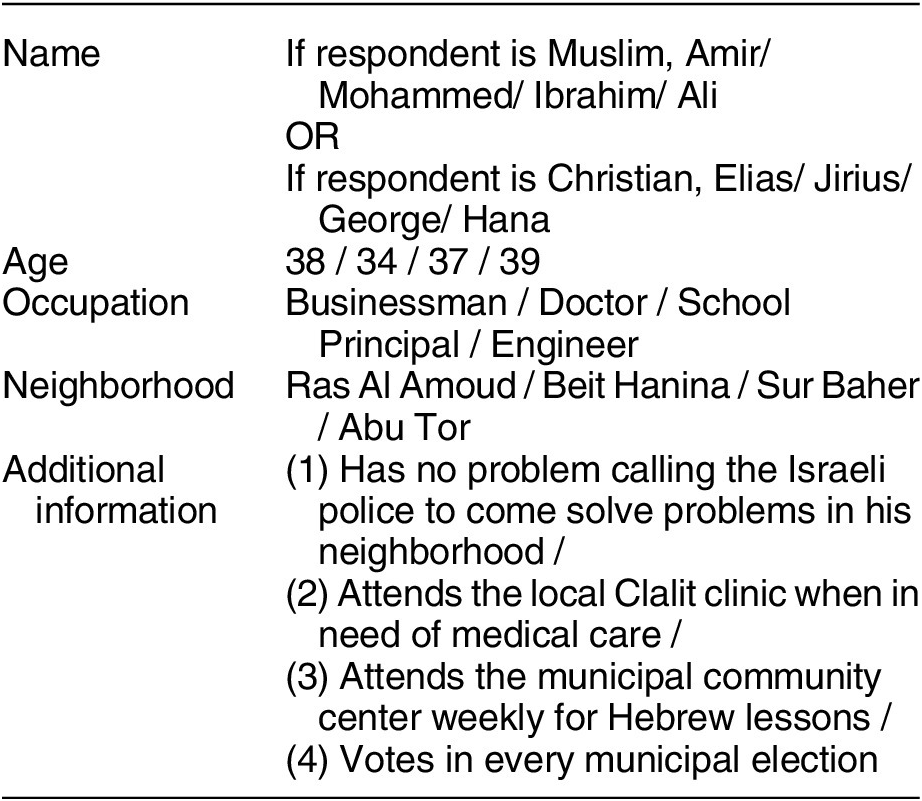

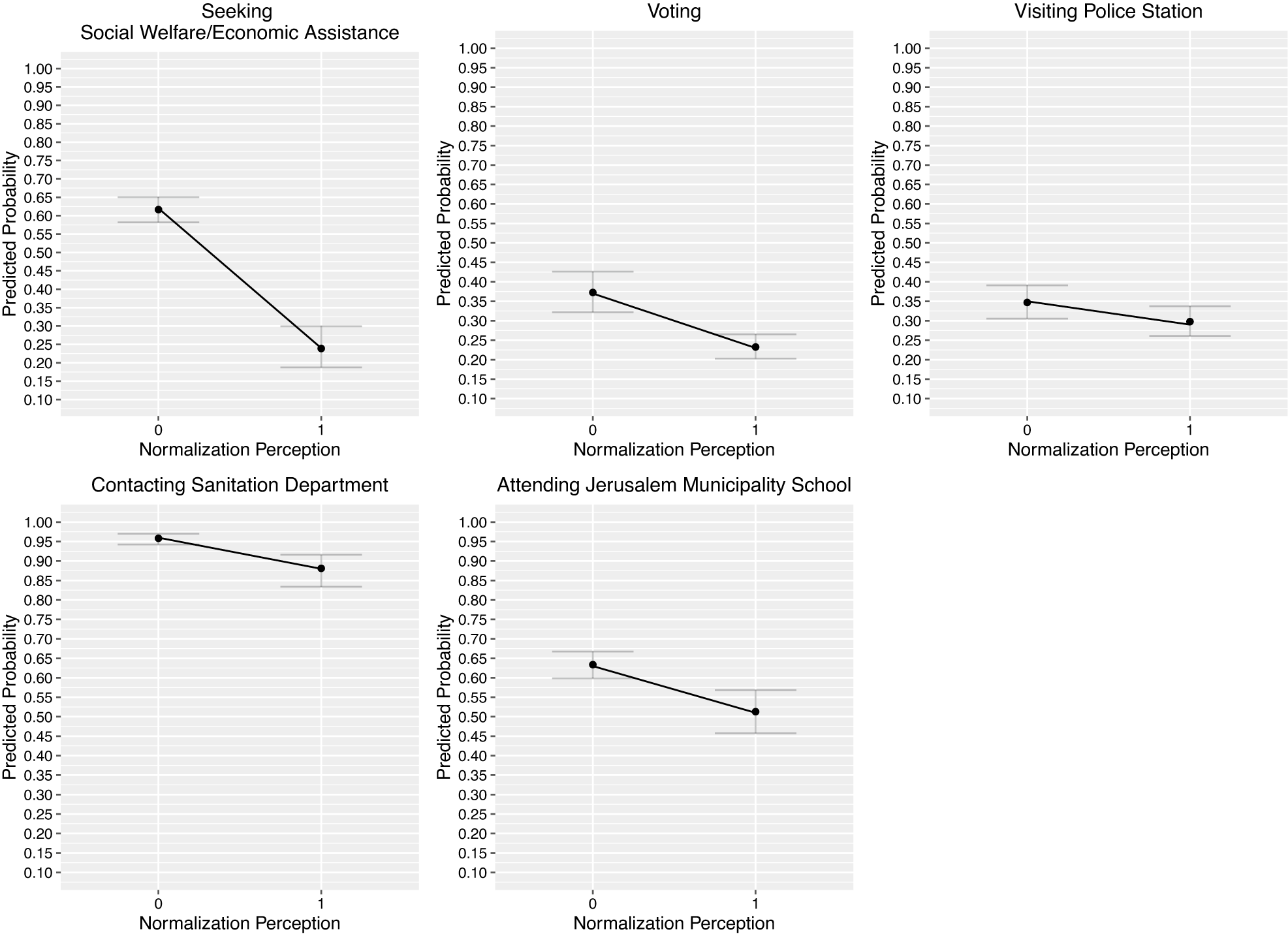

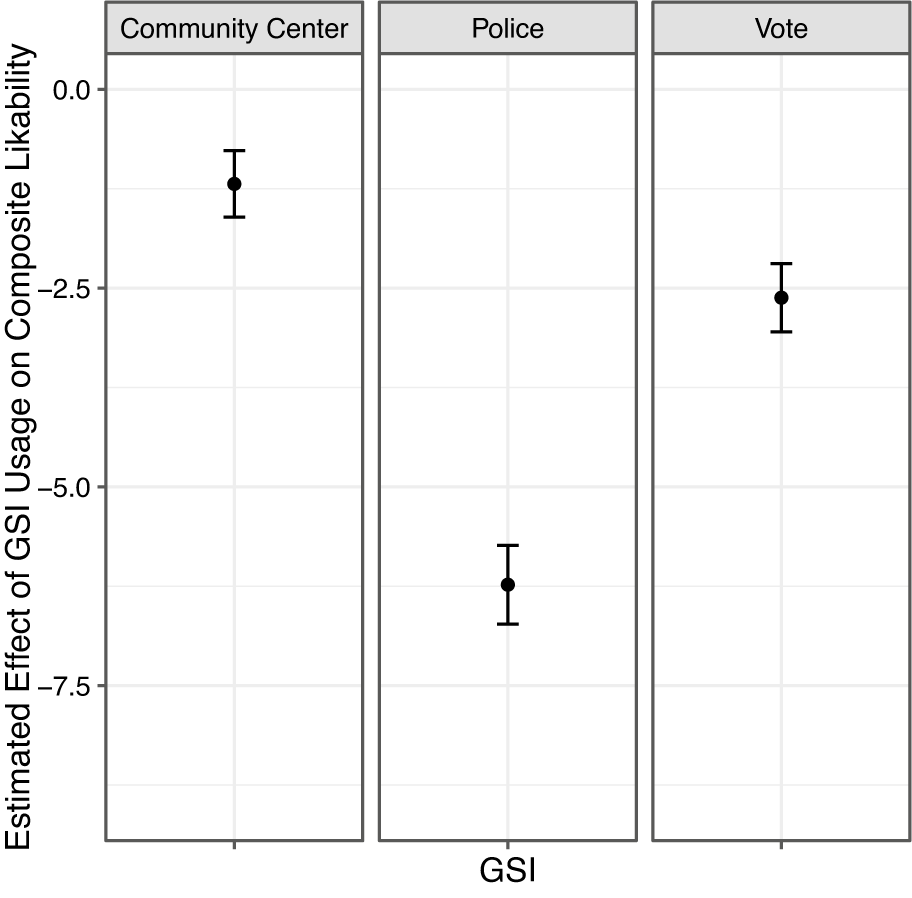

The final form of analysis is a vignette-style experiment embedded within the original survey which measures whether engaging with particular GSIs affects one’s assessment of the likeability and respectability of potential neighbors. The experimental design was chosen due its ability to isolate the influence of specific treatment conditions—in this case, specific forms of engagement—on the attitudes of Palestinian East Jerusalemites toward their peers. The experiment is modeled after an experimental design used by Anoll (Reference Anoll2018) and Gerber et al. (Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty and Dowling2014). Anoll (Reference Anoll2018) used the experiment to measure race-based social norms surrounding different forms of political participation in the US. Here the experiment is adapted to assess how East Jerusalemites evaluate their peers based upon their involvement with different Israeli GSIs, but is kept as similar as possible for the sake of comparison.

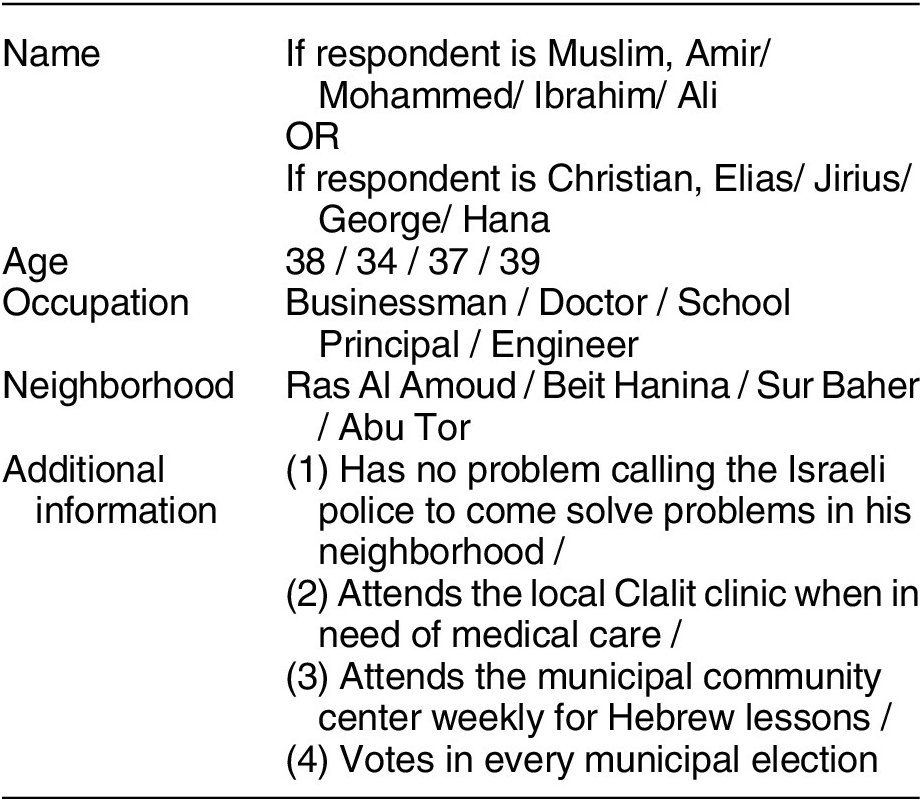

Each respondent was shown six randomly generated profiles or vignettes using combinations of five attributes (Name, Age, Occupation, Neighborhood, Additional Information), each containing four levels. Table 2 lists the question, attributes, and levels included in the experiment. The treatment and control conditions—forms of engagement with Israeli state GSIs—are included in the “additional information” attribute. In order to retain sufficient statistical power for analysis, the “additional information” attribute contains only four of the many forms of engagement with the Israeli state that the hypothetical person could take part in. The loss of breadth for statistical power is a trade-off of this experimental design. These four chosen forms of engagement include voting in municipal elections, contacting the police to help solve problems in the neighborhood, attending a municipal community center weekly for Hebrew lessons, and attending a local state-run health clinic for routine medical care. Three of the four “additional information” levels were designated as treatment (vote, police, community center) and the remaining as the baseline or control (health). Health was designated as the control because it is nearly ubiquitously engaged with (96.09% of respondents report accessing Israeli primary care clinics), and thus engagement is likely to be perceived as neutral. As such, the experiment compares perceptions of the likability of potential neighbors who engage with “political” GSIs (police, voting, community centers) to the likability of potential neighbors who engage with the prototypical “technical” GSI (health). Christian and Muslim respondents were shown classically Christian and Muslim names respectively, so as to ensure that religious identity was not a confounding factor. Because each respondent was shown six profiles, the sample size for the experiment was 7,530, and most if not all respondents were exposed to both treatment and control conditions.

Table 2. Question: Now We Are Going to Look at Descriptions of Six Made-Up People Who are Hypothetically Interested in Moving into Your Neighborhood

Note: After looking at each description, I will ask you how you feel about these people. On a scale of 1 to 10, rate your level of agreement with the following statements; (a) My overall impression of this person is positive (1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10), (b) I think this person is responsible (1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10), (c) I respect this person (1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10), (d) I would feel comfortable if this person moved in next door to me as my neighbor (1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10).

After viewing each profile, the respondent was asked a series of four questions assessing the likability, respectability, responsibility, and neighborliness of the person in the profile, which are listed beneath Table 2. Respondents ranked these measures (likeability, respectability, responsibility, neighborliness) on a scale of 1 to 10. The key dependent variable in this analysis is a composite likability score which sums the answers to all four questions. The “additional information” attribute contains the treatments, while the other four variables are included as controls.

FINDINGS

Variation in Patterns of Engagement across Sectors

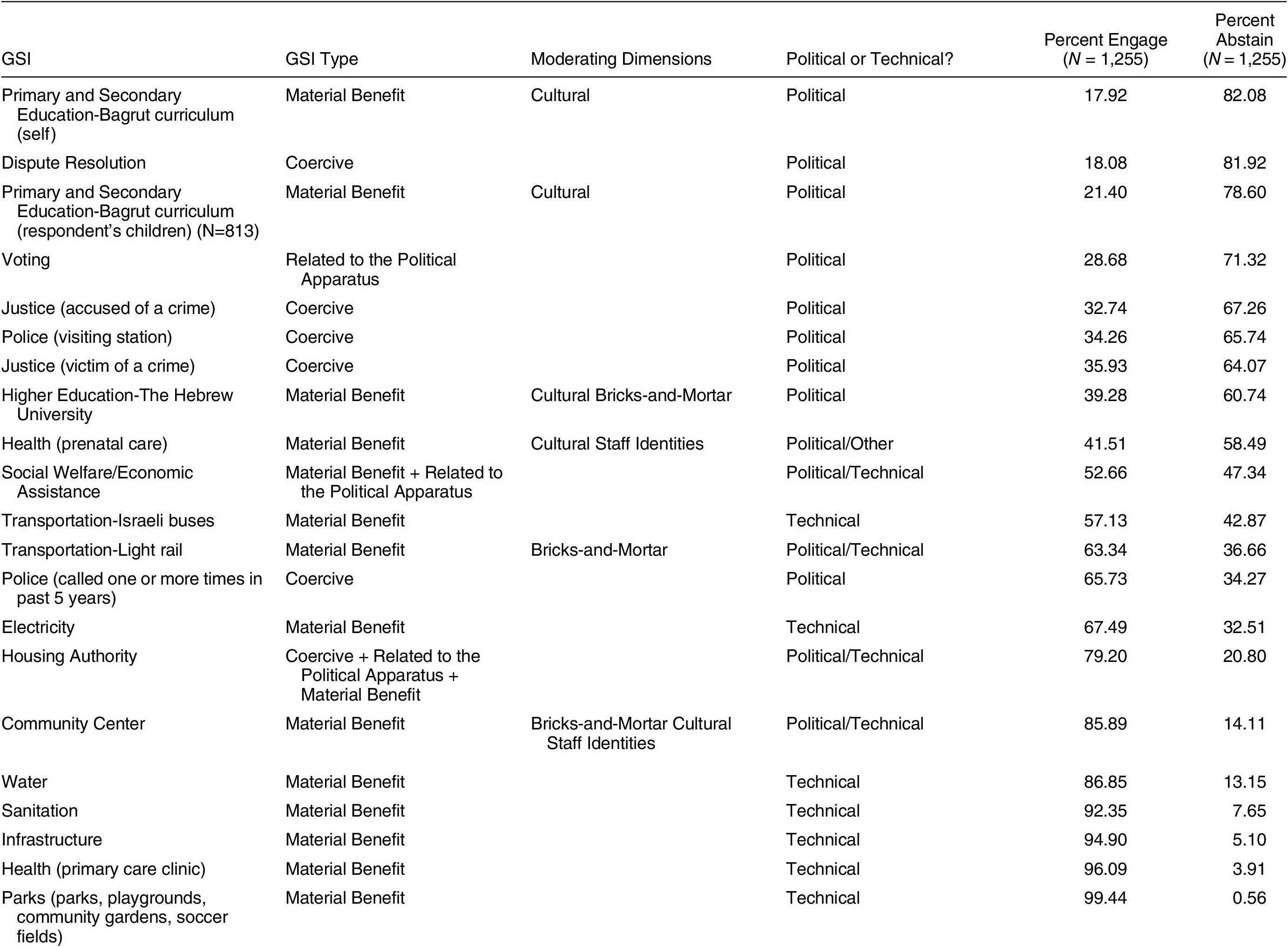

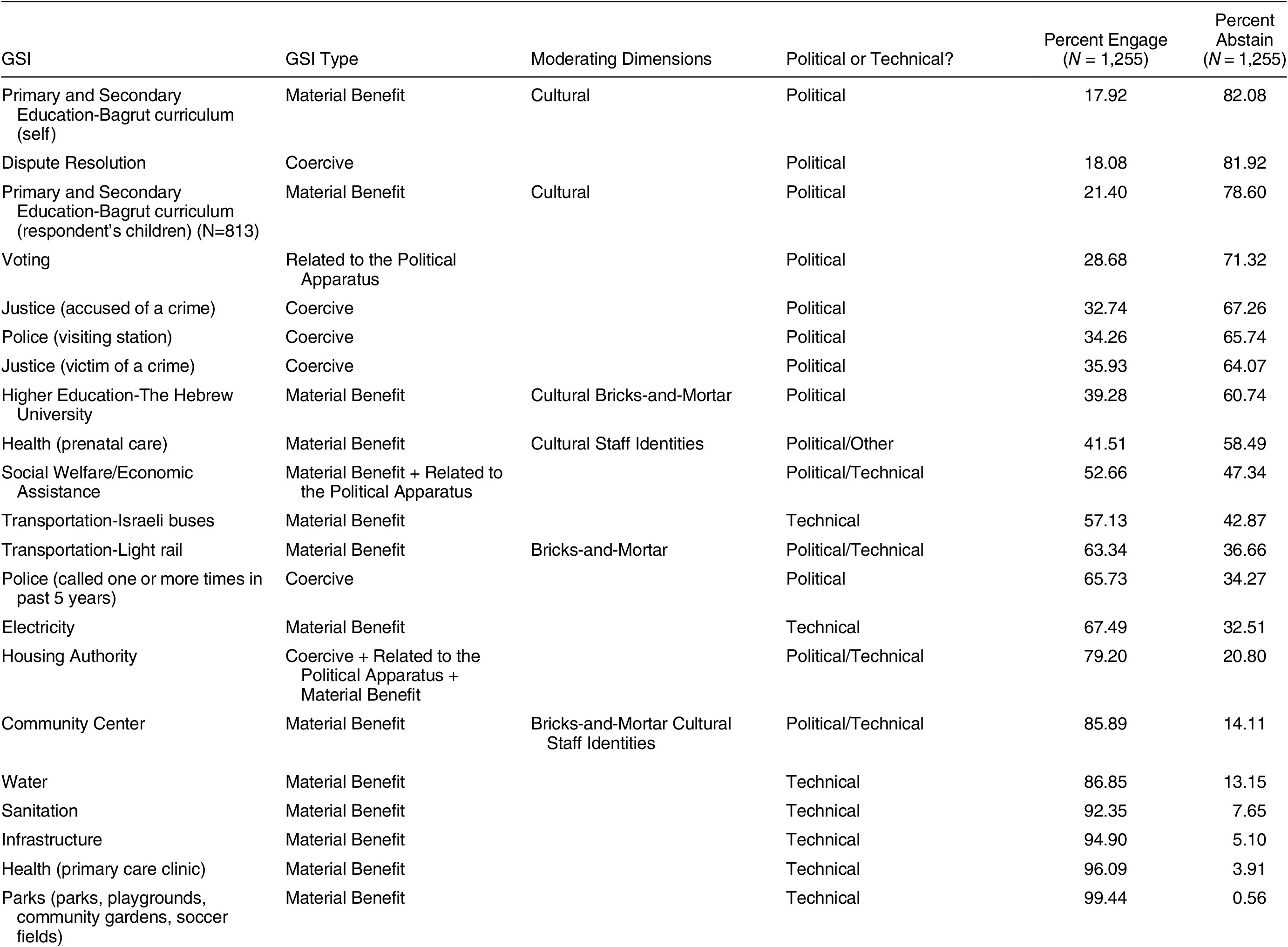

In order to arrive at a theory that explains divergent patterns of engagement across service sectors, it is first necessary to identify which sectors are commonly engaged with and which are most commonly abstained from. As one interviewee put it, services can be put into three categories; “those that people have and won’t take, those that people don’t have and want, and those that people have and want.”Footnote 15 Thus, for the purposes of this article the first task is to identify which services fall into categories 1 and 3. Table 3 lists proportions of individuals who reported engaging with, or being willing to engage with, the Israeli state when in need of help concerning a particular GSI, the GSI type and relevant moderating dimensions, and the political vs. technical designation for each GSI.

Table 3. Levels of Engagement with Each GSI

The purpose of the tallies reported in Table 3 is to capture broad patterns of engagement across sectors. Several features of the results are worth noting. First, several of the questions were aimed at capturing within-sector variance and multiple service types from the same sector were included if variation was indicated during interviews. For example, Palestinian East Jerusalemites may choose between a range of state and non-state options when seeking medical care.Footnote 16 While state-run primary care clinics are near-ubiquitously engaged with, interviewees suggested and the survey data later confirmed that many East Jerusalemite women prefer non-state Palestinian providers when seeking prenatal care and delivery options (i.e., invoking the staff identities moderating dimension). Interviewees expressed concerns over discrimination surrounding prenatal care and cited birth as a “social and religious” phenomenon with norms and rituals best observed within one’s own community.Footnote 17 It should be noted that the primary healthcare vs. prenatal care differential was the largest of all within-sector tests. Additionally, significantly more people have called the police to solve a problem (65%) than have visited a police station to solve a problem (34%). Percentages of respondents who participated in the Israeli Bagrut curriculum are similar to percentages of respondents who send their children to Bagrut curriculum schools. However, there is more comfortability enrolling in the Hebrew University (39%) than in primary and secondary schools (17%–21%). Slightly more people use the light rail than do buses, but negligibly so. And finally, percentages of those who would seek out Israeli authorities (police or courts) if the victim of a crime or if accused of a crime are within a few percentage points.

Second, the survey data indicate that in practice, East Jerusalemites call the police, contact the housing authority, and attend community centers more frequently than purported by interviewees. In total, roughly 65% of individuals have contacted the police at least once in the past five years to report an issue or solve a problem. Within that 65%, roughly 17% have contacted the police just once, 3% have contacted the police two or three times, and a sizable 46% of the sample have contacted the police four or more times. However, only roughly 34% have visited a police station to report and issue or solve a problem. The difference in willingness to call the police vs. visit a police station could indicate underlying concerns regarding monitoring and social sanctioning should one be seen engaging with the state. Namely, an East Jerusalem resident can call the police from inside their home without others noticing, but if they are to arrive at a police station and proceed to report an issue, it is more likely to be observed by others in the community. Thus, the discrepancies between the survey and interview data surrounding police contacting could indicate that East Jerusalemites may seek out services that affirm the state’s claim to sovereignty if they can also avoid being seen by their peers.

Designations of the GSI Type and Moderating Dimensions are a summation of factors cited by interviewees for designating a particular GSI as political or technical and were derived inductively by the author. During the semi-structured in-depth interviews I kept a list of GSIs and asked respondents to describe whether engaging with each discrete GSI constitutes an act of normalization. The political/technical distinctions were then designated inductively based upon the consensus that emerged from this line of questioning. Several interviewees explicitly described discrete GSIs as political or technical elsewhere in the interview and these designations also contributed to the final designations listed in Table 3. Column four of Table 3 lists several GSIs as both political and technical (community centers, the housing authority, welfare/economic assistance, and the light rail). These designations were given when interviewees repeatedly discussed ambiguities in the acceptability of usage of particular “grey area” GSIs.Footnote 18 Because the housing authority and municipal community centersFootnote 19 are two key municipal institutions interfacing with the Palestinian public to handle necessary matters such as the issuance of housing permits, the payment of parking fines, and the allocation of certain social service benefits, most individuals have dealt with these institutions out of necessity. However, interviewees noted that an individual’s reason for visiting or contacting these institutions can be relevant, whether the visit is out of necessity or whether the service sought is related to sensitive issues such as culture or education.Footnote 20 Likewise, several interviewees described seeking welfare/economic assistance as having a political valence due to the complicity of the Welfare Department in home demolitions and surveillance and, by extension, in the political agenda of the state.Footnote 21 However, it is also the case that welfare/economic assistance is sought out of necessity and thus the state holds a limited degree of legitimacy in its role as the purveyor of such benefits. In a similar vein, though more than half of respondents report using the light rail, the light rail has historically been a locus of controversy because it connects Jewish Israeli settlement communities in East Jerusalem to West Jerusalem, and in doing so entrenches the state’s claims to sovereignty over East Jerusalem via the erection of infrastructure (Barghouti Reference Barghouti2009).Footnote 22 However, it has become more accepted over time as a material benefit provided by the state that is particularly useful for residents of the neighborhoods of Musrara, Shiekh Jarrah, Shu’afat, and Beit Hanina.Footnote 23 With these patterns in mind, we can now ask, why are certain sectors nearly ubiquitously engaged with, while others are only engaged with by some fraction of the population? What drives this variation across sectors?

Observational Findings

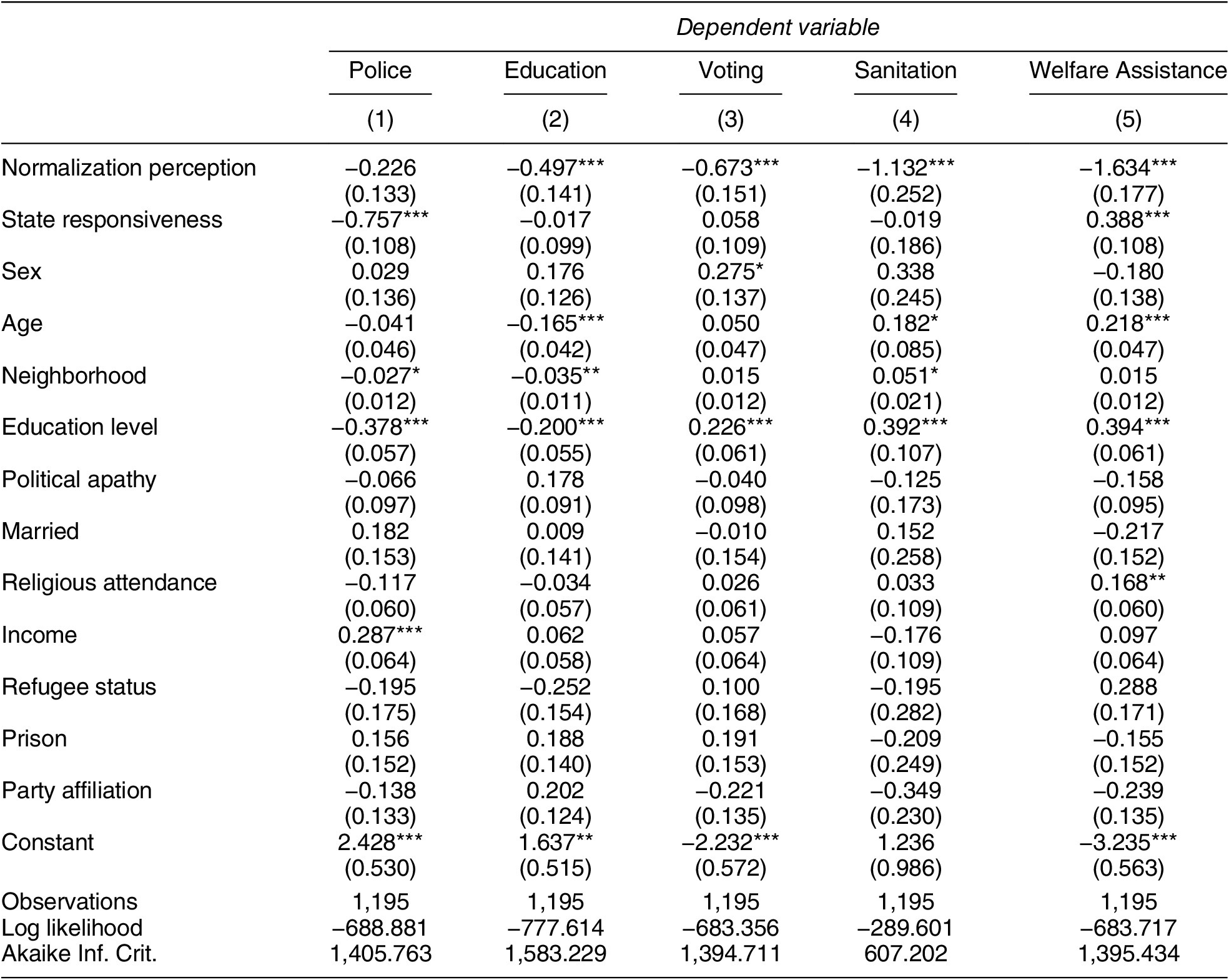

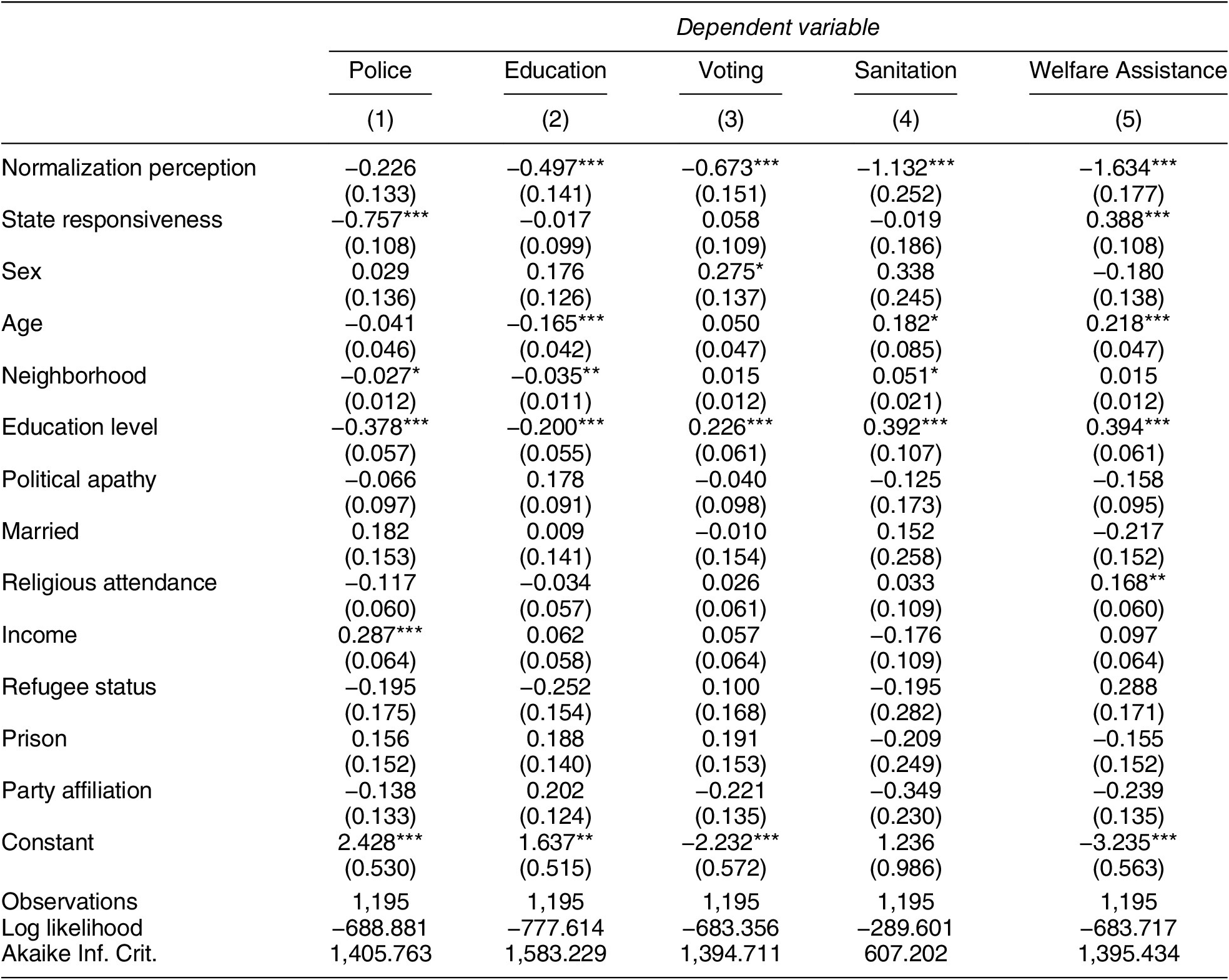

Having established that there is variation to be explained, Tables 4 and 5 provide the results of Logit regressions which are used to test the effect of perceiving engagement with a GSI to be an act of normalization on individual engagement with that GSI. As such, the models presented in Tables 4 and 5 are tests of Hypotheses 1, 1a, and 1b. As noted in the Research Design section, the primary independent variable is a binary “yes/no” record of whether an individual perceives engagement with a particular GSI to be an act of normalization. The dependent variable in all of the models is the individual’s answer to the corresponding question from the services census which records their engagement/non-engagement with that GSI.

Table 4. Effect of Normalization Perception on GSI Engagement, Logit (M1–M5)

Note: *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

; **

$ p<0.05 $

; **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

; ***

$ p<0.01 $

; ***

![]() $ p<0.001 $

$ p<0.001 $

Table 5. Effect of Normalization Perception on GSI Engagement, Logit (M6–M10)

Note: *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

; **

$ p<0.05 $

; **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

; ***

$ p<0.01 $

; ***

![]() $ p<0.001 $

$ p<0.001 $

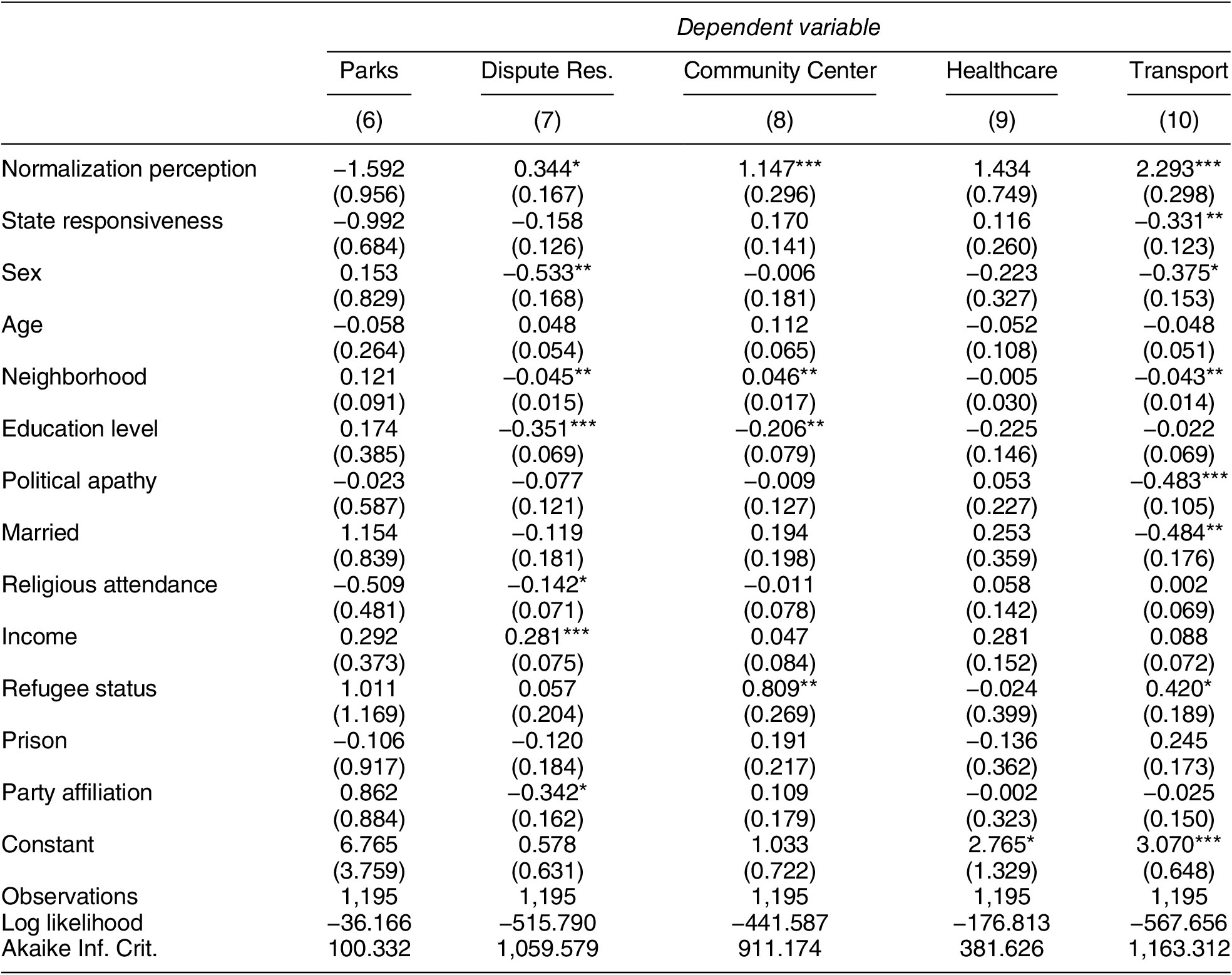

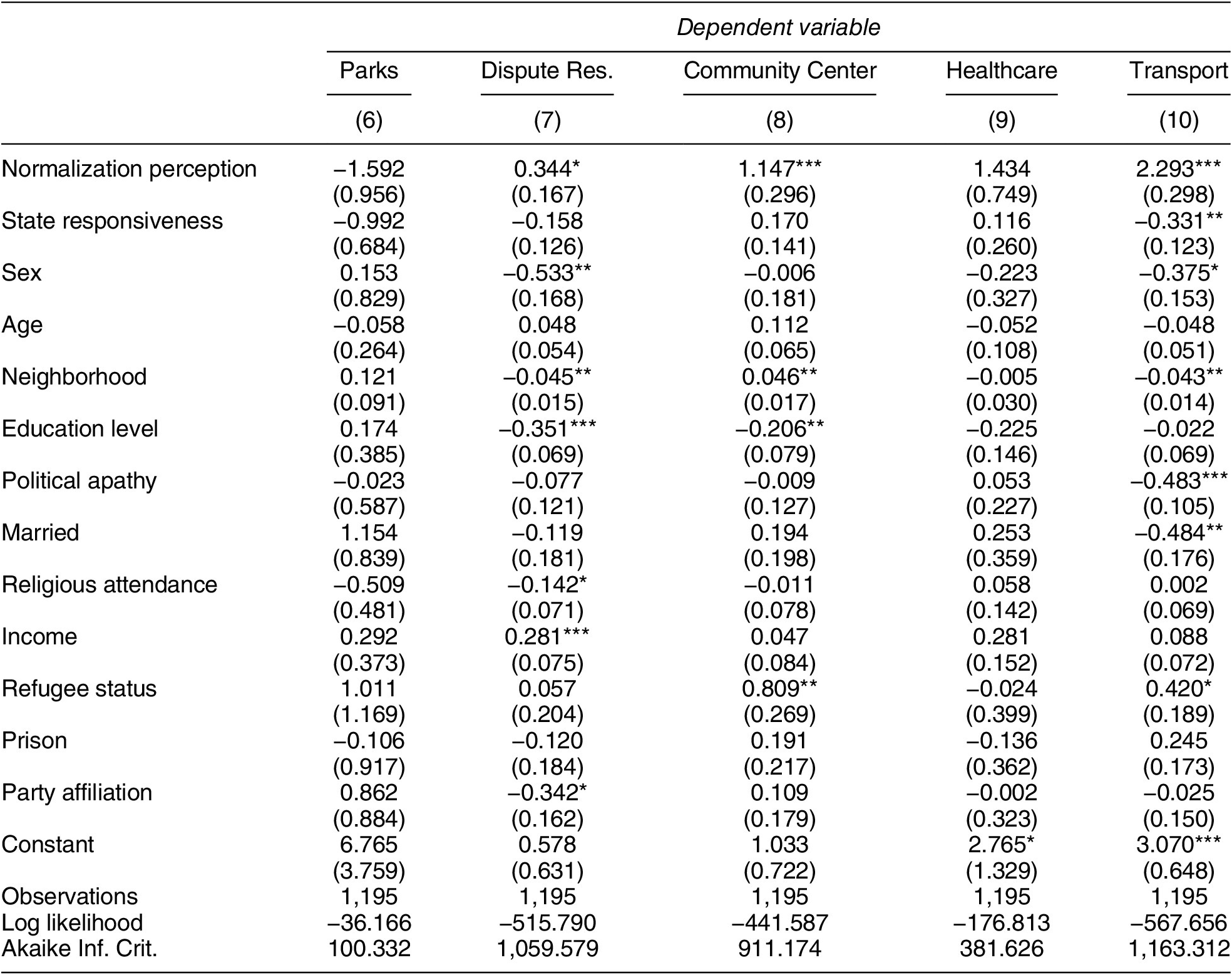

Table 4 displays the results of the Logit regression for 5 of 10 services under consideration, four of which are significant at the 0.001 level and one (Policing) at the 0.1 level.Footnote 24 These results indicate that a one-unit change in normalization perception (corresponding with a change from 0 to 1, or “no” to “yes”—engaging with the GSI in question is an act of normalization) leads to a statistically significant decrease in likelihood that a respondent will engage with the state in that sector (also on a 0 to 1 scale). These results hold for policing (−0.226), education (−0.497), voting (−0.673), sanitation (−1.132), and welfare/economic assistance (−1.634). The associated predicted probabilities of engagement with respect to normalization perception are included in Figure 3. These predicted probabilities should be interpreted as percentage likelihoods that an individual would engage with the GSI in question, given their perception of whether engaging with that GSI is an act of normalization. For example, someone who perceives voting to be an act of normalization has a 23% probability of voting, while someone who does not perceive voting to be an act of normalization has a 37% probability of voting.

Figure 3. Predicted Probabilities of Engaging with GSI Given Normalization Perceptions

Because the scales of the Y axes are the same across plots, Figure 3 provides a visual comparison of the likelihood that individuals will engage with each discrete sector. For example, East Jerusalemites are more likely to contact the sanitation services department than vote, seek welfare/economic assistance, attend a Jerusalem Municipality school, or visit a police station. These results broadly affirm Hypothesis 1a and 1b, which state that individuals are more likely to engage with services considered technical or political/technical (sanitation services, welfare assistance), than those considered incontrovertibly political (voting, visiting a police station, attending a Jerusalem Municipality school).

Several qualifications should be made regarding the results presented in Figure 3. Notably, the ranges in predicted probability scores vary in size from relatively small (a 6% decrease in probability of visiting a police station and a 8% decrease in contacting the sanitation department) to quite large (a 38% decrease in probability of seeking social welfare/economic assistance and a 14% decrease in probability of voting). Interestingly, there does not seem to be a consistent pattern linking the magnitude of predicted probability ranges to either political or technical GSIs. While these results do not explicitly contradict any of the listed hypotheses, a uniform association between high magnitude ranges and political GSIs and low magnitude ranges and technical GSIs would be the strongest form of evidence for the theory that individuals will be most likely to avoid political sectors in which the state lacks legitimacy. The results instead show some surprising variation in the deterrent effects of anti-normalization commitments in sectors commonly deemed technical and political/technical.

Variation in predicted probability ranges across political and technical GSIs should be interpreted in conjunction with the puzzling finding that the coefficients for sanitation and welfare assistance reported in Table 4 are larger than the coefficients associated with the three overtly political GSIs of policing, education, and voting. It is possible that the larger coefficients associated with sanitation and welfare/economic assistance are a function of the fact that the samples of those who abstain from technical and political/technical GSIs are smaller than the samples of those who abstain from the three incontrovertibly political GSIs. Recalling Table 3, only 7.65% of individuals reported abstaining from contacting the sanitation department and 47.34% of individuals reported abstaining from contacting the state in pursuit of welfare/economic assistance as compared to 82.08% for education, 71.32% for voting, 65.74% for visiting a police station. As a result, the proportion of those who abstain while also holding anti-normalization stances may be higher in the case of sanitation and welfare/economic assistance as compared to education, voting, and policing, resulting in stronger correlations and larger coefficients in the former. Thus, the need to make comparisons between coefficients generated from non-uniform distributions of those who engage vs. abstain in each sector is a limitation of the study design, but a necessary factor to contend with when comparing across sectors where variation in engagement percentages is to be expected.

Alternatively, it is possible that the material benefits of sanitation and welfare/economic assistance are perceived as “political” sectors by a sufficiently substantial subset of the population due to these GSIs’ relation to the political agenda(s) of the state. Some interviewees noted that East Jerusalemites hold suspicions that those who receive benefits from the Welfare Department are more likely to be surveilled by the state and face consequences such as residency revocation, home demolition, or family separation for information gleaned as a result of that surveillance.Footnote 25 Another interviewee recounted East Jerusalemites’ explicit rejection of Welfare Department benefits on the grounds that the department forwards the political agenda of the state through complicity in the practice of home demolitions,

When a home is demolished, the city offers the family 3 months of rent and 500 NIS a household member for food. This is provided by the Welfare Department through a social worker. This is often rejected. People don’t want to accept a handout from the city when they just demolished the house. (Interview 13. 2022. City Councilperson. Interviewed by Author, West Jerusalem)

While interviewees did not explicitly describe sanitation as possessing a political valence, several described poor sanitation conditions as a major problem for East Jerusalemites.Footnote 26 Indeed, poor sanitation provision in East Jerusalem has been cited as evidence of the city’s attempt to expel Palestinians by making the conditions in East Jerusalem neighborhoods unlivable, thereby implicating the sanitation department in the political agendas of the state (Baumann and Massalha Reference Baumann and Massalha2022; Stamatopoulou-Robbins Reference Stamatopoulou-Robbins2020). If it is the case that these GSIs are in fact commonly perceived as “political,” then the associated large negative coefficients would be consistent with the theory that East Jerusalemites are most likely to avoid political sectors in which the state lacks legitimacy, or the right to rule, as conferred by civilians.